Abstract

Protein–protein interactions (PPIs) and protein–metabolite interactions play a key role in many biochemical processes, yet they are often viewed as being independent. However, the fact that small molecule drugs have been successful in inhibiting PPIs suggests a deeper relationship between protein pockets that bind small molecules and PPIs. We demonstrate that 2/3 of PPI interfaces, including antibody–epitope interfaces, contain at least one significant small molecule ligand binding pocket. In a representative library of 50 distinct protein–protein interactions involving hundreds of mutations, >75% of hot spot residues overlap with small molecule ligand binding pockets. Hence, ligand binding pockets play an essential role in PPIs. In representative cases, evolutionary unrelated monomers that are involved in different multimeric interactions yet share the same pocket are predicted to bind the same metabolites/drugs; these results are confirmed by examples in the PDB. Thus, the binding of a metabolite can shift the equilibrium between monomers and multimers. This implicit coupling of PPI equilibria, termed “metabolic entanglement”, was successfully employed to suggest novel functional relationships among protein multimers that do not directly interact. Thus, the current work provides an approach to unify metabolomics and protein interactomics.

Introduction

One of the essential features of living systems is that their biochemical processes are the consequence of and are controlled by a plethora of intermolecular interactions.1 Salient among these are protein–protein interactions (PPIs)2 and protein–metabolite interactions.3 Despite the recognition that such interactions are essential in the regulation of cellular processes, they are often implicitly treated as being independent. This dichotomy was reflected in the long held belief that small molecule drugs or peptides could not inhibit PPIs.4 The logic was that most protein–protein interfaces are rather flat and have a relatively large surface area. This view assumed the absence of ligand binding pockets that could provide the requisite binding free energy to compete with the PPI.4 One partial solution to this problem was the recognition that PPIs are not uniform across the protein–protein interface; rather, there are hot spots.5−9 Hot spots are sets of residues in the PPI that disproportionally contribute to the binding free energy. These make perfect sites to target by an inhibitor which could be small molecule ligands,10,11 peptides,12 antibodies,13 or covalent inhibitors.4 For the first three inhibitor classes, the hot spot in the protein interface must be capable of binding the ligand so that it can compete with the interprotein interaction. Covalent inhibitors must bind and react specifically to avoid the issue of randomly cross-linking a plethora of macromolecules in the cell. As many small molecule protein–protein interaction inhibitors have been developed and a number have entered the clinic,4 studying the relationships of small molecule ligand binding sites and protein–protein interfaces and their consequences on biochemical processes could provide new classes of drugs and possibly deeper biological insights.

In addition to the successful design of small molecule inhibitors of PPIs, is there other evidence for the direct interrelationship of PPIs and small molecule binding pockets? Previously, Gao and Skolnick demonstrated that when two proteins interact, they form a ligand binding pocket immediately adjacent to the protein–protein interface which is absent when the two proteins are pulled apart.14 Thus, protein–protein binding acts as a binary switch to modulate small molecule–protein interactions. Interestingly, after mutations in residues associated with enzymatic function, these interface adjacent ligand binding sites are the second most important location of disease associated amino acid mutations in humans.15

As indicated above, it was often believed that the protein–protein interface is a “special” region where proteins interact.16 This idea underlies attempts to predict the location on a protein’s surface where proteins interact; we term such regions in a given protein a “half-interface”.17,18 However, what such approaches fail to realize is that >70% of a given protein’s surface is capable of interacting with another protein.16 That is, there is nothing truly exceptional about protein half-interfaces. Given that an average protein has 3–5 pockets that are capable of interacting with small molecular ligands, small molecule ligand binding sites and protein half-interfaces likely overlap. While it has been anecdotally recognized that protein hot spots can involve a ligand binding site or involve the protrusion of the partner’s residues into such a site,19 to the best of our knowledge, there has been no systematic study of the overlap of small molecule ligand binding pockets with protein half-interfaces. It is the goal of this work to explore this issue. If it turns out that ligand binding sites are frequently present in protein half-interfaces, the possible implications of this result for small molecule PPI inhibitor discovery and the possible synergistic role between cellular metabolism and the regulation of protein–protein interactions will be explored. If a set of PPIs share a common small molecule binding site, binding metabolites could disrupt these protein–protein interactions in the same way that small molecule inhibitors disrupt PPIs. Depending on the relative binding free energy of the metabolite to a given protein, the release of the metabolite from one protein complex could disrupt interactions in another protein complex. Thus, it could couple interactions between protein complexes that never physically interact. Such regulation might be beneficial or deleterious depending on which PPIs are disrupted or enhanced. We term this effect “metabolic entanglement”.

To establish the plausibility of these ideas, the first question that must be addressed is the number of stereochemically distinct protein–protein interfaces and protein pockets. As shown in previous work, the library of stereochemically distinct interfaces is essentially complete; indeed, there are about 1,000 of them.20 Similarly, there are fewer than 500 stereochemically distinct ligand binding pockets.19,21,22 Considering a representative set of PDB structures clustered at the level of 65% sequence identity, in the current PDB there are 234 (328) stereochemically distinct pockets with at least 5 members in the representative pocket’s cluster when clustered at a p-value of 0.01 (0.005) using the pocket alignment algorithm Apoc.23 These 234 (328) pockets cover 93% (84%) of all pockets. What should be recognized is that in the PDB a given pocket often contains more than one ligand (typically located at the bottom of the pocket, as this is the region of maximal protein–ligand interaction) that interact with each other and the protein pocket; we term these ligands “COLIGs”.24

For the same representative ligand library, 536 (694) subpockets cover all ligand binding pockets (defined by the set of protein pocket residues in contact with a ligand) with at least 5 examples in the representative pocket’s cluster when clustered at a p-value of 0.01 (0.005) using Apoc.23 These 536 (694) subpocket pockets cover 88% (78%) of all ligand binding subpockets at a p-value of 0.01 (0.005). Given the remarkably small set of ligand binding pockets and the fact that the number of distinct protein–protein interfaces is itself very small, it would not be surprising to find that similar ligand binding pockets occur in evolutionarily unrelated as well as evolutionarily related protein half-interfaces.

If protein hot spots and small molecule ligand binding pockets were found to often coincide, then virtual ligand screening (VLS) algorithms can be used to help prioritize repurposed drugs as protein–protein interaction inhibitors as well as to help identify metabolites that might create unexpected connections between different cellular proteins that are modulated by their PPIs. There are four broad categories of VLS designed to identify such interactions: (1) high-resolution structure-based docking,25−28 (2) ligand-based QSAR,29−31 (3) convolutional neural network (CNN) or deep CNN technology,32,33 and (4) pocket-similarity-based methods which may be machine-learning-based.34−42 High-resolution structure-based approaches are physics-based and can discover novel binders. However, they require high-resolution structures (performance drops dramatically with low-resolution models43) that currently cover around 1/3 of all human proteins (perhaps increasing to 2/3 of the human proteome if AlphaFold 2 models44 could be used). In addition, they are computationally expensive and have lower accuracy than ligand-based methods.42 QSAR methods require the presence of a known binder to identify related small molecule ligands. CNN methods also require high-resolution protein structures and docked ligands. They have issues with the small databases used for training and testing CNNs which have led to memorization artifacts. Our FINDSITEcomb2.045 approach takes advantage of predicted, low-resolution structures and information from ligands that bind distantly related proteins whose binding sites are similar to the target protein. More recently, using a boosted tree regression machine learning framework, in FRAGSITE,46 we extended FINDSITEcomb2.0 by integrating ligand fragment scores that exploit the observation that ligand fragments, e.g., rings, tend to interact with stereochemically conserved protein subpockets that also occur in evolutionarily unrelated proteins. These two knowledge-based approaches are complementary and perform at the state-of-the-art.46

Having the necessary background in hand, an overview of this paper is as follows: For a representative library of homo- and heterodimers, we examine the extent of overlap of small molecule ligand binding pockets and residues involved in the protein–protein half-interfaces. We examine what fraction of half-interfaces contain a protein pocket, how often the pair of pockets in the protein–protein interface overlap, and how many interact with a complementary convex surface that is not a pocket in the partner protein. We characterize the distribution of the fractions of half-interface residues that are in a protein pocket. We then examine whether protein pockets are found in antibody–epitope interfaces. Next, for 1341 mutants involving PPIs in 50 proteins,9 the correlation of hot spots and ligand binding pockets is examined as a function of the PPI binding free energy change. We further explore whether protein–protein interactions might be modulated by metabolites that bind to pockets in one of the protein partners and whether similar pockets in structurally distinct proteins can be employed to infer functional relationships based on the inferred binding of the metabolite. Finally, the results are summarized, and the implications for the generation of PPI inhibitors and the interplay of metabolomics and protein interactomics are discussed.

Methods

Preparation of Homo- and Heterodimer Libraries

The reference protein structure library that forms the input for the subsequent analysis is the September 2021 version of the Protein Data Bank.47 To be considered, each protein in a given multimeric structure must be between 41 and 800 residues in length. A pair of proteins that interact in a multimer are considered to be homodimers if their sequence identity is greater than 90%. There are a total of 44,796 pairs of homodimer proteins (see Supporting Information, LIST.homo_interface). When clustered at a 60% sequence identity threshold, there are 14,144 pairs (see Supporting Information, LIST.homo_interface.60), and at a 40% sequence identity threshold, there are 9,866 pairs (see Supporting Information, LIST.homo_interface.40). For homomultimers, all distinct interfacial interactions are considered. Thus, a given monomer can have more than one partner.

An interface is assigned to the heteromer set if the pairwise sequence identity of the respective interacting pair of proteins is ≤40%. From the PDB, we extracted a library of 22,886 distinct proteins (see Supporting Information, LIST.het_interface). When clustered at a 60% sequence identity threshold, there are 3,380 pairs of interacting proteins (see Supporting Information, LIST.het_interface.60), and at a 40% sequence identity threshold, there are 2,401 pairs (see Supporting Information, LIST.het_interface.40).

Preparation of Interface Contact Maps and Identification of the Ligand Binding Pockets in Each Protein Interface

For each of the respective libraries (see Supporting Information, LIST.homo_interface and LIST.hetero_interface), a pair of residues are assigned to be in contact if the distance between any pair of heavy atoms in the residues ≤4.5 Å. To be considered as a candidate interface, each protein half-interface must have >5 residues with interprotein contacts.

Pockets are assigned using the CAVITATOR pocket detection algorithm.23 This algorithm is insensitive to minor structural distortions. Moreover, almost every small molecule ligand found in a PDB structure is in a pocket identified using CAVITATOR. For the set of PDB structures clustered at 65% sequence identity for all its bound ligands including metal atoms, ions, and small molecule ligands, the list of 12,999 ligands assigned to pockets and the associated pocket is found in Supporting Information, LIST.ligands_assigned. After eliminating ligands routinely used to crystallize proteins, 327 ligands are not associated with pockets (see Supporting Information, LIST.nopocketligand). Given that CAVITATOR correctly identifies pockets that bind ligands in 97.5% of cases, we are fairly confident that it can be used to assign candidate small molecule ligand binding pockets in protein–protein interfaces. To coincide with a half-interface, the pocket must overlap with >5 residues and have a volume ≥500 Å3 so that it can bind a drug-like small molecule.

Analysis of Antibody–Epitope Interface Contact Maps and Identification of Interfacial Ligand Binding Pockets

A representative set of 3,399 antibody–protein PDB complexes were selected and analyzed as above for heavy and light chain antibody contacts (see Supporting Information, LIST.antibodies). CAVITATOR was used to identify ligand binding pockets. Again, to be considered part of a half-interface, the pocket must overlap the half-interface with >5 residues and have a volume ≥500 Å3. We considered the antibody interface to include both light and heavy chains as a single composite unit.

Analysis of the Relationship of Hot Spot Residues and Small Molecule Ligand Binding Sites

The data from the training set of the PIIMS Server which contains 1,341 mutations involving 50 distinct protein–protein interactions in their Table S2 were analyzed.9 The data were clustered into those residues whose binding free energy change, ΔG, was <1 kcal/mol (see LIST.deltaG_cold.res.unique), ≥1 kcal/mol and <2 kcal/mol (see LIST.deltaG1.res.unique), and >2 kcal/mol (see LIST.deltaG2.res.unique). Within a given range of ΔG, a given examined hot spot residue, e.g., residue “67”, only appears once in the analysis even though there may have been multiple mutations at residue “67” whose effect on the PPI’s ΔG was experimentally reported. We then applied CAVITATOR to determine whether the hot spots are in ligand binding pockets, are in an interface complementary to a possible ligand binding pocket, or are not involved with a ligand binding pocket.

Identification of Metabolites That Bind Within and Adjacent to Protein–Protein Interfaces

We scanned the entire PDB library for small molecule ligands and then determined the set of ligands that are human metabolites in the Human Metabolome Database48 (see Supporting Information, LIST.metabolites). We found 74,365 protein structures containing 4,148 unique metabolites (see Supporting Information, LIST.metabolites_unique). For subsequent analysis, we then extracted the entire set of PDB files between 41 and 800 residues in length that are associated with human proteins (see Supporting Information, LIST.pdb_chain.800.1.human). There are 74,259 such proteins.

Identification of Interfacial Binding Metabolite Ligands

Metabolites are assigned to interact with a protein residue if a pair of heavy atoms in the metabolite and amino acid residue are within 4.5 Å from each other. To examine if a given metabolite is likely to interact with a residue in the protein half-interface, we performed the following analysis: For each human monomer in the heteromeric library (see Supporting Information, LIST.pkt_interface_AB_AB.gt5 which contains 27,394 multimers) between 41 and 800 residues in length, we identified residues in the half-interface. We then aligned each target monomer to the entire PDB library (see Supporting Information, LIST.pdb_chains.800.1) of 228,949 template monomers. This library was then filtered for interacting metabolites. The minimum pairwise sequence identity between the target and template monomers must be 50%, and the volume of the target pocket must be >500 Å3 so that it can bind a reasonably sized metabolite. Each ligand binding residue must align to an interfacial target residue. For a ligand to be considered as binding in a protein half-interface, it must bind to a minimum of 4 half-interface residues (this is the same threshold that has been successfully used in pocket-similarity-based virtual ligand screening46). In practice, we find 16,186 heteromultimers (see Supporting Information, LIST.multimers_metabolites) involving 1,561 unique target multimers (see LIST.multimers_metabolites_names.pdb.unique). Of these, there are 1,260 human protein–metabolite pairs (see LIST.multimers_metabolites_human), a subset of which will be examined below.

Identification of Metabolites That Bind Adjacent to the Protein–Protein Interface

In addition to possibly disrupting a PPI by binding directly with the half-interface, metabolites (or small molecule ligands in general) can bind adjacent to the PPI in the pocket formed by the binding of two (or more) proteins; we term these interface adjacent ligands. Previously, an interface adjacent ligand was identified if any of its heavy atoms was within 6 Å of the PPI.14 Here, we adopt a more rigorous definition. An interface adjacent ligand must be within 4.5 Å of an interfacial residue in both proteins and also be in contact with noninterfacial residues in both of the proteins that create the interface. We scanned the library of multimer proteins (Supporting Information, LIST.pkt_interface_ab_ab.gt5) for metabolites that satisfy these criteria. The full list can be found in the Supporting Information (LIST.pkt_interface_ab_ab.gt5.b_adj). There are 3,392 cases in our PDB library, with 744 human examples (Supporting Information, LIST.multimers_metabolites_human.adj).

Analysis of a Representative Set of Pockets in Human Multimeric Proteins

Structural alignments using Apoc23 of small molecule ligand binding pockets in the PPI interface on a representative set of 1,424 human protein heteromers found in the PDB, each chain of which is >40 residues in length, were performed (see Supporting Information, LIST.human_apoc_molecule.2). We then selected a representative set of 10 pairs of monomers in distinct multimers whose pockets have a p-value ≤0.05 that contain at a minimum 3 identical residues in the pocket structural alignment. To ensure that such similar ligand binding pockets are not in evolutionarily related proteins and have structurally distinct folds, we further required that the TM-score49 of the respective monomers be <0.4.50 We then manually examined the resulting output of pairs of monomers having similar pockets in different multimers and searched the literature for confirmatory evidence that the pair of proteins occur in related cellular processes. This is of course circumstantial evidence that the pair of proteins possibly bind the same metabolite. Nevertheless, it can be viewed as a hypothesis generator of how the binding of a given metabolite (or set of metabolites) not only might act to regulate a given PPI but also could couple different cellular processes even though the two (or more) pairs of proteins do not directly interact. Rather, by interfering with the formation of PPIs, the binding of the same metabolite couples different molecules and their associated pathways.

To identify possible metabolites that bind, using FINDSITEcomb2.045 and FRAGSITE,46 we performed virtual ligand screening of the 10 pairs of proteins on the library of human metabolites HMDB (up to June 10, 2022)48 and DrugBank (v5.09)51 drugs for possible repurposing. The full set of VLS results are found in Supporting Information, on spreadsheets labeled “findsitecomb2_drug”, “findsitecomb2_hmdb”, “fragsite_drug”, and “fragsite_hmdb”.

Results

Examination of Whether Protein–Protein Interfaces Contain Small Molecule Ligand Binding Pockets

As schematically shown in Figure 1, one might imagine that proteins interact in a variety of ways: Panel A depicts the traditional intuitive view that the pair of proteins interact via two flat surfaces. Such a case might occur when a linear peptide binds to an MHC class I protein.12,52 Panels B and C are cases when at least one-half-interface contains a ligand binding pocket. In panel B, a single pocket interacts with a convex surface in the other half-interface, while in panel C, the pocket in each half-interface interacts with a convex surface on the other protein’s half-interface or the two interfaces interact like clasping hands that constitute the two pockets.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of how a pair of proteins might engage in a protein–protein interaction. (A) The proteins interact via a flat surface. (B) A single pocket interacts with the other protein’s convex surface. (C) The pocket in each half-interface interacts with a convex surface on the other protein’s half-interface, or the two interfaces interact like clasping hands and involve interacting pockets in both proteins.

As indicated above, the fact that small molecule drugs can bind to the interface and inhibit PPIs suggests that ligand bound pockets are indeed found in interfaces.53 However, the question remains as to how often the two pocket-based modes of interprotein interaction actually occur when a large and representative set of PPIs are considered.

In the case of homodimers, the pair of proteins could (approximately) interact in a head-to-head or head-to-tail configuration. In a head-to-head configuration, if a ligand binding pocket is present in one of the two interfaces, then by symmetry a pair of pockets (one in each half-interface) must perforce interact. Conversely, in a head-to-tail configuration, the pocket might still interact with a different pocket in or with a convex surface on the partner protein. We considered a set of homomeric proteins clustered at various sequence identity thresholds. The results are shown in Table 1. For interacting homo-half-interfaces, roughly 56% involve contacting pockets in both half-interfaces, viz., case C. About 14% involve just a single contacting pocket with a convex surface, case B. About 29% of interacting half-interfaces do not include at least 6 pocket residues located in a sufficiently large pocket that it could bind a small molecule ligand, i.e., case A. The results are essentially independent of sequence identity.

Table 1. Analysis of Coincidence of Pockets and Interfaces in Hetero- and Homomultimersa.

| max sequence identity | no. of interfaces | % of interfaces with at least 5 contacting residues in both pockets | % of interfaces with a pocket in a half-interface with at least 5 contacting with a nonpocket region of the other half-interface | # of interacting pairs with no significant size pockets in their interface |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homomultimeric Interfaces | ||||

| 40% | 9,866 | 56.1% | 14.1% | 29.8% |

| 60% | 14,114 | 56.8% | 14.4% | 28.8% |

| 100% | 44,796 | 58.1% | 14.2% | 27.7% |

| Heteromultimeric Interfaces | ||||

| 40% | 2,401 | 49.0% | 19.2% | 31.8% |

| 60% | 3,380 | 48.6% | 19.9 | 31.5% |

| 100% | 22,286 | 50.9% | 19.2 | 29.9% |

Each pocket must have a minimum volume of 500 Å3 so that it could potentially bind a small molecule ligand; in addition, a minimum of 6 of its residues must interact with the corresponding half-interface.

Turning to heteromultimers, the number of interfaces containing a pair of interacting pockets now decreases slightly to about 50%, while the number of single pocket interfacial interfaces increases to 19%. Thus, there are about 5% more single pocket than multipocket interfacial interactions in heteromers. Finally, the number of nonpocket interactions has slightly increased to about 31%. Note that for both homo- and heterointerfaces, if small pockets are allowed, all PPIs involve either these pockets or pockets with a small number of residues. However, in this case the (sub)pockets are too small to bind a small molecule drug or metabolite.

For case C, we next examined how the interfaces interact. In homodimers, clustered at 40% sequence identity, 30% of multipocket interfaces are of the hand clasping type; for heterodimers, this fraction is about 39%. For the full library, 54% of homodimeric interfaces and 51% of heterodimeric interfaces are of the hand clasping type. Thus, both modes of interaction are important.

This analysis did not consider what fraction of a given interface overlaps with a protein pocket. Does most of the interface involve the concave surface of a pocket (a portion of which can readily bind one or more molecules24) or not? This issue is explored in Figure 2. For both hetero- and homo-half-interfaces, Figure 2A considers the situation schematically depicted in Figure 1C, where each interacting half-interface contains pockets. Systematically and independent of the sequence identity threshold, homointerfaces containing two pockets interact with a higher on average pocket surface area than heterointerfaces. While it was previously reported that, on average, homointerfaces contain a greater number of interacting residues,54 for the representative set of homo- and heteroproteins considered here when clustered at the 40% sequence identity level, this is not in fact the case. The average and standard deviation of the number of interprotein contacts in homointerfaces is 61.6 ± 37.6 versus 60.4 ± 37.2 in heterointerfaces. Thus, their size is essentially the same.

Figure 2.

Cumulative distribution of the fraction of half-interfaces containing ligand binding pockets whose volume is at least 500 Å3, with a minimum of 6 residues overlapping with the respective half-interface versus the fraction of the half-interface that coincides with a pocket. (A) Both half-interfaces have ligand binding pockets that satisfy the above criterion. (B) For heterointerfaces, comparison of pocket coverage of an interface when significant size pockets are in just one or both half-interfaces. (C) For homointerfaces, comparison of pocket coverage of interface when significant size pockets are in just one or both half-interfaces.

Comparing the fraction of the surface that is associated with the pocket in case B versus case C, for both homo- and heterointerfaces, when there is just a single pocket in the interface, they are systematically larger. Perhaps pocket geometries involve hot spots (this is demonstrated below), and the greater the number of hot spots is, the more stabilizing the interaction is. If there is just a single pocket in the combined interface, then the pocket surface area must be larger to generate a favorable protein–protein interaction. This point demands further experimental investigation, but support is provided in Table 2 which shows the relative amino acid composition in each half-interface that contains a pocket relative to the case when just a single half-interface contains a pocket. The general pattern for homo- and heterointerfaces is the same, with trivial differences in relative amino acid composition. The most enriched residues are those which are very abundant in pockets, especially those at the bottom of pockets: ARG, HIS, PHE, TYR, and TRP. There is a slight enrichment in LEU and ILE.

Table 2. Comparison of Relative Composition of the Interface Pocket Where Each Half-Interface Contains a Pocket versus Just a Single Half-Interface Contains a Pocket.

| residue | homointerfaces relative ratio in half-interface with a pocket in each half-interface pockets vs an interface containing a single pocket | heterointerfaces relative ratio in half-interface with a pocket in each half-interface pockets vs an interface containing a single pocket |

|---|---|---|

| GLY | 0.827 | 0.824 |

| ALA | 0.869 | 0.857 |

| SER | 0.901 | 0.968 |

| CYS | 1.029 | 0.910 |

| VAL | 0.975 | 0.946 |

| THR | 0.930 | 0.872 |

| ILE | 1.063 | 1.106 |

| PRO | 0.953 | 0.934 |

| MET | 1.045 | 1.003 |

| ASP | 0.946 | 0.930 |

| ASN | 0.991 | 1.004 |

| LEU | 1.076 | 1.013 |

| LYS | 0.997 | 1.032 |

| GLU | 0.945 | 0.969 |

| GLN | 0.990 | 1.037 |

| ARG | 1.135 | 1.112 |

| HIS | 1.075 | 1.214 |

| PHE | 1.172 | 1.141 |

| TYR | 1.208 | 1.191 |

| TRP | 1.163 | 1.205 |

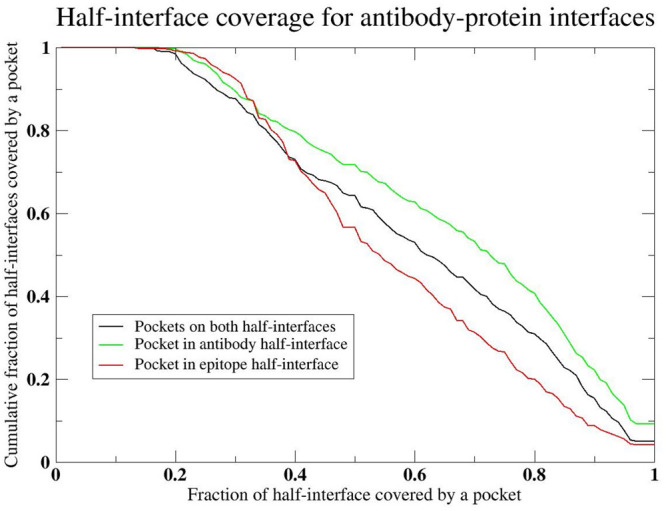

Analysis of Antibody–Epitope Interfaces

We next considered a representative library of 2,347 antibody–protein complexes and explored if their interfaces also contain small molecule ligand binding pockets. Their average number of interprotein contacts is 14.8 ± 6.7. Thus, a given antibody–protein interface is considerably smaller than the average protein–protein interface that involves about 60 interacting residues. Table 3 presents the results of the coincidence of pockets and epitope interfaces.

Table 3. Analysis of Coincidence of Pockets and Interfaces in Antibody–Protein Interfacea.

| no. of interfaces | % of interfaces with at least 5 contacting residues in both pockets | % of interfaces with a pocket in an antibody half-interface with at least 5 contacting residues with a nonpocket region in the epitope of the other protein | % of interfaces with a pocket in the epitope half-interface with at least 5 contacting residues with a nonpocket region in the antibody | no. of interacting pairs with no significant size pockets in their interface |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,347 | 16.6% | 27.4% | 21.5% | 34.5% |

Each pocket must have a minimum volume of 500 Å3 so that it could potentially bind a small molecule ligand; in addition, a minimum of 6 of its residues must interact with the corresponding half-interface.

The majority of interfacial antibody–protein interfaces involve just a single pocket interacting with a convex surface on the partner interface. The pocket is more frequently present in the antibody half-interface (27.4%) rather than in the partner protein’s half-interface (21.5%). Thus, in 44% of cases, a pocket in the antibody is involved in the interprotein interaction. As in the case of general protein–protein interactions, a pocket (on either half-interface) is involved in the protein–protein interaction in roughly 2/3 of the cases.

For antibodies, Figure 3 shows the fractional half-interface coverage by pockets. Interestingly for the majority of situations, pockets in the antibody half-interface cover a larger fraction of the half-interface than the corresponding epitope half-interface. The fractional surface area of the epitope that is part of the interface is considerably smaller for the most part than the fraction of the surface area containing a pocket from the antibody. Thus, the variable regions of the antibody seem to prefer to form pockets.

Figure 3.

Cumulative distribution of the fraction of half-interfaces containing ligand binding pockets whose volume is at least 500 Å3 with a minimum of 6 residue overlap with the respective half-interface versus the fraction of the half-interface that coincides with a pocket.

There is an interesting implication of these results that addresses the question of how can antibodies rather quickly evolve to bind an arbitrary epitope, include those that it has never seen in nature.55−57 This arises from the fact that the number of stereochemically distinct PPI surfaces as modulated when appropriate by pockets is limited. Thus, the conformational search to find appropriate binding motifs that can interact with an arbitrarily chosen ligand is far smaller than might be expected at face value. The same rules that led to the formation of ligand binding pockets in single domain58 proteins and generic protein–protein interfaces20 that reflect the inherent geometric features of proteins are operative here.

Relationship of Hot Spots and Interfacial Ligand Binding Pockets

Where do protein hot spots tend to occur? To address this question, we examine the set of hot spots residues identified in 50 distinct protein–protein interaction and divided the data with respect to different regions of binding free energy changes, ΔG.9 As shown clearly in Table 4, in all cases the majority of hot spot residues coincide with pockets, with the fraction increasing when ΔG ≥ 1 kcal/mol. A tiny minority of hot spots are in the convex surface of the partner half-interface that protrudes into the pocket. While there have been a number of studies that suggest that some hot spots occur in pockets, the results presented here are for a larger set involving 638 residues participating in 50 distinct protein–protein interactions. Thus, it seems plausible that protein pockets play an important role in stabilizing interprotein interactions.

Table 4. Analysis of Hot Spot Residue Location for PIIMS Hot Spot Database.

| free energy change on mutation | no. of unique hot spot residues | fraction (no.) of hot spot residues in pockets | fraction (no.) of hot spot residues whose partner is in a pocket | fraction of hot spot residues not associated with a pocket |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔG < 1 kcal/mol | 396 | 76.8% (304) | 3.8% (15) | 19.4% (77) |

| 2 kcal/mol > ΔG ≥ 1 kcal/mol | 123 | 86.2% (106) | 1% (1) | 12.8% (16) |

| ΔG ≥ 2 kcal/mol | 119 | 86% (111) | 2.3% (3) | 11.7% (15) |

Implications of the Overlap of Protein–Protein Interfaces and Ligand Binding Pockets

We noted above that the library of protein–protein interfaces is very small,20 with ∼1000 or so structurally distinct interfaces. Similarly, there is a very small library of ligand binding pockets.21,22 Previously, these results were treated as disjoint; now it is clear that they actually reflect significant redundancy. Protein pockets often make up a considerable portion of the PPI; thus, the only real question is the completeness of the remaining nonpocket portion of the surfaces. Both are the result of generic geometric features of proteins and occur in rather small structural libraries generated by typical protein folding simulations.20,21,58 Their significant overlap strongly suggests that PPI and small molecule–protein ligand binding might be strongly coupled. The implications of this conjecture are explored below.

Possible Role of Metabolites in the Regulation of Protein–Protein Interactions and the Coupling of Protein Multimers That Do Not Directly Interact

Given the plethora of small molecule ligand binding pockets that occur in protein–protein interfaces, the fact that a subset of these are targets of small molecule drugs that inhibit protein–protein interactions,59,60 and the following PDB analysis and VLS results that strongly suggest that metabolites can bind to the pockets associated with protein–protein interfaces, we conjecture that the metabolome is strongly coupled to the protein–protein interactome. A schematic representation of this idea is presented in Figure 4A,B. In Figure 4A, the equilibrium between a metabolite that binds to two distinct protein–protein interfaces associated with two dimeric proteins is shown. The binding of a metabolite could shift the equilibria of protein–protein interactions. Say, for example, the binding free energy of the metabolite favors binding to the green protein over the dark blue protein (top row) due to an allosteric transition in the blue protein. This can shift the equilibrium to the dimeric state of the green and yellow protein pair. Thus, even though the pair of blue proteins do not directly interact with either the green or yellow protein, the metabolite couples their state of association. Thus, it might cause protein complexes within a given biochemical pathway or in different biochemical pathways to be coupled. For just these four protein molecules, Figure 4A shows how their various equilibrium states are related to each other. Here, the metabolite acts as an antagonist and disrupts protein–protein interactions.

Figure 4.

(A) Representation of the equilibrium between two pairs of interacting proteins (dark/light blue and green/yellow) and a small molecule metabolite (red sphere) whose binding to either the blue or green protein shifts the respective dimeric equilibrium to monomers. Thus, the metabolite acts as an antagonist to protein–protein binding. (B) When two molecules (orange and purple) bind, they create a small molecule ligand binding pocket immediately adjacent to the protein–protein interface. The binding of the metabolite now stabilizes the dimeric conformation and acts as an agonist for the protein–protein interaction.

Figure 4B shows how the binding of a metabolite can also stabilize protein–protein interactions. When a pair of molecules associate (orange and purple), they form a small molecule ligand binding pocket immediately adjacent to the ligand binding interface. This interface adjacent pocket is absent when the molecules are unassociated. Interestingly, these interfacial pockets are part of the same library of ligand binding pockets that occur on the surface of single domain proteins. The presence of this pocket enables the metabolite to bind, further stabilizing the dimer. As mentioned above and highlighting their importance, mutations in such interface adjacent residues have a high likelihood of being disease associated.15 If the pair of proteins only weakly bind without the metabolite, one might imagine circumstances where binding the metabolite shifts the equilibrium to form a highly stabilized complex.

Could Metabolites Disrupt Protein–Protein Interactions?

To establish the plausibility of this conjecture, we performed the following analysis: In the entire PDB, we identified 16,186 ligands that bind to highly homologous monomers (see Supporting Information, LIST.multimers_metabolites) in the corresponding half-interface residues of the target monomer. In practice, we found 1,561 different monomers. As an example and restricting our analysis to human proteins, 5jsnAB is predicted to bind 1XJ (4-(4-{[2-(4-chlorophenyl)-5,5-dimethylcyclohex-1-en-1-yl]methyl}piperazin-1-yl)-N-[(4-{[(2R)-4-(morpholin-4-yl)-1-(phenylsulfanyl)butan-2-yl]amino}-3-[(trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl]phenyl)sulfonyl]benzamide) when transferred from 6qghA whose sequence identity is 81.2% to 5jsnA. In this case, there are 18 residues in contact with the ligand (see Figure 5). Another monomer 4lvtA whose sequence identity to 5jsnA is 96.6% predicts the same binding metabolite.

Figure 5.

(A) Superposition of 1XJ onto the 5jsnAB interface. Green shows the 5jsnA monomer that is predicted to bind 1XJ (in red) 4-(4-{[2-(4-chlorophenyl)-5,5-dimethylcyclohex-1-en-1-yl]methyl}piperazin-1-yl)-N-[(4-{[(2R)-4-(morpholin-4-yl)-1-(phenylsulfanyl)butan-2-yl]amino}-3-[(trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl]phenyl)sulfonyl]benzamide when it is dissociated from 5jsnB. The ligand is transferred from 6qghA. (B) Structure of the 5jsnAB dimer superimposed over the predicted binding pose of 1XJ. 5jsnB is colored in silver.

We next examined the PDB for more examples of the same metabolite binding in the interface between two dimers in human proteins. We find 48 metabolites predicted to bind to the interface of at least two dimers (see Supporting Information, LIST.multimers_metabolites_human.clus). We then searched for nontrivial examples of pairs of dimers whose monomer is predicted to bind the same metabolite, yet their pairwise sequence identity is <30%. Figure 6 shows an example of PDB id 2rd7CA, human complement protein C8,61 whose monomer C is homologous to 1lf7A that binds citric acid. The second dimer is 1z7xXW, human ribonuclease A (RNase A) whose monomer 1z7xX is 100% identical to 2q4GX that also binds citric acid.62 We note that the pairwise sequence identity of 1z7xX to 2rd7C is 7.5%. Thus, this is a nontrivial example of the schematic illustration depicted in Figure 4A.

Figure 6.

Possible binding equilibria between 2rd7CA and 1z7xXW for which citric acid is predicted to bind chain C in 2rd7 and chain X in 1z7x. Chains C and A in 2rd7 are shown in blue and purple, and chains X and W are shown in green and yellow. Citric acid is shown in red.

Rnase A is expressed in most tissues, and human complement protein C8 is expressed in the serum;63 the latter plays an important role in antibacterial immunity.64 Interestingly, Rnase A is secreted by a diverse collection of immune cells65 and plays a role in immune response. Thus, perhaps their regulation by citric acid might be important, as it is known to play a role in regulating immune response.66

Use of Common Binding Metabolites to Infer Possible Functional Relationships among Multimeric Proteins

Motivated by the above results, we next explored the use of similar ligand binding pockets in multimeric interfaces to infer protein functional relationships. From a list of 1,424 human heteromers (see Supporting Information, LIST.human_apoc_molecule.2), we performed structural alignments of their respective pockets and eliminated all pairs of multimers whose sequence identity to the target monomer in the dimer whose interfacial pocket is being compared is >40%. We further considered only structurally unrelated pairs of proteins (those with TM-score < 0.4) which have at least 3 identical aligned residues in their pockets whose p-value < 0.05. As proof of principle, we considered 10 randomly chosen cases that at face value are not trivially associated. Of course, we realize that this is but a first step, but this approach can be viewed as a hypothesis generator to suggest which metabolite driven functional associations can be tested experimentally.

The results of this analysis are presented in Table 5. For the case of erythropoietin, it has a strong pocket match to N6 adenosine-methyl transferase. The two proteins are related as N6 methylation promotes selective translation of regulons required for human erythropoiesis adenosine marking.67 Moesin and renin have significant ligand binding pocket similarity, and both are implicated in glomerulonephritis.68 Gelsolin is an actin binding/severing protein involved in cardiac remodeling following myocardial infarction as is cathepsin L.69,70 Both cyclin-dependent kinase 5 and ephrin type A-receptor 2-tyrosine kinase, which share strong pocket similarity, are associated with neuronal networking.71 Calgranulin and S adenosylmethionine decarboxylase β both play a significant role in inflammatory arthritis.72,73 Uracil-DNA glycosylase and cathepsin L may play an antagonistic role in cancers.74,75 Ras-related protein RAL-A and ephrin-type A receptor 3 are important in cancer progression.76 Caspase-3 is involved in apoptosis77 while fibrinogen α is involved in blood clotting.78,79 By activating neutrophils, fibrinogen plays a role in delaying apoptosis.80 SUMO conjugating enzyme UBC9 and Legumain influence stem cell differentiation.81,82 Ubiquitin conjugating enzyme E2 is associated with HLA CLASS I histocompatibility antigen by the role ubiquitylation plays in generating MHC class I peptide ligands.83 Thus, this simple approach is quite successful in identifying possible functional associations.

Table 5. Analysis of Representative Set of Predicted Possible Metabolism-Coupled Processes Based on Pocket Similarity in Proteins with Different Global Structure.

| parent protein (pdb code) | protein with similar pocket | predicted coupled cellular process | pairwise sequence identity | TM-score of proteins | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| erythropoietin (1eerAB), responsible for manufacture of red blood cells;84 EPO induced gene expression and cancer cell migration are modified by poly AD ribosylation85 | N6 adenosine-methyl transferase involved in post translational RNA modification84 (5k7uA) | N6 methylation promotes selective translation of regulons required for human erythropoiesis adenosine marking67 | 0.15 | 0.3 | 3.3 × 10–3 |

| moesin (1ef1AC) connects the actin cytoskeleton to the plasma membrane86 | renin (3oadA), major enzyme involved in control of blood pressure87 | renin linkage cells repopulate glomerular mesangium after injury;88 moesin is upregulated in experimental mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis68 | 0.05 | 0.36 | 4.0 × 10–2 |

| gelsolin precursor (1mduAC), actin binding/severing protein;89 is involved in cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction69 | cathepsin L (5ih4A), progranulin protease involved in the lysosomal/autophagy pathway90 and cardiac repair and modeling70 after myocardial infarction | both proteins are involved in cardiac remodeling | 0.05 | 0. 24 | 3.2 × 10–2 |

| cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (1unlAD) is associated with neuronal development and function91 | ephrin type A-receptor 2-tyrosine kinase (3heiA) play an important role in homeostasis and transmit signals associate with cell–cell communication92 and neuronal networking71 | plays a role in central nervous system recovery and neuronal networking | 0.06 | 0.19 | 6.6 × 10–3 |

| calgranulin (1xk4AC) is a calcium binding protein involved in inflammatory arthritis93 | S adenosylmethionine decarboxylase β (3ep5A) converts S-adenosyl methionine (SAMe) to S-adenosylmethionamine94 | SAMe stimulates cartilage and may reduce osteoarthritis pain72,73 | 0.15 | 0.39 | 2.5 × 10–2 |

| uracil-DNA glycosylase (1zoqAC) prevents mutagenesis95 | cathepsin B (2ippA) is a lysosomal cysteine protease that is upregulated in certain cancers96 | DNA glycosylase enhances fitness of normal and cancer cells and is possibly antagonistic to cathepsin B74,75 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 1.9 × 10–3 |

| Ras-related protein RAL-A (2a9kAB) is involved in many cellular processes including cell migration and proliferation, oncogenic transformation, and cellular trafficking97 | ephrin-type A receptor 3 (4l0pA), a receptor tyrosine kinases is involved in bidirectional signaling98 is highly expressed in cancer tumors99,100 | RAL-A is responsible for regulating tumor initiation, invasion, and migration;76 both proteins are very important for cancer progression | 0.08 | 0.36 | 2.8 × 10–2 |

| caspase-3 (2h65CD) is a lysosomal enzyme involved in apoptosis77 | fibrinogen α (3e1iD) is involved in blood clotting78,79 | fibrinogen by promoting neutrophil activation delays apoptosis80 | 0.03 | 0.23 | 2.3 × 10–2 |

| SUMO conjugating enzyme UBC9 (2pe6AB) helps with inducing and maintaining stem cell pluripotency81 and protein localization | legumain (2n6oA) is a cysteine protease that hydrolyzes asparaginyl bonds that regulates the lineage commitment of human bone marrow stromal cells82 | both have an influence on stem cell differentiation | 0.05 | 0.35 | 6.5 × 10–3 |

| ubiquitin conjugating enzyme E2 (4auqAC) is an important component of the ubiquitin-proteosome system101 | HLA class I histocompatibility antigen (3ln5A) is responsible for antigen processing and presentation52 | ubiquitylation plays a varied role in generating MHC class I peptide ligands83 | 0.25 | 0.32 | 1.86 × 10–3 |

We next performed virtual ligand screening (VLS) on the library of human metabolites HMDB (up to June 10, 2022)48 and DrugBank (v5.09)51 drugs using FINDSITEcomb2.045 and FRAGSITE.46 The full set of VLS results are found in Supporting Information. We then checked whether, because of their pocket similarity, pairs of evolutionarily unrelated monomers shown in Table 5 hit similar drugs/metabolites. Using FINDSITEcomb2.0, these 5 pairs, 1eerAB-5k7uA, 1mduAB-5i4hA, 1unlAD-3heiA, 1xk4AC-3ep5A, 4auqAC-3ln5A have drug overlaps. These 5 pairs 1mduAB-5i4hA, 1unlAD-3heiA, 1xk4AC-3ep5A, 2pe6AB-4n6oA, 4auqAC-3ln5A, bind the same metabolites. From FRAGSITE, these 4 pairs, 1eerAB-5k7uA, 1mduAB-5i4hA, 1unlAD-3heiA, 2a9kAB-4l0pA, bind the same drugs. These 3 pairs, 1mduAB-5i4hA, 1unlAD-3heiA, 2a9kAB-4l0pA, are predicted to bind common metabolites. Consistent with these results, due to the recall rate of FINDSITEcomb2.0/FRAGSITE of 30–40%,46 up to 5 predictions out of 10 pairs are expected if all pairs indeed bind similar drugs/metabolites.

We next discuss an example of overlapping metabolites for 1mduAB-5i4hA. FINDSITEcomb2.0 (FRAGSITE) predicts 817 (328) similar metabolites. Among the 238 consensus metabolites, bradykinin,102 tuftsin,103 endomorphin-2,104 and dynorphin,105 are heart-disease-related (see Table 5). Another example is 1unlAD-3heiA, where 96 consensus overlapped metabolites are predicted. Among them are cyclic AMP,106 sorafenib,107 and ruboxistaurin108 that have known effects on the nervous system. A third example is the pair 2a9kAB-4l0pA that is involved in cancer. FRAGSITE predicts 7 overlapped metabolites including lestaurtinib, a potent thyroid cancer cell line inhibitor;109O-desmethyl midostaurin, a possible treatment for acute myelogenous leukemia;110 Cep-1347, a potential anticancer drug;111 and a drug, 7-hydroxystaurosporine, that inhibits breast cancer.112 This analysis further supports the plausibility of the conjecture that common metabolites are possibly modulating protein–protein interactions.

Analysis of Interface Adjacent Metabolites

As indicated in the Methods section, we identified 3,392 dimers which have metabolites that bind adjacent to the protein–protein interface. There are a total of 126 different metabolites (see Supporting Information, LIST.multimers_metabolite.adj.clus). Among the top 10 is TPO, phosphothreonine (see Figure 7A), and TGL, tristearolylglycerol (see Figure 7B). As shown in Figure 7B, TPO contains long chain hydrocarbons that act as tentacles to hold the two proteins together. Another common long chain hydrocarbon found adjacent to protein–protein interfaces is PEK ((1s)-2-{[(2-aminoethoxy)(hydroxy)phosphoryl]oxy}-1-[(stearoyloxy)methyl]ethyl. Interestingly, this seems to be a quite typical situation of interfacial ligands.

Figure 7.

(A) 4eomBA.pdb, CDK2, whose chains B and A are in purple and orange with TPO as the interfacial ligand.113 (B) 5x19AL.pdb114 is a cytochrome c oxidase whose chains are shown in purple and orange and the interfacial ligand TGL is shown in red.

Discussion and Conclusions

In this work, we clearly established the relationship between small molecule ligand binding pockets and protein–protein interfaces. This result is consistent with the discovery of small molecule drugs that inhibit protein–protein interactions and which have met with increasing success particularly in the field of cancer.4,12 In reality, if there were no small ligand binding pockets that were involved in key interaction sites, also known as hot spots, it is highly unlikely that a small molecule could disrupt protein–protein interactions; it would have no place to bind. In practice, roughly 2/3 of interfaces contain at least one significant small molecule binding pocket that could be the target of either a novel drug to disrupt the interaction, or as discussed below, they may actually play a fundamental role in how metabolites help regulate and are regulated by protein–protein interactions. Moreover, in a representative library of 50 distinct protein–protein interactions involving hundreds of mutations, we demonstrated that on average from 75% to 86% of hot spot residues are involved in small molecule ligand binding pockets; the remainder are possibly involved in surfaces likely responsible for the binding of linear peptides.

We next examined the special class of protein–protein interactions associated with antibody binding to their respective protein epitope. While the antibody–epitope interface is on average considerably smaller than an average protein–protein interface, many of the rules remain qualitatively the same. Roughly 2/3 of the antibody–protein interfaces contain at least one pocket, a portion of which could potentially bind a small molecule ligand. The results of this and the more general analysis suggest that protein–protein interactions and small molecule ligand interactions have far more in common than was previously realized.

What is perhaps the most important contribution of this particular work is the recognition that it is quite likely that metabolites can regulate protein–protein interactions and therefore can lead to the coupling of distinct biochemical processes. We term such regulation “metabolic entanglement” as it enables the coupling of sets of proteins that do not directly interact by shifting their multimeric equilibrium due to the binding of metabolites that disrupt or encourage protein–protein interactions. We have presented literally thousands of examples that are found in the PDB showing how such metabolites bind within or adjacent to protein–protein interfaces. Furthermore, our VLS results on 10 representative pairs of possible metabolite-coupled protein–protein/monomer targets show they likely hit the same subsets of drugs/metabolites. Examples from the literature provide evidence that indicates that the overlapped hits involve the same physiology/disease process in the coupled protein pairs. Thus, these preliminary results are quite promising.

It is often reported that metabolite levels change in diseased versus normal states.115−120 This could be the result of one of two possibilities:121,122 Metabolite levels could have changed as a consequence of the disease, or the change in metabolite levels could be a partial driver of the disease.121,122 We suspect that, depending on the metabolite, both situations occur. However, if the change in metabolite levels is partly driving the disease (an example in cancer is found in refs (121 and 123)), the question is how in reality does this contribute to cancer onset/progression? Perhaps the metabolite binds to small molecule pockets that could potentially disrupt protein–protein interactions or conversely binds adjacent to protein interfaces that strengthen such interactions and could shift weak quaternary structure binding to a strong interaction. As shown in Table 5, by way of illustration, this work suggests a concrete mechanism regarding how such metabolites might be involved in the delay of apoptosis (the caspase3/fibrinogen) and cancer progression (RALA and ephrin-type A). More generally, metabolite binding could either disrupt or enhance protein–protein interactions.

What this study strongly suggests is that small molecule–protein and protein–protein interactions reflect similar physical interactions and are governed by similar rules as protein pockets typically comprise roughly 50% of the surface of a protein–protein interface. Thus, rather than treating metabolomics and protein–protein interactomics as being disjoint and separate, one might envision a unification of the two fields. Of course, at present, these conjectures are partly circumstantial and will need to be further validated by experiment. Work is ongoing in our group to take the first steps toward accomplishing this goal.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by R35 GM-118039 of the Division of General Medical Sciences of the NIH. We thank Bartosz Ilkowski for internal computing support, Samuel Skolnick for useful discussions and suggesting the term Metabolic Entanglement, Mu Gao for useful discussions, and Jessica Forness for proofreading the manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- PPI

protein–protein interactions

- VLS

virtual ligand screening

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jpcb.2c04525.

Spreadsheet containing the following: LIST.homo_interface and LIST.hetero_interface, list of homo- and heteromultimers whose interfaces were analyzed; LIST_homo_interface.X and LIST.het_interface.X (X = 60 and 40 are clustered at X% sequence identity); LIST.ligands_assigned, representative set of ligands in PDB files clustered at 65% sequence identity assigned by CAVITATOR to a pocket; LIST.nopocket ligand, representative set of ligands in PDB files clustered at 65% sequence identity assigned by CAVITATOR to a pocket; LIST.antibodies, representative set of antibody structures that were analyzed (the data from the training set of the PIIMS Server which contains 1,341 mutations involving 50 distinct protein–protein interactions were clustered into those whose binding free energy change, ΔG, was <1 kcal/mol (LIST.deltaG_cold.res.unique), >1 kcal/more (see LIST.deltaG1.res.unique), and >2 kcal/mol (see LIST.deltaG2.res.unique)); LIST.metabolites, the set of ligands that are human metabolites in the Human Metabolome database that are found in PDB structures; LIST.pdb_chain.800, list protein dimers from the PDB between 41 and 800 residues in length; LIST.pdb_chain.800.1.human, list of human protein dimers from the PDB between 41 and 800 residues in length; LIST.pkt_interface_AB_AB.gt5, list of PDB heteromultimers that have least 5 interfacial contacts in each half-interface that are between 41 and 800 residues in length; LIST.multimers_metabolites, list of heterodimers (the homologous monomeric protein and their associated metabolites that are predicted bind to at least four half-interface residues in the first of the two chains (e.g., 1xyzAB, chain A)); LIST.multimers_metabolites_names.pdb.unique, the set of unique target multimers in LIST.multimers_metabolites; LIST.multimers_metabolites_human, subset of LIST.multimers_metabolites that involve human proteins; LIST.pkt_interface_ab_ab.gt5.b_adj, list of multimers and their associated interface adjacent binding metabolites; LIST.multimers_metabolites_human.adj, Subset of LIST.pkt_interface_ab_ab.gt5.b_adj that involve human proteins; LIST.human_apoc_molecule.2, 1424 multimer human protein multimers each chain of which is >40 residues whose pockets were compared to infer functional interactions; and the full set of VLS results as labeled “findsitecomb2_drug”, “findsitecomb2_hmdb”, “fragsite_drug”, and “fragsite_hmdb” (XLSX)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. J.S. conceived of the idea and performed the majority of the analyses. H.Z. performed the virtual screening of repurposed drugs and metabolites.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Special Issue

Published as part of The Journal of Physical Chemistry virtual special issue “Protein Folding and Dynamics—An Overview on the Occasion of Harold Scheraga’s 100th Birthday”.

Supplementary Material

References

- Chieh C.Intermolecular Forces; 2020. https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Physical_and_Theoretical_Chemistry_Textbook_Maps/Map%3A_Physical_Chemistry_for_the_Biosciences_(Chang)/13%3A_Intermolecular_Forces/13.1%3A_Intermolecular_Interactions (accessed July 2022). [Google Scholar]

- De Las Rivas J.; Fontanillo C. Protein-protein interactions essentials: key concepts to building and analyzing interactome networks. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2010, 6 (6), e1000807. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao T.; Liu J.; Zeng X.; Wang W.; Li S.; Zang T.; Peng J.; Yang Y. Prediction and collection of protein-metabolite interactions. Brief Bioinform 2021, 22 (5), bbab014. 10.1093/bib/bbab014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S.; Yang G.; Wang W.; Leung C.; Ma D. The design and development of covalent protein-protein interaction inhibitors for cancer treatment. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2020, 13, 26. 10.1186/s13045-020-00850-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma B.; Nussinov R. Druggable orthosteric and allosteric hot spots to target protein-protein interactions. Curr. Pharm. Des 2014, 20 (8), 1293–1301. 10.2174/13816128113199990073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London N.; Raveh B.; Schueler-Furman O. Druggable protein-protein interactions--from hot spots to hot segments. Curr. Opin Chem. Biol. 2013, 17 (6), 952–959. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Keskin O.; Ma B.; Nussinov R.; Liang J. Protein-protein interactions: hot spots and structurally conserved residues often locate in complemented pockets that pre-organized in the unbound states: implications for docking. J. Mol. Biol. 2004, 344 (3), 781–795. 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basse M. J.; Betzi S.; Morelli X.; Roche P. 2P2Idb v2: update of a structural database dedicated to orthosteric modulation of protein-protein interactions. Database (Oxford) 2016, 2016, baw007. 10.1093/database/baw007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F. X.; Yang J. F.; Mei L. C.; Wang F.; Hao G. F.; Yang G. F. PIIMS Server: A Web Server for Mutation Hotspot Scanning at the Protein-Protein Interface. J. Chem. Inf Model 2021, 61 (1), 14–20. 10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbe B. S.; Hall D. R.; Vajda S.; Whitty A.; Kozakov D. Relationship between hot spot residues and ligand binding hot spots in protein-protein interfaces. J. Chem. Inf Model 2012, 52 (8), 2236–2244. 10.1021/ci300175u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S. H.; Choi K. Y. Screening-based approaches to identify small molecules that inhibit protein-protein interactions. Expert Opin Drug Dis 2017, 12 (3), 293–303. 10.1080/17460441.2017.1280456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.; Dawber R. S.; Zhang P.; Walko M.; Wilson A. J.; Wang X. Peptide-based inhibitors of protein-protein interactions: biophysical, structural and cellular consequences of introducing a constraint. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12 (17), 5977–5993. 10.1039/D1SC00165E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Rabbitts T. H. Intracellular antibody capture: A molecular biology approach to inhibitors of protein-protein interactions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1844 (11), 1970–1976. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M.; Skolnick J. The distribution of ligand-binding pockets around protein-protein interfaces suggests a general mechanism for pocket formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012, 109 (10), 3784–3789. 10.1073/pnas.1117768109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M.; Zhou H.; Skolnick J. Insights into Disease-Associated Mutations in the Human Proteome through Protein Structural Analysis. Structure 2015, 23 (7), 1362–1369. 10.1016/j.str.2015.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonddast-Navaei S.; Skolnick J. Are protein-protein interfaces special regions on a protein’s surface?. J. Chem. Phys. 2015, 143 (24), 243149. 10.1063/1.4937428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S.; Chakrabarti S. Classification and prediction of protein-protein interaction interface using machine learning algorithm. Sci. Rep 2021, 11 (1), 1761. 10.1038/s41598-020-80900-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai B.; Bailey-Kellogg C. Protein Interaction Interface Region Prediction by Geometric Deep Learning. Bioinformatics 2021, 37 (17), 2580–2588. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btab154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W.; Wisniewski J. A.; Ji H. Hot spot-based design of small-molecule inhibitors for protein-protein interactions. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24 (11), 2546–2554. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.03.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M.; Skolnick J. Structural space of protein-protein interfaces is degenerate, close to complete, and highly connected. P Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107 (52), 22517–22522. 10.1073/pnas.1012820107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skolnick J.; Gao M. Interplay of physics and evolution in the likely origin of protein biochemical function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110 (23), 9344–9349. 10.1073/pnas.1300011110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M.; Skolnick J. A comprehensive survey of small-molecule binding pockets in proteins. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2013, 9 (10), e1003302. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M.; Skolnick J. APoc: large-scale identification of similar protein pockets. Bioinformatics 2013, 29 (5), 597–604. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonddast-Navaei S.; Srinivasan B.; Skolnick J. On the importance of composite protein multiple ligand interactions in protein pockets. J. Comput. Chem. 2017, 38 (15), 1252–1259. 10.1002/jcc.24523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abagyan R.; Totrov M.; Kuznetsov D. ICM - a new method for protein modeling and design: applications to docking and structure prediction from the distorted native conformation. J. Comput. Chem. 1994, 15, 488–506. 10.1002/jcc.540150503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing T. J.; Makino S.; Skillman A. G.; Kuntz I. D. DOCK 4.0: search strategies for automated molecular docking of flexible molecule databases. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des 2001, 15 (5), 411–428. 10.1023/A:1011115820450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesner R. A.; Banks J. L.; Murphy R. B.; Halgren T. A.; Klicic J. J.; Mainz D. T.; Repasky M. P.; Knoll E. H.; Shelley M.; Perry J. K.; et al. Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47 (7), 1739–1749. 10.1021/jm0306430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trott O.; Olson A. J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31 (2), 455–461. 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan R. P.; Nam K.; Maiorov V. N.; McMasters D. R.; Cornell W. D. QSAR models for predicting the similarity in binding profiles for pairs of protein kinases and the variation of models between experimental data sets. J. Chem. Inf Model 2009, 49 (8), 1974–1985. 10.1021/ci900176y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khedkar V. M.; Coutinho E. C. CoRILISA: a local similarity based receptor dependent QSAR method. J. Chem. Inf Model 2015, 55 (1), 194–205. 10.1021/ci5006367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasanth Kumar S.; Jasrai Y. T.; Pandya H. A.; Rawal R. M. Pharmacophore-similarity-based QSAR (PS-QSAR) for group-specific biological activity predictions. J. Biomol Struct Dyn 2015, 33 (1), 56–69. 10.1080/07391102.2013.849618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallach I.; Dzamba M.; Heifets A.. AtomNet: A Deep Convolutional Neural Network for Bioactivity Prediction in Structure-Based Drug Discovery. arXiv preprint 2015, 1510.02855. [Google Scholar]

- Ragoza M.; Hochuli J.; Idrobo E.; Sunseri J.; Koes D. R. Protein–Ligand Scoring with Convolutional Neural Networks. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2017, 57, 942–957. 10.1021/acs.jcim.6b00740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brylinski M.; Skolnick J. Q-Dock: Low-resolution flexible ligand docking with pocket-specific threading restraints. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29 (10), 1574–1588. 10.1002/jcc.20917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brylinski M.; Skolnick J. A threading-based method (FINDSITE) for ligand-binding site prediction and functional annotation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008, 105 (1), 129–134. 10.1073/pnas.0707684105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brylinski M.; Skolnick J. FINDSITE(LHM): a threading-based approach to ligand homology modeling. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009, 5 (6), e1000405. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brylinski M.; Skolnick J. FINDSITE: a threading-based approach to ligand homology modeling. PLoS computational biology 2009, 5 (6), e1000405. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skolnick J.; Brylinski M. FINDSITE: a combined evolution/structure-based approach to protein function prediction. Brief Bioinform 2009, 10 (4), 378–391. 10.1093/bib/bbp017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brylinski M.; Skolnick J. Q-Dock(LHM): Low-resolution refinement for ligand comparative modeling. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31 (5), 1093–1105. 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brylinski M.; Skolnick J. FINDSITE-metal: integrating evolutionary information and machine learning for structure-based metal-binding site prediction at the proteome level. Proteins 2011, 79 (3), 735–751. 10.1002/prot.22913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A.; Yang J.; Zhang Y. COFACTOR: an accurate comparative algorithm for structure-based protein function annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40 (W1), W471–W477. 10.1093/nar/gks372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H.; Skolnick J. FINDSITE(comb): a threading/structure-based, proteomic-scale virtual ligand screening approach. J. Chem. Inf Model 2013, 53 (1), 230–240. 10.1021/ci300510n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson J. A.; Jalaie M.; Robertson D. H.; Lewis R. A.; Vieth M. Lessons in molecular recognition: the effects of ligand and protein flexibility on molecular docking accuracy. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47 (1), 45–55. 10.1021/jm030209y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumper J.; Evans R.; Pritzel A.; Green T.; Figurnov M.; Ronneberger O.; Tunyasuvunakool K.; Bates R.; Zidek A.; Potapenko A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H.; Cao H.; Skolnick J. FINDSITE(comb2.0): A New Approach for Virtual Ligand Screening of Proteins and Virtual Target Screening of Biomolecules. J. Chem. Inf Model 2018, 58 (11), 2343–2354. 10.1021/acs.jcim.8b00309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H.; Cao H.; Skolnick J. FRAGSITE: A Fragment-Based Approach for Virtual Ligand Screening. J. Chem. Inf Model 2021, 61 (4), 2074–2089. 10.1021/acs.jcim.0c01160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burley S. K.; Bhikadiya C.; Bi C.; Bittrich S.; Chen L.; Crichlow G. V.; Duarte J. M.; Dutta S.; Fayazi M.; Feng Z.; et al. RCSB Protein Data Bank: Celebrating 50 years of the PDB with new tools for understanding and visualizing biological macromolecules in 3D. Protein Sci. 2022, 31 (1), 187–208. 10.1002/pro.4213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart D. S.; Guo A.; Oler E.; Wang F.; Anjum A.; Peters H.; Dizon R.; Sayeeda Z.; Tian S.; Lee B. L.; et al. HMDB 5.0: the Human Metabolome Database for 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50 (D1), D622–D631. 10.1093/nar/gkab1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Skolnick J. TM-align: a protein structure alignment algorithm based on the TM-score. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33 (7), 2302–2309. 10.1093/nar/gki524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J.; Zhang Y. How significant is a protein structure similarity with TM-score = 0.5?. Bioinformatics 2010, 26 (7), 889–895. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart D. S.; Feunang Y. D.; Guo A. C.; Lo E. J.; Marcu A.; Grant J. R.; Sajed T.; Johnson D.; Li C.; Sayeeda Z.; et al. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46 (D1), D1074–D1082. 10.1093/nar/gkx1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek M.; Abualrous E. T.; Sticht J.; Alvaro-Benito M.; Stolzenberg S.; Noe F.; Freund C. Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) Class I and MHC Class II Proteins: Conformational Plasticity in Antigen Presentation. Front Immunol 2017, 8, 292. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georg G. I.; Sheng C.. Targeting Protein-Protein Interactions by Small Molecules, 1st ed.; Imprint; Springer: Singapore, 2018. 10.1007/978-981-13-0773-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhanhua C.; Gan J. G.; Lei L.; Sakharkar M. K.; Kangueane P. Protein subunit interfaces: heterodimers versus homodimers. Bioinformation 2005, 1 (2), 28–39. 10.6026/97320630001028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aulova K. S.; Urusov A. E.; Toporkova L. B.; Sedykh S. E.; Shevchenko Y. A.; Tereshchenko V. P.; Sennikov S. V.; Budde T.; Meuth S. G.; Orlovskaya I. A.; et al. Catalytic antibodies in the bone marrow and other organs of Th mice during spontaneous development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis associated with cell differentiation. Mol. Biol. Rep 2021, 48 (2), 1055–1068. 10.1007/s11033-020-06117-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohner I. E.; Mudrak I.; Kronlachner S.; Schuchner S.; Ogris E.. Antibodies recognizing the C terminus of PP2A catalytic subunit are unsuitable for evaluating PP2A activity and holoenzyme composition. Sci. Signal 2020, 13 ( (616), ). 10.1126/scisignal.aax6490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hifumi E.; Taguchi H.; Toorisaka E.; Uda T. New technologies to introduce a catalytic function into antibodies: A unique human catalytic antibody light chain showing degradation of beta-amyloid molecule along with the peptidase activity. FASEB Bioadv 2019, 1 (2), 93–104. 10.1096/fba.1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skolnick J.; Zhou H.; Gao M. On the possible origin of protein homochirality, structure, and biochemical function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019, 116 (52), 26571–26579. 10.1073/pnas.1908241116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkin M. R.; Tang Y.; Wells J. A. Small-molecule inhibitors of protein-protein interactions: progressing toward the reality. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21 (9), 1102–1114. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H.; Zhou Q.; He J.; Jiang Z.; Peng C.; Tong R.; Shi J. Recent advances in the development of protein–protein interactions modulators: mechanisms and clinical trials. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2020, 5 (1), 213. 10.1038/s41392-020-00315-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CBLC tissue expression in cancers. http://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000142273-CBLC/cancer (accessed July 2022).

- Johnson R. J.; McCoy J. G.; Bingman C. A.; Phillips G. N. Jr.; Raines R. T. Inhibition of human pancreatic ribonuclease by the human ribonuclease inhibitor protein. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 368 (2), 434–449. 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katona B.; Lindskog C. The Human Protein Atlas and Antibody-Based Tissue Profiling in Clinical Proteomics. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2420, 191–206. 10.1007/978-1-0716-1936-0_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubeck D.; Roversi P.; Donev R.; Morgan B. P.; Llorca O.; Lea S. M. Structure of human complement C8, a precursor to membrane attack. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 405 (2), 325–330. 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L.; Li J.; Moussaoui M.; Boix E. Immune Modulation by Human Secreted RNases at the Extracellular Space. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 1012. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zotta A.; Zasiona Z.; O’Neill L. Is Citrate A Critical Signal in Immunity and Inflammation?. Journal of Cellular SIgnaling 2020, 1, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kuppers D. A.; Arora S.; Lim Y.; Lim A. R.; Carter L. M.; Corrin P. D.; Plaisier C. L.; Basom R.; Delrow J. J.; Wang S.; et al. N(6)-methyladenosine mRNA marking promotes selective translation of regulons required for human erythropoiesis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10 (1), 4596. 10.1038/s41467-019-12518-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugo C.; Hugo C.; Pichler R.; Gordon K.; Schmidt R.; Amieva M.; Couser W. G.; Furthmayr H.; Johnson R. J. The cytoskeletal linking proteins, moesin and radixin, are upregulated by platelet-derived growth factor, but not basic fibroblast growth factor in experimental mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis. J. Clin Invest 1996, 97 (11), 2499–2508. 10.1172/JCI118697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G. H.; Shi Y.; Chen Y.; Sun M.; Sader S.; Maekawa Y.; Arab S.; Dawood F.; Chen M.; De Couto G.; et al. Gelsolin regulates cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction through DNase I-mediated apoptosis. Circ. Res. 2009, 104 (7), 896–904. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.172882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M.; Chen M.; Liu Y.; Fukuoka M.; Zhou K.; Li G.; Dawood F.; Gramolini A.; Liu P. P. Cathepsin-L contributes to cardiac repair and remodelling post-infarction. Cardiovasc. Res. 2011, 89 (2), 374–383. 10.1093/cvr/cvq328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer A.; Klein R. Multiple roles of ephrins in morphogenesis, neuronal networking, and brain function. Genes Dev. 2003, 17 (12), 1429–1450. 10.1101/gad.1093703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutjes A. W.; Nuesch E.; Reichenbach S.; Juni P. S-Adenosylmethionine for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, 4, CD007321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glorioso S.; Todesco S.; Mazzi A.; Marcolongo R.; Giordano M.; Colombo B.; Cherie-Ligniere G.; Mattara L.; Leardini G.; Passeri M.; et al. Double-blind multicentre study of the activity of S-adenosylmethionine in hip and knee osteoarthritis. Int. J. Clin Pharmacol Res. 1985, 5 (1), 39–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safavi S.; Larouche A.; Zahn A.; Patenaude A. M.; Domanska D.; Dionne K.; Rognes T.; Dingler F.; Kang S. K.; Liu Y.; et al. Erratum: The uracil-DNA glycosylase UNG protects the fitness of normal and cancer B cells expressing AID. NAR Cancer 2021, 3 (1), zcaa045. 10.1093/narcan/zcaa045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]