Abstract

Butachlor (BUT) is a widely used herbicide that can cause environmental problems when used excessively. BUT has been found to exist in large quantities in the water environment so far. As an agricultural pre-emergent herbicide, BUT can enter the water environment through multiple channels and cause pollution. This study investigated the mechanism of three types of microplastics (MPs): polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) to remove BUT from water. The adsorption behavior between MPs and BUT under different factors, namely pH, salt ion concentration, and aging, was investigated. This study further investigated the desorption and aging of BUT-adsorbed MPs. In this research, the adsorption capacity of BUT by PE, PP, and PVC are 13.65 μg/g, 14.82 μg/g, and 18.88 μg/g, respectively, and the order of carrier effect was: PVC>PP>PE. Experiments show that MPs have low adsorption performance on the microgram level for BUT. The adsorption behavior of PE, PP, and PVC on BUT conformed to pseudo-second-order kinetics, indicating the presence of physical and chemical adsorption. The Langmuir isotherm model fits well, indicating that the adsorption is a single-layer adsorption process. The pH value causes slight fluctuations in the overall carrier effect. Low concentration of salt ions can inhibit the carrier effect, and high concentration will promote the interaction between MPs and BUT. Aging experiments show that the carrier effect of the original materials was higher than the adsorption capacity of hydrogen peroxide and MPs after acid aging, and acid aging can cause the adsorption capacity to drop significantly.

Keywords: Adsorption mechanisms, Analysis and aging, Butachlor, Microplastics, Thermodynamics

Introduction

Plastic products are widely used in industry, agriculture, scientific research, and other fields due to their easy processing and low price. Among them, a class of plastics with particle size less than 5 mm is called microplastics (MPs) (Dai et al. 2022). Since 2018, the output of the European plastics industry has been decreasing year by year. In the first half of 2020, the production of plastics dropped sharply due to COVID-19, and gradually recovered in the second half of the year (Plastic Europe 2020). During COVID, MPs contamination increased dramatically, which was attributed to the release of MPs from masks made of polymer materials into the environment (Shen et al. 2021). During the COVID-19 epidemic, the use of key personal protective items such as goggles, gowns, masks, and gloves to prevent infection has increased dramatically (Hossein et al. 2021). According to The World Health Organization, health care workers need about 890,000 masks per month during the pandemic, which is a huge number of 129 billion masks per month for the world's 7.8 billion people (The World Health Organization 2020). The sources of MPs in water include terrestrial input, coastal tourism, shipping, aquaculture, and fisheries (Sun et al. 2016). Ocean currents, the atmosphere, and other natural environments can transport plastic debris and microplastics. Plastic pollution has even existed in sparsely populated arctic regions and deep seas, causing serious impacts on ecology and climate (Bergmann et al. 2022). As an emerging pollutant, MPs are easily ingested by aquatic organisms, and cause ecotoxicity and genotoxicity to plants, which have attracted much attention (De et al. 2019; Jiang et al. 2019). MPs can also adsorb and carry hydrophobic organic contaminants, due to their hydrophobicity (Bakir et al. 2014). In 2011, the consumption of plastic film was 2.29 million tons in China (Li et al. 2016). Current scientific research on MPs is mainly focused on aquatic systems. While terrestrial systems could theoretically store more MPs than oceans, aquatic systems have been estimated to store 4-23 times more MPs than terrestrial systems (Nizzetto et al. 2016). Landfills and urban space are most affected by MPs, followed by agricultural ecosystems (Wang et al. 2016). The recycling rate of plastic products in the process of improving agricultural quality and efficiency is very low, resulting in a large amount of plastic pollution entering water environment (Wang et al. 2016). The pollution of MPs to the environment has gradually received more attention, and its harm to nature has gradually emerged (Rillig 2012). In addition, as the most common MPs types, polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) have high stability and are not easily degraded by microorganisms (Franzellitti et al. 2019). The past decade has seen the rapid increasing research on MPs in many fields (Borrelle et al. 2020). Global problems and threats caused by MPs are urgent (MacLeod et al. 2021). There was evidence that MPs may affect the phase distribution in sediments and water because of interactions with organic matter (Huffe and Hofmann 2016). The research about the interactive behavior of organic pollutants on MPs could help researchers to further grasp the environmental impact of organic pollutants in aquatic ecosystems (Ma et al. 2016). MPs in the environment have a strong interaction with organic matter (Rochman et al. 2013; Wang and Wang 2018). Several studies have documented that adsorption capacity is affected by the types and concentrations of organic pollutants, and external environmental factors (Chua et al. 2014; Hu et al. 2017). Some studies have reported that different kinds of MPs have different adsorption capacity to organic pollutants (Rochman et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2015). The physical and chemical properties of MPs, such as particle size and surface properties, also affect their adsorption capacity (Frias et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2018b). Besides, the particle sizes of MPs, pH value, and ionic strength of MPs could affect the adsorption capacity (Huffe and Hofmann 2016). However, the contribution of each factor cannot be separated and may be due to a combined effect. Some studies on the mechanism of action of MPs have found that pH and salt ion concentration can affect the electrostatic interaction of pollutants with MPs (Wang et al. 2015; Wu et al. 2019). Hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions occupied a higher influential component in the adsorption mechanism of MPs (Zhang et al. 2020). Adsorption isotherms and kinetics of MPs on other organic molecules (phenanthrene, tonalide, and benzophenone) have been studied and external mass transfer was found to slow down with increasing adsorption (Seidensticker et al. 2017). Different isotherm models to fit the equilibrium isotherm of adsorption of two organic phosphates on PVC and PE have been studied (Chen et al. 2019). The results showed that the Freundlich isotherm could be better used to describe the adsorption isotherm (Chen et al. 2019).

Butachlor (BUT), with chemical formula is C17H26ClNO2 (Table 1), is a preemergence herbicide whose mechanism of action is to inhibit the development of plant tissues (Mohanty et al. 2001). Tests have proved that BUT can effectively reduce the number of weeds and has a positive impact on crops (Chander and Pandey 1996; Gogoi and Kalita 1996). BUT is used at large quantities in Asian countries like China and India (Abdullah et al. 1997; Mohanty et al. 2001), and Asia consumed a huge amount of BUT every year, so BUT inevitably entered the natural world through local channels (Abigail et al. 2015). BUT have been detected in soil, water, and sediments in many locations (Abigail et al. 2015; Chau et al. 2015; Jolodar et al. 2021; Kaur et al. 2021). In recent years, pesticides have been widely used because they could reduce crop damage and increase yields. But they entered nature through different ways in the process of water pollution. Pesticides can cause a variety of health effects on the skin, gastrointestinal tract, nerves, cancer, respiratory system, and reproductive endocrine, etc., especially for vulnerable groups such as children, pregnant women, and the elderly (Herrero-Hernández et al. 2013; Seblework et al. 2016). In this study, the adsorption effect of MPs on hydrophobic organic pollutants (HOCs) in the environment has been studied. Therefore, this study aimed at two pollutants and investigated whether they would cause greater pollution and adverse effects on the environment through adsorption experiments.

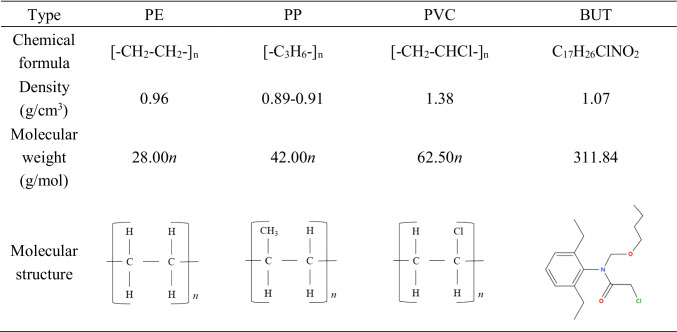

Table 1.

The properties of PE, PP, PVC, and BUT.

MPs can continuously migrate and transform in water bodies (Isobe et al. 2015). MPs themselves are pollutants and may combine with other hydrophobic organic pollutants in water to form a joint pollution source (Ma et al. 2016). MPs and pollutants may interact, leading to increased toxicity of the superimposed products, but may also reduce the free state of pollutants in the environment at the same time (Wang et al. 2015). So this work conducted an adsorption test on the mechanism of MPs and BUT. In this article, according to the idea of adsorption, the effects of adsorption kinetics, isotherm, pH, and salt ionic strength on the interaction of BUT with PE, PP, and PVC were studied on MPs. The effect of reducing the pollution of herbicide BUT to water environment through aging and desorption was further discussed. The results provide relevant ideas for future research on the migration and transformation of organic pollutants and MPs.

Materials and methods

Materials

Three kinds of high density MPs: polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) were purchased from Guangdong Fengtai Polymer Material Co., Ltd., washed with ultrapure water, dried at room temperature, and put in a clean fresh-keeping bag for later use. BUT was from Shandong Qiaochang Modern Agriculture Co., Ltd. Water solubility of BUT was 20 mg/L at 25 oC (Toan et al. 2013). The lowest detection limit of BUT measured by high performance liquid chromatography was 1.00 μg/L. The desorbent was CaCl2 solution. For the preparation of aged MPs added the original MPs (10.00 g) to a 250 mL glass bottle, and then mixed 200 mL of 3% and 20% H2O2 solution or HNO3/ H2SO4 (1:3, v/v). The solution was slowly added to the bottle and stirred with a vortex mixer for 1 minute to ensure that the MPs in the solution are mixed well. In order to ensure that the MPs were in full contact with the solution during the aging process, used a constant temperature shaker to shake at a constant speed for 240 h of aging. H2O2 with a concentration of 3 %, H2O2 with a concentration of 20%, and HNO3/H2SO4 (1:3, v/v) mixed solution were selected as oxidant to obtain oxidized MPs, respectively. The aging MPs were washed with deionized water, dried at room temperature, and placed in a clean storage bag for later use.

Characterization of MPs

Fourier transform infrared absorption spectrometer (FT-IR, Nicolet Antarisll, Thermo Scientific, USA) was used to analyze the surface functional group of MPs used in the experiment. A cold-field scanning electron microscope (SU8010, Hatachi High-Technologies Corporation, Japan) characterized micro-surface structure, the surface morphology of materials, and analyzed the crystallinity of different particles by X-ray diffraction (XRD, D8 Advance, Bruker, Germany).

Batch experiment

The experiment considered the interaction between BUT and MPs under the conditions of adsorption time, initial concentration, different pH, different salinity, and different aging conditions. The mixture of sample was shaken on a constant temperature shaker and with the temperature set to 25 °C. After equilibrium, the MPs in the mixture were filtered through a 0.22-μm filter membrane (13 mm diameter). The filter membrane is made of polyethersulfone (PES), and the housing is made of medical grade polypropylene. High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (LC-10A, Shimadzu Corporation, Japan) with Eclipse Plus C-18 (5 μm, 4.6 mm×250 mm) column (Agilent Technologies) was used to measure the equilibrium mass concentration of BUT. C18 column was used as the stationary phase, methanol and water were used as the mobile phase, and φ (methanol): φ (water): φ (glacial acetic acid) = 80: 20: 0.5 was selected for separation, extraction, and determination, and a standard operating curve for BUT was obtained with the concentration of BUT and its corresponding peak area.

In the batch adsorption experiment, this study used single-factor variables to test. Under the influence of the adsorption time and the kinetics experiment, 5.00 mg MPs and 25.00 mL of BUT solution with a concentration of 12.00 μg/L were put into an erlenmeyer flask, and the pH was adjusted to 7.0, and the different reaction time intervals were set. The parameters were respectively 0–120 min. In the adsorption isotherm experiment, the mass concentration of BUT was set to 2.00–18.00 μg/L, the addition amount of MPs was 5.00 mg, and the adsorption capacity was determined by constant temperature oscillation at 25°C for 60 min. During the test of the influence of salinity and pH on adsorption, the salinity of the solution NaCl was adjusted to 0–1000.00 mg/L; 0.10 M HCl and 0.10 M NaOH were used to make the pH reach the environment required for the experiment: increased from 3.0 to 11.0. The above experiments were carried out in a constant temperature (25°C) shaking shaker in the dark, repeated three times to reduce errors, and a blank control was set to exclude the influence of other factors.

After the adsorption experiment, MPs particles were separated from the aqueous solution with a disposable needle filter (diameter 13 mm, PES filters) with a pore size of 0.22 μm. 0.20 M CaCl2 were used as desorbents to desorbed for 60 min, repeatedly filtered, and then measured the concentration of BUT after desorption.

Adsorption model and data processing

For the interaction between MPs and BUT, using the models to fit and simulate the corresponding process can provide an important description of the mechanism at the molecular level (Bergaoui et al. 2022). In this study, the pseudo-first-order (PFO) model and the pseudo-second-order (PSO) model were used to study the adsorption kinetics (Jiang et al. 2021). In addition to the classical Langmuir and Freundlich models, adsorption isotherms were fitted and analyzed by Dubinin-Redushkevich (D-R), Temkin, Redlich-Peterson (R-P), and linear models (Zhao and Dai 2022). The equations of each model are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Kinetic models and isotherm models used.

| Name | Equations | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinetic models used | Pseudo-first-order | ln(qe − qt) = ln(qe) − k1t | (Jiang et al. 2021) |

| Pseudo-second-order | |||

| Isotherm models used | Langmuir | ||

| Freundlich | |||

| Dubinin-Redushkevich(D-R) | lnqe = ln qm − βε2 | ||

| Temkin | |||

| Linear | qe = kdCe | ||

| Redlich-Peterson(R-P) |

In the above adsorption kinetic equation, qt, adsorption amount (μg/g) at time t; qe, equilibrium adsorption amount (μg/g); t, time (min); k1, first-order kinetic model rate constant (min-1); k2, second-order kinetic model rate constant [μg/(g·min)]. In the adsorption isotherm equation, Langmuir model: Ce, equilibrium mass concentration of pollutants in the liquid phase (μg/L); kd, linear distribution coefficient; KL, Langmuir isothermal model constant (L/μg); qm, Langmuir’s maximum single-layer coverage capacity (μg/g); RL is an equilibrium parameter to determine effective adsorption. When 0<RL<1 means the adsorption is favorable, RL>1 means it is unfavorable for adsorption, RL=1 means linear adsorption, RL=0 means irreversible adsorption; Ci, the initial concentration of the solution (μg/L). Freundlich model: KF, Freundlich isotherm constant (L/μg); nf, rate constant of the internal diffusion model; D-R model: β (mol2/J2): constant related to the free energy of adsorption; ε (J2/mol2), the Polanyi coefficient; Temkin model: R, universal gas constant; T(K), open temperature in the reaction system; bT, Temkin equation constant reflecting the heat of adsorption; KT, equilibrium binding constant reflecting the maximum binding energy; linear model: qe (μg/g) is the adsorption amount at adsorption equilibrium, Ce (μg/L) is the equilibrium mass concentration of pollutants in the liquid phase; kd is the linear distribution coefficient; R-P model: KR and α (g/L): the equation constants that maximize R2; β, the Redlich-Peterson constant.

Results and discussion

Physical and chemical properties of MPs

SEM images of materials are shown in Fig. 1. From the SEM of MPs, PE, and PP particles appear to be less than 150 microns in diameter and relatively regular. Fig. 1 shows that PE has particles smaller than PP or PVC, which have an impact on the interaction. Small particles of PE produce a larger specific surface area. Compared with PE and PP, the surface of PVC becomes rougher, with small cracks and pores, and has a large number of granular protrusions and dents and microporous structure on the surface. Studies have shown that the amorphous areas on the surface of PVC polymers are prone to open structures, cracks, and spherical protrusions (Arnold 1995).

Fig. 1.

SEM images of the PE, PP, and PVC (a PE, b PP, c PVC).

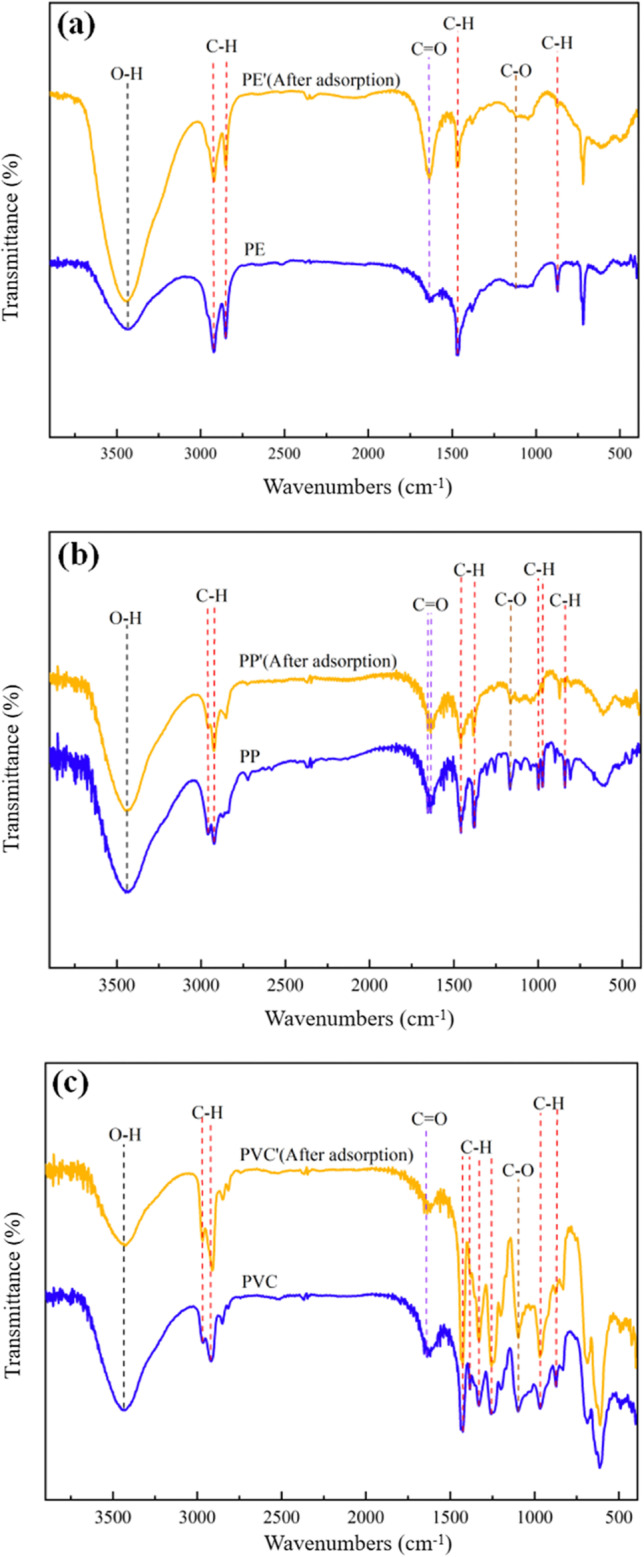

The changes of the surface groups of the MPs are shown in Fig. 2. Under three different MPs, there are no characteristic peaks in PE and PP. According to the FTIR database, this peak is derived from the tensile characteristic peaks of O-H, -CH, and C-O, which indicates that there is functional group oxidation on the surface of PE and PP. Since MPs do not contain oxygen element, the oxygen contained before adsorption is due to the occurrence of oxidation reaction and the infrared crest appears. Similar to PE and PP, the absorption peak of PVC near 3419 cm-1 is mainly caused by the tensile vibration of O-H, and the absorption peak near 2930 cm-1 is mainly caused by the anti-stretching vibration of alkane-CH2. The characteristic carbonyl absorption peak near 1640 cm-1 is mainly caused by the plasticizer and other additives contained in PVC, while the fluctuation at 609 cm-1 corresponds to the C–Cl stretching vibration from PVC. In the fluctuation 600–750 cm-1, there are multiple absorption peaks caused by C–Cl stretching vibration, indicating that there are different structures on the PVC molecular chain. Therefore, surface oxidation also lead to the presence of oxygen-containing functional groups in MPs (Huffer et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2019).

Fig. 2.

FTIR images of the PE, PP, and PVC (a PE, b PP, c PVC).

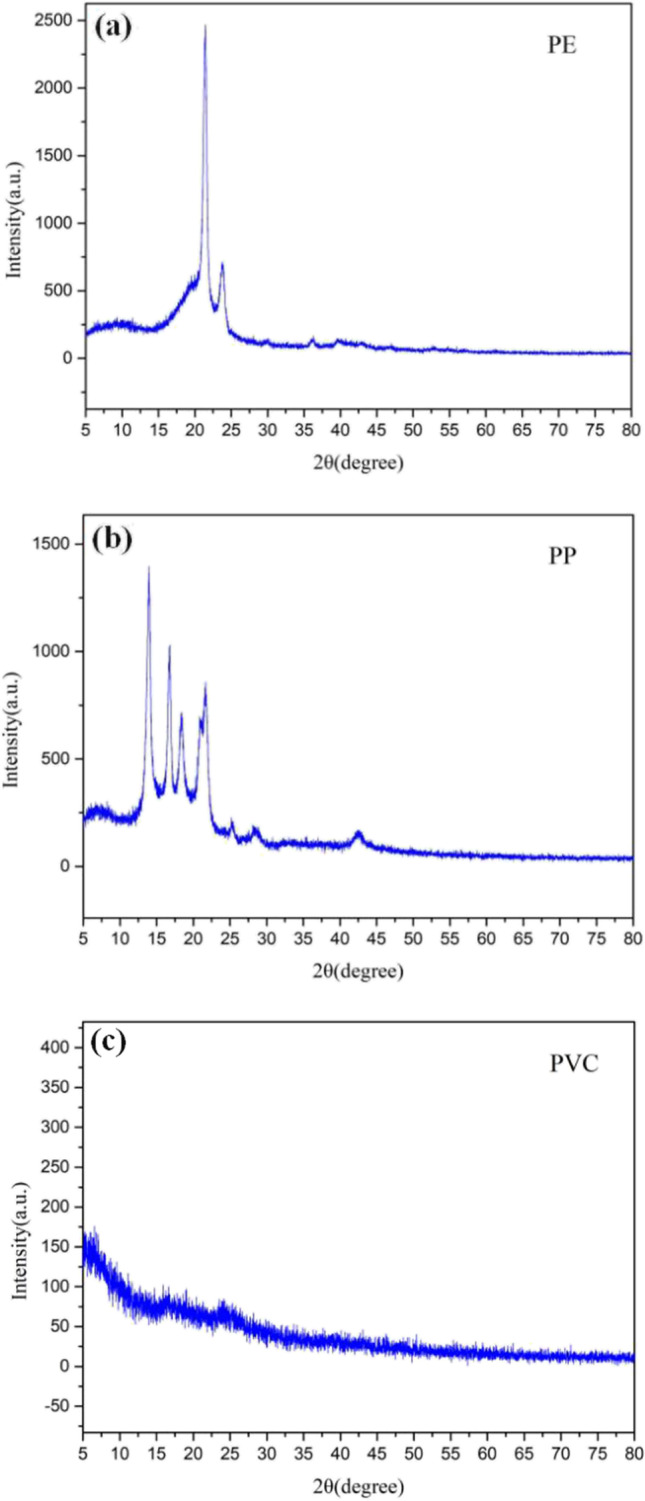

The XRD spectra of MPs are shown in Fig. 3. According to the XRD pattern analysis results, the half-width of PVC <the half-width of PP <the half-width of PE. Compared with PP, the crystalline peak intensity of PE has no significant change. However, PVC is different from PP and PE. Compared with PP and PE, the crystal diffraction peaks of PVC are obviously different, which show that the surface crystal structure of PVC is quite different in the relative range.

Fig. 3.

XRD images of the PE, PP, and PVC (a PE, b PP, c PVC).

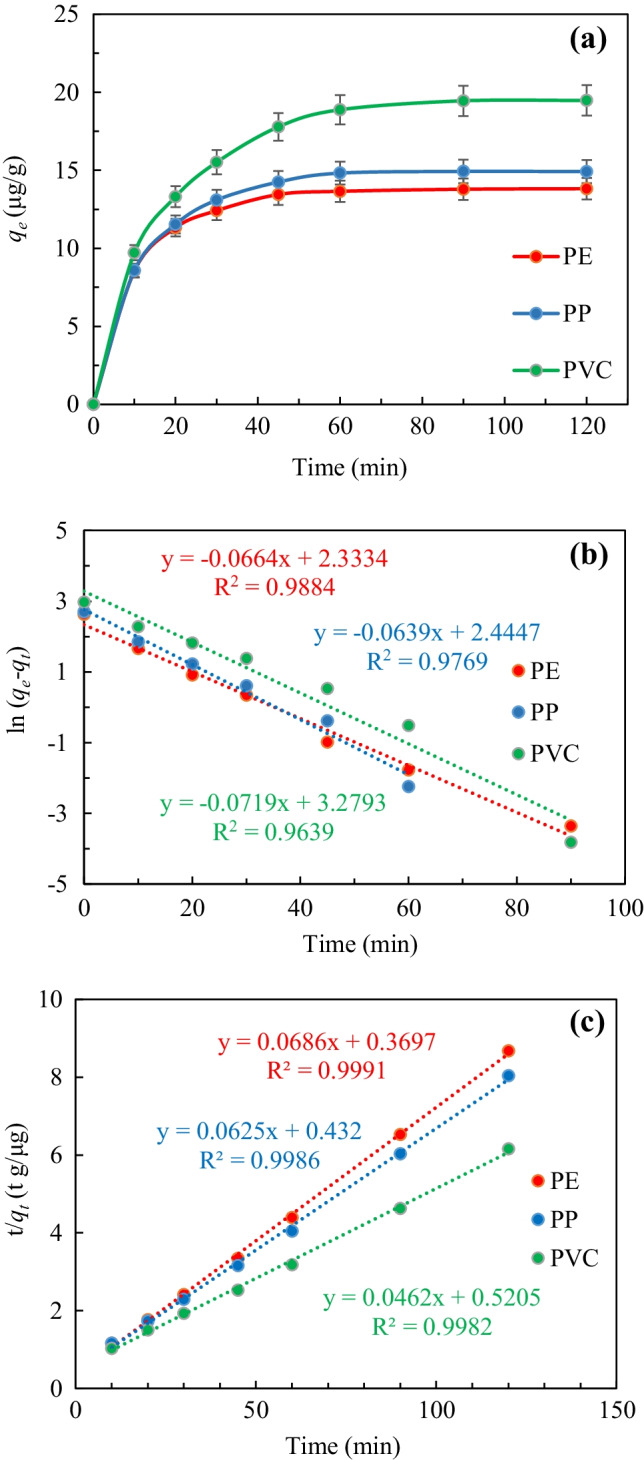

Adsorption kinetics

The adsorption kinetic curves of the MPs are shown in Fig. 4. The qe of MPs are 13.65 μg/g (PE), 14.82 μg/g (PP), and 18.88 μg/g (PVC). Compared with PE or PP, qe of BUT by PVC is quite distinct. This may be due to the increase of oxygen-containing functional groups on the surface of PVC, which increased the polarity of the particle surface (Huffer et al. 2018). There is a strong interaction between two polar molecules. BUT is a polar molecule, which leads to stronger interaction with PVC (Liu et al. 2019).

Fig. 4.

a Kinetic models of PE, PP, and PVC on butachlor; b pseudo-first-order; c pseudo-second-order.

The kinetic analysis of the adsorption of BUT by the PFO and the PSO model is shown in Table 3. The PFO dynamics fitting R2 is lower than the PSO dynamics (0.9639–0.9884), and the fitted parameters differed greatly from the actual adsorption amount. The pseudo-second-order kinetics had a good degree of fit. The PSO kinetics is more in line with the adsorption process, indicating that the adsorption process is dominated by chemical adsorption (Amamra et al. 2021; Huffer et al. 2018).

Table 3.

The kinetic parameters of BUT adsorption onto MPs.

| Samples | Pseudo-first order | Pseudo-second order | Experimental qe (μg/g) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k1 (min-1) | qe,cal (μg/g) | R2 | k2 (g/μg·min) | qe,cal (μg/g) | R2 | ||

| PE | 0.0664 | 10.31 | 0.9884 | 0.0127 | 14.58 | 0.9991 | 13.82 |

| PP | 0.0639 | 11.53 | 0.9769 | 0.0090 | 16.00 | 0.9986 | 14.93 |

| PVC | 0.0719 | 26.56 | 0.9639 | 0.0041 | 21.65 | 0.9982 | 19.48 |

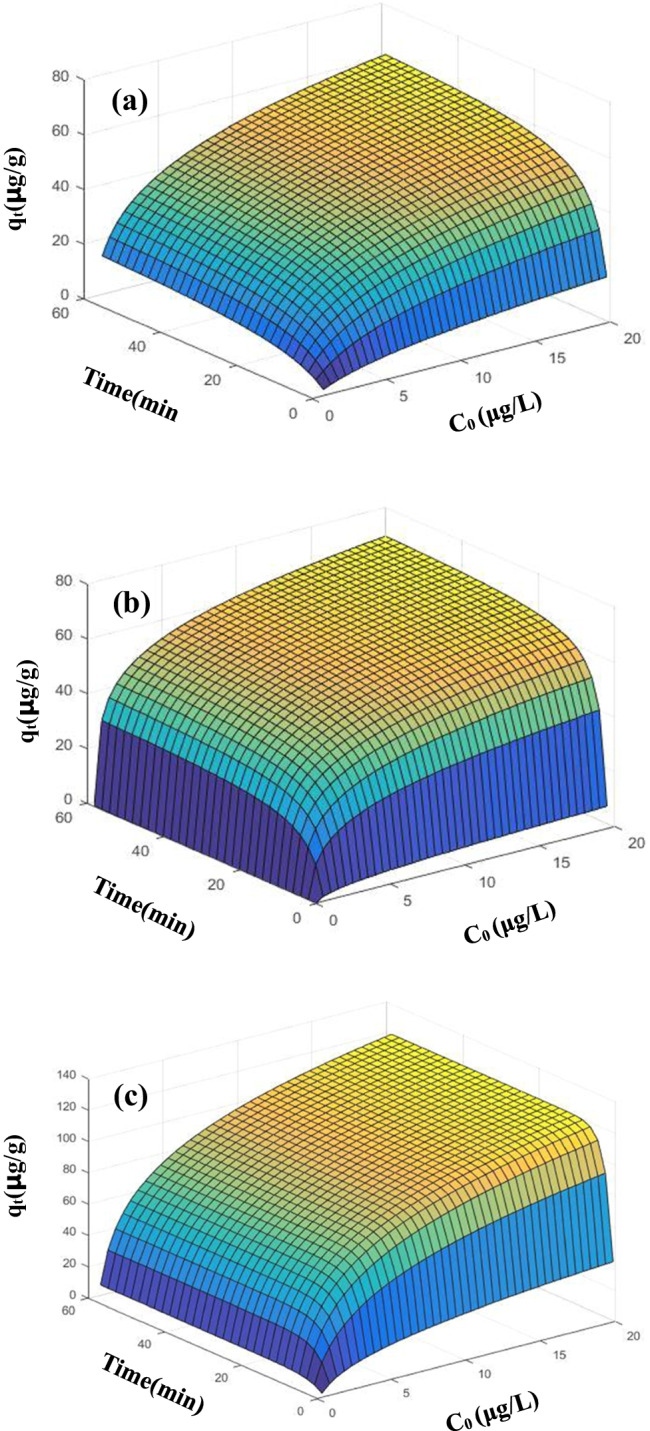

The linear adsorption isotherm equation assumes that the amount of adsorption varies linearly with the equilibrium mass concentration of the pollutant. The linear regression response analysis of qe, T, and C0 is performed to obtain a higher regression coefficient (> 0.9977), which is shown in Fig. 5. The experiment can use models to define and predict T and qt under different C0 conditions (Mane et al. 2007; Wang and Wang 2018). The three different MPs showed different correlation predictive properties. The increase of T and C0 led to a rapid increase in the role of PP carrier, and PVC was the opposite. Interestingly, PE is more special, C0 leads to slow growth, and T leads to rapid excitation. This is basically consistent with the kinetic test data and fitting.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of experimental data points given by symbols and the surface predicated (a for PVC, b for PE, c for PP).

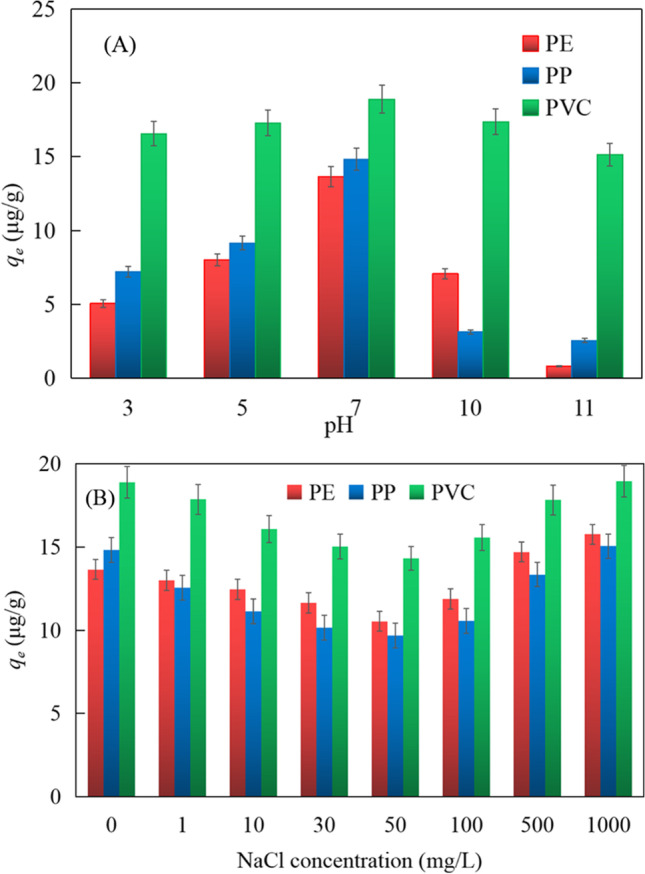

Effect of solution pH

The effect of pH on the carrier effect of MPs on BUT is shown in Fig. 6(A). The results show that the adsorption capacity varies from 0.80 to 18.88 μg/g, and the adjusted pH varies from 3.0 to 11.0 in Fig. 6(A). It is worth noting that under the same pH value less than 7.0, the adsorption capacity of BUT on PVC MPs is higher than that of PE and PP. When the pH was increased from 3.0 to 7.0, the adsorption capacities of PE, PP, and PVC increased from 5.07 to 13.65 μg/g, 7.23 to 14.82 μg/g, and 16.56 to 18.88 μg/g, respectively. When the pH value was further increased above 7.0, the adsorption capacity of PE and PP decreased significantly, and PVC also decreased slightly. The adsorption capacity is the highest in the BUT solution of pH 7.0 in Fig. 6(A). As shown in Fig. 2, the main chemical bond tables in the PVC structure can be shown (Gulmine et al. 2002). After adsorption, the characteristic peak of CH2 becomes stronger. There is electrostatic interaction between MPs and BUT under acidic conditions. The increasing alkalinity gradually increases the electronegativity of the MPs surface, which leads to an increase in electrostatic repulsion, thereby inhibiting electrostatic interactions, while the positive dissociation of hydrophobic neutral adsorbed molecules reduces hydrophobic interactions. However, the adsorption capacity of MPs varied little in the univariate test. When pH > 7.0, the electrostatic force between MPs and BUT decreased. The adsorption process of BUT on MPs is controlled by hydrophobic interaction (Jia et al. 2019). Under acidic conditions (when the pH is low), adsorption is mainly affected by electrostatic interactions. Under alkaline conditions, the adsorption is mainly affected by hydrophobic interactions.

Fig. 6.

A Effect of solution pH on the adsorption of butachlor by PE, PP, and PVC. B Effect of ionic strength on the adsorption of butachlor by PE, PP, and PVC.

Effect of the ionic strength

As shown in Fig. 6(B), under different salinity conditions, the adsorption amount of PE, PP, PVC to BUT is different, which indicates that the change of solution salinity has a certain influence on the adsorption amount of MPs. Studies have shown that the electrostatic interaction between MPs and chemical pollutants is weak (Paula et al. 2019). Similar studies believe that carrier interactions in solution are affected by hydrogen bonding (Zakrajšek 2014). The surface morphology of MPs has changed, but the H bond belongs to the stronger force among the intermolecular forces. Under low-concentration conditions (NaCl concentration is 3.00 mg/L-50.00 mg/L), the increase of salt ion concentration has a negative effect on the carrier function of MPs. But what is interesting is that when the salt ion reaches 100 mg/L, the adsorption capacity of MPs on BUT rebounded. When the concentration is continuously increased to 500.00 mg/L or even 1000.00 mg/L, the adsorption capacity gradually increases, and the adsorption effect is even enhanced. This is because with its gradual addition, when the concentration is low, it becomes a weakly alkaline background solution, which will cause certain hydrolysis (Oh et al. 2013). Therefore, the change of salinity presents a trend of first decreasing and then increasing on the adsorption of PE, PP, and PVC to BUT.

Adsorption isotherm

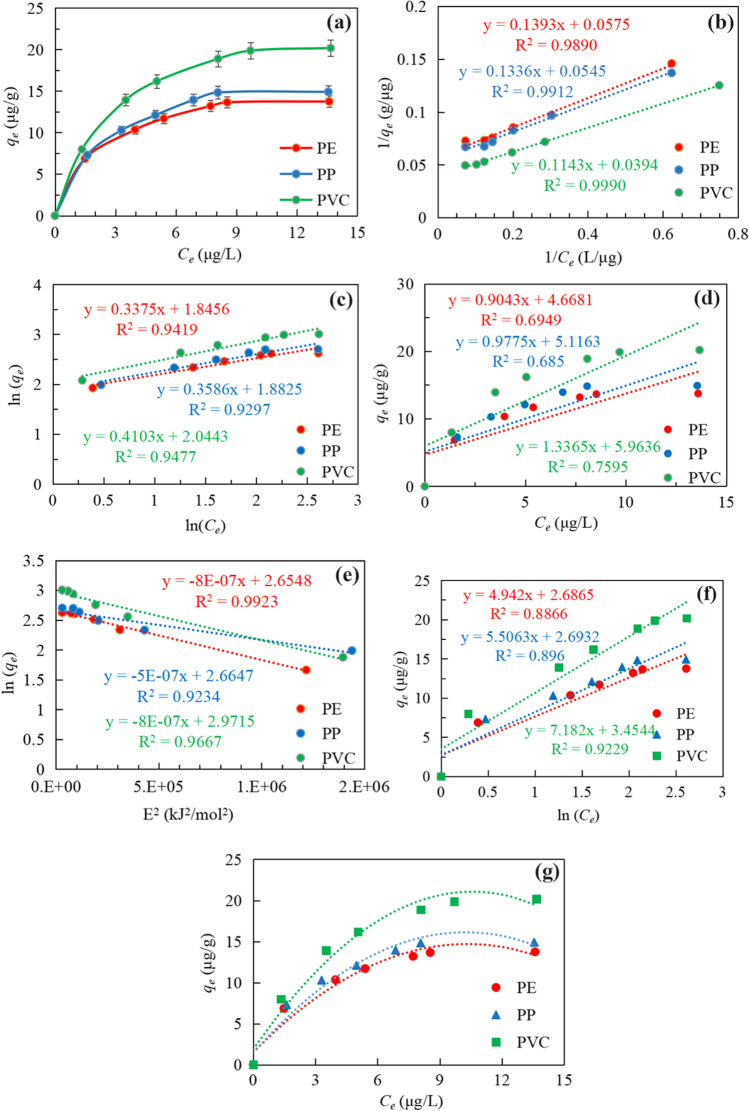

The fitting results of Langmuir, Freudlich, and linear isotherms are shown in Fig. 7 and Table 4. By comparing the R2 of these three models, Langmuir can better fit the process of BUT on MPs; the correlation coefficient R2 is PE (0.9890), PP (0.9912), and PVC (0.9990), respectively. This indicates that MPs have the main physical effect on BUT adsorption, and the adsorption process belongs to monolayer adsorption (Laouameur et al. 2021), while the Freundlich and linear models had poor fit for PE and PP, and relatively good fit for PVC. This is due to the formation of hydrogen bonds between the oxygen-containing functional groups on the PVC surface and water molecules, which reduces the availability of surface adsorption sites and makes it difficult to form multiple adsorption layers at the same location (Huffer et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2018b).

Fig. 7.

a Adsorption isotherm of PE, PP, and PVC on butachlor: b Langmuir, c Freundlich, d linear, e D-R, f Temkin, and g R-P.

Table 4.

Parameters for adsorption isotherm models.

| Samples | Langmuir | Freundlich | D-R | |||||||

| qm (μg/g) | KL (L/μg) | R2 | RL | KF (L/μg) | n | R2 | qm (μg/g) | β(mol2/J2) | R2 | |

| PE | 17.39 | 0.4128 | 0.9890 | 0.129-0.464 | 6.33 | 2.963 | 0.9419 | 14.22 | 8.25E-07 | 0.9923 |

| PP | 18.35 | 0.4079 | 0.9912 | 0.128-0.447 | 6.57 | 2.7886 | 0.9297 | 14.36 | 4.97E-07 | 0.9234 |

| PVC | 25.38 | 0.3447 | 0.9990 | 0.138-0.492 | 7.72 | 2.4372 | 0.9477 | 19.52 | 8.11E-07 | 0.9667 |

| Samples | R-P | Linear | Temkin | |||||||

| αR | β | KR | R2 | k | b | R2 | BT | KT | R2 | |

| PE | 0.47 | 1 | 7.70 | 0.9929 | 0.9043 | 4.6681 | 0.6949 | 4.94 | 1.7222 | 0.8866 |

| PP | 0.41 | 1 | 7.56 | 0.9894 | 0.9775 | 5.1163 | 0.6850 | 5.51 | 1.6309 | 0.8960 |

| PVC | 0.36 | 1 | 9.04 | 0.9971 | 1.3365 | 5.9636 | 0.7595 | 7.18 | 1.6177 | 0.9229 |

The linear model in Fig. 7(d) analyzed its adsorption principle by linearizing the adsorption isotherms (Foo and Hameed 2010). The adsorption isotherms of PVC tend to be relatively linear, while the adsorption isotherms of PE and PP are nonlinear. This difference is related to the properties of the polymer of the MPs itself (Dai et al. 2019). According to the glass transition temperature of polymers, polymers can be divided into highly elastic polymers and glassy polymers (Eidensticker et al. 2017). PE and PP are highly elastic polymers with methylene chains and their main adsorption mode was adsorption to the polymer itself rather than just to the surface. PVC was a glassy polymer at room temperature. The main adsorption mode of this polymer was surface adsorption (Liu and Dai 2021). As the mass concentration of BUT was increased, the adsorption sites on the MPs surface gradually decreased, which reduces the adsorption efficiency, thereby presenting a non-linear adsorption isotherm.

The KF, n, and R2 values of the three particles based on the Freundlich model are shown in Table 4. MPs have a larger KF value, indicating that MPs have a good adsorption capacity for BUT. The R2 value generated by the Freundlich linear equation is between 0.9297 and 0.9477, indicating that the Freundlich model can fit well with the experimentally measured value. Compared with the linear model, the Freundlich model is suitable for MPs (R2> 0.9000). The inhomogeneous multi-layer adsorption process led to the dispersibility of MPs sites and active functional groups (Foo and Hameed 2010). In this study, PVC has the lowest nf value, which indicates that PVC has stronger heterogeneity and a more uneven surface structure (Liu et al. 2021a). The nf value of PVC is significantly lower than its corresponding PE and PP, indicating that the surface of PVC will have certain wrinkles and cracks, which will increase its heterogeneity. At the same time, as the concentration of BUT in the solution increases, its adsorption tendency will decrease.

The carrier effect increases significantly with the increase of Ce, and in all cases, it gradually reaches the equilibrium phase of Fig. 7(a). As shown in Table 4, the KL value of MPs ranges between 0.3447 and 0.4128 L/μg, and the order of numerical value is consistent with the KF value of the Freundlich model and the Kd value of the linear model. The adsorption capacity of MPs for BUT from large to small is: PVC > PP > PE. The R2 value generated by the Langmuir equation is the largest (> 0.9990), which shows that among the three adsorption kinetic models, the Langmuir model is most suitable for describing the adsorption process of BUT on MPs. The E value is within the range of 8.0 kJ/mol and 16.0 kJ/mol indicating that the adsorption mechanism of MPs to BUT is mainly physical adsorption Fig. 7(e). The R2 of the three MPs fitted by the D-R model were PE (0.9923), PP (0.9234), and PVC (0.9667), respectively, indicating that the D-R model is suitable for describing the adsorption process of BUT on MPs. The R-P model is used to supplement the adsorption process. The R-P model represents that the adsorption equilibrium may be within a wide concentration range, and has the characteristics of the L. and F. models. The relationship between the adsorption process and the first two models can be determined through the calculation of parameters. By fitting the R2 of MPs, they were 0.9929, 0.9894, and 0.9971, respectively, which conforms to the R-P model. The value range of β is 0–1. By fitting the adsorption process of MPs and BUT, β=1, the adsorption of the three MPs under the R-P model can be summarized as the Langmuir monolayer adsorption process, which is consistent with the Langmuir fitting results. The fitting data of the Temkin model is poor. The R2 value of PE and PP is lower than 0.9000, but the fitting data of PVC is 0.9229, indicating that there is a certain difference in the adsorption of PVC, PE, and PP.

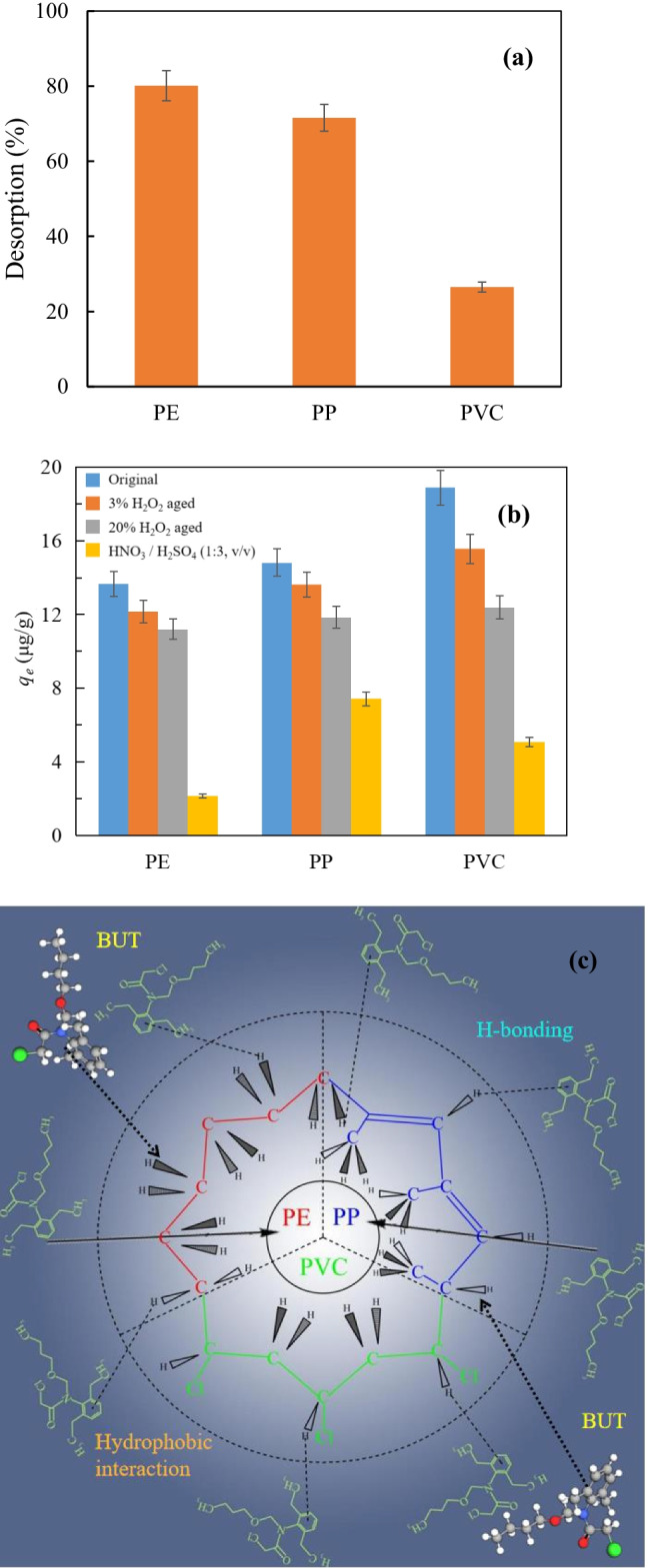

Desorption experiment

To study the desorption capacity of MPs, desorption experiments were performed with 0.20 M CaCl2. The influence trend is shown in Fig. 8(a). The desorption rate of PE was as high as 80.13%, followed by 71.60% of PP, and the lowest desorption rate of PVC was only 26.5%. A certain concentration of salt ions or certain salt ions cause salting out effect (Zhang et al. 2018a). The presence of Ca2+ in the solution will increase the diffusion rate of BUT in the inner pores of MPs, thereby increasing the desorption capacity and desorption rate of BUT by MPs. The desorption capacity of PVC is much lower than that of PE and PP, because the glassy amorphous form of PVC is more likely to agglomerate than the other two materials in the rubber state, depending on its lower diffusion coefficient (0.44 mm2/s) (Imhof et al. 2016). When the Ca2+ in the water body is present, it will cause a reunion of PVC. The interaction of particles with MPs and water impact and repulsion promote the desorption process (Dai et al. 2022).

Fig. 8.

a Desorption rate of butachlor with 0.2 mol/L CaCl2.; b loaded PE, PP, and PVC before and after aging; c the three possible main adsorption mechanisms of MPs (PE, PP, and PVC) to BUT.

Aging experiment

Experiments have found that the adsorption of MPs after aging is less than before aging (see Fig. 8(b)). The main reason is that in the aqueous solution, aging increases the oxygen-containing functional groups on MPs, which combine with hydrogen ions in the water to produce H2O, and produce a water film on the surface of MPs, which blocks the adsorption effect of MPs and BUT and reduces adsorption (Liu et al. 2021b). The site makes the adsorption capacity decrease, which is consistent with our experimental results. When using hydrogen peroxide for aging, the increase of H2O2 concentration caused the adsorption capacity after aging to decrease more, and the acid aging led to the highest decrease in adsorption capacity. Under acidic conditions, the adsorption capacity of PE, PP, and PVC decreased by up to 84.34%, 49.93%, and 73.10%, respectively. Oxidation by oxidants may cause oxidized substances to appear on the surface of MPs, and may also affect the hydrophobic properties of MPs and the carrier effect. As the concentration of H2O2 gradually increases, the decrease becomes more pronounced. H2O2 can also induce oxidation and reduction of hydroxyl radicals and caused loss of formal charge on O+ (Wang et al. 2020c). Acid aging belongs to the category of chemical oxidation, which dissolves and destroys the surface crystallinity of MPs. In addition, H2O2, concentrated sulfuric acid and concentrated nitric acid may over-oxidize MPs. The adsorption capacity of MPs was different under different aging conditions, and the order was original MPs > 3 % H2O2 aged MPs > 20 % H2O2 aged MPs > HNO3 / H2SO4 (1:3, v/v) mixed solution aged MPs.

Adsorption mechanism

This research examined the carrier effect of three typical microplastics with the herbicide BUT. In the aquatic environment, MPs can adsorb certain organic pollutants, carry them as carriers, and continue to migrate in the natural environment. Different MPs’ mechanisms of action are not the same. The adsorption capacity and mechanism of MPs for organic pollutants in other studies were shown in Table 5. Studies have found that the hydrophobicity of MPs and herbicides affects the interaction (Huffe and Hofmann 2016; Velzeboer et al. 2014). In addition, other forces may be created between the MPs and the herbicide (Huffer et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2018a). Similar studies found that a weak hydrogen bond of CH/π interaction was generated between a plastic polymer and a benzene ring-containing compound (Yamate et al. 2016). Both Langmuir and Freundlich models were suitable for fitting isothermal data of BUT adsorption onto MPs. The mechanism of BUT adsorption by MPs is shown in Fig. 8(c). The data showed that it was more in line with pseudo-secondary kinetics, indicating that physical adsorption and chemical adsorption exist, but as it turns out that physical adsorption was the main mechanism, and the adsorption of BUT by PE, PP, and PVC is mainly surface adsorption. The adsorption mode was surface adsorption, but there are various interactions between PVC and BUT; BUT can be adsorbed on its surface through hydrogen bonding interactions (Ferkous et al. 2022). In addition, BUT was a non-ionic pesticide, which was not easy to hydrolyze, so the electrostatic interaction between MPs and BUT was very weak. In strong alkaline condition, MPs such as PVC, PE, and PP were negatively charged; BUT was positively charged due to weak hydrolysis, usually removing the chlorine atom from the molecule, which generated electrostatic attraction with MPs, but it can be ignored compared with hydrophobic effect and hydrogen bond effect (Hartmann et al. 2017; Zheng and Ye 2001). Therefore, the equilibrium adsorption capacity of BUT on PVC in this study is higher than that of PE and PP. In addition, the crystallinity of MPs had a great impact on its adsorption of pollutants (Zhan et al. 2016). Therefore, the increase in the degree of crystallinity of MPs will reduce its adsorption of organics. From the XRD pattern, we can know that the crystallinity of the three materials is distinct. Generally, polymers with a crystallinity of more than 80 % were called crystalline plastics. Common crystalline plastics include PP and PE, and PVC was non-crystalline plastic (Liu et al. 2022a, b). This difference also led to different carrier effect of PE and PP, so the crystallinity of MPs also affected its adsorption of BUT (Gao et al. 2021). The results showed that the mutual binding capacity of three typical MPs (PE, PP, PVC) and BUT were 17.39 μg/g, 18.35 μg/g, and 25.38 μg/g, respectively. The ability of MPs to interact with BUT is only at the microgram level, and the ability to form larger contamination aggregates is relatively weak. However, the carrying capacity of small MPs for BUT does exist. In the natural cycle process, with the transfer of water, gas, solid, and other phases, there is a risk that MPs may carry BUT from one environment to another.

Table 5.

Adsorption mechanism of MPs on different adsorbates.

| MPs | Organic pollutants | Adsorption capacity (μg/g) | Equilibration time (h) | Isotherm | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP | CIP | 615 | 11.5 | L | Electrostatic attraction, hydrogen bounding, hydrophobic interaction, vander Waals force | Li et al. 2018 |

| TMP | 102 | 10 | F | Hydrogen bounding, hydrophobic interaction, vander Waals force | ||

| AMX | 294 | 14 | L | |||

| SMX | 6900 | 0.6 | F | Electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bounding | Guo et al. 2019 | |

| 3,6-BCZ | 402 | 13 | L and F | Chemical adsorption | Zhang et al. 2019 | |

| PE | CIP | 200 | 12.5 | L and F | Electrostatic attraction, hydrogen bounding, hydrophobic interaction, vander Waals force | Li et al. 2018 |

| TMP | 154 | 15 | F | Hydrogen bounding, hydrophobic interaction, vander Waals force | ||

| AMX | 131 | 14.5 | L and F | |||

| TC | 237.5 | - | L and F | Wang et al. 2020a | ||

| SMX | 660 | 2.5 | L and F | Electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bounding | Guo et al. 2019 | |

| PRP | >70 | 10 | Linear and F | Hydrophobic interactions and electrostatic effects | Razanajatovo et al. 2018 | |

| SER | >180 | 96 | Linear and F | |||

| PHEN | 927 | 10 | F | Partition and pore-filling | Wang et al. 2020b | |

| CAR | 4.44 | 1.5 | L and F | Hydrophobic interactions | Wu et al. 2019 | |

| DIP | 2.87 | 1.3 | F | |||

| DIF | 74.1 | 1.2 | L and F | |||

| MAL | 25.9 | 1.7 | L and F | |||

| DIFE | 273.2 | 0.8 | L and F | |||

| PVC | CIP | 453 | 13 | L and F | Electrostatic attraction, hydrogen bounding, hydrophobic interaction, vander Waals force | Li et al. 2018 |

| TMP | 481 | 14.7 | L and F | Hydrogen bounding, hydrophobic interaction, vander Waals force | ||

| AMX | 523 | 13.5 | L and F | |||

| SMX | 2800 | 2 | L and F | Electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bounding | Guo et al. 2019 | |

| BP | 787-1050 | 8.3-15 | L and F | Hydrophobic interactions, electrostatic forces, hydrogen, halogen bounds, and non-covalent bounds | Zuo et al. 2019 |

Langmuir (L) and Freundlich (F).

CIP, ciprofloxacin; TMP, trimethoprim; AMX, amoxicillin; SMX, sulfamethoxazole; 3,6-BCZ, 3,6-Dibromocarbazole; TC, tetracycline; PRP, propranolol; SER, sertraline; PHEN, phenanthrene; CAR, carbendazim; DIP, dipterex; DIF, diflubenzuron; MAL, malathion; DIFE, difenoconazole; BP, bisphenol analogues

Conclusions

In this work, the adsorption experiments and carrier mechanism of three typical MPs and herbicide BUT were studied. In the study of adsorption kinetics, MPs conform to pseudo-second-order kinetics, indicating that there are physical adsorption and chemical adsorption, but physical adsorption is the main mechanism. PVC shows mainly surface adsorption, while PE and PP show surface adsorption and external liquid film diffusion. The adsorption isotherm study shows that the Langmuir isotherm adsorption model has a better fitting effect, indicating that the adsorption of BUT by MPs is a single-layer adsorption. When pH <7.0, the adsorption is dominated by electrostatic interaction. Under alkaline conditions (when pH>7.0), adsorption is dominated by hydrophobic interaction. Low salt ion concentration can reduce the adsorption of BUT on MPs, but under high concentration conditions, the adsorption capacity will rebound and increase. In the desorption experiment, Ca2+ can increase the diffusion rate of BUT in the inner pores of MPs. In the aging experiment, the loading of MPs after 240 h was less than that before aging. The adsorption order of BUT on PE, PP, and PVC is: PVC > PP > PE. The crystallinity and the presence of oxygen-containing groups lead to an increase in the equilibrium adsorption capacity of PVC relative to PE and PP. The electrostatic interaction between MPs and BUT is very weak. In addition, compared with other studies, this research also clearly reveals the adsorption mechanism and the carrier effect between PE, PP, and PVC and BUT.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Miss Qinyi Xiong of Harbin Institute of Technology for her help during data collection and experimental setup.

Author contribution

Huating Jiang and Xin Chen: writing—original draft preparation; Dr. Yingjie Dai: writing—review, editing, and project administration.

Availability of data and materials

All data, materials, or models generated or used during the study appear in the submitted manuscript.

Declarations

Consent to participate and consent for publication

All the authors contributed to the research and revision of this article, and mutually agree that it should be submitted to ESPR.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

This manuscript has not been published elsewhere and is not under consideration by another journal.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abdullah AR, Bajet CM, Matin MA, Nhan DD, Sulaiman AH. Ecotoxicology of pesticides in the tropical paddy fifield ecosystem. Environ Toxicol Chem. 1997;16:59–70. doi: 10.1002/etc.5620160106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abigail M, Samuel S, Ramalingam C. Addressing the environmental impacts of butachlor and the available remediation strategies: a systematic review. Int J Environ Sci Technol. 2015;12:4025–4036. doi: 10.1007/s13762-015-0866-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amamra S, Djellouli B, Elkolli H, Benguerba Y, Erto A, Balsamo M, Ernst B, Benachour D. Synthesis and characterization of Layered Double Hydroxides aimed at encapsulation of sodium diclofenac: theoretical and experimental study. J Mol Liq. 2021;338:116677. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.116677. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold J. The influence of liquid uptake on environmental stress cracking of glassy polymers. Mat Sci Eng A-Struct. 1995;197:119–124. doi: 10.1016/0921-5093(94)09759-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bakir A, Rowland SJ, Thompson RC. Enhanced desorption of persistent organic pollutants from microplastics under simulated physiological conditions. Environ Pollut. 2014;185:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergaoui M, Khalfaoui M, Alam M, Guellou B, Belekbir MC, Chouk R, Erto A, Yadav KK, Benguerba Y. Preparation, characterization and dye adsorption properties of activated olive residue and their novel bio-composite beads: new computational interpretation. Mater Today Commun. 2022;30:103056. doi: 10.1016/j.mtcomm.2021.103056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann M, Collard F, Fabres J, Gabrielsen GW, Provencher JF, Rochman CM, Sebille EV, Tekman MB. Plastic pollution in the Arctic. Nat Rev Earth Environ. 2022;3:323–337. doi: 10.1038/s43017-022-00279-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borrelle SB, Ringma J, Law KL, Monnahan CC, Lebreton L, McGivern A, Murphy E, Jambeck J, Leonard GH, Hilleary MA, Eriksen M, Possingham HP, De Frond H, Gerber LR, Polidoro B, Tahir A, Bernard M, Mallos N, Barnes M, Rochman CM. Predicted growth in plastic waste exceeds efforts to mitigate plastic pollution. Science. 2020;369:1515–1518. doi: 10.1126/science.aba3656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chander S, Pandey J. Effect of herbicide and nitrogen on yield of scented rice (Oryza sativa) under different rice cultures. Indian J Agron. 1996;41:209–214. [Google Scholar]

- Chau N, Sebesvari Z, Amelung W, Renaud FG. Pesticide pollution of multiple drinking water sources in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam: evidence from two provinces. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2015;22:9042–9058. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-4034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Tan Z, Qi Y, Ouyang C. Sorption of tri-n-butyl phosphate and tris (2-chloroethyl) phosphate on polyethylene and polyvinyl chloride microplastics in seawater. Mar Pollut Bull. 2019;149:110490. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.110490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua EM, Shimeta J, Nugegoda D, Morrison PD, Clarke BO. Assimilation of polybrominated diphenyl ethers from microplastics by the Marine amphipod, Allorchestes compressa. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48:8127–8134. doi: 10.1021/es405717z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai YJ, Zhang KX, Meng XB, Li JJ, Guan XT, Sun QY, Sun Y, Wang WS, Lin M, Liu M, Yang SS, Chen YJ, Gao F, Zhang X, Liu ZH. New use for spent coffee ground as an adsorbent for tetracycline removal in water. Chemosphere. 2019;215:163–172. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.09.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y, Shi J, Zhang N, Pan Z, Xing C, Chen X. Current research trends on microplastics pollution and impacts on agro-ecosystems: a short review. Sep Sci Technol. 2022;57:656–669. doi: 10.1080/01496395.2021.1927094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De F, Sabatini V, Antenucci S, Gattoni G, Santo N, Bacchetta R, Ortenzi MA, Parolini M. Polystyrene microplastics ingestion induced behavioral effects to the cladoceran Daphnia magna. Chemosphere. 2019;231:423–431. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.05.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eidensticker S, Zarfl C, Cirpka OA, Fellenberg G, Grathwohl P. Shift in mass transfer of wastewater contaminants from microplastics in presence of dissolved substances. Environ Sci Technol. 2017;51:12254–12263. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b02664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferkous H, Rouibah K, Hammoudi NEH, Alam M, Djilani C, Delimi A, Laraba O, Yadav KK, Ahn HJ, Jeon BH, Benguerba Y. The removal of a textile dye from an aqueous solution using a biocomposite adsorbent. Polymers-basel. 2022;14:2396. doi: 10.3390/polym14122396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foo KY, Hameed BH. Insights into the modeling of adsorption isotherm systems. Chem Eng J. 2010;156:2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2009.09.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franzellitti S, Canesi L, Auguste M, Wathsala R, Fabbri E. Microplastic exposure and effects in aquatic organisms: a physiological perspective. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2019;68:37–51. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2019.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frias J, Sobral P, Ferreira A. Organic pollutants in microplastics from two beaches of the Portuguese coast. Mar Pollut Bull. 2010;60:1988–1992. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2010.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao F, Xu Z, Dai Y. Removal of tetracycline from wastewater using magnetic biochar: a comparative study of performance based on the preparation method. Environ Technol Innov. 2021;24:101916. doi: 10.1016/j.eti.2021.101916. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gogoi AK, Kalita H. Effect of fertilizer and butachlor on weeds and yield of transplanted rice (Oryza sativa) Indian J Agron. 1996;41:230–232. [Google Scholar]

- Gulmine J, Janissek P, Heise H, Akcelrud L. Polyethylene characterization by FTIR. Polym Test. 2002;21:557–563. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9418(01)00124-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Chen C, Wang J. Sorption of sulfamethoxazole onto six types of microplastics. Chemosphere. 2019;228:300–308. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.04.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann NB, Rist S, Bodin J, Jensen LH, Schmidt SN, Mayer P, Meibom A, Baun A. Microplastics as vectors for environmental contaminants: exploring sorption, desorption, and transfer to biota. Integr Environ Asses. 2017;13:488–493. doi: 10.1002/ieam.1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero-Hernández E, Andrades MS, Álvarez-Martín A, Pose-Juan E, Rodríguez-Cruz MS, Sánchez-Martín MJ. Occurrence of pesticides and some of their degradation products in waters in a Spanish wine region. J Hydrol. 2013;486:234–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2013.01.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hossein DA, David JL, Mika S. COVID-19, a double-edged sword for the environment: a review on the impacts of COVID-19 on the environment. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021;28:61969–61978. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-16551-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JQ, Yang SZ, Guo L, Xu X, Yao T, Xie F. Microscopic investigation on the adsorption of lubrication oil on microplastics. J Mol Liq. 2017;227:351–355. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2016.12.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huffe T, Hofmann T. Sorption of non-polar organic compounds by micro-sized plastic particles in aqueous solution. Environ Pollut. 2016;214:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffer T, Weniger AK, Hofmann A. Sorption of organic compounds by aged polystyrene microplastic particles. Environ Pollut. 2018;236:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imhof H, Laforsch C, Wiesheu AC, Schmid J, Anger PM, Niessner R, Lvleva NP. Pigments and plastic in limneticecosystems: a qualitative and quantitative study on microparticles of different size classes. Water Res. 2016;98:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isobe A, Uchida K, Tokai T, Iwasaki S. East Asian seas: a hot spot of pelagic microplastics. Mar Pollut Bull. 2015;101:618–623. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2015.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y, Zhao J, Yu X, Chen C, Ying G. Research progress on the effect of microplastics on the bioaccumulation of hydrophobic organic pollutants. Asian J Ecotoxicol. 2019;14:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Chen H, Liao Y, Ye Z, Li M, Klobučar G. Ecotoxicity and genotoxicity of polystyrene microplastics on higher plant Vicia faba. Environ Pollut. 2019;250:831–838. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Xiong Q, Chen X, Pan W, Dai Y. Carrier effect of S-metolachlor by microplastics and environmental risk assessment. J Water Process Eng. 2021;44:102451. doi: 10.1016/j.jwpe.2021.102451. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jolodar NR, Karimi S, Bouteh E, Balist J, Prosser R. Human health and ecological risk assessment of pesticides from rice production in the Babol Roud River in Northern Iran. Sci Total Environ. 2021;772:144729. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur R, Goyal D, Agnihotri S. Chitosan/PVA silver nanocomposite for butachlor removal: Fabrication, characterization, adsorption mechanism and isotherms. Carbohydr Polym. 2021;262:117906. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.117906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laouameur K, Flilissa A, Erto A, Balsamo M, Ernst B, Dotto G, Benguerba Y. Clorazepate removal from aqueous solution by adsorption onto maghnite: Experimental and theoretical analysis. J Mol Liq. 2021;328:115430. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.115430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li K, Ma D, Wu J, Chai C, Shi Y. Distribution of phthalate esters in agricultural soil with plastic film mulching in Shandong Peninsula, East China. Chemosphere. 2016;164:314–321. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.08.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Zhang K, Zhang H. Adsorption of antibiotics on microplastics. Environ Pollut. 2018;237:460–467. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Dai YJ. Strong adsorption of metolachlor by biochar prepared from walnut shells in water. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021;28:48379–48391. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-14117-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Zhu Z, Yang Y, Sun Y, Yu F, Ma J. Sorption behavior and mechanism of hydrophilic organic chemicals to virgin and aged microplastics in freshwater and seawater. Environ Pollut. 2019;246:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.11.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Fang W, Yuan M, Li X, Wang X, Dai Y. Metolachlor-adsorption on the walnut shell biochar modified by the fulvic acid and citric acid in water. J Environ Chem Eng. 2021;9:106238. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2021.106238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Yuan M, Wang X, Li X, Fang W, Shan D, Dai YJ. Biochar aging: properties, mechanisms, and environmental benefits for adsorption of metolachlor in soil. Environ Technol Innov. 2021;24:101841. doi: 10.1016/j.eti.2021.101841. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Li X, Wang X, Wang Y, Shao Z, Liu X, Shan D, Liu Z, Dai YJ. Metolachlor adsorption using walnut shell biochar modified by soil minerals. Environ Pollut. 2022;308:119610. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2022.119610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Wang X, Fang W, Li X, Shan D, Dai Y. Adsorption of metolachlor by a novel magnetic illite–biochar and recovery from soil. Environ Res. 2022;204:111919. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Huang A, Cao S, Sun F, Wang L, Guo H, Ji R. Effects of nanoplastics and microplastics on toxicity, bioaccumulation and environmental fate of phenanthrene in fresh water. Environ Pollut. 2016;219:166–173. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod M, Arp HPH, Tekman MB, Jahnke A. The global threat from plastic pollution. Science. 2021;373:61–65. doi: 10.1126/science.abg5433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mane VS, Mall ID, Srivastava VC. Kinetic and equilibrium isotherm studies for the adsorptive removal of Brilliant Green dye from aqueous solution by rice husk ash. J Environ Manag. 2007;84:390–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty RS, Bharati K, Moorthy SBT, Ramakrishnan B, Rao RV, Sethunathan N. Effect of the herbicide butachlor on methane emission and ebullition flux from a direct-seeded flooded rice field. Biol Fertil Soils. 2001;33:175–180. doi: 10.1007/s003740000301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nizzetto L, Bussi G, Futter MN, Butterfield D, Whitehead PG. A theoretical assessment of microplastic transport in river catchments and their retention by soils and river sediments. Environ Sci Process Impacts. 2016;18:1050–1059. doi: 10.1039/C6EM00206D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S, Wang Q, Shin WS, Song DI. Effect of salting out on the desorptionresistance of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in coastal sediment. Chem Eng J. 2013;225:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2013.03.069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paula ST, Vladimír K, Susana L, Cornelis AM, Van G. Partitioning of chemical contaminants to microplastics: Sorption mechanisms, environmental distribution and effects on toxicity and bioaccumulation. Environ Pollut. 2019;252:1246–1256. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plastic Europe (2020) Plastics - the Facts 2020 (An analysis of European plastics production, demand and waste data). https://plasticseurope.org/knowledge-hub/plastics-the-facts-2020/. Accessed 16 Sept 2020

- Razanajatovo RM, Ding J, Zhang S, Jiang H, Zou H. Sorption and desorption of selected pharmaceuticals by polyethylene microplastics. Mar Pollut Bull. 2018;136:516–523. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rillig MC. Microplastic in terrestrial ecosystems and the soil? Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46:6453–6454. doi: 10.1021/es302011r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochman CM, Hoh E, Hentschel BT, Kaye S. Long-term field measurement of sorption of organic contaminants to five types of plastic pellets: implications for plastic marine debris. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47:1646–1654. doi: 10.1021/es303700s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seblework M, Roba A, Aklilu S, Michael H, David S, Argaw A, Pieter S. Pesticide residues in drinking water and associated risk to consumers in Ethiopia. Chemosphere. 2016;162:252–260. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.07.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidensticker S, Zarfl C, Cirpka OA, Fellenberg G, Grathwohl P. Shift in mass transfer of wastewater contaminants from microplastics in presence of dissolvedsubstances. Environ Sci Technol. 2017;51:12254–12263. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b02664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen M, Zeng Z, Song B, Yi H, Hu T, Zhang Y, Zeng G, Xiao R. Neglected microplastics pollution in global COVID-19: disposable surgical masks. Sci Total Environ. 2021;790:148130. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Jiang F, Li J, Zheng L. Research progress on source, distribution and ecological environmental impact of marine microplastics. Adv Mar Sci. 2016;34:449–461. [Google Scholar]

- The World Health Organization (2020) Shortage of personal protective equipment endangering health workers worldwide. https://www.who.int/news/item/03-03-2020-shortage-of-personal-protective-equipment-endangering-health-workers-worldwide. Accessed 13 Dec 2020

- Toan PV, Sebesvari Z, Bläsing M, Rosendahl I, Renaud FG. Pesticide management and their residues in sediments and surface and drinking water in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Sci Total Environ. 2013;452:28–39. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velzeboer I, Kwadijk CJ, Koelmans AA. Strong sorption of PCBs to nanoplastics, microplastics, carbon nanotubes and fullerenes. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48:4869–4876. doi: 10.1021/es405721v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Wang J. Comparative evaluation of sorption kinetics and isotherms of pyrene onto microplastics. Chemosphere. 2018;193:567–573. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.11.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Shih KM, Li XY. The partition behavior of perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanesulfonamide (FOSA) on microplastics. Chemosphere. 2015;119:841–847. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Lv S, Zhang M, Chen G, Zhu T, Zhang S, Teng Y, Christie P, Luo YM. Effects of plastic film residues on occurrence of phthalates and microbial activity in soils. Chemosphere. 2016;151:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.02.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LW, David OC, Jorg R, Yong SO, Daniel CWT, Shen ZT. Biochar aging: mechanisms, physicochemical changes, assessment, and implications for field applications. Environ Sci Technol. 2020;54:14797–14814. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c04033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Yu C, Chu Q, Wang F, Lan T, Wang J. Adsorption behavior and mechanism of five pesticides on microplastics from agricultural polyethylene films. Chemosphere. 2020;224:125491. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wang X, Li Y, Li J, Wang F, Xia S, Zhao J. Biofilm alters tetracycline and copper adsorption behaviors onto polyethylene microplastics. Chem Eng J. 2020;392:123808. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2019.123808. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Cai Z, Jin H, Tang Y. Adsorption mechanisms of five bisphenol analogues on PVC microplastics. Sci Total Environ. 2019;650:671–678. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamate T, Kumazawa K, Suzuki H, Akazome M. CH/π interactions for macroscopic interfacial adhesion design. ACS Macro Lett. 2016;5:858–861. doi: 10.1021/acsmacrolett.6b00265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakrajšek N. Influence of inorganic salts on the adsorption of cationically modified starch to fibers. Food Nutr Sci. 2014;5:245–249. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan ZW, Wang JD, Peng JP, Xie QL, Huang Y, Gao YF. Sorption of 3,3',4,4'- tetrachlorobiphenyl by microplastics: a case study of polypropylene. Mar Pollut Bull. 2016;110:559–563. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Wang J, Zhou B, Zhou Y, Dai Z, Zhou Q, Chriestie P, Luo YM. Enhanced adsorption of oxytetracycline to weathered microplastic polystyrene: kinetics, isotherms and influencing factors. Environ Pollut. 2018;243:1550–1557. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.09.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Zheng M, Wang L, Lou Y, Shi L, Jiang S. Sorption of three synthetic musks by microplastics. Mar Pollut Bull. 2018;126:606–609. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Zheng M, Yin X, Wang L, Lou Y, Qu L, Liu X, Zhu H, Qiu Y. Sorption of 3,6-dibromocarbazole and 1,3,6,8-tetrabromocarbazole by microplastics. Mar Pollut Bull. 2019;138:458–463. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Chen H, He H, Cheng H, Ma T, Hu J, Yang S, Li S, Zhang L. Adsorption behavior and mechanism of 9-Nitroanthracene on typical microplastics in aqueous solutions. Chemosphere. 2020;245:125628. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Dai Y. Tetracycline adsorption mechanisms by NaOH-modified biochar derived from waste Auricularia auricula dregs. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2022;29:9142–9152. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-16329-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H, Ye C. Photodegradation of acetochlor and butachlor in waters containing humic acid and inorganic ion. B Environ Contam Tox. 2001;67:601–608. doi: 10.1007/s001280166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo L, Li H, Lin L, Sun Y, Diao Z, Liu S, Zhang Z, Xu X. Sorption and desorption of phenanthrene on biodegradable poly (butylene adipate co-terephtalate) microplastics. Chemosphere. 2019;215:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.09.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data, materials, or models generated or used during the study appear in the submitted manuscript.