Abstract

The burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) on society is increasing. Healthcare systems should support patients with COPD in achieving an optimal quality of life, while limiting the costs of care. As a consequence, a shift from hospital care to home care seems inevitable. Therefore, patients will have to rely to a greater extent on informal caregivers. Patients with COPD as well as their informal caregivers are confronted with multiple limitations in activities of daily living. The presence of an informal caregiver is important to provide practical help and emotional support. However, caregivers can be overprotective, which can make patients more dependent. Informal caregiving may lead to symptoms of anxiety, depression, social isolation and a changed relationship with the patient. The caregivers' subjective burden is a major determinant of the impact of caregiving. Therefore, the caregiver's perception of the patient's health is an important factor. This article reviews the current knowledge about these informal caregivers of patients with COPD, the impact of COPD on their lives and their perception of the patient's health status.

Short abstract

Informal caregivers play important roles: their needs should be part of research and clinical care for COPD patients http://ow.ly/PSl7F

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality throughout the world [1]. Its prevalence is expected to increase in the coming decades [2], due to the ageing population, the continued exposure to known COPD risk factors, and disease-specific life-enhancing treatments [1]. Therefore, the societal and economic burden of COPD is expected to increase.

Dyspnoea is a cardinal symptom in patients with COPD, which, together with fatigue, limits patients' domestic activities of daily living, physical activity levels and health status [3, 4]. Furthermore, 57% of patients with severe-to-very severe COPD have morning symptoms that limit their activities like washing or dressing themselves [5]. Patients with COPD may become more care dependent over time, and most probably will rely to a greater extent on (informal) caregivers within their home environment [6, 7]. Therefore, the role of the informal caregiver will probably become more essential in COPD management in the near future. Caregivers, however, face an increasing workload in caring for a loved one, on top of their existing responsibilities. Caregiver responsibilities may include medication and symptom management, providing physical, psychological and emotional support, physical work like cleaning, and awareness of hygiene and nutritional needs [8].

To date, the role of the informal caregiver of patients with COPD is underrepresented in international COPD documents. For example, the online version of the latest Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease document [9], only briefly mentions the informal caregiver in aspects such as the correct use of medication, advance care planning, indirect disease-related costs, and impact of the disease on the patient's family.

This article reviews the current knowledge about informal caregiving in patients with COPD, including the role of informal caregivers, the impact on informal caregivers, and the caregivers' perception of the patient's health.

Role of informal caregivers

Informal caregivers are of major importance for patients with COPD, as the majority of home care is provided by family and friends instead of healthcare professionals [10]. To date, more than 70% of the COPD patients referred for pulmonary rehabilitation have one or more informal caregivers. 40% of these patients had a COPD-related hospital admission in the past year and 33% used long-term oxygen therapy. These caregivers are most often close family members, like spouses or cohabitants that live together with the patient [11]. Informal caregivers provide practical help with activities like household chores, gardening and shopping [11]. Other important tasks are accompanying patients to healthcare providers, help with personal care, providing emotional support, and the management of medication use and healthcare appointments [11, 12].

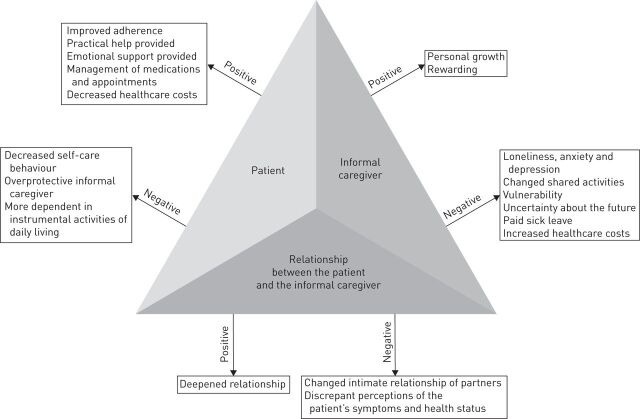

Patients who have an informal caregiver are less likely to smoke [13], have a better exercise capacity and report less frequent emergency department visits than COPD patients who are living alone [14]. An informal caregiver may improve patient adherence. For example, a positive association was found between having an informal caregiver and better adherence to antihypertensive and long-acting β-agonist medications in COPD patients [13]. Informal caregiving may also have negative consequences. Patients' self-care behaviour may decrease with higher levels of caring behaviour from informal caregivers [15]. Informal caregivers can be overprotective [16], and COPD patients living together with an informal caregiver may be more dependent in instrumental activities of daily living [14].

COPD is associated with significant economic burden [1]. Maintenance medication and hospitalisations due to a COPD exacerbation are responsible for the majority of the costs due to COPD [17]. So, a decrease in hospitalisations can save healthcare costs. Informal caregivers may improve patient adherence [13] and they provide (informal) care at home [10]. Therefore, informal caregiving reduces costs for professional care at home. However, informal caregiving can also have negative consequences. For example, informal caregiving may lead to higher costs for paid sick leave of the informal caregiver [11], or anxiety or worrying that is associated with higher rates of contacts with healthcare professionals and higher use of medication [18]. Moreover, a perceived imbalance in delegated dyadic coping can decrease a couple's quality of life [19], which may increase the use of healthcare resources [20]. These findings show the complex role of informal caregivers and the need for healthcare providers to gain insight into how informal caregivers fulfil their role (fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

The complex process of informal caregiving.

Impact on informal caregivers

Caregivers of patients with COPD are mostly female spouses [11]. This could be due to the smoking trends some decades ago. However, the historical perception that COPD is a predominantly disease of males is changing, because of changing smoking trends during the past 50 years [21]. In addition, a study in community-dwelling dependent elderly concluded that women had a higher rate of living alone and a lower rate of receiving care by a spouse [22]. Moreover, female caregivers are more likely to take responsibility when a caregiving situation arises and caregiving is still considered as a woman's job [23]. About half of the caregivers are part of the work force. However, 34% of these informal caregivers took time off from work to help the patient [11].

Although informal caregivers have emphasised the need for increased support [24], formal support for caregivers is lacking [12]. Indeed, caregivers report a lack of information, and emotional and practical support [25, 26]. Informal caregivers have to rely upon extended family support [10], and they become an integral part of the care support system in the home [12]. This extended support mostly included adult children living in the home or nearby, who were caring alongside the spouse [12]. However, perceived extended support was negatively associated with the patient's disease severity [27]. Informal caregivers who perceive less support from family and friends are more likely to experience loneliness and depression [28]. The social environment encompasses more than social support, including perceived criticism. Therefore, the social environment is complex [29].

Patients often report that COPD affects their family life [30]. In this context, shared activities and familiar ways of being together as a couple could change [26] or completely disappear [31]. Moreover, informal caregivers experienced similar losses to the patients in terms of social life, shared experiences and the expected future [32]. Informal caregivers may experience anxiety, helplessness, depression, worries about the patient, uncertainty about the future, loss of mobility, and/or growing social isolation [11, 33] Caregiver vulnerability may occur when an imbalance exists between burden and coping capacity [31]. Informal caregivers' quality of life, in turn, has an impact on the COPD patient [34].

The relationship of the patient and caregiver may also be affected. For example, 16% of couples declared that smoking had a negative impact on their relationship and 42% stated that smoking had a negative impact on the family budget [30]. Furthermore, for some caregivers the coughing caused feelings of disgust, leading to difficulties in kissing their loved one [26]. This, together with the fact that sexual intercourse was considered too strenuous for the patient, changed the intimate relationship [26, 30, 35]. Although almost all caregivers felt that the patient needed their support [26], some caregivers persevered because of a sense of duty described in terms of marriage vows and societal expectations [31]. By contrast, for some couples the relationship deepened [26]. The quality of the relationship between caregivers and patients is an important predictor of caregiver burden [36]. In addition, other characteristics of the relationship, like a history of relational stress, conflict and instability increase the risk of caregiver vulnerability [31].

Caregivers, as well as patients, may experience a decline in psychological and physical functioning, towards the terminal stages [37]. In fact, caregivers of patients with advanced COPD had more symptoms of anxiety and depression, and their self-rated health was significantly worse when compared with caregivers of patients with early COPD [38].

Caregiver burden is also related to the occurrence of COPD exacerbations [39], especially when accompanied by a hospital admission. A study including patients with COPD and their relatives after an intensive care unit (ICU) stay showed that 72% of the caregivers had symptoms of anxiety and 26% had symptoms of depression at the point of discharge from the ICU [40]. After 90 days, 32% of the caregivers received medication for anxiety or depression prescribed after the patient's ICU stay [40]. In a general population, symptoms of depression were more prevalent in caregivers of nonsurvivors [41], indicating that the burden is higher in caregivers of deceased patients. In caregivers of patients with COPD, the perceived possibility of patients having a painful death associated with asphyxia was the main cause of emotional distress [39]. For bereaved caregivers, death is often unexpected and unanticipated [42]. Bereaved caregivers experienced caregiver burden and a need for bereavement support [43]. Advance care planning is a process whereby a patient, in consultation with healthcare providers, family members and other loved ones, make decisions about their future healthcare [44]. Family members of elderly patients who received facilitated advance care planning had fewer symptoms of post-traumatic stress, depression and anxiety compared with family members of patients receiving usual care [45]. However, advance care planning, in which communication about end-of-life care is an essential part, occurs infrequently in patients with COPD [46].

Caregivers may not only experience distress, but also positive caregiving appraisals [6]. Caring for a patient with COPD was considered as an opportunity for personal growth [39]. Moreover, being able to care for a loved one and help the patient stay at home as long as possible may be rewarding [24]. Considering the above, adequate communication between the patient and the informal caregiver are a prerequisite, and therefore, may be a target for interventions.

Informal caregiver's perceptions of the patient's health

Patients and informal caregivers may have discrepant perceptions of the patients' symptoms and health status [47, 48]. This can result in distress for patients, which, in turn, has a negative influence on the informal caregivers' quality of life [16].

Informal caregivers witness the gradual deterioration in health and increasing symptoms over the years, and are concerned about the patient's struggle with these consequences of COPD. However, informal caregivers also reported that they felt that the patient had tried to “get on with their life with COPD” [10]. Pinnock et al. [42] concluded that patients as well as their informal carers accepted the debilitating symptoms of a lifelong condition. However, uncertainty about the trajectory of the disease caused stress to the patient and the informal caregiver [10].

Subjective burden is the person's appraisal of the caregiving situation. This subjective burden is considered as an important predictor of informal caregivers' psychological health, like symptoms of anxiety and depression [49]. Researchers concluded in a study about perceived breathlessness, that spouses who perceived breathlessness of the patient as more severe were more likely to experience a higher level of psychological distress [50]. Moreover, there may be an important discrepancy between the patient's and the informal caregiver's experience of the patients' symptoms. For example, informal caregivers reported a higher number of symptoms than patients. The severity of symptoms like fatigue, coughing and anxiety were rated higher by informal caregivers than by the patients [47]. In addition, disagreement was also shown between the physician and patient in the perception of symptoms. Only a low concordance was found between the patient with COPD and the physician in the impact of the symptoms on the patient's life. When the disease became more severe, this concordance increased [51]. Patients and informal caregivers may also disagree in how satisfied they are with the medical treatment. However, results about the direction of the disagreement are conflicting [47, 52]. Therefore, more knowledge is needed about the informal caregiver's perception of the patient's health status.

Future perspectives

To date, the importance of informal caregiving seems underrated in the English-language literature [1], and many clinically relevant questions remain unanswered. Living with a patient with COPD can be demanding and may cause health problems in informal caregivers [34]. To date, it remains unknown whether and to what extent informal caregivers of patients with COPD have adapted the family system to the limitations and needs of their chronically ill loved one. Pilot data (n=4 couples) suggest that a common sense of companionship between partners assists with reshaping their relationship and adapting it to the new life rhythm required by living with COPD [53].

The possible influence of informal caregivers' lifestyle on (non-)adherence to medical regimens and the healthy lifestyle of the patient with COPD, like regular daily physical activity, smoking cessation and healthy nutrition also warrants further studies. For example, indoor smoking by the resident loved one negatively influences air quality, which is associated with worse health status of the patient with COPD [54]. Finally, informal caregivers, like spouses and adult children, are uniquely positioned to witness the limitations that COPD patients experience during activities of daily life. This will provide healthcare providers with new insights, and may result in new, personalised interventions.

Here, we have reviewed the current knowledge about informal caregivers of patients with COPD. Several questions remain, which need to be addressed by further studies. These studies should include the role and lifestyle of informal caregivers, the impact of caregiving on the informal caregivers, including the impact during and after acute events like COPD-related hospital admissions, and the perceptions of the informal caregivers of the patients' health status (table 1) [55].

TABLE 1.

Research needs

| To study the relationship between the COPD patient's home environment and the informal caregiving process |

| To study the influence of informal caregiving on the use of healthcare resources by patients with COPD |

| To study the influence of the lifestyle of informal caregivers on the patient's adherence to medical regimens |

| To study the relationship between lifestyle factors in patients with COPD and their resident loved ones |

| To investigate informal caregivers’ burden |

| To investigate informal caregivers’ knowledge about COPD |

| To investigate whether and to what extent informal caregivers’ burden, health and mood status are influenced by exacerbation-related hospital admissions |

| To study the impact of communication between COPD patients and their informal caregivers on general well-being |

| To investigate the extent to which informal caregivers of patients with COPD have adapted the family system to the limitations and needs of their chronically ill loved ones |

| To investigate the differences between COPD patients’ and informal caregivers’ perceptions of patients’ health status |

| To prospectively study the effects of a COPD exacerbation on informal caregivers’ perceptions of the patients’ health status |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

COPD does not only affect patients' lives, but also the lives of their informal caregivers. Therefore, the complete patient system, including informal caregivers, should receive treatment and care. This should be done within primary care services (general practitioners), secondary care services (hospitals) and tertiary care services (rehabilitation centres). For example, education should also be available for the patients' informal caregivers. Indeed, informal caregivers desire information about the expected course of the disease, physical and psychological care, information about medical aids and other resources, and how to deal with an emergency [56]. Moreover, carers found their own needs for information as important as that of the patient [57]. Attention should also be paid to the emotional and practical needs of the informal caregivers [6]. Including family members in a multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation programme benefits the family by improving coping strategies and the psychosocial adjustment to illness [58]. General practitioners and chest physicians should facilitate informal caregivers joining the patient's doctor appointment, so that knowledge can be exchanged.

Professional home care can include several aspects such as home visits, telephone calls, education, and support in acquiring and applying self-management skills [59]. Home visits by a nurse, combined with the availability of a nurse specialist by phone, have been shown to reduce symptoms of depression in patients with COPD [60]. Patients and their informal caregivers need care that is coordinated within and between care settings, by a person who shows empathy and cooperation [61].

Conclusion

To conclude, patients with COPD and their informal caregivers are confronted daily with multiple limitations due to COPD. Therefore, COPD management should not only focus on the optimal drug therapy, but also on its home management throughout the whole disease trajectory. Informal caregivers play an important role, but the process of informal caregiving is complex. Therefore, exploring the interaction between patients and informal caregivers and paying attention to the needs of informal caregivers should be part of research [55], and in turn, of regular clinical care for patients with COPD. This could improve the quality of life of both patients and their informal caregivers and save healthcare costs [20]. A more in-depth insight in the role of the home environment is needed to optimise home management programmes.

Footnotes

Support statement: N. Nakken is financially supported by Lung Foundation Netherlands, Leusden, the Netherlands (grant 3.4.12.024), and by a research grant from Boehringer-Ingelheim, the Netherlands. No funding source had any role in the writing of this manuscript or in the decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agusti AG, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 187: 347–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 2006; 3: e442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Annegarn J, Meijer K, Passos VL, et al. Problematic activities of daily life are weakly associated with clinical characteristics in COPD. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012; 13: 284–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waschki B, Spruit MA, Watz H, et al. Physical activity monitoring in COPD: compliance and associations with clinical characteristics in a multicenter study. Respir Med 2012; 106: 522–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim YJ, Lee BK, Jung CY, et al. Patient's perception of symptoms related to morning activity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the SYMBOL study. Korean J Intern Med 2012; 27: 426–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janssen DJ, Spruit MA, Wouters EF, et al. Family caregiving in advanced chronic organ failure. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012; 13: 394–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janssen DJ, Schols JM, Wouters EF, et al. One-year stability of care dependency in patients with advanced chronic organ failure. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014; 15: 127–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macdonald MT, Lang A, Storch J, et al. Examining markers of safety in homecare using the international classification for patient safety. BMC Health Serv Res 2013; 13: 191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of COPD. www.goldcopd.org/ Date last accessed: December 2014. Date last updated: January 2015.

- 10.Spence A, Hasson F, Waldron M, et al. Active carers: living with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Palliat Nurs 2008; 14: 368–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gautun H, Werner A, Luras H. Care challenges for informal caregivers of chronically ill lung patients: results from a questionnaire survey. Scand J Public Health 2012; 40: 18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hynes G, Stokes A, McCarron M. Informal care-giving in advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: lay knowledge and experience. J Clin Nurs 2012; 21: 1068–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trivedi RB, Bryson CL, Udris E, et al. The influence of informal caregivers on adherence in COPD patients. Ann Behav Med 2012; 44: 66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wakabayashi R, Motegi T, Yamada K, et al. Presence of in-home caregiver and health outcomes of older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011; 59: 44–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang KY, Sung PY, Yang ST, et al. Influence of family caregiver caring behavior on COPD patients’ self-care behavior in Taiwan. Respir Care 2012; 57: 263–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Snippe E, Maters GA, Wempe JB, et al. Discrepancies between patients’ and partners’ perceptions of unsupportive behavior in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Fam Psychol 2012; 26: 464–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maleki-Yazdi MR, Kelly SM, Lam SY, et al. The burden of illness in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Canada. Can Respir J 2012; 19: 319–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Løkke A, Hilberg O, Kjellberg J, et al. Economic and health consequences of COPD patients and their spouses in Denmark – 1998–2010. COPD 2014; 11: 237–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meier C, Bodenmann G, Mörgeli H, et al. Dyadic coping, quality of life, and psychological distress among chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients and their partners. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2011; 6: 583–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.García-Polo C, Alcázar-Navarrete B, Ruiz-Iturriaga LA, et al. Factors associated with high healthcare resource utilisation among COPD patients. Respir Med 2012; 106: 1734–1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aryal S, Diaz-Guzman E, Mannino DM. COPD and gender differences: an update. Transl Res 2013; 162: 208–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuzuya M, Hasegawa J, Enoki H, et al. [Gender difference characteristics in the sociodemographic background of care recipients]. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi 2010; 47: 461–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.del Río-Lozano M, García-Calvente Mdel M, Marcos-Marcos J, et al. Gender identity in informal care: impact on health in Spanish caregivers. Qual Health Res 2013; 23: 1506–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bergs D. “The Hidden Client” – women caring for husbands with COPD: their experience of quality of life. J Clin Nurs 2002; 11: 613–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Currow DC, Ward A, Clark K, et al. Caregivers for people with end-stage lung disease: characteristics and unmet needs in the whole population. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2008; 3: 753–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindqvist G, Albin B, Heikkilä K, et al. Conceptions of daily life in women living with a man suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2013; 14: 40–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nordtug B, Krokstad S, Sletvold O, et al. Differences in social support of caregivers living with partners suffering from COPD or dementia. Int J Older People Nurs 2013; 8: 93–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kara M, Mirici A. Loneliness, depression, and social support of Turkish patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and their spouses. J Nurs Scholarsh 2004; 36: 331–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoth KF, Wamboldt FS, Ford DW, et al. The social environment and illness uncertainty in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Behav Med 2015; 22: 223–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kupryś-Lipińska I, Kuna P. Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) on patient's life and his family. Pneumonol Alergol Pol 2014; 82: 82–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simpson AC, Young J, Donahue M, et al. A day at a time: caregiving on the edge in advanced COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2010; 5: 141–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seamark DA, Blake SD, Seamark CJ, et al. Living with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): perceptions of patients and their carers. An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Palliat Med 2004; 18: 619–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giacomini M, DeJean D, Simeonov D, et al. Experiences of living and dying with COPD: a systematic review and synthesis of the qualitative empirical literature. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser 2012; 12: 1–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kühl K, Schurmann W, Rief W. Mental disorders and quality of life in COPD patients and their spouses. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2008; 3: 727–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ibañez M, Aguilar JJ, Maderal MA, et al. Sexuality in chronic respiratory failure: coincidences and divergences between patient and primary caregiver. Respir Med 2001; 95: 975–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pinto RA, Holanda MA, Medeiros MM, et al. Assessment of the burden of caregiving for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med 2007; 101: 2402–2408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simpson AC, Rocker GM. Advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: impact on informal caregivers. J Palliat Care 2008; 24: 49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Figueiredo D, Gabriel R, Jácome C, et al. Caring for relatives with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: how does the disease severity impact on family carers? Aging Ment Health 2014; 18: 385–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gabriel R, Figueiredo D, Jácome C, et al. Day-to-day living with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: towards a family-based approach to the illness impacts. Psychol Health 2014; 29: 967–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Miranda S, Pochard F, Chaize M, et al. Postintensive care unit psychological burden in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and informal caregivers: a multicenter study. Crit Care Med 2011; 39: 112–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kentish-Barnes N, Lemiale V, Chaize M, et al. Assessing burden in families of critical care patients. Crit Care Med 2009; 37: Suppl., S448–S456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pinnock H, Kendall M, Murray SA, et al. Living and dying with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: multi-perspective longitudinal qualitative study. BMJ 2011; 342: d142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hasson F, Spence A, Waldron M, et al. Experiences and needs of bereaved carers during palliative and end-of-life care for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Palliat Care 2009; 25: 157–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singer PA, Robertson G, Roy DJ. Bioethics for clinicians: 6. Advance care planning. CMAJ 1996; 155: 1689–1692. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, et al. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010; 340: c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Janssen DJ, Engelberg RA, Wouters EF, et al. Advance care planning for patients with COPD: past, present and future. Patient Educ Couns 2012; 86: 19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Janssen DJ, Spruit MA, Wouters EF, et al. Symptom distress in advanced chronic organ failure: disagreement among patients and family caregivers. J Palliat Med 2012; 15: 447–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Low G, Gutman G. Couples’ ratings of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients’ quality of life. Clin Nurs Res 2003; 12: 28–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jácome C, Figueiredo D, Gabriel R, et al. Predicting anxiety and depression among family carers of people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int Psychogeriatr 2014: 1191–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Al-Gamal E, Yorke J. Perceived breathlessness and psychological distress among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and their spouses. Nurs Health Sci 2014; 16: 103–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miravitlles M, Ferrer J, Baró E, et al. Differences between physician and patient in the perception of symptoms and their severity in COPD. Respir Med 2013; 107: 1977–1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Giovannetti ER, Reider L, Wolff JL, et al. Do older patients and their family caregivers agree about the quality of chronic illness care? Int J Qual Health Care 2013; 25: 515–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ek K, Ternestedt BM, Andershed B, et al. Shifting life rhythms: couples’ stories about living together when one spouse has advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Palliat Care 2011; 27: 189–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Osman LM, Douglas JG, Garden C, et al. Indoor air quality in homes of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 176: 465–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nakken N, Janssen DJ, van den Bogaart EH, et al. An observational, longitudinal study on the home environment of people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the research protocol of the Home Sweet Home study. BMJ Open 2014; 4: e006098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parker SM, Clayton JM, Hancock K, et al. A systematic review of prognostic/end-of-life communication with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness: patient/caregiver preferences for the content, style, and timing of information. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007; 34: 81–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Philip J, Gold M, Brand C, et al. Facilitating change and adaptation: the experiences of current and bereaved carers of patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Palliat Med 2014; 17: 421–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marques A, Jácome C, Cruz J, et al. Family-based psychosocial support and education as part of pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD: a randomized controlled trial. Chest 2015; 147: 662–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barnett M. A nurse-led community scheme for managing patients with COPD. Prof Nurse 2003; 19: 93–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Neff DF, Madigan E, Narsavage G. APN-directed transitional home care model: achieving positive outcomes for patients with COPD. Home Healthc Nurse 2003; 21: 543–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wodskou PM, Høst D, Godtfredsen NS, et al. A qualitative study of integrated care from the perspectives of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and their relatives. BMC Health Serv Res 2014; 14: 471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]