Abstract

Background

Hydrodynamic tail vein injection (HTVI) of transposon-based integration vectors is an established system for stably transfecting mouse hepatocytes in vivo that has been successfully employed to study key questions in liver biology and cancer. Refining the vectors for transposon-mediated hepatocyte transfection will further expand the range of applications of this technique in liver research. In the present study, we report an advanced transposon-based system for manipulating gene expression in hepatocytes in vivo.

Methods

Transposon-based vector constructs were generated to enable the constitutive expression of inducible Cre recombinase (CreER) together with tetracycline-inducible transgene or miR-small hairpin RNA (shRNA) expression (Tet-ON system). Transposon and transposase expression vectors were co-injected into R26R-mTmG reporter mice by HTVI. Cre-mediated gene recombination was induced by tamoxifen, followed by the administration of doxycycline to drive tetracycline-inducible gene or shRNA expression. Expression was visualized by immunofluorescence staining in livers of injected mice.

Results

After HTVI, Cre recombination by tamoxifen led to the expression of membrane-bound green fluorescent protein in transfected hepatocytes. Activation of inducible gene or shRNA expression was detected by immunostaining in up to one-third of transfected hepatocytes, with an efficiency dependent on the promoter driving the Tet-ON system.

Conclusions

Our vector system combines Cre-lox mediated gene mutation with inducible gene expression or gene knockdown, respectively. It provides the opportunity for rapid and specific modification of hepatocyte gene expression and can be a useful tool for genetic screening approaches and analysis of target genes specifically in genetically engineered mouse models.

Keywords: HTVI, hydrodynamic tail vein injection, inducible gene expression, sleeping beauty transposon, Tet-ON system

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Chronic liver disease presents a major health burden in Europe and worldwide,1 calling for scientific efforts to better understand the pathogenesis of liver disease and to find new strategies for treatment. To gain insight into the molecular mechanisms driving liver disease, animal models provide powerful investigational tools of a wide range of different liver pathologies.2 Genetic modification of hepatocytes in vivo has led to major advances in our understanding of different kinds of liver disease, including primary liver cancer.3 However, the generation of genetically engineered mouse models is both time and labor consuming. Therefore, the development of alternative tools to target gene expression in the liver, such as gene delivery by adeno-associated viruses (AAV) or hydrodynamic tail vein injection (HTVI), has gained momentum over recent years.4–8 In combination with transposase-mediated chromosomal integration, gene delivery to hepatocytes by HTVI provides an advantage over commonly used viral vectors such as adenovirus or AAV in that long-term gene expression can be achieved in targeted liver cells even after multiple cell divisions.5,8 Although AAV vectors target hepatocytes with high efficiency, integration into the hepatocyte genome is considered to be a rare event9 and AAV-mediated gene expression is usually rapidly lost in dividing hepatocytes. Additionally, the limited capacity and complex manufacturing process present further obstacles to their application.10 Similar limitations apply for the infection of hepatocytes with adenoviral vectors: gene delivery is only transient and their in vivo application induces a profound immune response in the liver.11 However, even with transient expression, these vectors can be successfully employed to genetically alter hepatocytes in vivo either by the use of recombinases such as Cre or Flp in genetically engineered mice or by the adaptation of novel genetic tools such as CRISPR/Cas9 systems to induce stable mutations.12 Nevertheless, certain applications such as stable transgene expression in tumor models or reversible inducible models require stable chromosomal integration. Although lentiviral vectors can achieve stable genomic integration in several in vitro and in vivo models, hepatic targeting is mostly inefficient in quiescent hepatocytes and therefore of limited use in adult mice.13 Therefore, HTVI remains the method of choice to achieve genomic integration and induce stable gene expression from hepatocytes.

Hydrodynamic tail vein injection has been successfully employed in preclinical models of genetic diseases to investigate experimental approaches for gene therapy5 and has also been used in cancer research to identify the relevance of several oncogenes in hepatic carcinogenesis.8 More recently, combination with small hairpin RNA (shRNA)-mediated gene knockdown and CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene mutation enabled the identification and alteration of relevant molecular pathways in liver biology and cancer.14–17 Using HTVI, the targeting of multiple genes can be achieved by simultaneous injection of different transposon-vectors. However, with an increase in the number of vectors injected, the percentage of hepatocytes targeted by all vectors simultaneously is likely to decrease. As an alternative, vectors expressing multiple genes from one single vector can be used. However, an increase in size of the gene fragments that are delivered by HTVI goes in line with a decrease in transfection efficiency.18 Yet the size limit of HTVI-delivered transposon vectors remains far larger than that of other commonly used vector systems such as AAV.8 Therefore, the simultaneous targeting of different genes within the same vector is not only achievable for a combination of a transgene with smaller shRNA constructs,15 but also can be used for the simultaneous expression of two or more different transgenes within the same cell. Additionally, transposon-mediated cell transfection can also be employed to deliver systems for inducible gene expression and gene knockdown, as used in in vitro lentiviral systems19 or more elaborate mouse models.20 However, no such system exists to date for transposon-mediated gene delivery to hepatocytes in vivo.

In the present study, we report a novel system combining constitutive transgene expression together with tetracycline-inducible gene expression or gene knockdown in a single vector that is designed for stable transfection of mouse hepatocytes by HTVI. The combination with a gateway cloning system enables the fast and efficient cloning of transgenes or shRNAs and facilitates the use of the system in large scale applications such as in vivo screening approaches.15,17,19 With CreERT2 as a constitutive expression cassette, this system can be used in conditional mouse models to control liver-specific mutation of floxed target genes and to simultaneously evaluate the relevance of related genes of interest in the same model.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Cloning of transposon vectors

Transposon constructs are based on the sleeping beauty transposon system described previously.5,21 In brief, a multiple cloning site with appropriate restriction sites was synthesized and cloned between sleeping beauty recognition sites. All elements were subsequently cloned between restriction sites using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification by sequence specific oligonucleotides (see Supporting information, Table S1). The ApoE.HCR.hAAT-promoter and the CreERT2 expression construct were amplified from a CreERT2 transposon construct as described previously.21 The mCherry expression construct was subcloned after a 2A peptide within the multiple cloning site, allowing for simultaneous expression of CreERT2 and mCherry. The empty Tet cassette for inducible gene expression or gene knockdown was amplified from pSLIK-Hygro (Addgene #25737; Addgene, Cambridge, MA, USA).19 For replacement of the ubiquitin-C promoter driving rtTA3 expression, CMV- and ApoE.HCR.hAAT-promoters were cloned between PacI and AscI restriction sites of the original pSLIK-Hygro vector. The whole Tet cassette was then PCR-amplified and cloned into the transposon vector as described above.

The entry vector for inducible gene expression of YAP-Flag was generated by amplification from p2xFlag CMV2-YAP2 (Addgene #19045) using touchdown PCR followed by subcloning into pEN_TTmcs (Addgene #25755). The entry vector for inducible shRNA expression was generated using a validated shRNA sequence against mouse Hnf4α22 that was modified in accordance with the pSLIK cloning protocol19 followed by subcloning into pEN_TTGmiRc2 (Addgene #25753).

Ready-for-injection transposon vectors were made by Gateway recombination of entry vectors (pEN_TTmcs or pEN_TTGmiRc2, respectively) and appropriate destination vectors (empty pTC-Tet vectors with different rtTA3 promoters) using the Gateway LR Clonase II Enzyme mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA)23 in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The identity of all constructs was confirmed by automated sequencing.

2.2 |. Hydrodynamic tail vein injection and animal experiments

For HTVI, 150 μg of the sleeping beauty transposon construct and 10 μg of a transposase expression vector (pc-HSB5)5 were dissolved in 10 ml of saline. A volume of 1 ml per 10-g bodyweight was injected by HTVI into 8–10-week-old R26R-mTmG (Rosa26mTmG) mice that express membrane-bound green fluorescent protein (GFP) after Cre activation or into R26R-Tom mice harboring a Cre-activated tdTomato reporter (Rosa26LSL-tdTomato) that is expressed in the cytoplasm after Cre activation.24 Ten days after HTVI, 1 mg of tamoxifen was injected intraperitoneally on three consecutive days to activate the Cre recombinase (CreER) in transfected hepatocytes. To induce transgene or shRNA expression, respectively, drinking water was supplemented with doxycycline at a concentration of 1 mg/ml. Control animals were left on normal drinking water. After 5 days of doxycycline treatment, animals were sacrificed for analysis. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and were approved by responsible authorities (Stanford Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Stanford, CA, USA; Regierung von Oberbayern, Munich, Germany).

2.3 |. Histology and immunostaining

In R26R-mTmG mice, immunofluorescent staining was performed on paraffin-embedded liver sections of injected animals using primary antibodies against FLAG (mouse anti-FLAG M2, #F1804, dilution 1:50; Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), GFP (GFP chicken IgY antibody, #A10262, dilution 1:100; GFP rabbit IgG polyclonal antibody, #A-11122, dilution 1:100–1:300; both Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), YAP (#4912, dilution 1:50; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA) and HNF4α (#sc-8987, dilution 1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and appropriate secondary antibodies. Livers from R26R-Tom mice were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h followed by cryoprotection with increasing concentrations of 10%, 20% and 30% sucrose solution and embedding in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. Compound (Sakura Finetek Germany GmbH, Staufen, Germany). Cryosections were stained with GFP primary antibody (GFP rabbit IgG polyclonal antibody, #A-11122, dilution 1:250 Invitrogen) and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy.

2.4 |. Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was assayed by a two-tailed Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.005). Graphs represent average of at least three mice analyzed per group. Error bars represent the SD.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Variable expression after transgene delivery by HTVI with separate transposon vectors

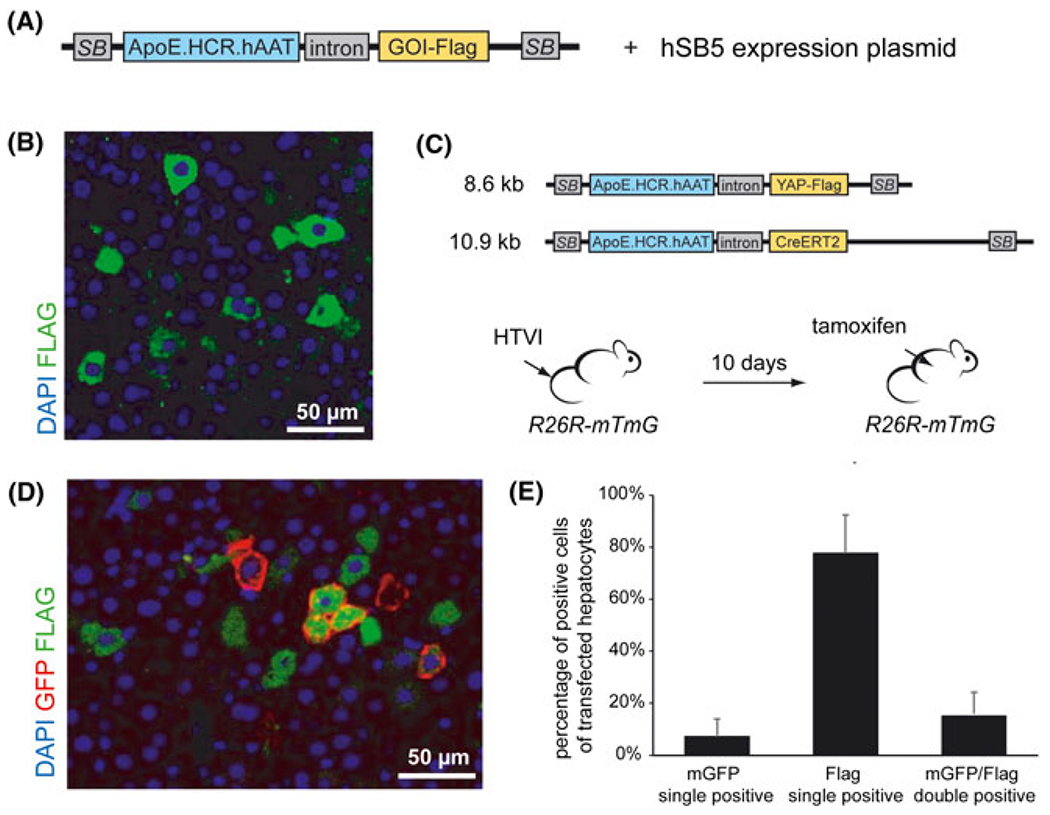

Expression of a transfected gene of interest in hepatocytes can be successfully visualized when vector delivery by HTVI is combined with a FLAG-tagged gene expression construct that is flanked by recognition sites for sleeping beauty transposase (Figure 1A and 1B).21 To achieve stable expression of two transgenes within the same hepatocyte, a mixture of two or more transposon constructs can be injected. Such a system has been successfully employed to dissect the role of interacting tumor suppressor and oncogenes in liver cancer.25–27 To test whether the combined expression of two transgenes can be achieved in the majority of transfected hepatocytes, we injected two different transposon constructs at equal concentrations into mice that harbor an mTmG reporter cassette under the control of the Rosa26 gene locus (R26R-mTmG).28 One construct mediates the expression of Flag-tagged human YAP that can be detected by immunostaining for FLAG peptide (Figure 1B) and the second construct harbors an inducible CreERT2 recombinase.21 After Cre activation by injection of tamoxifen, transfected cells can be visualized by immunostaining for membrane-bound GFP (mGFP) (Figure 1C and 1D). Double-staining for FLAG and mGFP showed that less than one-quarter of all transfected hepatocytes expressed both YAP-Flag and CreERT2 (Figure 1E). Remarkably, there was a considerable variability in the percentage of transfected cells depending on the construct, ranging from 61% to 87% for YAP-Flag and from 3% to 15% for CreERT2 in single transfected cells (Figure 1C and 1E). At least in part, the observed differences might be a result of vector size leading to decreased transfection efficiency in the larger CreERT2 construct (Figure 1C and 1E).18 However, other size independent factors might also play a role. Although the approach to target different genes by injection of individual expression vectors is useful for some applications, robust combined expression within the same cell will be more reliable for studying interactions between genes and for interrogating the relevance of specific genes of interest in Cre-driven genetic models.

FIGURE 1.

Transgene expression after delivery of separate transposon vectors by HTVI. A, Schematic representation of the Sleeping Beauty (SB) transposon system for expression of a Flag-tagged transgene (GOI, gene of interest) under the control of a hepatocyte specific promoter (ApoE.HCR.hAAT). Co-injection of an expression plasmid for hyperactive Sleeping Beauty transposase (hSB5) drives chromosomic integration of injected transposon vectors. Not drawn to scale. B, Immunostaining for YAP-Flag (green) in the liver of mice injected with a YAP-Flag-transposon construct. C, Schematic representation of two transposon constructs (CreERT2-transposon, YAP-Flag-transposon) that were co-injected into R26R-mTmG mice; not drawn to scale. Expression of mGFP in hepatocytes transfected with the CreERT2-transposon construct was induced by tamoxifen 10 days after HTVI. D, Representative immunostaining of liver sections for mGFP (red) and FLAG (green) after HTVI of a CreERT2-transposon and a YAP-Flag-transposon in R26R-mTmG mice followed by tamoxifen treatment 10 days after HTVI. E, Quantification of immunostaining for GFP positive, YAP-Flag positive and YAP-Flag/GFP double-positive cells in R26R-mTmG mice injected with the CreERT2 and YAP-Flag transposon constructs depicted in (C) (n = 3)

3.2 |. Generation of a single vector for constitutive and inducible gene expression or gene knockdown in vivo

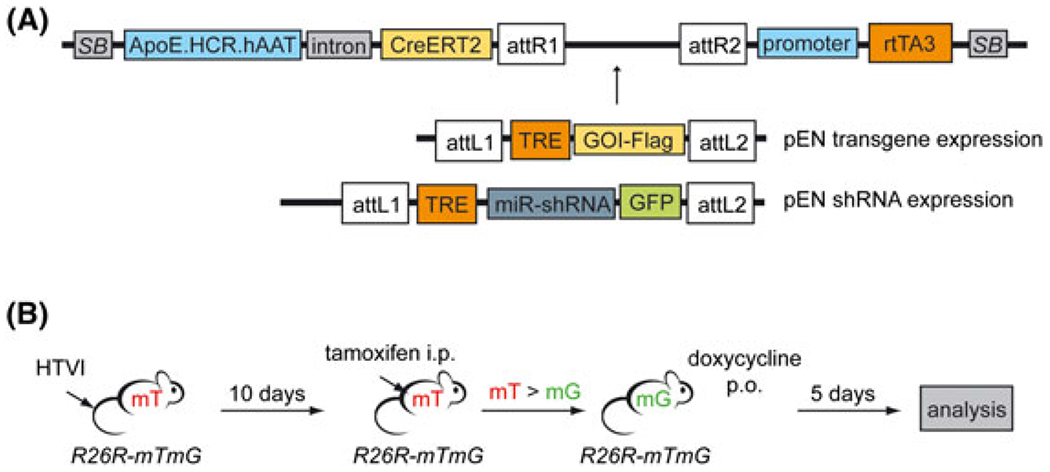

To develop a transposon system that combines constitutive expression of a tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase (CreERT2) with inducible gene expression or gene knockdown, respectively, we took advantage of two previously designed and validated vectors. The transposon-CreERT2 vector (pTC) expresses a CreERT2 under the control of a liver specific promoter (Figure 1C) and has been successfully used to induce mutation of floxed target genes in genetically engineered mouse models.21 The pSLIK construct is a lentiviral vector system for tetracycline-regulated gene expression or gene knockdown,19 consisting of an rtTA3 driven by a ubiquitin-C promoter and a recombination cassette for integration of the desired transgene or shRNA under the control of a tetracycline-responsible element (TRE). In this system, variable TRE-dependent constructs can be integrated from small entry vectors (pEN), allowing for rapid and efficient cloning even in large lentiviral vectors or transposon constructs designed for HTVI (Figure 2A). The use of FLAG-tagged transgenes allows for visualization of tetracycline-regulated gene expression by immunostaining, whereas entry vectors for the expression of miR-shRNA constructs were designed to co-express GFP (Figure 2A). Constitutive CreERT2 and tetracycline-regulated gene expression systems were combined in the pTC Tet vector for gene delivery by HTVI and genomic integration into hepatocytes in vivo. After HTVI of the pTC Tet vector into R26R-mTmG mice, the animals were injected intraperitoneally with tamoxifen for 3 consecutive days to activate CreERT2, resulting in a switch of expression from membrane-bound tdTomato (mT) to membrane-bound GFP (mG, mGFP) (Figure 2B). At least 10 days were left between HTVI and tamoxifen treatment to allow for integration of the transposon construct and loss of gene expression from non-integrated vector fragments.29 Following tamoxifen injection, mice were put on doxycycline-supplemented drinking water for 5 days to induced gene expression from the pSLIK-derived vector cassette before liver tissue was collected for analysis (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2.

A single vector for constitutive and inducible gene expression or gene knockdown in vivo. A, Schematic representation of the transposon system (pTC Tet) for constitutive CreERT2 expression (pTC) in combination with inducible gene expression or inducible gene knockdown (Tet), respectively. pEN entry vectors are used for gateway cloning of an inducible transgene (pEN transgene expression) or an inducible GFP-coupled miR-shRNA cassette (pEN shRNA expression) between the attR sites of the destination vector (top). attR, recombination sites destination vector; attL, recombination sites entry vector (pEN); TRE, tetracycline-responsive element; rtTA3, reverse tetracycline-controlled transactivator 3. Not drawn to scale. B, Work flow for transposon construct validation: HTVI of the transposon construct and the SB-transposase expression vector into R26R-mTmG mice; activation of CreERT2 by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of tamoxifen 10 days after HTVI; Tet-ON activation by continuous oral administration (p.o.) of doxycycline; analysis of liver tissue after 5 days of doxycycline treatment. mT, membrane-bound tdTomato; mG, membrane-bound GFP

3.3 |. Promoter-dependent expression of tetracycline-inducible transgenes in hepatocytes

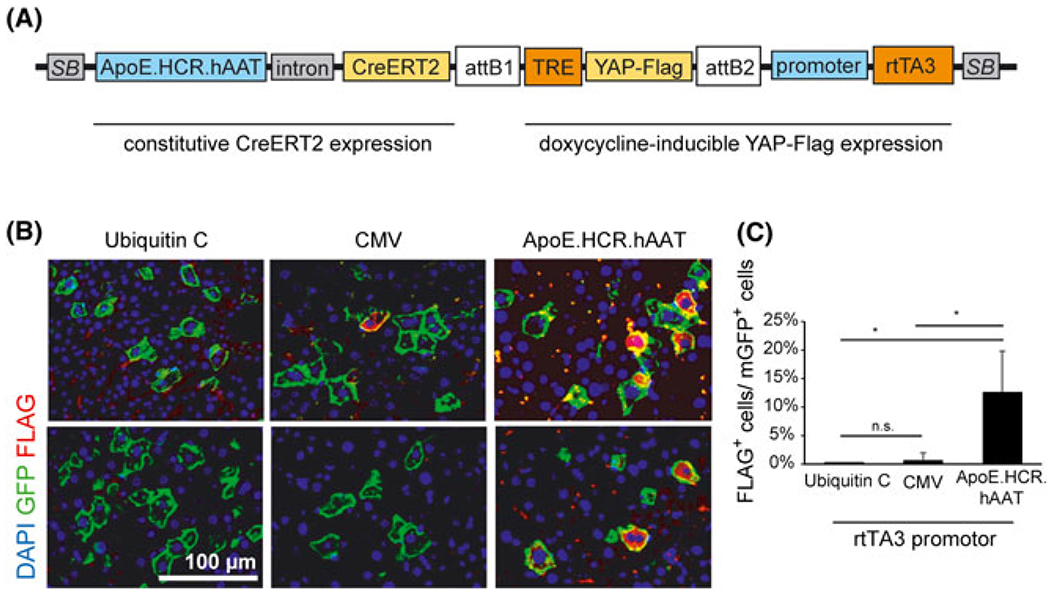

We next tested our construct for inducible gene expression using a FLAG-tagged human YAP expression construct (Figure 1B and 3A). However, by immunostaining, we were able to detect expression of the transgene in only 0.4% of transfected cells using the pSLIK-derived construct (Figure 3B, left). To test our hypothesis that the lack of inducible gene expression was the result of the low efficiency of the ubiquitin-C promoter to drive rtTA3 expression in the liver,30 we modified the original pSLIK-construct by replacing the ubiquitin-C promoter by a CMV promoter or the liver-specific ApoE.HCR.hAAT promoter that efficiently controls CreERT2 expression in our construct.

FIGURE 3.

Promoter-dependent expression of tetracycline-inducible transgenes in hepatocytes. A, pTC Tet transposon system with expression of a Tet-inducible Flag-tagged YAP protein (YAP-Flag). attB, recombined sites after integration of the entry vector cassette. Not drawn to scale. B, Representative immunostaining for Flag (red) and membrane-bound GFP (green) in the liver of R26R-mTmG mice injected with the pTC Tet transposon system and treated with tamoxifen and doxycycline. Expression of the rtTA3 element was driven by different promoters as indicated. C, Quantification of YAP-Flag-positive cells (FLAG+) of all transfected cells (mGFP+, positive for membrane-bound GFP) for different rtTA3 promoters as shown in (B) (n = 3 for ubiquitin-C and CMV promoter constructs; n = 4 for the ApoE.HCR.hAAT promoter construct). Error bars represent SD; n.s., not significant; *p < 0.05

Analysis of mice injected with the different constructs showed a low efficiency of the CMV promoter comparable to the ubiquitin-C promoter (Figure 3B and 3C), likely as a result of inactivation of the CMV promoter that is observed in hepatocytes in vivo.31 The ApoE.HCR.hAAT promoter, however, showed a significantly higher expression of the transgene by immunostaining, ranging from 7% to 23% of transfected hepatocytes (Figure 3B and 3C). Direct immunostaining of the transgene using an antibody that is reactive against human YAP protein revealed a slightly higher percentage of transgene expressing cells, ranging from 11% to 33% of all transfected cells (see Supporting information, Figure S1A and S1B). However, the results were not significantly different from those obtained with the FLAG-reactive antibody. Importantly, no transgene expression was detected in mice that were left off doxycycline (see Supporting information, Figure S1C).

3.4 |. Inducible shRNA expression in transfected hepatocytes

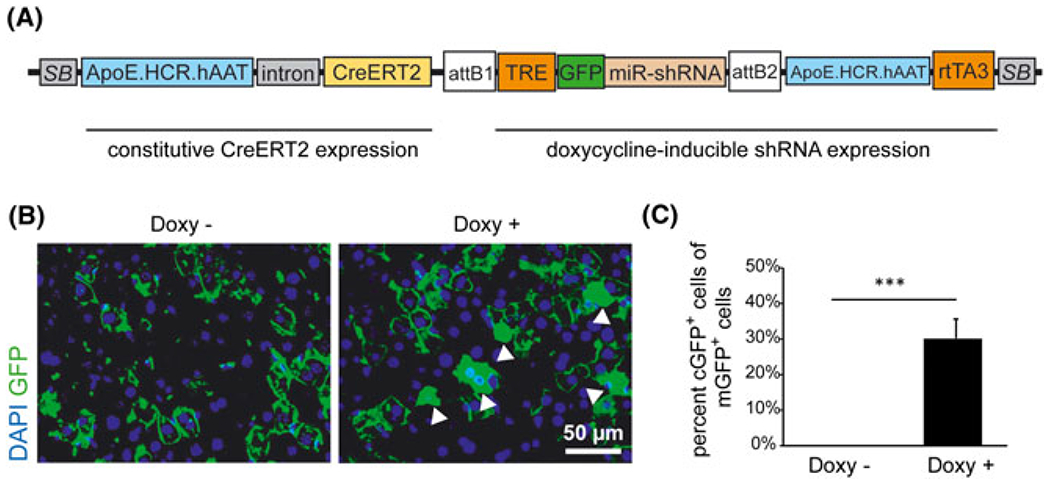

To assess the expression of inducible miR-shRNA from our construct, we injected mice with a transposon vector that harbors an inducible shRNA against mouse HNF4alpha that is co-expressed with GFP to visualize shRNA expression19 (Figure 4A). To drive rtTA3 expression, we used the ApoE.HCR.hAAT promoter that was found to be the most efficient promoter from our experiments for inducible transgene expression (Figure 3B and 3C). After tamoxifen and doxycycline treatment, we observed that, of all the transfected cells positive for mGFP, 26% to 36% also showed bright cytoplasmic staining for GFP (cGFP) indicative of shRNA expression (Figure 4B and 4C). Comparable to the transposon construct for inducible transgene expression (see Supporting information, Figure S1C), there was no staining indicative of inducible shRNA expression in mice not treated with doxycycline (Figure 4B and 4C). Interestingly, there were also a number of cells that showed intermediate levels of cytoplasmic green staining, which might correspond to lower levels of shRNA expression in these cells compared to bright green cells (see Supporting information, Figure S2A). However, because low levels of green fluorescence were not clearly distinguishable from autofluorescent hepatocytes in all samples, these cells were not counted as GFP-positive. Therefore, the percentage of shRNA-expressing cells might be underestimated by quantification methods using immunofluorescent staining. Because differentiation between cGFP and mGFP (i.e. that is also expressed in intracellular membranes encapsulating cellular organelles) could be difficult to discern in the R26R-mTmG model, we also injected our construct into mice harboring a R26R-Tom reporter gene. In these mice, targeted hepatocytes expressed the fluorescent dtTomato protein after Cre activation, which was accompanied by different levels of GFP expression and is comparable to the results that we obtained in R26R-mTmG mice (see Supporting information, Figure S2B). Even though the expression of cytoplasmic GFP is a marker for co-expression of shHNF4a, we were unable to detect any changes in HNF4A protein levels by immunostaining (see Supporting information, Figure S2C). The percentage of cells with nuclear HNF4A staining was not significantly different between transfected and nontransfected cells, nor in cells that show bright cytoplasmic GFP staining compared to transfected cells lacking cytoplasmic GFP (see Supporting information, Figure S2D). These findings are possibly a result of the comparably low efficiency of the miR-shRNA construct that is able to reduce Hnf4a mRNA expression by 67% when liver cells were targeted with an shHnf4a-expressing adenovector.22 Any expression differences in HNF4A protein levels could therefore be too low for detection by immunostaining. Additionally, integration of single copy transposons into the genome of hepatocytes32 could likely lead to lower levels of shRNA expression than those observed after adenovirus infection.

FIGURE 4.

Inducible shRNA expression in transfected hepatocytes. A, pTC Tet transposon system with expression of a Tet-inducible miR-shRNA. rtTA3 expression is driven by ApoE.HCR.hAAT promoter. The miR-shRNA is co-expressed with GFP for visualization of shRNA expression. Not drawn to scale. B, Immunostaining for GFP (green) in the liver of R26R-mTmG mice injected with the pTC Tet-shRNA transposon system (A). Mice were treated with tamoxifen followed by doxycycline (Doxy+, right) or were injected with tamoxifen alone (Doxy−, left). Cytoplasmic GFP (cGFP) staining (white arrowheads) represents expression of the GFP-shRNA construct. C, Quantification of transfected cells (mG+, positive for membrane-bound GFP) that are positive for cytoplasmic GFP (cGFP+) +/− doxycycline treatment as described in (B) (n = 3). Error bars represent SD; ***p < 0.001

In summary, our results show that inducible transgene expression or inducible shRNA expression can be achieved with transposable vector constructs in hepatocytes after HTVI. In combination with constitutive CreERT2 expression, our system can provide a versatile tool for the interrogation of target genes specifically in genetically engineered mouse models.

4 |. DISCUSSION

Over recent years, several methods for in vivo gene delivery have expanded the range of genetic tools available for studying liver disease in animal models. Hydrodynamic tail vein injection/transposon systems have been used to investigate the role of oncogenes, tumor suppressors and mediators of drug resistance in liver carcinogenesis,16,17,26 highlighting their importance in the research of liver disease. However, these systems rely in part on the injection of different vectors to transfect hepatocytes.25,26 However, because different constructs mostly integrate into different hepatocytes (Figure 1D and 1E), the use of this approach for specifically studying interactions between target genes might be limited. Therefore, systems that allow expression from a single vector were developed more recently and combined oncogene and shRNA expression led to the identification of relevant genes in liver biology.14,15 Refining these single vector systems will further broaden the application of this technique in liver research.

Our pTC Tet construct provides an advanced system for gene modification in hepatocytes, combining constitutive CreERT2 expression with inducible transgene expression or gene knockdown in a single vector. It is therefore especially valuable for the interrogation of target genes and screening approaches in genetically engineered models. However, our data indicate that the inducible systems might be activated only in a certain percentage of transfected hepatocytes (Figure 3C and 4C). For this observation, there could be several explanations, ranging from technical detection limits to intrinsic limitations of the vectors used for evaluation, such as promoter efficiency and choice of transgene. First, immunostaining might not able to detect low levels of protein expression, specifically in the liver, where fluorescence staining is often hampered by autofluorescence in hepatocytes.33 Additionally, the levels of protein detection might vary depending on the sensitivity of the antibodies used, which may account for the nonsignificant difference observed between staining with YAP and FLAG antibodies (see Supporting information, Figure S1B). Additionally, transgene stability might play a role in reduced transfection levels. For evaluation of our construct, we used an established vector for the expression of human YAP in vivo.21 However, YAP protein is inactivated in the quiescent hepatocytes leading not only to its cytoplasmic retention, but also to its degradation.34,35 Although the exact amount of YAP that is subject to degradation in hepatocytes remains elusive, the difference between detection of the inducible YAP-Flag construct (average of 13–23%) (Figure 3C; see also Supporting information, Figure S1B) and inducible GFP-shRNA expression (32%) (Figure 4C) indicates that transgene stability could play a role in the lower percentage of transgene-expressing hepatocytes. A further influence on inducible gene expression is the promoter driving rtTA3 expression (Figure 3B and 3C). Although the ApoE.HCR.hAAT promoter has been optimized for efficient hepatic transgene expression,36 its activity might be too low to induce adequate rtTA3 levels required for constant TRE activation. By contrast, even low levels of CreERT2 protein might be sufficient to induce genetic recombination of the Rosa26 gene locus, providing an explanation for the higher percentage of membrane GFP-positive cells compared to Tet-induced gene expression. The use of other highly efficient promoters, such as chicken β-actin/CMV enhancer (CAG) or elongation factor-1α (EF1α) promoters31 might therefore present further options for enhancing inducible gene or shRNA expression. Another factor influencing inducible gene expression could be insufficient concentrations of doxycycline in targeted hepatocytes. In the present study, doxycycline was administered by drinking water, which might be less efficient than other treatment routes such as oral gavage or doxycycline supplemented chow.37 Although transgene detection and stability are application dependent, further optimization of rtTA3 expression and activity using alternative promoters and induction methods could be useful for applications where higher levels of transgene or shRNA expression are required.

In our model, the percentage of GFP-shRNA expressing cells indicated high shRNA expression levels in approximately one-third of all transfected cells. However, we were not able to detect reduced target gene expression by immunofluorescence after 5 days of treatment with doxycycline, even in the cells with high cytoplasmic GFP (see Supporting information, Figure S2C and S2D). On the one hand, immunofluorescence might not be sufficient to detect changes in the expression levels of target proteins that are below a certain threshold. Particularly, the previously described reduction of Hnf4alpha mRNA expression to one-third of the original level22 might still result in an amount of antigen that is detectable by immunostaining. Because of the variability of HNF4A staining within untargeted control hepatocytes (see Supporting information, Figure S2C), we did not choose to use staining brightness as a surrogate marker for protein levels. Additionally, one limitation of our system might result from single copy integration of the transposon construct,32 which could result in lower shRNA levels compared to shRNA delivery by AAV or adenoviral vectors. The pSLIK lentiviral vector system provides a versatile platform for testing the efficiency of single shRNAs in vitro before injection into mice as a result of using the same entry vectors as those used for the generation of transposon constructs. However, promoter efficiency as well as multicopy integration of the lentivirus might still lead to considerable differences in shRNA levels between in vivo and in vitro systems. Detectable target reduction might not be necessary for many screening approaches and can be circumvented by using multiple shRNAs per target gene, similar to in vitro screening approaches.15 Nevertheless, if interrogation of the relevance of a single target gene is required, it could be important to assess the efficiency of individual shRNAs at a single copy level. More recently, elaborate systems have been developed to test for single copy efficiency in vitro.38,39 Implemented into the evaluation of shRNA constructs for transposon-mediated gene delivery, these systems can be used to improve target gene knockdown in vivo.

In summary, the pTC Tet construct reported in the present study can be readily used for several applications in liver research, specifically in Cre-driven genetic models. For evaluation of our construct, we used constitutive expression of CreERT2 in Rosa26 reporter mice to visualize transfected cells. When combined with genetic animal models harboring floxed target genes (e.g. tumor models such as Ptenlox/lox or Apclox/lox mice),40,41 our system can be used to selectively target hepatocytes in adult animals without breeding to liver-specific Cre mice. At the same time, specific genes of interest that might be of relevance in tumor development in these models can be interrogated in combination with the Tet inducible system, either with a transgene- or shRNA-based approach, or both. Our system therefore allows for easy and rapid testing of any gene of interest with a simple and efficient cloning procedure instead of cost and labor intensive cross-breeding to transgenic or knockout animals. An additional advantage of HTVI is the targeting of only a limited number of cells within the liver. This might not only be a better reflection of the human situation where only few cells acquire genetic changes that lead to tumor development, but also allows for the analysis of early disease stages. For example, clonal expansion of targeted cells at early timepoints can be easily visualized by immunostaining to detect a proliferative advantage or other changes induced by transgene expression or gene knockdown. Aside from tumor models, the analysis of clonal expansion of transfected hepatocytes can be applied in models of liver regeneration. Transgene or shRNA expression in hepatocytes after partial hepatectomy might enhance or inhibit regenerative proliferation, leading to smaller of larger clusters of transfected hepatocytes.

Importantly, all genetic changes will occur only in transfected cells. Therefore, phenotypes are likely to be more stringent than after injection with multiple vectors and targeting of different hepatocytes (Figure 1D and 1E). A further advantage of our system is the possibility for inducible expression that gives the opportunity to test the biological relevance of target genes at different time points in relation to Cre-mediated gene mutation. This is of special interest in genetic cancer models not only when inquiring about the influences of target genes on tumor initiation or maintenance, respectively, but also when applied to other models of liver disease such as regeneration, inflammation or steatohepatitis models.42,43 By implementation of the gateway cloning system that has been used in high throughput screening applications,23 our system can be easily used for in vivo screening and multiplexing approaches to identify novel disease-modifying genes. Depending on the model used, our system can expand the range of experimental approaches to identify relevant genes in tumor development, drug resistance to cancer therapies, regeneration and liver injury.14,15,44

Beyond the application in Cre-driven genetic models, our vector system can be modified for use in other models, such as Flp-FRT recombination. Additionally, the constitutive expression cassette can be replaced by expression sequences for oncogenes such as Nras to induce tumor development,8,44 further expanding its possible application in animal models of liver disease. Therefore, the vector system reported in the present study will expand the possibilities for interrogating the molecular biology of liver disease in vivo and will broaden the already extensive applications of transposon-mediated gene delivery by HTVI.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by Deutsche Krebshilfe, Germany (grant number 111289 to UE), the Lucile Packard Foundation for Children’s Health (Ernest and Amelia Gallo Endowed Postdoctoral Fellowship – CTSA grant number UL1 RR025744 to UE) and the NIH (grant number 4R01CA114102 to JS). We thank Dr Mark A. Kay for helpful discussion and plasmids and Dr Fabian Geisler and Dr Simone Jörs for advice on experimental protocols and for providing R26R-Tom mice. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest. No part of this work has been submitted elsewhere.

Funding information

Deutsche Krebshilfe, Germany, Grant/Award Number: 111289; Lucile Packard Foundation for Children’s Health (Ernest and Amelia Gallo Endowed Postdoctoral Fellowship) – CTSA, Grant/Award Number: UL1 RR025744; the NIH, Grant/Award Number: 4R01CA114102

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blachier M, Leleu H, Peck-Radosavljevic M, et al. The burden of liver disease in Europe: a review of available epidemiological data. J Hepatol. 2013;58:593–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Y, Meyer C, Xu C, et al. Animal models of chronic liver diseases. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;304:G449–G468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y, Tang ZY, Hou JX. Hepatocellular carcinoma: insight from animal models. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9:32–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malato Y, Naqvi S, Schurmann N, et al. Fate tracing of mature hepatocytes in mouse liver homeostasis and regeneration. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4850–4860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yant SR, Meuse L, Chiu W, et al. Somatic integration and long-term transgene expression in normal and haemophilic mice using a DNA transposon system. Nat Genet. 2000;25:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang TW, Yevsa T, Woller N, et al. Senescence surveillance of premalignant hepatocytes limits liver cancer development. Nature. 2011;479:547–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlson CM, Frandsen JL, Kirchhof N, et al. Somatic integration of an oncogene-harboring Sleeping Beauty transposon models liver tumor development in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17059–17064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen X, Calvisi DF. Hydrodynamic transfection for generation of novel mouse models for liver cancer research. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:912–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakai H, Montini E, Fuess S, et al. AAV serotype 2 vectors preferentially integrate into active genes in mice. Nat Genet. 2003;34:297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang L, Blouin V, Brument N, et al. Production and purification of recombinant adeno-associated vectors. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;807:361–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Y, Nunes FA, Berencsi K, et al. Cellular immunity to viral antigens limits E1-deleted adenoviruses for gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:4407–4411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Senis E, Fatouros C, Grosse S, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome engineering: an adeno-associated viral (AAV) vector toolbox. Biotechnol J. 2014;9:1402–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park F, Ohashi K, Chiu W, et al. Efficient lentiviral transduction of liver requires cell cycling in vivo. Nat Genet. 2000;24:49–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wuestefeld T, Pesic M, Rudalska R, et al. A Direct in vivo RNAi screen identifies MKK4 as a key regulator of liver regeneration. Cell. 2013;153:389–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rudalska R, Dauch D, Longerich T, et al. In vivo RNAi screening identifies a mechanism of sorafenib resistance in liver cancer. Nat Med. 2014;20:1138–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xue W, Chen S, Yin H, et al. CRISPR-mediated direct mutation of cancer genes in the mouse liver. Nature. 2014;514:380–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weber J, Ollinger R, Friedrich M, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 somatic multiplex-mutagenesis for high-throughput functional cancer genomics in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:13982–13987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hibbitt OC, Harbottle RP, Waddington SN, et al. Delivery and long-term expression of a 135 kb LDLR genomic DNA locus in vivo by hydrodynamic tail vein injection. J Gene Med. 2007;9:488–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shin KJ, Wall EA, Zavzavadjian JR, et al. A single lentiviral vector platform for microRNA-based conditional RNA interference and coordinated transgene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13759–13764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dow LE, Nasr Z, Saborowski M, et al. Conditional reverse tet-transactivator mouse strains for the efficient induction of TRE-regulated transgenes in mice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ehmer U, Zmoos AF, Auerbach RK, et al. Organ size control is dominant over Rb family inactivation to restrict proliferation in vivo. Cell Rep. 2014;8:371–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yin L, Ma H, Ge X, et al. Hepatic hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha is essential for maintaining triglyceride and cholesterol homeostasis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:328–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katzen F Gateway(®) recombinational cloning: a biological operating system. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2007;2:571–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madisen L, Zwingman TA, Sunkin SM, et al. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:133–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee SA, Ladu S, Evert M, et al. Synergistic role of Sprouty2 inactivation and c-Met up-regulation in mouse and human hepatocarcinogenesis. Hepatology. 2010;52:506–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ho C, Wang C, Mattu S, et al. AKT (v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1) and N-Ras (neuroblastoma ras viral oncogene homolog) coactivation in the mouse liver promotes rapid carcinogenesis by way of mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1), FOXM1 (forkhead box M1)/SKP2, and c-Myc pathways. Hepatology. 2012;55:833–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fan B, Malato Y, Calvisi DF, et al. Cholangiocarcinomas can originate from hepatocytes in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2911–2915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muzumdar MD, Tasic B, Miyamichi K, et al. A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis. 2007;45:593–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu F, Song Y, Liu D. Hydrodynamics-based transfection in animals by systemic administration of plasmid DNA. Gene Ther. 1999;6: 1258–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agca C, Fritz JJ, Walker LC, et al. Development of transgenic rats producing human beta-amyloid precursor protein as a model for Alzheimer’s disease: transgene and endogenous APP genes are regulated tissue-specifically. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen AT, Dow AC, Kupiec-Weglinski J, et al. Evaluation of gene promoters for liver expression by hydrodynamic gene transfer. J Surg Res. 2008;148:60–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bell JB, Aronovich EL, Schreifels JM, et al. Duration of expression and activity of Sleeping Beauty transposase in mouse liver following hydrodynamic DNA delivery. Mol Ther. 2010;18:1796–1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swenson ES, Price JG, Brazelton T, et al. Limitations of green fluorescent protein as a cell lineage marker. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2593–2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao B, Wei X, Li W, et al. Inactivation of YAP oncoprotein by the Hippo pathway is involved in cell contact inhibition and tissue growth control. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2747–2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yimlamai D, Fowl BH, Camargo FD. Emerging evidence on the role of the Hippo/YAP pathway in liver physiology and cancer. J Hepatol. 2015;63:1491–1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miao CH, Ohashi K, Patijn GA, et al. Inclusion of the hepatic locus control region, an intron, and untranslated region increases and stabilizes hepatic factor IX gene expression in vivo but not in vitro. Mol Ther. 2000;1:522–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cawthorne C, Swindell R, Stratford IJ, et al. Comparison of doxycycline delivery methods for Tet-inducible gene expression in a subcutaneous xenograft model. J Biomol Tech. 2007;18:120–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fellmann C, Zuber J, McJunkin K, et al. Functional identification of optimized RNAi triggers using a massively parallel sensor assay. Mol Cell. 2011;41:733–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fellmann C, Hoffmann T, Sridhar V, et al. An optimized microRNA backbone for effective single-copy RNAi. Cell Rep. 2013;5:1704–1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Horie Y, Suzuki A, Kataoka E, et al. Hepatocyte-specific Pten deficiency results in steatohepatitis and hepatocellular carcinomas. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1774–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Colnot S, Decaens T, Niwa-Kawakita M, et al. Liver-targeted disruption of Apc in mice activates beta-catenin signaling and leads to hepatocellular carcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17216–17221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kroy DC, Schumacher F, Ramadori P, et al. Hepatocyte specific deletion of c-Met leads to the development of severe non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. J Hepatol. 2014;61:883–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beraza N, Ludde T, Assmus U, et al. Hepatocyte-specific IKK gamma/NEMO expression determines the degree of liver injury. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2504–2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dauch D, Rudalska R, Cossa G, et al. A MYC-aurora kinase A protein complex represents an actionable drug target in p53-altered liver cancer. Nat Med. 2016;22:744–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.