ABSTRACT

Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models have gained in popularity in the last decade in both drug development and regulatory science. PBPK models differ from classical pharmacokinetic models in that they include specific compartments for tissues involved in exposure, toxicity, biotransformation, and clearance processes connected by blood flow. This study aimed to address the gaps between the mathematics and pharmacology framework observed in the literature. These gaps included nonconserved systems of equations and compartment concentration that were not biologically relatable to the tissues of interest. The resulting system of nonlinear differential equations is solved numerically with various methods for benchmarking and comparison. Furthermore, a sensitivity analysis of all parameters were conducted to elucidate the critical parameters of the model. The resulting model was fit to clinical data as a performance benchmark. The clinical data captured the second line of antiretroviral treatment, lopinavir and ritonavir. The model and clinical data correlate well for coadministration of lopinavir/ritonavir with rifampin. Drug-drug interaction was captured between lopinavir and rifampin. This article provides conclusions about the suitability of physiologically based pharmacokinetic models for the prediction of drug-drug interaction and antiretroviral and anti-TB pharmacokinetics.

KEYWORDS: pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics

INTRODUCTION

Mathematical models for the treatment of disease need to consider both what the drug does to the body (pharmacodynamics) and what the body does to the drug (pharmacokinetics) (1). Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models form a powerful modeling device for capturing pharmacokinetics in the human body. The resulting models comprise a system of many nonlinear differential equations rendering exact solutions intractable. As such, numerical methods are employed to simulate the dynamics of these models. Using this framework, this study examines the suitability of PBPK models to capture pharmacodynamics for drug regimes pertaining to human immunodeficiency virus and tuberculosis infections by validating the model with clinical data.

Chronic diseases are associated with pathophysiological changes that may influence the pharmacokinetics of the drug, which could lead to a potential need to change administered drug therapy (2). A variety of responses associated with antiretroviral (ARV) agents may lead to multiple factors such as poor adherence to therapy, immunological status, and pharmacokinetics exposure to the ARV drugs (3). Viral suppression is evidence of the pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationship. The plasma concentration of ARV treatment is influenced by absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination (ADME) processes, which take place in several tissues and are mediated by numerous proteins (4). Drug-drug interaction (DDI) occurs between different ARV treatment due to the fact that the treatment is an inducer and an inhibitor of metabolic enzyme and transporter and may also be due to exposure to other concomitant drugs (3). The efficacy of modern ARV therapy has been to prolong the lives of HIV-infected individuals. Most of the ARV treatment is orally administered, and oral bioavailability can be influenced by several factors defining the fraction of dose available for absorption and first-pass metabolism (3). The oral bioavailability could be evaluated using compartmental absorption and the transit model, which estimates the fraction of the dose absorbed and the rate of drug absorption (3). In cases where the HIV-infected individual is also coinfected with other infectious diseases such as tuberculosis (TB), malaria and hepatitis, the ARV treatment is required to be coadministered with other anti-infective agents (3, 4). Coadministration of multiple drugs increases the prevalence of DDI (5). Drug coadministration changes the ADME properties of the drugs, which leads to pharmacokinetics DDI, which often involves inhibition or induction of drug-metabolizing enzymes, transporter, or even both (5). Therefore, the assessment of potential pharmacokinetic DDIs is essential for rational therapeutics (4, 5), as DDI complicates the understanding of the pathophysiological aspects traditionally addressed in mathematical pharmacology (1).

The physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model maps drug movements in the body to a physiologically realistic compartment structure using sets of differential equations (6). The first PBPK model, developed by Torsten Teorell in 1937, accounted for various processes affecting drug disposition around the body (6). However, for many years the PBPK model’s application was mainly related to environmental toxicology research (7). The concentration of an administered drug in the body can be determined by the study of pharmacokinetics (7). The PBPK model makes use of an abundance of information, content compared to the empirical model in terms of the anatomy, and physiology of the underlying system and, consequently, predicts drug exposure in inaccessible tissues and its toxicity (7). The primary advantage of the PBPK model is that it provides a rationale to extrapolate not only from one animal species to the other, but also from animals to humans and special populations such as pediatric and a complex scenario such as DDI (7). Physiologically based models are systems of differential equations that involve a number of parameters obtained from different research fields. These parameters can be classified as system related (e.g., blood flow, organ volumes) and drug related (e.g., intrinsic metabolic clearance). These related parameter values can be obtained from published studies (7). Moreover, as the difficulties of the PBPK models increase, it is essential to have more sophisticated system-related parameters. However, determination of these system-related parameters becomes challenging. Nevertheless, drug-related parameters are derived from the in vitro experimental data, which are only limited to the first stage of the drug development and carry some level of uncertainty (7), while the in vivo parameters are determined through simulation and calibration or from available in vivo data. A number of drug labels are informed by simulation results generated using PBPK models.

The main contributions of this paper include the presentation of a conservative mathematical model, ensuring that there is no drug loss in a manner that is not explicitly modeled. Additionally, we benchmark the efficacy of three different numerical schemes and report their appropriateness for multicompartment PBPK models. Finally, through a sensitivity analysis and fitting to clinical data, we identify the parameters of the model that are most sensitive to calibration. This informs our analysis of the best-fit parameter values against those that are reported in the literature from clinical studies.

RESULTS

Numerical simulations were carried out using the mathematical software Mathematica. Parameter values used were obtained from published papers. The model parameter values in this section and their sources are given in Table 1 and 2. All the parameters that were not available in reference 8 were adopted from the anti-TB literature to carry out the simulation due to lack of available data. Finally, we performed parameter sensitivity analysis to test the sensitivity of the system to each of these parameters. Sensitive parameters could influence solutions significantly.

TABLE 1.

Partition coefficient

| From literature (28) |

From literature (28) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mice |

Human |

||||

| Description | Parameter | Prior | Posterior | Posterior | Mice |

| Bone | N(28.3, 0.2)a | N(27.33, 0.18) | N(27.33, 0.18) | 94.00 | |

| Brain | N(5.93, 0.2) | N(5.81, 0.17) | N(5.81, 0.17) | 2.00 | |

| Gut | N(42.1, 0.2) | N(38.69, 0.18) | N(38.69, 0.18) | 123.00 | |

| Heart | N(63.9, 0.2) | N(62.02, 0.18) | N(62.02, 0.18) | 15.00 | |

| Kidney | N(43.5, 0.2) | N(43.22, 0.17) | N(87.47, 0.17) | 72.00 | |

| Liver | N(183.3, 0.2) | N(164.21, 0.18) | N(164.21, 0.18) | 114.00 | |

| Lung | N(48.9, 0.2) | N(48.48, 0.17) | N(48.48, 0.17) | 39.00 | |

| Muscle | N(38.1, 0.2) | N(37.39, 0.17) | N(37.39, 0.17) | 9.00 | |

| Skin | N(43.5, 0.2) | N(43.22, 0.17) | N(43.22, 0.17) | 14.00 | |

| Spleen | N(49.9, 0.2) | N(49.71, 0.17) | N(49.71, 0.17) | 216.00 | |

| Carcass | N(28.3, 0.2) | N(29.04, 0.18) | N(29.04, 0.18) | 93b | |

N(a, b) denotes a normal distribution with a mean of a and fractional coefficient of variation (CV).

Carcass partition coefficient is equal to median of all tissue partition coefficient.

TABLE 2.

Physiological parameters

| From literature (28) |

From literature (8) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description | Parameter | Mouse | Human | Distribution | CV | Mouse | Human | Distribution |

| Bone | 0.1220 | 0.0500 | N | 0.3 | 0.1200 | 0.0500 | N | |

| 0.07300 | 0.1429 | N | 0.2 | 0.0415 | 0.0856 | N | ||

| Brain | 0.0200 | 0.1200 | N | 0.3 | 0.0200 | 0.1200 | N | |

| 0.0057 | 0.0200 | N | 0.2 | 0.0057 | 0.0200 | N | ||

| Gut | 0.1400 | 0.1400 | N | 0.3 | 0.1310 | 0.1700 | N | |

| 0.0270 | 0.0171 | N | 0.2 | 0.0270 | 0.0171 | N | ||

| Heart | 0.0490 | 0.0450 | N | 0.3 | 0.0490 | 0.0400 | N | |

| 0.0033 | 0.0047 | N | 0.2 | 0.0033 | 0.0047 | N | ||

| Kidney | 0.1410 | 0.1800 | N | 0.3 | 0.1410 | 0.1900 | N | |

| 0.0073 | 0.0044 | N | 0.2 | 0.0073 | 0.0044 | N | ||

| Hepatic artery | 0.0240 | 0.0600 | N | 0.3 | 0.1750 | 0.2500 | N | |

| Liver | 0.0366 | 0.0257 | N | 0.2 | 0.0366 | 0.0257 | N | |

| Cardiac output | 14.100 | 16.200 | N | 0.3 | 14.100a | 16.500a | N | |

| Lung | 0.0050 | 0.0076 | N | 0.2 | 0.0050 | 0.0076 | N | |

| Muscle | 0.2780 | 0.1450 | N | 0.3 | 0.2780 | 0.1700 | N | |

| 0.4043 | 0.4000 | N | 0.2 | 0.4040 | 0.4000 | N | ||

| Skin | 0.0580 | 0.0500 | N | 0.3 | 0.0580 | 0.0500 | N | |

| 0.1903 | 0.0371 | N | 0.2 | 0.1900 | 0.0371 | N | ||

| Spleen | 0.0100 | 0.0100 | N | 0.3 | 0.0200 | 0.0200 | N | |

| 0.0020 | 0.0026 | N | 0.2 | 0.0020 | 0.0026 | N | ||

| Carcass | 0.0880 | 0.1325 | N | 0.3 | 0.0763 | 0.0693 | N | |

| 0.1015 | 0.0448 | N | 0.2 | 0.1100 | 0.1885 | N | ||

| Stomach | 0.0010b | 0.0010b | ||||||

| Arterial blood | 0.0493 | 0.0526 | N | 0.2 | 0.0272 | 0.0257 | N | |

| Venous blood | 0.0247 | 0.0263 | N | 0.2 | 0.0544 | 0.0514 | N | |

| Gut reabsorption rate | 0.1700 | 0.1700 | L | 0.3 | ||||

| Drug absorption rate | 0.3100 | 0.3000 | L | 0.3 | 0.8600c | L | ||

| Gut lumen transit rate | 0.6000d | 0.6000d | L | 0.3 | ||||

| Fractional renal clearance | 0.1900 | 0.1300 | L | 0.3 | ||||

| Fractional drug absorption | 1.0000 | 1.000 | C | N/A | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | C | |

| Total blood clearance | 0.74 | 0.64 | N | e | ||||

| Maximum rate of metabolism | 0.91 | |||||||

| Michaelis-Menten constant | 34.29 | |||||||

L, lognormal; C, constant; N, normal. Lung blood flow was obtained from Brown et al. (38).

The volume of stomach was assumed.

Drug absorption rate was obtained from Siccardi et al. (3).

The gut lumen transit rate was obtained from Lyons et al. (29).

The coefficient of variation for human and mouse were different, the CV for humans was 0.18 while the CV for mice was 0.31.

The most preferred ARV oral treatment (single tablet regimen) is a combination of three drugs; tenofovir (300 mg), efavirenz (600 mg), and emtricitabine (200 mg) or any regimen that contains the first-line therapy for HIV drug susceptibility. For the simplicity of our numerical simulation, we only chose to capture efavirenz and to make the drug dose and drug schedule more realistic. We assumed that an HIV-infected individual received 600 mg of efavirenz once daily. Furthermore, we assumed that an TB-infected individual received rifampicin also known as rifampin (600 mg) daily. In most studies where rifampin was used alone in preventive treatment of latent TB, a low risk of drug-induced liver injury (DILI) was observed due to the use of rifampin (9).

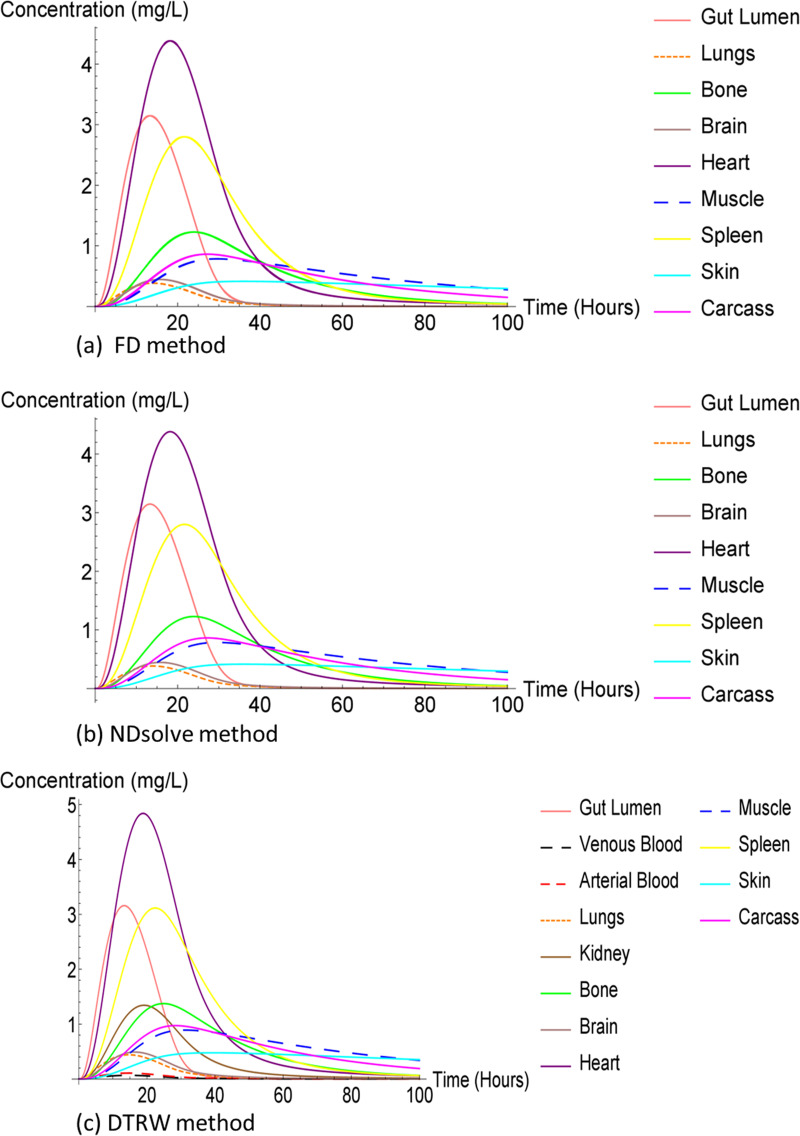

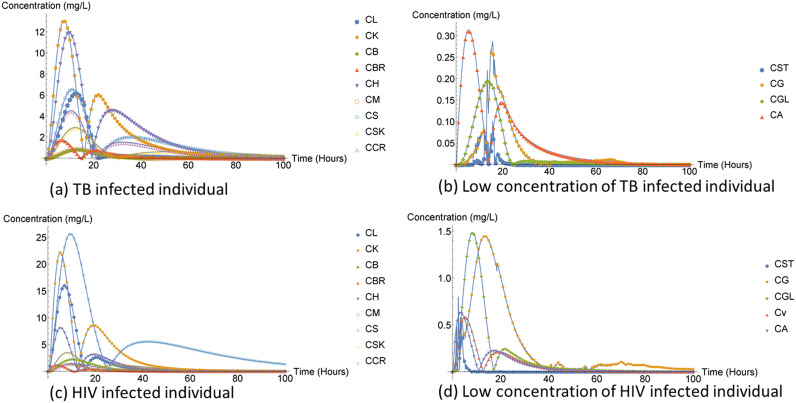

We used the NDsolve method as our third numerical method to solve our ODE system, which does not have an analytical solution. The NDsolve method or function is Mathematica’s tool and is a general numerical differential equation solver. We also compared the FD, DTRW, and NDsolve methods. Our results are presented in two sets of plots for each method and infection because the stomach, gut, and liver compartments had the largest concentrations compared to all other compartments, which suppressed the result plots for other compartments.

Although the FD and NDsolve methods were different, we obtained the same results (plots) for both rafimpin and ARV. The liver compartment was observed to have lower compartment concentration compared to the stomach and gut compartment. Additionally, the low liver compartment concentration may also have been due to fact that the drug concentration is eliminated from the liver compartments through three ways, illustrated in Fig. 1.

FIG 1.

Antiretroviral and anti-tuberculosis treatment physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) structure.

The DTRW method was observed to have higher compartment concentration compared to the FD and NDsolve method as illustrated in Fig. 2 and 3. The high heart compartment concentration might have indicated that the compartment was not affected. Additionally, the muscle compartment is one of the organs spared of TB, but the concentration of the muscle compartment was very low compared to the heart compartment. The gut lumen compartment was also observed to have high concentration, which may suggest that it was also not affected by the infection or rifampin.

FIG 2.

Rifampin in humans, capturing large concentration compartments.

FIG 3.

Rifampin in humans.

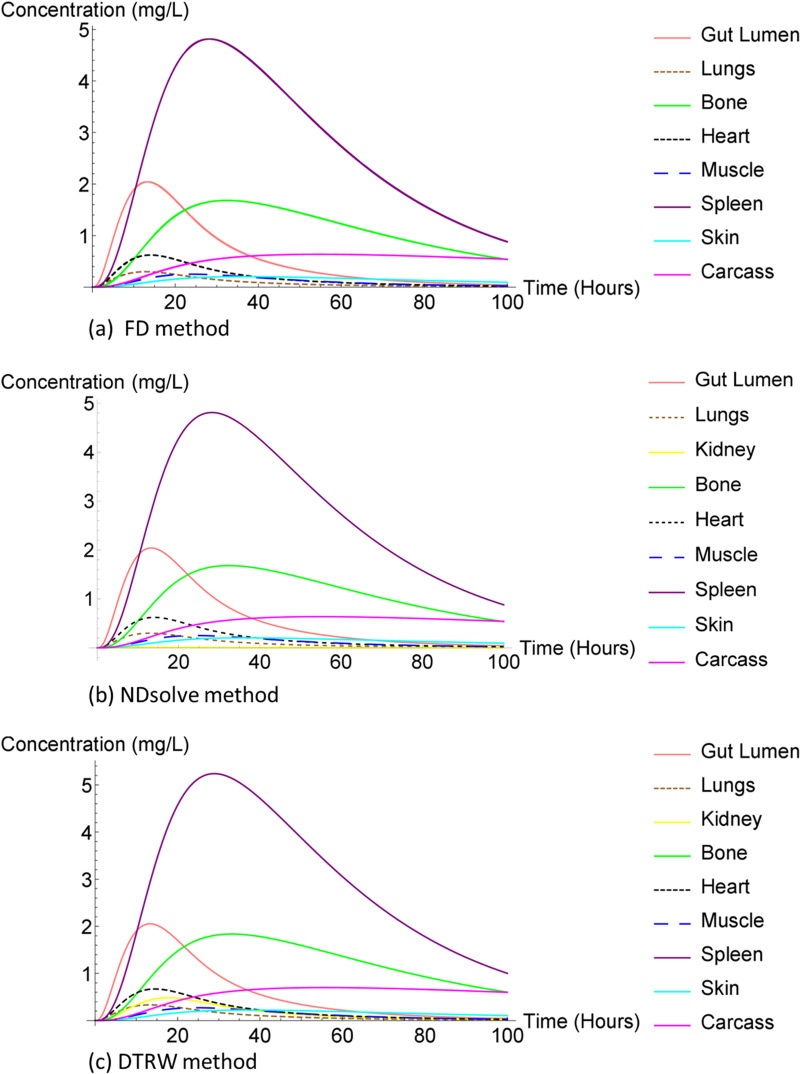

The largest concentration in both humans and mice infected with TB was observed to be similar as presented in Fig. 4.

FIG 4.

Rifampin in mice, capturing large concentration compartments.

The concentration of rifampin both in humans and mice was observed to be closely related and small for the lung compartment and the brain, as shown in Fig. 5.

FIG 5.

Rifampin in mice.

The kidney concentration in the DTRW method was approximately 1.3 mg/L while the kidney concentration for the FD method and NDsolve method was 0.018 mg/L, which was too low to be observed in Fig. 5; we therefore had to provide an additional plot to clearly observe its behavior and how small it was compared to the other compartment concentrations, illustrated in Fig. 6. The rifampin drug is associated with kidney injuries; however, nephrotoxicity normally occurs if the TB-infected individual discontinue their treatment and drug is reintroduced to the body system again at a later stage (10). Nephrotoxicity is due to immune complexes in humans, according to Martin and Sabina (10), although it is not established but a possible mechanism can be observed in mice.

FIG 6.

Rifampin in mice, capturing low concentration compartments.

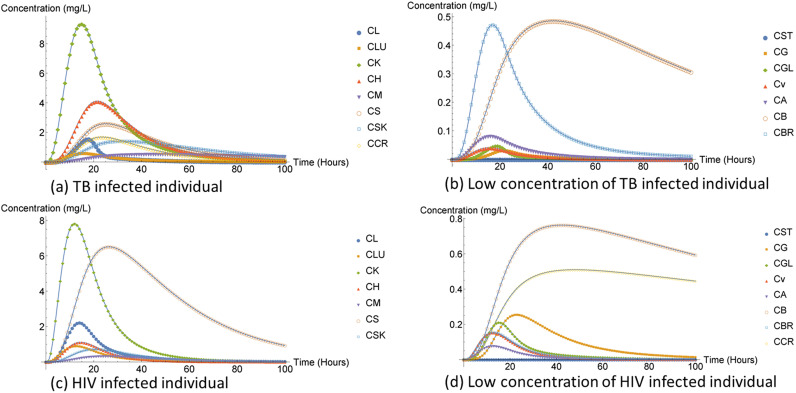

The liver compartment concentration was observed to be small compared to that of FD method and NDsolve method. The ARV drug treatment comes with some unfavorable side effects, especially hepatic damage or hepatotoxicity, which may be life threatening (11, 12). The liver is the main organ needed for normal homeostasis as well as for metabolism of all other drugs present in the body (13). In addition, earlier studies have indicated that about 14–20% individuals infected by HIV and receiving ART had liver transaminase elevation (12) as shown in Fig. 7.

FIG 7.

Efavirenz in humans, capturing large concentration compartments.

In Fig. 8, the spleen compartment concentration was the same for all three methods and the largest. The spleen is the largest secondary immune organ in the body, which has many functions including the initialization of immune reaction to blood-borne antigens and the filtering of the blood of any foreign material and damaged or old red blood cells (14). Furthermore, it took the spleen compartment a bit longer than the other compartment concentration to reach equilibrium for all methods.

FIG 8.

Efavirenz in humans.

The arterial blood was the lowest compartment concentration. The brain compartment concentration was too small to be observed clearly in Fig. 8. The brain and venous blood compartment were observed to be too closely relate as indicated in Fig. 9. The central nervous system (CNS) is penetrated by the HIV virus within days of infection (15). In spite of the progress made over the years to achieve highly active ART, HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HANDs) remain a major challenge in HIV treatment (16, 17). As patients age with HIV, HANDs have been observed to cause notable morbidity and mortality and accelerate the ageing process (16, 17). Furthermore, HIV reproduces in microglia, the brain’s immune cells, causing CNS inflammation and progressive cognitive and behavioral changes (17). Moreover, ART with high molecular mass or weight tends to be poor in terms of penetrating the CNS (15). Studies have reported that 40% of HIV-infected individuals already receiving ARV treatment manifest mild to moderate neurocognitive disorders (16).

FIG 9.

Efavirenz in humans, capturing low concentration compartments.

Figure 10 presents the same data for humans as Fig. 7 does for mice.

FIG 10.

Efavirenz in mice, capturing large concentration compartments.

Figure 10 presents the same data as Fig. 11 except for the kidney compartment concentration, which was too low for the SFD and NDsolve method.

FIG 11.

Efavirenz in mice.

Just like in mice infected with TB (Fig. 5), the kidney compartment concentration in mice infected with HIV was low in Fig. 12. ARV treatment effects in humans and kidney disease slowly advances over time, worsening the kidney. This might be expected for mice, since humans and mice share a similar DNA. The parameter values may have played a role in the two populations having different concentration rates.

FIG 12.

Efavirenz in mice, capturing low concentration compartments.

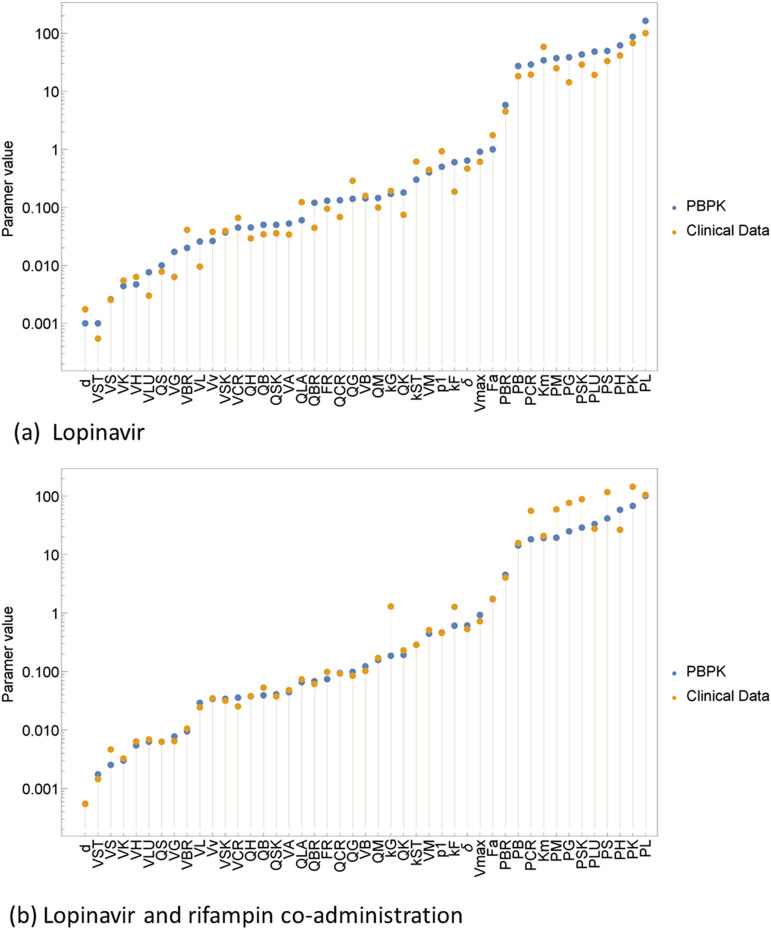

Sensitivity analysis.

The sensitivity analysis revealed commonality in sensitive parameters between the anti-TB and ARV as expected due to the similarities in the underlying models. We performed sensitivity analysis using NDsolve, which is a Mathematica tool. The objective for performing sensitivity analysis was to observe how uncertain the parameters of our models were, since most of the parameters were either obtained from the literature or assumed. Our parameter values are given in Tables 1 and 2; to observe parameter sensitivity we perturbed the parameters up and down. We chose 4P to be equal to 10% of the original parameter value. Some sensitivity graphs have been omitted as they failed to display any meaningful insight.

To recap on what some of the parameters represented, fractional renal clearance, FR, captures the volume ratio of blood cleared of the unchanged drug or substance by the kidney and excreted into the urine. Total blood clearance, δ, represents the volume of blood cleared of drug per unit time (liters/h). The gut lumen transit rate, kF, captures the maximum amount of drug that can be absorbed orally if the gut was saturated with the drug (18). The maximum rate of metabolism, Vmax, is associated with the maximal rate at which oxygen can be transported from the environment to the tissue mitochondria (19). Furthermore, the fractional drug absorption, Fa, captures the small amount of drug movement from the stomach compartment into the bloodstream. While the drug absorption rate, kST, measures the rate of the drug movement and gut drug reabsorption rate, kG, measures the drug movement from the gut lumen compartment to the gut compartment. Brain blood flow, QBR, captures the blood supply to the brain organ, which is very important for the maintenance of the brain function and a prolonged insufficiency causes degeneration and irreversible impairment of the brain. Additionally, all compartment blood flow captures the blood flow to that specific organ. The bone volume, VB, represents the drug dose received by the bone organ. Furthermore, compartment volume represents the drug volume received by an organ. The fractional renal clearance, FR at 10% is obtained as 4P = 0.1 × FR = 0.1 × 0.13 = 0.013. All parameters followed this calculation to obtain the 10% of its parameter. All the ARV treatment parameters not obtained from the literature were assumed to be equal to the rifampin parameters.

As noted in Results, we observed that the rifampin concentration was high for the heart compartment while the efavirenz was high for the spleen compartment and we learned that the heart compartment is rarely affected by TB and the spleen compartment serves a sanctuary to HIV target cells. Therefore, the difference in concentration levels between the two compartments was expected. Furthermore, these different drugs affect same compartment differently. Figure 13 suggests that there is no compartment observed to be sensitive to the fractional renal clearance, FR.

FIG 13.

Sensitivity of different parameters values of fractional renal clearance, . CL, liver concentration; CLU, lung concentration; CB, bone concentration; CK, kidney concentration; CBR, brain concentration; CH, heart concentration; CM, muscle concentration; CSK, skin concentration; CCR, carcass concentration.

The bone compartment was observed to be not closely related to the other compartments, which may be an indication of some sensitivity to the total blood clearance, δ, parameter shown in Fig. 14. Furthermore, for HIV-infected individuals the carcass compartment was observed to have been more related to the bone compartment.

FIG 14.

Sensitivity of total blood clearance, .

Clinical data.

The clinical data used in this study were obtained from the division of clinical pharmacology, University of Cape Town medical school. The clinical study was conducted by the following clinical pharmacologists in 2009: Eric H. Decloedt from the Division of Clinical Pharmacology, Department of Medicine at the University of Stellenbosch; Hellen Mcilleron, Peter Smith, and Gary Maartens from the Division of Clinical Pharmacology, Department of Medicine at the Groote Schuur Hospital under the University of Cape Town, Concepta Merry from the Department of Pharmacology at St. James’s in the Trinity College Dublin, Ireland; and Catherine Orrell of the Faculty of Health Sciences in the University of Cape Town.

Twenty one HIV-infected patients were recruited for the ART second-line study, the patients were older than 18 years and medically stable with a viral load of <400 copies/mL. Four sequential treatment dose was administered over a 12-h dosing interval for 22 days. On day 1 of the study, a standard dose of lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r) (400 mg/100 mg) was orally administered every 12 h without the coadministration of rifampin; on day 8 the standard dose was coadministered with 600 mg of rifampin every 12 h. On day 15, 1.5 times of LPV/r standard dose (600 mg/150 mg) was coadministered with 600 mg rifampin, and finally, twice the standard dose of LPV/r (800 mg/200 mg) was coadministered with 600 mg of rifampin on the 22nd day of the study (20). From the four-regimen dose, we will only focus on a two-regimen dose: the standard dose of LPV/r (400 mg/100 mg) and the standard dose coadministered with 600 mg of rifampin. This is because we only have PBPK parameters for the single dose and we are interested in coadministration. We looked at both the PBPK model and clinical data. We fitted the clinical data to our existing PBPK model. The objective was to verify the PBPK model with clinical data and observe any possibility of DDI.

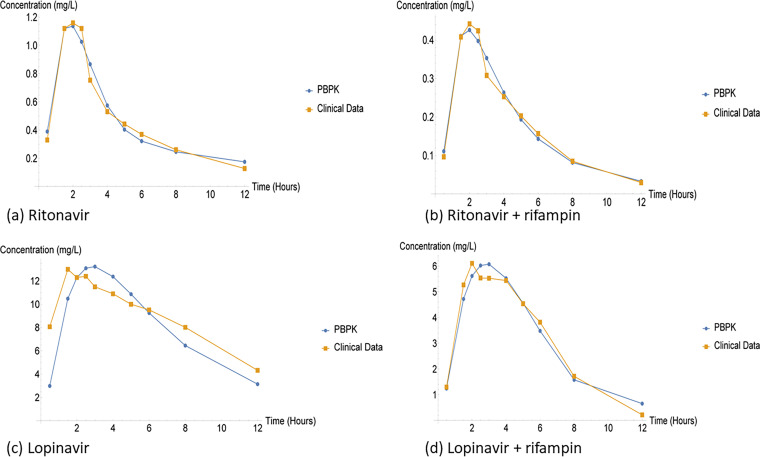

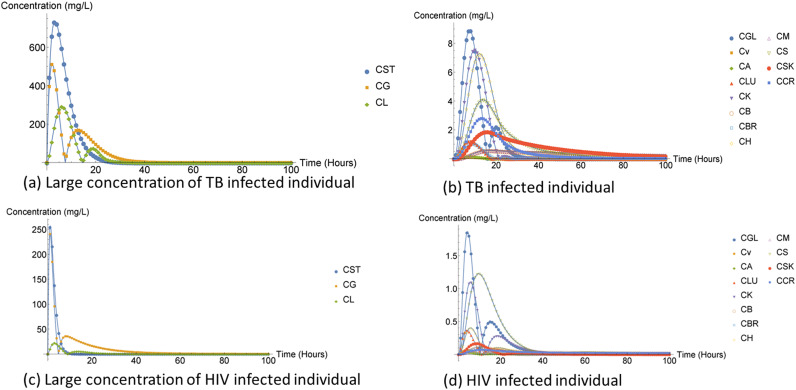

As shown in Fig. 15 and 16, the clinical data are directly related, and thus there is no significant difference in how the clinical data were handled.

FIG 15.

Mean ± SD concentration-time profile standard dose regimen and coadministration dose regimen.

FIG 16.

Standard dose regimen and coadministration dose regimen.

By employing the conjugate gradient (CG) method, we were able to optimize the model parameters to fit the clinical data. The CG method is the most well-known iterative methods for solving sparse systems of linear equation (21). The benefits of CG method are that it is simple to implement, and it accelerates the convergence rate of the steepest descent method while avoiding the Newton’s method high computational power. Additionally, other advantages of the CG method are that we can find an optimal solution at every direction step. By optimal solution we mean that the CG method chooses the value of that minimizes , where is the error term, is the -dimensional subspace span , and is the energy norm (A-norm). The A-norm is considered the natural way to measure the CG method error. The CG method follows the algorithm 2.

(i) Comparison of PBPK model and clinical data. We firstly fitted the two approaches without the use of the CG method and saw that the optimal solution for RTV was 2.28306 while the LPV optimal solution was 32.5858. However, when the CG method was applied on the standard dose and the optimal solution decreased for both treatments, RTV became 0.18349 and LPV became 6.51625. Additionally, we considered the coadministration of standard dose and 600 mg of rifampin, the optimal solution further decreased the optimal of RTV and rifampin was 0.060054 while the optimal LPV and rifampin became 1.185706. The HIV protease inhibitors (PIs) are the key component for receiving highly active reverse transcriptase inhibitors for the HIV treatment, but managing the TB and HIV infected becomes a challenging since anti-TB treatments such as rifampin lead to a substantial reduction in PI concentration through the induction of cytochrome enzyme (20, 22, 23). Furthermore, PI are substrate of both CY3A4 and p-glycoprotein (20).

The single dose of RTV treatment was observed to have been closely related to both approaches while the single dose of LPV indicated a significant difference between the approaches. However, when rifampin was coadministered the correlation between the approaches improved even for LPV treatment. Additionally, the rifampin coadministration dramatically reduced both RTV and LPV concentration. Clinically DDIs are the results of changes in the absorption, distribution, metabolism and elimination (ADME), which modify the effects of the drug (4, 22). The downside of DDI is that it affects the safety of the patients.

Compartments parameters such as , and indicated a significant difference between the bottom-up approach and clinical data. The tissue over partition coefficient showed negative correlation with RTV and higher for the bottom-up approach compared to the clinical data as illustrated by Table A1. This significant difference between the PBPK model and clinical data partition coefficient may have been due to the fact that in this study, we only focused on the blood partitioning of the whole blood concentration and not the plasma concentration. The higher partition coefficient leads to better lipophilicity and tissue penetration of the drug; thus, lower partition coefficient will not easily penetrate the tissue membrane (15). It is common for ART to be used as a cancer treatment, and RTV is used as a lung cancer treatment and it reduces the survivin to boost the apoptosis in the lung cancer (24). Apoptosis is the process that allows cells to die out in a programmed manner and survivin is the inhibitor of apoptosis. Therefore, the low lung volume, VLU, represented by clinical data may be low because the attacked the lung organ in search for a cancerous tumor. Furthermore, the RTV drug is primarily metabolized in the liver and become a pharmacokinetic enhancer for patients with renal impairment; this depends on the specific protease inhibitor coadministered with RTV (25). Nevertheless, since the renal clearance for RTV is negligible for patients with renal impairment it is not expected for the total blood clearance, δ, to decrease and thus the increase in the fractional renal clearance, FR, might have indicated that patients were not affected by renal impairment. All the other parameters for both approaches were observed to be relatively close to each other. Additionally, the p1 parameter represents the probability of the drug going to the gut lumen compartment from the liver compartment. The probability, p1, was used in all methods applied in this study.

Furthermore, coadministration of rifampin with RTV was observed to decrease most of the parameter values. Contrary to the single dose of RTV the lung volume, VLU, and total blood clearance, δ, increased while the fraction, FR, decreased. However, the brain volume, VBR, dramatically decreased compared to all the other parameters illustrated by Table A2. Some of the ARV therapy has limited penetration while others are linked with neurotoxity (15). Drug treatment with molecular mass or weight >500 g/mol and protein binding >90% prevent membrane penetration of the drug; however, drug treatment with molecular mass >500 g/mol and low protein binding allows for better CNS penetration (15). Ritonavir (RTV) has the molecular mass of 720.946 g/mol and protein binding of 98–99% while rifampin has the molecular mass of 822.94 g/mol and protein of 80%.

Clinical data parameter estimation shown in Fig. 17 and 18 can also be obtained in the table form in the Appendix. The majority of the parameters capturing clinical data were lower than the PBPK model. However, all of the tissue over partition coefficients were large for the bottom-up approach shown by Table A3. The optimal partition coefficient for a good membrane penetration is about 100 (26). Moreover, drugs with a very large partition coefficient (>1,000) have a lower diffusibility and therefore they cannot easily diffuse the lipid bilayer (27). Lastly, all other parameters for both clinical data and PBPK model were closely related to each other.

FIG 17.

Ritonavir single dose and coadministration dose of ritonavir and rifampin.

FIG 18.

Standard dose regimen and coadministration dose regimen.

Our results agreed with the study conducted by Decloedt et al. (20). Nevertheless, we limited our study to the standard dose of LPV/r and rifampin coadministered with the standard dose. According (20), HIV-infected patients were more tolerant to the rifampin and rifampin coadministration compared to healthy patients who had high cases of hepatotoxicity. Furthermore, doubling the standard dose of LPV/r overcame the DDI for healthy patients. Additionally, HIV-infected patients developed adverse effects when 1.5 times the standard dose was administered. Out of 21 participants 19 completed the study while 2 developed serious adverse effect, which meant they had to be withdrawn from the study.

DISCUSSION

We investigated the pharmacokinetics of efavirenz and rifampin treatment using a PBPK model. The mathematical model proposed in this study was based on PBPK models obtained from references 8, 28, 29. We derived the FD and DTRW methods. Additionally, we used the NDsolve method as our third numerical scheme, which is very useful for solving problems without analytical solution. The theoretical results were improved by running the numerical simulation. Our model was designed in such a way that the drug is introduced into the stomach. The drug concentration enters a single compartment at a time, and then it has to leave the compartment to enter the next compartment, nevertheless, compartment is not left completely empty. However, if the drug concentration is passed into the arterial blood, the concentration is transported into the whole body excluding the gut and gut lumen compartment. This then says that the arterial blood compartment concentration is divided into small portions transported to the whole body. Therefore, the arterial blood compartment concentration is equal to the sum of all the arterial blood portions. Lastly, there are only three compartments that eliminate the drug concentration from the system, and those compartments are the gut lumen, kidney, and liver compartments.

According to the results obtained from this study compartments such as liver, brain, kidney, heart, spleen, and lungs many have been compartments of interest for either efavirenz or rifampin or even both. The rifampin treatment model results indicated that heart compartment concentration was high for both individuals and mice who were prophylaxis for TB. The heart organ is rarely involved in the TB disease, but when it is, it usually manifests as pericarditis TB (27), which can impair the heart and cause death (30). Therefore, our results might have suggested that the heart compartment had higher rifampin concentration because the compartment was not affected by the virus and therefore the heart organ does not have a lot of work to do to eliminate the virus infection. According to reference 31, TB spares the heart and muscle compartment and somehow, the muscle compartment concentration was low. Nevertheless, the lung compartment concentration was observed to be low compared to all the other compartment concentrations, and we know that the pulmonary TB virus infection primarily affects the lungs. However, the brain compartment concentration was observed to have been very closely related to the lung compartment concentration. TB in the brain is considered to be rare; however, it is difficult to diagnose brain TB, which results in a low diagnosis rate.

The spleen compartment concentration was high for individuals and mice receiving the efivarenz compared to that of individuals and mice receiving rifampin treatment. Furthermore, the spleen compartment hosts one-quarter of the body’s lymphatic system as well as large and diverse population of macrophages, which are potential targets of HIV (32). The role of the spleen at the intersection of the circulatory system and immune system and the abundant presence of HIV-susceptible cells make the spleen compartment a prime candidate for an HIV tissue sanctuary and a therapeutic target in HIV cure research (32, 33). Moreover, the kidney compartment concentration in mice receiving rifampin was low compared to that of individuals receiving efivarenz. Lastly, liver compartment concentration in both ARV and rifampin treatment model was low compared to other higher concentration compartments (stomach and gut). Most HIV-infected patients frequently experience liver damage while one of the major side effects of anti-TB is hepatotoxicity. The hepatotoxicity of the treatment may be the reason why concentration was low or it may be due to the fact that the liver compartment had three ways the drug concentration can leave the compartment, via metabolism, concentration transferred to the venous compartment, and concentration transferred to the gut lumen compartment. Therefore, if an individual is coinfected with TB and HIV, the individual can experience even greater hepatotoxicity since both ARV and anti-TB treatment are toxic to the liver. Finally, kidneys of mice, both infected with HIV and TB were observed to have been affected by the medication more than humans. It might have been due to parameter variation between the two populations or maybe that kidneys of mice were more sensitive to the drug.

When CK = 0, which states that the kidney compartment is empty, but there is a small amount of concentration coming from the arterial blood compartment and leaving the kidney compartment, illustrated by equation 9 in our system. If we choose either δ of FR or to be larger, then the kidney compartment becomes negative; to overcome becoming negative, we had to choose small fractional renal clearance, FR, value. We related the efavirenz model fractional renal clearance, FR, parameter to that one from the rifampin literature, which was small. This observation led us to perform sensitivity analysis for all our parameters to check the uncertainty of the parameters in our PBPK model since most of the parameters were obtained from the literature and the ARV model parameters were adopted from the study of Jones et al. (8) that looked at 19 F. Hoffmann-La Roche compounds orally administered. The stomach compartment was observed to be sensitive to most of the parameters, namely: VB, QB, VCR, QCR, QLA, Vv, VLU, and VS. From Table 2, we observed a variation in the parameters between TB- and HIV-infected individuals, we believe that the parameter sensitivity of all those parameters mentioned above excluding Vv, VLU, and VS may have been due to variation in parameter values and since it was mostly the HIV parameters that were sensitive. However, the drug was introduced into the stomach and no other compartment transferred the drug concentration into the stomach compartment. In fact, the stomach is the primary drug distributor to the body system. Additionally, the gut compartment was observed to be sensitive to some of the parameters that the stomach compartment was sensitive to; this may have been because the gut compartment receives the drug concentration from the stomach compartment. Nevertheless, the gut lumen compartment is an additional transporter of the drug concentration to the gut compartment. The stomach compartment has a direct relationship with three parameters, VST, kST, and VST, and the sensitivity analysis indicated that the stomach compartment was not affected or sensitive toward those three parameters. Therefore, the sensitivity observation for the stomach compartments may be discarded since the stomach compartment has a direct relationship with the gut compartment and it was not affected by the kG parameter changes. However, the liver compartment was observed to have been sensitive to Vv for both TB- and HIV-infected individuals. Nevertheless, the liver compartment also showed some level sensitivity to QB parameter. Therefore, the liver compartment was sensitive to QB and Vv.

As mentioned before in this study we compared three methods, the FD, DTRW, and NDsolve methods. The FD method was observed to be exactly as the NDsolve method in terms of results obtained. However, some compartment concentrations were different between the DTRW and FD methods. For example, for individual infected by TB, the gut lumen and heart compartment concentrations were observed to be equal in the FD and NDsolve methods. However, the DTRW method indicated that the gut lumen concentration was higher than the heart compartment concentration. Furthermore, the DTRW method suggested that the compartment concentration was approximately 1.3 mg/L for mice infected with TB while the FD method suggested that the kidney compartment concentration was very small (0.018 mg/L). The DTRW method is based on the discrete time stochastic process, while the FD follows the deterministic modeling process, which might have been the reason why the methods produced different results for some compartments. Additionally, the differences in the concentration between the two methods might be an indication that the DTRW method may have not eliminated any of the concentration of the body system as rapidly as did the FD method. Therefore, if there was no concentration leaving the system, then there is still high concentration of the drug available in each compartment. Nevertheless, the FD method indicated that kidney compartment concentration for HIV-infected individuals was high (4 mg/L) compared to that of the DTRW method, which was approximately 2.8 mg/L. However, the opposite was observed in mice infected with HIV. The brain compartment concentration for both humans and mice was very small for the FD method. Nevertheless, the overall performance of the FD and DTRW methods was not too different.

We fitted clinical data to the PBPK model, and clinical data used in this study were obtained from the University of Cape Town under the Division of Pharmacology. We applied the CG method to the fitted model. The tissue partition coefficient plays an important role in tissue membrane penetration. There was no partition coefficient greater than 1,000. Most of the partition coefficients were below 100, which may mean that the tissues were not penetrated by the drug. Furthermore, according to the sensitivity analysis no parameters were sensitive to the changes in the partition coefficient. Beside the partition coefficients, kF and Km, most of the parameters were not significantly different from each for the both approaches. The PBPK model and clinic data single dose of RTV were not identical, but the two approaches fitted well. When RTV was coadministered with rifampin the fit between the approaches improved, but the coadministration was observed not to have had too much of a contribution since if the previous vector approximation was used to obtain the next optimal solution, it is bound to improve how the CG method works. There was a huge difference between the PBPK model and clinic data for lopinavir single dose. The HIV and TB viruses can cause physiological and immunologic changes that impact the drug absorption, metabolism, the magnitude of DDI, and even the protein binding (22). The was a high improvement in the fit of the approaches when LPV and rimfampin were coadministered, which indicated that there was some degree of DDI interaction between LPV and 600 mg rifampin. Furthermore, partition coefficients increased except for the brain partition coefficient, PBR, and the spleen partition coefficient, PS. Both the total blood clearance, δ, and fractional renal clearance, FR, decreased for the coadministration of LPV and rifampin by less than 3%, while for the coadministration of RTV and rifampin it was only the fractional renal clearance, FR, that decreased. It was essential to assess the DDI and hence understand the effect it may have on patients’ safety. From reference 20, doubling the standard dose of LPV/r overcame the DDI for healthy patients. However, we did not consider the doubled standard dose since our PBPK model was for single regimen dose and might not perform very well. Lastly, the magnitude of DDI may depend on the dosing regimen.

Conclusion.

In conclusion, the PBPK model suggested that some compartments or organs such lung, brain, liver, and kidney were affected the most by the drug treatments (efavirenz and rifampicin) used in this model or the seropositivity of the virus on the organs have required more drug concentration for the affected organs to neutralize from the infection, and therefore, less concentration was observed from such affected compartment. However, compartments such as the heart and spleen were observed to have high concentrations. The heart compartment is rarely affected by TB. However, the heart organ becomes affected by myocarditis TB, which mimics the cardiovascular TB and pericarditis TB. On the contrary, the spleen compartment harbors HIV tissues. Both drugs have some adverse risk, such as hepatotoxicity and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders, which may be the reason why low concentration was observed for the brain compartment in the HIV model. The PBPK model and clinic data correlated well for both coadministrations. DDI was captured for LPV, which was to be expected since LPV is the HIV PIs, while rifampin tends to reduce the PI through the induction of cytochrome P450 enzyme and the LPV was the victim of DDI more than RTV because it is poorly bioavailable. Overall, the PBPK model is a powerful tool for the prediction of DDI and ARV and anti-TB pharmacokinetics. Finally, we can conclude that there was some correlation between the three methods used in the study. Nonetheless, as mentioned in the earlier sections, the study excluded non-Markovian survival under the DTRW method. The compartmental model in this study can be expressed in terms of the fractional-order differential equation system, which will capture for both the non-Markovian and Markovian survival. Additionally, fractional calculus methods such as the Grunwald-Letnikov derivative are more able to solve the fractional dynamics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We adopted the standard PBPK model from the literature (8, 28). The proposed model builds on the aforementioned models by introducing several modifications. First, we considered the gut and gut lumen compartments to be two separate compartments illustrated in Fig. 1. There is elimination from the gut lumen as feces; if they were one compartment, then the dose from the stomach would immediately start clearing as feces. The gut lumen reabsorbs the drug, which is passed to the gut compartment; hence, the gut lumen compartment influences the amount of the drug concentration in the gut compartment. The gut compartment is also anatomically linked to the liver; this is known as a gut-liver axis. Second, we observed the noneliminating tissues as individual tissues instead of a group. Noneliminating tissues such as the spleen was observed to contribute to the liver compartment and small portions of the arterial blood concentration present in all noneliminating tissues summed up to the concentration leaving the arterial blood compartment. Moreover, the metabolism followed the Michaelis-Menten kinetics. Single substrate biochemical reactions follow the Michaelis-Menten kinetics. Additionally, compartment concentrations in our system of equations 1–15 were directly relatable to Fig. 1.

Absorption of the orally administered drug begins in the stomach. The drug then passes through to the gut, where it is absorbed further. It then passes through to the liver, where (i) some fraction of the drug is passed to the venous blood, which is distributed to the lung compartment with concentration fraction from all the other tissues; (ii) drug concentration is passed through to the gut lumen commonly known as enterohepatic circulation where the drug gets reabsorbed into the gut and eliminated through the gut lumen via feces; and (iii) drug concentration is eliminated from the liver via metabolism. Furthermore, the drug concentration in the spleen compartment is passed through the liver. Drug clearance through the kidneys and liver is described in terms of total blood clearance and fractional renal clearance (fraction assigned to the kidneys) with the remaining fraction assigned to the liver. The drug concentration is also eliminated by the kidneys in urine. Finally, drug concentration gets penetrated into all the other remaining tissues and the rest of the body (carcass).

The model flow diagram and the assumptions result in a system of nonlinear first order ordinary differential (ODE) equations given by equations 1–15. Table 3 provides a description of the parameters and dimension.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

TABLE 3.

Description of state parameters and dimension

| Parameter | Description | Dimension |

|---|---|---|

| Bone concentration | mg/liters | |

| Bone volume | liters | |

| Bone blood flow | liters/h | |

| Bone partition coefficient | 1 | |

| Brain concentration | mg/liters | |

| Brain volume | liters | |

| Brain blood flow | liters/h | |

| Brain partition coefficient | 1 | |

| Heart volume | liters | |

| Heart concentration | mg/liters | |

| Heart blood flow | liters/h | |

| Heart partition coefficient | 1 | |

| Muscle volume | liters | |

| Muscle concentration | mg/liters | |

| Muscle blood flow | liters/h | |

| Muscle partition coefficient | 1 | |

| Skin volume | liters | |

| Skin concentration | mg/liters | |

| Skin blood flow | liters/h | |

| Skin partition coefficient | 1 | |

| Carcass volume | liters | |

| Carcass concentration | mg/liters | |

| Carcass blood flow | liters/h | |

| Carcass partition coefficient | 1 | |

| Arterial concentration | mg/liters | |

| Tissue partition coefficient | 1 | |

| Liver volume | liters | |

| Liver concentration | mg/liters | |

| Hepatic artery blood flow | liters/h | |

| Total liver blood flow | liters/h | |

| Liver partition coefficient | 1 | |

| Gut blood flow | liters/h | |

| Gut volume | liters | |

| Gut concentration | mg/liters | |

| Gut partition coefficient | 1 | |

| Gut lumen concentration | mg/liters | |

| Spleen blood flow | liters | |

| Spleen partition coefficient | 1 | |

| Kidney volume | liters | |

| Kidney concentration | mg/liters | |

| Kidney blood flow | liters/h | |

| Kidney partition coefficient | 1 | |

| Lung volume | liters | |

| Lung concentration | mg/liters | |

| Cardiac output | liters/h | |

| Venous concentration | mg/liters | |

| Lung partition coefficient | 1 | |

| Arterial volume | liters | |

| Venous volume | liters | |

| Stomach volume | liters | |

| Stomach concentration | liters/h | |

| Total blood clearance | liters/h | |

| Fractional renal clearance | 1 | |

| Fractional drug absorption | 1 | |

| Dose | ||

| Time dependence of dose schedule | ||

| Gut drug reabsorption rate | ||

| Drug absorption rate | ||

| Gut lumen transit rate | ||

| Maximum rate of metabolism | ||

| Michaelis-Menten constant | mg/liters |

Initial conditions were

We considered both humans and mice in this; humans and mice have similar DNA. There are more TB PBPK modeling data for mice currently than there are for humans. In addition, we only considered orally administered anti-TB and ARV treatment in both humans and mice. Since oral treatment is the most convenient, least expensive, and usually the safest administration route, it is associated with some limitations since it is passed through the digestive system. Furthermore, if multiple drugs are administered using the same drug administration route, it may lead to DDI. Finally, we solved the differential equation with the finite difference (FD) method and the discrete time random walk (DTRW) method for comparison. Since there is no exact solution for the resulting system, we numerically simulated the model using FD, DTRW, and the built-in solver NDsolver in Mathematica. This comparison was made to quantify variance in solutions based on the selected methods.

Finite difference method.

We introduce the concept of the FD method from Taylor’s theorem where h is the step size and x is the independent variable (34). According to Taylor’s theorem, we can increase x by h; therefore, we can create a Taylor series expansion:

| (16) |

such that,

| (17) |

If then,

| (18) |

similarly

| (19) |

such that,

| (20) |

If then,

| (21) |

subtracting equation 16 from equation 19 we get,

| (22) |

such that,

| (23) |

If then,

| (24) |

Equations 18, 21, and 24 are commonly known as the forward, backward, and central difference approximations to the first order derivative, respectively (34). The Taylor’s approximation is a local linear approximation to the first order derivative. Moreover, the accuracy of the FD method increases when the step-size is chosen to be smaller; therefore, the stability of FD method depends on the time step-size. The FD method is only conditionally stable. Numerical instabilities occurs if one or more of the following conditions occur: (i) the step-size becomes larger than the threshold value , i.e., ; (ii) the number of fixed points of the FD scheme is larger than the number of fixed points of the corresponding differential equation; and (iii) the order of the discrete FD method is larger than the order of the corresponding differential equation (35, 36). Lastly, the detailed implementation of the FD method is available in the Appendix.

Discrete time random walks.

The majority of compartment models require a sequence of compartments and it is necessary to have the ability to solve multiple compartment system (37) system. Each compartment of the multicompartment model has its own survival function, . The flux adjacency matrix, is defined as the flux of a compartment , to compartment , at time , flux matrix is of the size . The additional dimension of captures flux going in and out of the compartmental model, which does not start nor end in any compartment. Therefore, the total flux out of compartment , is the sum over the row of , and similarly the total flux into compartment , is the sum over the column of (37). Utilizing the flux and waiting time survival function notation suggests the number of particles expected in compartment , may be expressed as

| (25) |

Since our study excludes the non-Markovian survival function, then the survival function, , is assumed to be equal to the Markovian survival function, . Therefore, the Markovian outflow can be written as,

| (26) |

where the Markovian survival process function , in the compartment send mass to the compartment . The expected flux of particle, can be written in the form of flux balance equation

| (27) |

Flux out of compartments can be expressed in terms of the overall survival function, such as

| (28) |

The decomposition of the RHS into a sum in order to identify the individual is not unique and it depend on the removal processes. With an assumption that the Markovian removal process is responsible for the particle leaving compartment given that particle survives all of the Markovian removal process , such that then,

| (29) |

from which the flux matrix can be constructed. The principles of the DTRW method is implemented in the Appendix.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

B.A.J. acknowledges the support of the National Research Foundation, South Africa under grant number: 129119 and 127567. S.M. acknowledges the African Institute for Mathematical Sciences for their support toward this research. We also acknowledge Eric H. Decloedt from the division of clinical pharmacology, department of medicine at the University of Stellenbosch, Hellen Mcilleron, Peter Smith, Gary Maartens from the Division of Clinical Pharmacology, Department of Medicine at the Groote Schuur Hospital under the University of Cape Town, Concepta Merry from the department of pharmacology at St. James’s in the Trinity college Dublin, Ireland and Catherine Orrell of the faculty of health sciences in the University of Cape Town.

APPENDIX

Implementation of the finite difference method.

The FD scheme is represented by equations 30–59.

The discrete derivative for is defined by

| (30) |

where is step size. Using the notation above, we propose the following FD scheme discretize the system of equations 1–15.

(i) Bone compartment.

| (31) |

Equation 31 can be written in the form

| (32) |

and we can reduce equation 32 in terms of and . Let, , which implies,

| (33) |

(ii) Brain compartment.

| (34) |

therefore,

| (35) |

when,

(iii) Heart compartment.

| (36) |

let,

Then,

| (37) |

(iv) Muscle compartment.

| (38) |

let

| (39) |

(v) Spleen compartment.

| (40) |

let, . Then, equation 40 becomes,

| (41) |

(vi) Skin compartment.

Let,

| (42) |

which yields,

| (43) |

(vii) Carcass compartment.

| (44) |

and equation 44 can be expressed as follows,

| (45) |

with,

(viii) Liver compartment.

Equation 8 is discretized using implicit forward-Euler

From equation 8 and, 9, we know that . Therefore, equation 8 can be written as,

| (46) |

let, . Then, solve for , equation 47 becomes a quadratic function

let,

whose roots are given by

| (47) |

(ix) Kidney compartment.

| (48) |

can be written as,

| (49) |

with,

(x) Lung compartment.

| (50) |

let, Therefore,

| (51) |

(xi) Arterial blood compartment.

| (52) |

let

| (53) |

(xii) Venous blood compartment.

| (54) |

hence,

| (55) |

(xiii) Gut compartment.

| (56) |

(xiv) Gut lumen compartment.

| (57) |

| (58) |

(xv) Stomach compartment.

| (59) |

let,

Which implies,

| (60) |

If we set to 1, equation 33 becomes

| (61) |

where and are constants obtained from the literature.

DTRW method implementation.

We will now solve our system equations 1–15, on the basis of a discrete time stochastic process. The discrete time process is completely described by the Markovian survival functions and incoming flux. From equation 25, we can find the flux matrix, , and if we know the flux matrix, , at all times we can calculate the solution of the PBPK model. To make things easy, we first considered the eliminating compartment excluding the kidney compartment and also include the spleen compartment that has a direct relationship with the liver compartment.

| (62) |

where is Kronecker delta function, , is initial condition, and is time scale function. represented as . The survival function is

(i) Gut compartment.

There is no flux entering the gut compartment from outside the system; therefore, will only represent the initial condition

| (63) |

The survival function is

(ii) Liver compartment.

There is no flux entering the gut compartment from outside the system, therefore, will only represent the initial condition

| (64) |

We have three removal processes: to the venous, to the gut lumen compartment, and to the outside system (metabolism)

where

(iii) Gut lumen compartment.

There is no flux entering the gut compartment from outside the system; therefore, will only represent the initial condition

| (65) |

We have two removal processes: to the gut compartment and outside system (elimination by faeces)

(iv) Spleen compartment.

There is no flux entering the spleen compartment from outside the system; therefore, will only incorporate the initial condition

| (66) |

and the survival function is

Second, we considered the noneliminating tissue compartments and the kidney compartment.

(v) Kidney compartment.

There is no flux entering the kidney compartment from outside the system; therefore, will only incorporate the initial condition

| (67) |

We have two removal processes: to the venous blood compartment and to the outside system (elimination by urine)

where

(vi) Bone compartment.

There is no flux entering the bone compartment from outside the system; therefore, will only incorporate the initial condition

| (68) |

and the removal process is

(vii) Brain compartment.

There is no flux entering the brain compartment from outside the system; therefore, will only incorporate the initial condition

| (69) |

and the removal process is

(viii) Muscle compartment.

There is no flux entering the muscle compartment from outside the system; therefore, will only incorporate the initial condition

| (70) |

and the removal process is

(ix) Skin compartment.

There is no flux entering the skin compartment from outside the system, therefore, will only incorporate the initial condition

| (71) |

and the removal process is

(x) Heart compartment.

There is no flux entering the heart compartment from outside the system, therefore, will only incorporate the initial condition

| (72) |

and the removal process is

(xi) Lung compartment.

There is no flux entering the lung’s compartment from outside the system; therefore, will only incorporate the initial condition

| (73) |

and the survival function is

(xii) Carcass compartment.

There is no flux entering the carcass compartment from outside the system; therefore, will only incorporate the initial condition

| (74) |

and the removal process is

Finally, we considered the arterial and venous blood compartment since it links up all the compartments.

(xiii) Arterial blood compartment.

There is no flux entering the arterial blood compartment from outside the system; therefore, will only represent the initial condition

| (75) |

There exists multiple survival functions for concentrations leaving the arterial blood supply

(xiv) Venous blood compartment.

Also, the venous blood compartment has no flux entering from outside the system; therefore, will incorporate the initial condition

| (76) |

and the survival function is

The flux matrix to be computed is

represents the flux entering each compartment from outside system, and represents flux elimination to the outside system. We have multiple elements from the flux matrix that we need to calculate recursively, and we obtain that by using equation 29. Starting with the flux entering the gut compartment from stomach compartment

| (77) |

Fluxes entering the liver compartment: from gut compartment

| (78) |

and entering from the spleen compartment

| (79) |

We can also find fluxes leaving the liver compartment: to the gut lumen compartment

| (80) |

and flux leaving through metabolism

| (81) |

Additionally, using equation 29, we can find the fluxes leaving the gut lumen compartment: entering gut compartment

| (82) |

and leaves the gut lumen via elimination

| (83) |

Similarly, using equation 29, we can find fluxes leaving the arterial blood compartments: flux entering the liver

| (84) |

to the spleen compartment

| (85) |

flux to the liver kidney

| (86) |

flux entering the bone compartment

| (87) |

to the brain compartment

| (88) |

flux entering the muscle compartment

| (89) |

to the skin compartment

| (90) |

flux entering the heart compartment

| (91) |

and the flux to the carcass compartment

| (92) |

The flux leaving the system from the kidney compartment

| (93) |

Flux entering the lung compartment from the venous blood compartment

| (94) |

Flux entering the arterial blood compartment from the lung’s compartment

| (95) |

Finally, using equation 29 we can find fluxes entering the venous blood compartment: from the liver compartment

| (96) |

from the kidney compartment

| (97) |

flux from the bone compartment

| (98) |

flux from the brain compartment

| (99) |

from the muscle compartment

| (100) |

entering from the skin compartment

| (101) |

from the heart compartment

| (102) |

and flux entering from the carcass compartment

| (103) |

Therefore, the approximation can be obtained by considering equation 27

| (104) |

| (105) |

| (106) |

| (107) |

| (108) |

| (109) |

| (110) |

| (111) |

| (112) |

| (113) |

| (114) |

| (115) |

| (116) |

| (117) |

| (118) |

Equation 104–118 can be expressed in terms of compartment concentration as follows,

| (119) |

| (120) |

| (121) |

| (122) |

| (123) |

| (124) |

| (125) |

| (126) |

| (127) |

| (128) |

| (129) |

| (130) |

| (131) |

| (132) |

| (133) |

Sensitivity analysis.

Figure A1 indicates that the liver compartment reached the maximum peak faster than all other components, which might have suggested that the compartment was sensitive to the bone volume, . The results for bone, blood flow, , and were the same even though the volume had higher concentration, the same thing was observed for the carcass volume, , and carcass blood flow, .

FIG A1.

Sensitivity of the bone volume, .

The gut and stomach compartment for only HIV-infected individuals was observed to have been sensitive to the carcass blood flow as illustrated in Fig. A2. The variation in the carcass and bone parameters might be the reason as to why the two compartments behave different compared to all the other compartments. This parameter variation was observed in Table 2, e.g., the TB for humans was 0.149 while HIV for humans was 0.0856.

FIG A2.

Sensitivity of the carcass blood flow, .

The hepatic artery blood, , was observed to have minor sensitivity to the stomach compartment. There was also parameter variation; however, the variation in was observed to have not have affected compartments like the bone volume and carcass blood flow shown Fig. A3.

FIG A3.

Sensitivity of the hepatic artery blood flow, .

The large concentration compartment was observed to be different for the drugs; however, compartments are observed not to be sensitive to the gut lumen transit rate, , parameter presented in Fig. A4.

FIG A4.

Sensitivity of gut lumen transit rate . CL, liver concentration; CGL, gut lumen concentration; CG, gut concentration.

According to Fig. A5 all compartments are very closely related to each other and thus no sensitivity while on the other hand concentration of the bone and carcass compartment was observed to be different from all the other compartments yet again for the HIV-infected individual.

FIG A5.

Sensitivity of maximum rate of metabolism, . CLU, lung concentration; CB, bone concentration; CK, kidney concentration; CBR, brain concentration; CH, heart concentration; CM, muscle concentration; CSK, skin concentration; CCR, carcass concentration; CGL, gut lumen concentration; CG, gut concentration; CST Stomach concentration; CA, arterial concentration; Cv, venous concentration.

Large compartment concentrations in Fig. A6 indicated that the all the other compartments expect for the gut and stomach were not sensitive to . The gut and stomach compartment for both infections was sensitive to the venous blood, , parameter.

FIG A6.

Sensitivity of venous blood volume, .

The gut and stomach compartments were sensitive to the lung volume illustrated in Fig. A7.

FIG A7.

Sensitivity of lung volume, .

No sensitivity, even though both-infected individuals seems different from each other as shown in Fig. A8.

FIG A8.

Sensitivity of fractional drug absorption, .

According to Fig. A9, compartments were correlated to each other and thus compartments were not sensitive to the drug absorption rate, .

FIG A9.

Sensitivity of the drug absorption rate, .

Compartments were not sensitive to brain blood flow, , and results were the same as for but concentration values were different as shown in Fig. A10.

FIG A10.

Sensitivity of the brain blood flow, .

The liver blood flow, , was the same the spleen blood flow, . No sensitive since all the parameters followed the same thread and were closely related to each other illustrated in Fig. A11.

FIG A11.

Sensitivity of the liver volume, .

Figure A12 suggests that the gut compartment arterial blood compartment were sensitive to the spleen volume, .

FIG A12.

Sensitivity of the spleen volume, .

Figure A13 suggests no sensitivity.

FIG A13.

Sensitivity of the stomach volume, .

Algorithms used on the study.

(i) Finite difference algorithm.

The algorithm 1 implicit FD scheme is as follows:

1: procedure FD SCHEME

2:

3: T ← Nt * dt,

4: Initialize CB0,

5: for n in range(0,FT,dt): do

6: Compute for CAn+1 bound values

7: Solve

8: end for

9: end procedure

The for loop generates all integers from 0 to the number of time intervals, , at the time step, . The same algorithm maybe followed for all the other equations.

Conjugate gradient algorithm.

The algorithm 2 conjugate gradient was as follows:

1: procedure Clinical data fit

2: init ← parameters obtained from the literature,

3: Δ ← 0.9

4: objFn(pvec) := ‖NDsolveSolution(pvec,tvec) − data‖=

5: min ← objFn(init),

6: dir ← 1,

7: while min > tol do

8: for i n s: do

9: cand ← init + Δ × ei × init

10: min1 ← objFn(cand)

11: cand ← init − Δ × ei × init

12: min2 ← objFn(cand)

13: if min1 ≤ min2 : then

14: sign ← 1

15: else

16: sign ← 1

17: end if

18: locmin ← min(min1,min2)

19: if locmin < min: then

20: dir ← i,

21: min ← locmin,

22: init ← init + sign × Δ × ei × init

23: else

24: init ← init + sign × Δ × ei × init

25: cand ← init

26: end if

27: end for

28: end while

29: end procedure

The first step of the algorithm defines the objective function that we seek to minimize. This function is the Euclidean norm or norm distance between the solution obtained from the PBPK model and the data at discrete time points prescribed by . In line 3 to line 6 we set the step size, number of iterations per time step, direction of the vector, and the PBPK model parameters. The for loop iterates though all directions in the parameter space and selects the direction that decreases our objective function the most. The same algorithm was followed for the single dose and rifampin coadministration with LPV and RTV. The same algorithm was followed for the single dose and rifampin coadministration with LPV and RTV.

Clinical data parameter estimation.

Tables A1–A4 are from the clinical data results. Table A1 and A2 present data from Fig. 17. Table A3 and A4 are graphically presented in Fig. 17 and 18.

TABLE A1.

Ritonavir dose and PBPK modela

| Parameter | PBPK model | Ritonavir | Ritonavir-PBPK model |

|---|---|---|---|

| 164.21 | 9.84191 | –154.36809 | |

| 48.48 | 0.130193 | –48.349807 | |

| 38.69 | 9.54082 | –29.14918 | |

| 34.29 | 9.10853 | –25.18147 | |

| 29.04 | 12.4314 | –16.6086 | |

| 49.71 | 39.0456 | –10.6644 | |

| 0.64 | 0.134198 | –0.505802 | |

| 0.17 | 0.00330179 | –0.16669821 | |

| 0.145 | 0.0157034 | –0.1292966 | |

| 0.12 | 0.000414622 | –0.119585378 | |

| 0.05 | 0.00328242 | –0.04671758 | |

| 0.01 | 0.0024156 | –0.0075844 | |

| 0.0076 | –0.0075843873 | ||

| 0.0257 | 0.0245489 | –0.0011511 | |

| 0.0526 | 0.0517705 | –0.0008295 | |

| 0.0171 | 0.0163567 | –0.0007433 | |

| 0.0026 | 0.00247474 | –0.00012526 | |

| 0.001 | 0.00101598 | ||

| 0.0263 | 0.0266393 | 0.0003393 | |

| 0.001 | 0.0019 | 0.0009 | |

| 0.0044 | 0.00842567 | 0.00402567 | |

| 0.0047 | 0.009028 | 0.004328 | |

| 0.045 | 0.0541169 | 0.0091169 | |

| 0.18 | 0.19354 | 0.01354 | |

| 0.0448 | 0.0596846 | 0.0148846 | |

| 0.91 | 0.963591 | 0.053591 | |

| 0.1325 | 0.196206 | 0.063706 | |

| 0.0371 | 0.122251 | 0.085151 | |

| 0.14 | 0.255428 | 0.115428 | |

| 0.02 | 0.141482 | 0.121482 | |

| 0.13 | 0.28872 | 0.15872 | |

| 0.06 | 0.22786 | 0.16786 | |

| 0.05 | 0.246738 | 0.196738 | |

| 0.3 | 0.612878 | 0.312878 | |

| 0.1429 | 0.532047 | 0.389147 | |

| 0.4 | 0.837204 | 0.437204 | |

| 0.5 | 0.954406 | 0.454406 | |

| 1 | 1.9147 | 0.9147 | |

| 87.47 | 94.1294 | 6.659400 | |

| 5.81 | 26.9782 | 21.1682 | |

| 43.22 | 74.618 | 31.398 | |

| 37.39 | 119.334 | 81.944 | |

| 62.02 | 169.605 | 107.585 | |

| 27.33 | 315.97 | 288.64 | |

| 0.6 | 529.73 | 529.13 |

PBPK, physiologically based pharmacokinetic.

TABLE A2.

Ritonavir and rifampin coadministrationa

| Parameter | RTV | RTV and rifampin coadministration | RTV-coadministration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 315.97 | 20.7397 | –295.2303 | |

| 94.1294 | 1.32392 | –92.80548 | |

| 119.334 | 32.3748 | –86.9592 | |

| 26.9782 | 9.54206 | –17.43614 | |

| 9.54082 | 7.17779 | –2.36303 | |

| 0.837204 | 0.422453 | –0.414751 | |

| 0.532047 | 0.155193 | –0.376854 | |

| 0.612878 | 0.307796 | –0.305082 | |

| 0.246738 | 0.0560195 | –0.1907185 | |

| 0.28872 | 0.130071 | –0.158649 | |

| 0.141482 | –0.141481737203 | ||

| 0.122251 | 0.0438559 | –0.0783951 | |

| 0.196206 | 0.136807 | –0.059399 | |

| 0.963591 | 0.931784 | –0.031807 | |

| 0.0596846 | 0.0437894 | –0.0158952 | |

| 0.0157034 | 0.00216572 | –0.01353768 | |

| 1.9147 | 1.90672 | –0.00798 | |

| 0.954406 | 0.94645 | –0.007956 | |

| 0.009028 | 0.0044301 | –0.0045979 | |

| 0.00842567 | 0.00437904 | –0.00404663 | |

| 0.00330179 | –0.0032870105 | ||

| 0.0163567 | 0.013998 | –0.0023587 | |

| 0.00247474 | 0.000962493 | –0.001512247 | |

| 0.0266393 | 0.0265313 | –0.000108 | |

| 0.00101598 | 0.00101081 | ||

| 0.0019 | 0.00189986 | ||

| 0.0517705 | 0.0523406 | 0.0005701 | |

| 0.0245489 | 0.0254851 | 0.0009362 | |

| 0.0024156 | 0.00814276 | 0.00572716 | |

| 0.0541169 | 0.0607164 | 0.0065995 | |

| 0.0265783 | 0.0265626873 | ||

| 0.255428 | 0.284188 | 0.02876 | |

| 0.00328242 | 0.0845743 | 0.08129188 | |

| 0.22786 | 0.571334 | 0.343474 | |

| 0.134198 | 1.21102 | 1.076822 | |

| 9.84191 | 12.0278 | 2.18589 | |

| 0.19354 | 5.70293 | 5.50939 | |

| 0.130193 | 20.655 | 20.524807 | |

| 0.000414622 | 25.2302 | 25.229785378 | |

| 9.10853 | 34.4566 | 25.34807 | |

| 74.618 | 102.035 | 27.417 | |

| 39.0456 | 191.189 | 152.1434 | |

| 12.4314 | 357.717 | 345.2856 | |

| 529.73 | 966.165 | 436.435 | |

| 169.605 | 691.59 | 521.985 |

RTV, ritonavir.

TABLE A3.

Lopinavir single dose and PBPK model

| Parameter | PBPK model | Lopinavir | Lopinavir-PBPK model |

|---|---|---|---|

| 164.21 | 100.693 | –63.517 | |

| 48.48 | 19.1626 | –29.3174 | |

| 38.69 | 14.3004 | –24.3896 | |

| 62.02 | 41.4959 | –20.5241 | |

| 87.47 | 67.9382 | –19.5318 | |

| 49.71 | 33.2596 | –16.4504 | |

| 43.22 | 28.9173 | –14.3027 | |

| 37.39 | 25.0166 | –12.3734 | |

| 29.04 | 19.4299 | –9.6101 | |

| 27.33 | 18.2858 | –9.0442 | |

| 5.81 | 4.51264 | –1.29736 | |

| 0.6 | 0.186362 | –0.413638 | |

| 0.91 | 0.608856 | –0.301144 | |

| 0.64 | 0.464827 | –0.175173 | |

| 0.18 | 0.0741906 | –0.1058094 | |

| 0.12 | 0.0444087 | –0.0755913 | |

| 0.1325 | 0.0682521 | –0.0642479 | |

| 0.145 | 0.0989121 | –0.0460879 | |

| 0.13 | 0.0944179 | –0.0355821 | |

| 0.0526 | 0.0339747 | –0.0186253 | |

| 0.0257 | 0.00949909 | –0.01620091 | |

| 0.045 | 0.0291137 | –0.0158863 | |

| 0.05 | 0.0342225 | –0.0157775 | |

| 0.05 | 0.0357756 | –0.0142244 | |

| 0.0171 | 0.0063204 | –0.0107796 | |

| 0.0076 | 0.00300404 | –0.00459596 | |

| 0.01 | 0.00776703 | –0.00223297 | |

| 0.001 | 0.000546271 | –0.000453729 | |

| 0.0026 | 0.00253354 | ||

| 0.001 | 0.00174602 | 0.00074602 | |

| 0.0044 | 0.00546948 | 0.00106948 | |

| 0.0047 | 0.00631854 | 0.00161854 | |

| 0.0371 | 0.0392433 | 0.0021433 | |

| 0.0263 | 0.0378765 | 0.0115765 | |

| 0.1429 | 0.158015 | 0.015115 | |

| 0.02 | 0.0408718 | 0.0208718 | |

| 0.0448 | 0.0658243 | 0.0210243 | |

| 0.17 | 0.192302 | 0.022302 | |

| 0.4 | 0.4438 | 0.0438 | |

| 0.06 | 0.12286 | 0.06286 | |

| 0.14 | 0.286674 | 0.146674 | |

| 0.3 | 0.614301 | 0.314301 | |

| 0.5 | 0.927373 | 0.427373 | |

| 1 | 1.74896 | 0.74896 | |

| 34.29 | 58.3905 | 24.1005 |

TABLE A4.

Lopinavir and rifampin coadministration

| Parameter | PBPK model | Lopinavir and rifampin coadministration | Liponavir-coadministration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 58.3905 | 26.6331 | –31.7574 | |

| 33.2596 | 27.7043 | –5.5553 | |

| 4.51264 | 4.05398 | –0.45866 | |

| 0.927373 | 0.722786 | –0.204587 | |

| 0.614301 | 0.531022 | –0.083279 | |

| 1.74896 | 1.72506 | –0.0239 | |

| 0.12286 | 0.102339 | –0.020521 | |

| 0.0989121 | 0.0849967 | –0.0139154 | |

| 0.0357756 | 0.0253304 | –0.0104452 | |

| 0.0682521 | 0.0613152 | –0.0069369 | |

| 0.464827 | 0.457928 | –0.006899 | |

| 0.0291137 | 0.0244 | –0.0047137 | |

| 0.0408718 | 0.037727 | –0.0031448 | |

| 0.0342225 | 0.0317089 | –0.0025136 | |

| 0.0944179 | 0.0925387 | –0.0018792 | |

| 0.00776703 | 0.0064697 | –0.00129733 | |

| 0.00174602 | 0.00144958 | –0.00029644 | |

| 0.0378765 | 0.0377028 | –0.0001737 | |

| 0.286674 | 0.286674 | 0 | |

| 0.0063204 | 0.0063204 | 0 | |

| 0.000546271 | 0.000549244 | ||

| 0.00300404 | 0.00326094 | 0.0002569 | |

| 0.00631854 | 0.00691217 | 0.00059363 | |

| 0.0339747 | 0.0348362 | 0.0008615 | |

| 0.00546948 | 0.00637605 | 0.00090657 | |

| 0.00949909 | 0.0105928 | 0.00109371 | |

| 0.00253354 | 0.00466299 | 0.00212945 | |

| 0.0444087 | 0.0481469 | 0.0037382 | |

| 0.0658243 | 0.0737609 | 0.0079366 | |

| 0.158015 | 0.170542 | 0.012527 | |

| 0.0392433 | 0.0529689 | 0.0137256 | |

| 0.0741906 | 0.0986976 | 0.024507 | |

| 0.192302 | 0.230863 | 0.038561 | |

| 0.4438 | 0.512205 | 0.068405 | |

| 0.608856 | 1.27569 | 0.666834 | |

| 0.186362 | 1.29529 | 1.108928 | |

| 14.3004 | 15.7342 | 1.4338 | |

| 19.1626 | 20.8014 | 1.6388 | |

| 100.693 | 105.191 | 4.498 | |

| 18.2858 | 55.9625 | 37.6767 | |

| 19.4299 | 59.4643 | 40.0344 | |

| 25.0166 | 76.5619 | 51.5453 | |

| 28.9173 | 88.5003 | 59.583 | |

| 41.4959 | 116.991 | 75.4951 | |

| 67.9382 | 144.539 | 76.6008 |

Footnotes

[This article was published on 19 July 2022 with panels missing from figures. The missing panels were added in the current version, posted on 9 August 2022.]

REFERENCES

- 1.Bélair J, Nekka F, Milton JG. 2021. Introduction to focus issue: dynamical disease: a translational approach. Chaos 31:060401. 10.1063/5.0058345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rasool MF, Khalil F, Läer S. 2015. A physiologically based pharmacokinetic drug–disease model to predict carvedilol exposure in adult and paediatric heart failure patients by incorporating pathophysiological changes in hepatic and renal blood flows. Clin Pharmacokinet 54:943–962. 10.1007/s40262-015-0253-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]