Abstract

Background

People with psychosis are at higher risk of cardiovascular events, partly explained by a higher predisposition to gain weight. This has been observed in studies on individuals with a first-episode psychosis (FEP) at short and long term (mainly up to 1 year) and transversally at longer term in people with chronic schizophrenia. However, there is scarcity of data regarding longer-term (above 3-year follow-up) weight progression in FEP from longitudinal studies. The aim of this study is to evaluate the longer-term (10 years) progression of weight changes and related metabolic disturbances in people with FEP.

Methods

Two hundred and nine people with FEP and 57 healthy participants (controls) were evaluated at study entry and prospectively at 10-year follow-up. Anthropometric, clinical, and sociodemographic data were collected.

Results

People with FEP presented a significant and rapid increase in mean body weight during the first year of treatment, followed by less pronounced but sustained weight gain over the study period (Δ15.2 kg; SD 12.3 kg). This early increment in weight predicted longer-term changes, which were significantly greater than in healthy controls (Δ2.9 kg; SD 7.3 kg). Weight gain correlated with alterations in lipid and glycemic variables, leading to clinical repercussion such as increments in the rates of obesity and metabolic disturbances. Sex differences were observed, with women presenting higher increments in body mass index than men.

Conclusions

This study confirms that the first year after initiating antipsychotic treatment is the critical one for weight gain in psychosis. Besides, it provides evidence that weight gain keep progressing even in the longer term (10 years), causing relevant metabolic disturbances.

Keywords: Cholesterol, glucose, medication-naïve, second-generation antipsychotic, triglycerides, weight gain

Introduction

People with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder present an excess morbidity and mortality when compared with the general population, leading to a reduced life expectancy [1–3]. It has been described that cardiometabolic disorders are among the main natural causes of this excess mortality [4, 5]. Weight increments and related metabolic changes explaining the latter cardiometabolic events appear early in the course of the psychotic disorder [6]. In this sense, the first year of the first-episode psychosis (FEP) appears as the critical period for the development of the metabolic disturbances. For instance, up to 80% of the weight increase observed at long term (3 years) occurred in this critical period; despite of this, FEP participants continued gaining weight even after this critical period, although at a slower pace [7]. This observation is also supported by other studies showing that people with psychosis present weight gain and metabolic disturbances during the first 3–4 years of initiating the antipsychotic treatment [8, 9]. Studies, based on individuals with stablished schizophrenia, following cross-sectional and retrospective methodologies, also showed the presence of weight increments even at longer periods [10–13]. Together with this increase in body weight, and mainly as a consequence of it [7, 14], a wide range of lipid and glycemic metabolism alterations appear progressively in people with psychosis in parallel with the progression of the mental disorder. For instance, Gardner-Sood et al. [11] reported in a group of 450 participants with chronic psychosis that half of them were obese, and 57% met criteria for metabolic syndrome, while a fifth met the criteria for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Similarly, Henderson et al. [13] reported an increase in body mass index (BMI), cholesterol, triglycerides, and the risk for diabetes, in people with schizophrenia, after 10 years of having initiated treatment with clozapine. Although there is mounting evidence regarding a differential effect of antipsychotic treatments on weight gain [15], there is scarcity of evidence from prospective longitudinal studies analyzing the progression of weight and metabolic changes at long term (10 years) in people with FEP; most of the scientific evidence comes from short-term and cross-sectional studies or from retrospective reviews of medical records.

Taking into account the above evidences, we hypothesize that people with FEP will present, at 10-year follow-up, a significant increase in weight and metabolic disturbances that will be significantly greater than that observed in healthy participants. This study aims to explore prospectively the pattern of weight changes and the occurrence of metabolic disturbances in a cohort of individuals with a FEP followed during the first 10 years after the breakout of their FEP. And secondly, to compare them with a group of healthy (without psychiatric disorders) participants.

Methods

Study setting

The study was part of a prospective longitudinal project on FEP, the “First Episode Psychosis Clinical Program 10” (PAFIP10) study [16]. PAFIP-10 is a follow-up at approximately 10 years (range between 8 and 12) of a cohort of individuals with a first episode of nonaffective psychosis initially included in the Cantabria Program for Early Intervention in Psychosis (PAFIP) [17].

The study was approved by the local ethics committee for clinical research (CEIm Cantabria) in accordance with international standards for research ethics (trial number NCT02200588). Participants included in the study provided written informed consent for entry initially into PAFIP and for PAFIP-10 reassessment.

Baseline inclusion criteria

All referrals to PAFIP between February 2001 and July 2008 were screened against the following inclusion criteria: age 15–60 years; living in the catchment area; experiencing a FEP; no prior treatment with antipsychotic medication or, if previously treated, a total lifetime of adequate antipsychotic treatment of less than 6 weeks. DSM-IV criteria for drug or alcohol dependence, intellectual disability, and having a history of neurological disease or head injury were exclusion criteria. The diagnoses were confirmed through the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID–I) [18]. A group of subjects without psychiatric illness was recruited as control group through public advertisements, from the same catchment area. Individuals in the control group were matched to FEP cases for age, sex, and ethnicity.

Participants’ clinical assessment

Sociodemographic and clinical information was recorded from interviews with participants, their relatives, and from medical records on each time point. Clinical data were collected at four different points throughout the 10-year period; baseline, 1-, 3- and 10-year follow-up. Clinical symptoms of psychosis were assessed by the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) [19] and the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) [20], and general psychopathology with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) [21]. Participants’ weight and waist circumference were obtained at all time points, while height was measured at the time of enrollment.

Participants from the healthy control group were evaluated at baseline and 10 years after, where sociodemographic and biometric data were collected.

Laboratory analyses

All laboratory determinations were performed at the same site, in our hospital, after an overnight fast, at baseline, 1-, 3-, and 10-year follow-ups. Fasting state, as well as treatment compliance (good compliance: taking ≥ 90% of the prescribed treatment), was reported by patients and their family members. Glucose, total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and triglycerides were measured by automated methods on a TechniconDax (Technicon Instruments Corp, Tarrytown, NY), using the reagents supplied by Boehringer-Mannheim (Mannheim, Germany). Low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol was determined by the Friedewald et al. [23] calculation. Insulin levels were measured by an immunoradiometric assay (Immunotech, Beckman Coulter Company, Prague, Czech Republic), where values for normal weight subjects are 2–17 μU/ml. Insulin resistance was calculated using the homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) index, by means of a previously described formula [22], and through the triglyceride/HDL cholesterol (TG/HDL) ratio, as proposed by McLaughlin et al. [24], and with the cut-off point of 3.5.

Statistical analyses

To evaluate the changes over time of weight, BMI, lipid, and glycemic measurements in FEP, we used repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVA) followed by post-hoc Bonferroni tests. For these analyses, we included baseline, 1-, 3-, and 10-year measurements.

Next, we explored if there were significant differences in the longitudinal changes between people with FEP and controls. For this, we carried out ANCOVA models where mean variable change (10-year minus baseline measures) was used as the dependent variable, subject group (FEP vs. control) as the fixed factor, and baseline BMI, baseline measurement data, age, and sex as covariates.

To evaluate the clinical impact of the metabolic changes observed in the FEP group, we additionally calculated the percentage of participants with pathologic values in BMI and glucose and lipid variables (according to the reference values of our laboratory) at baseline and at 10-year follow-up. To evaluate significant changes in these percentages, we used the McNemar test for repeated measures.

Finally, we studied the association between weight gain and metabolic changes. For this, we performed a partial correlation analysis controlling by sex, age, and baseline BMI. And subsequently, we compared the changes in glycemic and lipid measurements in three different FEP groups regarding the increase in BMI from baseline (7, 15 [25]): less than 7% increase, between 7 and 20%, and greater than 20%. The three groups were compared using covariance analysis.

Secondary analyses were carried out to explore sex effect on the long-term weight and metabolic changes in the FEP cohort through ANCOVA test. And finally, prediction factors of weight gain were explored using a cumulative odds ordinal logistic regression with proportional odds to determine the effect of sex, age, duration of untreated psychosis (DUP), treatment discontinuation, weight gained at 1 year, HOMA index, leptin, triglycerides, LDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol at baseline on critical weight gain (≥20% from baseline) at 10 years.

The Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY) was used for the statistical analyses. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and the significance was determined at the 0.05 level.

Results

Characteristics of the cohort

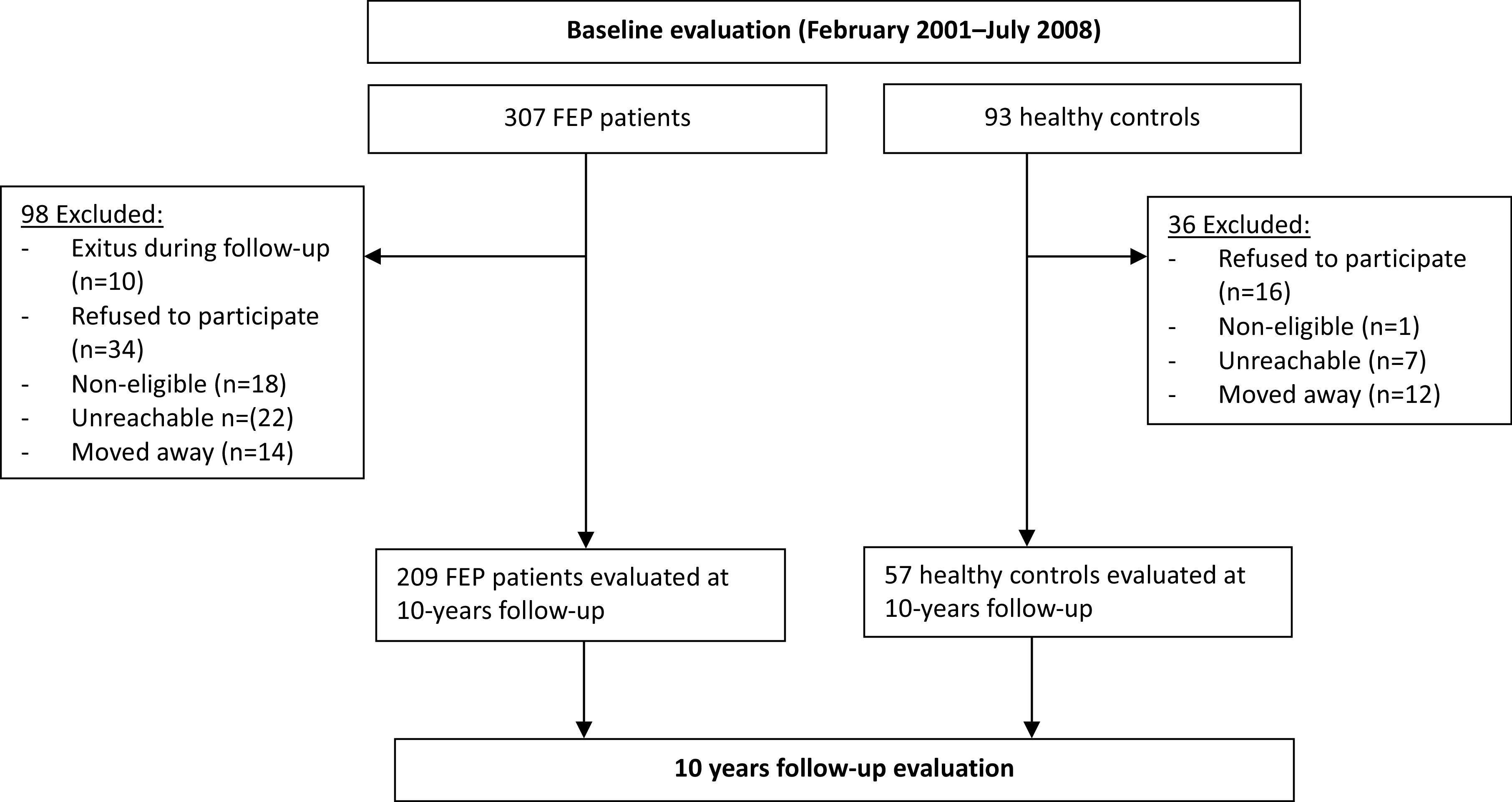

A total of 209 patients and 57 healthy controls were evaluated after 10 years of having initiated treatment (Figure 1). FEP patients and healthy controls had similar baseline sociodemographic characteristics (Table 1). At program admission FEP patients had a mean age of 29.3 years (SD = 8.8), most of them were men (54.5%), white (98.6%), from low-middle socioeconomic status (54.6%), and 71.8% lived with family. Mean DUP was 13.6 months (SD = 29.7), and at presentation the mean SAPS, SANS, and BPRS were 13.3 (SD = 4.6), 7.8 (SD = 6.4), and 62.0 (SD = 13.2), respectively. At baseline, 56.5% reported consuming tobacco, 51.7% alcohol, and 37.8% cannabis. At 6-month follow-up, 61.2% had a confirmed diagnosis of schizophrenia, 1.4% schizoaffective, 23.4% schizophreniform, 7.2% brief psychotic episode, and 6.7% unspecified psychotic disorder. At the 10-year follow-up, we evaluated 57 individuals from the control group.

Figure 1.

Participants’ flow in the study.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of study population.

| FEP patients N = 209 | Healthy controls N = 57 | Total N = 266 | Statistics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Stat. | Value | p | |

| Age at admission, years | 29.3 | 8.8 | 28.6 | 8.3 | 29.2 | 8.7 | t | 0.563 | 0.574 |

| Education, years | 10.8 | 3.4 | 10.8 | 2.5 | 10.8 | 3.2 | t | −0.117 | 0.907 |

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||||

| Sex, male | 114 | 54.5 | 33 | 57.9 | 147 | 55.3 | X 2 | 0.203 | 0.652 |

| Ethnicity, white | 206 | 98.6 | 53 | 100.0 | 259 | 98.9 | Fisher | 0.770 | 1.000 |

| Education level, secondary or lower | 92 | 44.0 | 17 | 32.1 | 109 | 41.6 | X 2 | 2.482 | 0.115 |

| Family socioeconomic status, not/low qualified | 113 | 54.6 | 20 | 38.5 | 133 | 51.4 | X 2 | 4.327 | 0.038 |

| Single | 158 | 75.6 | 13 | 50.0 | 171 | 72.8 | X 2 | 7.646 | 0.006 |

| Employed/Studying, yes | 115 | 55.0 | 23 | 88.5 | 138 | 58.7 | X 2 | 10.666 | 0.001 |

| Tobacco smoking, yes | 118 | 56.5 | 31 | 55.4 | 149 | 56.2 | X 2 | 0.022 | 0.883 |

| Cannabis use, yes | 79 | 37.8 | 16 | 28.6 | 95 | 35.8 | X 2 | 1.635 | 0.201 |

| Alcohol drinking, yes | 108 | 51.7 | 33 | 62.3 | 141 | 53.8 | X 2 | 1.908 | 0.167 |

Abbreviation: FEP, first-episode psychosis.

The majority of patients (95.2%, n = 199) in this sample were antipsychotic-naïve at study entry. The other 10 patients (4.8%) had been treated with antipsychotics prior to their inclusion in the study, although during a short period of time (median = 5 days). According to the patients and their families’ reports on treatment compliance, 76.9% of patients were good compliers at 1 year, 79.1% at 3 years, and 92.7% at 10 years. Some of the patients were on other concomitant psychopharmacological treatments that potentially contribute to weight gain. Thus, 38 patients (18.2%) were on antidepressant treatment at 1-year follow up, 30 (14.3%) at 3 years, and 36 (17.2%) at 10 years. Besides, six patients (2.9%) were on treatment with mood stabilizers at 1-year follow-up, 13 (6.2%) at 3 years, and 29 (13.9%) at 10 years. Patients presented a high rate of antipsychotic treatment switch during the study period (Supplementary Table S3).

Weight and metabolic differences after 10 years of psychosis breakout

Individuals with FEP presented a significant increase in their mean weight and BMI, 10 years after their psychosis diagnosis. The mean weight gain in this period was 15.2 kg (SD = 12.6) (Table 2). The majority (80.8%) of patients experienced a clinically significant weight gain (>7% from baseline), with 32.5% of patients having increased between 20 and 40% of their basal body weight, and 18.7% even above 40% of their basal weight.

Table 2.

Descriptive data and ANOVA repeated measures analyses of body weight and metabolic changes during the first 10 years of antipsychotic treatment in a population of individuals with a first-episode psychosis.

| Baseline mean (SD) | n | 1 year mean (SD) | n | 3 years mean (SD) | n | 10 years mean (SD) | n | F repeated measures a | df | p | Partial eta squared | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometric changes | ||||||||||||

| Weight (kg) | 67.0 (13.4) | 206 | 76.0 (15.5) | 197 | 77.4 (16.3) | 187 | 82.4 (18.3) | 206 | 103.9 | 3; 176 | <0.001 | 0.643 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.6 (3.7) | 204 | 26.6 (4.3) | 195 | 27.3 (4.7) | 186 | 29.0 (5.8) | 204 | 105.4 | 3; 176 | <0.001 | 0.646 |

| Lipid parameters | ||||||||||||

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 174.6 (36.9) | 207 | 193.9 (38.6) | 199 | 195.7 (40.1) | 193 | 197.3 (38.6) | 199 | 26.2 | 3; 178 | <0.001 | 0.310 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 108.5 (32.7) | 183 | 123.5 (33.1) | 196 | 120.7 (33.1) | 188 | 122.5 (32.2) | 191 | 17.3 | 3; 148 | <0.001 | 0.263 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 50.4 (13.9) | 182 | 49.8 (12.4) | 196 | 51.0 (14.7) | 191 | 28.9 (13.1) | 194 | 2.2 | 3; 151 | 0.087 | 0.043 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 84.4 (39.9) | 181 | 114.6 (87.2) | 195 | 120.6 (115.8) | 192 | 129.7 (80.4) | 195 | 20.7 | 3; 151 | <0.001 | 0.295 |

| Glycemic parameters | ||||||||||||

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 88.0 (21.0) | 205 | 88.7 (13.7) | 199 | 89.9 (13.7) | 193 | 92.3 (14.1) | 200 | 2.9 | 3; 177 | 0.037 | 0.048 |

| HOMA index | 1.9 (2.2) | 157 | 2.2 (2.2) | 170 | 2.6 (2.2) | 184 | 3.0 (2.3) | 177 | 6.7 | 3; 97 | <0.001 | 0.177 |

| HOMA index, men | 1.7 (1.5) | 85 | 2.3 (2.6) | 94 | 2.8 (2.6) | 99 | 3.3 (2.7) | 97 | 5.1 | 3; 51 | 0.004 | 0.237 |

| HOMA index, women | 2.2 (2.7) | 72 | 2.1 (1.7) | 76 | 2.3 (1.7) | 85 | 2.8 (1.7) | 80 | 3.5 | 3; 45 | 0.023 | 0.201 |

| Triglyceride/HDLc index | 1.8 (1.1) | 177 | 2.6 (2.6) | 195 | 2.7 (2.7) | 191 | 3.0 (2.3) | 194 | 17.6 | 3; 146 | <0.001 | 0.269 |

| Insulin total (μU/ml) | 9.1 (9.3) | 159 | 9.9 (8.6) | 170 | 11.2 (7.7) | 185 | 12.8 (8.2) | 177 | 5.2 | 3; 100 | 0.002 | 0.139 |

| Insulin men | 8.2 (7.0) | 85 | 9.9 (9.6) | 94 | 11.8 (8.7) | 100 | 13.4 (9.5) | 97 | 4.5 | 3; 53 | 0.007 | 0.213 |

| Insulin women | 10.1 (11.4) | 74 | 9.9 (7.2) | 76 | 10.5 (6.4) | 85 | 12.1 (6.2) | 80 | 3.3 | 3; 47 | 0.030 | 0.183 |

| Hormonal levels | ||||||||||||

| Leptin total (ng/ml) | 8.4 (8.3) | 153 | 13.2 (10.5) | 184 | 13.3 (11.8) | 184 | 21.5 (18.5) | 174 | 35.5 | 3; 106 | <0.001 | 0.508 |

| Leptin men | 4.8 (5.0) | 84 | 8.2 (6.6) | 104 | 8.6 (8.4) | 98 | 13.2 (11.4) | 94 | 17.8 | 3; 58 | <0.001 | 0.492 |

| Leptin women | 12.7 (9.3) | 69 | 19.8 (11.1) | 80 | 18.6 (12.9) | 86 | 31.3 (20.5) | 80 | 21.9 | 3; 48 | <0.001 | 0.595 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; HDL, high density lipoprotein; HOMA, homeostasis model assessment; LDL, low density lipoprotein.

Pillai’s trace statistic F value.

These increments in body weight had a relevant clinical effect; the percentage of obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) among the individuals with psychosis rose from 7 to 36.8% at the end of the 10-year follow-up. The percentage of those meeting criteria for overweight (BMI ≥ 25, <30 kg/m2) also increased, from 23.9 to 36.3%, in the same period, leaving just a mere 26.5% of individuals with normal weight at 10-year follow-up (from 69.9% at baseline).

The maximum increase in weight occurred in the first year of treatment; 58.4% of the total increment in mean weight and 55.6% of the total increment in mean BMI (see Table 2) occurred in the first year. From year 1 to year 3, the weight gain decreased (trend toward statistical significance), reaching again statistical significance in the last 7 years of study period. These data showed a sustained increase in mean weight and BMI following the first year of treatment, with an average increase of 0.7 kg each year (0.35 kg/m2 per year). Leptin plasma levels, as an indicator of adipose mass, followed a similar trajectory to weight change.

Similarly, all lipid and glucose parameters showed a significant increase during the 10-year follow-up. Only HDL cholesterol levels showed a statistical tendency (p = 0.087) to decrease from baseline to the end of the study period (Table 2).

Longitudinal differences in weight and metabolism changes between people with psychosis and healthy controls

Healthy control individuals also present significant increments in mean body weight at 10-year evaluation (Supplementary Table S2). However, when comparing people with psychosis and healthy controls, we observed that over the 10-year follow-up period, the individuals with psychosis presented a significantly worse progression in weight and metabolic measurements (Table 3). For instance, the psychosis group showed a greater increase in mean weight (15.21 vs. 2.89 kg, F = 44.58, p < 0.001) and BMI (5.41 vs. 1.03, F = 42.89, p < 0.001) than the control one.

Table 3.

Differences in longitudinal changes in anthropometric and metabolic measurements between individuals with psychosis and healthy controls after 10 years of follow-up.

| People with FEP | Healthy controls | Stats a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean diff. (SD) | Mean diff. (SD) | df | F | p | |

| Anthropometric measures | |||||

| Weight (kg) | 15.21 (12.63) | 2.89 (7.35) | 1; 254 | 45.61 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 5.41 (4.55) | 1.03 (2.74) | 1; 254 | 43.40 | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 13.63 (11.74) | 4.68 (7.14) | 1; 86 | 16.51 | <0.001 |

| Lipid parameters | |||||

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 21.64 (33.95) | 8.79 (36.52) | 1; 217 | 1.42 | 0.235 |

| HDL (mg/dl) | −1.56 (12.49) | 2.75 (6.86) | 1; 189 | 6.51 | 0.012 |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 13.80 (28.16) | 6.54 (31.45) | 1; 186 | 0.54 | 0.464 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 44.45 (72.75) | −2.75 (52.79) | 1; 189 | 9.53 | 0.002 |

| Glycemic parameters | |||||

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 4.15 (21.68) | 4.42 (16.85) | 1; 216 | 4.48 | 0.036 |

| HOMA index | 1.07 (3.19) | 0.16 (0.87) | 1; 152 | 13.12 | <0.001 |

| HOMA index, men | 1.54 (2.79) | −0.19 (0.93) | 1; 80 | 6.54 | 0.013 |

| HOMA index, women | 0.54 (3.53) | 0.51 (0.67) | 1; 72 | 7.907 | 0.006 |

| Triglycerides-HDL index | 1.13 (2.06) | −0.07 (0.97) | 1; 185 | 8.49 | 0.004 |

| Insulin (μU/ml) | 3.64 (12.29) | 0.19 (3.59) | 1; 155 | 15.609 | <0.001 |

| Insulin, men | 5.15 (10.20) | −0.78 (3.72) | 1; 81 | 8.36 | 0.005 |

| Insulin, women | 1.99 (14.14) | 1.25 (3.27) | 1; 74 | 8.64 | 0.004 |

| Hormonal levels | |||||

| Leptin (ng/ml) | 12.42 (14.55) | 4.66 (4.52) | 1; 150 | 9.92 | 0.002 |

| Leptin, men | 7.78 (10.51) | 3.85 (4.65) | 1; 78 | 3.49 | 0.066 |

| Leptin, women | 17.45 (16.59) | 5.54 (4.39) | 1; 72 | 8.90 | 0.004 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure, HDL, high density lipoprotein; HOMA, homeostasis model assessment; LDL, low density lipoprotein.

Statistics: ANCOVA model: parameter change was used as the dependent variable, participants group (psychosis vs. controls) was the fixed factor and baseline BMI, baseline parameter data, age, and sex were used as covariates.

Incidence of clinically relevant abnormal metabolic measurements after 10 years of psychosis breakout

The percentage of individuals with psychosis meeting criteria for hypertriglyceridemia (>150 mg/dl) and hypercholesterolemia (total cholesterol > 200 mg/dl) increased significantly, from 7.1 to 24.4% (p < 0.001) and from 23.4 to 41.6% (p < 0.001), respectively, during the 10-year study period (Table 4). In the same line, the proportion of FEP patients with clinically elevated LDL cholesterol (>130 mg/dl) rose from 24.2 to 35.2% (p = 0.006). However, no significant changes were observed in the percentage of FEP patients with low HDL cholesterol (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of proportion of FEP participants with pathologic parameters in weight, glycemic, and lipid parameters at baseline and at 10-year follow-up.

| 10 years follow-up | Baseline | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | % (n) | % difference | N | p a | |

| Anthropometric changes | |||||

| Obesity, BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 36.8 (74) | 7.0 (14) | 29.8 | 201 | <0.001 |

| Overweight, BMI ≥ 25,<30 kg/m2 | 36.3 (73) | 23.9 (48) | 12.4 | 201 | 0.011 |

| Glycemic parameters | |||||

| Glucose > 110 mg/dl | 7.1 (14) | 1.5 (3) | 5.6 | 196 | 0.007 |

| Insulin total (μU/ml) | 31.3 (41) | 9.2 (12) | 22.1 | 131 | <0.001 |

| Levels in men > 15.7 | 36.2 (25) | 7.2 (5) | 29.0 | 69 | <0.001 |

| Levels in women > 17.3 | 25.8 (16) | 11.3 (7) | 14.5 | 62 | 0.078 |

| HOMA index | 30.2 (39) | 7.0 (9) | 23.2 | 129 | <0.001 |

| Levels in men > 3.5 | 37.7 (26) | 2.9 (2) | 34.8 | 69 | <0.001 |

| Levels in women > 3.9 | 21.7 (13) | 11.7 (7) | 10.0 | 60 | 0.238 |

| Triglyceride/HDL index > 3.5 | 23.8 (39) | 11.0 (18) | 12.8 | 164 | <0.001 |

| Lipid parameters | |||||

| Cholesterol > 200 mg/dl | 41.6 (82) | 23.4 (46) | 18.2 | 197 | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol > 130 mg/dl | 35.2 (58) | 24.2 (40) | 10.8 | 165 | 0.006 |

| HDL cholesterol < 40 mg/dl | 26.2 (44) | 21.4 (36) | 4.8 | 168 | 0.280 |

| Triglycerides > 150 mg/dl | 24.4 (41) | 7.1 (12) | 17.3 | 168 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; HDL, high density lipoprotein; HOMA, homeostasis model assessment; LDL, low density lipoprotein.

McNemar test for repeated measures.

Significant increments were also observed in the percentage of people with psychosis meeting clinically elevated levels of glucose and insulin, and both HOMA index and TG/HDL ratio, indicating a greater risk for the development of glucose metabolism alterations such as glucose intolerance.

Correlation between long-term weight gain and metabolic changes in FEP

Weight gain was positively correlated with insulin increase (r = 0.48, p < 0.001) and with the insulin resistance indexes, HOMA (r = 0.48, p < 0.001) and triglycerides/HDL (r = 0.51, p < 0.001). A trend toward significance was observed between weight and glucose changes (r = 0.18, p = 0.055). There was also a positive correlation between weight gain and triglycerides increase (r = 0.46, p < 0.001), and a negative correlation between weight gain and HDL changes (r = −0.32, p = 0.001). These associations were significant after controlling for sex, age, and baseline BMI.

A relationship between weight increase and changes in metabolic variables was detected when we compared three groups of individuals with psychosis according to the increase in their BMI (Table 5), where significant differences were observed for insulin, HOMA index and TG/HDL ratio, and triglycerides increments, as well as for HDL cholesterol reductions, between groups.

Table 5.

Changes in glycemic and lipid parameters after 10 years of antipsychotic treatment: comparison of groups with different percentage of weight gain.

| BMI changes (% from baseline) during the 10 year follow-up period | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <7% BMI increase from baseline | 7–19.9% BMI increase from baseline | ≥20% BMI increase from baseline | |||||||

| Mean (IC95%) | Mean (IC95%) | Mean (IC95%) | p b | ||||||

| A: N = 39 | B: N = 60 | C: N = 104 | df | F a | p | A versus B | A versus C | B versus C | |

| Change in glucose parameters | |||||||||

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 1.2 (−6.1, 8.5) | 3.9 (−1.8, 9.6) | 5.3 (0.9, 9.8) | 2; 190 | 0.46 | 0.633 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Insulin total (μU/ml) | 0.3 (−4.2, 4.8) | −1.6 (−5.3, 2.1) | 8.4 (1.5, 11.3) | 2; 129 | 9.94 | <0.001 | 1.000 | 0.012 | <0.001 |

| HOMA index | −0.1 (−1.2, 1.1) | −0.2 (−1.1, 0.7) | 2.3 (1.6, 3.1) | 2; 127 | 10.43 | <0.001 | 1.000 | 0.003 | <0.001 |

| Triglyceride/HDL index | 0.4 (−0.3, 1.1) | 0.2 (−0.4, 0.7) | 2.0 (1.6, 2.4) | 2; 159 | 16.10 | <0.001 | 1.000 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Change in lipid parameters | |||||||||

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 12.4 (1.1, 23.7) | 23.3 (14.3, 32.3) | 24.2 (17.3, 31.2) | 2; 191 | 1.62 | 0.200 | 0.408 | 0.251 | 1.000 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 6.8 (−3.7, 17.3) | 14.0 (5.9, 22.2) | 16.2 (9.9, 22.5) | 2; 160 | 1.11 | 0.330 | 0.850 | 0.415 | 1.000 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 1.1 (−3.3, 5.4) | 3.6 (0.2, 7.0) | −5.4 (−8.0, −2.8) | 2; 163 | 9.20 | <0.001 | 1.000 | 0.040 | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 17.5 (−6.7, 41.7) | 14.7 (−4.9, 34.3) | 72.3 (57.3, 87.3) | 2; 163 | 13.16 | <0.001 | 1.000 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; HDL, high density lipoprotein; HOMA, homeostasis model assessment; LDL, low density lipoprotein.

ANCOVA model: parameter change was used as the dependent variable, weight gain group was the fixed factor, and baseline BMI, age, and sex were used as covariates.

Pairwise comparisons based on estimated marginal means; Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Secondary analyses: sex differences in weight and metabolic changes in individuals with FEP at longer term (10 years)

Women with psychosis presented a significantly greater increment in BMI (6 vs. 4.9, F = 4.18, p = 0.042) and leptin levels (17.45 vs. 7.78, F = 23.29, p < 0.001) than men (Supplementary Table S1). On the contrary, men presented a worse evolution in glucose (5.65 vs. 2.32, F = 8.00, p = 0.005) and HDL measurements (−1.77 vs. −1.32, F = 4.01, p = 0.045) than women. No other significant differences were observed in long-term metabolic variables changes regarding sex.

Secondary analyses: prediction factors of weight increase at 10-year follow-up

A cumulative odds ordinal logistic regression with proportional odds was run to determine the effect of sex, age, DUP, treatment discontinuation, weight gained at 1 year, HOMA index, leptin, triglycerides, LDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol at baseline on weight gain at 10 years.

According to the logistic regression results, the assumption of proportional odds was met, as assessed by a full likelihood ratio test comparing the fit of the proportional odds model to a model with varying location parameters, χ2(8) = 10.079, p = 0.344. The Pearson goodness-of-fit test indicated that the model was a good fit to the observed data (χ2(226) = 247,756, p = 1.096).

Among the variables within the model, DUP had a statistically significant effect on the prediction of whether there is a weight increase greater than 20% (Wald χ 2(1) = 4.928, p = 0.026). In the same direction, the first year weight increase percentage had a statistically significant effect on the prediction of whether there is a weight increase greater than 20% at 10 years (Wald χ 2(1) = 16.189, p < 0.001). And the odds ratio of being in a higher category of the dependent variable (weight increase ≥ 20%) for men versus women was 3.178 (95% CI, 1.137–8.85), a statistically significant effect (χ 2(1) =4.858, p = 0.028). On the contrary, the odds of people with psychosis, having discontinued antipsychotic treatment, to have a weight increase greater than 20% at 10 years was 0.266 (95% CI, 0.096–0.737) times that those that continued taking antipsychotics, a statistically significant effect (χ 2(1) = 6.473, p = 0.011).

Discussion

Long-term weight differences

This study provides evidence, through a prospective methodology, of a significant increment in body weight and BMI at longer term (10 years) in people with FEP. Thus, the participants with FEP in this study presented, after their first 10 years of follow-up, an average increment of 15 kg in body weight. These results are in line with previous prospective studies on FEPs patients [6, 7, 14, 26] reporting continuous increments in mean body weight and BMI at long term (1 and 3 years). Based mainly on indirect data from transversal and retrospective studies on patients with chronic psychosis [8, 10–13], we can determine that this weight increment is also present after longer periods of antipsychotic exposure (10 years). Besides, a unique prospective study on the weight progression at longer periods [27], describing the 20-year BMI progression of 146 patients after their first hospital admission due to psychosis, reported a high prevalence of obesity among patients with schizophrenia at longer term, reaching 50% at 10 years and 62.1% at the 20-year follow-up.

Interestingly, we observed significant differences in the weight change presented at 10-year follow-up between FEP patients and healthy controls; participants in the control group also presented significant increments in body weight (Δ3.4 kg) and BMI (Δ1 kg/m2), but these were significantly smaller than that observed in the psychosis group. Moreover, the rate of obesity among the control group at 10-year follow-up (15.8%) was comparable to the prevalence in the Spanish general population (ranging from 14.5 to 18.0%) [28]. In contrast, the rate of obesity among the FEP group at 10-year follow-up was 36.8%, clearly above that observed in the control group and in the Spanish general population.

Clinical impact of developing obesity

Developing obesity is in itself of clinical relevance. Obese individuals present a higher all-cause excess mortality, compared with people with normal weight [29]. Moreover, presenting obesity, even without other metabolic disorders, increases the odds for a negative prognosis; metabolically healthy obese individuals are at higher risk of developing metabolic risk factors and events than nonobese persons [30]. In relation with these and previous studies [6, 7, 14], we observed that gaining weight correlated with undesirable changes in lipid and glycemic measurements in FEP patients. At long term, the progressive worsening in the biochemical levels had a clinical manifestation in the significant increase in the percentage of participants meeting criteria for obesity and metabolic disorders.

Our results showed a significant increment, in the 10-year follow-up, in the proportion of FEP patients presenting abnormal glucose metabolism measurements, including insulin resistance indexes, glucose, and insulin levels. Moreover, the mean increments after 10 years in HOMA index, TG/HDL ratio, and insulin level were significantly greater among FEP patients than in healthy controls. This poorer outcome in glucose metabolism among patients with psychosis could be in part explained by the antipsychotic exposure and other risk factors usually present in this vulnerable population. However, previous studies have suggested that individuals with psychosis may be at greater risk of presenting abnormal glucose metabolism even before the onset of psychosis [31, 32]. This probable inherent risk could be due to genetic differences; thus, it has been described an association between insulin resistance and polygenic risk score in antipsychotic naive patients [33] and other biomarkers [34], and insulin resistance in unaffected siblings of psychosis patients [35].

Despite of this and the results regarding abnormal glucose metabolism in our sample, only five individuals had a recorded diagnosis of type II diabetes mellitus at the 10-year follow-up and were prescribed oral anti-diabetic drugs. Similarly, only six persons among the psychosis group had a diagnosis of dyslipidemia and were on pharmacological treatment.

Importance of rapid developing weight gain in psychosis

The study shows that, according to previous reports [7, 36], the first year after initiating the antipsychotic treatment is the critical one, in which most of the weight gain occurs; up to 60% of the total weight gain observed at 10 years, occurred in the first year. People with psychosis in our study presented a rapid increase in body weight during the first year of treatment, which was followed by a slower but constant increase of body weight throughout the 10-year follow-up. This initial and rapid increase in body weight during the first year predicted a critical weight gain (greater than 20% from baseline) after 10 years of follow-up. This association is in line with previous studies; Vandenberghe et al. [37, 38] reported that early antipsychotic-induced weight changes predict long-term weight gain, both in adults and adolescents with psychiatric conditions. Besides, both rapid weight gain and steady increase trajectories, such as the pattern described in our study, have been associated with higher risk of mortality. Thus, weight stability has been associated with a lower mortality [39, 40], while steady weight gainers presented a higher mortality [39, 40]. Besides, obese patients with trajectories of weight increments were at higher risk of excess mortality [42]. These evidences highlight the relevancy of BMI trajectories versus status.

Sex differences in weight changes

We identified sex differences, where women presented a significantly greater increase in BMI and leptin levels than men, after 10-year follow-up. Sex differences in the metabolic effect of antipsychotics have been previously described [43, 44], usually indicating a greater risk of weight gain for women. Several studies carried out transversally in patients with chronic schizophrenia and long-term exposure to antipsychotic medication showed that women presented greater weight and BMI and higher rates of obesity [43, 45–46], as well as worse measures of abdominal obesity (i.e., waist circumference and waist-hip ratio) [46], than men. However, these sex differences in antipsychotic-induced weight gain have not been consistently reported in people with FEP, with contrary results at long term [14, 27, 36]. It has been suggested that these contrary results may be due to specificity to antipsychotic treatments [14, 48].

Besides, our results showed that men were at higher risk than women of presenting high increase of body weight (≥20% from baseline) at 10-year follow-up. Other variables predicting this high increase in body weight were a higher weight gain during the first year after the FEP and antipsychotic treatment continuation, in line with previous studies by our group [7, 49]. However, a longer DUP also predicted a greater weight increase at long term. DUP has been widely associated with a greater severity of psychotic symptoms at presentation [50] and to poorer outcomes of psychosis [51], and long DUP correlates with long duration of prodromal symptoms and with poorer social support and functioning [52]. In this sense, a long DUP could indirectly determine difficulties in self-care and in the access to professional care, which could ultimately lead to poorer physical health conditions, such as metabolic syndrome [53] or glucose intolerance [31], described at baseline in drug-naïve FEP patients. However, this increased risk of metabolic alterations in drug-naïve FEP patients could not be attributed to the DUP [54]. On the other hand, no previous studies have explored the effect of DUP on weight changes in FEP, limiting the possibility of comparing our results to previous literature.

The study presents several limitations. The results may be affected by sample selection bias considering recruitment was limited to individuals agreeing to participate after having been re-contacted for a 10-year follow-up. A small group of participants (patients n = 5, 2.4%; controls n = 3, 5.3%) were under 18 at study entry, and they had probably grown and got taller during the first 3 years of the study. Unfortunately, we do not have a second measure of height within the first 3 years of study, and therefore we have used their baseline height for the 1-year and 3-year follow-ups BMI calculation (Table 2). Although these individuals present small mean height increment after 10 years (from baseline 170.8 cm (SD 7.6) to 10 year 172.9 cm (SD 7.1)), this could have partially affected the results of BMI change (Table 2). Patients were not evaluated for research purposes between year 3 and year 10, thus leading to a widely spaced follow-up interval with a lack of clinical, biometric and social information, which precluded proper analyses of weight trajectories. Data were not available on some relevant variables that affect weight (e.g., diet and physical activity) [55, 56]. Dietary and healthy lifestyle counseling was delivered as clinical routine following clinicians’ discretion but was not recorded for research purposes. The clinical repercussion related to weight gain, such as glucose intolerance, type 2 diabetes, or dyslipidemia, was not rigorously explored in our study since the diagnosis of these conditions requires at least two separate abnormal measurements [57, 58]. Finally, instead of stratifying patients by weight gain over time, future works should use cardiometabolic risk calculations, as the proposed by Perry et al. [59] for FEP.

The main strength of this study is its design; a prospective longitudinal study with an uncommon long-term follow-up (10 years), on a cohort of well-characterized individuals with FEP, and its comparison with a prospective group of healthy subjects. Besides, studying a cohort of drug-naïve (at baseline) patients with a FEP facilitates avoiding the confounding effect of chronicity and previous exposure to medications with a probable effect on metabolism.

In summary, people with a FEP experienced, at long term (10 years), a significantly greater increase in BMI than healthy controls. Significant differences were also observed in mean changes in metabolic measurements, leading to significant increments in the proportion of FEP participants with obesity and metabolic disturbances. Participants gained most of the weight in the first year after their FEP, although they continued gaining weight steadily throughout the 10-year follow-up.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank all “Programa Asistencial de las Fases Iniciales de Psicosis” (PAFIP) research team and all patients and family members who participated in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data of this study are accessible and have been deposited in a publicly available repository (Mendeley Data: http://doi.org/10.17632/b2h5gr9m3c.1).

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2022.2308.

click here to view supplementary material

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: J.V-B., B.C-F.; Formal analysis: J.V-B., V.O-G., D.T-G.; Funding acquisition: J.V-B., B.C-F.; Investigation: M.G-R., J.M-vS., E.S-S., R.A-A., D.T-G., M.J-R., B.C-F.; Methodology: J.V-B., J.M-vS., V.O-G., R.A-A., D.T-G., B.C-F.; Project administration: V.O-G.; Resources: J.V-B., M.G-R., V.O-G., B.C-F.; Supervision: B.C-F.; Writing—original draft: J.V-B.; Writing—review and editing: J.V-B., M.G-R., J.M-vS., V.O-G., E.S-S., R.A-A., D.T-G., M.J-R., J.L, B.C-F.

Financial Support

This study was supported by the Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Valdecilla (J.V-B., grant numbers INT/A21/10, INT/A20/04, NEXTVAL17/24; and Instituto de Salud Carlos III (B.C-F., grant numbers PI020499, PI050427, PI060507).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare none.

References

- [1].Hjorthoj C, Sturup AE, McGrath JJ, Nordentoft M. Years of potential life lost and life expectancy in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiat.2017;4(4):295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Tiihonen J, Lonnqvist J, Wahlbeck K, Klaukka T, Niskanen L, Tanskanen A, et al. 11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study (FIN11 study). Lancet. 2009;374(9690):620–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].DEH M, Correll CU, Bobes J, Cetkovich-Bakmas M, Cohen D, Asai I, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. 2011;10(1):52–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Melle I, Olav Johannesen J, Haahr UH, Ten Velden Hegelstad W, Joa I, Langeveld J, et al. Causes and predictors of premature death in first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(2):217–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Foley DL, Morley KI. Systematic review of early cardiometabolic outcomes of the first treated episode of psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(6):609–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Perez-Iglesias R, Mata I, Pelayo-Teran JM, Amado JA, Garcia-Unzueta MT, Berja A, et al. Glucose and lipid disturbances after 1 year of antipsychotic treatment in a drug-naive population. Schizophr Res. 2009;107(2–3):115–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Perez-Iglesias R, Martinez-Garcia O, Pardo-Garcia G, Amado JA, Garcia-Unzueta MT, Tabares-Seisdedos R, et al. Course of weight gain and metabolic abnormalities in first treated episode of psychosis: the first year is a critical period for development of cardiovascular risk factors. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17(1):41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mackin P, Waton T, Watkinson HM, Gallagher P. A four-year naturalistic prospective study of cardiometabolic disease in antipsychotic-treated patients. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27(1):50–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Saloojee S, Burns JK, Motala AA. Metabolic syndrome in South African patients with severe mental illness: prevalence and associated risk factors. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0149209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Seow LS, Chong SA, Wang P, Shafie S, Ong HL, Subramaniam M. Metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk among institutionalized patients with schizophrenia receiving long term tertiary care. Compr Psychiatry. 2017;74:196–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gardner-Sood P, Lally J, Smith S, Atakan Z, Ismail K, Greenwood KE, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and metabolic syndrome in people with established psychotic illnesses: baseline data from the IMPaCT randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2015;45(12):2619–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bobes J, Arango C, Aranda P, Carmena R, Garcia-Garcia M, Rejas J. Cardiovascular and metabolic risk in outpatients with schizoaffective disorder treated with antipsychotics: results from the CLAMORS study. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27(4):267–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Henderson DC, Nguyen DD, Copeland PM, Hayden DL, Borba CP, Louie PM, et al. Clozapine, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and cardiovascular risks and mortality: results of a 10-year naturalistic study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(9):1116–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Vazquez-Bourgon J, Perez-Iglesias R, Ortiz-Garcia de la Foz V, Suarez Pinilla P, Diaz Martinez A, Crespo-Facorro B. Long-term metabolic effects of aripiprazole, ziprasidone and quetiapine: a pragmatic clinical trial in drug-naive patients with a first-episode of non-affective psychosis. Psychopharmacology. 2018;235(1):245–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pillinger T, McCutcheon RA, Vano L, Mizuno Y, Arumuham A, Hindley G, et al. Comparative effects of 18 antipsychotics on metabolic function in patients with schizophrenia, predictors of metabolic dysregulation, and association with psychopathology: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiat. 2020;7(1):64–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ayesa-Arriola R, Ortiz-Garcia de la Foz V, Martinez-Garcia O, Setien-Suero E, Ramirez ML, Suarez-Pinilla P, et al. Dissecting the functional outcomes of first episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a 10-year follow-up study in the PAFIP cohort - CORRIGENDUM. Psychol Med. 2021;51:264–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Pelayo-Teran JM, Perez-Iglesias R, Ramirez-Bonilla M, Gonzalez-Blanch C, Martinez-Garcia O, Pardo-Garcia G, et al. Epidemiological factors associated with treated incidence of first-episode non-affective psychosis in Cantabria: insights from the clinical programme on early phases of psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2008;2(3):178–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders. In: Clinician version (SCID-CV), Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Andreasen N. Scale for the assessment of negative symptoms (SANS). Iowa: University of Iowa; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Andreasen NC. Scale for the assessment of positive symptoms (SAPS). Iowa: Iowa University; 1984, p. 173–80. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Flemenbaum A, Zimmermann RL. Inter- and intra-rater reliability of the brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychol Rep. 1973;32(3):783–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. 1985. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and betacell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in ma. Diabetologia 28 (7), 412–419. PMID: 3899825 DOI: 10.1007/BF00280883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18(6):499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].McLaughlin T, Reaven G, Abbasi F, Lamendola C, Saad M, Waters D, et al. Is there a simple way to identify insulin-resistant individuals at increased risk of cardiovascular disease? Am J Cardiol. 2005;96(3):399–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sachs GS, Guille C. Weight gain associated with use of psychotropic medications. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(Suppl 21):16–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Fleischhacker WW, Siu CO, Boden R, Pappadopulos E, Karayal ON, Kahn RS. Metabolic risk factors in first-episode schizophrenia: baseline prevalence and course analysed from the European first-episode schizophrenia trial. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16(5):987–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Strassnig M, Kotov R, Cornaccio D, Fochtmann L, Harvey PD, Bromet EJ. Twenty-year progression of body mass index in a county-wide cohort of people with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder identified at their first episode of psychosis. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19(5):336–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Encuesta Nacional de Salud 2017. [Internet]. Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social, Gobierno de España, http://www.ine.es/jaxi/Tabla.htm?path=/t00/mujeres_hombres/tablas_1/l0/&file=d06001.px&L=0; 2017 [accessed 07 December 2021].

- [29].Flegal KM, Kit BK, Orpana H, Graubard BI. Association of all-cause mortality with overweight and obesity using standard body mass index categories: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2013;309(1):71–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Johnson W, Bell JA, Robson E, Norris T, Kivimaki M, Hamer M. Do worse baseline risk factors explain the association of healthy obesity with increased mortality risk? Whitehall II study. Int J Obes. 2019;43(8):1578–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Pillinger T, Beck K, Gobjila C, Donocik JG, Jauhar S, Howes OD. Impaired glucose homeostasis in first-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiat. 2017;74(3):261–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Greenhalgh AM, Gonzalez-Blanco L, Garcia-Rizo C, Fernandez-Egea E, Miller B, Arroyo MB, et al. Meta-analysis of glucose tolerance, insulin, and insulin resistance in antipsychotic-naive patients with nonaffective psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2017;179:57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Tomasik J, Lago SG, Vazquez-Bourgon J, Papiol S, Suarez-Pinilla P, Crespo-Facorro B, et al. Association of insulin resistance with schizophrenia polygenic risk score and response to antipsychotic treatment. JAMA Psychiat. 2019;76(8):864–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lago SG, Tomasik J, van Rees GF, Rubey M, Gonzalez-Vioque E, Ramsey JM, et al. Exploring cellular markers of metabolic syndrome in peripheral blood mononuclear cells across the neuropsychiatric spectrum. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;91:673–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Chouinard VA, Henderson DC, Dalla Man C, Valeri L, Gray BE, Ryan KP, et al. Impaired insulin signaling in unaffected siblings and patients with first-episode psychosis. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(10):1513–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Bioque M, Garcia-Portilla MAP, Garcia-Rizo C, Cabrera B, Lobo A, Gonzalez-Pinto A, et al. Evolution of metabolic risk factors over a two-year period in a cohort of first episodes of psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2018;193:188–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Vandenberghe F, Gholam-Rezaee M, Saigi-Morgui N, Delacretaz A, Choong E, Solida-Tozzi A, et al. Importance of early weight changes to predict long-term weight gain during psychotropic drug treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(11):e1417–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Vandenberghe F, Najar-Giroud A, Holzer L, Conus P, Eap CB, Ambresin AE. Second-generation antipsychotics in adolescent psychiatric patients: metabolic effects and impact of an early weight change to predict longer term weight gain. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2018;28(4):258–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Peter RS, Keller F, Klenk J, Concin H, Nagel G. Body mass trajectories, diabetes mellitus, and mortality in a large cohort of Austrian adults. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(49):e5608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Klenk J, Rapp K, Ulmer H, Concin H, Nagel G. Changes of body mass index in relation to mortality: results of a cohort of 42,099 adults. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e84817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Wang M, Yi Y, Roebothan B, Colbourne J, Maddalena V, Sun G, et al. Trajectories of body mass index among Canadian seniors and associated mortality risk. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Zheng H, Tumin D, Qian Z. Obesity and mortality risk: new findings from body mass index trajectories. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(11):1591–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Li Q, Chen D, Liu T, Walss-Bass C, de Quevedo JL, Soares JC, et al. Sex differences in body mass index and obesity in Chinese patients with chronic schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;36(6):643–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lee SY, Park MH, Patkar AA, Pae CU. A retrospective comparison of BMI changes and the potential risk factors among schizophrenic inpatients treated with aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine or risperidone. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35(2):490–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Yang F, Wang K, Du X, Deng H, Wu HE, Yin G, et al. Sex difference in the association of body mass index and BDNF levels in Chinese patients with chronic schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology. 2019;236(2):753–62. PMID: 30456540 DOI: 10.1007/s00213-018-5107-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kraal AZ, Ward KM, Ellingrod VL. Sex differences in antipsychotic related metabolic functioning in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2017;47(2):8–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Gebhardt S, Haberhausen M, Heinzel-Gutenbrunner M, Gebhardt N, Remschmidt H, Krieg JC, et al. Antipsychotic-induced body weight gain: predictors and a systematic categorization of the long-term weight course. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43(6):620–6. PMID: 19110264 DOI: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Alberich S, Fernandez-Sevillano J, Gonzalez-Ortega I, Usall J, Saenz M, Gonzalez-Fraile E, et al. A systematic review of sex-based differences in effectiveness and adverse effects of clozapine. Psychiatry Res. 2019;280:112506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Vazquez-Bourgon J, Mayoral-van Son J, Gomez-Revuelta M, Juncal-Ruiz M, Ortiz-Garcia de la Foz V, Tordesillas-Gutierrez D, et al. Treatment discontinuation impact on long-term (10-year) weight gain and lipid metabolism in first-episode psychosis: results from the PAFIP-10 cohort. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;24(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Melle I, Larsen TK, Haahr U, Friis S, Johannessen JO, Opjordsmoen S, et al. Reducing the duration of untreated first-episode psychosis: effects on clinical presentation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(2):143–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Marshall M, Lewis S, Lockwood A, Drake R, Jones P, Croudace T. Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode patients: a systematic review. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(9):975–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kalla O, Aaltonen J, Wahlstrom J, Lehtinen V, Garcia Cabeza I, Gonzalez de Chavez M. Duration of untreated psychosis and its correlates in first-episode psychosis in Finland and Spain. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106(4):265–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Garrido-Torres N, Rocha-Gonzalez I, Alameda L, Rodriguez-Gangoso A, Vilches A, Canal-Rivero M, et al. Metabolic syndrome in antipsychotic-naive patients with first-episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2021;51(14):2307–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Kirkpatrick B, Miller BJ, Garcia-Rizo C, Fernandez-Egea E, Bernardo M. Is abnormal glucose tolerance in antipsychotic-naive patients with nonaffective psychosis confounded by poor health habits? Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(2):280–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Vancampfort D, Firth J, Schuch FB, Rosenbaum S, Mugisha J, Hallgren M, et al. Sedentary behavior and physical activity levels in people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):308–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Firth J, Stubbs B, Teasdale SB, Ward PB, Veronese N, Shivappa N, et al. Diet as a hot topic in psychiatry: a population-scale study of nutritional intake and inflammatory potential in severe mental illness. World Psychiatry. 2018;17(3):365–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Siu AL. Screening for high blood pressure in adults: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(10):778–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].American_Diabetes_Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical Care in Diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Suppl 1):S13–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Perry BI, Osimo EF, Upthegrove R, Mallikarjun PK, Yorke J, Stochl J, et al. Development and external validation of the psychosis metabolic risk calculator (PsyMetRiC): a cardiometabolic risk prediction algorithm for young people with psychosis. Lancet Psychiat. 2021;8(7):589–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2022.2308.

click here to view supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

Raw data of this study are accessible and have been deposited in a publicly available repository (Mendeley Data: http://doi.org/10.17632/b2h5gr9m3c.1).