ABSTRACT

The optimal dosing regimen for meropenem in critically ill patients undergoing continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) remains undefined due to small studied sample sizes and uninformative pharmacokinetic (PK)/pharmacodynamic (PD) analyses in reported studies. The present study aimed to perform a population PK/PD meta-analysis of meropenem using available literature data to suggest the optimal treatment regimen. A total of 501 meropenem concentration measurements from 78 adult CRRT patients pooled from nine published studies were used to develop the population PK model for meropenem. PK/PD target (40% and 100% of the time with the unbound drug plasma concentration above the MIC) marker-based efficacy and risk of toxicity (trough concentrations of >45 mg/L) for short-term (30 min), prolonged (3 h), and continuous (24 h) infusion dosing strategies for meropenem were investigated. The impact of CRRT dose and identified covariates on the PD probability of target attainment (PTA) and predicted toxicity was also examined. Meropenem concentration data were adequately described by a two-compartment model with linear elimination. Trauma was identified as a pronounced modifier for endogenous clearance of meropenem. Simulations demonstrated that adequate PK/PD targets and low risk of toxicity could be achieved in non-trauma CRRT patients receiving meropenem regimens of 1 g every 6 h infused over 30 min, 1 g every 8 h infused over 3 h, and 2 to 4 g every 24 h infused over 24 h. The impact of CRRT dose (25 to 50 mL/kg/h) on PTA was clinically irrelevant, and continuous infusion of 3 to 4 g every 24 h was suitable for trauma CRRT patients (MICs of ≤0.5 mg/L). A population PK model was developed for meropenem in CRRT patients, and different dosing regimens were proposed for non-trauma and trauma CRRT patients.

KEYWORDS: continuous renal replacement therapy, meropenem, population pharmacokinetics, critically ill, NONMEM

INTRODUCTION

Sepsis is an overwhelming reaction to infection that comes with high morbidity and mortality rates (39.2 to 63.6%) (1), being the leading cause of patient admissions to intensive care units. Meropenem is one of the commonly used β-lactam antibiotics for empirical treatment of sepsis due to its exceptionally potent antibacterial activity against Gram-positive cocci, Gram-negative bacilli, and anaerobic bacteria (2).

Meropenem is a hydrophilic molecule with low volume of distribution (0.3 L/kg) and protein binding (2%) values, and it is mainly eliminated via the kidneys (3). Meropenem displays time-dependent bactericidal activity, and the percentage of the time with the unbound drug plasma concentration above the MIC (fT>MIC) of the dominating pathogen is correlated with its maximal bactericidal efficacy (4). A fT>MIC value of 40% is a frequently used pharmacokinetic (PK)/pharmacodynamic (PD) index of meropenem for common hospitalized patients. However, the PK/PD index of 100% fT>MIC is advocated for critically ill patients who need aggressive antibiotic treatment to ensure the killing effect (5). Although meropenem shows a good tolerability profile, it may still cause unwanted effects. For instance, neurotoxicity and nephrotoxicity may occur when the plasma trough concentration of meropenem exceeds 64.2 mg/L and 44.5 mg/L, respectively. These thresholds were established based on a retrospective study of routine therapeutic drug monitoring to investigate possible concentration-dependent adverse effects for β-lactam antibiotics (6).

About 50% of critically ill patients with sepsis suffer from acute kidney injury (AKI) (7), which requires the initiation of continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) in approximately 70% of the cases (8). The three commonly used modalities of CRRT include continuous venovenous hemofiltration (CVVH), continuous venovenous hemodialysis (CVVHD), and continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration (CVVHDF). The main determinant of solute removal capacity for different CRRT modalities is CRRT effluent dose.

Drug PK in critically ill patients undergoing CRRT are complicated. On one hand, the volume of distribution and clearance could be significantly altered by the pathological factors. For example, the volume of distribution is usually increased for hydrophilic drugs due to fluid overload and increased capillary permeability in critically ill patients, while the drug clearance could be decreased in cases of AKI, preserved (maintaining normal function), or markedly increased under the condition of augmented renal clearance (ARC). ARC is a common phenomenon in critically ill patients suffering from severe trauma or burn injuries and significantly increases the drug renal clearance (9). On the other hand, the extracorporeal removal of drug induced by CRRT makes the in vivo drug disposition difficult to estimate, and the extent of drug removal by CRRT shows wide variation (10).

Appropriate antibiotic dosing in critically ill patients undergoing CRRT is vital to achieve optimal bactericidal efficacy and improve the clinical outcomes (11, 12). Although many studies have reported the PK/PD characteristics of meropenem in CRRT patients, optimal meropenem dosing recommendations remain a matter of debate. The reported dosing regimens for meropenem in previous studies are quite divergent, and the studied sample size is small (n = 12 to 24) (13–16). Furthermore, the reported PK studies are mainly focused on the traditional compartmental or noncompartmental approach, and the CRRT impact on PK/PD probability of target attainment (PTA) is scarcely investigated. Therefore, available PK/PD analyses are uninformative for guiding meropenem dosing in the CRRT patient population.

The aim of this study was to conduct a population PK meta-analysis utilizing pooled meropenem concentration data for critically ill patients undergoing CRRT and to investigate the optimal combination of meropenem dosing regimen and CRRT dose for pathogen treatment in this patient population.

RESULTS

Patients.

Seventy-eight critically ill patients (including 6 trauma patients) undergoing CRRT were included in this pooled population PK analysis (Table 1). The median age of the 78 patients was 58.5 years, and the median body weight was 75 kg. Of these patients, 45 patients (57.6%) underwent CVVH, 35 patients (44.8%) received CVVHDF, and 4 patients (5.0%) were treated with CVVHD. The median CRRT dose was 25.0 mL/h/kg.

TABLE 1.

Overview of the demographic features, dosing regimens, and CRRT settings for the included studies

| Parametera | Finding(s) in study by: |

Overall finding(s) (n = 78) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thalhammer et al. (28) (n = 9) | Kawano et al. (29) (n = 4) | Giles et al. (30) (n = 10) | Isla et al. (17) (n = 20) | Ververs et al. (31) (n = 5) | Valtonen et al. (32) (n = 6) | Robatel et al. (33) (n = 10) | Langgartner et al. (34) (n = 4) | Bilgrami et al. (35) (n = 10) | ||

| Demographic features | ||||||||||

| Age (median [IQR]) (yr) | 57 (53–61) | 75 (67.5–75) | 67.5 (60.2–69.7) | 64 (36.2–73.5) | 52 (39–53) | 41 (30–60.2) | 61 (57.2–65.2) | 54.5 (48.7–59.7) | 56.5 (48.7–60.5) | 58.5 (48–69) |

| Body wt (median [IQR]) (kg) | 82 (70–90) | 51.5 (48.5–54.7) | 77 (70–88) | 75 (69.7–80) | 85 (80–94) | 77.5 (75–83.7) | 75 (71.2–83.7) | 73 (58.7–88.2) | 70 (66.2–102.5) | 75 (69.2–85) |

| Male/female (no. [%]) | 6 (67)/3 (33) | 2 (50)/2 (50) | 7 (70)/3 (30) | 15 (75)/5 (25) | 1 (20)/4 (80) | 3 (50)/3 (50) | 8 (80)/2 (20) | 3 (75)/1 (25) | 6 (60)/4 (40) | 51 (65)/27 (35) |

| Urine output (median [IQR]) (mL/24 h) | Anuric | Anuric | NR | NR | Anuric | 70 (13.2–187.5) | Anuric | Anuric | 135 (0–247.5) | |

| APACHE II score (median [IQR]) | NR | NR | 27 (23.5–29) | 19 (13.7–25) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 25 (22–28.5) | |

| CLCR (median [IQR]) (L/h) | NR | NR | NR | 1.03 (0.13–4.52) | NR | NR | 0.62 (0.46–0.75) | NR | NR | |

| Dosing regimens | ||||||||||

| Dose | 1 g as single dose | 0.5 or 1 g q8h/q12h | 1 g q12h | 0.5, 1, and 2 g q6h/q8h | 0.5 g q12h | 1 g as single dose | 0.5 or 1 g q8h/q12h | 1 g q12h | 1 g q8h | |

| Infusion time (min) | 15 | 30 | 5 | 20 | 30 | 30 | 25 | 20 | 5 | |

| CRRT settings | ||||||||||

| CRRT mode | CVVH | CVVHD | CVVH (n = 5), CVVHDF (n = 5) | CVVH (n = 10), CVVHDF (n = 10) | CVVH | CVVH (n = 6), CVVHDF (n = 6) | CVVHDF | CVVHDF | CVVH | CVVH (n = 45), CVVHD (n = 4), CVVHDF (n = 35) |

| CRRT dose (median [IQR]) (mL/h/kg) | 32.3 (29.0–36.3) | 13.6 (12.8–14.4) | 25.4 (21.2–30.1) | 28.0 (19.6–33.4) | 20 (16.5–21.1) | 5.0 (4.7–5.3) | 16.6 (14.8–20.1) | 25.0 | 55.7 (43.7–65.5) | 25.0 (15.9–33.6) |

The study by Isla et al. (17) contained 6 trauma patients, and the CLCR for trauma patients was 5.85 L/h (interquartile range [IQR], 4.72 to 6.36 L/h). Anuric, 24-h urine output of <100 mL; NR, not reported.

Population PK analysis.

The time course of meropenem concentrations was well described by a two-compartment model, providing an objective function value (OFV) drop of 164.89 points, compared to the one-compartment model. The residual variability was best depicted by the model with combined proportional and additive errors. A splitting of total clearance (CLtotal) into body clearance (CLbody) and CRRT clearance (CLCRRT) significantly improved the model, resulting in a reduction of OFV by 198.07 points. Additionally, a shared interindividual variability (IIV) was employed for the central volume of distribution (V1) and the peripheral volume of distribution (V2), and the IIV of intercompartmental clearance (Q) was fixed to zero (an OFV rise of 4.49 points) to achieve adequate numeric stability of the model.

In univariate analyses, age, sex, and CRRT type were found to be insignificant (P > 0.05) for PK parameters, and body weight (for CLbody) and patient type (for CLbody and V1) were identified as significant covariates. In the subsequent forward addition screening, body weight and patient type were retained as significant covariates for CLbody. During the subsequent backward elimination step, body weight was excluded for CLbody (P > 0.001), and only patient type remained as the covariate of CLbody in the model. The resulting typical CLbody in trauma patients was 117.0 L/h, which was far higher than the estimate (62.9 L/h) reported in the original study by Isla et al. (17) based on dense PK points. Considering that only peak and trough concentrations were available for the included trauma patients in our analysis, the typical CLbody for trauma patients was fixed at the prior estimate (62.9 L/h, resulting in an increase of OFV by 5.55 points). The CLtotal in the final PK model was described by equation 1:

| (1) |

where is the typical value of endogenous clearance. represents the typical CLbody in the non-trauma patient population, and indicates the typical CLbody in the trauma patient population. is the IIV of .

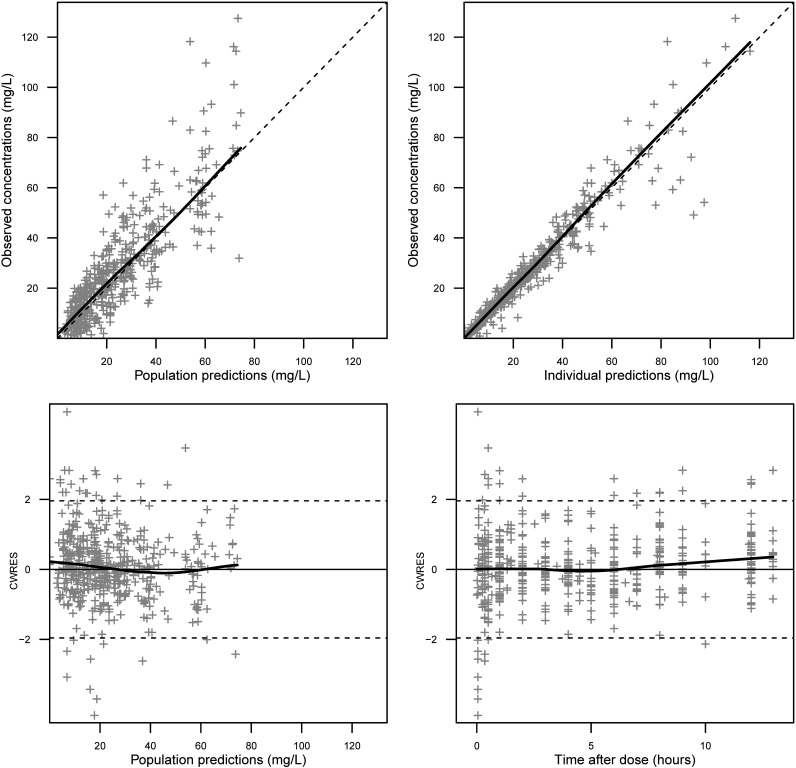

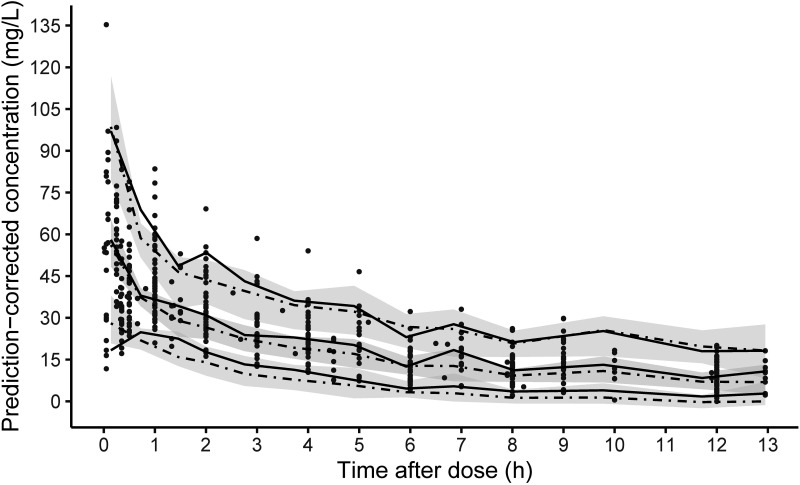

The population PK parameter estimates obtained from the “base” model (without trauma patients) and the final model (including trauma patients) are listed in Table 2. The parameters were accurately estimated, and satisfactory parameter precision was further confirmed by the nonparametric bootstrap results (Table 2). The goodness-of-fit (GOF) plots for the final model are presented in Fig. 1. The prediction-corrected visual predictive check (pc-VPC) plot to assess the predictive performance of the model is shown in Fig. 2, with the 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles of the observed concentrations being close to the respective percentiles of the simulated concentrations. These diagnostic plots showed that our final model is of reliable robustness and good predictive performance.

TABLE 2.

Population PK estimates for the final model and bootstrap results

| Parametera | Base model estimate (RSE [%]) [shrinkage [%]] | Final model estimate (RSE [%]) [shrinkage [%]] | Bootstrap median (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | |||

| (L/h) | 3.02 (7.4) | 3.03 (7.4) | 2.99 (2.57–3.50) |

| (L/h) | 62.9 fixed | ||

| (L) | 14.1 (8.1) | 14.2 (7.9) | 14.3 (12.04–17.58) |

| (L/h) | 16.2 (22.7) | 15.9 (21.3) | 15.1 (6.16–25.92) |

| (L) | 14 (8.0) | 14.6 (8.1) | 15.5 (12.32–19.01) |

| IIV | |||

| (CV [%]) | 59.3 (18.6) [13.2] | 69.9 (19.7) [10.4] | 71.1 (55.6–91.6) |

| (CV [%]) | 41.6 (20.9) [19.2] | 39.7 (16.9) [21.2] | 41.6 (32.4–60.2) |

| (CV [%]) | 32.9 (38.3) [51.3] | 39.7 [52.7] | 41.6 |

| Residual variability | |||

| Proportional error (CV [%]) | 15.0 (28) [12.3] | 15.3 (31.4) [13.1] | 15.9 (10.0–21.9) |

| Additive error (mg/L) | 2.45 (49.8) [12.3] | 2.0 (75.0) [13.1] | 1.56 (0.09–5.24) |

, typical value of endogenous clearance in non-trauma patients; , typical value of endogenous clearance in trauma patients; , typical V1 value; , typical Q value; , typical V2 value; CV, coefficient of variation, calculated according to , where is the variance of IIV.

CI, confidence interval.

FIG 1.

GOF plots for the final population PK model of meropenem. (Top left) Observed concentrations versus population predictions for meropenem. (Top right) Observed concentrations versus individual predictions for meropenem. (Bottom left) Conditional weighted residuals (CWRES) versus population predictions of meropenem concentrations. (Bottom right) CWRES versus time after dose. Gray crosses represent meropenem concentrations or CWRES values. The solid black lines depict the correlations of our observations and predictions; the dashed lines are reference lines of unity or CWRES borders.

FIG 2.

pc-VPC plot for the final population PK model of meropenem in CRRT patients. The black dots represent the observed meropenem concentrations. The solid and dashed lines represent the 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles for the observed and simulated data, respectively. The shaded areas represent the 90% prediction intervals.

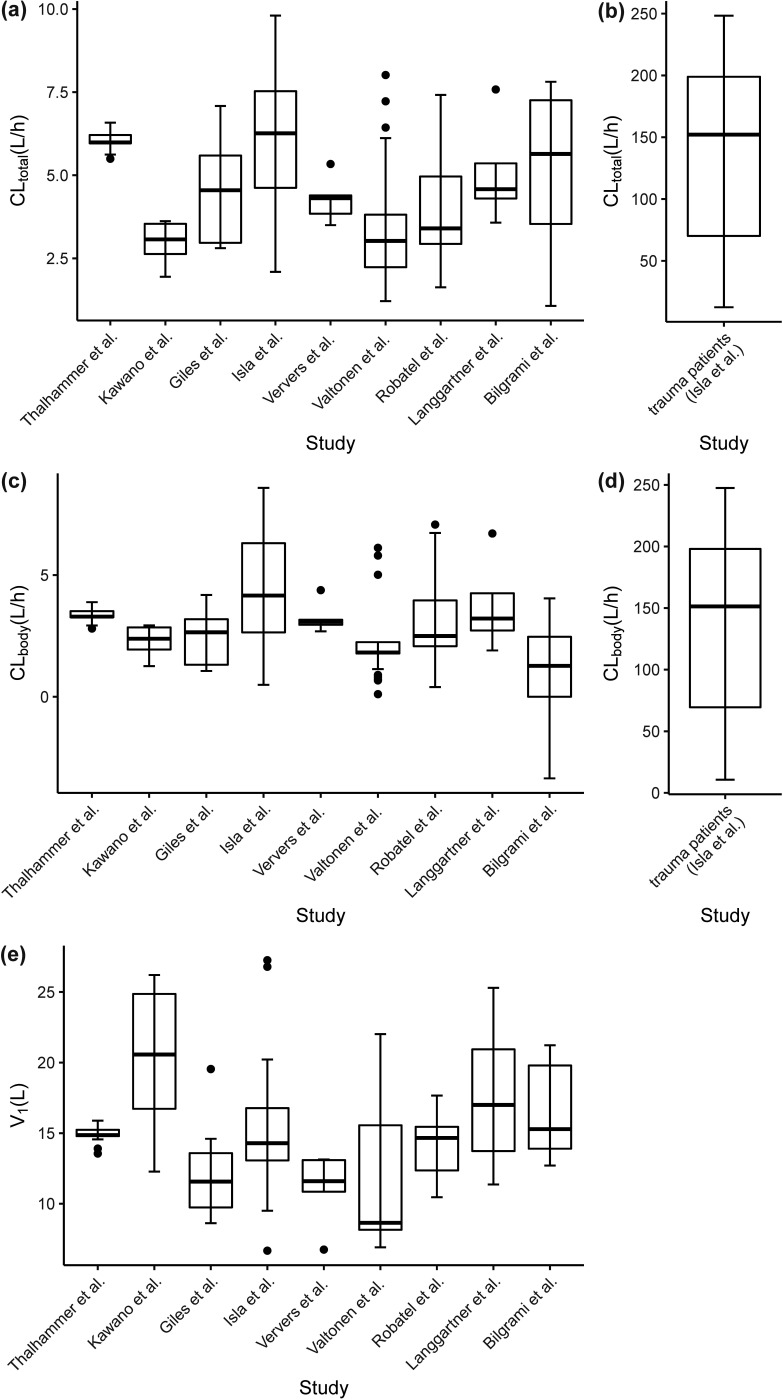

Figure 3 shows the boxplots of model-predicted individual CLtotal, CLbody, and V1 values for meropenem in different studies. CLtotal, CLbody, and V1 values for meropenem all showed considerable discrepancy among the studies, which is also evidenced by the estimated high variability (Table 2) of CLbody (69.9% in non-trauma patients) and V1 (39.7%). For instance, the median values of CLtotal and CLbody in non-trauma patients were in ranges of 3.06 to 6.07 L/h (Fig. 3a) and 1.27 to 4.15 L/h (Fig. 3c), respectively, and the median V1 in different studies ranged from 8.43 to 20.84 L (Fig. 3e). The typical CLbody (62.9 L/h) (Fig. 3b) in trauma patients was increased by about 20-fold in comparison to that in the non-trauma patient population (typical CLbody of 3.03 L/h). The median contribution of CLCRRT to CLtotal in non-trauma patients was 34.0%, with an interquartile range of 20.1% to 46.7%, whereas the contribution of CLCRRT to CLtotal in trauma patients was less than 1.0%.

FIG 3.

Boxplots for the post hoc individual CLtotal, CLbody, and V1 values for meropenem across different CRRT studies. (a and b) Model-predicted CLtotal for non-trauma patients (a) and trauma patients (b). (c and d) Model-predicted CLbody for non-trauma patients (c) and trauma patients (d). (e) Predicted V1 values in different studies. In the boxplots, the lower boundary of the box indicates the 25th percentile, the line within the box marks the 50th percentile, and the upper boundary of the box represents the 75th percentile. Whiskers above and below the box indicate 1.5 times the interquartile range below the 25th percentile and above the 75th percentile, respectively. Points above and below the whiskers are defined as outliers.

Simulations and dosing recommendations.

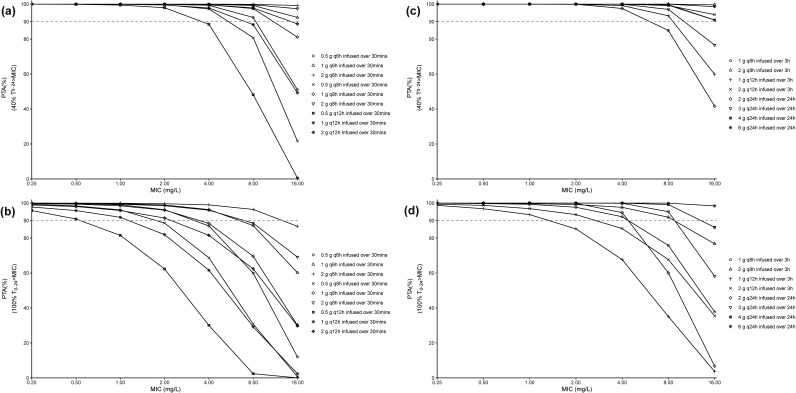

The PTA versus MIC profiles for different meropenem dosing regimens in non-trauma patients receiving a CRRT dose of 35 mL/h/kg are shown in Fig. 4. For a PK/PD target of 40% fT>MIC (Fig. 4a), almost all of the simulated short-term infusion dosing regimens reached desirable PTA values (PTA values of >90%) against pathogens with MICs of ≤4 mg/L, and only 0.5 g meropenem every 8 h (q8h) to every 12 h (q12h) and 1 g meropenem q12h failed to obtain satisfactory PTAs in patients infected by pathogens with MICs of 8 mg/L. All of the prolonged and continuous dosing regimens reached desirable PTAs (PTA values of 90%) against pathogens with MICs of ≤4 mg/L, while only 2 g every 24 h (q24h) infused over 24 h was unable to achieve adequate PTAs against pathogens with MICs of 8 mg/L (Fig. 4c). For a target of 100% fT>MIC (Fig. 4b), the PTA versus MIC profiles for the meropenem dosing regimens exhibited significant differences. For instance, only some of the simulated short-term infusion dosing regimens (1 g every 6 h [q6h] and 2 g q6 to q8h) could achieve desirable PTAs against pathogens with MICs of ≤4 mg/L. The prolonged infusion (3 h) of 2 g q12h could obtain satisfactory PTAs for pathogens with MICs of ≤2 mg/L, 1 g q8h infused over 3 h and 2 g q24h infused over 24 h achieved desirable PTAs (PTA values of >90%) against pathogens with MICs of ≤4 mg/L, and 2 g q8h and 3 to 6 g q24h were required for pathogens with MICs of 8 mg/L (Fig. 4d). The PTA results for meropenem dosing regimens in non-trauma patients receiving CRRT doses of 25 and 50 mL/h/kg are shown in Fig. SA1 to SA4 in the supplemental material. As can be seen, the PTAs for meropenem dosing regimens under different CRRT dose intensities are generally comparable, suggesting limited impact of CRRT dose on the 40% and 100% fT>MIC PTAs for meropenem. In addition, the PTA results for meropenem dosing regimens in trauma patients receiving a CRRT dose of 35 mL/h/kg are displayed in Fig. SA5 and SA6 in the supplemental material. In contrast to the non-trauma patients, only 3 to 4 g q24h infused over 24 h could safely provide an optimal PTA against pathogens with MICs of ≤0.5 mg/L in trauma patients.

FIG 4.

PTA versus MIC profiles for different meropenem dosing regimens in non-trauma patients receiving a CRRT dose of 35 mL/h/kg based on the PK/PD targets of 40% fT>MIC (a and c) and 100% fT>MIC (b and d). The dashed horizontal lines represent a PTA of 90%.

The predicted risk of toxicity for different meropenem dosing regimens is listed in Table 3. The associated risk of toxicities for short-term infusion of 2 g q6h and continuous infusion of 6 g q24h are quite high (21.58 to 57.36% and 20.09 to 56.65%, respectively), regardless of the CRRT doses (25 to 50 mL/h/kg). An extension of the dosing interval or infusion time (2 g q8h by short-term infusion and 2 g q8h by prolonged infusion) still produced unacceptable risks of toxicity (11.94 to 26.38% and 14.59 to 26.81%, respectively), except for the CRRT dose of 50 mL/h/kg. However, negligible probabilities of reaching the neurotoxicity and nephrotoxicity thresholds were found for other meropenem regimens.

TABLE 3.

Risk of toxicity for different meropenem dosing regimens in non-trauma patients with different CRRT doses

| Infusion type and dosing regimen | Risk of toxicity (%) with CRRT dose of: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 25 mL/h/kg | 35 mL/h/kg | 50 mL/h/kg | |

| Short-term infusion (30 min) | |||

| 0.5 g q6h | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 g q6h | 7.03 | 0.78 | 0 |

| 2 g q6h | 57.36 | 44.34 | 21.58 |

| 0.5 g q8h | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 g q8h | 0.36 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 g q8h | 26.38 | 11.94 | 0.9 |

| 0.5 g q8h | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 g q12h | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 g q12h | 1.95 | 0.04 | 0 |

| Prolonged infusion (3 h) | |||

| 1 g q8h | 0.39 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 g q8h | 26.81 | 14.59 | 0.84 |

| 1 g q12h | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 g q12h | 1.96 | 0 | 0 |

| Continuous infusion | |||

| 2 g q24h | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 g q24h | 0.72 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 g q24h | 12.70 | 3.57 | 0 |

| 6 g q24h | 56.65 | 43.82 | 20.09 |

DISCUSSION

In the present PK analysis, the typical endogenous clearance of meropenem in non-trauma CRRT patients is 3.03 L/h, with a range of 1.27 to 4.15 L/h. The endogenous clearance in non-trauma CRRT patients is markedly lower than those in healthy subjects (15.5 L/h) and critically ill non-CRRT patients (9.25 to 9.89 L/h) (3, 16, 18). This is likely due to dramatically decreased renal function in critically ill CRRT patients, among whom AKI is often present. The total volume of distribution of meropenem in CRRT patients (including non-trauma and trauma patients) is 28.8 L, with a range of 19.6 to 35.2 L/h, which is about 34% higher than that of healthy subjects (21 L). The increased volume of distribution in critically ill CRRT patients could be explained by the sepsis-induced capillary leak syndrome and treatment-related fluid overload (19, 20). The observed high volume of distribution of meropenem in critically ill CRRT patients is in good agreement with previously reported values for critically ill CRRT patients (e.g., 24.0 L in the study by Ehmann et al. and 48.1 L in the study by Dhaese et al. [16, 18]). Generally, the estimated CLtotal and total volume of distribution for meropenem are in good agreement with the reported values (see Table SA1 in the supplemental material).

Our covariate analysis revealed that trauma patients had dramatically elevated endogenous clearance, compared with non-trauma patients. This is in line with the earlier work by Isla et al. (21), in which the reported meropenem clearance varied extensively from septic patients to severely polytraumatized patients. This phenomenon can be explained by the fact that trauma patients have an increased cardiac output with a subsequent increase in renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate during the hypermetabolic phase (22), which in turn lead to at least preserved or increased clearance for renally excreted drugs. This kind of renal hyperfiltration physiology (called ARC when the creatinine clearance [CLCR] is >130 mL/min) has a profound effect on the drug’s renal clearance in trauma patients undergoing CRRT, and it is also frequently observed in non-CRRT trauma patients. The increased drug clearance in this kind of patient population is also observed for other carbapenems, such as imipenem (23). Our included non-trauma CRRT patients mostly presented with AKI and had an anuric status; therefore, the impact of residual diuresis was not considered. Patients with anuria often demonstrate minimal residual renal function, and this implies that the CLCR values for these patients usually do not differ too much. Indeed, the reported CLCR values for the non-trauma CRRT patients in the study by Isla et al. (21) were mostly less than 30 mL/min. Therefore, in this study we finally determined a trauma disease effect on the meropenem clearance by identification of non-trauma and trauma subpopulations. The non-trauma patient population represents the AKI patients with anuria (minimal residual renal function), and the trauma patients represent the critically ill patient population with preserved renal clearance/ARC. In the previous study by Isla et al. (21), a trauma effect on V1 was identified, and the polytraumatized patients had a 4.4-fold greater V1 (69.5 L), compared with that of the septic patients (15.7 L). In our pooled study, this covariate relationship was also found during the univariate analyses. However, the covariate effect disappeared after the inclusion of the trauma effect on the endogenous clearance of meropenem. To our knowledge, the trauma-induced increase in glomerular filtration rate is widely recognized, while the trauma effect on the volume of distribution is scarcely reported.

In the Monte Carlo simulation, the PK/PD targets of 40% fT>MIC and 100% fT>MIC were considered. The former target is a traditional efficacy marker for patients with moderate or mild infection, while the latter target is advocated for critically ill patients to ensure maximal bactericidal activity. Some experimental data demonstrated that achievement of the more stringent target of 100% fT>MIC was related to improved patient outcomes among critically ill patients (24). Our simulation-based analysis demonstrated that the target of 40% fT>MIC (MICs of ≤4 mg/L) could be easily achieved with all of the studied dosing regimens for meropenem, while only some of the dosing regimens (1 g q6h by short-term infusion, 1 g q8h by prolonged infusion, and 2 to 4 g q24h by continuous infusion) could achieve the target of 100% fT>MIC (MICs of ≤4 mg/L). Meropenem dosing regimens of 2 g q6 to q8 h by short-term infusion, 2 g q8h by prolonged infusion, and 6 g q24h by continuous infusion are not suggested for critically ill CRRT patients due to the predicted high risk of toxicity. In our opinion, continuous infusion of 3 to 4 g meropenem q24h may be an optimal choice for CRRT patients with trauma and non-trauma CRRT patients infected with resistant pathogens (MICs of 8 mg/L), providing desirable PK/PD PTA and minimal risk of toxicity. It should be noted that our dosing recommendation may fit only for CRRT patients with anuria (CLtotal ranged from 3.06 L/h to 6.07 L/h), and extrapolation of our dosing findings to other CRRT patients with different characteristics should be performed with caution.

There are several limitations to acknowledge in this study. First, most of our concentration data were obtained by the digitization approach. Although this method has proved to be valid to generate precise data (25), the time points obtained in the forepart of PK curves (e.g., 0 to 30 min) are less precise. In our study, the time points obtained were further corrected with the sampling schedules mentioned in the original publications. Second, a significant proportion of data for some important patient characteristics, such as CLCR and residual diuresis, were missing due to the meta-analysis nature based on the reported PK studies. These missing data were either not reported or not recorded in the original studies. The relevant missing data prohibited us from performing a detailed evaluation of the impact of residual renal function on the PK/PD of meropenem in CRRT patients. However, the included non-trauma CRRT patients mostly presented with AKI and anuria; therefore, the difference in renal function in this relatively homogeneous subpopulation may be less pronounced. Third, although a trauma effect on the endogenous clearance of meropenem was identified, this covariate effect was established based on only six trauma CRRT patients with 12 concentration points. Future clinical PK studies in this patient population are needed to accurately characterize the trauma effect on the PK/PD of meropenem. Fourth, the extracorporeal CLCRRT was assumed to be mainly determined by the effluent flow rate, and this allowed us to determine the impact of different CRRT modalities in a unified approach. This means that the potential difference in solute removal capacity for different CRRT modalities was not considered. The impact of CRRT modality on the solute removal capacity was deemed minimal or clinically irrelevant, and this has been proved for several antibiotics (26, 27).

In conclusion, a population meropenem PK model in 78 critically ill CRRT patients was developed, and trauma was identified as a significant modifier of the endogenous clearance of meropenem. Simulation-based analysis demonstrated that 1 g q6h infused over 30 min, 1 g q8h infused over 3 h, and 2 to 4 g q24h infused over 24 h for meropenem might be suitable options for empirical infection treatment in non-trauma CRRT patients with anuria, while continuous infusion of 3 to 4 g q24h is suitable for trauma CRRT patients (MICs of ≤0.5 mg/L).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study data.

An extensive literature search was undertaken via PubMed (up to 30 September 2021) to find published meropenem PK studies in critically ill patients undergoing CRRT. The abstract and full text of the collected literature were manually examined, and the reference lists of identified PK studies were also screened. The identified publications containing specific dosing information, sampling schemes, CRRT settings (e.g., effluent dose), and individual concentration data were included for the present PK meta-analysis. Studies with unclear/missing dosing and/or concentration sampling schedules were excluded. Nine publications were eligible for inclusion, and an overview of these studies is presented in Table 1 (17, 28–35). All studies obtained necessary institutional review board approval, as declared in the original papers. Individual plasma concentration data were either directly obtained from concentration observations in tables or indirectly digitized from meropenem concentration-time curves by the WebPlotDigitizer (version 4.1). The sources of detailed concentration data are summarized in Table SA1 in the supplemental material. In total, 501 concentration data points were obtained.

Quantification of CLCRRT.

In general, the extracorporeal clearance (CLCRRT) (in liters per hour) of a drug for different CRRT modalities is determined by the effluent flow rate (a combination of ultrafiltrate flow rate and dialysate flow rate or alone) and sieving coefficient (Sc)/saturation coefficient (Sd). The specific equations for CLCRRT calculation depend on the CRRT modality (36). For CVVH, the solute is removed by diffusion, and the CLCRRT is dependent on the ultrafiltrate flow rate (Quf) (in milliliters per hour) and Sc (equation 2). The CVVHD modality primarily removes the solute by convection, and the CLCRRT is determined by the dialysate flow rate (Qd) (in milliliters per hour) and Sd (equation 3). CVVHDF combines the mechanisms of diffusion and convection, and the CLCRRT is calculated with Qd, Quf, and Sd (equation 4). In clinical practice, the effluent flow rate is usually indexed to body weight (expressed in milliliters per hour per kilogram), and the body weight-based effluent flow rate is usually termed the CRRT dose. Sc and Sd are close to each other for a specific drug.

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

The CLCRRT was calculated for each patient. For the studies by Kawano et al. (29) and Valtonen et al. (32), the Sc and Sd values were not reported, and the mean Sc value (0.80) from the study by Isla et al. (17) was employed.

Population PK modeling.

Meropenem concentration data were analyzed using the first-order conditional estimation with interaction (FOCE-I) algorithm in NONMEM (version 7.3; Icon Development Solutions, Ellicott City, MD, USA), assisted by Perl-speaks-NONMEM (PsN) (version 4.60; Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden) and the Pirana Modeling Workbench (version 2.9.9; Pirana Software & Consulting BV). R software (version 4.0.5; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was employed for data processing and plotting.

One- and two-compartmental models were tested as the structural PK model. Meropenem CLtotal was modeled as a sum of endogenous clearance (CLbody) and CLCRRT. CLbody was estimated based on the concentration data, and CLCRRT was individually calculated as noted above. IIV values for the typical population parameter estimates were assumed to be log-normally distributed. Interoccasion variability (IOV) was not considered during the modeling because the dosing frequencies varied considerably in each component data set. Residual unexplained variability was modeled using a combined proportional and additive error model.

After determination of the structural model, the relevant demographic and CRRT characteristics of the study patients were tested for inclusion as covariates in the population PK model. Age and body weight were the continuous covariates evaluated. Sex, patient type (trauma or non-trauma), and CRRT modality were the categorical covariates tested. The covariates of CLCR, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score, and urine output (anuric or nonanuric) were not examined because large proportions of individual-level data were missing. The plots of empirical Bayes estimates of PK parameters versus subjects’ covariates were first examined for observable trends. The effects of potential covariates found during the graphic analysis were then investigated using the forward addition (P < 0.05) and backward elimination (P < 0.001) stepwise approach.

Model development and selection were guided by OFV, condition number, relative standard error (RSE) of the parameter estimates, and GOF plots (37). A decrease of 3.84 OFV points was statistically significant (P < 0.05) for the inclusion of a single parameter. The final PK model was internally validated using pc-VPC for the model’s predictive ability (1,000 virtual data sets), and parameter uncertainty was checked by bootstrap analysis (resampled 1,000 times).

Dosing simulations.

Monte Carlo simulations were performed by reparametrizing the final PK model using the mrgsolve package (version 0.10.0) in R to explore the impact of dosing regimens, CRRT doses, and retained covariates on the PTA and risk of toxicity for meropenem. Empirical meropenem dosing regimens of 0.5 to 2 g q6h to q12h infused over 30 min, 1 to 2 g q8h to q12h infused over 3 h, and 2 to 6 g q24h infused over 24 h (including a 1-g loading dose) were separately simulated under three different CRRT doses (25, 35, and 50 mL/h/kg). For each scenario, 10,000 virtual subjects with a fixed body weight of 75 kg (median value for the pooled CRRT patients) were simulated. PK/PD targets of 40% fT>MIC and 100% fT>MIC were used as surrogate marker for efficacy, and a trough concentration of ≥45 mg/L was set as the toxicity threshold. A pathogen MIC range of 0.25 to 16 mg/L was considered based on the MIC distributions for Pseudomonas spp. and Acinetobacter spp. obtained from the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) database (38). The PTA and risk of toxicity were computed based on predicted meropenem concentrations at steady state, and a PTA of ≥90% was deemed a desirable PTA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (projects 82073940 and 82104306), the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (project 2021JJ40815), and the Scientific Research Fund of the Hunan Provincial Education Department (grant 21B0013).

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, Hotchkiss RS, Levy MM, Marshall JC, Martin GS, Opal SM, Rubenfeld GD, van der Poll T, Vincent JL, Angus DC. 2016. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 315:801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hawkey PM, Livermore DM. 2012. Carbapenem antibiotics for serious infections. BMJ 344:e3236. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mouton JW, van den Anker JN. 1995. Meropenem clinical pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacokinet 28:275–286. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199528040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rizk ML, Bhavnani SM, Drusano G, Dane A, Eakin AE, Guina T, Jang SH, Tomayko JF, Wang J, Zhuang L, Lodise TP. 2019. Considerations for dose selection and clinical pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics for the development of antibacterial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 63:e02309-18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02309-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asin-Prieto E, Rodriguez-Gascon A, Isla A. 2015. Applications of the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) analysis of antimicrobial agents. J Infect Chemother 21:319–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imani S, Buscher H, Marriott D, Gentili S, Sandaradura I. 2017. Too much of a good thing: a retrospective study of β-lactam concentration-toxicity relationships. J Antimicrob Chemother 72:2891–2897. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peerapornratana S, Manrique-Caballero CL, Gomez H, Kellum JA. 2019. Acute kidney injury from sepsis: current concepts, epidemiology, pathophysiology, prevention and treatment. Kidney Int 96:1083–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2019.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoste EA, Lameire NH, Vanholder RC, Benoit DD, Decruyenaere JM, Colardyn FA. 2003. Acute renal failure in patients with sepsis in a surgical ICU: predictive factors, incidence, comorbidity, and outcome. J Am Soc Nephrol 14:1022–1030. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000059863.48590.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Udy AA, Baptista JP, Lim NL, Joynt GM, Jarrett P, Wockner L, Boots RJ, Lipman J. 2014. Augmented renal clearance in the ICU: results of a multicenter observational study of renal function in critically ill patients with normal plasma creatinine concentrations. Crit Care Med 42:520–527. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.RENAL Study Investigators. 2008. Renal replacement therapy for acute kidney injury in Australian and New Zealand intensive care units: a practice survey. Crit Care Resusc 10:225–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts JA, Joynt GM, Lee A, Choi G, Bellomo R, Kanji S, Mudaliar MY, Peake SL, Stephens D, Taccone FS, Ulldemolins M, Valkonen MM, Agbeve J, Baptista JP, Bekos V, Boidin C, Brinkmann A, Buizen L, Castro P, Cole CL, Creteur J, De Waele JJ, Deans R, Eastwood GM, Escobar L, Gomersall C, Gresham R, Jamal JA, Kluge S, Konig C, Koulouras VP, Lassig-Smith M, Laterre PF, Lei K, Leung P, Lefrant JY, Llaurado-Serra M, Martin-Loeches I, Mat Nor MB, Ostermann M, Parker SL, Rello J, Roberts DM, Roberts MS, Richards B, Rodriguez A, Roehr AC, Roger C, Seoane L, Sinnollareddy M, Sousa E, Soy D, Spring A, Starr T, Thomas J, Turnidge J, Wallis SC, Williams T, Wittebole X, Zikou XT, Paul SK, Lipman J. 2021. The effect of renal replacement therapy and antibiotic dose on antibiotic concentrations in critically ill patients: data from the multinational Sampling Antibiotics in Renal Replacement Therapy Study. Clin Infect Dis 72:1369–1378. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein SL, Nolin TD. 2014. Lack of drug dosing guidelines for critically ill patients receiving continuous renal replacement therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther 96:159–161. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2014.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westermann I, Gastine S, Muller C, Rudolph W, Peters F, Bloos F, Pletz M, Hagel S. 2021. Population pharmacokinetics and probability of target attainment in patients with sepsis under renal replacement therapy receiving continuous infusion of meropenem: sustained low-efficiency dialysis and continuous veno-venous haemodialysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 87:4293–4303. doi: 10.1111/bcp.14846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ulldemolins M, Soy D, Llaurado-Serra M, Vaquer S, Castro P, Rodriguez AH, Pontes C, Calvo G, Torres A, Martin-Loeches I. 2015. Meropenem population pharmacokinetics in critically ill patients with septic shock and continuous renal replacement therapy: influence of residual diuresis on dose requirements. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:5520–5528. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00712-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Padulles Zamora A, Juvany Roig R, Leiva Badosa E, Sabater Riera J, Perez Fernandez XL, Cardenas Campos P, Rigo Bonin R, Alia Ramos P, Tubau Quintano F, Sospedra Martinez E, Colom Codina H. 2019. Optimized meropenem dosage regimens using a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic population approach in patients undergoing continuous venovenous haemodiafiltration with high-adsorbent membrane. J Antimicrob Chemother 74:2979–2983. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dhaese SAM, Farkas A, Colin P, Lipman J, Stove V, Verstraete AG, Roberts JA, De Waele JJ. 2019. Population pharmacokinetics and evaluation of the predictive performance of pharmacokinetic models in critically ill patients receiving continuous infusion meropenem: a comparison of eight pharmacokinetic models. J Antimicrob Chemother 74:432–441. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Isla A, Maynar J, Sanchez-Izquierdo JA, Gascon AR, Arzuaga A, Corral E, Pedraz JL. 2005. Meropenem and continuous renal replacement therapy: in vitro permeability of 2 continuous renal replacement therapy membranes and influence of patient renal function on the pharmacokinetics in critically ill patients. J Clin Pharmacol 45:1294–1304. doi: 10.1177/0091270005280583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ehmann L, Zoller M, Minichmayr IK, Scharf C, Huisinga W, Zander J, Kloft C. 2019. Development of a dosing algorithm for meropenem in critically ill patients based on a population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic analysis. Int J Antimicrob Agents 54:309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2019.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Giantomasso D, May CN, Bellomo R. 2003. Vital organ blood flow during hyperdynamic sepsis. Chest 124:1053–1059. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.3.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goncalves-Pereira J, Povoa P. 2011. Antibiotics in critically ill patients: a systematic review of the pharmacokinetics of β-lactams. Crit Care 15:R206. doi: 10.1186/cc10441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Isla A, Rodriguez-Gascon A, Troconiz IF, Bueno L, Solinis MA, Maynar J, Sanchez-Izquierdo JA, Pedraz JL. 2008. Population pharmacokinetics of meropenem in critically ill patients undergoing continuous renal replacement therapy. Clin Pharmacokinet 47:173–180. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200847030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams FN, Herndon DN, Jeschke MG. 2009. The hypermetabolic response to burn injury and interventions to modify this response. Clin Plast Surg 36:583–596. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hobbs AL, Shea KM, Roberts KM, Daley MJ. 2015. Implications of augmented renal clearance on drug dosing in critically ill patients: a focus on antibiotics. Pharmacotherapy 35:1063–1075. doi: 10.1002/phar.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scharf C, Liebchen U, Paal M, Taubert M, Vogeser M, Irlbeck M, Zoller M, Schroeder I. 2020. The higher the better? Defining the optimal beta-lactam target for critically ill patients to reach infection resolution and improve outcome. j Intensive Care 8:86–95. doi: 10.1186/s40560-020-00504-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wojtyniak JG, Britz H, Selzer D, Schwab M, Lehr T. 2020. Data digitizing: accurate and precise data extraction for quantitative systems pharmacology and physiologically-based pharmacokinetic modeling. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol 9:322–331. doi: 10.1002/psp4.12511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts DM, Liu X, Roberts JA, Nair P, Cole L, Roberts MS, Lipman J, Bellomo R. 2015. A multicenter study on the effect of continuous hemodiafiltration intensity on antibiotic pharmacokinetics. Crit Care 19:84–92. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0818-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roger C, Wallis SC, Muller L, Saissi G, Lipman J, Bruggemann RJ, Lefrant JY, Roberts JA. 2017. Caspofungin population pharmacokinetics in critically ill patients undergoing continuous veno-venous haemofiltration or haemodiafiltration. Clin Pharmacokinet 56:1057–1068. doi: 10.1007/s40262-016-0495-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thalhammer F, Schenk P, Burgmann H, El Menyawi I, Hollenstein UM, Rosenkranz AR, Sunder-Plassmann G, Breyer S, Ratheiser K. 1998. Single-dose pharmacokinetics of meropenem during continuous venovenous hemofiltration. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 42:2417–2420. doi: 10.1128/AAC.42.9.2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawano S, Matsumoto K, Hara R, Kuroda Y, Ikawa K, Morikawa N, Horino T, Hori S, Kizu J. 2015. Pharmacokinetics and dosing estimation of meropenem in Japanese patients receiving continuous venovenous hemodialysis. J Infect Chemother 21:476–478. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giles LJ, Jennings AC, Thomson AH, Creed G, Beale RJ, McLuckie A. 2000. Pharmacokinetics of meropenem in intensive care unit patients receiving continuous veno-venous hemofiltration or hemodiafiltration. Crit Care Med 28:632–637. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200003000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ververs TF, van Dijk A, Vinks SA, Blankestijn PJ, Savelkoul JF, Meulenbelt J, Boereboom FT. 2000. Pharmacokinetics and dosing regimen of meropenem in critically ill patients receiving continuous venovenous hemofiltration. Crit Care Med 28:3412–3416. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200010000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valtonen M, Tiula E, Backman JT, Neuvonen PJ. 2000. Elimination of meropenem during continuous veno-venous haemofiltration and haemodiafiltration in patients with acute renal failure. J Antimicrob Chemother 45:701–704. doi: 10.1093/jac/45.5.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robatel C, Decosterd LA, Biollaz J, Eckert P, Schaller MD, Buclin T. 2003. Pharmacokinetics and dosage adaptation of meropenem during continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration in critically ill patients. J Clin Pharmacol 43:1329–1340. doi: 10.1177/0091270003260286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Langgartner J, Vasold A, Gluck T, Reng M, Kees F. 2008. Pharmacokinetics of meropenem during intermittent and continuous intravenous application in patients treated by continuous renal replacement therapy. Intensive Care Med 34:1091–1096. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bilgrami I, Roberts JA, Wallis SC, Thomas J, Davis J, Fowler S, Goldrick PB, Lipman J. 2010. Meropenem dosing in critically ill patients with sepsis receiving high-volume continuous venovenous hemofiltration. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:2974–2978. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01582-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schetz M. 2007. Drug dosing in continuous renal replacement therapy: general rules. Curr Opin Crit Care 13:645–651. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282f0a3d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nguyen TH, Mouksassi MS, Holford N, Al-Huniti N, Freedman I, Hooker AC, John J, Karlsson MO, Mould DR, Perez Ruixo JJ, Plan EL, Savic R, van Hasselt JG, Weber B, Zhou C, Comets E, Mentre F, Model Evaluation Group of the International Society of Pharmacometrics Best Practice C . 2017. Model evaluation of continuous data pharmacometric models: metrics and graphics. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol 6:87–109. doi: 10.1002/psp4.12161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 2021. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters, version 11.0. https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/v_11.0_Breakpoint_Tables.pdf. Accessed 15 August 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table SA1 and Fig. SA1 to SA6. Download aac.00822-22-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 1.1 MB (1.1MB, pdf)

Data Set S1. Download aac.00822-22-s0002.xlsx, XLSX file, 0.08 MB (79.9KB, xlsx)