Highlights

-

•

Hosting governments were moderately successful in providing health services to Syrian refugees through existing national health systems.

-

•

Coverage and quality of care remain suboptimal and continuity is often interrupted due to inadequate implementation of national NCD guidelines, major government policy changes and UNHCR policy changes in cost sharing, eligibility, and vulnerability criteria which made the health system difficult to navigate. The latter are related to the lack of financing for NCDs at global level.

-

•

There is a need for evidence-based guidelines and effective implementation models for continued NCD care in protracted emergency settings.

-

•

Innovative financing solutions and increased advocacy for funding and prioritization of NCD care for refugees need to be envisioned.

-

•

Strengthening existing national health systems and striving for equity in achieving universal health coverage for both nationals of host countries and refugees is imperative.

Keywords: Syria, Non-communicable diseases, Humanitarian crises, Health systems

Abbreviations: CVD, Cardiovascular Diseases; NCD, Non-Communicable Disease; NGO, Non-Governmental Organization; SOP, Standard Operating Procedure; UN, United Nations; UNHCR, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees; VASyR, Vulnerability Assessment of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon

Abstract

Introduction

Since the start of the Syrian conflict in 2011, Jordan and Lebanon have hosted large refugee populations, with a high pre-conflict burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). We aimed to explore NCD service provision to Syrian refugees in these two host countries and to identify lessons learned that may inform the global response to the changing health needs of refugees.

Methods

Between January 2017 and June 2018, we conducted 36 in-depth interviews with stakeholders from Jordan and Lebanon, as well as global stakeholders, to understand the context, the achievements, gaps and priorities in the provision and uptake of NCD prevention, testing and treatment services to Syrian refugees.

Findings

Both countries succeeded in embedding refugee health care within national health systems, yet coverage and quality of NCD health services offered to Syrian refugees in both contexts were affected by under-funding and consequent policy constraints. Changes in policies relating to cost sharing, eligibility and vulnerability criteria led to difficulties navigating the system and increased out-of-pocket payments for Syrians. Funding shortages were reported as a key barrier to NCD screening, diagnosis and management, including at the primary care level and referral from primary to secondary healthcare, particularly in Lebanon. These barriers were compounded by suboptimal implementation of NCD guidelines and high workloads for healthcare providers resulting from the large numbers of refugees.

Conclusions

Despite the extraordinary efforts made by host countries, provision and continuity of high quality NCD services at scale remains a tremendous challenge given ongoing funding shortfalls and lack of prioritization of NCD care for refugees. The development of innovative, effective and sustainable solutions is necessary to counter the threat of NCDs.

1. Introduction

As the numbers of forcibly displaced people reach historic highs, displacement has become an increasingly protracted phenomenon. By 2019, 77% of all refugees had been displaced for more than five years (UNHCR, 2020), a situation worsened by the COVID pandemic (Al-Oraibi et al., 2021; Yadav et al., 2020). The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) defines protracted refugee situations as those where at least 25,000 refugees have been in exile ‘for five years or more after their initial displacement, without immediate prospects for implementation of durable solutions’(UNHCR Executive Committee of the High Commissioner's Programme, 2009). An escalating number of people find themselves in this limbo, unable to return home but without the rights of permanent residence abroad.

Protracted displacement has a significant impact on health systems, health services and humanitarian responses. As the epidemiological transition advances in many low-income countries, and more middle-income countries are prone to humanitarian crises, the non-communicable diseases (NCDs) burdens are increasing in populations affected by forced displacement (Spiegel et al., 2010). People living with NCDs are at greater risk of vulnerability given disruptions in access to adequate nutrition, medications and follow-up, leading to long-term social and health implications (Demaio et al., 2013). The traditional humanitarian architecture did not consider NCDs in its standard responses, however this increasing burden calls for integrating prevention and continuity of care for NCDs into humanitarian responses (Perone et al., 2017).

The Syrian armed conflict which began in 2011 has displaced 6.7 million people, most of whom are chronically residing in neighbouring countries (UNHCR, 2020). Jordan and Lebanon host the largest numbers of refugees relative to their national populations in the world; 1 in 14 people in Jordan and 1 in 7 people in Lebanon is a refugee (UNHCR, 2020). The large influx of Syrian refugees placed significant pressures on existing national services in these neighbouring countries, particularly in health. In Jordan and Lebanon, Ministries of Health and the UNHCR coordinated with a diverse group of healthcare providers including international and local non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to deliver health services to Syrian refugees (Akik et al., 2019).

Given the context, complexity and chronicity of displacement (UNHCR, 2018b; UNHCR et al., 2020), the Jordanian and Lebanese healthcare systems were confronted with the need to provide far more than emergency and basic health services to Syrian refugees. Prior to the war, 77% of deaths in Syria were attributed to NCDs, with cardiovascular diseases (CVD) being the leading cause of all-age mortality (World Health Organization, 2011). Unsurprisingly, Syrian refugees in neighbouring host countries have a high prevalence of NCDs, including hypertension, CVD, diabetes, renal disease, chronic lung disease and cancers (Akik et al., 2019; Al-Oraibi et al., 2022). Providing displaced people with continuity of care for chronic NCDs is programmatically, logistically and financially challenging (Akik et al., 2019; Alawa et al., 2019a; El Arab and Sagbakken, 2018).

This study explores NCD service provision to Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon. We used qualitative methods to identify factors that influenced the ability of host country health systems to ensure that Syrian refugees had access to high-quality NCD-related health services in 2017–2018, and identify lessons learned that may inform the global response to the changing health needs of refugees.

2. Methods

Thirty-six in-depth interviews were conducted with stakeholders from Jordan (n = 13), Lebanon (n = 18) and global institutions (n = 5) between January 2017 and June 2018. Participants were selected via purposive followed by snowball sampling and included representatives of national governments, managers and health providers from local and international NGOs, staff from United Nations (UN) agencies and academic institutions. Data collection was concluded when theoretical saturation was achieved with no new themes emerging from interviews.

The interview guide included 25 questions focused on understanding the context, achievements, gaps and priorities in the provision and uptake of NCD services to Syrian refugees (Supplemental file 1). Interviews were conducted either in person or via phone/Skype, in Arabic or English depending on participant preference, and took approximately 35–45 min. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed by research staff with native-level fluency in Arabic and/or English. We adopted the interpretative approach for data analysis. Transcripts were analysed using thematic analysis. Both inductive and deductive approaches were used by applying predetermined codes to the data, and allowing for new codes to emerge. Two researchers discussed convergent and divergent aspects of the analyses in order to obtain a final thematic framework. We used the WHO system framework to analyze the data. The six WHO health systems building blocks – service delivery; health workforce; information; medical products, vaccines and technologies; financing and leadership/governance – contribute to the strengthening of health systems by improving coverage and quality of care provided, which in turn improves health outcomes (World Health Organization, 2010). We identified relationships among and between these categories/blocks, and used these to describe barriers and facilitators in the coverage and quality of NCD services provided to Syrian refugees. Illustrative quotes were extracted to provide examples of key themes. The results were reviewed at an expert meeting convened in Beirut, Lebanon, in August 2018. Stakeholders working with Syrian refugees from Jordan and Lebanon discussed and validated the results of the thematic analysis, and these exchanges contributed to the discussion points presented here. The Institutional Review Boards of Columbia University (protocol #AAAQ9688, #AAAQ9704), the American University of Beirut in Lebanon and the King Hussein Cancer Center in Jordan approved the research study protocol. Verbal informed consent was given by all participants. In order to ensure confidentiality of study respondents, no identifying information was collected and all data was kept confidential. Audio files were kept in password-protected folders and erased following transcription. Transcripts did not include identifying information.

3. Findings

The 36 in-depth interviews (Table 1) highlighted that the key to successful provision of NCD services to Syrian refugees in Lebanon and Jordan was the inclusion of refugee care into existing national health care systems and structures. Although eligibility varied over time, and equity issues remained, the main providers of NCD prevention, diagnosis and treatment were the hosting Ministries of Health, through various humanitarian funding mechanisms largely led by UNHCR. Key themes are illustrated in Table 2; coverage and quality of NCD health services offered to Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon were affected by under-funding and consequent changing health-access related policies.

Table 1.

Interview respondents by country and type of institution.

| Jordan | Lebanon | Global | |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Governments | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Local NGOs | 4 | 6 | 0 |

| International NGOs and UN agencies | 7 | 10 | 2 |

| Academic institutions | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Total | 13 | 18 | 5 |

Table 2.

Facilitators and barriers in the coverage and quality of care provided to Syrian refugees in both contexts unless specified.

| Facilitators | Barriers | |

| Service delivery | Eligibility of Syrian refugees to access national health systems | Difficulty navigating the health system Lack of guidelines and standard operating procedures for NCDs in emergency settings |

| Health workforce | Training/capacity building of healthcare workers | |

| Medical products, vaccines and technologies | Shortages due to poor management at the health centre level (Lebanon) Unavailability of some medications for either nationals or refugees (Jordan) |

|

| Financing | Limited funding for diagnostics and medications Out of pocket cost to patients with NCDs |

|

| Leadership/governance | Coordination between health partners (Jordan) | Changing eligibility policies Limited advocacy for/prioritization of NCDs Lack of coordination between key stakeholders (Lebanon) |

3.1. Policies affecting health access of Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon

3.1.1. Eligibility of Syrian refugees to access national health systems

By channelling its health care assistance through the public health system, UNHCR aligned with Jordanian and Lebanese governmental policies that endorsed Syrian refugees’ access to health care in the context of existing national systems which include government supported NGO-managed primary healthcare centers. This approach was perceived by most respondents to be a success in the refugee response:

“Integration [of Syrian refugees] within the primary health care system was quite successful, actually much more successful than the integration of the Lebanese population in the primary health care centers. […] The Syrian population is accustomed to going to governmental centers that [provide] primary health care.” – Academic key informant, Lebanon

Syrian refugees’ access to healthcare was, by default, limited to services available for nationals of Jordan and Lebanon. This was highlighted by respondents from both countries who mentioned the lack of screening for some NCDs in Jordan and lack of regular follow-up for patients suffering from NCDs in Lebanon as health service gaps for both nationals and Syrian refugees:

“Breast examination, mammography, screening for cancers are not available because they are not available for the nationals. […] there is no systematic screening system.” – Local NGO key informant – Jordan

Most respondents perceived services to be equally available to host populations and refugees, although in Lebanon, many citizens have additional private health insurance and national health insurance that enables access to the private healthcare system, not available to refugees. In Jordan, one respondent expressed a perception of Syrians receiving better quality services than locals:

‘’Are we comparing this [Syrian refugees ‘access to NCD health services] to our population? Or are we comparing this to [the] absolute? Or are we comparing this to what the system should be? […] I think Syrian refugees in Jordan get much more advanced public health and primary care than the Jordanians.’’ – Local NGO key informant – Jordan

Access to universal health coverage for nationals and non-nationals was suggested by some respondents as the way forward in the health response to this protracted crisis as it would help address many access barriers:

“We were able to integrate [Syrian refugees] in diabetes and cardiovascular system because the system was there and able to be integrated. So, at this point Syrian refugees and all refugees have been in Lebanon long enough to start posing their problems as part of the problems of health care in general in Lebanon. […] We need to demand universal health care coverage for everybody in Lebanon.” – Academic key informant – Lebanon

3.1.2. Changing policies relating to health access

Difficulty navigating the system: Throughout the protracted Syrian crisis, the health response in Jordan and Lebanon underwent several policy changes. These changing policies resulted in a health system that was difficult to navigate, not only by Syrian refugees but also by NGOs, as described by several respondents:

“[Navigating the system] is still an issue [for patients]. […] A while ago, I had someone over the phone from [an international NGO] […] it's hard even for the NGOs to catch up with the system.” – UN key informant, Jordan

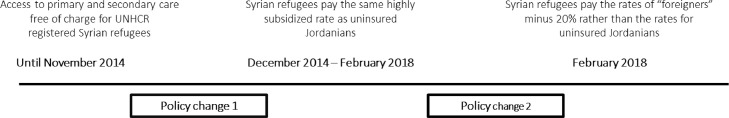

Major governmental policy changes in Jordan: Despite their eligibility to access national healthcare systems, Syrian refugees in Jordan witnessed two major policy changes affecting the set of criteria that allows them to access health services. As a result, between November 2014 and February 2018, Syrian refugees moved from accessing primary and secondary healthcare services free of charge to having to pay the rates of “foreigners” to access healthcare (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Major governmental policy changes affecting healthcare access in Jordan between 2014 and 2018.

These policy changes were perceived as a major barrier to accessing care. Informants reported an increased need for Syrian refugees to pay for health services out of pocket, leading to an unsurprising drop in the number of Syrian refugees accessing healthcare services and a greater dependence on support from aid agencies:

“The fact that they've lost their free medical services […] has disadvantaged a lot of the refugees from getting the care and it is now dependent on the international NGOs and the UN agencies to be able to cover up for that and provide for that.” – Local NGO key informant, Jordan

UNHCR policy changes: cost sharing, eligibility and vulnerability criteria: The under-funding of the regional appeal over the years forced UNHCR to implement a healthcare cost-sharing scheme, raising worries among the interviewed national and international NGOs about refugees’ ability to access care and more specifically diagnostic tests, one of the main pillars of NCD detection:

‘’We have the list of the issues that are covered so we tell the patients: go there and you will most likely be accepted by the UN so go and manage with the 75%. […] We still have to work on getting the 25% that remain.’’ – International NGO key informant, Lebanon

“There are many diagnostic procedures that need to be available but we're unable to cover them.” – International NGO key informant, Lebanon

3.2. Financing: the main barrier to quality NCD healthcare coverage?

3.2.1. Prioritization and financing of NCDs

Most implementers and decision makers reported the need for NCDs to be acknowledged as a public health priority, both within the limits of the refugee response and outside:

‘’NCDs and chronic diseases are very important, whether to Syrian refugees or Jordanians. […] In Jordan; it should be a [priority] issue, regardless of the nationality. […] Unfortunately, it all boils down to … financial allocation on the policy side, and … the struggling priorities. […] This needs to be pushed up the priority ladder.” – Local NGO key informant, Jordan

Resource allocation for NCDs was reported to be difficult for various reasons including policymakers and/or programme developers not having a good understanding of the complexity of NCDs, and weak advocacy:

“It is not that sexy to fund for NCDs and it is much more pulling at the heartstrings to fund for things for pregnant women and children. And we are guilty of [that] as well because we are responsible for prioritizing these populations and the funds required to cover those diagnostic costs… but if one thing has to be cut, it has to be NCDs.’’ – International NGO key informant, Lebanon

An international academic highlighted the problem with comparing the financing of NCDs to financing of care for maternal and child health and communicable diseases:

“We get into these dreadful arguments about “the cost” of doing X. […] When you start plotting out the cost of doing a fine-needle aspiration for a breast lump, […] in comparison to treating a child with diarrheal diseases […], the costs […] are vastly more. And the problem is, we're comparing apples with oranges, […] it's very easy to deprioritize by simply [focusing] on the macro costs, without doing any of the balanced costs utility analysis that's required.” – Global key informant

In fact, several interviewees suggested a more coordinated funding approach where the effectiveness and costs of interventions should be evaluated at the decision-making level, and channelled directly to the programmatic level:

“There needs to be a more coordinated funding approach to allow a […] more rational approach to allocation of these resources […]. Given the scale of the costs of NCD care, we need to take a […] more thorough approach to how we cost it. […] We know that most crises are protracted, and that ideally we should be taking a longer-term approach to care […] by bringing in longer-term intervention studies, evaluation studies, cost-effectiveness studies.” – Global key informant

“It is about being more efficient about the funding also because a lot of it is being consumed in intermediaries, so money is passing from an international donor or from the UN to an NGO to a service provider. What needs to be done in the long term is to remove the middleman, [and] start direct financing to the provider. We could have an efficiency of around 30%.” – UN key informant - Lebanon

3.2.2. Implications for continuity of NCD care

Financial barriers at primary healthcare level: Several local and international NGOs expressed their dissatisfaction with their inability to screen for NCDs, confirm diagnosis or provide regular NCD management follow-up due to lack of funding:

‘’There is no support for the center when it comes to the diabetes testing machines. The strips […] are expensive. Most of the centers are stopping [the screening] because they can't purchase [the strips].’’ – Local NGO key informant, Lebanon

“There are periodical lab tests to do, and this requires a lot of wherewithal. Currently we are not able to provide them all as required. If we have consumables and more lab equipment then we can do them really at the right time for the follow up” – International NGO key informant, Jordan

Secondary and tertiary healthcare levels: Several respondents from Lebanon mentioned lack of funding as one of the challenges for referral from primary to secondary healthcare levels. This observation came out as a concern particularly in the Lebanese context rather than the Jordanian one:

“This level between primary care and cases [requiring referral] in hospitals, there is this kind of difficult area where people maybe have to come up with money, if it is to have a CT or an MRI scan to confirm the diagnosis. […] In terms of additional funding for this at the moment […] it is definitely another gap.” – UN key informant, Lebanon

Lack of funding for hospital care for NCDs, such as cancer and chronic renal failure, was reported by several respondents:

“There are huge gaps [for hospital care] and this is due to funding. […] Although we are [able] to cover some cancer cases, it is usually cases that need a surgical intervention [that] will lead to good outcome, but chemotherapy [or] radiotherapy [is] not covered; and the big one is renal dialysis for chronic renal failure. Some NGOs have been able to step in and provide some support, but the sustainability is very precarious because the funding is never even guaranteed on an annual basis. [It] is a huge challenge to try [and] program when your outlook on funding is so short.” – UN key informant, Lebanon

One respondent from Lebanon explained the dilemma faced by decision-makers with regards to funding allocation, in settings where resources are scarce:

“This is the grey zone… when you have very limited resources. Do you channel it, do you take it away from the people who need more advanced life-saving care and push it all to primary health care?” – UN key informant, Lebanon

These funding gaps have led some international NGOs to look for alternative strategies to cover the costs of some specific under-funded diagnostic tests or health conditions, such as short-term grants for vertical programs:

“We have different programs from different grants so [with] certain programs we are able to cover for chronic patients. […] This is the difference from one center to another; the coverage for diagnostic test of chronic patients [varies] from one grant to another.” – International NGO key informant, Lebanon

Individual-level repercussions: Not having enough financial support meant that some Syrian refugees could not access health services nor undergo necessary diagnostic testing, even if that only required paying a relatively small amount of money, as reported by respondents:

“The continuity of treatment for NCDs […] Who pays for the big issues: access so the transport, […] investigations and […] medications. Even if a doctor's consultation is free there is a lot more that needs to be paid for. […] If you have to choose you are not going to spend [money] for hypertension because you have to use the money elsewhere.” – Global key informant

It also meant that healthcare providers felt powerless when they found themselves face-to-face with a patient who was unable to pay out-of-pocket to cover the cost of healthcare:

“We tell the patient: You do have a heart problem, but in order to know what the problem is, we need to run this or that test. But the patient is unable to pay and we are unable to find the right funding.” – Local NGO key informant, Lebanon

3.3. Coordination: a strength or a weakness?

The complexity of the health response was further aggravated by insufficient coordination among health actors, as described by respondents from Lebanon:

“People will prefer to go to international NGOs rather than go to the existing system in place and then this NGO stops the program and people will be left with no follow up. The complexity of the situation and complex diversity of the interlocutors on the ground make it difficult to have one system and one flow.” – UN key informant, Lebanon

On the other hand, coordination in Jordan was perceived to be generally positive:

“There's coordination on the ground between all agencies. The Ministry of Health is on the top of this health system […] [and] the coordination between health partners. They were able to come up with health systems for the refugees at the level where they work.” – Local NGO key informant, Jordan

Yet this perception differed around coordination outside camps compared to inside camps. One respondent working outside camps in Jordan thought that poor coordination was the reason behind the lack of follow-up for patients with NCDs and consequent inadequate continuity of care:

“There are no NGOs that do [follow-up investigations] or follow-up on medication provision and if possible systematic prevention of the complications. […] This is a big gap.” – UN key informant, Jordan

3.4. NCD management in emergencies: poorly implemented guidelines or lack of evidence-based/adapted response models?

Guidelines for NCD management exist in both host countries where Syrian refugees can access national health systems; yet their content, dissemination among health providers and implementation remain questionable

“There is no NCD for emergency. This is a new science that was created, [based] on [the] Syrian crisis. There was an essential package that was not recommended to be used. It needs a lot of update, creating new tools, manuals and other things. […] NCDs for the Syrian [crisis] were a very bad experience.” – Local NGO key informant – Jordan

“Integration of NCD management within the primary health care setting for the NGOs. […] We organized trainings for doctors and nurses at primary health care centers. We got [people] from the Ministry of Health and NGOs. This is also a success story.” – UN key informant, Jordan

“The [NCD] guidelines are in existence but how much are they actually implemented and monitored and followed is another question. […] Several trainings were done but for implementation to stick you need supervision, you do need regular follow up, you need orders to see if guidelines are being followed” – UN key informant, Lebanon

Yet an academic respondent highlighted challenges in the development of NCD guidelines in humanitarian crises settings

“[Development of NCD guidelines] is obviously fairly new for the humanitarian community. […] The new Sphere standards […] will include expanded NCD section, but generally they're never very detailed anyway… I think work is improving in that area. One area is probably still weak, the prevention of NCDs.” – Global academic key informant

3.5. Access to medication

While some local NGOs in Jordan and Lebanon reported shortages in medication supply due to poor inter-agency coordination around referrals, decision makers concluded that shortage of medication was not a major issue in the health response but rather due to poor quantification and stock management at the health center level in Lebanon, and the fact that some medications were not available for either nationals or refugees in the case of Jordan:

“A shortage could occur for one or two days due to the supply because […] we originally assume that there is X number of patients. However, due to the referral between the organisations without coordination [actual numbers are higher].” – Local NGO key informant, Jordan

“When refugees go to the Ministry of Health, they claim they have shortages in medications. […] There are things that are not available even for the average Jordanians at the Ministry of Health.’’ – UN key informant, Jordan

3.6. Health workforce: size and technical capacity

Many respondents considered capacity building of healthcare providers in Jordan and Lebanon to manage NCDs as one of the successes of the response:

“We were able to strengthen the key institution […] we are training key staffs to providing logistics and the resources, opening new wards […] providing […] specialized and sophisticated equipment” – UN key informant, Lebanon

However, even with their strong technical capacity, the limited number of healthcare providers compared to the high workload resulting from the influx of refugees was perceived to have a negative impact in both contexts on the quality of health services provided and the quality of NCD behavioural counselling specifically

“The lack of time maybe and capacity of doctors who see too many people … in the same day. They don't have the time or energy to sit with the patient and explain to them … how to take their medicine, what to eat, the importance of physical activity and how to control their smoking, and all of that.’’ – Local NGO informant, Jordan)

4. Discussion

This qualitative research with stakeholders from Jordan and Lebanon, as well as global stakeholders, revealed that both countries succeeded in embedding refugee health care within national health systems. However, coverage and quality of NCD health services offered to Syrian refugees in both contexts were reported to be suboptimal and affected by under-funding and consequent policy constraints. Changes in policies relating to cost sharing, eligibility and vulnerability criteria led to difficulties navigating the system and increased out-of-pocket payments for Syrians. Funding shortages were also reported as a key barrier to NCD screening, diagnosis and management, including at the primary care level and referral from primary to secondary healthcare, particularly in Lebanon. These barriers were compounded by suboptimal implementation of NCD guidelines and high workloads for healthcare providers resulting from the large numbers of refugees.

The eligibility of Syrian refugees to access national health systems was perceived as a successful approach in the refugee response. Yet as reported in the literature, ongoing challenges in both contexts such as the multiplicity of health system actors and increasing out of pocket payments highlight the need for continued efforts for improved integration of refugee communities (Saleh et al., 2022). In fact, strengthening existing national health systems and striving for universal health coverage for both nationals of host countries and refugees would facilitate health system resilience as well as improved health outcomes and efficiencies via early access to preventive and curative services (World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2019). Given that reducing modifiable risk factors is one of the key components of NCD control (World Health Organization, 2013), adopting preventive approaches in combination with curative ones should be a key pillar of NCD responses both for host communities and for refugees in protracted humanitarian crises. Only strong and resilient health systems could have accommodated the huge influx of people needing health services that occurred with the Syrian crisis.

However, our findings revealed that changing governmental and UN agencies led- policies had an impact on health access and more specifically coverage, including drops in the number of refugees accessing healthcare services and difficulty in navigating the system. The latter is in line with available literature that highlights the reported lack of clear guidance on eligibility criteria, referral processes and cost of health services among others in Jordan and Lebanon (Amnesty International, 2014; Ay et al., 2016; Strong et al., 2015; Akik et al., 2019). The navigation challenges have also been reported among Syrian refugees in Turkey who may not be well informed about available services and what services they are entitled to (Alawa et al., 2019b). In Jordan, the implications of the 2014 governmental policy change were highlighted by Amnesty International, revealing a 27% increase in the number of patients seeking treatment at the Jordan Health Aid Society, an organization which assists vulnerable Syrians in getting access to care (Amnesty, 2016). More recent evidence revealed that these policy changes have made care in the public sector largely inaccessible to Syrian refugees (McNatt et al., 2019). Furthermore, in a context where the regional emergency appeal has consistently been under-funded (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2020), UNHCR has had to make changes over the years to their Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for the referral care program in both host countries, including its healthcare cost sharing scheme. In Lebanon, 75% of costs exceeding the first 100 USD paid by the beneficiary is covered by UNHCR; and if the patient share reaches 800 USD, UNHCR covers all subsequent costs (UNHCR, 2018a).This cost-sharing scheme has been reported to affect access to care/coverage. Health service underutilization as a result of reduced subsidies has been reported in a study on cancer care among both Syrian and Lebanese patients in Lebanon where 79% of patients from both nationalities did not seek care for their condition due to lack of funds (Alawa et al., 2019a). In Jordan, the World Bank noted a 60% decrease in health service utilization two years after the co-payment policy was implemented (World Bank, 2017).

This study also highlighted the lack of prioritization and financing of NCDs in the Syrian refugee response and NCD healthcare provision due to limited understanding of the complexity of NCDs, weak advocacy as well as the focus on immediate needs such as maternal and child health and communicable diseases. These findings are in line with other studies where lack of prioritization of NCD healthcare provision was reported to be due to the focus on immediate needs especially injuries and control of infectious diseases within Syria; and other health services being considered more cost-effective (Garry et al., 2018). There was also a lack of a coordinated overall strategy to tackle NCDs on a national level (Garry et al., 2018). Our findings are also in line with a qualitative study where global experts reported that NCD care was underfunded and that provider organizations perceived NCD care as costly influencing their engagement in NCD care, and what they include in their package of NCD care (Ansbro et al., 2022).

As financial barriers are responsible for limiting refugees’ access to NCD care, and more specifically continuity of care, and in alignment of health emergency responses with the Sustainable Development Goals vision of ‘leaving no one behind’, innovative financing solutions need to be envisaged (Abubakar and Zumla, 2018). In fact, these innovative solutions are a component of the ‘Grand Bargain’, a global-level agreement that aims at increasing the total amount of funding available for humanitarian crises by increasing the proportion of direct multi-year funding of local and national actors (Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2020). An example of these funding modalities is the ‘pay-for-performance’ approach where service providers are funded directly and are required to achieve certain targets to ensure subsequent renewal of funding. This approach is especially relevant in protracted refugee settings as it optimizes the value of health services in addition to improving their quality, efficiency and effectiveness (Spiegel et al., 2018). This would also translate into better efficiency in management of funds and thus allocation of funds to needed NCD services.

These innovations in financing models need to be coupled with increased advocacy for funding and prioritization of NCD care for refugees. Lessons can be drawn from HIV programs in resource-limited settings on successful advocacy efforts that led to aid funds targeted at health services for refugees, namely the Global Fund for AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and the US President's Emergency Fund for AIDS Relief (Rabkin et al., 2018).

Our study also revealed that the guidelines for NCD management exist in both settings yet their content, dissemination among health providers and implementation remain questionable, thus affecting the quality of care provided. These findings are not surprising as current humanitarian response standards tackle the issue of NCDs, but not to the level of detail needed, especially when compared with the detailed guidelines available for communicable diseases (Jobanputra et al., 2016; Demaio et al., 2013). And as reported by Perone et al., when national guidelines for NCD management exist, they have to be followed; otherwise guidelines validated from the World Health Organization, Sphere and humanitarian organizations such as Medecins Sans Frontieres could be considered (Perone et al., 2017), as evidence-based clinical guidance on the management and follow-up of diabetes in humanitarian settings is not available (Kehlenbrink et al., 2019).

As such, intervention packages for NCDs remain under-defined and tested implementation models are lacking (Perone et al., 2017), causing tremendous challenges for effective provision of NCD care by humanitarian actors in protracted emergency settings with increasing burdens of NCDs.

In fact, the emerging protracted nature of crises explains the scarcity of evidence on the effectiveness of interventions for NCDs in humanitarian crises (Blanchet et al., 2017; Ruby et al., 2015) and confirms the need for more research on successful implementation models for NCD care in humanitarian settings, which in turn can increase the level of accountability of humanitarian actors responding to these emergencies (Jobanputra et al., 2016; Jaung et al., 2021). Several models for NCD care have been piloted whether in Jordan, Lebanon or other contexts such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Saleh et al., 2018; Murphy et al., 2017; Kayali et al., 2019). In Lebanon, the E-Sahha project used, in one of its segments, low-cost e-health tools for diabetes and hypertension detection and referrals in rural settings and refugee settlements. Results from this community participatory-based research project showed the effectiveness of using this e-health model in the identification and appropriate referral of new NCD cases (Saleh et al., 2018). Another model of care tested by Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) which adopted a multidisciplinary approach including case management of diabetes and hypertension, patient support and education counselling, integrated mental health and health promotion, also led to improved quality of care provided to Syrian refugees in a Palestinian refugee camp (Kayali et al., 2019). MSF piloted a similar model of care in a conflict-affected zone in DRC through its Integrated Diabetic Clinic within an Outpatient Department model. This new nurse-led, multi-disciplinary intervention for diabetes was based on a set of context-adapted clinical guidelines and Standard Operating Procedures, coupled with patient counselling and support materials, in addition to specialist training for staff (Murphy et al., 2017). Key factors to be considered when planning NCD interventions in complex humanitarian emergencies included decentralization of treatment provision, reduced appointment frequency and increased focus on patient education (Murphy et al., 2017). In order to deliver good quality hypertension and diabetes care in humanitarian settings, future models of care should adopt a “health system strengthening approach, use patient-centered design, and should be co-created with patients and providers” (Ansbro et al., 2022). The design of these models would be facilitated if more comprehensive WHO clinical and operational guidance were put in place (Ansbro et al., 2022).

4.1. Strengths/limitations

This study interviewed a large number of stakeholders, representing diversity from both countries, ranging from decision makers to healthcare providers, at governmental, NGO and UN levels. Including stakeholders from various decision making and implementation levels led to the triangulation and enrichment of the findings, and the filling of important gaps in the narrative. Inputs from regional and international stakeholders provided further insight and depth to the analysis of the situation and allowed for interpretation of the situation from a global perspective. Additionally, a stakeholder consultation meeting facilitated the validation and strengthening of findings.

The study is limited by its sole focus on health systems actors, rather than the perceptions of Syrian refugees themselves. It is likely that refugees’ perceptions regarding their own access to NCD care will help examine the situation from a new angle. Future research should include these perspectives, which have been briefly explored in Jordan (Al-Rousan et al., 2018). Although saturation was reached and attempts were made to diversify the stakeholders included, it is possible that certain perspectives were not represented.

5. Conclusion and recommendations

The Jordanian and Lebanese governments were moderately successful in their attempts to provide health services to the huge influx of Syrian refugees through their existing national health systems. However, the coverage and quality of care remain suboptimal and continuity is often interrupted due to lack of funding, inadequate dissemination and implementation of national NCD guidelines, refugees’ difficulty navigating health systems, major government policy changes and UNHCR policy changes in cost sharing, eligibility, and vulnerability criteria. The latter are related to the lack of prioritization of and financing for NCDs at the global level.

Considering the fact that Syrian refugees remain in both countries, and that health systems have been overburdened by the COVID-19 pandemic in both Lebanon and Jordan, and the economic crisis in Lebanon and exodus of Lebanese healthcare personnel, the challenges posed here have been exacerbated and call for even urgent and innovative action.

Research from Lebanon confirms the presence of an informal network of healthcare provision among Syrian refugees; and recommends their inclusion in the formal health care system to decrease patient load on primary healthcare centres and other healthcare workers in the overcrowded and understaffed areas (Honein-AbouHaidar et al., 2019).

Effective provision of NCD care in protracted emergency settings with increasing burdens of NCDs requires evidence-based guidelines and effective implementation models for continued NCD care. Innovative financing solutions need to be envisioned along with increased advocacy for funding and prioritization of NCD care for refugees in light of the need to strengthen the “humanitarian-development nexus” and ensure continuity of care for NCDs. Strengthening existing national health systems and striving for equity in achieving universal health coverage for both nationals of host countries and refugees would improve health outcomes. Within such systems, ensuring early access to high quality preventive and curative services as well as continuity of care can only be achieved if all the components of the high quality health system framework are in place (Kruk et al., 2018).

Funding

This work was funded by an internal grant from the Columbia University Global Policy Initiative, Grant number 70499 (Responding to Changing Health Needs in Complex Emergencies: A Policy Imperative).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Ola Sherif with her assistance in conducting the interviews in Jordan, as well as all attendees of the expert meeting.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jmh.2022.100136.

Contributor Information

Chaza Akik, Email: ca36@aub.edu.lb.

Miriam Rabkin, Email: mr84@cumc.columbia.edu.

Wafaa El Sadr, Email: wme1@cumc.columbia.edu.

Fouad M. Fouad, Email: mm157@aub.edu.lb.

Hala Ghattas, Email: hg15@aub.edu.lb.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Abubakar I., Zumla A. Universal health coverage for refugees and migrants in the twenty-first century. BMC Med. 2018;16(216) doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1208-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akik C., Ghattas H., Mesmar S., Rabkin M., Sadr W.M.E., Fouad F.M. Host country responses to non-communicable diseases amongst Syrian refugees: a review. Confl. Health. 2019;13 doi: 10.1186/s13031-019-0192-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Oraibi A., Hassan O., Chattopadhyay K., Nellums L.B. The prevalence of non-communicable diseases among Syrian refugees in Syria’s neighbouring host countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health. 2022;205:139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2022.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Oraibi A., Nellums L.B., Chattopadhyay K. COVID-19, conflict, and non-communicable diseases among refugees. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;34 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alawa J., Hamade O., Alayleh A., Fayad L., Khoshnood K. Cancer awareness and barriers to medical treatment among Syrian refugees and Lebanese citizens in Lebanon. J. Cancer Educ. 2019;35:709–717. doi: 10.1007/s13187-019-01516-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alawa J., Zarei P., Khoshnood K. Evaluating the provision of health services and barriers to treatment for chronic diseases among Syrian refugees in Turkey: a review of literature and stakeholder interviews. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019;16:2660. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16152660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amnesty International 2014. Agonizing choices: Syrian refugees in need of healthcare in Lebanon. Available: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/mde18/001/2014/en/.

- Al-Rousan T., Schwabkey Z., Jirmanus L., Nelson B. Health needs and priorities of Syrian refugees in camps and urban settings in Jordan: perspectives of refugees and health care providers. EMHJ. 2018;24 doi: 10.26719/2018.24.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansbro É., Issa R., Willis R., Blanchet K., Perel P., Roberts B. Chronic NCD care in crises: a qualitative study of global experts’ perspectives on models of care for hypertension and diabetes in humanitarian settings. J. Migr. Health. 2022;5 doi: 10.1016/j.jmh.2022.100094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ay M., Arcos González P., Castro Delgado R. The perceived barriers of access to health care among a group of non-camp Syrian refugees in Jordan. Int. J. Health Serv. 2016;46:566–589. doi: 10.1177/0020731416636831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amnesty International. 2016. Living on the margins. Syrian refugees in Jordan struggle to access health care. Available: https://www.amnestyusa.org/files/living_on_the_margins_-_syrian_refugees_struggle_to_access_health_care_in_jordan.pdf.

- Blanchet K., Ramesh A., Frison S., Warren E., Hossain M., Smith J., Knight A., Post N., Lewis C., Woodward A. Evidence on public health interventions in humanitarian crises. Lancet. 2017;390:2287–2296. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30768-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demaio A., Jamieson J., Horn R., de Courten M., Tellier S. Non-communicable diseases in emergencies: a call to action. PLoS Curr. 2013;5 doi: 10.1371/currents.dis.53e08b951d59ff913ab8b9bb51c4d0de. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Arab R., Sagbakken M. Healthcare services for Syrian refugees in Jordan: a systematic review. Eur. J. Public Health. 2018;28:1079–1087. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cky103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garry S., Checchi F., Cislaghi B. What influenced provision of non-communicable disease healthcare in the Syrian conflict, from policy to implementation? A qualitative study. Confl. Health. 2018;12 doi: 10.1186/s13031-018-0178-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honein-AbouHaidar G., Noubani A., El Arnaout N., Ismail S., Nimer H., Menassa M., Coutts A.P., Rayes D., Jomaa L., Saleh S., Fouad F.M. Informal healthcare provision in Lebanon: an adaptive mechanism among displaced Syrian health professionals in a protracted crisis. Confl. Health. 2019;13 doi: 10.1186/s13031-019-0224-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. 2017. Refugee crisis in MENA: Meeting the development challenge. Available: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/refugee-crisis-mena-meeting-development-challenge-enar.

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee. 2020. The grand bargain [Online]. Available: https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/grand-bargain (Accessed 21 May 2020).

- Jaung M.S., Willis R., Sharma P., Aebischer Perone S., Frederiksen S., Truppa C., Roberts B., Perel P., Blanchet K., Ansbro É. Models of care for patients with hypertension and diabetes in humanitarian crises: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2021;36:509–532. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czab007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobanputra K., Boulle P., Roberts B., Perel P. Three steps to improve management of non-communicable diseases in humanitarian crises. PLoS Med. 2016;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayali M., Moussally K., Lakis C., Abrash M.A., Sawan C., Reid A., Edwards J. Treating Syrian refugees with diabetes and hypertension in Shatila refugee camp, Lebanon: médecins Sans Frontières model of care and treatment outcomes. Confl. Health. 2019;13:12. doi: 10.1186/s13031-019-0191-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehlenbrink S., Smith J., Ansbro É., Fuhr D.C., Cheung A., Ratnayake R., Boulle P., Jobanputra K., Perel P., Roberts B. The burden of diabetes and use of diabetes care in humanitarian crises in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Diab. Endocrinol. 2019;7:638–647. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruk M.E., Gage A.D., Arsenault C., Jordan K., Leslie H.H., Roder-DeWan S., Adeyi O., Barker P., Daelmans B., Doubova S.V. High-quality health systems in the sustainable development goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob. Health. 2018;6:e1196–e1252. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30386-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNatt Z.Z., Freels P.E., Chandler H., Fawad M., Qarmout S., Al-Oraibi A.S., Boothby N. What’s happening in Syria even affects the rocks”: a qualitative study of the Syrian refugee experience accessing noncommunicable disease services in Jordan. Confl. Health. 2019;13 doi: 10.1186/s13031-019-0209-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy A., Biringanine M., Roberts B., Stringer B., Perel P., Jobanputra K. Diabetes care in a complex humanitarian emergency setting: a qualitative evaluation. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017;17:431. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2362-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perone S.A., Martinez E., du Mortier S., Rossi R., Pahud M., Urbaniak V., Chappuis F., Hagon O., Bausch F.J., Beran D. Non-communicable diseases in humanitarian settings: ten essential questions. Confl. Health. 2017;11 doi: 10.1186/s13031-017-0119-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabkin M., Fouad F.M., El-Sadr W.M. Addressing chronic diseases in protracted emergencies: lessons from HIV for a new health imperative. Glob. Public Health. 2018;13:227–233. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2016.1176226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby A., Knight A., Perel P., Blanchet K., Roberts B. The effectiveness of interventions for non-communicable diseases in humanitarian crises: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh S., Alameddine M., Farah A., El Arnaout N., Dimassi H., Muntaner C., El Morr C. eHealth as a facilitator of equitable access to primary healthcare: the case of caring for non-communicable diseases in rural and refugee settings in Lebanon. Int. J. Public Health. 2018;63:577–588. doi: 10.1007/s00038-018-1092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh S., Ibrahim S., Diab J.L., Osman M. Integrating refugees into national health systems amid political and economic constraints in the EMR: approaches from Lebanon and Jordan. J. Glob. Health. 2022;12 doi: 10.7189/jogh.12.03008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel P., Chanis R., Trujillo A. Innovative health financing for refugees. BMC Med. 2018;16 doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1068-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel P.B., Checchi F., Colombo S., Paik E. Health-care needs of people affected by conflict: future trends and changing frameworks. Lancet. 2010;375:341–345. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61873-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong J., Varady C., Chahda N., Doocy S., Burnham G. Health status and health needs of older refugees from Syria in Lebanon. Confl. Health. 2015;9 doi: 10.1186/s13031-014-0029-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR . Standard Operating Procedures; 2018. Guidelines for Referral Health Care in Lebanon. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR 2018b.Jordan vulnerability assessment framework - 2017 population survey report: sector vulnerability review.

- UNHCR 2020. Global trends: forced displacement in 2019.

- UNHCR, UNICEF & WFP 2020. Vulnerability assessment of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon 2020.

- UNHCR Executive Committee of the High Commissioner's Programme 2009. Conclusion on protracted refugee situations No. 109 (LXI).

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2020. Syria regional refugee response [Online]. Available: http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/regional.php (Accessed May 2020).

- World Health Organization 2010. Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies.

- World Health Organization. 2011. Noncommunicable diseases country profiles - Syrian Arab Republic 2010[Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/nmh/countries/2011/syr_en.pdf?ua=1 (Accessed).

- World Health Organization 2013. Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013-2020.

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe 2019. Prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases in refugees and migrants.

- Yadav U.N., Rayamajhee B., Mistry S.K., Parsekar S.S., Mishra S.K. A syndemic perspective on the management of non-communicable diseases amid the COVID-19 pandemic in low-and middle-income countries. Front. Public Health. 2020;8:508. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.