Abstract

The importance of cultivating self-compassion is an often neglected issue among mental health professionals despite the risks to occupational well-being present in psychological care, such as burnout or compassion fatigue. In this context, this literature review has a twofold aim. Firstly, to contribute to raising awareness of the benefits of self-compassion among professionals, based on empirical research findings. Secondly, to coherently organize the available evidence on this topic, which to date appears scattered in a variety of articles. A systematic search on the APA PsycInfo database was conducted, and 24 empirical studies focused on the topic of the benefits of self-compassion in mental health professionals were finally selected. Concerning their methods, only 4 of the selected studies used experimental or quasi-experimental designs, 14 were cross-sectional studies, 3 presented qualitative research, and 3 were literature reviews. The research, regardless of methods used, points mainly to the benefits of self-compassion on the therapists’ mental health and well-being; prevention of occupational stress, burnout, compassion fatigue, and secondary traumatization as well as improvement of therapeutic competencies and professional efficacy-related aspects. In the review, self-compassion appeared as a process that could explain the benefits (eg on burnout) of cultivating other skills (eg mindfulness). To further explore this point, an additional review included 17 studies focused on the effects of mindfulness or compassion-based interventions on therapists’ self-compassion. In conclusion, our work joins those who have recommended the inclusion of self-compassion trainings in the curricula of mental health professionals.

Keywords: self-compassion, mental health professionals, burnout, well-being, therapeutic skills

Introduction

Self-compassion is a topic that is attracting great interest in current psychology. Following Neff’s1 definition, self-compassion entails self-kindness, mindfulness, and feelings of common humanity. Self-kindness refers to an attitude of benevolence towards oneself, rather than self-criticism and self-judgment. Mindfulness involves being aware of one’s inner experiences from an open, accepting and non-judgmental perspective rather than being fused or over-identified with thoughts and emotions. Finally, the common humanity component is referred to the understanding of suffering and pain as universal aspects of the human shared experience, instead of feeling isolated, separate, strange, weird or marginalized when disturbing events occur or problematic emotions arise.

Self-compassion has been shown to be consistently associated with benefits for mental health and well-being across diverse populations.2,3 Specific interventions aimed to cultivate self-compassion skills, such as the Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC) program4,5 have even been designed. In addition, this particular training protocol, or adaptations of it, have been demonstrated as effective in several studies carried out in community samples6–8 and clinical settings.9

However, the use of interventions and trainings aimed at cultivating mental health professionals’ self-compassion is not a widespread practice yet. This is rather unexpected for several reasons. First, as mentioned, self-compassion is connected with positive outcomes in the general population, and it would be similarly expected that mental health professionals would benefit from cultivating self-compassion. Second, experienced working health professionals as well as future therapists still in training and those who are in the initial stages of their professional career, are very vulnerable to psychosocial risks derived from the emotional demands implicit in their work.10,11 This makes them prone to burnout, compassion fatigue, and other forms of occupational stress, which are risks that self-compassion skills could contribute to prevent. Third, other interventions focused on training skills, such as mindfulness and compassion for others, have already shown that they produce benefits in mental health professionals (e.g.,12–14). However, compassion towards oneself, or even a more general emphasis on self-care, seems to be often forgotten among therapists. Furthermore, as will be presented later, therapists themselves sometimes experience psychological barriers (eg, fear of stigma, irrational ideas opposed to self-care, etc.) that block the possibility of seeking help or engaging in self-compassionate practices.15

Fourth, an emerging issue in the professional community is the need to “practice what is preached”.16 Here, Bennett-Levy and Finlay-Jones17 have emphasized that therapists in training should experience by themselves the techniques that they will later apply to their future patients or clients. This model of personal practice has at least two benefits: on a personal level, it promotes the growth of the future therapist while at a professional level it contributes to a better knowledge of the intervention strategies that are going to be used, and ultimately, it favors the development of therapeutic skills.

Why then is the topic of the need for self-compassion not more widespread as a self-care tool among therapists? A possibility is that self-compassion may be viewed as an emerging construct and self-compassion interventions are beginning just now to receive evidence-based support. However, as mentioned above, there is already a growing body of research supporting both the benefits of self-compassion and the possibility to effectively train this skill. Rather, we believe that the problem is a matter of sensitivity: mental health professionals may be not aware enough of the importance of preventing burnout and the need to protect their working life quality. The benefits of self-care, and particularly self-compassion, may have not received much attention and be unknown to many therapists. In addition, the information on these topics is sometimes scattered across a variety of sources, each looking at a particular benefit or aspect of self-compassion. It is therefore necessary to make an effort of clarification and integration of the available knowledge.

In this context, the present work aimed to carry out a systematic bibliographic review, with a twofold purpose. First, to contribute to making the benefits of a self-compassionate attitude visible among mental health professionals, based on the results obtained in empirical research. Second, to offer an integrated perspective on these benefits, identifying a series of aspects (for example, prevention of burnout, improvement of the professional’s mental health and well-being, benefits for the therapeutic relationship and for the professional’s effectiveness, etc.) where the cultivation of self-compassion has been shown to have beneficial effects or, at least, associations with positive outcomes.

Materials and Methods

A bibliography search was carried out in the abstracting and indexing database APA PsycInfo. This database contains more than five million interdisciplinary bibliographic records and it represents a major source for psychological, behavioral and social sciences research. The search was designed with the purpose of our review in mind, ie to ascertain the state of the art in research on the benefits of self-compassion in psychologists and other mental health professionals. An advanced search was carried out using the search term self-compassion OR loving-kindness to delimit the constructs of interest in the review. To delimit the professional group that represents the focus of the review, the string of terms psychologist OR counselor OR therapist OR psychiatrist OR psychiatrist OR mental health professional OR psychotherapist was used. The terms referring to constructs and professional groups were also associated with the Boolean operator AND. The complete search string had the following structure: (self-compassion OR loving-kindness) AND (psychologist OR counselor OR therapist OR psychiatrist OR mental health professional OR psychotherapist). This string was used to search in the title (TI), abstract (AB), subject (SU) and exact subject (DE) of the documents indexed in the document database. In addition, the option “apply equivalent subjects” was used as a search amplifier. As search limitations, only scientific articles published in peer-reviewed journals and in the English language be retrieved. Access to the APA PsycInfo database was carried out through the website of the library of the Pontifical University of Salamanca in May 2022.

The search using these parameters yielded a total of 116 documents. Two researchers then independently carried out a first analysis to assess their relevance for the purposes of this paper based on reading the abstracts of the retrieved articles. There were only three cases of disagreement about the relevance of the records, and the researchers reached consensus after reading the full text of each document. A total of 67 papers were discarded where the focus was on self-compassion in patients, clients or the general population and not on the mental health professional community. There were 49 pre-selected documents. A second, independent filtering, based on a detailed reading of pre-selected papers’ full texts, was then carried out in order to discard papers that dealt with self-compassion only secondarily. Thus, 27 articles were discarded using the following exclusion criteria: a) the paper’s main focus was not self-compassion but another related variable (eg loving-kindness, other-focused compassion); b) a non-self-compassion based intervention was administered to psychotherapists and effects on self-compassion (considered as dependent variable) were analyzed; and c) the paper did not report empirical research (eg theoretical proposals, personal experience report, opinion article). There was no disagreement between the researchers about discarded papers in this second filtering of documents. Thus, 22 studies were finally selected from the initial PsycInfo database search. These studies were classified according to their methods, with 4 studies reporting experimental or quasi-experimental research involving the administration of a self-compassion intervention for psychotherapists or psychotherapists in training, 12 cross-sectional studies on self-compassion, conducted using samples of mental health professionals, 3 qualitative studies, and 3 literature reviews.

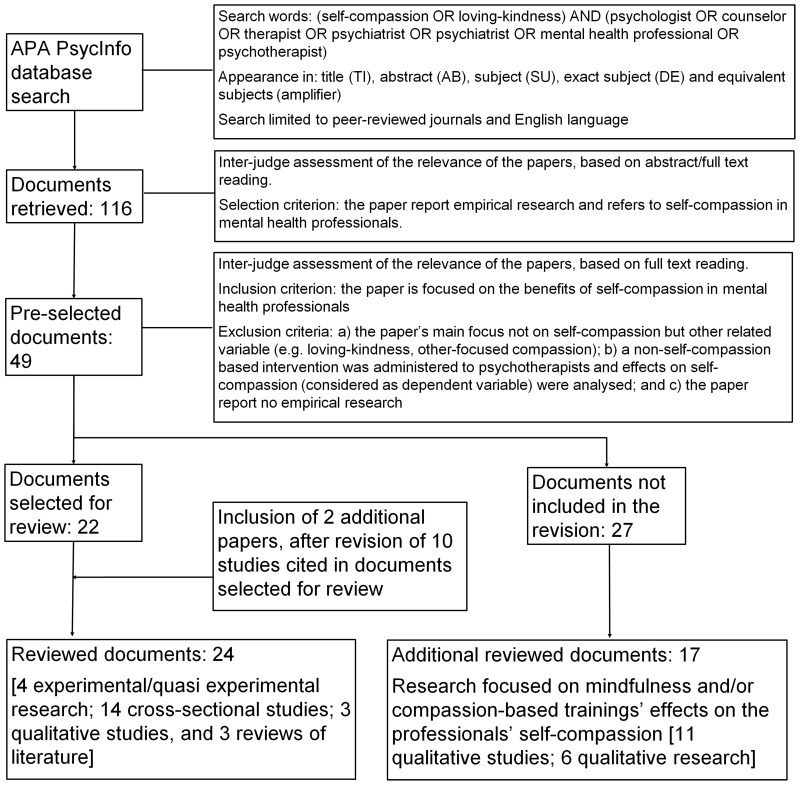

In addition to the documents retrieved from the PsycInfo database, 10 articles cited in papers already selected for review were also considered as candidates to be included in the literature review. A priori, these articles seemed relevant because they mentioned possible associations between self-compassion and other variables in mental health professionals. An inter-judge assessment of the relevance of these 10 new documents was carried out, based on an independent reading of full-texts. Finally, only 2 papers, reporting cross-sectional research, were selected for inclusion in the review, and 8 papers were discarded using the previously mentioned exclusion criteria. Therefore, the final sample of papers to be reviewed comprised a total of 24 empirical studies. However, we have also considered 17 out of the 27 articles that were not selected for review, in order to conduct an additional review on the effects of mindfulness and/or compassion-based interventions on therapists’ self-compassion. These studies do not address the main focus of our review (ie benefits of self-compassion), but they provide insights into how self-compassion can be increased among professionals. Although this is a topic that would merit a review in itself, we found it interesting to include these articles in our research for several reasons. First, they are studies that help contextualize the topic of self-compassion in therapists by connecting it to research on the antecedents of self-compassion. Second, these studies could provide a starting point for the identification of interesting relationships, such as the possible mediating role of self-compassion with respect to the effects of mindfulness or compassion-based training. Third, the knowledge derived from these studies may have practical and applied importance, as they identify ways to increase self-compassion in therapists. If, as hypothetically expected, the practice of self-compassion is potentially beneficial for mental health professionals, it may be equally interesting to have at least an initial idea of how therapists can become more self-compassionate. Figure 1 presents the systematic process followed for reviewing empirical research.

Figure 1.

Systematic process followed for reviewing empirical research.

Results

Review Studies

The review studies show that the topic of the benefits of self-compassion in therapists has so far received little attention. Only three previous systematic reviews have been located, the studies by Boellinghaus et al.18 Bibeau et al19 and Rudaz et al20 in which the possible effects of self-compassion in mental health professionals are mentioned.

The review by Boellinghaus et al18 attempts to analyze the role of Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) and Loving-Kindness Meditation (LKM) in the cultivation of self-compassion and other-focused concern in health professionals. It focuses primarily on the effects of MBIs, since, as the authors say, at the time the review was conducted, there were no studies that included LKM or related practices in healthcare workers. However, they comment that the positive results obtained in non-clinical (non-healthcare) samples where the role of LKM is analyzed could be generalizable to healthcare personnel samples.

A similar conclusion is reached in the review by Bibeau et al,19 who state that there are few studies on loving-kindness and self-compassion that focus on healthcare professionals and even fewer that focus on psychotherapists, so they take as a reference the research on the benefits of these practices in the general population. These authors call for further research on the protective effect of self-compassion and compassion meditation practices and their effects on empathy and burnout. Interestingly, they hypothesize that self-compassion meditation would reduce burnout linked to empathetic distress through better self-regulation of psychotherapists’ emotions while they are exposed to their patients’ suffering.

Rudaz et al20 reviewed the effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC), and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) to foster self-care and reduce stress in mental health professionals. They found only 2 studies, one by Finlay-Jones et al16 and the other by Smeets et al21 out of a total of 24 studies. The study by Smeets et al21 uses a sample of first or second year psychology undergraduates, so it would not fit the aim of the present review. In any case, Smeets et al21 found that the self-compassion intervention produced benefits in self-compassion, mindfulness, optimism, self-efficacy, life satisfaction and connectedness, and decreases in rumination. The study by Finlay-Jones et al16 will be also mentioned in the next section (experimental and quasi-experimental research) of the present review. Among the benefits of self-compassion, Finlay-Jones et al16 found that psychology trainees who participated in an online self-compassion cultivation program experienced gains in self-compassion and eudaimonic happiness, as well as reductions in stress emotion regulation difficulties. Interestingly, Rudaz et al20 noted that there is potential for further investigation of the relatively young MSC program. Furthermore, they warn of the need for well-powered research, which includes randomization, active control groups, and long term follow-up that focuses on the study of mechanisms of change that are implicated in the benefits of the interventions.

Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Research on the Effects of Self-Compassion Training

The search yielded four publications in which self-compassion interventions were delivered to psychologists or graduate students and the trainings’ effects on a series of variables were analyzed.

Finlay‐Jones et al16 performed pre-post comparisons and also included a 3-month follow-up. Yela et al3 conducted a pre-post study using two groups with different adherence to MSC treatment. Eriksson et al22 used a randomized control design. Finally, Jiménez-Gómez et al23 used a randomized control design with CG active, and waitlist CG.

Two of these studies employed Internet-based programs. The “Self-compassion Online” program lasted for 6 weeks, with participants taking 1 to 2 hour per week to complete the online program and homework.16 The “Internet Program Mindfulness and Compassion with Self and Others”, encompassed about 15 min of training per day, 6 days a week, for 6 weeks.22 The other two studies employed the 8-week MSC protocol, with face-to-face sessions, 2.5 hours per week.3,23 The samples used in these intervention studies consisted of psychology graduate students,16 psychologists attending graduate courses in clinical and health psychology,3,23 and practicing psychologists.22

Significant improvements in self-compassion were obtained in all four studies (all using the 26-item SCS scale, except Eriksson et al,22 that used the 12-item SCS). Two studies found pre-post improvements,3,16 and two studies reported improvements in relation to the waitlist CG.22,23 However, in the latter study the MBSR active CG did not significantly improve their self-compassion scores relative to the waitlist CG. More specifically, in the study by Eriksson et al,22 a significant decrease in the SCS self-coldness factor scores was also observed in relation to the CG waitlist.

Concerning mindfulness, three trainings where this variable was assessed using the FFMQ scale reported statistically significant improvements on the participants’ levels. Eriksson et al22 found significant improvements in the mindfulness total score in relation to the waitlist CG. Similarly, Yela et al3 reported that graduate students with high adherence to MSC training improved their total mindfulness scores. Finally, Jiménez-Gómez et al23 report that the MSC training produced significant improvements in mindfulness scores from pre- to post-training, compared with the CG waitlist.

Two papers studied the effect of self-compassion training on depression, showing a similar trend of improvement. Finlay-Jones et al16 found a significant decrease in depression symptoms (using DASS-21) between pre- and post-training, with gains maintained at 3-month follow-up. Jiménez-Gómez et al23 also found significant pre-to post- decreases in depression symptoms (using BDI), although such reductions did not significantly differ from the changes observed in the waitlist CG.

Two studies evaluated the effects of the self-compassion trainings on anxiety, reporting, however, less intense changes, probably due to a floor effect in the participants’ scores. Finlay-Jones et al16 did not find significant pre- to post-intervention decreases (using DASS-21), although significant reductions in anxiety were observed from pre-test to 3-month follow-up. Jiménez-Gómez et al23 found that the group that received MSC did not decrease their levels of anxiety (using STAI-S) from pre- to post-training. However, the waitlist CG experienced a significant increase in anxiety scores. Here, the MSC program could have had a protective effect against possible increases in anxiety during stressful periods.

The effects of training on psychologists’ perceived stress (assessed with PSS) were studied in two papers using online protocols, and beneficial effects were observed. For example, Finlay-Jones et al16 found significant improvements in perceived stress symptoms from pre- to post-test, which were maintained at 3-month follow-up. Eriksson et al22 also reported a significant decrease in perceived stress after the self-compassion training, in comparison with the CG waiting list. Regression analyses indicated that the SCS change-scores predicted 41.5% of the variance, and the FFMQ change-scores explained 16.1% of the additional variance.

Other benefits derived from self-compassion online interventions are the increase in emotional regulation capacity (using DERS) from pre- to post-intervention, gains that were maintained at 3-month follow-up.16 Moreover, Eriksson et al22 observed a significant improvement in burnout scores (using SMBQ) in relation to the waitlist CG. Remarkably, only this study assessed burnout using an experimental design. The changes in SCS accounted for 29% of the variance in burnout, whereas the FFMQ scores did not add any significant variance.

Only two studies evaluated the effects of self-compassion training on the therapists’ well-being. First, Finlay-Jones et al16 found a significant pre-to post-intervention increase in happiness (measured by AHI) scores that were maintained at 3-month follow-up. Second, Yela et al,3 using the PBWS, also observed significant pre-to post- changes in the global psychological well-being score in a group of psychologists with high adherence to MSC training.

It is also interesting to consider the “usability” and feedback from psychologists who received training, as reported in 2 papers. Finlay-Jones et al16 informed that average ratings across the SCO program’s modules were high for enjoyableness, relevance, comprehension, and learning, with low to moderate perceived difficulty. Participants also described positive effects on their therapeutic work, including increased authenticity, responsiveness, and a greater capacity to “be present” and “practice what you preach”. Participants also reported increased resilience in the face of stress and expressed appreciation for the value of self-care practices. The main difficulty reported was the lack of time to complete the program as several participants suggested reducing the amount of content. The MSC group participants, in the study by Jiménez-Gómez et al,23 reported an overall level of involvement and practice of 68.2%, high satisfaction with the program (7.7/10), and an average of 3 days per week dedicated to formal practices and 2.7 times a day doing informal practices. No differences between psychologists who received MSC and MBSR trainings were found concerning levels of satisfaction, involvement with their respective programs, and engagement with formal/informal practices.

The difference between self-compassion programs using face-to-face vs online format also deserve a comment. In general terms, the 4 studies reviewed reported significant improvements in self-compassion, mindfulness, anxiety and depression. However, if we consider the effect sizes, the increase in self-compassion was larger (Cohen’s d > 0.8) in the online programs in relation to the face-to-face training, in which intermediate effect sizes were observed (Cohen’s d > 0.50 and < 0.80). The effect sizes of mindfulness, anxiety and depression did not differ in face-to-face vs online formats. Overall, intervention studies found moderate effect-size increases for mindfulness, while improvements in anxiety and depression were mostly of small magnitude (Cohen’s d < 0.50). Concerning other effect-sizes reported in intervention studies, improvements in psychological well-being3 and stress16 presented large effect sizes, and improvements in happiness, difficulty of emotional regulation and perceived stress had moderate effect sizes.16,22

Several meta-analyses24–26 had previously indicated that self-compassion programs delivered to the general population produced overall significant moderate effect-size increases in self-compassion, mindfulness and depression, and improvements of close to moderate magnitude in anxiety. It should be noted that self-compassion programs produce changes with intermediate effect sizes on self-compassion when face-to-face sessions are used with psychologists and in the general population, while the effect size is large when working with psychologists in an online format. Effect-sizes of mindfulness are moderate in both the general population and psychologist samples. Effect-sizes of anxiety tend to be rather small in both psychologists and general population samples. Finally, changes in depression tend to be moderate in the general population but small in psychologists’ samples (probably due to a floor effect). Table 1 summarizes the experimental and quasi-experimental research reviewed.

Table 1.

Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Research on the Benefits of Self-Compassion

| Study | Sample | Program Type | Comparison of Groups (YES/NO)RCT/no RCT | Groups Design | Time of Measure | Dependent Variables | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eriksson et al (2018).22 | Practicing psychologists | Internet Program. Mindfulness and compassion with self and others (Schenström, 2017). |

Yes/ RCT |

-EG N=40 -CG waiting list=41 |

Pre/post/no follow-up | SCS FFMQ PSS SMBQ |

● Increase in total SCS and total FFMQ. Larger effect size in SCS than in FFMQ. ● Reduced levels of self-coldness (SCS subscale), perceived stress and burnout symptoms. ● Correlational results: measures of stress and burnout are more associated with the self-coldness dimension than with the positive dimension of self-compassion. |

| Finlay-Jones et al (2017).16 | Psychology trainees | Self-Compassion Online (SCO) program 6-week self-guided online self-compassion cultivation program. |

No/ No RCT | -EG N=37 | Pre/post/follow-up 12 weeks | SCS PSS AHI DERS DASS-21 Program feedback |

● Significant improvements in self-compassion, happiness, perceived stress, emotion regulation difficulties, and psychophysiological symptoms of depression and stress between pre- and posttest. Additionally, these changes were maintained at 3-month follow-up. ● Significant decreases in anxiety between pretest and follow-up. ● Average ratings across modules were high for enjoyableness, relevance, comprehension, and learning, and low to moderate on difficulty. ● Positive effects on the therapeutic work of the participants: increased authenticity, responsiveness and a greater ability to “be present” and “practice what is preached” ● Increased resilience in the face of stress and expressed appreciation for the value of self-care practices. |

| Jiménez-Gómez et al (2022).23 | Clinical and Health Psychologist trainees. | MSC original. | Yes/partial RCT | -EG N=34 -CG active MBSR N=26 -CG waitlist= 28 |

Pre/post/no follow-up | SCS FFMQ STAI-S BDI Satisfaction with training and participation |

● MSC training improves pre-post scores in mindfulness and self-compassion and also in relation to CG waitlist. Anxiety scores are maintained in relation to CG waitlist. Significant decrease in pre-post depression, but not different from that observed in the CG waiting list. ● MBSR decreases mindfulness, anxiety and depression relative to CG waitlist. ● Both MSC and MBSR produce significant decreases in self-compassion, mindfulness and anxiety. MBSR also significantly reduces depression relative to MSC. ● No differences between MBSR and MSC in overall level of involvement and practice, satisfaction with the program, and time spent in formal and informal practice. |

| Yela et al (2020).3 | Clinical and Health Psychologist trainees. | MSC original. | Yes/No RCT | -EG Self-reported high adherence to training N=30 -CG Self-reported low adherence to training N=31 |

Pre/post/no follow-up | SCS FFMQ STAI-S BDI PWBS |

● EG significantly improves self-compassion, mindfulness and psychological well-being in relation to CG. ● Positive correlation between degree of adherence/practice and improvement in self-compassion, mindfulness and psychological well-being. ● Higher increases in self-compassion from pre- to post-intervention were significantly connected to increased mindfulness and psychological well-being and to reduced depression symptoms over time. ● No effect on Anxiety and Depression (floor effect; low range of scores). |

Abbreviations: RCT, Randomized Controlled Trial; EG, Experimental Group; CG, Control Group; MSC, Mindful Self-Compassion program; MBSR, Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program; AHI, Authentic Happiness Inventory; Peterson & Park, 2008; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; Beck et al, 1961; DASS-21, Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995; DERS, Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; Gratz & Roemer, 2004; FFMQ, Five Facets of Mindfulness Questionnaire, Baer et al, 2006; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; Cohen et al, 1983; PWBS, Psychological Well-Being Scales; Ryff, 1989; SCS, Self-Compassion Scale; Neff (2003); SMBQ, Shirom Melamed Burnout Questionnaire; Melamed et al, 1999; STAI-S, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; Spielberger et al, 1982.

Cross-Sectional Research

The cross-sectional studies reviewed have analyzed self-compassion associations with a wide range of variables, in most cases suggesting that higher self-compassion is connected with beneficial psychological aspects. Obviously, as these are cross-sectional studies, it cannot be claimed that self-compassion causes these positive effects. However, this research serves to show that high levels of self-compassion may be linked in some way to numerous positive outcomes for mental health professionals.

In this regard, numerous studies have found a negative relationship between self-compassion and burnout scores, or burnout-related constructs such as compassion fatigue, in mental health professionals or trainees.27–32 McCade et al29 and Richardson et al31 have used the 19-item Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI)33 scale, finding negative associations with self-compassion. Kotera et al28 used a version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory,34 with just two items to measure emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. Both components of burnout were found to be negatively related to levels of self-compassion. Some studies have used the Professional Quality of Life Scale (PROQOL) by Stamm,35 which allows obtaining scores of compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue, which in turn would include the components of burnout and secondary traumatic stress. Using this scale, Ondrejková and Halamová30 found that compassion fatigue was negatively associated with total self-compassion scores and scores on two dimensions of self-compassion (ie, tolerating uncomfortable feelings and motivation to act), obtained using the Sussex-Oxford Compassion for the Self Scale (SOCS-S).36 However, self-compassion was no longer a significant predictor of compassion fatigue when variables, such as self-criticism and compassion satisfaction, were included in the same regression model.30 The studies by Beaumont et al27 and Yip et al32 also report negative associations of self-compassion with burnout and secondary traumatic stress. In these two studies, Neff’s1 26-item SCS scale is used as a measure of self-compassion. From this scale Beaumont et al27 and Yip et al32 calculate scores for positive (self-warmth/self-kindness) and negative (self-coldness/self-judgment) components of self-compassion, which would be negatively and positively associated, respectively, with both burnout and secondary traumatic stress. Regarding compassion satisfaction, Beaumont et al27 found no significant associations of this variable with self-compassion (total score), self-kindness or self-judgment. The study by Ondrejková and Halamová30 does not provide information on this possible association, while Yip et al32 did not use the compassion satisfaction subscale of the PROQOL.

Self-compassion has also been found to be a mediating variable in relation to professional characteristics associated with compassion fatigue or burnout. Thus, Ondrejková and Halamová30 found that doctors, pedagogues, home nurses, nurses and psychologists reported higher levels of compassion fatigue, while psychotherapists and coaches reported the lowest levels. The relationship between different professions and compassion fatigue could be explained by the levels of self-criticism and self-compassion reported by different professionals. Also interesting is the result found by Kotera et al28 regarding the relationship between work-life balance and emotional exhaustion -one of the dimensions of burnout-, which would be partially mediated by psychotherapists’ levels of self-compassion.

Self-compassion has also been analyzed in connection with another group of variables related to well-being and psychological symptoms that professionals may experience. Here, it has been found that higher levels of self-compassion are associated with better scores in well-being,27,37 while self-kindness and self-judgment are positively and negatively associated, respectively, with this construct.27 Higher scores on self-compassion would further correspond with lower levels of depression,29,31 psychological distress38 and stress.39 Moreover, self-compassion could play a protective role against the onset of depressive symptoms in times of increased burnout risk. As McCade et al29 reported, self-compassion acts as a moderating variable in the positive relationship between burnout and depression, finding that for psychologists with high levels of self-compassion, the connection between burnout and depression is not significant, while for those with low or moderate levels of self-compassion, a positive and significant association between burnout and depression is observed. Interestingly, Aruta et al40 have informed of positive correlations between self-compassion and professionals’ attitudes and intentions towards help-seeking in case of experiencing mental health problems themselves, which may indicate that these self-compassionate professionals could better circumvent one of the barriers to help-seeking, ie the stigma attached to mental health among healthcare providers.28 Especially, the connection between self-compassion and mental help-seeking attitudes seems to intensify with age, being stronger for older professionals -counselors in this case-.40

Particularly interesting are the associations found in numerous studies between self-compassion and other variables that are in turn related to mental health. One of these variables is the practitioner’s mindfulness capacity, which is associated with levels of secondary traumatic stress32 and psychological distress.38 The studies reviewed consistently find a positive correlation between self-compassion and mindfulness.38,41–43 As expected, higher levels of mindfulness have been reported to be positively related to self-warmth and negatively related to self-coldness.32 Moreover, the effects of mindfulness on secondary traumatic stress could be explained by considering the variables self-warmth and self-coldness in simple mediation models.32 Self-critical perfectionism is another variable that has been positively associated with variables such as depression and burnout, while it would be negatively related to self-compassion.31 In fact, the simple mediation models tested by Richardson et al31 reveal that self-compassion would act as a partial mediator in the relationship between self-critical perfectionism and depression, and self-critical perfectionism and burnout.

Self-compassion is also associated with variables that reflect how professionals deal with potentially challenging situations. In this regard, Fulton42 has found a positive correlation between self-compassion and greater tolerance for ambiguity, as well as a negative correlation between self-compassion and levels of experiential avoidance. Similarly, Finlay-Jones et al39 found that professional and trainee psychologists who reported higher levels of self-compassion also reported lower difficulties in emotional regulation, a construct that includes non-acceptance of emotions, difficulties engaging in goal directed behavior when upset, impulse control difficulties when upset, limited access to emotion regulation strategies, and lack of emotional clarity. Moreover, Finlay-Jones et al39 found that difficulties in emotion regulation experienced by psychologists mediated the relationship between self-compassion and stress. This relationship is also interesting because it may offer a possible explanation for the mechanism through which self-compassion becomes associated with potential benefits, ie through an enhancement of emotion regulation processes.

Another group of variables analyzed in cross-sectional studies have to do with aspects that are involved in the therapeutic relationship. For example, using a sample of counseling and clinical psychology doctoral trainees, Latorre et al41 found a positive association between self-compassion and self-evaluations of counselor self-efficacy and professional competency, which was maintained even controlling for other covariates such as age, gender, number of years in the doctoral program and mindfulness. In fact, this study found that self-compassion acted as a mediating variable in the relationship between mindfulness and counselor self-efficacy and self-assessed professional competency. Self-compassion is also associated with higher levels of therapeutic presence,38 ie the capacity to bring one’s whole self into encounters with patients and being fully aware on multiple levels (physical, emotional, cognitive, spiritual). And again, self-compassion is found to be a variable involved in the relationship between the other two. In this regard, Bourgault & Dionne38 found that levels of self-compassion and psychological distress acted as parallel mediators in the relationship between mindfulness and therapeutic presence.

A separate question is whether higher levels of self-compassion on the part of the mental health professional also translate into self-perceived benefits for the patient. The results on this issue are more controversial. Fulton42 found that more self-compassionate counselor trainees had a perception that sessions with clients had greater depth, but practitioner levels of self-compassion did not correlate with client-rated perception of session depth or client-perceived empathy. In a similar vein, when analyzing the possible relationship between self-compassion and compassion for others in mental health professionals, the results are not entirely conclusive. For example, Beaumont et al27 do not find a significant association between self-compassion and compassion for others. However, Fulton,43 Roxas et al37 and Yip et al32 report positive correlations between self-compassion and compassion for others. Fulton43 further finds that levels of compassion for self mediate the relationship between mindfulness and compassion for others. Yip et al32 elaborate further and report that the dimension of self-warmth, but not self-coldness, mediates the relationship between mindfulness and compassion for clients.

As presented, cross-sectional studies suggest that higher levels of self-compassion are generally associated with values indicative of better occupational health and mental health among professionals. However, the study by Tigranyan et al44 found results contrary to expectations, with higher levels of self-compassion associated with greater experience of the imposter phenomenon, more perfectionism cognitions, higher anxiety, and lower achievement motives in clinical and counseling psychology doctoral students. Despite these results, the authors point to an interesting idea: self-compassion implies being kinder to oneself, but precisely that presupposes a high awareness of one’s imperfections and does not necessarily imply that one experiences lower levels of guilt or anxiety.

Finally, it is important to note that all these cross-sectional studies share some limitations derived from the methodology employed. As many of them acknowledge, a first caveat is that due to their correlational nature, the associations found between self-compassion and other variables do not imply a causal relationship, even in cases where mediational relationships are analyzed. Other widely acknowledged limitations of these studies are the difficulties in generalizing the results due to limitations in the size and/or representativeness of the sample, the use of self-report measures susceptible to being affected by the subjectivity of the participants themselves, difficulties in controlling for potential confounders, and the possible loss of nuance implied by the use of quantitative scores to analyze the professionals’ subjective experiences. In this sense, authors of the cross-sectional studies reviewed frequently recommend using experimental and longitudinal designs to clarify the relationships between variables, analyzing more complex relationships between variables, and incorporating qualitative perspectives, among other possible lines of research development.

Despite their limitations and shortcomings, these cross-sectional results are valuable in several ways. Several authors advocate the incorporation of self-compassion-based training in the curriculum of mental health professionals, in order to foster a greater awareness of the need for self-care in this group.27,29–32,39–41,43 Furthermore, they point to the possible role of self-compassion as a protective element against occupational hazards characteristic of mental health care, such as compassion fatigue, or more general problems related to stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms. Table 2 summarizes cross-sectional research on the benefits of self-compassion for mental health professionals.

Table 2.

Cross-Sectional Research on the Benefits of Self-Compassion

| Study | Sample | N | Variables Analyzed | Associations Between SC and Other Variables | Complex Relationships Among Variables (Mediation and Moderation) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aruta et al (2022).40 | Counselors | 158 | SCS-SF; MHSIS; MHSAS | Mental help-seeking intention (+); mental help-seeking attitudes (+) | Self-compassion → Mental help-seeking attitudes → Mental help-seeking intention The relationship between Self-compassion and Mental help-seeking attitudes is moderated by age. |

| Beaumont et al (2016).27 | Students counsellors and student cognitive behavioral psychotherapists. | 54 | PROQOL; SCS; WEMWBS-SF; CS | Burnout (-); secondary traumatic stress (-); well-being (+) | |

| Bourgault & Dionne (2019).38 | Psychologists | 178 | SCS-SF; FFMQ; TPI-T; IDPESQ-14 | Mindfulness (+); therapeutic presence (+); psychological distress (-) | Mindfulness → Self-compassion and Psychological distress→ Therapeutic presence |

| Finlay-Jones et al (2015).39 | Professional and trainee psychologists | 198 | SCS-SF; DERS; DASS-21 (stress subscale); BFI-N | Emotion regulation difficulties (-); stress (-) | Self-compassion → Emotion regulation difficulties→ Stress |

| Fulton (2016).42 | Master’s counselling students | 48 students and 55 patients | FFMQ; SCS; SEQ; AAQ-II; MSTATS; BLRI-CF; | Mindfulness (+); Session depth (assessed by therapist) (+); experiential avoidance (-); tolerance to ambiguity (+) | |

| Fulton, (2018).43 | Master’s counselling interns | 152 | SOFI; FFMQ | Mindfulness (+); Compassion for others (+) | Mindfulness → Self-compassion → Compassion for others |

| Kotera et al (2021).28 | Psychotherapists | 126 | MBI (2-items); SCS-SF; WLBC; TS | Emotional exhaustion (-); depersonalisation (-); work-life balance (+) | Work-life balance → Self-compassion → Emotional exhaustion |

| Latorre et al (2021).41 | Counselling and clinical psychology doctoral trainees | 192 | SCS-SF; MAAS; CSES; PCS-R | Mindfulness (+); self-efficacy (+); professional competencies (+) | Mindfulness → Self-compassion → Self-efficacy Mindfulness → Self-compassion → Self-assessed professional competency |

| McCade et al (2021).29 | Psychologists | 248 | SCS-SF; CBI; DASS-21 (depression subscale) | Burnout (-); depression (-) | Self-compassion moderates the relationship between burnout and depression |

| Ondrejková & Halamová (2022).30 | Helping professions (nurses, doctors, paramedics, home nurses, teachers, psychologists, psychotherapists and coaches, social workers, priests and pastors, and police officers). | 607 | PROQOL; SOCS-S; SOCS-O; FSCRS | Compassion fatigue (-) | Profession → self-compassion and self-criticism → Compassion fatigue |

| Richardson et al (2020).31 | Students in clinical/counseling psychology doctoral programs | 119 | APS-R (Discrepancy subscale); SCS; IDAS-II; CBI (Personal burnout subscale); SCS; IDAS-II; CBI (Personal burnout subscale). | Burnout (-); depression (-); self-critical perfectionism (-) | Self-critical perfectionism → Self-compassion → Depression Self-critical perfectionism → Self-compassion → Burnout |

| Roxas et al (2019).37 | School counselors, counseling psychologists and counselors-in-training | 231 | CS; SCS; HFS; SWBSF-SF; SWBSF-SF | Compassion for others (+); well-being (+); forgiveness of others/self (+) | Compassion for others → Forgiveness of others → Subjective Well Being. Self-compassion → Forgiveness of others → Subjective Well Being. |

| Tigranyan et al (2021).44 | Clinical and counselling psychology doctoral students | 84 | SCS-SF; AMS-R; GAD-7; GSE; PHQ-9; PCI; RSES; CIPS | Perfectionistic cognitions (+); anxiety (+); achievement motives (-); experiences of impostor phenomenon (+) | |

| Yip et al (2017).32 | Clinical psychologists and trainees. | 77 | SCS-SF; IMF-SF; PROQOL; CS; SDRS-5 | Self-warmth: Mindfulness (+); compassion to clients (+); age (+); years of experience (+); self-coldness (-); burnout (-); secondary traumatic stress (-) Self-coldness: Burnout (+); secondary traumatic stress (+); mindfulness (-); compassion to clients (-); age (-); years of experience (-) |

Mindfulness → Self-coldness → Burnout Mindfulness → Self-coldness → Secondary Traumatic Stress Mindfulness → Self-warmth → Compassion to clients Mindfulness → Self-warmth → Secondary Traumatic Stress |

Notes: (+) and (-) represent positive and negative associations between variables, respectively; the arrow → represents associations between variables involved in mediation relationships.

Abbreviations: AAQ-II, Acceptance and Action Questionnaire - II (Bond et al, 2011); AMS-R, Achievement Motives Scale (Lang & Fries, 2006); APS-R, Discrepancy subscale of the Almost Perfect Scale-Revised (Slaney et al, 2001); FI, Neuroticism subscale of the Big Five Inventory (John et al, 1991); BLRI, Barrett-Lennard Relationship Inventory-Client Form (Barrett-Lennard, 1962); CBI, Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (Kristensen et al, 2005); CIPS, Clance Impostor Phenomenon Scale (Clance, 1986); CS, Compassion to Others Scale (Pommier, 2011); CSES, Counselor Self-Efficacy Scale (Melchert et al, 1996); DASS-21, Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995); DERS, Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (Gratz & Roemer, 2004); FFMQ, Five Facets Mindfulness Questionnaire (Baer et al, 2006); FMI-SF, Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (Walach et al, 2006); FSCRS, Forms of Self-Criticizing/Attacking and Self-Reassuring Scale (Gilbert et al, 2004); GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder (Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, and Löwe, 2006); GSE, General Self-Efficacy Scale (Schwarzer & Jerusalem, 1995); HFS, Heartland Forgiveness Scale (Thompson et al, 2005); IDAS-II, Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms-Second Version (Watson et al, 2012); IDPESQ-14, Psychological Distress Index - Santé Québec Survey (Préville et al, 1992); MAAS, Mindfulness Attention Awareness Scale (Brown & Ryan, 2003); MBI, Maslach Burnout Inventory 2 item-version (West et al, 2012); MHSAS, Mental Help-Seeking Attitudes Scale (Hammer et al, 2018); MHSIS, Mental Help-Seeking Intention Scale (Hammer & Spiker, 2018); MSTATS, Multiple Stimulus Types Ambiguity Tolerance Scale-II (McClain, 2009); PCI, Perfectionistic Cognitions Inventory (Flett et al, 1998); PCS-R, Professional Competency Scale-Revised (Taylor, 2015); PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire (Kroenke et al, 2001); PROQOL, Professional Quality of Life Scale, version 5 (Stamm, 2009, 2010); RSES, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Nho, 2000); SCS, Self-Compassion Scale (long version) (Neff, 2003); SCS-SF, Self-Compassion Scale - Short Form (Raes et al, 2011); SDRS-5, Socially Desirable Response Set (Hays et al, 1989); SEQ, Session Evaluation Questionnaire-Form 5 (Stiles & Snow, 1984); SOCS-O, Sussex-Oxford Compassion for Others scale (Gu et al, 2019); SOCS-S, Sussex-Oxford Compassion for the Self Scale (Gu et al, 2019); SOFI, Self-Other Four Immeasurables (Kraus & Sears, 2009); SWBSF-SF, Subjective Well-Being Scale for Filipinos- Short Form (Hernández, 2010); TPI-T, Therapeutic Presence Inventory - Psychotherapist version (Geller, 2002); TS, Telepressure Scale (Montemurro & Perrini, 2020); WEMWBS-SF, Short Warwick and Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (Tennant et al, 2009); WLBC, Work-Life Balance Checklist (Daniels & Carraher, 2000).

Qualitative Research on the Benefits of Self-Compassion for Therapists

The topic of the benefits of self-compassion in mental health professionals emerged in three qualitative research studies, although in all cases the participants were counselors.15,45,46

The participants in Barton’s study15 emphasized the demands and challenges involved in their work, especially with regard to the therapeutic relationship, and the possible risks arising from this, such as burnout. They also pointed out two interesting issues that aggravate the situation. First, therapists have the perception that their preparation and training to deal with such challenges is inadequate. In addition, therapists themselves experience barriers to self-care, for example, the idea that self-care may be selfish behavior. In this context, the need to prioritize self-care in the learning process of therapists and to have a greater awareness of the importance of self-compassion as an essential part of being a therapist is identified.

The studies by Patsiopoulos and Buchanan45 and Quaglia et al46 agree in pointing out some benefits of self-compassion concerning the therapists’ well-being and their effectiveness in the therapeutic relationship with clients. In this regard, self-compassion would be related to a greater ability to self-observe with acceptance and kindness the therapist’s own emotional states.46 This ability may offer protection against occupational stress, by identifying and coping with signs of burnout or complex therapeutic situations.45 Self-compassion would also favor a greater capacity for emotional self-regulation, decreased self-criticism and perfectionism, and acceptance of one’s own limitations and uncertainty.46 As a consequence, the cultivation of self-compassion would be associated with qualities such as “balance”, “clarity”, “groundedness”, “openness”, “wisdom”, “joy”, “creativity”, “freedom”, and with the perception of greater overall well-being, job satisfaction and burnout prevention.45

In terms of the therapeutic relationship, the counselor’s self-compassion would also have benefits for the client. As Quaglia et al46 point out, therapists’ self-compassion models self-compassion for clients. In addition, this study makes interesting contributions on how self-compassion influences compassion for others, on the maintenance of an appropriate balance between self-care and other-compassion, how elements such as the experience of shared humanity can establish a bridge between self-compassion and other-compassion. Patsiopoulos and Buchanan45 mention, along the same lines, broad benefits of therapists’ self-compassion in their effectiveness as professionals or in the therapeutic relationship. Basically, the therapists’ self-compassion is associated with behaviors (eg management of self-expectations, balance between counselor and client needs, proactive, preventative self-care, etc.) that derive benefits for the therapeutic relationship itself (eg greater ability to attune to their clients, a circular flow of compassion self/others, management of self- and other-directed judgment, etc.).

Finally, the qualitative research reviewed emphasizes once again the need for mental health professionals to receive training in self-compassion and self-care as elements of protection against the risks derived from professional practice. Positively, the benefits also extend to the therapist’s well-being and effectiveness as a professional. Table 3 provides a summary of the qualitative studies on the benefits of self-compassion for mental health professionals reviewed.

Table 3.

Qualitative Research on the Benefits of Self-Compassion for Mental Health Professionals

| Study | Sample | N | Method | Main Results on the Benefits of Therapists’ Self-Compassion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barton (2020).15 | Counselors | 5 | Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA; Smith et al, 2009). | (a) self-care and self-compassion are essential parts of being a therapist that may be prioritized during professionals’ training as a means to cope with demands and challenges that therapists face in their work; (b) existence of barriers to self-care: it is not unusual for those who care for others to struggle with self-care (eg feeling selfish). |

| Patsiopoulos & Buchanan (2011).45 | Counselors | 15 | Narrative analysis process described by Lieblich et al (1998). | (a) better management of occupational stress and challenges (eg recognizing and addressing signs of depletion, working through ethical dilemmas, and processing decisions and their consequences); (b) overall sense of well-being: physical, psychological and emotional health, greater existential and/or spiritual sense of connectedness; (c) positive impacts on therapists’ ability to work effectively with clients and therapeutic relationship |

| Quaglia et al (2021).46 | Counseling interns (Master’s level) | 20 | Thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). | (a) supporting self-attunement, ie ability to observe one’s internal experience, attending to their emotional experience and promoting a sense of personal kindness and self-acceptance; (b) lessening self-criticism and perfectionism: feelings of “not being enough”, greater acceptance to moments of uncertainty and perceived missteps or mistakes, greater acceptance to limitations as a therapist in training (tolerate not knowing the “perfect” therapeutic response, imposter syndrome); (c) fostering intrapersonal emotion regulation (when receiving difficult feedback from clients during session and when counselors experienced activation from client material; (d) modeling self-compassion for clients. |

Additional Review. Research on the Effects of Mindfulness and Compassion-Based Interventions on the Therapists’ Self-Compassion

As presented in the Methods section, we initially discarded studies focused on the effects of mindfulness and/or compassion-based trainings on the professionals’ self-compassion. These papers analyzed the effects of interventions such as MBSR, MBCT, CCT, LKM, and other approaches, and considered self-compassion as an outcome variable. The focus of our review is rather the contrary, ie the analysis of potential effects of self-compassion. However, as the benefits of increasing the therapists’ self-compassion have been consistently identified, an additional review of interventions that likely enhance self-compassion may provide relevant information. Below, quantitative and qualitative research on such interventions is presented.

Quantitative Research on the Effects of Mindfulness and Compassion-Based Interventions on Self-Compassion

In this section we review the results of 11 publications that used quantitative methodologies to analyze the effects of different types of training on the improvement of self-compassion in psychologists/therapists in training.

A first group of studies is framed in the early years when the initial developments of mindfulness protocols were emerging. Specifically, they evaluate the effectiveness of the MBSR program47 in samples of health professionals,48 therapists in training49 and a pilot study with mental healthcare professionals.50 In all studies, in addition to effects on other variables, the program was found to produce significant increases in therapists’ self-compassion (SCS global scores). Moreover, Shapiro et al49 found improvements in 4 of the 6 subscales of the SCS (ie, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation and over-identification). In these same early years of implementation of mindfulness programs, the pilot study by Rimes & Wingrove51 evaluated the effectiveness of MBCT training52 in a group of trainee clinical psychologists. They found a significant increase in self-compassion and mindfulness scores, although not a decrease in rumination. In a qualitative section of the study, the authors identified that an increase in the acceptance of thoughts and emotions was frequently experienced as a result of the training (70%).

More recently, the effects on self-compassion produced by other types of mindfulness-based interventions have been analyzed. For instance, a quasi-experimental research using a Mindfulness for Stress Program with primary care health professionals,53 a pilot study using an Intensive Mindfulness Training program with clinical psychology students54 and a single case study using a mindfulness-based mobile intervention with a counselor.55 Pizutti et al53 and Schanche et al54 reported, among other effects, significant improvements in the global levels of self-compassion assessed with the SCS, with the second study also finding improvements in 5 of the 6 SCS subscales (all self-compassion dimensions except common humanity). The single-case study found that the use of the Calm © app did not generate significant increases in self-compassion, although it did improve levels of burnout and mindfulness.55

A second group of papers, published in 2016–2017, focused on the effects of compassion-based interventions on psychologists and therapists’ self-compassion. Here, Beaumont et al13,56 found a statistically significant overall increase in self-compassion scores (positive self-compassion) and a statistically significant reduction in self-critical judgment scores (negative self-compassion) after training compassion skills, using Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT)56,57 and Compassionate Mind Training (CMT).13 Scarlet et al58 conducted a pilot study where the Compassion Cultivation Training (CCT)59 program was delivered to healthcare workers. Among other results, they found significant improvements in participants’ self-compassion were also found.58

Finally, the study by Stafford-Brown and Pakenham60 is also worth mentioning as it reported results from an ACT-informed intervention for stress management and improvement of therapist skills among clinical psychology trainees. This study showed significant differences in relation to a CG in work-related stress, distress, life satisfaction, counseling self-efficacy and therapeutic alliance, but not in self-compassion.

Qualitative Research on the Effects of Mindfulness and Compassion-Based Interventions on Self-Compassion

We found 6 publications that qualitatively analyzed the effect of various programs or strategies that produced beneficial effects on mental health professionals’ self-compassion. All these studies used small samples and relied on interpretative analysis strategies aimed at identifying emerging topics from the participants’ discourse. Interestingly, among other topics, increases in self-compassion are reported in these studies.

Two studies focused on Loving-Kindness Meditation (LKM) trainings. Boellinghaus et al61 worked with twelve therapists-in-training who had previously attended a mindfulness-based cognitive therapy course and participated in a 6-week LKM course. Using interpretative phenomenological analysis, five main themes emerged from the participants’ responses to an interview. In particular, the beneficial impact of the training on the self (self-awareness, self-compassion, self-confidence) was identified as a relevant topic. The authors noted that LKM training could contribute, among other benefits, to enhance self-care and compassion. Bibeau et al62 analyzed qualitative data from three psychotherapists who had already been practicing regular mindfulness meditation and engaged in a compassion meditation training over a 4-week period. The core content of these exercises was LKM. They carried out semi-structured interviews and conducted a phenomenological analysis of responses before, after and at 1-month follow-up. The therapists perceived that the compassion meditation training had an effect on their self-compassion skills. In their narratives, self-compassion appeared as the basis of their compassion for others, and as the key factor that enabled them to be more present, accepting and tolerant of their clients’ suffering. The narrative themes identified were very similar to those in the Boellinghaus et al61 study. Among the conclusions, the authors proposed to include compassion meditation training in the psychotherapy training curricula, as well as in burnout prevention workshops.

Other two studies assessed the effects of mindfulness programs. Dorian and Killebrew63 evaluated the impact of a 10-week mindfulness course delivered to 21 psychotherapists in training, using the Constant Comparative Method64 to analyze the participants’ self-reported experiences during those weeks. Most students stated that the mindfulness practice had helped them gain acceptance, compassion for self and others, and had increased their capacity for attention and awareness. Similarly, Felton et al65 studied the impact of an MBSR-based program in a group of 41 students from a master’s degree in mental health counseling. They used conventional content analysis.66 Participants described that, among other effects, they increased their capacity for self-compassion.

Finally, two studies evaluated the effects of the CFT program.57 Gale et al67 conducted an exploratory study in a sample of 10 therapists, aimed at assessing the effect of personal practice with the CFT program. Their responses to a semi-structured interview were analyzed using inductive thematic analysis and five main themes emerged. In particular, personal practice was said to improve both compassion for others and self-compassion. Although CFT was mainly designed to increase compassion, this protocol also produced improvements in self-compassion. The authors suggested using RCT designs and larger samples to further examine CFT-based training’s benefits. Similarly, Bell et al68 studied the effect of an adaptation of the CFT program among 7 cognitive-behavioral therapists. The researchers used Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis to analyze the participants’ responses to an interview about their programs’ experiences. The enhancement of self-compassion and emotion regulation skills emerged, among other themes, as a benefit of the training. Table 4 summarizes qualitative research on the effect of mindfulness and compassion-based interventions on the therapists’ self-compassion.

Table 4.

Qualitative Research on the Effect of Mindfulness and Compassion-Based Interventions on the Therapists’ Self-Compassion

| Study | Sample Size (N) and Type | Program Type | Duration of Training | Qualitative Methodology | Main Ideas/Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bell et al (2017).68 | N=6. Trainee cognitive-behavioural therapists | Adapted version (“internal supervisor”) of Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT) | 4 weeks | Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis | Increased ability to be self-compassionate: (a) increased awareness and sensitivity to one’s own difficulties (expressions of care, empathy and support); (b) their self-talks were “affirming”, “reassuring” and encouraging; (c) the change in internal dialogue was identified as a change in mind-set rather than solely an alteration to the verbal content of cognitions; (d) all participants identified a change in their self-to-self relationship and an increased ability to provide, and be open to, self-care (characterised as “kind” and “warm”) |

| Bibeau et al (2020).62 | N=3. Psychotherapists with regular practice in mindfulness | Compassion meditation | 4 weeks | Phenomenological Analysis | Improved therapist’s relationship with self: (a) self-compassion appeared to be the foundation of the compassion for others, the key factor that allow to be present, more accepting, and more tolerant toward the suffering of the clients, as well as more empathetic; (b) to feel less pressure to perform or to offer a quick fix that would alleviate the client’s suffering. |

| Boellinghaus et al (2013).61 | N=12. Psychological therapists in training | Loving-kindness Meditation (LKM) |

6 weeks | Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis | (a) all participants were more accepting of themselves in relation to difficult feelings, and distanced themselves more from self-critical thoughts; (b) they were more compassionate when feeling stressed by work, and gave themselves permission to be “a good enough student” and “take the pressure off”; (c) some used positive self-talk, and others encouraged themselves to set a better work-life balance and to engage in nurturing activities; (d) however, not all participants found it easy to be self-compassionate. |

| Dorian & Killebrew (2014).63 | N= 21. Female psychotherapists in training | Course on mindfulness | 10 weeks | The Constant Comparative Method of analysis (Glaser, 1965) Dedoose™ software program | (a) most students stated that practice helped them gain compassion for self and others: letting go of negative judgments; (b) this theme covers a range of qualities that allow participants an understanding of self or other in a thoughtful way; (c) it also touches the concept of “loving-kindness”, which centers on sensitive and benevolent contemplation. |

| Felton et al (2015).65 | N=41. Master’s-level graduate students in mental health counselling | Program based on Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program (MBSR) | 15 weeks | Content Analysis (Hsieh and Shannon 2005). | (a) increased acceptance and non-judgmental attitude toward their own clinical abilities and limits; (b) to put less pressure to perform, reply instantly, offer amazing insight, use the right skill, and to “do something”; (c) importance of boundaries when reflecting on self-compassion: “being more gentle with myself and respect my mind and body, giving myself space and time to feel vulnerable, sick, or tired, without trying to always fight it or push my limits all the time” |

| Gale et al (2017).67 | N=10. CFT-trained therapists | Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT) | Advanced training in CFT; personal practice workshops; CFT-specific supervision | Inductive Thematic Analysis | Personal practice improved both compassion for others (particularly their clients), and self-compassion: (a) they were more aware of how they were relating to themselves; (b) enabled them to face their emotions and to cope with difficult emotions; (c) being self-compassionate also felt to be important as it meant that participants were able to be compassionate toward others. |

Discussion

Self-compassion may contribute to important benefits for mental health professionals, as the research reviewed highlights.

First, self-compassion may be a protective element against psychosocial risks that are present in therapeutic work, such as compassion fatigue, burnout, or secondary traumatic stress. In this regard, compassion is also a factor contributing to the quality of working life. Cross-sectional research is consistent in pointing to a negative relationship between self-compassion and these risks associated with therapeutic work (e.g.27–32). Interestingly, self-compassion may act as a protective element against the development of depressive symptoms when the professional is exposed to high levels of burnout.29 In addition, self-compassion appeared linked to a better balance between professional and personal life, with self-compassion mediating the relationship between work-life balance and emotional exhaustion.28 From a qualitative perspective, Patsiopoulos and Buchanan45 have also mentioned, among the benefits of self-compassion, better management of occupational stress and challenges involved at therapeutic work. Here, compassion is a factor contributing to quality of working life. These results are consistent with intervention studies. For instance, Eriksson et al22 found that an Internet-based program aimed at cultivating mindfulness and compassion for self and others produced significant decreases in perceived stress and burnout symptoms in practicing psychologists. In addition, changes in these variables were more strongly associated with self-coldness than self-warmth, ie the self-compassion’s negative and positive dimensions respectively. Finlay-Jones et al16 found that psychology trainees who received online training in self-compassion described positive effects on their therapeutic work, increased resilience to stress, recognition of the value of self-care practices, increased authenticity, responsiveness, and an increased ability to “be present” and “practice what you preach”.

Second, self-compassion is also associated, in general, with numerous benefits for the psychological well-being and mental health of professionals. For example, cross-sectional research has negatively connected self-compassion with depression, psychological distress (e.g.,29,31,38,39) and positively with well-being.27,37 Again, qualitative research points in the same direction, finding that one of the benefits of self-compassion refers to the overall feeling of well-being and the perception of physical, psychological and emotional health.45 There is also robust evidence from four experimental and quasi-experimental studies3,16,22,23 indicating that training self-compassion not only significantly improves self-compassion and mindfulness skills but also reduces anxiety and depression. In addition, some intervention studies reported improvements in psychological well-being,3 happiness, and less stress and emotional regulation difficulties.16

Third, self-compassion appeared related to experiential avoidance, acceptance, and tolerance of uncertainty or ambiguity. These results have been repeatedly obtained in cross-sectional research,39,42 and have been similarly echoed in qualitative research.46 The connections between self-compassion and such processes (ie lower experiential avoidance, higher tolerance to uncertainty) could contribute to explain self-compassion beneficial effects. For instance, Yela et al8 found that the reductions in experiential avoidance after a Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC) program delivered to a community sample accounted for changes in depression, anxiety and well-being in a study conducted. However, this suggestion is yet to be tested in a mental health professionals’ sample.

Fourth, self-compassion itself is a variable that has been frequently proposed as an explanatory variable for psychological benefits linked to other variables, such as the negative association between mindfulness and burnout. This is a result that has appeared several times in cross-sectional research that has conducted mediation analyses, finding that self-compassion would be involved in the processes that explain the salutary effects of mindfulness in mental health professionals. For example, self-compassion mediates the relationship between profession and compassion fatigue,30 between self-critical perfectionism and burnout or depression,31 and mindfulness and burnout-related variables.32 Hence, self-compassion is revealed as a psychological mechanism that may underlie the positive effects derived from other variables.

Fifth, therapists who receive training in mindfulness or compassion-based programs also experience improvements in their levels of self-compassion. Here, evidence again comes from both quantitative and qualitative research. Training professionals in compassion skills (eg using CFT, CCT or other compassion-focused programs) has demonstrated benefits in self-compassion too.13,56,58 The effect of mindfulness-based interventions (MBSR and MBCT) on increasing self-compassion scores has been widely reported.48–51,53–55 To date, only one controlled study has compared the effects of a mindfulness program (MBSR) with a self-compassion program (MSC) among psychotherapists in training.23 This research found that mindfulness and self-compassion scores presented similar trajectories in MBSR and MSC groups from pre- to post-training, with participants in both the MBSR and in the MSC groups significantly improving their self-compassion scores. However, when the comparison with a control group was taken into account, each program appeared to produce effects on those skills more directly trained. The MBSR program produced significant effects on mindfulness but not on self-compassion, whereas the MSC program enhanced self-compassion and mindfulness, compared to CG.

Concerning qualitative studies, from the participants’ discourse emerges the idea that trainings in compassion,62,67,68 mindfulness63,65 and LKM61 enhance the professionals’ self-compassion. These results must be interpreted with caution, as all qualitative studies used very small and non-representative samples. However, these studies may constitute a basis for designing new research and provide us with a subjective but valuable perspective often neglected, ie the access to the participants’ self-reported experiences prior, during and after this kind of training.

Sixth, the beneficial effects of being a self-compassionate therapist do not exclusively redound to the professional, but also have positive effects on the therapeutic relationship and the clients themselves. In fact, self-compassion is related to compassion towards clients, therapeutic efficacy and the competence of the practitioner. This result has repeatedly appeared in cross-sectional research (e.g.,32,37,38,41–43). In addition, self-compassion has been found to explain, to some extent, the association between mindfulness and self-efficacy, self-rated professional competence,41 therapeutic presence,38 compassion for others,43 and compassion to clients.32 However, the results cannot be said to be conclusive. Firstly, these are studies that rely on self-report measures and therapists’ perceptions have sometimes been found to be at odds with those of clients (e.g.42). On other occasions, the association between self-compassion and compassion for others has not been found to be significant (e.g.27). Qualitative research has also pointed to beneficial effects of self-compassion on aspects related to therapeutic competence and the establishment of an effective therapeutic relationship.45,46 However, due to the characteristics of these studies, these findings are based on the subjective assessments of the practitioners, and the client’s perspective is yet to be incorporated.

Seventh, the positive effects derived from a self-compassionate attitude make it a priority to train this quality during the training of therapists. This idea was derived from the discourse of the participants in Barton’s qualitative study.15 However, this recommendation is also frequently mentioned in cross-sectional research’s conclusions,27,30–32,40,41 especially when self-compassion is viewed as a protective element against potential occupational risks such as burnout or compassion fatigue. Similar recommendations are also shared by authors of the most rigorous experimental and quasi-experimental studies,3,16,22,23 who defend that future clinical psychologists should receive training in self-compassion during their education.

Eight, there are however psychological barriers among therapists that may make them wary of cultivating self-compassion. For example, the idea that being self-compassionate is selfish, as identified in the qualitative study by Barton.15 However, when the therapist is self-compassionate, this disposition can lead to the breaking down of other barriers that mental health professionals sometimes encounter. For example, Aruta et al40 found in a cross-sectional study that self-compassion is positively associated with mental-help seeking intentions and attitudes, thus contributing to the search for effective solutions to situations compromising the professionals’ mental health, an issue that even today is perceived as stigmatizing. The practice of self-compassion may also entail difficulties and may even be aversive for some individuals. For example, in the context of the MSC program, the backdraft effect has been identified,3,9 in which the practice of self-compassion elicits the activation of difficult emotions. Self-compassionate practices can make the person aware of wounds and fears that had remained hidden and that may painfully emerge during the training. This effect is not seen as necessarily negative;3 on the contrary, it may be part of the process of generating a self-compassionate attitude. In any case, these possible effects lead us to emphasize the convenience that the trainings be supervised by experts.9,61

Limitations and Future Research

We have also identified some limitations in our review of previous literature. Research, in general, on the topic of the benefits of self-compassion in mental health professionals is scarce. For instance, only four studies used experimental or quasi-experimental designs to address the topic of the potential benefits of self-compassion interventions delivered to therapists. There has been an evolution, however, concerning this point. The first intervention studies agreed on the need to carry out RCT studies comparing the effect of self-compassion interventions with an alternative stress-management intervention and a waitlist control group.3,16,22 Another remarkable development is the analysis of processes that may account for the effects of self-compassion interventions. For example, Finlay-Jones et al39 conducted mediation analyses and found that difficulties in emotional regulation mediated the beneficial effect of self-compassion training on stress. However, as Finlay-Jones et al16 and Jiménez-Gómez et al23 suggested, more experimental research on mediation processes accounting for the beneficial effects of self-compassion interventions is needed.

As a conclusion, future research should conduct more RCT studies with active CG, using larger samples of mental health professionals, with follow-ups, and focused not only on self-compassion benefits but also on identifying possible mediating variables involved in the positive outcomes. In addition, using objective psychophysiological measures, such as cortisol,16 is recommended.

Most of the research reviewed used cross-sectional designs, which allows identifying associations between self-compassion and other variables, but does not unequivocally determine whether self-compassion causes beneficial outcomes. However, cross-sectional research is valuable and may well serve to complement findings obtained using other research designs.