Abstract

Transcription of the ferric citrate transport genes is initiated by binding of ferric citrate to the FecA protein in the outer membrane of Escherichia coli K-12. Bound ferric citrate does not have to be transported but initiates a signal that is transmitted by FecA across the outer membrane and by FecR across the cytoplasmic membrane into the cytoplasm, where the FecI extracytoplasmic-function (ECF) sigma factor becomes active. In this study, we isolated transcription initiation-negative missense mutants in the cytoplasmic region of FecR that were located at four sites, L13Q, W19R, W39R, and W50R, which are highly conserved in FecR-like open reading frames of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Pseudomonas putida, Bordetella pertussis, Bordetella bronchiseptica, and Caulobacter crescentus genomes. The cytoplasmic portion of the FecR mutant proteins, FecR1–85, did not interact with wild-type FecI, in contrast to wild-type FecR1–85, which induced FecI-mediated fecB transport gene transcription. Two missense mutations in region 2.1 of FecI, S15A and H20E, partially restored induction of ferric citrate transport gene induction of the fecR mutants by ferric citrate. Region 2.1 of ς70 is thought to bind RNA polymerase core enzyme; the residual activity of mutated FecI in the absence of FecR, however, was not higher than that of wild-type FecI. In addition, missense mutations in the fecI promoter region resulted in a twofold increased transcription in fecR wild-type cells and a partial restoration of fec transport gene transcription in the fecR mutants. The mutations reduced binding of the Fe2+ Fur repressor and as a consequence enhanced fecI transcription. The data reveal properties of the FecI ECF factor distinct from those of ς70 and further support the novel transcription initiation model in which the cytoplasmic portion of FecR is important for FecI activity.

Citrate does not serve as a carbon source for Escherichia coli K-12 since it is not taken up by the cells; however, Fe3+ delivered as a citrate complex is actively transported by the FecA protein across the outer membrane (46) and by the FecBCDE proteins (ATP binding cassette transporter) across the cytoplasmic membrane (33, 40). Transport studies using radiolabeled [55Fe3+][14C]citrate revealed uptake of iron and only minimal amounts of citrate, indicating that only iron and not the iron complex enters the cytoplasm (21). Yet ferric citrate induces transcription of ferric siderophore transport genes and is the only ferric siderophore of E. coli K-12 known to do so (46). Intracellular ferric citrate does not serve as an inducer, and fecBCDE mutants impaired in the transport of iron across the cytoplasmic membrane are fully inducible (51).

The question arose as to how the inducer initiates transcription of transport genes in the cytoplasm when only iron and not citrate enters the cytoplasm. Mutants in the fecA, tonB, exbB, or exbD gene (the latter two in combination with tolQ or tolR mutations) are devoid of ferric citrate transport across the outer membrane and are not inducible (51). The obvious conclusion that entry of ferric citrate into the periplasm is required for induction has been ruled out by supplying to a fecA null mutant growth-promoting concentrations of ferric dicitrate (molecular mass, 434 Da) that enter the periplasm by diffusion through the porins. No induction of fec transport genes is observed (19), and the transport genes encoding cytoplasmic membrane transport activities have to be constitutively overexpressed from a multicopy plasmid to provide sufficient amounts of transport proteins.

A direct involvement of FecA in induction has been shown with fecA missense mutants that induce fec transcription constitutively in the absence of ferric citrate (19) but do not transport ferric citrate. In contrast to other E. coli ferric siderophore receptors, the mature FecA protein contains an N-terminal extension. When a portion of the extra peptide (residues 14 to 68) is removed by genetic means, induction is abolished, but FecA fully retains transport activity. An overexpressed N-terminal FecA1–67 fragment inhibits induction but not transport (22). This proves that the N terminus of mature FecA specifically participates in signal transduction but is dispensable for transport.

The N-proximal portion of mature FecA is located in the periplasm (22) and most likely interacts with the FecR regulatory protein; residues 101 to 317 of FecR were localized to the periplasm, residues 86 to 100 were localized to the cytoplasmic membrane, and residues 1 to 85 were localized to the cytoplasm (31, 47). The transmembrane topology of FecR suggests that it transmits the signal, elicited by binding of ferric citrate to FecA, across the cytoplasmic membrane into the cytoplasm. FecR does not directly act on the promoter upstream of the fecA gene that regulates transcription of fecA and of the fecBCDE genes downstream of fecA (2). Rather, FecR is required for the activity of the FecI sigma factor, which belongs to extracytoplasmic-function (ECF) sigma factors (28). No other ECF regulatory system has been studied with respect to the entire sequence of events, chemical entity of the signal, signal recognition, signal transmission, and signal response, to the same extent as the ferric citrate regulation system. Purified FecI mediates specific binding of the RNA polymerase core enzyme to the promoter region upstream of fecA, as revealed by DNA mobility band shift experiments, and promotes fecA transcription in vitro (2). fecA and fecBCDE mRNA formation is dependent on FecI under iron-limiting conditions in the presence of ferric citrate, as shown by Northern hybridization studies (12).

Interaction between the FecA, FecR, and FecI regulatory proteins has been demonstrated using two methods. In in vitro binding assays, FecA retained by FecR His tagged at the N terminus (His10-FecR) and bound to a Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose column is coeluted with His10-FecR; FecI retained by FecR His tagged at the C terminus (FecR-His6) bound to the column and is coeluted with FecR-His6 from the column. An N-terminally truncated, induction-negative but transport-active FecA protein does not bind to His10-FecR. In an in vivo assay, the FecA-, FecR-, and FecI-interacting regions have been determined using the bacterial two-hybrid Lex-based system. FecA1–79 interacts with FecR101–317, and FecR1–85 interacts with FecI1–173 (13).

The regulatory fecIR genes and the fecABCDE transport genes form separate transcripts (12). Transcription of fecIR is repressed by iron and the Fur protein but is unaffected by ferric citrate, while fecABCDE transcription is regulated by iron and Fur and by ferric citrate via FecI and FecR (3, 12). FecI and FecR regulate fec transport genes transcription, but they display no autoregulation (32). The iron transport genes are regulated by the internal iron concentration and by external ferric citrate. This is a very economical way of using ferric citrate as an iron source. When iron is not needed or when ferric citrate is not present, the transport system is almost totally shut off by cytoplasmic iron. When the iron concentration in the cytoplasm falls below a certain limit, the fecIR genes are transcribed. To turn on the ferric citrate transport system, the carrier has to be in the culture medium. In addition to regulatory functions, the FecA, FecR, and FecI proteins also have vectorial activities in that they transmit information through three cell compartments. Binding of ferric citrate to FecA induces a signal that is transferred from the cell surface into the periplasm and across the cytoplasmic membrane into the cytoplasm. It is thought that the information flux involves coupled conformational changes of FecA and FecR.

In this paper, we report further investigation of the unusual mechanism of transcription initiation mediated by FecA, FecI, and FecR. Induction-inactive missense mutants in the cytoplasmic portion of FecR and missense mutants in FecI which restore FecR-dependent FecI transcription initiation were isolated. The suppressing mutations obtained in FecI were located close to each other in region 2.1 of FecI. In addition, we isolated mutations in the fecI promoter which upregulated fecI transcription because they displayed a reduced binding of the Fe2+ Fur repressor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media.

The E. coli strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Cells were grown in tryptone-yeast extract (TY) or nutrient broth (NB) as described previously (2). The antibiotics ampicillin (50 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (40 μg/ml), and tetracycline (12 μg/ml) were added to media as required.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| H1717 | fhuF::λplacMu aroB araD139 ΔlacU169 rpsL150 relA1 flbB5301 deoC1 ptsF25 rbsR | 41 |

| DH5α | endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 thi1 recA1 gyrA relA1 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 φ80 ΔlacZM15 | 18 |

| ZI418 | fecB::Mud1 (Ap lac) aroB araD139 ΔlacU169 rpsL150 relA1 flbB5301 deoC1 ptsF25 rbsR thi | 45 |

| MO704 | fecB::Mud1 (Ap lac)fecI::Kanr ′fecR aroB araD139 ΔlacU169 rpsL150 relA1 flbB5301 deoC1 ptsF25 rbsR thi | 45 |

| AA93 | Δfec aroB araD139 ΔlacU169 rpsL150 relA1 flbB5301 deoC1 ptsF25 rbsR thi | 31 |

| SU202 | lexA71::Tn5 sulA211 sulA::lacZ Δ(lacIPOZYA)169/F′lacIqlacZΔM15::Tn9 | 9 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMLB1034 | ori ColE1 Ampr contains promoterless lacZ | 39 |

| pMMO1034 | pMLB1034 fecA-lacZ fusion | 31 |

| pHSG576 | pSC101 derivative Cmr | 43 |

| pMMO202 | pHSG576 NdeI/BglI cleavage sites removed | This study |

| pKW135 | pHSG576 fecI fecR | 50 |

| pMMO203 | pMMO202 fecI fecR | This study |

| pMMO222 | pMMO202 fecI fecR(T1865A)(W39R) | This study |

| pMMO247 | pMMO202 fecI fecR(T1788A)(L13Q) | This study |

| pMMO252 | pMMO202 fecI fecR(T1805A)(W19R) | This study |

| pMMO277 | pMMO202 fecI fecR(T1898C)(W50R) | This study |

| pPTS222 | pMMO202 fecI fecR(T1865A/G1866A)(W39R) | This study |

| pPTS247 | pMMO202 fecI fecR(T1788A/G1789A)(L13Q) | This study |

| pPTS252 | pMMO202 fecI fecR(T1805A/G1807A)(W19R) | This study |

| pPTS277 | pMMO202 fecI fecR(T1898C/G1900C)(W50R) | This study |

| pASc1 | pMMO202 fecI(A1120G fecRT1805A/G1807A)(W19R) | This study |

| pASc2 | pMMO202 fecI(A1174T/A1211G fecRT1865A/G1866A)(W39R) | This study |

| pASc3 | pMMO202 fecI(A1180G fecRT1788A/G1789A)(L13Q) | This study |

| pASc11 | pMMO203 fecI(A1120G) fecR | This study |

| pASc12 | pMMO203 fecI(A1174T/A1211G) fecR | This study |

| pASc13 | pMMO203 fecI(A1180G) fecR | This study |

| pFPV25 | ori ColE1 Ampr contains promoterless gfpmut3 | 44 |

| pGFPI | pFPV PfecI-gfp fusion | This study |

| pGFP1 | pFPV PfecI(A1120G)-gfp fusion | This study |

| pGFP2 | pFPV PfecI(A1174T/A1211G)-gfp fusion | This study |

| pGFP3 | pFPV PfecI(A1180G)-gfp fusion | This study |

| pAS202 | pMMO202 AseI cleavage site removed | This study |

| pAS203 | pAS202 fecI fecR | This study |

| pAS222 | pAS202 fecI fecR(T1865A/G1866A)(W39R) | This study |

| pAS247 | pAS202 fecI fecR(T1788A/G1789A)(L13Q) | This study |

| pAS252 | pAS202 fecI fecR(T1805A/G1807A)(W19R) | This study |

| pAS277 | pAS202 fecI fecR(T1898C/G1900C)(W50R) | This study |

| pAS321 | pAS202 fecI(A1266T/T1275G)(S15A/T12S) fecR(T1788A/G1789A)(L13Q) | This study |

| pAS312 | pAS202 fecI(C1246G/T1275G)(S15A/A5G) fecR(T1865A/G1866A)(W39R) | This study |

| pAS323 | pAS202 fecI(T1275G)(S15A) fecR(T1788A/G1789A)(L13Q) | This study |

| pAS344 | pAS202 fecI(T1274G/C1295A)(H20E) fecR(T1898C/G1900C)(W50R) | This study |

| pMS604 | ori ColE1 TetrlexA1–87-fos zipper | 9 |

| pSM173 | pMS604 lexA1–87-fecI1–173 | 13 |

| pSM1732 | pMS604 lexA1–87-fecI1–173(T1274G/C1295A)(H20E) | This study |

| pSM1731 | pMS604 lexA1–87-fecI1–173(T1275G)(S15A) | This study |

| pDP804 | ori p15A AmprlexA1–87408-jun zipper | 9 |

| pSM85 | pDP804 lexA1–87408-fecR1–85WT | 13 |

| pSM8539 | pDP804 lexA1–87408-fecR1–85(T1865A/G1866A)(W39R) | This study |

| pSM8550 | pDP804 lexA1–87408-fecR1–85(T1898C/G1900C)(W50R) | This study |

| pT7-7 | ori ColE1 phage T7 gene promoter | 42 |

| pIS711 | pT7-7 fecA | 22 |

| pLCIRA | pAS202 fecI fecR fecA | This study |

| pSM10 | pAS202 fecI fecR1–85fecA | This study |

| pSM11 | pAS202 fecI fecR1–85(T1865A/G1866A)(W39R) fecA | This study |

| pSM12 | pAS202 fecI fecR1–85(T1898C/G1900C)(W50R) fecA | This study |

| pSM13 | pAS202 fecI(T1275G)(S15A)fecR1–85fecA | This study |

| pSM14 | pAS202 fecI(T1275G)(S15A) fecR1–85(T1865A/G1866A)(W39R) fecA | This study |

| pSM15 | pAS202 fecI(T1275G)(S15A) fecR1–85(T1898C/G1900C)(W50R) fecA | This study |

Construction of plasmids.

Plasmid pMMO202 was obtained by removing the cleavage sites for NdeI and BglI in pHSG576. To construct plasmid pMMO203, the BamHI-HindIII fecIR fragment of pKW135 (containing an NdeI restriction site at the start codon of fecR) was cloned into BamHI/HindIII-digested pMMO202.

fecR was randomly mutagenized by PCR using primers FecR1 (5′-CTGGAGTATGGCATATGAATC-3′) and FecIR3. The mutated fecR fragments were cloned into pMMO203, restricted with NdeI and BglI to replace the N-terminal 69 amino acids of wild-type FecR, resulting in plasmids pMMO222, pMMO247, pMMO252, and pMMO277. Site-directed mutagenesis of these plasmids by PCR was performed to introduce double nucleotide replacements using primers PTS222B (5′-CGCTGGCAACAGAAGTATGAACAGGATCAGG-3′), PTS47A (5′-AGCTGAACGTTGCGCTCGACGGCGGG-3′), PTS52A (5′-CACGGCATATCTGTGGGAAGCTG-3′), and PTS277B (5′-GATAACCAGTGGGCCCGCCAGCAGGTTGAAAACC-3′), yielding plasmids pPTS222, pPTS247, pPTS252, and pPTS277 respectively.

fecI was randomly mutagenized by PCR using primers SVP1 (5′-CCGACACATGCCAGAAGCAGAGGATCCATCCC-3′) and FecIR3. The resulting fecIR fragments were cleaved with BamHI/NdeI and cloned into the BamHI/NdeI-restricted mutant fecR plasmids pPTS222, pPTS247, pPTS252, and pPTS277. To obtain plasmids pASc1, pASc2, and pASc3, the mutated fecI fragments were cloned into BamHI/NdeI-cleaved pPTS252, pPTS222, and pPTS247, respectively. Plasmids pASc11, pASc12, and pASc13 were constructed by replacing the mutated fecR fragments in pASc1, pASc2, and pASc3 with wild-type fecR.

Wild-type and mutated fecI promoter regions were amplified by PCR using primers PromIEco (5′-GCGAATTCCCATCCCATTTTATACCTACC-3′) and PromIBam (5′-CGGGATCCGGAGTGCATCAAAAGTTAATTATC-3′). To construct plasmids pGFPI, pGFPI1, pGFPI2, and pGFPI3, the resulting PCR fragments were digested with EcoRI/BamHI and cloned into EcoRI/BamHI-restricted pFPV25.

To avoid mutations in the fecI promoter region, the mutated fecIR fragments were restricted with AseI and NdeI and ligated into the AseI/NdeI-cleaved mutant fecR plasmids pAS222, pAS247, pAS252, and pAS277, resulting in plasmids pAS321, pAS312, pAS323, and pAS344, respectively. Plasmid pAS202 was obtained by removing the cleavage site for AseI in pMMO202. To construct plasmid pAS203, the BamHI-HindIII fecIR fragment of pKW135 was cloned into BamHI/HindIII-digested pAS202. For construction of plasmids pAS222, pAS247, pAS252, and pAS277, the NdeI-HindIII fecR fragments of pPTS222, pPTS247, pPTS252, and pPTS277 were ligated into NdeI/HindIII-cleaved pAS203.

To replace the fos zipper motif of plasmid pMS604, plasmids pAS203, pAS312, pAS323, and pAS344 were amplified by PCR with primers FecIBstEII (5′-GATCGAGGTGACCATGTCTGACCGCGCC-3′) and FecIPst (5′-GGTTAACACTGCAGTCATAACCCATACTC-3′). The resulting fragments were cloned into BstEII/PstI- or BstEII/XhoI-cleaved pMS604, resulting in plasmids pSM173, pSM1731, and pSM1732 or plasmids pSM852, pSM853, and pSM854.

Plasmids pSM85, pSM8539, and pSM8550 were constructed by PCR amplification using primers FecRXhoI (5′-GGAAGTCTCGAGATGAATCCTTTGTTAACC-3′) and FecRBglII (5′-CAACAGAATCTTCATTTCATCACACGTGACG-3′) and plasmids pAS203, pAS222, and pAS277 as DNA templates. To replace the jun zipper motif of plasmid pDP804, the resulting XhoI/BglII fecR1–58 and mutated fecR1–58 fragments were ligated into XhoI/BglII-digested pDP804.

For construction of plasmid pLCIRA, the EcoRI-BamHI fecA fragment of pIS711 was ligated into EcoRI/BamHI-cleaved pAS203. Plasmids pSM10, pSM11, and pSM12 were constructed by PCR using primers FecR1 and FecR85HindIII (5′-GAGCAAAAGCTTTAATCATTTCATCACGTGACG-3′) with the DNA templates pAS203, pAS222, and pAS277, respectively. The resulting NdeI-HindIII fecR1–58 fragments were ligated into NdeI/HindIII-cleaved pLCIRA. To obtain plasmids pSM13, pSM14, and pSM15, the mutated BamHI/NdeI fecI fragment of plasmid pAS323 was cloned into BamHI/HindIII-digested pSM10, pSM11, and pSM12, respectively.

Recombinant DNA techniques.

Standard techniques (34) or the protocols of the suppliers were used for the isolation of plasmid DNA, PCR, digestion with restriction endonucleases, ligation, transformation, and agarose gel electrophoresis. DNA was sequenced by the dideoxy chain termination method (35) using an AutoRead Sequencing kit (Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany). The reaction products were sequenced on an A.L.F. DNA sequencer (Pharmacia Biotech).

PCR techniques.

PCR amplification was carried out using Taq polymerase (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and standard conditions. DNA was initially denatured by heating to 94°C for 3 min. This was followed by 30 cycles consisting of denaturing at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 54°C for 2 min, and extension at 72°C for 3 min. Random mutagenesis by PCR was carried out as previously described (26). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed according to Feinberg et al. (14).

Determination of β-galactosidase activity.

β-Galactosidase activity was determined according to Miller (30) and Giacomini et al. (16). For measurement of induction activity, the cells were grown in NB medium without additions or supplemented as indicated with 0.2 mM 2,2′-dipyridyl or 1 mM citrate. For the LexA-based repression system, the cells were grown in TY medium supplemented with 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside).

GFP measurements.

Cells were grown in TY or NB medium as indicated. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) was quantified by fluorometry in an Bio-Tek FL500 microplate fluorescence reader (Bio-Tek Instruments Inc., Winooski, Vt.). Specific activity of GFP in bacterial cultures was expressed as relative fluorescence intensity at 530 nm of cells adjusted to an optical density at 578 nm of 0.5 in phosphate-buffered saline (44).

Similarity searching and sequence alignments.

A global similarity search of the current National Center for Biotechnology Information nucleic acid databases with the advanced BLAST search and the specialized BLAST search of finished and unfinished microbial genomes was used to look for amino acid sequences homologous to the FecR sequence. Preliminary sequence data for Bordetella pertussis and Bordetella bronchiseptica were obtained from The Institute for Genomic Research website at http://www.tigr.org. Sequence data for Pseudomonas putida and Caulobacter crescentus were from the Sanger Center and can be obtained from ftp://ftp.sanger.ac.uk/pub/yyy. Sequences of Pseudomonas aeruginosa were obtained from the Pseudomonas Genome Project at http://www.pseudomonas.com/data.html. The sequences of E. coli FecR (M63115), P. aeruginosa HasR (AF127223) and PigE (AF060193), and P. putida PupR (X77918) were translated from the GenBank entries given in parentheses. Protein sequences were aligned by using CLUSTAL W.

RESULTS

Isolation of induction-negative fecR mutations.

To identify functionally important residues of FecR and to determine regions of interaction between FecR and FecI, we isolated inactive fecR point mutants and examined restoration of transcription initiation of the fec transport genes by fecI point mutants. fecR was mutagenized by PCR, and the fragments encoding residues 1 to 69 of FecR were cloned into the low-copy-number plasmid pMMO203 fecIR to replace residues 1 to 69 of wild-type FecR. E. coli MO704 fecI::Kan ′fecR fecB-lacZ was used to select fecR mutants. Insertion of the kanamycin resistance box resulted in the deletion of the 3′ end of fecI and the 5′ end of fecR (32). Transformants with the mutagenized pMMO203 plasmids were screened on MacConkey agar plates containing 1 mM citrate, which forms ferric citrate with iron contained in the nutrient agar. Under these conditions, fecB-lacZ transcription is induced by wild-type fecIR, and red colonies are formed; mutated fecIR does not induce fecB-lacZ transcription, and white and pink colonies are formed. The fecR genes of plasmids from white and pink colonies were sequenced; four missense mutations with a leucine-to-glutamine change at position 13 and three different tryptophan-to-arginine changes at residues 19, 39, and 50 were identified (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

fecB-lacZ transcription in fecR mutants

| Plasmid | Mutation | Amino acid substitution | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units)a

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NB medium | NB medium + citrate | |||

| pMMO203 | None | None | 27 | 943 |

| pMMO247 | T1788A | L13Q | 19 | 59 |

| pMMO252 | T1805A | W19R | 15 | 54 |

| pMMO222 | T1865A | W39R | 20 | 64 |

| pMMO277 | T1898A | W50R | 18 | 59 |

Determined in E. coli MO704 fecI::Kan fecB-lacZ transformed with plasmids carrying wild-type fecI and mutated fecR.

β-Galactosidase activity of E. coli MO704 cells transformed with the pMMO203 fecR mutant derivatives and grown in NB medium with and without citrate supplementation was determined to verify the results obtained on the MacConkey plates. All four mutants with point mutations in fecR displayed very low ferric citrate-dependent fecB-lacZ transcription compared to the 35-fold increase of the wild-type fecR+ strain in the presence of citrate (Table 2). The threefold increased activity of the fecR mutants in the presence of citrate may result from iron starvation, which derepresses fecIR and fecABCDE transcription, caused by the lack of citrate-mediated iron uptake of the fecB-lacZ transport mutant. The increased levels of mutant FecR and wild-type FecI could enhance the residual functional interaction between the proteins. Synthesis of the mutant FecR proteins was confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis after overexpression in an IPTG-inducible T7 promoter system (data not shown). Since the fecR point mutants reverted to wild type in the subsequent suppression analysis with fecI mutants, a second nucleotide replacement was introduced into the mutated fecR codons (Table 1).

Mutations in the fecI coding region that restore transcription initiation by the fecR mutants.

To determine sites of FecI that might interact with FecR, fecI mutations that suppress the fecR missense point mutations were isolated. To prevent mutations in the fecI promoter region, fecI lacking the promoter region was randomly mutagenized by PCR, and the DNA fragments were inserted into the pMMO203 fecIR derivatives encoding the fecR mutants with two mutations in one codon. Red colonies of E. coli MO704 transformants were screened on MacConkey plates, plasmids were isolated, and the fecI regions were sequenced. Four mutants were identified (Fig. 1B). Three of the four mutants showed a serine-to-alanine change at position 15 (S15A); one was a single mutation, one contained an additional alanine-to-glycine change (A5G), and one contained an additional threonine-to-serine change (T12S) (Table 3). These differences showed that all three S15A mutations resulted from independent events. All three mutants had similar citrate-dependent β-galactosidase activities, 21 to 28% of wild-type activity (Table 3), which suggests that the S15A mutation causes the partial restoration of transcription initiation (regarding A5G, see Discussion). In comparison to the β-galactosidase values of cells with wild-type fecI (Table 2), the fecI mutants displayed a three- to fivefold-higher citrate-dependent activity. The fourth mutant, with a single histidine-to-glutamic acid change at position 20, had β-galactosidase activity twofold higher than that of FecR(W50R) combined with wild-type FecI.

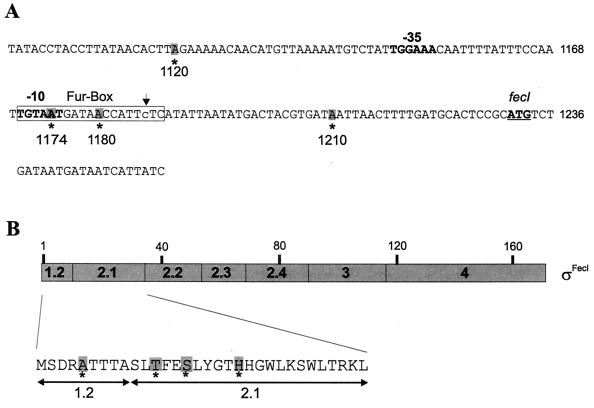

FIG. 1.

(A) Promoter sequence upstream of the fecI fecR operon. Positions of mutations are indicated by asterisks, positions of −35 and −10 promoter regions are illustrated in bold letters, and the transcription start point is indicated by an arrow. The consensus sequence of the Fur box is illustrated below. (B) Schematic map of ςFecI illustrating regions homologous to ς70. The sites of amino acid substitutions are indicated below ςFecI.

TABLE 3.

fecB-lacZ transcription of fecI fecR mutants

| Plasmid | fecI mutation | Amino acid substitution in:

|

β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FecI | FecR | NB medium | NB medium + citrate | ||

| pMMO203 | None | None | None | 27 | 943 |

| pAS301 | A1266T | S15A | L13Q | 8 | 254 |

| T1275G | T12S | ||||

| pAS302 | C1246G | S15A | W39R | 11 | 201 |

| T1275G | A5G | ||||

| pAS303 | T1275G | S15A | L13Q | 15 | 265 |

| pAS304 | C1295A | H20E | W50R | 40 | 157 |

Determined in E. coli MO704 fecI::Kan fecB-lacZ transformed with plasmids carrying mutated fecI and fecR.

Since the fecI suppressor mutations were observed in combination with distinct fecR point mutations, we tested allele specificity. Each of the four fecI suppressor mutations was combined with each of the four fecR mutant genes in E. coli MO704. The β-galactosidase activities of the FecI derivatives with each of the FecR mutants were similar, 244 ± 10 U for FecI(S15A, T12S), 198 ± 6 U for FecI(S15A, A5G), 267 ± 7 U for FecI(S15A), and 159 ± 6 U for FecI(H20E), which indicated no allele specificity.

FecI(S15A), FecI(S15A, W12S), and FecI(H20E) are located close together in region 2.1 of the sigma factor; this region in ς70 is implicated in RNA polymerase core binding (25, 38). Therefore, the missense mutations in fecI could have increased the affinity of FecI to the RNA polymerase core enzyme, resulting in a higher level of fec transport gene transcription. To examine this possibility, the fecI suppressor mutations were combined with the wild-type fecR gene. The β-galactosidase activities measured were similar to those of wild-type fecIR, on average 18 U in NB medium and 797 U in NB medium supplemented with citrate. In addition, the β-galactosidase activities of the FecI mutants in the absence of FecR were measured; the activities were lower than those of wild-type FecI (8 to 10 U and 20 U, respectively). These results provide no evidence that the S15A and H20E mutations alter the interaction of FecI with the RNA polymerase core enzyme or increase the amount of active FecI.

In vivo interaction of the FecI suppressor mutants with mutated FecR.

We have recently shown that FecI interacts with the cytoplasmic N terminus of FecR (FecR1–85) by using a bacterial two-hybrid system (13). To determine the physical interactions between the mutants of FecI and FecR, translational fusions were constructed between LexA1–87408, which binds to one site of the sulA promoter (9), and the wild-type FecR1–85 (FecR1–85WT) derivatives, and between LexA1–87, which binds to another site of the sulA promoter, and the FecI derivatives (Table 4). FecR1–85 had to be used because it represents the cytoplasmic portion of FecR. Mutated FecR1–85 combined with mutated FecI or wild-type FecI did not repress sulA-lacZ transcription, indicating that the mutated FecR1–85 fragments did not interact with FecI. This could explain inactivity of the mutated FecR proteins. In contrast, FecR1–85WT combined with mutated or wild-type FecI repressed sulA-lacZ transcription (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Binding of the cytoplasmic region of wild-type FecR and mutated FecR to wild-type FecI and mutated FecI

| Protein combination | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units)a | Protein interaction |

|---|---|---|

| LexA1–87WT-Fos zipper and LexA1–87408-Jun zipper | 16 | + |

| LexA1–87WT-Fos zipper and LexA1–87408-FecR1–85WT | 246 | − |

| LexA1–87408-Jun zipper and LexA1–87WT-FecI | 253 | − |

| LexA1–87408-FecR1–85WT and LexA1–87WT-FecI | 42 | + |

| LexA1–87408-FecR(W39R)1–85 and LexA1–87WT-FecI | 241 | − |

| LexA1–87408-FecR(W50R)1–85 and LexA1–87WT-FecI | 221 | − |

| LexA1–87408-FecR1–85WT and LexA1–87WT-FecI(S15A) | 44 | + |

| LexA1–87408-FecR1–85WT and LexA1–87WT-FecI(H20E) | 32 | + |

| LexA1–87408-FecR(W39R)1–85 and LexA1–87WT-FecI(S15A) | 251 | − |

| LexA1–87408-FecR(W39R)1–85 and LexA1–87WT-FecI(H20E) | 231 | − |

| LexA1–87408-FecR(W50R)1–85 and LexA1–87WT-FecI(S15A) | 236 | − |

| LexA1–87408-FecR(W50R)1–85 and LexA1–87WT-FecI(H20E) | 247 | − |

Determined by the bacterial two-hybrid LexA-based system in E. coli SU202 sulA-lacZ.

Since the complete FecR and FecR mutant proteins combined with the FccJ mutant proteins induced transcription of fecB-lacZ, the induction of transcription of the truncated FecR1–85 and mutant FecR1–85 proteins was studied. β-Galactosidase activities were determined in E. coli AA93 Δfec/pMMO1034 fecA-lacZ transformed with low-copy-number plasmids encoding fecA and the fecR1–85 and fecI derivatives (Table 5). No transcription induction was recorded with the FecR1–85 mutant proteins. These results agree with the lack of interaction of the truncated FecR mutant proteins in the bacterial two-hybrid system. In the control, FecR1–85WT combined with wild-type or mutated FecI displayed constitutive fecA-lacZ transport gene transcription, as found previously for the wild-type combination (31).

TABLE 5.

Induction of fecA-lacZ transcription by cytoplasmic FecR derivatives combined with wild-type and mutant FecI

| Plasmid | Encoded Fec protein(s)a | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units)b

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| NB medium + 50 μM dipyridyl | NB medium + 1 mM citrate | ||

| pHSG576 | None | 8 | 6 |

| pLCIRA | IRA | 54 | 219 |

| pSM10 | IR1–85A | 312 | 264 |

| pSM11 | IR1–85(W39R)A | 16 | 14 |

| pSM12 | IR1–85(W50R)A | 13 | 12 |

| pSM13 | I(S15A)R1–85A | 435 | 469 |

| pSM14 | I(S15A)R1–85(W39R)A | 9 | 9 |

| pSM15 | I(S15A)R1–85(W50R)A | 7 | 7 |

I, R, and A denote the FecI, FecR, and FecA proteins.

Determined in E. coli AA93 Δfec carrying pMMO1034 fecA-lacZ and the listed plasmids.

fecI promoter mutants that restore induction of the fecR mutants.

Originally we randomly mutagenized complete fecI by PCR. E. coli MO704 carrying one of the fecR mutant genes (Table 2) was transformed with the pooled fecI plasmids, and red colonies were isolated on MacConkey agar plates supplemented with 1 mM citrate. They displayed β-galactosidase activities two- to threefold higher (Table 6) than the values obtained with wild-type FecI (Table 2), which indicated a citrate-independent transcription initiation by the mutated fecI region. An additional two- to threefold increase was recorded in the presence of 1 mM citrate in the growth medium; this increase could be caused by iron limitation and ferric citrate induction.

TABLE 6.

fecB-lacZ transcription in fecI promoter mutants combined with fecR mutations or wild-type fecR

| Plasmid | fecI promoter mutation | Amino acid substitution in FecR | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units)a

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NB medium | NB medium + citrate | |||

| pMMO203 | None | None | 27 | 943 |

| pASc1 | A1120G | W19R | 42 | 112 |

| pASc2 | A1174T | W39R | 68 | 135 |

| A1210G | ||||

| pASc3 | A1180G | L13Q | 105 | 150 |

| pASc11 | A1120G | None | 330 | 1471 |

| pASc12 | A1174T | None | 782 | 2,291 |

| A1210G | ||||

| pASc13 | A1180G | None | 1,141 | 2,286 |

Determined in E. coli MO704 fecI::Kan fecB-lacZ transformed with plasmids carrying mutated promoter fecI and mutated or wild-type fecR.

Sequencing of the mutated fecI regions revealed nucleotide replacements upstream of the fecI open reading frame (Table 6). The A1120G replacement is located 28 bp upstream of the postulated −35 region; A1174T is in the −10 region and together with A1180G rests in the predicted Fur box to which the Fe2+ Fur repressor binds under iron-replete conditions (Fig. 1A). A1210G is located 24 bp downstream of the transcription start site. The fecI promoter mutants combined with wild-type fecR displayed in the absence of ferric citrate 12-, 29-, and 42-fold, and in the presence of ferric citrate 1.6-, 2.4-, and 2.4-fold, increases in fecB-lacZ transcription (Table 6).

Constitutive transcription by the fecI promoter mutants was also determined in E. coli AA93 Δfec grown in NB medium with and without addition of 1 mM citrate. Since the Δfec strain cannot take up ferric citrate, addition of citrate results in trapping of iron, making it unavailable to cells. Ferric citrate cannot act as an inducer since the cells lack FecA and FecR. Transcription initiation controlled by the mutated fecI promoter regions was examined by inserting the promoter regions upstream of a promoterless gfp gene. Two of the promoter mutants, A1174T, A1210G, and A1180G, displayed a two- to threefold increase in fluorescence relative to that of the strain carrying nonmutated fecI, whereas the A1120G mutation increased transcription only slightly (Table 7). In the latter mutant, iron starvation by addition of citrate increased transcription 2.4-fold, whereas the already strongly induced mutants showed only 1.2- and 1.6-fold enhancements of transcription.

TABLE 7.

fecI-gfp transcription of fecI promoter and fecR mutants

| Plasmid | fecI promoter mutation | Relative fluorescencea

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| NB medium | NB medium + citrate | ||

| pGFPI | None | 416 | 946 |

| pGFPI1 | A1120G | 461 | 1,098 |

| pGFPI2 | A1174T | 773 | 1,220 |

| A1210G | |||

| pGFPI3 | A1180G | 1,163 | 1,408 |

Determined in E. coli AA93 Δfec transformed with plasmids carrying mutated fecI promoter and promoterless gfp.

To demonstrate differences in Fe2+ Fur repressor binding to the mutants as the cause of their distinct induction levels, Fe2+ Fur repressor binding to fecI wild-type and fecI mutant promoters was examined in a Fur titration assay using E. coli H1717 fhuF-lacZ; transcription of fhuF is particularly sensitive to the level of the iron supply (41). TY medium, which provides sufficient iron to cells, was used to eliminate experimentally imposed iron limitation. As shown in Table 8, the promoters of fecI(A1174T, A1210G) and fecI(A1180G) bound less Fe2+ Fur than the fecI(A1120G) and wild-type fecI promoters, resulting in an increased concentration of free Fe2+ Fur, which could then bind to the fhuF promoter and repress fhuF-lacZ transcription. Since also fecR transcription is controlled by the promoter upstream of fecI, an increase of one or both proteins resulted in the suppression phenotype. It is conceivable that residual activities of the mutated FecR proteins together with an increased level of FecI suffice to initiate transcription of the fec transport genes. The titration results do not explain the slight increase of fecI transcription by the A1120G mutation.

TABLE 8.

Fe2+ Fur titration with fecI promoter mutants

| Plasmid | fecI promoter mutation | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units)a | Fe2+ Fur binding |

|---|---|---|---|

| pFPV25 | Vector | 78 | − |

| pGFPI | None | 253 | + |

| pGFPI1 | A1120G | 258 | + |

| pGFPI2 | A1174T | 104 | − |

| A1210G | |||

| pGFPI3 | A1180G | 96 | − |

Determined in E. coli H1717 fhuF-lacZ transformed with plasmids carrying mutated promoter fecI and promoterless gfp.

DISCUSSION

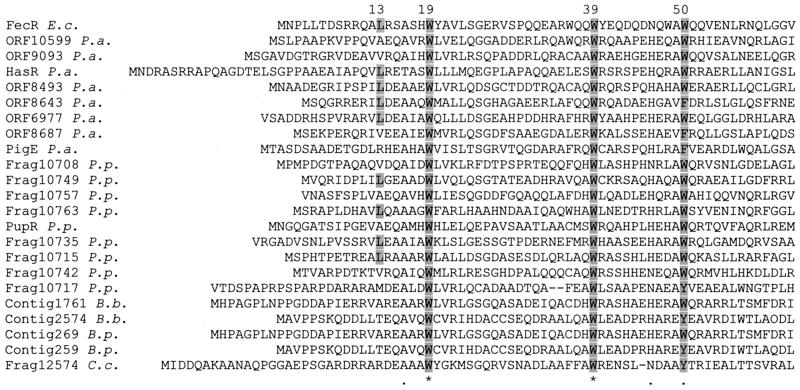

Since no transcription initiation mechanism that starts at the cell surface and requires a cytoplasmic membrane protein for induction has been characterized to date, we further investigated our proposed model by examination of FecR missense mutants. Point mutants with amino acid replacements in the cytoplasmic portion of FecR were isolated and failed to induce transcription of fecB-lacZ. The mutations L13Q, W19R, W39R, and W50R are located in the region from residues 9 to 49, which was previously shown to interact with FecI (13). Database searches of complete and incomplete sequenced bacterial genomes revealed genes homologous to the fec regulatory genes fecI and fecR in P. aeruginosa, P. putida, B. bronchiseptica, B. pertussis, and C. crescentus (Fig. 2). Of 23 complete and partial FecR homologous sequences available, all contained W19, W39, and W50 with the exception of three F and four Y replacement in W50. Since the replacements conserved the aromatic nature of the amino acids, it is conceivable that aromatic amino acids are essential at these sites. Random mutagenesis used in this study clearly identified these highly conserved amino acid residues as important for FecR activity. L13 is less conserved and is replaced mostly by apolar amino acids but in two sequences also by charged arginine. The sequences align perfectly with FecR with two exceptions where sequence gaps of only one and two amino acids, respectively, had to be introduced. The identity between E. coli K-12 FecR and the putative FecR sequences range from 24 to 37%, with an average identity of 30%. In the various genomes, fecI and fecR are arranged as in E. coli and are presumably transcriptionally coupled. Furthermore, downstream of the regulatory genes are sequences that show similarity to ECF sigma factor-dependent promoters. Only the PupI-PupR system of P. putida has been studied to the extent that the outer membrane transporter, PupI, and PupR were shown to be required for induction (23). In the absence of inducer, PupR seems to repress synthesis of the outer membrane transporter, as one would expect from an anti-sigma factor and in agreement with other ECF sigma factor systems in which the regulator functions negatively as an anti-sigma factor. No evidence exists for a negative FecR function in the fec system. For the homologous genes other than pup, it is not known whether sequence similarity reflects similar functions and whether the mechanism of fec regulation represents the paradigm of other gene transcription regulatory devices.

FIG. 2.

Alignment of the N termini of E. coli FecR homologs. Similarity search and sequence alignment were done as described in Materials and Methods. E. c., E. coli; P. a., P. aeruginosa; P. p., P. putida; B. b., B. bronchiseptica; B. p., B. pertussis; C. c., C. crescentus. Note the highly conserved tryptophan (W) residues corresponding to positions 19, 39, and 50 of E. coli FecR.

Restoration of transcription induction of the FecR mutants depended on the FecI mutants and ferric citrate in the medium. Wild-type FecI was inactive. We assume that the FecI mutant proteins can be converted to an active sigma factor more easily than wild-type FecI, so that the presumed residual activities of the mutated FecR derivatives are sufficient for FecI activation. The mutant FecR1–85 derivatives were not active, in contrast to FecR1–85WT, which together with FecI initiated fec transport gene transcription in the absence of ferric citrate. This result suggests that FecR1–85 does not entirely reflect the conformation of the cytoplasmic portion of the complete FecR once it has received the signal from FecA occupied by ferric citrate. This interpretation is supported by the lack of interaction of FecR1–85(W39R) and FecR1–85(W50R) with either wild-type FecI, FecI(S15A), or FecI(H20E), as revealed by the two-hybrid system.

The fecI mutations were confined to a narrow region at the FecI N terminus, even though the entire fecI gene was mutagenized by PCR. The S15A mutation was obtained three times and represents a conservative alteration from a polar to an apolar amino acid, both of which require a similar amount of space. The average β-galactosidase activity induced by the FecI S15A mutants amounted to 25% of the activity displayed by wild-type FecI; the mutations increased the fecB-lacZ β-galactosidase activity of the FecR missense mutants three- to fivefold. The FecI H20E mutant was less active; it had 16% of the β-galactosidase activity of the wild-type and a twofold increase in fecB-lacZ β-galactosidase activity of the FecR mutant cells.

Each of the single fecI mutations is located in region 2.1 of FecI. Deletion of subregion 2.1 of ς70 reduces ς70 binding to the RNA polymerase core enzyme (25, 38). The recently determined structure of a large part of ς70 revealed that regions 2.1 and 2.2 form two α-helices at the surface of ς70 that are linked by a loop and interact primarily through hydrophobic contacts (29). We found no evidence for an improved interaction between mutated FecI with RNA polymerase core subunits, which might have explained restoration of induction in the FecR mutants. The FecI mutants did not show higher activity with wild-type FecR and did not display higher residual activity in the absence of FecR.

Since the FecI S15A and H20E mutations are located close to each other and the FecR mutations L13Q, W10R, W39R, and W50R are confined to a short region that may fold such that the side chains are positioned close to each other, it is tempting to assume that these two sites disclose regions of interaction between the two proteins. The lack of allele specificity does not rule out this interpretation since, for example, the sites of interaction between the TonB protein (around residue 160) and the so-called TonB box of the BtuB (17) and FhuA proteins (36), as identified by suppressor analyses, also lack allele specificity, yet recent cysteine cross-linking studies established beyond doubt interaction of the TonB box of BtuB with region 160 of TonB (8). Since no specific side chain recognition was observed, it has been concluded that the mutations distort the secondary structure of the interacting regions and thus impair functional interaction (17). The same conclusion could apply to the FecI-FecR interaction.

The fecI promoter mutations that partially restored induction of fecB gene transcription of the inactive fecR mutants bound less Fe2+ Fur and consequently led to a higher fecI and fecR transcription than in the wild-type fecIR strain under the same conditions. Derepression could still be enhanced by withdrawing iron by addition of citrate or dipyridyl to the medium. The same explanation as given above may account for this finding. Increase of FecI and mutant FecR proteins increases the probability of a functional interaction that leads to induction-active FecI. A comparable situation exists in the case of ςE which is one of the stress response ς factors of E. coli that belongs to the ECF family and is negatively regulated by the transmembrane anti-sigma factor RseA. The activity of ςE is determined by the relative levels of ςE and RseA, and RseA is regulated by controlled proteolysis (1). FecI is positively regulated by FecR, and the amount of active FecI certainly depends on the amounts of active FecR. Activation of FecI does not necessarily imply an alteration in the conformation of FecI or a chemical modification of FecI. Rather, if FecI is synthesized in an active form but rapidly loses activity, stabilization of the active FecI form by active FecR would also account for the data hitherto collected. FecI while bound to FecR would be inactive. When FecR receives the transcription initiation signal from ferric citrate-loaded FecA, it changes the conformation in the cytoplasmic portion, and FecI dissociates from FecR and immediately binds to the RNA polymerase.

The ECF ς factors lack large portions of the conserved region 1 (28), which in ς70 appears to primarily affect DNA binding by region 4. This led to the proposal that binding of the ς factors to the core subunits induces a conformational change that exposes the DNA binding region to allow promoter recognition by the holoenzyme (11). FecI completely lacks region 1.1 and has only nine amino acids in region 1.2. Deletion of residues 2 to 8 did not affect FecI activity (data not shown), and therefore region 1 is not essential for ferric citrate-dependent fec transport gene transcription. This result makes it unlikely that the A5G mutation of pAS302 transformants contributed to the phenotype. This conclusion is supported by our data on SigX of Bacillus subtilis, which completely lacks regions 1.1 and 1.2 and can replace FecI in that it initiates transcription of the fec transport genes in E. coli in the absence of ferric citrate and FecR (6).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. Angerer, U. H. Stroeher, and K. Hantke for helpful discussions and K. A. Brune for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 323, project B1, Graduiertenkolleg Mikrobiologie) and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ades S E, Connolly L E, Alba B A, Gross C A. The Escherichia coli ςE-dependent extracytoplasmic stress response is controlled by the regulated proteolysis of an anti-ς factor. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2449–2461. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.18.2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angerer A, Enz S, Ochs M, Braun V. Transcriptional regulation of ferric citrate transport in Escherichia coli K-12. FecI belongs to a new subfamily of ς70-type factors that respond to extracytoplasmic stimuli. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:163–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18010163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angerer A, Braun V. Iron regulates transcription of the Escherichia coli ferric citrate transport genes directly and through the transcription initiation proteins. Arch Microbiol. 1998;169:483–490. doi: 10.1007/s002030050600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braun V. Surface signaling: novel transcription initiation mechanism starting from the cell surface. Arch Microbiol. 1997;167:325–331. doi: 10.1007/s002030050451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun V, Hantke K, Köster W. Bacterial iron transport: mechanisms, genetics, and regulation. In: Sigel A, Sigel H, editors. Metal ions in biological systems. Vol. 35. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker; 1998. pp. 67–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brutsche S, Braun V. SigX of Bacillus subtilis replaces the ECF sigma factor FecI of Escherichia coli and is inhibited by RsiX. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;256:416–425. doi: 10.1007/s004380050585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchanan S K, Smith B S, Venkatramani L, Xia D, Esser L, Palnitkar M, Chakraborty R, van der Helm D, Deisenhofer J. Crystal structure of the outer membrane active transporter FepA from Escherichia coli. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;6:56–63. doi: 10.1038/4931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cadieux N, Kadner R J. Site-directed disulfide bonding reveals interaction site between energy-coupling protein TonB and BtuB, the outer membrane cobalamin transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10673–10678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dmitrova M, Younes-Cauet G, Oertel-Buchheit P, Porte D, Schnarr M, Granger-Schnarr M. A new LexA-based genetic system for monitoring and analyzing protein heterodimerization in Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1998;257:205–212. doi: 10.1007/s004380050640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dombroski A J, Walter W A, Record M T, Siegele D A, Gross C A. Polypeptides containing highly conserved regions of the transcription initiation factor ς70 exhibit specificity of binding to promoter DNA. Cell. 1992;70:501–512. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90174-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dombroski A J, Walter W A, Gross C A. Amino-terminal amino acids modulate ς-factor DNA-binding activity. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2446–2455. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12a.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Enz S, Braun V, Crosa J. Transcription of the region encoding the ferric dicitrate transport system in Escherichia coli: similarity between promoters for fecA and for extracytoplasmic function sigma factors. Gene. 1995;163:13–18. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00380-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enz S, Mahren S, Stroeher U H, Braun V. Surface signaling in ferric citrate transport gene induction: interaction of the FecA, FecR, and FecI regulatory proteins. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:637–646. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.3.637-646.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feinberg B B, Berman S, Politch J. PCR-Ligation-PCR mutagenesis: a protocol for creating gene fusions and mutations. BioTechniques. 1995;18:746–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferguson A D, Hofmann E, Coulton J W, Diederichs K, Welte W. Siderophore-mediated iron transport: crystal structure of FhuA with bound lipopolysaccharide. Science. 1998;282:2215–2220. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giacomini A, Corich B, Ollero F J, Squartini A, Nuti M P. Experimental conditions may affect reproducibility of the β-galactosidase assay. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;100:87–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb14024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gudmundsdottir A, Bell P E, Lundrigan M D, Bradbeer C, Kadner R J. Point mutations in a conserved region (TonB box) of Escherichia coli outer membrane BtuB affect vitamin B12 transport. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6526–6533. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.12.6526-6533.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanahan D. Studies in transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Härle C, Insook K, Angerer A, Braun V. Signal transfer through three compartments: transcription initiation of the Escherichia coli ferric citrate transport system from the cell surface. EMBO J. 1995;14:1430–1438. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heller K J, Kadner R J, Günther K. Suppression of the btuB451 mutations by mutations in the tonB gene suggests a direct interaction between TonB and TonB-dependent receptor proteins in the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. Gene. 1988;64:147–153. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90488-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hussein S, Hantke K, Braun V. Citrate dependent iron transport system in Escherichia coli K-12. Eur J Biochem. 1981;117:431–4337. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1981.tb06357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim I, Stiefel A, Plantör S, Angerer A, Braun V. Transcription induction of the ferric citrate transport genes via the N-terminus of the FecA outer membrane protein, the Ton system and the electrochemical potential of the cytoplasmic membrane. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:333–344. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2401593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koster M, van Klompenburg W, Bitter W, Leong J, Weisbeek P. Role of the outer membrane ferric siderophore receptor PupB in signal transduction across the bacterial cell envelope. EMBO J. 1994;13:2805–2813. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06574.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lesley S A, Burgess R R. Characterization of the Escherichia coli transcription factor sigma 70: localization of a region involved in the interaction with core RNA polymerase. Biochemistry. 1989;28:7728–7734. doi: 10.1021/bi00445a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leung D W, Chen E, Goeddel D V. A method for random mutagenesis of a defined DNA segment using a modified polymerase chain reaction. Technique. 1989;1:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Locher K P, Rees B, Koebnik R, Mitschler A, Moulinier L, Rosenbusch J P, Moras D. Transmembrane signaling across the ligand-gated FhuA receptor: crystal structures of free and ferrichrome-bound states reveal allosteric changes. Cell. 1998;95:771–778. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81700-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lonetto M A, Brown K L, Rudd K E, Buttner M J. Analysis of the Streptomyces coelicolor sigE gene reveals the existence of a subfamily of eubacterial RNA polymerase ς factors involved in the regulation of extracytoplasmic functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7573–7577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malhotra A, Severinova E, Darst S. Crystal structure of a ς70 subunit fragment from E. coli RNA polymerase. Cell. 1996;87:127–136. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81329-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ochs M, Veitinger S, Kim I, Welz D, Angerer A, Braun V. Regulation of citrate-dependent iron transport of Escherichia coli: FecR is required for transcription activation by FecI. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:119–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ochs M, Angerer A, Enz S, Braun V. Surface signaling in transcriptional regulation of the ferric citrate transport system of Escherichia coli: mutational analysis of the alternative sigma factor FecI supports its essential role in fec transport gene transcription. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;250:455–465. doi: 10.1007/BF02174034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pressler U, Staudenmaier H, Zimmermann L, Braun V. Genetics of the iron dicitrate transport system of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2716–2724. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.6.2716-2724.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schöffler H, Braun V. Transport across the outer membrane of Escherichia coli via the FhuA receptor is regulated by the TonB protein of the cytoplasmic membrane. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;217:378–383. doi: 10.1007/BF02464907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharp M M, Chan C L, Lu C Z, Marr M T, Nechaev S, Merrit E W, Severinov K, Roberts J W, Gross C A. The interface of a ς with core RNA polymerase is extensive, conserved, and functionally specialized. Genes Dev. 1999;13:3015–3026. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.3015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shuler M F, Tatti K M, Wade K H, Moran C P. A single amino acid substitution in sigma E effects its ability to bind core RNA polymerase. J Bacteriol. 1995;153:597–603. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.13.3687-3694.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silhavy T S, Bermann M L, Enquist L W. Experiments with gene fusions. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Staudenmaier H, Van Hove B, Yaraghi Z, Braun V. Nucleotide sequences of the fecBCDE genes and locations of the proteins suggest a periplasmic-binding-protein-dependent transport mechanism for iron(III) dicitrate in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:2626–2633. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.5.2626-2633.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stojiljkovic I, Bäumler A J, Hantke K. Fur regulon in Gram-negative bacteria: identification and characterization of new iron-regulated Escherichia coli genes by a Fur titration assay. J Mol Biol. 1994;1236:531–546. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tabor S, Richardson C C. A bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase/promoter system for controlled exclusive expression of specific genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:1074–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.4.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takeshita S, Sato M, Toba M, Masahashi W, Hashimoto-Gotoh T. High-copy-number and low-copy-number plasmid vectors for lacZ α-complementation and chloramphenicol- or kanamycin-resistance selection. Gene. 1987;61:63–74. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90365-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valdivia R H, Falkow S. Bacterial genetics by flow cytometry: rapid isolation of Salmonella typhimurium acid-inducible promoters by differential fluorescence induction. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:367–378. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Hove B, Staudenmaier H, Braun V. Novel two-component transmembrane transcription control: regulation of iron dicitrate transport in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6749–6758. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.6749-6758.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wagegg W, Braun V. Ferric citrate transport in Escherichia coli requires outer membrane receptor protein FecA. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:156–163. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.1.156-163.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Welz D, Braun V. Ferric citrate transport of Escherichia coli: functional regions of the FecR transmembrane regulatory protein. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2387–2394. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2387-2394.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilson C, Dombroski A J. Region 1 of sigma 70 is required for efficient isomerization and initiation of transcription by Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol. 1997;267:60–74. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilson Bowers C, Dombroski A J. A mutation in region 1.1 of ς70 affects promoter DNA binding by Escherichia coli RNA polymerase holoenzyme. EMBO J. 1999;18:709–716. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.3.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wriedt K, Angerer A, Braun V. Transcriptional regulation from the cell surface: conformational change in the transmembrane protein FecR lead to altered transcription of the ferric citrate transport genes in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3320–3322. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3320-3322.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zimmermann L, Hantke K, Braun V. Exogenous induction of the iron dicitrate transport system of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1984;159:271–277. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.1.271-277.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]