Abstract

Background

Plastomes of heterotrophic plants have been greatly altered in structure and gene content, owing to the relaxation of selection on photosynthesis-related genes. The orchid tribe Gastrodieae is the largest and probably the oldest mycoheterotrophic clade of the extant family Orchidaceae. To characterize plastome evolution across members of this key important mycoheterotrophic lineage, we sequenced and analyzed the plastomes of eleven Gastrodieae members, including representative species of two genera, as well as members of the sister group Nervilieae.

Results

The plastomes of Gastrodieae members contain 20 protein-coding, four rRNA and five tRNA genes. Evolutionary analysis indicated that all rrn genes were transferred laterally and together, forming an rrn block in the plastomes of Gastrodieae. The plastome GC content of Gastrodia species ranged from 23.10% (G. flexistyla) to 25.79% (G. javanica). The plastome of Didymoplexis pallens contains two copies each of ycf1 and ycf2. The synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution rates were very high in the plastomes of Gastrodieae among mycoheterotrophic species in Orchidaceae and varied between genes.

Conclusions

The plastomes of Gastrodieae are greatly reduced and characterized by low GC content, rrn block formation, lineage-specific reconfiguration and gene content, which might be positively selected. Overall, the plastomes of Gastrodieae not only serve as an excellent model for illustrating the evolution of plastomes but also provide new insights into plastome evolution in parasitic plants.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12870-022-03836-x.

Keywords: Gastrodieae, Didymoplexis, Plastomes, GC contents, ycf1, Substitution rates

Background

Plant cells possess two semiautonomous organelles, plastids and mitochondria, both of which have evolved by endosymbiosis [1, 2]. Plastid genomes (plastomes) of photosynthetic higher plants possess conserved gene contents, with approximately 130 genes encoding approximately 80 proteins, 30 tRNAs, and four rRNAs [3, 4]. The plastomes of photosynthetic higher plants exhibit a conserved structure, characterized by a large single-copy (LSC) region, a small single-copy (SSC) region and two large inverted repeat (IR) regions, which separate the LSC and SSC [3, 5, 6]. In nonphotosynthetic plants (heterotrophic plants), plastomes have been greatly altered in structure and gene content because of the relaxed selection pressure on photosynthesis-related genes, thus providing a unique opportunity for exploring genome evolution under relaxed selection [3, 7–10]. Gene pseudogenization, gene loss and elevated substitution rates are the general trends of plastome degradation in heterotrophic plants [11–13]. The process of plastome degradation, proposed and revised previously, includes the following steps: (1) degradation of photosynthesis and photosynthesis-related genes; (2) degradation of atp and housekeeping genes; and (3) nearly complete or complete loss of the plastid genome [10, 12, 14]. Since its publication, this evolutionary model of plastome degradation in parasitic plants has been supported by subsequent studies [10, 12, 14–23].

Mycoheterotrophs are heterotrophic plants that depend on fungi for nutrients and have evolved at least 47 times in land plants [24]. The orchid tribe Gastrodieae is probably the oldest and potentially the largest mycoheterotrophic lineage of the extant Orchidaceae even in land plants, with approximately 100 species [25–34]. Molecular dating indicates that Gastrodieae evolved approximately 35–38 million years ago (Mya) [28, 31], and is possibly one of the oldest groups of mycoheterotrophs in angiosperms [28, 31, 35]. Like most Orchidaceae species, Gastrodieae seeds totally depend on fungal nutrients for germination, but in Gastrodieae and all mycoheterotrophs, this dependence continues throughout their life cycle [10, 20, 36]. One member of Gastrodieae, Gastrodia elata, has a long history of use in traditional Chinese medicine [37]. Gastrodia elata was successfully cultivated in the 1970s in China and its plant- mycorrhizal interactions, phytochemistry, and medical applications have been intensively studied [38]. The mycoheterotrophic system of Gastrodieae lineage offers a promising model to illustrate the coevolution of mycoheterotrophic plants and their symbiotic microbionts.

Recently, the genomes of two Gastrodieae members, Gastrodia elata and G. menghaiensis, have been sequenced and published [36, 39, 40]. Jiang et al. (2022) reported that the plastomes of Gastrodia species have been greatly degraded with the expansion of some nuclear genes encoding plastid proteins, suggesting that plastids play an important role in fully mycoheterotrophic plants [40]. However, little is known about the pattern and mechanism of plastome evolution in this key important lineage. To characterize plastome evolution in this ancient mycoheterotrophic group, we sequenced and analyzed the plastomes of ten Gastrodieae members together with those of its sister group Nervilieae.

Results

Molecular systematics of Gastrodieae

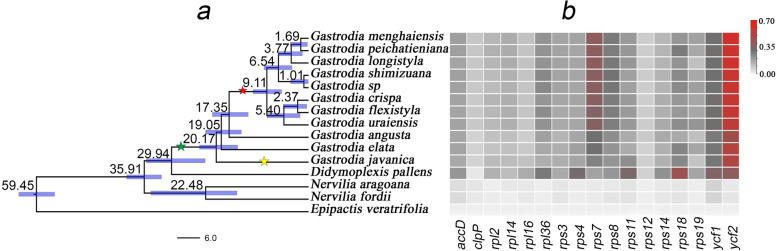

Nervilieae is sister tribe to Gastrodieae, which is strongly supported by plastome-based phylogenies (Fig. S1). The genus Didymoplexis is sister to the genus Gastrodia, with high support, and diverged from Gastrodia approximately 29 million years ago (Mya)(Fig. 1a; Supplementary Fig. S1a). Three Gastrodia species, including G. javanica, G. elata, and G. angusta, were identified, with high support, as successive sister species to the remaining eight Gastrodia species investigated in this study (Fig. 1a). Gastrodia javanica, G. elata, and G. angusta diverged from the backbone of Gastrodia approximately 20, 19, and 17 Mya, respectively, while the remaining eight species formed a tropical clade, which radiated ca. 9 Mya (Fig. 1a). Additionally, G. javanica, G. elata, and G. angusta were characterized by the lack of roots and well-developed tubers and corms, whereas the remaining eight species were characterized by well-developed roots and small black tubers and corms [26, 27, 41].

Fig. 1.

Chronogram and heatmap of nonsynonymous substitution rates (dN) in protein-coding genes. a Time-calibrated tree of Gastrodieae. Green star indicates the loss of IR; yellow star indicates the loss of matK and trnW-CCA; red star indicates the loss of matK. b Heatmap of dN for each plastid protein-coding gene. Gray and red colors indicate low and high dN values, respectively

Size, gene content, and GC content of Gastrodieae plastomes

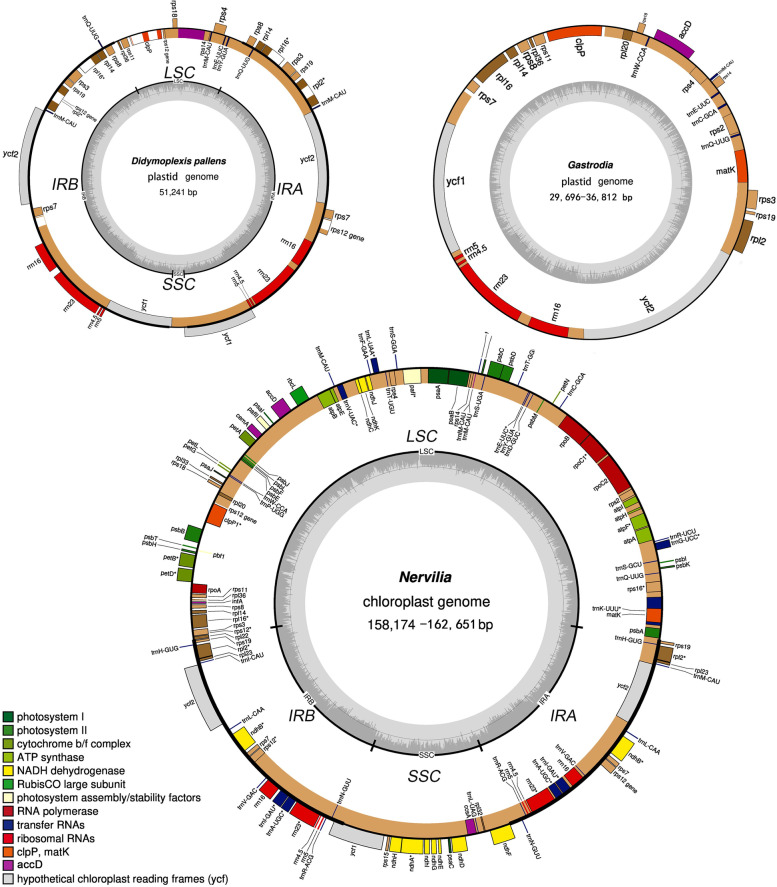

DNA sequencing and assembly revealed that the plastomes of two autotrophic Nervilia species (Nervilieae, Orchidaceae) are 15,8174 and 16,2651 bp in size (Fig. 2), while those of species belonging to Gastrodieae varied in length, ranging from 29,696 bp in Gastrodia peichatieniana to 51,241 bp in Didymoplexis pallens (Table 1, Fig. 2). All Gastrodia species showed similar sized plastomes, ranging from 29,696 bp in G. peichatieniana to 36,812 bp in G. angusta. The plastomes of all Gastrodieae members contained 20 protein-coding genes, four rRNA genes, and five tRNA genes (Table 1). Six housekeeping genes, including rpl22, rpl23, rpl32, rpl33, rps15, and rps16, appeared to be lost from all Gastrodieae plastomes. The housekeeping gene matK was absent from the plastomes of most Gastrodieae members, except G. angusta and G. elata. Additionally, genes such as clpP, rpl2, and rpl16 often contain shorter introns in Gastrodieae plastomes than in Nervilieae plastomes (Supplementary Fig. S2). The trnW-CCA gene was lost from the basal branch of Gastrodia, G. javanica, but was present in remaining members of Gastrodieae, such as G. elata, although the trnW-CCA gene in Gastrodieae members was approximately 16 bp shorter than its counterpart in Nervilia species. The rrn4.5 gene in Gastrodieae plastomes contained two 30 bp AT-rich insertions. Secondary structure analyses indicated that this 4.5S rRNA has an altered structure (Supplementary Fig. S3). The plastome of D. pallens contained two copies each of ycf1 and ycf2.

Fig. 2.

Plastid genomes of Gastrodieae and Nervilia species

Table 1.

Plastid genomes of Gastrodieae and Nervilieae

| Species | Length (bp) | GC content (%) | Voucher | GenBank accession (NCBI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | LSC | SSC | IR | ||||

| Didymoplexis pallens | 51,241 | 7,189 | 3,061 | 20,495 | 34.8 | Jin X. H. 23332(PE) | ON515488 |

| Gastrodia angusta | 36,812 | 25.4 | Jin X. H. 17853 (PE) | ON515479 | |||

| Gastrodia crispa | 30,582 | 25.7 | Jin X. H. & Arief H. PE-BO 4014 (PE) | ON515481 | |||

| Gastrodia elata | 35,304 | 25.3 | Jin X. H. 17638(PE) | MF163256 | |||

| Gastrodia flexistyla | 30,797 | 25.4 | Huang Y.S. QY20190302001(IBK) | ON515480 | |||

| Gastrodia javanica | 31,896 | 24.8 | PE-BO 4091 (PE) | ON515482 | |||

| Gastrodia longistyla | 30,464 | 26.8 | Jin X. H. 25023 (PE) | ON515483 | |||

| Gastrodia menghaiensis | 30,158 | 26.8 | Jin X. H. 18195 (PE) | ON515489 | |||

| Gastrodia peichatieniana | 29,696 | 25.9 | Jin X. H. 31639 (PE) | ON515484 | |||

| Gastrodia shimizuana | 30,019 | 25.5 | Huang Y.S. QY20190226001 (IBK) | ON515485 | |||

| Gastrodia sp. (near Gastrodia crispa) | 29,944 | 25.8 | Jin X. H. 38054 (PE) | ON515486 | |||

| Gastrodia uraiensis | 30,746 | 24.9 | QY1007 (IBK) | ON515487 | |||

| Nervilia aragoana | 162,651 | 91,150 | 18,603 | 26,449 | 36.7 | Jin X. H. 23240 (PE) | ON515490 |

| Nervilia fordii | 158,174 | 86,875 | 18,079 | 26,610 | 36.8 | Jin X. H. 23386 (PE) | ON515491 |

The plastomes of autotrophic Nervilia species showed a typical quadripartite structure (Fig. 2). On the other hand, the plastomes of Gastrodia species showed a specialized structure with only one IR region (Fig. 2). All rrn genes joined together to form the rrn block in plastomes; rpl and rps genes formed the rpl-rpls block, while the four trn genes and two to three coding sequences (CDSs) were embedded in the rpl-rps block (Fig. 2). The rrn and rpl-rps regions were separated by ycf1 and ycf2. The highly reduced plastome of D. pallens showed a quadripartite structure, with transversion and expansion of IR regions (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. S1b). The IR region was extended to a length of 21 kb and contained rps3, rpl16, rpl14, and rps8 genes. By contrast, the SSC region was reduced to an approximately 3 kb sequence containing no gene. The transversion occurred between rps4 and rps14. Another transversion was observed at a location that coincided with the loss of trnW-CCA in G. javanica plastome (Fig. 1b).

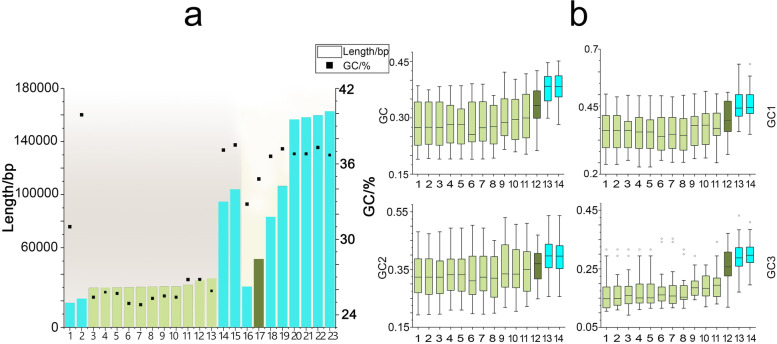

The GC contents of plastomes varied greatly in Gastrodieae and Nervilieae. With total GC contents ranging from 23.10% in G. flexistyla to 25.79% in G. javanica, the average GC content of eleven Gastrodia species was approximately 10% lower than that of autotrophic species, such as Cremastra (Orchidaceae) [22], Holcoglossum (Orchidaceae) [42], N. aragoana, N. fordii and Tipularia (Orchidaceae) [22] (Table 1, Fig. 3a, Supplementary Table S1). However, the GC content of the D. pallens plastome was 34.8%. In the autotrophic Nervilieae species, the GC content was approximately 30% in most CDSs, and up to 44% in genes such as psbA, psbB, and psbC. In Gastrodia species, the GC content was approximately 30% in seven genes, including clpP, rpl2, and rpl14; less than 30% in the remaining 12 CDSs; and less than 20% in ycf1 and ycf2 (Supplementary Tables S2). The GC content of matK was approximately 21% in G. elata and G. angusta, and 30% and 32% in the two Nervilieae species (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). The GC content of the third position of codons (GC3) varied greatly among the three genera investigated in this study: 15–17% in Gastrodia; 25% in D. pallens; and 27% in autotrophic Nervilia species (Table 1, Fig. 3b). Notably, GC3 was less than 10% in rps18 in G. longistyla. Codon usage analysis showed that AAA (encoding Lys) was the most used codon in Gastrodieae, followed by AUA (encoding Ile) and AAU (encoding Asn) (Supplementary Table S3). However, in the autotrophic Nervilieae species, AAU and GAA (encoding Glu) were identified as the two most commonly used codons (Supplementary Table S3).

Fig. 3.

GC content of the plastomes of Gastrodieae and other species. a, Relationships between the length and GC content of plastomes of species. Gastrodieae species, green colour. Gastrodia species, light green. Didymoplexis pallens, dark green. Other species, blue colour. 1: Epipogium roseum; 2: Sciaphila densiflora; 3: Gastrodia peichatieniana; 4: Gastrodia sp.; 5: Gastrodia shimizuana; 6: Gastrodia menghaiensis; 7: Gastrodia longistyla; 8: Gastrodia crispa; 9: Gastrodia uraiensis; 10: Gastrodia flexistyla; 11: Gastrodia javanica; 12: Gastrodia elata; 13: Gastrodia angusta; 14: Aphyllorchis montana; 15: Petrosavia stellaris; 16: Epipogium aphyllum; 17: Didymoplexis pallens; 18: Neottia acuminata; 19: Neottia camtschatea; 20: Cymbidium bicolor; 21: Nervilia aragoana; 22: Epipactis veratrifolia; 23: Nervilia fordii. b Overall GC content and GC content of the first, second, and third positions of codons (GC1, GC2, and GC3, respectively) in the plastomes of various species. 1: Gastrodia menghaiensis; 2: Gastrodia peichatieniana; 3: Gastrodia longistyla; 4: Gastrodia shimizuana; 5: Gastrodia sp.; 6: Gastrodia crispa; 7: Gastrodia flexistyla; 8: Gastrodia uraiensis; 9: Gastrodia angusta; 10: Gastrodia elata; 11: Gastrodia javanica; 12: Didymoplexis pallens; 13: Nervilia aragoana; 14: Nervilia fordii

Molecular evolution of Gastrodieae plastomes

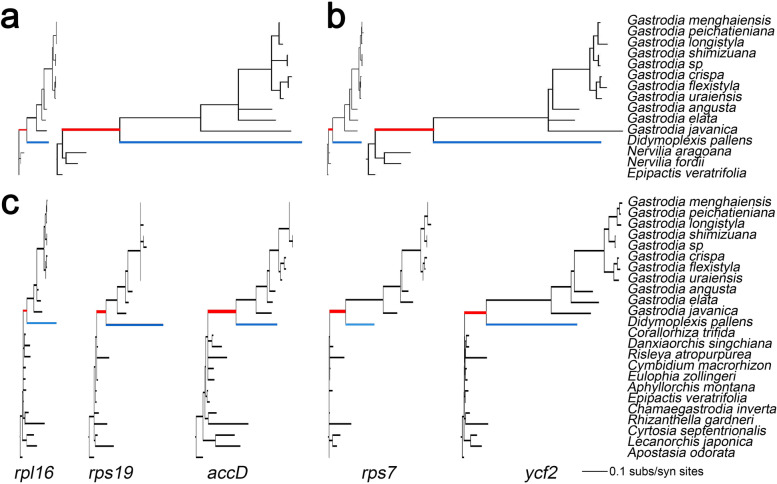

Among the mycoheterotrophic species in Orchidaceae, the Gastrodieae species showed especially high synonymous substitution rate (dS) and nonsynonymous substitution rate (dN) in plastomes (Supplementary Figs. 1, 4, 5; Supplementary Table S4). The values of dN and dS in Gastrodieae plastomes were 8–10 times higher than those in the closely-related autotrophic species Nervilia aragoana and N. fordii (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S4). The values of dN and/or dS varied across species and genes. The value of dS in four genes, including rpl14, rps11, rps18, and ycf1, was very high. However, dS in rpl36 was very low in Gastrodieae and very high in D. pallens. Additionally, the value of dS in four genes (accD, rpl36, rps11, and rps18) was approximately 2–4 times higher in D. pallens than in Gastrodia (Supplementary Fig. S4). Two genes, ycf2 and rps7, showed rather high dN in Gastrodieae, and ycf2 was under positive selection (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. S4, Supplementary Table S5). The value of dN in rps7 was considerably high in Gastrodia but very low in D. pallens. Two genes, clpP and rps12, showed the lowest substitution rates in Gastrodieae (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 4.

Variation in the values of relative and absolute synonymous substitution rates (dS) in plastid protein-coding genes in Gastrodieae. Red and blue branches show the evolution rates of Gastrodieae species and Didymoplexis pallens, respectively. a phylograms of dN and dS of rpl14, respectively. b phyograms of dN and dS of rps3, respectively. The value of dS was approximately 10-fold higher than that of dN. c phylograms of dN divergence of five individual genes. All trees are drawn to the same scale

Based on branch length, the dN and/or dS values changed over time in the various clades. Values of dN in three genes (rpl36, rps7, and rps11) were low in G. angusta but high in its sister group, the tropical Gastrodia clade (Figs. 1 and 4). The dS values in rpl36, rps12, and rps19 were low in G. javanica but high in the remaining Gastrodia species (Supplementary Fig. S4). Values of dN and dS in the majority of remaining housekeeping genes, including accD, clpP, rpl12, rpl14, rps11, rpl16, rpl36, rps3, and rps4, were significantly higher in D. pallens than in other Gastrodieae species (Figs. 1 and 4, Supplementary Figs. S4 and S5). RELAX analyses indicated that two genes, accD and ycf1, were under significant intensification selection (Supplementary Table S6); however, intensification selection pressure on the remaining genes was not significant (Supplementary Table S6). Three genes, ycf1, ycf2, and rps3, were under positive selection in Gastrodieae (Supplementary Table S7).

Discussion

Characteristics such as small size, very low GC content, and loss of many housekeeping genes indicate that the plastomes of Gastrodieae are highly reduced and have reached the stage of a minimal plastome. However, recent analyses of nuclear genes encoding plastid proteins (NEPs) in G. elata and G. menghaiensis indicate that many genes involved in the biosynthesis of essential compounds, such as aromatic amino acids (such as L-tryptophan) and fatty acids, have undergone expansion [40]. These findings suggest that plastids play an important role in fully mycoheterotrophic species, despite the loss of photosynthesis [40]. The loss of housekeeping genes in plastomes and expansion of some NEPs define a paradox, which indicates that plastomes of Gastrodieae may still be in the process of reaching stability. The plastomes of Gastrodieae are an excellent model for illustrating the evolution of plastomes, and provide new insights into plastome evolution in parasitic plants.

The plastomes of Gastrodieae are collinear with those of autotrophic Nervilieae species and other autotrophic orchids (Supplementary Fig. S1b); however, there have been several reconfigurations, including the formation of the rrn block and loss or expansion of the IR regions. The rrn block evolved independently in Epipogium (Orchidaceae) [43], Gastrodieae (Orchidaceae), Rhizanthella (Orchidaceae) [44], and Sciaphila (Triuridaceae) [45]. The convergent evolution of the rrn block in these four distant plant lineages indicates that the rrn block evolved independently and was positively selected. In this study, analysis of the transcriptome data of G. elata downloaded from NCBI (SRR18147619) indicated that at least three blocks, including rrn, clpP-rps11-rpl36-rps8, and rpl14-rpl16, were transcribed together as a single transcript (Supplementary Fig. S6). Jiang et al. (2022) indicated that NEPs of plastid ribosome large subunit underwent expansion [40]. This reconfiguration of plastome structure, transcription pattern of the rrn block, and expansion of NEPs of plastid ribosome large subunit may accelerate ribosome assembly, protein translation and biosynthesis of important compounds. This may be related to the special lifestyle of Gastrodieae. Plants of Gastrodieae species grow underground for approximately 3–4 years. However, following inflorescence emergence from the ground, plants grow rapidly to a height of up to 150 cm and disperse seeds within 1 month, thus requiring support from plastid protein function. The reconfiguration of IR regions is common among parasitic species but shows lineage-specific trends [43, 45]. Two extreme trends of IR reconfiguration were observed in this study: (1) complete loss of one IR region in all Gastrodia species; and (2) expansion of IRs, spanning 80% or more of the plastome, in the D. pallens clade.

Increase in AT content of plastomes is considered as indicator of plastome degradation in heterotrophic plants compared with autotrophic species, and the level of AT-richness somewhat correlates with the degree of plastome reduction [11, 14, 46]. Extremely high AT content has been recorded in two heterotrophic lineages, Thismia (Thismiaceae) [46] and Balanophoraceae [47]. Although many species possess highly reduced plastomes, such as Epipogium aphyllum (18,339 bp) (Orchidaceae) and Sciaphila densiflora (21,485 bp) (Triuridaceae), their GC content is no less than 30% [43, 45]. Both Gastrodia and Didymoplexis are fully mycoheterotrophic genera in the Gastrodieae tribe; however, Gastrodia species have a very low GC content even compared to mycoheterotrophic orchids (Supplementary Table S8), whereas D. pallens shows a rather high GC content (34.8%). The high GC content of D. pallens might have been contributed by its genome structure and corresponding adaptive changes. Due to the expansion of IRs, the plastome of D. pallens contains 44 genes, however, there are 28 to 29 genes in plastomes of Gastrodia (Supplementary Table S8). GC content in nontranscribed spacers tends to be considerably lower than elsewhere in the plastome [11, 12]. IR also greatly reduces the substitution rate of genes within IR region [48].

Wicke et al. (2016) suggested that low GC content correlates with increases in the number of structural rearrangements [13]. The 30 bp AT-rich insertions in rrn4.5 not only make it very difficult to predict the rrn4.5 [26, 36] but also present a strategy for structural rearrangements that increase the AT content of plastomes. However, the insertion of long AT-rich sequences may lead to the pseudogenization of rrn4.5. This bias toward AT-richness is lineage specific, and seems to have evolved after the divergence between Gastrodia and Didymoplexis. The AT-rich insertion in rrn4.5 has also been reported in Balanophora (Balanophoraceae) [47]. While most members of Gastrodieae lost matK during evolution, the low GC content of G. elata and G. angusta plastomes, which contain matK, indicates that matK might soon be lost from these two plastomes. The mechanism underlying the adaptation to this bias toward AT-richness remains to be illustrated.

Substitution rates are often elevated in the plastomes of parasitic plants [13, 49, 50]. Wicke et al. (2016) suggested that the elevation of substitution rates in parasitic plants was caused first by relaxed selection and then by rate deceleration due to intensified selection [13]. Our results indicated that Gastrodia is one of the Orchidaceae genera with the highest substitution rate, which is approximately 10-fold higher than that of two autotrophic species of Nervilia [12]. Some housekeeping genes, such as accD and ycf1, were under significant intensified selection in Gastrodia. However, most genes showed very high substitute rates. Jiang et al. (2022) indicated that some NEPs, including genes encoding plastid ribosomal subunits and accD, underwent expansion in Gastrodia genomes [40], which suggests that coevolution of the nuclear genome and plastome might have large effects on the molecular evolution of plastid genes. Although the plastomes of Epipogium (Orchidaceae), Gastrodia (Orchidaceae), and Thismia (Thismiaceae) are minimal and at the final stages of degradation, it seems that these plastomes still have very high substitute rates [43, 46]. Recent molecular dating indicated that the fully mycoheterotrophic lineage Thismia is of a much more recent origin [43]. All Gastrodieae members are mycoheterotrophic and diverged from their autotrophic relatives (Nervilia species) approximately 35 Mya. This suggests that the relaxed selection pressure on plastome genes may last longer than expected.

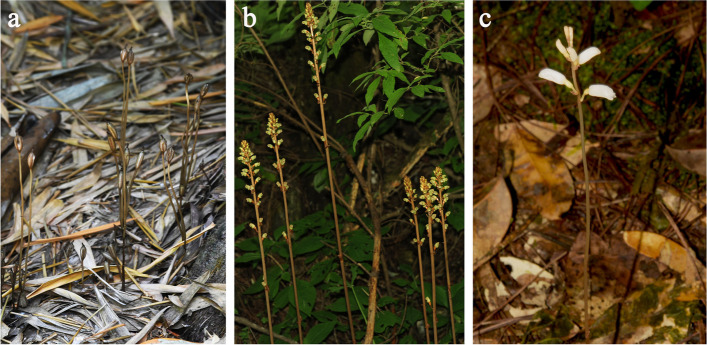

Gene pseudogenization and gene loss are common phenomena in the plastomes of parasitic plants [43, 51]. The ycf1 gene was often absent from the highly reduced plastomes of parasitic plants growing in humid and shaded environments, such as Epipogium [43], Sciaphila [45, 52], and Thismia [46], as well as from the plastomes of aquatic plants including all members of the Podostemaceae family [53]. To our knowledge, D. pallens is the only fully mycoheterotrophic species with two copies of ycf1 in plastomes. In contrast to most mycoheterotrophic plants that grow in humid and shady environments (Supplementary Table S9), our botanical survery indicated that D. pallens grows in very dry and open environments (Fig. 5). Although previous results suggest that environment has little effect on plastome evolution, the presence of a duplicate copy of the ycf1 gene in D. pallens and absence of ycf1 in Podostemaceae suggest that environmental factors may affect the loss, retention, and duplication of genes in the plastomes of parasitic plants in extremely environmental conditions.

Fig. 5.

Natural habitat of Gastrodieae species. a Didymoplexis pallens in dry and open forest. b and c, Gastrodia elata (b) and Gastrodia menghaiensis (c) in shady and humid forest. Photographed by X.H. Jin

Conclusions

The plastomes of Gastrodieae are greatly reduced and characterized by low GC content, rrn block formation, and lineage-specific reconfiguration and gene content. Synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution rates are much higher among the plastomes of Gastrodieae than among those of mycoheterotrophic species in Orchidaceae. Overall, plastomes of Gastrodieae not only serve as an excellent model for illustrating the evolution of plastomes but also provide new insights into plastome evolution in parasitic plants.

Methods

DNA extraction and sequencing

A total of 13 species belonging to the Gastrodieae tribe (Didymoplexis pallens and ten Gastrodia species) and its sister tribe, Nervilieae tribe (two Nervilia species), were sampled (Supplementary Table S1) based on previous results [28, 31]. Genomic DNA was extracted from these species using silica-dried materials with the modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method [54]. DNA was sheared to 400–600 bp fragments using Covaris M220. DNA libraries were prepared using the NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit (New England Biolabs, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and then outsourced to Majorbio Company (Beijing, China) for 100 or 150 bp paired-end sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform. Approximately 5 Gb of raw data were generated for heterotrophic species, and 3 Gb for autotrophic species. Epipactis veratrifolia was used as an autotrophic outgroup for comparative analyses. One plastome downloaded from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) were included in the analyses (Supplementary Table S1). In addition, 19 plastomes representing 19 mycoheterotrophic orchid genera were downloaded from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) for comparison (Supplementary Table S8).

Plastome assembly and annotation

Raw reads were trimmed and filtered using NGSQCTOOLKIT v. 2.3.3 [55]. Plastomes were assembled using GetOrganelle v. 1 [56] and NOVOPlasty [57], with default parameters, and the plastome of Calanthe triplicata (NC_024544.1) was used as a reference. Contigs were combined and extended using Geneious Prime (Biomatters, Inc., Auckland, New Zealand; http://www.geneious.com) to obtain the plastome draft. Assembly errors were corrected in Geneious Prime by mapping reads to the plastome draft. The boundaries of IR regions in each plastome were confirmed by BLAST. Completed plastomes were annotated with PGA [58] using the annotated plastome of C. triplicata (NC_024544.1) as a reference. Then, the annotations were manually checked, and gene or exon boundaries were adjusted using Geneious Prime.

Phylogenetic analysis and molecular dating

All protein-coding sequences in plastomes were used to reconstruct the phylogenetic relationships (Supplementary Table S1). A single gene matrix was aligned using MAFFT under the automatic model selection option [59, 60] with manual adjustments in BioEdit. Then, each matrix was combined into a single plastome supermatrix using SEQUENCEMATRIX v1.7.8 [61]. The concatenated sequences were analyzed using RAxML [62] in CIPRES [63], with the best-fit model GTRGAMMA. Branch support was evaluated by 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Molecular dating was conducted with the combined supermatrix using BEAST v. 2.1.3 [64–66]. Priors were placed on the stem node of Nervilieae and Gastrodieae (offset: 34.93 Mya; sigma: 1.0) and Epipactis and Gastrodieae + Nervilieae (offset: 60.3 Mya; sigma: 1.0), based on previous results [28, 67–69]. Two runs of MCMC searches were performed for 200 million generations with sampling every 10,000 generations, and typically four non-independent chains were used for each run. A Yule process was chosen for the tree prior. Log files were monitored using Tracer v1.6 [70]. The first 10% of trees saved from the first run and the first 8% of trees saved from the second run were discarded, and the remaining trees were combined in Logcombiner v. 2.3.0. Convergence was determined based on the effective sample sizes (ESSs) of all parameters, assessed as more than 100. A maximum clade credibility (MCC) chronogram was generated in TreeAnnotator v. 1.8.0 [64] with median heights for node ages.

Molecular evolutionary analyses

The CDSs of 17 protein-coding genes common to both Gastrodieae and Nervilieae tribes (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S5, Supplementary Material online) were aligned at the codon level using MUSCLE, with the option “-codon”, in MEGA v. 7.0.2 [71]. Stop codons were removed from the CDSs prior to alignment. The phylogenetic analysis-generated phylogram based on all CDSs was used for evolutionary analysis. The plastome of Apostasia odorata (NC_030722.1) was used as a reference. The values of dS and dN in the 17 concatenated protein-coding genes were calculated using CODEML in the PAML v.4.8 software package [72, 73]. The relative values of dS and dN in each CDS were calculated using the pairwise model in the PAML software package [73]. The plastome of Epipactis veratrifolia (NC 030708.1) was used as a reference. Selective regimes among branches were analyzed in PAML v.4.8 using the CODEML module [72, 73]. Differences in substitution rates were specifically tested between Gastrodieae and the autotrophic outgroup, and between Gastrodieae + Nervilieae and the autotrophic outgroup. To determine the relative dN/dS ratio in Gastrodieae among orchids, the substitution rates in CDSs were analyzed in 24 representative mycoheterotrophic species across Orchidaceae (Supplementary Table S9). A total of 17 CDSs common to these mycoheterotrophic species were analyzed as described above. To determine whether the relaxed selection on plastome genes varied with the species lifestyle, the variation in selection pressure on these 17 genes was analyzed using RELAX [74]. Gastrodieae and autotrophic Nervilia species were treated as different test branches.

Codon usage, amino acid frequencies, and GC3 value in the 12 Gastrodieae and Nervilieae plastomes were calculated using CondonW v1.4.2 (http://codonw.sourceforge.net/), based on the subset of 17 common protein-coding genes. Genes were categorized into groups according to gene function or subunits that form a functional protein complex, as described previously [75]. Statistical analyses were performed using the R software package (http://www.r-project.org), and correction for multiple comparisons was conducted using the Benjamini and Hochberg method (1995), which controls for the false discovery rate. RNAs of various species were compared using Geneious10.2.3, and the secondary structure of RNA was determined using the online software (http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at//cgi-bin/RNAWebSuite/RNAfold.cgi). Transcriptome data of G. elata (SRR18147619) was downloaded from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and analyzed as described previously [36].

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Zhanghai Li, Dr. Deyi Wang, Dr. Xiao Ma for their help on data analyses.

Abbreviations

- IR

Inverted repeat

- LSC

Long single-copy

- SSC

Short single-copy

- ML

Maximum-likelihood

- CDS

Coding sequences

- Ma

Million years ago

Authors’ contributions

XJ and YW designed the project. BS, XJ, YH, YL, CM and JL collected the materials. YW analyzed the data. XJ, YW, BS, YQ, YL, JL, BY and CM wrote and revised the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31870195 to XJ, 32160050 to YL). The funding body played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All newly sequenced and annotated plastid genomes generated in this study have been submitted to NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) with accession number from ON515479 to ON515489 (Table 1). All plastid genome assembly and annotation data are publicly available (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The online resources of genomic data were downloaded from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), including transcriptome data of Gastrodia elata (SRR18147619) and plastid genomes with GenBank accession numbers listed in Supplementary Table S8 and S9.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Plant materials used in this study were collected in field with necessary permissions from local authorities. Voucher specimens have been deposited in publicly available herbaria (PE, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences; IBK, Guangxi Institute of Botany, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region and the Chinese Academy of Sciences) (Table 1). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yingying Wen and Ying Qin contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yan Liu, Email: gxibly@163.com.

Boyun Yang, Email: yangboyun@163.com.

Xiaohua Jin, Email: xiaohuajin@ibcas.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Douglas SE. Plastid evolution: origins, diversity, trends. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8(6):655–661. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(98)80033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zimorski V, Ku C, Martin WF, Gould SB. Endosymbiotic theory for organelle origins. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2014;22:38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wicke S, Schneeweiss GM, dePamphilis CW, Muller KF, Quandt D. The evolution of the plastid chromosome in land plants: gene content, gene order, gene function. Plant Mol Biol. 2011;76(3–5):273–297. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9762-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao YB, Yin JL, Guo HY, Zhang YY, Xiao W, Sun C, Wu JY, Qu XB, Yu J, Wang XM, et al. The complete chloroplast genome provides insight into the evolution and polymorphism of Panax ginseng. Front Plant Sci. 2015;5:12. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stiller JW, Reel DC, Johnson JC. A single origin of plastids revisited: convergent evolution in organellar genome content. J Phycol. 2003;39(1):95–105. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.02070.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lane N. Plastids, genomes, and the probability of gene transfer. Genome Biol Evol. 2011;3:372–374. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolfe KH, Morden CW, Palmer JD. Function and evolution of a minimal plastid genom from a nonphotosynthetic parasitic plant. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(22):10648–10652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNeal JR, Kuehl JV, Boore JL, dePamphilis CW. Complete plastid genome sequences suggest strong selection for retention of photosynthetic genes in the parasitic plant genus Cuscuta. BMC Plant Biol. 2007;7:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-7-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krause K. Piecing together the puzzle of parasitic plant plastome evolution. Planta. 2011;234(4):647–656. doi: 10.1007/s00425-011-1494-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrett CF, Davis JI. The plastid genom of the mycoheterotrophic corallorhiza striata (Orchidaceae) is in the relatively early stages of degradation. Am J Bot. 2012;99(9):1513–1523. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1200256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wicke SK, Schaferhoff B, dePamphilis CW, Muller KF. Disproportional Plastome-Wide Increase of Substitution Rates and Relaxed Purifying Selection in Genes of Carnivorous Lentibulariaceae. Mol Biol Evol. 2014;31(3):529–545. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng YL, Wicke S, Li JW, Han Y, Lin CS, Li DZ, Zhou TT, Huang WC, Huang LQ, Jin XH. Lineage-Specific Reductions of Plastid Genomes in an Orchid Tribe with Partially and Fully Mycoheterotrophic Species. Genome Biol Evol. 2016;8(7):2164–2175. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evw144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wicke S, Muller KF, dePamphilis CW, Quandt D, Bellot S, Schneeweiss GM. Mechanistic model of evolutionary rate variation en route to a nonphotosynthetic lifestyle in plants. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(32):9045–9050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1607576113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barrett CF, Freudenstein JV, Li J, Mayfield-Jones DR, Perez L, Pires JC, Santos C. Investigating the Path of Plastid Genome Degradation in an Early-Transitional Clade of Heterotrophic Orchids, and Implications for Heterotrophic Angiosperms. Mol Biol Evol. 2014;31(12):3095–3112. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barrett CF, Kennedy AH. Plastid Genome Degradation in the Endangered, Mycoheterotrophic, North American Orchid Hexalectris warnockii. Genome Biol Evol. 2018;10(7):1657–1662. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evy107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim HT, Shin CH, Sun H, Kim JH. Sequencing of the plastome in the leafless green mycoheterotroph Cymbidium macrorhizon helps us to understand an early stage of fully mycoheterotrophic plastome structure. Plant Syst Evol. 2018;304(2):245–258. doi: 10.1007/s00606-017-1472-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider AC, Braukmann T, Banerjee A, Stefanovic S. Convergent Plastome Evolution and Gene Loss in Holoparasitic Lennoaceae. Genome Biol Evol. 2018;10(10):2663–2670. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evy190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim YK, Jo S, Cheon SH, Joo MJ, Hong JR, Kwak MH, Kim KJ. Extensive Losses of Photosynthesis Genes in the Plastome of a Mycoheterotrophic Orchid, Cyrtosia septentrionalis (Vanilloideae: Orchidaceae) Genome Biol Evol. 2019;11(2):565–571. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evz024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lallemand F, Logacheva M, Le-Clainche I, Berard A, Zheleznaia E, May M, Jakalski M, Delannoy E, Le Paslier MC, Selosse MA. Thirteen New Plastid Genomes from Mixotrophic and Autotrophic Species Provide Insights into Heterotrophy Evolution in Neottieae Orchids. Genome Biol Evol. 2019;11(9):2457–2467. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evz170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li XJ, Qian X, Yao G, Zhao ZT, Zhang DX. Plastome of mycoheterotrophic Burmannia itoana Mak. (Burmanniaceae) exhibits extensive degradation and distinct rearrangements. PeerJ. 2019;7:17. doi: 10.7717/peerj.7787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nevill PG, Howell KA, Cross AT, Williams AV, Zhong X, Tonti-Filippini J, Boykin LM, Dixon KW, Small I. Plastome-Wide Rearrangements and Gene Losses in Carnivorous Droseraceae. Genome Biol Evol. 2019;11(2):472–485. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evz005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li ZH, Jiang Y, Ma X, Li JW, Yang JB, Wu JY, Jin XH. Plastid Genome Evolution in the Subtribe Calypsoinae (Epidendroideae, Orchiaaceae) Genome Biol Evol. 2020;12(6):867–870. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evaa091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen JF, Yu RX, Dai JH, Liu Y, Zhou RC. The loss of photosynthesis pathway and genomic locations of the lost plastid genes in a holoparasitic plant Aeginetia indica. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20(1):199. doi: 10.1186/s12870-020-02415-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merckx VS, Freudenstein JV, Kissling J, Christenhusz MJ, Stotler RE, Crandall-Stotler B, Wickett N, Rudall PJ, Maas-Van DKH, Maas PJ. Taxonomy and classification. In: Mycoheterotrophy. Springer New York Heidelberg Dordrecht London; 2013. p. 19–101.

- 25.Hsu TC, Kuo CM. Gastrodia albida (Orchidaceae), a new species from Taiwan. Ann Bot Fenn. 2011;48(3):272–275. doi: 10.5735/085.048.0308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Q, Ya JD, Wu XF, Shao BY, Chi KB, Zheng HL, Li JW, Jin XH. New taxa of tribe Gastrodieae (Epidendroideae, Orchidaceae) from Yunnan, China and its conservation implication. Plant Diversity. 2021;43(5):420–425. doi: 10.1016/j.pld.2021.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aung YL, Jin XH. Gastrodia kachinensis (Orchidaceae), a new species from Myanmar. PhytoKeys. 2018;94:23–29. doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.94.21348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li YX, Li ZH, Schuiteman A, Chase MW, Li JW, Huang WC, Hidayat A, Wu SS, Jin XH. Phylogenomics of Orchidaceae based on plastid and mitochondrial genomes. Mol Phylogen Evol. 2019;139:11. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2019.106540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma L, Chen XY, Liu JF, Chen SP. Gastrodia fujianensis (Orchidaceae, Epidendroideae, Gastrodieae), a new species from China. Phytotaxa. 2019;391(4):269–272. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.391.4.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suetsugu K. Gastrodia amamiana (Orchidaceae; Epidendroideae; Gastrodieae), a new completely cleistogamous species from Japan. Phytotaxa. 2019;413(3):225–230. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.413.3.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim YK, Jo S, Cheon SH, Joo MJ, Hong JR, Kwak M, Kim KJ. Plastome Evolution and Phylogeny of Orchidaceae, With 24 New Sequences. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:27. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Metusala D. Gastrodia khangii, a new synonym and new record of Gastrodia bambu (Orchidaceae) in Vietnam. Phytotaxa. 2020;454(1):55–62. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.454.1.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suetsugu K. Gastrodia longiflora (Orchidaceae: Epidendroideae: Gastrodieae), a new mycoheterotrophic species from Ishigaki Island, Ryukyu Islands. Japan Phytotaxa. 2021;502(1):107–110. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.502.1.9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pridgeon AM, Cribb PJ, Chase MW, Rasmussen FN. Genera Orchidacearum Vol. 4. Epidendroideae (Part 1) Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Givnish TJ, Zuluaga A, Spalink D, Gomez MS, Lam VKY, Saarela JM, Sass C, Iles WJD, deSousa DJL, Leebens-Mack J, et al. Monocot plastid phylogenomics, timeline, net rates of species diversification, the power of multi-gene analyses, and a functional model for the origin of monocots. Am J Bot. 2018;105(11):1888–1910. doi: 10.1002/ajb2.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuan Y, Jin XH, Liu J, Zhao X, Zhou JH, Wang X, Wang DY, Lai CJS, Xu W, Huang JW, et al. The Gastrodia elata genome provides insights into plant adaptation to heterotrophy. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1615. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03423-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li F, Wang W. Research Progress of Gastrodia elata BI. Heilongjiang Agric Sci. 2009;3:148–150. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhan HD, Zhou HY, Sui YP, Du XL, Wang WH, Dai L, Sui F, Huo HR, Jiang TL. The rhizome of Gastrodia elata Blume - An ethnopharmacological review. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;189:361–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu YX, Lei YT, Su ZX, Zhao M, Zhang JX, Shen GJ, Wang L, Li J, Qi JF, Wu JQ. A chromosome-scale Gastrodia elata genome and large-scale comparative genomic analysis indicate convergent evolution by gene loss in mycoheterotrophic and parasitic plants. Plant J. 2021;108(6):1609–1623. doi: 10.1111/tpj.15528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang Y, Hu XD, Yuan Y, Guo XL, Chase MW, Ge S, Li JW, Fu JL, Li K, Hao M, et al. The Gastrodia menghaiensis (Orchidaceae) genome provides new insights of orchid mycorrhizal interactions. BMC Plant Biol. 2022;22(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s12870-021-03403-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen SC, Liu ZJ, Zhu GH, Lang KY, Tsi ZH, Luo YB, Jin XH, Cribb PJ, Wood JJ, Gale SW, et al. Flora of China. Beijing: Science Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li ZH, Ma X, Wang DY, Li YX, Wang CW, Jin XH. Evolution of plastid genomes of Holcoglossum (Orchidaceae) with recent radiation. BMC Evol Biol. 2019;19:63–73. doi: 10.1186/s12862-019-1384-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schelkunov MI, Shtratnikova VY, Nuraliev MS, Selosse MA, Penin AA, Logacheva MD. Exploring the Limits for Reduction of Plastid Genomes: A Case Study of the Mycoheterotrophic Orchids Epipogium aphyllum and Epipogium roseum. Genome Biol Evol. 2015;7(4):1179–1191. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Delannoy E, Fujii S, des Francs-Small CC, Brundrett M, Small I. Rampant Gene Loss in the Underground Orchid Rhizanthella gardneri Highlights Evolutionary Constraints on Plastid Genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(7):2077–86. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Petersen G, Zervas A, Pedersen H Aelig, Seberg O. Genome Reports: Contracted Genes and Dwarfed Plastome in Mycoheterotrophic Sciaphila thaidanica (Triuridaceae, Pandanales) Genome Biol Evol. 2018;10(3):976–81. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evy064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yudina SV, Schelkunov MI, Nauheimer L, Crayn D, Chantanaorrapint S, Hrones M, Sochor M, Dancak M, Mar SS, Luu HT, et al. Comparative Analysis of Plastid Genomes in the Non-photosynthetic Genus Thismia Reveals Ongoing Gene Set Reduction. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.602598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Su HJ, Barkman TJ, Hao W, Jones SS, Naumann J, Skippington E, Wafula EK, Hu JM, Palmer JD, dePamphilis CW. Novel genetic code and record-setting AT-richness in the highly reduced plastid genome of the holoparasitic plant Balanophora. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116(3):934–943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1816822116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu AD, Guo WH, Gupta S, Fan WS, Mower JP. Evolutionary dynamics of the plastid inverted repeat: the effects of expansion, contraction, and loss on substitution rates. New Phytol. 2016;209(4):1747–1756. doi: 10.1111/nph.13743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lam VKY, Darby H, Merckx V, Lim G, Yukawa T, Neubig KM, Abbott JR, Beatty GE, Provan J, Gomez MS, et al. Phylogenomic inference in extremis: a case study with mycoheterotroph plastomes. Am J Bot. 2018;105(3):480–494. doi: 10.1002/ajb2.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shepeleva EA, Schelkunov MI, Hrones M, Sochor M, Dancak M, Merckx V, Kikuchi I, Chantanaorrapint S, Suetsugu K, Tsukayai H, et al. Phylogenetics of the mycoheterotrophic genus Thismia (Thismiaceae: Dioscoreales) with a focus on the Old World taxa: delineation of novel natural groups and insights into the evolution of morphological traits. Bot J Linn Soc. 2020;193(3):287–315. doi: 10.1093/botlinnean/boaa017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li ZH, Ma X, Wen Y, Chen SS, Jiang Y, Jin XH. Plastome of the mycoheterotrophic eudicot Exacum paucisquama (Gentianaceae) exhibits extensive gene loss and a highly expanded inverted repeat region. PeerJ. 2020;8:11. doi: 10.7717/peerj.9157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lam VKY, Gomez MS, Graham SW. The Highly Reduced Plastome of Mycoheterotrophic Sciaphila (Triuridaceae) Is Colinear with Its Green Relatives and Is under Strong Purifying Selection. Genome Biol Evol. 2015;7(8):2220–2236. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bedoya AM, Ruhfel BR, Philbrick CT, Madrinan S, Bovet CP, Mesterhazy A, Olmstead RG. Plastid Genomes of Five Species of Riverweeds (Podostemaceae): Structural Organization and Comparative Analysis in Malpighiales. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:14. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li J, Wang S, Yu J, Wang L, Zhou S. A Modified CTAB Protocol for Plant DNA Extraction. C Chin Bull Bot. 2013;48(1):72–78. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1259.2013.00072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Patel RK, Jain M. NGS QC Toolkit: A Toolkit for Quality Control of Next Generation Sequencing Data. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2):7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jin JJ, Yu WB, Yang JB, Song Y, dePamphilis CW, Yi TS, Li DZ. GetOrganelle: a fast and versatile toolkit for accurate de novo assembly of organelle genomes. Genome Biol. 2020;21(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-1926-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dierckxsens N, Mardulyn P, Smits G. NOVOPlasty: de novo assembly of organelle genomes from whole genome data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(4):9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qu XJ, Moore MJ, Li DZ, Yi TS. PGA: a software package for rapid, accurate, and flexible batch annotation of plastomes. Plant Methods. 2019;15:12. doi: 10.1186/s13007-019-0435-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(4):772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kuraku S, Zmasek CM, Nishimura O, Katoh K. aLeaves facilitates on-demand exploration of metazoan gene family trees on MAFFT sequence alignment server with enhanced interactivity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(W1):W22–W28. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vaidya G, Lohman DJ, Meier R. SequenceMatrix: concatenation software for the fast assembly of multi-gene datasets with character set and codon information. Cladistics. 2011;27(2):171–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2010.00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kozlov AM, Darriba D, Flouri T, Morel B, Stamatakis A. RAxML-NG: a fast, scalable and user-friendly tool for maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference. Bioinformatics. 2019;35(21):4453–4455. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miller MA, Schwartz T, Pickett BE, He S, Klem EB, Scheuermann RH, Passarotti M, Kaufman S, O'Leary MA. A RESTful API for Access to Phylogenetic Tools via the CIPRES Science Gateway. Evol Bioinform. 2015;11:43–48. doi: 10.4137/EBO.S21501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, Xie D, Rambaut A. Bayesian Phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29(8):1969–73. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bouckaert R, Heled J, Kuhnert D, Vaughan T, Wu CH, Xie D, Suchard MA, Rambaut A, Drummond AJ. BEAST 2: a software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. Plos Comput Biol. 2014;10(4):6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bouckaert R, Vaughan TG, Barido-Sottani J, Duchene S, Fourment M, Gavryushkina A, Heled J, Jones G, Kuhnert D, De Maio N, et al. BEAST 2.5: an advanced software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. Plos Comput Biol. 2019;15(4):28. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Choi HI, Lyu JI, Lee HO, Kim JB, Kim SH. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of an orchid hybrid Cymbidium sinense (female) x C. goeringii (male) Mitochondrial DNA B. 2020;5(3):3802–3. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2020.1839367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Givnish TJ, Spalink D, Ames M, Lyon SP, Hunter SJ, Zuluaga A, Doucette A, Caro GG, McDaniel J, Clements MA, et al. Orchid historical biogeography, diversification, Antarctica and the paradox of orchid dispersal. J Biogeogr. 2016;43(10):1905–1916. doi: 10.1111/jbi.12854. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Givnish TJ, Spalink D, Ames M, Lyon SP, Hunter SJ, Zuluaga A, Iles WJD, Clements MA, Arroyo MTK, Leebens-Mack J, et al. Orchid phylogenomics and multiple drivers of their extraordinary diversification. Proc R Soc B-Biol Sci. 1814;2015(282):171–180. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rambaut A, Drummond AJ, Xie D, Baele G, Suchard MA. Posterior Summarization in Bayesian Phylogenetics Using Tracer 1.7. Syst Biol. 2018;67(5):901–4. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syy032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33(7):1870–4. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang ZH. PAML: a program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Comput Appl Biosci. 1997;13(5):555–556. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/13.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yang ZH. PAML 4: Phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24(8):1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wertheim JO, Murrell B, Smith MD, Pond SLK, Scheffler K. RELAX: Detecting Relaxed Selection in a Phylogenetic Framework. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32(3):820–832. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Guisinger MM, Kuehl JNV, Boore JL, Jansen RK. Genome-wide analyses of Geraniaceae plastid DNA reveal unprecedented patterns of increased nucleotide substitutions. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(47):18424–18429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806759105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All newly sequenced and annotated plastid genomes generated in this study have been submitted to NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) with accession number from ON515479 to ON515489 (Table 1). All plastid genome assembly and annotation data are publicly available (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The online resources of genomic data were downloaded from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), including transcriptome data of Gastrodia elata (SRR18147619) and plastid genomes with GenBank accession numbers listed in Supplementary Table S8 and S9.