To the Editors:

Lung transplantation is an established therapy for a variety of end-stage lung diseases. Successful transplantation improves prognosis and quality of life in most recipients. In the current setting where lung donors are scarce, single-lung transplantation allows for more extensive utilisation of the limited donor organ pool [1]. Although forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) recovery is lower and the risk of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome is higher, single lung transplant recipients still have comparable exercise tolerance and quality-of-life scores when compared to bilateral lung transplant recipients [2].

Fortunately, vascular anastomotic stenoses are an uncommon event following lung transplantation. There are two types of vascular complications: either pulmonary arterial stenosis or pulmonary venous stenosis. The structures affected determine the clinical manifestations: arterial obstruction leads to pulmonary ischaemia and infarction, and venous obstruction leads to pulmonary oedema. The diagnosis should be considered in the presence of unexplained exertional hypoxaemia and persistent pulmonary hypertension. The diagnosis can be confirmed with computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) and pulmonary angiography. As the complication is rare there are no clear treatment algorithms. In the very early phase (1 week), surgical treatment of the stenosis is the preferred option but may still carry a poor prognosis. However, later the options are broader and include percutaneous intervention. We report a case of stenosis of the left main pulmonary artery following single lung transplantation, which was successfully treated by percutaneous transluminal balloon angioplasty and stent placement.

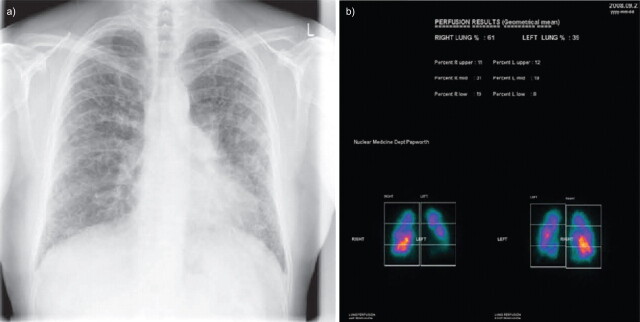

A 63-yr-old male with history of usual interstitial pneumonitis underwent a single left lung transplant in July 2009 (fig. 1). He also had a previous history of hepatitis B exposure. He had an uncomplicated. post-operative course. Standard immunosuppresion was initiated with cyclosporine, mycophenolate and prednisolone. Fibre-optic bronchoscopy (FOB) performed at 3 weeks showed aspergillus and transbronchial biopsy revealed A1 rejection. He was treated with oral and inhaled anti-fungals and increased doses of oral prednisolone (30 mg). He was discharged from hospital at 3 weeks post-transplant feeling well.

Figure 1.

Pre-transplant a) chest radiograph and b) perfusion scan.

3 months post transplant, he presented with gradual onset of increasing breathlessness and worsening exercise tolerance. Spirometry revealed an FEV1 of 2.49 L and a forced vital capacity (FVC) of 3.29 L. A repeat FOB showed no evidence of infection or rejection. Plasma cytomegalovirus (CMV) PCR was elevated (1.6×106 CMV copies·mL−1) and treated with intravenous gancyclovir. 3 weeks of intravenous treatment reduced the CMV PCR to <300 copies·mL−1 without any significant improvement in clinical symptoms. A CTPA revealed the presence of small pulmonary emboli (PE) in the left main pulmonary artery with infarction and minor change in the pulmonary artery calibre. A therapeutic INR was achieved and maintained through regular monitoring.

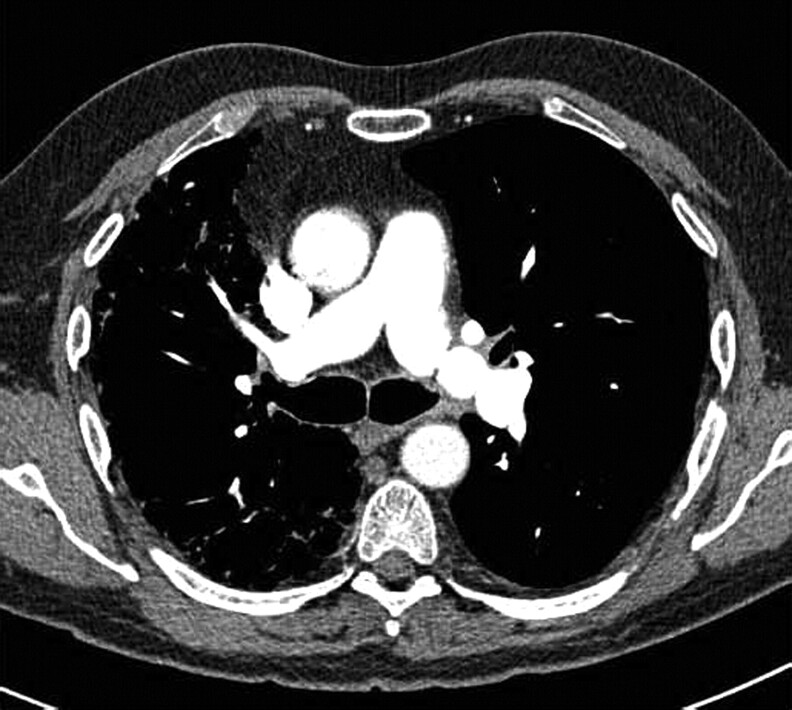

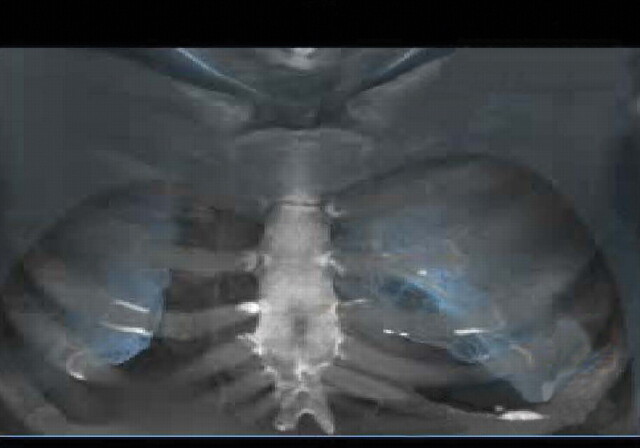

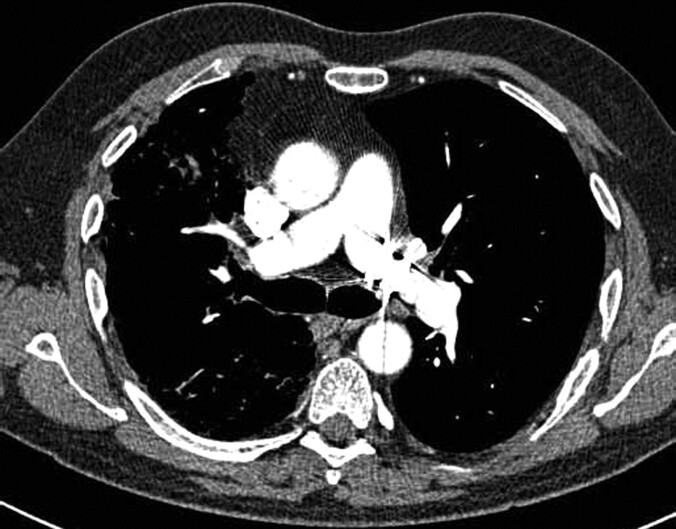

Despite these therapeutic measures the patient continued to complain of decreased exercise tolerance without spirometric change. 6 months post-transplant, the patient's breathlessness suddenly worsened and his exercise tolerance was limited to pre-transplant levels. Although his resting oxygen saturation was 95%, post-exercise it dropped to 67%. A further CTPA revealed no PE but severe stricturing of the pulmonary artery at the anastomtic site (fig. 2) with reduced perfusion to the transplanted lung (fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Computed tomography pulmonary angiogram showing pulmonary artery stricture.

Figure 3.

Post-transplant computed tomography pulmonary angiogram showing reduced perfusion to transplanted lung.

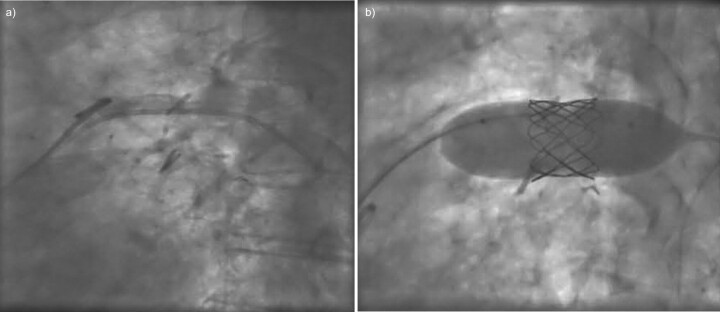

A pulmonary arteriogram revealed a concentric narrowing in the left main pulmonary artery. The pressure gradient across the lesion was 10–12 mmHg. The pulmonary artery was initially balloon dilated and an 8×20 mm Cheatham platinum stent was inserted (fig. 4). Post-stent placement the pressure gradient fell to 4 mmHg, with instant relief of symptoms.

Figure 4.

Cheatham platinum stent placing a) pre and b) post angiogram.

2 weeks following stent insertion a repeat CTPA revealed resolution of the narrowing on the left main pulmonary artery (fig. 5). His 6-min walk distance improved to 500 m, with little change in saturation from 96 to 91% during the test. His spirometry has remained unchanged with an FEV1 of 2.64 L and an FVC of 3.96 L. The patient continues to remain well 18 months post-lung transplantation.

Figure 5.

Post-stent correction of pulmonary artery stricture.

Single lung transplantation is an effective treatment for end-stage pulmonary fibrosis. Dyspnoea and hypoxaemia in post-transplant patients are usually related to rejection or infection. Pulmonary artery anastomotic stenosis is a rare but serious complication defined as an anastomotic diameter of <75% of that of the neighbouring vessels [3]. Other potential complications include kinking of the donor pulmonary artery distal to the anastomosis secondary to torsion [4]. The time of presentation varies from immediate post-operative period to a few years. The clinical features in the immediate post-operative period include refractory respiratory failure and persistent pulmonary hypertension. Delayed features include worsening dyspnoea and exercise tolerance [5]. Most cases present within the first 6 weeks post transplantation. In our case, the patient presented with symptoms early in the post-operative period. However, the CMV infection followed by the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism complicated the picture and delayed the diagnosis.

No single test is definitive and a variety of investigative diagnostic options are available. Trans-oesophageal echocardiogram provides important information regarding the size and patency of the proximal left pulmonary artery. Multi-detector CTPA with multi-planar reconstruction has improved the sensitivity and specificity of identifying vascular abnormalities in both the venous and arterial system. However, pulmonary angiogram remains the gold standard for examination of the pulmonary arterial tree [6].

Over time, the decrease in the native lung size and increase in the transplanted lung size can result in changes in the anatomical position of the anastomosis which may result in the anastomotic kinking or twisting producing a similar syndrome. This is unlikely to be the case in our patient as the stricture was at the anastomotic site and most probably represents a technical complication.

Although the long-term prognosis in our patient remains uncertain, the percutaneous insertion of a stent restored perfusion to the transplanted lung and avoided the risk of further surgery. However, vascular stents are associated with some complications including self limiting haemorrhage, stent migration, neo-intimal in growth and embolisation [6].

In contrast to the high risks posed by open surgery, endovascular techniques are simple and well tolerated and offer an additional treatment option for this rare complication [7, 8].

Footnotes

Provenance

Submitted article, peer reviewed.

Statement of Interest

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grossman RF, Frost A, Zamel N, et al. Results of single-lung transplantation for bilateral pulmonary fibrosis. The Toronto Lung Transplant Group. N Engl J Med 1990; 322: 727–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christie JD, Edwards LB, Aurora P, et al. Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: twenty-fifth official adult lung and heart/lung transplantation report 2008. J Heart Lung Transplant 2008; 27: 957–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferreti G, Boutelant M, Thony F, et al. Successful stenting of a pulmonary arterial stenosis after a single lung transplant. Thorax 1995; 50: 1011–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shoji T, Hanaoka N, Wada H, et al. Balloon angioplasty for pulmonary artery stenosis after lung transplantation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008; 34: 693–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waurick PE, Kleber FX, Ewert R, et al. Pulmonary artery stenosis 5 years after single lung transplantation in primary pulmonary hypertension. J Heart Lung Transplant 1999; 18: 1243–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doyle T, Loyd J, Robbins IM. Percutaneous pulmonary artery and vein stenting. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 164: 657–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaubert J, Moulin G, Thomas P, et al. Anastomotic stenosis of the left pulmonary artery after lung transplantation: treatment by percutaneous placement of an endoprosthesis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1993; 161: 947–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berger H, Steiner W, Schmidt D, et al. Stent-angioplasty of an anastomotic stenosis of the pulmonary artery after lung transplantation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1994; 8: 103–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]