To the Editor:

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) is the most severe delayed complication after pulmonary embolism. Known risk factors of CTEPH include acute pulmonary embolism, the degree of pulmonary arterial occlusion, pulmonary embolism recurrence, splenectomy, ventriculo-arterial shunts, infected pacemakers and blood group O [1, 2]. Symptomatic pulmonary embolism is found in almost three-quarters of patients with CTEPH [3]. Cyproterone acetate, a synthetic steroidal antiandrogen drug with additional progestogen and antigonadotropic properties, is a major risk factor of venous thromboembolic disease [4, 5]. We report the first case of severe CTEPH occurring in the context of cyproterone acetate long-term exposure.

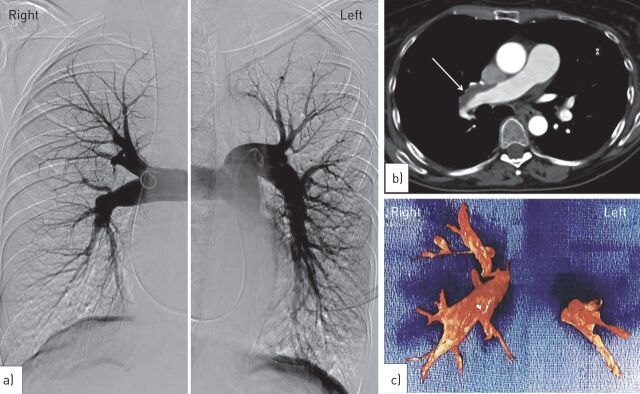

A 55-year-old female was referred to our centre (French referral centre for pulmonary hypertension) for pulmonary hypertension. She was a former smoker (30 pack-years) and her medical history included migraine, systemic hypertension and severe acne (treated with cyproterone acetate, 50 mg daily) between 1992 and 2010 associated with ethinylestradiol therapy. The patient had no past history of pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis. No risk factors for CTEPH other than cyproterone acetate exposure were identified. In 2010, the patient reported exertional dyspnoea and cyproterone acetate was stopped. The patient experienced progressive dyspnoea during the following 18 months, and the patient was in New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class III at the time of the first evaluation. Pulmonary hypertension was suspected on Doppler echocardiography and right heart catheterisation confirmed severe pre-capillary pulmonary hypertension with a mean pulmonary arterial pressure of 52 mmHg, a normal pulmonary artery wedge pressure, a low cardiac index of 1.76 L·min−1·m-2, an increased total pulmonary resistance of 19.6 Wood Units (WU), and a low mixed venous oxygen saturation of 51%. Her 6-min walk distance was 265 m. A ventilation/perfusion lung scan showed multiple bilateral perfusion defects with normal ventilation. Helical computed tomography of the chest and pulmonary angiogram (fig. 1a and b) confirmed the diagnosis of CTEPH with bilateral proximal obstruction of the pulmonary arteries. Pulmonary endarterectomy was successfully performed allowing removal of organised material (fig. 1c). Evolution was favourable with a decrease of total pulmonary resistance to 6 WU immediately after surgery. 2 years after surgery the patient showed persistent clinical benefit (NYHA functional class I).

Figure 1.

a) Selective pulmonary angiogram of the right and left main pulmonary arteries confirmed the diagnosis of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension with bilateral proximal obstruction of the pulmonary arteries. b) Computed tomography of the chest showing organised thromboembolic material in the main right pulmonary artery (arrow). c) Organised thromboembolic material removed during pulmonary endarterectomy.

We report the first case of CTEPH potentially associated with long-term exposure to cyproterone acetate. This antiandrogen therapy, widely used in the field of oncology for the treatment of prostatic neoplasia (100–300 mg·day−1), is a major risk factor of pulmonary embolism in males with prostatic neoplasia [6]. Lower doses of cyproterone acetate (2–100 mg·day−1) are commonly used outside the oncological setting, and cyproterone acetate has been proposed for the management of severe acne and hirsutism, reduction of sexual pulsion and as a method of birth control, in addition to ethinylestradiol [7]. Even at these lower doses (2 mg·day−1), cyproterone acetate is still associated with high risks of venous thromboembolic disease (seven-fold increased risk) [4, 7]. It is worth noting that, this risk increases with the duration of exposure and with the patient’s age [4]. Due to this, the Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee of the European Medicines Agency (EMEA) recently reviewed the risk/benefit ratio of this drug, particularly the association of cyproterone acetate (2 mg)/ethinylestradiol (35 μg), which is widely used across Europe for the treatment of acne or as oral contraception. The EMEA maintained that these drugs could be used in the treatment of moderate-to-severe acne related to androgen sensitivity and/or hirsutism in females of reproductive age, but only after topical therapy or systemic antibiotic treatments failed [8]. Due to the fact that these drugs act as hormonal contraceptives, they cannot be used in combination with other hormonal contraceptives [8]. Notably, hormonal therapy is not recognised as a usual risk factor for CTEPH [2, 3, 9]. However, the present case indicates that long-term exposure to a high dose of cyproterone acetate may be a risk factor for CTEPH. As previously emphasised in pulmonary arterial hypertension [10–12], complete information on drug exposure should be systematic in patients presenting with CTEPH in order to identify as yet unrecognised possible drug-induced cases. Several drugs have been recognised recently as being associated with an increased risk of pulmonary arterial hypertension, e.g. dasatinib in patients with chronic myelogenous leukaemia. Beside its role in thrombosis, cyproterone acetate should also be recognised as an increased risk factor of CTEPH. Thus, clinicians should also consider chronic venous thromboembolism as CTEPH in patients exposed to cyproterone acetate.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Support Statement: The French Pulmonary Hypertension Pharmacovigilance Network (VIGIAPATH) is supported by the Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament et des Produits de Santé (ANSM).

Conflict of interest: Disclosures can be found alongside the online version of this article at err.ersjournals.com

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Lang IM, Pesavento R, Bonderman D, et al. Risk factors and basic mechanisms of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: a current understanding. Eur Respir J 2013; 41: 462–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonderman D, Wilkens H, Wakounig S, et al. Risk factors for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2009; 33: 325–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pepke-Zaba J, Delcroix M, Lang I, et al. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH): results from an international prospective registry. Circulation 2011; 124: 1973–1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Hylckama Vlieg A, Helmerhorst FM, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The venous thrombotic risk of oral contraceptives, effects of oestrogen dose and progestogen type: results of the MEGA case-control study. BMJ 2009; 339: b2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Hylckama Vlieg A, Middeldorp S. Hormone therapies and venous thromboembolism: where are we now? J Thromb Haemost 2011; 9: 257–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Hemelrijck M, Adolfsson J, Garmo H, et al. Risk of thromboembolic diseases in men with prostate cancer: results from the population-based PCBaSe Sweden. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11: 450–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lidegaard O, Nielsen LH, Skovlund CW, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism from use of oral contraceptives containing different progestogens and oestrogen doses: Danish cohort study, 2001–9. BMJ 2011; 343: d6423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Medicines Agency. Benefits of Diane 35 and its generics outweigh risks in certain patient groups. www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/referrals/Cyproterone-_and_ethinylestradiol-containing_medicines/human_referral_prac_000017.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac05805c516f Date last updated: August 5, 2013. Date last accessed: February 26, 2014.

- 9.Lang IM, Simonneau G, Pepke-Zaba JW, et al. Factors associated with diagnosis and operability of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. A case-control study. Thromb Haemost 2013; 110: 83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montani D, Bergot E, Günther S, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients treated by dasatinib. Circulation 2012; 125: 2128–2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Savale L, Chaumais MC, Cottin V, et al. Pulmonary hypertension associated with benfluorex exposure. Eur Respir J 2012; 40: 1164–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Souza R, Humbert M, Sztrymf B, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with fenfluramine exposure: report of 109 cases. Eur Respir J 2008; 31: 343–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.