Abstract

Introduction

Chronic diseases in older adults are one of the major epidemiological challenges of current times and leading cause of disability, poor quality of life, high healthcare costs and death. Self-management of chronic diseases is essential to improve health behaviours and health outcomes. Technology-assisted interventions have shown to improve self-management of chronic diseases. Virtual avatars can be a key factor for the acceptance of these technologies. Addison Care is a home-based telecare solution equipped with a virtual avatar named Addison, connecting older persons with their caregivers via an easy-to-use technology. A central advantage is that Addison Care provides access to self-management support for an up-to-now highly under-represented population—older persons with chronic disease(s), which enables them to profit from e-health in everyday life.

Methods and analysis

A pragmatic, non-randomised, one-arm pilot study applying an embedded mixed-methods approach will be conducted to examine user experience, usability and user engagement of the virtual avatar Addison. Participants will be at least 65 years and will be recruited between September 2022 and November 2022 from hospitals during the discharge process to home care. Standardised instruments, such as the User Experience Questionnaire, System Usability Scale, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scale, Short-Form-8-Questionnaire, UCLA Loneliness Scale, Geriatric Depression Scale, Stendal Adherence with Medication Score and Self-Efficacy for Managing Chronic Diseases Scale, as well as survey-based assessments, semistructured interviews and think-aloud protocols, will be used. The study seeks to enrol 20 patients that meet the criteria.

Ethics and dissemination

The study protocol has been approved by the ethic committee of the German Society for Nursing Science (21-037). The results are intended to be published in peer-reviewed journals and disseminated through conference papers.

Trial registration number

DRKS00025992.

Keywords: primary care, preventive medicine, geriatric medicine

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This pilot study provides an opportunity to explore the acceptability of and experiences with a potentially beneficial e-health technology in the under-represented population of chronically ill older persons in a telecare setting.

The mixed-methods study design will provide a deep and broad insight on usability, user experience and user engagement of Addison Care as a German-speaking, culturally adapted virtual avatar.

This investigation evaluates the efficacy of a sophisticated virtual avatar, Addison, in assisting with many crucial health management tasks—including medication management and health vitals monitoring.

A focus on barriers to user-engagement for those who are technologically hesitant will provide rich information concerning how best to design virtual avatars and e-health technologies to match user needs and mental models.

The primary limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size due to our selective inclusion criteria, which may diminish the ethnic and socioeconomic diversity of our sample.

Background

Societies across the globe are facing a significant shift in age demographics whereby older adults are becoming an increasingly larger group within their population. This phenomenon is one of the most salient economic, social, and medical issues of current times.1 Ageing increases both the risk for most chronic diseases and for multimorbidity. Between 34% and 61% of older adults are multimorbid,2 which can have consequences such as disability and functional decline, poor quality of life, social isolation, depression and high healthcare costs.3 4

Patients themselves have an integral role in the management of their chronic disease.5 Factors that influence effective self-management of chronic disease include: experience, skill, motivation, culture, confidence, habits, physical and mental function, social support, and access to care.6

Self-management of chronic diseases is defined as the response to signs and symptoms when they occur, with the goal that patients play an active role in optimising health outcomes and minimising the impact of their conditions.6 Self-management support refers to patient, healthcare professional and healthcare system interventions aimed to improve self-management behaviours.7 Self-monitoring vitals8 and medication adherence have been recognised as two of the most essential self-management activities performed by patients to promote their health.9

Although interventions designed to promote self-management in chronic diseases have traditionally been offered in-person, delivering these interventions remotely using available technology (eg, mobile smart phones, internet, interactive voice response, telephone, virtual reality) has become more prevalent.10 These technology-assisted interventions have shown to improve self-management and health status.11 12

Digital information technologies support people with care requirements to maintain their independence, improve quality of life, increase health literacy and aid caregivers in their duties.13 14 Telehealth is one of the fastest-growing sectors in healthcare. The term refers to a broad array of provider-to-patient communication and has been defined as using telecommunications, information technologies and devices to share information and to provide clinical, population health and administrative services at a distance.15 Remote patient monitoring (RPM) is a widely used telehealth intervention that can effectively support self-management in patients with chronic diseases.7

Remote patient monitoring

RPM is a promising solution for facilitating the patient–physician relationship while addressing the shortage of healthcare workers today. Studies concerning the efficacy of RPM has spanned the topics of postoperative rehospitalisation, chronic disease management, medication adherence and quality of life and has shown promising results.16–20 However, RPM technology can only benefit patients who choose to actively interact with the devices. As compared with younger users, elderly users also face unique challenges that are a direct result of ageing—such as declines in dexterity, hearing and vision. As a result, researchers have identified that improving ease of navigation for task completion, ensuring appropriate size and colour of font, and properly configuring the size of the hardware itself are paramount in addressing technological hesitancy.21

Virtual avatars

Graphic user interfaces, which can improve the user experience and personalise the experience for the user through virtual avatars, have begun to be incorporated into RPM systems. Virtual avatars are an emerging feature in RPM that has shown propitious results in terms of user engagement, health education and self-care behaviour.22

One important factor in the receptiveness of patients to virtual avatars is the avatar’s appearance. Bott et al23 investigated the impact of a virtual pet avatar to deliver surveys to older clients. They found that those who interacted with the avatar experienced lower rates of delirium, fewer falls and decreased loneliness. However, research has generally shown that anthropomorphic characteristics are often preferable for virtual healthcare avatars24—as well as similarities in appearance between the avatar and the user.25 Previous literature has revealed that when designing virtual agents for older persons, key factors related to acceptance of technology include conversational latency, gamification and artificially intelligent lexicon.26

User experience and technology acceptance among older persons

Understanding how older adults perceive technology and virtual avatars may lead to improvements in the accessibility, acceptability and adoption of virtual avatars among older persons with chronic diseases. This can be accomplished through user experience (UX) research, wherein the overall experience of the user is assessed through measures related to usability, user engagement, usefulness, function, credibility and satisfaction with the technology.27 While behaviour, cognition and affect are important defining components of user engagement,28 learnability, efficiency, memorability, few errors and satisfaction are defining components of usability.29 UX is based on User-Centred Design, wherein the needs and characteristics of the end user become the focus of technology design and development, with the intention of higher acceptance and fewer user errors.30

Theories that predict and explain health technology acceptance and use can help to tailor the technology to specific patient needs. One of the more recent models, the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT),31 posits that a person’s intent to use (acceptance of technology) and usage behaviour (actual use) of a technology is predicated by the patient’s performance and effort expectancy of the technology. The UTAUT also suggests social influence and facilitating conditions as determinants of behavioural intention to use the technology.31 32 Most older persons are significantly less adept at technology use than the general population, with technology anxiety being a major influence on older users’ intent to use technologies.33 However, older adults are interested in integrating new technologies into their healthcare.34 Studies confirm the applicability of the UTAUT in the context of Telecare services among older persons.35

Intervention: Addison Care tablet personal computer (PC)

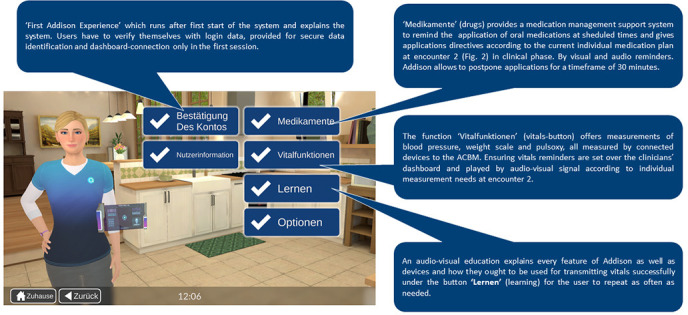

The present research pilots an intervention provided by Addison Care,36 which is an innovative home-bound connected virtual RPM platform for individuals living with chronic disease. A 3D-animated nurse named ‘Addison’ is the centre of interaction between the system and its users, personifying the telehealth experience for the user. The pilot study encompasses two health-related functions of Addison Care: ‘Addison’ supporting the user in self-monitoring relevant vitals (blood pressure, weight, pulse and oxygen saturation) as well as medication schedule adherence. This is achieved by offering reminder and monitoring functionalities (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Addison Care functions in German version (reproduced with permission from https://electroniccaregiver.com). ACBM, Addison Care base monitor.

The Addison Care hardware consists of a tablet PC with a speaker, a microphone module and a touch screen (see figure 1). The tablet connects with Bluetooth vitals measuring devices and can be installed in a user’s home. Avatar technology combined with natural language understanding and automatic speech recognition provides users with effective natural interaction with the assisting technology.22 26 Subtitles, vital signs and medications are graphically illustrated on the Addison Care interface for clear communication between the virtual agent and the user.

The Addison Tablet PC is connected to a web-based dashboard that allows access to user data, including vitals measurements and medication reminders. For the pilot study, medication plans, reminder options and contact information are managed by members of the study team, who also act as a support team for the technical setup and in case of technical problems. The intervention in this study involves voice-driven audiocentred interaction between Addison and users in German, as well as the implementation of a German touch screen interface. Introduction of Addison Care to German users requires adaption of the original technology to ensure a good cultural fit. Adaptations were made to the surroundings of the avatar, as well as to Addison’s mannerisms. Additionally, changes were made to the system to ensure a good fit between system and real life in terms of interactive elements (from basics ensuring appropriate data and time formats to more complex elements like making sure the avatar interacts in a culturally appropriate manner with the user). Voice and touch interaction modes are currently adapted from English into German. All piloted features of Addison Care are shown in figure 1.

Objectives

While other studies have provided insight into the potential of digital health technology and virtual avatars, the vast majority have been tested within laboratory settings, where older adults were unable to interact with the technology in a natural environment. Additionally, the digital health systems and virtual avatars were not culturally adapted after development.

The study aims to explore the feasibility, acceptability, experience, engagement and usability of the culturally tailored health technology and the virtual avatar Addison for self-management for older patients with chronic diseases in their own home.

Methods and analysis

A pragmatic, non-randomised, one-arm pilot study applying an embedded mixed-methods approach will be conducted to examine the primary outcomes ‘user experience’, ‘usability’ and ‘user engagement’ of the virtual avatar Addison three times within the use span. ‘Embedded’ refers to the integration of qualitative methods into a quantitative methodology framework or vice versa, to provide enriched insights or understanding into the phenomena of interest.31 37 The study design is pluralistic, problem-centred, real-world applicable and focused on the consequences of actions, stemming from pragmatism as a research paradigm.37 The present protocol followed the SPIRIT guidelines (see online supplemental file 1).38 Data collection will take place between September 2022 and November 2022.

bmjopen-2022-062159supp001.pdf (140.3KB, pdf)

Recruitment criteria and process

Eligible patients will be identified by medical specialists in in German hospitals. The inclusion criteria are as follows:

Planned patients transition from hospital to extramural care.

Three to nine drugs (regular intake of drugs, no status of hypermedication).

Sixty-five years or older with a chronic health condition.

Ability to speak and understand German language.

The exclusion criteria are:

Ten or more drugs per day.

Younger than 65 years.

Moderate to severe cognitive impairment or severe psychiatric disorders.

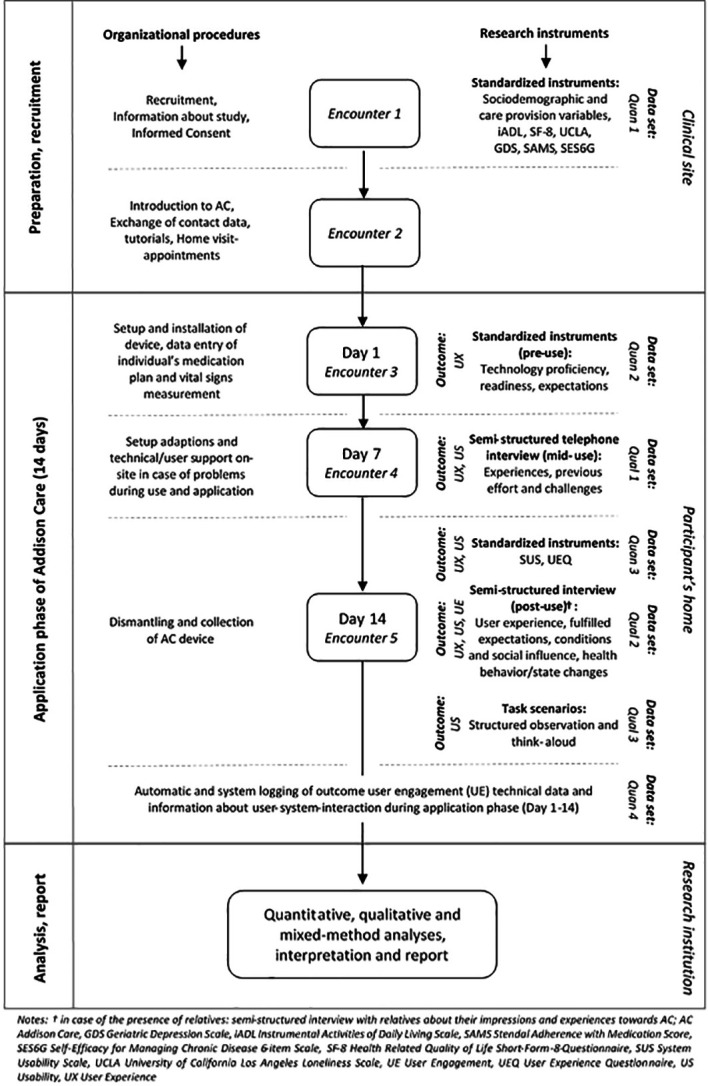

Provided that these criteria are met and general interest in using health technology is expressed, information about the pilot study and the intervention will be shared. If a patient declares the will to participate, a meeting with the support team will be arranged while the patient is still at the hospital. Potential participants will be informed of all aspects of the study through verbal instruction and written materials (figure 2, encounter 1). After written informed consent (see online supplemental file 2) is provided, living situation and sociodemographic data will be assessed by research assistants.

Figure 2.

Study flow, phenomenon of interest, instruments, data sets and settings.

bmjopen-2022-062159supp002.pdf (166.6KB, pdf)

Setting and sample size

Addison Care will be piloted in participants’ homes, located in a community setting, after their discharge from hospital for two consecutive weeks. In encounter 2 (see figure 2) within 1 day after the informed consent is provided, the support team will give first instructions on Addison Care while the participant is still hospitalised. First adjustments of reminder, medication plan and vital measurements will be provisioned for the use of Addison Tablet PC at home. This study seeks to enrol 20 patients. The sample size is an adequate number to evaluate study feasibility, test the study procedures and explore the user experience.39 40

Patient and public involvement

In advance of the pilot study, older adults assisted in the development of the data collection materials and pretesting of Addison Care. However, patients and the public were not involved in the development of the research question, outcome measures and the design of the study.

Outcomes, instruments and variables

Building on the theoretical concepts of technology acceptance (UTAUT), we will assess user experience, usability, and user engagement (primary outcomes), as well as participant background information (eg, sociodemographic and care provision) and health status-associated phenomena (functional status, quality of life and well-being, loneliness, depression, medication adherence and self-management) using standardised, quantitative and semistandardised qualitative research instruments (see figure 2).

Standardised research instruments

User experience. The German version of the User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ)41 will be used to assess user experience. The UEQ consists of 26 items along 6 scales: attractiveness (6 items, Cronbach’s alpha α=0.89), perspicuity (4 items, α=0.82), efficiency (4 items, α=0.73), dependability (4 items, α=0.65), stimulation (4 items, α=0.76) and novelty (4 items, α=0.83).41 42 Each item represents a 7-point rating scale (−3 most negative rating, +3 most positive rating) of properties that the product under study may have. An average score is computed for each scale.

Usability. To assess the usability of Addison Care, the validated German version of the System Usability Scale (SUS) will be applied.43 The SUS44 consists of 10 items and is a standardised, generic instrument for assessing the usability of technical applications, mobile applications or devices. Internal consistency has been reported to range between α=0.70 and 0.95.45 The SUS consists of 10 items, each with 5-point rating scales (1-strongly disagree to 5-strongly agree). The standardised scoring of the SUS results in a total score between 0 to 100 points using a given norm-based scoring algorithm.45

User engagement. Automatic system and data logging information will be used to measure user engagement in terms of intensity and type of interactions between users and Addison Care. This non-participatory data collection, for example, documenting data using automatically protocolled technical variables without having asked questions or the presence of an observer, will provide essential information on the actual use, used functions, and user engagement with certain contents of the product of interest.46–48

Functional status. The German translation49 of the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (iADL) scale50 will be applied to assess patients' functional status in terms of activities of daily living. The iADL is a standardised instrument that measures functionality related to eight domains of daily living. It has reported reliability coefficients ranging from 0.85 to 0.91.51 Each domain is measured using either three or four ability levels with 0 or 1 point per domain, resulting in a summary score of 8 points at maximum. Due to a strong reference of some items to household aspects, gender-specific scores will be used, for example, 0 (low function, dependent) to 8 (high function, independent) for women and 0 to 5 for men, respectively.51

Quality of life. Health-related quality of life will be measured by the German version of the Short-Form-8-Questionnaire (SF-8).52 The SF-8 assesses the eight dimensions physical functioning, role physical (role limitations because of physical health), bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional (role limitations because of emotional problems) and mental health, by one item each, and along two scales ‘physical component summary score’ and ‘mental component summary score’. The items comprise of five-point or six-point response scales that verbalise the extent to which each dimension is present. In addition to single-item analysis, the two summary scores will be measured using a given norm-based scoring method. Next to an adequate test-retest reliability,52 an overall internal consistency between α=0.86 and 0.92 have been reported.53

Loneliness. To assess participants’ perception of social isolation and loneliness, the shortened, three-item German version54 55 of the UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) Loneliness Scale will be applied. Each item exhibits a five-level response scale (very often, often, sometimes, rarely, never) and will be analysed item-by-item. Cronbach’s alpha for the three-item loneliness scale was 0.72.54

Depression. The German translation56 of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) will be used to evaluate the presence of depression.57 58 The eight-item version will be applied to make the survey as time-efficient as possible.59 Participants are asked about selected symptoms of depressive states over the past week using a dichotomous response format (no vs yes). The total sum score of the GDS-8 is 0–8 points. Internal consistency with α>0.80 has been shown.59 A recommended cut-off score of GDS ≥3 indicating relevant indications of depression will be applied.

Medication adherence. Participants’ adherence to their medication regimen will be measured by the Stendal Adherence with Medication Score (SAMS).60 SAMS consists of 18 items on a five-level response scale (0–4) assessing fully adherent to nonadherent medication behaviour per item.61 Responses are summarised into a cumulative point scale (0–72), which can be categorised as fully adherent (0), moderately adherent (1–10) and not adherent (>10). An overall internal consistency of α=0.83 has been reported.61

Self-management. To assess participant’s Self-Efficacy for Managing Chronic Diseases (SESG6), the German version of the 6-item scale will be used.62 The six items are rated with a 10-level Likert-type scale (1 ‘not at all confident’ to 10 ‘totally confident’). A mean score over at least four of the six items will be calculated, thus allowing a maximum of two missing item responses. SESG6 has been attested a high internal consistency measure of α=0.93.62

Technology proficiency, readiness and expectations. A standardised face-to-face interview prior to the use of Addison Care (‘pre-use interview’) will be performed to collect information on participant technology proficiency and readiness (seven items) in terms of experience with and use of general information and communication technologies (three items) as well as expectations regarding the upcoming use of the Addison Care technology (six items). These closed-ended questions were derived from empirical and theoretical literature31 32 63 and further adapted by the research team.

Sociodemographic and care provision variables. Sociodemographic and care-relevant variables will be collected by means of a short, standardised 9-item questionnaire. Age of participants, gender, living situation, place of residence in terms of urbanisation, care provision by relatives, and care provision by ambulant/mobile care service will be assessed using closed-ended questions. Information on documented primary diagnoses and existing additional chronic diseases will be collected using open-ended questions and categorised applying the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-11).64

Semistandardised research instruments

First experiences and encountered technical obstacles. A qualitative, semistructured brief telephone interview (‘mid-use interview’) with users after 1 week of Addison interaction will be conducted. Information about users’ experiences to date, as well as previous effort and encountered challenges in using the Addison Care technology will be collected. The user reports are to be recorded in an open-ended documentation sheet.

User experience, fulfilled expectations, perceived enabling conditions for use and technology’s social influence, and health behaviour. A comprehensive qualitative, semistructured, face-to-face interview will explore participants’ perspectives with reference to the fulfilled expectations after the use of Addison Care (‘postuse interview’), perceived enabling conditions and social influence in the use of the technology, as well as the participant’s experiences and adaptions of health behaviour. The interview guide questions on user experience are based on the respective literature on UX research,65 those on conditions and technology’s social influence along the main factors of the UTAUT model,31 32 and those on health behaviours were developed against the background of the Health Action Process Approach (HAPA).66 The interview will be audiorecorded and transcribed. With reference to the embedded mixed-methods approach, the four most striking individual ratings of the previously collected standardised UEQ will be thematised and perceived changes in secondary outcomes (functional status, quality of life, loneliness, depression, medication adherence) will be assessed using open-ended questions. To address their perspectives on the use of Addison Care, an optional topical block of guided questions will be operationalised.

Task performance scenario and think-aloud protocol. Finally, to gain insight into user thoughts, decision-making processes and how they experience the Addison Care technology, a structured observation with an accompanying think-aloud protocol will be applied.67 Participants will be asked to perform a set of specific tasks with Addison Care while verbally expressing their immediate thoughts, and explaining their reactions during system interaction. Task performance and participant comments will be documented using a structured observation sheet.

User safety and data management

During the 2-week study period, medical emergencies, acute deterioration in health or care needs, patients' feelings of insecurity, or hospital admissions will constitute reasons to end the participation early. Formal health services in the community setting will be informed about the use of Addison Care by their clients. Informal caregivers of the participants will be educated about Addison Care and are instructed to contact the support team in need of help (see figure 2).

Figure 2 provides detailed information on the different data retrieved during participants’ enrolment. Personal information of participants will be accessed by the support team only, who will monitor the dashboard and assist with any user problems. Dashboard access is granted by login data provided by Addison Care USA.

All data retrieved empirically (see figure 2) will be saved on study-specific computers during data collection and stored in password-protected folders on the support team storage after completed data collection. User engagement data will be stored on Addison Tablet PC for short periods of time being but regularly exported onto the server from the clinical dashboard and after the end of the pilot study transferred to study-specific computers. All personal data will be stored at a server in Berlin in Germany and encrypted. According to European Union General Data Protection Regulations, participants have the right to view all stored data or choose to delete their data at any given time as long as their data has not been anonymised by code yet.

Analysis

Various data will be organised and triangulated in data sets Quan 1–4 and Qual 1–3 (see figure 2) for analysis that fit the relevant phenomenon of interest. Final integration of overall results will take place on conclusion of the study37 and will be summarised with a joint display by using a mixed-methods matrix.68

Participants’ characteristics will be statistically described using information on sociodemographics, living and care provision, quality of life, health literacy, activities of daily living and medication adherence (Quan 1, figure 2).

A thematic content analysis of the qualitative data gained from interviews and observations in encounters 4 and 5 (see figure 2) will be performed, expanding the deductively developed code by inductive inputs.69 Deductive codes prepared from theoretical preconsiderations will include the concepts of user experience as well as usability. Coding strategy will separate the two phenomena during the coding process. User experience results will be produced by triangulating the results of the UEQ(Quan 3) as well as code system elements gathered in qualitative data sets (Qual 1, 2, 3). These three data sets will provide usability results after interviews are transcribed and coded. The codes will then be merged with the SUS results (Quan 3) to get a clear picture of obstacles and acceptance. User Engagement data will track usage events like logins, reminders and overall Addison-user-interaction over the 2-week usage period—resulting in data set Quan 4 (see figure 2). To facilitate the subsequent main study, deductive codes for the area of a feasibility study are also included in the coding strategy.70 All quantitative data will be analysed using common descriptive statistics.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical considerations

This pilot study was approved by the ethics committee of the German Society for Nursing Science (21-037) to ensure that the research is done in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and in line with the current legislation authority (see online supplemental file 3). The pilot study is registered in the German Clinical Trials Register (ID: DRKS00025992).

bmjopen-2022-062159supp003.pdf (216.6KB, pdf)

Dissemination

The results are intended to be published in peer-reviewed journals and disseminated through conference papers.

Overview

This protocol presents research that assesses the feasibility, acceptability, experience, engagement and usability of Addison Care—a health technology and virtual avatar for older persons with chronic diseases in their own home.

For this purpose, we culturally adopted the Addison Care technology and its functions (tutorial, medication management, testing vital signs) to explore participants’ acceptance and experiences of the health technology and the virtual avatar.

For older adults with chronic diseases, the overarching goal of self-management is to enhance their quality of life and maintain independence, all while supporting formal and informal caregivers.

The goal of this pilot study is to further our understanding of the potential issues and challenges that will be used as the foundations for a larger randomised control study.

One of the strengths of this study is the use of the health technology for a longer period of time and with real patients in a natural setting. Another strength lies in the cultural adaption of the health technology and its integration in a telecare framework. The integrated voice and touch interaction with the avatar ‘Addison’ should also contribute to improve the human–computer interaction.

Limitations

Possible limitations of the pilot study are the lack of results on usability or acceptance of the US American version of Addison Care that we can refer to. Cultural adaption and translation into German therefore might not be the only reason for a suboptimal user experience. Interviews allow to gain insight into this issue. The effectiveness of the extensive data collection process has to be proven as well as the recruitment process. The highly selective sample of the pilot study will diminish ethnical or socioeconomic diversity which will be introduced thoroughly in the study following the pilot. Within the qualitative branch of the mixed-methods study we seek sufficient richness of data but do not expect to achieve a data saturation. The study’s time line may be influenced by COVID-19 pandemic recruitment-wise as well as by pandemic regulations in Germany which cannot be foreseen at the current situation. Because we do not have an influence on the stability of the Internet connection, this could be another source of uncertainty. Finally, it is not the aim of the pilot study to show effects on the health status of the users. But the multiple instruments for testing health status-associated phenomena should provide adequacy to show such effects in a subsequent main study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Department of General Practice and Health Services Research, University Hospital Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany for access to the German version of the SESG6.

Footnotes

Contributors: SK, NaS, JD, PK, NN, JO, EŠ, SP, BM, MK, RE-M and BM participated in the design of the study protocol. SK, NaS, PK, JD, TK and EŠ drafted the protocol manuscript. MB, BH, BM, SP, AW, DL, AvdZ-N and JO critically revised and commented on its previous versions and the final version. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and agreed on submission.

Funding: This work is supported by Electronic Caregiver Inc, Las Cruces, New Mexico, USA (no grant number).

Competing interests: EŠ, BH and MB are employees of Electronic Caregiver Inc, Las Cruces, New Mexico, USA.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Maresova P, Javanmardi E, Barakovic S, et al. Consequences of chronic diseases and other limitations associated with old age - a scoping review. BMC Public Health 2019;19:1431. 10.1186/s12889-019-7762-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffith LE, Gilsing A, Mangin D, et al. Multimorbidity frameworks impact prevalence and relationships with Patient-Important outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67:1632–40. 10.1111/jgs.15921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R, et al. Aging with multimorbidity: a systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev 2011;10:430–9. 10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neil-Sztramko SE, Coletta G, Dobbins M, et al. Impact of the AGE-ON tablet training program on social isolation, loneliness, and attitudes toward technology in older adults: Single-Group pre-post study. JMIR Aging 2020;3:e18398. 10.2196/18398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wonggom P, Tongpeth J, Newman P, et al. Effectiveness of using avatar-based technology in patient education for the improvement of chronic disease knowledge and self-care behavior: a systematic review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep 2016;14:3–14. 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riegel B, Jaarsma T, Strömberg A. A middle-range theory of self-care of chronic illness. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 2012;35:194–204. 10.1097/ANS.0b013e318261b1ba [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banbury A, Nancarrow S, Dart J, et al. Adding value to remote monitoring: Co-design of a health literacy intervention for older people with chronic disease delivered by telehealth - The telehealth literacy project. Patient Educ Couns 2020;103:597–606. 10.1016/j.pec.2019.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheppard JP, Tucker KL, Davison WJ, et al. Self-Monitoring of blood pressure in patients with Hypertension-Related Multi-morbidity: systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. Am J Hypertens 2020;33:243–51. 10.1093/ajh/hpz182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bailey SC, Oramasionwu CU, Wolf MS. Rethinking adherence: a health literacy-informed model of medication self-management. J Health Commun 2013;18 Suppl 1:20–30. 10.1080/10810730.2013.825672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heapy AA, Higgins DM, Cervone D, et al. A systematic review of technology-assisted self-management interventions for chronic pain: looking across treatment modalities. Clin J Pain 2015;31:470–92. 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pfaeffli Dale L, Dobson R, Whittaker R, et al. The effectiveness of mobile-health behaviour change interventions for cardiovascular disease self-management: a systematic review. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016;23:801–17. 10.1177/2047487315613462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morton K, Dennison L, May C, et al. Using digital interventions for self-management of chronic physical health conditions: a meta-ethnography review of published studies. Patient Educ Couns 2017;100:616–35. 10.1016/j.pec.2016.10.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krick T, Huter K, Domhoff D, et al. Digital technology and nursing care: a scoping review on acceptance, effectiveness and efficiency studies of informal and formal care technologies. BMC Health Serv Res 2019;19:400. 10.1186/s12913-019-4238-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maresova P, Tomsone S, Lameski P, et al. Technological solutions for older people with Alzheimer's disease: review. Curr Alzheimer Res 2018;15:975–83. 10.2174/1567205015666180427124547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edmunds M, Tuckson R, Lewis J, et al. An emergent research and policy framework for telehealth. EGEMS 2017;5:1303. 10.13063/2327-9214.1303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hale TM, Jethwani K, Kandola MS, et al. A remote medication monitoring system for chronic heart failure patients to reduce readmissions: a Two-Arm randomized pilot study. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e91. 10.2196/jmir.5256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehta SJ, Hume E, Troxel AB, et al. Effect of remote monitoring on discharge to home, return to activity, and rehospitalization after hip and knee arthroplasty: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2028328. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.28328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su D, Michaud TL, Estabrooks P, et al. Diabetes management through remote patient monitoring: the importance of patient activation and engagement with the technology. Telemed J E Health 2019;25:952–9. 10.1089/tmj.2018.0205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoppe KK, Williams M, Thomas N, et al. Telehealth with remote blood pressure monitoring for postpartum hypertension: a prospective single-cohort feasibility study. Pregnancy Hypertens 2019;15:171–6. 10.1016/j.preghy.2018.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michaud TL, Siahpush M, Schwab RJ, et al. Remote patient monitoring and clinical outcomes for Postdischarge patients with type 2 diabetes. Popul Health Manag 2018;21:387–94. 10.1089/pop.2017.0175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foster MV, Sethares KA. Facilitators and barriers to the adoption of telehealth in older adults: an integrative review. Comput Inform Nurs 2014;32:523–33. 10.1097/CIN.0000000000000105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wonggom P, Kourbelis C, Newman P, et al. Effectiveness of avatar-based technology in patient education for improving chronic disease knowledge and self-care behavior: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep 2019;17:1101–29. 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bott N, Wexler S, Drury L, et al. A protocol-driven, bedside digital Conversational agent to support nurse teams and mitigate risks of hospitalization in older adults: case control pre-post study. J Med Internet Res 2019;21:e13440. 10.2196/13440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cassell J. Embodied Conversational agents: representation and intelligence in user interfaces. AI Magazine 2001;22:67. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gardiner P, Hempstead MB, Ring L, et al. Reaching women through health information technology: the Gabby preconception care system. Am J Health Promot 2013;27:eS11–20. 10.4278/ajhp.1200113-QUAN-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaked NA. Avatars and virtual agents - relationship interfaces for the elderly. Healthc Technol Lett 2017;4:83–7. 10.1049/htl.2017.0009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McLaughlin H. Service-user research in health and social care. Los Angeles: SAGE, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelders SM, van Zyl LE, Ludden GDS. The concept and components of engagement in different domains applied to eHealth: a systematic scoping review. Front Psychol 2020;11:926. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sousa VEC, Dunn Lopez K, E-Health TU. A systematic review of usability questionnaires. Appl Clin Inform 2017;8:470–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Vito Dabbs A, Myers BA, Mc Curry KR, et al. User-centered design and interactive health technologies for patients. Comput Inform Nurs 2009;27:175–83. 10.1097/NCN.0b013e31819f7c7c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Venkatesh V, Morris MG, Davis GB, et al. User acceptance of information technology: toward a unified view. Mis Quarterly 2003;27:425–78. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holden RJ, Karsh B-T. The technology acceptance model: its past and its future in health care. J Biomed Inform 2010;43:159–72. 10.1016/j.jbi.2009.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Czaja SJ, Charness N, Fisk AD, et al. Factors predicting the use of technology: findings from the center for research and education on aging and technology enhancement (create). Psychol Aging 2006;21:333–52. 10.1037/0882-7974.21.2.333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim BY, Lee J. Smart devices for older adults managing chronic disease: a scoping review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017;5:e69. 10.2196/mhealth.7141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoque R, Sorwar G. Understanding factors influencing the adoption of mHealth by the elderly: an extension of the UTAUT model. Int J Med Inform 2017;101:75–84. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2017.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.ECG . Electronic caregiver, 2020. Available: https://electroniccaregiver.com/

- 37.Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2 ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586. 10.1136/bmj.e7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vaughn J, Summers-Goeckerman E, Shaw RJ, et al. A protocol to assess feasibility, acceptability, and usability of mobile technology for symptom management in pediatric transplant patients. Nurs Res 2019;68:317–23. 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giunti G, Rivera-Romero O, Kool J, et al. Evaluation of more Stamina, a mobile APP for fatigue management in persons with multiple sclerosis: protocol for a feasibility, acceptability, and usability study. JMIR Res Protoc 2020;9:e18196. 10.2196/18196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laugwitz B, Held T, Schrepp M. Construction and evaluation of a user experience questionnaire 2008:63–76.

- 42.Schrepp M, Hinderks A, Thomaschewski Jörg. Design and evaluation of a short version of the user experience questionnaire (UEQ-S). International Journal of Interactive Multimedia and Artificial Intelligence 2017;4:103–8. 10.9781/ijimai.2017.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ruegenhagen E, Rummel B. System usability scale – jetzt auch auf Deutsch. SAP user experience community, 2015. Available: https://experience.sap.com/skillup/system-usability-scale-jetzt-auch-auf-deutsch/

- 44.Brooke J. SUS: a “quick and dirty'usability. Usability evaluation in industry 1996;189. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lewis JR. The system usability scale: past, present, and future. Int J Hum Comput Interact 2018;34:577–90. 10.1080/10447318.2018.1455307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taki S, Lymer S, Russell CG, et al. Assessing user engagement of an mHealth intervention: development and implementation of the growing healthy APP engagement index. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017;5:e89. 10.2196/mhealth.7236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lalmas M, O'Brien H, Yom-Tov E. Measuring user engagement. Synthesis lectures on information concepts, retrieval, and services. 6, 2014: 1–132. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Triberti S, Kelders SM, Gaggioli A. User engagement. In: Lv G-P, Kelders SM, Kip H, et al., eds. eHealth research, theory and development a multi-disciplinary approach. London: Routledge, 2018. : 271–89p.. [Google Scholar]

- 49.MDK -K-CG, 2020. Available: https://www.kcgeriatrie.de/Assessments_in_der_Geriatrie/Documents/iadl.pdf

- 50.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969;9:179–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deppermann K-M, Friedrich C, Herth F, et al. [Geriatric assessment and diagnosis in elderly patients]. Onkologie 2008;31 Suppl 3:6–14. 10.1159/000127563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ware J, Kosinski M, Dewey J. How to score and interpret single-item health status measures: a manual for users of the SF-Y" Health Survey; 2001.

- 53.Yiengprugsawan V, Kelly M, Tawatsupa B. SF-8TM Health Survey. In: Michalos AC, ed. Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2014: 5940–2. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, et al. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: results from two population-based studies. Res Aging 2004;26:655–72. 10.1177/0164027504268574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kantar P. SOEP-Core – 2017: Personenfragebogen, Stichproben A-L3. SOEP survey papers 563: series a. Berlin: DIW/SOEP; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hogrefe Verlag GmbH . Validity and reliability of a German version of the geriatric depression scale (GDS). Germany: Hogrefe Verlag GmbH & Co. KG; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA, Scale GD. Geriatric depression scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clinical Gerontologist: The Journal of Aging and Mental Health 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Allgaier A-K, Kramer D, Mergl R, et al. [Validity of the geriatric depression scale in nursing home residents: comparison of GDS-15, GDS-8, and GDS-4]. Psychiatr Prax 2011;38:280–6. 10.1055/s-0030-1266105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jongenelis K, Gerritsen DL, Pot AM, et al. Construction and validation of a patient- and user-friendly nursing home version of the geriatric depression scale. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007;22:837–42. 10.1002/gps.1748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Prell T, Grosskreutz J, Mendorf S, et al. Clusters of non-adherence to medication in neurological patients. Res Social Adm Pharm 2019;15:1419–24. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Franke G, Küch D, Jagla-Franke M. Die Erfassung der Medikamenten-Adhärenz bei Schmerzpatientinnen und -patienten 2019.

- 62.Freund T, Gensichen J, Goetz K, et al. Evaluating self-efficacy for managing chronic disease: psychometric properties of the six-item self-efficacy scale in Germany. J Eval Clin Pract 2013;19:39–43. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01764.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seifert A, Schelling H. Digitale Senioren. Nutzung von Informations- und Kommunikationstechnologien (IKT) durch Menschen ab 65 Jahren in Der Schweiz Im Jahr 2015. Zürich: Pro Senectute, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 64.World Health Organization . International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th revision), 2018. Available: https://icd.who.int/en/

- 65.Goodman E, Kuniavsky M, Moed A. Observing the user experience : a practitioner’s guide to user research. Waltham, MA: Morgan Kaufmann, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schwarzer R, Fleig L. Von der Risikowahrnehmung zur Änderung des Gesundheitsverhaltens. Zentralblatt für Arbeitsmedizin, Arbeitsschutz und Ergonomie 2014;64:338–41. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jaspers MWM, Steen T, van den Bos C, et al. The think aloud method: a guide to user interface design. Int J Med Inform 2004;73:781–95. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2004.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.O'Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. Three techniques for integrating data in mixed methods studies. BMJ 2010;341:c4587. 10.1136/bmj.c4587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mayring P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Grundlagen und Techniken. 12. ed. Weinheim/Basel: Beltz Verlag, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bowen DJ, Kreuter M, Spring B, et al. How we design feasibility studies. Am J Prev Med 2009;36:452–7. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-062159supp001.pdf (140.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-062159supp002.pdf (166.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-062159supp003.pdf (216.6KB, pdf)