Abstract

Neonicotinoid insecticides (NNIs) have been intensively used and exploited, resulting in their presence and accumulation in multiple environmental media. We herein investigated the current levels of eight major NNIs in the Harbin section of the Songhua River in northeast China, providing the first systematic report on NNIs in this region. At least four NNIs in water and three in sediment were detected, with total concentrations ranging from 30.8 to 135 ng L-1 and from 0.61 to 14.7 ng g-1 dw, respectively. Larger spatial variations in surface water NNIs concentrations were observed in tributary than mainstream (p < 0.05) due to the intensive human activities (e.g., horticulture, urban landscaping, and household pet flea control) and the discharge of wastewater from many treatment plants. There was a significant positive correlation (p < 0.05) between the concentrations of residual imidacloprid (IMI), clothianidin (CLO), and Σ4NNIs in the sediment and total organic carbon (TOC). Due to its high solubility and low octanol-water partition coefficient (Kow), the sediment-water exchange behavior shows that NNIs in sediments can re-enter into the water body. Human exposure risk was assessed using the relative potency factor (RPF), which showed that infants have the highest exposure risk (estimated daily intake (ΣIMIeq EDI): 31.9 ng kg-1 bw·d-1). The concentration thresholds of NNIs for aquatic organisms in the Harbin section of the Songhua River were determined using the species sensitivity distribution (SSD) approach, resulting in a value of 355 ng L-1 for acute hazardous concentration for 5% of species (HC5) and 165 ng L-1 for chronic HC5. Aquatic organisms at low trophic levels were more vulnerable to potential harm from NNIs.

Keywords: Neonicotinoid insecticides, Sediment-water exchange, Human exposure, Species sensitivity distribution

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Eight typical NNIs in the Harbin section of the Songhua River were investigated.

-

•

Higher NNIs levels were found in tributaries than mainstream of Songhua River.

-

•

IMI and THM were among the top NNIs observed in water and sediment.

-

•

Potential risks of NNIs to aquatic organisms and humans were assessed.

1. Introduction

Neonicotinoid insecticides (NNIs) have been widely applied to pest control and have become one of the most prevalent insecticides worldwide [1,2]. NNIs selectively act on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) in the postsynaptic membrane of the insect nervous system and its peripheral nerves to obstruct central nerve conduction, resulting in excitement, paralysis, and ultimately death of pests [1,3]. Although NNIs applications are for controlling insects in agricultural plants, both parent and metabolites of NNIs have been confirmed to damage non-target species [[4], [5], [6]], causing significant ecological imbalance. For example, adverse effects from NNIs have been confirmed on bees [4,7,8], insectivorous birds [9,10], aquatic organisms [11,12], earthworms [13], and humans [3,14]. The adverse ecological risks associated with the extensive use of NNIs have caused policy makers' attention besides the research community. For example, the European Commission [[15], [16], [17]], France [18,19], and Canada [[20], [21], [22]] have already restricted the use of imidacloprid (IMI), thiamethoxam (THM), and clothianidin (CLO). Meanwhile, France also prohibited the application of acetamiprid (ACE) and thiacloprid (THA), and the U.S. has restricted the registration of a portion of NNIs products to protect pollinators [[23], [24], [25]].

NNIs have been rapidly developed and widely used due to their high efficiency, broad-spectrum, strong selectivity, and lack of cross-resistance with other traditional insecticides [26,27]. In 2017, over 2600 NNIs products were registered in China, with the amount of IMI accounting for approximately half of the total products, followed by ACE (26.1%) and THM (14.6%) [28]. The usage of NNI commodities in China has been rising from 2013 to 2018, and exceeding 30,000 tons annually since 2016 (unpublished data), with IMI, ACE, and THM in the top three uses. Owing to the characteristics of high water solubility and low volatility [[29], [30], [31]], NNIs can pollute water systems from the soil through runoff [29]. For example, Chen et al. [30] measured NNIs in river/lake water along the Yangtze River Basin and reported total concentrations of 13.0–3240 ng L-1. Mahai et al. [2] determined six NNIs in the central Yangtze River and found that ACE (100%), IMI (100%), and THM (95%) had the highest detection frequency. Zhang et al. and Yi et al. [31,32] studied the occurrence and distribution of five NNIs in the Pearl River, and at least one NNI was detected in surface water. Apart from surface water, several studies have shown the existence of NNIs in other environmental media, including sediments [29,33], soil [29,34], particulate matter [35,36], dust [37,38]. Meanwhile, scholars have confirmed that NNIs are also systemically distributed in biological media such as urine [39,40], hair [41], teeth [42], fruits [43], and vegetables [43,44]. NNIs pollution has become a major global environmental concern. Recent reports on NNIs water pollution were mostly from developed countries [2]. To date, studies on NNIs in surface water and sediments in China are mainly focused on the central and south of China, despite the fact that it is a major agricultural country with great production and consumption of NNIs.

The Songhua River basin in northeast China has a dense population and well-developed agriculture and aquaculture. The Songhua River, one of the seven major water systems in China, is an important backup resource supplying drinking water to the city of Harbin [45,46]. With rapidly developed agriculture and urbanization, a large volume of agricultural and household wastewater has been released into the Songhua River, resulting in worsening water quality and posing risks to human health [47]. Existing studies on Songhua River pollution mostly focused on heavy metals [45,46,48,49], polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [[50], [51], [52]], polychlorinated biphenyls [[53], [54], [55]], antibiotics [56,57], etc., but no systematic investigation on NNIs pollution has been made. NNIs as emerging contaminants currently relevant data/parameters on their fate, environmental behavior, and ecotoxicological effects are usually scarce and poorly understood. The present study aims to fill this knowledge gap by investigating the occurrence of eight common NNIs in surface water and sediments and associated spatial distributions in the Harbin section of the Songhua River, estimating the sediment-water exchange behavior of NNIs using fugacity fractions, and assessing the potential exposure risks of the human and aquatic ecosystem. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic report to document the occurrence and risk assessment of NNIs in the Songhua River, and the results of the current study will offer useful data and knowledge for regional pesticides management.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study area and sample collection

The Harbin section of the Songhua River (125°42′ ∼ 130°10′ E, 44°04′ ∼ 46°40′ N) flows through the city from southwest to northeast direction [58], covering approximately 66 km. The study region has a temperate continental monsoon climate with significant and uneven seasonal changes in precipitation and runoff distribution, and the annual runoff is mostly localized from July to September (http://www.harbin.gov.cn/).

Between September and November of 2019, 13 water samples and 11 sediment samples were collected in the Harbin section of the Songhua River (Fig. 1). The sampling sites included four locations tributary of Songhua River (T1 to T4), one location upstream of the city (M1), six locations center of the city (M2 to M7), two locations downstream of the city (M8 and M9). The sampling sites were selected to represent areas with different economic developments and human activities, including rural, commercial, residential, and scenic areas. Details can be found in the supporting information (SI, Table S1). At each sampling site, at least 1 L of surface water was collected in brown glass bottles using a portable water collector, and all water samples were sent to the laboratory immediately and placed in a 4 °C refrigerator. Sediment samples were obtained at a depth of 0–10 cm with a stainless steel grab, and the overall weight of the sediment samples was not less than 500 g. The samples were quickly wrapped in polyethylene bags, shipped to the laboratory, and placed in a refrigerator at −20 °C. Sediment samples were not collected at sampling sites M4 and M6 due to the influence of the berm nearby. In addition, previous studies have shown that temperature has little effect on the concentration of NNIs [31], so the difference between the two sampling temperatures is ignored in the current study.

Fig. 1.

Sampling sites in the Harbin section of the Songhua River. Nine sampling sites (M1-M9) are located in the mainstream and four (T1-T4) in the tributaries.

2.2. Sample processing and chemical analysis

The target NNIs in water samples were extracted using the previously described method [2]. Briefly, water samples (1 L) were filtered through a Teflon filter and spiked with an internal standards mixture (50 μL of 1 mg L-1) before being processed using Waters Oasis HLB solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges (500 mg, 6 cc, Milford, MA, USA). The cartridge was preconditioned with 5 mL methanol and 5 mL ultra-pure water in sequence. After being loaded on the water samples, the target compounds were eluted with 5 mL ultra-pure water, followed by 5 mL methanol. The eluents were evaporated at 35 °C under a gentle nitrogen stream until nearly dry, then redissolved in 1 mL of 25% acetonitrile in water and passed through a 0.22 μm filter for analysis.

The sediment was pretreated using the dispersive solid-phase extraction procedure [59,60]. In detail, 5 g freeze-dried sample was transferred into a PTFE centrifuge tube, spiked with 50 μL mixed internal standard (1 mg L-1), and left to stand for 45 min. After adding 5 mL of ultrapure water and 10 mL of acetonitrile, the tube was shaken for 1 min and vortexed for 1 min. A 4 g MgSO4 and 1 g NaCl were added into the tube, followed by vortexing for 1 min. Then the tube was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min. A 6 mL supernatant was separated into a clean PTFE tube containing 200 mg primary secondary amine (PSA). The extract was vortexed for 2 min and centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min. An aliquot (5 mL) of the upper organic solution was evaporated to near dryness by a gentle nitrogen stream at 35 °C and reconstituted in 1 mL of 25% acetonitrile in water. The extract was filtrated through a 0.22 μm PTFE membrane for HPLC-MS/MS analysis.

The chemical analysis was carried out on AB SCIEX Triple Quad 5500 HPLC-MS/MS (Framingham, MA, USA) using an electrospray ionization source in the positive ion mode (ESI+) with multiple reactions monitoring (MRM) mode. The injection volume was 2 μL. The analytes were separated at 25 °C using a Phenomenex Kinetex® C18 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm). The mobile phase was 0.1% formic acid-water solution (A) and acetonitrile (B), and the flow rate of the mobile phase was set at 0.3 mL min-1. A gradient program of the mobile phase began with 95% A and 5% B, followed by a linear decrease from 95% to 65% A in 3 min, then to 45% A in 6 min, and finally reverted to 95% in 9 min before ending the program in 12 min (Fig. S1). In the MS/MS analysis, nitrogen was used as atomizing gas. The pressure of curtain and collision gas was set at 35 and 7 psi, respectively. Ion spray voltage was set at 5500 V. The temperature of drying gas was set at 550 °C. The pressure of ion source gas1 and gas2 was set at 55 and 60 psi, respectively. Collision cell exit potential and entrance potential were 16.0 and 10.0 V, respectively. The HPLC-MS/MS parameters for individual analytes are listed in Table S2.

Total organic carbon (TOC) contents of sediments were determined. After inorganic carbonate was removed with 1 mol L-1 hydrochloric acid, the TOC contents of the sediments were measured with the equipment of Elementar Vario TOC select (Hanau, Germany) [33].

2.3. Quality assurance and quality control

Procedural blank, laboratory blank, and matrix spiked samples were run in order before sample analysis. No target NNIs were detected in the blank samples. Meanwhile, three isotope-labeled compounds (clothianidin-d3, imidacloprid-d4, and thiamethoxam-d3) were applied to all samples before extraction and used as surrogate standards to check the efficiency of the sample preparation process [6]. Among them, imidacloprid-d4 is used as the internal standard for IMI, ACE, and THA; thiamethoxam-d3 is used as the internal standard for THM, nitenpyram (NTP), and dinotefuran (DIN); clothianidin-d3 is used as the internal standard for CLO and imidaclothiz (IMIT). The instrumental detection limits (IDL) were calculated from the lowest amount of eight target analytes based on three times the signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio [61], ranging from 0.002 to 0.02 ng mL-1. The method detection limit (MDL) of target analytes in the sample was calculated from the S/N ratio of 10 (Table S2) [2,38]. In this study, the recoveries of the eight target compounds ranged from 86.3% to 108.9% for water and from 79.8% to 106.5% for sediments (Table S2). If the detected concentration in the sample is lower than the MDL, the value is set to zero.

2.4. Sediment-water exchange

Sediment-water exchange behavior of NNIs is calculated using fugacity fractions (ff) (Eq. (1)), which plays an important process affecting water quality and the fate of NNIs [50,62]. The derivation of the relevant equations is shown in the SI file (Text S2).

| (1) |

where fs and fw are the fugacity (Pa) of the NNIs in sediments and water, respectively, Cs and Cw are the concentration of NNIs in sediment (ng·g-1 dw) and water (ng·L-1), respectively, foc is the organic carbon fraction in the sediment, and Kow is the dimensionless partition coefficient of octanol-water. When ff < 0.5, NNIs can diffuse from water into sediments, and in this situation, the sediment acts as a sink. In contrast, i.e., ff > 0.5, the sediment acts as a secondary source with NNIs releasing from the sediment to water.

2.5. Risk assessment

2.5.1. Estimation of human exposure

Health risk refers to the likelihood that a particular exposure or set of exposures will harm or may harm an individual's health [63]. To assess human's cumulative exposure to NNIs, the relative potency factor (RPF) method proposed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) was used to normalize the NNIs exposure effects [2,5,6,64]. IMI, mostly studied in literature and widely applied in agriculture, was selected as the index chemical. RPF of each target NNI was obtained by comparing its relative chronic reference dose (cRfD) (Table S3) to that of IMI (Eq. (2)). The cumulative exposure of the total NNIs in surface water was then calculated using Eq. (3).

| (2) |

| (3) |

where IMIeq is the cumulative exposure level of imidacloprid-equivalent total NNIs [2], and NNIi is the concentration of ith NNI in surface water (ng·L-1). Due to the similar structures between those of IMIT and CLO, these two species were assumed to have the same cRfD.

Conventional drinking water treatment was not efficient enough to remove NNIs [65]. We estimated the daily intake (EDI, ng·kg-1 bw·d-1) of each NNI in the Harbin section of the Songhua River (Eq. (4)).

| (4) |

where DIR represents daily water ingestion rate (L·kg-1 bw·d-1) (Table S4), and AR is the absorption rate by a human with a constant value of 100% [5].

2.5.2. Aquatic ecological risk assessment

Aquatic organisms can directly be affected by pesticides, mostly through runoff from farmlands [66]. The species sensitivity distribution (SSD) method was used to assess the risk of NNIs to aquatic organisms in the Songhua River. The SSD model can describe the variation in the sensitivity of different species to NNIs through probability distributions. Calculate proportions by first ranking selected toxicity data from lowest to highest, then converting ranks to proportions (Eq. (5)).

| (5) |

where i is the rank of selected species, and n is the total number of selected species. The toxicity data are plotted according to stressor intensity (X-axis) vs. proportion (Y-axis) of selected species, and the distribution is matched to generate the SSD curve.

Since the exposure effect to the total NNIs in each water sample was converted to that of IMIeq using the RPF method, we then selected IMI toxicity data as the evaluation index in the SSD model. Acute toxicity data (half effective concentration (EC50) and half lethal concentration (LC50) at 96 h of exposure) and chronic toxicity data (no observed effect concentration (NOEC) at least four days of exposure) for representative aquatic species in Chinese freshwater as well as standard test species were obtained from ECOTOX database (http://cfpub.epa.gov/ecotox/) of the U.S. EPA. Accordingly, we acquired 108 acute toxicity data for 38 aquatic species and 346 chronic toxicity data for 28 aquatic species in the present study (Table S5). The data was calculated using the SSD software provided by the U.S. EPA (SSD Generator V1, https://www.epa.gov/caddis-vol4). The environmental hazardous concentration (HCP) with cumulative probability at p% was calculated by the SSD model, and the p-value was normally chosen to be five [67], i.e., 95% of the species would not be threatened by NNIs at that concentration.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of data was carried out using SPSS (version 26.0) and Excel software (version 2016). Data were tested for normality by Shapiro-Wilk, and significance was tested using one-way ANOVA with p < 0.05. The relationship between NNIs and TOC in sediments was analyzed using Spearman correlation analysis.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Concentrations of NNIs in water and sediment

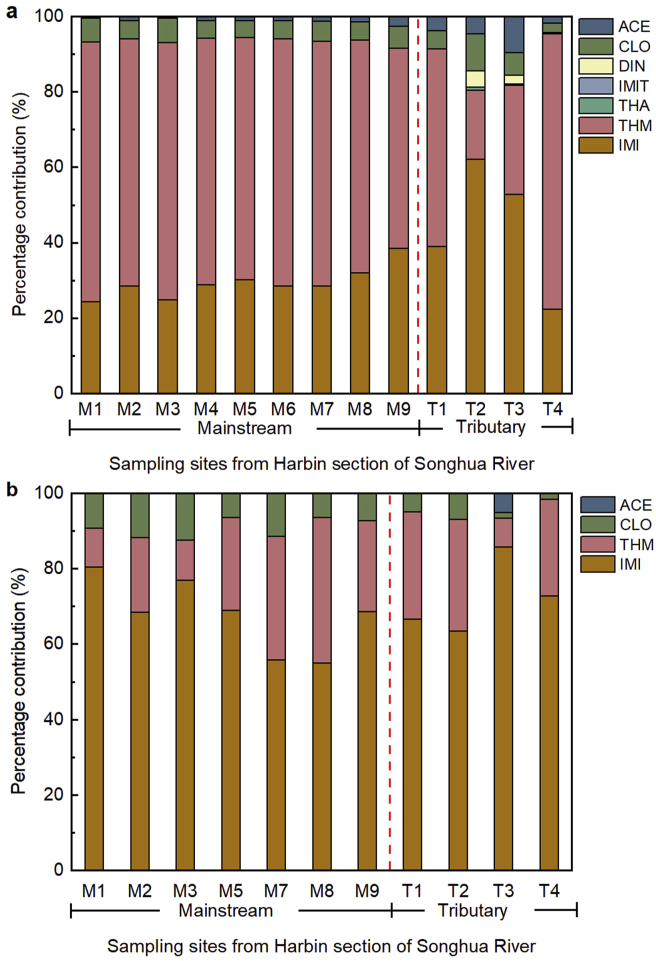

The residue status of the eight NNIs in the water bodies and sediments were determined in the Harbin section of the Songhua River, and the results are shown in Tables S6 and S7. Seven target compounds were detected in the water samples, namely IMI, THM, CLO, ACE, THA, DIN, and IMIT, while NTP was not detected in any water sample. As can be seen from Table 1, high detection frequencies (100%) of IMI, THM, CLO, and ACE in water were found, while the concentration of the seven NNIs (Σ7NNIs) in surface water ranged from 30.8 to 135 ng L-1, with a median of 41.4 ng L-1 and a mean of 62.3 ng L-1. In surface water, IMI and THM were the principal NNIs with their concentrations being in the range of 10.9–83.5 ng L-1 and 16.3–83.5 ng L-1, respectively. The sum of these two species accounted for more than 80% of Σ7NNIs in different water samples (Fig. 2a). THM had the highest mean concentration (30.7 ng L-1), followed by IMI (22.4 ng L-1), while IMIT has the lowest mean concentration (0.03 ng L-1) in surface water of the Harbin section of the Songhua River. It is noteworthy that the detected concentrations of IMI in all surface water samples were higher than the chronic threshold value of 10 ng L-1 that was set in the U.S [68].

Table 1.

Concentrations of NNIs in surface water (ng·L-1) and sediment (ng·g-1 dw) of the Harbin section of the Songhua River, China.

| IMI | THM | THA | IMIT | DIN | CLO | ACE | Σ7NNIs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface water (n = 13) | ||||||||

| DF | 100% | 100% | 15.4% | 15.4% | 23.1% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| GM | 16.9 | 28.4 | 0.69 | 0.03 | 1.69 | 2.75 | 0.85 | 52.3 |

| Median | 11.9 | 26.7 | ND | ND | ND | 2.11 | 0.51 | 41.4 |

| Mean | 22.4 | 30.7 | 0.80 | 0.03 | 2.89 | 3.42 | 1.94 | 62.3 |

| Range | 10.9–83.5 | 16.3–83.5 | ND-1.21 | ND-0.04 | ND-5.91 | 1.66–13.1 | 0.20–10.8 | 30.8–135 |

| Sediment (n = 11) | ||||||||

| DF | 100% | 100% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 100% | 9.09% | 100% |

| GM | 1.20 | 0.36 | ND | ND | ND | 0.11 | 0.75 | 1.76 |

| Median | 0.94 | 0.42 | ND | ND | ND | 0.11 | ND | 1.52 |

| Mean | 2.25 | 0.51 | ND | ND | ND | 0.12 | 0.75 | 3.63 |

| Range | 0.34–12.6 | 0.12–1.58 | ND | ND | ND | 0.07–0.22 | ND-0.75 | 0.61–14.7 |

DF: detection frequency; GM: geometric mean; ND: not detected; IMI: imidacloprid; THM: thiamethoxam; THA: thiacloprid; IMIT: imidaclothiz; DIN: dinotefuran; CLO: clothianidin; ACE: acetamiprid.

Fig. 2.

Composition of NNIs in surface water (a) and sediment (b) of the Harbin section of the Songhua River.

Compared to other rivers (Table S8), THM concentration in the Harbin section of the Songhua River was much higher than that in the central Yangtze River (4.29 ng L-1) [2] and Guangzhou urban waterways (10.9 ng L-1) [69], but lower than that in the Guangzhou section of the Pearl River (50.2 ng L-1) [31]. IMI concentration was higher than that in the central Yangtze River (6.11 ng L-1), but lower than Guangzhou urban waterways (81.1 ng L-1) and the Guangzhou section of the Pearl River (78.3 ng L-1). ACE concentration was similar to that of the central Yangtze River (2.70 ng L-1), but much lower than that in the Guangzhou urban waterways (51.2 ng L-1) and the Guangzhou section of the Pearl River (36.0 ng L-1). In China, more formulations containing IMI, THM, and ACE as active ingredients have been registered compared to the other NNIs [2]. The commodity, including IMI, ACE, and THM, is therefore likely to be used by planters (Table S9), resulting in higher detection frequencies and residual levels of these species compared with the other NNIs. The wide application of NNIs and wastewater disposal from wastewater treatment plants (WWTP) can be linked to the detected high concentrations of surface water NNIs in the Harbin section of the Songhua River. Heilongjiang Province is an important Commodity Grain Base in China [70]. Harbin has an arable land area of approximately 12.7% of Heilongjiang Province [71], and accordingly, the use of NNIs accounts for about 25% of the provincial. It was reported that fewer than 20% of NNIs active ingredients used in the agricultural sector can be absorbed by crops, while the remainder would enter into soil directly [5]. Subsequently, runoff can transport a portion of NNIs from soil into water bodies. The low vapor pressure and high log Koa (air partition coefficient) of NNIs lead to the rapid adsorption of sprayed NNIs onto atmospheric particulate matter, some of which can enter into surface water through atmospheric deposition [36,72]. In addition, NNIs in WWTP effluents should not be underestimated [31,73]. For instance, a study by Sadaria et al. [73] on 13 WWTPs in the U.S. found that the annual discharge of IMI in treated wastewater was about 1000–3400 kg. Besides, partial NNIs are widely used in horticulture, urban landscaping, household pest bait, and pet flea control [1,73].

A total of four NNIs were detected in the sediment, including IMI, THM, CLO, and ACE. The concentration of four NNIs (Σ4NNIs) detectable in the sediment ranged from 0.61 to 14.7 ng g-1 dw, with a mean of 3.63 ng g-1 dw. Considering the concentration contribution ratio, consistent with the water bodies, IMI and THM were the main contributors in the sediment (Fig. 2b) with a mean of 2.25 ng g-1 dw (range from 0.34 to 12.6 ng g-1 dw) and 0.51 ng g-1 dw (range from 0.12 to 1.58 ng g-1 dw), respectively. Among them, IMI, THM, and CLO had the highest detection rate (100%), while ACE was detected in only 9.09% of the sediments. It is worth noting that in addition to the contribution of the CLO application itself, THM in the environment can be converted to CLO [11,74].

Compared with other studies (Table S8), the total concentration of NNIs in the sediments of the Harbin section of the Songhua River is higher than that in the Guangzhou section of the Pearl River (1.38 ng g-1 dw) [31] and Belize (0.036 ng g-1 dw) [29], but lower than that in samples from South China (4.21 ng g-1 dw) [33] and Canada (40.8 ng g-1 dw) [75]. Higher residual concentrations and detection frequencies in the sediments were primarily associated with the intense and long-term use of NNIs in the area. Besides, the sediment composition of NNIs in this study was similar to those in Canada's wetland [75], with IMI, THM, and CLO as dominant species, but was different from those in the Guangzhou section of the Pearl River [31], where NNIs was dominated by ACE while IMI was not detected. The composition of NNIs in sediments varies with site location, which may be related to specific use patterns in each region as well as sediment composition.

3.2. Distribution of NNIs in surface water and sediment

The mass concentrations of NNIs detected in the four tributaries were significantly higher than that in the mainstream of the Songhua River (p < 0.05), indicating that the NNIs in mainstream mainly come from the inflow of high-polluted tributaries. In the mainstream surface water, the sum concentration of the seven NNIs fluctuated slightly (from 30.8 to 46.0 ng L-1). The concentration of NNIs at sites M1 and M3 is slightly higher than those at the other mainstream sampling sites. To some extent, this phenomenon might be attributed to the samples at these two sites were taken during the rainy season (September) with frequent rainfall, which resulted in increased surface runoff [76,77], and thus NNIs transfer from soil to water bodies.

The highest concentrations of NNIs in surface water were observed at the sampling sites T2, T4, and T3 with 135 ng L-1, 114 ng L-1, and 111 ng L-1, respectively. Site T2 is located in the Hejiagou River, an affluent river flowing through factories, enterprises, and residential areas that releases vast quantities of industrial and domestic waste into the river. Moreover, site T2 is situated downstream of the Qunli WWTP, in which around 250,000 tons of sewage were treated daily.

The high NNIs level at T4 (Ashi River) was attributed to the flow from many villages and towns in Harbin and several WWTPs along the river discharging sewage. The Ashi River has many tributaries, a wide area of arable land, and heavy pesticide use [49].

Site T3 is situated 1 km upstream of the inlet of the Majiagou River, a tributary of the south bank of the Songhua River. This tributary is an inner-city river formed by rain-collecting, which flows through four administrative districts of Harbin City: Pingfang District, Xiangfang District, Nangang District, and Daowai District. High population density, intensive human activity, and the presence of multiple WWTPs are the main characteristics of the above-mentioned districts. The concentration of target chemicals in the effluent of the WWTP may be influenced by the physicochemical properties of NNIs and the efficacy of the WWTP process. Previous reports have been confirmed the low removal efficiency of NNIs from wastewater by conventional treatment procedures [31,73]. Hence effluents from WWTPs are important point sources of NNIs in the water environment.

Compared to other tributaries, the Yunliang River (site T1) flows through a region mainly dominated by agricultural production. However, it is noteworthy that Σ7NNIs in the Yunliang River (49.8 ng L-1) is similar to that found in the mainstream (mean 40.1 ng L-1), indicating that the confluence of this tributary does not pose a serious threat to the mainstream of the Songhua River. As indicated above, intensive human activities and sewage outfalls, compared with agricultural activities, might be the major causes for the high levels of NNIs in water bodies in this region. For example, NNIs have been extensively applied to human activities such as horticulture, urban landscaping, household pest bait, and pet flea control [1,31,73]. In addition, NNIs can enter the human body through food consumption and then enter the urban sewage system via metabolites such as urine.

In the sediments, there was no significant difference in NNIs concentrations between tributaries and mainstream (p > 0.05). Four NNIs were detected at the T3 sampling site, and three were detected at the other sediment sampling sites, which may be attributed to the higher TOC content at T3. The relationship between NNIs and TOC in sediments was analyzed using Spearman correlation (Fig. S2). ACE was not studied because it was only detected at site T3. In sediments, the concentration of IMI (r = 0.82, p < 0.05), CLO (r = 0.62, p < 0.05), and Σ4NNIs (r = 0.82, p < 0.05) had a significant positive correlation with TOC, while there was no correlation between THM and TOC. Early studies suggest a positive correlation with the organic matter content of the soil/sediment in the sorption capability of NNIs, i.e., the sorption capacity of NNIs is enhanced when the organic matter content increases [74].

3.3. Sediment-water exchange

Sediment-water exchange behavior plays an important role in affecting water quality and the fate of NNIs. We focused on three NNIs, including IMI, THM, and CLO, coexisted in both water bodies and sediments. The analysis results (Fig. S3) showed that the ff values of IMI, THM, and CLO were greater than 0.9, indicating the tendency to diffuse into the water from the sediment for the three pesticides. Because of their high solubility and low Kow, NNIs cannot be prevented from entering the water body from sediment. In addition, the ff values (range from 0.997 to 0.999) of the three NNIs fluctuated slightly, indicating that the similar sediment-water exchange mechanisms of the individual NNIs across the Harbin section of the Songhua River, with no obvious spatial variability. Consequently, IMI, THM, and CLO from various pollution discharge sources entered the Songhua River, where they were enriched in the sediment through processes such as sedimentation. Meanwhile, the sediment stored NNIs can re-enter into the water through molecular diffusion process, causing secondary pollution of the water body. The concentration ratio measures the equilibrium of the partition of chemicals and reflects the difference in the forces acting on the substances between the two phases. The ratios of IMI, THM, and CLO concentrations in the water to those in the sediment (Cw/Cs, g·L-1) were in the range of 4.68–84.1, 28.3–254, and 19.2–118, respectively. These concentration ratios indicate that NNIs are less concentrated in the sediment, have weaker interaction with the sediment, and are easily released from sediment into the water. These results are consistent with those reported by Yi et al. [31] on the sediment-water partition coefficients in the Pearl River, which found that NNIs are mostly distributed in the water bodies and are easily transferred with runoff or riverine transport. Therefore, the historical accumulated NNIs in sediment can be released into water bodies, with the sediment acting as a secondary source.

3.4. Exposure estimation for human

Table 2 demonstrates the daily intake of NNIs in the form of drinking water for different age groups. The largest intake of NNIs was from THM in all age groups, indicating the highest risk from THM among all the different NNIs. From the perspective of the different age groups, exposure content via drinking water was in the order of infants > toddlers > children > adults > teenagers. The maximum daily intake of the total NNIs in infants (31.9 ng kg-1 bw·d-1) was about five times higher than that of teenagers (5.69 ng kg-1 bw·d-1). Infant exposure levels are higher due to their higher food and fluid (mushy complementary foods such as vegetables, fruits, eggs, and cereals) intake per unit body-weight basis compared to the other age groups. Similar EDI of NNIs for infants have been found in breast milk (40.4 ng kg-1 bw·d-1) in Heilongjiang Province [78]. In China, the mean concentration of all NNIs in breast milk was 161 g L-1, while the mean value in Heilongjiang Province was 181 g L-1 [78]. Overall, the estimated maximum ΣIMIeq EDI (infants: 31.9 ng kg-1 bw·d-1) was three orders of magnitude lower than the U.S. EPA recommended acceptable daily intake of IMI (57000 ng kg-1 bw·d-1). In general, all pathways of ingestion (both food and water), contact with skin, inhalation, and non-dietary ingestion can cause the exposure risk to human health, and thus exposure to NNIs through drinking water consumption is underestimated in the current study. However, the high solubility of NNIs and limitation of studied environmental media (water and sediment) promoted us to only assess the exposure risk through the drinking water pathway. Although these results suggested the risk posed by parent compounds through drinking water was low, the risk of NNIs metabolites cannot be ignored. For example, IMI-olefin is ten times more toxic than IMI, and desnitro-IMI binds more than 300 times to vertebrate nAChRs than IMI [79]. In addition, Marfo et al. [14] have obtained urine from 85 Japanese volunteers and found a correlation between urinary concentrations of N-desmethyl-acetamiprid and typical symptoms such as recent memory loss, finger tremors, generalized fatigue, abdominal pain, headache, and chest pain. Therefore, although the ΣIMIeq EDI was lower than the IMI guideline, the potential health risks of maternal metabolites, particularly in vulnerable populations such as infants and pregnant women, need further attention. In addition, the human body can be exposed to NNIs in various forms, including dietary intake, soil/dust exposure, and respiratory intake, the consequences of which cannot be overlooked, especially dietary intake [43,80].

Table 2.

Estimated daily intake of NNIs (ng·kg-1 bw·d-1) from the Harbin section of the Songhua River.

| IMI | THM | CLO | THA | ACE | DIN | IMIT | ΣIMIeq EDI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infants (<1 year) | 2.02 | 26.2 | 1.79 | 1.03 | 0.14 | 0.74 | 0.016 | 31.9 |

| Toddlers (1–3 years) | 0.70 | 9.05 | 0.62 | 0.36 | 0.05 | 0.26 | 0.006 | 11.0 |

| Children (4–11 years) | 0.65 | 8.47 | 0.58 | 0.33 | 0.05 | 0.24 | 0.005 | 10.3 |

| Teenagers (11–21 years) | 0.36 | 4.68 | 0.32 | 0.18 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.003 | 5.69 |

| Adults (≥21 years) | 0.45 | 5.84 | 0.40 | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.004 | 7.11 |

IMI: imidacloprid; THM: thiamethoxam; CLO: clothianidin; THA: thiacloprid; ACE: acetamiprid; DIN: dinotefuran; IMIT: imidaclothiz; ΣIMIeq EDI: sum up IMIeq EDI of each NNI.

3.5. Potential risk assessment to aquatic ecosystem

Existing studies have shown that residual NNIs in rivers can adversely affect the ecological environment of waters, such as effects on species diversity and structure of aquatic organisms [30]. In this study, the ecological risk of aquatic species in the Harbin section of the Songhua River was assessed using the SSD model with input of the toxicity data of imidacloprid to aquatic organisms at different trophic levels. Judging from the SSD curve (Fig. 3), aquatic organisms with lower trophic levels are more sensitive to NNIs and more vulnerable to be harmed. The harmed low trophic level species can cause damage to the stability and balance of the aquatic ecosystem because low trophic level species in the aquatic body are situated at the bottom of the food chain, and they provide food and nutrients to predators or higher trophic level species. For example, in terms of the acute risk from IMI (Fig. 3a), the most sensitive species is Epeorus longimanus (mayfly family) at the lower trophic level with acute toxicity at IMIeq concentrations of 650 ng L-1 in water, and the least sensitive species is Labeo rohita (a fish) at the higher trophic level with an acute risk concentration of 550000 ng L-1. In terms of the chronic risks from IMI (Fig. 3b), the most sensitive species is Caenidae (mayfly family) with chronic toxicity at IMIeq concentrations of 400 ng L-1 in water, and the least sensitive species is Labeo rohita, consistent with the acute risk, with a sensitivity value concentration of 120000 ng L-1. Notably, algae, despite being at a lower trophic level, are less sensitive to IMI than mayfly organisms because NNIs act as an insecticide.

Fig. 3.

Species sensitivity distribution for (a) acute toxicity and (b) chronic toxicity of NNIs to aquatic organisms in the Harbin section of Songhua River. Different colored dots represent the acute (EC50/LC50) or chronic (NOEC) toxicity data of different aquatic species.

The acute HC5 value of IMI for aquatic organisms in this study was 355 ng L-1 (95% confidence interval: 46.1–2742 ng L-1), and the chronic HC5 value was 165 ng L-1 (95% confidence interval: 26.0–1047 ng L-1). When the residual concentrations exceeded the above threshold values, adverse effects can occur on more than 5% of aquatic species. The IMIeq concentrations in all samples in the Harbin section of the Songhua River ranged from 178 to 838 ng L-1 (Fig. S4). The IMIeq concentrations in the mainstream were lower than the acute HC5 value, while those in the tributaries exceeded this value except at site T1. In contrast, all surface water samples exceeded the chronic HC5 values. The above results indicate that some aquatic organisms in the water of the Harbin section of the Songhua River are exposed to chronic/acute risk of NNIs, especially for aquatic species at lower trophic levels.

4. Conclusions

NNIs were detected with high frequency and at high levels in the Harbin section of the Songhua River, which indicated that NNI contamination was prevalent in the aquatic environment of the region. Of which, IMI, THM, and CLO in water bodies and sediments are ubiquitous NNIs. There was no obvious spatial variability through reflecting of the sediment-water exchange process, i.e., although NNIs can accumulate in the sediment through processes of sedimentation and diffusion between water and sediment, and then re-entered into water bodies through secondary release, resulting in secondary pollution of the water. The potential risks of humans and aquatic organisms have been assessed through relative efficacy factors and species sensitivity distributions. Among all age groups, the estimated daily intake of NNIs resulting from drinking water consumption was significantly lower than the cRfD of IMI recommended by the U.S. EPA. According to our ecological risk assessment, aquatic organisms at lower trophic levels are more vulnerable to the chronic/acute risks posed by NNIs, which can destabilize the balance of the aquatic ecosystem. These data are necessary to take further legal actions to assess related risks to protect human health and terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, and long-term monitoring programs are urgently needed to manage NNIs risks in China.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51779047) and the Excellent Youth Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province (YQ2019E001).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ese.2021.100128.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Goulson D. An overview of the environmental risks posed by neonicotinoid insecticides. J. Appl. Ecol. 2013;50:977–987. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahai G., Wan Y.J., Xia W., Yang S.Y., He Z.Y., Xu S.Q. Neonicotinoid insecticides in surface water from the central Yangtze River, China. Chemosphere. 2019;229:452–460. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han W.C., Tian Y., Shen X.M. Human exposure to neonicotinoid insecticides and the evaluation of their potential toxicity: an overview. Chemosphere. 2018;192:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.10.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitehorn P.R., O'Connor S., Wackers F.L., Goulson D. Neonicotinoid pesticide reduces bumble bee colony growth and queen production. Science. 2012;336(6079):351–352. doi: 10.1126/science.1215025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahai G., Wan Y.J., Xia W., Wang A.Z., Shi L.S., Qian X., He Z.Y., Xu S.Q. A nationwide study of occurrence and exposure assessment of neonicotinoid insecticides and their metabolites in drinking water of China. Water Res. 2021;189:116630. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu C.S., Lu Z.B., Lin S., Dai W., Zhang Q. Neonicotinoid insecticides in the drinking water system-Fate, transportation, and their contributions to the overall dietary risks. Environ. Pollut. 2020;258:113722. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox-Foster D.L., Conlan S., Holmes E.C., Palacios G., Evans J.D., Moran N.A., Quan P.L., Briese T., Hornig M., Geiser D.M., Martinson V., vanEngelsdorp D., Kalkstein A.L., Drysdale A., Hui J., Zhai J., Cui L., Hutchison S.K., Simons J.F., Egholm M., Pettis J.S., Lipkin W.I. A metagenomic survey of microbes in honey bee colony collapse disorder. Science. 2017;318(5848):283–287. doi: 10.1126/science.1146498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crall J.D., Switzer C.M., Oppenheimer R.L., Versypt A.N.F., Dey B., Brown A., Eyster M., Guérin C., Pierce N.E., Combes S.A., de Bivort B.L. Neonicotinoid exposure disrupts bumblebee nest behavior, social networks, and thermoregulation. Science. 2018;362(6415):683–686. doi: 10.1126/science.aat1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mason R., Tennekes H., Sánchez-Bayo F., Jepsen P.U. Immune suppression by neonicotinoid insecticides at the root of global wildlife declines. J. Environ. Immunol. Toxicol. 2013;1(1):3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez-Antia A., Ortiz-Santaliestra M.E., Mougeot F., Mateo R. Imidacloprid-treated seed ingestion has lethal effect on adult partridges and reduces both breeding investment and offspring immunity. Environ. Res. 2015;136:97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morrissey C.A., Mineau P., Devries J.H., Sanchez-Bayo F., Liess M., Cavallaro M.C., Liber K. Neonicotinoid contamination of global surface waters and associated risk to aquatic invertebrates: a review. Environ. Int. 2015;74:291–303. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2014.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan S.H., Wang J.H., Zhu L.S., Chen A.M., Wang J. Thiamethoxam induces oxidative stress and antioxidant response in zebrafish (Danio Rerio) livers. Environ. Toxicol. 2016;31(12):2006–2015. doi: 10.1002/tox.22201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li B., Xia X.M., Wang J.H., Zhu L.S., Wang J., Wang G.C. Evaluation of acetamiprid-induced genotoxic and oxidative responses in Eisenia fetida. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018;161:610–615. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marfo J.T., Fujioka K., Ikenaka Y., Nakayama S.M.M., Mizukawa H., Aoyama Y., Ishizuka M., Taira K. Relationship between urinary N-desmethyl-Acetamiprid and typical symptoms including neurological findings: a prevalence case-control study. PLoS One. 2015;10(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Commission E. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/783 of 29 May 2018 Amending Implementing Regulation (EU) No 540/2011 as regards the conditions of Approval of the active substance imidacloprid. Off. J. Eur. Union. 2018;61:31–35. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Commission E. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/784 of 29 May 2018 Amending Implementing Regulation (EU) No 540/2011 as regards the conditions of approval of the active substance clothianidin. Off. J. Eur. Union. 2018;132:35. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Commission E. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/785 of 29 May 2018 Amending Implementing Regulation (EU) No 540/2011 as regards the conditions of approval of the active substance thiamethoxam. Off. J. Eur. Union. 2018;132:40. [Google Scholar]

- 18.France, Ban on neonicotinoid insecticides: France is leading the way in Europe. 2018. https://www.gouvernement.fr/en/ban-on-neonicotinoid-insecticides-france-is-leading-the-way-in-europe Available at:

- 19.France, France's ban on bee-killing pesticides begins Saturday. 2018. Available at: https://phys.org/news/2018-08-france-bee-killing-pesticides-saturday.html.

- 20.Canada, Re-evaluation Decision RVD2019-04, thiamethoxam and its associated end-use products: pollinator Re-evaluation. 2019. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/consumer-product-safety/reports-publications/pesticides-pest-management/decisions-updates/reevaluation-decision/2019/thiamethoxam.html Available at:

- 21.Canada, Re-evaluation Decision RVD2019-05, clothianidin and its associated end-use products: pollinator Re-evaluation. 2019. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/consumer-product-safety/reports-publications/pesticides-pest-management/decisions-updates/reevaluation-decision/2019/clothianidin.html Available at:

- 22.Canada, Re-evaluation Decision RVD2019-06, imidacloprid and its associated end-use products: pollinator Re-evaluation. 2019. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/consumer-product-safety/reports-publications/pesticides-pest-management/decisions-updates/reevaluation-decision/2019/imidacloprid.html Available at:

- 23.U.S. EPA, United States Environmental Protection Agency Clothianidin and thiamethoxam proposed Interim registration review Decision case number 7620 and 7614. https://www.epa.gov/pollinator-protection/proposed-interim-registration-review-decision-neonicotinoids Docket Number EPA-HQ-OPP-2011-0865 and EPA-HQ-OPP-2011-0581, 2020. Available at:

- 24.U.S. EPA. United States Environmental Protection Agency Imidacloprid proposed Interim registration review Decision case number 7605. https://www.epa.gov/pollinator-protection/proposed-interim-registration-review-decision-neonicotinoids Docket Number EPA-HQ-OPP-2008-0844 2020. Available at:

- 25.U.S. EPA. United States Environmental Protection Agency Dinotefuran proposed Interim registration review Decision case number 7441. https://www.epa.gov/pollinator-protection/proposed-interim-registration-review-decision-neonicotinoids Docket Number EPA-HQ-OPP-2011-0924, 2020. Available at:

- 26.Bass C., Denholm I., Williamson M.S., Nauen R. The global status of insect resistance to neonicotinoid insecticides. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2015;121:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dai Y.J., Ji W.W., Chen T., Zhang W.J., Liu Z.H., Ge F., Yuan S. Metabolism of the Neonicotinoid insecticides acetamiprid and thiacloprid by the yeast Rhodotorula mucilaginosa strain IM-2. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010;58(4):2419–2425. doi: 10.1021/jf903787s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan L.C., Cheng Y., Bu Y.Q., Zhou J.Y., Shan Z.J. Registration status review and primary risk assessment to bees of neonicotinoid pesticides (in Chinese) Asian J. Ecotoxicol. 2019;14(6):292–303. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonmatin J.M., Noome D.A., Moreno H., Mitchell E.A.D., Glauser G., Soumana O.S., van Lexmond M.B., Sánchez-Bayo F. A survey and risk assessment of neonicotinoids in water, soil and sediments of Belize. Environ. Pollut. 2019;249:949–958. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.03.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen Y.C., Zang L., Shen G.F., Liu M.D., Du W., Fei J., Yang L.Y., Chen L., Wang X.J., Liu W.P., Zhao M.R. Resolution of the ongoing challenge of estimating nonpoint source neonicotinoid pollution in the Yangtze River Basin using a modified mass balance approach. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019;53(5):2539–2548. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b06096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yi X.H., Zhang C., Liu H.B., Wu R.R., Tian D., Ruan J.J., Zhang T., Huang M.Z., Ying G.G. Occurrence and distribution of neonicotinoid insecticides in surface water and sediment of the Guangzhou section of the Pearl River, South China. Environ. Pollut. 2019;251:892–900. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang C., Tian D., Yi X.H., Zhang T., Ruan J.J., Wu R.R., Chen C., Huang M.Z., Ying G.G. Occurrence, distribution and seasonal variation of five neonicotinoid insecticides in surface water and sediment of the Pearl Rivers, South China. Chemosphere. 2019;217:437–446. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang Z.B., Li H.Z., Wei Y.L., Xiong J.J., You J. Distribution and ecological risk of neonicotinoid insecticides in sediment in South China: impact of regional characteristics and chemical properties. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;714:136878. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang C., Yi X.H., Chen C., Tian D., Liu H.B., Xie L.T., Zhu X.P., Huang M.Z., Ying G.G. Contamination of neonicotinoid insecticides in soil-water-sediment systems of the urban and rural areas in a rapidly developing region: Guangzhou, South China. Environ. Int. 2020;139:105719. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forero L.G., Limay-Rios V., Xue Y., Schaafsma A. Concentration and movement of neonicotinoids as particulate matter downwind during agricultural practices using air samplers in southwestern Ontario, Canada. Chemosphere. 2017;188:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.08.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou Y., Guo J.Y., Wang Z.K., Zhang B.Y., Sun Z., Yun X., Zhang J.B. Levels and inhalation health risk of neonicotinoid insecticides in fine particulate matter (PM2.5) in urban and rural areas of China. Environ. Int. 2020;142:105822. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salis S., Testa C., Roncada P., Armorini S., Rubattu N., Ferrari A., Miniero R., Brambilla G. Occurrence of imidacloprid, carbendazim, and other biocides in Italian house dust: potential relevance for intakes in children and pets. J. Environ. Sci. Health B. 2017;52:699–709. doi: 10.1080/03601234.2017.1331675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang A.Z., Mahai G., Wan Y.J., Jiang Y., Meng Q.Q., Xia W., He Z.Y., Xu S.Q. Neonicotinoids and carbendazim in indoor dust from three cities in China: spatial and temporal variations. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;695:133790. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.133790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Osaka A., Ueyama J., Kondo T., Nomura H., Sugiura Y., Saito I., Nakane K., Takaishi A., Ogi H., Wakusawa S., Ito Y., Kamijima M. Exposure characterization of three major insecticide lines in urine of young children in Japan-neonicotinoids, organophosphates, and pyrethroids. Environ. Res. 2016;147:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2016.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang T., Song S.M., Bai X.Y., He Y., Zhang B., Gui M.W., Kannan K., Lu S.Y., Huang Y.Y., Sun H.W. A nationwide survey of urinary concentrations of neonicotinoid insecticides in China. Environ. Int. 2019;132:105114. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bonmatin J.M., Mitchell E.A.D., Glauser G., Lumawig-Heitzmann E., Claveria F., van Lexmond M.B., Taira K., Sánchez-Bayo F. Residues of neonicotinoids in soil, water and people's hair: a case study from three agricultural regions of the Philippines. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;757:143822. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang N., Wang B.T., Zhang Z.P., Chen X.F., Huang Y., Liu Q.H., Zhang H. Occurrence of neonicotinoid insecticides and their metabolites in tooth samples collected from South China: associations with periodontitis. Chemosphere. 2021;264:128498. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen D.W., Zhang Y.P., Lv B., Liu Z.B., Han J.J., Li J.G., Zhao Y.F., Wu Y.N. Dietary exposure to neonicotinoid insecticides and health risks in the Chinese general population through two consecutive total diet studies. Environ. Int. 2020;135:105399. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watanabe E., Kobara Y., Baba K., Eun H. Determination of seven neonicotinoid insecticides in cucumber and eggplant by water-based extraction and high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal. Lett. 2015;48(2):213–220. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun C.Y., Zhang Z.X., Cao H.N., Xu M., Xu L. Concentrations, speciation, and ecological risk of heavy metals in the sediment of the Songhua River in an urban area with petrochemical industries. Chemosphere. 2019;219:538–545. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li K.Y., Cui S., Zhang F.X., Hough R., Fu Q., Zhang Z.L., Gao S., An L.H. Concentrations, possible sources and health risk of heavy metals in multi-media environment of the Songhua River, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020;17:1766. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhai Y., Xia X., Yang G., Lu H., Ma G., Wang G., Teng Y., Yuan W., Shrestha S. Trend, seasonality and relationships of aquatic environmental quality indicators and implications: an experience from songhua river, NE China. Ecol. Eng. 2020;145:105706. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cui S., Zhang F.X., Hu P., Hough R., Fu Q., Zhang Z.L., An L.H., Li Y.-F., Li K.Y., Liu D., Chen P.Y. Heavy metals in sediment from the urban and rural rivers in Harbin city, northeast China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2019;16:4313. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16224313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cui S., Gao S., Zhang F.X., Fu Q., Wang M., Liu D., Li K.Y., Song Z.H., Chen P.Y. Heavy metal contamination and ecological risk in sediment from typical suburban rivers. River Res. Appl. 2020:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cui S., Fu Q., Li T.X., Ma W.L., Liu D., Wang M. Sediment-water exchange, spatial variations, and ecological risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the Songhua River, China. Water. 2016;8:334. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cui S., Li K.Y., Fu Q., Li Y.-F., Liu D., Gao S., Song Z.H. Levels, spatial variations, and possible sources of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in sediment from Songhua River, China, Arab. J. Geosci. 2018;11:445. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu H.Y., Liu Y.F., Han C.X., Fang H., Weng J.H., Shu X.Q., Pan Y.W., Ma L.M. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surface waters from the seven main river basins of China: spatial distribution, source apportionment, and potential risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;752:141764. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.You H., Ding J., Zhao X.S., Li Y.-F., Liu L.Y., Ma W.L., Qi H., Shen J.M. Spatial and seasonal variation of polychlorinated biphenyls in Songhua River, China. Environ. Geochem. Health. 2011;33(3):291–299. doi: 10.1007/s10653-010-9341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cui S., Fu Q., Li Y.-F., Li W.L., Li T.X., Wang M., Xing Z.X., Zhang L.J. Levels, congener profile and inventory of polychlorinated biphenyls in sediment from the Songhua River in the vicinity of cement plant, China: a case study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016;23:15952–15962. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-6761-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cui S., Fu Q., Guo L., Li Y.-F., Li T.X., Ma W.L., Wang M., Li W.L. Spatial-temporal variation, possible source and ecological risk of PCBs in sediments from Songhua River, China: effects of PCB elimination policy and reverse management framework. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016;106:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang W.H., Wang H., Zhang W.F., Liang H., Gao D.W. Occurrence, distribution, and risk assessment of antibiotics in the Songhua River in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017;24:19282–19292. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-9471-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.He S.N., Dong D.M., Zhang X., Sun C., Wang C.Q., Hua X.Y., Zhang L.W., Guo Z.Y. Occurrence and ecological risk assessment of 22 emerging contaminants in the Jilin Songhua River (Northeast China) Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018;25:24003–24012. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-2459-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhu Y.G., Zhai Y.Z., Teng Y.G., Wang G.Q., Du Q.Q., Wang J.S., Yang G. Water supply safety of riverbank filtration wells under the impact of surface water-groundwater interaction: evidence from long-term field pumping tests. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;711:135141. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dankyi E., Gordon C., Carboo D., Fomsgaard I.S. Quantification of neonicotinoid insecticide residues in soils from cocoa plantations using a QuEChERs extraction procedure and LC-MS/MS. Sci. Total Environ. 2014;499:276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou Y., Lu X.X., Fu X.F., Yu B., Wang D., Zhao C., Zhang Q., Tan Y., Wang X.Y. Development of a fast and sensitive method for measuring multiple neonicotinoid insecticide residues in soil and the application in parks and residential areas. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2018;1016:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2018.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sultana T., Murray C., Kleywegt S., Metcalfe C.D. Neonicotinoid pesticides in drinking water in agricultural regions of southern Ontario, Canada. Chemosphere. 2018;202:506–513. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.02.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cui S., Hough R., Yates K., Osprey M., Kerr C., Cooper P., Coull M., Zhang Z.L. Effects of season and sediment-water exchange processes on the partitioning of pesticides in the catchment environment: implications for pesticides monitoring. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;698:134228. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li D.F., Zhai Y.Z., Lei Y., Li J., Teng Y.G., Lu H., Xia X.L., Yue W.F., Yang J. Spatiotemporal evolution of groundwater nitrate nitrogen levels and potential human health risks in the Songnen Plain, Northeast China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021;208:111524. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.111524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.U.S. EPA . U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; Washington, DC: 2010. Development of a Relative Potency Factor (RPF) Approach for Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon (PAH) Mixtures. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wan Y.J., Wang Y., Xia W., He Z.Y., Xu S.Q. Neonicotinoids in raw, finished, and tap water from Wuhan, Central China: assessment of human exposure potential. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;675:513–519. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.04.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang L.J., Qian L., Ding L.Y., Wang L., Wong M.H., Tao H.C. Ecological and toxicological assessments of anthropogenic contaminants based on environmental metabolomics. Environmental Science and Ecotechnology. 2021;5:100081. doi: 10.1016/j.ese.2021.100081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Klepper O., Bakker J., Traas T.P., van de Meent D. Mapping the potentially affected fraction (PAF) of species as a basis for comparison of ecotoxicological risks between substances and regions. J. Hazard Mater. 1998;61(1–3):337–344. [Google Scholar]

- 68.U.S. EPA. United States Environmental Protection Agency . 2017. Aquatic Life Benchmarks and Ecological Risk Assessments for Registered Pesticides.https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-science-and-assessing-pesticide-risks/aquatic-life-benchmarks-and-ecological-risk#ref_1 Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xiong J.J., Wang Z., Ma X., Li H.Z., You J. Occurrence and risk of neonicotinoid insecticides in surface water in a rapidly developing region: application of polar organic chemical integrative samplers. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;648:1305–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cui S., Song Z.H., Zhang L.M., Shen Z.X., Hough R., Zhang Z.L., An L.H., Fu Q., Zhao Y.C., Jia Z.Y. Spatial and temporal variations of open straw burning based on fire spots in northeast China from 2013 to 2017, Atmos. Environ. Times. 2021;244:117962. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Heilongjiang Bureau of Statistics (HBS) China Statistics Press; Beijing: 2020. Heilongjiang Statistical Yearbook. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang H.D., Jiang Q., Wang J.K., Li K.F., Wang F. Analysis on the impact of two winter precipitation episodes on PM2.5 in Beijing. Environmental Science and Ecotechnology. 2021;5:100080. doi: 10.1016/j.ese.2021.100080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sadaria A.M., Supowit S.D., Halden R.U. Mass balance assessment for six neonicotinoid insecticides during conventional wastewater and wetland treatment: nationwide reconnaissance in United States wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;50(12):6199–6206. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b01032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wu R.L., He W., Li Y.L., Li Y.Y., Qin Y.F., Meng F.Q., Wang L.G., Xu F.L. Residual concentrations and ecological risks of neonicotinoid insecticides in the soils of tomato and cucumber greenhouses in Shouguang, Shandong Province, East China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;738:140248. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Main A.R., Headley J.V., Peru K.M., Michel N.L., Cessna A.J., Morrissey C.A. Widespread use and frequent detection of neonicotinoid insecticides in wetlands of Canada's Prairie Pothole Region. PLoS One. 2014;9(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang Z.Y., Hua P., Dai H., Li R., Xi B.D., Gui D.W., Zhang J., Krebs P. Influence of surface properties and antecedent environmental conditions on particulate-associated metals in surface runoff. Environmental Science and Ecotechnology. 2020;2:100017. doi: 10.1016/j.ese.2020.100017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li J., Dai W., Sun Y., Li Y.H., Wang G.Q., Zhai Y.Z. Different runoff patterns determined by stable isotopes and multi-time runoff responses to precipitation in a seasonal frost area: a case study in the Songhua River basin, northeastern China. Nord. Hydrol. 2020;51(5):1009–1022. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen D.W., Liu Z.B., Barrett H., Han J.J., Lv B., Li Y., Li J.G., Zhao Y.F., Wu Y.N. Nationwide biomonitoring of neonicotinoid insecticides in breast milk and health risk assessment to nursing infants in the Chinese population. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020;68:13906–13915. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c05769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang A.Z., Mahai G., Wan Y.J., Yang Z., He Z.Y., Xu S.Q., Xia W. Assessment of imidacloprid related exposure using imidacloprid-olefin and desnitro-imidacloprid: neonicotinoid insecticides in human urine in Wuhan, China. Environ. Int. 2020;141:105785. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cui K., Wu X.H., Wei D.M., Zhang Y., Cao J.L., Xu J., Dong F.S., Liu X.G., Zheng Y.Q. Health risks to dietary neonicotinoids are low for Chinese residents based on an analysis of 13 daily-consumed foods. Environ. Int. 2021;149:106385. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.