Abstract

Pericytes, like vascular smooth muscle cells, are perivascular cells closely associated with blood vessels throughout the body. Pericytes are necessary for vascular development and homeostasis, with particularly critical roles in the brain, where they are involved in regulating cerebral blood flow and establishing the blood-brain barrier. A role for pericytes during neurovascular disease pathogenesis is less clear—while some studies associate decreased pericyte coverage with select neurovascular diseases, others suggest increased pericyte infiltration in response to hypoxia or traumatic brain injury. Here, we used an endothelial loss-of-function Recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin kappa J region (Rbpj)/Notch mediated mouse model of brain arteriovenous malformation (AVM) to investigate effects on pericytes during neurovascular disease pathogenesis. We tested the hypothesis that pericyte expansion, via morphological changes, and Platelet-derived growth factor B/Platelet-derived growth factor receptor β (Pdgf-B/Pdgfrβ)-dependent endothelial cell-pericyte communication are affected, during the pathogenesis of Rbpj mediated brain AVM in mice. Our data show that pericyte coverage of vascular endothelium expanded pathologically, to maintain coverage of vascular abnormalities in brain and retina, following endothelial deletion of Rbpj. In Rbpj-mutant brain, pericyte expansion was likely attributed to cytoplasmic process extension and not to increased pericyte proliferation. Despite expanding overall area of vessel coverage, pericytes from Rbpj-mutant brains showed decreased expression of Pdgfrβ, Neural (N)-cadherin, and cluster of differentiation (CD)146, as compared to controls, which likely affected Pdgf-B/Pdgfrβ-dependent communication and appositional associations between endothelial cells and pericytes in Rbpj-mutant brain microvessels. By contrast, and perhaps by compensatory mechanism, endothelial cells showed increased expression of N-cadherin. Our data identify cellular and molecular effects on brain pericytes, following endothelial deletion of Rbpj, and suggest pericytes as potential therapeutic targets for Rbpj/Notch related brain AVM.

Keywords: brain, endothelial, Notch, pericyte, Rbpj, vascular, arteriovenous malformation (AVM)

Introduction

Brain arteriovenous malformation (AVM) is a neurovascular disease characterized by multiple vascular abnormalities, including arteriovenous (AV) shunting—formation of direct connections between arteries and veins at the expense of capillary networks. Blood flows rapidly through these abnormal connections; thus, AVM vessels are prone to rupture, which can lead to devastating outcomes (Do Prado et al., 2019). Treatment methods for brain AVM are limited (Raper et al., 2020); therefore, it is important to understand the mechanisms of disease pathogenesis in order to develop novel therapies. Molecular and genetic studies from human tissue and animal models have revealed several signaling pathways involved in brain AVM pathogenesis, namely TGFβ (Bourdeau et al., 1999; Satomi et al., 2003; Park et al., 2009), Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK (Nikolaev et al., 2018; Fish et al., 2020), and Notch (Murphy et al., 2014; Nielsen et al., 2014). Collectively, these data support the emerging view that diverse mechanisms underlie brain AVM pathologies and diverse therapies must be developed to treat brain AVM patients safely and effectively.

Endothelial Notch signaling plays an essential role in vessel remodeling, angiogenesis, and endothelial cell specification in many vascular beds, including those in the central nervous system (CNS) (Krebs et al., 2000; Fernández-Chacón et al., 2021). We previously developed a mouse model of brain AVM, by selectively deleting Rbpj—a transcriptional regulator of canonical Notch signaling—from early postnatal endothelium in mice. Mutant mice developed AV shunts, displayed abnormal endothelial cell (EC) gene expression (suggesting disruption of arterial vs. venous EC identity), and showed altered smooth muscle cell coverage on the abnormal AV connections. In this mouse model, advanced brain AVM pathologies and 50% lethality were reported just 2 weeks post EC-Rbpj deletion (Nielsen et al., 2014); thus, endothelial Rbpj is required to prevent brain AVM formation in the early postnatal brain vasculature. Interestingly, careful regulation of Notch signaling is critical, as both loss and gain of function mutations in Notch signaling molecules result in abnormal vasculature in mice (Krebs et al., 2004; Murphy et al., 2014; Nielsen et al., 2014; Cuervo et al., 2016).

Pericytes are specialized perivascular cells closely associated with microvessels throughout the body. Pericytes and ECs are separated by a shared basement membrane, except at points of closer apposition called peg-and-socket contacts, which are typically found at the pericyte cytosolic processes that enwrap microvessels. Pericytes vary in morphology, function, and molecular signature, depending on where and when they are present (Uemura et al., 2020). Pericytes are necessary for vascular development and homeostasis and are particularly critical to brain capillaries for regulating cerebral blood flow (Bell et al., 2010, 2020; Gonzales et al., 2020) and establishing the blood-brain barrier (BBB) (Armulik et al., 2010; Daneman et al., 2010). Such developmental and functional influences on microvessels rely on intercellular signaling events between ECs and pericytes, permitting a “molecular crosstalk” that regulates vascular homeostasis.

Notch signaling is involved in EC-pericyte communication and association, by influencing pericyte maturation and recruitment to vessels (Liu et al., 2010; Gu et al., 2012). Notch achieves this, in part, by regulating Pdgf-B-Pdgfrβ signaling (Jin et al., 2008; Yao et al., 2011). In vasculature, Pdgf-B ligands are expressed and secreted by ECs (Battegay et al., 1994), while their membrane-localized Pdgf receptors are expressed primarily by pericytes (Winkler et al., 2010). In the CNS, impaired Pdgf-B-Pdgfrβ signaling leads to reduced pericyte coverage, vessel instability, and compromised BBB function (Armulik et al., 2010; Daneman et al., 2010; Nikolakopoulou et al., 2017). N-cadherin, another molecule involved in EC-pericyte interaction, is a membrane-spanning protein expressed on both ECs and pericytes (Gerhardt et al., 2000). N-cadherin mediates EC-pericyte communication, downstream of Pdgf-B-Pdgfrβ signaling, via direct contact between neighboring cells, and one study has implicated Notch and TGFβ as co-activators of N-cadherin (Li et al., 2011). Thus, Notch signaling promotes pericyte recruitment and adhesion to microvessels during normal neurovascular morphogenesis.

While pericytes are important for development and maintenance of the neurovascular system, a role for pericytes during neurovascular disease pathogenesis is less clear. Pericyte response to neurovascular disease (e.g., cerebrovascular and neurodegenerative diseases) varies, and pericytes adapt to their environment by changing morphology, undergoing differentiation, secreting growth factors, and altering vessel permeability to allow select solutes to reach affected brain tissue (Hirunpattarasilp et al., 2019; Lendahl et al., 2019). While several studies associate decreased pericyte coverage with neurovascular diseases like brain AVM (Chen et al., 2013; Tual-Chalot et al., 2014; Crist et al., 2018; Winkler et al., 2018; Diéguez-Hurtado et al., 2019; Nadeem et al., 2020), others demonstrate pericyte hypertrophy, tissue infiltration, and proliferation in response to hypoxia, ischemic stroke, or traumatic brain injury (Tagami et al., 1990; Bonkowski et al., 2011; Cai et al., 2017; Birbrair, 2019). Despite disparate consequences to pericytes during CNS diseases, these important vascular cells are indeed affected and may play actively pathogenic roles; thus, targeting pericytes in neurovascular anomalies, like brain AVM, is a promising therapeutic avenue (Lebrin et al., 2010; Thalgott et al., 2015; Geranmayeh et al., 2019).

We investigated consequences to pericytes in our endothelial Rbpj mediated model of brain AVM, and we found that CNS pericytes pathologically expanded in a regionally and temporally regulated manner, as compared to controls. In Rbpj mutant cerebellum and cortex (but not brain stem), increased pericyte area kept pace with increased endothelial area, thus maintaining pericyte coverage of microvessels. Pathological pericyte expansion increased in severity as features of brain AVM (AV shunting) progressed; however, there was no evidence for early pericyte reduction, indicating temporal regulation of brain pericytes by endothelial Rbpj. Pericyte expansion was not caused by increased cell proliferation, but rather by hypertrophy of cytosolic pericyte processes on enlarging AV connections. Rbpj dependent EC-pericyte communication was affected in mutant brain vasculature, as isolated brain pericytes showed decreased expression of Pdgfrβ, N-cadherin, and CD146—all of which are molecules involved in pericyte recruitment to and association with microvessels. By contrast, isolated brain ECs showed increased expression of N-cadherin, perhaps in response to downregulation by pericytes. Our results indicate that pathological pericyte expansion progresses in concert with AV shunt formation, during Rbpj mediated brain AVM; thus, our data challenge a working hypothesis in the field, which posits that decreased pericyte coverage necessarily precedes brain AVM formation. Collectively, our findings define a novel role for Rbpj in postnatal brain endothelium—to prevent pathological pericyte expansion and to maintain pericyte morphology. Our study also refines the current view of pericyte involvement in neurovascular disease and the therapeutic potential of targeting and manipulating pericytes in brain AVM.

Materials and methods

Mice

All experiments were completed in accordance with Ohio University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) protocol number 16-H-024. Mouse lines Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2 (Sörensen et al., 2009), Rbpjflox (Tanigaki et al., 2002), Rosa26mT/mG (Muzumdar et al., 2007), and Cspg4(NG2)-DsRed (Zhu et al., 2008) were, respectively, provided by Taconic Biosciences (in accord with Breeding Agreement), Tasuku Honjo (Kyoto University), and the last two by Jackson Laboratory [GT(Rosa)26SorTM4(ACTB–tdTomato–EGFP)Luo: JAX stock #007576 and Tg(Cspg4-DsRed.T1)1Akik: JAX stock #008241]. At P1 and P2, 100 μg of Tamoxifen (Sigma) in 50 μL of peanut oil (Planters) was injected intragastrically, as previously described (Nielsen et al., 2014). PCR based genotyping was performed, as previously described (Nielsen et al., 2014), except Rosa26mT/mG and Cspg4(NG2)-DsRed genotyping was determined by tail biopsy tissue fluorescence, using a Nikon NiU microscope.

Tissue harvest and preparation

Brain and retina tissue was harvested following intracardial perfusion and simultaneous euthanasia by exsanguination. Perfusion solution depended on subsequent analysis, as follows: 1% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for anti-CD13, anti-N-cadherin, anti-Pdgfrβ, NG2-DsRed; phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for anti-desmin. Endothelial cells were genetically labeled with mGFP or were perfusion labeled with intravenous Dylight488 Lycopersicon esculentum (tomato) lectin (Vector Laboratories) (50 μg lectin/125–150 μL PBS). For tissue sections, brains were hemisected, cryopreserved in 30% sucrose, and stored at −80°C. Mid-sagittal cryosections, 10–12 μm thick, were collected with a CM-1350 cryostat (Leica) and stored at −80°C. For mid-sagittal sections, the following brain regions were imaged: (i) frontal cortex near the pial surface was imaged; (ii) cerebellum lobule V, VIA, VIB, or VII was imaged, as these lobules are consistently affected in RbpjiΔEC mutants (Chapman et al., 2022); (iii) brain stem immediately caudal to the pons (as identified by the pontine flexure) was imaged. For whole cortex preparation, a 2–3 mm thick slice of frontal cortex was removed with a scalpel. For whole retina preparation, retinae were dissected and splayed, according to published methods (Tual-Chalot et al., 2013).

Immunostaining and 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine incorporation

Immunostaining was performed with modifications from standard protocol previously described (Nielsen and Dymecki, 2010). Primary antibody dilutions: rat anti-CD13 (MCA2183GA) (1:500) (AbD Serotec); mouse anti-desmin (D33) (1:50) (DAKO/Agilent); mouse anti-N-cadherin (3B9) (1:300) (Invitrogen); rat anti-Pdgfrβ (CD140b) (1:50) (Invitrogen). Secondary antibodies: Cy3 donkey anti-rat; Alexa647 donkey anti-mouse; Alexa647 donkey anti-rat (all dilutions 1:500) (Jackson ImmunoResearch). For EdU incorporation assay, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 10 μg/gram of body weight with EdU at P5–7 or P8–10 or P12–14. On the day of harvest (P7 or P10 or P14), tissue was harvested 2 h post-injection. Detection of EdU used Click-iT™ Plus chemistry, with AlexaFluor® 647 component following manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). Cell nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Tissue sections were mounted with ProLong Gold™ (Invitrogen) and coverslipped for imaging.

Single cell suspension and cell isolation

Whole brain tissue was mechanically and chemically dissociated by Neutral Protease (Worthington), Collagenase Type II (Worthington), Deoxyribonuclease (Worthington), and Complete 1X DMEM (Gibco) with 5% heat inactivated Fetal Bovine Serum (Gibco) and 1% PenStrep (Gibco). 70% Percoll (Cytiva) density gradient was used to separate single cell suspension into cellular fractions. Endothelial cells were labeled with CD31 microbeads (1:10) (mouse, Miltenyi Biotec). Pericytes were labeled with primary antibody rat anti-mouse CD13 (1:50) (Bio-Rad) and secondary anti-rat IgG MicroBeads (1:10) (Miltenyi Biotec). Select cell populations were isolated via magnetic activated cell sorting using LS separation columns (QuadroMACS™ Starting Kit, Miltenyi Biotec). To reduce endothelial cell contamination in the pericyte samples, endothelial cells were removed prior to collecting pericytes. Cell pellets were stored at −80°C until RNA extraction.

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from isolated cells using RNeasy Plus Micro Kit (including genomic DNA removal columns) (Qiagen), and concentration was measured using NanoDrop One spectrophotometer. For Reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-Qpcr), RNA input was 10 ng per well (96-well plate format). qScript One-Step SYBR Green RT-qPCR (Quantabio) was used to run qPCR with cycling in a CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (BioRad), using CFX Maestro 2.0 Software for Windows PC (BioRad). Tissue from 3 to 5 brains was pooled for each biological sample. Each biological sample was run in technical triplicate. Cycling conditions were as follows: (1) 49°C 10 min; (2) 95°C 5 min; (3) 95°C 10 s; (4) 58°C 30 s; (5) repeat steps 3–4 39 times; (6) melt curve 55–95°C 5 s, in 0.5°C increments. Quantification was performed using the comparative CT method with Microsoft Excel software (Schmittgen and Livak, 2008). Values were normalized to expression of reference genes β-actin for ECs and Rplpo for pericytes. Reference genes were selected based on test runs for three reference genes (β-actin, Gapdh, Rplpo) per cell type—genes with consistent results across triplicate runs were selected. All sample replicates were used in quantification analyses (outliers were not identified; no samples were removed from analysis). Primer sequences and information relevant to MIQE Guidelines are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Western blotting

Protein lysates were prepared in 1X RIPA buffer from isolated cells (see above). Protein concentration was estimated using Precision Red (Cytoskeleton, Inc.) and NanoDrop One spectrophotometer. Proteins were separated using an 8% polyacrylamide separating/resolving gel, 4% stacking gel, and electrophoresis. Protein was transferred to PVDF membrane, and membrane was blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin in tris-buffered saline with Tween-20, before incubating with primary antibodies. Primary antibody dilutions: rabbit anti-gapdh (1:1,000) (Cell Signaling Technologies); mouse anti-N-cadherin (3B9) (1:1,000) (Invitrogen); rat anti-Pdgfrβ (CD140b) (1:1,000) (Invitrogen); rabbit anti-Rbpj (1:1,000) (Cell Signaling Technologies). HRP-conjugated secondary antibody dilutions: anti-mouse (1:1,000); anti-rabbit (1:1,000); anti-rat (1:1,000) (Cell Signaling Technologies). Chemiluminescent substate was applied to the membrane and bands were detected and quantified with BioRad ChemiDoc XRS+ and ImageLab software.

Fluorescence imaging

Epifluorescent images were acquired using a Nikon NiU microscope and NIS Elements software. Confocal fluorescent images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM 510 laser scanning microscope system and Upright Zen software. Confocal Z-stacks ranged from 36 to 40 slices, at 2 μm steps, and were projected at maximum intensity.

Quantification and statistical analysis

For pericyte ensheathment ratio, following retina imaging, a 10 by 10 grid was overlayed with the mGFP+ endothelial cell images and desmin+ or CD13+ pericyte images in Adobe Photoshop (Creative Cloud). Points of intersection between the grid and positive cells were counted, modified from previously published protocols (Chan-Ling et al., 2004; Hughes et al., 2007), as a proxy for measuring changes to cell area or direct pericyte coverage of endothelium. Statistical analysis was completed using Prism software (GraphPad). Except for qPCR data (see above), unpaired Student’s t-tests with Welch’s correction were used to compare values between control and mutant mice. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, ns = not significant).

Results

Central nervous system pericyte area was pathologically expanded by P10 in cerebellum and by P14 in frontal cortex and retina, following endothelial deletion of Rbpj from birth

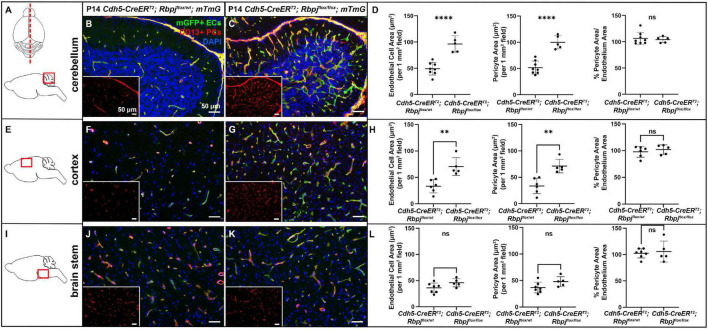

To delete Rbpj from ECs in a temporally restricted manner, we bred Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2; Rbpjflox/wt and Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2; Rbpjflox/flox, hereafter referred to as control and RbpjiΔEC mutant mice, and we administered Tamoxifen to induce endothelial Rbpj deletion at postnatal day (P) 1 and P2 (Nielsen et al., 2014). Effective deletion of Rbpj from ECs was confirmed by P7 in brain ECs isolated from RbpjiΔEC mice, as compared to controls (Supplementary Figure 1). This corroborated published data that showed loss of Rbpj protein from cortical ECs and cerebellum ECs (Nielsen et al., 2014; Chapman et al., 2022) in P14 RbpjiΔEC brain tissue, as compared to controls. To determine whether total pericyte bed area, within mid-sagittal section through brain tissue, was altered in RbpjiΔEC mice, we immunostained against the pericyte marker CD13 and measured CD13+ area per tissue area. To determine total endothelial area, we genetically labeled ECs with mGFP from the Cre-responsive Rosa26mT/mG (mTmG) allele (Nielsen et al., 2014) and measured mGFP+ area per tissue area. By P14, CD13+ pericyte area and mGFP+ endothelial area (per brain tissue area) increased in RbpjiΔEC mutant cerebellum (Figures 1A–D) and cortex (Figures 1E–H), but not in brain stem (Figures 1I–L), as compared to controls [note that our endothelial area results were similar to previously published results that showed increased vascular density in P14 RbpjiΔEC mutants, as compared to controls (Nielsen et al., 2014)]. Interestingly, the percentage of pericyte area per endothelial area was not changed in mutant vs. control (right graphs in Figures 1D,H,L), suggesting that overall pericyte coverage of brain vessels did not change. Rather, pericyte expansion kept pace with pathological endothelial expansion. To illustrate pericyte-microvessel congruency and coverage of microvessels, we acquired higher magnification images of CD13+ pericytes and mGFP+ microvessels in P14 control and mutant cerebellum (Supplementary Figures 2B,C), cortex (Supplementary Figures 2D,E), and brain stem (Supplementary Figures 2F,G). Because no pan-pericyte marker has been identified to date, we repeated our pericyte-positive area measurements using tissue immunostained against the pericyte marker desmin. Using desmin+ pericytes and Dylight488-lectin+ ECs for area measurements, we found similarly increased pericyte and endothelial expansion in P14 RbpjiΔEC mutant cerebellum (Supplementary Figures 3A–D) and frontal cortex (Supplementary Figures 3E–H), but not brain stem (Supplementary Figures 3I–L), as compared to controls. Percentage pericyte/endothelial area was not changed in any brain region, indicating desmin+ pericyte expansion kept pace with endothelial expansion (right graphs in Supplementary Figures 3D,H,L). These data suggest that endothelial Rbpj is required, in different brain regions, to prevent pericytes from expanding along with expanding endothelium in the early postnatal brain.

FIGURE 1.

CD13-positive cortex and cerebellum pericyte area expanded and kept pace with expanded endothelium at P14, following endothelial deletion of Rbpj. In all tissue panels, CD13+ pericytes (PCs) (red), mGFP+ ECs (green), DAPI+ nuclei (blue); insets show CD13+ pericytes only. (A) Upper schematic indicates mid-sagittal plane of section through brain. Lower schematic indicates cerebellum region shown. (B,C) mGFP+ endothelial area and CD13+ pericyte area pathologically expanded in P14 RbpjiΔEC cerebellum, as compared to controls. Quantified in (D) endothelial area P < 0.0001; pericyte area P < 0.0001. Percentage of pericyte area/endothelial area did not change (right graph in D; P = 0.7048. N = 8 controls and N = 5 mutants. (E) Schematic indicates cortex region shown. (F,G) mGFP+ endothelial area and CD13+ pericyte area pathologically expanded in P14 RbpjiΔEC cortex, as compared to controls. Quantified in (H) endothelial area P = 0.0022; pericyte area P = 0.0016. Percentage of pericyte area/endothelial area did not change (right graph in H; P = 0.5015). N = 6 controls and N = 5 mutants. (I) Schematic indicates brainstem region shown. (J,K) mGFP+ endothelial area and CD13+ pericyte area did not change in P14 RbpjiΔEC brain stem, as compared to controls. Quantified in (L) endothelial area P = 0.0835; pericyte area P = 0.0799. Percentage of pericyte area/endothelial area did not change (right graph in L; P = 0.6973). N = 7 controls and N = 5 mutants. **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

Because brain AVM has been correlated with pericyte reduction in other studies, and to examine pericyte coverage at different timepoints post-endothelial Rbpj deletion, we analyzed pericyte area from pre-brain AVM (P7) and from earlier (P10)- and later (P21)-stage brain AVM. While the precise onset of RbpjiΔEC brain AVM in mice has not been reported, previous work showed that increased AV connection (microvessel) diameter appeared around P8–P10 (Nielsen et al., 2014). Thus, we decided to analyze brain pericyte area at P7, a timepoint before features of brain AVM developed. In P7 RbpjiΔEC mutants, as compared to controls, endothelial area was not increased (Supplementary Figures 4A–C,E–G, quantified in left graphs in D,H), suggesting that endothelial expansion, a feature of brain AVM onset, had not yet occurred. At P7, CD13+ pericytes were observed in cerebellum and cortex of controls and RbpjiΔEC mutants (Supplementary Figures 4A–C,E–G, middle graphs in D,H), and pericyte coverage of microvessels was similar in controls and RbpjiΔEC mutants (Supplementary Figure 4, right graphs in D,H). These data indicate that brain pericytes were present, prior to the onset of brain AV features, and suggest that pericyte reduction is likely not necessary for RbpjiΔEC brain AVM to form. In P10 RbpjiΔEC mutants, as compared to controls, pericytes were present in all brain regions analyzed; however, increased CD13+ pericyte area and mGFP+ endothelial area was only seen in cerebellum, with pericyte expansion in pace with endothelial expansion (Supplementary Figures 5A–D). Increased CD13+ pericyte area and mGFP+ endothelial area was not observed in P10 RbpjiΔEC mutant cortex (Supplementary Figures 5E–H) or brain stem (Supplementary Figures 5I–L), as compared to controls. Using desmin as a marker for P10 pericytes, we did not measure any changes in desmin+ pericyte area in any brain region from RbpjiΔEC mutant vs. control (Supplementary Figures 6A–L). To determine whether pericytes were still present (and pathologically expanded) on vessels after advanced AV shunts have formed, we next analyzed P21 brain tissue. We found increased mGFP+ endothelial area and CD13+ pericyte area in RbpjiΔEC cerebellum (Supplementary Figures 7A–D) and cortex (Supplementary Figures 7E–H), but not in brain stem (Supplementary Figures 7I–L), as compared to controls. Pericyte area expanded in concert with endothelial area, as the percentage of pericyte area/endothelial area did not change in RbpjiΔEC vs. control brain tissue (right graph in Supplementary Figure 7L). A summary of RbpjiΔEC brain pericyte expansion, over time and in select brain regions, is included in Table 1. These data, coupled with the previous finding that only 50% of RbpjiΔEC mice survive to P14 (Nielsen et al., 2014), highlighted P14 as a timepoint for further analyses. Together, our findings suggest a temporal requirement for endothelial Rbpj to prevent pathological pericyte expansion in the early postnatal brain.

TABLE 1.

Summary of regional and temporal pericyte expansion (as measured by different pericyte markers) in the CNS vasculature, following endothelial deletion of Rbpj.

| Central nervous system region | Degree of postnatal (P) pericyte expansion in RbpjiΔEC vs. control |

|||

| P10 | P14 | P21 | ||

| Cerebellum | ↑ CD13 | ↑↑↑↑ CD13 | ↑↑ CD13 | |

| no desmin | ↑↑ desmin | |||

| Cortex (frontal) | no CD13 | ↑↑ CD13 | ↑ CD13 | |

| no desmin | ↑↑ desmin | |||

| Brain stem | no CD13 | no CD13 | no CD13 | |

| no desmin | no desmin | |||

| Retina | no CD13 | ↑ CD13 | ||

| ↑↑↑ desmin | ↑↑↑ desmin | |||

↑ represents *(P < 0.05) statistical significance.

↑↑ represents **(P < 0.01) statistical significance.

↑↑↑ represents ***(P < 0.001) statistical significance.

↑↑↑↑ represents ****(P < 0.0001) statistical significance.

The mouse retina is often used in vascular studies as part of the CNS and as a proxy for studies in the brain. While retinal AVM have not been reported in endothelial Rbpj mutants, previous studies showed that loss of Notch signaling molecules from ECs leads to increased angiogenic sprouting and branch points in the leading edge of early postnatal retinal vasculature (Hellström et al., 2007). Given our results from brain vasculature, we hypothesized that endothelial Rbpj may also be required in the neonatal retinal vasculature to prevent pericyte expansion. We dissected eyes from P10 to P14 control and RbpjiΔEC mice and used a whole mount preparation to splay the eye and expose the retina for immunostaining and tissue mounting (Supplementary Figure 8A). We labeled pericytes with CD13 and desmin markers, and because we stained whole tissue, we measured a pericyte ensheathment ratio (PER) as a proxy for pericyte+ and endothelium+ area measurements. Our PER method was adapted from previous studies with retinal ECs and pericytes (Chan-Ling et al., 2004; Hughes et al., 2007). We overlayed a 10x10 grid onto a retina image (Supplementary Figure 8B) and counted the number of intersection points at which pericyte+ or EC+ marker was observed (Supplementary Figures 8C,D,F,G). At P10, we did not observe increased number of EC+ intersection points in control vs. RbpjiΔEC (left graphs in Supplementary Figures 8E,H), in agreement with previous data suggesting that endothelium had not yet expanded in RbpjiΔEC brain. At P10, we observed increased number of desmin+ pericyte intersection points but not CD13+ points (middle graphs in Supplementary Figures 8E,H). Consistent with data from brain vessels, the ratio of pericyte+/EC+ intersection points in RbpjiΔEC vs. controls was not affected by P10 (right graphs in Supplementary Figures 8E,H). In P14 retina, the number of EC+ and pericyte+ intersection points significantly increased in RbpjiΔEC, as compared to controls, using either CD13 (Supplementary Figures 8I–K) or desmin (Supplementary Figures 8L–N) to label pericytes. However, the ratio of pericyte+/EC+ intersection points in RbpjiΔEC vs. controls was not affected (right graphs in Supplementary Figures 8K,N). A summary of RbpjiΔEC retinal pericyte expansion, over time, is included in Table 1. These data suggest that pericyte expansion kept pace with endothelial expansion in the early postnatal retinae, following endothelial deletion of Rbpj.

The number of pericytes per brain vessel length increased by P14, without increased cell proliferation, following endothelial deletion of Rbpj from birth

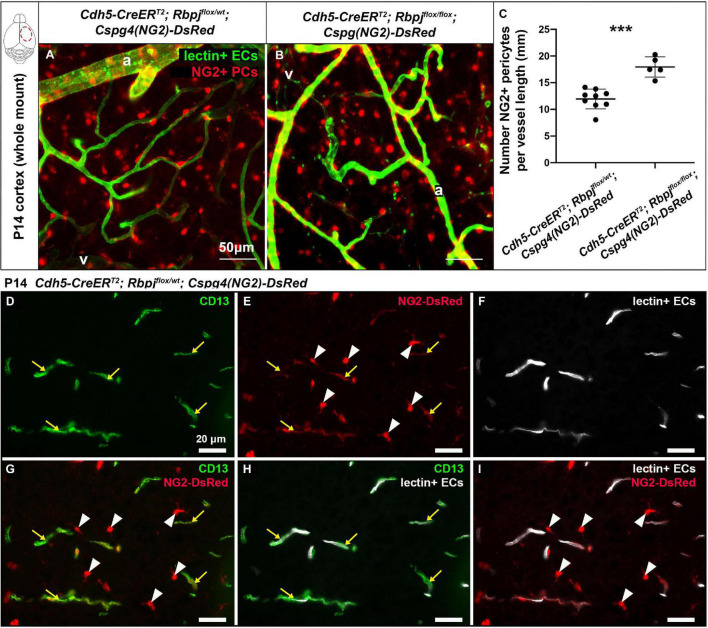

To determine whether pericyte expansion resulted from an increased number of pericytes, we counted the number of pericytes, per vessel length, on AV connections (4–6 μm diameter capillaries in control and > 12 μm diameter AV shunts in RbpjiΔEC brains). We used another pericyte marker, the transgene Cspg4(NG2)-DsRed (Zhu et al., 2008), which does not label pericyte processes, so that individual pericytes could be readily distinguished. We bred the transgene into our P14 control and RbpjiΔEC mice and counted Cspg4(NG2)-DsRed+ pericytes per Dylight488-lectin+ vessel length (mm). Using a whole mount cortical preparation so that intact vessels and pericytes could be visualized, described in Nielsen et al. (2014), we found an increased number of pericytes per mm of vessel in RbpjiΔEC cortex at P14, as compared to controls (Figures 2A–C). Because Cspg4(NG2) is highly expressed by oligodendrocyte precursor cells (Polito and Reynolds, 2005; Zhu et al., 2008), we wanted to validate that the cells we identified as Cspg4(NG2)+ and directly juxtaposed to vessels were indeed pericytes. We immunostained Dylight488-lectin-injected, Cspg4(NG2)-DsRed brain tissue against CD13 in P14 controls. We found CD13+/Cspg4(NG2)-DsRed+ pericytes were identified adjacent to lectin+ microvessels (Figures 2D–I), while CD13-/Cspg4(NG2)-DsRed+ oligodendrocyte precursor cells were not found near vessels (Figures 2E,G,I).

FIGURE 2.

Endothelial Rbpj deficiency led to increased number of NG2-positive pericytes per vessel length by P14. (A,B) In P14 whole mount cortex, pericytes were labeled by the Cspg4(NG2)-DsRed transgene (red). ECs were labeled by Dylight488-lectin (green). NG2+ pericytes (PCs) were counted, and the corresponding lectin+ vessel length [between arteries (a) and veins (v)] was measured. The number of NG2+ pericytes per millimeter of vessel length significantly increased in RbpjiΔEC mutants, as compared to controls (quantified in C; P = 0.0004, N = 9 controls and N = 5 mutants). (D–I) P14 Cspg4(NG2)-DsRed (red) mid-sagittal brain tissue sections were immunostained against CD13 (green), and vessels were highlighted with Dylight488-lectin (white). (D) CD13 labeled pericytes; (E) Cspg4(NG2)-DsRed genetically labeled pericytes (yellow arrows) and oligodendrocyte precursor cells (white arrowheads); (F) Perfused Dylight488-lectin labeled ECs within blood vessels. (G) Co-labeling showed CD13+/Cspg4(NG2)-DsRed+ pericytes (yellow arrows) and CD13-/Cspg4(NG2)-DsRed+ oligodendrocyte precursor cells (white arrowheads). (H,I) Pericytes were found adjacent to lectin+ vessel, while oligodendrocyte precursor cells were not found near vessels. ***P < 0.001.

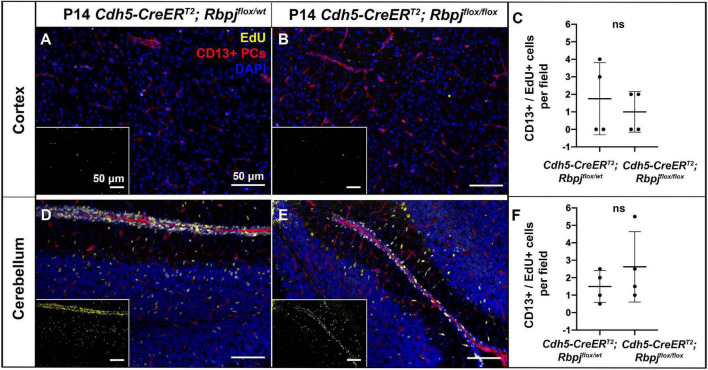

To assess pericyte proliferation during AV shunt formation, we initiated EdU incorporation experiments during incremental time periods before P14. We administered EdU on three consecutive days at P5–7, P8–10, P12–14, and harvested tissue on P7, P10, P14, 2 h post-EdU. We counted double-labeled EdU+ and CD13+ pericytes in mid-sagittal brain tissue sections. Overall, we found very few proliferative pericytes in control and mutant brain tissue. Our analysis did not detect a significant difference in the number of proliferative pericytes (per brain tissue field) between RbpjiΔEC and control mice, in cerebellum or cortex, and at all timepoints analyzed (P14 cortex, Figures 3A–C; P14 cerebellum Figures 3D–F) (P7 cortex, Supplementary Figures 9A–C; P7 cerebellum Supplementary Figures 9D–F; P10 cortex, Supplementary Figures 9G–I; P10 cerebellum Supplementary Figures 9J–L). Taken together, these results suggest that the increased number of pericytes per vessel length was not caused by increased cell proliferation but by another mechanism, perhaps related to another cellular change to pericytes and/or to changes in the RbpjiΔEC microvessels.

FIGURE 3.

Endothelial deletion of Rbpj did not lead to increased CD13-positive pericyte proliferation from P12 to P14 in cortex or cerebellum. In all tissue panels, CD13+ pericytes (PCs) (red), EdU+ nuclei (yellow), DAPI+ nuclei (blue). (A,B) Mice were administered EdU at P12, P13, P14. Mid-sagittal sections through P14 control and RbpjiΔEC cortex. CD13+ pericytes and CD13+/EdU+ double positive pericytes were counted at P14 harvest. (C) Quantification of CD13+ pericytes per CD13+/EdU+ pericytes showed no significant change (P = 0.555). N = 4 controls and N = 4 mutants. (D,E) Mid-sagittal sections through P14 control and RbpjiΔEC cerebellum. CD13+ pericytes and CD13+/EdU+ double positive pericytes were counted at P14 harvest. (F) Quantification of CD13+ pericytes per CD13+/EdU+ pericytes showed no significant change (P = 0.364). N = 4 controls and N = 4 mutants. ns, not significant.

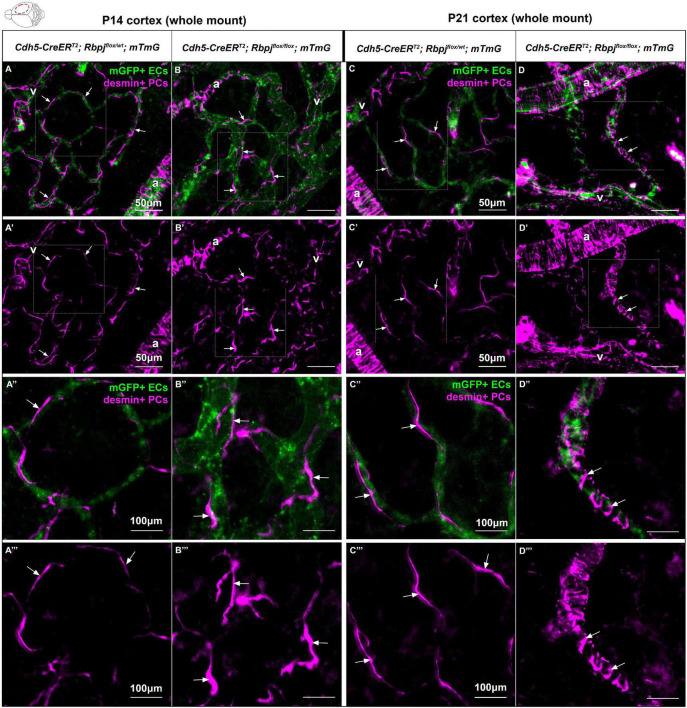

Brain pericytes extended processes to enwrap late-stage arteriovenous shunts, following endothelial deletion of Rbpj

To determine whether pericyte morphology was affected on RbpjiΔEC brain AV connections, we combined our whole mount cortical prep with anti-desmin immunostaining. Desmin expression spanned the cytosolic pericyte processes and offered a view of desmin+ pericyte ensheathment on mGFP+ brain vessels. In P14 control cortex, pericytes on AV connections (4–6 μm diameter capillaries) extended thin cytoplasmic processes to enwrap vessels (Figures 4A–A”’), while in RbpjiΔEC cortex, pericyte processes appeared thickened and ring-like in abnormal AV vessel segments (>12 μm diameter AV shunts) (Figures 4B–B”’). In P21 control cortex, pericytes were similar to P14 controls, with thin and elongated processes (Figures 4C–C”’). In P21 RbpjiΔEC cortex, thickened, ring-like pericytes began to resemble the concentric morphology characteristic of vascular smooth muscle cells (Figures 4D–D”’). These findings suggest that endothelial Rbpj is required to maintain healthy pericyte morphology on brain microvessels.

FIGURE 4.

Desmin-positive pericytes showed abnormal morphology on P14 and P21 brain microvessels, following endothelial deletion of Rbpj. Whole mount immunostaining against desmin highlighted pericyte processes (PCs) (magenta) on mGFP+ brain AV connections (ECs) (green). By P14 (A–B”’) and P21 (C–D”’), pericyte processes enwrapped brain capillaries in controls and AV shunts in RbpjiΔEC mutants (arrows). (B’,B”’,D’,D”’) Pericytes extended their cytosolic processes to maintain coverage of expanding endothelium. By P21, pericytes on AV shunts appeared to acquire a ring-like morphology to enwrap the expanded microvessel. A, artery; V, vein. P14, N = 9 controls and N = 9 mutants; P21, N = 3 controls and N = 3 mutants.

Endothelial Rbpj deficiency led to decreased Pdgfrβ expression in pericytes and decreased vessel coverage by Pdgfrβ+ pericytes

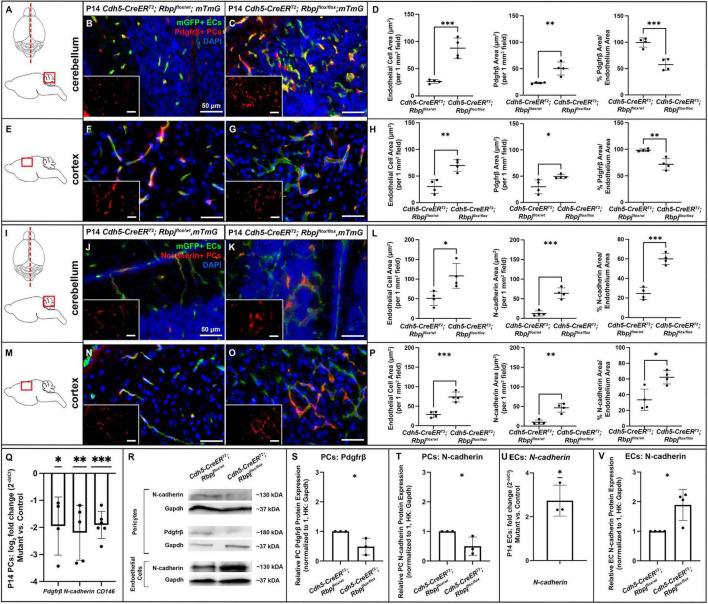

Based on previous reports of Notch dependent Pdgfrβ expression in pericytes, we next hypothesized that endothelial Rbpj deficiency from birth would lead to decreased Pdgfrβ expression in pericytes by P14. We first examined Pdgfrβ+ pericyte area to determine whether RbpjiΔEC pericyte expansion included predominately Pdgfrβ+ or Pdgfrβ- pericytes. We measured Pdgfrβ+ and mGFP+ areas in P14 cerebellum and cortex. As expected, and consistent with previous data, mGFP+ endothelial area was increased in both P14 cerebellum and cortex (cerebellum Figures 5A–C, left graph in D; cortex Figures 5E–G, left graph in H). In P14 cerebellum and cortex, we found slight but significantly increased Pdgfrβ+ area in mutants, as compared to controls (Figures 5A–H). By contrast to our CD13+ and desmin+ area data, the percentage of Pdgfrβ+ area/endothelial area was significantly decreased in P14 RbpjiΔEC cerebellum and cortex (right graphs in Figures 5D,H). These data suggest that while total pericyte area increased in RbpjiΔEC brains, a significant number of pericytes expressed Pdgfrβ abnormally. To determine whether endothelial deletion of Rbpj affected pericyte Pdgfrβ expression at the transcript and/or protein level, we isolated pericytes from P14 control and RbpjiΔEC brains for transcript and Western blot analyses. As compared to controls, RbpjiΔEC brain pericytes showed decreased expression of Pdgfrβ transcript (Figure 5Q) and protein (Figures 5R,S) by P14, indicating that endothelial Rbpj regulates expression of Pdgfrβ in pericytes in the early postnatal brain.

FIGURE 5.

By P14, endothelial Rbpj deficiency led to decreased expression of Pdgfrβ, N-cadherin, and CD146 by brain pericytes and increased expression of N-cadherin by brain endothelial cells. (A,I) Upper, schematic of brain mid-sagittal section cerebellum; lower, schematic of cerebellum brain region shown. (E,M) schematic of cortex brain region shown. (B,C,F,G) Pdgfrβ+ pericytes (PCs) (red), mGFP+ ECs (green), DAPI+ nuclei (blue). (B,C) mGFP+ endothelial area and Pdgfrβ+ pericyte area increased in P14 RbpjiΔEC cerebellum, as compared to control. Quantified in (D) endothelial area P = 0.0007; Pdgfrβ+ area P = 0.0048. Percentage of Pdgfrβ+ area/endothelial area was decreased in RbpjiΔEC cerebellum, as compared to controls (right graph in D; P = 0.0010). N = 4 controls and N = 4 mutants. (F,G) mGFP+ endothelial area and Pdgfrβ+ pericyte area increased in P14 RbpjiΔEC cortex, as compared to control. Quantified in (H) endothelial area P = 0.0033; Pdgfrβ+ area P = 0.0317. Percentage of Pdgfrβ+ area/endothelial area was decreased in RbpjiΔEC cerebellum, as compared to controls (right graph in H; P = 0.0032). N = 4 controls and N = 4 mutants. (J,K,N,O) N-cadherin+ cells (red), mGFP+ ECs (green), DAPI+ nuclei (blue). (J,K) mGFP+ endothelial area and N-cadherin+ area increased in P14 RbpjiΔEC cerebellum, as compared to control. Quantified in (L) endothelial area P = 0.0204; N-cadherin+ area P = 0.0005. Percentage of N-cadherin+ area/endothelial area decreased in RbpjiΔEC cerebellum, as compared to controls (right graph in L; P = 0.0002). N = 4 controls and N = 4 mutants. (N,O) mGFP+ endothelial area and N-cadherin+ area increased in P14 RbpjiΔEC cortex, as compared to control. Quantified in (P) endothelial area P = 0.0009; N-cadherin+ area P = 0.0011. Percentage of N-cadherin+ area/endothelial area decreased in RbpjiΔEC cortex, as compared to controls (right graph in P; P = 0.0119). N = 4 controls and N = 4 mutants. (Q) RT-qPCR analysis of transcript expression from isolated P14 brain pericytes showed decreased expression of Pdgfrβ (p = 0.0360), N-cadherin (P = 0.0084) and CD146 (P = 0.0002) in RbpjiΔEC mutants as compared to controls. (R) Western blot analysis of protein expression from isolated brain pericytes and ECs showed decreased expression of Pdgfrβ (P = 0.0349) and N-cadherin (P = 0.0487) in RbpjiΔEC pericytes [quantified in (S,T), respectively; N = 3 controls and N = 3 mutants] and increased expression of N-cadherin (P = 0.0143) in RbpjiΔEC ECs [quantified in (V); N = 4 controls and N = 4 mutants]. (U) RT-qPCR analysis of transcript expression from isolated P14 brain ECs showed increased expression of N-cadherin (P = 0.0216) in RbpjiΔEC ECs. N = 3 controls and N = 3 mutants. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Endothelial Rbpj deficiency led to decreased N-cadherin and CD146 expression in pericytes, but increased N-cadherin expression in endothelial cells

We next tested whether endothelial deletion of Rbpj affected expression of other factors involved in EC-pericyte communication—specifically, molecules predicted to be regulated by (N-cadherin) or molecules predicted to be regulators of (CD146) Pdgf-B/Pdgfrβ signaling. We immunostained against N-cadherin, a molecule expressed by ECs and pericytes and involved in direct cell-cell association. We measured N-cadherin+ and mGFP+ areas in P14 cerebellum and cortex. As expected, and consistent with previous data, mGFP+ endothelial area was increased in both P14 cerebellum and cortex (cerebellum Figures 5I–K, left graph in L; cortex Figures 5M–O, left graph in P). Total N-cadherin+ area was significantly increased in both cerebellum (Figure 5L, middle graph) and cortex (Figure 5P, middle graph). The percentage of N-cadherin+ area/endothelial area was significantly increased in P14 RbpjiΔEC cerebellum and cortex (right graphs in Figures 5L,P); however, it must be noted that N-cadherin expression was not exclusive to pericytes, so the percentage did not represent pericyte/endothelial coverage exclusively. To determine whether endothelial deletion of Rbpj affected EC and/or pericyte expression of N-cadherin at the transcript and/or protein level, we isolated ECs and pericytes from P14 control and RbpjiΔEC brains. As compared to controls, P14 RbpjiΔEC brain pericytes showed decreased expression of N-cadherin transcript (Figure 5Q) and protein (Figures 5R,T). By contrast, P14 RbpjiΔEC brain ECs showed increased expression of N-cadherin transcript (Figure 5U) and protein (Figures 5R,V), indicating that endothelial Rbpj regulates expression of N-cadherin differentially in pericytes and ECs in the early postnatal brain.

CD146 is expressed dynamically by ECs and pericytes in the developing brain, where it has been shown to promote pericyte association with ECs, in part by regulating Pdgf-B/Pdgfrβ signaling. In brain microvessels, CD146 is expressed primarily by pericytes, where it has been shown to act as a co-receptor for Pdgfrβ (Chen et al., 2017). To test whether expression of CD146 was affected by endothelial Rbpj deficiency, we analyzed CD146 expression in pericytes isolated from P14 control and RbpjiΔEC brains. We found decreased expression of CD146 by RbpjiΔEC brain pericytes, as compared to controls (Figure 5Q), suggesting that endothelial Rbpj regulates expression of CD146. Together, our data suggest that Rbpj is required in early postnatal endothelium, to regulate expression of molecules involved in EC-pericyte communication and association.

Discussion

Endothelial Rbpj regulates pericyte bed area and maintains pericyte morphology in the early postnatal central nervous system

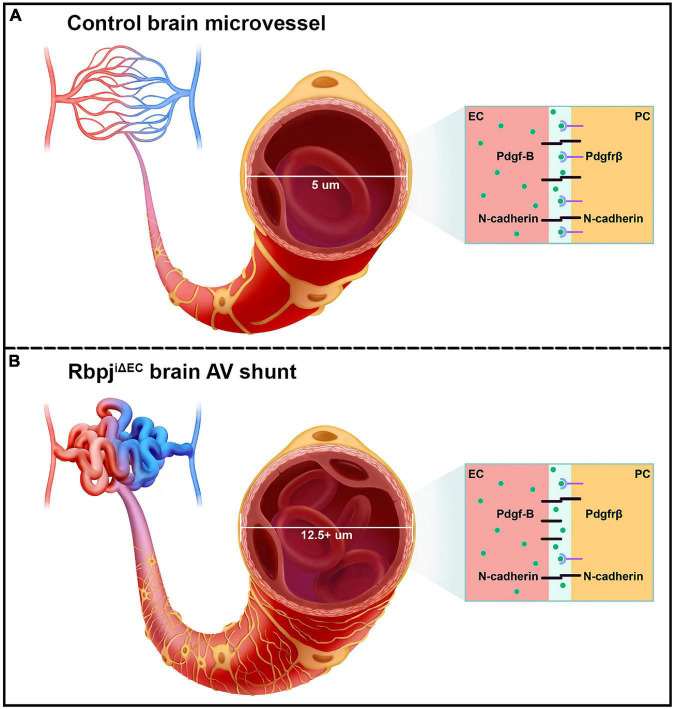

Our data indicate that endothelial Rbpj is required to prevent pathological pericyte expansion in the early postnatal brain vasculature (Figures 6A,B). Consistent with our data, previous studies have shown increased pericyte area or coverage in abnormal CNS or non-CNS vascular beds. Loss of Foxf2 from neuronal progenitor cells leads to a twofold increase in pericyte coverage of forebrain cortical microvessels in late-gestation mouse embryos (Reyahi et al., 2015), suggesting genetic regulation to prevent pericyte expansion in the developing CNS. Depletion of astrocytes in perinatal mouse brain leads to increased cortical vessel and luminal diameter, with increased desmin+ pericyte expression, suggesting that newly born astrocytes influence the early postnatal brain microvessels and pericytes (Ma et al., 2012). Outside of the CNS vasculature, increased pericyte coverage has been reported in bone marrow samples from myelofibrosis patients (Zetterberg et al., 2007), in PDGF-BB induced non-small cell lung xenograft tumors (Song et al., 2009), in an in vitro pulmonary hypertension model (Khoury and Langleben, 1996), and in mice and guinea pig cochlear capillaries following auditory trauma (Shi, 2009). Our pericyte expansion data are consistent with these previous findings, which demonstrate increased pericyte area and/or coverage, in the context of microvessel abnormalities.

FIGURE 6.

Schematic of the pathological consequences to brain pericytes, following endothelial deletion of Rbpj. (A) Top cartoon illustrates healthy brain microvessels. In controls, ∼5 μm capillaries are enwrapped by pericyte processes (gold). Capillary ECs and pericytes are tightly apposed and share a basement membrane. Box represents an adjacent EC and pericyte (PC), which remain tightly associated via Pdgf-B/Pdgfrβ signaling and downstream N-cadherin expression. (B) Bottom cartoon illustrates RbpjiΔEC AV connections. Vessel diameter is enlarged (12.5+ μm), and pericytes pathologically expand to keep pace with the increased endothelium. Box shows effects on EC-pericyte communication, following endothelial deletion of Rbpj: pericytes down-regulate Pdgfrβ and N-cadherin, while ECs up-regulate N-cadherin.

In the early postnatal brain, endothelial Rbpj likely plays a role in maintaining pericyte morphology and regulating the number of pericytes per vessel length. Our EdU incorporation data indicate that pericyte proliferation was not increased in RbpjiΔEC brain vasculature, yet total pericyte area and pericyte number per vessel length were increased. Based on our whole-mount observations of desmin+ pericyte processes enwrapping abnormal AV connections in RbpjiΔEC brain, it is likely that pericytes abnormally extend processes, in response to endothelial Rbpj deficiency and pathological endothelial expansion. As brain AVM pathology progressed, pericytes on RbpjiΔEC AV shunts began to resemble the band-like morphology characteristic of smooth muscle cells. However, previous data showed that α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA, a smooth muscle marker) was not expressed by brain AV shunts in P14 RbpjiΔEC mice, while αSMA was expressed by arterioles (Nielsen et al., 2014). Since the band-like desmin+ pericytes spanned the entire length of the AV shunt in Figure 4, it is not likely that these are smooth muscle cells, but rather pericytes that have altered band-like morphology.

What then accounts for the increased number of pericytes on AV shunts, as compared to control capillaries? As brain pericytes are capable of microvascular migration (Dore-Duffy et al., 2000) and of cellular trans-differentiation (Dore-Duffy et al., 2006; Bonkowski et al., 2011) within the CNS, it is possible that affected pericytes migrate from healthy vessel segments to abnormal AV connections and/or initiate differentiation into another neural cell type, yet retain pericyte marker expression and position adjacent to blood vessels. Because mesenchymal cells, bone marrow cells, and ECs are capable of trans-differentiating into pericytes—either in vitro or under pathological conditions (DeRuiter et al., 1997; Rajantie et al., 2004; Kokovay et al., 2006)—it is possible that these origins contribute to increased pericyte number per vessel length in RbpjiΔEC brains. Another possibility is that the nature of brain AV shunt formation in RbpjiΔEC mice influences pericyte number per vessel length. For example, in healthy early postnatal brain vasculature, vascular remodeling is required to form a functionally mature vascular bed (Wang et al., 1992; Wälchli et al., 2015). At P0–P5, mouse neurovasculature resembles a primitive vascular plexus (similar to the yolk sac vasculature) in which arteries and veins can be identified, but in which AV connections have not yet refined to capillary-diameter vessels (Wang et al., 1992; Nielsen et al., 2014). By P14, capillary beds can be seen joining arterial to venous vessels (Nielsen et al., 2014). While pericyte dynamics during this postnatal morphogenesis have not been studied, it is possible that impaired vascular remodeling affects pericyte number in RbpjiΔEC neonatal brain tissue. For example, AV connection remodeling may involve EC rearrangement by which vessels narrow and “stretch out,” and this may affect pericyte number per given vessel length. Thus, endothelial Rbpj may be required in the early postnatal brain to maintain healthy pericyte number and morphology.

Endothelial Rbpj regulates central nervous system pericyte bed area in a regionally and temporally regulated manner

Our findings show that abnormal pericyte expansion began in cerebellum and retina by P10 and in frontal cortex by P14, and pericyte area expansion continued until P21 in both brain regions; thus, endothelial Rbpj influences pericytes differentially as postnatal brain morphogenesis proceeds. Pericyte expansion paralleled endothelial expansion at all timepoints, in both cerebellum and cortex, indicating that pericyte area keeps pace with pathological endothelial area, following endothelial deletion of Rbpj. Cerebellum pericytes were preferentially affected in mutants, pericyte expansion began earliest (P10) and was most severe by P14 in the cerebellum (Table 1). These findings are consistent with significant abnormalities to cerebellum tissue itself, following endothelial deletion of Rbpj (Chapman et al., 2022). During the early postnatal period, endothelial Rbpj is critical for cerebellar vascular development and proper tissue lobulation and growth (Chapman et al., 2022). Our findings show that endothelial Rbpj is also critical for pericyte maintenance during this period of cerebellar morphogenesis and outward growth. By contrast, pericyte area was not affected in the brain stem at any timepoint analyzed, suggesting that endothelial Rbpj regulates pericyte expansion in a regionally restricted manner. Consistent with this, (1) endothelial area in brain stem was not affected, following endothelial deletion of Rbpj in postnatal brain (Nielsen et al., 2014), and (2) brain stem AVM in human patients are rare, comprising 2–6% of all brain AVM (Chen et al., 2021) and often presenting superficially in the meninges rather than deep within brain parenchyma (Han et al., 2015). It is not known whether or how the brain stem is physiologically refractory to and/or protected from brain AVM. Together, our data demonstrate spatial and temporal regulation of CNS pericyte area by endothelial Rbpj.

Endothelial Rbpj regulates expression of factors that promote brain pericyte recruitment and association with endothelial cells

Decreased expression of Pdgfrβ, N-cadherin, and CD146 by RbpjiΔEC brain pericytes suggests that intercellular communication between ECs and pericytes was affected. For example, Pdgf-B/Pdgfrβ signaling between ECs and pericytes is critical for recruiting pericytes to microvessels and maintaining the cells’ close juxtaposition (Armulik et al., 2010; Daneman et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2017; Nikolakopoulou et al., 2017). Despite the expanded pericyte area in RbpjiΔEC neurovasculature, Pdgf-B/Pdgfrβ signaling was likely affected and pericyte association with microvessels may have been impaired. Consistent with previous studies (Jin et al., 2008; Li et al., 2011; Yao et al., 2011), our data suggest a role for endothelial Rbpj/Notch signaling to regulate pericyte expression of Pdgfrβ. Interestingly, our results showed that while pericytes decreased N-cadherin expression, following endothelial deletion of Rbpj, ECs increased N-cadherin expression. This differential regulation of N-cadherin by endothelial Rbpj may be an attempt by ECs to compensate for decreased Pdgf-B/Pdgfrβ signaling and N-cadherin expression and thereby restore vessel stability, in the context of RbpjiΔEC microvessel and pericyte abnormalities. Collectively, our data suggest that endothelial Rbpj regulates Pdgf-B/Pdgfrβ signaling, including expression of genes encoding the Pdgfrβ co-receptor CD146 and downstream target N-cadherin (Figures 6A,B).

As proper pericyte coverage of microvessels is involved in regulating vascular permeability, it is possible that the pathologically expanded pericyte bed in RbpjiΔEC brain may affect pericyte function and vessel stability. However, given the abnormalities to ECs, following endothelial deletion of Rbpj, it would be difficult to tease apart whether abnormal function of pericytes and/or ECs might contribute to altered vessel permeability. By P14, RbpjiΔEC brains show signs of intracerebral hemorrhage (Nielsen et al., 2014); however, the cellular mechanism by which blood leaks from RbpjiΔEC vessels remains unknown. One hypothesis raised by our data is that brain pericytes expand in concert with RbpjiΔEC vessels, as an attempt to stabilize mutant microvessels.

Recent evidence suggests there is a variety of pericyte subtypes that differ in morphology, molecular signature, and vascular function (Hartmann et al., 2015; Sweeney et al., 2016; Geranmayeh et al., 2019; Lendahl et al., 2019; Uemura et al., 2020; Bennett and Kim, 2021; Nadeem et al., 2022); therefore, the different pericyte populations may be differentially affected by Rbpj mediated brain AVM. We observed differences in pericyte area measurements, based on the which pericyte marker was used for analyses. While this alone underscores the importance of using multiple pericyte markers, this may also provide insight regarding how—and perhaps which—pericytes were pathologically expanded. CD13 is a metalloprotease and considered a selective surface marker for pericytes (Crouch and Doetsch, 2018), while desmin is present in intermediate filaments commonly found in pericyte processes (Armulik et al., 2011). As such, thin desmin+ processes may have been less detectable in mid-sagittal area measurements but gave insight about morphological changes to abnormal pericytes in RbpjiΔEC brain.

Pericyte reduction or loss from brain microvessels is not associated with Rbpj mediated brain arteriovenous malformation

To our knowledge, this report is the first to demonstrate pathological pericyte expansion in a mouse model of brain AVM. Our data contrast findings from other genetic models of CNS AVMs and from human brain AVM tissue and thus emphasize the heterogeneity among AVM pathologies and mechanisms. For example, reduced pericyte number and coverage of endothelium was reported in sporadic brain AVM samples from human patients (Winkler et al., 2018); however, these correlative studies could not reveal whether pericyte reduction was a cause or consequence of human brain AVM. Using mouse models of TGFβ related brain AVM, studies have similarly shown reduced pericyte coverage of brain microvessels (Chen et al., 2013; Tual-Chalot et al., 2014). In a genetic model of retina AVM, endothelial Smad4 deficiency led to decreased pericytes associated with retinal vessels (Crist et al., 2018). Two recent studies genetically deleted Rbpj from pericytes, in the early postnatal period, and found CNS AVM with pericyte deficiency (Diéguez-Hurtado et al., 2019; Nadeem et al., 2020). Further, Nadeem et al. (2020) showed that pericyte deficiency preceded vessel enlargement, suggesting that intact pericytes prevent AV shunting in retina vasculature. Differences in pericyte coverage among AVM models may reflect different mechanisms in AVM pathogenesis. For example, some AVMs are triggered by increased EC proliferation, serving to populate the increasing-diameter vessel growth. Such angiogenic AVMs are associated with reduced pericyte coverage, possibly as a mechanism to accommodate proliferative ECs and growth. By contrast, some AVMs, including RbpjiΔEC mediated brain AVMs, develop without increased EC proliferation (Murphy et al., 2014; Nielsen et al., 2014)—perhaps non-angiogenic ECs on microvessels elicit different pericyte responses during AVM pathogenesis. Despite the contrasting data for pericytes and CNS AVMs, our findings show that pericyte deficiency is not required for brain AVM formation. Thus, our study underscores the importance of probing mechanisms of genetically distinct brain AVM and of developing specific and appropriate therapies.

A question remains regarding the functional implications of pericyte abnormalities during brain AVM. In models of pericyte reduction during brain AVM, one working hypothesis is that the loss of pericytes loosens contractile constraints on microvessels and permits vessel dilation (Nadeem et al., 2020). Following even a slight increase in vessel diameter, increased blood flow is directed toward that path of least resistance and triggers continued vessel dilation, resulting in AV shunting. Loss of pericytes in brain AVM has also been suggested to disrupt vessel stability, which may be related to intracranial hemorrhages associated with brain AVM tissue (Winkler et al., 2018). Data from our Rbpj mediated brain AVM model showed that pericyte expansion was accompanied by abnormalities to pericyte morphology and disruptions to EC-pericyte communication. Thus, these abnormal pericytes may also contribute to microvascular instability. Because endothelial Rbpj deletion leads to endothelial, pericyte, cerebellar, and motor behavioral abnormalities (Nielsen et al., 2014; Chapman et al., 2022), a future challenge will be to tease apart which brain AVM pathologies are a consequence of endothelial vs. pericyte vs. tissue morphogenetic impairments, or of some combination thereof.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

This animal study was reviewed and approved by the Ohio University IACUC, Animal Protocol # 16-H-024.

Author contributions

SS, SN, SK, and CN conceptualized and designed the experiments. SS, SN, SK, SA, and CN performed the experiments and analyzed the data. CN wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We thank Emi Olin (www.abieto.com) for artistic rendering in Figure 6. We also thank Ohio University IACUC and Laboratory for Animal Research for Animal Care; Ohio University Histopathology Core for access to cryostat; Ohio University Neuroscience Program for training and access to confocal microscope.

Funding

This research was supported by the President’s Undergraduate Research Funding and John J. Kopchick/Molecular and Cellular Biology/Translational Biomedical Sciences Undergraduate Research Support Funding to SS. By Ohio University Honors Tutorial College Research Apprenticeships and Summer Neuroscience Undergraduate Research Fellowships to SS and SK; and by start-up funding (Ohio University College of Arts and Sciences) and NIH R15 NS111376 to CN.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2022.974033/full#supplementary-material

References

- Armulik A., Genové G., Betsholtz C. (2011). Pericytes: developmental, physiological, and pathological perspectives, problems, and promises. Dev. Cell 21 193–215. 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armulik A., Genové G., Mäe M., Nisancioglu M. H., Wallgard E., Niaudet C., et al. (2010). Pericytes regulate the blood-brain barrier. Nature 468 557–561. 10.1038/nature09522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battegay E. J., Rupp J., Iruela-Arispe L., Sage E. H., Pech M. (1994). PDGF-BB modulates endothelial proliferation and angiogenesis in vitro via PDGF B-Receptors. J. Cell Biol. 125 917–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell A. H., Miller S. L., Castillo-Melendez M., Malhotra A. (2020). The neurovascular unit: effects of brain insults during the perinatal period. Front. Neurosci. 13:1452. 10.3389/fnins.2019.01452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell R. D., Winkler E. A., Sagare A. P., Singh I., LaRue B., Deane R., et al. (2010). Pericytes control key neurovascular functions and neuronal phenotype in the adult brain and during brain aging. Neuron 68 409–427. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett H. C., Kim Y. (2021). Pericytes across the lifetime in the central nervous system. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 15:627291. 10.3389/fncel.2021.627291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birbrair A. (2019). “Pericyte biology in disease,” in Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, ed. Birbrair A. (Cham: Springer International Publishing; ), 10.1007/978-3-030-16908-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonkowski D., Katyshev V., Balabanov R. D., Borisov A., Dore-Duffy P. (2011). The CNS microvascular pericyte: pericyte-astrocyte crosstalk in the regulation of tissue survival. Fluids Barriers CNS 8:8. 10.1186/2045-8118-8-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdeau A., Dumont D. J., Letarte M. (1999). A murine model of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. J. Clin. Invest. 104 1343–1351. 10.1172/JCI8088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai W., Liu H., Zhao J., Chen L. Y., Chen J., Lu Z., et al. (2017). Pericytes in brain injury and repair after ischemic stroke. Transl. Stroke Res. 8 107–121. 10.1007/s12975-016-0504-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan-Ling T., Page M. P., Gardiner T., Baxter L., Rosinova E., Hughes S. (2004). Desmin ensheathment ratio as an indicator of vessel stability. Am. J. Pathol. 165 1301–1313. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63389-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman A. D., Selhorst S., LaComb J., LeDantec-Boswell A., Wohl T. R., Adhicary S., et al. (2022). Endothelial Rbpj is required for cerebellar morphogenesis and motor control in the early postnatal mouse brain. Cerebellum Online ahead of print. 10.1007/s12311-022-01429-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Luo Y., Hui H., Cai T., Huang H., Yang F., et al. (2017). CD146 coordinates brain endothelial cell-pericyte communication for blood-brain barrier development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 114 E7622–E7631. 10.1073/pnas.1710848114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Guo Y., Walker E. J., Shen F., Jun K., Oh S. P., et al. (2013). Reduced mural cell coverage and impaired vessel integrity after angiogenic stimulation in the Alk1 -deficient brain. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 33 305–310. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Li R., Ma L., Meng X., Yan D., Wang H., et al. (2021). Long-term outcomes of brainstem arteriovenous malformations after different management modalities: a single-centre experience. Stroke Vasc. Neurol. 6 65–73. 10.1136/svn-2020-000407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crist A. M., Lee A. R., Patel N. R., Westhoff D. E., Meadows S. M. (2018). Vascular deficiency of Smad4 causes arteriovenous malformations: a mouse model of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Angiogenesis 21 363–380. 10.1007/s10456-018-9602-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouch E. E., Doetsch F. (2018). FACS isolation of endothelial cells and pericytes from mouse brain microregions. Nat. Protoc. 13 738–751. 10.1038/nprot.2017.158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo H., Nielsen C. M., Simonetto D. A., Ferrell L., Shah V. H., Wang R. A. (2016). Endothelial notch signaling is essential to prevent hepatic vascular malformations in mice: notch signaling prevents hepatic vascular malformations in mice. Hepatology 64 1302–1316. 10.1002/hep.28713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daneman R., Zhou L., Kebede A. A., Barres B. A. (2010). Pericytes are required for blood-brain barrier integrity during embryogenesis. Nature 468 562–566. 10.1038/nature09513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRuiter M. C., Poelmann R. E., VanMunsteren J. C., Mironov V., Markwald R. R., Gittenberger-de Groot A. C. (1997). Embryonic endothelial cells transdifferentiate into mesenchymal cells expressing smooth muscle actins in vivo and in vitro. Circulation Res. 80 444–451. 10.1161/01.RES.80.4.444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diéguez-Hurtado R., Kato K., Giaimo B. D., Nieminen-Kelhä M., Arf H., Ferrante F., et al. (2019). Loss of the transcription factor RBPJ induces disease-promoting properties in brain pericytes. Nat. Commun. 10:2817. 10.1038/s41467-019-10643-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore-Duffy P., Katychev A., Wang X., Van Buren E. (2006). CNS microvascular pericytes exhibit multipotential stem cell activity. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 26 613–624. 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore-Duffy P., Owen C., Balabanov R., Murphy S., Beaumont T., Rafols J. A. (2000). Pericyte migration from the vascular wall in response to traumatic brain injury. Microvasc. Res. 60 55–69. 10.1006/mvre.2000.2244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do Prado L. B., Han C., Oh S. P., Su H. (2019). Recent advances in basic research for brain arteriovenous malformation. IJMS 20:5324. 10.3390/ijms20215324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Chacón M., García-González I., Mühleder S., Benedito R. (2021). Role of notch in endothelial biology. Angiogenesis 24 237–250. 10.1007/s10456-021-09793-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish J. E., Flores Suarez C. P., Boudreau E., Herman A. M., Gutierrez M. C., Gustafson D., et al. (2020). Somatic gain of KRAS function in the endothelium is sufficient to cause vascular malformations that require MEK but not PI3K signaling. Circ. Res. 127 727–743. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.316500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geranmayeh M. H., Rahbarghazi R., Farhoudi M. (2019). Targeting pericytes for neurovascular regeneration. Cell Commun. Signal. 17:26. 10.1186/s12964-019-0340-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt H., Wolburg H., Redies C. (2000). N-cadherin mediates pericytic-endothelial interaction during brain angiogenesis in the chicken. Dev. Dyn. 218 472–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales A. L., Klug N. R., Moshkforoush A., Lee J. C., Lee F. K., Shui B., et al. (2020). Contractile pericytes determine the direction of blood flow at capillary junctions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 117 27022–27033. 10.1073/pnas.1922755117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X., Liu X.-Y., Fagan A., Gonzalez-Toledo M. E., Zhao L.-R. (2012). Ultrastructural changes in cerebral capillary pericytes in aged notch3 mutant transgenic mice. Ultrastructural Pathol. 36 48–55. 10.3109/01913123.2011.620220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S. J., Englot D. J., Kim H., Lawton M. T. (2015). Brainstem arteriovenous malformations: anatomical subtypes, assessment of “occlusion in situ” technique, and microsurgical results. JNS 122 107–117. 10.3171/2014.8.JNS1483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann D. A., Underly R. G., Grant R. I., Watson A. N., Lindner V., Shih A. Y. (2015). Pericyte structure and distribution in the cerebral cortex revealed by high-resolution imaging of transgenic mice. Neurophoton 2:041402. 10.1117/1.NPh.2.4.041402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellström M., Phng L.-K., Hofmann J. J., Wallgard E., Coultas L., Lindblom P., et al. (2007). Dll4 signalling through Notch1 regulates formation of tip cells during angiogenesis. Nature 445 776–780. 10.1038/nature05571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirunpattarasilp C., Attwell D., Freitas F. (2019). The role of pericytes in brain disorders: from the periphery to the brain. J. Neurochem. 150 648–665. 10.1111/jnc.14725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes S., Gardiner T., Baxter L., Chan-Ling T. (2007). Changes in pericytes and smooth muscle cells in the kitten model of retinopathy of prematurity: implications for plus disease. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 48:1368. 10.1167/iovs.06-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin S., Hansson E. M., Tikka S., Lanner F., Sahlgren C., Farnebo F., et al. (2008). Notch signaling regulates platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β expression in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res. 102 1483–1491. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.167965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoury J., Langleben D. (1996). Platelet-activating factor stimulates lung pericyte growth in vitro. Am. J. Physiology-Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 270 L298–L304. 10.1152/ajplung.1996.270.2.L298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokovay E., Li L., Cunningham L. A. (2006). Angiogenic recruitment of pericytes from bone marrow after stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 26 545–555. 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs L. T., Shutter J. R., Tanigaki K., Honjo T., Stark K. L., Gridley T. (2004). Haploinsufficient lethality and formation of arteriovenous malformations in Notch pathway mutants. Genes Dev. 18 2469–2473. 10.1101/gad.1239204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs L. T., Xue Y., Norton C. R., Shutter J. R., Maguire M., Sundberg J. P., et al. (2000). Notch signaling is essential for vascular morphogenesis in mice. Genes Dev. 14 1343–1352. 10.1101/gad.14.11.1343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebrin F., Srun S., Raymond K., Martin S., van den Brink S., Freitas C., et al. (2010). Thalidomide stimulates vessel maturation and reduces epistaxis in individuals with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Nat. Med. 16 420–428. 10.1038/nm.2131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lendahl U., Nilsson P., Betsholtz C. (2019). Emerging links between cerebrovascular and neurodegenerative diseases—a special role for pericytes. EMBO Rep. 20:e48070. 10.15252/embr.201948070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F., Lan Y., Wang, Youliang, Wang J., Yang G., et al. (2011). Endothelial Smad4 maintains cerebrovascular integrity by activating N-Cadherin through cooperation with notch. Dev. Cell 20 291–302. 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Zhang W., Kennard S., Caldwell R. B., Lilly B. (2010). Notch3 is critical for proper angiogenesis and mural cell investment. Circ. Res. 107 860–870. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.218271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S., Kwon H. J., Huang Z. (2012). A functional requirement for astroglia in promoting blood vessel development in the early postnatal brain. PLoS One 7:e48001. 10.1371/journal.pone.0048001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy P. A., Kim T. N., Huang L., Nielsen C. M., Lawton M. T., Adams R. H., et al. (2014). Constitutively active Notch4 receptor elicits brain arteriovenous malformations through enlargement of capillary-like vessels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 111 18007–18012. 10.1073/pnas.1415316111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzumdar M. D., Tasic B., Miyamichi K., Li L., Luo L. (2007). A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis 45 593–605. 10.1002/dvg.20335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem T., Bogue W., Bigit B., Cuervo H. (2020). Deficiency of Notch signaling in pericytes results in arteriovenous malformations. JCI Insight 5:e125940. 10.1172/jci.insight.125940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem T., Bommareddy A., Bolarinwa L., Cuervo H. (2022). Pericyte dynamics in the mouse germinal matrix angiogenesis. FASEB J. 36:e22339. 10.1096/fj.202200120R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen C. M., Cuervo H., Ding V. W., Kong Y., Huang E. J., Wang R. A. (2014). Deletion of Rbpj from postnatal endothelium leads to abnormal arteriovenous shunting in mice. Development 141 3782–3792. 10.1242/dev.108951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen C. M., Dymecki S. M. (2010). Sonic hedgehog is required for vascular outgrowth in the hindbrain choroid plexus. Developmental Biology 340, 430–437. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.01.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaev S. I., Vetiska S., Bonilla X., Boudreau E., Jauhiainen S., Rezai Jahromi B., et al. (2018). Somatic activating KRAS mutations in arteriovenous malformations of the brain. N. Engl. J. Med. 378 250–261. 10.1056/NEJMoa1709449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolakopoulou A. M., Zhao Z., Montagne A., Zlokovic B. V. (2017). Regional early and progressive loss of brain pericytes but not vascular smooth muscle cells in adult mice with disrupted platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β signaling. PLoS One 12:e0176225. 10.1371/journal.pone.0176225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. O., Wankhede M., Lee Y. J., Choi E.-J., Fliess N., Choe S.-W., et al. (2009). Real-time imaging of de novo arteriovenous malformation in a mouse model of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. J. Clin. Invest. 119 3487–3496. 10.1172/JCI39482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polito A., Reynolds R. (2005). NG2-expressing cells as oligodendrocyte progenitors in the normal and demyelinated adult central nervous system. J. Anatomy 207 707–716. 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00454.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajantie I., Ilmonen M., Alminaite A., Ozerdem U., Alitalo K., Salven P. (2004). Adult bone marrow-derived cells recruited during angiogenesis comprise precursors for periendothelial vascular mural cells. Blood 104 2084–2086. 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raper D. M. S., Winkler E. A., Rutledge C. W., Cooke D. L., Abla A. A. (2020). An update on medications for brain arteriovenous malformations. Neurosurgery 87 871–878. 10.1093/neuros/nyaa192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyahi A., Nik A. M., Ghiami M., Gritli-Linde A., Pontén F., Johansson B. R., et al. (2015). Foxf2 is required for brain pericyte differentiation and development and maintenance of the blood-brain barrier. Dev. Cell 34 19–32. 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satomi J., Mount R. J., Toporsian M., Paterson A. D., Wallace M. C., Harrison R. V., et al. (2003). Cerebral vascular abnormalities in a murine model of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Stroke 34 783–789. 10.1161/01.STR.0000056170.47815.37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen T. D., Livak K. J. (2008). Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat. Protoc. 3 1101–1108. 10.1038/nprot.2008.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X. (2009). Cochlear pericyte responses to acoustic trauma and the involvement of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and vascular endothelial growth factor. Am. J. Pathol. 174 1692–1704. 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song N., Huang Y., Shi H., Yuan S., Ding Y., Song X., et al. (2009). Overexpression of platelet-derived growth factor-bb increases tumor pericyte content via stromal-derived factor-1α/CXCR4 axis. Cancer Res. 69 6057–6064. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sörensen I., Adams R. H., Gossler A. (2009). DLL1-mediated Notch activation regulates endothelial identity in mouse fetal arteries. Blood 113 5680–5688. 10.1182/blood-2008-08-174508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney M. D., Ayyadurai S., Zlokovic B. V. (2016). Pericytes of the neurovascular unit: key functions and signaling pathways. Nat. Neurosci. 19 771–783. 10.1038/nn.4288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagami M., Nara Y., Kubota A., Fujino H., Yamori Y. (1990). Ultrastructural changes in cerebral pericytes and astrocytes of stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Stroke 21 1064–1071. 10.1161/01.STR.21.7.1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanigaki K., Han H., Yamamoto N., Tashiro K., Ikegawa M., Kuroda K., et al. (2002). Notch-RBP-J signaling is involved in cell fate determination of marginal zone B cells. Nat. Immunol. 3 443–450. 10.1038/ni793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thalgott J., Dos-Santos-Luis D., Lebrin F. (2015). Pericytes as targets in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Front. Genet. 6:37. 10.3389/fgene.2015.00037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tual-Chalot S., Allinson K. R., Fruttiger M., Arthur H. M. (2013). Whole mount immunofluorescent staining of the neonatal mouse retina to investigate angiogenesis in vivo. JoVE 77:50546. 10.3791/50546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tual-Chalot S., Mahmoud M., Allinson K. R., Redgrave R. E., Zhai Z., Oh S. P., et al. (2014). Endothelial depletion of acvrl1 in mice leads to arteriovenous malformations associated with reduced endoglin expression. PLoS One 9:e98646. 10.1371/journal.pone.0098646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura M. T., Maki T., Ihara M., Lee V. M. Y., Trojanowski J. Q. (2020). Brain microvascular pericytes in vascular cognitive impairment and dementia. Front. Aging Neurosci. 12:80. 10.3389/fnagi.2020.00080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wälchli T., Mateos J. M., Weinman O., Babic D., Regli L., Hoerstrup S. P., et al. (2015). Quantitative assessment of angiogenesis, perfused blood vessels and endothelial tip cells in the postnatal mouse brain. Nat. Protoc. 10 53–74. 10.1038/nprot.2015.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D.-B., Blocher N. C., Spence M. E., Rovainen C. M., Woolsey T. A. (1992). Development and remodeling of cerebral blood vessels and their flow in postnatal mice observed with in vivo videomicroscopy. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 12 935–946. 10.1038/jcbfm.1992.130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler E. A., Bell R. D., Zlokovic B. V. (2010). Pericyte-specific expression of PDGF beta receptor in mouse models with normal and deficient PDGF beta receptor signaling. Mol. Neurodegeneration 5:32. 10.1186/1750-1326-5-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler E. A., Birk H., Burkhardt J.-K., Chen X., Yue J. K., Guo D., et al. (2018). Reductions in brain pericytes are associated with arteriovenous malformation vascular instability. J. Neurosurg. 129 1464–1474. 10.3171/2017.6.JNS17860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H., Duan M., Hu G., Buch S. (2011). Platelet-Derived growth factor b chain is a novel target gene of cocaine-mediated notch1 signaling: implications for hiv-associated neurological disorders. J. Neurosci. 31 12449–12454. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2330-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]