Abstract

Designing non-noble electrocatalysts with low-cost and efficient is crucial to the development of sustainable and clean energy resources. Here, we synthesized a novel S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 and O–CoSe2/CoMoO4hybrid electrocatalysts for the HER and OER, respectively. Possibly due to the synergetic chemical coupling effects between CoSe2/DETA and CoMoO4, and the introduction of S heteroatom and oxygen vacancy, this hybrid could expose enough active edges, and then promoted the constructed hybrid displayed superior hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and oxygen evolution reaction (OER) catalytic performance. The S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 sample afforded a current density of 10 mAcm-2 at a small overpotential of 177 mV and a small Tafel slope of 54 mV dec−1. Moreover, the oxidized CoSe2/CoMoO4 (O–CoSe2/CoMoO4) also displayed a remarkable catalytic property for OER with a small Tafel slope of 43 mV dec−1, as well as excellent stability in 1.0 M KOH. Therefore, this noble-metal-free and highly efficient catalyst enables prospective applications for electrochemical applications.

Keywords: Hydrogen evolution, Hybrid, Synergetic, Oxygen evolution, Stability

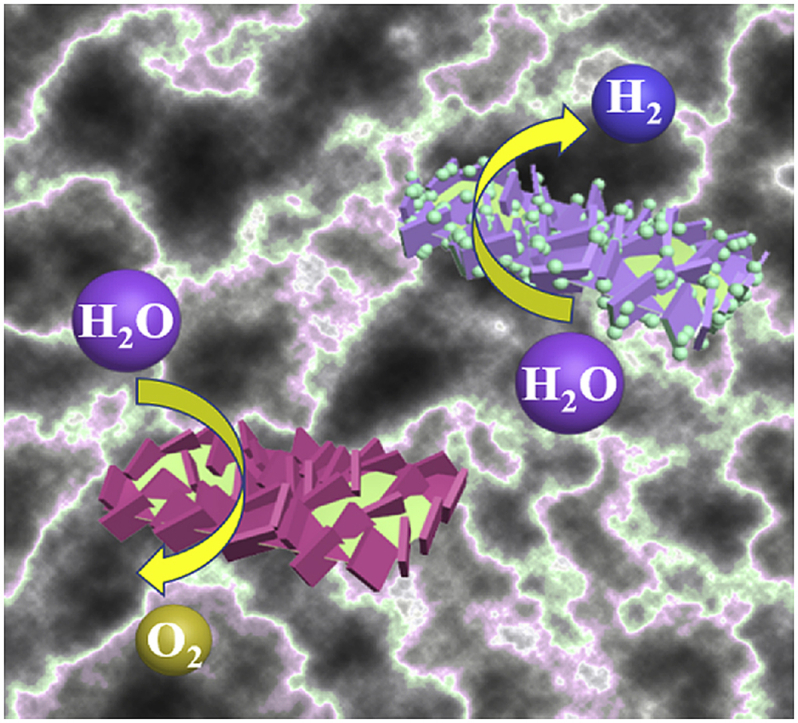

Graphical abstract

Owing to the synergetic coupling effects between CoSe2/DETA and CoMoO4, and the introduction of S heteroatom and oxygen vacancy, this hybrid could expose enough active edges, and then improved the intrinsic activity of the constructed hybrid for hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and oxygen evolution reaction (OER).

Highlights

-

•

The novel S-CoSe2/CoMoO4 and O-CoSe2/CoMoO4 hybrid electrocatalysts are reported.

-

•

The oxygen vacancy resulted in O-CoSe2/CoMoO4 displayed excellent stability for OER.

-

•

This non-noble based electrocatalysts are valuable for the future clean energy.

1. Introduction

With the rising concern in energy crisis and environmental pollution, there has been an urgent need to exploit renewable and clean energy resources to reduce our reliance on fossil fuel. Hydrogen (H2) has been considered as one of the most promising energy carriers to satisfy future energy systems, due to its high energy density, renewability and pollution-free characteristics [1]. For example, H2 has been used to produce electricity for vehicular and stationary applications to diminish the consumption of fossil fuel and CO2 emissions [2,3]. Until now, tremendous efforts have been devoted to synthesize H2, among which electrocatalytic water splitting for the generation of H2 is one of the most environmentally friendly and economical way for the future H2 economy [4,5]. The electrochemical water splitting involves two half reactions, including hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and oxygen evolution reaction (OER). Comparing with the HER, OER is concerned with various energy systems, such as metal-air batteries and regenerative fuel cells. Moreover, since the process usually involves four proton-coupled electrons transfer, O–H bond breaking, as well as attendant O–O bond formation, OER has been considered as a major bottleneck for realize large-scale water splitting [6]. Up to now, Pt, Ru and their alloys, are the most active electrocatalysts for the HER and OER, while their widespread application is serious restricted by their high cost and low earth-abundance [7,8]. Hence, designing and exploiting active and cost-effective catalysts with earth abundant elements for replacing precious metals is still a major challenge [9].

According to the Volmer-Heyrovsky-Tafel models, the reaction rate for the HER is relies on the adsorption and desorption of H atoms on the catalyst surface in acidic conditions [10]. The Sabatier principle shows that an efficient catalyst should have a free energy of hydrogen adsorption (ΔGH) that close to zero, in which the overall reaction rate is maximum [11]. Currently, numerous studies have focused on the development of non-noble-metal sulfides [12,13], phosphides [14,15], nitrides [16,17], selenides [18,19], and carbides [20,21]. Due to the unique electronic configuration and the intrinsic metallic nature, cobalt chalcogenides, including CoS2 and CoSe2, have been prepared and offered a unique advantage as electrocatalysts for the HER, oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) [22], OER [23] and sodium-ion battery [24]. Though CoSe2 shows extraordinary achievement towards the HER and OER, the low electrochemical performance of pure CoSe2 are still restricted in terms of activity and stability. Therefore, it is highly desirable to exploit high active and stable catalyst with remarkable activity. Recently, the composites of CoSe2 with CeO2 [25], WS2 [26], MoSe2 [27], and CoS228 were designed to enhance electrocatalytic activity. For example, Kang et al. [29] prepared CoSe2/CNT composite microspheres by spray pyrolysis and selenization, and the synthesized catalyst showed the superior electrocatalytic activity. Hou et al. [30] reported the fabrication of tubular-structured orthorhombic CoSe2 (o-CoSe2) and cubic CoSe2 (c-CoSe2) from Co3Se4 nanotubes and found they could be used as bifunctional electrocatalysts with high catalytic activity in alkaline medium for both dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs) and HER.

The strategy for the preparation of high activity electrocatalysts can be generally divided into two categories. The first one is dedicated to the construction and synthesis of different nanostructure catalysts, such as nanowires [31], nanoparticles [32], nanotubes [33], nanosheets [34], and nanobelts [35], because they provide large surface area, enhance diffusion of active sites, and expose the reactive lattice planes by releasing the gas bubbles adsorbed onto the catalyst surface [36]. The other method involves the optimization of the electronic structure of catalysts via doping [37,38], tuning the metal valence states and producing complex compounds [39,40]. In particular, chemical doping has been proposed as an attractive method to improve the catalytic activity of catalyst by means of altering the surface properties of catalyst, mainly including electronic band structure, synergistic coupling effect, and wettability properties [41]. Additionally, the introduction of heteroatom into nanostructure could facilitate the hydrophily of the solid-state surface towards water, and then increase the contact surface between electrolyte and electrode, leading to a better electron transfer and electrocatalytic activity [42]. Further studies found that the introduction of S with unsaturated edge sites could efficiently promote proton discharge in the HER system [43]. Furthermore, the previous report suggested that the oxygen vacancy play a key role in improving the catalytic activity for the OER, O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 was synthesized through the oxidation of CoSe2/CoMoO4 at air [44].

Hence, we put forward a facile route to prepare a novel hybrid non-noble electrocatalyst via hydrothermal sulfuration or oxidation using the hybrid of CoSe2/CoMoO4 as precursor. The morphology, surface properties, structural composition and electrocatalytic activity of the synthesized hybrid catalysts were systematically investigated. The results show that the strongly coupled nature of CoMoO4 and CoSe2/DETA, the assistance of S heteroatom and unique nanosheet structure, promoted the electrocatalyst exhibits a highly electrocatalytic activity for the HER. Moreover, the introduction of oxygen vacancy improved the OER performance of O– CoSe2/CoMoO4. The results reported here may offer a significant approach to investigate inexpensive non-noble metal hybrid materials for application in water splitting.

2. Materials and methods

In this work, Na2S, Na2SeO3, diethylenetriamine (DETA) and CoCl2·6H2O are purchased from Tianjin Damao Chemical Reagent Factory. Co(CH3COO)2·4H2O Tianjin Fuchen Chemical Reagent Factory. All of reagents were used without further purification.

2.1. Materials preparation

The fabrication of CoSe2 was according to the previous report [45]. In briefly, 1 mmol Co(CH3COO)2·4H2O and 1 mmol Na2SeO3 were added into 40 mL solution that composed of diethylenetriamine (DETA) and distilled water (V:V = 2:1), and the solution was stirred uniformly by using a magnetic stirrer for 0.5 h. The obtained mixture was then transferred to a 50 mL autoclave for reaction at 180 °C for 16 h. The precipitate was filtered, washed, and dried at 60 °C overnight.

2.2. Synthesis of CoSe2/DETA

In a typical synthesis, 1 mmol CoCl2·6H2O, 10 mmol urea and 0.1766 g of (NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O were dissolved in 40 mL of distilled water to form a clear solution. Next, 30 mg of CoSe2/DETA was added and mixed in an ultrasonication bath for 15 min. After that, the mixed solution was transferred into a 50 mL autoclave and maintained at 180 °C for 12 h, followed by filtering and drying. The obtained precursor was denoted as CoMoO4/CoSe2.

2.3. Synthesis of S–CoSe2/CoMoO4

For preparing S–CoSe2/CoMoO4, 1 g of Na2S was dissolved in the 40 mL DI water. Subsequently, 50 mg of CoSe2/CoMoO4 was added and the mixture was sonicated for 15 min to form a homogeneous dispersion, which was then transferred into a 50 mL autoclave and heated at 200 °C for 6 h. The precipitate was filtered, washed, and dried at 60 °C overnight.

2.4. Synthesis of O–CoSe2/CoMoO4

For preparing O–CoSe2/CoMoO4, CoSe2/CoMoO4 was carbonized for 2 h at different target temperatures with a heating rate of 5 °C min−1. The product was denoted as O–CoSe2/CoMoO4.

2.5. Physical measurements

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were carried out on a Merlin scanning electron microscope at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV (Zeiss, Germany) to examine the morphologies of the samples. For analyzing the species of the catalysts, Energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) elemental mapping mages were conducted on an X-MaxN20 dual detector system (Oxford, UK). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were determined on an ESCALAB 250Xi scanning X-ray microprobe (Thermo, USA). X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were performed on a Bruker diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 nm) (Germany). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were performed by using JEM-2100F microscope (Japan).

2.6. Electrochemical measurements

HER performances were conducted using CHI 760E electrochemical workstation (Shanghai Chenhua Co., China) in a conventional three-electrode cell configuration in 0.5 M H2SO4. A saturated calomel electrode (SCE) and graphite rod were used as the reference and counter electrodes, respectively. A glassy carbon electrode (3 mm in diameter) was selected as the working electrode. For preparing catalyst ink, 2.5 mg of catalyst was dispersed in 500 μL of the mixture solution composed of 240 μL of ethanol, 240 μL of water and 20 μL of 5 wt% nafion 117 solution and sonicated for 30 min. Then, 5 μL of catalyst suspension was dropped onto the glassy carbon electrode surface and dried at room temperature. Linear sweep voltammetry was performed at a scan rate of 5 mV s−1. EIS measurements were evaluated with frequency from 0.01 to 105 Hz at a potential of 0.15 V vs RHE. The electrochemical double-layer capacitances (Cdl) was test within a non-Faradaic region from −0.1 to −0.3 V vs SCE. The EDLC was calculated according to the equation of Cdl = (janodic-jcathodic)/2Rscan. janodic and jcathodic are current densities measured at −0.2 V vs SCE. All the potentials reported in our work were converted to a reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) and without iR-corrected.

The electrochemical OER test were carried out in a three-electrode configuration, with an Ag/AgCl and platinum foil as the reference and counter electrode, respectively. The working electrode was prepared by dropping 10 μL of the inks onto a polish and cleaned glassy carbon rotating disc electrode (RDE) with a diameter of 5 mm. The mass loading is about 0.225 mg cm−2. The electrolyte (1.0 M KOH) was bubbled with O2 for 30 min to ensure O2-saturation. The polarization curves were obtained at a scan rate of 5 mV s−1 and rotating speed of 1600 rpm. The stability test of O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 was performed by cyclic voltammetry for 1000 cycles by sweeping the potential from 0.8 to 0.2 V vs Ag/AgCl. EDLC was obtained in the non-Faradaic region (0.4–0.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl).

3. Results and discussion

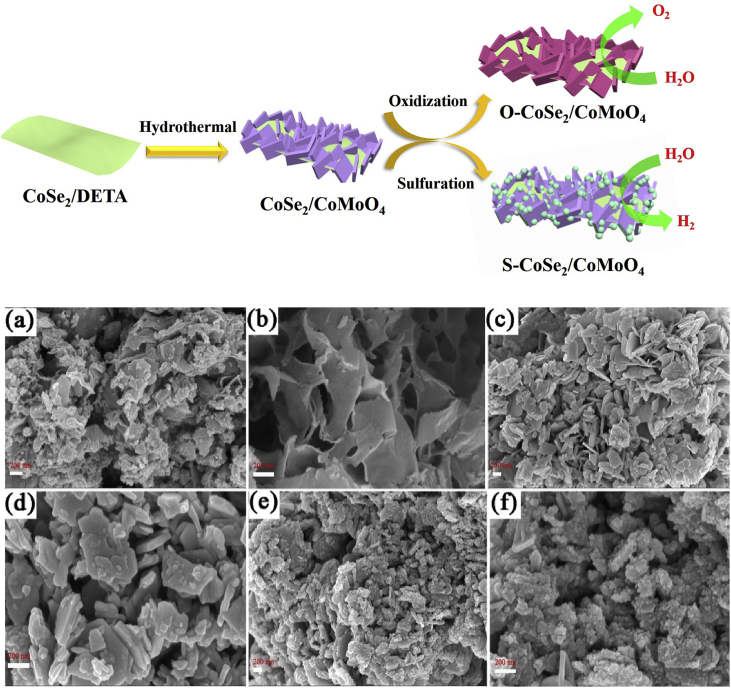

The synthesis procedure of S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 is schematically illustrated in Fig. 1. Firstly, CoSe2/DETA nanobelts were prepared through used DETA as the reaction medium and Na2SeO3 as selenide source. Subsequently, metal ions and urea were simultaneously added into the solution containing CoSe2/DETA nanobelts. This step involves the formation of Co–Mo precursors, which preferred nucleation on the surface of nanobelts through the coordination effect of CoSe2/DETA and metal ions during hydrothermal process [46]. The S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 hybrid was acquired via a facile thermal sulfuration process. In this step, the active sulfur anions that release from sodium sulfide could replace the OH− or CO32− anions of the precursors through the anion exchange reaction, leading to the formation of S-doped CoSe2/CoMoO4 hybrid nanosheet [47].

Fig. 1.

Top, schematic illustration of the formation of S -CoSe2/CoMoO4 and O -CoSe2/CoMoO4 catalysts. Bottom, SEM images of CoSe2/DETA (a, b), CoSe2/CoMoO4 (c, d) and S -CoSe2/CoMoO4 (e, f).

The morphology of CoSe2/DETA and other hybrid materials are shown in Fig. 1. CoSe2/DETA with a belt morphology is clearly observed. Moreover, some particles on the surrounding of belt could be found, which may be attributed to incomplete reaction (Fig. 1a and b). As shown in Fig. 1c and d, the CoSe2/DETA nanobelt is covered completely by the CoMoO4 nanosheets with smooth surface, implying the excellent couple of nanobelt and nanosheet. As can be seen from Fig. 1e and f, the resulting S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 surface is completely rough and most of nanoparticles are deposited onto the surface, which facilitated the adsorption of H atoms. The thickness of the nanosheets after sulfuration is increased compared with the initial precursor, suggesting the formation of S-doped CoSe2/CoMoO4 hybrid nanosheet.

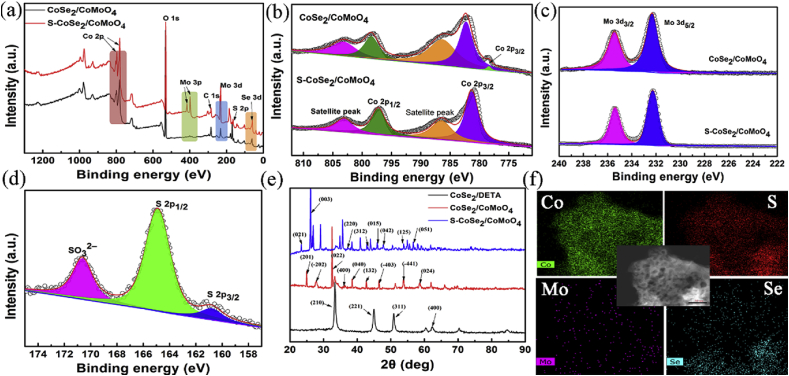

XPS measurements were carried out to analyze the electronic state and elemental compositions of catalyst. As shown in Fig. 2, the XPS spectrum of CoSe2/CoMoO4 and S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 revealed the obvious signals of the C, Mo, Se, and O, as well as Co and S, indicating S was successfully introduced into CoSe2/CoMoO4 as expected (Fig. 2a). As depicted in Co 2p spectrum (Fig. 2b), the Co2+ oxidation state of CoMoO4 is located at 780.5 eV and the binding energy at 782.5 eV corresponded to Co 2p3/2 [48]. The signal appeared at 798.4 eV is originated from the Co2+ cations of CoSe2 [30,49], while the satellite peaks at 786.7 and 803.3 eV corresponded to the shakeup-type peaks of Co at the high binding energy side of the edge [50]. The peak fitting of high-resolution Mo 3d spectra suggested that there were two oxidation states for Mo on the surface of CoSe2/CoMoO4 (Fig. 2c). Corresponding features in the Mo 3d core level spectra at 232.3 and 235.4 eV are the characteristic of Mo 3d5/2 and Mo 3d3/2 of Mo6+, implying the presence of the Mo6+ oxidation state [51]. For S–CoSe2/CoMoO4, the Co 2p region also exhibits several similar peaks at 781.3 (Co 2p3/2), 797.2 (oxidation state, Co2+), 786.5 and 803.1 eV (satellite peaks) [52]. The Se 3d spectrum of S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 can be deconvoluted into two species, which is similar to CoSe2/CoMoO4. The peak at 54.7 eV can be attributed to the metal-selenium bond, whereas the peak at 59.8 eV is most likely related to SeOx (Fig. S1) [23,53]. The S 2p singlet at 164.9 eV can be attributed to the sulfur-metal bonds (Fig. 2d). The high energy of 170.6 eV is in good agreement with the S4+ species at the surface or edges of S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 [54]. Thus, the XPS analysis confirmed that the composition of S–CoSe2/CoMoO4. Meanwhile, it suggested S was doped into the structure of CoSe2/CoMoO4 through forming sulfur-metal bonds.

Fig. 2.

(a) XPS survey spectra of CoSe2/CoMoO4 and S–CoSe2/CoMoO4. (b) Co 2p and (c)Mo 3d spectra of CoSe2/CoMoO4 and S–CoSe2/CoMoO4. (d) S 2p XPS spectra of S–CoSe2/CoMoO4. (e) XRD patterns of CoSe2/DETA, CoSe2/CoMoO4, and S–CoSe2/CoMoO4. (f) Elemental mapping images of S–CoSe2/CoMoO4.

XRD measurements were performed to investigate the structural information of samples. The XRD patterns of CoSe2/DETA, CoSe2/CoMoO4, and S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 are illustrated in Fig. 2e. The typical diffraction peaks of CoSe2/DETA at 33.5°, 45.1°, 50.8° and 62.4° can be indexed to the (210), (221), (311) and (400) planes, which was consistent with that of a pure cubic phase of the CoSe2 standard pattern (JCPDS#09–234) [55]. The peaks of CoSe2/CoMoO4 hybrid at 24.9°, 27.8°, 32.6°, 36.3°, 38.4°, 42.8°, 46.5° and 53.8° can be ascribed to CoMoO4 (PDF#21–0868), and the diffraction peaks of CoSe2/DETA presented a little shift, which further confirmed the CoSe2/DETA and CoMoO4 is coupled. The XRD pattern of S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 exhibited obvious peaks at 23.7°, 26.2°, 33.7°, 37.3°, 43.2°, 46.0°, 47.8°, 53.8°, and 56.7°, corresponding to the (021), (003), (220), (312), (015), (042), (125), and (051) planes (PDF#30–0450). The TEM images and elemental mapping images of S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 are presented in Fig. 2f. Some particles existed in the surface of sheet, which may be related to the incorporation of sulfur element. The elemental mapping further demonstrated the uniform distribution of Co, S, and Se. All these results revealed that S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 was successfully prepared via sulfuration, which is in accordance with the results of SEM and XPS.

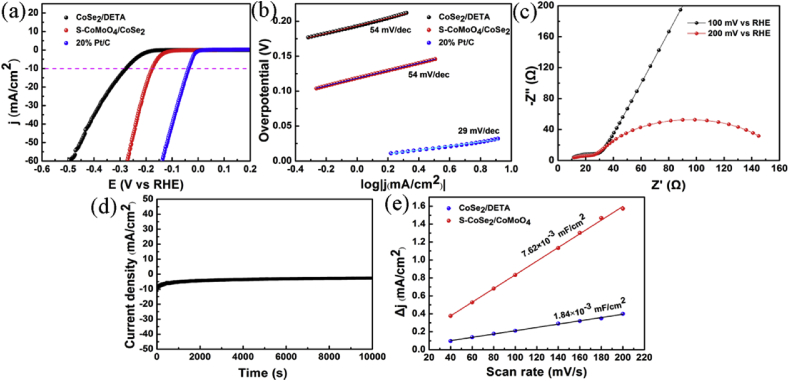

The HER catalytic activity of samples prepared with different molar ratios between Co and Mo were shown in Fig. S2. S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 (1:1) produces a current density (j) of 10 mA cm−2 at an overpotential (η) of 177 mV, while S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 (1:3) and S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 (3:1) need the overpotential of 182 and 180 mV, respectively. The Tafel slope is another important criterion to evaluate the performance of catalyst, which refers to the additional voltage required to increase the catalytic current density [56]. A smaller Tafel slope means a faster increase in the HER rate. The Tafel slope could be obtained by means of fitting the linear regions of Tafel plots according to the Tafel equation η = a+b log j (η is the overpotential, a is the Tafel constant, b is the Tafel slope, and j is the current density) [57].As depicted in Fig. 3b, S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 (1:1) shows a Tafel slope of 54 mV dec−1, which is slightly higher than that of S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 (1:3, 48 mV dec−1) and S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 (3:1, 42 mV dec−1). Three principal steps, including Volmer, Heyrovsky, and Tafel reactions with the corresponding Tafel slope of 120, 40, and 30 mV dec−1, have been proposed for the conversion of H+ to H2 in an acidic medium [58]. The Tafel slop of 42–54 mV dec−1 reveals that electrochemical desorption is the rate-limiting step and the HER process follows the Volmer-Heyrovsky mechanism. This process contains two steps, a discharge step that converted protons into hydrogen atoms adsorbed on the surface of catalyst, and the second step involved the formation of surface-bound hydrogen molecules [59,60]. Additionally, exchange current densities (j0) is another inherent measure of activity for HER for the catalyst, which can be acquired by applying extrapolation method to the Tafel plots. The exchange current density was calculated to be 6.27 × 10−3 mA cm−2, which is larger than those of S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 (1:3, 1.96 × 10−3 mA cm−2) and S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 (3:1, 8.30 × 10-4 mA cm-2), indicating the best catalytic efficiency of S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 (1:1).

Fig. 3.

Polarization curves (a) and Tafel slopes (b) of CoSe2/DETA, S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 and 20% Pt/C. Nyquist plots (c) and time-dependent current density curves of S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 (d). Linear fitting of the capacity currents of the catalysts versus scan rates (e).

As displayed in Fig. S3. S–Mo/CoSe2 shows the smallest Tafel slope of 41 mVdec-1, while it exhibits the higher overpotential of 199 mV and the lower exchange current density (1.68 × 10−4 mA cm−2) compared to that of S–CoSe2/CoMoO4. In addition, S–Co/CoSe2 presented the worst HER activity with the overpotential of 235 mV and the Tafel slope of 60 mV dec−1. The results demonstrated that there is a synergetic effect between Co and Mo in the S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 catalyst, resulting in the HER activity of S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 superior to those of each individual.

Electrochemical performance for S–CoSe2 and S–CoMoO4 catalysts are depicted in Fig. S4, compared with S–CoMoO4, S–CoSe2 presents inferior HER electrocatalytic activity with a lower overpotential of 203 mV at a current density of 10 mA cm−2 and a Tafel slope of 42 mV dec−1. HER performance of CoSe2/DETA and S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 can be observed in Fig. 3. S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 shows higher electrocatalytic activity than CoSe2/DETA. Such results suggested the excellent catalytic activity of S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 is connected to the strong couple between CoMoO4 and CoSe2/DETA, which is similar to the reported catalytic system of CoS2/CoSe2 [28]. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were conducted to investigate the charge-transfer mechanism of HER involved. The low charge-transfer resistance (Rct) that relates to a fast charge transfer at the interface between electrocatalyst and electrolyte, implies excellent electrocatalysis for the HER [61]. As presented in Fig. 3c, the solution resistance calculated is about 11.58 Ω and Rct decreases with the increase of overpotential, which is in agreement with the polarization curves of S–CoSe2/CoMoO4. Stability is another crucial parameter to evaluate the catalytic response of catalyst. The current density-time (i-t) test was performed at overpotential of 178 mV vs RHE for 10000 s (Fig. 3d), while the current density was found slightly decline, which may be due to the H2 bubbles gather on the electrode surface and result in a larger interface resistance [62]. The electrochemical double-layer capacitance (Cdl) between the catalysts and electrolyte was obtained by using the cyclic voltammetry (CV) method. CV curves was acquired in the potential range without a redox process from 0.173 to - 0.027 V vs RHE at a scan rates from 20 to 200 mV s−1 at 0.5 M H2SO4 (Fig. S5- Fig. S6). Based on the CV curves and the plots of the resultant current densities verus scan rates (Fig. 3e), S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 presents the highest Cdl, implying its high effective surface area and abundant active sites for the HER. Therefore, the comparison of electrocatalytic properties of different catalysts suggested that S doping and the interaction of CoMoO4 and CoSe2/DETA are in favor of the improvement of catalytic activity of catalysts.

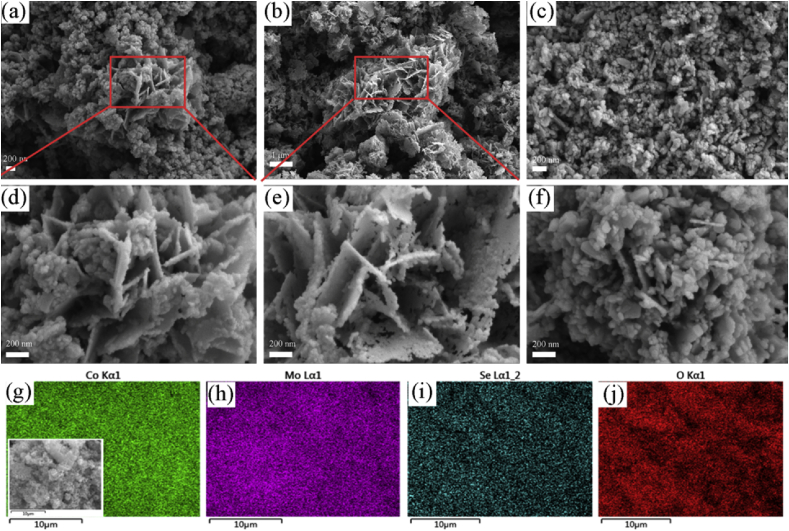

SEM images and EDX mapping of O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 prepared at different oxidization temperatures are displayed in Fig. 4. The obtained O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 exhibits partial sheet structures, and contains some aggregated particles (Fig. 4a–f). The void that existed in the sheet can efficiently boost the electron transport and provides enough void volume for releasing gas, and then enhances the catalytic activity of catalyst. Compared with the initial morphology of CoSe2/CoMoO4, the thickness of O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 is decreased and the surface is collapsed after oxidization, which may be due to the low thermal stability of CoSe2/CoMoO4. Furthermore, with the increase of oxidization temperature, most of sheet structures are transferred into the granular, leading to the decrease of available active sites. EDX mapping of O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 was conducted to confirm the presence of CoSe2/DETA (Fig. 4g–j), the elemental mappings of O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 demonstrate Co, Mo, Se and O are distributed uniformly. XRD patterns of O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 prepared at different oxidization temperatures are shown in Fig. S7. XRD pattern of the hybrid that contains the diffraction peak of CoMoO4 (PDF#21–0868) and Co3O4 (PDF#43–1003) can be observed after oxidization. Moreover, higher temperature leads to the enhancement of crystalline forms of Co3O4 and a decrease of the diffraction peak of CoMoO4, which may be related to the transformation occurred from CoMoO4 to metal oxides.

Fig. 4.

SEM images of O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 prepared at different oxidization temperatures, (a, b) 500 °C, (c, d) 600 °C, (e, f) 700 °C. EDX mapping of O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 prepared at 500 °C (g–j).

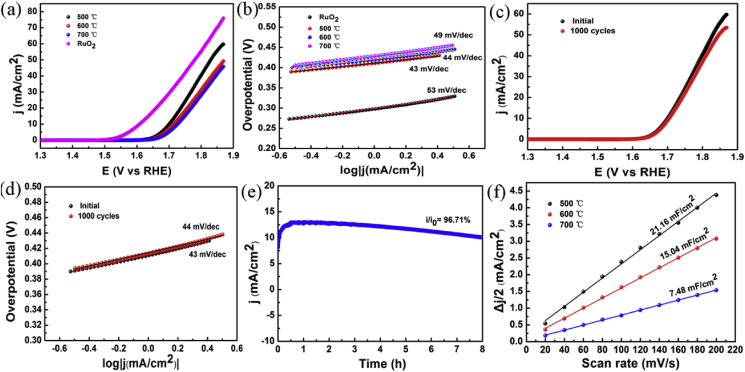

The electrocatalytic OER performance was first evaluated by polarization curves using RDE in O2-saturated 1.0 M KOH electrolyte. The influence of oxidization temperature on electrochemical activity of catalyst is shown in Fig. 5. RuO2 exhibits superior performance compared to O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 with a low overpotential (η) of 379 mV at the current density of 10 mA cm−2 with a Tafel slope of 53 mV dec−1. O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 (500 °C) (η = 471 mV) presents the optimal OER catalytic activity, which is better than that of O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 (600 °C) (η = 485 mV) and O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 (700 °C) (η = 497 mV) at j = 10 mA cm−2 (Fig. 5a). For O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 (500 °C), O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 (600 °C) and O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 (700 °C), the Tafel slopes are 43, 44 and 49 mV dec−1, which are significantly lower than commercial RuO2, suggesting the similar OER kinetics (Fig. 5b). The OER activity of O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 decreases with the increase of oxidization temperature, due to the disappearance of sheet-like structure and hole, leading to the decline of exposed active sites. Furthermore, according to the results of XRD, several phases existed in hybrid may restrain the utilization of efficient active sites.

Fig. 5.

LSV curves (a) and the corresponding Tafel plots (b) of O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 prepared at different oxidization temperatures. Polarization curves of initial and 1000 th cycles (c) and Tafel plots (d) of O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 prepared at 500 °C. The chronoamperometric curve (e). Capacitive current at 0.3 V (vs Ag/AgCl) as a function of scan rate for O–CoSe2/CoMoO4.

Besides such extraordinary catalytic activity, O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 also displays excellent stability toward the OER. As illustrated in Fig. 5c and d, the polarization curves of initial and 1000 th cycles are almost coincident. There is merely 4 mV positive shift at j = 10 mA cm−2 and negligible change of Tafel slopes after 1000 th cycles. High stability is great importance for energy conversion systems, the chronoamperometric method was adopted to further evaluate the stability of O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 at an overpotential of 0.64 V (vs Ag/AgCl). A high current retention of 96.71% can be observed in Fig. 5e, implying its outstanding durability in continuous oxygen evolution process. The high catalytic activity could be elucidated by ECSA of the materials, which can be calculated by measuring the CV curves at different scan rates (Figs. S8 ~ S10). As shown in Fig. 5f, the Cdl of O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 (500 °C, 21.16 mF cm−2) is much higher than those of O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 (600 °C, 15.04 mF cm−2) and O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 (700 °C, 7.48 mF cm−2), which was attributed to enhanced dispersion of nanosheet with fully exposed and easily accessible active sites. XPS characterization was further applied to reveal the existence of oxygen vacancies on the surface of O–CoSe2/CoMoO4. As can be seen from Fig. S11, Co, Mo, Se and O are homogeneously distributed among the whole hybrid samples. The deconvolutions of the O 1s spectra for O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 is obtained with the assumption of two species. The peak centered at 530.5 eV is associated with oxygen atoms bound to metals, and the peak at 531.7 eV is related to abundant defect sites with a low oxygen coordination [63]. It is believed that a number of oxygen vacancies in ultrathin nanosheets of O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 play important roles in promoting OER performance.

4. Conclusion

We have successfully fabricated the S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 and O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 hybrid composite as earth-abundant and high-performance catalysts for the HER and OER. The as-prepared S–CoSe2/CoMoO4 hybrid exhibits superior HER catalytic activity with a small of overpotential (177 mV) at the current density of 10 mA cm−2, and a small Tafel slope of 54 mV dec−1. In comparison with RuO2, O–CoSe2/CoMoO4 also displays excellent electrocatalytic activity toward OER, affording a current density of at an overpotential of 471 mV and a low Tafel slope of 43 mV dec−1, as well as negligible catalytic deactivation after 8 h operation. The excellent properties of the two hybrids may be due to four reasons: (1) CoSe2/DETA with partial activity could provide a substrate to support the generation of CoMoO4 nanosheet. (2) The excellent coupling between the CoSe2/DETA nanobelts and CoMoO4 nanosheet offers abundant active sites for the HER and OER. (3) S doping changes the electronic energy structures and enhances adsorption of H atoms on the catalysts, leading to the excellent HER activity of S–CoSe2/CoMoO4. (4) The formation of oxygen vacancies in the ultrathin nanosheets can significantly increase the number of active sites and facilitate adsorption of H2O, resulting in an increase in the OER catalytic activity.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank for the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31971614, 21736003), Guangdong Natural Science Funds for Distinguished Young Scholar (2016A030306027), Guangdong Natural Science Funds (2017A030313130), Guangzhou Science and Technology Funds (201904010078), State Key Laboratory of Pulp and Paper Engineering and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ese.2019.100004.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Feng J.X., Wu J.Q., Tong Y.X., Li G.R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:610–617. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b08521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang J.Q., Zhao Y.F., Guo X., Chen C., Dong C.L., Liu R.S., Han C.P., Li Y.D., Gogotsi Y., Wang G.X. Nat. Catal. 2018;1:985–992. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morales-Guio C.G., Hu X. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:2671–2681. doi: 10.1021/ar5002022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu W., Hu E., Jiang H., Xiang Y., Weng Z., Li M., Fan Q., Yu X., Altman E.I., Wang H. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10771–10779. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang J., Wang T., Liu P., Liao Z., Liu S., Zhuang X., Chen M., Zschech E., Feng X. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15437–15444. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang P.L., Li L., Nordlund D., Chen H., Fan L.Z., Zhang B.B., Sheng X., Daniel1 Q., Sun L.C. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:381–390. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02429-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang L., Si R.T., Liu H.S., Chen N., Wang Q., Adair K., Wang Z.Q., Chen J.T., Song Z.X., Li J.J., Banis M.N., Li R.Y., Sham T.K., Gu M., Liu L.M., Botton G.A., Sun X.L. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:4936–4946. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12887-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Z., Cui Y.R., Wu Z.W., Milligan C., Zhou L., Mitchell G., Xu B., Shi E.Z., Miller J.T., Ribeiro F.H., Wu Y. Nat Catal. 2018;1:349–355. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J.Y., Wang H., Tian Y., Yan Y., Xue Q., He T., Liu H., Wang C., Chen Y., Xia B.Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2018;57:7649–7653. doi: 10.1002/anie.201803543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu D.D., Liu J.L., Qiao S.Z. Adv. Mater. 2016;28:3423–3452. doi: 10.1002/adma.201504766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng Y., Jiao Y., Jaroniec M., Qiao S.Z. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:52–65. doi: 10.1002/anie.201407031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McAllister1 J., Bandeira N.A.G., McGlynn J.C., Ganin A.Y., Song Y.F., Bo C., Miras H.N. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:370–379. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-08208-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo Z.Y., Ouyang Y.X., Zhang H., Xiao M.L., Ge J.J., Jiang Z., Wang J.L., Tang D.M., Cao X.Z., Liu C.P., Xing W. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:2120–2127. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04501-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou Q., Chen Z., Zhong L., Li X., Sun R., Feng J., Wang G.C., Peng X. ChemSusChem. 2018;11:2828–2836. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201801044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu F., Zhou H.Q., Huang Y.F., Sun J.Y., Qin F., Bao J.M., Goddard W.A., Chen S., Ren Z.F. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:2551–2559. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04746-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y., Wei X.F., Chen L.S., Shi J.L., He M.Y. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:5335–5346. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13375-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song F.Z., Li W., Yang J.Q., Han G.Q., Liao P.L., Sun Y.J. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:4531–4540. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06728-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deng S., Yang F., Zhang Q., Zhong Y., Zeng Y., Lin S., Wang X., Lu X., Wang C.Z., Gu L., Xia X., Tu J. Adv. Mater. 2018;30:1802223–1802231. doi: 10.1002/adma.201802223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng Y.R., Wu P., Gao M.R., Zhang X.L., Gao F.Y., Ju H.X., Wu R., Gao Q., You R., Huang W.X., Liu S.J., Hu S.W., Zhu J.F., Li Z.Y., Yu S.H. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:2533–2541. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04954-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo1 Y.T., Tang L., Khan U., Yu Q.M., Cheng H.M., Zou X.L., Liu B.L. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:269–277. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07792-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qing Cao L.Z., Wang A.L., Yang L.J., Lai L.F., Wang Z.L., Kim J., Zhou W.J., Yamauchi Y., Lin J.J. Nanoscale. 2018;11:1700–1709. doi: 10.1039/c8nr07463a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X., Zhou Y., Liu M., Chen C., Zhang J. Electrochim. Acta. 2019;297:197–205. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen T., Li S., Wen J., Gui P., Guo Y., Guan C., Liu J., Fang G. Small. 2018;14:1700979–1700986. doi: 10.1002/smll.201700979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tabassum H., Zhi C., Hussain T., Qiu T., Aftab W., Zou R. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019;9:1901778–1901787. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng Y.R., Gao M.R., Gao Q., Li H.H., Xu J., Wu Z.Y., Yu S.H. Small. 2015;11:182–188. doi: 10.1002/smll.201401423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hussain S., Akbar K., Vikraman D., Liu H., Chun S.-H., Jung J. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2018;65:167–174. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang X., Zheng B., Wang B., Wang H., Sun B., He J., Zhang W., Chen Y. Electrochim. Acta. 2019;299:197–205. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo Y.X., Shang C.S., Wang E.K. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2017;5:2504–2507. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim J.K., Park G.D., Kim J.H., Park S.K., Kang Y.C. Small. 2017;13:1700068–1700077. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hongmei Li X.Q., Zhu Changli, Jiang Xiancai, Shao Li, Hou Linxi. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2017;5:4513–4526. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hui L., Xue Y.R., Huang B.L., Yu H.D., Zhang C., Zhang D.Y., Jia D.Z., Zhao Y.J., Li Y.J., Liu H.B., Li Y.L. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:5309–5319. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07790-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tiwari J.N., Sultan S., Myung C.W., Yoon T., Li N., Ha M., Harzandi A.M., Park H.J., Kim D.Y., Chandrasekaran S.S., Lee W.G., Vij V., Kang H., Shin T.J., Shin H.S., Lee G., Lee Z., Kim K.S. Nat Energy. 2018;3:773–782. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li H.Y., Chen S.M., Zhang Y., Zhang4 Q.H., Jia X.F., Zhang Q., Gu L., Sun X.M., Song L., Wang X. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:2452–2463. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04888-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou G., Shan Y., Wang L.L., Hu Y.Y., Guo J.H., Hu F.R., Shen J.C., Gu Y., Cui J.T., Liu L.Z., Wu X.L. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:399–406. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08358-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao X., Zhang H., Yan Y., Cao J., Li X., Zhou S., Peng Z., Zeng J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2017;56:328–332. doi: 10.1002/anie.201609080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Faber M.S., Dziedzic R., Lukowski M.A., Kaiser N.S., Ding Q., Jin S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:10053–10061. doi: 10.1021/ja504099w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Y., Zhong C., Liu J., Zeng X., Qu S., Han X., Deng Y., Hu W., Lu J. Adv. Mater. 2018;30:1700355–1700361. doi: 10.1002/adma.201703657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang Y.C., Sun Y.H., Zheng X.L., Aoki T., Pattengale B., Huang J., He X., Bian W., Younan S., Williams N., Hu J., Ge J.X., Pu N., Yan X.X., Pan X.Q., Zhang L.J., Wei Y.G., Gu J. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:982–992. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08877-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masa J., Weide P., Peeters D., Sinev I., Xia W., Sun Z., Somsen C., Muhler M., Schuhmann W. Adv. Energy Mater. 2016;6:1502313. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu W.S., Wu Z.L., Foo G.S., Gao X., Zhou M.X., Liu B., Veith G.M., Wu P.W., Browning K.L., Lee H.N., Li H.M., Dai S., Zhu H.Y. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15291–15297. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang R., Zhou Y., Xing Y., Li D., Jiang D., Chen M., Shi W., Yuan S. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019;253:131–139. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ang H., Tan H.T., Luo Z.M., Zhang Y., Guo Y.Y., Guo G., Zhang H., Yan Q. Small. 2015;11:6278–6284. doi: 10.1002/smll.201502106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu Y.S., Liu X.J., Han D.D., Song X.Y., Shi L., Song Y., Niu S.W., Xie Y.F., Cai J.Y., Wu S.Y., Kang J., Zhou J.B., Chen Z.Y., Zheng X.S., Xiao X.H., Wang G.M. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1425–1433. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03858-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ling T., Yan D.Y., Wang H., Jiao Y., Hu Z.P., Zheng Y., Zheng L.R., Mao J., Liu H., Du X.W., Jaroniec M., Qiao S.Z. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1509–1515. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01872-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gao M.R., Xu Y.F., Jiang J., Zheng Y.R., Yu S.H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:2930–2933. doi: 10.1021/ja211526y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gao G., Wu H.B., Lou X.W.D. Adv. Energy Mater. 2014;4:1400422. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sivanantham A., Ganesan P., Shanmugam S. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016;26:4661–4672. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao Q.H., Fu L.J., Jiang D.H., Ouyang J., Hu Y.H., Yang H.M., Xi Y.F. Nat. Commun. 2019;2:11–20. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang J., Cui W., Liu Q., Xing Z., Asiri A.M., Sun X. Adv. Mater. 2016;28:215–230. doi: 10.1002/adma.201502696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang W., Qin J., Yin Z., Cao M. ACS Nano. 2016;10:10106–10116. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b05150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yan H., Xie Y., Jiao Y., Wu A., Tian C., Zhang X., Wang L., Fu H. Adv. Mater. 2018;30:1704156–1704163. doi: 10.1002/adma.201704156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li Y., Li F.-M., Meng X.-Y., Li S.-N., Zeng J.-H., Chen Y. ACS Catal. 2018;8:1913–1920. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang X., He J., Yu B., Sun B., Yang D., Zhang X., Zhang Q., Zhang W., Gu L., Chen Y. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019;258:117996. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ma L., Hu Y., Chen R., Zhu G., Chen T., Lv H., Wang Y., Liang J., Liu H., Yan C., Zhu H., Tie Z., Jin Z., Liu J. Nano Energy. 2016;24:139–147. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu Y.F., Gao M.R., Zheng Y.R., Jiang J., Yu S.H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2013;52:8546–8550. doi: 10.1002/anie.201303495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Park J.L.S.K., Hwang T., Piao Y. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2016;4:12720–12725. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li J.S., Wang Y., Liu C.H., Li S.L., Wang Y.G., Dong L.Z., Dai Z.H., Li Y.F., Lan Y.Q. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11204–11211. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.He B., Chen L., Jing M., Zhou M., Hou Z., Chen X. Electrochim. Acta. 2018;283:357–365. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang P.T., Zhang X., Zhang J., Wan S., Guo S.J., Lu G., Yao J.L., Huang X.Q. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14580–14588. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu J., Cui J., Guo C., Zhao Z., Jiang R., Xu S., Zhuang Z., Huang Y., Wang L., Li Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2016;55:6502–6505. doi: 10.1002/anie.201600686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang H., Jin Z., Hu H., Bi Y., Lu G. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018;427:587–597. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhou W., Zhou J., Zhou Y., Lu J., Zhou K., Yang L., Tang Z., Li L., Chen S. Chem. Mater. 2015;27:2026–2032. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zeng Y., Lai Z., Han Y., Zhang H., Xie S., Lu X. Adv. Mater. 2018;30:1802396–1802403. doi: 10.1002/adma.201802396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.