Abstract

The bacterial nitric oxide reductase (NOR) is a divergent member of the family of respiratory heme-copper oxidases. It differs from other family members in that it contains an FeB–heme-Fe dinuclear catalytic center rather than a CuB–heme-Fe center and in that it does not pump protons. Several glutamate residues are conserved in NORs but are absent in other heme-copper oxidases. To facilitate mutagenesis-based studies of these residues in Paracoccus denitrificans NOR, we developed two expression systems that enable inactive or poorly active NOR to be expressed, characterized in vivo, and purified. These are (i) a homologous system utilizing the cycA promoter to drive aerobic expression of NOR in P. denitrificans and (ii) a heterologous system which provides the first example of the expression of an integral-membrane cytochrome bc complex in Escherichia coli. Alanine substitutions for three of the conserved glutamate residues (E125, E198, and E202) were introduced into NOR, and the proteins were expressed in P. denitrificans and E. coli. Characterization in intact cells and membranes has demonstrated that two of the glutamates are essential for normal levels of NOR activity: E125, which is predicted to be on the periplasmic surface close to helix IV, and E198, which is predicted to lie in the middle of transmembrane helix VI. The subsequent purification and spectroscopic characterization of these enzymes established that they are stable and have a wild-type cofactor composition. Possible roles for these glutamates in proton uptake and the chemistry of NO reduction at the active site are discussed.

Many species of bacteria contain a nitric oxide reductase (NOR) which catalyzes the reaction 2NO + 2e− + 2H+ → N2O + H2O (21, 26). The reduction of NO serves as a key step in denitrification (in which N-oxyanions and N-oxides are used as respiratory electron acceptors) and as a way of removing cytotoxic NO. The NOR of Paracoccus denitrificans is an integral-membrane protein that normally purifies as two-subunit complex NorCB (10–12, 15). NorC is a monoheme membrane-anchored c-type cytochrome. NorB is a divergent member of the family of catalytic subunits from respiratory heme-copper oxidases (HCOs) (21, 26). Typical features of catalytic subunits of the HCOs are a core functional unit of 12 transmembrane helices, which bind a magnetically isolated electron-transferring heme, and a dinuclear active site, formed by a second heme magnetically coupled to a copper ion (CuB). Seven conserved histidine residues, responsible for ligating the three redox-active metal centers, can be identified in helices II, VI, VII, and X. Each of these histidine residues is conserved in the NorB subunit of NOR (21, 26, 29).

The key difference between the catalytic subunit of NOR and those of other HCOs is the composition of the dinuclear center. In NorB there is a nonheme iron (FeB) at the active site rather than copper (CuB) (13), possibly because, under the highly reducing conditions of the primordial biosphere, ferrous ions were more readily available than insoluble cuprous ions to the ancestral enzyme from which both NOR and HCOs evolved. Since it is likely that denitrification preceded aerobic respiration in the biosphere, the primary function of the ancestral oxidase was probably the reduction of NO. Consequently, a key step in the evolution of aerobic life on earth may have been the replacement of iron by copper in the ancestral oxidase, allowing it to reduce oxygen more efficiently (4). Recent biochemical studies have begun to reveal additional differences in the catalytic pockets of NorB and HCOs. For example, resonance Raman spectroscopy of the CO adduct of reduced NOR has suggested that the catalytic pocket of NorB is more negatively charged than those of HCOs (18). In addition, redox potentiometry has indicated a midpoint potential of high-spin heme b3 that is around 200 mV lower than that of high-spin heme a3 of cytochrome oxidase (11). This may serve to prevent formation of a dead-end Fe(II)-NO complex during the catalytic cycle.

High-resolution X-ray analysis of the crystal structures of cytochrome c oxidase, together with site-directed mutagenesis, have led to the identification of amino acid residues that are important in the delivery of chemical and “pumped” protons from the cytoplasm to the dinuclear center during the catalytic cycle and that define the so-called K and D channels (1, 16, 32). The absence of these residues from NOR suggests that the enzyme is not a proton pump and that it takes the protons required for reduction of NO from the periplasm, and there is experimental evidence consistent with this idea (2, 3, 22). Hence, evolution of the ancestral NO-reducing enzyme into an HCO involved the acquisition of not only a Cu-containing dinuclear center but also a proton pumping mechanism. The primary structures of NorB subunits reveal a number of conserved glutamic acid residues in putative transmembrane helices and periplasmic loops, which are absent in other HCOs (29). These are (P. denitrificans numbering) E122 in the helix III/IV loop, E125 at the periplasmic surface of helix IV, E198 and E202, located one and two helical turns, respectively, below the putative FeB ligand (His194) in helix VI, and E267, located in the middle of helix VIII. This sequence conservation, together with the energetic cost of placing a charged residue in the lipid bilayer, suggests a functional importance for these glutamates. Possible roles include FeB binding, modulation of the charge of the catalytic pocket or of the catalytic heme redox potential, and mediation of proton movements.

In order to investigate the role of conserved residues in bacterial NORs, there has been a need to develop suitable expression systems for catalytically inactive enzymes. Heterologous and homologous expression systems would allow assessment of the physiological consequences of mutations in NorB, as well as the production of pure enzyme for structure-function studies. We have developed two such systems that meet these criteria, and the characterization of enzymes with E125A, E198A, and E202A substitutions in intact cells, membrane fractions, and purified preparations is reported. The results demonstrate that E125 and E198 are not required for the assembly of a stable holo-NorCB enzyme complex but have a critical role in NO reduction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of a system for homologous expression of P. denitrificans norCB.

Plasmid pKPD1 is a clone of the entire cycA (P. denitrificans cytochrome c550) gene and promoter region in expression vector pKK223-3, which has been modified to contain a unique SalI site (25). A 325-bp SalI-EcoRI fragment containing the cycA promoter region was excised from pKPD1 and cloned into pUC18 to yield pGB1. A 7.8-kb HindIII fragment containing the norCBQDEF operon was excised from pEG8HI (a gift from R. J. M. van Spanning, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and cloned into pUC18 to yield pNORHC. There are two BsaBI restriction sites in the cycA promoter region in pGB1. The first site cuts 1 bp downstream of the ATG start codon of the cycA gene, and the second cuts 6 bp downstream of the first. The norCBQDEF coding region, minus the norC promoter, was excised from pNORHC on a blunt-ended 5.7-kb SanDI-HindIII fragment and ligated into pGB1 that had been digested with BsaBI. Clones containing the 5.7-kb insert in the correct orientation were selected and designated pCYCNOR1. The cycA-nor fusion was excised from pCYCNOR1 on a 6.0-kb EcoRI-PstI fragment and cloned into pBluescript KS+. Recombinant clones were designated pCYCNOR2. The 6.0-kb cycA-nor fusion was excised from pCYCNOR2 by digestion with XbaI and HindIII and cloned into broad-host-range vector pEG400 to yield pCYCNOR3, generating a cycA-nor fusion that could be propagated in P. denitrificans.

Construction of a norB::Ω-Km mutant.

The 4-kb BglII fragment containing the nor operon from pNORHC was cloned into the BamHI site of pBluescript KS+ to yield pBg14. A 2.2-kb BamHI Ω-Km fragment was excised from pHP45Ω-Km and cloned into the unique BamHI site in pBg14, which is in norB, to generate pBglkm. The insert from pBglkm was cloned as a 6.1-kb XbaI-EcoRI fragment into pLITMUS28 to yield pLitBglkm, which was then digested with XbaI and SpeI, and the 6.1-kb fragment was cloned into the XbaI site of pUC18. A correctly oriented clone was selected, and the plasmid was named pUCBglkm. These cloning steps resulted in the location of the entire 6.1-kb DNA fragment containing the Ω-Km cassette and flanking DNA from the nor coding sequence on a single EcoRI fragment. This fragment was introduced into the suicide vector pRVS1 to yield pRVSBglkm. Escherichia coli S17.1 (pRVSBglkm) and P. denitrificans 1222 were then used in biparental filter matings on L agar (16 h at 30°C). Cells were removed from the filter by resuspension in L broth and plated onto L agar (36 h at 37°C) containing rifampin, spectinomycin, kanamycin, and X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside). Streptomycin-sensitive, kanamycin-resistant white colonies were designated P. denitrificans GB1 (genotype norB::Ω-Km). The presence of the 2.1-kb Ω cartridge in norB was confirmed by direct genomic PCR analysis.

Directed mutagenesis of norB.

pCYCNOR3 was digested with XbaI, which cuts upstream of the cycA promoter, and XhoI, which cuts in the middle of norB. The 1.6-kb fragment (which contains the E125, E198, and E202 codons) was ligated into XbaI/XhoI-digested pBluescript KS+ to generate pNORXX16, which was transformed into E. coli DH5α. PCRs were set up with complementary primer pairs suitable for introduction of the E125A (GAA → GCG), E198A (GAG → GCC), E202A (GAG → GCC), and E198A plus E202A mutations. The following silent restriction sites were incorporated into the primers to allow for easy screening for mutations by restriction digests: E125A, FspI; E198A, SacI; E202A, ApaI; E198A plus E202A, NaeI and ApaI. The template for PCR was pNORXX16, and reactions were performed using the Quickchange (E198) or ExSite mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). In the final stage of the protocol, E. coli XL1-Blue transformed in each of the four ligation reactions was spread onto L agar plates supplemented with 100 μg of ampicillin/ml. Potential mutants were selected and sequenced to establish their authenticity. The plasmids carrying codons leading to the E125A, E198A, E202A, and E198A plus E202A mutations were designated pNOR125A, pNOR198A, pNOR202A, and pNOR198202A, respectively. The 1.6-kb XbaI-XhoI fragments from the four mutant plasmids were cloned into XbaI/XhoI-digested pCYCNOR. The resulting plasmids were then digested with FspI (E125A), SacI (E198A), or ApaI (E202A and E198A plus E202A), as appropriate. All clones were found to have the expected restriction pattern. These plasmids were designated p125CNOR, p198CNOR, p202CNOR, and p198202CNOR and were introduced into P. denitrificans GB1 by triparental matings with the corresponding E. coli DH5α transformants and E. coli JM83 harboring helper plasmid pRK2013.

Construction of pNOREX used for the expression of the norCBQDEF operon in E. coli.

The 6.0-kb XbaI-HindIII fragment, containing the cycA-nor fusion from pCYCNOR3, was cloned into pUC18 to yield pNOREX, which has the nor operon in the correct orientation to allow expression from the lac promoter. pNOREX was found to be unstable in E. coli DH5α, so strain JM109 (lacIq), in which pNOREX was more stable, was used as the host. Similar procedures were used to construct p125EX, p198EX, p202EX, and p198202EX, using the 6.0-kb XbaI-HindIII fragments from p125CNOR, p198CNOR, p202CNOR, and p198202CNOR.

Anaerobic growth of P. denitrificans.

P. denitrificans strains were grown aerobically at 37°C in 50 ml of L broth supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics. For each strain, a 500-ml bottle of succinate-nitrate minimal medium, supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics, was inoculated with a 1% volume from the L broth cultures. The bottle was then sealed, and the cells were mixed thoroughly by inversion. The starting optical density at 610 nm (OD610) was determined, and, to avoid further introduction of oxygen during anaerobic growth, the contents of the inoculated bottles were aliquoted into 25-ml bottles. Each 25-ml bottle was then tightly sealed and incubated at 30°C. A single bottle was opened for each time point in the growth curve and the OD610 was recorded. Also, at each time point, 1.5 ml of cells was centrifuged for 5 min at 13,000 rpm in a bench top microcentrifuge. The culture supernatant was then assayed colorimetrically for nitrite.

Analytical methodologies.

NO reductase activity was measured amperometrically using a Clark-type electrode, essentially as previously described (10, 13), but using ascorbate, phenazine methosulfate, and horse heart cytochrome c as the electron donor/mediator system. Cytochrome oxidase activity was measured spectrophotometrically by monitoring the NOR-dependent oxidation kinetics of reduced horse heart cytochrome c in aerated cuvettes. Protein levels were estimated using the bicinchoninic acid method with bovine serum albumin as a standard. The stain for heme-linked peroxidase activity, which is specific for c-type cytochromes, was as previously described (20). The rates given in Tables 2 and 3 are representative data taken from samples prepared from at least two independent cultures.

TABLE 2.

NOR activities of membranes prepared from P. denitrificans GB1 grown under different conditions with different plasmids

| Plasmid present | NOR expresseda | Growth condition | NOR activity (nmol · mg of protein−1 · min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | None | O2, succinate | <5 |

| None | None | O2, methylamine | <5 |

| None | None | O2, L broth | <5 |

| pCYCNOR3 | WT | O2, succinate | 23 |

| pCYCNOR3 | WT | O2, methylamine | 230 |

| pCYCNOR3 | WT | O2, L broth | 300 |

| pCYCNOR3 | WT | Anaerobic, succinate + nitrate | 440 |

| p125CNOR | E125A | O2, methylamine | <5 |

| p198CNOR | E198A | O2, methylamine | <5 |

| P202CNOR | E202A | O2, methylamine | 200 |

| p198202CNOR | E198A/E202A | O2, methylamine | <5 |

| p125CNOR | E125A | O2, L broth | <5 |

| p198CNOR | E198A | O2, L broth | <5 |

| P202CNOR | E202A | O2, L broth | 210 |

| p198202CNOR | E198A/E202A | O2, L broth | <5 |

WT, wild type; E125A, NORE125A (similar for E198A and E202A).

TABLE 3.

NOR and oxidase activities in membranes prepared from E. coli JM109 expressing wild-type or mutant forms of NOR

| Plasmids present | NOR expresseda | NOR activity (nmol of NO mg of protein−1 min−1) | Oxidase activity (nmol of O mg of protein−1 min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | None | <5 | |

| pEC86 | None | <5 | |

| pEC86, pNOREX | Wild type | 470 | 40 |

| pEC86, p125EX | E125A | 20 | 2 |

| pEC86, p198EX | E198A | <5 | <1 |

| pEC86, p202EX | E202A | 140 | 30 |

| pEC86, p198202EX | E198A/E202A | <5 | <1 |

E125A, NORE125A (similar for E198A and E202A).

EPR, UV-Vis, and mediated redox potentiometry.

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra were recorded using an ER-200D X-band spectrometer (Bruker Spectrospin) interfaced to an ESP1600 computer and fitted with a liquid-helium flow cryostat (ESR-9; Oxford Instruments). UV-visible (UV-Vis) spectra were collected using an Aminco SLM DW2000 spectrophotometer. Samples for UV-Vis spectra and redox titrations were at 25°C in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). Mediated redox potentiometry was performed as previously described (11). Dithionite and ferricyanide were used as the reductant and oxidant, respectively. Redox mediators were phenazine methosulfate, phenazine ethosulfate, diaminodurene, 4-hydroxynaphthoquinone, 5-anthraquinone 2-sulfonate, 6-anthraquinone 2,6-disulfonate, and benzyl viologen (at a final concentration of 20 μM). Quinhydrone was used as a redox standard (Em,7.0 = +295 mV). All potentials quoted are with respect to that of the normal hydrogen electrode. Redox titrations were fitted using a customized program in table-curve 2D (Jandel Scientific) allowing estimates of Em and multiple independent n = 1 components to float as appropriate (11). The error for each Em was estimated from multiple titrations to be ±20 mV.

Purification of NOR.

Recombinant NOR was purified from 15-liter cultures of E. coli grown in L broth in an aerated bioreactor. When the culture density reached an OD650 of 0.4, the culture was induced for 4 h with 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside). Cells were then harvested by cross-flow filtration and broken in a French press. Membranes were recovered by centrifugation and suspended in 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6)–50 mM NaCl–1 mM EDTA, sonicated, and solubilized in 1% (wt/vol) n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (4°C for 1 h). The sample was then centrifuged at 45,000 rpm in a Beckman 70Ti rotor for 1 h at 4°C. The supernatant was immediately diluted 10-fold with buffer to avoid precipitation of the protein. The protein sample was then purified using Q-Sepharose (0 to 500 mM NaCl gradient) and Cu-IMAC (2.5 to 50 mM imidazole gradient) chromatographies, as previously described (13). The elution buffer was 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)–0.1% dodecyl maltoside. Fractions containing NOR were identified spectroscopically.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Characterization of engineered NOR in intact cells and membrane fractions of P. denitrificans.

The utility of pCYCNOR3 (Table 1) for nor expression in P. denitrificans depends on its ability to express norCB under growth conditions for which NOR is not essential. Thus, the expression of an engineered norCB that encodes an inactive or poorly active NOR is possible. The nor promoter is only active under anaerobic conditions and is dependent on the presence of NO (14, 17, 27). However, in pCYCNOR3 the nor genes are transcribed from the P. denitrificans cycA promoter (from the cytochrome c550 gene), which is known to be active under some aerobic growth conditions (20, 25). P. denitrificans strains GB1 (norB::Ω) and GB1(pCYCNOR3) were grown under a range of conditions, and the NOR activities of the membrane fractions were determined. GB1 displayed no detectable NOR activity under any of the growth conditions tested (Table 2). By contrast, NOR activity was detectable in GB1(pCYCNOR3) under all growth conditions tested. Activity was lowest following aerobic growth on succinate medium and was an order of magnitude higher in membranes prepared from cells grown aerobically on methylamine, anaerobically on succinate-nitrate medium, or aerobically to late stationary phase on L broth (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli DH5α | supE44 Δ(lacU169) (ø80 lacZΔM15) recA endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 relA1 deoR | Gibco-BRL |

| E. coli JM109 | recA endA gyrA thi hsdR supE relA Δ(lac-proAB) [F′ traD proAB+lacIqZΔM15] | Gibco-BRL |

| E. coli S17-1 | thi pro hsdR hsdM+ recA; chromosomal insertion of RP4-2 (Tc::Mu Km::Tn7); Strr | 24 |

| P. denitrificans 1222 | Restriction modification deficient | 6 |

| P. denitrificans GB1 | 1222 norB::Ω-Km | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBluescript II KS+ | Cloning vector; Ampr | Stratagene |

| pRVS1 | pBR322-derived suicide vector | 28 |

| pHP45Ω-Km | Plasmid carrying Ω-Km; Kanr | 7 |

| pEG400 | Broad-host-range cloning vector | 9 |

| pEC86 | Plasmid carrying ccm gene cluster | 19 |

| pUC18 | Cloning vector; Ampr | Roche |

| pLITMUS28 | Cloning vector; Ampr | New England Biolabs |

| pKK223-3 | Derivative of pKK223 with unique SalI site | |

| pKPD1 | P. denitrificans cycA gene and promoter region cloned into pKK223-3 | 25 |

| pGB1 | 325-bp SalI-EcoRI fragment containing the cycA promoter from pKPD1 in pUC18 | This work |

| pEG8H1 | P. denitrificans nor operon in pEG400 | R. van Spanning |

| pNORHC | 7.8-kb HindIII fragment from pEG9HI containing norCBQDEF cloned in pUC18 | This work |

| pCYCNOR1 | 5.7-kb SanDI-HindIII fragment from pNORHC cloned into pGB1 | This work |

| pCYCNOR2 | 6-kb EcoR1-PstI fragment from pCYCNOR1 containing the cycA-nor fusion cloned in pBluescript KS+ | This work |

| pCYCNOR3 | 6-kb XbaI-HindIII fragment containing cycA-nor fusion cloned in pEG400 | This work |

| pBg14 | 4-kb BglII fragment from pNORHC cloned in pBluescript KS+ | This work |

| pBglkm | 2.2-kb BamHI Ω-Km fragment from pHP45Ω-Km cloned into norB gene of Bg14 | This work |

| pLITBglkm | 6.1-kb XbaI-EcoRI norCB::ΩQEDF insert from pBglkm cloned into pLITMUS28 | This work |

| pUCBglkm | 6.1-kb XbaI-SpeI norCB::ΩQEDF insert from pLITBglkm cloned in pUC18 | This work |

| pRVSBglkm | 6.1-kb EcoRI norCB::ΩQEDF insert from pUCBglkm cloned in pRVS1 | This work |

| pNOREX | 6.1-kb XbaI-HindIII cycA-nor fusion from pCYCNOR cloned in pUC18 | This work |

| pNORXX16 | 1.6-kb XbaI-XhoI nor fragment from pCYCNOR clone into pBluescript KS+ | This work |

| pNOR125A | E125A NorB mutation in pNORXX16 | This work |

| pNOR198A | E198A NorB mutation in pNORXX16 | This work |

| pNOR202A | E202A NorB mutation in pNORXX16 | This work |

| pNOR198202A | E198A, E202A NorB mutations in pNORXX16 | This work |

| p125CNOR | E125A NorB mutation in pCYCNOR | This work |

| P198CNOR | E198A NorB mutation in pCYCNOR | This work |

| p202CNOR | E202A NorB mutation in pCYCNOR | This work |

| p198202CNOR | E198A, E202A NorB mutations in pCYCNOR | This work |

| p125EX | E125A NorB mutation in pNOREX | This work |

| p198EX | E198A NorB mutation in pNOREX | This work |

| p202EX | E202A NorB mutation in pNOREX | This work |

| p198202EX | E198A, E202A NorB mutations in pNOREX | This work |

Strr, streptomycin resistant; Kanr, kanamycin resistant; Ampr, ampicillin resistant.

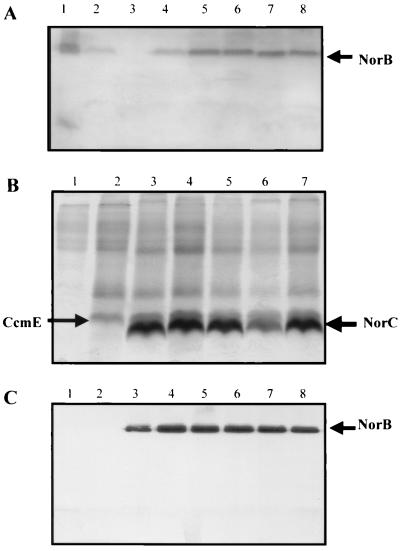

These expression studies demonstrated that the cycA promoter is capable of driving expression of the nor operon under growth conditions for which NOR is nonessential. Having established this, mutations leading to E125A, E198A, E202A, and E198A plus E202A substitutions were introduced into the norB gene (Table 1) and the engineered enzymes were expressed in aerobic methylamine-grown cultures of GB1 (norB::Ω). There was no detectable NOR activity in membranes from the strains expressing enzymes with the E125A, E198A, and E198A plus E202A substitutions and intermediate levels of activity in membranes from the strain expressing NOR with the E202A substitution (Table 2). Immunochemistry was employed to assess the expression of the catalytic NorB subunit. Membrane fractions were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) alongside a sample of purified NOR. The gel was Western blotted and then probed with an anti-NorB antibody. A strongly reactive band that corresponded to NorB could be observed in the lane containing purified NOR. This protein was absent from norB::Ω mutant GB1 but present in GB1(pCYCNOR3) (Fig. 1A). The same band was also present in GB1(p125CNOR), GB1(p198CNOR), GB1(p202CNOR), and GB1(p198202CNOR). Although there was some sample-to-sample heterogeneity, analysis of three independent membrane preparations suggested that levels of expression of the NorB polypeptide in all of the strains carrying either the wild-type or mutant forms of the norB gene were similar. This confirmed that NorB biosynthesis and stability were similar for all of the engineered enzymes and so could not account for the pronounced differences in NOR activity observed in membranes expressing these enzymes.

FIG. 1.

Heme-stained SDS-PAGE gel and anti-NorB-probed Western blot of membrane fractions from P. denitrificans and E. coli. (A) Anti-NorB-probed Western blot of P. denitrificans membranes. Membranes were prepared from cells grown aerobically on L broth and solubilized in 1% dodecyl maltoside. Fifteen microliters (5 to 10 μg of protein) of each sample was loaded onto the SDS-PAGE gel, which was subsequently used for the Western blotting. Lane 1, purified NorCB; lane 2, strain 1222; lane 3, GB1; lane 4, GB1(pCYCNOR3); lane 5, GB1(p125CNOR); lane 6, GB1(p198CNOR); lane 7, GB1(p202CNOR); lane 8, GB1(p198202CNOR). (B) Heme-stained gel of E. coli membranes. Lane 1, JM109; lane 2, JM109(pEC86); lane 3, JM109(pNOREX, pEC86); lane 4, JM109(p125EX, pEC86); lane 5, JM109(p198EX, pEC86); lane 6, JM109(p202EX, pEC86); lane 7, JM109(p198202EX, pEC86). (C) Anti-NorB-probed Western blot of E. coli membranes. Lane 1, JM109; lane 2, JM109(pEC86); lane 3, JM109(pNOREX, pEC86); lane 4, JM109(p125EX, pEC86); lane 5, JM109(p198EX, pEC86); lane 6, JM109(p202EX, pEC86); lane 7, JM109(p198202EX, pEC86); lane 8, purified NorCB. Membranes were solubilized in 1% dodecyl maltoside, and 15 μl (5 to 10 μg of protein) was loaded into each well of the SDS-PAGE gels.

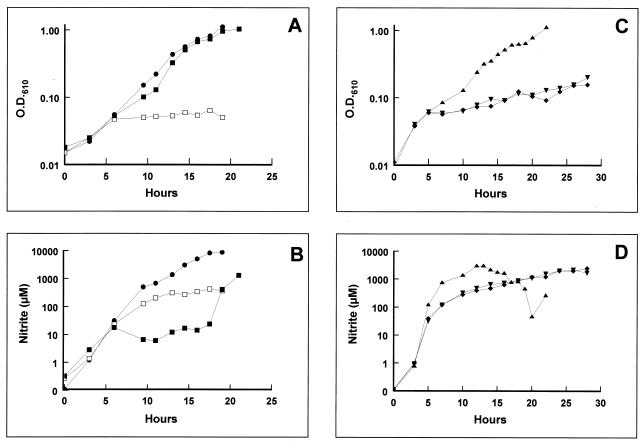

To assess the physiological competence of the engineered NORs, P. denitrificans 1222, GB1, GB1(pCYCNOR3), GB1(p125CNOR), GB1(p198CNOR), and GB1(p202CNOR) were cultured under anaerobic denitrifying conditions with succinate as the carbon source, ammonium as the nitrogen source, and nitrate as a respiratory electron acceptor (Fig. 2A). During the first 6 h of anaerobic incubation, strains 1222 (wild type) and GB1 (norB::Ω) exhibited similar growth kinetics. This growth period was accompanied by a rapid accumulation of nitrite in the culture supernatant, which could be attributed to the respiratory reduction of nitrate to nitrite (Fig. 2B). After this period, growth of GB1 was almost completely attenuated (Fig. 2A), although a net accumulation of nitrite continued throughout the 20-h duration of the growth experiment (Fig. 1B). It is likely that after 6 h some of the nitrite initially produced by the culture was reduced to NO by the cytochrome cd1 nitrite reductase. The NO cannot be further reduced in the absence of NOR and so inhibits growth. Introduction of the nor-expressing clone pCYCNOR3 into GB1 restored the wild-type capacity for anaerobic denitrifying growth (Fig. 2A). Nitrogen gas bubbles could be observed during growth of both 1222 and GB1(pCYCNOR3), indicative of complete denitrification. However, there were significant differences in the nitrite extrusion profiles during growth of strains 1222 and GB1(pCYCNOR3). The wild-type strain accumulated nitrite in the growth medium throughout growth, but in GB1(pCYCNOR3) the nitrite reached a steady concentration (7 to 12 mM) between 6 and 18 h, increasing rapidly again thereafter (Fig. 2B). These differences may be a consequence of expressing nor from the cycA promoter. The nor promoter is coregulated with the nitrite reductase genes by the NO-responsive activator NNR (14, 17, 27, 29); this coordinate regulation is lost in the recombinant expression system.

FIG. 2.

Growth curves of P. denitrificans 1222 (●), GB1 (□), GB1(pCYCNOR3) (■), GB1(p125CNOR) (▾), GB1(p198CNOR) (⧫), and GB1(p202CNOR) (▴). Cultures were grown under anaerobic denitrifying conditions. (A) Growth kinetics, monitored via OD610, of 1222, GB1, and GB1(pCYCNOR3). (B) Nitrite accumulation kinetics during growth of 1222, GB1, and GB1(pCYCNOR3). (C) Growth kinetics, monitored via OD610, of GB1(p125CNOR), GB1(p198CNOR), and GB1(p202CNOR). (D) Nitrite accumulation kinetics during growth of GB1(p125CNOR), GB1(p198CNOR), and GB1(p202CNOR).

Strains GB1(p125CNOR) and GB1(p198CNOR) resembled GB1 in that they were able to grow during the first 6 h after inoculation (Fig. 2C) by virtue of the energy-conserving reduction of nitrate to nitrite, which accumulated in the culture supernatant (Fig. 2D). Thereafter, no further growth was apparent, presumably as a result of the failure to reduce the NO derived from nitrite reduction at sufficiently rapid rates to prevent toxicity. GB1 expressing NORE202A showed almost complete complementation (Fig. 2C). In all three cases the growth phenotypes reflect the relative levels of NOR activity observed in membrane fractions prepared from the methylamine-grown cells (Table 2).

Characterization of engineered P. denitrificans NOR in intact cells and subcellular fractions of E. coli.

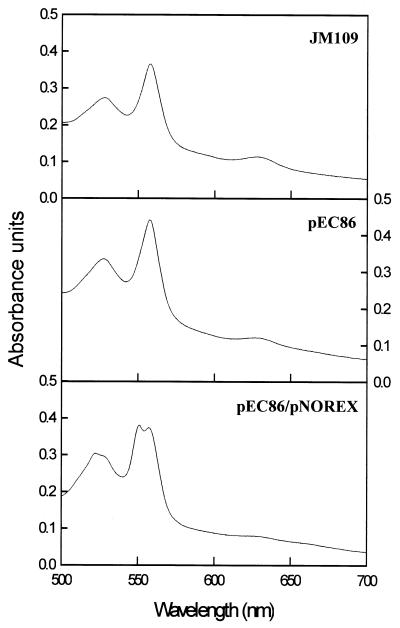

Homologous expression of norCB proved essential for assessing the physiological competence of engineered NORs and for establishing that they were synthesized and stable. To provide large quantities of NOR for purification and spectroscopic analysis, a heterologous nor expression system utilizing the IPTG-inducible lacZ promoter of pUC18 in E. coli JM109 was developed. To facilitate expression, E. coli was cotransformed with pNOREX (Table 1) and pEC86, which contains the cytochrome c assembly (ccm) genes (19, 22). Dithionite-reduced UV-Vis spectra revealed differences between JM109, JM109(pEC86), and JM109(pEC86/pNOREX) membrane extracts. The reduced spectrum of detergent-solubilized membranes from JM109 shows a peak at approximately 560 nm typical of E. coli respiratory complexes containing b-type heme, such as the cytochrome bo3 oxidase and the formate dehydrogenase (Fig. 3). There is no indication of the presence of any c-type cytochromes, since there is no absorption peak at around 550 nm. The JM109(pEC86) extract shows an overall increase in the intensity of the spectrum and a slight shift of the peak towards 558 nm. This is probably due to the expression of the CcmE protein (from pEC86), which is known to absorb maximally at 558 nm when in the reduced form (22). The clearest spectral changes occurred in JM109(pEC86/pNOREX), where two peaks with almost equal intensities at approximately 550 and 558 nm can be resolved (Fig. 3). The peak at 550 nm is indicative of the presence of a c-type cytochrome and is likely to arise from NorC. The intensity at 558 nm is likely to arise from a combination of CcmE, various respiratory complexes, and also the b hemes of NorB.

FIG. 3.

UV-Vis absorption spectra of membranes prepared from E. coli JM109, JM109(pEC86), and JM109(pEC86/pNOREX). The strains were grown aerobically in 500-ml Luria-Bertani medium (in 2.5-liter baffled flasks) and induced at an OD610 of 0.4 with 1 mM IPTG. Cells were harvested 4 h after induction, and membranes were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Spectra were acquired from suspensions of 100 μg of membranes per ml.

Detergent-solubilized membrane extracts of JM109, JM109(pEC86), and JM109(pEC86/pNOREX) were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and the gel was stained for heme-dependent peroxidase activity to enable detection of c-type cytochromes. The JM109 membrane extract shows very little covalently attached heme (Fig. 1B). The faint high-molecular-weight bands are thought to arise from noncovalently bound b heme, which had not fully dissociated from some of the respiratory complexes. The JM109(pEC86) membrane extract contained a band at 19 kDa, which stained strongly for heme and which is likely to be CcmE (19, 22). In addition this extract contained a ≈30-kDa heme-staining polypeptide which is likely to arise from an endogenous E. coli protein, since it is also present in the JM109 membrane extract, albeit at extremely low levels. The membrane extract from cells containing both pEC86 and pNOREX has an additional 18-kDa heme-staining polypeptide that migrated slightly faster than the CcmE polypeptide. The molecular mass of this heme-staining polypeptide is consistent with it being NorC. To confirm the presence of NorB, all three membrane extracts resolved by SDS-PAGE were Western-blotted and probed with an anti-P. denitrificans NorB antibody (Fig. 1C). There was no cross-reacting band in the lanes loaded with JM109 and JM109(pEC86) extracts. However, a single strongly cross-reacting band that migrated to the same position as the NorB polypeptide of purified NOR could be clearly identified in the JM109(pEC86/pNOREX) extract. In agreement with the apparent expression pattern of NorC and NorB from the heme-staining and immunochemical analysis, membranes prepared from JM109 and JM109(pEC86) both displayed no detectable NOR activity, whereas JM109(pEC86/pNOREX) membranes displayed significant activity (Table 3). These data confirmed that P. denitrificans NOR was expressed and active in E. coli JM109 containing pNOREX and the ccm coexpression plasmid pEC86. This represents the first example of the expression of a large integral-membrane respiratory cytochrome bc complex in E. coli. The coexpression of the ccm genes from pEC86 was critical to the success of this strategy since the NorC subunit did not assemble efficiently in its absence (data not shown). It should also be noted that pNOREX contained the whole norCBQDEF operon. Attempts to express NOR in the absence of the norQDEF genes were unsuccessful, but a systematic study of the role of each of these genes in the assembly and/or stability of NOR was not undertaken at this stage.

To assess the activity of the engineered NORs in E. coli, p125EX, p198EX, p202EX, and p198202EX were all introduced into JM109 with pEC86. Solubilized membrane extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and the gel was stained for covalently bound heme (Fig. 1B). The 18-kDa polypeptide identified as NorC was present in all of the extracts. The presence of NorB was confirmed using the NorB antibodies (Fig. 1C). Membrane extracts of the E. coli strains expressing engineered NorB were assayed for NOR activity (Table 3). The activities followed a pattern similar to those obtained for the mutant enzymes expressed in P. denitrificans; no activity was detected for the E198A mutant, and the E202A mutant had the highest activity. The only major discrepancy was that the E125A mutant had no detectable NOR activity when expressed in P. denitrificans but did show a very low (5% of wild-type) activity when expressed in E. coli. This residual activity may have been too low to detect in P. denitrificans as a consequence of the background NOR activity of cytochrome oxidases.

It was also possible to determine whether the P. denitrificans NOR expressed in E. coli possessed an oxidase activity. This assay had previously only been possible with purified enzyme from P. denitrificans, because of the high levels of cytochrome c oxidase activity that are present in P. denitrificans membranes. E. coli, however, contains only quinol oxidases. Low levels of cytochrome c oxidase activity were detected in JM109(pNOREX, pEC86) (Table 3). There was no activity in cells that did not harbor pNOREX, confirming that the activities detected were due to NOR. Significantly, no cytochrome oxidase activity could be detected in NORs with the E125A or E198A substitution.

UV-Vis and EPR characterization of purified preparations of NORREC, NORE125A, and NORE198A.

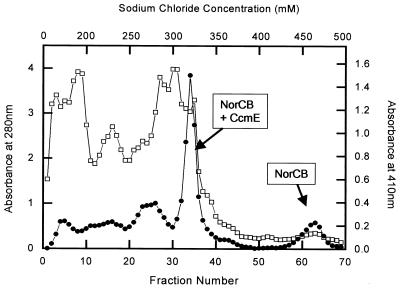

Recombinant NOR (NORREC), NORE125A, and NORE198A were purified from 15-liter L broth cultures of E. coli JM109 carrying the appropriate plasmid. The key step in the purification (described in Materials and Methods) involved the Q-Sepharose column from which NorCB eluted in two cytochrome-containing peaks at around 320 and 450 mM NaCl (Fig. 4). The first of these also contained large amounts of CcmE. In the second peak, NorCB was separated from other contaminating cytochromes and proteins. The NOR from this second peak was collected and separated on the IMAC column prior to characterization. The ratio of the two elution peaks from the Q-Sepharose column varied from preparation to preparation and influenced the final yield of purified protein, which was 5 to 10 mg per 15 liters of culture.

FIG. 4.

The elution profile of NorCB from a Q-Sepharose column. Fraction volumes were 12 ml. A 0 to 200 mM salt gradient was run for the first 120 ml. This was then switched to a 200 to 500 mM gradient for the following 720 ml. ●, cytochrome absorbance at 410 nm; □, protein absorbance at 280 nm.

The patterns of NOR and oxidase activities in purified NORREC and NORE125A and NORE198A reflected those observed in membrane fractions. The turnover number for NORREC was comparable to that of native NOR (purified from P. denitrificans; NORNAT) determined in side-by-side experiments and was in the range of 40 to 70 electrons s−1 for NO reduction and 2 to 5 electrons s−1 for oxygen reduction. NORE198A had no detectable activity, and NORE125A had a low turnover number in the range of 3 to 5 electrons s−1 for NO reduction and around 1 electron s−1 for oxygen reduction. Comparison of the UV-Vis spectra of the oxidized forms of NORNAT, NORREC, NORE125A, and NORE198A revealed absorption features typical of the Soret band (411 nm) and αβ absorption bands (520 to 570 nm) of low-spin ferric hemes. On reduction with dithionite, the Soret band shifted to 420 nm and an increase in absorption at 550 and 560 nm characteristic of the α bands of low-spin ferrous c and b hemes, respectively, was observed. These features were essentially identical for all four enzymes, and representative spectra for NORREC are shown in Fig. 5A.

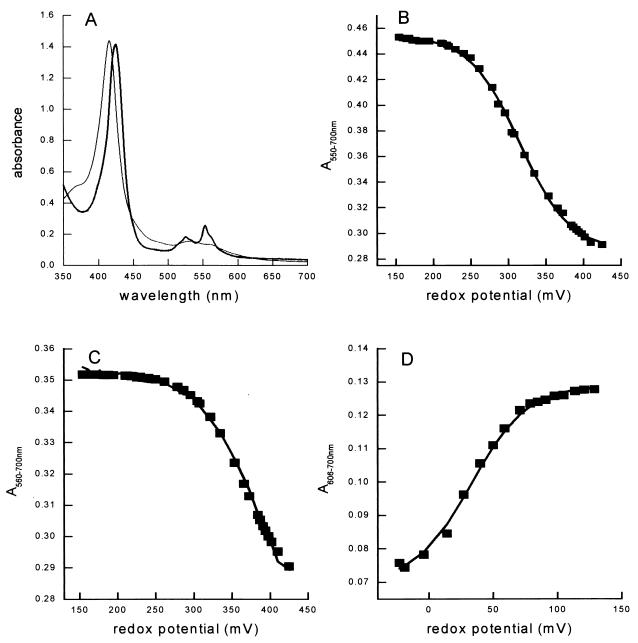

FIG. 5.

Visible absorption spectra and redox potentiometry of NORE198. (A) “Air-oxidized” (thin line) and “dithionite-reduced” (thick line) absorption spectra. (B) Redox titration of NORREC monitored at 550 to 700 nm. (C) Redox titration of NORREC monitored at 560 to 700 nm. (D) Redox titration of NORREC monitored at 606 to 700 nm. The solid curves (B to D) show fits with n = 1 Nernstian curves using midpoint potentials of +316, +366, and +32 mV, respectively. All spectra and titrations were performed on samples incubated at 20°C in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)–0.02% dodecyl maltoside–340 mM NaCl–0.5 mM EDTA.

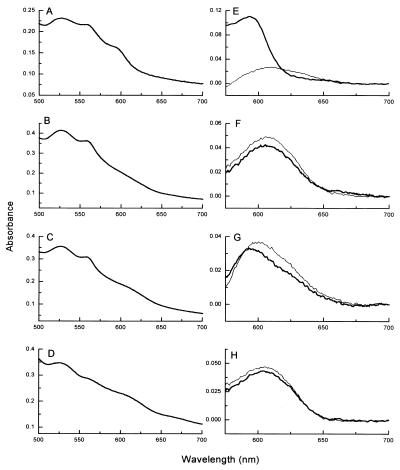

A major difference in the spectra of the four enzymes was observed in a charge transfer (CT) band at around 600 nm, which arises from the high-spin heme b3 of the dinuclear center (11, 13). This CT band disappears on reduction of the enzyme, enabling it to be resolved most clearly in “oxidized minus reduced” spectra (Fig. 6). In NORNAT the wavelength for maximum absorbance (λmax) is 595 nm (Fig. 6A and E), in NORREC (Fig. 6B and F) and NORE125A (Fig. 6D and H) it is red shifted to 606 nm, and in NORE198A (Fig. 6C and G) it is a mixture of the 595- and 606-nm forms. This CT band has been seen in the visible absorption spectrum of NOR in a number of published preparations, but variations in its position and intensity have been noted (8, 10, 11, 13, 15), and it is barely visible at all in enzymes from Pseudomonas stutzeri (12, 15). The position of this CT band cannot be correlated with differences in enzyme activity, and its variable λmax probably arises from differences in the coordination environment of the high-spin heme b of the resting enzymes. The precise nature of these differences cannot be resolved at present, but is likely to involve the sixth coordination position of the ferric heme iron in the resting-state enzymes. Significantly, this difference in the resting state of the enzymes cannot account for the low activity of NORE125A and NORE198A, since NORNAT (“595” species) and NORREC (“606” species) both exhibit high enzymatic activity. The differences in resting states of the NOR enzymes are reminiscent of those of the E. coli cytochrome bo quinol oxidase, in which the active-site dinuclear center can exhibit considerable heterogeneity (30, 31).

FIG. 6.

Absorption spectra of NORNAT, NORREC, NORE198A, and NORE125A showing the CT band arising from high-spin heme b3. (A to D) Air oxidized spectra of NORNAT (A), NORREC (B), NORE198A (C), and NORE125A (D). (E to H) Oxidized-minus-reduced difference spectra (thick lines) of NORNAT (E), NORREC (F), NORE198A (G), and NORE125A (H) and three-electron-reduced minus four-electron-reduced difference spectra (thin lines) of NORNAT (E), NORREC (F), NORE198A (G), and NORE125A (H). These were obtained by subtracting spectra collected at around −50 mV from spectra collected at around +140 mV.

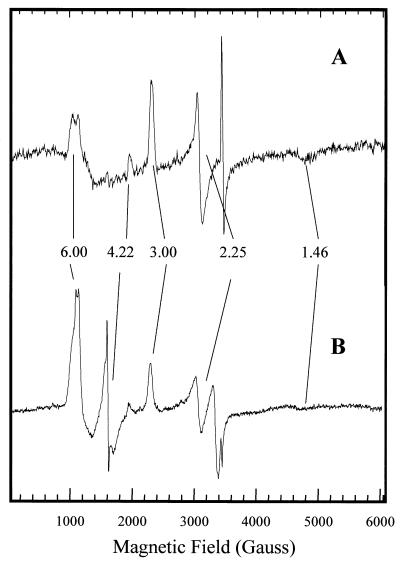

NORNAT, NORREC, NORE125A, and NORE198A were also examined by EPR spectroscopy. The EPR spectrum of NORNAT shows the presence of two low-spin (s = ½) ferric hemes (Fig. 7A), one with a typical rhombic spectrum (gz = 3.00, gy = 2.25, gx = 1.46) and the other with a high gmax signal (gz = 3.55). These signals have previously been ascribed to the low-spin bis-His-coordinated heme b and the low-spin His-Met-coordinated heme c of NOR and yield spin quantitations of 1:1 (5). Both signals could also be resolved in NORREC and were present at relative intensities similar to those of NORNAT (Fig. 7B). The major difference between NORNAT and NORREC was in the signals at g ≈ 6 and g ≈ 4.2. The signal at g ≈ 6 arises from s =  high-spin ferric heme, most likely a small proportion of the heme b from the dinuclear center that is not magnetically coupled to the nonheme iron. The small increase of this uncoupled population of the dinuclear center in NORREC is also reflected by an increase in the structured g ≈ 4.2 resonance that arises from the uncoupled FeB nonheme iron. The EPR spectra of NORE125A and NORE198A were essentially identical to that of the NORREC enzyme (not shown). Given that NORREC is fully active, the increased population of the non-magnetically coupled dinuclear center compared to that for NORNAT cannot account for the low activity of the NORE125A and NORE198A enzymes.

high-spin ferric heme, most likely a small proportion of the heme b from the dinuclear center that is not magnetically coupled to the nonheme iron. The small increase of this uncoupled population of the dinuclear center in NORREC is also reflected by an increase in the structured g ≈ 4.2 resonance that arises from the uncoupled FeB nonheme iron. The EPR spectra of NORE125A and NORE198A were essentially identical to that of the NORREC enzyme (not shown). Given that NORREC is fully active, the increased population of the non-magnetically coupled dinuclear center compared to that for NORNAT cannot account for the low activity of the NORE125A and NORE198A enzymes.

FIG. 7.

X-band EPR spectra of air-oxidized native (A) and recombinant wild-type (B) NOR. The spectra were recorded at 10 K, 9.44 GHz, and 2 mW microwave power. The feature at ca. 2.01 in spectrum A may arise from a small (<1%) contaminant of a [3Fe4S]1+ center from the P. denitrificans membrane-bound nitrate reductase.

Spectropotentiometric characterization of NORREC, NORE125A, and NORE198A.

Visible absorption spectra of NORNAT, NORREC, NORE125A, and NORE198A were collected at a number of defined redox potentials. In all cases, increases in the intensities of the α bands of the low-spin c heme (550 nm) and low-spin b heme (560 nm) were observed between ca. +400 and +200 mV. The absorption differences at 550 to 700 nm and 560 to 700 nm over this potential range were plotted as a function of redox potential and the midpoint potentials were derived by fitting single component n = 1 Nernstian curves to the data (a representative data set for NORREC is shown in Fig. 5B and C). For all four enzymes, the midpoint potentials of the low-spin c heme lay in the range of +310 to +322 mV (Table 4). Those of the low-spin b heme were slightly higher, in the range +345 to +401 mV (Table 4). These values are all consistent with these low-spin heme centers mediating electron transfer from the physiological electron donors, periplasmic cytochrome c550 (Em = +265 mV) and pseudoazurin (Em = +230 mV), to the dinuclear center.

TABLE 4.

Midpoint redox potentials of the NOR heme centers

| Enzyme | Em (mV) of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| c heme | Low-spin b heme | High-spin b heme | |

| NORNAT | 310 | 345 | 40 |

| NORREC | 316 | 366 | 32 |

| NORE125A | 320 | 380 | 20 |

| NORE198A | 322 | 401 | 2 |

Analysis of the 595/606-nm CT band arising from high-spin heme b is more complex. We have previously reported that the λmax of this CT band in NORNAT is shifted from 595 to 606 nm following reduction of the low-spin c and b hemes and FeB to yield the “three-electron-reduced” enzyme (11). We have argued that this shift in λmax reflects a change in the coordination environment of high-spin heme b that accompanies the reduction of the spectroscopically silent FeB (Em = +320 mV) (11). This idea is supported by the present study, and an illustrative absorption spectrum of the three-electron-reduced form collected at +140 mV is presented in Fig. 6E. This reveals that the extinction coefficient of the 595-nm CT band is around fivefold greater (approximately 6 mM−1 cm−1) than that of the 606-nm CT band (approximately 1.2 mM−1 cm−1).

In the light of these data, consideration of the oxidized spectrum of NORE198A (Fig. 6G) suggests that around 20% of the enzyme is in the 595-nm form and around 80% is in the 606-nm form. The spectrum is largely unchanged when the Eh is lowered to +250 mV (not shown). However, lowering the Eh from +250 to +140 mV results in the loss of the 595-nm feature of the NORE198A spectrum and a 20% increase in the intensity of the 605-nm band (Fig. 6G). This increase can be ascribed to the reduction of FeB in the 20% of the enzyme population that is in the 595-nm form. The absorption changes are too small to allow the plotting of a Nernstian curve, but the data place the Em of NORE198A FeB at around +200 mV, considerably lower than that of the FeB in NORNAT (+320 mV) (11). Both NORREC and NORE125A are in an almost homogenous 606-nm form in the fully oxidized enzyme, and reduction to +140 mV does not significantly change the form of this CT band (Fig. 6F and H). Thus, consideration of NORNAT, NORREC, NORE125A, and NORE198A, poised at around +140 mV, reveals that all four enzymes are in a similar spectroscopic state in which it is likely that low-spin hemes c and b and FeB are reduced and high-spin heme b remains oxidized in a 606-nm state. The 606-nm bands of NORNAT, NORREC, NORE125A, and NORE198A all disappear as the Eh is lowered from +140 mV to −80 mV. This reflects the reduction of high-spin heme b3 to yield the fully (four-electron-reduced) enzyme. The reduction of this center can be fitted to single n = 1 Nernstian curves (Fig. 5D; shown for NORREC only) which yield midpoint redox potentials that lie in the range of +2 to +40 mV for all four forms of NOR studied (Table 4). We have previously argued that the low potential of high-spin heme b3 provides a thermodynamic barrier that prevents reduction of this site during the catalytic cycle (11). If heme b3 becomes reduced, then, potentially, a dead-end ferrous nitrosyl complex could form. This thermodynamic barrier would exist in each of the four enzyme types discussed in this paper, since in each case the difference in reduction potential between low-spin heme b and the active-site heme is at least 300 mV.

In conclusion, the accumulated spectroscopic data for purified NORNAT, NORREC, NORE125A, and NORE198A demonstrate that the inactivity of NORE125A and NORE198A is unlikely to be accounted for by either enzyme instability, failure to insert cofactors, or perturbation of the redox potentials of the heme cofactors. The location of E198 one helical turn below a likely FeB ligand (H194) in helix VI strongly implicates it as contributing to the immediate environment of FeB, which is also consistent with the preliminary suggestion that the Em of the FeB is perturbed in NORE198A. Certainly FeB, which unlike CuB prefers an octahedral coordination environment, is likely to have at least one extra protein-derived ligand. However, E198 is also well placed to serve as a base for NO radical chemistry or for delivery of catalytic protons. More-detailed spectroscopic and electrochemical studies on NORE198A will now be undertaken to explore these possibilities. The importance of E125 is perhaps most surprising given that it is located towards the periplasmic face of helix IV and is not predicted to be close to the FeB. Previous studies have indicated that NOR is not proton translocating (2, 3, 23) and that the two chemical protons required for NO reduction are taken up from the periplasm. Given the conservation of E125, a role in proton uptake should be considered.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to James Moir for valuable ideas at the outset of this work; Lola Roldán, Andrew Thomson, and Myles Cheeseman for discussion and help in strategy development; Karen Grönberg and Jeremy Thornton for provision of native NOR; Matti Saraste for provision of antibody to NorB; Werner Klipp, Rob van Spanning, and Lynda Thöney-Meyer for provision of strains and plasmids; and Adam Baker and Louise Prior for collecting the EPR spectra.

The work was funded by BBSRC grant 83/C10160, the award of a BBSRC/EPSRC special studentship to G.B., the UEA innovation fund, and CEC grant EC BIO-CT98-0507. N.J.W. is a Wellcome Trust University Award Lecturer (054798/Z/98Z).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adelroth P, Gennis R B, Brzezinski P. Role of the pathway through K(I-362) in proton transfer in cytochrome c oxidase from R. sphaeroides. Biochemistry. 1998;37:2470–2476. doi: 10.1021/bi971813b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell L C, Richardson D J, Ferguson S J. Identification of nitric oxide reductase activity in Rhodobacter capsulatus: the electron transport pathway can either use or bypass both cytochrome c2 and the cytochrome bc1 complex. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:437–443. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-3-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carr G J, Page M D, Ferguson S J. The energy-conserving nitric-oxide-reductase system in Paracoccus denitrificans. Distinction from the nitrite reductase that catalyses synthesis of nitric oxide and evidence from trapping experiments for nitric oxide as a free intermediate during denitrification. Eur J Biochem. 1989;179:683–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb14601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castresana J, Saraste M. Evolution of energetic metabolism: the respiration-early hypothesis. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:443–448. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheesman M R, Zumft W G, Thomson A J. The MCD and EPR of the heme centers of nitric oxide reductase from Pseudomonas stutzeri: evidence that the enzyme is structurally related to the heme-copper oxidases. Biochemistry. 1998;37:3994–4000. doi: 10.1021/bi972437y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Vries G E, Harms N, Hoogendijk J, Stouthamer A H. Isolation and characterisation of Paracoccus denitrificans mutants with increased conjugation frequencies and pleiotropic loss of a (nGATCn) DNA modifying property. Arch Microbiol. 1989;152:52–57. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fellay R, Frey J, Krisch H. Interposon mutagenesis of soil and water bacteria: a family of DNA fragments designed for in vitro insertional mutagenesis of gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1987;52:147–154. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujiwara T, Fukumori Y. Cytochrome cb-type nitric oxide reductase with cytochrome c oxidase activity from Paracoccus denitrificans ATCC 35512. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1866–1871. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.1866-1871.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerhus E, Steinrucke P, Ludwig B. Paracoccus denitrificans cytochrome c1 gene replacement mutants. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2392–2400. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.5.2392-2400.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Girsch P, de Vries S. Purification and initial kinetic and spectroscopic characterization of NO reductase from Paracoccus denitrificans. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1318:202–216. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(96)00138-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grönberg K L, Roldán M D, Prior L, Butland G, Cheesman M R, Richardson D J, Spiro S, Thomson A J, Watmough N J. A low-redox potential heme in the dinuclear center of bacterial nitric oxide reductase: implications for the evolution of energy-conserving heme-copper oxidases. Biochemistry. 1999;38:13780–13786. doi: 10.1021/bi9916426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heiss B, Frunzke K, Zumft W G. Formation of the N-N bond from nitric oxide by a membrane-bound cytochrome bc complex of nitrate-respiring (denitrifying) Pseudomonas stutzeri. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3288–3297. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.6.3288-3297.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hendriks J, Warne A, Gohlke U, Haltia T, Ludovici C, Lubben M, Saraste M. The active site of the bacterial nitric oxide reductase is a dinuclear iron center. Biochemistry. 1998;37:13102–13109. doi: 10.1021/bi980943x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hutchings M I, Spiro S. The nitric oxide regulated nor promoter of Paracoccus denitrificans. Microbiology. 2000;146:2635–2641. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-10-2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kastrau D H, Heiss B, Kroneck P M, Zumft W G. Nitric oxide reductase from Pseudomonas stutzeri, a novel cytochrome bc complex. Phospholipid requirement, electron paramagnetic resonance and redox properties. Eur J Biochem. 1994;222:293–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Konstantinov A A, Siletsky S, Mitchell D, Kaulen A, Gennis R B. The roles of the two proton input channels in cytochrome c oxidase from Rhodobacter sphaeroides probed by the effects of site-directed mutations on time-resolved electrogenic intraprotein proton transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9085–9090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwiatkowski A V, Laratta W P, Toffanin A, Shapleigh J P. Analysis of the role of the nnrR gene product in the response of Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1 to exogenous nitric oxide. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5618–5620. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5618-5620.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moenne Loccoz P, deVries S. Structural characterisation of the catalytic high spin heme b of nitric oxide reductase. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:5147–5152. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reincke B, Thony-Meyer L, Dannehl C, Odenwald A, Aidim M, Witt H, Ruterjans H, Ludwig B. Heterologous expression of soluble fragments of cytochrome c552 acting as electron donor to the Paracoccus denitrificans cytochrome c oxidase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1411:114–120. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(99)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roldan M D, Sears H J, Cheesman M R, Ferguson S J, Thomson A J, Berks B C, Richardson D J. Spectroscopic characterization of a novel multiheme c-type cytochrome widely implicated in bacterial electron transport. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28785–28790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.44.28785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saraste M, Castresana J. Cytochrome oxidase evolved by tinkering with denitrification enzymes. FEBS Lett. 1994;341:1–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80228-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schulz H, Fabianek R A, Pellicioli E C, Hennecke H, Thöny-Meyer L. Heme transfer to the heme chaperone CcmE during cytochrome c maturation requires the CcmC protein, which may function independently of the ABC-transporter CcmAB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6462–6467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shapleigh J P, Payne W J. Nitric oxide-dependent proton translocation in various denitrifiers. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:837–840. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.3.837-840.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simon R, Priefer V, Pühler A. Vector plasmids for in vivo and in vitro manipulations of gram-negative bacteria. In: Pühler A, editor. Molecular biology of bacteria and plant interaction. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag KG; 1983. pp. 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stoll R, Page M D, Sambongi Y, Ferguson S J. Cytochrome c550 expression in Paracoccus denitrificans strongly depends on growth condition: identification of promoter region for cycA by transcription start analysis. Microbiology. 1996;142:2577–2585. doi: 10.1099/00221287-142-9-2577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Oost J, de Boer A P, de Gier J W, Zumft W G, Stouthamer A H, van Spanning R J. The heme-copper oxidase family consists of three distinct types of terminal oxidases and is related to nitric oxide reductase. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;121:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Spanning R J, Houben E, Reijnders W N, Spiro S, Westerhoff H V, Saunders N. Nitric oxide is a signal for NNR-mediated transcription activation in Paracoccus denitrificans. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4129–4132. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.13.4129-4132.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Spanning R J, Wansell C W, Reijnders W N, Harms N, Ras J, Oltmann L F, Stouthamer A H. A method for introduction of unmarked mutations in the genome of Paracoccus denitrificans: construction of strains with multiple mutations in the genes encoding periplasmic cytochromes c550, c551i, and c553i. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6962–6970. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.21.6962-6970.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watmough N J, Butland G, Cheesman M R, Moir J W, Richardson D J, Spiro S. Nitric oxide in bacteria: synthesis and consumption. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1411:456–474. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(99)00032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watmough N J, Cheesman M R, Butler C S, Little R H, Greenwood C, Thomson A J. The dinuclear center of cytochrome bo3 from Escherichia coli. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1998;30:55–62. doi: 10.1023/a:1020507511285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watmough N J, Cheesman M R, Gennis R B, Greenwood C, Thomson A J. Distinct forms of the haem o-Cu binuclear site of oxidised cytochrome bo from Escherichia coli. Evidence from optical and EPR spectroscopy. FEBS Lett. 1993;319:151–154. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80056-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zaslavsky D, Gennis R B. Substitution of lysine-362 in a putative proton-conducting channel in the cytochrome c oxidase from Rhodobacter sphaeroides blocks turnover with O2 but not with H2O2. Biochemistry. 1998;37:3062–3067. doi: 10.1021/bi971877m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]