Abstract

Objective

The number of older patients with heart failure (HF) is increasing in Japan and has become a social problem. There is an urgent need to develop a comprehensive assessment methodology based on the common language of healthcare; the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). The purpose of this study was to develop and confirm the appropriateness of a scoring methodology for 43 ICF categories in older people with HF.

Design

Cross-sectional survey. We applied the RAND/University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) Appropriateness Method with a modified Delphi method.

Setting and participants

We included a panel of 26 multidisciplinary experts on HF care consisting of home physicians, cardiovascular physicians, care managers, nurses, physical therapists, a pharmacist, occupational therapist, nutritionist and a social worker.

Measures

We conducted a literature review of ICF linking rules and developed a questionnaire on scoring methods linked to ICF categories in older people with HF. In the Delphi rounds, we sent the expert panel a questionnaire consisting of three questions for each of the 43 ICF categories. The expert panel responded to the questionnaire items on a 1 (very inappropriate) – 9 (very appropriate) Likert scale and repeated rounds until a consensus of ‘Appropriate’ and ‘Agreement’ was reached on all items.

Results

A total of 21 panel members responded to all the Delphi rounds. In the first Delphi round, six question items in four ICF categories did not reach a consensus of ‘Agreement’, but the result of our modifications based on panel members’ suggestions reached to a consensus of ‘Appropriate’ and ‘Agreement’ on all questions in the second Delphi round.

Conclusion

The ICF-based scoring method for older people with HF developed in this study was found to be appropriate. Future work is needed to clarify whether comprehensive assessment and information sharing based on ICF contributes to preventing readmissions.

Keywords: heart failure, rehabilitation medicine, public health, geriatric medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

An expert panel familiar with heart failure care, consisting of home physicians, care managers and multidisciplinary medical professionals, rated the ‘appropriateness’ of the questions in each International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) category through a multiple-round process to reach a consensus.

The assessment domains studied the 43-item ICF relevant to older adults with heart failure, covering not only the medical assessment but also the physical and mental functioning, activity and social participation, and environmental factors.

The expert panel comprised general practitioners, cardiologists and paramedical professions (rehabilitation, nursing care and welfare), but caution is needed in generalising the findings because of the study’s limited geographical area.

Introduction

In Japan, cardiovascular disease is the second leading cause of death.1 In addition, cardiovascular disease accounts for 20.6% of all cases requiring nursing care, and the annual medical costs exceed 6 trillion yen (USD 46 billion).2 3 The Japanese government has approved the Japanese National Plan for Promotion of Measures Against Cerebrovascular and Cardiovascular Disease in 2020. This Japanese National Plan promotes the establishment of a comprehensive community care system that encompasses health, medical care, welfare, nursing care and the sharing of evidence-based information.4 5

Among cardiovascular diseases, heart failure (HF) is increasing with the ageing of the population, with the number of patients in Japan expected to exceed 1.3 million by 2030.6 7 HF reduces the quality of life of patients and their families by repeated rehospitalisations due to exacerbations, and the increased burden of medical expenses.8–10 The 1-year readmission rate for patients with HF is 35% in Japan, but a study of elderly patients with HF in the USA reported a rate of 64%.11 12 Elderly patients with HF have multiple comorbidities, such as atrial fibrillation, chronic renal failure, dementia and depression, which are factors associated with readmission.13 In addition, many factors have been reported to be associated with readmission in patients with HF, including cognitive function, depression/anxiety, exercise tolerance, muscle strength, walking speed, activities of daily living (ADL), and instrumental activities of daily living.14–18 The Guideline on Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure (JCS 2017/JHFS 2017) recommends that patients with limited self-care capabilities, such as elderly patients with HF, should receive education and support from their families and actively use social resources such as home physicians and home-visit nursing.19 Social support and information sharing in the community have been reported to prevent HF readmissions, and there is an urgent need to establish an information sharing system between medical professionals and care professionals in the community.20 21

The Japanese Society of Heart Failure recommends the use of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) for the comprehensive assessment and multidisciplinary information sharing in elderly patients with HF.22 The ICF was introduced by the WHO in 2001; it aims to provide a framework for health and health-related conditions. The ICF is expected to be used as a common language for patients, their families, medical professionals and caregivers.23 However, the ICF has not been widely used in clinical practice because of the complexity of the coding and the unreliability of the scores.24–28 To promote the use of the ICF in clinical practice, the WHO provides the ICF Core Set and the ICF Linking Rules. The ICF Core Set is a set of identified ICF categories for assessing a patient’s special health condition or special medical background.29 The ICF Linking Rules are a method of linking ICF categories with existing assessment methods.30 31 The ICF core set for chronic ischaemic heart disease and the Geriatric ICF core set have already been developed, but these ICF categories are not appropriate for adaptation to older patients with HF.32 33 Therefore, 43 ICF categories were selected for the comprehensive assessment of older patients with HF through the questionnaire survey of a multidisciplinary group of medical professionals and care professionals.34 35 The 43 ICF categories specific to older patients with HF consisted of 17 body functions and one body structure, 19 activities and participation, and 6 environmental factors. However, in order to efficiently use ICF-based assessments in clinical practice, it is necessary to develop scoring methods linked to existing assessments.

The purpose of this study was to develop a scoring method of older patients with HF based on the ICF, and to determine its appropriateness using the Delphi technique.

Method

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public are not involved in the design, planning, conduct or reporting of this study.

Design

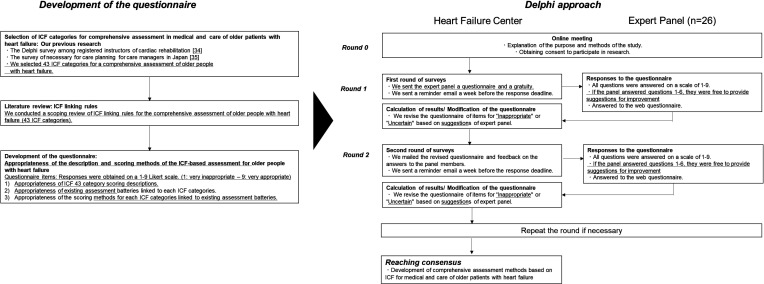

We applied the Delphi method to an expert panel. The Delphi method is a consensus method used in the development of guidelines and clinical indicators, and is effective in guiding assessments and treatments for which there is limited evidence. The Delphi method is also a standard practice in the development of ICF Core Sets.29 We developed a questionnaire based on the literature review and structured a two-stage Delphi survey with an expert panel, referring to the RAND/UCLA appropriateness methodology.36 (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Development of questionnaire and Delphi process flow. ICF, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health.

Establishing of the expert panel

We established an expert multidisciplinary panel consisting of 26 medical and care professionals in Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan. The members of the expert committee were professionals with leadership roles in community care, all of whom have expertise in the assessment, treatment and care of older patients with HF. Five home physicians and 10 care managers were recommended by the Hiroshima Care Manager Association. All 5 home physicians are specialists in internal medicine who engage in home visits while all 10 care managers are board members of the Hiroshima Care Manager Association and leaders in their respective communities. In addition, we included 11 medical multidisciplinary professionals involved in HF care at specialised medical institutions recommended by the Hiroshima Heart Health Promotion Project in our panel.37 The 11 medical multidisciplinary members were: 2 cardiovascular physicians, 2 nurses certified in chronic HF nursing, 2 physiotherapists with registered instructors of cardiac rehabilitation, 1 occupational therapist with registered instructors of cardiac rehabilitation, 1 certified pharmacist, 1 nutritionist and 1 social worker.

Development of the questionnaire

We developed scoring methods for the 43 ICF categories linking to existing assessment batteries.34 35 To develop the questionnaire, we first conducted a literature review of the ICF linking rules. The ICF linking rules are a systematic methodology for linking the existing assessment batteries to the ICF codes.30 31 All articles related to the ICF linking rule from January 2005 to August 2020 were included in the study. We used Medline (PubMed), Cochrane Library, CINAHL and PsycoInfo as electronic article databases. The search terms in the electronic article database were ‘ICF’ and ‘Linking rule’ or ‘Rasch’ in medical subject headings. The search criteria were as follows: (1) written in English, (2) cross-sectional study, cohort study, or case-control study, (3) target group of people aged 18 years or older, (4) use of an existing assessment battery, (5) results from ICF data or Rasch analysis of the ICF data, and (6) ‘ICF’ and ‘linking rule’ present in the title. The literature review was carried out by five authors (SS, NG, HF, SN and YT) in two phases. In the first phase, the appropriateness of the titles and abstracts were assessed based on the search criteria. In the second phase, the full text was assessed. Finally, we conducted a qualitative analysis of the articles to select an assessment battery that could be adapted to older patients with HF and to clarify its association with the 43 ICF categories. We completed the questionnaire based on the results of this literature review and the explanatory notes in the ICF Reference Guide.38 39 We set three questions for each of the 43 ICF categories and prepared 1 (very inappropriate) – 9 (very appropriate) Likert scale responses to assess appropriateness. Appropriateness was evaluated on a median response scale with the following three levels: 1–3 as ‘inappropriate’, 4–6 as ‘uncertain’, and 7–9 as ‘appropriate’. The three questionnaire items were as follows: (1) Appropriateness of the 43 ICF category scoring descriptions, (2) appropriateness of existing assessment batteries linked to each ICF categories, and (3) appropriateness of the scoring methods for each ICF categories linked to existing assessment batteries. All questionnaires were developed using a Google Form, with a description of each ICF category and the rationale for scoring (online supplemental materials 1).

bmjopen-2021-060609supp001.pdf (164.3KB, pdf)

Delphi process and funding consensus

The Delphi process for reaching a consensus is shown in figure 1. Following the RAND/UCLA appropriateness methodology,28 we used the median scores of the responses from the panellists to assess appropriateness. We rated the appropriateness of the 43 ICF categories as ‘Appropriate’ if the median respondent’s score was from 7 to 9, ‘Uncertain’ if it was from 4 to 6, and ‘Inappropriate’ if it was from 1 to 3. In accordance with the RAND/UCLA guidelines, we defined ‘Agreement’ or ‘Disagreement’ according to the number of panellists who rated outside the range of the tertiles (1–3; 4–6; 7–9), including the median. ‘Agreement’ was defined as fewer than one-third of panellists rating outside the range of the tertile values, whereas ‘Disagreement’ was defined as more than one-third of panellists rating the extremes (1–3 range and 7–9 range), not including the median.

Before conducting the Delphi survey, the HF Centre (HFC) held an online meeting for the panel members. In the online meeting, we explained the purpose of our study and the methods of the Delphi process to the panel members and obtained their consent to participate in the study. In the first round, the HFC mailed a sheet with instructions on how to conduct the ICF category adequacy assessment, as well as the URL and QR codes for the questionnaire. The panel members responded to three questions in 43 ICF categories on a scale of 1–9. In addition, panel members provided open-ended suggestions for improvements to the questions they scored 1–6. The HFC collated the panel members’ responses. We revised the scoring descriptions and existing assessment batteries linked to the ICF categories responded to as ‘Inappropriate’, ‘Uncertain’ or ‘Disagreement’ based on the panel’s suggestions. In the second round, the HFC emailed the revised questionnaire and feedback based on the panel members’ responses. As in the first round, panel members again scored the appropriateness of three of the question items in all 43 ICF categories. In addition, the panel members provided suggestions for improvements to the scoring methods on those ones scored 1–6.

The HFC compiled the panel members’ responses and assessed their appropriateness. We also revised the descriptions of the questionnaire or scoring methods based on the panel’s suggestions. The revised questionnaire was emailed to the panel members, and a final consensus was reached after confirming that there were no comments for revision.

Analysis

Data were exported from Google Forms to Microsoft Excel 2019 (Microsoft Washington USA) for descriptive calculations. Data are presented as simple totals and median.

Results

Characteristics of the expert panel participants

A total of 26 experts agreed to participate in the study. In the first round, 24 of the 26 invited experts responded to the questionnaire. In the second Delphi round, 21 experts responded to the questionnaires. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the experts who responded to all Delphi rounds.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the expert panel participants who responded to all Delphi rounds (n=21)

| Characteristics | n (%) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 8 (38.1) |

| Female | 13 (61.9) |

| Professions | |

| Home physicians | 4 (19.0) |

| Cardiovascular physicians | 1 (4.8) |

| Care managers | 9 (42.8) |

| Nurses | 3 (14.3) |

| Pharmacist | 1 (4.8) |

| Physical therapists | 2 (9.5) |

| Occupational therapist | 1 (4.8) |

| Type of facilities | |

| Hospital: acute care ward | 6 (28.6) |

| Hospital: rehabilitation ward | 2 (9.5) |

| Clinic | 4 (19.0) |

| Regional comprehensive support centre | 2 (9.5) |

| Community care centre/home nursing station | 6 (28.6) |

| Municipal office | 1 (4.8) |

Development of the Delphi questionnaire of ICF assessment method for older patients with HF

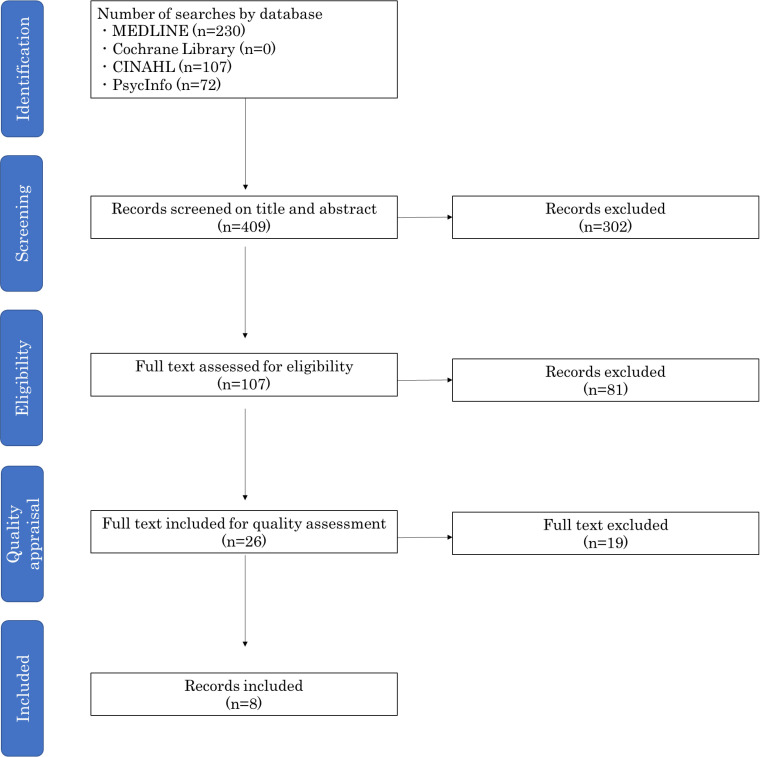

Figure 2 showed the process of literature review. Following a two-stage screening process, we conducted a qualitative analysis of 26 references. In the qualitative analysis, we excluded 19 references dealing with disease-specific assessment batteries that could not be adapted to older patients with HF (eg, stroke, musculoskeletal disease, hand surgery, low back pain). Eight articles on ICF linking rules were included. Finally, we employed 11 existing assessment batteries on eight articles links to the 43 ICF categories (online supplemental material 2).40–47 Eleven existing assessment batteries were included: assessment of ADL (such as Functional Independence Measure and Barthel Index), assessment of general health-related quality of life (such as Short Form 36 and the European Quality of Life instrument, The WHO Quality of Life), assessment of general health status (such as the Nottingham Health Profile, the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0)), and assessment of falls (such as Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I), the Swedish version of the Falls Efficacy Scale (FES[S]), the Activities-specific Balance Confidence Scale (ABC), and the modified Survey of Activities and Fear of Falling in the Elderly). We identified these existing assessment batteries as linked to 20 of the 43 categories. However, we included only the FIM and the BI. We did not include assessment batteries for general health-related quality of life, general health status and falls in the questionnaire because these were not consistent with the aims of this study.

Figure 2.

Selection of records and process flow diagrams.

bmjopen-2021-060609supp002.pdf (84.5KB, pdf)

Therefore, we developed a scoring methodology for ICF categories other than ADL, based on the Italian ICF Guidelines and the ICF Reference Guide.38 39 48 Finally, we decided to provide 30 existing assessment batteries linking to ICF categories, and to score the remaining 13 categories using only the scoring descriptions (table 2).

Table 2.

Results of the three questions of the 43 ICF categories in the second Delphi round

| ICF categories | Existing assessment batteries linked to ICF categories | Question items | ||||||

| (1) Appropriateness of ICF 43 category scoring descriptions | (2) Appropriateness of existing assessment batteries linked to each ICF categories | (3) Appropriateness of the scoring methods for each ICF categories linked to existing assessment batteries | ||||||

| Median score (/9) | Number of outside median tertile (/21) | Median score (/9) | Number of outside median tertile (/21) | Median score (/9) | Number of outside median tertile (/21) | |||

| b110 | Consciousness function | Japan Coma Scale | 8 | 3 | 9 | 2 | 8 | 1 |

| b114 | Orientation function | Mimi-Mental State Examination | 8 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 2 |

| b130 | Energy and drive function | Vitality Index | 8 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 8 | 2 |

| b134 | Sleep function | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index | 8 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 7 | 4 |

| b164 | Higher-level cognitive functions | Frontal Assessment Battery | 8 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 8 | 3 |

| b410 | Heart function | Echocardiography; left ventricular function, ECG | 7 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 7 | 3 |

| b415 | Blood vessel function | Fontaine classification | 8 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 8 | 4 |

| b420 | Blood pressure function | Blood pressure | 8 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 2 |

| b440 | Respiration function | SpO2, Respiration Rate | 8 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 8 | 1 |

| b455 | Exercise tolerance function | Specific Activity Scale | 8 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 8 | 1 |

| b460 | Sensations associated with cardiovascular and respiratory functions | NYHA classification | 8 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 9 | 1 |

| b525 | Defaecation function | – | 8 | 3 | – | – | – | – |

| b530 | Weight maintenance functions | Body Mass Index | 8 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 8 | 3 |

| b545 | Water, mineral and electrolyte balance functions | Blood test: Na, K | 8 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 7 | 3 |

| b620 | Urination function | – | 8 | 4 | – | – | – | – |

| b710 | Mobility of joint function | Range Of Motion | 8 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 8 | 2 |

| b730 | Muscle power function | Manual Muscle Test or five-times sit-to-stand | 8 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 8 | 4 |

| s410 | Structure of the cardiovascular system | Echocardiography; Severity of valve function Chest radiograph; CTR |

7 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 8 | 2 |

| d177 | Making decisions | – | 8 | 3 | – | – | – | – |

| d230 | Carrying out daily routine | – | 8 | 2 | – | – | – | – |

| d310 | Communicating with-receiving-spoken messages | FIM; Comprehension | 8 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 1 |

| d330 | Speaking | FIM; Expression | 8 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 2 |

| d420 | Transferring oneself | FIM; Transfers | 8 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 1 |

| d450 | Walking | FIM; Walk 5 m walk test |

8 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 8 | 5 |

| d510 | Washing oneself | FIM; Bathing | 8 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 1 |

| d520 | Caring for body parts | FIM; Grooming | 7 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 7 | 1 |

| d530 | Toileting | FIM; Toileting | 7 | 2 | 9 | 2 | 7 | 3 |

| d540 | Dressing | FIM; Dressing | 8 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 1 |

| d550/d560 | Eating/ Drinking | FIM; Eating | 8 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 8 | 3 |

| d570 | Looking after one’s health | – | 8 | 3 | – | – | – | – |

| d620 | Acquisition of goods and services | Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scale; Shopping | 8 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 8 | 3 |

| d630 | Preparing meals | Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scale; Food preparation | 8 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 3 |

| d640 | Doing housework | Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scale; Housekeeping | 8 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 8 | 3 |

| d710 | Basic interpersonal interactions | – | 8 | 3 | – | – | – | – |

| d760 | Family relationships | – | 8 | 3 | – | – | – | – |

| d920 | Recreation and leisure | – | 8 | 2 | – | – | – | – |

| e310 | Immediate family | – | 8 | 3 | – | – | – | – |

| e340 | Personal care providers and personal assistants | – | 8 | 2 | – | – | – | – |

| e355 | Health professionals | – | 8 | 1 | – | – | – | – |

| e410 | Individual attitudes of immediate family members | – | 8 | 2 | – | – | – | – |

| e575 | General social support services, systems, and policies | – | 8 | 2 | – | – | – | – |

| e580 | Health services, systems, and policies | – | 8 | 3 | – | – | – | – |

CTR, cardiothoracic ratio; FIM, Functional Independence Measure; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SpO2, oxygen saturation.

Delphi round 1

From February to March of 2021, 24 panel members (92.3%) responded to round 1 of the Delphi process. ‘Agreement’ was defined as when seven or fewer panellists rated outside the range of the three quartiles (1-3; 4-6; 7-9), including the median. ‘Disagreement’ was defined as eight or more panellists rating the extremes (1–3 range and 7–9 range) that did not include the median. The results of the Delphi round 1 panel members’ responses are shown in online supplemental material 3. The median response of panel members was ‘appropriate’ 7–9 for all three questions in the 43 ICF categories. In the result, ‘Agreement’ was not reached on six question items in four ICF categories. The question items in the ICF categories on which agreement was not reached were ‘b134 Sleep functions: (1) scoring descriptions, b410 Heart function: (2) existing assessment batteries and (3) scoring methods linked to ICF categories, s410 Structure of the cardiovascular systems: (2) existing assessment battery and (3) scoring methods linked to ICF categories and d330 Speaking: (2) existing battery of assessments’. We added a scoring method for d134 Sleep function based on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, based on the panel members’ suggestions. For b410 heart function, S410 Structure of cardiovascular system and d330 Speaking, we revised the existing assessment battery and scoring method linked to the ICF categories based on the panel’s suggestions.

bmjopen-2021-060609supp003.pdf (72.8KB, pdf)

Delphi round 2

From April to May of 2021, we emailed the revised questionnaire to the 24 panel members who responded to round 1. Twenty-one panel members (87.5%) responded to the round 2 questionnaire. ‘Agreement’ was defined as when six or fewer panellists rated outside the range of the three quartiles (1–3; 4–6; 7–9), including the median. ‘Disagreement’ was defined as seven or more panellists rating the extremes (1–3 range and 7–9 range) that did not include the median. Table 2 shows the results of the panel members’ responses to Delphi Round 2. The results showed that for all ICF category questions, the median responses ranged from 7 to 9 ‘Appropriate’, with all items reaching ‘Agreement’. However, as two panel members answered ‘Inappropriate’ 1–3 for the d450 gait, we modified the existing assessment battery linked to the ICF categories to FIM only, based on members’ suggestions. We sent the manual of the modified assessment method by email to all panel members who participated in Round 2, asking for their comments, and confirming that we had reached a consensus.

Discussion

We have developed a comprehensive assessment for older people with HF based on ICF for widespread use in clinical practice and verified the appropriateness of the scoring method using the RAND Delphi method. In this study, we drew on our literature review and the ICF Reference Guide to link existing assessment batteries for 28 of the 43 ICF categories. In the first Delphi round, ‘agreement’ was not reached on six questions in the four ICF categories, and the explanation and scoring methods were modified. In the second round of Delphi, all question items of the 43 ICF category were reached a consensus of ‘Appropriate’ and ‘Agreement’.

The purpose of this study was to develop an assessment method that could be used not only by cardiovascular physicians but also by medical professionals: home physicians, care managers and paramedical professions. Therefore, we adopted a simple evaluation method that requires as little special machinery and environment as possible. For example, although exercise tolerance at b455 has been reported to be a prognostic factor for HF,49 we avoided the cardiopulmonary exercise testing and 6 min walk test, and the Specific Activity Scale was chosen instead.50–54 We selected gait speed and FIM as the existing assessment batteries linked to the d450 walking, but we selected only FIM for simplicity and ease of assessment at the suggestion of the panel members in the second Delphi round. The ICF categories in this study did not include renal function, BNP or anaemia, which are prognostic factors for HF.55 We suggest that these items be added, although the increase in the items may prevent their widespread use in the clinical setting, making their clinical use more difficult. In addition, the comprehensive ICF-based assessment of older patients with HF developed in this study did not include personal factors such as age, gender, values, lifestyle, coping strategies and personality.

In recent years, patient-centred interventions have become a principle in the care of chronic diseases.56 The ESC guidelines similarly recommend patient-centred care.57

We propose that when using the ICF to share information on older people with HF across multiple professions, it is necessary to include not only the 43 ICF categories, but also personal factors.

In Japan, the establishment of a comprehensive community care system that integrates medical care, welfare and nursing care is being promoted, but evidence for information sharing is lacking. We expect that the ICF-based assessment method for older patients with HF developed in this study will be widely used in clinical practice.

Strengths and limitations

Since the purpose of this study was to develop a common community-based evaluation method for medical and nursing care, we constructed an expert panel related to medical professions and nursing care professions in Hiroshima prefecture. Since there is no variation in the regions of the panel members, the existence of selective bias cannot be denied. Therefore, we suggest that the results of this study should be used with caution in regions other than Hiroshima prefecture. This study was based on the RAND/UCLA Delphi method, but face-to-face meetings could not be conducted because of the current coronavirus pandemic. Therefore, the implementation is not strictly based on the RAND/UCLS method. We believe that we should have held an online meeting during the Delphi Round 2. In this study, the Delphi method through expert consensus was used to clarify the appropriateness of the evaluation method. The shortcomings of the Delphi method are the possibility of coercion and inducement to gather opinions and the issue of the validity of the questionnaire. In the future, it will be necessary to clarify the validity of the evaluation method in survey studies of older patients with HF.

Implications and future directions

The results of this study have two implications. First, it is the establishment of a comprehensive assessment method for older patients with HF, which is a social problem in Japan. Comprehensive multidisciplinary assessment is important to prevent rehospitalisation for HF, and the ICF-based scoring method developed in this study is expected to prevent rehospitalisation. Second, the ICF-based evaluation method allows for an international comparison of the effectiveness of HF treatment and information sharing. Wagner proposes a patient-centred model for chronic disease care that utilises local social resources and information sharing systems such as information and communication technology.58 59 In the future, it is necessary to establish an information sharing system using a comprehensive assessment method based on the ICF, and to examine the effect of readmission prevention and differences in life function according to local policies.

Conclusion

We developed a scoring method based on the ICF for older patients with HF and clarified its appropriateness using the RAND/UCLA Delphi method. Future work is required to develop an ICF-based information sharing system and to clarify its impact on the prevention of rehospitalisation and quality of life in older patients with HF.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

For their contribution to the development of the ICF-based comprehensive assessment for older patients with heart failure, the team would like to acknowledge Dr Etsushi Akimoto, Dr Satoshi Ishida, Dr Futoshi Konishi, Dr Hideki Nojima, MS Keiko Ishii, MS Kaoru Okazaki, MS Mayumi Ono, MS Eiko Kishikawa, MS Emi Ochibe, MS Shizue Kobayasi, MS Kaori Tikashita, MS Yasue Saitou, MR Hiroshi Sakurashita, MR Nobuyoshi Satou, MS Misuzu Sakai, MR Takayuki Santa, MS Hiromi Shigeoka, MS Yoko Nakasa, MR Tomoaki Honma, MS Kazue Mitinori, MS Midori Motohiro and MS Norie Yoshimoto. This study was conducted as a part of the Hiroshima Heart Health Promotion Project. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Footnotes

Contributors: SS, TK, TH and HK contributed to the conceptualisation of the study. SS, NG, HF, SN, YT, NM, KK, MN and MY were responsible for designing the questionnaire and collecting and analysing the data. MN, MY, MM, HO and YY were responsible for recruiting the study participants. YN, YK and HK were responsible for interpreting the results and managing the project. SS and HK supervised all research activities. All authors reviewed the current draft and approved the final current submission. The guarantor for this paper is SS.

Funding: This work was supported by the MHLW Comprehensive Research on Statistical Information Program, Grant Number JPMH20AB1002.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. We explained the purpose and content of the study in writing and at online meetings to the expert panel members who participated in the study and obtained their written consent. The received data were processed after deleting personal information (names). Approval was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee for Epidemiological Research, Hiroshima University (Approval No: E-2580). This study was supported by the MHLW Comprehensive Research on Statistical Information Program, Grant Number JPMH20AB1002.

References

- 1.Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare . Vital statistics of Japan, 2018. Available: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/jinkou/houkoku18/dl/all.pdf [Accessed 19 Oct 2021].

- 2.Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare . Comprehensive survey of living conditions, 2019. Available: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/k-tyosa/k-tyosa19/dl/14.pdf [Accessed 19 Oct 2021].

- 3.Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare . Estimates of national medical care expenditure, 2017. Available: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/k-iryohi/17/dl/data.pdf [Accessed 19 Oct 2021].

- 4.Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare, Japan . The Japanese national plan for promotion of measures against cerebrovascular and cardiovascular disease 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Kuwabara M, Mori M, Komoto S. Japanese national plan for promotion of measures against cerebrovascular and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2021;143:1929–31. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.052737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okura Y, Ramadan MM, Ohno Y, et al. Impending epidemic: future projection of heart failure in Japan to the year 2055. Circ J 2008;72:489–91. 10.1253/circj.72.489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yasuda S, Miyamoto Y, Ogawa H. Current status of cardiovascular medicine in the aging society of Japan. Circulation 2018;138:965–7. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nieminen MS, Dickstein K, Fonseca C, et al. The patient perspective: quality of life in advanced heart failure with frequent hospitalisations. Int J Cardiol 2015;191:256–64. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.04.235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis EF, Claggett BL, McMurray JJV, et al. Health-related quality of life outcomes in PARADIGM-HF. Circ Heart Fail 2017;10:e003430. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.116.003430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee H, Oh S-H, Cho H, et al. Prevalence and socio-economic burden of heart failure in an aging society of South Korea. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2016;16:215. 10.1186/s12872-016-0404-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsuchihashi M, Tsutsui H, Kodama K, et al. Medical and socioenvironmental predictors of hospital readmission in patients with congestive heart failure. Am Heart J 2001;142:E7. 10.1067/mhj.2001.117964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernandez AF, Hammill BG, O’Connor CM, et al. Clinical effectiveness of beta-blockers in heart failure: findings from the OPTIMIZE-HF (organized program to initiate lifesaving treatment in hospitalized patients with heart failure) registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:184–92. 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019;139:e56–28. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huynh QL, Negishi K, Blizzard L, et al. Mild cognitive impairment predicts death and readmission within 30days of discharge for heart failure. Int J Cardiol 2016;221:212–7. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.07.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Connor CM, Hasselblad V, Mehta RH, et al. Triage after hospitalization with advanced heart failure: the escape (evaluation study of congestive heart failure and pulmonary artery catheterization effectiveness) risk model and discharge score. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:872–8. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lo AX, Donnelly JP, McGwin G, et al. Impact of gait speed and instrumental activities of daily living on all-cause mortality in adults ≥65 years with heart failure. Am J Cardiol 2015;115:797–801. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.12.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takabayashi K, Kitaguchi S, Iwatsu K, et al. A decline in activities of daily living due to acute heart failure is an independent risk factor of hospitalization for heart failure and mortality. J Cardiol 2019;73:522–9. 10.1016/j.jjcc.2018.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Löfvenmark C, Mattiasson A-C, Billing E, et al. Perceived loneliness and social support in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2009;8:251–8. 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2009.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsutsui H, Ide T, Ito H. JCS/JHFS 2021 guideline focused update on diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Circ J 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sokoreli I, Cleland JG, Pauws SC, et al. Added value of frailty and social support in predicting risk of 30-day unplanned re-admission or death for patients with heart failure: an analysis from OPERA-HF. Int J Cardiol 2019;278:167–72. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.12.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradley EH, Curry L, Horwitz LI, et al. Hospital strategies associated with 30-day readmission rates for patients with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2013;6:444–50. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.000101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Japan Heart Failure Society Guidelines Committee . Statement on the treatment of elderly heart failure patients, 2016. Available: http://www.asas.or.jp/jhfs/pdf/Statement_HeartFailurel.pdf [Accessed 19 Nov 2021].

- 23.World Health Organization . ICF International classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva: WHO, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maribo T, Petersen KS, Handberg C, et al. Systematic literature review on ICF from 2001 to 2013 in the Nordic countries focusing on clinical and rehabilitation context. J Clin Med Res 2016;8:1–9. 10.14740/jocmr2400w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okochi J, Utsunomiya S, Takahashi T. Health measurement using the ICF: test-retest reliability study of ICF codes and qualifiers in geriatric care. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2005;3:46. 10.1186/1477-7525-3-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uhlig T, Lillemo S, Moe RH, et al. Reliability of the ICF core set for rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:1078–84. 10.1136/ard.2006.058693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Starrost K, Geyh S, Trautwein A, et al. Interrater reliability of the extended ICF core set for stroke applied by physical therapists. Phys Ther 2008;88:841–51. 10.2522/ptj.20070211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hilfiker R, Obrist S, Christen G, et al. The use of the comprehensive International classification of functioning, disability and health core set for low back pain in clinical practice: a reliability study. Physiother Res Int 2009;14:147–66. 10.1002/pri.436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Selb M, Escorpizo R, Kostanjsek N. A guide on how to develop an international classification of functioning, disability and health core set. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2015;51:105–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cieza A, Geyh S, Chatterji S, et al. ICF linking rules: an update based on lessons learned. J Rehabil Med 2005;37:212–8. 10.1080/16501970510040263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cieza A, Fayed N, Bickenbach J, et al. Refinements of the ICF linking rules to strengthen their potential for establishing comparability of health information. Disabil Rehabil 2019;41:574–83. 10.3109/09638288.2016.1145258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cieza A, Stucki A, Geyh S, et al. ICF core sets for chronic ischaemic heart disease. J Rehabil Med 2004;44 Suppl:94–9. 10.1080/16501960410016785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spoorenberg SLW, Reijneveld SA, Middel B, et al. The geriatric ICF core set reflecting health-related problems in community-living older adults aged 75 years and older without dementia: development and validation. Disabil Rehabil 2015;37:2337–43. 10.3109/09638288.2015.1024337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shiota S, Naka M, Kitagawa T. Selection of comprehensive assessment categories based on the international classification of functioning, disability, and health for elderly patients with heart failure: a Delphi survey among registered instructors of cardiac rehabilitation. Occup Ther Int 20212021;2021:6666203. 10.1155/2021/6666203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shiota S, Kitagawa T, Hidaka T, et al. The international classification of functioning, disabilities, and health categories rated as necessary for care planning for older patients with heart failure: a survey of care managers in Japan. BMC Geriatr 2021;21:704. 10.1186/s12877-021-02647-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguilar MD. The Rand/UCLA appropriateness method user’s manual. Santa Monica: RAND, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kitagawa T, Hidaka T, Naka M, et al. Current medical and social issues for hospitalized heart failure patients in Japan and factors for improving their outcomes - insights from the REAL-HF registry. Circ Rep 2020;2:226–34. 10.1253/circrep.CR-20-0011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mukaino M, Prodinger B, Yamada S, et al. Supporting the clinical use of the ICF in Japan - development of the Japanese version of the simple, intuitive descriptions for the ICF Generic-30 set, its operationalization through a rating reference guide, and interrater reliability study. BMC Health Serv Res 2020;20:66. 10.1186/s12913-020-4911-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Senju Y, Mukaino M, Prodinger B, et al. Development of a clinical tool for rating the body function categories of the ICF generic-30/rehabilitation set in Japanese rehabilitation practice and examination of its interrater reliability. BMC Med Res Methodol 2021;21:121. 10.1186/s12874-021-01302-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prodinger B, O'Connor RJ, Stucki G, et al. Establishing score equivalence of the functional independence measure motor scale and the Barthel index, utilising the International classification of functioning, disability and health and Rasch measurement theory. J Rehabil Med 2017;49:416–22. 10.2340/16501977-2225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bladh S, Nilsson MH, Carlsson G. Content analysis of 4 fear of falling rating scales by linking to the International classification of functioning, disability and health. PM&R 2013;5:573–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Milman N, Boonen A, Merkel PA, et al. Mapping of the outcome measures in rheumatology core set for antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis to the International classification of function, disability and health. Arthritis Care Res 2015;67:255–63. 10.1002/acr.22414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoang-Kim A, Schemitsch E, Kulkarni AV, et al. Methodological challenges in the use of hip-specific composite outcomes: linking measurements from hip fracture trials to the International classification of functioning, disability and health framework. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2014;134:219–28. 10.1007/s00402-013-1824-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cieza A, Stucki G. Content comparison of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) instruments based on the International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). Qual Life Res 2005;14:1225–37. 10.1007/s11136-004-4773-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cieza A, Hilfiker R, Boonen A, et al. Items from patient-oriented instruments can be integrated into interval scales to operationalize categories of the International classification of functioning, disability and health. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:912–21. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Darzins SW, Imms C, Di Stefano M. Measurement of activity limitations and participation restrictions: examination of ICF-linked content and scale properties of the FIM and PC-PART instruments. Disabil Rehabil 2017;39:1025–38. 10.3109/09638288.2016.1172670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prodinger B, Stucki G, Coenen M, et al. The measurement of functioning using the International classification of functioning, disability and health: comparing qualifier ratings with existing health status instruments. Disabil Rehabil 2019;41:541–8. 10.1080/09638288.2017.1381186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giardini A, Vitacca M, Pedretti R, et al. [Linking the ICF codes to clinical real-life assessments: the challenge of the transition from theory to practice]. G Ital Med Lav Ergon 2019;41:78–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.JCS/JACR . Guideline on rehabilitation in patients with cardiovascular disease, 2021. Available: https://www.j-circ.or.jp/cms/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/JCS2021_Makita.pdf [Accessed 19 Nov 2021].

- 50.Mancini DM, Eisen H, Kussmaul W, et al. Value of peak exercise oxygen consumption for optimal timing of cardiac transplantation in ambulatory patients with heart failure. Circulation 1991;83:778–86. 10.1161/01.CIR.83.3.778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Keteyian SJ, Patel M, Kraus WE, et al. Variables measured during cardiopulmonary exercise testing as predictors of mortality in chronic systolic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:780–9. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.11.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakanishi M, Takaki H, Kumasaka R, et al. Targeting of high peak respiratory exchange ratio is safe and enhances the prognostic power of peak oxygen uptake for heart failure patients. Circ J 2014;78:2268–75. 10.1253/circj.CJ-14-0047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ats Committee on proficiency standards for clinical pulmonary function laboratories. ats statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:111–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goldman L, Hashimoto B, Cook EF, et al. Comparative reproducibility and validity of systems for assessing cardiovascular functional class: advantages of a new specific activity scale. Circulation 1981;64:1227–34. 10.1161/01.CIR.64.6.1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure (JCS 2017/JHFS 2017), 2018. Available: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/05-Shingikai-10901000-Kenkoukyoku-Soumuka/0000202651.pdf [Accessed 19 Nov 2021].

- 56.Wagner EH, Bennett SM, Austin BT, et al. Finding common ground: patient-centeredness and evidence-based chronic illness care. J Altern Complement Med 2005;11:S7–15. 10.1089/acm.2005.11.s-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M. Esc guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2021;2021:3599–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wagner EH. More than a case manager. Ann Intern Med 1998;129:654–6. 10.7326/0003-4819-129-8-199810150-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, et al. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff 2001;20:64–78. 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-060609supp001.pdf (164.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-060609supp002.pdf (84.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-060609supp003.pdf (72.8KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.