Abstract

The recent discovery of asymmetric arrangements of trimers in the tautomerase superfamily (TSF) adds structural diversity to this already mechanistically diverse superfamily. Classification of asymmetric trimers has previously been determined using X-ray crystallography. Here, native mass spectrometry (MS) and ultraviolet photodissociation (UVPD) are employed as an integrated strategy for more rapid and sensitive differentiation of symmetric and asymmetric trimers. Specifically, the unfolding of symmetric and asymmetric trimers initiated by collisional heating was probed using UVPD, which revealed unique gas-phase unfolding pathways. Variations in UVPD patterns from native-like, compact trimeric structures to unfolded, extended conformations indicate a rearrangement of higher-order structure in the asymmetric trimers that are believed to be stabilized by salt-bridge triads, which are absent from the symmetric trimers. Consequently, the symmetric trimers were found to be less stable in the gas phase, resulting in enhanced UVPD fragmentation overall and a notable difference in higher-order re-structuring based on the extent of hydrogen migration of protein fragments. The increased stability of the asymmetric trimers may justify their evolution and concomitant diversification of the TSF. Facilitating the classification of TSF members as symmetric or asymmetric trimers assists in delineating the evolutionary history of the TSF.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The tautomerase superfamily (TSF) is a mechanistically diverse superfamily1 in which different reactions (primarily tautomerization, hydrolytic dehalogenation, hydration, and decarboxylation) are catalyzed by different subgroup members using similar active-site machinery.2 Most notably, a unique catalytic N-terminal proline (Pro1) that can act as either a general acid or base is highly conserved across the more than 11,000 sequences identified in the TSF.2 4-Oxalocrotonate tautomerase (4-OT) in the 4-OT-like subgroup catalyzes the conversion of 2-hydroxymuconate to 2-oxo-3-hexenedioate3 and is considered the founding member of the TSF.2 As such, the β-α-β motif (Figure 1A) in the 4-OT structure is the basic building block in the five subgroups. Most proteins in the 4-OT-like subgroup are homohexamers with each subunit composed of a single β-α-β motif.4 Some are heterohexamers by which two β-α-β building blocks coded by different amino acid sequences form heterodimers, three of which then assemble to reach the heterohexameric assembly.5 A more recently discovered subset within the 4-OT-like subgroup has primary sequences that are twice the length (>100 amino acids) of standard 4-OT sequences (58–84 amino acids) with two β-α-β units, an N-terminal (N-unit) and C-terminal (C-unit), that are consecutively “fused” together with a flexible linker region.2 These fused 4-OT members along with the characterized members of the other four TSF subgroups form homotrimers.2

Figure 1.

(A) Each monomer of fused 4-OT family is composed of α (blue) and β units (red), each comprising a β-α-β motif joined by a linker region (gray). Representative crystal structures of trimers: (B) symmetric L2 (PDB: 5UNQ) and (C) asymmetric F4 (PDB: 6BLM) and (D) asymmetric R7 (PDB: 6VVM). N-terminal Pro residues are shown as spheres at each interface, which are labeled as N–C, N–N, or C–C. Each monomer is colored green, cyan, and magenta for subunits A, B, and C, respectively.

The TSF is an interesting example of how a single scaffold (i.e., the β-α-β motif) was repurposed to diversify activity.2 The predominance of this structural theme across the >11,000 homo- and heterohexamers and homotrimers suggests that a gene fusion event took place early in the evolutionary history of the TSF leading to the diversification of function that is seen today. The discovery of the fused 4-OTs further supports this hypothesis because they are possible progenitors for the trimeric arrangement seen in the other four subgroups in the TSF. Thus, further understanding of 4-OT trimers may reveal the evolution of the TSF.

The initial characterization of two fused 4-OT proteins with unique primary sequences from Burkholderia lata (“fused 4-OT” or “F4”) and Pusillimonas sp. (“linker 2” or “L2”) revealed yet another fascinating finding. There are two different quaternary arrangements of the two homotrimers: one symmetric and the other asymmetric.6 The symmetric form adopted by L2 is a head-to-tail arrangement of a homotrimer with three identical subunit interfaces, each containing the catalytic Pro1 of the N-unit interfacing with a C-unit of an adjacent subunit, shown in Figure 1B.6 The F4 trimer lacks this symmetry and instead forms an asymmetric trimer in which one subunit is flipped so that the trimer possesses three different interfaces with one containing a single Pro1 (N–C interface), another containing two Pro1 (N–N interface), and the third containing no Pro1 (C–C interface), shown in Figure 1C.6 The observation of this asymmetric trimer was the first for the TSF6 and is rare for homo-oligomers in general.7 The discovery of two different quaternary arrangements for the fused 4-OTs may provide an evolutionary advantage. If a fused 4-OT-like protein acted as a progenitor for the other four subgroups, then the asymmetric and symmetric structures could provide two different scaffolds and potentially different avenues for diversification. Because the asymmetry does not impair the enzymes’ fitness as 4-OTs, they can continue to function as such (converting 2-hydroxymuconate to 2-oxo-3-hexenedioate). The presence of the asymmetric trimer in the 4-OT subgroup suggests that, if the 4-OT indeed served as a template in the TSF, there might be asymmetric trimers in the other four subgroups. Work is ongoing to uncover such proteins that may have simply gone unnoticed to this point.

Recently, a study of the interfacial dynamics of F4 and L2 evaluated the hydrophobic and hydrophilic interactions stabilizing the asymmetric and symmetric forms.8 The solvent-free energy gain (ΔG) quantifying the contributions of hydrophobic interactions played only a modest role, while the formation of salt bridges is the deciding factor modulating the orientation of the fused forms of 4-OT proteins as confirmed by X-ray crystallography (XRC).8 In the same study, 133 sequences of 4-OT proteins were modeled as both symmetric and asymmetric trimers. More salt bridges (approximately 9 vs 5) were formed in one arrangement over another depending on the protein primary sequence. The structure with the most salt bridges is believed to be more thermodynamically stable, thus implying the structural diversification of the TSF. Experimental verification is desired to confirm the predicted stable forms for a large number of TSF sequences. Therefore, techniques that are amenable to high-throughput workflows are essential.

The intriguing formation and organization of salt bridges has motivated the exploration of new biophysical methods to further unveil the critical impact of these dynamic electrostatic interactions on the assembly and disassembly of proteins. Native mass spectrometry has emerged as a new technology for analysis of topologies and binding interactions of noncovalent macromolecular assemblies.9–12 Transfer of compact folded structures from solution to the gas phase can be achieved using nanoelectrospray ionization (nESI), and preservation of native-like molecular architectures has been confirmed using ion mobility spectrometry (IMS).13–16 IMS separates ions based on their size and shape and provides an extra dimension of conformational insight in addition to the mass and charge information provided by MS.16 Collision cross section (CCS) values can also be estimated from the decay of an ion population in Fourier transform mass analyzers,17–19 termed transient decay analysis (TDA). The nearly identical overall structures and cross sections of the tautomerase superfamily proteins inhibit separation of 4-OT proteins or differentiation based on size and shape alone. However, collision-induced unfolding (CIU) has proven to be useful for distinguishing protein assemblies that otherwise adopt similar structures based on their gas-phase unfolding pathways.16,20 CIU is a method in which low-energy collisional activation vibrationally “heats” protein ions, weakening the noncovalent interactions responsible for the protein higher-order structure and resulting in unfolding. Additionally, CIU can rapidly provide insight into the overall stability of gas-phase protein structures and changes thereof caused by formation or disruption of salt bridges and disulfide bonds, sequence mutations, or ligand binding with the aid of freely available data analysis programs.21,22 As shown herein, protein unfolding was monitored based on TDA measurement of collision cross sections to uncover differences in unfolding of the symmetric and asymmetric trimeric structures.

In addition to the conformational insight afforded from ion mobility and collision-induced unfolding methods, tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) sheds light on the disassembly process of multimeric protein complexes.23 Traditional collisional activated dissociation (CAD) and a beam-type CAD analog, higher energy collisional dissociation (HCD), of multimeric complexes release highly charged monomers consistent with protein unfolding and charge migration24–26 or heterolytic cleavage of salt bridge pairs prior to disassembly.27 Other ion activation methods, however, have shown to be sensitive to the native folding architecture of noncovalent protein complexes. For example, surface-induced dissociation (SID) generates subcomplexes representative of the biological arrangement of homo- and heterooligomers28–31 and is sensitive to protein unfolding, providing insight into the higher-order structure of gas-phase proteins.31–33 Both electron- and photon-based activation methods have been shown to localize regions of protein unfolding along the primary sequence and may reveal conformational changes with residue-specific detail based on variations in backbone cleavage sites for compact versus extended structures.34–39 Electron capture and electron transfer dissociation (ECD and ETD) cleave at surface-exposed regions of the protein backbone,34–36 and increased backbone fragmentation can improve characterization of large complex molecules37 and point to regions of greater flexibility as a result of unfolding.36,38 Ultraviolet photodissociation (UVPD) results in enhanced backbone cleavage when noncovalent bonds that stabilize secondary, tertiary, or quaternary structure are disrupted during unfolding.38,39 UVPD provides additional insight into charge migration and changes in secondary and tertiary structures.38

In the present study, integration of collision-induced unfolding, CCS measurements, and UVPD provides new insight into the conformations, organization, and interfacial interactions of three symmetric or asymmetric 4-OT trimers. Changes in UVPD sequence ion abundances, charge sites, and hydrogen migration trends as a function of protein unfolding are unique to the symmetry of the 4-OT trimers. A triad of hydrogen bonds and salt bridges in the asymmetric F4 and R7 trimers are presumed to act as a linchpin during unfolding, allowing structural rearrangements to stabilize gas-phase structures. The symmetric L2 trimer lacks this triad and is subsequently found to be more flexible and less stable as evidenced by extensive UVPD fragmentation. The trends for the F4, R7, and L2 trimers are then used to classify the quaternary arrangement of a fourth trimer, U6, which is proposed to adopt a symmetric structure based on the new results. This methodology provides an intriguing complement to XRC for identification of symmetric and asymmetric arrangements in the TSF and paves the way for adaptation toward higher throughput analyses of TSF trimers for determination of quaternary structures.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Sample Preparation.

Three 4-OT trimers (F4, L2, and R7) were expressed and purified as previously reported.2,6,8 The UniProt accession numbers for F4, L2, and R7 are Q392K7, F4GMX9, and A0A060NYR7, respectively. A fourth protein (designated U6, a member of the malonate semialdehyde decarboxylase (MSAD)-like subgroup) was prepared and purified as described in the Supporting Information. A bioinformatics analysis of the fused 4-OT subset (133 sequences) shows that one cluster, the one containing F4, R7, and 84 other sequences, has more salt bridges if the asymmetric trimer forms. The other cluster, containing L2 and 46 other sequences, has more salt bridges if the symmetric trimer forms.8 All function as 4-OTs and convert 2-hydroxymuconate to 2-oxo-3-hexenedioate. The primary sequences are shown in Table S1. Equine heart myoglobin and ammonium acetate were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Proteins were exchanged into 50 mM ammonium acetate solutions using P-6 Bio-Spin columns (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and diluted to a working concentration of <3 μM. Samples were loaded into borosilicate capillaries, pulled and coated in-house, and ionized using nanoelectrospray ionization (nESI) with spray voltages between 0.8 and 1.2 kV.

Mass Spectrometry.

A prototype Q Exactive Plus Ultra High Mass Range (UHMR) Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) equipped with a Coherent Excistar 193 nm ArF excimer laser (Santa Cruz, CA) was used for all analyses. A schematic of the instrumental setup is shown in Figure S1, and more details are provided in the Supporting Information. A variable temperature (vT) nanoelectrospray ionization (nESI) source was used to investigate the thermal stability of trimers in solution as discussed further in the Supporting Information. For collisional heating (collision-induced unfolding), collision voltages were applied in the injection flatapole ranging from −1 V (standard transmission; no unfolding) up to −160 V to induce various degrees of unfolding and disassembly of the gas-phase protein complexes. CCS measurements were carried out using transient decay analysis (TDA) in an Orbitrap analyzer as previously described19 with minor modifications involving implementation of xenon as the background gas in the Orbitrap mass analyzer as discussed further in Supporting Information and Figure S2. Nitrogen was used as the collision gas for all collisional heating experiments in the injection flatapole and is independent from the collision cell and Orbitrap analyzer collision gas.

UVPD was performed using nitrogen as the trapping gas with an Orbitrap resolution of 200,000. Protein ions were activated with a single laser pulse of 1.5 mJ as measured at the laser head from a 3 mm × 6 mm beam, which is subsequently trimmed with an iris prior to the HCD cell. Given the high divergence of the excimer laser and in the absence of focusing optics, it is anticipated that less than 20% of the laser beam intersects with the ions.

Data Analysis.

UVPD mass spectra were deconvoluted using the THRASH and Xtract algorithms in ProSightPC 4.1 and QualBrowser, respectively. THRASH results were utilized for the charge site analysis feature in UV-POSIT,40 while Xtract results were used for fragment abundance maps. All 10 UVPD fragment ion types (a, a + 1, b, c, x, x + 1, y, y − 1, Y, and z) were considered, while a and x-type fragments were utilized for most analyses as indicated. Custom MATLAB R2020a scripts were developed for automated averaging of replicate data and calculation of p values for comparison of significant changes in UVPD fragment ion abundances in various conditions. LcMsSpectator (https://github.com/PNNL-Comp-Mass-Spec/LCMS-Spectator) and a custom R script38 were utilized to calculated relative abundances of a, a + 1, and a + 2 ions as previously described. The average ratio of a and a + 1 ions for each protein was calculated from the summed abundances of all identified ions then averaged across replicate measurements. All crystal structure representations were prepared using PyMol (PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 2.4 Schrödinger, LLC).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Three 4-OT Proteins Display Similar Gas-Phase Unfolding and Disassembly Behaviors.

The conformations, disassembly, and interfacial interactions of three 4-OT proteins, F4, R7, and L2, each previously characterized using X-ray crystallography,2,6,8 were explored by a combination of native mass spectrometry strategies. Each of these fused 4-OT trimers is composed of three identical subunits that contain two β-α-β motifs, an N-unit and a C-unit, joined by a flexible linker as shown in Figure 1A. L2 adopts a symmetric trimeric assembly with three identical subunit interfaces, whereas F4 and R7 adopt an asymmetric trimeric assembly with three distinct interfaces. Their crystal structures are available in the Protein Data Bank (5UNQ,6 6BLM,6 and 6VVM,8 respectively) and are represented in Figure 1B–D. The three 4-OT proteins with solved structures were analyzed to establish trends in the gas-phase behavior prior to analysis of a fourth protein with unconfirmed structure as discussed below.

The nESI mass spectra of each of the proteins shown in Figure S3A display the trimers in a narrow charge state distribution centered around the 12+ charge state. The trimers were collisionally heated by applying variable collision energy (−40 to −120 V) to induce unfolding. Using a moderate collision voltage of −40 V, the signal abundance of trimers increases due to improved desolvation, which converts the more heterogeneous mixture of partially solvated trimers into a more homogeneous population of solvent- and adduct-free trimers (Figure S3B). Further increasing the collisional energy results in disassembly of the trimers into monomers and dimers (Figure S3C,D).

Following collisional heating, the collision cross sections (CCSs) of the 11+ charge state of each trimer were measured by transient decay analysis (TDA) in the Orbitrap analyzer.19 The CCSs of the native trimers (−1 V collisional heating) are between 3090 and 3290 Å2 (Figure S4 and Table S2). Applying greater collision energies (−20 to −140 V) caused protein unfolding as illustrated by the increase in CCS values in Figure S4, which is essentially a low-resolution CIU fingerprint. The increase in CCS occurs prior to ejection of subunits, which is initiated at collision energies of approximately −80 V (Figure S3C), supporting previous reports where protein unfolding precedes disassembly of multimeric complexes.24–26 Maximum CCS values greater than ~4500 Å2 are reached using a collisional voltage of −80 V and maintained until the precursor is fully depleted using voltages greater than −140 V. These observations are consistent for each of the three 4-OT proteins; thus, the symmetric versus asymmetric arrangements of the trimers cannot be differentiated based on their low-resolution collisional unfolding profiles alone.

Asymmetric Trimers Demonstrate Increased Stability Relative to Symmetric Arrangements.

Following confirmation that unfolding of the L2, F4, and R7 trimers was induced by collisional heating based on the increase in CCS, UVPD was used to probe the structures of the various compact and extended/unfolded conformations. Representative UVPD mass spectra of each of the trimers (11+ charge state) following variable collision heating are shown in Figure S5. In each mass spectrum, disassembly of trimers into monomers and dimers is observed along with a vast array of sequence ions, which are generated from covalent cleavage of the protein backbone. Examples of sequence maps showing the range of backbone cleavages upon UVPD are shown in Figure S6A–C. The average sequence coverages obtained by UVPD for each protein prior to and following collisional heating range from ~30% to 70% (Figure S6D). The insight obtained from the specific fragmentation patterns is discussed in more detail later.

Interestingly, the abundances of ejected subunits (i.e., monomers and dimers) observed in the UVPD mass spectra appear to decrease with increasing collisional heating, whereas the abundance of sequence ions remains fairly constant (Figure S5). To visualize these phenomena, the abundances of the ejected monomers as a fraction of the total fragment ion current are shown in Figure 2A for all three trimers. The monomer abundances exhibit a marked step decrease going from −40 to −80 V collisional energy, suggesting that a significant structural transition happens as a result of the collisional heating in this range as also supported by CCS results (Figure S4A). Decreased efficiency of oligomer disassembly following collisional heating and unfolding has been observed previously using SID and was attributed to a greater ability of the unfolded flexible protein to dissipate internal energy following activation relative to the compact native-like structure.32 Results herein suggest that UVPD (like SID) is also sensitive to the structural variations between the compact and extended/unfolded 4-OT trimers.

Figure 2.

Abundance of monomers (A, C) and identified sequence ions (B, D) as a fraction of the total ion abundance of the UVPD spectra (A, B) and HCD spectra (C, D) following variable collisional heating. A single 1.5 mJ pulse was used for UVPD spectra, and a 150 V collision energy was used for HCD. Representative spectra of asymmetric F4 using a variable-temperature nESI source (E) demonstrate increasing charge states with increasing temperature (remaining vT-nESI spectra can be found in Figure S9). (F) Average charge state of all 4-OT trimers as a function of the temperature. The melting curves were fit to a linear model with good agreement (R2 > 0.99).

The summed abundances of sequence ions generated upon UVPD demonstrate flatter profiles for each of the three timers in Figure 2B, suggesting that collisional heating does not impede the formation of sequence ions during disassembly of the trimers. However, the absolute sequence coverages of F4 and L2 obtained with UVPD do vary with the collision voltage and are higher for the extended 4-OT trimers (−80 V collision energy) compared to the compact trimers (−1 V collision energy) (Figure S6D). These results indicate that UVPD is sensitive to structural changes of the collisionally heated 4-OT proteins that alter the way energy is distributed following activation. The sequence coverage of the R7 trimer, however, remains fairly consistent with varying collisional heating and even decreases slightly at elevated collision energies (−40 and −80 V). A more detailed analysis of the UVPD fragmentation patterns is discussed below.

In comparison to UVPD, the trimers can alternatively be characterized using HCD (beam-type CAD), and the resulting MS/MS spectra are shown in Figures S7 and S8. Using lower-energy HCD conditions (100 V, Figure S7) results primarily in disassembly of the trimers (11+) with minimal production of sequence ions. Higher-energy HCD conditions (150 V, Figure S8) cause complete disassembly of the trimers into monomers and dimers along with some possible secondary dissociation of dimers and monomers into monomers and sequence ions. As displayed in Figure 2C,D, the abundances of ejected monomers and sequence ions generally remain consistent regardless of the level of collisional heating prior to HCD, in contrast to the UVPD results. Sequence coverages from HCD averaged from 34% to 57% for the three trimers.

The results shown in Figure 2 highlight another difference between the symmetric L2 and asymmetric F4 and R7 trimers regarding the abundance of product ions for each species. The increased abundances of ejected monomers from L2 relative to F4 and R7 using both UVPD and HCD (Figure 2A,C) suggest that the symmetric trimer is less stable and more prone to disassembly. This is also reflected in the elevated abundance of sequence ions for the L2 trimer by UVPD in Figure 2B. Decreased stability of the symmetric L2 trimer in the gas phase is mirrored by the lower thermal stability of the L2 trimer in solution as determined by variable-temperature nESI experiments (detailed in the Supporting Information) in which the distributions of charge states of the trimers are monitored as a function of the solution temperature (Figure S9) to create melting curves (Figure 2F). Representative spectra are shown in Figure 2E in which thermal instability is evidenced by a shift in the trimers to higher charge states, a well-established hallmark of protein unfolding (also shown in Figure S9).41–43 The slope of the melting curve, displayed in Figure 2F, for the symmetric L2 trimer was ~37% greater than the average slope of the asymmetric trimers, indicating accelerated thermal unfolding in solution. Increased stability of asymmetric trimers, both in solution and in the gas phase, has not yet been reported and could provide an evolutionary basis for the emergence of asymmetric arrangements. Further biochemical and biophysical studies are warranted to explore this behavior.

Figure 2 reveals that the symmetric L2 trimer is overall more prone to fragmentation, and examination of the detailed photodissociation patterns provides more granular insight based on location and abundances of all backbone cleavages from each trimer as visualized along the primary sequences in Figure S10. Although individual monomers within each trimer adopt a similar folding pattern with two β-α-β motifs joined by a flexible linker region, differences in the UVPD backbone cleavage maps of the asymmetric F4 and R7 trimers in Figure S10A,B and symmetric L2 trimer in Figure S10C are notable. Mirroring the trends in Figure 2C, the symmetric L2 trimer undergoes more efficient dissociation than the asymmetric F4 and R7 trimers as exhibited by the greater abundance of sequence ions (i.e., brighter heat map), particularly within the N-terminal half of the protein (residues 15–58). The greater sequence coverages obtained for the L2 trimer are also apparent and range from 49% using standard native transmission settings to 69% after collisional heating (−80 V). The asymmetric trimers display somewhat similar UVPD patterns to each other in terms of the breadth of backbone cleavages throughout the protein sequence. Total sequence coverages were more limited for F4 and R7, ranging from 28% to 57% for F4 and from 36% to 48% for R7 depending on the level of collisional heating prior to UVPD. For all three trimers, prominent fragmentation occurred in the middle of the protein sequence between residues 38–49 and 54–72. The latter region falls within the flexible linker regions (horizontal gray bars, Figure S10), supporting the notion that UVPD results in sequence ions primarily in flexible areas of proteins not stabilized by extensive noncovalent interactions. In contrast to UVPD, HCD yielded sequence ions primarily localized to preferential cleavages of C-terminal to acidic residues (Asp, Glu) and N-terminal to Pro residues (Figure S11).

UVPD Fragmentation Localizes Unfolding Regions in Higher-Order Protein Structures.

The structural sensitivity of UVPD is afforded by the high-energy deposition that may result in cleavage of any bond in the protein backbone to produce a, a + 1, b, c, x, x + 1, y, y − 1, Y, and z ions, displayed in Figure S12. Unique to UVPD are a, a + 1, x, and x + 1 ions that are believed to arise from fast direct dissociation following photon absorption and transition of an electron of the protein to an excited electronic state.44 Other types of fragment ions, including b and y ions, are produced following intramolecular vibrational energy redistribution (IVR) after internal conversion of the excited electronic state to the ground electronic state,44 meaning that these ions likely originate after disruption of noncovalent interactions that occurs preferentially during IVR. The abundances of a, a + 1, x, and x + 1 ions are thus more sensitive to variations in noncovalent interactions (e.g., protein unfolding) because these a/x ions may retain noncovalent signatures that are otherwise disrupted during IVR processes.38,45 For UVPD, backbone fragmentation can be suppressed if networks of noncovalent interactions prevent nascent a and x ions from separating and being detected. Thus, enhancement in UVPD fragment abundances upon protein denaturation (whether in solution or in the gas phase) serves as evidence for the disruption of noncovalent interactions that might otherwise prevent the release of fragment ions.38,39

Changes in abundances of sequence ions produced by UVPD as a function of unfolding from collisional heating may reveal changes in higher-order structures of proteins.38,45 The loss of higher-order structure using a collision heating energy of at least −80 V results in a shift in the abundance of the various ion types as a function of the collision voltage (Figure S12), suggesting a change in the way energy is distributed throughout the protein during UVPD for the native-like versus collisionally unfolded trimers. Figure 3A–C displays the locations and magnitudes of significant changes (p value <0.02) in the backbone cleavage sites along the primary sequence of the 4-OT trimers based on the abundances of a- and x-type ions produced by UVPD with and without collisional heating. A total of 31 significant changes in sequence ion abundances were observed for the F4 trimer following collisional heating. An overall increase in fragmentation was observed for the extended trimer, expressed as mostly positive values in Figure 3A. This observation supports the hypothesis that collisional heating disrupts noncovalent interactions of the native trimer leading to a more efficient release of UVPD fragments. To visualize the regions of unfolding or conformational reorganization, the crystal structure of the F4 trimer was colorized in Figure 3D to reflect the results shown in Figure 3A. The greatest enhancements in UVPD fragmentation upon collisional heating of the F4 trimer are localized within the two α-helical regions (residues 12–37 and 77–102) and to the linker region (residues 46–65) between the two β-α-β motifs. The increased fragment abundance generated from the α-helical regions suggests that their networks of hydrogen bonding are disrupted upon collisional heating. The linker region is flexible with minimal secondary structure; however, short sections of β-strands (50–52 and 55–56) and an α-helix (58–60) are observed in the crystal structure (Figure 3D), and their loss of hydrogen bonding during collisional heating may contribute to the enhanced UVPD in that region.

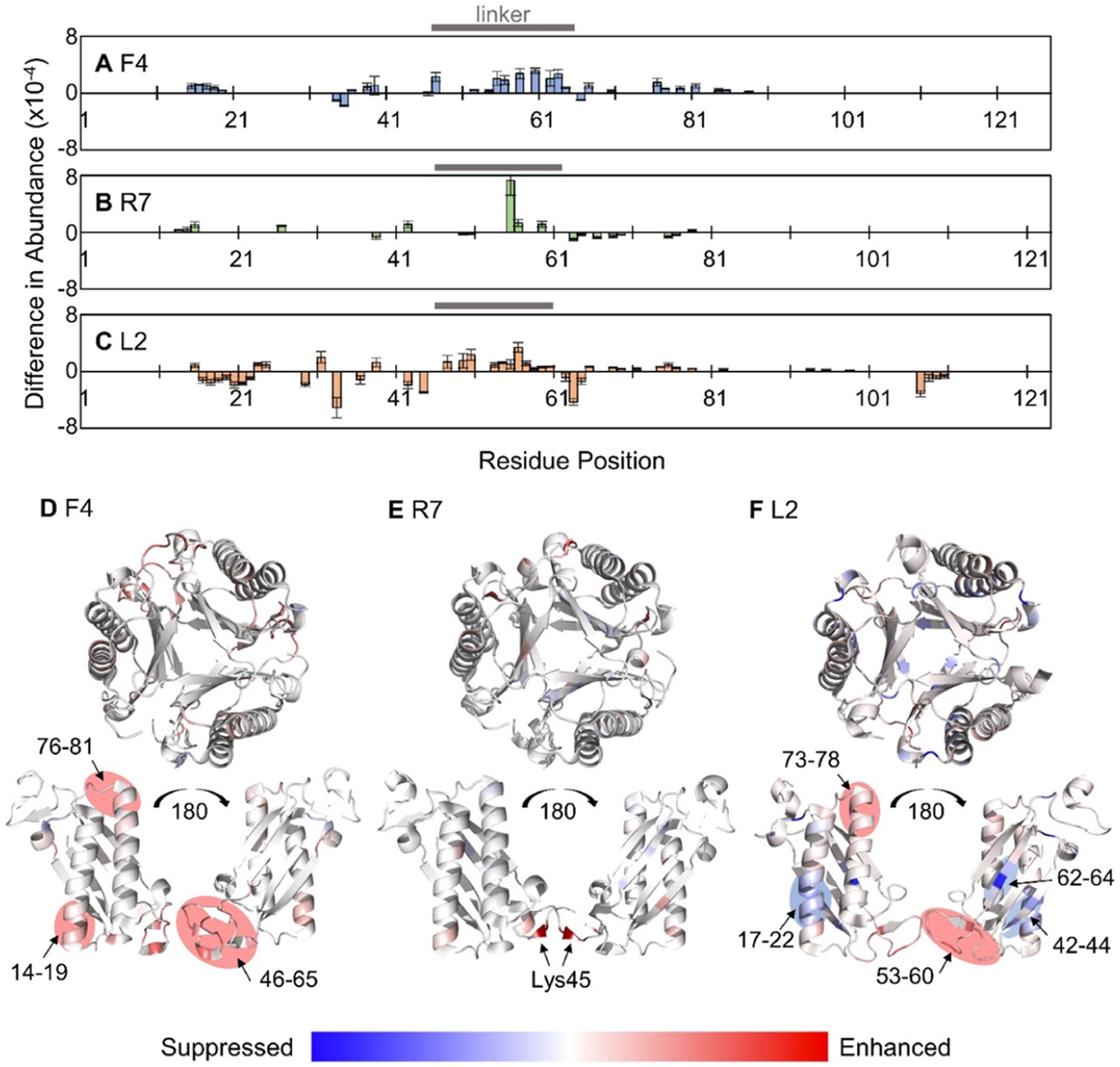

Figure 3.

Significant differences (p value < 0.02) in the backbone cleavage sites based on the summed abundances of a/x-type ions generated from UVPD (1 pulse, 1.5 mJ) of compact trimers (standard transmission) versus extended trimers (−80 V collisional heating) for (A) F4, (B) R7, and (C) L2 trimers (11+ charge state). Positive values indicate enhancement of UVPD fragmentation following collisional heating, and negative values indicate suppression. Linker regions are indicated with a horizontal bar. Crystal structures of (D) F4 (PDB: 6BLM), (E) R7 (PDB: 6VVM), and (F) L2 (PDB: 5UNQ) are colored to represent the results in A–C with blue regions indicating suppression and red regions indicating enhancement of UVPD for the extended (unfolded) trimers after collisional heating

The relatively low sequence coverage of the R7 trimer afforded when considering only a and x ions limited the number (17 cleavage sites) and magnitude of significant differences in UVPD that were observed between the compact and extended structures of the asymmetric R7 trimer (Figure 3B). This observation is echoed in Figure 3E with only one backbone cleavage site, between residues Lys55 and Pro56, indicating a notable change in fragmentation efficiency. This pair of residues is located in the linker region (46–61), similar to one of the sections of enhanced fragmentation for the asymmetric F4 trimer. Cleavages of N-terminal to Pro residues such as this one are specific preferential cleavages also observed upon HCD,46 often most prominently observed for b and y ions.45 Here, the enhanced Pro cleavage is observed for the a55 + 1 ion.

Upon UVPD, the symmetric L2 trimer exhibited the greatest number of significant changes (47) in the abundances of a and x ions following collisional heating with a distribution of suppressed and enhanced fragmentation (Figure 3C). The linker region of L2 (residues 46–60) experiences similar enhancements in UVPD following collisional heating (Figure 3F) as was observed for the asymmetric F4 and R7 trimers. Some unfolding and disruption of noncovalent interactions of the second α-helix (residues 72–92) are also observed upon collisional heating, mimicking trends for the F4 trimer. Suppression of UVPD of the L2 trimer upon collisional heating was localized to the first α-helix (12–37) and two β-strands (39–45 and 61–68). Further discussion of these results is included in the Supporting Information. The unfolding trends of the symmetric and asymmetric trimers noted in Figure 3 are unique and thus may provide criteria for differentiation and classification of other TSF trimers.

Evidence of Intersubunit Salt-Bridge Rearrangement in Symmetric Trimers Following Collisional Heating.

In addition to the structural insight provided by the abundances and distribution of a-type ions produced upon UVPD, these ions have been previously utilized to estimate the locations of charge sites of proteins. Charge site analysis (CSA) uses step changes in charge states of a and a + 1 fragment ions to determine the proton location along the protein backbone.51 CSA was performed for the three 4-OT trimers, and the charge states of all a-type ions are displayed in Figure 4. CSAs for the two asymmetric trimers in Figure 4A,B are similar and exhibit discrete changes in a-ion charge states for both proteins, though somewhat less comprehensive for R7 beyond residue 81 due to the decreased number of a and a + 1 ions. Minor “tailing” is observed upon collisional heating (−80 V for R7 and −40 V for F4), possibly resulting from more mobile protons in the flexible linker regions (which are demarcated with horizontal gray bars, Figure 4). However, the step changes observed for the two asymmetric proteins provide confidence in assigning protonation sites, which are localized primarily to basic residues summarized in Table S3. No fragments smaller than a12 were observed for the 4-OT trimers; thus, the first charge site may be located anywhere from the N-terminus to the basic His11 residue. One interesting note is the absence of any observed charged sites located at basic residues that are involved in intermolecular salt bridges (as determined from crystal structures) for the two asymmetric trimers. Salt-bridge pairs are listed in Table S4 and indicated in Figure 4 with black boxes above the sequences. The absence of protons at these sites supports the preservation of salt bridges and is consistent with transfer of native-like structures of F4 and R7 into the gas phase. The similarity in charge sites for the F4 and R7 trimers without or with supplemental collisional heating suggests that the protons remain relatively immobile and/or ion pairs are not disrupted during the unfolding or structural reorganization that occurs during collisional heating.

Figure 4.

Charge states of summed a and a + 1 ions generated from UVPD (1 pulse, 1.5 mJ) following variable collisional heating for the (A) F4, (B) R7, and (C) L2 trimers (11+). Black boxes above each graph denote locations of residues involved in intermolecular salt bridges from the crystal structures listed in Table S4; solid black boxes indicate locations of basic residues, and open boxes indicate acidic residues. The horizontal gray bars above each graph indicate the location of the linker region in the primary sequence.

More gradual shifts in charge states of a-type ions rather than clearly defined step changes are seen in Figure 4C for the symmetric L2 trimer. This “tailing” has been attributed to the presence of multiple protonated forms and mobilization of protons along the backbone during ion activation, allowing the production of product ions in a broader range of charge states (as prominently observed for the section covering residues 39–71). Migration of protons following collisional heating is especially notable for the L2 trimer. A single set of charge assignments is not suitable to describe the possible charge sites for the compact and elongated conformations of the symmetric trimer in Table S3. Instead, two sets of dominant charge site locations are determined, denoted as L2 and L2′, respectively. The ambiguity in charge localization stems from the detection of a-type ions in a mixture of 2+, 3+, and 4+ charge states in the center of L2 between residues Arg39 and Arg71 and their subsequent shifts following collisional heating. Of note is the increased relative abundance of the a393+ ion compared to the a392+ ion in Figure 4C suggesting that the protonation of Arg39 becomes prominent following collisional heating (−80 V). Protonation of Arg39 in the L2 trimer suggests that the Arg39/Glu97 salt-bridge pair that is present in the crystal structure is either (1) cleaved homolytically during activation (via collisions or photons) followed by sequestration of a mobile proton at Arg39 (Scheme S1A), (2) cleaved heterolytically during activation, inherently resulting in retention of a proton at Arg39 (and negative charge at Glu97, Scheme S1B), or (3) not preserved at all upon transfer of the L2 trimer into the gas phase, allowing protonation of Arg39 in the ESI droplet. Homolytic salt-bridge cleavage during UVPD followed by charge migration is unlikely given the fast generation of a- and x-type ions from excited electronic states that precedes any proton motion.44 Homolytic cleavage during collisional activation is also unlikely given the slow heating mechanism of dissociation and the elevated energy barrier for homolytic ion pair cleavage.27 Finally, the CCS values of the L2 trimers (without collisional heating) suggest compact structures, offering evidence of preservation of the Arg39/Glu97 salt bridge. As noted above, the observed shift in protonation from His59 to Arg39 (Figure 4C) is enhanced upon collisional heating. Based on these observations, we postulate that the shift in the charge site pattern of the L2 trimer indicates initial preservation of salt bridges in solution and transfer to the gas phase by ESI; however, subsequent collisional heating in the gas phase (during CIU) disrupts the linker region and ruptures the Arg39/Glu97 salt bridge, resulting in proton sequestration at Arg39. This effect may not be observed for the asymmetric F4 and R7 trimers owing to the paucity of salt bridges in their linker regions or their greater observed stability in the gas-phase.

Stability of Asymmetric Trimers Is Attributed to Unique Salt-Bridge Arrangements.

The secondary and tertiary structures of each subunit for the three 4-OT trimers are nearly identical (Figure 1); thus, the unique photo-fragmentation patterns must be driven by differences in quaternary structure.4,5 The formation of a symmetric or asymmetric quaternary structure is ultimately governed by the number of intersubunit salt bridges, listed in Table S4,8 and believed to be the driving force behind the observation of increased stability of the asymmetric trimers. The asymmetric arrangement of these 4-OT trimers allows engagement of a more intricate network of intersubunit polar contacts. In particular, the F4 trimer contains a salt bridge triad involving Glu04B and Glu04C residues and Lys108A plus two Thr43 residues (subunits B and C) joining in via hydrogen bonds in the central cavity of the trimer as shown in Figure 5A. The R7 trimer contains intersubunit hydrogen bonds involving all three subunits between one Glu04C, Lys104A, and two Tyr06 residues (subunits B and C, Figure 5B). Based on sequence similarity with F4 and salt bridges listed in Table S4a, Glu04B should also be involved in coordination with Lys104A in R7, but it is not directly observed in the crystal structure (PDB: 6VVM). However, rotation of Glu04B in solution should allow it to form a salt bridge, which could be retained in the gas phase. The symmetric L2 trimer does not engage in any intersubunit polar contacts that involve all three subunits as indicated by the absence of polar contacts in the central cavity of the trimer in Figure 5C.

Figure 5.

All intersubunit polar contacts for the (A) F4, (B) R7, and (C) L2 trimers are shown as dashed gray lines identified in PyMol. Residues that are engaged in salt bridges and hydrogen bond networks are represented as sticks in all three protein subunits colored green (subunit A), cyan (subunit B), and magenta (subunit C). No such networks are present in C as evidenced by the lack of polar contacts in the cavity of the symmetric L2 trimer.

The strengths of the triad of hydrogen bonds and salt bridges that stabilize the asymmetric F4 and R7 trimers in solution likely increase in the hydrophobic environment of the gas phase, thus accounting for the increased stability relative to the symmetric L2 trimer. Along with the presence of two additional salt bridges, Asp13/Arg123 and Lys16/Asp114, at the N–N interface (Table S4), the polar interactions involving Glu04 may also explain the scarcity of sequence ions generated along the N-terminal α-helix of the asymmetric trimers (residues 12–37 in Figure S10A,B). In essence, this extensive network of noncovalent interactions may prevent the efficient release of fragment ions from this α-helix region during disassembly of the F4 and R7 trimers.

UVPD a-Type Ions Reflect Greater Intersubunit Interactions in Asymmetric Trimers.

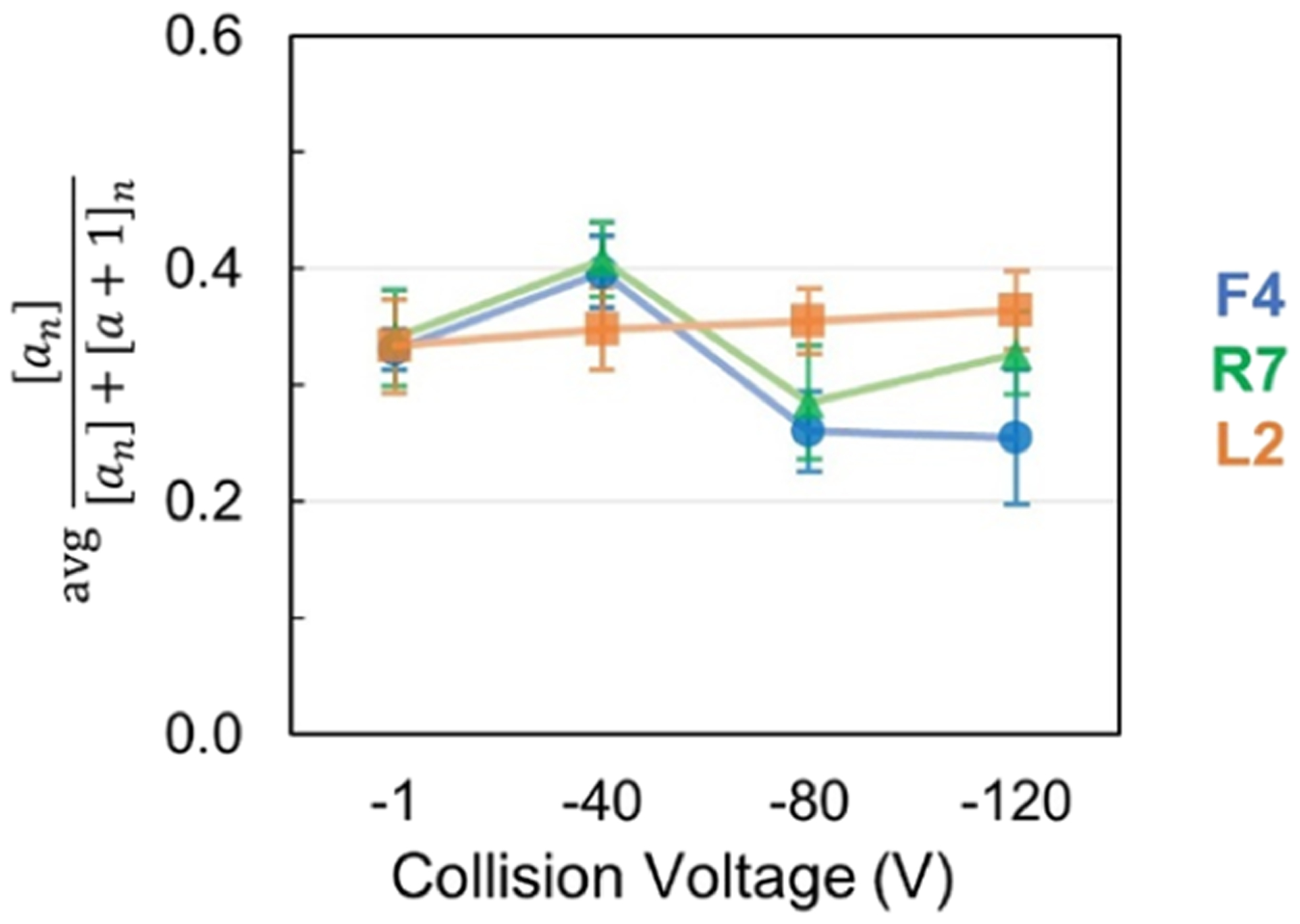

Another unique feature afforded by the a-type ions generated from UVPD is the ability to infer higher-order structure from the distribution of a versus a + 1 ions. Odd-electron a + 1 ions generated by UVPD may decay into a ions, but the engagement of amino acids in hydrogen-bonding interactions, such as ones involved in β-sheets or α-helices, may stabilize the a + 1 radicals and enhance their preservation and prevalence.47,48 Here, hydrogen elimination monitoring (HEM) was carried out by tracking a ion abundance as a percentage of total a and a + 1 ion abundance as previously described to evaluate the structural reorganization of the symmetric and asymmetric trimers during gas-phase unfolding.38

Results of HEM analysis are summarized in Figure 6 and shown with per-residue resolution in Figure S13. Interestingly, the HEM results for the asymmetric F4 and R7 trimers show a rather marked transition that occurs with collisional heating (going from a voltage of −40 to −80 V), supporting observations of a rearrangement in protein structure. Overall, the portion of a ions decreases and a + 1 ions become more dominant as the asymmetric trimers are collisionally heated. This trend implies the formation of higher-order structural features (i.e., hydrogen bonds or salt bridges) that stabilize the a + 1 ions and suppress their conversion to a ions. Examples of isotope distributions of specific a ions are shown in Figure S13D,E.

Figure 6.

Average fraction of a ion abundance relative to the total a and a + 1 ion abundance for the three trimers (11+ charge state) upon UVPD as a function of collisional heating.

The disparity in HEM between symmetric L2 and asymmetric F4 and R7 trimers suggests a difference in gas-phase unfolding of L2 that does not result in a formation of hydrogen bonds or ion pairs as compared to F4 and R7 trimers. The increased stability of the asymmetric trimers may allow greater opportunity for structural rearrangement that is responsible for the decrease in the portion of a-type ions and enhancement of a + 1 ions for the trimers after collisional heating (Figure 6). Lack of these stabilizing quaternary interactions in the symmetric L2 trimer, particularly in the N-terminal region, may preclude its ability to attain structural intermediates that are responsible for the UVPD trends observed for the asymmetric F4 and R7 trimers, which include suppressed fragmentation (Figure 3), limited charge migration (Figure 4), and structural shift in HEM (Figure 6).

Characterization of a Trimer with an Unconfirmed Quaternary Structure.

To evaluate the utility of CIU-UVPD-MS for predicting quaternary structural arrangements, characterization of trimer symmetry was undertaken for a fourth protein, U6 (sequence in Table S1). U6 is not a 4-OT subgroup member, but rather a member of the malonate semialdehyde decarboxylase (MSAD)-like subgroup of the TSF, which also forms trimers. A crystal structure has not been reported, but U6 is believed to adopt a symmetric quaternary structure.

Representative mass spectra of the U6 trimer obtained by nESI in conjunction with collisional heating are shown in Figure S14A. Production of subcomplexes (monomers and dimers) from the U6 trimer following collision heating voltages of −80 and −120 V indicates that the trimers are indeed unfolding. The U6 trimer was subjected to UVPD (1 pulse, 1.5 mJ) and produced the spectra shown in Figure S14B. The U6 trimer readily dissociates into subcomplexes and sequence ions upon UVPD following no or low collisional heating (−1 and −40 V). When subjected to greater collisional heating (−80 and −120 V), sequence ions are most abundant and yield sequence coverages up to 86%. The backbone cleavage map in Figure S15A in many ways mirrors the fragmentation behavior of the symmetric L2 trimer (Figure S10C) with particularly prominent backbone cleavages along the N-terminal half of the sequence as well as part of the C-terminus (residues above 100). Overall, the fragmentation for the unfolded trimers (collision voltages −80 to −120 V) is increased relative to the native trimer (−1 V). The changes in UVPD patterns as a function of collisional heating are further visualized by a difference plot in Figure S15B, which compares the abundance of a- and x-type ions generated from the U6 trimer without and with supplemental collisional heating (−80 V). The greatest increases in fragmentation following collisional heating are localized in the middle of the primary sequence, between residues 36 and 81, which encompasses the putative location of the flexible linker and the region most prone to unfolding. Fragmentation is suppressed in a narrow region between residues 28 and 35, similar to suppression noted for the first α-helix of the L2 trimer (residues 17–22 in Figure 3C,F), and is rationalized in an identical manner.

Among all sequence ions identified upon UVPD of the U6 trimers, a and a + 1 ions make up the vast majority (Figure S16A), facilitating charge site analysis and hydrogen elimination monitoring. Charge site analysis of the 13+ charge state (Figure S16C) exhibits substantial “tailing” with an overlap of the different charge states of a and a + 1 ions. The tailing decreases with increasing collisional heating, which is consistent with the presence of multiple protonated forms and mobilization of protons following cleavage of salt bridges as also proposed for the symmetric L2 trimer (Figure 4C). The locations of intersubunit salt bridges of the U6 trimer are not known owing to the lack of a crystal structure. The overall distribution of a-type ions relative to all a ions (a and a + 1) remains nearly unchanged as a function of collisional heating (Figure S16B,D), a trend consistent with the behavior noted earlier for the symmetric L2 trimer. The combination of these results supports the proposed symmetric quaternary assembly of the U6 trimer.

CONCLUSIONS

The collision-induced unfolding of three trimers in the 4-OT subgroup of the tautomerase superfamily was characterized using UVPD and native MS. The fragmentation of the two asymmetric trimers, F4 and R7, was more restricted than that of L2, which is attributed to the network of noncovalent interactions that define the higher-order structures of the native-like ions, which includes salt-bridge triads that act as linchpins in the gas phase. Collisional heating prompted structural reorganization of the asymmetric trimers as observed from increased UVPD fragment abundances in regions of unfolding, primarily located along the linker region between two β-α-β motifs. Changes in a and a + 1 ion distributions from compact to extended structures were also observed for the asymmetric trimers, suggesting the formation of new noncovalent interactions in the gas-phase structures. While collisional heating of the symmetric trimer, L2, also resulted in restructuring and unfolding along the linker region, the absence of any salt-bridge triads mitigated the rearrangement of noncovalent interactions as dissociation to sequence ions was more prominent and shifts in hydrogen elimination of the a + 1 ions were less prominent. UVPD trends for the fourth trimer in the TSF, U6, mimicked those observed for L2, prompting classification of the protein’s quaternary arrangement as symmetric. The vital role that salt bridges play in the current study supports previous work8 that determined that these ionic interactions are more important than other polar or hydrophobic interactions that might stabilize subunit interactions for determining quaternary arrangement. The approach detailed herein allows for the potential for incorporation into a high-throughput workflow by coupling UVPD and collisional heating following native separations, such as size exclusion chromatography (SEC)49 or online buffer exchange (OBE).50

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants no. GM-129331 to C.P.W. and no. R35GM139658 to J.S.B. and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (no. F-1155 to J.S.B.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.2c03564.

Sequence and structural information of 4-OT proteins, sample preparation of the MSAD proteins, all nESI and MS/MS mass spectra, results and summaries of UVPD analysis including fragment maps and hydrogen elimination monitoring, and methods and results from thermal denaturation (vT-nESI) and CCS measurements (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/jacs.2c03564

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Sarah N. Sipe, Department of Chemistry, University of Texas, Austin, Texas 78712, United States

Emily B. Lancaster, Division of Chemical Biology and Medicinal Chemistry, College of Pharmacy, University of Texas, Austin, Texas 78712, United States

Jamie P. Butalewicz, Department of Chemistry, University of Texas, Austin, Texas 78712, United States

Christian P. Whitman, Division of Chemical Biology and Medicinal Chemistry, College of Pharmacy and Institute for Cellular and Molecular Biology, University of Texas, Austin, Texas 78712, United States;.

Jennifer S. Brodbelt, Department of Chemistry, University of Texas, Austin, Texas 78712, United States;.

REFERENCES

- (1).Gerlt JA; Babbitt PC Divergent Evolution of Enzymatic Function: Mechanistically Diverse Superfamilies and Functionally Distinct Suprafamilies. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2001, 70, 209–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Davidson R; Baas B-J; Akiva E; Holliday GL; Polacco BJ; LeVieux JA; Pullara CR; Zhang YJ; Whitman CP; Babbitt PC A Global View of Structure–Function Relationships in the Tautomerase Superfamily. J. Biol. Chem 2018, 293, 2342–2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Harayama S; Rekik M; Ngai KL; Ornston LN Physically Associated Enzymes Produce and Metabolize 2-Hydroxy-2,4-Dienoate, a Chemically Unstable Intermediate Formed in Catechol Metabolism via Meta Cleavage in Pseudomonas Putida. J. Bacteriol 1989, 171, 6251–6258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Subramanya HS; Roper DI; Dauter Z; Dodson EJ; Davies GJ; Wilson KS; Wigley DB Enzymatic Ketonization of 2-Hydroxymuconate: Specificity and Mechanism Investigated by the Crystal Structures of Two Isomerases. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 792–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Whitman CP The 4-Oxalocrotonate Tautomerase Family of Enzymes: How Nature Makes New Enzymes Using a β−α−β Structural Motif. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 2002, 402, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Baas B-J; Medellin BP; LeVieux JA; de Ruijter M; Zhang YJ; Brown SD; Akiva E; Babbitt PC; Whitman CP Structural, Kinetic, and Mechanistic Analysis of an Asymmetric 4-Oxalocrotonate Tautomerase Trimer. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 2617–2627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Goodsell DS; Olson AJ Structural Symmetry and Protein Function. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct 2000, 29, 105–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Medellin BP; Lancaster EB; Brown SD; Rakhade S; Babbitt PC; Whitman CP; Zhang YJ Structural Basis for the Asymmetry of a 4-Oxalocrotonate Tautomerase Trimer. Biochemistry 2020, 59, 1592–1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Loo JA Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry: A Technology for Studying Noncovalent Macromolecular Complexes. Int. J. Mass Spectrom 2000, 200, 175–186. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Liko I; Allison TM; Hopper JT; Robinson CV Mass Spectrometry Guided Structural Biology. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 2016, 40, 136–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Boeri Erba E; Signor L; Petosa C Exploring the Structure and Dynamics of Macromolecular Complexes by Native Mass Spectrometry. J. Proteomics 2020, 222, 103799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Karch KR; Snyder DT; Harvey SR; Wysocki VH Native Mass Spectrometry: Recent Progress and Remaining Challenges. Annu. Rev. Biophys 2022, 51, 157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Konijnenberg A; Butterer A; Sobott F Native Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry and Related Methods in Structural Biology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 2013, 1834, 1239–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).McCabe JW; Hebert MJ; Shirzadeh M; Mallis CS; Denton JK; Walker TE; Russell DH The Ims Paradox: A Perspective on Structural Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry. Mass Spectrom. Rev 2021, 40, 280–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Ruotolo BT Collision Cross Sections for Native Proteomics: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Proteome Res 2022, 21, 2–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Ben-Nissan G; Sharon M The Application of Ion-Mobility Mass Spectrometry for Structure/Function Investigation of Protein Complexes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2018, 42, 25–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Wobschall D; Graham JR; Malone DP Ion Cyclotron Resonance and the Determination of Collision Cross Sections. Phys. Rev 1963, 131, 1565–1571. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Makarov A; Denisov E Dynamics of Ions of Intact Proteins in the Orbitrap Mass Analyzer. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2009, 20, 1486–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Sanders JD; Grinfeld D; Aizikov K; Makarov A; Holden DD; Brodbelt JS Determination of Collision Cross-Sections of Protein Ions in an Orbitrap Mass Analyzer. Anal. Chem 2018, 90, 5896–5902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Dixit SM; Polasky DA; Ruotolo BT Collision Induced Unfolding of Isolated Proteins in the Gas Phase: Past, Present, and Future. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2018, 42, 93–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Polasky DA; Dixit SM; Fantin SM; Ruotolo BT CIUSuite 2: Next-Generation Software for the Analysis of Gas-Phase Protein Unfolding Data. Anal. Chem 2019, 91, 3147–3155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Migas LG; France AP; Bellina B; Barran PE ORIGAMI: A Software Suite for Activated Ion Mobility Mass Spectrometry (AIM-MS) Applied to Multimeric Protein Assemblies. Int. J. Mass Spectrom 2018, 427, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Zhou M; Lantz C; Brown KA; Ge Y; Paša-Tolić L; Loo JA; Lermyte F Higher-Order Structural Characterisation of Native Proteins and Complexes by Top-down Mass Spectrometry. Chem. Sci 2020, 11, 12918–12936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Jurchen JC; Williams ER Origin of Asymmetric Charge Partitioning in the Dissociation of Gas-Phase Protein Homodimers. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 2817–2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Benesch JLP; Aquilina JA; Ruotolo BT; Sobott F; Robinson CV Tandem Mass Spectrometry Reveals the Quaternary Organization of Macromolecular Assemblies. Chem. Biol 2006, 13, 597–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Zhou M; Dagan S; Wysocki VH Impact of Charge State on Gas-Phase Behaviors of Noncovalent Protein Complexes in Collision Induced Dissociation and Surface Induced Dissociation. Analyst 2012, 138, 1353–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Loo RRO; Loo JA Salt Bridge Rearrangement (SaBRe) Explains the Dissociation Behavior of Noncovalent Complexes. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2016, 27, 975–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Ma X; Zhou M; Wysocki VH Surface Induced Dissociation Yields Quaternary Substructure of Refractory Noncovalent Phosphorylase B and Glutamate Dehydrogenase Complexes. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2014, 25, 368–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Quintyn RS; Yan J; Wysocki VH Surface-Induced Dissociation of Homotetramers with D2 Symmetry Yields Their Assembly Pathways and Characterizes the Effect of Ligand Binding. Chem. Biol 2015, 22, 583–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Sahasrabuddhe A; Hsia Y; Busch F; Sheffler W; King NP; Baker D; Wysocki VH Confirmation of Intersubunit Connectivity and Topology of Designed Protein Complexes by Native MS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2018, 115, 1268–1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Snyder DT; Harvey SR; Wysocki VH Surface-Induced Dissociation Mass Spectrometry as a Structural Biology Tool. Chem. Rev 2021, 7442–7487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Quintyn RS; Zhou M; Yan J; Wysocki VH Surface-Induced Dissociation Mass Spectra as a Tool for Distinguishing Different Structural Forms of Gas-Phase Multimeric Protein Complexes. Anal. Chem 2015, 87, 11879–11886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Harvey SR; Yan J; Brown JM; Hoyes E; Wysocki VH Extended Gas-Phase Trapping Followed by Surface-Induced Dissociation of Noncovalent Protein Complexes. Anal. Chem 2016, 88, 1218–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Geels RBJ; van der Vies SM; Heck AJR; Heeren RMA Electron Capture Dissociation as Structural Probe for Noncovalent Gas-Phase Protein Assemblies. Anal. Chem 2006, 78, 7191–7196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Li H; Nguyen HH; Ogorzalek Loo RR; Campuzano IDG; Loo JA An Integrated Native Mass Spectrometry and Top-down Proteomics Method That Connects Sequence to Structure and Function of Macromolecular Complexes. Nat. Chem 2018, 10, 139–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Zhang H; Cui W; Wen J; Blankenship RE; Gross ML Native Electrospray and Electron-Capture Dissociation FTICR Mass Spectrometry for Top-Down Studies of Protein Assemblies. Anal. Chem 2011, 83, 5598–5606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Gadkari VV; Ramírez CR; Vallejo DD; Kurulugama RT; Fjeldsted JC; Ruotolo BT Enhanced Collision Induced Unfolding and Electron Capture Dissociation of Native-like Protein Ions. Anal. Chem 2020, 92, 15489–15496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Zhou M; Liu W; Shaw JB Charge Movement and Structural Changes in the Gas-Phase Unfolding of Multimeric Protein Complexes Captured by Native Top-Down Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem 2020, 92, 1788–1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Theisen A; Black R; Corinti D; Brown JM; Bellina B; Barran PE Initial Protein Unfolding Events in Ubiquitin, Cytochrome c and Myoglobin Are Revealed with the Use of 213 Nm UVPD Coupled to IM-MS. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2019, 30, 24–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Rosenberg J; Parker WR; Cammarata MB; Brodbelt JS UV-POSIT: Web-Based Tools for Rapid and Facile Structural Interpretation of Ultraviolet Photodissociation (UVPD) Mass Spectra. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2018, 29, 1323–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).El-Baba TJ; Woodall DW; Raab SA; Fuller DR; Laganowsky A; Russell DH; Clemmer DE Melting Proteins: Evidence for Multiple Stable Structures upon Thermal Denaturation of Native Ubiquitin from Ion Mobility Spectrometry-Mass Spectrometry Measurements. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 6306–6309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Woodall DW; Henderson LW; Raab SA; Honma K; Clemmer DE Understanding the Thermal Denaturation of Myoglobin with IMS-MS: Evidence for Multiple Stable Structures and Trapped Pre-Equilibrium States. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2021, 32, 64–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).McCabe JW; Shirzadeh M; Walker TE; Lin C-W; Jones BJ; Wysocki VH; Barondeau DP; Clemmer DE; Laganowsky A; Russell DH Variable-Temperature Electrospray Ionization for Temperature-Dependent Folding/Refolding Reactions of Proteins and Ligand Binding. Anal. Chem 2021, 93, 6924–6931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Julian RR The Mechanism Behind Top-Down UVPD Experiments: Making Sense of Apparent Contradictions. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2017, 28, 1823–1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Macias LA; Sipe SN; Santos IC; Bashyal A; Mehaffey MR; Brodbelt JS Influence of Primary Structure on Fragmentation of Native-Like Proteins by Ultraviolet Photodissociation. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2021, 32, 2860–2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Wysocki VH; Tsaprailis G; Smith LL; Breci LA Mobile and Localized Protons: A Framework for Understanding Peptide Dissociation. J. Mass Spectrom 2000, 35, 1399–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Morrison LJ; Rosenberg JA; Singleton JP; Brodbelt JS Statistical Examination of the a and a + 1 Fragment Ions from 193 Nm Ultraviolet Photodissociation Reveals Local Hydrogen Bonding Interactions. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2016, 27, 1443–1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Morrison LJ; Chai W; Rosenberg JA; Henkelman G; Brodbelt JS Characterization of Hydrogen Bonding Motifs in Proteins: Hydrogen Elimination Monitoring by Ultraviolet Photodissociation Mass Spectrometry. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2017, 19, 20057–20074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Farsang E; Guillarme D; Veuthey J-L; Beck A; Lauber M; Schmudlach A; Fekete S Coupling Non-Denaturing Chromatography to Mass Spectrometry for the Characterization of Monoclonal Antibodies and Related Products. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal 2020, 185, 113207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).VanAernum ZL; Busch F; Jones BJ; Jia M; Chen Z; Boyken SE; Sahasrabuddhe A; Baker D; Wysocki VH Rapid Online Buffer Exchange for Screening of Proteins, Protein Complexes and Cell Lysates by Native Mass Spectrometry. Nat. Protoc 2020, 15, 1132–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Morrison LJ; Brodbelt JS Charge Site Assignment in Native Proteins by Ultraviolet Photodissociation (UVPD) Mass Spectrometry. Analyst 2016, 141, 166–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.