Abstract

Penicillin-binding protein 1b (PBP1b) is the major high-molecular-weight PBP in Escherichia coli. Although it is coded by a single gene, it is usually found as a mixture of three isoforms which vary with regard to the length of their N-terminal cytoplasmic tail. We show here that although the cytoplasmic tail seems to play no role in the dimerization of PBP1b, as was originally suspected, only the full-length protein is able to protect the cells against lysis when both PBP1a and PBP3 are inhibited by antibiotics. This suggests a specific role for the full-length PBP1b in the multienzyme peptidoglycan-synthesizing complex that cannot be fulfilled by either PBP1a or the shorter PBP1b proteins. Moreover, we have shown by alanine-stretch-scanning mutagenesis that (i) residues R11 to G13 are major determinants for correct translocation and folding of PBP1b and that (ii) the specific interactions involving the full-length PBP1b can be ascribed to the first six residues at the N-terminal end of the cytoplasmic domain. These results are discussed in terms of the interactions with other components of the murein-synthesizing complex.

Penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) are a set of cytoplasmic membrane enzymes involved in the last steps of peptidoglycan biosynthesis (17, 26). These proteins are inactivated by β-lactam antibiotics which irreversibly bind the transpeptidase domain. In Escherichia coli nine PBPs have been identified which can be divided into two groups depending on their molecular weight (13, 25). The low-molecular-weight PBPs (PBP4, -5, -6, -6b, and -7) are involved in regulating the number of peptide cross-links and are probably not essential for bacterial growth (7), whereas the high-molecular-weight PBPs are bimodular enzymes and possess either transpeptidase activity (PBP2 and -3) or both transglycosylase and transpeptidases activities (PBP1a and -1b) (17, 18, 26, 29). PBP2 and PBP3 (also known as FtsI) are involved in maintaining the rod shape and in cell division, respectively (1, 2). Indeed, specific inhibition of PBP2 results in the formation of spherical cells and impairment of PBP3 by using specific antibiotics or by growing temperature-sensitive mutants at a nonpermissive temperature causes cells to grow as elongated filaments. Two recent studies have confirmed by immunofluorescence microscopy that PBP3 is recruited to the divisome site during the later stages of cell growth and throughout septation (34, 36).

PBP1a and PBP1b represent the major murein polymerizing enzymes. At least one of either PBP1a or PBP1b is essential for growth, since a deletion of both genes is lethal (20, 28, 31, 39). PBP1b is usually present in the cell membrane in three molecular forms termed α, β, and γ which differ in size but are all encoded by a single gene, ponB. PBP1bα consists of 844 amino acids and is anchored to the inner membrane, the first 64 residues being cytoplasmic. The β form lacks the first 24 N-terminal residues and was shown to be a degradation product of the α component (14, 30). PBP1bγ arises from the use of an alternative translation start site at codon corresponding to residue M46 of the PBP1bα sequence (4, 19). Each form has been shown to catalyze both transglycosylation and transpeptidation, and production of a single component corresponding to γ was sufficient to correct the defects caused by the mutational loss of PBP1b (19).

PBPs work in close association with other enzymes, including hydrolases and synthetases, in the control of bacterial morphology, elongation, and cell division. It has therefore been proposed that some of these proteins may interact as members of multienzyme complexes, allowing a better coordination of their enzymatic activities (15, 16). The existence of these complexes is supported by numerous studies, including protein-protein interaction studies based on affinity chromatography, studies based on the use of specific inhibitors of high-molecular-weight PBPs, and genetic studies (17, 33). In particular, several lines of evidence indicate that PBP1b belongs to the divisome, a multimeric structure implicated in cell division, and takes part in the septum formation in conjunction with PBP3 in E. coli (3, 17). This idea is supported by analysis of the behavior of strains deficient either in PBP1a or in PBP1b grown in the presence of β-lactams which specifically inhibit PBP1 or PBP3 (10, 11, 12, 37).

Earlier studies have shown that PBP1b is able to form dimers (6, 33, 40, 41) and that only homodimers, α-α, β-β, or γ-γ, occur (40; X. Charpentier, unpublished data), suggesting an involvement of the cytoplasmic tail of PBP1b in the dimerization process. We thus expressed the different forms of PBP1b in an E. coli strain deleted for the ponB gene. When bacteria expressing the PBP1b of different lengths were assayed for growth in the presence of various β-lactams, we observed different antibiotic susceptibilities, suggesting that these forms might differ in their functionality. Further experiments performed with mutants of PBP1bα harboring sequential amino acid substitutions showed that some residues within the N-terminal region play specific roles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and growth conditions.

Cultures were routinely grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (1% tryptone [Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.], 0.5% yeast extract [Difco], 1% NaCl) at 37°C under vigorous agitation. Strains harboring resistance determinants were grown in the presence of tetracycline (12.5 μg/ml; Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) or spectinomycin (100 μg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.).

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

E. coli K-12 strains used were MC6-RP1 (F− thrA leuA proA lysA dra drm) and QCB1 (F− thrA leuA proA lysA dra drm ΔponB::Spcr). Cloning steps were performed with MC1061 [F− araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7636 galE15 galK16 Δ(lac)X74 rpsL mcrA mcrB1 hsdR2(rK− mK+)]. pPONB is a low-copy-number Tetr plasmid that expresses PBP1b fused to a tag peptide (YPYDVPDYA) from the hemagglutinin HA1 epitope of influenza virus (38) at its C-terminal end (24).

Construction of the pPONB derivative plasmids.

Plasmids used in this study were constructed by double-strand site-directed mutagenesis with the inverse-PCR technique (35) and checked by DNA sequencing at Genome Express (Grenoble, France). Oligonucleotides were synthetized by Isoprim (Toulouse, France). The resulting constructs and the corresponding PBP1b mutants are listed in Fig. 1.

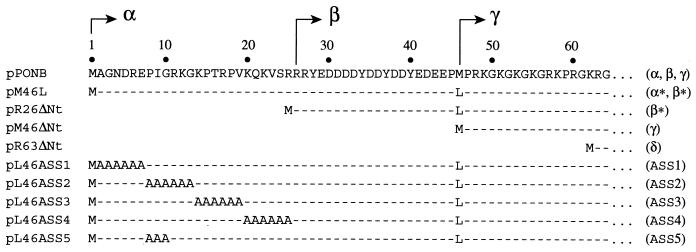

FIG. 1.

Amino-terminal sequences of the PBP1b mutants. Amino acid sequence of the cytoplasmic domain of PBP1bα coded by plasmid pPONB is shown (residues 1 to 64). The beginning of the sequences of the β and γ components are indicated by arrows. Amino acid sequences corresponding to the cytoplasmic domains of the PBP1b mutants (indicated on the right in parentheses) expressed by plasmids used in this study are aligned with the amino-terminal sequence of PBP1bα. Except for methionine, identical amino acids are shown by dashed lines and changed residues are indicated by their corresponding letters.

Plasmids pM46L, pR26ΔNt, pM46ΔNt, and pR63ΔNt are derivatives of pPONB. pM46L was made by replacement of the M46 codon by a leucine codon in the ponB gene. pR26ΔNt, pM46ΔNt, and pR63ΔNt carry deletions of the ponB sequence corresponding to the cytoplasmic region of PBP1b. They were made by fusing the ATG start (M1) codon to the R26 codon for pR26ΔNt, to the P47 codon for pM46ΔNt, and to the R63 codon for pR63ΔNt.

pL46ASS1, pL46ASS2, pL46ASS3, and pL46ASS4 originate from pM46L. They produce PBP1bα* mutants in which residues A2 to E7 for pL46ASS1, P8 to G13 for pL46ASS2, K14 to V19 for pL46ASS3, and K20 to R25 for pL46ASS4 have been substituted by a six-alanine stretch. To construct pL46ASS5, the PstI-MluI fragment of pL46ASS2, which encodes amino acids A11 to T16, was removed by cutting pL46ASS2 with PstI and MluI. A 19-bp PstI-MluI oligonucleotides linker was then cloned into the digested plasmid. The resulting construct produces a PBP1bα* mutant protein where residues P8 to G10 have been substituted by three alanines (Fig. 1).

Preparation of membrane fractions and labeling of the PBPs with fluorescent penicillin.

Membrane fractions from E. coli strain QCB1 expressing wild-type PBP1b or any of its variants were prepared as described by Lefèvre et al. (24). Fluorescent 6-amino-penicilloic acid (6-APA-FLU) was synthesized as described by Galleni et al. (9) and Lakaye et al. (22). For the penicillin-binding assay, 2 μl of 6-APA-FLU at 147 μg/ml was mixed with membrane fractions in a final volume of 20 μl. Incubation was at 30°C for 30 min. The membrane proteins were then subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and PBPs were detected by immunoblotting assay with an antifluorescein isothiocyanate-horseradish peroxidase conjugate antibody (Amersham) as described below.

SDS-PAGE and immunodetection.

Membrane proteins prepared from strain QCB1 carrying pPONB or any of its derivatives were incubated with sample buffer at 95°C for 10 min and subjected to SDS-PAGE on a 7% polyacrylamide gel according to the method of Laemmli et al. (21). After SDS-PAGE, proteins were electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose sheets (Gelman) and analyzed by Western blotting performed with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham). Membranes were either incubated with an antifluorescein isothiocyanate-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (1/1,000) when PBPs had previously been labeled with 6-APA-FLU or with antibody 12CA5 (1/50,000) raised against the HA1 peptide tag from the hemagglutinin of influenza virus (a generous gift from J. Grassi, Commissariat à l'Énergie Atomique, Saclay, France) and with an anti-mouse peroxidase conjugate (1/10,000; Sigma) and exposed to Fuji X-ray films.

Treatment of exponentially growing cells with aztreonam and cephaloridine.

One bacterial colony of QCB1 freshly transformed with pPONB or any of its derivatives was inoculated in 2 ml of LB medium with tetracycline (12.5 μg/ml) and incubated overnight at 37°C. A portion (200 μl) of the preculture was then diluted into 100 ml of LB medium with tetracycline (12.5 μg/ml). For strain QCB1 harboring no plasmid and strain MC6-RP1, experiments were carried out without tetracycline in the medium.

When the optical density at 550 nm (OD550) reached 0.1, the culture was divided into four portions of 25 ml each. No additional antibiotic was added in the first portion, whereas the second, third, and fourth portions were treated with aztreonam (0.5 μg/ml; a generous gift from Bristol Mayer Squibb), cephaloridine (0.3 μg/ml; Glaxo Laboratories), and aztreonam plus cephaloridine, respectively. Growth was monitored by measuring the OD550 of the cultures at different times (0, 30, 60, 90, 120, and 180 min).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Expression and activities of the α, β, and γ forms of PBP1b.

In previous studies, PBP1b was produced in strain QCB1, which was transformed with vector pPONB (6, 24). QCB1 is an E. coli strain with a deletion in ponB, which codes for PBP1b (11). The three molecular forms of PBP1b (PBP1bα, -β, and -γ) can be visualized by Western blotting, performed on E. coli membrane preparations, with monoclonal antibody 12CA5 raised against the tag peptide.

In order to produce each form of PBP1b separately, we constructed plasmids pM46L, pR26ΔNt, and pM46ΔNt. QCB1 harboring pM46L produces PBP1bα*, in which residue M46 was substituted by a leucine (Fig. 1). This mutation should abolish the production of the γ component of PBP1b. Western blot analysis with 12CA5 revealed two bands corresponding to PBP1bα* and its degradation product PBP1bβ* and confirmed that the γ form of PBP1b was absent (Fig. 2A, lane 3). Moreover, it showed that PBP1bα* was produced at the same level as wild-type PBP1bα expressed from pPONB in QCB1 (Fig. 2A, lane 2). The PBP1bα* mutant bound fluorescent penicillin as efficiently as the wild type, indicating a proper folding and a functional transpeptidase activity (Fig. 2B, lane 3).

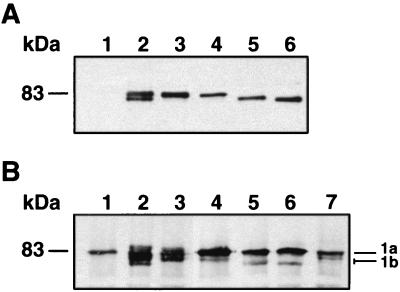

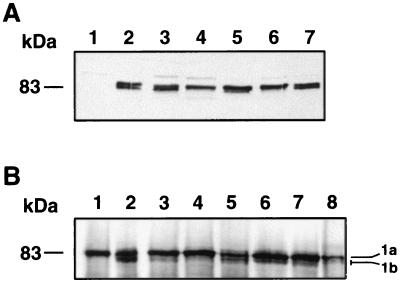

FIG. 2.

α*, β*, γ, and δ forms of PBP1b. (A) Production of the α*, β*, γ, and δ forms of PBP1b. Membrane fractions from QCB1 (15 μg, lane 1) or QCB1 transformed with pPONB (10 μg, lane 2), pM46L (10 μg, lane 3), pR26ΔNt (15 μg, lane 4), pM46ΔNt (15 μg, lane 5), or pR63ΔNt (15 μg, lane 6) were analyzed by Western blotting using the antitag 12CA5 antibody. (B) Binding of 6-APA-FLU by the α*, β*, γ, and δ forms of PBP1b. Membrane fractions (100 μg) from QCB1 (lane 1) or QCB1 transformed with pPONB (lane 2), pM46L (lane 3), pR26ΔNt (lane 4), pM46ΔNt (lane 5), or pR63ΔNt (lane 6) and from MC6-RP1 (lane 7) were incubated with 6-APA-FLU and analyzed by Western blotting with an antifluorescein antibody. 1a, PBP1a mutant; 1b, PBP1b mutant.

In plasmid pR26ΔNt, deletion of the ponB sequence corresponding to residues A2 to R25 was made in addition to the M46L mutation. This plasmid avoids expression of PBP1bγ and allows expression of a mutated β component of PBP1b, namely, PBP1bβ* (Fig. 1). pM46ΔNt, which carries a deletion of the ponB sequence corresponding to the first 45 residues, was expected to yield solely PBP1bγ (Fig. 1). Western blot analysis indicated that both mutant proteins were produced at a level corresponding to one-third of that obtained with mutant PBP1bα* (Fig. 2A, lanes 4 and 5) but were able to bind efficiently fluorescent penicillin (Fig. 2B, lanes 4 and 5).

An additional mutant lacking the entire cytoplasmic domain, PBP1bδ, was produced by plasmid pR63ΔNt (Fig. 1). This mutant was produced at the same level as PBP1bβ* and PBP1bγ in strain QCB1 and was still able to bind fluorescent penicillin (Fig. 2A and B, lanes 6), indicating that it is translocated across the membrane and correctly folded.

The cytoplasmic domain is not required for the dimerization of PBP1b.

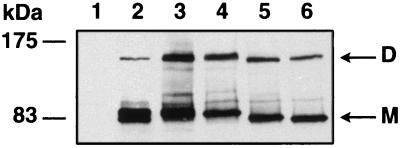

It has been shown that PBP1b is able to form fairly stable dimers which can be detected by SDS-PAGE at a position corresponding to a molecular mass ranging from 140 to 150 kDa. To detect whether the cytoplasmic region is necessary for the formation of the dimer, the α*, β*, and γ forms, as well as PBP1bδ, were tested for their ability to dimerize.

The membrane fraction from strain QCB1 harboring pM46L, pR26ΔNt, pM46ΔNt, or pR63ΔNt was incubated in sample buffer containing 5% β-mercaptoethanol at room temperature for 10 min and subjected to SDS-PAGE for Western blot analysis as previously described (6). Under these conditions, major bands were detected at positions corresponding to the different molecular forms of PBP1b (PBP1bα*, -β*, -γ, and -δ), and additional bands reacted with the antitag antibody at positions corresponding to the dimeric form of each component (Fig. 3). These dimers remained stable after incubation for 10 min at 60°C with sample buffer but were almost totally dissociated at 80°C (data not shown), indicating strong interactions between the monomers. This finding clearly demonstrates that the cytoplasmic domain is not required for the dimerization of PBP1b thus suggesting another role, if any, for this domain.

FIG. 3.

Stability of PBP1b dimers. Membrane fractions prepared from strain QCB1 (50 μg, lane 1) or QCB1 transformed with pPONB (25 μg, lane 2), pM46L (25 μg, lane 3), pR26ΔNt (50 μg, lane 4), pM46ΔNt (50 μg, lane 5), or pR63ΔNt (50 μg, lane 6) were incubated for 10 min in sample buffer with 5% β-mercaptoethanol at room temperature. Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with the anti-tag 12CA5 antibody. M, monomeric forms of PBP1b mutants; D, dimeric forms of PBP1b mutants.

Effects of antibiotics on the growth of strains producing the α*, β*, or γ form of PBP1b.

García del Portillo et al. (11, 12) have shown that blocking PBP3 with a specific antibiotic was lytic for an E. coli mutant defective in PBP1b, suggesting an involvement of PBP1b in peptidoglycan synthesis at the level of septation probably in conjunction with PBP3. Since expression of the β* or the γ mutant in QCB1 results in a moderate increase in antibiotic susceptibility compared to cells expressing PBP1bα* (not shown), this led us to investigate whether the increased antibiotic susceptibility of the mutants could reflect differential interactions between each of the PBP1b forms and PBP3 or any protein involved in septation. We thus studied the effects of aztreonam, alone or in combination with cephaloridine, on the growth of QCB1 expressing the different forms of PBP1b (Fig. 4). At concentrations used throughout this study, cephaloridine (0.3 μg/ml) and aztreonam (0.5 μg/ml) have been shown by competition to specifically inhibit PBP1a and PBP3, respectively (5, 39).

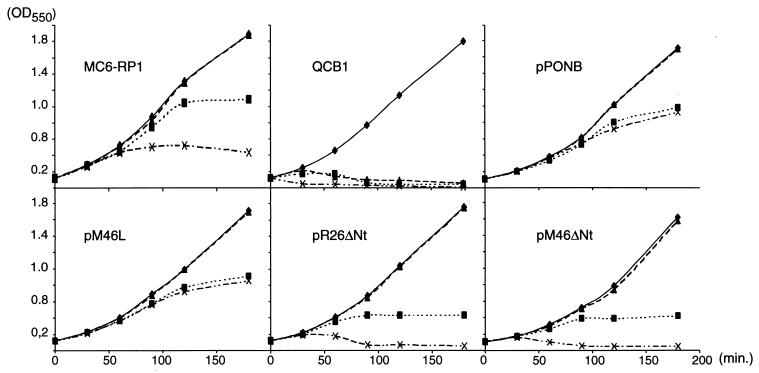

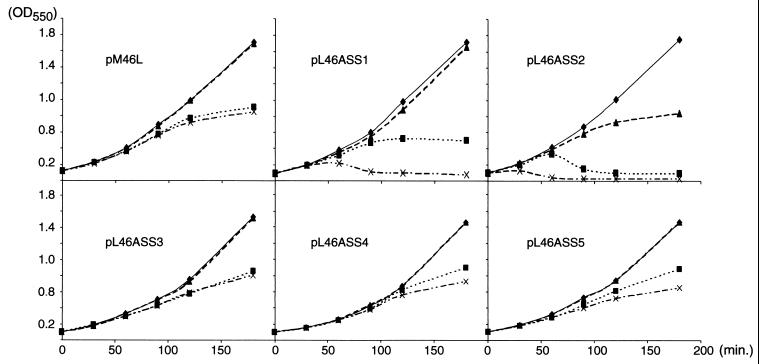

FIG. 4.

Effects of cephaloridine and aztreonam on the growth of strains expressing the α*, β*, and γ forms of PBP1b. When the OD550 reached 0.1 (t = 0), cultures of E. coli MC6-RP1, QCB1 or QCB1 harboring pPONB, pM46L, pR26ΔNt, or pM46ΔNt growing exponentially at 37°C were divided into four subcultures, and antibiotics were added as described in Materials and Methods. Growth was monitored by measuring the OD550 at 0, 30, 60, 90, 120, and 180 min. ⧫, Untreated control; ▴, cephaloridine (0.3 μg/ml); ■, aztreonam (0.5 μg/ml); ×, cephaloridine and aztreonam.

As expected, QCB1 lysed promply after the addition of either cephaloridine or aztreonam (11, 24). On the contrary, QCB1(pPONB) cells grew normally in the presence of cephaloridine and grew as filaments when aztreonam, alone or in combination with cephaloridine, was added to the medium. QCB1(pM46L) showed patterns of growth that were indistinguishable from those of QCB1(pPONB) according to OD550 measurements (Fig. 4) and microscopic observations (not shown).

For both QCB1(pR26ΔNt) and QCB1(pM46ΔNt) strains, expressing PBP1bβ* or PBP1bγ, respectively, the rates of growth were similar with or without cephaloridine (Fig. 4), confirming that the two forms are able to fully complement the deletion of the ponB gene in strain QCB1. When cultivated with aztreonam in the medium, cells grew as filaments without noticeable cell lysis (not shown), but both strains stopped to grow when the OD550 reached 0.5, whereas cells expressing PBP1bα* grew to an OD550 of 0.8 and further elongated at a reduced rate. The most unexpected result was the lytic effect of aztreonam in combination with cephaloridine on cells expressing PBP1bβ* or PBP1bγ only (Fig. 4). Cell lysis (confirmed by microscopic observations) took place 30 min after the addition of antibiotics to the medium.

Thus, after simultaneous inactivation of PBP1a and PBP3 with both cephaloridine and aztreonam, cells expressing PBP1bα* still grew as filaments, whereas cells expressing either PBP1bβ* or PBP1bγ lysed. Although the β* and γ mutant proteins were expressed at levels significantly lower than the wild-type protein from the pPONB plasmid, they were produced at higher levels than the wild-type PBP1b in the MC6-RP1 strain (Fig. 2B, lane 7). Since this strain exhibits growth curves which are essentially identical to the ones obtained with QCB1(pPONB), the differences between the wild-type and the β* and γ mutant proteins are not due to a difference in the level of expression. Moreover, since the mutants can sustain normal growth in the absence of antibiotics and since all of the mutant proteins can bind fluorescent penicillin, it can be assumed that the mutations have no significant impact on the folding and enzymatic activity of the periplasmic domain. Our data thus hint at a specific interaction of PBP1b with PBP3 in murein synthesis which requires a full-length cytoplasmic domain of PBP1b and for which PBP1b cannot be replaced by PBP1a. PBP1b could, for example, be recruited to the septation complex via its cytoplasmic domain, while this would not be the case for the elongation complex.

Alanine stretch scanning of the first 25 residues of PBP1bα yields mutant proteins with different in vivo activities.

To further explore the putative role played by residues M1 to R25 in the effects described above, we have used the alanine-stretch-scanning (ASS) method (23). Four plasmids (pL46ASS1 to -4) have been constructed from plasmid pM46L and transformed in strain QCB1. Each construct expressed an ASS mutant harboring sequential substitutions of six successive residues by alanines (Fig. 1).

Western blot analysis revealed that mutants ASS3 and ASS4 were produced at the same level as the wild-type protein in bacterial cells and efficiently bound fluorescent penicillin, indicating a proper folding and a functional transpeptidase activity (Fig. 5, lanes 5 and 6). Mutant ASS1 was expressed in QCB1 at approximately half the level of the wild-type α* and still bound fluorescent penicillin (Fig. 5, lanes 3). Mutant ASS2 was expressed at the lowest level and had a weak but detectable penicillin-binding activity (Fig. 5, lanes 4).

FIG. 5.

ASS mutants of PBP1bα. (A) Production of the ASS mutants of PBP1bα. Membrane fractions from QCB1 (10 μg, lane 1) or QCB1 transformed with pM46L (10 μg, lane 2), pL46ASS1 (20 μg, lane 3), pL46ASS2 (20 μg, lane 4), pL46ASS3 (10 μg, lane 5), pL46ASS4 (10 μg, lane 6), or pL46ASS5 (10 μg, lane 7) were analyzed by Western blotting using the anti-tag 12CA5 antibody. (B) Binding of 6-APA-FLU by the ASS mutants. Membrane fractions (100 μg) from QCB1 (lane 1) or QCB1 transformed with pM46L (lane2), pL46ASS1 (lane 3), PL46SS2 (lane 4), pL46ASS3 (lane 5), pL46ASS4 (lane 6), or pL46ASS5 (lane 7) and from MC6-RP1 (lane 8) were incubated with 6-APA-FLU and analyzed by Western blotting with an antifluorescein antibody. 1a, PBP1a mutant; 1b, PBP1b mutant.

We then studied the effect of aztreonam and cephaloridine on the morphology and growth of QCB1 expressing the different ASS mutants (Fig. 6). For QCB1 cells expressing either ASS3 or ASS4, results were identical to those obtained with cells expressing PBP1bα*. Basically, they grew normally with cephaloridine and filamented when aztreonam, alone or in combination with cephaloridine, was added to the medium (Fig. 6). The similar phenotype of cells expressing mutants ASS3, ASS4, and PBP1bα* suggests that residues K14 to R25 are not responsible for the differences observed between strains expressing the α*, β*, and γ forms of PBP1b.

FIG. 6.

Effects of cephaloridine and aztreonam on the growth of strains expressing the ASS mutants of PBP1bα. When OD550 reached 0.1 (t = 0), cultures of E. coli QCB1 harboring pM46L, pL46ASS1, pL46ASS2, pL46ASS3, pL46ASS4, or pL46ASS5 growing exponentially at 37°C were divided into four subcultures, and antibiotics were added as described in Materials and Methods. Growth was monitored by measuring the OD550 at 0, 30, 60, 90, 120, and 180 min. ⧫, Untreated control; ▴, cephaloridine (0.3 μg/ml); ■, aztreonam (0.5 μg/ml); ×, cephaloridine and aztreonam.

In contrast, substitution of residues A2 to E7 in mutant ASS1 resulted in a phenotype identical to the one obtained with QCB1 expressing PBP1bβ* or PBP1bγ mutants. While adding cephaloridine to the culture did not affect cell growth, the addition of aztreonam alone led to filamentation and had a lytic effect when combined with cephaloridine (Fig. 6). Although mutant ASS1 was produced at a lower level in bacteria than wild-type PBP1b from pPONB, it was still produced at a higher level than the wild-type protein in strain MC6-RP1 (Fig. 5B, lane 8). Thus, as for PBP1bβ* and PBP1bγ, this result cannot solely be explained by a lower production of the mutant. This pinpoints residues A2 to E7 as being required for a fully functional multienzyme complex for peptidoglycan synthesis.

Substitution of amino acids P8 to G13 had a drastic impact on the behavior of cells. Indeed, the addition of aztreonam was always lytic for strain QCB1 expressing mutant ASS2. Furthermore, the presence of cephaloridine in the culture had a significant impact on the growth curve, indicating that ASS2 only weakly complements the deletion of ponB (Fig. 6). However, microscopic observations performed 180 min after the addition of the antibiotic showed that cells continued to grow normally, although at a lower rate, without lysis or filamentation. Assuming that the cytoplasmic domain does not influence the folding of the periplasmic domain once it has been translocated to the periplasm, the low level of activity of this mutant is likely to be caused by an improper membrane localization and degradation.

To further characterize the amino acids responsible for the ASS2 phenotype, we made a partial revertant, ASS5, wherein residues A8 to A13 of ASS2 were replaced by the A8AARKG13 sequence (Fig. 1). This mutant was well produced in cells and bound fluorescent penicillin as efficiently as the wild type (Fig. 5, lanes 7). When the strain harboring mutant ASS5 was assayed for growth with cephaloridine and aztreonam, the cells exhibited the same response as those expressing PBP1bα* (Fig. 6), indicating that this mutant was fully active in vivo and complemented both the ponB deletion and the PBP1a inhibition in strain QCB1.

Residues R10K11G13 are therefore major determinants for the translocation of full-length PBP1b either through intramolecular or intermolecular interactions, since their mutation leads to a folding “dead end,” but are not required per se for membrane anchoring of the protein since PBP1bδ, which is deleted for the whole cytoplasmic domain, folds correctly and is functional both in vitro and in vivo. A simple hypothesis to explain this apparent contradiction could be that the deletion mutant, PBP1bδ, is translocated across the membrane by a process different from the one used by the full-length protein, as has been shown for other proteins (8, 27).

Implication for the multienzyme complex hypothesis.

It is speculated that synthesis and insertion of new peptidoglycan strands into the older murein sacculus are carried out by multienzyme complexes during cell elongation and the formation of the septum. Furthermore, earlier studies reported that PBP1b is able to dimerize, in agreement with the multienzyme hypothesis which predicts that PBP1b acts as a dimer within these complexes. It has also been shown that only homodimers, α-α, β-β, or γ-γ, occur (40), raising the question of a putative role for the cytoplasmic domain of PBP1b.

Cell filamentation triggered by aztreonam has been shown to result from inactivation of the PBP3 transpeptidase activity which is necessary for the septum formation. According to the multienzymatic complex hypothesis, one of the two bifunctional PBPs (PBP1a or PBP1b) cooperates with PBP3 during septum formation, with the former, being a bifunctional enzyme, involved in both transglycosylation and transpeptidation and the latter only involved in transpeptidation. In a situation where transglycosylation occurs while PBP3 is inactivated, one can imagine that incorporation of newly synthesized glycan chains which are unlinked or badly linked to old glycan strands would result in lysis. The idea that the transglycosylase activity of PBP1b could be coupled with the transpeptidase activity of PBP3 has been developed in previous studies (32). Moreover, this hypothesis is consistent with our microscopic observations showing that before lysis most of the cells present bulges around their midpoints, suggesting that lysis occurs at the division site.

In this study, we established that the different forms of PBP1b, including the δ component, were able to preserve cell integrity in PBP1a-deficient cells. We also found that the expression of the β or the γ form alone is unable to prevent cell lysis after impairment of both PBP3 and PBP1a in strain QCB1, whereas expression of PBP1bα does prevent lysis. Cell lysis clearly requires the presence of impaired PBP3 in the multienzyme complex since a QCB1 strain harboring a thermosensitive PBP3 mutant protein elongates at a nonpermissive temperature instead of lysing (11).

Thus, the fact that synthesis of an osmotically stable peptidoglycan after inactivation of PBP3 requires the presence in cells of either the full-length PBP1b or a deleted form of PBP1b (β or γ) plus PBP1a hints at different interactions between the various PBP1 components and PBP3 or another protein involved in the septation multienzyme complex. Whatever the precise nature of these interactions, ASS mutagenesis shows that they involve the six N-terminal residues of PBP1b. This is quite surprising since this is the part of the cytoplasmic domain which has the lowest number of charged residues. Nonetheless, we now have both sequence information and a phenotype that will allow us to search for the putative partners of PBP1b at the molecular level. These findings also underline the intricate relationship between the various PBPs within the murein synthesis complexes.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asoh S, Matsuzawa H, Matsuhashi M, Ohta T. Molecular cloning and characterization of the genes (pbpA and rodA) responsible for the rod shape of Escherichia coli K-12: analysis of gene expression with transposon Tn5 mutagenesis and protein synthesis directed by constructed plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:10–16. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.10-16.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Botta G A, Buffa D. Murein synthesis and beta-lactam antibiotic susceptibility during rod-to-sphere transition in a pbpA(Ts) mutant of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1981;19:891–900. doi: 10.1128/aac.19.5.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bramhill D. Bacterial cell division. Annu Rev Dev Biol. 1997;13:395–424. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broome-Smith J K, Edelman A, Yousif S, Spratt B G. The nucleotide sequences of the ponA and ponB genes encoding penicillin-binding protein 1A and 1B of Escherichia coli K12. Eur J Biochem. 1985;147:437–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb08768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bush K, Smith S A, Ohringer S, Tanaka S K, Bonner D P. Improved sensitivity in assays for binding of novel beta-lactam antibiotics to penicillin-binding proteins of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:1271–1273. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.8.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chalut C, Rémy M-H, Masson J-M. Disulfide bridges are not involved in penicillin-binding protein 1b dimerization in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2970–2972. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.9.2970-2972.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denome S A, Elf P K, Henderson T A, Nelson D E, Young K D. Escherichia coli mutants lacking all possible combinations of eight penicillin-binding proteins: viability, characteristics, and implications for peptidoglycan synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3981–3993. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.13.3981-3993.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fekkes P, Driessen A J. Protein targeting to the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:161–173. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.1.161-173.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galleni M, Lakaye B, Lepage S, Jamin M, Thamm I, Joris B, Frère J M. A new, highly sensitive method for the detection and quantification of penicillin-binding proteins. Biochem J. 1993;291:19–21. doi: 10.1042/bj2910019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.García del Portillo F, de Pedro M A, Joseleau-Petit D, D'Ari R. Lytic response of Escherichia coli cells to inhibitors of penicillin-binding proteins 1a and 1b as a timed event related to cell division. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:4217–4221. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.8.4217-4221.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.García del Portillo F, de Pedro M A. Differential effect of mutational impairment of penicillin-binding proteins 1A and 1B on Escherichia coli strains harboring thermosensitive mutations in the cell division genes ftsA, ftsQ, ftsZ, and pbpB. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5863–5870. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.5863-5870.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.García del Portillo F, de Pedro M A, Ayala J A. Identification of a new mutation in Escherichia coli that suppresses a pbpB (Ts) phenotype in the presence of penicillin-binding protein 1B. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1991;68:7–13. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(91)90386-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goffin C, Ghuysen J-M. Multimodular penicillin-binding proteins: an enigmatic family of orthologs and paralogs. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1079–1093. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1079-1093.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henderson T A, Dombrosky P M, Young D K. Artifactual processing of penicillin-binding proteins 7 and 1b by the OmpT protease of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:256–259. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.1.256-259.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Höltje J V. A hypothetical holoenzyme involved in the replication of the murein sacculus of Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 1996;142:1911–1918. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-8-1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Höltje J V. Molecular interplay of murein synthases and murein hydrolases in Escherichia coli. Microb Drug Resist. 1996;2:99–103. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1996.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Höltje J V. Growth of the stress-bearing and shape-maintaining murein sacculus of Escherichia coli. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:181–203. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.1.181-203.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishino F, Mitsui K, Tamaki S, Matsuhashi M. Dual enzyme activities of cell wall peptidoglycan synthesis, peptidoglycan transglycosylase and penicillin-sensitive transpeptidase, in purified preparations of Escherichia coli penicillin-binding protein 1A. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1980;97:287–293. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(80)80166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kato J, Suzuki H, Hirota Y. Overlapping of the coding regions for alpha and gamma components of penicillin-binding protein 1b in Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;196:449–457. doi: 10.1007/BF00436192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kato J, Suzuki H, Hirota Y. Dispensability of either penicillin-binding protein-1a or -1b involved in the essential process for cell elongation in Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1985;200:272–277. doi: 10.1007/BF00425435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lakaye B, Damblon C, Jamin M, Galleni M, Lepage S, Joris B, Marchand-Brynaert J, Frydrych C, Frère J M. Synthesis, purification and kinetic properties of fluorescein-labelled penicillins. Biochem J. 1994;300:141–145. doi: 10.1042/bj3000141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lefèvre F, Rémy M-H, Masson J-M. Alanine-stretch scanning mutagenesis: a simple and efficient method to probe protein structure and function. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:447–448. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.2.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lefèvre F, Rémy M-H, Masson J-M. Topographical and functional investigation of Escherichia coli penicillin-binding protein 1b by alanine stretch scanning mutagenesis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4761–4767. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.15.4761-4767.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Massova I, Mobashery S. Kinship and diversification of bacterial penicillin-binding proteins and β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1–17. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nanninga N. Morphogenesis of Escherichia coli. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:110–129. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.1.110-129.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newitt J A, Ulbrandt N D, Bernstein H D. The structure of multiple polypeptide domains determines the signal recognition particule targeting requirement of Escherichia coli inner membrane proteins. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4561–4567. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.15.4561-4567.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suzuki H, Nishimura Y, Hirota Y. On the process of cellular division in Escherichia coli: a series of mutants of E. coli altered in the penicillin-binding proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:664–668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.2.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suzuki H, van Heijenoort Y, Tamura T, Mizoguchi J, Hirota Y, van Heijenoort J. In vitro peptidoglycan polymerization catalysed by penicillin binding protein 1b of Escherichia coli K-12. FEBS Lett. 1980;110:245–249. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(80)80083-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suzuki H, Kato J, Sakagami Y, Mori M, Suzuki A, Hirota Y. Conversion of the alpha component of penicillin-binding protein 1b to the beta component in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:891–893. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.2.891-893.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tamaki S, Nakajima S, Matsuhashi M. Thermosensitive mutation in Escherichia coli simultaneously causing defects in penicillin-binding protein-1Bs and in enzyme activity for peptidoglycan synthesis in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5472–5476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Heijenoort Y, Gomez M, Derrien M, Ayala J, van Heijenoort J. Membrane intermediates in the peptidoglycan metabolism of Escherichia coli: possible roles of PBP 1b and PBP 3. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3549–3557. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.11.3549-3557.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vollmer W, von Rechenberg M, Höltje J V. Demonstration of molecular interactions between the murein polymerase PBP1B, the lytic transglycosylase MltA, and the scaffolding protein MipA of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:6726–6734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang L, Khattar M K, Donachie W D, Lutkenhaus J. FtsI and FtsW are localized to the septum in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2810–2816. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.11.2810-2816.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weiner M P, Costa G L, Schoettlin W, Cline J, Mathur E, Bauer J C. Site-directed mutagenesis of double-stranded DNA by the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1994;151:119–123. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90641-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weiss D S, Chen J C, Ghigo J M, Boyd D, Beckwith J. Localization of FtsI (PBP3) to the septal ring requires its membrane anchor, the Z ring, FtsA, FtsQ, and FtsL. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:508–520. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.2.508-520.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wientjes F B, Nanninga N. On the role of the high molecular weight penicillin-binding proteins in the cell cycle of Escherichia coli. Res Microbiol. 1991;142:333–344. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(91)90049-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson I A, Niman H L, Houghten R A, Cherenson A R, Connolly M L, Lerner R A. The structure of an antigenic determinant in a protein. Cell. 1984;37:767–778. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90412-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yousif S Y, Broome-Smith J K, Spratt B G. Lysis of Escherichia coli by beta-lactam antibiotics: deletion analysis of the role of penicillin-binding proteins 1A and 1B. J Gen Microbiol. 1985;131:2839–2845. doi: 10.1099/00221287-131-10-2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zijderveld C A, Aarsman M E, den Blaauwen T, Nanninga N. Penicillin-binding protein 1B of Escherichia coli exists in dimeric forms. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5740–5746. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.18.5740-5746.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zijderveld C A, Aarsman M E, Nanninga N. Differences between inner membrane and peptidoglycan-associated PBP1B dimers of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1860–1863. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.7.1860-1863.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]