Abstract

Literature search forms the foundation of most clinical decisions about patient management and is the starting point for all bedside/bench-side research. Despite being an essential tool in the armamentarium of all medical professionals and researchers, literature search remains a challenge, often resulting in frustration and waste of time (and resources). This article aims to provide a beginner's guide to information seekers for a step-wise approach to literature search on web-based databases.

Keywords: PubMed, Embase, Web of science, Database

Introduction

David Sackett and his colleagues at McMaster University defined Evidence Based Medicine (EBM) as “the integration of the best research evidence with clinical experts and patient values.”1 Though developed in the 1980s, the definition and its concepts continue to guide most clinicians and researchers to date.2 Literature search is a systematic, well thought, and well-organized search of the published data to identify good quality research on any specific topic. The reasons for conducting a literature search may vary, ranging from clinical decision-making per EBM to further research on a related topic. A well-conducted literature search can help broaden the knowledge base, allow for critical appraisal of research, and be used as a guide in planning original research and writing the Review of Literature in dissertations.2 An effective and efficiently done literature search forms the cornerstone of any good research project.

In this modern era of overwhelming technology, the literature that can be searched is exhaustive, and the sources depend on various factors, including the format (print or electronic), cost factor (paid or free), level of access etc., to name a few. By the scope and content of information, literature can be divided into primary, secondary and tertiary sources. Primary sources are the original publication of an expert's new evidence, conclusions, and proposals (for example, case reports, randomized controlled trials, etc.) published in a peer-reviewed journal. Secondary sources are systematic review articles where material derived from primary sources is inferred and evaluated. Tertiary literature sources consist of collections that compile information from primary or secondary sources (for example, reference books).

The literature demonstrates three significant impediments to practising and utilizing EBM. Firstly, most researchers have insufficient knowledge on conducting a literature review; second, many cite time constraints to find the best available evidence. Third, the best available evidence may be weak.3, 4, 5, 6, 7 This review attempts to resolve the first issue by describing a systematic stepwise approach to a web-based literature search, from framing a comprehensive search question to searching a database.

Step one: asking the right question

Central to conducting any literature search is defining the search query. This is vital because the nature of the question and the type of requirements will dictate the search process. For example, queries related to a particular disease/disorder or drug can be studied in sources such as Medscape (www.medscape.com) or Up to Date (www.uptodate.com) or DynaMed (www.dynamed.com). However, a more comprehensive literature search may be needed if the “clinical” query could not be answered in the databases mentioned above or if a research project is being undertaken.8 These detailed literature searches are usually undertaken in databases like PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO or Web of Science.9,10

Before undertaking a literature search, the query should be expressed in words in a question (research question) format. The question should be then broken down into its components/concepts and organized into the “PICO(T)” format, which is a practical approach for formulating research questions (Table 1).11 Each component of the question is then studied, and a list of all possible related words, different spellings and synonyms are listed. These semantically (and lexically) similar words can be identified by brainstorming with colleagues or by retrieving preliminary information from books, DynaMed, UpToDate or PubMed clinical queries.8,12,13 These keywords will form the cornerstone of the literature search.

Table 1.

Formulating the research question as per PICO(T) format.

| Components of PICO(T) | Description |

| P-Population | Refers to the study population or subjects who would be included in the study |

| I-Intervention | Refers to the specific intervention (investigation/treatment modality) which will be administered to the study population and whose impact would be studied |

| C-Control | Refers to the reference group which would be used for comparison of the differences in outcome with the intervention |

| O-Outcome | Predefined outcomes on the basis of which effectiveness of the intervention will be measured |

| T-Time | The duration of data collection |

Step two: determine the appropriate database(s)

The resources for literature search can be classified into search engines or databases (Table 2). A search engine is a program that searches for and identifies items in a database corresponding to keywords and characters specified by the user. The database searches for relevant published and academic resources. The information obtained from databases is likely to be more relevant and reliable, having gone through peer review.14

Table 2.

Electronic databases for literature search.

| Database | Web address | Description |

|

PubMed MEDLINE (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval system) |

www.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed | PubMed is hosted at the National Library of Medicine (NLM), National Institute of Health (NIH) and contains more than 34 million citations for biomedical literature from MEDLINE, life science journals and online books. MEDLINE is the NLM's bibliographic database with more than 29 million references from more than 5600 journals. Access to MEDLINE is provided through various websites including PubMed and Ovid. |

| EMBASE (Excerpta Medica Database) | http://www.elsevier.com/online-tools/embase | EMBASE is a biomedical and pharmacological bibliographic database of published literature. It is owned and operated by Elsevier and contains over 32 million records from >8500 currently published journals from 1947 to the present. Access to this database is only through subscription. |

| Cochrane Library | https://www.cochranelibrary.com | The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews is the leading database for systematic reviews in healthcare. It has more than 5000 systematic reviews about healthcare and is a valuable source of information for health care providers, decision makers and researchers. |

| SCOPUS | https://www.scopus.com | Scopus is Elsevier's abstract and citation database covering book series, journals, and trade journals in the subject fields of life sciences, social sciences, physical sciences and health sciences |

| CINAHL (The Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health) | www.cinahl.com | CINAHL indexes the top nursing and allied health literature from nursing journals and publications. |

| Web of Science | www.webofscience.com | This is a paid access platform that provides access to more than 171 million records from multiple disciplines of science including conference proceedings and books. |

| TRIP (Turning Research Into Practice) database | www.tripdatabase.com | TRIP was launched in 1997 as a medical search engine with a focus on EBM content. The website provides current best evidence of studies, syntheses, synopses and systems. |

Step three: develop a search strategy for different database(s)

Each database has its specific (though overlapping) nuances while a literature search is being performed. Outlined below is the strategy for commonly used databases.

Literature search on PubMed

The literature search on PubMed can be improved by understanding the below-mentioned concepts about its search engine.

-

(a)

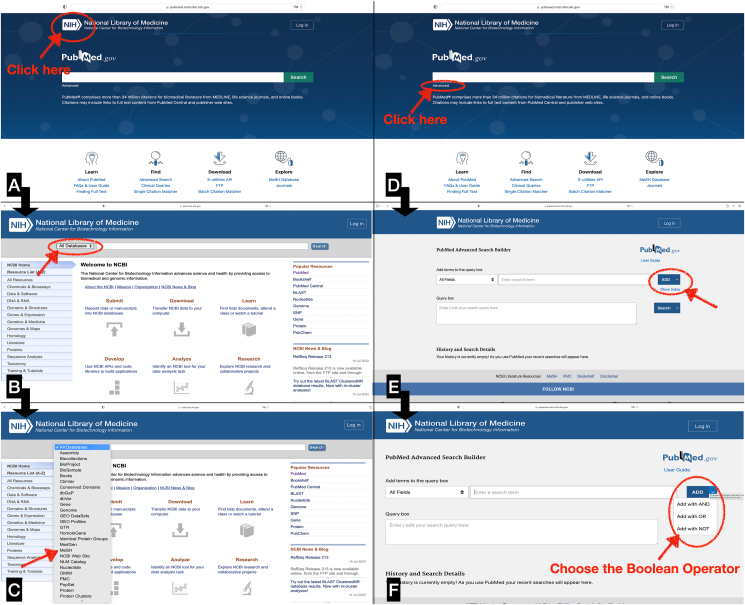

Medical subject headings: Medical Subject Headings, popularly known as MeSH, in simple words, is a thesaurus that facilitates literature search. Different terminologies are identified and clubbed under a single heading (MeSH headings or descriptors). Thus, by using MeSH terms while performing a search, the various synonyms of a term are automatically included in the search query. For example, in literature, the concept of COVID-19 infection has been described in multiple ways: COVID-19, novel coronavirus infection, corona virus, nCoV, 2019 novel corona virus, and SARS-CoV-2. If one searches with the MeSH term ‘COVID-19′, the researcher will find articles on this subject no matter which words were used to describe this concept. This is made possible because each article in a journal and every chapter in a book, while being indexed in PubMed, is tagged with 5–15 most specific MeSH headings. Subheadings, also called qualifiers, are attached to the headings to describe a particular aspect of a concept. Supplementary concept records include protocols and rare disease terms to make the search more specific. Publication characteristics define the type of publication being indexed (format of the publication) or aspects of the research (research design). MeSH headings are organized in a “tree” with 16 main branches, each with many levels of sub-branches, and each header has a position in the hierarchy. While a word is typed in the search bar of PubMed, PubMed attempts to map it to one or more MeSH concepts and will automatically add its MeSH term(s) to the original query. However, searching with MeSH alone is not enough because MeSH terms are manually assigned to articles. As this takes time, the latest articles will not have been assigned any MeSH terms yet and, therefore, will not appear in the search results if only MeSH terms are used. The search with MeSH can be done directly from the webpage (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/), or one may navigate to MeSH search from the homepage of PubMed (Figs. 1A–C)

-

(b)

Boolean operators: Boolean algebra (or logic) is the process of combining search terms by using the words “AND” “OR” and “NOT” which act as “Boolean operators” (Fig. 1D–F). The Boolean operators are always written in upper case. Using these allows the researcher to refine the search criteria. Using “AND” retrieves only the articles containing all combined terms. For example, “seizure” AND “lorazepam” will only reflect articles relating to both seizure and lorazepam. Using “OR” expands the search and produces all the literature where any of the combined terms are present. “Seizure” OR “lorazepam” will retrieve items containing seizure, items containing lorazepam and items containing both. The use of “OR” is also helpful for connecting synonyms. For example, “seizure” OR “febrile seizure” OR “epilepsy.” Using NOT will restrict the search, eliminating all the results containing a particular search term. For example, ‘’“seizure” NOT ‘’“lorazepam” will reflect articles having the term seizure but will omit all the articles that mention lorazepam. NOT should be used carefully as it can leave out articles that may be useful.

-

(c)

Keywords: These, as described in the previous step, are used to describe the idea/concept (Table 3). They can be single words or phrases. Often there are differences in how a concept is characterized by the authors and how it is described by the people searching for literature. Hence it is imperative to identify similar meaning words. The (key)words can be generated by browsing entry terms listed in MeSH, browsing through terminology in articles, and doing a few preliminary searches. For example, the alternative word convulsions can be included while searching for the keyword seizure. Also, when looking for a particular phrase in PubMed (words in exact order), double quotation marks (“ … ") should be used. This disables PubMed's automatic term mapping function and ensures they are searched together. For example, searching for gene therapy will search for “gene” AND “therapy”; while searching for “gene therapy” searches for the occurrence of gene therapy in that order.

-

(d)

Truncation: An asterisk (∗) can be used to search for word variations in PubMed. PubMed will search for words that start with the root word. For example, searching with child∗ will also search for: child, childhood, children, etc.

-

(e)

Wildcards: Wildcards work by inserting "?" (a wildcard symbol) into the middle of the search term. This allows for words that contain an additional character at the point of the wildcard symbol to be retrieved; words that do not have an additional character will still be retrieved. This is particularly useful for searching for items with American English and British English spelling variations. For example, behavio?r will return searches with behaviour and behavior.

-

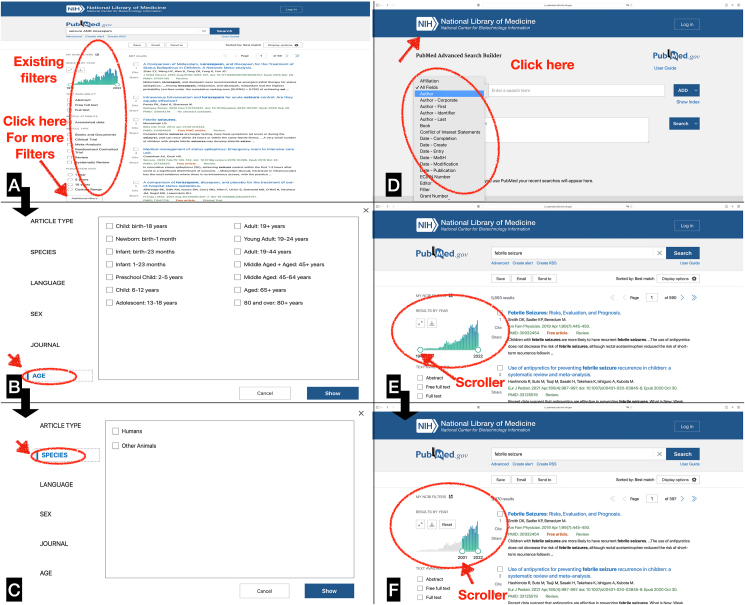

(f)

Filters: PubMed has built-in filters to narrow down the results (Fig. 2A–C). Commonly used filters include article type (for example, clinical trial or meta-analysis or systematic review etc.), publication date, studies related to humans or other animals, the language of the article, age group included etc.

-

(g)

Search fields: Search field tags specify the database to be searched. Different search field tags may be: affiliation (for authors), article identifier (for example, DOI), author identifier (for example, ORCID), completion date, etc (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 1.

The figure explains pictorially different steps involved with pubmed search. The figure has to be read longitudinally from A→B→C and then from D→E→F. In panel A, the researcher browses to the PubMed homepage (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov); the researcher can either type the query in the search bar or can click on “NIH” (as highlighted by red circle). This will take him to the next page highlighted in panel B. Here the individual clicks on “All databases” and scrolls to “MeSH” (panel C). Then typing the word in search bar will generate the relevant MeSH term. Panels D to F highlight the use of Boolean operators. Either the keywords can be typed in the search bar and combined with AND, OR, NOT in upper case or one can click on “Advanced” (circled red in Panel D). The new page (panel E) will give options for search and operators. One may choose the Boolean operators by scrolling “ADD” function (circled red in panel F).

Table 3.

Steps to performing PubMed search (the details of each step are further elucidated in Table 4).

| Steps | Description | Example |

| 1 | Formulate the relevant research question | Are antibiotics efficacious in management of sore throat? PICO format: Patients: Individuals with sore throat Intervention: antibiotics administration Control: Did not receive antibiotics Outcome: Efficacy in reducing symptoms |

| 2 | Identify the concepts and associated keywords | |

| 2a | Identify the concepts | Concept 1: antibiotics Concept 2: sore throat |

| 2b | Identify the key words associated with each concept | Identify the keywords associated with concept 1: “antibiotics”; for example: antibiotic OR anti-bacterial agents OR antimicrobial agents Identify the keywords associated with concept 2: “sore throat”; for example: Pharyngitis OR Nasopharyngitis OR Tonsillitis OR “inflamed throat” |

| 3 | Prepare for PubMed search | |

| 3a. | Add MeSH terms for each concept | MeSH term for Concept 1: MeSH term for antibiotics: “anti-bacterial agents"[MeSH Terms] MeSH term for Concept 2: MeSH term for sore throat: “pharyngitis"[MeSH Terms] |

| 3b. | Add the Boolean Operators, truncations where applicable and then add double quotes across multiword phrases | For example for concept 1: antibiotic∗ OR “anti-bacterial agent∗” For example for concept 2: Pharyngit∗ OR Nasopharyngit∗ OR rhinopharyngi∗ OR Tonsillit∗ OR “inflamed tonsil∗” |

| 3c. | Merge the keywords and MeSH terms for each concept | Concept 1: antibiotic∗ OR “anti-bacterial agent∗” OR “anti-bacterial agents"[MeSH Terms] Concept 2: Pharyngit∗ OR nasopharyngitis OR rhinopharyngitis OR tonsillitis OR “inflamed throat” OR “inflamed tonsils” OR “infected throat” OR “infected tonsils” OR “sore throat” OR “pharyngitis"[MeSH Terms] |

| 3d. | Perform search for individual concepts and then merge the two concepts using AND | (antibiotic∗ OR “anti-bacterial agent∗” OR “anti-bacterial agents"[MeSH Terms]) AND pharyngitis OR nasopharyngitis OR rhinopharyngitis OR tonsillitis OR “inflamed throat” OR “inflamed tonsils” OR “infected throat” OR “infected tonsils” OR “sore throat” OR “pharyngitis"[MeSH Terms] |

Fig. 2.

The figure explains the use of filters in PubMed. Panels A to C illustrate the use of filters. The filters are on left hand in a columnar fashion of search page (circled red in panel A). Clicking on “Additional filters” (marked by red arrow in panel A) will open a new box from which different filters can be chosen (panel B and C). The additional filters can be chosen based on search strategy; for example, a definite age group (Panel B) or specifically human studies (Panel C). Panel D highlights the other search strategies that can be used like authors, books, editors, etc. Panel E and F highlight the use of time filter. Searching for “febrile seizure” generates more than 5800 results (panel E). By using the scroll bar if the results are filtered to 2001 to 2022, the output can be reduced to nearly 4000 (panel F).

There can be some unique scenarios while searching PubMed. For example, if one wants to find a specific article quickly, they may use the PubMed ID (PMID) or the article's title. Also, publications by a particular author can be found by entering their surname followed by their initials or first name. Suppose too many results are retrieved while performing the search (Fig. 2 E and F), in that case, one may restrict to recent articles by using the filters or limit the search by study type (for example, clinical trial) or user narrower search terms. Similarly, suppose too few results are retrieved, in that case, one can broaden the search by checking relevant articles for words (in the title and abstract) and assigned MeSH terms and adding those to the search strategy or going one step higher in the hierarchy of MeSH terms or by searching other databases. Once complete, the search can be saved on PubMed by pre-creating a My NCBI account.

Literature search on EMBASE

The literature search in EMBASE uses concepts similar to PubMed with slight alterations.

-

(a)

Keywords and Emtree: The keywords are searched like PubMed; they can be single words or phrases, and phrases are searched in double quotes. Emtree replaces the MeSH terminology of PubMed in EMBASE. Just like MeSH, Emtree terms are ascribed to articles to describe their contents in a standardized way. Articles entered in EMBASE are automatically assigned Emtree terms (using an algorithm). These Emtree terms are then manually checked and corrected by EMBASE indexers.

-

(b)

Explode, and no explode: “Explode” (command:/exp) will search with all subject headings below the main heading included and bring up all results listing any of these terms subject heading, subheadings, combinations. No explode (command:/de) retrieves only the term specified and no headings below it. Major focus (command:/mj) will only search for the chosen Emtree term as the primary term. For example, ‘“diabetes mellitus”/de only finds records indexed with ‘“diabetes mellitus,” not ‘“diabetic complication’ or ‘“diabetic obesity’,” etc.

-

(c)

Field tags: The field tags restrict the search to specific article sections like the title/abstract etc. The field limits are located on the “Advanced Search” page under the link “fields” The default is “all fields,” but entering a search term and then clicking on one of these limits (for example, clicking “Abstract: ab”) will add it to the search builder. The common commands include ti (Title), ab (Abstract), au (Author), ad (Author Address/Affiliation), and jt (Journal Title).

-

(d)

Truncation and wildcard: The truncation symbol (∗) and wildcard symbol (?) and their application are the same as in PubMed.

-

(e)

Proximity searching: EMBASE allows proximity operators to search for terms within a certain number of words from each other. There are two types of proximity searching: NEAR/n and NEXT/n. NEAR/n searches for terms within the specified number of words from each other in either direction. (Therapy NEAR/5 sleep) looks for the word therapy within 5 words of sleep. NEXT/n searches for terms within the specified number of words from each other, in the order the words are typed. For example, therapy NEXT/5 sleep would find “therapy for improved sleep,” but it would not find “sleep therapy.”

-

(f)

B.operators: As in PubMed, the Boolean operators (AND, OR, and NOT) are used to combine search terms.

Generally, EMBASE is the second most commonly searched database. The keywords and MeSH terms identified for PubMed would work similarly in EMBASE. However, if one identifies additional keywords to use in EMBASE, they should be added to the PubMed and other database searches.

Literature search on Web of Science

Web of Science provides access to a collection of databases. These include: (a) Web of Science Core Collection, which includes details of scholarly journal articles from all academic subject areas, details of conference proceedings from science and technology conferences and details of book chapter references from selected science, social science and humanities books; (b) BIOSIS Citation Index which combines the databases Biological Abstracts and Biological Abstracts Reports, Reviews and Meetings covering pre-clinical and experimental research in the life sciences. While searching for a keyword, the keyword is entered in the search box(es) while ensuring “Topic” is selected in the drop-down menu. The search terms are then combined using Boolean Operators as described above. The wild cards and truncation symbols are also similar to PubMed and Embase. In addition, the feature proximity search (command: NEAR/x) can be used to search for words that are close to each other without being in an exact phrase. For example, sleep NEAR/5 therapy will find “sleep therapy” “therapy of sleep” “therapy for improved sleep”, etc. The/x element says how many other words will be allowed between the two keywords; in this case, five—just using NEAR will be treated as NEAR/15. It doesn't matter what order the words are in.

Step four: saving the research

Literature search can be laborious and may take several days to complete. Hence search results must be saved along the way. Most databases mentioned above allow the searches to be saved. For example, creating a free NCBI account in PubMed is available to the public and enables users to save previous searches. The retrieved literature can be downloaded to go through the articles. Reference manager software is a powerful tool for organizing, storing, and sharing references. It will also save time when creating a bibliography. Both free version (Mendeley, Zotero) and commercial license-based (EndNote, RefWorks) reference management software are available for managing the retrieved literature.

Conclusion

This article gives a systematic stepwise approach to performing a literature search. A demonstration of search strategy for PubMed is detailed in Table 4. This is not comprehensive, and many nuances are learnt while conducting the search in person. However, this article aims to provide a head-start and gives an overview of this seemingly (but not as much) challenging arena.

Table 4.

Search strategy on PubMed (demonstrated using an example).

| Step 1 |

| Formulating the research question Research Question: Are antibiotics efficacious in management of sore throat? PICO format: Patients: Individuals with sore throat Intervention: antibiotics administration Control: Did not receive antibiotics Outcome: Efficacy in reducing symptoms |

| Step 2 |

|

Formulation of concepts and keywords associated with research question. Concept 1: antibiotics Concept 2: sore throat Keywords associated with antibiotics (concept 1) Antibiotics OR anti-bacterial agents OR azithromycin OR clarithromycin OR erythromycin OR roxithromycin OR macrolide OR cefamandole OR cefoperazone OR cefazolin OR OR cefotaxime OR cephalexin OR cephaclor OR cephadroxil OR cephradine OR cefoxitin OR cephalosporin OR cefpodoxime OR cefuroxime OR cefixime OR amoxicillin OR amoxycillin OR ampicillin OR sulbactum OR tetracycline OR clindamycin OR lincomycin OR doxycycline OR fluoroquinolone OR ciprofloxacin OR fleroxacin OR ofloxacin OR pefloxacin OR moxifloxacin OR clindamycin OR penicillin OR ticarcillin OR beta-lactam OR levofloxacin OR trimethoprim OR co-trimoxazole Keywords associated with sore throat (Concept 2) Pharyngitis OR Nasopharyngitis OR Tonsillitis OR “inflamed throat” OR “inflamed tonsil” or “sore throat” |

| Step 3: Making keywords and MeSH terms ready for search | |

|

3a: Adding MeSH terms Concept 1: MeSH term for antibiotics: ““anti-bacterial agents”[MeSH Terms] Concept 2: MeSH term for sore throat: “pharyngitis”[MeSH Terms] 3b: Add the Boolean Operators, truncations where applicable and then add double quotes across multiword phrases | |

| Concept 1: antibiotics | |

| Boolean | Antibiotics OR anti-bacterial agents OR azithromycin OR clarithromycin OR erythromycin OR roxithromycin OR macrolide OR cefamandole OR cefoperazone OR cefazolin OR OR cefotaxime OR cephalexin OR cephaclor OR cephadroxil OR cephradine OR cefoxitin OR cephalosporin OR cefpodoxime OR cefuroxime OR cefixime OR amoxicillin OR amoxycillin OR ampicillin OR sulbactum OR tetracycline OR clindamycin OR lincomycin OR doxycycline OR fluoroquinolone OR ciprofloxacin OR fleroxacin OR ofloxacin OR pefloxacin OR moxifloxacin OR clindamycin OR penicillin OR ticarcillin OR beta-lactam OR levofloxacin OR trimethoprim OR co-trimoxazole |

| Truncation | Antibiotic∗ OR anti bacterial agent∗ OR azithromycin∗ OR clarithromycin∗ OR erythromycin∗ OR roxithromycin∗ OR macrolid∗ OR cefamandole∗ OR cefoperazone∗ OR cefazolin∗ OR cefotaxime∗ OR cephalexin∗ OR cephaclor∗ OR cephadroxil∗ OR cephradine∗ OR cefoxitin∗ OR cephalosporin∗ OR cefpodoxime∗ OR cefuroxime∗ OR cefixime∗ OR amoxicillin∗ OR amoxycillin∗ OR ampicillin∗ OR sulbactum∗ OR tetracyclin∗ OR clindamycin∗ OR lincomycin∗ OR doxycyclin∗ OR fluoroquinolon∗ OR ciprofloxacin∗ OR fleroxacin∗ OR ofloxacin∗ OR pefloxacin∗ OR moxifloxacin∗ OR clindamycin∗ OR penicillin∗ OR ticarcillin∗ OR beta-lactam∗ OR levofloxacin∗ OR trimethoprim∗ OR co-trimoxazol∗ |

| Double quotes across multiword phrases after the asterisk | Antibiotic∗ OR “anti bacterial agent∗” OR azithromycin∗ OR clarithromycin∗ OR erythromycin∗ OR roxithromycin∗ OR macrolid∗ OR cefamandole∗ OR cefoperazone∗ OR cefazolin∗ OR cefotaxime∗ OR cephalexin∗ OR cephaclor∗ OR cephadroxil∗ OR cephradine∗ OR cefoxitin∗ OR cephalosporin∗ OR cefpodoxime∗ OR cefuroxime∗ OR cefixime∗ OR amoxicillin∗ OR amoxycillin∗ OR ampicillin∗ OR sulbactum∗ OR tetracyclin∗ OR clindamycin∗ OR lincomycin∗ OR doxycyclin∗ OR fluoroquinolon∗ OR ciprofloxacin∗ OR fleroxacin∗ OR ofloxacin∗ OR pefloxacin∗ OR moxifloxacin∗ OR clindamycin∗ OR penicillin∗ OR ticarcillin∗ OR beta-lactam∗ OR levofloxacin∗ OR trimethoprim∗ OR co-trimoxazol∗ |

| Merge the keywords and MeSH terms | Antibiotic∗ OR anti-bacterial agent∗ OR azithromycin∗ OR clarithromycin∗ OR erythromycin∗ OR roxithromycin∗ OR macrolid∗ OR cefamandole∗ OR cefoperazone∗ OR cefazolin∗ OR cefotaxime∗ OR cephalexin∗ OR cephaclor∗ OR cephadroxil∗ OR cephradine∗ OR cefoxitin∗ OR cephalosporin∗ OR cefpodoxime∗ OR cefuroxime∗ OR cefixime∗ OR amoxicillin∗ OR amoxycillin∗ OR ampicillin∗ OR sulbactum∗ OR tetracyclin∗ OR clindamycin∗ OR lincomycin∗ OR doxycyclin∗ OR fluoroquinolon∗ OR ciprofloxacin∗ OR fleroxacin∗ OR ofloxacin∗ OR pefloxacin∗ OR moxifloxacin∗ OR clindamycin∗ OR penicillin∗ OR ticarcillin∗ OR beta-lactam∗ OR levofloxacin∗ OR trimethoprim∗ OR co-trimoxazol∗ OR “anti-bacterial agents"[MeSH Terms] |

| Concept 2: sore throat | |

| Boolean | Pharyngitis OR nasopharyngitis OR rhinopharyngitis OR tonsillitis OR inflamed throat OR inflamed tonsils OR infected throat OR infected tonsils or sore throat |

| Truncation | Pharyngitis OR nasopharyngitis OR rhinopharyngitis OR tonsillitis OR inflamed throat OR inflamed tonsil∗ OR infected throat OR infected tonsils OR sore throat |

| Double quotes across multiword phrases after the asterisk | Pharyngits OR nasopharyngitis OR rhinopharyngitis OR tonsillitis OR “inflamed throat” OR “inflamed tonsil∗” OR “infected throat” OR “infected tonsils” OR “sore throat” |

| Merge the keywords and MeSH terms | Pharyngitis OR nasopharyngits OR rhinopharyngitis OR tonsillitis OR “inflamed throat” OR “inflamed tonsil∗” OR “infected throat” OR “infected tonsils” OR “sore throat” OR “pharyngitis"[MeSH Terms] |

| Step 4: Perform the search | ||

| #1 | Antibiotic∗ OR anti-bacterial agent∗ OR azithromycin∗ OR clarithromycin∗ OR erythromycin∗ OR roxithromycin∗ OR macrolid∗ OR cefamandole∗ OR cefoperazone∗ OR cefazolin∗ OR cefotaxime∗ OR cephalexin∗ OR cephaclor∗ OR cephadroxil∗ OR cephradine∗ OR cefoxitin∗ OR cephalosporin∗ OR cefpodoxime∗ OR cefuroxime∗ OR cefixime∗ OR amoxicillin∗ OR amoxycillin∗ OR ampicillin∗ OR sulbactum∗ OR tetracyclin∗ OR clindamycin∗ OR lincomycin∗ OR doxycyclin∗ OR fluoroquinolon∗ OR ciprofloxacin∗ OR fleroxacin∗ OR ofloxacin∗ OR pefloxacin∗ OR moxifloxacin∗ OR clindamycin∗ OR penicillin∗ OR ticarcillin∗ OR beta-lactam∗ OR levofloxacin∗ OR trimethoprim∗ OR co-trimoxazol∗ OR “anti-bacterial agents"[MeSH Terms] |

1,007,017results

|

| #2 | Pharyngitis OR Nasopharyngitis OR rhinopharyngitis OR tonsillitis OR “inflamed throat” OR “inflamed tonsil∗” OR “infected throat” OR “infected tonsil∗” OR “sore throat” OR “pharyngitis"[MeSH Terms] |

50,676 results

|

| #3 | #1 AND #2 | 11,338

|

Disclosure of competing interest

The authors have none to declare.

Ethical publication statement

We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this article is consistent with those guidelines.

References

- 1.Straus S.E., Glasziou P., Richardson W.S., Haynes R.B. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2018. Evidence-based Medicine E-Book: How to Practice and Teach EBM. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Isaacs D. How to do a quick search for evidence. J Paediatr Child Health. 2014;50(8):581–585. doi: 10.1111/jpc.12514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dawes M., Sampson U. Knowledge management in clinical practice: a systematic review of information seeking behavior in physicians. Int J Med Inf. 2003;71(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(03)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riordan F.A., Boyle E.M., Phillips B. Best paediatric evidence; is it accessible and used on-call? Arch Dis Child. 2004;89(5):469–471. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.029413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D'Alessandro D.M., Kreiter C.D., Peterson M.W. An evaluation of information-seeking behaviors of general pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2004;113(1 Pt 1):64–69. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ely J.W., Osheroff J.A., Ebell M.H., et al. Obstacles to answering doctors' questions about patient care with evidence: qualitative study. BMJ. 2002;324(7339):710. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7339.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coumou H.C., Meijman F.J. How do primary care physicians seek answers to clinical questions? A literature review. J Med Libr Assoc. 2006;94(1):55–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson E.A., Gann L.B., Cressman E.N.K. Learning to successfully search the scientific and medical literature. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2019;24(2):289–293. doi: 10.1007/s12192-019-00984-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu Z. PubMed and beyond: a survey of web tools for searching biomedical literature. Database. 2011;2011:baq036. doi: 10.1093/database/baq036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin S., Hussain Z., Boyle J.G. A beginner's guide to the literature search in medical education. Scot Med J. 2017;62(2):58–62. doi: 10.1177/0036933017707163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richardson W.S., Wilson M.C., Nishikawa J., Hayward R.S. The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J Club. 1995;123(3):A12–A13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cassidy L.C., Leenaars C.H.C., Rincon A.V., Pfefferle D. Comprehensive search filters for retrieving publications on nonhuman primates for literature reviews (filterNHP) Am J Primatol. 2021;83(7) doi: 10.1002/ajp.23287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeganova L., Kim S., Chen Q., Balasanov G., Wilbur W.J., Lu Z. Better synonyms for enriching biomedical search. J Am Med Inf Assoc. 2020;27(12):1894–1902. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demner-Fushman D., Hauser S.E., Humphrey S.M., Ford G.M., Jacobs J.L., Thoma G.R. MEDLINE as a source of just-in-time answers to clinical questions. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2006:190–194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]