To the Editor:

Goal-oriented therapy, also known as treat-to-target therapy, is recommended in the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension [1, 2]. This approach, first described by Hoeper et al. [3], has emerged, alongside early detection, as a central aspect of managing pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Goal-oriented therapy is proactive as it defines treatment goals ahead of time and proposes to alter the treatment strategy if those goals are not met.

In a review article on goal-oriented therapy in PAH by Sitbon and Galiè [4], the authors noted that existing treatment goals are mainly based on parameters with prognostic value at baseline and highlighted the need for additional data to identify goals that have prognostic relevance during treatment. Subsequently, a single-centre study in 109 patients with idiopathic PAH has provided evidence to support the prognostic importance of achieving certain goals during therapy [5]. In this study, the following parameters were individually associated with improved prognosis when assessed at the first follow-up visit (3–12 months after initiation of PAH-specific therapy), supporting their use as treatment goals: 1) improvement to, or maintenance of, New York Heart Association/World Health Organization functional class (FC) I or II; 2) cardiac index ≥2.5 L·min−1·m−2; 3) mixed venous oxygen saturation ≥65%; or 4) N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels <1,800 ng·L−1 [5].

The review by Sitbon and Galiè [4] also highlighted that combining baseline parameters may improve prediction of survival in PAH, and emphasised the need for multiple treatment goals. In a recent multicentre study of 226 consecutive patients with idiopathic or familial PAH, the combined use of baseline values for peak oxygen uptake and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) provided a more comprehensive prognostic assessment than either parameter alone [6]. Taking the concept a step further, two independent risk scores that combine multiple clinical parameters to predict prognosis have been developed [7, 8]. In a recent single centre, retrospective study that independently validated the REVEAL (Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term PAH Disease Management) score [8], it was shown that assessment of the REVEAL prediction score in addition to FC enhanced prediction of prognosis compared with FC alone [9]. These data have given us a better understanding of the importance of using multiple parameters when assessing prognosis, suggesting that there is a need to employ multiple treatment goals to monitor treatment response in PAH patients.

Implementation of goal-oriented therapy remains challenging despite the availability of new data and published guidelines. The application of generic guidelines to individual patients requires careful consideration of the PAH aetiology and comorbidities. The aim of treatment has evolved from achieving a “stable” condition for the patient to reaching a “stable and satisfactory” condition, which is defined in the ESC/ERS guidelines as fulfilling the majority of criteria indicative of better prognosis [1, 2]. However, for patients that do not clearly meet the criteria for either better or worse prognosis (i.e. those that fall in the grey zone), it remains unclear if they are “stable and satisfactory” and, thus, it is difficult to determine the best treatment strategy. Although published case studies provide practical examples of using goal-oriented therapy in clinical practice [10, 11], additional guidance is needed.

An additional issue is that recommendations from the ESC/ERS guidelines are not always followed in clinical practice. For example, intravenous epoprostenol is recommended in the guidelines as first-line therapy for patients in FC IV, due to its benefit on long-term outcomes [2]. Despite this recommendation, however, a recent study reported that 40% of FC IV patients were not receiving a parenteral prostanoid at the time of death [12]. Additionally, in some countries other barriers to implementing treat-to-target therapy may exist, such as lack of approval status and reimbursement for certain targeted therapies.

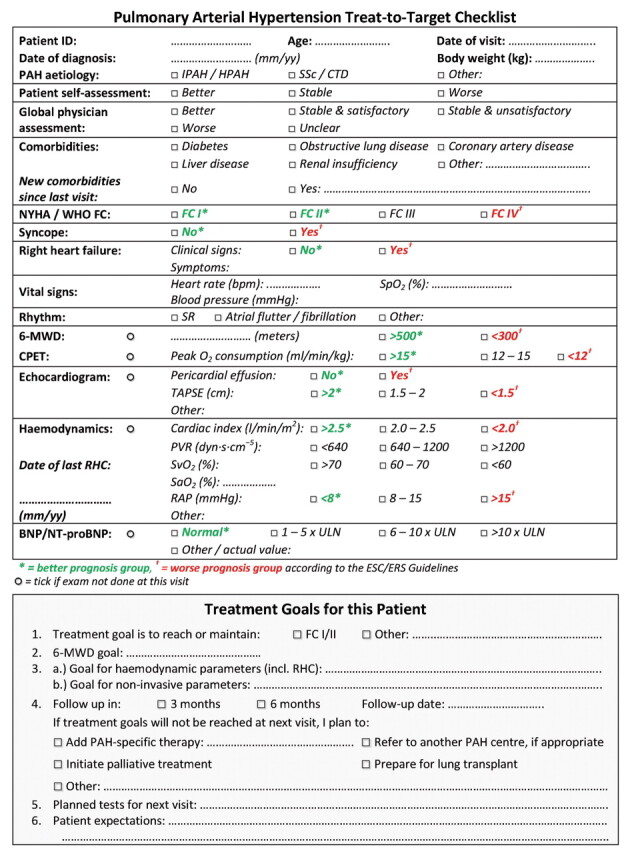

To define potential initiatives to support expert clinicians in implementing goal-oriented therapy in their daily clinical practice, an industry-sponsored Steering Committee for the Implementation of the Treat-to-Target Guidelines in PAH was recently formed. The Committee comprises of 11 members (including pulmonologists, cardiologists and a nurse specialist), who are experts in the field of PAH, representing 11 PAH centres from six European countries. A consensus-based checklist was developed (fig. 1) with the aim of providing a practical tool to assist clinicians in the application of goal-oriented therapy in individual PAH patients in a structured, consistent and prospective manner. It targets PAH-expert centres and the centres that they closely collaborate with.

Figure 1.

An expert proposal for a treat-to-target checklist for pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). IPAH: idiopathic PAH; HPAH: heritable PAH; SSc: systemic sclerosis; CTD: connective tissue disease; NYHA: New York Heart Association; WHO: World Health Organization; FC: functional class; SpO2: arterial oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry; SR: sinus rhythm; 6-MWD: 6-min walk distance; CPET: cardiopulmonary exercise testing; TAPSE: tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; RHC: right heart catheterisation; PVR: pulmonary vascular resistance; SvO2: mixed venous oxygen saturation; SaO2: arterial oxygen saturation; RAP: right atrial pressure; BNP: brain natriuretic peptide; NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro-BNP; ULN: upper limit of normal.

The PAH treat-to-target checklist includes a section to document clinical assessment of the patient, at the time of treatment initiation and upon subsequent re-assessments. This is followed by a section to record the treatment goals set by the clinician that the patient should reach by the next visit (taking into consideration confounding and limiting factors, such as comorbidities or age) and allows clinicians to document the pre-determined schedule for re-assessment and action to be taken if the treatment goals are not met (e.g. switching or escalating therapy).

The Committee have developed this checklist to allow individualised treatment goals to be set, treatment response to be monitored and a clear and prospective treatment strategy to be developed for each patient. By setting individualised treatment goals, clinicians can keep track of the patient's response to therapy and can subsequently take appropriate action depending on the patient's response. The frequency of re-assessment should follow the recommendations in the ESC/ERS guidelines [1, 2].

Some of the parameters that are recommended in the ESC/ERS guidelines, which are reflected accordingly in the checklist, may carry more weight than others. This is dependent on factors such as clinician experience and differences in usual clinical practice. For example, in centres that do not perform frequent right heart catheterisation, noninvasive assessments such as echocardiography, cardiopulmonary exercise testing, BNP or N-terminal-proBNP levels and magnetic resonance imaging may play a more prominent role in the decision-making process.

The treat-to-target checklist represents the expert opinion of the Steering Committee and has not undergone formal validation. The checklist is intended to support the clinician in applying the ESC/ERS guidelines to each individual patient in their daily clinical practice. However, it cannot replace clinical judgement and the experience of an expert.

Acknowledgments

This project was developed and funded by Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd (Allschwil, Switzerland). Medical writing assistance was provided by R. Lloyd (nspm UK Ltd, Cheadle, UK), funded by Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd.

REFERENCES

- 1.Galiè N, Hoeper MM, Humbert M, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2009; 34: 1219–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galiè N, Hoeper MM, Humbert M, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J 2009; 30: 2493–2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoeper MM, Markevych I, Spiekerkoetter E, et al. Goal-oriented treatment and combination therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2005; 26: 858–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sitbon O, Galiè N. Treat-to-target strategies in pulmonary arterial hypertension: the importance of using multiple goals. Eur Respir Rev 2010; 19: 272–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nickel N, Golpon H, Greer M, et al. The prognostic impact of follow-up assessments in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2012; 39: 589–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wensel R, Francis DP, Meyer FJ, et al. Incremental prognostic value of cardiopulmonary exercise testing and resting haemodynamics in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Int J Cardiol 2012. [Epub ahead of print DOI:10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.03.123]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Humbert M, Sitbon O, Yaici A, et al. Survival in incident and prevalent cohorts of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2010; 36: 549–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benza RL, Miller DP, Gomberg-Maitland M, et al. Predicting survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension: insights from the Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Disease Management (REVEAL). Circulation 2010; 122: 164–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kane GC, Maradit-Kremers H, Slusser JP, et al. Integration of clinical and hemodynamic parameters in the prediction of long-term survival in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest 2011; 139: 1285–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoeper MM. “Treat-to-target” in pulmonary arterial hypertension and the use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as a bridge to transplantation. Eur Respir Rev 2011; 20: 297–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sitbon O. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: combination therapy in the modern management era. Eur Respir Rev 2010; 19: 348–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farber H, Miller D, Beery F, et al. Use of parenteral prostanoids at time of death in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension enrolled in REVEAL. Chest 2011; 140: 903A. [Google Scholar]