Keywords: auditory, reaching, sensorimotor adaptation, speech, vision

Abstract

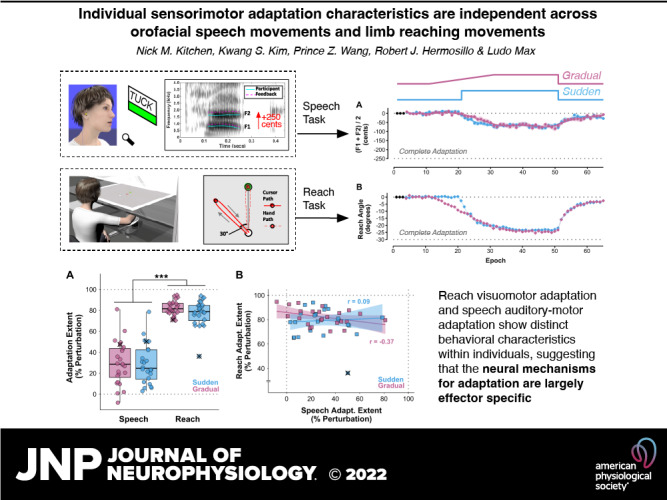

Sensorimotor adaptation is critical for human motor control but shows considerable interindividual variability. Efforts are underway to identify factors accounting for individual differences in specific adaptation tasks. However, a fundamental question has remained unaddressed: Is an individual’s capability for adaptation effector system specific or does it reflect a generalized adaptation ability? We therefore tested the same participants in analogous adaptation paradigms focusing on distinct sensorimotor systems: speaking with perturbed auditory feedback and reaching with perturbed visual feedback. Each task was completed once with the perturbation introduced gradually (ramped up over 60 trials) and, on a different day, once with the perturbation introduced suddenly. Consistent with studies of each system separately, visuomotor reach adaptation was more complete than auditory-motor speech adaptation (80% vs. 29% of the perturbation). Adaptation was not significantly correlated between the speech and reach tasks. Moreover, considered within tasks, 1) adaptation extent was correlated between the gradual and sudden conditions for reaching but not for speaking, 2) adaptation extent was correlated with additional measures of performance (e.g., trial duration, within-trial corrections) only for reaching and not for speaking, and 3) fitting individual participant adaptation profiles with exponential rather than linear functions offered a larger benefit [lower root mean square error (RMSE)] for the reach task than for the speech task. Combined, results suggest that the ability for sensorimotor adaptation relies on neural plasticity mechanisms that are effector system specific rather than generalized. This finding has important implications for ongoing efforts seeking to identify cognitive, behavioral, and neurochemical predictors of individual sensorimotor adaptation.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY This study provides the first detailed demonstration that individual sensorimotor adaptation characteristics are independent across articulatory speech movements and limb reaching movements. Thus, individual sensorimotor learning abilities are effector system specific rather than generalized. Findings regarding one effector system do not necessarily apply to other systems, different underlying mechanisms may be involved, and implications for clinical rehabilitation or performance training also cannot be generalized.

INTRODUCTION

Humans are capable of a wide range of complex and coordinated movements and flexibly adapt to changes in the environment. Sensory feedback regulates this process of adaptation by providing information regarding unpredicted consequences of the performed actions. Specifically, error signals generated by discrepancies between predicted and observed consequences update an internal model of the involved motor-to-sensory transformations to minimize error in future movements (see Ref. 1). Experimentally, sensorimotor adaptation is often quantified by measuring incremental changes in upper limb reach direction or motion path in the context of either a visual perturbation (e.g., a nonveridical cursor indicating hand position) or a proprioceptive perturbation (e.g., a dynamic load applied to the moving limb). The use of these paradigms has helped researchers to decompose some of the underlying learning and control processes (2–6), to identify involved brain regions (7–9), and to document associated perceptual changes (10–12).

Recently, there has been increasing interest in identifying interindividual differences that may explain the relatively high variability in sensorimotor adaptation that is observed even among neurotypical individuals (13, 14). Understanding this variability is critical not only for elucidating fundamental aspects of sensorimotor learning but also for translational work that seeks to optimize individualized training programs and clinical rehabilitation (13, 15). Relevant predictors of upper limb adaptation ability have already been shown to include individual characteristics in cognitive (16, 17), behavioral (18), and neurochemical (19) domains. It is remarkable, however, that it remains unknown whether individual sensorimotor adaptation ability actually correlates across different effector systems (i.e., reflecting an individualized but systems-wide learning ability) or whether the capacity for such learning is specific to each effector system such as the upper limbs, lower limbs, oculomotor system, and orofacial system. Although Lametti et al. (20) reported that reach visuomotor adaptation and speech auditory-motor adaptation are not correlated, their data had been obtained when subjects performed both tasks simultaneously (i.e., saying each word while performing a reach movement), and it is well documented that simultaneously performing manual and speech movements leads to bidirectional interference (see below for an overview). If it is confirmed that sensorimotor learning ability is indeed system specific rather than generalized, then any cognitive, behavioral, neurochemical, or other predictors of individual learning may be relevant only for the particular effector system for which such predictive value was directly demonstrated.

In fact, it is not clear to date whether common mechanisms underlie different forms of sensorimotor learning even within a given effector system. For example, for upper limb reaching movements, it has been argued that adaptation to kinematic errors (e.g., induced by a rotation of visual feedback) and adaptation to dynamic errors (e.g., induced by a viscous force field acting on the hand) are not correlated across subjects and that these distinct forms of adaptation depend on mostly segregated cerebellar areas (21–23). Nevertheless, sequential adaptation in tasks with kinematic versus dynamic errors can result in mutual interference effects, suggesting at least partial overlap of neural substrates or processing mechanisms in these different forms of adaptation (24, 25).

Thus, despite some prior interest in a possibly common set of principles underlying different forms of adaptation within a single effector system, no information is available regarding the question of whether a common learning ability underlies similar forms of adaptation (e.g., adaptation to only kinematic errors) in different effector systems such as the upper limb for reaching and the orofacial system for speech. Although it is very common for researchers to manipulate real-time visual feedback during reaching (thereby causing visual feedback to indicate hand position error), it is also possible to manipulate real-time auditory feedback during speaking (thereby causing auditory feedback to indicate error in positioning the lips, tongue, and/or jaw; for an extensive review of this literature on speech auditory-motor learning, see Ref. 26). Given that positioning of the speech articulators shapes the vocal tract to create vowel-specific formants (i.e., resonant frequencies), auditory manipulations that shift the formant frequencies in real time (as the signal is played back to the participant through earphones) do induce kinematic errors without mechanically perturbing the effectors, i.e., analogous to visuomotor manipulations during reach movements. In such speech auditory-motor adaptation studies, participants gradually adapt the planning of their articulatory movements to partially compensate for the perturbation (e.g., Refs. 27–30). Speech auditory-motor adaptation studies have also revealed limitations in individuals with speech disorders such as stuttering (31–33) and effects of the adaptation task on auditory perceptual judgments (34, 35). Of direct relevance for the present study, speech auditory-motor adaptation is associated with cerebellar activations similar to those seen for reach visuomotor adaptation [see, for example, meta-analyses by Johnson et al. (36)], and different domain-specific motor and sensory zones in the cerebellum do overlap (37). On the basis of these observations, one might predict that adapting to kinematic perturbations might depend on at least some shared cerebellar resources across speech and reach tasks.

Outside the context of sensorimotor learning, there is, in fact, intriguing evidence suggesting functional interactions between the neural systems controlling upper limb and speech movements. For example, excitability of the cortical hand motor area in the language-dominant hemisphere is increased while speaking (38, 39), and excitability of the cortical tongue motor area during speech is increased while observing power versus precision grasp movements (40). In addition, both observing and executing manual actions (e.g., grasping objects of different sizes, bringing objects toward the mouth) modulate acoustic and kinematic aspects of simultaneous or subsequent speech movements (40–44). Even for infants as young as 11–13 mo of age, manipulation of larger versus smaller objects has been reported to modulate the first formant frequency of accompanying vocalizations (45). Electromyographic recordings have also shown concurrent contraction of the orbicularis oris lip muscle during various manual actions (46). Conversely, producing vowels with more open versus more closed mouth positions leads to similar adjustments in finger aperture during simultaneous grasp movements (47). These previously demonstrated functional interactions between the sensorimotor control systems for the upper limb and the orofacial system for speech raise the interesting question of whether the two systems also rely on an overlapping or generalized sensorimotor learning ability.

Here, we start addressing this question by comparing, within the same set of participants, reach adaptation in the presence of a visuomotor perturbation and speech adaptation in the presence of an auditory-motor perturbation. We tested both reach adaptation when real-time visual feedback about hand position was rotated 30° counterclockwise (CCW) and speech adaptation when vowel formant frequencies in the real-time auditory feedback were shifted 250 cents upward (doubling the frequency of any signal equals 1,200 cents). In addition, both the reach adaptation task and the speech adaptation task were completed once with abrupt introduction of the perturbation and, on a separate day, once with ramped introduction of the perturbation, as these two conditions probe different aspects of sensorimotor adaptation (17, 48–50). For each condition, we quantified each participant’s extent of adaptation as well as potentially predictive performance measures such as trial duration, trial-to-trial variability during the baseline phase, and within-trial adjustments for both the baseline and perturbation phases.

METHODS

Participants

Twenty-six female participants between 18 and 32 yr of age (mean 23.2, SD 4.0) completed the experiment, but only 24 were included in the final analyses (mean 23.0, SD 4.1 yr). One excluded participant consistently made highly curved, rather than relatively straight, movements in the visuomotor reach task, and the other excluded participant’s behavior in the auditory-motor speech task followed, rather than opposed, the perturbation (see Speech data for details). All participants self-reported to be native speakers of American English and to be right hand dominant, and all were screened to have monaural hearing thresholds ≤ 20 dB HL for the octave frequencies 250–4,000 Hz in both ears. All participants had also been screened to ensure a self-reported negative history of psychological, neurological, or communication disorders. Before the experiment, participants provided written informed consent in accordance with procedures approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board. After completion of the experiment, they received financial compensation for their time. None of the participants had previously enrolled in any of our speech or reach adaptation studies.

Apparatus

Auditory-motor speech task.

Speech auditory-motor adaptation tasks were completed inside a large sound booth (Industrial Acoustics Company, North Aurora, IL). Each participant’s acoustic speech output was recorded with a boom-mounted microphone (SM58; Shure, Niles, IL) placed 15 cm from the mouth. The microphone signal was amplified (DI/O Preamp System II; Applied Research and Technology, Niagara Falls, NY) and then recorded by the data acquisition computer (44.1 kHz sampling rate) for offline acoustic analyses. The amplified microphone signal was also fed through a digital voice processor (VoiceOne; TC Helicon, Victoria, BC, Canada) with capability to shift all formant frequencies in the vowel segments of the participant’s speech during the perturbation phase (see Procedure). This signal was then routed through a headphone amplifier (S-Phone; Samson Technologies, Hicksville, NY), and presented to the participant by means of audiometric ER-3A insert earphones (Etymotic Research, Elk Grove Village, IL). The total feedback loop latency for this system is 10 ms (51). In addition to being recorded on the data acquisition computer, a back-up copy of the participants’ speech output was also digitized (44.1 kHz) by a CD recorder (XL-R5000BK; JVC, Yokohama, Japan).

Immediately before each individual recording session, the auditory feedback system was calibrated such that speech with an intensity of 75 dB SPL at a location 15 cm in front of the mouth (i.e., at the microphone) resulted in auditory feedback with an intensity of 73 dB SPL in the earphones. Earphone intensity was measured in a 2-cc coupler (type 4946; Brüel & Kjӕr, Nӕrum, Denmark) connected to a sound level meter (type 2250 A Hand Held Analyzer with type 4947 ½-in. Pressure Field Microphone; Brüel & Kjӕr). This input-output ratio closely matches the results from simultaneous recordings of a speech signal at a microphone in front of the speaker and at the level of the speaker’s ear (52).

Visuomotor reach task.

Reach visuomotor adaptation tasks were completed with participants seated at a custom-built virtual display system with a horizontal glass work surface (on which the reaching movements were made) located below a horizontal first surface mirror (on which the visual images of reach targets and hand position cursor feedback were projected). To the participant, all displayed images appeared to be in the same horizontal plane as the glass work surface.

Participants performed the reaching movements with their right forearm secured to a lightweight (330 g) air-sled for near-frictionless movement over the glass work surface. Movements were tracked with an electromagnetic system (Liberty; Polhemus) with a sensor attached to the extended right index finger. Custom MATLAB software (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) processed the sensor data to provide visual feedback of hand/finger position, with nonveridical feedback presented during the perturbation phase (see Procedure). The total feedback loop latency in the virtual display system is ∼32 ms. The position data were recorded at 240 samples per second by the data acquisition computer for offline kinematic analyses.

Procedure

General features of the adaptation tasks.

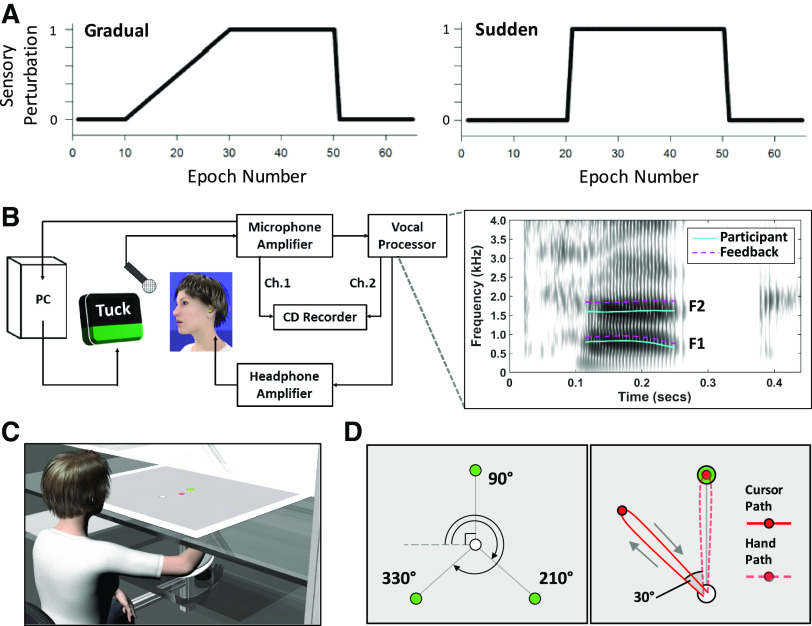

In all conditions, participants were first given a brief block of six trials (2 trials for each of the 3 different reach targets or words) without sensory perturbation for instruction and familiarization purposes (data not analyzed). For both the speaking and reaching adaptation tasks, there were two separate conditions with the sensory perturbation introduced either gradually or suddenly (Fig. 1A). For the Gradual condition, after a baseline phase consisting of 10 epochs of three trials (an epoch includes 1 trial for each of the 3 reach targets or words), the perturbation was ramped up in equal increments across 20 epochs of three trials. For the Sudden condition, after a baseline phase with 20 epochs of three trials, the full perturbation was introduced all at once between two successive trials. In both conditions, the perturbation was suddenly removed after a total of 50 epochs had been completed, and the perturbation then remained off for a washout phase with the final 15 epochs. Thus, in total there were 195 trials (65 per reach target or word) per condition.

Figure 1.

A: perturbation schedule for the gradual and sudden conditions, with the y-axis indicating the normalized extent of the perturbation and the x-axis indicating epochs of 3 trials (1 per reach target or word). B: equipment configuration for the speech auditory-motor adaptation task. Right: spectrogram for 1 trial of the word “tuck,” with solid turquoise tracking of the participant’s formants and the dashed purple tracks indicating the 250 cents upshift auditory feedback perturbation. C: experimental setup for the reach adaptation task. D, left: location of the 3 targets and central start position for the reach adaptation task. Right: unseen actual hand path (dashed red line) and projected visual feedback path (solid red line) for an early, full 30° counterclockwise perturbation trial.

Trial duration was matched between tasks such that the onset-to-onset intertrial interval was always ∼4 s. Thus, the rate of presentation was ∼15 trials per minute, and the total task duration was always ∼13 min. Participants completed the four experimental conditions (i.e., gradual/sudden perturbation schedule for speech/reach adaptation tasks) in a counterbalanced order across two separate visits to the laboratory. Each visit included one speech task and one reach task, with one of these tasks assigned the gradual perturbation schedule and the other task the sudden perturbation schedule. Across participants, the two visits were separated by a minimum of 5 days and a maximum of 11 days.

Auditory-motor speech task.

Participants were seated in front of a computer monitor and produced the consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) words “talk,” “tuck,” and “tech” that were presented individually on the screen (Fig. 1B). Presentation order of the words was randomized within each epoch of three trials. After each production, color-coded visual feedback was provided in the bottom portion of the screen to help the participant maintain a relatively constant speech output intensity (between 72 and 78 dB SPL measured 15 cm from the mouth). During different phases of the task, participants heard auditory feedback of their speech either unaltered or with the frequency of all formants of the vowel portion (but not any other acoustic features) shifted upward. In the Gradual condition, the shift ramped up from 0 to 250 cents (2.5 semitones). In the Sudden condition, the shift was always 250 cents. The acoustic speech output was recorded and stored for offline analysis.

Note that this specific global formant perturbation (i.e., all formants shifted proportionally the same amount and in the same direction) does not change the phonemic identity of the produced vowel (i.e., the feedback signal does not sound like another vowel that exists in the language). This perturbation was preferred for the present study because of 1) the ability to directly verify the speech results against those from several of our prior publications (31, 33, 53–56) and 2) our position that a global formant perturbation has greater validity, as opposed to a phonemic formant perturbation, for comparison with the visuomotor rotation task. Specifically, in a visuomotor rotation task as implemented in the present study (details below), the perturbation causes the cursor to land between targets in the absence of any correction or adaptation; no feedback is presented that would signal to the subject that a target selection error had occurred. In speech, a phonemic formant perturbation would result in the subject hearing back a whole different target (e.g., hearing “bad” when producing “bed”), whereas a global formant shift in the upward direction results in the subject hearing back the correct word but with spectral characteristics generally resembling those of a shorter vocal tract.

Visuomotor reach task.

For the reaching task, participants sat in front of the virtual display system with their right hand secured onto the air-sled (Fig. 1C). Participants saw a white central start position (1-cm radius), a red finger position cursor (0.75-cm radius), and one of three green targets (0.75-cm radius) located 10 cm from the start position [at 90°, 210°, and 330° from the horizontal axis of the 2-dimensional (2-D) workspace; Fig. 1D, left). Their arm and hand remained hidden from view at all times.

Once seated, each participant’s arm was positioned with the elbow at ∼90° and the tip of the right index finger aligned along the midsagittal plane. This finger position (∼30 cm from participant’s chest) was used to define the central start position for the task so that all targets would be located within a comfortable range of motion. When a new target appeared, this served as the “go” cue for the participant to make an out-and-back reaching movement to hit the target and return to the start position as quickly and as accurately as possible. The participant then held their finger at the start position until a new target appeared and the next trial began. Visual feedback of finger position was provided in real time by the red cursor. During perturbation trials, the displayed cursor position was rotated counterclockwise (CCW) around the start position up to 30° relative to the real finger position (Fig. 1D, right). The perturbation reached 30° all at once in the Sudden condition but was ramped up from 0° to 30° in the Gradual condition.

For consistency with the speech data, we consider the sign of the CCW perturbation to be positive, such that a behavioral adjustment with negative sign [in the clockwise (CW) direction] was necessary to compensate for the perturbation. All finger position data tracked by the electromagnetic motion sensor were recorded and stored offline for future analysis.

Data Extraction

Speech data.

To assess speech adaptation, a combination of custom routines in Praat (57) and MATLAB were used to automatically select vowel segments (i.e., from the onset to offset of vocal fold vibration) and to track the first and second formant frequencies (F1, F2) throughout the selected vowel. The automated routine presented the tracked formants overlaid on the spectrogram for trial-by-trial visual inspection and manual correction if necessary. F1 and F2 frequencies were then extracted as the average values across a time window 5–25% into the vowel. This early window was selected to minimize any potential influence of feedback-driven online corrections on the formant measures (e.g., Ref. 58). For rejected trials (e.g., when the participant yawned or coughed while speaking), a replacement data point was calculated by interpolating the four nearest neighboring trials, but this was necessary for <1% of all trials.

To normalize adaptive changes in these formant frequencies relative to baseline, and to simultaneously convert from hertz units to the same cents scale used by the vocal processor to implement the perturbation, all final formant values were calculated as shown in Eq. 1 (31).

| (1) |

In this equation, FHz refers to any trial’s F1 or F2 in hertz and BHz refers to the median baseline value of F1 and F2 in hertz for the same vowel. For baseline calculation, the first three trials of each target word were excluded, as these trials often show greater variability. Thus, for each participant, the median F1 and F2 values for trials 4–10 of each target vowel served as the baseline values.

For the present study, we excluded participants whose changes in speech output followed rather than opposed the perturbation (an individual participant phenomenon reported in many studies of speech auditory-motor adaptation). Following behavior was defined as cases where the mean formant values across the final five trials of the perturbation phase exceeded +25 cents (i.e., a change in the same direction as the feedback shift). Only one participant was excluded on this basis.

Reach data.

Reaching movements were analyzed with a custom routine in MATLAB that selected the onset and offset of the outward movement as the points where the tangential velocity first exceeded and then fell below 5 cm/s, respectively. In cases where these criteria failed to detect movement onset or offset, local minima preceding or following the outward movement velocity peak were selected. Reach direction was then quantified as the outward movement’s angular deviation from the linear start-to-target vector at the time of peak tangential velocity (Refs. 33, 59; note that in all trials the time of peak tangential velocity occurred <150 ms after movement onset). The custom software allowed visual inspection, and, if necessary, manual correction, by presenting each movement trajectory and corresponding velocity profile together with markers for the identified movement onset, offset, and peak velocity. Similar to the speech data, rejected trials (e.g., reaching for the wrong target) were replaced by interpolating values from the four nearest neighboring trials, but again this was necessary for <1% of the collected data. Also consistent with the speech analyses, reach directions were expressed (in degrees) relative to the median direction across baseline trials 4–10 for the same target, with the first three trials per target being discarded to avoid any influence of initial familiarization.

Dependent Variables

Adaptation extent.

To allow comparisons between the speaking and reaching tasks, the baseline-normalized vowel formant data and the reach direction data were both transformed into values expressing a percentage of the imposed feedback perturbation (e.g., a downward formant adjustment of 125 cents or a clockwise reach direction adjustment of 15° both would be transformed to 50%). These data were then averaged per epoch of three targets for the reaching task and epochs of three words (including averaging across F1 and F2 values) for the speech task. The mean of the final five epochs of the perturbation phase was used as an index of adaptation extent.

Trial duration.

For the reach adaptation task, trial duration was defined as the time between the above-defined onset and offset points of the outward movement. For the speech task, trial duration was defined as the duration of the selected vowel. Trial duration was averaged separately for the baseline phase (trials 4–10 for each word/target) and the adaptation phase (trials 21–50 of each word/target). The latter corresponds to the entire perturbation phase in the sudden condition and from midway through the ramp to the end of the perturbation phase for gradual condition (Fig. 1A). This procedure allowed for separate indexes of trial duration under unaltered and perturbed sensory feedback conditions, to examine potential correlations with adaptation extent.

Baseline intertrial variability.

Using the formant frequency and reach direction data that had been normalized and expressed as a percentage of the perturbation, we calculated the standard deviation of these values across the baseline trials as an index of performance variability. We examined the potential correlation of this intertrial variability index with adaptation extent based on previous reports suggesting an association between motor variability and motor learning (18, 60).

Within-trial adjustments in the baseline phase.

To quantify within-trial adjustments during the unperturbed baseline trials, we used the centering measure introduced for speech by Niziolek et al. (58). Centering is a process whereby a participant’s formant frequency adjustments from vowel onset to vowel midpoint are greater for vowels that start with their formants further away from the participant’s median production for that same word (i.e., “peripheral” vowels get adjusted more). Following Niziolek et al. (58), we first calculated the Euclidean distance in F1 and F2 space (in cents) between the initial portion of each trial’s vowel (measured in the window 5–25% into the vowel) and the same initial portion of the participant’s median baseline production of the same vowel. This initial distance (DInit) from the median was determined as . We then calculated the same distance for the middle portion of the vowel (measured in the window 40–60% into the vowel). This mid-vowel distance (DMid) was determined as . The centering value for each trial was then defined as C = DInit − DMid, where a more positive value indicates that the formants showed a greater adjustment toward the median production from the initial to the middle window for the vowel. We then used the participants’ average centering values as an index of within-trial correction in the baseline productions.

Although DInit and DMid are defined based on acoustic aspects of the vowel segment, from an articulatory perspective it is important to point out that Niziolek et al. (58) previously applied the centering measure to productions of VC words whereas participants in the present study produced CVC words. The produced CVC words involved an articulatory opening gesture from the initial voiceless consonant /t/ to one of the three target vowels (i.e., the tongue and jaw are lowered) followed by an articulatory closing gesture from the vowel to the final voiceless consonant /k/ (i.e., the tongue and jaw are raised). Two important consequences of using this particular phonetic sequence are that 1) our DInit data were extracted when phonation for the vowel started some time after onset of the articulatory opening gesture (in the example spectrogram in Fig. 1B, phonation starts ∼80 ms after the initial acoustic burst that signals release of the articulatory obstruction for the consonant) and 2) our DMid data were extracted approximately at the time of movement direction reversal at the end of the opening gesture and beginning of the closing gesture. For these specific reasons, we defined an analogous centering measure for the outward component of the reach movements by extracting reach angle, θ, at the time of peak velocity (PV) and movement end point (EP; i.e., direction reversal) to calculate DInit and DMid, respectively: and . Here, a positive centering value indicates a tendency for the outward reach movements to converge toward the median baseline reach angle from the time of peak velocity to the end of the movement. For consistency with the acoustics-based terminology used in prior speech work (58), we use the “init” and “mid” labels for these two data extraction time points in both our speech and reach centering measures, even though the above operational definitions make it clear that, from a kinematic perspective, our measures focus on within-trial corrections in the second half of the movement.

Within-trial adjustments in the perturbation phase.

For trials in the adaptation phase, we aimed to assess possible online corrections opposing the perturbation. We therefore quantified within-trial adjustments as the signed change from early in the trial (i.e., initial vowel window for the speech task, time of peak velocity for the reach task) to late in the trial (i.e., midvowel window for the speech task, movement end point for the reach task). For the speech task, the within-vowel change was calculated in cents separately for F1 and F2 and then averaged. For the reach task, the change was calculated in degrees. To remove the influence of any systematic but not perturbation-related adjustments, we subtracted the mean within-trial change in the baseline trials from that observed in each perturbation trial. Negative values indicate within-trial changes in the direction opposite to the perturbation (i.e., true corrections); positive values indicate within-trial changes in the same direction as the perturbation.

Learning curve fit.

We examined whether individual participant learning curves for speech auditory-motor adaptation and reach visuomotor adaptation are generally similar or different. Specifically, we performed a basic goodness-of-fit comparison between a linear regression and an exponential decay function with data from the speech and reach sudden conditions (given that the ramped implementation of the perturbation in the gradual condition constrains the rate of adaptation). For this analysis, all data were again expressed as a percentage of the perturbation, but such that perfect adaptation would correspond to −100%. This approach preserved the decaying nature of the adaptation data over time.

To fit the data from the perturbation phase, first an initial data point y = 0 was added to represent the median of the normalized baseline trials (recall that our data represent participant behavior rather than characteristics of the feedback signal; thus, adaptation consists of values gradually moving away from baseline rather than gradually approaching baseline again). For both tasks, the perturbation trials were fitted with both a linear regression function y = Bx + C and an exponential function y = Beλ + C. In MATLAB, the regress function was used for linear regression and fmincon was used to fit the exponential function. The latter function acted to minimize the root mean square error (RMSE) of the fit under upper- and lower-bound parameter constraints that permitted both positive and negative adaptation rates (represented by λ). We defined , where nObs is the number of residual data points from the fitted function and nTerms is the number of terms or parameters in the function itself. This method penalizes for the number of terms in the model to control for potential overfitting with the more complex exponential function. The RMSE values were then used to compare speech and reach adaptation in terms of how well individual participant adaptation profiles were fit by the linear versus exponential function.

Statistical Analysis

Adaptation extent was analyzed with 2 × 2 repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the factors task (speech or reach) and perturbation schedule (sudden or gradual). Pearson correlation coefficients were used to examine whether adaptation extent was correlated between the speech and reach tasks for a given perturbation schedule (i.e., separate correlation analyses for the sudden and gradual perturbations) and between conditions with suddenly or gradually introduced perturbations within each task (i.e., separate correlation analyses for the speech and reach tasks).

To understand which aspects of motor behavior might be associated with adaptive learning in speaking, reaching, or both, we examined the correlations between adaptation extent and the additional measures of trial duration, baseline performance variability, within-trial adjustments in the baseline phase, and within-trial adjustments in the perturbation phase.

Finally, to examine which model best fitted the sudden condition adaptation data, we analyzed the RMSE of the linear and exponential functions with a 2 × 2 repeated-measures ANOVA using the factors task (speech or reach) and model (linear or exponential).

For all analyses, we visually identified outlier data points that might impact parametric statistical tests. After we confirmed that these outliers were not due to measurement error, they were classified numerically with the mean absolute deviation (MAD), a method of outlier detection that is relatively unaffected by both the distribution of the raw data (outliers included) and the sample size (61, 62). Specifically, outliers were identified according to a threshold of 3 times the MAD around the group median of each condition (an exclusion criterion that is generally considered conservative; Ref. 61). For adaptation extent, we identified one outlier value in the sudden condition of the reach task (as highlighted in Fig. 3, A and B). For the correlation analyses, we identified 15 outlier data points across all dependent variables and all conditions (3% of the data), and these data points are identified as appropriate in the figures in results. For the RMSE data, we identified outlying data from one participant in each task (as highlighted in Fig. 5, B and D).

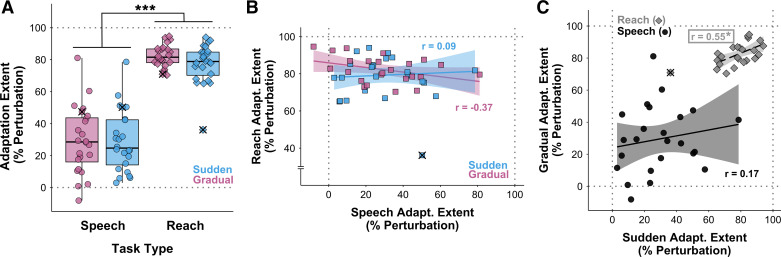

Figure 3.

A: boxplots of adaptation extent (as % of perturbation size) for the speech and reach tasks with sudden and gradual perturbation schedules. Adaptation was much more complete for reaching than for speaking (***P < 0.001). One outlier participant was identified in the sudden condition reach task. This individual’s data are marked with × in all conditions and were not included in the ANOVA. B: correlations between adaptation extent in the reach and speech tasks were not statistically significant for either the sudden (blue) or gradual (pink) condition. C: the correlation between adaptation extent in the gradual and sudden conditions was statistically significant for the reach task (gray diamonds) but not for the speech task (black circles). For B and C, lines and shaded regions represent linear regression fits with 95% confidence intervals; the asterisk indicates Padj < 0.05; data points marked with × represent the participant with outlier data in the reach-sudden condition and were not included in the correlation analyses.

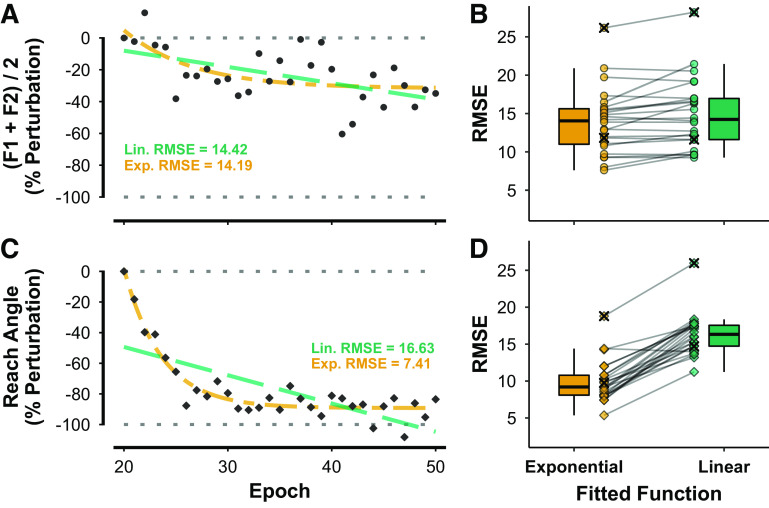

Figure 5.

Linear (Lin; green) and exponential (Exp; orange) model fitting for individual participant adaptation profiles in the sudden condition of the speech and reach tasks. Illustrations for a representative participant (A for speaking, C for reaching) show raw data and fitted functions together with root mean square error (RMSE) values for each fit (F1, F2: 1st and 2nd formant frequencies). Boxplots (B for speaking, D for reaching) show the RMSE values for exponential and linear fits for all participants. Two participants (1 in each task, both fitted functions) were found to have outlying data. These participants were not included in the final ANOVA and are marked with ×.

Below, all descriptive results are presented as raw means ± 1 standard deviation (i.e., with detected outliers included) unless otherwise stated. Statistical significance was assessed with a threshold of α = 0.05, and partial omega squared () was used to estimate effect sizes. A false discovery rate analysis was used to adjust P values (denoted as Padj; Refs. 63, 64) for the multiple correlation analyses. All statistics were performed in R Studio (65, 66), with ANOVAs and effect sizes calculated with the ezANOVA (67) and MOTE (68) packages.

RESULTS

Adaptation Extent

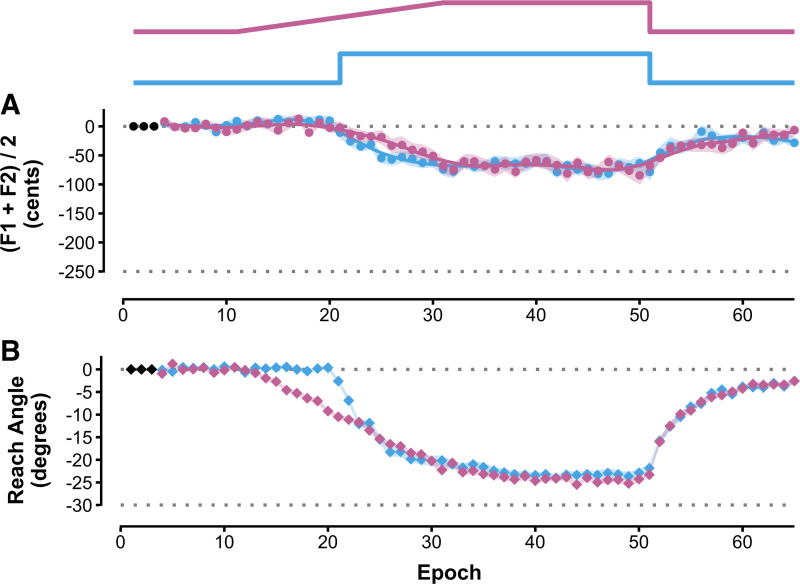

Figure 2, A and B, show group average time series data for adaptation extent across all trial epochs in the speech and reach tasks, respectively. Boxplots of adaptation extent as a percentage of perturbation size are shown in Fig. 3A, separately for the two tasks and two perturbation schedules. One outlier participant was identified in the sudden condition of the reach task, and their data were not included in the final ANOVA (but exclusion of these data did not change the outcome of statistical significance testing with ANOVA). The measure of relative adaptation was much more complete for the reach task (79.8 ± 10.3%) than for the speech task (29.2 ± 19.8%), as confirmed by a statistically significant task main effect with large effect size [F(1,22) = 230.41, P < 0.001, = 0.83]. There was no significant main effect for perturbation schedule [F(1,22) = 0.62, P = 0.439] and no significant task × perturbation schedule interaction [F(1,22) = 0.23, P = 0.636].

Figure 2.

Group mean adaptation data (with shaded areas indicating ±1 SE) for gradual (pink) and sudden (blue) perturbation schedules (illustrated at top). Each participant’s data were first normalized to the median value of baseline trials 4–10. A: speech auditory-motor adaptation to a +250 cents shift of the vowel formant frequencies during monosyllabic word production (F1, F2: 1st and 2nd formant frequencies). B: reach visuomotor adaptation to a 30° counterclockwise rotation of fingertip cursor location during out-and-back movements. Data points correspond to epochs of 3 trials (cycles including 1 trial for each of 3 different target words or reach directions). The first 3 epochs of each condition (black symbols) were discarded to avoid initial familiarization effects on baseline normalization.

As illustrated in Fig. 3B, adaptation extent was not statistically significantly correlated between the speech task and the reach task for either the gradual (r = −0.37, P = 0.076, Padj = 0.153) or the sudden (r = 0.088, P = 0.688, Padj = 0.688) perturbation schedule. Moreover, as illustrated in Fig. 3C, whereas the reach task showed a statistically significant positive correlation for adaptation extent in the sudden versus gradual perturbation conditions (r = 0.55, P = 0.006, Padj = 0.013), this was not the case for the speech task (r = 0.17, P = 0.422, Padj = 0.422).

Correlations between Adaptation Extent and Other Performance Measures

Measures obtained during the baseline phase.

The correlations between adaptation extent and baseline trial duration, intertrial variability, and within-trial centering are listed in Table 1. It is worth noting that a majority of the participants did demonstrate centering behavior in both the reach task (gradual = 0.85 ± 0.62°; sudden = 0.89 ± 0.65°) and the speech task (gradual = 15.7 ± 1.1 cents; sudden = 16.2 ± 21.9 cents). However, none of the correlation coefficients in Table 1 was statistically significant. Thus, across participants, adaptation extent did not vary with any of the three baseline performance measures for either reach adaptation or speech adaptation.

Table 1.

Correlations between adaptation extent and baseline phase measures of trial duration, intertrial variability, and within-trial centering, separately for task conditions with gradual and sudden perturbation schedules

| Gradual Condition |

Sudden Condition |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P | P adj | r | P | P adj | |

| Speech task | ||||||

| Duration | −0.064 | 0.778 | 0.916 | 0.167 | 0.446 | 0.638 |

| Variability | 0.023 | 0.916 | 0.916 | −0.124 | 0.564 | 0.638 |

| Centering | 0.286 | 0.175 | 0.526 | −0.106 | 0.638 | 0.638 |

| Reach task | ||||||

| Duration | 0.254 | 0.242 | 0.242 | 0.226 | 0.313 | 0.355 |

| Variability | 0.333 | 0.121 | 0.181 | −0.202 | 0.355 | 0.355 |

| Centering | 0.405 | 0.055 | 0.165 | 0.217 | 0.320 | 0.355 |

Measures obtained during the perturbation phase.

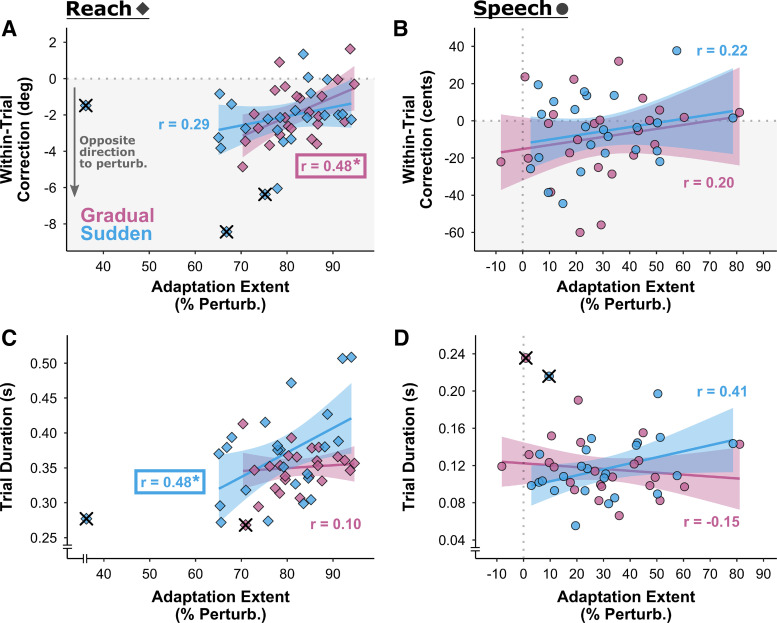

The correlations between adaptation extent and perturbation phase trial duration and within-trial corrections are listed in Table 2. For the speech task, none of the correlation coefficients were statistically significant. For the reach task, there was a statistically significant correlation between the extent of adaptation and the extent of within-trial corrections, albeit only for the gradual condition: participants who showed more adaptation in this gradual condition tended to make smaller within-trial corrections in the opposite direction to the perturbation (see Fig. 4A, with the corresponding plot for the speech task in Fig. 4B). For the reach task, there was also a statistically significant correlation between the extent of adaptation and trial duration, but this time only for the sudden condition: participants who showed more adaptation in the sudden condition tended to make reach movements with longer duration (see Fig. 4C, with the corresponding speech data shown in Fig. 4D).

Table 2.

Correlations between adaptation extent and perturbation phase measures of trial duration and within-trial corrections, separately for task conditions with gradual and sudden perturbation schedules

| Gradual Condition |

Sudden Condition |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P | P adj | r | P | P adj | |

| Speech task | ||||||

| Duration | −0.149 | 0.504 | 0.504 | 0.405 | 0.055 | 0.110 |

| Correction | 0.197 | 0.357 | 0.504 | 0.221 | 0.300 | 0.300 |

| Reach task | ||||||

| Duration | 0.100 | 0.649 | 0.649 | 0.477 | 0.021 | 0.043* |

| Correction | 0.482 | 0.017 | 0.034* | 0.286 | 0.209 | 0.209 |

*Padj < 0.05.

Figure 4.

Correlations between adaptation extent and perturbation phase measurements of within-trial corrections [reaching (A), speaking (B)] and trial duration [reaching (C), speaking (D)]. Gradual condition in pink; sudden condition in blue. In A and B, negative within-trial corrections indicate adjustments made in the opposite direction to the perturbation (gray shaded region). Outlier data points not included in the analyses are shown with × superimposed. Statistically significant correlations with adaptation extent occurred only for the reach task: for within-trial corrections in the gradual condition (A) and for trial duration in the sudden condition (C) (*Padj < 0.05).

Individual Participant Adaptation Profiles

For the speech task, linear and exponential fits performed equally well in representing individual participant adaptation data (exponential RMSE = 13.97 ± 4.30; linear RMSE = 14.93 ± 4.60). Raw speech adaptation data and fitted functions for one representative participant are shown in Fig. 5A, and boxplots for the corresponding group-level data are shown in Fig. 5B. For the reach task, on the other hand, there was a clear advantage for the exponential fit (RMSE = 9.93 ± 2.83) over the linear fit (RMSE = 16.31 ± 2.78). For this task, raw and fitted data for the same participant are shown in Fig. 5C and the group-level boxplots are shown in Fig. 5D. One participant in each task was found to have outlying data (see Fig. 5, B and D); thus their data was not included in the final ANOVA (although the exclusion of this participant was verified to not change the statistical significance of the ANOVA effects). The ANOVA revealed a statistically significant main effect of model [F(1,21) = 150.36, P < 0.001, = 0.45], with the exponential model generally yielding lower RMSE values than the linear model. There was no effect of task [F(1,21) = 2.04, P = 0.168], but there was a statistically significant task × model interaction [F(1,21) = 82.51, P < 0.001, = 0.31], which indicated a greater advantage of exponential over linear models for the reach task than for the speech task. Importantly, this interaction is also observed when conducting the same analysis with data normalized relative to adaptation extent, confirming that the fit difference between speaking and reaching is not merely a result of differences in magnitude of adaptation extent.

DISCUSSION

Identifying the factors that determine interindividual differences in sensorimotor adaptation holds great potential for revealing fundamental aspects of sensorimotor learning abilities and for informing translational work seeking to optimize individualized training programs and clinical rehabilitation (13, 15). Although several predictors of upper limb adaptation have been identified (16–19), it has remained unknown whether individual sensorimotor adaptation ability is generalized across different effector systems (and thus correlates across systems) or specific to each effector system (i.e., does not correlate across systems). Here, we asked the same participants to perform analogous adaptation paradigms that relied on distinct motor and sensory systems: visuomotor reach adaptation and auditory-motor speech adaptation. Participants completed each task once with the perturbation introduced gradually (ramped up over 60 trials) and, on a different day, once with the perturbation introduced suddenly (all at once) between two successive trials. First, consistent with previous studies of each system separately, visuomotor reach adaptation was considerably more complete than auditory-motor speech adaptation (80% vs. 29% of the perturbation, respectively). Second, adaptation extent was not significantly correlated between the speech and reach tasks. Third, within-system correlation analyses revealed that 1) adaptation extent was correlated between the gradual and sudden conditions of the reaching task but not between the gradual and sudden conditions of the speaking task and 2) adaptation extent was also correlated with additional measures of performance (e.g., trial duration, within-trial corrections) only for the reaching task and not for the speaking task. Fourth, fitting individual participant adaptation profiles with exponential rather than linear functions offered a larger benefit (i.e., improvement in goodness of fit) for the reach task than for the speech task. Taken together, these findings suggest that an individual’s capability for sensorimotor adaptation relies on mechanisms that are largely effector system specific rather than generalized.

Visuomotor Reach Adaptation Was More Complete than Auditory-Motor Speech Adaptation

Extent of adaptation, expressed as a percentage of the perturbation, was much greater in the visuomotor reach task (80%) than in the auditory-motor speech task (29%), a result highly consistent with previous studies of each system separately. For example, visuomotor reach adaptation in the range ∼70–90% of the perturbation is well documented for paradigms with sudden or gradual 30° rotations (e.g., Refs. 33, 49, 59, 69, 70). Although there has been more variation in methodological details across auditory-motor speech adaptation paradigms, the adaptation extent observed here for the speech task is also consistent with the range ∼20–40% of the perturbation typically reported for this line of work (e.g., Refs. 30, 31, 33, 34, 53, 54, 71–75).

Of course, it is not known whether the extent of our auditory and visual perturbations, in terms of their own domain-specific physical and perceptual units, is “comparable” between the speech and reach paradigms. It is important to note, however, that the considerably smaller extent of adaptation for speech cannot be attributed to the auditory perturbation being of insufficient magnitude, as it has been demonstrated that speech adaptation remains limited regardless of perturbation size (74). In fact, auditory perturbations larger than those implemented here tend to further reduce, rather than increase, speech adaptation (54, 76). In addition, the smaller adaptation extent for our speech task also cannot be attributed to the implementation of an auditory perturbation that did not alter the phonemic category of the produced vowels: the typical range of 20–40% adaptation in prior speech studies (see above) is seen across both phonemic and nonphonemic perturbations. Speech studies do occasionally yield a greater extent of adaptation, up to ∼50% of the perturbation magnitude, but such exceptions have occurred for both phonemic and nonphonemic formant perturbations (e.g., phonemic in Ref. 77, nonphonemic in Ref. 56). Thus, the combined evidence provided by our new results and the above prior observations strongly supports the conclusion that speech auditory-motor adaptation is indeed more limited than reach visuomotor adaptation.

A number of explanations have been previously suggested to account for limitations in speech auditory-motor adaptation, including the possibility of perceptual recalibration (78) and conflict between the unperturbed somatosensory feedback and perturbed auditory feedback (30, 74, 79, 80). Subtle shifts of the categorical perceptual boundaries between speech sounds have indeed been demonstrated (34, 35), but these shifts are much too small to explain the large amount of the perturbation that is left uncompensated. It remains to be determined whether or not conflict between somatosensory feedback and auditory feedback affects speech auditory-motor adaptation in a manner that does not apply to the similar conflict between somatosensory and visual feedback in visuomotor adaptation. Also deserving of further investigation is the hypothesis that physical constraints related to the involved effectors and vocal tract geometry make more complete adaptation impossible for certain phonemic and nonphonemic perturbations.

An interesting additional potential explanation for the discrepancy in adaptation completeness between reach visuomotor adaptation and speech auditory-motor adaptation follows from the relative contribution of two key components of sensorimotor learning: explicit strategy use and implicit learning. The explicit component of adaptation involves the use of an intentional strategy to correct for prior error. This process is rapid, highly flexible (i.e., can be selectively expressed or suppressed; Ref. 81), and largely driven by target errors, which provide salient feedback about whether an action was successful in achieving the task goal (3, 82, 83). The implicit component, on the other hand, involves an involuntary change in motor output in response to sensory prediction error (i.e., a mismatch between observed and predicted sensory feedback; Refs. 3, 5, 84). Whereas upper limb visuomotor adaptation involves both explicit and implicit components (85, 86), consensus has emerged that speech auditory-motor adaptation to formant perturbations is an entirely implicit process (20, 77, 87). Given that several studies have reported that the explicit component in upper limb adaptation studies may account for 50% or more of the total adaptation extent (5, 88–90), one might speculate that limited adaptation in the speech task can be explained by the lack of such explicit strategy use. The problem with this hypothesis, however, is that it is difficult to reconcile with the available evidence regarding adaptation to gradually introduced perturbations: even for reach visuomotor adaptation, learning with a gradual perturbation is implicit for many, if not most, subjects (17, 91–94). Yet both our own data from the present study (see Fig. 3A) and the combined data from several previously published studies (e.g., Refs. 50, 93, 95) indicate that total adaptation extent is not significantly reduced if total exposure is appropriately controlled (in our own paradigm, total exposure for the sudden and gradual perturbations was equalized in terms of “area under the perturbation curve”). In the present study, neither reach nor speech adaptation extent differed between the gradual and sudden conditions, and thus the adaptation completeness difference between the reach task and the speech task was present in both the gradual and sudden conditions. In other words, this between-task difference was independent of whether reach adaptation involved both explicit and implicit components or was mostly restricted to the implicit component.

Finally, an alternative explanation for the discrepancy in adaptation completeness may be found in major differences between the reaching and speaking systems in error sensitivity. In state space models of sensorimotor learning, error sensitivity is a parameter reflecting the proportion of error experienced on a given trial that is corrected for on the next trial. For upper limb visuomotor learning, error sensitivity has been estimated to be in the range 20–50% (96–98). For speech auditory-motor adaptation, on the other hand, it has been reported to be only ∼5% based on a single-rate model (99). Here, we did not aim to identify a particular state space model that could be fitted equally well to the reaching and speaking data in order to make a direct comparison of error sensitivity estimates given that such a finer-grade investigation of involved subprocesses (e.g., forgetting vs. learning rates in fast and slow components) would be beyond the scope of the present investigation. It is clear, however, that further studies of across-system differences in error sensitivity are needed, including analyses of the relationship between error sensitivity in learning tasks and each system’s trial-to-trial variability for natural unperturbed movements (55, 97).

Adaptation Extent Was Not Significantly Correlated between the Reach and Speech Tasks

Despite ample evidence for functional overlap in the neural representations of orofacial speech and upper limb systems (38–47), we found no significant correlations between speech adaptation and reach adaptation in either the sudden or the gradual perturbation condition. The absence of a correlation for the condition with gradual introduction of the perturbations is perhaps most of interest given that, under these circumstances, even visuomotor adaptation is thought to depend largely on implicit rather than explicit processes (17, 91–94). Thus, even in the condition where both reach adaptation and speech adaptation are presumed to be driven only by implicit learning processes, individual adaptation performance across the two tasks was not correlated. It was already known, however, that even within the upper limb system the mere implicit nature of two otherwise distinct learning tasks does not result in correlated learning performance (60). Combined with the fact that we found individual speech and reach adaptation to be independent for both the sudden and gradual perturbation schedule, it is unlikely that the difference in relative contributions from explicit versus implicit processes can explain the lack of correlation between the two tasks. Instead, our findings provide evidence that sensorimotor adaptation involves distinct, effector-specific learning mechanisms.

The picture emerging from an integration of this new finding with prior neural data suggests that an individual’s sensorimotor adaptation ability may depend strongly on neural changes in circuits that are specific to the task in addition to those that are shared across tasks. One candidate mechanism for this type of neural change involves strengthened functional connectivity between the specific effector system’s most relevant sensory cortical regions on the one hand and between its functionally specific motor cortical regions on the other hand. For example, for a speech adaptation task with mechanical loads applied to the mandible, Darainy et al. (100) used partial correlation methods to determine which adaptation-related changes in functional connectivity could not be attributed to activity elsewhere in the involved network. Their results suggested that adaptive motor changes were associated with changes in functional connectivity between left hemisphere auditory and somatosensory cortex (i.e., two sensory modalities whose information is closely integrated during the specific task of speech production; see also Ref. 72). Furthermore, perceptual changes as a result of the adaptation task were associated with changes in functional connectivity between left hemisphere primary motor cortex and inferior frontal gyrus (Broca’s area BA44). Hence, critical aspects of neural plasticity during sensorimotor adaptation occur in system-specific sensory and motor regions. With regard to system-specific motor regions, a study on speech auditory-motor adaptation with formant-shifted feedback also demonstrated that subthreshold repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) over tongue primary motor cortex (M1) disrupted adaptation (but not vowel production itself), whereas there was no effect when the stimulation was applied over hand M1 (101). Interpreting our data in this context, behavioral adaptation profiles across different paradigms such as visuomotor reach adaptation and auditory-motor speech adaptation are likely to reflect task-dependent individual differences in neural plasticity.

Within-Task Correlation Results Differed between Reach Adaptation and Speech Adaptation

Results from within-task correlational analyses further demonstrated the independence of reach and speech adaptation abilities. First, adaptation extent was correlated between the gradual and sudden conditions for reaching but not for speaking. This significant correlation for reach visuomotor adaptation is consistent with previous reports that individual adaptation differences may be conserved across tasks such as adaptation to different force fields (22) and suggests that visuomotor adaptation under the two different perturbation schedules is driven, at least in part, by the same underlying recalibration mechanism. It is interesting, however, that we did not find such a correlation between performance with sudden versus gradual perturbations for speech auditory-motor adaptation. This is particularly intriguing given the aforementioned widely held view that reach visuomotor adaptation in these two conditions depends on different relative contributions from explicit strategy use and implicit learning processes (e.g., Ref. 94) whereas speech adaptation is entirely implicit in both conditions. Indeed, even in speech adaptation studies with sudden formant-shift perturbations, participants report that they are not aiming to change their articulation of the target utterances at any time during the task (77). In light of the latter finding and the fact that the extent of formant adaptation is also unaffected by instructing participants to compensate, to ignore the feedback, or to avoid compensating (87), there is currently no satisfactory explanation for why there is not even a correlation between performance with the two perturbation schedules within speech auditory-motor adaptation.

Second, adaptation extent was correlated with additional measures of performance for reaching but not for speaking. In the reach task, larger within-trial corrections during the perturbation phase were associated with reduced adaptation extent in the gradual condition (Fig. 4A), and increased trial duration in the perturbation phase was associated with more complete adaptation in the sudden condition (Fig. 4C). Given that these correlations were inconsistent between the two perturbation conditions, it is unclear at this time what can be inferred regarding the relationship between upper limb visuomotor adaptation and feedback-based online corrections, but further exploration is warranted. For the present purposes, the finding of two statistically significant correlations between within-trial measures of performance and reach visuomotor adaptation, in the absence of any such correlations for speech auditory-motor adaptation, provides initial evidence suggesting that the relationship between learning based on prior sensory prediction errors and online corrections based on feedback gain adjustments also differs between the two effector systems studied here. Consequently, our within-task analyses also support the conclusion that factors that may explain interindividual variability in limb adaptation (e.g., Refs. 16–19) are unlikely to apply to other forms of adaptation such as auditory-motor learning for speech production.

Individual Participant Learning Profiles Differ between Reach Adaptation and Speech Adaptation

Finally, we found that reach visuomotor adaptation and speech auditory-motor adaptation also differed in terms of their individual participant learning profiles. Specifically, when we fitted both an exponential and a linear function to the individual participant adaptation curves, the increased goodness-of-fit benefit provided by the exponential function was statistically significantly larger for the reach adaptation data than for the speech adaptation data. It is, of course, well documented that reach visuomotor adaptation is exponential in nature, and it has been proposed that the fast component of this adaptation reflects explicit strategy use that contributes primarily during the early phase of learning whereas the slower component is driven mostly by implicit learning (89). In contrast, the present data indicate that the goodness of fit for individual participant speech auditory-motor adaptation data improved much less from the use of an exponential fit over a linear fit. That is, speech adaptation showed a slower, more steady time course without distinguishable fast and slow components, thereby providing additional support for the idea that the underlying mechanisms for sensorimotor adaptation differ between the two effector systems under investigation. As was the case for some of the other findings discussed above, one might argue once again that this difference is likely to result from speech adaptation being an entirely implicit form of learning (77, 87). Further cross-system studies will be needed, however, to gain a thorough understanding of the involvement of system-specific processes and neural substrates, in particular because recent work has challenged the idea that implicit learning is necessarily slower (102).

Conclusions and Future Directions

Taken together, our key findings provide compelling evidence for the conclusion that individual sensorimotor adaptation characteristics are independent across reach visuomotor adaptation and speech auditory-motor adaptation. In other words, adaptation in these two different sensorimotor systems seems to rely at least in part on mechanisms that are distinct and effector specific. These behavioral results are in keeping with computational work suggesting that error sensitivity is much higher for upper limb reach movements than orofacial speech movements (e.g., Refs. 96, 99). Moreover, these behavioral results also align well with recent neuroimaging work suggesting that the critical neural changes associated with adaptation may involve a strengthening of functional connectivity between system-specific sensory regions as well as system-specific motor regions (100).

Our results therefore caution that even with analogous perturbations (here visual and auditory feedback perturbations rather than motion path perturbations) an individual’s sensorimotor learning ability for one effector system is not predictive of that for another sensorimotor system. Furthermore, when studies identify cognitive, behavioral, or neurochemical predictors of individual differences in sensorimotor learning, those predictors may be relevant only for the particular effector system for which they were identified.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data used for this study are openly available via an Open Science Framework (OSF) repository at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/7UVZD.

GRANTS

This research was supported, in part, by Grants R01DC014510 and R01DC017444 from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders awarded to L.M.

DISCLAIMERS

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders or the National Institutes of Health.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.M. conceived and designed research; N.M.K., K.S.K., and R.J.H. performed experiments; N.M.K., K.S.K., P.Z.W., R.J.H., and L.M. analyzed data; N.M.K., K.S.K., P.Z.W., R.J.H., and L.M. interpreted results of experiments; N.M.K. and L.M. prepared figures; N.M.K., K.S.K., P.Z.W., R.J.H., and L.M. drafted manuscript; N.M.K., K.S.K., R.J.H., and L.M. edited and revised manuscript; N.M.K., K.S.K., P.Z.W., R.J.H., and L.M. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Present addresses: N. M. Kitchen, Pennsylvania State College of Medicine, Hershey, PA; K. S. Kim, University of California, San Francisco, CA; R. J. Hermosillo, Department of Pediatrics, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, Masonic Institute for the Developing Brain, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, and Department of Psychiatry, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR.

REFERENCES

- 1. Shadmehr R, Smith MA, Krakauer JW. Error correction, sensory prediction, and adaptation in motor control. Annu Rev Neurosci 33: 89–108, 2010. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huang VS, Haith A, Mazzoni P, Krakauer JW. Rethinking motor learning and savings in adaptation paradigms: model-free memory for successful actions combines with internal models. Neuron 70: 787–801, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Izawa J, Shadmehr R. Learning from sensory and reward prediction errors during motor adaptation. PLoS Comput Biol 7: e1002012, 2011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith MA, Ghazizadeh A, Shadmehr R. Interacting adaptive processes with different timescales underlie short-term motor learning. PLoS Biol 4: e179, 2006. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Taylor JA, Krakauer JW, Ivry RB. Explicit and implicit contributions to learning in a sensorimotor adaptation task. J Neurosci 34: 3023–3032, 2014. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3619-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Taylor JA, Ivry RB. Flexible cognitive strategies during motor learning. PLoS Comput Biol 7: e1001096, 2011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Galea JM, Vazquez A, Pasricha N, de Xivry JJ, Celnik P. Dissociating the roles of the cerebellum and motor cortex during adaptive learning: the motor cortex retains what the cerebellum learns. Cereb Cortex 21: 1761–1770, 2011. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Miall RC, Christensen LO, Cain O, Stanley J. Disruption of state estimation in the human lateral cerebellum. PLoS Biol 5: e316, 2007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ohashi H, Gribble PL, Ostry DJ. Somatosensory cortical excitability changes precede those in motor cortex during human motor learning. J Neurophysiol 122: 1397–1405, 2019. doi: 10.1152/jn.00383.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cressman EK, Henriques DY. Sensory recalibration of hand position following visuomotor adaptation. J Neurophysiol 102: 3505–3518, 2009. doi: 10.1152/jn.00514.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ostry DJ, Darainy M, Mattar AA, Wong J, Gribble PL. Somatosensory plasticity and motor learning. J Neurosci 30: 5384–5393, 2010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4571-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sexton BM, Liu Y, Block HJ. Increase in weighting of vision vs. proprioception associated with force field adaptation. Sci Rep 9: 10167, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46625-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Seidler RD, Mulavara AP, Bloomberg JJ, Peters BT. Individual predictors of sensorimotor adaptability. Front Syst Neurosci 9: 100, 2015. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2015.00100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Seidler RD, Carson RG. Sensorimotor learning: neurocognitive mechanisms and individual differences. J Neuroeng Rehabil 14: 74, 2017. doi: 10.1186/s12984-017-0279-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bastian AJ. Understanding sensorimotor adaptation and learning for rehabilitation. Curr Opin Neurol 21: 628–633, 2008. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328315a293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Anguera JA, Reuter-Lorenz PA, Willingham DT, Seidler RD. Contributions of spatial working memory to visuomotor learning. J Cogn Neurosci 22: 1917–1930, 2010. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Christou AI, Miall RC, McNab F, Galea JM. Individual differences in explicit and implicit visuomotor learning and working memory capacity. Sci Rep 6: 36633, 2016. doi: 10.1038/srep36633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wu HG, Miyamoto YR, Gonzalez Castro LN, Ölveczky BP, Smith MA. Temporal structure of motor variability is dynamically regulated and predicts motor learning ability. Nat Neurosci 17: 312–321, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nn.3616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stagg CJ, Bachtiar V, Johansen-Berg H. The role of GABA in human motor learning. Curr Biol 21: 480–484, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.01.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lametti DR, Quek MY, Prescott CB, Brittain JS, Watkins KE. The perils of learning to move while speaking: one-sided interference between speech and visuomotor adaptation. Psychon Bull Rev 27: 544–552, 2020. doi: 10.3758/s13423-020-01725-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Donchin O, Rabe K, Diedrichsen J, Lally N, Schoch B, Gizewski ER, Timmann D. Cerebellar regions involved in adaptation to force field and visuomotor perturbation. J Neurophysiol 107: 134–147, 2012. doi: 10.1152/jn.00007.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moore RT, Cluff T. Individual differences in sensorimotor adaptation are conserved over time and across force-field tasks. Front Hum Neurosci 15: 692181, 2021. doi: 10.3389/FNHUM.2021.692181/BIBTEX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rabe K, Livne O, Gizewski ER, Aurich V, Beck A, Timmann D, Donchin O. Adaptation to visuomotor rotation and force field perturbation is correlated to different brain areas in patients with cerebellar degeneration. J Neurophysiol 101: 1961–1971, 2009. doi: 10.1152/jn.91069.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arce F, Novick I, Vaadia E. Discordant tasks and motor adjustments affect interactions between adaptations to altered kinematics and dynamics. Front Hum Neurosci 3: 65, 2010. doi: 10.3389/neuro.09.065.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tong C, Wolpert DM, Flanagan JR. Kinematics and dynamics are not represented independently in motor working memory: evidence from an interference study. J Neurosci 22: 1108–1113, 2002. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-01108.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Caudrelier T, Rochet-Capellan A. Changes in speech production in response to formant perturbations: an overview of two decades of research. In: Speech Production and Perception, Vol. 6 Speech Production and Perception: Learning and Memory, edited by Fuchs S, Cleland J, Rochet-Capellan A.. Berlin: Peter Lang, 2019, p. 15–75. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Houde JF, Jordan MI. Sensorimotor adaptation in speech production. Science 279: 1213–1216, 1998. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5354.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Purcell DW, Munhall KG. Adaptive control of vowel formant frequency: evidence from real-time formant manipulation. J Acoust Soc Am 120: 966–977, 2006. doi: 10.1121/1.2217714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rochet-Capellan A, Ostry DJ. Simultaneous acquisition of multiple auditory-motor transformations in speech. J Neurosci 31: 2657–2662, 2011. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6020-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Villacorta VM, Perkell JS, Guenther FH. Sensorimotor adaptation to feedback perturbations of vowel acoustics and its relation to perception. J Acoust Soc Am 122: 2306–2319, 2007. doi: 10.1121/1.2773966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Daliri A, Max L. Stuttering adults’ lack of pre-speech auditory modulation normalizes when speaking with delayed auditory feedback. Cortex 99: 55–68, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2017.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Daliri A, Wieland EA, Cai S, Guenther FH, Chang SE. Auditory-motor adaptation is reduced in adults who stutter but not in children who stutter. Dev Sci 21: e12521, 2018. doi: 10.1111/desc.12521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kim KS, Daliri A, Flanagan JR, Max L. Dissociated development of speech and limb sensorimotor learning in stuttering: speech auditory-motor learning is impaired in both children and adults who stutter. Neuroscience 451: 1–21, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2020.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lametti DR, Rochet-Capellan A, Neufeld E, Shiller DM, Ostry DJ. Plasticity in the human speech motor system drives changes in speech perception. J Neurosci 34: 10339–10346, 2014. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0108-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shiller DM, Sato M, Gracco VL, Baum SR. Perceptual recalibration of speech sounds following speech motor learning. J Acoust Soc Am 125: 1103–1113, 2009. doi: 10.1121/1.3058638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Johnson JF, Belyk M, Schwartze M, Pinheiro AP, Kotz SA. The role of the cerebellum in adaptation: ALE meta-analyses on sensory feedback error. Hum Brain Mapp 40: 3966–3981, 2019. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. O’Reilly JX, Beckmann CF, Tomassini V, Ramnani N, Johansen-Berg H. Distinct and overlapping functional zones in the cerebellum defined by resting state functional connectivity. Cereb Cortex 20: 953–965, 2010. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Meister IG, Boroojerdi B, Foltys H, Sparing R, Huber W, Töpper R. Motor cortex hand area and speech: implications for the development of language. Neuropsychologia 41: 401–406, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0028-3932(02)00179-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tokimura H, Asakura T, Tokimura Y, Oliviero A, Rothwell JC. Speech-induced changes in corticospinal excitability. Ann Neurol 40: 628–634, 1996. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gentilucci M, Campione GC, Dalla Volta R, Bernardis P. The observation of manual grasp actions affects the control of speech: a combined behavioral and transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Neuropsychologia 47: 3190–3202, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gentilucci M. Grasp observation influences speech production: observing grasp and speaking. Eur J Neurosci 17: 179–184, 2003. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gentilucci M, Benuzzi F, Gangitano M, Grimaldi S. Grasp with hand and mouth: a kinematic study on healthy subjects. J Neurophysiol 86: 1685–1699, 2001. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.4.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gentilucci M, Santunione P, Roy AC, Stefanini S. Execution and observation of bringing a fruit to the mouth affect syllable pronunciation. Eur J Neurosci 19: 190–202, 2004. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gentilucci M, Stefanini S, Roy AC, Santunione P. Action observation and speech production: study on children and adults. Neuropsychologia 42: 1554–1567, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bernardis P, Bello A, Pettenati P, Stefanini S, Gentilucci M. Manual actions affect vocalizations of infants. Exp Brain Res 184: 599–603, 2008. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-1256-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Higginbotham DR, Isaak MI, Domingue JN. The exaptation of manual dexterity for articulate speech: an electromyogram investigation. Exp Brain Res 186: 603–609, 2008. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-1265-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]