Summary

In this study, we analyzed health-advertising tactics of digital medicine companies (n = 5) to evaluate varying types of cross-site-tracking middleware (n = 32) used to extract health information from users. More specifically, we examine how browsing data can be exchanged between digital medicine companies and Facebook for advertising and lead generation and advertising purposes. Our analysis focused on companies offering services to patient advocates in the cancer community who frequently engage on social media. We co-produced this study with public cancer advocates leading or participating in breast cancer groups on Facebook.

Following our analysis, we raise policy questions about what constitutes a health privacy breach based on existing federal laws such as the Health Breach Notification Rule and The HIPAA Privacy Rule. We discuss how these common marketing practices enable surveillance and targeting of medical ads to vulnerable patient populations without consent.

Keywords: dark patterns, digital medicine, privacy, health privacy

Highlights

-

•

Common marketing tools share sensitive health data with Facebook without patient consent

-

•

This study examines how health organizations track patients off of Facebook

-

•

We provide a coordinated disclosure timeline for companies involved

-

•

We share legal implications for existing federal health privacy federal laws

The bigger picture

The surveillance economy in healthcare has become a commonplace tool to target patient populations with ads on social media. How might sensitive personal health data be shared between health diagnostics and/or services to patients and Facebook? What are the legal implications under existing federal health privacy laws? This study’s methods take an infosec and coordinated disclosure approach to health ad targeting on Facebook.

In this study, we analyzed health-advertising tactics of digital medicine companies (n = 5) to evaluate varying types of cross-site-tracking middleware (n = 32) used to extract health information from users. More specifically, we examine how browsing data can be exchanged between digital medicine companies and Facebook for advertising and lead generation and advertising purposes. Our analysis focused on companies offering services to patient advocates in the cancer community who frequently engage on social media. We co-produced this study with public cancer advocates leading or participating in breast cancer groups on Facebook. Following our analysis, we raise policy questions about what constitutes a health privacy breach based on existing federal laws such as the Health Breach Notification Rule and The HIPAA Privacy Rule. We discuss how these common marketing practices enable surveillance and targeting of medical ads to vulnerable patient populations without consent.

Introduction

Digital medicine technologies offer convenience and can improve outcomes for chronically ill patients navigating their health journeys. An essential element for patients to adopt new health technologies is trust4. By providing digital tools designed to improve health, sometimes the most sensitive personal and medical information is shared. Digital medicine apps and services must maintain that trust by ensuring that all uses and privacy of personal health data are protected across the complex technology ecosystem that these companies utilize.

In this study, we analyzed advertising and marketing tactics of digital medicine companies (n = 5) to evaluate varying types of cross-site-tracking middleware (n = 32) used to extract health information from users. More specifically, we examine how browsing data can be exchanged between digital medicine companies and Facebook for advertising and lead generation to target a specific patient population. The examples we analyzed focused on companies offering services to patients in the cancer community who frequently engage on social media. We co-produced this study with public cancer advocates leading or participating in breast cancer groups on Facebook.

The ways in which internet browsing data reveal facts about health to advertisers can be deceptive when patients seek knowledge on the internet. A “dark pattern” is a user interface design that benefits an online service by nudging, coercing, or deceiving users into making unintended and potentially harmful decisions.5 “Privacy Zuckering” is a known type of dark pattern, originally identified by Tim Jones at Electronic Frontier Foundation in 2010. Privacy Zuckering happens when a user is tricked into publicly sharing more information than a user really intended to share.6 When this specific type of dark pattern is employed to elicit public data from patient populations online, one might consider the sensitivity of health data involved. In the field of health privacy and cybersecurity, when protected health information (PHI) is leaked or stolen, the potential harms include physical, economic, psychological, reputational, and societal harms.7,8

With the explosion of social media over the past decade, online communities of patients exist on social media platforms. Health and pharmaceutical companies spent almost one billion on just Facebook mobile ads in 2019.9 Patient populations who have shared knowledge about their health by engaging on social media have generated increasingly large marketing channels for digital medicine and pharma companies to target ads to patient populations.10

Social media platforms like Facebook have become common places for patients to seek support from their peers online, while social media is filled with ads relating to health conditions.11 We focus solely on Facebook’s ad model in this analysis and may broaden it to other social media platforms in future studies. While this analysis does not tie specific harms to dark patterns utilized, examples of harm when publicly exposing health information can include risk of discrimination, psychological harm, and exposure to fraud or scams based on the health information shared. In a broader context, inability to protect patients from such harms may hinder adoption of life-saving diagnostics or digital medicine interventions.

In this study, we focused on cross-site-tracking middleware used by digital medicine companies within the cancer community. We chose this focus because these tools may make cancer-patient populations vulnerable to online scams, medical misinformation, and privacy breaches.7 The patient communities’ digital footprint expanded exponentially when patients turned to social networks such as Facebook seeking support, knowledge, and advice during a health diagnosis.10 Genetic-testing companies offering cancer diagnostics, health services, and patient communities can all become unwitting participants in digital dark patterns when posting or engaging with ads on Facebook.

We analyzed cancer-related health companies (n = 5) using third-party cross-site-tracking tools to patients’ behavior between their own websites and Facebook. This process identified how companies are able to leverage Facebook’s health-related ad targeting tools to generate data about cancer-patient advocates on social media as marketing leads. Our analysis showed that only 3 of the 5 companies did not comply with their own policies or claims about privacy. Two of the 5 companies, Ciitizen and Invitae, targeted ads but were consistent with their privacy policies. Yet, all companies in our analysis created digital footprints to enable ongoing tracking and surveillance of patient populations on Facebook. Findings of non-compliance were similar in a recent cross-sectional study demonstrating that in an ecosystem of medical and digital health or digital medicine apps available on Google Play, only 47% user data transmissions complied with each company’s own privacy policies.11

The scope of this study focused on examples that may fit the definition of Federal Trade Commission’s personal health record (PHR) vendor3 and also examples of CLIA-certified diagnostic testing laboratories that are likely HIPAA-covered entities.12 Some examples deal with PHI if they are HIPAA-covered entities.13 Other examples may qualify as “PHR identifiable health information,” as defined by the Health Breach Notification Rule. By following the reproduction steps, the common theme in examples we identify shows how each company tracks patients off Facebook while targeting ads to reach patients on Facebook. Three of the 5 used third-party tools reidentify patients as leads using common advertising tools. These companies may have unknowingly exposed more about the patient populations they serve through Facebook by creating rich digital footprints of patient populations who interact with their ads and services.

There are policy loopholes for the HIPAA Privacy and Security Rules that disqualify certain companies, “HIPAA Covered Entity.” When generating data outside the digital walls of a HIPAA-covered entity or “Business Associates Agreement,” patients are mostly on their own with respect to understanding how companies utilize their personal and health data, especially when asking questions about their health conditions on social media. Despite the known gaps in regulation, end-user license agreements remain the standard for eliciting consent for data use with most digital toolsets and platforms, and patients are typically on their own in assessing the risks of using third-party marketing tools.14 While utilizing similar marketing practices, the line between “market” research and ethical human subject research remains unclear when patient populations lack comprehensive privacy regulation in the United States.

Results

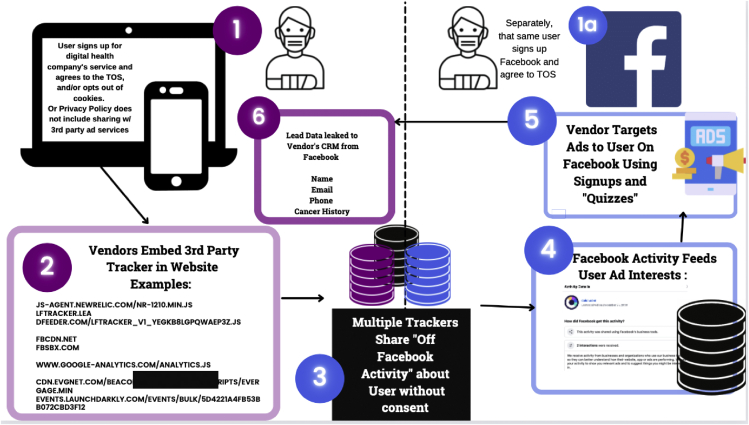

Through this study, we were able to demonstrate and reproduce how sensitive data flow from our examples of digital medicine vendors to Facebook through cross-site trackers or content delivery networks (CDNs). Some of those same vendors (2 out of 5) used services that target ads on Facebook in order to reidentify users as marketing leads. Trackers and types of CDNs passing data between Facebook and digital medicine vendors varied widely. The common user experience may be described as follows, although steps may vary by vendor and user (Figure 1).

Step 1: User signs up for digital medicine app or genetic testing and agrees to the company’s (i.e., the vendor’s) terms of service.

Step 1a: Separately, the user creates an account on Facebook or already has an established account.

Step 2: Vendors embed third-party tracker in a vendor’s website.

Step 3: Multiple third-party trackers share Off-Facebook Activity.

Step 4: Off-Facebook Activity from the vendor updates user “ad interests” algorithms on Facebook.

Step 5: Facebook’s predictive algorithms begin to promote health-related ads to the user based on health interests.

Step 6: The vendor targets ads to users with specific health interests and, in some cases, uses quizzes or sign-up forms to enrich their lead data. Lead data are passed from Facebook to the vendor’s customer relationship management (CRM) system.

Figure 1.

Process for enabling data to pass between digital medicine companies and Facebook

While these steps vary in detail between participants who shared their off-Facebook tracking, the remainder of this analysis will detail the examples of vendors where we have examples of Off-Facebook Activity and ad targeting that did not match privacy policies and/or user settings. While Facebook does not disclose how their proprietary algorithms predict health interests about a user, further research is needed to understand how health ad targeting is available based on data collected from Facebook about users’ web-browsing behavior.

We outline specific examples where off-Facebook tracking showed examples of digital medicine companies in JSON archives of participants. While this is a small sampling of a larger population and digital ecosystem, these examples highlight how cross-site tracking works when users navigate between PHRs and social media while being tracked through web browsing.

Example #1: Color Genomics

One participant identified Color Genomics (also known as Color Health) in their Off-Facebook Activity JSON files. Color Genomics provides a DNA health report that analyzes up to 74 genes that fall into 3 categories: 30 genes that impact risk for breast (including the breast cancer genes BRCA1 and BRCA2), ovarian, uterine, colon, melanoma, pancreatic, stomach, and prostate cancers. Color Genomics is a CLIA-certified lab and a HIPAA-covered entity.

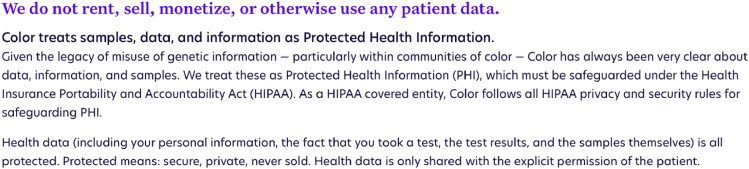

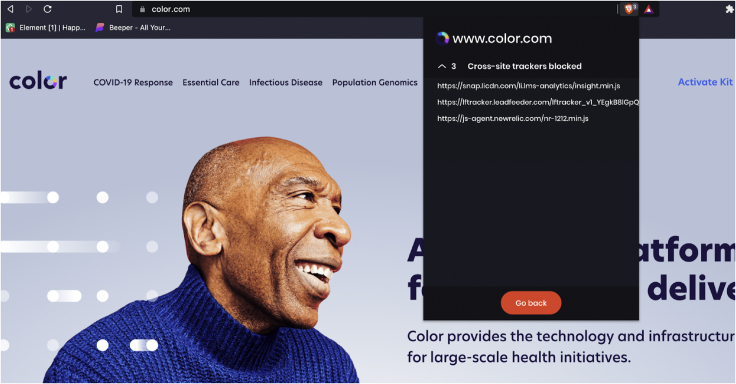

With respect to privacy practices, Color states that they require a user’s authorization before disclosing PHI for marketing purposes in a notice dated May 25, 2018, at the time of our study. They represent to users that they do not rent, sell, or otherwise use patient data (Figure 2). One participant noted their cookies on Color’s website are turned off, which indicates that users did not authorize sharing of information for advertising purposes. Using the reproduction steps outlined in experimental procedures, we identified 3 cross-site trackers (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Color’s representation to users on coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) testing

Figure 3.

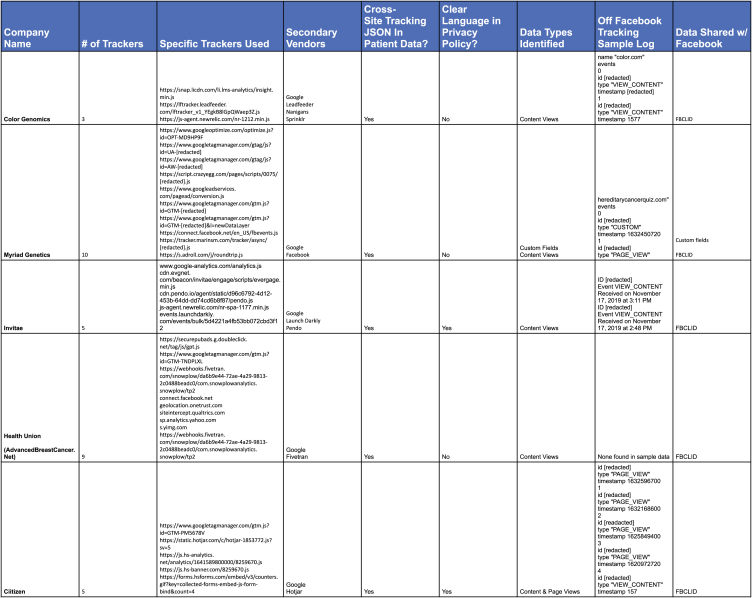

Summary of third-party trackers by company

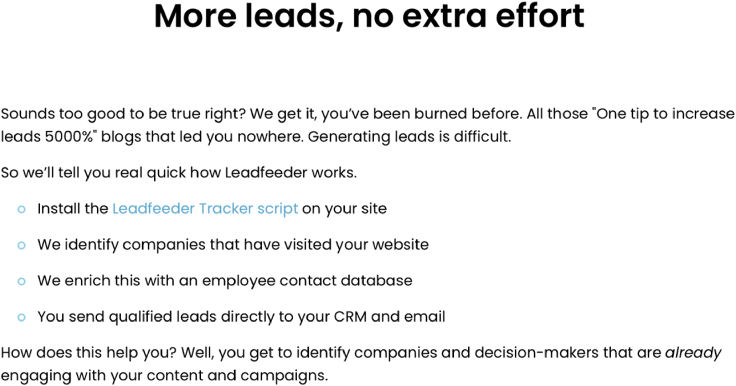

Notably, Color used Leadfeeder, which is a marketing solution that enables companies to reidentify leads based on their visits to a website and enrich the data without explicit consent from users (Figure 4).15 From the Facebook ad side, we also looked at trackers being used by Color when users click on their ads. In one ad, the “shop now” button goes to the following URL, providing data to a social advertising service called Nanigans (Figure 5).16 Here is one example of an ad link passing from Facebook to Nanigans, where we have redacted the IDs exposed in the URLs: http://api.nanigans.com/target.php?app_id = [redacted]&nan_pid = [redacted]&target = https%3A%2F%2Fhome.color.com%2Ft%2Fstart%3Futm_source%3DFacebook%26utm_campaign%3DProspecting_OC%26utm_medium%3DROF%26utm_content%3Dvideo%26code%3DVAF6OM0JMH%26%26nan_pid%[redacted]%26ad_id%[redacted].

Figure 4.

Cross-site trackers for Color Genomics

Figure 5.

How Leadfeeder’s service reidentifies patients

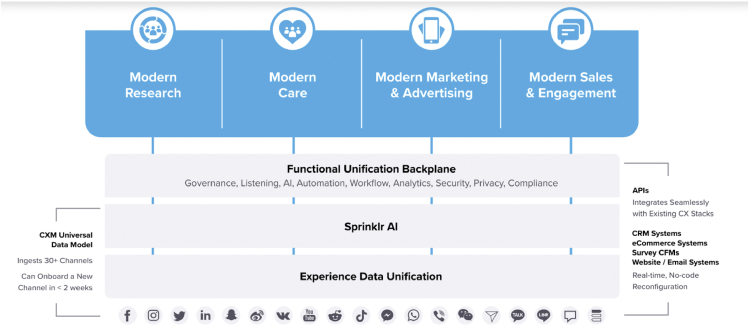

As a third-party marketing service, Nanigans was acquired by a data-analytics company called Sprinklr in 2019.17 Sprinklr provides a service to companies called Unified-CXM, which brings together user interests across platforms. For example, Unified-CXM works across platforms to reidentify and join data about users across social media platforms (Figure 6).18 We did not have visibility into Color’s specific use of Nanigans, nor did we receive a response during our disclosure process. The history of ads that we originally analyzed were removed from Facebook’s Ad Library during the disclosure process, sometime before December 2021.

Figure 6.

Sprinklr and Nanigans Unified-CXM, used by Color Genomics

Example #2: MySupport360 and HereditaryCancerQuiz.com

One participant identified MySupport360.com and HereditaryCancerQuiz.com in their JSON files. These services are patient-facing hereditary cancer awareness campaigns created by Myriad Genetics that focus on three of the company’s genetic tests. Myriad Genetics is a CLIA-certified lab that provides diagnostic testing for cancer genetics. Myriad’s tests provide patients and healthcare providers with insights into inherited cancer risk and molecular features of cancer tissues and also has genetic tests related to psychiatric drugs and other conditions. As a covered entity under HIPAA, Myriad’s lab, MySupport360, and HereditaryCancerQuiz.com may or may not be covered by the FTC's breach-notification rules. The MySupport360 site specifically provides consumers with tools to find genetic tests for the BRCA genetic mutation and other genes without engaging directly with a physician, yet they are a diagnostic lab covered by HIPAA.

Through our analysis from participants, we identified two instances of Off-Facebook Activity as late as June 24, 2021, in participant JSON files. The user did not provide written authorization to MySupport360, HereditaryCancerQuiz.com, or Myriad Genetics to disclose any information to Facebook for marketing, ad targeting, or any other purpose. Myriad, the parent company of MySupport360, showed targeted ads on Facebook in the form of a “hereditary cancer quiz” to gather personal details about a person’s health and family history. It is not disclosed to users that PHI for hereditary cancer entered in the quiz or input form will be used as lead information for Myriad.

The ads we originally analyzed from Facebook’s Ad Library have since been removed without explanation. This example came from a specific user clicking on the hereditary cancer quiz link in the following format: https://www.hereditarycancerquiz.com/?fbclid=[redacted]_0AJ_[redacted].

Before ads were removed, when a user clicked on the ad from Facebook to Myriad’s quiz, a parameter called “FBCLID” was used as shown in the example above. FBCLID stands for Facebook Click Identifier.18 Since mid-October 2018, a FBCLID has been appended to all outgoing links in Facebook.

The software development kit (SDK) documentation from Facebook on FBCLID indicates that data are gathered about the user when clicking on an ad.19 For example, once the FBCLID ID is created and passed to Crowdtangle, the landing page quiz appears as if it is a public-health service, and this health quiz passes personal health information to both Facebook and Myriad Genetics as lead information.

Information collected in the quiz included the following:

-

•

Date of birth

-

•

Sex

-

•

Are you of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry?

HereditaryCancerQuiz.com also included some of the more invasive trackers out of the examples we identified and posted similar ads by Myriad Genetics. For example, HereditaryCancerQuiz.com was the only example we identified with Facebook Pixel installed directly on their website (Figure 3). Further, we noted one custom field being shared between Myriad and Facebook. In legal and policy analysis, we draw a comparison with the way that Flo Fertility had shared custom fields with Facebook. Given that custom fields had been created for users, it would be helpful for Myriad to disclose what type of data had been shared.

Example #3: Invitae

Invitae is a CLIA-certified diagnostic testing lab that offers clinical genetic tests. The company states the following:

Invitae’s mission is to bring comprehensive genetic information into mainstream medical practice to improve the quality of healthcare for billions of people. From day one, patients owning and controlling their genetic data has been one of our core principles.

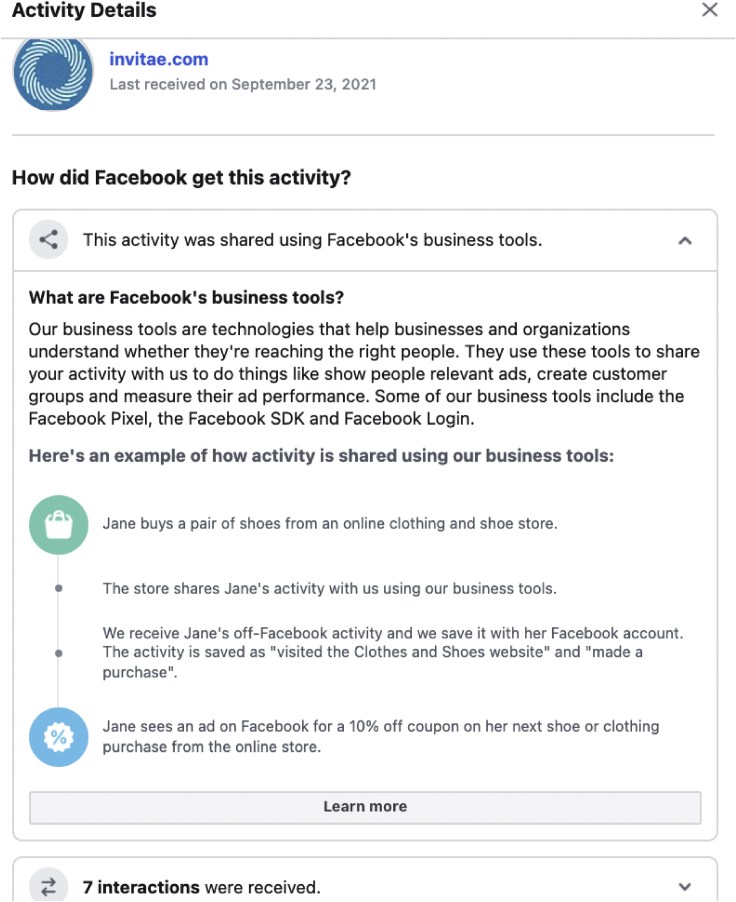

Two participants showed Invitae in their JSON files in the form of content views and page views on their website (Figure 7). However, Invitae is perhaps the most benign example in this report compared with the others. Invitae transparently discloses that they use cookies and clearly states that they share information with advertisers. Invitae is a CLIA-certified diagnostic testing company. Invitae’s privacy practices clearly outline how cookies are used. Their cookie policy states the following:

We use other tracking technologies similar to cookies, such as flash cookies, web beacons, or pixels. These technologies also help us understand how you use our Services in the following ways:

-

•

“Flash Cookies” (also known as “Local Shared Objects” or "LSOs") to collect information about your use of our Services. Flash cookies are commonly used for advertisements and videos.

-

•

“Web Beacons” (also known as “clear gifs”) are tiny graphics with a unique identifier, similar in function to cookies. Web beacons are embedded invisibly on web pages and do not store information on your device like cookies. We use web beacons to help us better manage content on our Services and other similar reasons to cookies.

-

•

“Pixels” track your interactions with our Services. We often use pixels in combination with cookies.

We generally refer to cookies, web beacons, flash cookies, and pixels as “cookies” in this Policy.

Figure 7.

Example of cross-site tracking from Invitae

At the time of this study, we identified five cross-site trackers on Invitae’s main website (Figure 3). The majority of these middleware tools used cookies to improve operation of Invitae’s site, not to specifically gather leads or reidentify website visitors as leads. Invitae does not show ads targeted to users passing through Crowdtangle. While page views passed to Facebook do not reidentify patients as leads or pass custom fields to Facebook, any users clicking on Facebook ads are then sharing information with Facebook about their health interests. These ad interests are then available for other companies to retarget the patient on Facebook.

Example #4: Health Union

Participants identified ads for AdvanceBreastCancer.net in their social media feeds but did not find cross-site activity in their JSON files. These ads were run by a digital medicine service called Health Union. Health Union states that their online health communities provide support, information, and a sense of connection across a variety of chronic health conditions in oncology, immunology, neurodegenerative, genetic, and general medicine.

Health Union’s business solutions are targeted to pharma, marketing research, and clinical trial services as their primary customer to “enable companies to connect and engage in transparent ways with highly qualified people who interact with our communities.” AdvancedBreastCancer.net is one of several online communities run by Health Union. We identified five cross-site trackers or CDN’s in our analysis of AdvancedBreastCancer.net (Figure 3).

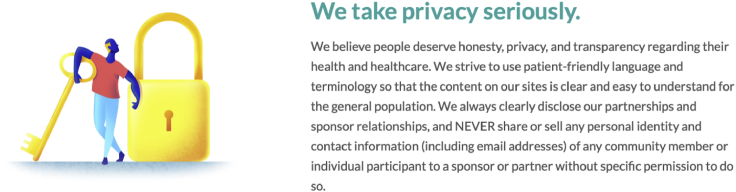

Notably, we saw a disconnect between Health Union’s claims about privacy and their activities. The company claimed on their main page that they never sell health information without “specific permission to do so.” (Figure 8). However, Health Union’s privacy policy stated that users must submit a request to opt out the sale of information to privacy@health-union.com or visit the Walt Disney Company’s privacy rights page (Figure 9). While Health Union did not respond to us directly during the coordinated disclosure process with Cert.org, the company updated their privacy policy on December 28, 2021.

Figure 8.

Example messaging to patients from Health Union

Figure 9.

Health Union: Contact Walt Disney Company to opt out of the sale of personal information

Example #5: Ciitizen

Ciitizen is a service that enables patients to organize health records from multiple sources, such as different EHR systems.20 Ciitizen was acquired by Invitae, example #3, in 2021.21] This is one of the two more benign examples we analyze in our report. Ciitizen disclosed in their privacy policy how they use cookies and provided statements about how they share information with advertisers. No custom fields were identified in the JSON files of the participants in our study, only views of web pages and content on Ciitizen’s website. The data passed back to Facebook are shown only as content views on Ciitizen’s service, which include the dates that a patient viewed content on Ciitizen’s site. The ads we reviewed for Ciitizen in Facebook’s Ad Library have since been removed from Facebook’s Ad Library and from JSON files. Yet, any ads created by Ciitizen and other examples in this study feed predictive algorithms to Facebook through cross-site tracking, which enables retargeting of patients based on their health interests. Notably, Ciitizen provided the most comprehensive response to our initial report during coordinated disclosure. In direct response to revelations in our report, both Ciitizen and Invitae reported back that they took down Facebook’s ad tools. Ciitizen is further assessing the impact of ad targeting tools they are using on other social media sites.

Legal and policy analysis

At the time of this study, the FTC has not once enforced the Health Breach Notification Rule since its creation in 2009.3 Both HIPAA-covered entities and health services covered by the FTC will need to evaluate these real-world examples that may apply to enforcement of the FTC’s Health Breach Notification Rule. There are a range of questions to consider. Do some of the examples in this study fit the definitions in the Health Breach Notification Rule? To what extent does information “managed, shared, and controlled by or primarily for the individual” fit legal definitions in this rule for different types of companies outlined? Are general statements about marketing practices in privacy policies sufficient “disclosure” for purposes of the Health Breach Notification Rule? Given the sensitive health information exchanged between Facebook and HIPAA-covered entities, does Facebook itself fit the legal definition of a vendor of PHRs? Where do we draw ethical lines between market research and medical/human subject research in this exploding digital medicine ecosystem? What constitutes a “breach” if patient data are combined with existing information on other platforms or if patients are tracked across platforms?

We hope that our analysis provides helpful insight on real-world data from the perspective of these patient populations. Notably, Facebook announced in November 2021 that they would be removing all detailed ad-targeting endpoints for sensitive health information.22

A recent FTC settlement with a digital medicine app called Flo may serve as a legal precedent for the comparisons in our study.23 In this FTC settlement, Flo handed users’ health information out to numerous third parties, including Google, Facebook, marketing firm AppsFlyer, and analytics firm Flurry.24 Notably, the Flo settlement did not include a violation of the Health Breach Notification rule but rather was focused on deceptive statements to users, per section V of the FTC Act. One of the key activities from Flo’s case was using CDN trackers to pass custom fields about users’ menstrual cycles directly to Facebook using custom fields. Based on our understanding of the Health Breach Notification Rule, examples we share in this report must meet the following criteria to qualify as a “breach”:3

-

1.

The business or service must “offer or maintain a personal health record.”

-

2.

The PHR vendor’s terms of service and privacy disclosures must disclose sharing of personally identifiable information with third parties.

-

3.

If unauthorized access to PHR identifiable health information occurs, the PHR vendor must notify users of a breach.

Further research is necessary to enumerate ways that populations on the platform may have been targeted by malicious actors, scams, and medical misinformation through the same tools and methods we have identified. It would be beneficial to investigate how these middleware options can be utilized to discriminate against patients and potentially target large-scale populations with medical misinformation. Upon discovering health apps using cross-site tracking, some of the advocates who reported their findings that they felt “duped,” “exploited,” and “violated” after seeing ways that digital medicine services and genetic testing companies were tracking the cancer community’s Off-Facebook Activity.

Discussion

Health privacy is a basic requirement in digital medicine for reducing the abuse of power and supporting patient autonomy.8 We demonstrated that personal data and personal health data can be easily obtained without the aid of highly sophisticated cyberattack techniques but with rather commonplace third-party advertising tools. While privacy Zuckering dark patterns are deceptive, it is not clear that companies in our study intended to deceive their users. Nor is it clear the extent to which these companies were aware how tools are feeding data about users’ health information to Facebook as they engage with ads.24

While tools we identified are not inherently good or bad, applying commonplace advertising tools designed for social media marketing can expose sensitive health information in the form of leads. These marketing tools reveal a dark pattern used to track vulnerable patient journeys across platforms as they browse online, in some ways unclear to the companies and patient populations who are engaging through Facebook.

While the digital medicine ecosystem relies on social media to recruit and build their businesses through advertising-related marketing channels, these practices sometimes contradict their own stated privacy policies and promises to users. As previously stated, the authors have disclosed findings through proper channels prior to the submission of this work to allow each company time to respond and notify users if a breach occurred. We hope that the details around these vulnerabilities inspire deeper introspection into the tools and tactics that PHR companies utilize to increase their reach toward the patients they seek to serve and protect.

Experimental procedures

Resource availability

Code from this study is open source and provided by The Markup and Mozilla Foundation and from https://github.com/the-markup/blacklight-collector and https://github.com/EFForg/privacybadger.

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Andrea Downing (andrea@lightcollective.org).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Cross-site-tracking tools

Advertising cookies are text files that enable companies to build profiles of user interests in order to target ads (Figure 3). Our method was to take the following reproduction steps to identify digital medicine companies who use advertising cookies to track users off of Facebook.

-

1.

Download the full archive history of “My Facebook Information.”

-

2.

For each of their archives, we asked participants to specifically review the audit log of your_off-facebook_activity.json.

-

3.

Within this JSON file, we asked participants to provide the list of health apps that appeared in their history.

-

4.

We then took this list to check each vendor’s website for third-party ad trackers. This can be done with any basic tool such as Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Privacy Badger (https://privacybadger.org) or The Markup’s Black Light Tool (https://themarkup.org/blacklight).25,26

-

5.

If third-party ad trackers were found, we checked the privacy policy to see what was disclosed to users and whether that matched what we found.

-

6.

We checked Facebook’s disclosures to users about how PHI is shared and how it is used.

-

7.

As a final step, we checked Facebook’s Ad Library to check each advertising history and the types of ads posted (Figure 3).

Coordinated disclosure and timeline

While the CDN and cross-site-tracking tools utilized in our study are commonly used in digital advertising, 3 of the 5 digital medicine companies in our analysis used third-party tools to reidentify or retarget users as marketing leads without clear language in their privacy policies or authorization from users. Given that our analysis uncovered examples that may qualify as a breach of personally identifiable information either under HIPAA or the Health Breach Notification Rule, a crucial step to our research was a coordinated disclosure with companies involved. See legal and policy analysis to see the steps required to qualify as a breach.

According to CERT.org, coordinated disclosure of a vulnerability requires multiple stakeholders to analyze a vulnerability to be able to disclose it to the public and provide guidance on how to mitigate or fix it.27 Vulnerabilities and disclosures to impacted parties often follow unique paths where no two disclosures are alike. Through the process of coordinated disclosure, our goal has been to work in good faith with various stakeholders and make sure the vulnerability is addressed accordingly and that the correct information reaches the public.

When attempting to locate coordinated disclosure policies for some of the impacted companies, we were unable to find points of contact at 2 of the 5 companies to coordinate our findings. The companies we analyzed only represented a small sampling of PHR vendors or genetic testing companies, and it became apparent it would not be feasible to reach out to thousands of other potentially impacted companies who target ads. Therefore, we reached out to Cert.org to assist with multi-party disclosure to impacted vendors. Cert.org provided guidance and helped navigate coordinated disclosure to impacted companies.

Cert.org provided assistance to ensure we were following proper guidance for coordinated disclosure in 2021.

-

•

November 15, 2021: Attempted to locate points of contact for disclosure at each company but realized that direct coordination would not be possible. (Disclosure was not possible for some parties if their websites did not provide a coordinated disclosure policy or a security point of contact. Further, this study only analyzed a small sampling of 5 companies, where impacted health vendors using these practices number in the thousands.)

-

•

November 24, 2021: Disclosure to BioISAC.

-

•

December 1, 2021: Disclosure to Cert.org.

-

•

December 10, 2021: Disclosure to Ciitizen and Invitae.

-

•

December 13, 2021: Disclosure to Color Genomics.

-

•

December 16, 2021: Submitted report to FTC.

-

•

December 17th: Disclosure to Cert.org to request help with multi-party disclosure.

-

•

December 31st: One of 5 vendors (Health Union) updated their privacy policies.

-

•

January 2022: Invitae and Ciitizen responded to disclosure, initiating investigation into third-party tracking tools.

-

•

January 2022: Facebook removes all sensitive health ad targeting endpoints.

-

•

February 6, 2022: Preprint of our study covered in Wired.

-

•

March 8: Disclosure to Myriad Genetics when invited to join case created by Cert.org.

-

•

May 6, 2022: As of this date, third-party middleware for each company in our analysis had either been removed by all companies or privacy policies have been updated by companies in this study.

Cert.org solicits and posts authenticated vendor statements and references relevant vendor information in vulnerability notes. While one company requested detailed notes, we did not provide JSON files of participants to the companies involved in order to protect the privacy and user IDs of participants. Myriad Genetics provided specific changes to its policies as a result of the findings, but it said that “no personal health information” from its quiz products is used to target individuals and that it complies with Facebook's healthcare advertising policies. Color Genomics provided public comment that it hasn't actively used two of the cross-site trackers (Leadfeeder and Nanigans).

During our coordinated disclosure, it is notable that Ciitizen and Invitae were the only examples that responded to our disclosure and formally shared that they were investigating the privacy of these third-party tools further. While Ciitizen and Invitae showed only content views and page views in participants’ JSON files, Ciitizen and Invitae responded by removing all social media ad targeting tools to further assess the impact of these tools on their users.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this publication was provided by The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. We would like to acknowledge the public patient advocates who provided their Off-Facebook Activity as collaborators in our study. We have included only those who wish to be acknowledged: Fred Trotter, CTO of Careset Systems, author of Meta Measles in 2019; Jill Holdren, co-founder of The Light Collective; Tiah Tomlin-Harris, founder, My Style Matters; Lori Adelson, BRCA community advocate; Casey Quinlan, Mighty Casey Media; Shoshana Schwartz, BRCA community advocate; and Valencia Robinson, board member of National Breast Cancer Coalition.

Author contributions

A.D. gathered JSON files and examples from participants and served as the point of contact with coordinated disclosure. E.P. provided technical/scientific oversight and helped with analysis.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Inclusion and diversity

The author list of this paper includes contributors from the location where the research was conducted who participated in the data collection, design, analysis, and/or interpretation of the work. One or more of the authors of this paper self-identifies as living with a disability.

Published: August 15, 2022

Data and code availability

We co-created this analysis with patient advocates who are listed in our acknowledgement section. Public patient advocates in the hereditary cancer community (n = 20) were invited to participate in co-production of this research at a response rate of 50% (N = 10). These patient advocates include a small sampling of the broader population. Specifically, public metadata for hereditary cancer communities on Facebook consist of about 73 groups ranging in size from 36 to 13,000 people.1 Out of this population, 3 of the 10 participants were active administrators of at least one Facebook support group for breast cancer. All participants were a member of at least one breast cancer support group over a time period between 2008 and 2021.

Facebook has a tool in user settings that allows users to see companies tracking browsing data in Off-Facebook Activity, which can also be downloaded into an archive of JSON files.2 The patient advocates who co-produced our data (N = 10) were asked to download their full Facebook archives as JSON files. Participants could also look at the data via Facebook’s user interface using Off-Facebook Activity in their user settings and provide screenshots. Each participant checked if they found digital medicine apps in their Off-Facebook Activity JSON files and then verified whether these users of PHR vendors or HIPAA-covered Entities had authorized access to their data. In order to determine whether an individual authorized access, we first analyzed each digital medicine company’s cross-site-tracking tools.2 We then compared the tools each company used with their privacy policies and applied the FTC’s September 2021 guidance on the Health Breach Notification Rule.3 As a final step, we checked Facebook’s Ad Library to identify types of ads being run by each company. We also examined how each ad’s URL passed data from Facebook to third parties. From the 5 companies we identified in JSON files, we identified 27 third-party CDNs.

References

- 1.Loeb S., Massey P., Leader A.E., Thakker S., Falge E., Taneja S., Byrne N., Rose M., Joy M., Walter D., et al. Gaps in public awareness about BRCA and genetic testing in prostate cancer: social media landscape analysis. JMIR Cancer. 2021;7:e27063. doi: 10.2196/27063. PMID: 34542414; PMCID: PMC8550715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Facebook. “Off-Facebook Activity: Control Your Information.” (2021) Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/off-facebook-activity.

- 3.Trade Commission F. Complying with the FTC's Health Breach Notification Rule. 2010. Complying With The Ftc's Health Breach Notification Rule.https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/business-center/guidance/complying-ftcs-health-breach-notification-rule Retrieved. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trotter F., CTO . 2018. “Trying to Avoid a Crisis of Confidence in Healthcare Cybersecurity.” Cyber Cure, Season Cyberweek 2018.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZyeG66BcCr0 CyberCure. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones T., Brignull H., et al. “Privacy Zuckering.” Types of Dark Patterns. 2022. https://www.deceptive.design/types/privacy-zuckering

- 6.Mathur A., Acar G., Friedman M.J., Lucherini E., Mayer J., Chetty M., Narayanan A. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 3. CSCW; 2019. Dark patterns at scale: findings from a crawl of 11K shopping websites; pp. 1–32. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agrafiotis I., Nurse J.R.C., Goldsmith M., Creese S., Upton D. A taxonomy of cyber-harms: defining the impacts of cyber-attacks and understanding how they propagate. J. Cybersecur. 2018;4:tyy006. doi: 10.1093/cybsec/tyy006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandl K.D., Perakslis E.D. HIPAA and the leak of “deidentified” EHR data. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;384:2171–2173. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2102616. Epub (2021 Jun 5). PMID: 34110112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tiku N. The Washington Post; 2020. Why Facebook Is Filled with Pharmaceutical Ads.https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2020/03/03/facebook-pharma-ads/ [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lecher C. the Markup; 2021. How Big Pharma Finds Sick Users on Facebook – the Markup.https://themarkup.org/citizen-browser/2021/05/06/how-big-pharma-finds-sick-users-on-facebook [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tangari G., Ikram M., Ijaz K., Kaafar M.A., Berkovsky S. Mobile health and privacy: cross sectional study (2021); 373 :n1248 doi:10.1136/bmj.n1248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Code of Federal Regulations. “42 CFR Part 493 -- Laboratory Requirements.” 42 CFR Part 493, (2021) https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-42/chapter-IV/subchapter-G/part-493.

- 13.United States Department of Health and Human Services. “HIPAA Administrative Simplification.” 45 CFR Parts 160, 162, and 164, HHS, https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ocr/privacy/hipaa/administrative/combined/hipaa-simplification-201303.pdf.

- 14.Newitz A. Electronic Frontier Foundation; 2005. Dangerous Terms: A User's Guide to EULAs.https://www.eff.org/wp/dangerous-terms-users-guide-eulas [Google Scholar]

- 15.“Buy the Best B2B Lead Generation Software.” (2022) Leadfeeder, https://www.leadfeeder.com/lead-generation-software/.

- 16.Nanigans, (2022) https://www.nanigans.com.

- 17.“Sprinklr Acquires Nanigans' Social Advertising Business” Sprinklr. 2019. https://www.sprinklr.com/newsroom/sprinklr-acquires-nanigans-social-advertising-business/

- 18.“What is Unified-CXM?” (2022) Sprinklr, https://www.sprinklr.com/unified-cxm/.

- 19.M. For Developers. “Fbp and Fbc Parameters - Conversions API.” Facebook for Developers, (2022) https://developers.facebook.com/docs/marketing-api/conversions-api/parameters/fbp-and-fbc.

- 20.Shieber J. Ciitizen raises $17 million to give cancer patients better control over their health records. TechCrunch. 2019 https://techcrunch.com/2019/01/16/ciitizen-raises-17-million-to-give-cancer-patients-better-control-over-their-health-records/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.“Invitae to Acquire Ciitizen to Strengthen its Patient-Consented Health Data Platform to Improve Personal Outcomes and Global Research.” PR Newswire, 2021, https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/invitae-to-acquire-ciitizen-to-strengthen-its-patient-consented-health-data-platform-to-improve-personal-outcomes-and-global-research-301369974.html.

- 22.M. For Business, and Graham M. “Removing Certain Ad Targeting Options and Expanding Our Ad Controls.” (2022) Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/business/news/removing-certain-ad-targeting-options-and-expanding-our-ad-controls?_rdc=2&_rdr.

- 23.Trade Commission F. Press Releases; 2021. FTC Finalizes Order with Flo Health, a Fertility-Tracking App that Shared Sensitive Health Data with Facebook, Google, and Others.https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2021/06/ftc-finalizes-order-flo-health-fertility-tracking-app-shared [Google Scholar]

- 24.Restrepo N.J., Illari L., Leahy R., Sear R.F., Lupu Y., Johnson N.F. How social media machinery pulled mainstream parenting communities closer to extremes and their misinformation during covid-19. IEEE Access. 2022;10:2330–2344. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3138982. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.E. Frontier Foundation. “What Is Privacy Badger.” Privacy Badger, https://privacybadger.org/#What-is-Privacy-Badger. [Accessed 22 December 2021].

- 26.Mattu S. 2020. “Blacklight – the Markup.” the Markup.https://themarkup.org/blacklight [Google Scholar]

- 27.“The CERT Division | Software Engineering Institute.” (2021) Software Engineering Institute, Carnegie Mellon University, https://www.sei.cmu.edu/about/divisions/cert/index.cfm.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

We co-created this analysis with patient advocates who are listed in our acknowledgement section. Public patient advocates in the hereditary cancer community (n = 20) were invited to participate in co-production of this research at a response rate of 50% (N = 10). These patient advocates include a small sampling of the broader population. Specifically, public metadata for hereditary cancer communities on Facebook consist of about 73 groups ranging in size from 36 to 13,000 people.1 Out of this population, 3 of the 10 participants were active administrators of at least one Facebook support group for breast cancer. All participants were a member of at least one breast cancer support group over a time period between 2008 and 2021.

Facebook has a tool in user settings that allows users to see companies tracking browsing data in Off-Facebook Activity, which can also be downloaded into an archive of JSON files.2 The patient advocates who co-produced our data (N = 10) were asked to download their full Facebook archives as JSON files. Participants could also look at the data via Facebook’s user interface using Off-Facebook Activity in their user settings and provide screenshots. Each participant checked if they found digital medicine apps in their Off-Facebook Activity JSON files and then verified whether these users of PHR vendors or HIPAA-covered Entities had authorized access to their data. In order to determine whether an individual authorized access, we first analyzed each digital medicine company’s cross-site-tracking tools.2 We then compared the tools each company used with their privacy policies and applied the FTC’s September 2021 guidance on the Health Breach Notification Rule.3 As a final step, we checked Facebook’s Ad Library to identify types of ads being run by each company. We also examined how each ad’s URL passed data from Facebook to third parties. From the 5 companies we identified in JSON files, we identified 27 third-party CDNs.