Abstract

Improved care in pulmonary arterial hypertension has led to increased longevity for patients, with a paralleled evolution in the nature of their needs. There is more focus on the impact of the disease on their day-to-day activities and quality of life, and a holistic approach is coming to the front of pulmonary arterial hypertension management, which places the patient at the centre of their own healthcare. Patients are thus becoming more proactive, involved and engaged in their self-care, and this engagement is an important factor if patient outcomes are to improve. In addition, involvement of the patient may improve their ability to cope with pulmonary arterial hypertension, as well as help them to become effective in the self-management of their disease. Successful patient engagement can be achieved through effective education and the delivery and communication of timely, high-quality information. A multidisciplinary approach involving healthcare professionals, carers, patient associations and expert patient programmes can also encourage patients to engage. Strategies that promote patient engagement can help to achieve the best possible care and support for the patient and also benefit healthcare providers.

Short abstract

The evolving needs of PAH requires patients to participate in self-management of their disease http://ow.ly/uT79305pyyj

Introduction

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) has evolved from a disease with a poor prognosis to a disease that patients can live with over the long term [1, 2]. A range of treatment options, together with specialist healthcare, have led to improved outcomes for PAH patients in terms of symptom management and disease progression [3, 4]. As PAH patients live longer [2], challenges arise that go beyond the treatment of symptoms. The majority of patients report that PAH has a “very significant impact” on daily life, affecting physical ability, working life, income, household chores, intimacy and emotional well-being [5, 6]. An increased focus on the quality of life (QoL) [2, 7] and evolving needs of PAH patients necessitates an approach that encourages them to participate in the self-management of their disease. As many patients organise their day-to-day activities and disease management alone, there is a need for them to receive support towards furthering their own self-care.

Traditionally, the role of the patient has generally been passive when receiving medical advice and treatment [8]. Today, there is a growing need for patients to become active participants in their own care [9]. Such “activated” patients are engaged, seek out information [10] and participate in the management of their disease by being involved in decision making and taking action with regards to their care [10]. As a result, activated patients experience better health outcomes at a lower healthcare cost [9, 11, 12].

An active partnership between patients and healthcare professionals (HCPs), incorporating education and support for self-management, is essential for the optimal management of chronic illness [8] and should be integrated from the time of diagnosis [10]. This review describes the roles and challenges faced by HCPs, patient associations and expert patients in encouraging patient engagement in PAH. It draws upon the authors' own experience as well as feedback from other representatives of patients and HCPs shared at workshops focused on patient engagement.

The importance of patient engagement and current challenges in PAH

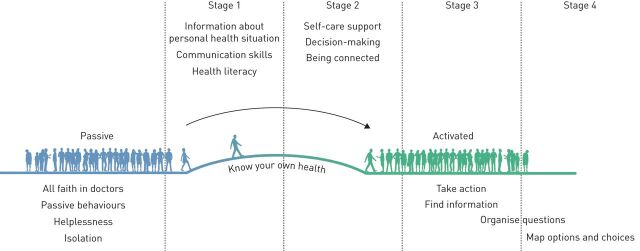

To better understand patient engagement, it is useful to differentiate the concept of patient engagement from other terms that are often used in the literature, such as patient empowerment and patient activation. Patient empowerment is a concept that is psychological in nature and describes the patients' subjective sense of control over their own disease and treatment management and the feeling of being directly responsible for their own health outcomes [13, 14]. Patient activation refers to an “individual's knowledge, skill and confidence in managing his/her own health and healthcare” [15]. Patient activation can be thought of as having four stages (figure 1) [9, 16]. In stage one the patient must believe that their role is important in managing their own health. Having the confidence and knowledge necessary to take action is defined as stage two. Stage three is reached when the patient takes action to maintain and improve their health and stage four is achieved when the patient continues with self-management, even under stress. In practice, the process is not linear for all patients and an individual may go back a stage or be in different stages for different aspects of their disease. Patients often have different attitudes when dealing with their health [17] and this can have an impact on the activation process. Patient activation, although often used synonymously with patient engagement, is just one aspect of an individual's ability to engage in their own care [12]. Patient engagement extends further and is often used as an umbrella term that covers different aspects of patient interaction with their healthcare system [18] at various stages of their disease [12].

FIGURE 1.

Four potential stages of patient activation. Reproduced from [10].

A substantial evidence base suggests that patient engagement in general improves patient outcomes [8, 12, 19]. PAH patients who feel well-informed find it easier to cope with their disease [20] and informed patients who receive comprehensive guidance have better outcomes [2]. Patients who are involved in the decision making regarding their disease are more engaged and motivated. Patients with chronic conditions who attended a self-management programme reported significant improvements in patient activation [21]. Further improvements were reported across a range of measures, including health-related QoL, health status, anxiety, depression and self-management skills [21]. The importance of shared decision making, where PAH patients express their preferences with regards to their care, has been documented [7, 10]. Patients who understand the benefits of being actively involved in decisions about their treatment and care are able to make informed decisions and to take ownership of their disease, which leads to improved outcomes [8].

A number of challenges exist in the engagement of PAH patients. There is a need for more education, with both PAH patients and their carers stating that they would like more information about the disease [5, 6, 20]. This includes the emotional impact of PAH, treatment options and the implications of different modes of drug administration [5]. Patients have highlighted a lack of sufficient information exchange between expert PAH teams and local HCPs [6, 7] and, therefore, communication between HCPs should be improved [10]. A wealth of information on PAH is already available to patients; nevertheless, there is a need to optimise its delivery and communication. Patients increasingly seek information about PAH on the internet [6] and it is vital that this information is correct and that HCPs are aware of sources of high-quality information. The optimal timing and method of delivery of information to patients should reflect their changing needs over time [10]. Cognitive function can be impaired in PAH, affecting verbal learning, memory, decision making and motor function [22]. This may limit the patient's ability to engage and self-manage their disease. A further challenge is that some patients may not wish to be engaged in the management of their disease. Being engaged and active means confronting and learning to deal with the facts about their disease. For some individuals, choosing not to engage may be a coping mechanism in a disease with a harsh reality. The benefits of being an engaged patient should be communicated to these patients.

How can we engage patients and better meet their information needs?

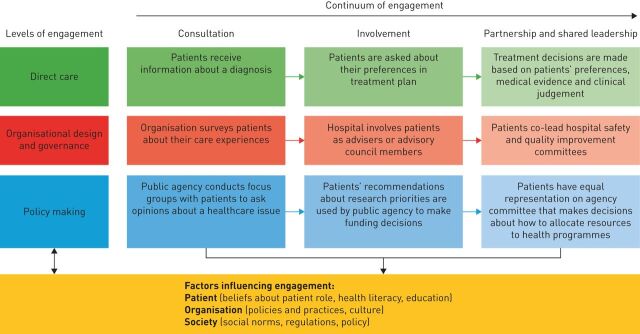

A multidimensional framework has been devised for the development of interventions and policies that support patient and family engagement [12]. The framework highlights different ways in which patients can engage across the healthcare system and the levels at which this can occur throughout the course of the disease. It examines the factors that can influence patients' willingness and ability to be engaged in their disease and the impact that can be achieved by implementing policies that increase engagement across multiple levels (figure 2) [12].

FIGURE 2.

Multidimensional framework for patient and family engagement. A number of factors influence whether and to what extent patients engage at different points along the continuum of engagement. These factors can be grouped into three levels of engagement related to patients, organisations and society. Increased patient participation and collaboration is observed with increased shift to the right on the continuum of engagement. Reproduced from Project HOPE/Health Affairs [12] with permission from the publisher.

Patient engagement is best initiated in a multidisciplinary environment [2] by an expert team of HCPs with a diverse set of skills and experience who are best able to support the PAH patient [20, 23]. The European Society of Cardiology/European Respiratory Society guidelines recommend that the PAH team collaborates with other professionals, including psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers and patient associations [3, 4]. Such a multidisciplinary environment can only realistically be provided in large-volume expert centres and many patients will live far from such centres. These patients will require additional support and management from their local family doctors and possibly HCPs in shared care centres, necessitating good communication and patient-held records for optimal patient management. A collaborative approach between HCPs, patients associations, carers and expert patient programmes can optimise patient engagement.

Providing timely, individualised information to PAH patients

PAH patients require a range of information encompassing treatment options, the physical and personal impact of PAH and/or treatment, emotional well-being and socioeconomic factors. Patients need an understanding of what their treatment involves, including the practical aspects of how to manage titration procedures and complicated drug delivery systems (such as intravenous and subcutaneous pumps). PAH patients often have a restricted ability to carry out their daily activities, which may leave them feeling frustrated and angry [5]. Therefore, advice on the impact of the physical restrictions that PAH can impose on patients is crucial. Practical support for PAH patients is discussed in more detail in the article by Farber and Gin-Sing [24] in this issue of the European Respiratory Review. PAH patients often have financial burdens resulting from their reduced ability to work, which may lead to frustration, anger and low self-esteem [5]. Indeed, a significant proportion of PAH patients suffer from depression [25]. Informing women that pregnancy is high risk in PAH is essential [2], as is providing personalised advice on suitable methods of family planning. This is discussed further in the article by Olsson and Channick [26] in this issue of the European Respiratory Review.

Carers and families of patients, including children, also benefit from receiving appropriate information on PAH, as they need to understand the challenges of the disease, how it will impact their daily life and how they may be able to help the patients [27]. By attending clinic appointments with the patient, family members can learn about PAH and contribute to the patient's individualised treatment plan [27]. Tailored resources to support parents in explaining their disease to children have been developed, including the Medikidz comic book range that helps children understand complex diseases [10].

Patients require high-quality information [28], tailored to the individual [10] and disseminated at the appropriate time. Patients have reported a desire to receive information that is staggered throughout the course of their disease [5]. At diagnosis, patients wish to receive information on the disease and its treatment [5]. At later stages, patients request patient stories, testimonials and information on the effect of PAH on travel and sexual relationships [5]. Patient stories and shared experiences can help patients to manage their own disease, offering support as patients strive to find solutions to their own individual challenges.

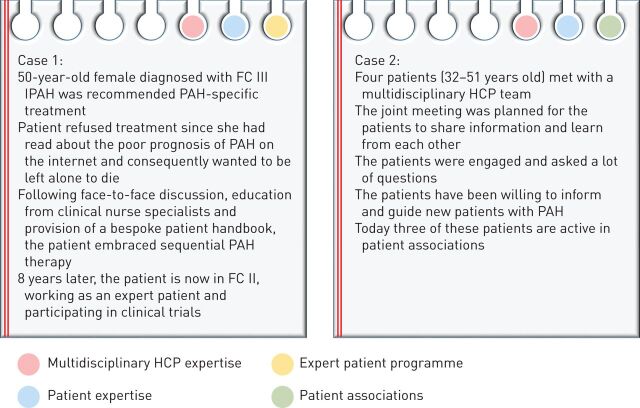

Incorrect or inappropriate information may lead to misconceptions and the patient becoming passive in their self-care. Online material on PAH may carry with it a particularly high risk of misinformation. Case 1 in figure 3 is a real-life example where initial information obtained from the internet led a woman with PAH to refuse treatment. Following the provision of correct information and relevant education, the patient embraced sequential therapy. Many years later she remains engaged, involved in her own care and helps others in the management of their disease.

FIGURE 3.

Real-life pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) patient cases to reflect the importance of a collaborative approach to patient engagement. Case 1 reflects the importance of accurate information being given to the patient at the time of PAH diagnosis. Case 2 reflects the value of shared patient appointments, indicating how different approaches can benefit different patients. The coloured circles represent the elements of the collaborative approach to patient engagement used in each of the cases. FC: functional class; HCP: healthcare professional; IPAH: idiopathic PAH.

Patients differ in their preferred way of learning and, therefore, the dissemination of information needs to match the individual [27]. Some patients prefer reading at home rather than being overwhelmed during visits with HCPs. Some may need time to process information before asking questions at a later stage while others may require immediate answers at appointments. Patients may prefer the approach of shared medical appointments, where several patients are invited to meet with the multidisciplinary team in a group setting. This can allow PAH patients to increase their understanding of the disease, while integrating peer support, promoting social interaction and addressing patients' emotional needs [29]. Case 2 in figure 3 is an example of how shared appointments contributed to patient engagement with their disease. This led to participation in patient associations by some of those in the group.

Awareness of a patient's health literacy is integral to patient care, safety, education and counselling [30]. Health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information and services needed to make informed health decisions [31]. Patient health literacy can easily be overestimated [30] and care must be taken to ensure patients understand the information they are given.

Role of HCPs

The first contact with a HCP provides an opportunity for the PAH patient to talk and ask questions, whilst allowing the HCP to gain an understanding of the patient's needs in terms of education and information. Too much information can often be overwhelming [5] and patients may vary in the degree to which they benefit from participation in patient education due to disease burden, literacy levels and socioeconomic factors [32]. HCPs must gauge what level of information is appropriate and how much information the patient is able to process and retain at different stages of their disease. Notably, there are often differences between the expectations of the patient and those of the HCP in terms of PAH management. While expectations of HCPs tend to focus on functional aspects of PAH, patients' expectations tend to focus on the effect on overall QoL, treatment convenience and the physiological and physical impact on their lives [7, 33]. There is increasing use of health-related QoL assessments and questionnaires in clinical practice, designed to assess patients' symptoms and function, as well as other patient-related measures [2, 34]. These tools can be used to help HCPs better understand the needs of individual patients [34] and stimulate discussion about aspects of patients' lives other than those which are purely physiological [7, 33], such as exercise capacity and optimising right ventricular function.

Management of PAH patients in expert referral centres with a specialist team is beneficial as it ensures that regular contact with HCPs, including clinical pulmonary hypertension nurse specialists, is maintained [2–4]. Even with the availability of regional satellite clinics, it is preferable for patients to maintain regular contact with PAH expert referral centres and not to be seen exclusively in a satellite clinic. Patients would like more opportunities to discuss their disease and its impact on everyday life with HCPs [5, 6] and to be continuously updated by them [6]. In a multidisciplinary team, different HCPs have complementary roles and follow-up and long-term support of patients is shared with local HCPs [2], who in turn should be well-informed about PAH and maintain a constant dialogue with specialist pulmonary hypertension centres [2].

It is the responsibility of all HCPs to make sure the patient understands the information that is being delivered. Healthcare team members should receive training on how to better engage patients to participate in their own care, including communication skills, making shared decisions and understanding patient information needs [10]. It is also important to ensure that some members of a team delivering pulmonary hypertension care are trained in health coaching, since this can help patients gain a better understanding of their goals, how to achieve them and how to engage in the management of their chronic condition [35]. Incorporation of an awareness of oral and aural literacy into community programmes and healthcare provider education and training is also recommended [36]. For patients to adhere to a treatment plan, they must understand basic information about the tasks for which they are responsible. If this information is not presented clearly using language the patient can easily understand, it can compromise patients' agreement, motivation and commitment [37]. In this respect, patients may also benefit from receiving information from a variety of HCPs because each individual may convey information differently. The “teach back” tool is often used in specialised centres to evaluate HCPs on their delivery of information to the patient [38]. With this tool, patients have to re-transcribe the information delivered, such as instructions for medication use or a description of a proposed procedure, to ascertain whether they have understood correctly [39]. Another method of delivering information is via web-based forums that are designed for PAH patients, where specialists answer patient questions [6]. HCPs can also learn about the patient experience, in order to better tailor how they deliver information and care to patients, through observing patients in group discussion (e.g., the “Goldfish Bowl” model) [40].

A number of practical solutions have been developed to promote patient engagement and empower them to take ownership of their disease. These include tools such as “information prescriptions”, written care plans, patient “passports”, self-management courses, patient-to-patient mentoring and the promotion of patient associations [10] (table 1). These tools allow the delivery of high-quality information in a way that is tailored to the needs of the individual, providing education and support to the PAH patient. A holistic approach, incorporating training for HCPs, can further enhance patient engagement [10].

TABLE 1.

Practical solutions for a holistic approach to the engagement of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) patients

| Practical solution | Considerations for implementing practical solutions |

| Training for HCPs and other multidisciplinary team members | The benefits of patient engagement and self-management |

| How to work collaboratively with patients to motivate them to participate in their own care | |

| Communicating with patients using language that is easy for them to understand | |

| Helping patients to understand and communicate their fears and establish their own goals | |

| Managing the broader aspects of PAH beyond the physical symptoms | |

| Understanding the support and services available from patient associations | |

| Specific training for HCPs in shared care centres | |

| “Information prescriptions” | To integrate high-quality information into the healthcare pathway in a way that is tailored to the needs of the individual |

| Information could be selected by the HCP and “prescribed” on the basis of the individual patient's needs, goals and the stage of their journey since diagnosis | |

| This may include information on PAH and its management including the broader aspects of the disease beyond physical symptoms, as well as referral to a local patient group | |

| Written care plans | Record of information about the patient's care, which they can refer back to between consultations |

| Helps the patient understand that there are a variety of options available to them | |

| Encourages the patient to consider their role in their own care | |

| Emphasises the importance of collaboration and shared decision making between the patient and HCP | |

| Helps patients to communicate with local family doctors and HCPs in shared care centres | |

| Patient “passports” | A digital or hard copy patient “passport” may be very useful for both patient self-management and as a central record to improve information sharing between the multidisciplinary team |

| May contain information on the disease, available treatments and written care plan, a record of test results, information on self-care and the broader aspects of the disease, and where to go for support | |

| Helps patients to communicate with local family doctors and HCPs in shared care centres | |

| Patient self-assessment and management tools | May be developed to assist patients in accessing information that is relevant to them and their individual situations. Could be in the form of patient “diaries” |

| Patient self-management courses | Can be offered by the multidisciplinary team to educate and activate patients early following the diagnosis of PAH |

| Patient-to-patient mentoring | May provide patients with individualised support, particularly with regards to the broader aspects of PAH beyond the physical symptoms |

| Patients could be matched according to factors such as age and cultural background | |

| Could take the form of chronic disease self-management programmes where a patient with chronic disease is involved in leading the workshop, providing advice and support to patients attending on how to best manage their disease [41] | |

| Promoting patient associations | Training HCPs on the services available so that they can act as a conduit to these services for patients |

| Training patient association members in marketing skills and activities via social media and traditional routes to raise the profile and visibility of patient associations among PAH patients |

Data from [10].

Role of patient associations

More than half of PAH patients and one-third of their carers feel socially isolated, due to a lack of understanding of the disease among family, friends and the general public [5]. Patient associations are a valuable asset in the management of PAH patients and provide support to HCPs in promoting patient engagement. Patient associations provide opportunities for networking, meetings and social activities. They also support patient advocacy and provide helplines, message boards and social media channels. They have developed a wealth of information on PAH, exemplified by the Pulmonary Hypertension Library, which contains over 200 resources with materials available in many languages for HCPs and patients to browse [42]. In a quantitative survey of PAH patients, patient associations emerged as one of the most useful sources of information for patients, with 66% of patients utilising them [5]. The majority of the patients interviewed as part of this survey were members of a patient association [5].

Clinical PAH guidelines, including the latest ESC/ERS guidelines, recommend that patients be encouraged to contact patient associations [3, 4]. Despite this, the aforementioned survey revealed that only 45% of patients had been referred to these patient associations by a specialist [5, 43]. As PAH patients often seek out patient associations at the time of diagnosis [43], patients and carers should be directed to these organisations soon after this point [5].

Maintaining close links and effective communication between patient associations and the multidisciplinary healthcare teams ensures that services, support and resources are optimally coordinated. For patients who do not want to contact patient associations, their decision should be respected and support given regarding whether any further sources of information are required.

Role of carers

Carers play a key role in supporting PAH patients with the management of their disease and with their everyday physical and emotional needs [5, 43]. To encourage carers to be engaged, they too should be provided with timely information and support [5, 43]. Most carers reportedly receive either limited or no written information about PAH from HCPs at diagnosis, which leads to many unanswered questions [43]. However, as a group, carers are often more proactive than patients at obtaining information from a range of sources [43]. By spending time with patients on a daily basis, carers are in a strong position to help and encourage patients to engage in self-management of their disease. The need to include carers as important stakeholders in the care provided to patients with PAH is thus recognised [43].

Role of expert patients

The concept of an “expert patient” is gaining increasing importance in healthcare policy and delivery [44]. Expert patient programmes are run by patient organisations to develop the confidence and skills of people with chronic illnesses [45, 46]. They work together with HCPs and other health stakeholders to improve patients' QoL [45, 46]. As patients become experts in managing their chronic disease, their experience and knowledge can be used to encourage others to become decision makers in their treatment process and to further improve health services [47]. In PAH, expert patients can participate in working groups and mentor newly diagnosed patients, further encouraging patient engagement. As self-management of chronic diseases becomes increasingly recognised, the role of expert patients may continue to grow [47].

Future perspectives

There is growing public interest in digital health, not only to record and obtain information but also to access electronic health records, conduct virtual HCP consultations and order repeat prescriptions [48]. Home-based, mobile and wearable technologies are becoming more widely available, which could impact on patient engagement and self-management of their disease [49, 50]. Many patients already use technology to monitor and manage their health. Apps and mobile devices that measure and track health data have the potential to impact patient engagement and create increased awareness to reinforce beneficial lifestyle choices [49]. The validity and reliability of measurements needs to be established and challenges in adherence, privacy and clinical measurement need to be addressed before these devices are broadly adopted [49]. For PAH, technology that measures energy consumption or adherence to treatment might lead to advances in patient self-care, and input from patients on the development of mobile devices would ensure they are user-friendly and enable patients to benefit in the best way possible.

Conclusion

Advancing knowledge and treatment options in PAH have improved the outlook for PAH patients, making PAH a disease that patients can live with over the long term. Improved long term outcomes in PAH patients mean that patient needs have evolved beyond those of treatment of symptoms and managing disease progression. A holistic approach is now coming to the front of PAH management which places the patient at the centre of their own healthcare. Patient engagement relies on the active collaboration between patients, HCPs and other stakeholders rather than the patient being a passive recipient of their care. Multidisciplinary expert teams are essential and should include psychosocial support for the patient. Patient associations are also a valuable resource for educational and emotional support for patients and carers and play an essential role in patient care. In addition, expert patients are emerging as sources of expertise and understanding to further encourage patient engagement. Tailored support and education, shared decision making and support of self-care are some of the ways that patient engagement can be achieved.

Disclosures

L. Howard ERR-0078-2016_Howard (1.2MB, pdf)

J. Graarup ERR-0078-2016_Graarup (1.2MB, pdf)

P. Ferrari ERR-0078-2016_Ferrari (1.2MB, pdf)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Kat Karolemeas (nspm Ltd, Meggen, Switzerland) for medical writing assistance, funded by Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd (Allschwil, Switzerland).

Footnotes

Editorial comment in Eur Respir Rev 2016; 25: 361–363.

Conflict of interest: Disclosures can be found alongside this article at err.ersjournals.com

Provenance: The European Respiratory Review received sponsorship from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Allschwil, Switzerland, for the publication of these peer-reviewed articles.

References

- 1.Benza RL, Miller DP, Barst RJ, et al. An evaluation of long-term survival from time of diagnosis in pulmonary arterial hypertension from REVEAL. Chest 2012; 142: 448–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gin-Sing W. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: a multidisciplinary approach to care. Nurs Stand 2010; 24: 40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J 2016; 37: 67–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2015; 46: 903–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guillevin L, Armstrong I, Aldrighetti R, et al. Understanding the impact of pulmonary arterial hypertension on patients' and carers' lives. Eur Respir Rev 2013; 22: 535–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ivarsson B, Ekmehag B, Sjoberg T. Information experiences and needs in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension or chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Nurs Res Pract 2014; 2014: 704094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alami S, Cottin V, Mouthon L, et al. Patients', relatives', and practitioners' views of pulmonary arterial hypertension: a qualitative study. Presse Med 2016; 45: e11–e27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellins J, Coulter A. How engaged are people in their health care? Findings of a national telephone survey. London, Picker Institute Europe, 2005. Available from: www.pickereurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/How-engaged-are-people-in-their-health-care-....pdf. Date last accessed: July 2016. Date last updated: November 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, et al. Development of the patient activation measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res 2004; 39: 1005–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd. A holistic approach to patient care in pulmonary arterial hypertension. 2016. Available from: www.phaeurope.org/wp-content/uploads/Holistic-Care-in-PAH-report-FINAL-25.01.16.pdf. Date last accessed: July 2016. Date last updated: January 2016.

- 11.Greene J, Hibbard JH, Sacks R, et al. When patient activation levels change, health outcomes and costs change, too. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015; 34: 431–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, et al. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013; 32: 223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barello S, Triberti S, Graffigna G, et al. eHealth for patient engagement: a systematic review. Front Psychol 2015; 6: 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aujoulat I, d'Hoore W, Deccache A. Patient empowerment in theory and practice: polysemy or cacophony? Patient Educ Couns 2007; 66: 13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hibbard JH, Mahoney E. Toward a theory of patient and consumer activation. Patient Educ Couns 2010; 78: 377–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Philips J. The need for an integrated approach to supporting patients who should self-manage. Self Care 2012; 3: 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eriksson M, Lindstrom B. Antonovsky's sense of coherence scale and the relation with health: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006; 60: 376–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barello S, Graffigna G, Vegni E, et al. The challenges of conceptualizing patient engagement in health care: a lexicographic literature review. 2014; 6: e9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coulter A, Ellins J. Effectiveness of strategies for informing, educating, and involving patients. BMJ 2007; 335: 24–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ivarsson B, Ekmehag B, Hesselstrand R, et al. Perceptions of received information, social support, and coping in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension or chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Clin Med Insights Circ Respir Pulm Med 2014; 8: 21–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner A, Anderson JK, Wallace LM, et al. An evaluation of a self-management program for patients with long-term conditions. Patient Educ Couns 2015; 98: 213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.White J, Hopkins RO, Glissmeyer EW, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and quality of life outcomes in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Respir Res 2006; 7: 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsangaris I. Improving patient care in pulmonary arterial hypertension: addressing psychosocial issues. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2014; 16: 159–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farber HW, Gin-Sing W. Practical considerations for therapies targeting the prostacyclin pathway. Eur Respir Rev 2016; 25: 000–000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poms AD, Turner M, Farber HW, et al. Comorbid conditions and outcomes in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: a REVEAL registry analysis. Chest 2013; 144: 169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olsson K, Channick R. Pregnancy in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir Rev 2016; 25: 000–000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Archer-Chicko C. Nursing Care of Patients with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. In Textbook of Pulmonary Vascular Disease. 1st edn. Yuan JXJ, Garcia JGN, Hales CA, et al. New York, Springer Science+Business Media, 2011; pp. 1531–1558. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Armstrong I, Harries C. Patient information that promotes health literacy. Nurs Times 2013; 109: 23–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahaghi FF, Chastain VL, Benavides R, et al. Shared medical appointments in pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ 2014; 4: 53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dickens C, Lambert BL, Cromwell T, et al. Nurse overestimation of patients' health literacy. J Health Commun 2013; 18: Suppl 1: 62–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parker RM, Ratzan SC, Lurie N. Health literacy: a policy challenge for advancing high-quality health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2003; 22: 147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Varming AR, Torenholt R, Moller BL, et al. Addressing challenges and needs in patient education targeting hardly reached patients with chronic diseases. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2015; 19: 292–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howard LS, Ferrari P, Mehta S. Physicians' and patients' expectations of therapies for pulmonary arterial hypertension: where do they meet? Eur Respir Rev 2014; 23: 458–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKenna SP, Doughty N, Meads DM, et al. The Cambridge Pulmonary Hypertension Outcome Review (CAMPHOR): a measure of health-related quality of life and quality of life for patients with pulmonary hypertension. Qual Life Res 2006; 15: 103–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bennett HD, Coleman EA, Parry C, et al. Health coaching for patients with chronic illness. Fam Pract Manag 2010; 17: 24–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nouri SS, Rudd RE. Health literacy in the “oral exchange”: an important element of patient-provider communication. Patient Educ Couns 2015; 98: 565–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gerwing J, Indseth T, Gulbrandsen P. A microanalysis of the clarity of information in physicians' and patients' discussions of treatment plans with and without language barriers. Patient Educ Couns 2016; 99: 522–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teach back training toolkit. 2016. Available from: www.teachbacktraining.org. Date last accessed: July 2016. Date last updated: 2016.

- 39.National Center for Ethics in Healthcare. “Teach back” a tool for improving provider-patient communication. 2006. Available from: www.ethics.va.gov/docs/infocus/Infocus_20060401_teach_back.pdf. Date last accessed: July 2016. Date last updated: April 2016.

- 40.Goldfish bowl technique. 2016. Available from: www.gp-training.net/training/vts/group/goldfish.htm. Date last accessed: July 2016. Date last updated: February 2016.

- 41.Stanford Patient Education Research Center. Chronic Disease Self-Management Program. Stanford, CA, 2016. Stanford School of Medicine. Available from: http://patienteducation.stanford.edu/programs/cdsmp.html. Date last accessed: July 2016. Date last updated: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 42.PHA Europe & PHA US. Our PH library. A global resource for the PH community. 2016. Available from: www.ourphlibrary.com. Date last accessed: July 2016.

- 43.PHA Europe. The impact of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) on the lives of patients and carers: results from an international survey. 2012. Available from: www.phaeurope.org/wp-content/uploads/PAH_Survey_FINAL.pdf. Date last accessed: July 2016. Date last updated: September 2012.

- 44.Fox J. The role of the expert patient in the management of chronic illness. Br J Nurs 2005; 14: 25–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fitzpatrick M. Expert patients? Br J Gen Pract 2004; 54: 405. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shaw J, Baker M. “Expert patient”–dream or nightmare? BMJ 2004; 328: 723–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tattersall RL. The expert patient: a new approach to chronic disease management for the twenty-first century. Clin Med (Lond) 2002; 2: 227–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Corrie C, Finch A. Expert patients. London, Reform, 2015. Available from: www.reform.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Expert-patients.pdf. Date last accessed: July 2016. Date last updated: February 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chiauzzi E, Rodarte C, DasMahapatra P. Patient-centered activity monitoring in the self-management of chronic health conditions. BMC Med 2015; 13: 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Milani RV, Bober RM, Lavie CJ. The role of technology in chronic disease care. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2016; 58: 579–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

L. Howard ERR-0078-2016_Howard (1.2MB, pdf)

J. Graarup ERR-0078-2016_Graarup (1.2MB, pdf)

P. Ferrari ERR-0078-2016_Ferrari (1.2MB, pdf)