Abstract

Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) among people living with HIV (PLWH) is a significant public health concern. Despite the advent of effective antiretroviral therapy, up to 50% of PLWH still experience worsened neurocognition, which comorbid AUD exacerbates. We report converging lines of neuroimaging and neuropsychological evidence linking comorbid HIV/AUD to dysfunction in brain regions linked to executive function, learning and memory, processing speed, and motor control, and consequently to impairment in daily life. The brain shrinkage, functional network alterations, and brain metabolite disruption seen in individuals with HIV/AUD have been attributed to several interacting pathways: viral proteins and ethanol are directly neurotoxic and exacerbate each other’s neurotoxic effects; ethanol reduces antiretroviral adherence and increases viral replication; AUD and HIV both increase gut microbial translocation, promoting systemic inflammation and HIV transport into the brain by immune cells; and HIV may compound alcohol’s damaging effects on the liver, further increasing inflammation. We additionally review the neurocognitive effects of aging, Hepatitis C coinfection, obesity and cardiovascular disease, tobacco use, and nutritional deficiencies, all of which have been shown to compound cognitive changes in HIV, AUD, and in their comorbidity. Finally, we examine emerging questions in HIV/AUD research, including genetic and cognitive protective factors, the role of binge drinking in HIV/AUD-linked cognitive decline, and whether neurocognitive and brain functions normalize after drinking cessation.

Keywords: HIV, cognition, neuroimaging, inflammation, brain, alcohol

Introduction

While HIV-related mortality has fallen with the advent of antiretroviral therapy (ART), morbidity remains high and research interest has turned to the cognitive sequelae of HIV infection. Although ART improves cognitive performance (Cohen et al., 2001), up to 50% of people living with HIV (PLWH) still experience neurocognitive deficit (Heaton et al., 2010). The continued prevalence of neurocognitive changes even in virally-suppressed individuals has spurred interest in common comorbidities, such as alcohol use, as contributors to cognitive decline among PLWH.

Alcohol use among PLWH is a significant public health concern. Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) among PLWH is estimated to be 2–4 times higher than among the general population (Duko et al., 2019; Galvan et al., 2002; Petry, 1999; Vagenas et al., 2015). AUD in PLWH adversely affects brain structural, functional, and metabolic functions, as well as cognition (Cohen et al., 2019; Gullett et al., 2018; Meyerhoff, 2001; Míguez-Burbano et al., 2014) and therefore may be a major contributor to cognitive deficit among PLWH.

In recent years, research interest has therefore turned to pathophysiological mechanisms by which AUD may exacerbate HIV-associated neurological damage (Norman & Basso, 2015). In this review, neuroimaging and neuropsychological literature on HIV/AUD comorbidity is synthesized with evidence describing gut microbial translocation, hepatic injury, and increased systemic inflammation as potential mechanisms of damage. Pro-inflammatory and hepatotoxic comorbidities common in the HIV/AUD population, such as cardiovascular disease, hepatitis C infection, and non-alcohol substance use, further contribute to brain injury.

Neuroimaging

Neuroimaging has become increasingly vital in identifying biomarkers of HIV- and AUD-linked brain pathology. Macro- and microstructural gray and white matter damage, alterations in metabolite concentrations, and disruption of functional activation networks have been linked to cognitive changes in HIV (reviewed in Masters & Ances, 2014) and AUD (reviewed in Bühler & Mann, 2011).

Structural

HIV infection is linked to macro- and microstructural brain dysmorphology. Gray and white matter atrophy consistent with widespread neuronal death has been observed repeatedly in PLWH (Hua et al., 2013; Nir et al., 2019). Although a recent meta-analysis observed reduced dysmorphology in cohorts with access to ART, suggesting that viral suppression by ART partially preserves brain structure (particularly gross white matter volume), reduced brain volume nonetheless remains prevalent among PLWH (O’Connor et al., 2018).

Independently, AUD has been linked to brain volume loss, particularly of white matter and particularly in the corpus callosum. Gray matter volume loss in AUD is relatively selective, affecting notably the frontal cortex, the hippocampus, the insula, the thalamus, the reward system (including the basal ganglia, caudate, amygdala, and putamen), and the cerebellum (reviewed in Yang et al., 2016). However, substantial individual variation in tissue loss raises the possibility that comorbidities of AUD, such as thiamine deficiency or liver damage, may contribute to or mediate volume loss in this population (reviewed in Dupuy & Chanraud, 2016; Zahr & Pfefferbaum, 2017).

Though it has been recognized for almost two decades that magnetic resonance imaging is effective to identify interactive effects of HIV and AUD on brain macro- and microstructure (Meyerhoff, 2001; Pfefferbaum et al., 2002), the bulk of research in these areas continues to treat the two conditions separately. In recent years, however, evidence has begun to emerge that HIV/AUD represents a distinct brain imaging phenotype. Multivariate machine learning analysis identified 25 regional volume, cortical surface area or thickness, and sulcus curvature indices as predictive of HIV/AUD comorbidity, of which 7 overlapped with HIV or AUD alone (Adeli et al., 2019). Other studies, however, have found volume abnormalities in HIV/AUD only in brain regions also impacted by AUD alone (Pfefferbaum et al., 2012). Notably, AUD increases the deleterious effect of advanced HIV pathophysiology on ventricular and callosal morphology, such that individuals meeting criteria for AIDS show disproportionately exacerbated tissue loss when AUD is also present (Pfefferbaum et al., 2006; Pfefferbaum et al., 2012). However, within the population of PLWH consuming 100+ drinks per month, increasing alcohol intake does not increase tissue loss in the absence of other comorbidities (Durazzo et al., 2007). Further investigations powered to disentangle the consequences of HIV, alcohol, and comorbidities would help to clarify the contribution of alcohol intake to tissue loss.

The macrostructural dysmorphology observed in HIV/AUD has cognitive consequences: in one study, reduced thalamic, cerebellar, and hippocampal volumes in this population were associated with poorer memory (Fama et al., 2014). However, much of the existing data in this area have been derived from a small number of cohorts studied longitudinally, and thus may not capture the full spectrum of individual variation in HIV/AUD comorbidity. Any alcohol use in particularly vulnerable populations, such as youth with HIV, may be linked to reduced overall gray matter volume and to impaired working memory, processing speed, and overall cognition (Lewis-de Los Angeles, 2017); here a dose effect has not been determined.

Although white matter macrostructural damage is less prevalent in the ART era (O’Connor et al., 2018), microstructural white matter pathology remains a substantial concern. Indices of water diffusion, believed to inversely correlate with myelin and fiber integrity, and white matter hyperintensities have been used as clinically relevant markers of white matter damage. White matter tracts are disrupted throughout the brains of PLWH compared to seronegative controls (Seider et al., 2016). While increased diffusivity in posterior regions of the frontal lobe, temporal lobe, and parietal lobe is observed in neurocognitively asymptomatic PLWH, cognitively-impaired PLWH show greater diffusivity in these regions as well as damage to prefrontal white matter tracts, such that white matter integrity metrics identify cognitively-impaired PLWH with >80% accuracy. In particular, worse processing speed and verbal fluency correlate with reduced white matter integrity (Zhu et al., 2013).

The pattern of regional white matter compromise in cognitively-impaired PLWH partially overlaps with that seen in seronegative individuals with AUD. In brief, AUD consistently damages white matter pathways associated with visuospatial and language processing, decision-making, sensory integration, and interhemispheric communication (reviewed in Dupuy & Chanraud, 2016), and greater AUD severity (assessed using the Alcohol Dependence Scale) correlates with greater damage (Monnig et al., 2015).

HIV and AUD comorbidity synergistically compromise white matter microstructure. Reduced callosal white matter integrity predicts decreased fine motor performance, increased ataxia, and worsened cognitive outcomes in HIV/AUD; additionally, lower CD4+ count and/or AIDS diagnosis are significantly related to cognitive performance and white matter damage only when AUD is also present (Pfefferbaum et al., 2007; Schulte et al., 2008). Disruptions in white matter integrity in HIV/AUD relate to cognitive performance on an emotion processing task, further suggesting that white matter damage is linked to poorer cognition in this population (Schulte et al., 2012). Recent findings indicate that HIV/AUD compromises white matter tracts even in asymptomatic individuals screened for comorbidities, indicating that alcohol use itself underlies white matter degeneration (Gullett et al., 2018).

Overall, consistent with gross structural findings, AUD potentially moderates the effects of HIV disease progression on white matter integrity and associated cognitive and motor performance indices, such that CD4+ count is particularly predictive of white matter integrity when AUD is also present. However, existing studies do not indicate a causal relationship, and one study shows that longer duration of infection is associated with greater white matter injury throughout the brain in a population of PLWH without AUD (Zhu et al., 2013). Thus it is unclear whether comorbid AUD genuinely increases the extent of white matter injury or merely accelerates the rate at which it occurs. Further research is required to isolate the contribution of AUD to white matter injury.

Functional Neuroimaging

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which uses differential blood oxygen consumption across brain regions to track regional activity, is frequently used to assess brain function in PLWH (e.g., Plessis et al., 2014). Functional connectivity, or the signal correlation over time between two or more brain regions, is used to probe the organization of neural networks: altered functional connectivity in a clinical population suggests alterations in the underlying network (Fox & Greicius, 2010).

In general, PLWH exhibit reduced neural efficiency and functional reorganization: task-related brain regions (particularly in the fronto-striatal network) are hyperactivated and adjacent brain regions not activated in seronegative controls are recruited (reviewed in Hakkers et al., 2017). These alterations are indicative of degeneration in task-related circuits, such that additional cognitive resources and associated brain regions and networks unused by healthy controls are activated to maintain performance. Dynamic range of activation, or relative activation increase with growing task complexity, has been proposed as a measure of lost brain reserve in HIV and other conditions compromising functional networks (Tomasi et al., 2006). During easy tasks, PLWH compensate for neuronal damage by tapping additional brain regions and hyperactivating task-related regions; however, during more complex tasks, PLWH are unable to correspondingly increase activation to maintain performance and even show reduced activation relative to seronegative controls (Caldwell et al., 2014). Reduced dynamic range in frontal regions associated with working memory performance predicts worsened attention in PLWH (Cohen et al., 2018). Additionally, PLWH show attenuated functional connectivity at rest, consistent with frontostriatal network compromise (Ipser et al., 2015).

Functional reorganization and decreased efficiency have also been reported in the context of AUD. Individuals with AUD show disruptions consistent with functional reorganization in frontocerebellar, frontolimbic, and frontostriatal circuits, such that regions unused by healthy controls are recruited to maintain task performance (reviewed in Zahr et.al, 2017). Conversely, decreased within-network connectivity and expanded outside-network connectivity correlate with deficits in processing speed and working memory in individuals with AUD (Müller-Oehring et al., 2015), consistent with inefficient processing and network dedifferentiation in low-performing individuals.

Despite evidence that HIV and AUD independently disrupt frontostriatal networks linked to attention, executive functioning, and memory, few studies have investigated functional neuroimaging markers of cognitive changes in the HIV/AUD population. One study reported that lifetime alcohol abuse was not predictive of functional connectivity between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and caudate in PLWH (Ipser et al., 2015). However, additional research on functional imaging correlates of cognition in this population is needed.

Cerebral Metabolite Markers

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) noninvasively quantifies the concentration of metabolites within brain tissue in vivo. MRS has been extensively used to identify inflammation and markers of neuronal damage in HIV-related neuropathology (Paul et al., 2008; Heaps et al., 2011; Harezlak et al., 2011, 2014). Choline-containing compounds (Cho), which have been interpreted as a marker of glial cell proliferation, and the putative astrocyte marker myoinositol (MI) are elevated in untreated HIV (Meyerhoff et al., 1999; Chang et al., 2003; Chang et al., 2004); Cho and MI increases attenuate, but are not fully reversed, after ART initiation (Young et al., 2014). N-acetyl-aspartate (NAA), putatively a marker of neuron health, is depressed in frontal and subcortical regions in PLWH (Paul et al., 2007; Gongvatana et al., 2013). Elevated Cho and MI and low NAA are associated with reduced cognitive and motor performance (Meyerhoff et al., 1999; Paul et al., 2007; Mohamed et al., 2010), increased systemic inflammation (Letendre et al., 2011), decreased working memory network efficiency (Ernst et al., 2003), and macrostructural changes including volume loss (Cohen et al., 2010; Hua et al., 2013).

Cerebral metabolite concentrations are also disrupted in AUD, particularly in the frontal lobes and cerebellum. As in PLWH, AUD appears to depress frontal NAA concentrations, consistent with neuronal injury in a region susceptible to neuronal loss (reviewed in Meyerhoff et al., 2013). Low NAA correlates with worse fine and gross motor performance, verbal learning, executive function, attention, and visuospatial performance in AUD (Bendszus et al., 2001; Parks et al., 2002; Durazzo et al., 2006; Xia et al., 2012; Morley et al., 2020). Conversely, unlike in HIV, AUD is often associated with low Cho, potentially due to lower glial activity (reviewed in Meyerhoff, 2014) or non-brain pathology such as thiamine deficiency or liver cirrhosis (Zahr et al., 2009). Low Cho correlates with visuospatial learning and gross motor deficits (Parks et al., 2002; Durazzo et al., 2006) in this population.

Few studies have examined the effect of HIV/AUD comorbidity on cerebral metabolites. One study prior to the advent of ART identified cumulative, but not interactive, negative effects of HIV and current AUD on white matter concentrations of phospholipids and of phosphorus metabolites linked to cellular metabolism (Meyerhoff et al., 1995); this effect was not fully remedied by abstinence. Phosphorus metabolite concentration was not correlated with cognition, although the majority of participants showed no or mild global cognitive impairment and a relationship may have emerged in a more-impaired sample. In more recent studies including PLWH taking ART, individuals with lifetime AUD showed NAA and creatine-containing metabolite deficits in the parietal-occipital cortex (Pfefferbaum et al., 2005) and elevated Cho and MI in the striatum (Zahr et al., 2014). Singly-diagnosed (HIV or AUD) individuals did not differ from healthy controls; nor was use of ART in PLWH associated with metabolite levels. Because low Cho and MI are common findings in AUD, further research is required to elucidate why HIV/AUD is associated with greater Cho and MI elevations than is HIV alone.

Some of the inconsistency in metabolite profiles in AUD may be explained by variations in the recency of last alcohol use, usually ranging from 1 week to 1 month prior to examination (reviewed in Meyerhoff et al., 2013). Metabolite concentrations normalize after prolonged abstinence in some but not all seronegative individuals with lifetime AUD (Zahr et.al, 2009); individuals assessed during short-term abstinence may potentially exhibit a metabolite profile distinct from that seen in AUD or in long-term abstinence. However, Pfefferbaum et al. (2005) report no metabolite difference in individuals living with HIV/AUD after short (1–14 days) and long (7–43 months) periods of abstinence, suggesting that in HIV/AUD populations metabolites may not normalize with prolonged abstinence. As a caveat, Pfefferbaum et al. sampled only 4 long-term abstainers with HIV/lifetime AUD and may therefore have been underpowered to detect changes in long-term abstinence.

Neurocognition

HIV-related neurocognitive disorders remain prevalent among PLWH. Although viral load and immune system function correlate with cognitive deficit and ART has consequently reduced the prevalence of frank HIV-associated dementia, even virally-suppressed PLWH experience subtle cognitive alterations (Simioni et al., 2010). Furthermore, even neurocognitive deficit without functional impairment confers increased risk of self-reported and performance-based functional impairment at follow-up, relative to neurocognitively normal PLWH (Grant et al., 2014); thus subtle cognitive deficit may presage more serious impairment, even in virally-suppressed PLWH.

Independently, chronic alcohol use degrades executive function, working memory, visuospatial processing, short- and long-term memory, and motor function, although the population with AUD is cognitively heterogeneous and some individuals are relatively spared (reviewed in Bates et al., 2002). Inter-individual variability in cognitive trajectories in AUD indicates that cognitive decline may be moderated by variables such as age, quantity of alcohol consumed, comorbid medical and psychiatric complications, and length of time meeting AUD criteria (reviewed in Oscar-Berman et al., 2014).

Research on cognition in HIV/AUD is complicated by methodological heterogeneity: no neuropsychological battery is standard in the HIV/AUD population, and many studies examine only one or two domains of cognition or collapse all domains into a global deficit metric. Additionally, as in singly-diagnosed AUD, cognitive deficit is likely moderated by age, comorbid medical complications, other substance use, and history of abstinence, which may vary between cohorts (Cohen et al., 2019). However, a cognitive profile has emerged from the extant literature.

Executive Function-Attention

Executive function refers to processes involved in self-regulation and goal-oriented behavior. HIV and AUD can impact frontocerebellar and frontostriatal pathways implicated in executive function (Plessis et al., 2014; Courtney et al., 2013; Chanraud et al., 2010); correspondingly, reduced executive function is common in both populations (Heaton et al., 2011; Oscar-Berman & Marinković, 2007) and is often exacerbated in HIV/AUD comorbidity (Rothlind et al., 2005; Fama et al., 2016). Closely linked to executive function are working memory and attention, and both working memory and attention are interactively compromised in HIV/AUD (Schulte et al., 2005; Sassoon et al., 2007; Douglas-Newman et al., 2017).

Learning - Memory

Verbal and visuospatial learning and recall are worsened in PLWH (Gongvatana et al., 2007; Woods et al., 2013); recall is particularly vulnerable in older adults (Seider et al., 2014). Independently of age and HIV, AUD substantially impairs episodic memory encoding and retrieval across verbal and visuospatial domains, as well as novel semantic encoding and procedural learning (reviewed in Pitel et al., 2014).

Several forms of memory are worsened in HIV/AUD, above and beyond the effects of either condition alone. Deficits have been reported in immediate and delayed recall (Fama et al., 2009, 2014; Monnig et al., 2016; Cohen et al., 2019; contrast Attonito et al., 2014), procedural learning (Fama et al., 2014), semantic memory (Fama et al., 2011; Gongvatana et al., 2014), and visual learning (Douglas-Newman et al., 2017).

Processing Speed

The deleterious effects of HIV on cognitive processing speed have been recognized for some years (Paul et al., 2002), particularly when pro-inflammatory comorbidities such as microbial translocation or tobacco use are present (Monnig et al., 2017; Okafor et al., 2019). Independently, AUD slows cognitive processing, particularly when comorbid with thiamine deficiency (Pitel et al., 2011).

Cognitive processing speed is impaired in HIV/AUD comorbidity, such that individuals with comorbid HIV/AUD show slower processing than individuals with HIV alone (Fama et al., 2009; Sassoon et al., 2017). Older age during prior AUD exacerbates processing speed deficiencies (Gongvatana et al., 2014), which in turn predict greater cognitive difficulties and reduced everyday functioning in PLWH with prior AUD (Paolillo et al., 2019). Greater total quantity of alcohol consumed during period of heaviest consumption also decreases processing speed (Cohen et al., 2019).

Psychomotor/Motor Functioning

Psychomotor speed, fine motor dexterity, and gross motor deficits are frequently observed in AUD, likely arising from compromised frontocerebellar and callosal white matter networks (e.g., Rosenbloom et al., 2008). PLWH also show deficits in coordinating fine motor responses (Do et al., 2018), potentially due to frontostriatal compromise (Sullivan et al., 2011).

Manual reaction time is deficient in HIV/AUD: Durvasula et al (2006) find an interaction between HIV/current AUD, while Green et al (2004) find cumulative (but not interactive) deleterious effects of HIV and lifetime AUD (Green et al., 2004). HIV and AUD also have interactive effects on motor and visuomotor speed (Rothlind et al., 2005; Durvasula et al., 2006), such that HIV is linked to poor performance only in heavier drinkers. HIV/AUD-linked fine motor deficit correlates with dysfunction in white matter tracts and frontostriatal circuits impacted by HIV (Pfefferbaum et al., 2007; Fama et al., 2007), but in a study comparing HIV/AUD to singly-diagnosed groups, HIV serostatus did not affect performance on an ataxia measure tied to primarily alcohol-driven frontocerebellar dysfunction (Fama et al., 2007).

Functional Consequences

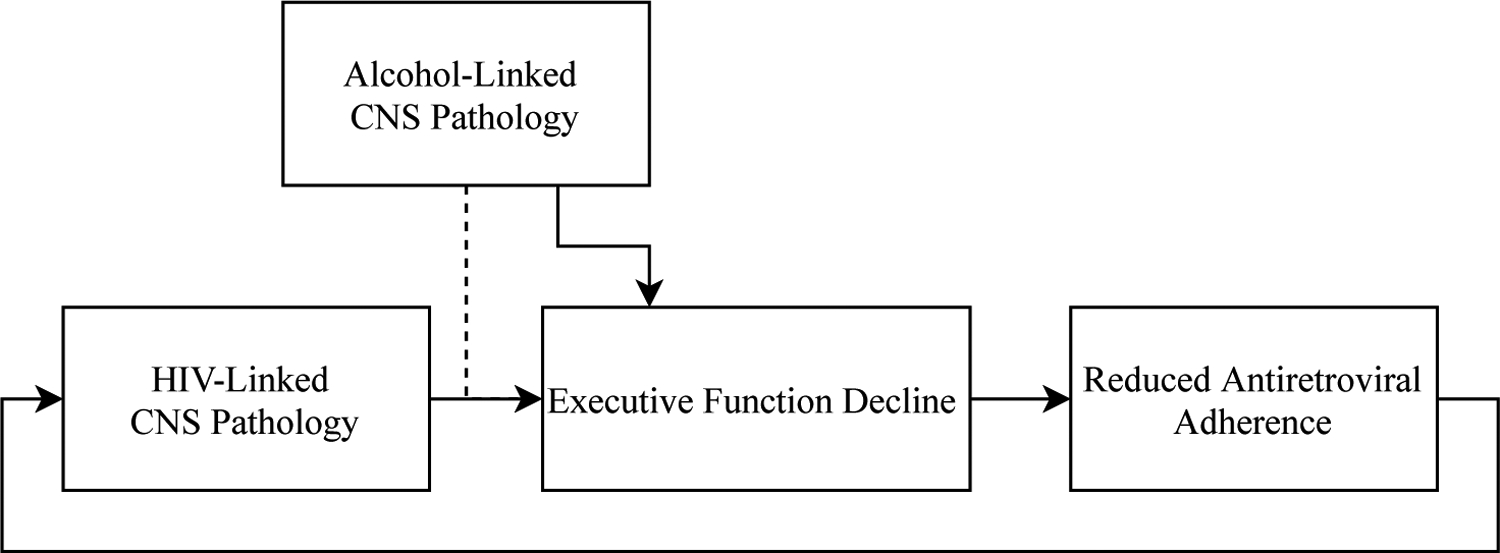

Cognitive changes in HIV/AUD have substantial functional consequences. Worse executive function among PLWH is linked to reduced self-reported quality-of-life (Osowiecki et al., 2000). Individuals with comorbid HIV/AUD report worse health-related quality-of-life relative to single-diagnosis groups, to which general cognitive status contributes variance (Rosenbloom et al., 2007). Impaired executive function predicts ART adherence in this population (Rothlind et al., 2005); because ART adherence reciprocally predicts cognitive function in PLWH (Ettenhofer et al., 2010), AUD-linked executive function deficits may exacerbate disease progression and consequently damage cognition (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Executive function and medication adherence. Executive function predicts medication adherence, which in turn predicts central nervous system pathology. The dotted line indicates a possible relationship between HIV- and alcohol-linked cognitive decline.

Potential Mechanisms

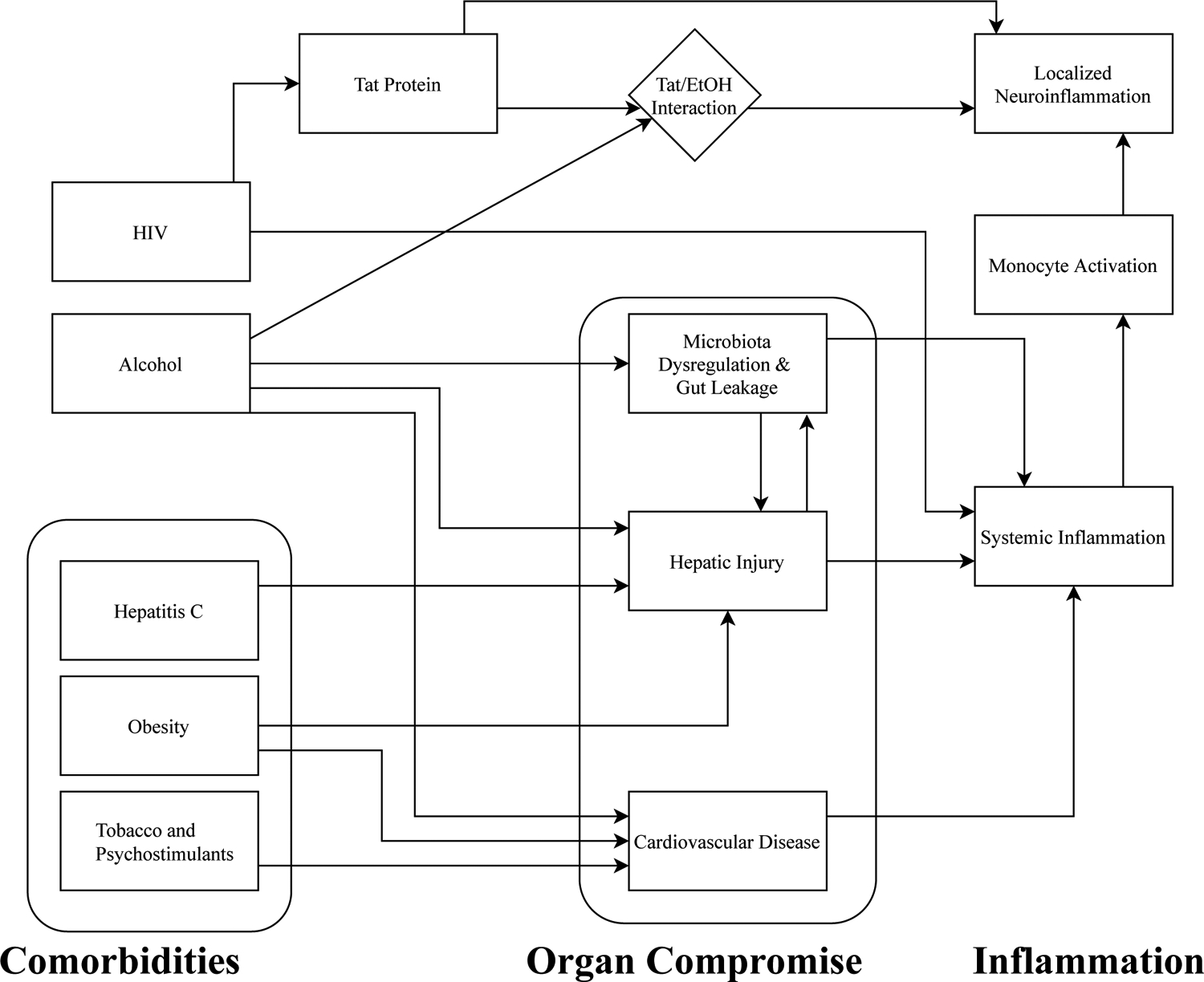

Direct neurotoxicity, systemic inflammation, increased viral burden, gut microbial translocation, and liver dysfunction have all been proposed as mechanisms by which HIV and AUD together may deleteriously impact brain health and cognitive function. Critically, these mechanisms seem to interact, such that increased systemic immune activation contributes to liver dysfunction, which in turn reinforces inflammation; consequently, dysfunction along any axis compounds dysfunction on other axes, contributing ultimately to extensive systemic damage (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

An overview of pathophysiology in HIV/AUD. HIV and heavy alcohol use independently contribute to systemic inflammation, which is exacerbated by organ compromise and by comorbidities prevalent in the HIV/AUD population. Systemic inflammation increases HIV transport through the blood-brain barrier via activated monocytes, thereby triggering localized neuroinflammation. Additionally, HIV Tat protein augments pro-inflammatory cytokine release in the central nervous system, particularly in the presence of ethanol.

Tat Protein

Neurons are rarely, if ever, directly infected by HIV (González-Scarano & Martin-Garcia, 2005; Kaul et al., 2005; Lindl et al., 2010; McArthur et al., 2003). Rather, HIV-infected monocytes cross the blood-brain barrier and differentiate into macrophages in the central nervous system (CNS) (Albright et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2000); surrounding perivascular macrophages and microglia are infected through direct contact (González-Scarano & Martin-Garcia, 2005; Lindl et al., 2010). Tat protein produced by infected cells interacts with ethanol, augmenting pro-inflammatory cytokine release, potentiating apoptosis, and impairing cognition in rodent models (reviewed in Maubert et al., 2016). Tat also potentiates the rewarding effects of ethanol in murine models (McLaughlin et al., 2014), potentially increasing alcohol consumption, although this mechanism has not been explored in humans.

Inflammation

Systemic inflammation and localized neuroinflammation typify HIV infection, even in virally-suppressed individuals (Anthony et al., 2005). HIV-infected microglia and perivascular macrophages trigger cytokine and chemokine overexpression, inducing persistent neuroinflammation (Merrill & Chen, 1991); in turn, neuroinflammation contributes to poorer verbal memory, executive function, motor function, working memory, and visual construction even in virally-suppressed PLWH (Rubin et al., 2018). Consumption of >4 drinks per day for men or >3 for women is independently associated with monocyte activation and systemic inflammation in PLWH (So-Armah et al., 2019). Gut permeability, microbial translocation, and hepatic damage may mediate the alcohol-to-systemic inflammation-to-CNS damage pathway. Furthermore, HIV Tat protein and alcohol synergistically induce localized neuroinflammation when present in murine brain tissue (Flora et al., 2005). Thus, chronic alcohol consumption likely exacerbates the neuroinflammatory effects of HIV.

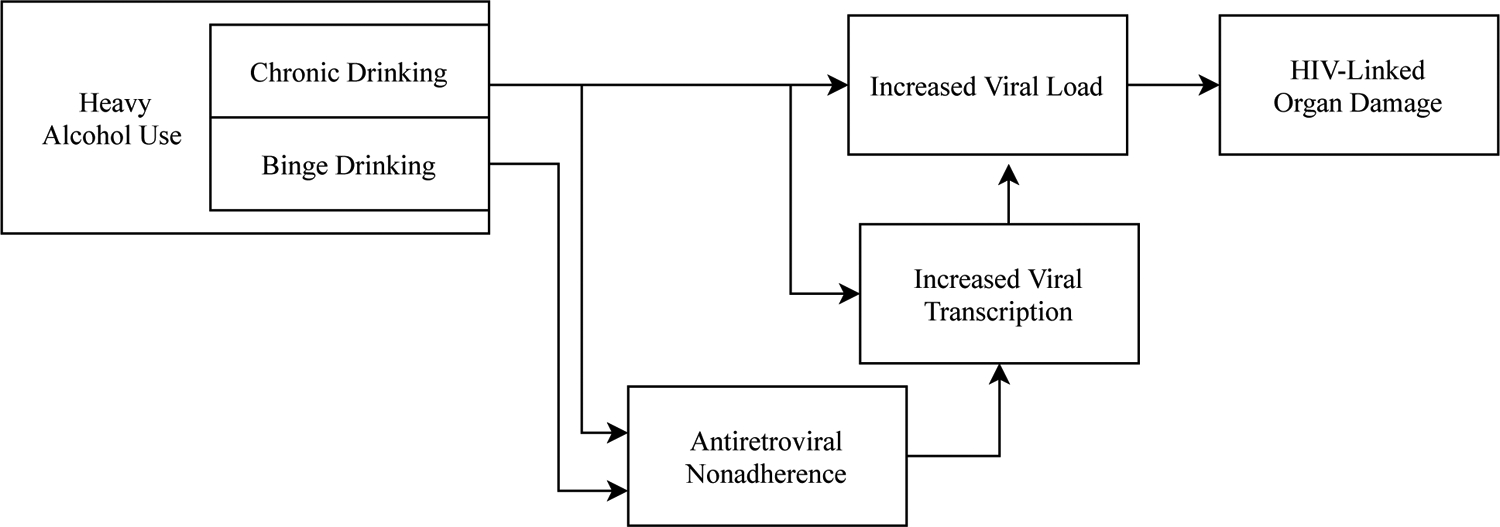

Reduced Viral Suppression

Early and consistent viral suppression minimizes neuropathology in PLWH (Sanford et al., 2018), and ART uptake partially remediates existing cognitive deficits (Cohen et al., 2001). AUD contributes to increased viral burden via two pathways (Figure 3): consumption of greater than 7 drinks per week for women or 14 for men is directly linked to viral burden, controlling for homelessness, demographic factors, and other drug use; a smaller portion of variance in viral load is explained by reductions in ART adherence among chronic heavy drinkers (Cook et al., 2017). However, AUD strongly predicts reduced ART uptake and failure to adhere to ART (Chander et al., 2006; reviewed in Ge et al., 2018). Conversely, drinking reduction in HIV/AUD is associated with increased viral suppression (Cook et al., 2019).

Figure 3.

The relationship between heavy alcohol use and viral load. Chronic heavy alcohol use and binge drinking differentially increase viral load, thereby contributing to HIV-associated pathophysiology.

Viral Transcription From Reservoir

The lengthy half-lives of CNS cells and their isolation from immune cells outside the CNS enables the HIV virus to persist latent within the brain in a viral reservoir. Consequently, the HIV virus remains detectable in the CNS even after falling to undetectable concentrations within the bloodstream. Cognitive performance is linked to extent of viral reservoirs: HIV-1 is detectable within up to 19% of astrocytes and up to 14% of microglia in PLWH with cognitive deficits, but only up to 11% of astrocytes and 9% of microglia in cognitively-intact PLWH (reviewed in Gray et al., 2014).

Because the HIV virus is not eradicated from CNS reservoirs by ART, during periods of ART nonadherence the virus may replicate and spread from reservoirs. Alcohol administration in vitro and in simian models increases viral transcription from reservoirs (Dong et al., 2000; Robichaux et al., 2015), potentially contributing to viral expression, and thus to increased neuropathology (Chang et al., 2002), during nonadherence. Alcohol use is thus associated both with greater nonadherence to ART and with greater viral replication during nonadherence (Figure 3).

Microbial Translocation

Alcohol use compounds chronic immune activation and systemic inflammation in HIV infection (reviewed in Monnig, 2017 and Molina et al., 2018). In brief, alcohol exposure induces intestinal hyperpermeability while shifting the balance of gut microbiota toward Gram-negative bacteria with endotoxic cell walls. In combination, these processes increase translocation of endotoxic gut microbial byproducts into circulation, triggering systemic endotoxemia and consequently inflammation.

Monocyte activation in response to endotoxemia is hypothesized to promote HIV viral transport into the brain (Rao et al., 2014). Microbial translocation is linked to increased risk of HAD (Ancuta et al., 2008); however, as biomarkers of microbial translocation do not fully normalize after ART induction (Marchetti et al., 2013), even virally suppressed PLWH are at risk of inflammation-linked neurocognitive dysfunction (Imp et al., 2017). In recent years, this pathway has been identified as a contributor to neurological dysfunction and its neurocognitive sequelae in HIV/AUD (Royal et al., 2016; Monnig et al., 2019). Biomarkers of microbial translocation and related immune activation predict reductions in processing speed in this population (Monnig et al., 2017).

Liver Dysfunction

Heavy drinking is a major contributor to liver disease; conversely, liver disease exacerbates the adverse effects of alcohol use on the central nervous system. The liver detoxifies gut microbial byproducts and regulates pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines (Wang et al., 2010). In alcoholic liver disease, both functions are impaired, leading to endotoxin buildup and systemic inflammation, which in turn contribute to cirrhosis, superimposed alcoholic hepatitis, and gut microbiota compromise (Bautista, 2001). Alcoholic liver disease and associated systemic inflammation exacerbate the effects of AUD on the frontal and prefrontal cortices, as well as promoting astrocytic swelling and microglial activation (reviewed in Davis & Bajaj, 2018; Bajaj, 2019). As in AUD (but not in HIV alone), Cho and MI are depressed throughout the brain in alcoholic liver disease, the latter possibly in response to astrocytic swelling (reviewed in Zahr & Pfefferbaum et al., 2017). Liver dysfunction may underlie much of the Cho and MI dysregulation reported in many individuals with AUD (Zahr et al., 2009), and consequently the associated cognitive changes.

Liver pathology is also associated with the neural pathology seen in HIV (Solomon et al., 2017). Markers of hepatic fibrosis correlate with reduced executive function and psychomotor speed, as well as global cognitive deficit, in PLWH (Falasca et al., 2017; Ciccarelli et al., 2019), suggesting that liver damage contributes to some aspects of cognitive deficit. However, individuals with decompensated liver disease were excluded from these studies; the effects of frank hepatic disease on cognitive function in PLWH may be even more pronounced. Additionally, liver fibrosis may slow ART clearance, leading to ART overexposure (Barreiro et al., 2007) and consequent increased neurotoxic effects.

Transgenic rat models indicate that HIV facilitates alcohol-related liver damage, likely via increased gut leakage and infiltration of inflammatory cells (Banerjee et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2019). In PLWH, alcohol abuse is associated with hepatotoxicity, potentially via synergistic effects of ART and alcohol on mitochondria and pro-inflammatory cytokines (Barve et al., 2010). The compounded effects of HIV and alcohol on liver function may contribute substantially to the cognitive deficits observed in this population.

Other Comorbidities

Increasing evidence indicates that comorbidities such as Hepatitis C, metabolic and cardiovascular disease, and other substance use compound the direct effects of HIV/AUD pathophysiology on the body and brain. Conversely, organ damage caused by HIV/AUD exacerbates comorbidities such as nutrient deficiency.

Hepatitis C Coinfection

Hepatitis C (HCV) is a frequent comorbidity in both HIV and AUD: while estimates vary, recent findings indicate approximately 20% of PLWH and 16% of individuals with AUD have chronic HCV (Soriano et al., 2010; Novo-Veleiro et al., 2013). HCV is an independent risk factor for neurocognitive deficit, particularly in memory and attention, with deficits observable even before cirrhosis is detectable (Hilsabeck et al., 2002). HCV appears to disrupt cerebral metabolite concentrations: working memory, attention, processing speed, verbal fluency, and global cognitive deficits in HCV infection, as in HIV, are linked to elevated Cho (Forton et al., 2002; Grover et al., 2012) and MI (Forton et al., 2008; Thames et al., 2015). Additionally, HCV is linked to microstructural dysmorphology in multiple white matter tracts, including the corpus callosum (reviewed in Amirsardari et al., 2019); eradication of HCV improves language, learning and memory, executive function, processing speed, and motor performance only when white matter integrity also improves, indicating that white matter damage underlies worsened cognition in HCV (Kuhn et al., 2017). Systemic and cerebral inflammation have been identified as mediators of brain and cognitive deterioration in HCV, as in HIV (Senzolo et al., 2011). Liver damage may separately mediate the HCV-cognition pathway (Hilsabeck et al., 2003).

Coinfection with HCV compounds the inflammatory and hepatic burden of HIV, with concomitant cognitive and psychological consequences. HIV/HCV coinfection is associated with worsened learning and memory, reduced processing speed, motor slowing, and global cognitive deficit relative to HIV monoinfection (e.g., Hinkin et al., 2008; reviewed in Martin-Thormeyer & Paul, 2009). The cognitive effects of coinfection are not explained purely by additive effects of HIV and HCV: in a sample with undetectable HIV viral load, HIV/HCV individuals showed reductions in attention/executive function, fine motor function, and learning and memory, whereas monoinfected individuals performed similarly to controls (e.g., Sun et al., 2013). Cognitive deficit is particularly marked in persons with HIV/HCV coinfection and hepatic injury (Barokar et al., 2019), indicating that liver damage mediates cognitive deficit in this population.

Consistent with HCV’s adverse hepatic and inflammatory effects, HIV/HCV/AUD comorbidity further impacts brain and cognition. HIV/HCV/AUD comorbidity is associated with greater monocyte activation relative to singly- or doubly-diagnosed groups, consistent with increased gut microbial translocation (Monnig et al., 2019).

Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome, and Cardiovascular Disease

The inflammation characterizing HIV/AUD may be compounded by obesity and metabolic syndrome. Obesity is increasing among PLWH and may be associated with ART (Bakal et al., 2018). High body mass is linked to inflammation and lowered cognitive performance in PLWH (Sattler et al., 2015; Okafor et al., 2017; Jumare et al., 2019; compare Rubin et al., 2019), as is broader metabolic syndrome, including diabetes mellitus (Valcour et al., 2006; McCutchan et al., 2012) (see Figure 2). Obesity is also a risk factor for hepatic disease and cardiovascular disease.

Hypertension is linked to HIV and to ART (Islam et al., 2012), as is cardiovascular disease (CVD) generally (reviewed in Gutierrez et al., 2017). Hypertension and CVD predict stroke (Gutierrez et al., 2015) and subtler neurocognitive changes among PLWH (Wright et al., 2010), although it is debated whether HIV compounds the cardiovascular disease-cognitive deficit pathway (Cysique & Brew, 2019; Sanford et al., 2019).

Obese PLWH are more likely than nonobese PLWH to use alcohol (Obry-Roguet et al., 2018) and to meet lifetime AUD criteria (Bauer, 2008). Sex may moderate this association, such that women with HIV/AUD are more obese and men with HIV/AUD less obese than moderate-drinking counterparts (Míguez-Burbano et al., 2013). Additionally, AUD is associated with CVD in PLWH (Freiberg et al., 2010; compare Kelso et al., 2015). Thus it is plausible that AUD may exacerbate obesity- or CVD-linked cognitive alterations in PLWH; however, at this time no research has addressed this question.

Other Substance Use

Tobacco (Bryant et al, 2013; Chang et al., 2017), cocaine (e.g., Ferris et al., 2008), opiates (e.g., Hauser et al., 2012), methamphetamine (Ferris et al., 2008; Weber et al., 2013) have all been linked to neuropathology or cognitive changes in PLWH. Additionally, tobacco and psychostimulants are linked to CVD (Raposeiras-Roubín et al., 2017; Mosunjac et al., 2008), and thus may exacerbate CVD-linked cognitive alterations in PLWH. However, few studies have examined the cognitive effects of comorbid AUD and other substance use in PLWH. Among PLWH without current non-AUD substance use disorders, opiate use corresponds with worsened learning and memory after accounting for alcohol use (Cohen et al., 2019). Within a HIV/AUD population, smokers showed reduced gray matter volume and poorer learning and memory (Durazzo et al., 2007); conversely, within the HIV/tobacco use population, Monnig et al. (2016) identified better learning among heavier drinkers. Overall, sweeping conclusions cannot be drawn without additional research in this area.

Nutritional Deficiencies

Alcohol abuse is associated with nutritional deficiencies due to reduced consumption of nutrient-rich food and decreased absorption and utilization of nutrients (Lieber, 2003). Nutrient deficiencies are also common in PLWH, attributable both to food insecurity (Ivers et al., 2009) and to increased gut permeability (reviewed in Shah et al., 2019). AUD increases the risk of food insecurity among PLWH (Normén et al., 2005) and, as discussed above, further damages the gut wall, decreasing nutrient absorption. Additionally, in simian models of HIV, chronic binge-like alcohol administration alters food choice, reducing overall caloric intake and percentage of calories from protein (Molina et al., 2006). In humans, alcohol use in PLWH contributes to nutritional deficiencies and consequently to cognitive changes (Hahn & Samet, 2010).

Thiamine deficiency is prominent in AUD (Mulholland, 2006), although some studies identify additional deficiencies, including in B12 and D vitamins (Gautron et al., 2018). Likewise, thiamine deficiency is recognized in PLWH (Lu’o’ng & Nguyễn, 2013). Thiamine deficiency is associated with episodic memory deficit and ataxia (Fama et al., 2019; Mulholland, 2006), and underlies Wernicke’s encephalopathy in both AUD and PLWH (Martin et al., 2003; Le Berre et al., 2019). The pattern of nutritional deficiencies in PLWH is wider, and in particular, B12 and D vitamin deficiencies have been linked to worse executive function and psychomotor speed among PLWH (Falasca et al., 2019). Specific profiles of deficiency associated with HIV/AUD are not yet established. Of note, B12 and D vitamin deficiencies are associated with decreased cognitive performance in aging (reviewed in Selhub, Troen, & Rosenberg, 2010; Wilkins et al., 2006) and may exacerbate cognitive vulnerability in the aging PLWH population.

Current and Future Directions in Research

Aging

The population of adults living with HIV is aging, with 30 to 50% of PLWH in the USA estimated to be over the age of 50 (Kirk & Goetz, 2009; Mahy et al., 2014) and this number projected to increase to 74% by 2035 (Smit et al., 2017). Aging’s detrimental effects on the CNS include loss of brain tissue volume, increased white matter microstructural dysfunction, and alterations in metabolite concentrations; these adverse effects interact with HIV pathophysiology, such that the effects of HIV on the brain have been characterized as premature or accelerated aging (Cohen et al., 2015). Older adults with HIV show faster memory decline than younger counterparts (Seider et al., 2014), indicating that the adverse effects of aging with HIV impact cognitive performance. Additionally, aging with HIV increases the risk of CNS-damaging comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, CVD, and liver cirrhosis (reviewed in Molina et al., 2018).

Aging also reduces the brain’s resilience to AUD-related pathology, with increasing age predicting worse cognitive outcomes and dampened recovery after abstinence (Rourke & Grant, 1999; Pitel et al., 2009). Heavy alcohol use and age may in combination reduce brain plasticity (reviewed in Mende, 2019), potentially limiting cognitive recovery in abstinent older adults.

Consequently, research attention has recently turned to aging with HIV/AUD (reviewed in Zahr, 2018). While cross-sectional studies of brain and cognition in this realm are scant, some evidence indicates age may impact cognitive recovery from prior AUD. PLWH older than 60 show past AUD-related executive function, processing speed, and semantic memory deficits, whereas younger PLWH with past AUD do not (Gongvatana et al., 2014). Conversely, older age when meeting AUD criteria predicts slower processing speed in HIV/past AUD, above and beyond the effects of current age (Paolillo et al., 2019).

Evidence for age-by-alcohol interactions for current drinkers is more mixed. In a longitudinal study, Pfefferbaum et al. (2018) observed accelerated brain aging in HIV/AUD, but not singly-diagnosed counterparts. However, Cohen et al. (2019) observed no age-alcohol interactive effect on cognitive outcomes among PLWH when stratifying at age 50. It is conceivable that some participants may compensate for age-related brain shrinkage in their 50s but experience poorer cognition later in life, but more longitudinal studies of cognition are required.

Protective Factors

It has been proposed that some individuals are less vulnerable to HIV/AUD pathophysiology or relatively able to compensate for neuropathological burden (e.g., Villalba et al., 2015). In recent years several genotypes have been identified as protective factors. Genes encoding dopamine (DRD4 and DRD2) and serotonin (TPH2 and GALM) signaling pathways have been linked to executive function and cognitive flexibility in HIV/AUD (Villalba et al., 2015; Villalba et al., 2016), and ADH4 gene variants linked to inter-individual differences in ethanol metabolism moderate the effects of HIV/AUD on working memory and executive function (Saloner et al., 2020). However, the mechanisms driving these genetic effects remain to be demonstrated.

American men living with HIV are more likely than female counterparts to report binge drinking and heavy alcohol use (Crane et al., 2017). Because women may be more prone than men to global cognitive deficit related to singly-diagnosed HIV (e.g., Sundermann et al., 2018) and visuospatial, executive, motor, verbal, and memory deficits in AUD (reviewed in Nixon et al., 2014), sex may impact vulnerability to HIV/AUD. However, no extant research has specifically examined sex effects on cognition in HIV/AUD comorbidity. As many research cohorts are predominantly male, sex effects may partially account for variation in cognitive profiles between studies.

Cognitive reserve, the ability to adapt cognitive processes to maintain performance despite neuropathological burden, also explains some outcome heterogeneity among PLWH (Foley et al., 2012; reviewed in Kaur et al., 2020). It is plausible that cognitive reserve may be protective in HIV/AUD, but specific relationships are presently unknown.

The closely related construct of functional reserve, or ability to maintain task performance by altering neural recruitment, protects cognition in AUD (reviewed in Chanraud & Sullivan, 2014). As we have seen, cognitively asymptomatic PLWH show hyperactivation in task-related regions and recruit adjacent brain regions to maintain task performance comparable to seronegative controls (Ernst et al., 2002; Caldwell et al., 2014; Cohen et al., 2018). However, fMRI has been underutilized in HIV/AUD comorbidity and functional reserve is understudied in this population.

Quantifying Drinking

Almost all existing research on HIV/AUD and cognition relies on self-report measures of alcohol use. However, self-report data are subject to inaccurate reporting, particularly among individuals with AUD (Toneatto et al., 1992). A recent study examining concordance between self-report and biometric measures of alcohol use in PLWH found that the Timeline Followback, which attempts to quantify daily drinking, is more sensitive to amount of alcohol used in this population than is the ten-item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (Ferguson et al., 2020). While findings in healthy populations indicate that daily self-report may be more reliable than retrospective measures such as the Timeline Followback (Merrill et al., 2020), daily assessments have not been extensively used in HIV/AUD. Given the episodic memory deficit common in HIV/AUD, retrospective assessments may be particularly discordant in this population, but this has not yet been experimentally tested. In future research, wrist-worn alcohol biosensors may reduce the need for self-report measures of alcohol use in HIV/AUD (Wang et al., 2019).

Assessment of past AUD is subject to similar considerations, given that lifetime consumption and period of heaviest drinking are typically self-reported. Structured interviews underestimated the prevalence of lifetime AUD (9.1% by retrospective report vs. 25.9% by cumulative data) in a population-based cohort study, particularly in adults older than 50 (Takayanagi et al., 2014). Most studies of lifetime AUD use retrospective structured interviews or self-report questionnaires (e.g., Cohen et al., 2019), rather than data collected during period of heaviest drinking, and therefore may underestimate lifetime AUD prevalence. Again, however, this effect remains speculative in HIV/AUD.

Drinking Patterns

AUD is not a homogeneous construct. The DSM-5 criteria for AUD incorporate non-physiological metrics such as guilt after drinking, and structured interviews (e.g., the SCID (Spitzer et al., 1992)) and self-report questionnaires such as the AUDIT likewise incorporate behavioral and emotional criteria (Babor et al., 2001). However, HIV/AUD pathophysiology may be specifically linked to frequency of consumption, to amount consumed per drinking session, or both. In particular, binge drinking (typically 5+ standard drinks for men or 4+ for women within 2 hours) (NIAAA, 2016) more strongly predicts reduced executive function, memory, and motor function in PLWH than does frequency of use or total lifetime consumption (Monnig et al., 2016; Cohen et al., 2019; contrast Attonito et al., 2014). Binge drinking also independently contributes to ART nonadherence, and thus to viral burden (Cook et al., 2017). Consequently, research using a binary AUD/no AUD classification may underreport the contributions of binge drinking to cognitive alterations.

Additionally, animal models of HIV/AUD pathophysiology typically approximate either acute binge drinking (e.g., Flora et al., 2005) or chronic but non-binge hazardous drinking (e.g., Potula et al., 2006); findings from individual animal studies may not generalize to all individuals meeting AUD criteria. To our knowledge, no alcohol administration studies have examined the acute effects of ethanol on inflammation, cognition, or markers of brain function in PLWH. Therefore, the degree to which animal models of acute ethanol-Tat interactions reflect disease progression in humans remains unknown.

Drinking History vs. Current Drinking

Reduction or cessation of alcohol use partially remediates cognitive changes in HIV- populations, in some studies within the first 2–3 weeks of abstinence (e.g., Petit et al., 2017). Findings in this domain are mixed, possibly due to variations in duration of abstinence, age at cessation of drinking (Rourke & Grant, 1999), and number of previous detoxification periods (Duka et al., 2003). However, typically cognitive function is not fully restored by abstinence (Le Berre et al., 2017).

Several cross-sectional studies have compared cognitive profiles of HIV/past AUD and HIV/current AUD. Light drinkers with HIV and lifetime DSM-III alcohol use or dependence show cognitive deficits (Green et al., 2004), and lifetime AUD history more strongly predicts poorer cognition than does current AUD in PLWH (Cohen et al., 2019). Age may moderate the effects of drinking reduction, with older adults with past AUD displaying worse global cognition, executive function, and processing speed performance relative to younger counterparts or controls without lifetime AUD (Gongvatana et al., 2014). However, no longitudinal studies have shown cognitive recovery within a cohort.

Estimated total lifetime alcohol consumption, length of period of heaviest drinking, and consumption during period of heaviest drinking have been used as alternate metrics of drinking history. Total lifetime consumption has not been shown to predict cognitive deficit in HIV/AUD (Fama et al. 2009, 2016; Byrd et al., 2011). However, quantity consumed during period of heaviest drinking predicts poorer processing speed, attention/executive function, learning, and verbal function, and duration of heaviest period of consumption predicts worsened memory and learning in PLWH (Cohen et al., 2019).

Conclusion

Chronic HIV infection remains a significant public health concern. Even virally-suppressed HIV infection is associated with worsened performance in several cognitive domains, and these changes can be exacerbated by comorbid AUD. Neuroimaging findings indicate a neural basis for HIV/AUD-linked cognitive deficit and point to underlying pathophysiology, including CNS inflammation and gray and white matter loss. HIV/AUD pathology likely arises from direct HIV protein and ethanol neurotoxicity, chronic inflammation, gut microbial translocation, and hepatic damage, and is compounded by comorbidities such as hepatitis C and cardiovascular disease. More research is needed to identify interactions between these pathways and factors protecting some PLWH from cognitive deficit.

References

- Adeli E, Zahr NM, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV, Pohl KM (2019). Novel Machine Learning Identifies Brain Patterns Distinguishing Diagnostic Membership of Human Immunodeficiency Virus, Alcoholism, and their Comorbidity of Individuals. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging 4: 589–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albright AV, Soldan SS, González-Scarano F (2003). Pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus-induced neurological disease. J Neurovirol 222–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amirsardari Z, Rahmani F, Rezaei N (2019). Cognitive impairments in HCV infection: From pathogenesis to neuroimaging. J Clin Exp Neuropsyc 41: 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ancuta P, Kamat A, Kuntstman JT, Kim EY, Autissier P, Wurcel A, Zaman T, Stone D, Mefford M, Morgello S, Singer EJ, Wolinsky SM, Gabuzda D (2008). Microbial Translocation Is Associated with Increased Monocyte Activation and Dementia in AIDS Patients. PLoS One 3: e2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony IC, Ramage SN, Carnie FW, Simmonds P, Bell JE (2005). Influence of HAART on HIV-Related CNS Disease and Neuroinflammation. J Neuropath Exp Neur 64: 529–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attonito JM, Dévieux JG, Lerner BDG, Hospital MM, Rosenberg R (2014). Exploring substance use and HIV treatment factors associated with neurocognitive impairment among people living with HIV/AIDS. Front Public Health 2: 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Saunders J, Grant M (2001). The alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): Guidelines for use in primary care. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj JS (2019). Alcohol, liver disease and the gut microbiota. Nat Rev Gastro Hepat 16: 235–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakal DR, Coelho LE, Luz PM, Clark JL, De Boni RB, Cardoso SW, Veloso VG, Lake JE, Grinsztejn B (2018). Obesity following ART initiation is common and influenced by both traditional and HIV-/ART-specific risk factors. J Antimicrob Chemother 73: 2177–2185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A, Abdelmegeed MA, Jang S, Song BJ (2015). Increased Sensitivity to Binge Alcohol-Induced Gut Leakiness and Inflammatory Liver Disease in HIV Transgenic Rats. PLoS One 10: e0140498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barokar J, McCutchan A, Deutsch R, Tang B, Cherner M, Bharti Ar (2019). Neurocognitive impairment is worse in HIV/HCV-coinfected individuals with liver dysfunction. J Neurovirol 25: 792–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreiro P, Rodríguez-Novoa S, Labarga P, Ruiz A, Jiménez-Nácher I, Martín-Carbonero L, Gonzalez-Lahoz J, Soriano V (2007). Influence of Liver Fibrosis Stage on Plasma Levels of Antiretroviral Drugs in HIV-Infected Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C. J Infect Dis 195: 973–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barve S, Kapoor R, Moghe A, Ramirez JA, Eaton JW, Gobejishvili L, Joshi-Barve S, McClain CJ (2010). Focus on the Liver: Alcohol Use, Highly Active Retroviral Therapy, and Liver Disease In HIV-Infected Patients. Alcohol Res Health 33: 229–236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer LO (2008). Psychiatric and neurophysiological predictors of obesity in HIV/AIDS. Psychophysiology 45: 1055–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista AP (2001). Free radicals, chemokines, and cell injury in HIV-1 and SIV infections and alcoholic hepatitis. Free Radic Biol Med 31: 1527–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendszus M, Weijers HG, Wiesbeck G, Warmuth-Metz M, Bartsch AJ, Engels S, Böning J, Solymosi L (2001). Sequential MR imaging and proton MR spectroscopy in patients who underwent recent detoxification for chronic alcoholism: correlation with clinical and neuropsychological data. Am J Neuroradiol 22: 1926–1932. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant VE, Kahler CW, Devlin KN, Monti PM, Cohen RA (2013). The effects of cigarette smoking on learning and memory performance among people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care 25: 1308–1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bühler M, Mann K (2011). Alcohol and the Human Brain: A Systematic Review of Different Neuroimaging Methods. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 35: 1771–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd DA, Fellows RP, Morgello S, Franklin D, Heaton RK, Deutsch R, Atkinson JH, Clifford DB, Collier AC, Marra CM, Gelman B, McCutchan JA, Duarte NA, Simpson DM, McArthur J, Grant I (2011). Neurocognitive Impact of Substance Use in HIV Infection J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 58: 154–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JZ, Gongvatana A, Navia BA, Sweet LH, Tashima K, Ding M, Cohen RA (2014). Neural dysregulation during a working memory task in human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive and hepatitis C coinfected individuals. J Neurovirol 20: 398–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chander G, Lau B, Moore RD (2006). Hazardous Alcohol Use: A Risk Factor for Non-Adherence and Lack of Suppression in HIV Infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 43: 411–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Ernst T, St Hillaire C, Conant K (2004). Antiretroviral treatment alters relationship between MCP-1 and neurometabolites in HIV patients. Antivir Ther 9: 431–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Ernst T, Witt MD, Ames N, Gaiefsky M, Miller E (2002). Relationships among Brain Metabolites, Cognitive Function, and Viral Loads in Antiretroviral-Naïve HIV Patients. NeuroImage 17: 1638–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Ernst T, Witt MD, Ames N, Walot I, Jovicich J, DeSilva M, Trivedi N, Speck O, Miller EN (2003). Persistent brain abnormalities in antiretroviral-naive HIV patients 3 months after HAART. Antivir Ther 8: 17–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Lim A, Lau E, Alicata D (2017). Chronic Tobacco-Smoking on Psychopathological Symptoms, Impulsivity, and Cognitive Deficits in HIV-Infected Individuals. J Neuroimmune Pharm 12: 389–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanraud S, Pitel AL, Rohlfing T, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV (2010). Dual Tasking and Working Memory in Alcoholism: Relation to Frontocerebellar Circuitry. Neuropsychopharmacology 35: 1868–1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanraud S, Sullivan EV (2014). Chapter 22 - Compensatory recruitment of neural resources in chronic alcoholism. Handb Clin Neurol 125: 369–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarelli N, Fabbiani M, Brita AC, De Marco R, Grima P, Gagliardini R, Borghetti A Cauda R, Di Giambenedetto S (2019). Liver fibrosis is associated with cognitive impairment in people living with HIV. Infection 47: 589–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RA, Boland R, Paul R, Tashima KT, Schoenbaum EE, Celentano DD, Schuman P, Smith DK, Carpenter CC (2001). Neurocognitive performance enhanced by highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected women. AIDS 15: 341–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RA, Gullett JM, Porges EC, Woods AJ, Lamb DG, Bryant VE, McAdams M, Tashima K, Cook R, Bryant K, Monnig M, Kahler CW, Monti PM (2019). Heavy Alcohol Use and Age Effects on HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Function. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 43: 147–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RA, Harezlak J, Gongvatana A, Buchthal S, Schiffito G, Clark U, Paul R, Taylor M, Thompson P, Tate D, Alger J, Brown M, Zhong J, Campbell T, Singer E, Daar E, McMahon D, Tso Y, Yiannoutsos CT, Navia B (2010). Cerebral metabolite abnormalities in human immunodeficiency virus are associated with cortical and subcortical volumes. J Neurovirol 16: 435–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RA, Seider TR, Navia B (2015). HIV effects on age-associated neurocognitive dysfunction: premature cognitive aging or neurodegenerative disease? Alzheimer’s Res Ther 7: 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RA, Siegel S, Gullett JM, Porges E, Woods AJ, Huang H, Zhu Y, Tashima K, Ding MZ (2018). Neural response to working memory demand predicts neurocognitive deficits in HIV. J Neurovirol 24: 291–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook RL, Zhou Z, Kelso-Chichetto NE, Janelle J, Morano JP, Somboonwit C, Carter W, Ibanez GE, Ennis N, Cook CL, Cohen RA, Brumback B, Bryant K (2017). Alcohol consumption patterns and HIV viral suppression among persons receiving HIV care in Florida: an observational study. Addict Sci Clin Pract 12: 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook RL, Zhou Z, Miguez MJ, Quiros C, Espinoza L, Lewis JE, Brumback B, Bryant K (2019). Reduction in Drinking was Associated With Improved Clinical Outcomes in Women With HIV Infection and Unhealthy Alcohol Use: Results From a Randomized Clinical Trial of Oral Naltrexone Versus Placebo. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 43: 1790–1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney KE, Gharhemani DG, Ray LA (2013). Fronto-striatal functional connectivity during response inhibition in alcohol dependence. Addict Biol 18: 593–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane HM, McCaul ME, Chander G, Hutton H, Nance RM, Delaney JAC, Merrill JO, Lau B, Mayer KH, Mugavero MJ, Mimiaga M, Willig JH, Burkholder GA, Drozd DR, Fredericksen RJ, Cropsey K, Moore RD, Simoni JM, Mathews WC, Eron JJ, Napravnik S, Christopoulos K, Geng E, Saag MS, Kitahata MM (2017). Prevalence and Factors Associated with Hazardous Alcohol Use Among Persons Living with HIV Across the US in the Current Era of Antiretroviral Treatment. AIDS Behav 21: 1914–1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cysique LA, Brew BJ (2019). Vascular cognitive impairment and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder: a new paradigm. J Neurovirol 25: 710–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis BC, Bajaj JS (2018). Effects of Alcohol on the Brain in Cirrhosis: Beyond Hepatic Encephalopathy. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 42: 660–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Q, Kelkar S, Xiao Y, Joshi-Barve S, McClain CJ, Barve SS (2000). Ethanol enhances TNF-α–inducible NFκB activation and HIV-1-LTR transcription in CD4+ Jurkat T lymphocytes. J Lab Clin Med 136: 333–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do TC, Kerr SJ, Avihingsanon A, Suksawek S, Klungkang S, Channgam T, Odermatt CC, Maek-a-nantawat W, Ruxtungtham K, Ananworanich J, Valcour V, Reiss P, Wit FW (2018). HIV-associated cognitive performance and psychomotor impairment in a Thai cohort on long-term cART. J Virus Erad 4: 41–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas-Newman KR, Smith RV, Spiers MV, Pond T, Kranzler HR (2017). Effects of Recent Alcohol Consumption Level on Neurocognitive Performance in HIV+ Individuals. Addict Disord Their Treat 16: 95–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duka T, Townshend JM, Collier K, Stephens DN (2003). Impairment in Cognitive Functions After Multiple Detoxifications in Alcoholic Inpatients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 27: 1563–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duko B, Ayalew M, Ayano G (2019). The prevalence of alcohol use disorders among people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 14: 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy M, Chanraud S (2016). Imaging the Addicted Brain: Alcohol. Int Rev Neurobiol 129: 1–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Gazdzinski S, Rothlind JC, Banys P, Meyerhoff DJ (2006). Brain Metabolite Concentrations and Neurocognition During Short-Term Recovery from Alcohol Dependence: Preliminary Evidence of the Effects of Concurrent Chronic Cigarette Smoking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 30: 539–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Rothlind JC, Cardenas VA, Studholme C, Weiner MW, Meyerhoff DJ (2007). Chronic cigarette smoking and heavy drinking in human immunodeficiency virus: consequences for neurocognition and brain morphology. Alcohol 41: 489–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durvasula R, Myers HF, Mason K, Hinkin C (2006). Relationship between Alcohol Use/Abuse, HIV Infection and Neuropsychological Performance in African American Men. J Clin Exp Neuropsyc 3: 383–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst T, Chang L, Arnold S (2003). Increased glial metabolites predict increased working memory network activation in HIV brain injury. Neuroimage 19: 1686–1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst T, Chang L, Jovicich J, Ames N, Arnold S (2002). Abnormal brain activation on functional MRI in cognitively asymptomatic HIV patients. Neurology 59: 1343–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettenhofer ML, Foley J, Castellon SA, Hinkin CH (2010). Reciprocal prediction of medication adherence and neurocognition in HIV/AIDS. Neurology 74: 1217–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falasca K, Di Nicola M, Di Martino G, Ucciferri C, Vignale F, Occhionero A, Vecchiet J (2019). The impact of homocysteine, B12, and D vitamins levels on functional neurocognitive performance in HIV-positive subjects. BMC Infect Dis 19: 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falasca K, Reale M, Ucciferri C, Di Nicola M, Di Martino G, D’Angelo C, Coladonato S, Vecchiet J (2017). Cytokines, Hepatic Fibrosis, and Antiretroviral Therapy in Neurocognitive Disorders HIV Related. AIDS Res Hum Retrov 33: 246–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fama R, Eisen JC, Rosenbloom MJ, Sassoon SA, Kemper CA, Deresinski S, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV (2007). Upper and lower limb motor impairments in alcoholism, HIV infection, and their comorbidity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 31: 1038–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fama R, Le Berre AP, Hardcastle C, Sassoon SA, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV, Zahr NM (2019). Neurological, nutritional and alcohol consumption factors underlie cognitive and motor deficits in chronic alcoholism. Addict Biol 24: 290–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fama R, Rosenbloom MJ, Nichols BN, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV (2009). Working and Episodic Memory in HIV Infection, Alcoholism, and Their Comorbidity: Baseline and 1-Year Follow-Up Examinations. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 33: 1815–1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fama R, Rosenbloom MJ, Sassoon SA, Rohlfing T, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV (2014). Thalamic volume deficit contributes to procedural and explicit memory impairment in HIV infection with primary alcoholism comorbidity. Brain Imaging Behav 8: 611–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fama R, Rosenbloom MJ, Sassoon SA, Thompson MA, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV (2011). Remote semantic memory for public figures in HIV infection, alcoholism, and their comorbidity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 35: 265–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fama R, Sullivan EV, Sassoon SA, Pfefferbaum A, Zahr NM (2016) Impairments in Component Processes of Executive Function and Episodic Memory in Alcoholism, HIV Infection, and HIV Infection with Alcoholism Comorbidity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 40: 2656–2666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson TK, Theall KP, Brashear M, Maffei V, Beauchamp A, Siggins RW, Simon L, Mercante D, Nelson S, Welsh DA, Molina PE (2020). Comprehensive Assessment of Alcohol Consumption in People Living with HIV (PLWH): The New Orleans Alcohol Use in HIV Study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 44: 1261–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris MJ, Mactutus CF, Booze RM (2008). Neurotoxic profiles of HIV, psychostimulant drugs of abuse, and their concerted effect on the brain: Current status of dopamine system vulnerability in NeuroAIDS. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 32: 883–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flora G, Pu H, Lee YW, Ravikumar R, Nath A, Hennig B, Toborek M (2005). Proinflammatory synergism of ethanol and HIV-1 Tat protein in brain tissue. Exp Neurol 191: 2–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley JM, Ettenhofer ML, Kim MS, Behdin N, Castellon SA, Hinkin CH (2012). Cognitive Reserve as a Protective Factor in Older HIV-Positive Patients at Risk for Cognitive Decline. Appl Neuropsychol Adult 19: 16–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forton DM, Hamilton G, Allsop JM, Grover VP, Wesnes K, O’Sullivan C, Thomas HC, Taylor-Robinson SD (2008). Cerebral immune activation in chronic hepatitis C infection: A magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. J Hepatol 49: 316–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forton DM, Thomas HC, Murphy CA, Allsop JM, Foster GR, Main J, Wesnes KA, Taylor-Robinson SD (2002). Hepatitis C and Cognitive Impairment in a Cohort of Patients With Mild Liver Disease. Hepatology 35: 433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MD, Greicius M (2010). Clinical applications of resting state functional connectivity. Front Syst Neurosci 4: 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freiberg MS, McGinnis KA, Kraemer K, Same JH, Conigliaro J, Ellison RC, Bryant K, Kuller LH, Justice AC (2010). The association between alcohol consumption and prevalent cardiovascular diseases among HIV infected and uninfected men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 53: 247–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan FH, Bing EG, Fleishman JA, London AS, Caetano R, Burnam MA, Longshore D, Morton SC, Orlando M, Shapiro M (2002). The prevalence of alcohol consumption and heavy drinking among people with HIV in the United States: results from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. J Stud Alcohol 63: 179–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautron MA, Questel F, Lejoyeux M, Bellivier F, Vorspan F (2018). Nutritional Status During Inpatient Alcohol Detoxification. Alcohol Alcohol 53: 64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge S, Sanchez M, Nolan M, Liu T, Savage C (2018). Is Alcohol Use Associated With Increased Risk of Developing Adverse Health Outcomes Among Adults Living With Human Immunodeficiency Virus. J Addict Nurs 29: 96–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gongvatana A, Morgan EE, Iudicello JE, Letendre SL, Grant I, Woods SP (2014). A history of alcohol dependence augments HIV-associated neurocognitive deficits in persons aged 60 and older. J Neurovirol 20: 505–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gongvatana A, Woods SP, Taylor MJ, Vigil O, Grant I (2007). Semantic Clustering Inefficiency in HIV-Associated Dementia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 19: 36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Scarano F, Martín-García J (2005). The neuropathogenesis of AIDS. Nat Rev Immunol 5: 69–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant I, Franklin DR, Deutsch R, Woods SP, Vaida F, Ellis RJ, Letendre SL, Marcotte TD, Atkinson JH, Collier AC, Marra CM, Clifford DB, Gelman BB, McArthur JC, Morgello S, Simpson DM, McCutchan JA, Abramson I, Gamst A, Fennema-Notestine C, Smith DM, Heaton RK (2014). Asymptomatic HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment increases risk for symptomatic decline. Neurology 82: 2055–2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray LR, Roche M, Flynn JK, Wesselingh SL, Gorry PR, Churchill MJ (2014). Is the central nervous system a reservoir of HIV-1? Curr Opin HIV AIDS 9: 552–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JE, Saveanu RV, Bornstein RA (2004). The Effect of Previous Alcohol Abuse on Cognitive Function in HIV Infection. Am J Psychiatry 161: 249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover VPB, Pavese N, Koh SB, Wylezinska M, Saxby BK, Gerhard A, Forton DM, Brooks DJ, Thomas HC, Taylor-Robinson SD (2012). Cerebral microglial activation in patients with hepatitis c: in vivo evidence of neuroinflammation. J Viral Hepatitis 19: e89–e96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullett JM, Lamb DG, Porges E, Woods AJ, Rieke J, Thompson P, Jahanshad N, Nir TM, Tashima K, Cohen RA (2018). The Impact of Alcohol Use on Frontal White Matter in HIV. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 42: 1640–1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez J, Albuquerque ALA, Falzon L (2017). HIV infection as vascular risk: A systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. PLoS One 12: e0176686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez J, Goldman J, Dwork AJ, Elkind MSV, Marshall RS, Morgello S (2015). Brain arterial remodeling contribution to nonembolic brain infarcts in patients with HIV. Neurology 85: 1139–1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn JA, Samet JH (2010). Alcohol and HIV Disease Progression: Weighing the Evidence. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 7: 226–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakkers CS, Arends JE, Barth RE, Plessis SD, Hoepelman AIM, Vink M (2017). Review of functional MRI in HIV: effects of aging and medication. J Neurovirol 23: 20–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harezlak J, Buchthal S, Taylor M, Schifitto G, Zhong J, Daar E, Alger J, Singer E, Campbell T, Yiannoutsos C, Cohen R, Navia B (2011). Persistence of HIV-associated cognitive impairment, inflammation, and neuronal injury in era of highly active antiretroviral treatment. AIDS 25: 625–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harezlak J, Cohen R, Gongvatana A, Taylor M, Buchthal S, Schifitto G, Zhong J, Daar ES, Alger JR, Brown M, Singer EJ, Campbell TB, McMahon D, So YT, Yiannoutsos CT, Navia BA (2014). Predictors of CNS injury as measured by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in the setting of chronic HIV infection and CART. J Neurovirol 20: 294–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser KF, Fitting S, Dever SM, Podhaizer E, Knapp PE (2012). Opiate Drug Use and the Pathophysiology of NeuroAIDS. Curr HIV Res 5: 435–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaps J, Niehoff J, Lane E, Kroutil K, Boggiano J, Paul R (2011). Application of Neuroimaging Methods to Define Cognitive and Brain Abnormalities Associated with HIV, in Brain Imaging in Behavioral Medicine and Clinical Neuroscience (Cohen R, Sweet L eds), pp 341–353. Springer, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, Woods SP, Ake C, Vaida F, Ellis RJ, Letendre SL, Marcotte TD, Atkinson JH, Rivera-Mindt M, Vigil OR, Taylor MJ, Collier AC, Marra CM, Gelman BB, McArthur JC, Morgello S, Simpson DM, McCutchan JA, Abramson I, Gamst A, Fennema-Notestine C, Jernigan TL, Wong J, Grant I (2010). HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy. Neurology 75: 2087–2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Ellis RJ, McCutchan JA, Letendre SL, LeBlanc S, Corkran SH, Duarte NA, Clifford DB, Woods SP, Collier AC, Marra CM, Morgello S, Riviera Mindt M, Taylor MJ, Marcotte TD, Atkinson Hampton J, Wolfson T, Gelman BB, McArthur JC, Simpson DM, Abramson I, Gamst A, Fennema-Notestine C, Jernigan TL, Wong J, Grant I (2011). HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before and during the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: differences in rates, nature, and predictors. J Neurovirol 17: 3–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilsabeck RC, Hassanein TI, Carlson MD, Ziegler EA, Perry W (2003). Cognitive functioning and psychiatric symptomatology in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Int Neuropsych Soc 9: 847–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilsabeck RC, Perry W, Hassanein TI (2002). Neuropsychological impairment in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 35: 440–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkin CH, Castellon SA, Levine AJ, Barclay TR, Singer EJ (2008). Neurocognition in Individuals Co-Infected with HIV and Hepatitis C. J Addict Dis 2: 11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua X, Boyle CP, Harezlak J, Tate DF, Yiannoutsos CT, Cohen R, Schiffito G, Gongvatana A, Zhong J, Tong Z, Taylor MJ, Campbell TB, Daar ES, Alger JR, Singer E, Buchthal S, Toga AW, Navia B, Thompson B, HIV Neuroimaging Consortium (2013). Disrupted cerebral metabolite levels and lower nadir CD4+ counts are linked to brain volume deficits in 210 HIV-infected patients on stable treatment. NeuroImage: Clinical 3: 132–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imp BM, Rubin LH, Tien PC, Plankey MW, Golub ET, French EL, Valcour VG (2017). Monocyte Activation is Associated With Worse Cognitive Performance in HIV-Infected Women With Virologic Suppression. J Infect Dis 215: 114–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ipser JC, Brown GG, Bischoff-Grethe A, Connolly CG, Ellis RJ, Heaton RK, Grant I (2015). HIV Infection Is Associated with Attenuated Frontostriatal Intrinsic Connectivity: A Preliminary Study. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 21: 203–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam FM, Wu J, Jansson J, Wilson DP (2012). Relative risk of cardiovascular disease among people living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HIV Med 13: 453–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivers LC, Cullen KA, Freedberg KA, Block S, Coates J, Webb P, Mayer KH (2009). HIV/AIDS, Undernutrition, and Food Insecurity. Clin Infect Dis 49: 1096–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumare J, El-Kamary SS, Magder L, Hungerford L, Umlauf A, Franklin D, Ghate M, Abimiku A, Charurat M, Letendre S, Ellis RJ, Mehendale S, Blattner WA, Royal W, Marcotte TD, Heaton RK, Grant I, McCutchan JA (2019). Body Mass Index and Cognitive Function Among HIV-1-Infected Individuals in China, India, and Nigeria. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 80: e30–e85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul M, Zheng K, Okamoto S, Gendelman HE, Lipton SA (2005). HIV-1 infection and AIDS: consequences for the central nervous system. Cell Death Differ 12: 878–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur N, Dendukuri N, Fellows LK, Brouilette MJ, Mayo N (2020). Association between cognitive resreve and cognitive performance in people with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Care 32: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelso NE, Sheps DS, Cook RL (2015). The association between alcohol use and cardiovascular disease among people living with HIV: a systematic review. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 41: 479–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk JB, Goetz MB (2009). Human Immunodeficiency Virus in an Aging Population, a Complication of Success. J Am Geriatr Soc 57: 2129–2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn T, Sayegh P, Jones JD, Smith J, Sarma MK, Ragin A, Singer EJ, Thomas MA, Thames AD, Castellon SA, Hinkin CH (2017). Improvements in brain and behavior following eradication of hepatitis C. J Neurovirol 23: 593–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]