Abstract

Background

A high number of jaundice cases were reported from two colocated training centers in North India. This outbreak was investigated to describe the epidemiology, identify risk factors, and recommend preventive and control measures.

Methods

Initial line list was prepared, and case definition was defined as “the presence of icterus or passage of yellow-colored urine with fever/anorexia/vomiting/abdominal pain in a resident of Military Station A between 03/04/2016 to 06/06/2016”. Case search was conducted through surveillance. An unmatched 1:1 case–control study was conducted to evaluate the associated risk factors. All cases were tested for hepatitis markers. Environmental investigation of food and water sources was conducted to identify the source of infection.

Results

Of 172 cases, all were males from two co-located military training centers (attack rate, 4.7%). Clinical features included icterus (100%), yellowish discoloration of urine (98.9%), anorexia (97.22%), fever (80%), nausea/vomiting (56%), and abdominal pain (52.77%). Only one case (0.6%) had complication of fulminant hepatitis, and there were no deaths (CFR = 0%). Consumption of juice with ice from juice shops was significantly associated with illness (Odds Ratio-14.3 [95%CI 7.4–27.6]). Of 172 cases, 167 (97.1%) tested anti-HEV-IgM positive. Juice shops in training centers were using ice made from contaminated water with positive coliform test. All other water samples tested satisfactory. No cross-contamination of water pipelines with sewage was observed.

Conclusion

Epidemiological evidence concludes that a large viral hepatitis E outbreak was likely caused by consumption of juice with contaminated ice. Early stoppage of contaminated ice usage led to timely control of the outbreak.

Keywords: Viral hepatitis E, Outbreak, Ice, Contamination, Waterborne

Introduction

Hepatitis E is transmitted through feco–oral route primarily by consumption of contaminated water or food. Globally, hepatitis accounts for approximately “20.1 million incident HEV infections, 3.4 million symptomatic cases, 70,000 deaths, and 3000 stillbirths”.1 The incidence is highest in the Eastern and South Asian regions, accounting for 60% of hepatitis E global burden and 65% of global deaths. Despite the high endemicity of hepatitis E virus (HEV) in the South Asian region, the seroprevalence of antibodies to HEV is only 25% in young adults. Among the Indian population, there is low seroprevalence until the age of 15 years which reaches to 40% in young adults. In India, in 2013, 290,000 cases of acute viral hepatitis were notified; however, no specific data are available regarding the cases of viral hepatitis E.2

The disease is common in developing countries due to limited access to safe water and inadequate hygiene and sanitation. The disease occurs both in outbreaks and sporadic forms and mostly affects young adults. The outbreaks usually follow an episode of fecal contamination of drinking water and may affect several thousand people with clinical disease.1 The incubation period of HEV ranges from 2 to 10 weeks, with an average of 5–6 weeks. Usually, the infection is self-limiting and resolves within 2–6 weeks. Occasionally, serious complication in the form of fulminant hepatitis develops, and rarely people with this disease may die.1

Indian Armed Force's personnel form a special group of the vulnerable population as most of the soldiers are young adults with the majority of them non-immune to HEV, raising a potential of large outbreaks of hepatitis E with significant loss of man-days and combat capability.

The present study is based on an epidemiological investigation of an outbreak of viral hepatitis E in two military training centers (X & Y) during April to June 2016. Objectives of the study were to describe the epidemiology of the outbreak, to identify the risk factors, likely source and etiological agent of the outbreak, to initiate the control measures based on the findings of outbreak investigation, and to make recommendations to prevent such outbreaks in future to protect the troops.

Materials and methods

The outbreak was confirmed by comparing the data of the last five years in the same locality maintained at office of Station Health Organization (local health office). An initial line listing of cases was prepared based on hospital data of admitted cases in the only military hospital at military station ‘A’ located in Northern India. Population at risk and geographical limits of the outbreak were defined by reviewing the hospital/dispensary records and interview of doctors from neighboring areas.

Based on the symptoms of cases in the initial line list, the case definition for a suspected case for surveillance was defined as “the presence of icterus or history of passage of yellow-colored urine with or without fever/anorexia/vomiting/abdominal pain in a resident of military station A between 03 April 2016 and 06 June 2016”. A probable case was defined as “icterus or hepatomegaly on clinical examination with raised serum bilirubin (>1.2 mg/dl) in a suspect case”, whereas a confirmed case was defined as “laboratory-confirmed IgM-positive result for HEV in a suspect or probable case”.

An active case search was carried out to detect more cases in the community by conducting door-to-door case search. Ongoing passive surveillance was established by recording cases reported at the local military hospital and medical inspection rooms (providing primary health care to various troops and families at unit level) on a daily basis. A daily screening of troops was carried out during morning and evening roll calls of the troops and recruits in training centers to self-report the symptoms spelled out during roll calls on a daily basis to ensure early detection throughout the outbreak period. Surveillance was continued until 10 weeks after reporting the last case.

Based on the descriptive epidemiology results of the identified cases, an unmatched 1:1 case–control study was conducted to study the risk factors associated with the illness. For this purpose, a pretested, semistructured questionnaire was used to collect information regarding sociodemographics; date of joining the training center; details about the disease including the onset, symptoms, and treatment; history of movement; and history of drinking water and consuming food items from all possible sources during the incubation period. All available cases were included in the study. Controls equal to the number of cases were randomly selected from each center from nominal roll list of trainees and staff. A minimum sample size was calculated to be 133 cases and 133 controls with the assumption of expected exposure rates of 10% in controls, minimum odds ratio to detect being 3, 80% power, and 95% confidence level. Data were analyzed using Epi Info, version 7.2. Requisite informed consents were taken from all the participants. Considering the public health emergency, the ethical clearance was not warranted for this study; however, requisite permission was obtained from the head of the institute.

All cases were tested for serum bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). They were also tested for antibodies against HEV and hepatitis A virus by micro-capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and for antibodies against hepatitis B virus (HBsAg).

An environmental investigation was carried out to detect the likely sources of contaminated water. The blueprint of the water pipelines and the sewage system was obtained from the concerned authorities. Place distribution of the cases in relation to the water distribution line was mapped out. All other possible sources of water and food contamination were also studied. Records of routine water samples testing for residual chlorine and coliforms at the source and at consumer ends were reviewed for the last 3 months. Fresh water samples were also collected and were tested for residual chlorine and coliforms.

Results

Descriptive epidemiology

The population at risk at the time of outbreak was defined and estimated to be 15,183 which included troops and families of both the training centers and other units and defense civilians and their families residing within the military station A. The troops of the affected military training centers included two categories of persons, viz. trainees (undergoing training) and staff workers (supporting staff). Distribution of this population is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of cases in two co-located military training centers: hepatitis E outbreak, North India, April–June 2016 (n = 172).

| Category | Training center X |

Training center Y |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cases (a) | Total strength (b) | Attack rate (a/b) | Risk ratio (95% CI) | No. of cases (c) | Total strength (d) | Attack rate (c/d) | Risk ratio (95% CI) | |

| Staff workers | 29 | 247 | 11.7% | 1.9 (1.3–2.9) | 11 | 304 | 3.6% | 1.7 (0.8–3.4) |

| Trainees | 104 | 1763 | 5.9% | 28 | 1310 | 2.1% | ||

| Total | 133 | 2010 | 6.6% | 39 | 1614 | 2.4% | ||

CI, confidence interval.

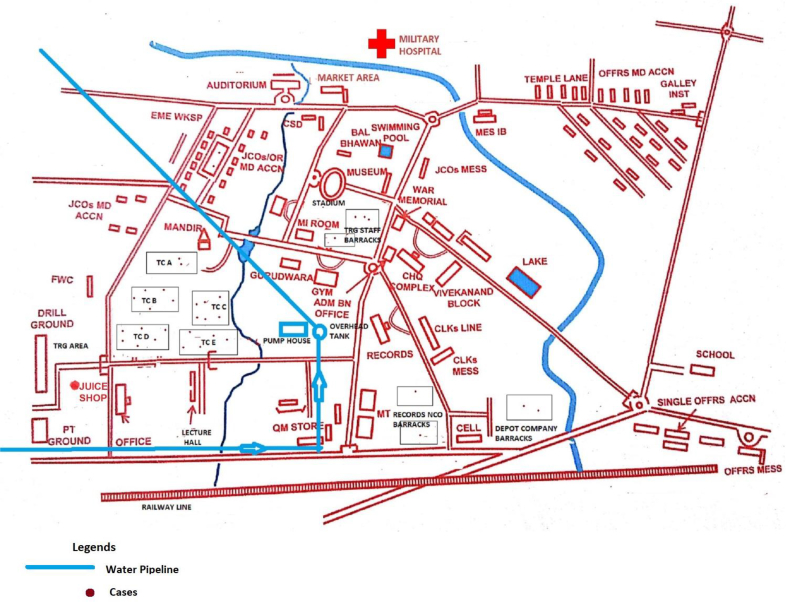

A total 172 cases (133 cases from training center X and 38 cases from training center Y) were identified. All cases were male with a median age of 21 years with a range of 19–42 yrs. No cases were reported from any of the family members including children and ladies residing in the military station A. Overall attack rate of hepatitis E among the troops of two training centers was 4.7%. Table 1 describes the distribution of cases among various categories of persons with category-specific attack rates, which was higher among staff workers than trainees in both the centers. The spot maps of both training centers X and Y, showed clustering of cases in the training company barracks, although quite a few cases were seen at other places too (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of hepatitis E cases as per the place of residence at the military training center X, North India, April–June 2016. TC, training company barracks where trainees were residing.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of hepatitis E cases as per the place of residence at the military training center Y, North India, April–June 2016. TC, training company barracks where trainees were residing.

The first case was reported on 03 Apr 2016 with a peak in the 2nd and 3rd week of May 2016, and thereafter, they declined with the last case reported on 24 Jun 2016 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Distribution of cases as per the date of onset of viral hepatitis E outbreak in two military training centers, North India, April–June 2016.

Clinical profile of the cases consisted of icterus (100%), yellow discoloration of urine (98.9%), anorexia (97.1%), fever (80.2%), vomiting/nausea (55.8%), and abdominal pain (52.3%) as depicted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Distribution of cases and controls according to place of residence in two co-located military training centers during hepatitis E outbreak, North India, April–June 2016 (n = 170).

| Subunit/Company | Place of residence | No. of cases | No. of controls | Total no. residing | Attack rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training center X | |||||

| Training battalion | NCO barrack | 6 | 4 | 32 | 18.8 |

| Family quarters | 5 | 3 | 43 | 11.6 | |

| Records | NCO barrack | 4 | 4 | 66 | 6.1 |

| Family quarters | 5 | 4 | 58 | 8.6 | |

| Depot company | NCO barrack | 3 | 1 | 15 | 20.0 |

| Family quarters | 5 | 3 | 33 | 15.2 | |

| Training company 1 | Barrack | 31 | 29 | 453 | 6.8 |

| Training company 2 | Barrack | 12 | 20 | 310 | 3.9 |

| Training company 3 | Barrack | 22 | 23 | 375 | 5.9 |

| Training company 4 | Barrack | 19 | 20 | 300 | 6.3 |

| Training company 5 | Barrack | 20 | 21 | 325 | 6.2 |

| Subtotal | 132 | 132 | 2010 | 6.6 | |

| Training center Y | |||||

| Training battalion | NCO barrack | 3 | 2 | 50 | 6.0 |

| Family quarters | 2 | 2 | 48 | 4.2 | |

| Records | NCO barrack | 2 | 2 | 86 | 2.3 |

| Family quarters | 1 | 1 | 41 | 2.4 | |

| Depot company | NCO barrack | 2 | 2 | 59 | 3.4 |

| Family quarters | 0 | 1 | 20 | 0.0 | |

| Training company A | Barrack | 5 | 5 | 240 | 2.1 |

| Training company B | Barrack | 5 | 5 | 240 | 2.1 |

| Training company C | Barrack | 6 | 6 | 256 | 2.3 |

| Training company D | Barrack | 7 | 7 | 302 | 2.3 |

| Training company E | Barrack | 5 | 5 | 272 | 1.8 |

| Subtotal | 38 | 38 | 1614 | 2.4 | |

| Total | 170 | 170 | 3624 | 4.7 | |

NCO, Non Commissioned Officer.

All cases were admitted and managed conservatively in the military hospital. Only one case had the complication of fulminant hepatitis (0.6%), and there were no deaths (Case Fatality Rate (CFR) = 0%). On attempt to find more cases in nearby hospitals, one of the civil hospitals reported a similar upsurge in the jaundice cases with 90 cases reported between April and June 2016 as compared with 3–7 baseline numbers of cases per month during the corresponding period. However, owing to non-availability of details of case records of these cases and area lying beyond the jurisdiction of investigators, they could not be included in the study.

Laboratory investigation

In the laboratory investigations, of 172 cases, 167 (97.1%) were positive for anti-HEV-IgM antibodies, 2 (1.2%) for both anti-HEV-IgM and anti-HAV-IgM antibodies, 1 (0.6%) for both anti-HEV-IgM antibodies and HBsAg and 2 (1.2%) were negative for any antibodies/antigens. Serum AST and ALT tests were carried out in all 172 cases and were found to be raised in all of them. The serum bilirubin level among cases ranged from 1.3 mg/dL to 29.5 mg/dL with a mean of 4.6 mg/dL (standard deviation = 3.1 mg/dL). One case had the complication of fulminant hepatitis with serum bilirubin level of 29.5 mg/dL, who was positive for hepatitis B in addition to hepatitis E. An interesting finding came out during the blood test was that seven cases were having coinfection with malaria and were positive for Plasmodium vivax infection on immunochromatography-based rapid diagnostic test.

Case–control study

A total of 170 available laboratory-confirmed cases and 170 controls were studied. Controls were comparable with cases in all baseline characteristics (Table 3). On analyzing the risk factors, history of consumption of juice from juice shops during the incubation period of viral hepatitis E (VHE) was significantly associated with the illness {odds ratio (OR), 14.3 (95% confidence interval [CI], 7.4–27.6)}. Being a staff worker was also found to be a significant risk factor with an OR of 1.7 (95% CI, 1.3–2.2). However, on stratified analysis, being a staff worker was found to be a confounder in the association of history of consumption of juice and VHE, which was adjusted for and yielded an adjusted OR of 15.7 (95% CI, 8.3–29.3). History of travel and consumption of food and drinks from outside the campus during incubation period were not significant as shown in Table 4.

Table 3.

Clinical profile of cases in hepatitis E outbreak in two co-located military training centers, North India, April–June 2016 (n = 172).

| Clinical manifestations | Numbers | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Icterus | 172 | 100% |

| Yellow discoloration of urine | 170 | 98.9% |

| Anorexia | 167 | 97.1% |

| Fever | 138 | 80.2% |

| Vomiting/Nausea | 96 | 55.8% |

| Abdominal Pain | 90 | 52.3% |

Table 4.

Risk factors among cases and control in hepatitis E outbreak in two co-located military training centers, North India, April–June 2016.

| Risk factor | Cases (n = 170) |

Controls (n = 170) |

Odds ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |||

| Consumed juice with ice from the juice shop in the campus | 160 | 93.0 | 83 | 48.3 | 14.3 | (7.2–27.6) |

| Being a staff worker | 51 | 23.2 | 40 | 14.8 | 1.7 | (1.3–2.2) |

| History of travel during incubation period | 102 | 59.3 | 89 | 51.7 | 1.4 | (0.8–2.0) |

| Consumed food or drinks from outside the campus | 100 | 58.1 | 96 | 55.8 | 1.1 | (0.7–1.7) |

Bold values of Odds Ratios signify statistically significant Odds Ratios.

Environmental investigation

Assessment of juice shops in training centers revealed the use of ice made from possibly contaminated, non-potable water, which was being produced in the only ice factory located in the town. On inspecting the ice factory, storage conditions of water used for ice making was found to be unhygienic. The only water sample collected from the ice factory yielded positive coliform test.

An environmental survey of drinking water pipelines supplying the two military centers showed 10 leakage points; however, none showed cross-contamination with sewage. A total of 416 water samples were tested between 15 January 2016 and 03 April 2016 (corresponding to the incubation period) for free residual chlorine from their pump house source and consumer ends, all of which showed satisfactory level of residual chlorine. A total of 105 water samples were subjected to bacteriological examination, and all were found to be satisfactory.

Discussion

This was a large outbreak of VHE in two co-located training centers associated with consumption of juice mixed with contaminated ice. This was one of the largest laboratory-confirmed outbreaks of VHE, which highlighted the role of surveillance of food and drinks hygiene sold by the vendors having the potential to cause VHE outbreak in spite of ensuring safe drinking water supply of the community.

VHE is one of the important causes of hepatitis and is responsible for a number of hepatitis outbreaks in India.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 VHE is primarily known to be a waterborne disease. The disease transmission in a community is largely determined by the level of population immunity, living conditions, water supply, and sewage disposal arrangements. Ice has not been documented as the known vehicle causing outbreaks of VHE in the published literature, as found by the authors in the PubMed search by using search words of “hepatitis E” and “outbreak” and “ice”.

The present study focuses on one of the largest laboratory-confirmed outbreaks of VHE, in which 170 of 172 suspect cases were laboratory confirmed and were thoroughly investigated for epidemiological investigations.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19

Varying attack rates of acute viral hepatitis have been reported from various studies from India ranging from 1.9 to 17%.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 The overall attack rate in the present study was 4.7%, comparable with the other studies. A higher attack rate among the staff workers compared with trainees is likely to be due to higher consumption rates of juice among staff workers. This was supported by its confounding effect observed on the association of juice consumption with VHE during stratified analysis.

This outbreak started in the first week of April 2016, reached its peak in the third week of May 2016, and then started declining, and no more cases were reported after the first week of June 2016 with the absence of any secondary peak. Similar findings were reported by various studies.6, 10, 15 Hepatitis E epidemics are mostly unimodal lasting over few weeks. Some outbreaks have been reported to be multimodal.15 The unimodal distribution in the present study could be explained by early implementation of the preventive measure during the second week of April 2016, when outbreak had just begun.

In the present study, the likely cause for the outbreak was consumption of juice mixed with contaminated ice. Most of the previous studies have described the contamination of drinking water from sewage water;9, 19 however, to the best of the authors' knowledge, there are no studies pointing out toward the role of contaminated ice causing VHE outbreak which are indexed in Medline (PubMed).

Only trainees and staff workers were affected sparing families and children in this outbreak. This can be explained by the localized exposure in the form of consumption of juice by trainees and staff workers from the juice shops within the campus of training centers. These juice shops were not commonly visited by the families and children.

Preventive measures in the form of stoppage of using suspected ice in juice, health education, and intensive surveillance were implemented from the second week of April 2016 which resulted in the decline of cases from the third week of May 2016. This observation was consistent with a median incubation period of VHE of 5–6 weeks, which is similar to the time period between the start of interventions (second week of April 2016) and observed decline in the cases (third week of May 2016) as seen in Fig. 3.

Thus, based on the observations, it is recommended to have a robust system of disease-specific surveillance supported with good laboratory support for recognizing early warning signals in the military stations. A sound investigation of the outbreak through well-designed and conducted epidemiological methods and prompt implementation of preventive measures based on the findings of the epidemiological investigations will help to prevent and control such outbreaks. There is also a need to strengthen food and drinks hygiene surveillance in and around military stations and to include relatively uncommon food items such as ice in the list of food items under surveillance.

Limitation of the study included the inability to investigate other cases from nearby hospitals, the possibility of recall bias, and inability to isolate HEV from ice and its source water samples. However, strong epidemiological evidence bridges the gap between these limitations.

The study concludes that this was a large laboratory-confirmed VHE outbreak, which occurred most likely due to consumption of juice mixed with contaminated ice; however, recognition of early warning signals, timely investigation, and application of specific control measures contained the outbreak in a timely manner and decreased morbidity and mortality significantly.

Disclosure of competing interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2016. Hepatitis E. Fact Sheet 280.www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs280/en/ Available from: [Accessed 30 November 2016] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shrivastava Akash. vol. 3. Quarterly Newsletter from the National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC); 2014. pp. 1–2. (Hepatitis in India: Burden, Strategies and Plans). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viswanathan R. Infectious hepatitis in Delhi (1955–56) A critical study: epidemiology. Indian J Med Res. 1957;45:49–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tandon B.N., Gandhi M.B., Joshi Y.K., Irshad M., Gupta H. Hepatitis virus-non-A and non B-the cause of a major public Health problem in India. Bull WHO. 1985;63:931–934. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Das P., Adhikary K.K., Gupta P.K. An outbreak investigation of viral hepatitis E in South dumdum municipality of Kolkata. Indian J Community Med. 2007;32:84–85. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarguna P., Rao A., Sudha Ramana K.N. Outbreak of acute viral hepatitis due to hepatitis E virus in Hyderabad. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2007;25:378–382. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.37343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chauhan N.T., Prajapati P., Trivedi A.V., Bhagyalaxmi A. Epidemic investigation of the jaundice outbreak in Girdharnagar, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India, 2008. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:294–297. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.66864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vyas S., Parikh S., Kapoor R., Patel V., Solanki A. Investigation of an epidemic of hepatitis in Ahmedabad city. Natl J Community Med. 2010;1:27–29. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh P.M., Handa S.K., Banerjee A. Epidemiological investigation of an outbreak of viral hepatitis. MJAFI. 2006;62:332–334. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(06)80100-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raval D.A., Chauhan N.T., Katara R.S., Mishra P.P., Zankar D.V. Outbreak of hepatitis E with bimodal peak in rural area of Bhavnagar, India, 2010. Ann Trop Med Publ Health. 2012;5:190–194. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martolia H.C., Hutin Y., Ramachandran V., Manickam P., Murhekar M., Gupte M. An outbreak of hepatitis E tracked to a spring in the foothills of the Himalayas, India, 2005. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2009;28:99–101. doi: 10.1007/s12664-009-0036-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Das D.K., Biswas R., Pal D. An epidemiological investigation of jaundice outbreak in A slum area of Chetla, Kolkata. Indian J Publ Health. 2005;48:151–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh V., Raje M., Nain C.K., Singh K. Routes of transmission in the hepatitis E epidemic of Saharanpur. Trop Gastroenterol. 1998;19:107–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gurav Y.K., Kakade S.V., Kakade R.V., Kadam Y.R., Durgawale P.M. A study of hepatitis E outbreak in rural area of Western Maharashtra. Indian J Community Med. 2007;32 1828-4. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Somani S.K., Aggarwal R., Naik S.R., Srivastava S., Naik S. A serological study of intrafamilial spread from patients with sporadic hepatitis E virus. Infection. J Viral Hepat. 2003;10:446–449. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhagyalaxmi A., Gadhvi M., Bhavsar B.S. Epidemiological investigation of an outbreak of infectious hepatitis in Dakor town. Indian J Community Med. 2007;32:277–279. [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO . 2001. Hepatits E, WHO/CSR Web Site.http://www.who.int/emc Available from: [Accessed 9 August 2017] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banerji A., Sahni A.K., Rajiva, Nagendra A., Saiprasad G.S. Outbreak of viral hepatitis E in a regimental training centre. Med J Armed Forces India. 2005;61:326–329. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(05)80055-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Awsathi Sadhana, Rawat1 Vinita, Mohan Chandra, Rawat Singh, Semwal Vandana, Bartwal Sunil Janki. Epidemiological investigation of the jaundice outbreak in Lalkuan, Nainital district, Uttarakhand. Indian J Community Med. April 2014;39(2) doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.132725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]