Abstract

Chronic cough is defined in adults as a cough that lasts for ≥8 weeks. When it proves intractable to standard-of-care treatment, it can be referred to as refractory chronic cough (RCC). Chronic cough is now understood to be a condition of neural dysregulation. Chronic cough and RCC result in a serious, often unrecognized, disease burden, which forms the focus of the current review.

The estimated global prevalence of chronic cough is 2–18%. Patients with chronic cough and RCC report many physical and psychological effects, which impair their quality of life. Chronic cough also has a significant economic burden for the patient and healthcare systems. RCC diagnosis and treatment are often delayed for many years as potential treatable triggers must be excluded first and a stepwise empirical therapeutic regimen is recommended.

Evidence supporting most currently recommended treatments is limited. Many treatments do not address the underlying pathology, are used off-label, have limited efficacy and produce significant side-effects. There is therefore a significant unmet need for alternative therapies for RCC that target the underlying disease mechanisms. Early clinical data suggest that antagonists of the purinergic P2X3 receptor, an important mediator of RCC, are promising, though more evidence is needed.

Short abstract

Chronic cough exerts a considerable burden on patients and healthcare systems. In addition to effective targeted therapies, further data are needed to understand the pathophysiology, epidemiology and disease burden. https://bit.ly/3Be9JZI

Introduction

Under normal circumstances, cough is a protective reflex preventing aspiration, but in some individuals, it can become prolonged, excessive and debilitating [1]. Generally accepted definitions of cough in adults in terms of duration are acute (≤3 weeks), subacute (between 3 and 8 weeks) and chronic (>8 weeks) [1]. The terms refractory chronic cough (RCC) or unexplained chronic cough (UCC) were used to define patients entering clinical trials. Whether they represent different subgroups of patients whose cough is considered either refractory to conventional treatments [2] or remains unexplained following assessment [3] is controversial. There was no difference in symptom profile, assessed with the Hull Airway Reflux Questionnaire (HARQ), between patients classified as having RCC or UCC in a rigorously defined population of patients in a recent clinical trial [4]. Regardless of how it is termed, chronic cough is associated with a serious disease burden and there is an unmet need for better treatments. While chronic cough has previously been regarded as a persistent symptom of other underlying conditions, recent advances in our understanding suggest it is a distinct condition with characteristic pathophysiology which can be targeted by new treatments [5].

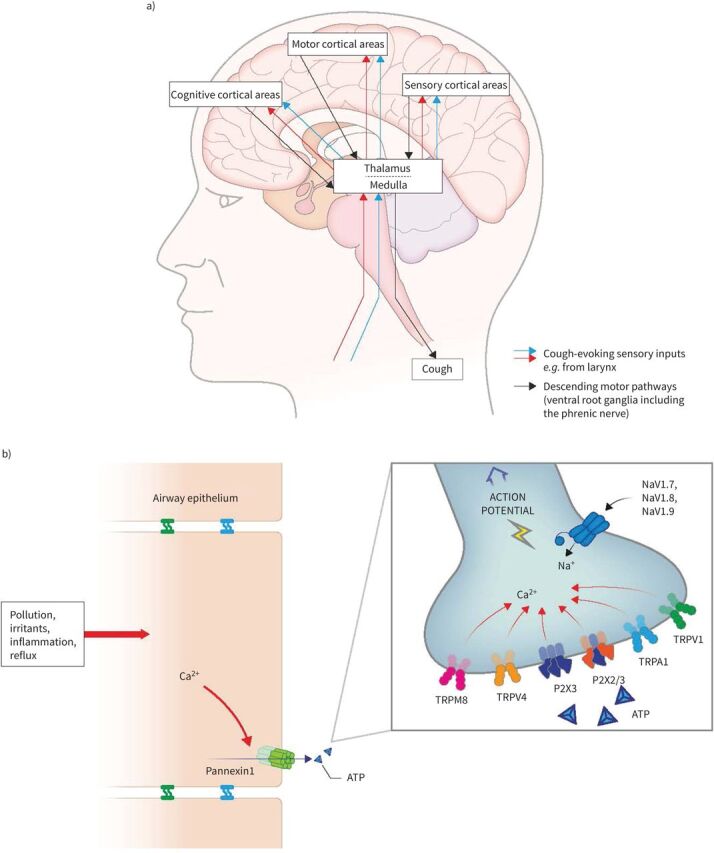

Involuntary cough is a reflex activated by sensory nerves from the territory of the vagal afferents [6]. In response to detection of potentially noxious stimuli by airway sensory nociceptors, impulses travel up the vagus nerve via the nodose and jugular ganglia to the medulla, where they are modulated by central pathways. A signal is then sent through somatic efferents to the larynx, respiratory muscles and diaphragm to result in a cough [6–8]. Chronic cough is often triggered by low levels of thermal, mechanical or chemical exposure [2, 9], reflecting a common aetiology, known as cough hypersensitivity syndrome (CHS) [10]. CHS is characterized by dysregulation of neural pathways and receptors in the central nervous system, vagal afferent sensory nerves, and ganglia [5, 9–12] (figure 1 [5, 13]), as demonstrated by the observation that many antitussive drugs have neuromodulatory properties [1, 2, 14].

FIGURE 1.

a) Ascending and descending neural pathways involved in the cough reflex. b) Stimulation and activation of airway sensory neurons. Essentially, noxious stimuli or inflammation cause an increase in intracellular calcium which opens the pannexin channel and releases ATP to activate P2X3 channels on sensory nerves. This leads to cell depolarisation potentially triggering the opening of NaVs and generating an action potential which is carried through the vagus nerve to the central nervous system. Mechanisms for the cough reflex still have to be fully established in humans; many other pathways and receptors are probably involved. Ca2+: calcium; NaV: voltage-gated sodium channel; Na+: sodium; TRPA: transient receptor potential ankyrin; TRPM: transient receptor potential melastatin; TRPV: transient receptor potential vanilloid. Reproduced and modified from [5, 13].

CHS is an umbrella term encompassing multiple complex multifactorial processes and different cough phenotypes or traits [5, 15–17]. Traditionally, it was believed that chronic cough arose from acute cough associated with respiratory viral infections, from clinically diagnosed diseases such as asthma or gastro–oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), oesophageal dysmotility or, more controversially, from a poorly defined condition referred to as post-nasal drip syndrome or upper airways cough syndrome [2, 5, 16–19]. Additionally, certain drugs such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors can increase cough sensitivity [20]. These conditions, however, fail to capture the complex heterogeneity of presentation of these airway diseases in the clinic and there has been a move in recent years to think in terms of treatable traits when managing patients with chronic airway diseases [21]. Notably, sensitivity in the neural pathways responsible for eliciting cough appears to be a consistent feature of patients with chronic cough, regardless of the overall clinical presentation [5]. CHS therefore represents a specific disease state that can be targeted by therapeutic interventions. In the context of chronic cough, therefore, CHS represents a significant treatment target [9].

This review summarises the epidemiology of chronic cough and the burden it imposes on patients and healthcare systems. It presents an overview of our current understanding of patient burden and the important role of patient report-based measures in capturing this. It also highlights gaps in current treatment and describes emerging treatment options designed to target the underlying CHS.

Epidemiology

Cough is the most common presenting symptom in adults who seek medical treatment in non-hospital settings [22]. However, conclusions from epidemiological studies aimed at establishing the prevalence of chronic cough or RCC vary widely and reflect differences in study design, definitions of patient population, disease, conventional treatments and refractory status. The prevalence of RCC may be overestimated if patients are designated “refractory” because of a poor response to therapies that do not actually address the underlying pathology of the cough. Conversely, it may be under-reported or underestimated if the cough is regarded as a complication of another condition rather than as a distinct entity. This is demonstrated in a 1-year retrospective study of primary care data from approximately 200 000 patients in England, in which 18% of patients presented at least once with a cough-related condition, but only 0.2% were explicitly diagnosed with chronic cough [23]. Repeated presentation with “chest infections” was, however, common [23].

The global prevalence of self-reported chronic cough in adults has been estimated from a meta-analysis to be approximately 10% [24] with regional variations of 2% in Africa to 18% in Oceania [24]. In respiratory outpatient practice, it ranges from 10% to 38% [25]. In addition to differences in study designs or disease definitions, these differences in prevalence are likely to be driven by environmental and socioeconomic factors, such as levels of obesity or smoking [24]. Unlike chronic cough, prevalence data for RCC are very limited, although one study showed that 42% of patients referred to a UK chronic cough clinic (n=100) were diagnosed with RCC [26].

The population of patients with chronic cough is predominantly middle-aged, though there are some regional differences. In a survey conducted in the UK, the Netherlands, Sweden, South Korea, China and the USA (n=10 032), the most common age for presentation overall was 60–69 years, while a lower age (30–39 years) was observed in China [27]. Other studies have confirmed the early onset of chronic cough in China, with most patients presenting in their late thirties or early forties [28]. Age is a risk factor for chronic cough, as demonstrated in a Finnish community study (n=3697), which reported an adjusted odds ratio per decade for age of 1.15 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.05–1.26; p<0.01) [29].

Chronic cough is more prevalent in females than males, with studies reporting 66–73% of patients to be female [27, 30]. This mirrors similar findings for chronic pain, and comorbid daily chronic pain and chronic cough, which are also more prevalent in women than in men [31], possibly due to shared neural pathways. Data from a functional magnetic resonance imaging study, involving inhalation of subtussive concentrations of capsaicin, suggest these gender prevalence effects may reflect differences in central neural processing of the cough sensation [27]. Interestingly, boys and girls have a similar cough reflex sensitivity, and this gender difference appears during puberty [32]. It can be speculated that women have evolved a heightened cough reflex to protect themselves against aspiration during pregnancy.

Gender and age effects are likely to be modulated by environmental or social influences. In some countries, such as South Korea [33] and China [28], chronic cough is more prevalent in males, with a study of chronic cough in the general population of South Korea (n=18 071) reporting a prevalence of 3% in males compared with 2% in females (p<0.001) [33]. The authors attributed this to differences in smoking habits. A study in China of 1882 patients with chronic cough, of whom 87% had never smoked, found that they tended to be younger (43 years) than is typically observed in Western countries, with no observable gender differences [34]. The authors speculated that the different characteristics of their patient population reflected the levels of air pollution to which their patients were exposed.

Chronic cough can persist for many years [35]. In a cross-sectional European survey (n=1120), 20% of patients reported a cough duration of ≥10 years [36] and approximately 10% of patients reported a cough duration of ≥30 years in a questionnaire-based survey in the UK (n=373) [30]. A study in Finland (n=421) found that 57% and 26% of patients still had chronic cough 1 and 5 years, respectively, after their first assessment [37], with symptoms of peptic gastro–oesophageal reflux being the main predictor of persistence at 1 year (n=165) [38]. Of the patients with symptoms of peptic gastro–oesophageal reflux, 63% had received treatment with proton pump inhibitors. A longitudinal study of unexplained chronic cough in the UK over 7–10 years (n=42) also demonstrated that not only does cough persist, with cough severity unchanged in 24% of patients, but there was an increase in severity over time in 36% of patients. Unexpectedly, patients with longitudinal spirometry data were also found to have declines in forced expiratory volumes over 1 s that were well above what would be expected in a population of non-smoking patients of the same age [39].

Physical effects of chronic cough

Cough is typically assessed in terms of frequency using electronic cough monitors [40, 41] and in terms of severity with a visual analogue scale. Monitors assess cough frequency (typically expressed as coughs per hour measured over a 24 h period), but do not capture the episodic nature of chronic cough – a primary factor in the disease burden experienced by patients. Typically, higher cough rates are observed during the day, with recent clinical trials in patients with RCC recording mean rates of 37–65 coughs per hour during the day (awake) and 4–10 coughs per hour during sleep at baseline [42, 43]. Cough frequencies in excess of 700 per hour have been reported [44].

In addition to the physical act of coughing, patients report numerous physical and/or psychosocial effects associated with cough [45]. These commonly include breathlessness, wheezing, fatigue, exhaustion, sleep disturbance, impairment of speech, retching, vomiting and interference with daily activities [2, 30, 45, 46], as well as urinary incontinence. This last symptom is most common in women, with 55–66% of women versus only 5% of men reporting it as an issue with a significant impact on their quality of life (QoL) [2, 30, 47, 48]. If the cough is sufficiently severe, it can generate very high intra-abdominal and intrathoracic pressures, producing chest pain and, less commonly, rib fractures and hernias [46]. Around 10% of patients [30], almost exclusively male, develop cough syncope [49], sometimes with fatal consequences, and the mandatory driving licence loss has a major impact on employment prospects [50].

Misdiagnosis of the underlying cause of the cough also adds to patient burden since patients are unnecessarily exposed to inappropriate investigations or ineffective treatments. For example, cough is often reported as the most troublesome symptom in patients where CHS co-exists with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and oral corticosteroids may be escalated to treat the presumed asthma symptoms [5] with little impact on the chronic cough, but an increased risk of serious side-effects [51, 52]. More generally, antibiotics are also often prescribed to treat cough. In a recent UK survey (n=198 151), 43% of adult patients with probable chronic cough (n=1600) and 55% of patients with possible chronic cough (n=10 913) were prescribed an antibiotic on the index date of the study [23]. Such indiscriminate use of these medications not only has consequences for healthcare costs, but it also represents a risk to the patient in potential adverse events (AEs) as well as contributing to increased antibiotic resistance within the community.

A number of conditions, including irritable bowel syndrome [2], obstructive sleep apnoea [2], obesity [33, 53], thyroid disease [54], neuropathic syndromes [2], GORD [44], asthma [44] and allergic rhinitis [44], are common in patients with chronic cough, contributing to the disease burden.

Psychological effects of chronic cough

A high prevalence of psychological effects is associated with chronic cough and the impact on mental health has been reported to be comparable to that of stroke or Parkinson's disease [55]. In a US observational study of patients with chronic cough (n=136), the most frequent patient-reported problems were frustration, anger and anxiety [56]. A UK study assessing psychological profiles of patients with chronic cough (n=67 (explained cough, n=42; RCC, n=25)) versus 22 healthy participants without cough symptoms reported that RCC patients had significantly higher levels of anxiety, depression, fatigue and somatic physical symptoms than non-cough participants [57]. They also had higher depression and fatigue scores and significantly more negative illness representations than patients with explained cough [57]. Clinical levels of anxiety were more common in patients with RCC (52%) than patients with explained cough (38%) [57]. Anxiety and depression have been reported in 33–52% and 16–91% of patients with chronic cough, respectively [36, 57–59]. A UK-based study reported higher levels of emotional distress including anxiety (48% of cough patients) and psychoneurotic symptoms than would be expected in a healthy population [59]. One reason for this anxiety, as highlighted in a US study (n=39), is a fear that the chronic cough represents serious disease [45].

Gender-related differences in psychological effects have also been noted. In a European survey (n=1120), a significantly higher proportion of women than men reported feeling fed up or depressed (difference in proportion: 5% (95% CI 0–9%)) as well as experiencing more limitations on their activities (difference in proportion: 10% (95% CI 4–16%)) due to their cough [36].

Effects of chronic cough on QoL

Reflecting the frequency and the severity of bouts of coughing, chronic cough can have a serious negative impact on patients’ QoL. Indeed, the impact on QoL is reported to be similar to that of other respiratory diseases including COPD, asthma and bronchiectasis [45, 60]. This effect remains even after factoring out contributions from comorbid asthma and COPD, or other independent confounding variables such as depression or arthritis [61].

The psychological and physical impacts of chronic cough interfere with all aspects of patients’ lives, including daily living activities, social interactions, home management and recreational activities [30, 36]. Importantly, patients may experience cough in response to trivial triggers, such as odours, changes in air temperature, fatigue/stress or talking [62, 63], that are very difficult to avoid. As a result, chronic cough can have a substantial psychosocial impact, with the potential for reduced work productivity and even job loss [37, 61, 64]. In a multinational European survey (n=1120), 96% of patients reported that their cough affected their QoL, 94% that it disturbed or worried their family and friends, and 81% that it affected activities they liked to do [36]. QoL in women seems to be particularly affected by chronic cough. They tend to score higher than men on the Cough-specific QoL Questionnaire (CQLQ), possibly because they are more likely to be affected by incontinence with psychosocial consequences due to embarrassment [65]. They may also have a lower pain threshold which possibly indicates higher pain sensitivity [66]. Data from a Korean population (n=30 021), based on the EuroQoL five-dimension three-level component index score, further suggest that women aged ≥65 years with chronic cough are particularly impacted versus a similar group without chronic cough (0.55±0.04 versus 0.70±0.01, p<0.001) [61]. Patients may avoid or be uncomfortable in social situations due to the embarrassment of coughing or its effects (e.g. urinary incontinence, retching, vomiting) and/or the perception by others that they have a contagious condition (particularly epidemics associated with respiratory diseases) or are a heavy smoker [46]. This was demonstrated in a UK survey (n=373) in which 64% of patients felt that their cough interfered with their social life [30].

Chronic cough also has a negative impact on personal relationships, with “spouses not being able to tolerate the cough” stated as one of the key reasons for patients’ health-related dysfunction in a US observational study (n=39) [45]. The effect of chronic cough on QoL is not necessarily limited to the frequency or severity of the cough. Despite only occasional paroxysms of coughing, it may still seriously impact a patient's QoL if they experience effects such as cough-related double incontinence or life-threatening cough syncope [67].

Economic burden

Though little studied to date, chronic cough is likely to have a significant economic burden as a consequence of impacts on job productivity, including time missed from work and absenteeism to provide care to others [68, 69]. For example, in a Finnish survey (n=421), 16% of patients with chronic cough had ≥7 sick days and 20% had ≥3 doctor's visits due to cough within 12 months [37]. Further direct costs include physician fees or consultation costs, diagnostic tests and prescription or over-the-counter drug costs. These costs may be unaffordable for many patients, particularly in low-income countries [70].

Costs for treating cough are compounded by poor general understanding of chronic cough and RCC, and multiple unnecessary and often unhelpful investigations. In a community-based questionnaire survey about chronic cough (n=373), 91% of respondents had seen a general practitioner for their cough, while 61% had been referred to hospital specialists and only 40% had been successfully treated [30]. Furthermore, some investigations involving tools such as computerized tomography are unlikely to be informative about chronic cough, but the increased exposure to radiation increases the risk of AEs or cancers, particularly breast cancer, in a population of patients which predominantly comprises middle-aged women [2].

Diagnosis

The patient's journey to diagnosis of RCC is often protracted due to several limiting factors, further impacting the patient burden. Several respiratory societies have published guidelines for the diagnosis and management of cough, but they vary in the terminology and definitions of RCC [2, 3, 68, 71]. Generally, guidelines recommend a comprehensive clinical history [72], physical examination and focused diagnostic testing, followed by a stepwise empirical therapeutic regimen [2]. Initial investigations are designed to detect or exclude treatable causes or serious underlying disorders [2, 22, 25]. Once obvious causes for the cough have been excluded, clinicians can focus on understanding the impact of the cough on the patient and the options for management. Not surprisingly, treatment can be substantially delayed due to this prolonged diagnostic testing, with too many tests and physician visits and poor access to specialist cough centres. In one study of patients in tertiary care (n=136), the median duration of cough was 18 months, with the mean exceeding 4.5 years [56]. Patients complained about frequent physician visits and testing. This frustration can be further compounded if an explanation for the cause of their cough is not established. These findings highlight the need to consider patient satisfaction in patient management guidelines.

Assessing the impact of chronic cough in the clinic typically relies on the use of standard instruments for the assessment of other respiratory conditions such as asthma [2, 73]. However, these only consider cough as a symptom, and the possibility that the cough represents a distinct condition (CHS) is frequently overlooked, particularly in primary care [23]. These instruments also fail to capture some of the key issues impacting patients with unexplained cough, such as anger and frustration over the ineffectiveness of therapies and the perception of helplessness [56].

Patient report-based outcome (PRO) measures play a vital role in supporting assessment in clinical studies. They capture many issues that cannot be assessed effectively by objective measures as well as being cheap, readily available to all clinics, and convenient and easy to use for the patient, unlike objective measures of cough frequency. A number of PROs have been designed to capture different aspects of interest for the clinician (table 1 [74–98]).

TABLE 1.

Patient report-based outcome (PRO) to assess disease burden or treatment efficacy in adults with chronic cough

| HRQoL tools | ||||

| Name | Domains/items | Rating | MCID | Comments |

| LCQ [74] | 19 items over three domains: physical; psychological; social. | Seven-point Likert scale (1=all of the time; 7=none of the time). | 1.5–2.5 [75, 76, 77] | Developed and validated in chronic cough [74]. Used to assess treatment efficacy in clinical trials [78–81]. Recommended in guidelines [82]. Well validated [77]. MCID defined [76, 77]. Translations are available in 60 languages, including a range of European languages, Thai [83], Mandarin Chinese [84] and Korean [85]. |

| CQLQ score [86] | 28 items over six domains: physical complaints; extreme physical complaints; psychosocial issues; emotional wellbeing; personal safety fears; functional abilities. | Four-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree; 4=strongly agree). | 10.6 [87] 10.6–21.9 [77, 82] |

Developed and validated in chronic cough [86]. Used to assess treatment efficacy in clinical trials [88, 89]. Recommended in guidelines [82]. Well validated [77]. MCID defined [77]. |

| ACOS [45] | 29 items over two domains (physical; psychosocial). | Yes or no. | 10.6–21.9 [82] | Superseded by CQLQ [82]. |

| CSS [90] | Two items: cough severity in daytime and night-time. | Six-point scale (0=no symptoms; 5=most severe). | Little clinical experience [77]. MCID not defined [77]. Has been translated into Korean [91]. |

|

| CSD [92] | Seven items: frequency (three items); intensity (two items); disruptiveness (two items). | 11-point scale (0=never; 10=constantly). | ≥1.3 CSD (total score) −1.4 to −1.1 (domain scores) [93] |

Developed in response to patient feedback [92]. Validated and MCID defined [93]. Widely used in clinical trials. |

| HARQ [94] | 14 items covering major components of chronic cough | Six-point scale (0=no symptoms; 5=most severe) | 16 [94] | Designed as a diagnostic test for chronic cough based on the symptoms of airway reflux [94]. High sensitivity and specificity [94]. Used in clinical trials [95, 96]. Translations are available in over 20 languages, including Mandarin Chinese [97] and Swedish [98]. Available for download at https://issc.info/ |

ACOS: Adverse Cough Outcome Survey; CQLQ: Cough-specific QoL Questionnaire; CSD: Cough Severity Diary; CSS: Cough Symptom Score; HARQ: Hull Airway Reflux Questionnaire; HRQoL: health-related quality of life; LCQ: Leicester Cough Questionnaire; MCID: minimal clinically important difference; RCC: refractory chronic cough. Adapted from [77].

The simplest method for gauging cough severity is to ask the patient to score their cough out of 10. Patient diaries including the Cough Severity Diary [92] and more recently the Severity of Chronic Cough Diary [99] have been developed to capture the severity and impact of cough and potentially to define endpoints for clinical trials [99].

The HARQ was specifically developed to codify the symptom complex in chronic cough, assessing diagnostic components of the history [94]. It has since been used to assess patients with unexplained respiratory symptoms [18] and to support the diagnosis of chronic cough in patients participating in clinical trials [95, 96]. For, example, in COUGH-1 and COUGH-2, the HARQ score was elevated in 95% of over 2000 rigorously identified patients with chronic cough [4].

A number of health-related QoL (HRQoL) tools are available for assessing the impact of chronic cough on QoL (table 1). The most commonly used tools are the Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ) [74–76, 83–85] and the CQLQ [77, 86, 87], which have been used in numerous clinical trials [78–81, 88, 89] and are recommended by guidelines [2, 82]. HRQoL tools and PROs targeting symptoms, severity and impact of CHS will help to streamline the diagnostic pathway.

One way to improve the individualised management of cough is to move away from rigid definitions of airway disease and consider cough in terms of treatable traits [5, 21, 100]. It is important to diagnose the mechanism driving CHS in each patient and find validated methods to identify patients likely to respond. Predictors of response identified to date include eosinophilic airway inflammation as a predictor of corticosteroid response or elevated oesophageal acid as a marker of GORD-related cough and potential benefit of proton pump inhibitors [5, 100]. Higher baseline cough frequency may predict the response to P2X3 receptor antagonists [43], although further research is needed to identify predictors of the efficacy of these agents. Comprehensive understanding of the relationship between biological mechanisms (endotypes) and observed clinical features (phenotypes) is necessary if precision medicine is to become a reality for treatable traits [21, 100].

Current treatments for chronic cough

A range of treatments is currently recommended for managing chronic cough (table 2 [101–111]). The drugs with the strongest level of recommendation in European Respiratory Society (ERS) guidelines are neuromodulators including low-dose morphine [78], gabapentin [96, 80], pregabalin [81] and amitriptyline [112]. Identifying the correct treatment can be challenging, since it is often not clear which phenotype of cough should be treated and patients can vary greatly in responsiveness [2]. Moreover, many of the recommended treatments are used off-label, evidence for efficacy is limited or weak, and with the exception of non-pharmacological treatments [101, 102], they can produce AEs [103–105, 106–109]. The ERS guidelines thus recommend that treatments be given as short-term trials (generally 1–2 weeks for opiates and 2–4 weeks for other drugs) and either discontinued where there is no response or continued for a couple of months until the cough subsides [2]. While rational in the context of available treatments, this strategy can be lengthy.

TABLE 2.

Summary of current treatments recommended by the European Respiratory Society [2]

| Treatment | Evidence of efficacy/treatment recommendations | Side-effects |

| Non-pharmacological cough control therapy, such as physiotherapy and speech therapy | Few studies of non-pharmacological therapies. Physiotherapy/speech and language (2 months) [101]: reduced subjective cough score compared with placebo treatment (MD 2.8 points; 95% CI 1.3–4.0). Physiotherapy/speech and language (weekly for 4 weeks) [102]: improved LCQ (+1.53 points; 95% CI 0.21–2.85); reduced cough frequency per hour (fold change, 0.59; 95% CI 0.36–0.95); no significant effect on VAS severity or QoL outcomes. |

None. |

| Non-opioid and non-anaesthetic antitussives | Evidence is limited and of variable quality [2, 3, 25]. | Vary depending on the treatment used: see literature for details. |

| ICS and antileukotrienes | Evidence supporting the use of ICS or antileukotrienes is weak [2]. Available trial data are affected by incomplete assessments of asthma, allergy and non-asthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis [3]. ERS recommends a short trial (2–4 weeks). |

Sore and dry throats (ICS) [103]. Headache, gastrointestinal disturbances, increased mucus production [104]; neuropsychiatric events (antileukotrienes) [105]. |

| ICS and an LABA | Moderate evidence supporting use in patients with fixed airway obstruction. Salmeterol+fluticasone twice daily [106]: improved cough severity score compared with placebo (scale: 0–4) (MD −0.09; 95% CI −0.17, −0.01). Short-term trials of 2–4 weeks are recommended. |

Sore and dry throat (ICS) [103], muscle cramps and muscle twisting (LABA) [103], potential risk of pneumonia with fluticasone in patients comorbid with COPD [107]. |

| Macrolides, e.g. azithromycin | Limited evidence for routine use. Can be considered if chronic bronchitis refractory to other therapy for a 4-week trial [2]. COPD GOLD stage ≥2 and chronic productive cough [108]: improved cough-specific QoL (LCQ; MD 1.3; 95% CI 0.3–2.3; p=0.01). |

Nausea, diarrhoea, headaches or changes to sense of taste [109]. |

| Opioids | In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study, slow-release morphine sulphate, 5 mg twice daily, improved the LCQ score by 3.2 points (p<0.01 versus baseline; p<0.02 versus placebo) and reduced cough severity recorded in a daily cough diary (p<0.01 versus baseline) [78]. | Constipation, drowsiness, risk of dependency [2, 3, 110]. |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | In a small case series, 72% of patients responded to treatment, as determined by subjective physician assessment of percentage improvement in cough symptoms [111]. | Sedation, dry mouth, anxiety [111]. |

| Gabapentin | Significant improvement in LCQ versus placebo in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Mean between-group difference: 1.80 (95% CI 0.56–3.04; p=0.004) [80]. Reduction in cough frequency versus placebo (1 h of observation). Mean between-group difference: −27.3% (95% CI −51.8 to −2.9; p=0.028) [80]. Reduction in cough severity versus placebo. Mean difference on VAS: −12.23 points (95% CI −23.2 to −1.3; p=0.029) [80]. |

Confusion, dizziness, dry mouth, fatigue, nausea, blurred vision, cognitive changes [2, 3]. |

| Pregabalin | Improvement in LCQ versus placebo in a randomized, controlled trial (both arms received speech pathology therapy). Mean difference: 3.5 points (95% CI 1.1–5.8; p=0.024) [81]. Improvement in cough severity. Mean difference on VAS: 25.1 (95% CI 10.6–39.6; p=0.002) [81]. |

Dizziness, fatigue, cognitive changes, nausea, blurred vision [2]. |

CI: confidence interval; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ERS: European Respiratory Society; GOLD: Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; ICS: inhaled corticosteroids; LABA: long-acting bronchodilator; LCQ: Leicester Cough Questionnaire; MD: mean difference; QoL: quality of life; VAS: visual analogue scale.

Treatments for RCC under investigation

The unsatisfactory efficacy of many current treatments is illustrated by a Europe-wide survey (n=1120), in which limited or no effectiveness was reported by 57% and 32% of subjects, respectively [36]. This reflects the fact that available treatments fail to target the underlying cough phenotypes [2]. New classes of treatment are, however, beginning to emerge.

The hypothesis that ATP is a neurotransmitter acting via specific purinergic receptors was first proposed by Geoffrey Burnstock in the 1970s [113, 114]. Subsequent research demonstrated that ATP is a co-transmitter in all peripheral and central nerves, leading to the investigation of purinergic receptor antagonists in a wide range of settings, including pain, overactive bladder, endometriosis and chronic cough [115–117]. Signalling by ATP occurs via purinergic P2 receptors, including ligand-gated ion channels (P2X) and G-protein-coupled receptors (P2Y) [118–120]. There are seven subunits of P2X receptor (P2X1–P2X7), which can form homotrimers (e.g. P2X3) and heterotrimers (e.g. P2X2/3) [120–122]. The P2X3 receptor has been shown to regulate afferent sensory nerve fibre ATP-mediated signalling in the vagus of animals and humans, provoking the cough reflex [7, 123–125]. It is still not clear whether CHS results from changes in P2X3 receptor function, increased receptor density or excessive release of ATP from damaged cells acting on the receptors, although recent studies have demonstrated increased airway sensory nerve density in chronic cough [12]. In reality, cough hypersensitivity is likely to be a combination of several pathophysiological mechanisms.

The development of new potential treatments for RCC, including the first-in-class P2X3 and P2X2/3 receptor antagonist gefapixant [41, 42, 126, 127], as well as more the recently developed eliapixant (BAY 1817080) [128], filapixant (BAY 1902607) [129], BLU-5937 [130], sivopixant (S-600918) [131, 132] and agents acting on other pathways, has provided new insights into the pathophysiology of RCC including the role of P2X3 receptors in humans [13, 133–135]. The clinical effects of these agents are in contrast to data from animal studies [136]; this observation demonstrates the marked differences in receptor distribution and function between species.

In randomized controlled trials, gefapixant was found to reduce cough reflex sensitivity, cough frequency and cough severity compared with placebo in patients with RCC [42, 43, 126, 137, 138]. It was also shown to diminish cough induced by ATP and distilled water, but not the protective cough reflex induced by either citric acid or capsaicin, providing evidence for the peripheral target engagement of ATP-activated P2X3 receptors in the pathophysiology of chronic cough [137]. However, though serious AEs were rare, taste AEs, mainly dysgeusia, were observed in 58–69% of patients receiving gefapixant 45 mg twice daily in phase III trials [138].

Gefapixant has marginal selectivity for P2X3 over P2X2/3 receptors and the observed taste disturbances are thought to reflect an off-target effect on the P2X2/3 heterotrimers located in the taste buds [2, 42, 130, 139]. Preclinical studies and early clinical trials suggest that compounds more selective for the P2X3 homotrimeric receptor over the P2X2/3 heterotrimer, such as eliapixant [128], BLU-5937 [130] and sivopixant [131, 132], reduce cough frequency (table 3) and severity (table 4), although substantial placebo effects complicate the interpretation of the results. The data also suggest a reduced risk of taste AEs compared with gefapixant, although the findings need to be treated with caution since no comparative studies between P2X3 receptor antagonists have been published, and comparisons across trials are complicated by differences in design, treatment duration, patient population and extent of placebo effects. Further investigations are therefore needed to confirm the potential of P2X3 receptor antagonists as a class for the treatment of patients with RCC.

TABLE 3.

Clinical phase II and phase III trial results assessing effects of P2X3 receptor antagonists versus placebo on awake cough frequency in patients with refractory chronic cough (RCC)

| Drug | Dose regimen (n); design, duration | Cough frequency time period | Baseline coughs per hour, mean±sd | End of treatment coughs per hour, mean±sd |

Mean % change in

cough frequency versus placebo, (95% CI) |

Taste AEs, % (dysgeusia, hypogeusia) | |||

| Placebo | Active | Placebo | Active | Placebo | Active | ||||

| Gefapixant, (phase II) [42] | 600 mg twice daily (n=24); 2 weeks | Awake | 65.5±163.4 (n=21) |

37.1±32.2 (n=19) |

43.6±51.4 (n=21) |

11.0±8.3 (n=19) |

−75 (−88, −50), p=0.0003 | 0, 0 | 88, 54 |

| 24 h | 44.7±105.2 (n=20) |

26.6±22.6 (n=18) |

28.9±31.2 (n=20) |

7.7±6.0 (n=18) |

−74 (−87, −46), p=0.001 | ||||

| Gefapixant dose escalation, (phase II) [43] | Part 1: 50–200 mg twice daily (n=29); crossover, 16 days Part 2: 7.5–50 mg twice daily (n=30); crossover, 16 days |

Awake | Part 1: 52.8±40.4 Part 2: 46.1±39.8 |

Part 1: 54.5±41.1 Part 2: 49.6±44.0 |

Part 1: 54.0±39.3 Part 2: 50.6±34.4 |

Part 1: 28.0±23.8 Part 2: 27.0±27.4 |

Part 1: −41 (−59, −15), p<0.05 to −57 (−73, −31), p<0.05 Part 2: −15 (−35, 13) to −56 (−72, −31), p<0.05 |

0, 0 | Part 1: 46–85, 7–15 Part 2: 7–53, NA |

| 24 h | Part 1: 37.9±27.5 Part 2: 32.2±28.0 |

Part 1: 39.7±28.4 Part 2: 36.3±32.3 |

Part 1: 40.6±28.4 Part 2: 37.3±25.9 |

Part 1: 21.3±18.0 Part 2: 20.8±20.5 |

NA, p<0.05 NA, p<0.05 |

||||

| Gefapixant, (phase IIb) [126] | 7.5–50 mg twice daily (n=253); 12 weeks | Awake | 27.6±2.3# | 24.1±3.0# to 28.8±2.2# | 18.2±3.1# | 11.3±2.8# to 14.5±3.7# | −22 (−42, −5), p=0.097 to −37 (−53, −15), p=0.0027 | 5, 2 | 10–48, 0–24 |

| 24 h | 20.5±2.2# | 17.6±3.0# to 21.9±2.2# | 13.7±2.9# | 8.5±2.8# to 10.8±3.6# | −21 (−40, 5), p=0.10 to −38 (−53, −17), p=0.0014 | ||||

| Gefapixant (phase III) [138] | 15 mg twice daily; 45 mg twice daily COUGH-1 (n=730): 12 weeks COUGH-2 (n=1314): 24 weeks |

24 h | COUGH-1: 22.8¶ COUGH-2: 19.5¶ |

COUGH-1: 19.9¶; 18.2¶ COUGH-2: 19.4¶; 18.6¶ |

COUGH-1: 10.3¶ COUGH-2: 8.3¶ |

COUGH-1: 9.7¶; 7.1¶ COUGH-2: 8.1¶; 6.8¶ |

COUGH-1: 2 (−16, 23), ns −18 (−33, −1), p=0.041 COUGH-2: −1 (−14, −14), ns −15 (−26, −1), p=0.031 |

COUGH- 1: 3 COUGH-2: 8 |

COUGH-1: 11, 58 COUGH-2: 20, 69 |

| Eliapixant (phase IIa) [128] | 10–750 mg twice daily (n=40); crossover, 3 weeks | Awake | 33.3±2.5# | 35.4±2.5# (n=39) |

30.5±2.5# | 10 mg: 30.0±2.7 (n=39) 50 mg: 25.6±2.8 (n=39) 200 mg: 22.9±2.7 (n=39) 750 mg: 22.6±2.4 (n=38) |

10 mg: 5 (−11, 24)+, ns 50 mg: –16 (−29, 0.3)+, p<0.05 200 mg: −24 (−36, −11)+, p=0.002 750 mg: −26 (−38, −13)+, p=0.002 |

3, 0 | 0–10, 0–3 |

| 24 h | 25.5±2.5# | 26.6±2.5# | 22.6±2.5 | 10 mg: 22.8±2.6 (n=39) 50 mg: 18.8±2.8 (n=39) 200 mg: 17.1±2.6 (n=39) 750 mg: 16.6±2.4 (n=38) |

10 mg: 10 (−7, 29)+, ns 50 mg: −15 (−28, 0.4)+, ns 200 mg: −23 (−34, −9)+, p=0.004 750 mg: −25 (−37, −12)+, p=0.002 |

||||

| Filapixant (phase IIa) [129] | 20–250 mg twice daily (n=23); crossover, ascending-dose, 4 days per dose | 24 h | NA | NA | NA | NA | 20 mg: NA, ns 80 mg: −17, p=0.015 150 mg: −28, p<0.001 250 mg: −37, p<0.001 |

12 | 4−57 |

| Sivopixant (phase IIa) [131] | 150 mg every day (n=31); crossover, 2 weeks | Awake | NA | NA | NA | NA | −32 (−54, 1), p=0.055 | NA | 3, 3 |

| 24 h | NA | NA | NA | −31, (p=0.0386) | |||||

Data are arithmetic mean±sd unless otherwise stated. #: Geometric mean±geometric sd. ¶: Geometric mean. +: 90% credible limits. AE: adverse event; CI: confidence interval; NA: not available; ns: non-significant; RCC: refractory chronic cough.

TABLE 4.

Clinical phase II and phase III trial results assessing effects of P2X3 receptor antagonists versus placebo on cough severity (VAS) in patients with refractory chronic cough (RCC)

| Drug | Dose regimen (n); design, duration | Baseline cough severity (VAS) mm, mean±sd | End of treatment cough severity (VAS) mm, mean±sd | Estimated mean difference from baseline in cough severity (VAS) mm, (95% CI) | Mean change in cough severity versus placebo, (VAS) mm, (95% CI) | |||

| Placebo | Active | Placebo | Active | Placebo | Active | |||

| Gefapixant, (phase II) [42] | 600 mg twice daily (n=24); 2 weeks | 52.7±16.1 | 48.8±20.7 | 52.0±20.7 | 27.4±28.0 | NA | NA | −25.6 (−41.5, −9.6), p=0.003 |

| Gefapixant dose escalation (phase II) [43] | Part 1: 50–200 mg twice daily (n=29); crossover, 16 days Part 2: 7.5–50 mg twice daily (n=30); crossover, 16 days |

Part 1: 52.2±19.2 Part 2: 57.2±23.7 |

Part 1: 58.4±18.7 Part 2: 54.5±24.3 |

Part 1: 55.6±24.1 Part 2: 48.0±27.0 |

Part 1: 28.0±26.2 Part 2: 30.4±25.3 |

NA | NA | Part 1: −20.0 (−33.6, −6.3) to −33.8 (−48.4, −19.1) Part 2: −15.6 (−27.6, −3.6) to −15.4 (−30.4, −0.5) |

| Gefapixant (phase IIb) [126] | 7.5–50 mg twice daily (n=253); 12 weeks | 57.4±23.1 | 56.7±20.7 to 58.3±25.1 | 39.3±28.1 | 27.9±22.4 to 35.0±23.6 | −16.7 (−22.7, −10.7) | −21.1 (−27.2, −15.1) to −27.9 (−34.1, −21.6) | –4.4 (–12.9, 4.0), p=0.3 to –11.2 (–19.7, –2.6), p=0.0108 |

| Eliapixant (phase IIa) [128] | 10–750 mg twice daily (n=40); crossover, 3 weeks | 70.6±17.3 | 71.4±16.3 (n=39) |

66.4±19.1 (n=39) |

10 mg: 67.2±21.8 (n=38) 50 mg: 61.0±21.4 (n=39) 200 mg: 58.5±23.2 (n=39) 750 mg: 53.0±23.3 (n=38) |

2.9 (−1.7, 7.5)#, ns |

10 mg: −4.2 (1.3, −9.7)#, ns 50 mg: −9.6 (−4.3, −15.1)#, p<0.05 200 mg: −12.2 (−6.8, −17.6)#, p<0.05 750 mg: −17.4 (−12.1, −22.9)#, p<0.05 |

10 mg: −1.4 (3.9, −6.4)#, ns 50 mg: −6.7 (−1.7, −11.7)#, p<0.05 200 mg: −9.3 (−4.1, −14.4)#, p<0.05 750 mg: −14.5 (−9.4, −19.6)#, p<0.05 |

| Filapixant (phase IIa) [129] | 20–250 mg twice daily (n=23); crossover, ascending-dose, 4 days per dose | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 20 mg: NA, ns 80 mg: −8.1 (−1.9, −14.3), p=0.017 150 mg: −14.3 (−8.0, −20.7), p<0.001 250 mg: −20.8 (−14.7, −27.0), p<0.001 |

| Sivopixant (phase IIa) [132] | 150 mg every day (n=31); crossover, 2 weeks | NA | NA | NA | NA | −12.4 | −18.8 | −6.4, p=0.1334 |

Data are mean±sd unless otherwise stated. #: 90% credible limits. CI: confidence interval; NA: not available; ns: non-significant; VAS: visual analogue scale.

Apart from P2X3, other pathways/receptors appear to be involved in CHS, including neurokinin-1 receptor (NK-1) and the transient receptor potential vanilloid (TRPV) 1 and 4 receptors (figure 1). Alternative classes of drugs are in development to target these receptors [134], with mixed results. The archetypal TRPV1 agonist capsaicin is under investigation for the relief of cough and airway symptoms in patients with chronic idiopathic cough (NCT04125563). The NK-1 receptor antagonist orvepitant reduced cough frequency and severity in a phase 2 pilot trial [140]. Drugs acting as antagonists of the TRPV 1 and 4 receptors, TRPA 1 receptors and voltage-gated sodium channel subtype NaV1.7 have so far proven ineffective in phase II studies [1, 139, 141–144], as has the α7 neuronal nicotinic receptor agonist bradanicline [145].

In the search for an effective treatment for RCC, it is important to note that there are many gaps in current understanding of the condition, including its complex pathophysiology, epidemiology, assessment and management, and more particularly its disease burden [2]. It is clear, however, that RCC is heterogeneous in its central and peripheral nervous pathways, underlying diseases and clinical presentations [5, 146]. It is unlikely that a single treatment will be effective in all patients and combination therapy may be required in selected patients. To identify more effective antitussives, it will be important to establish effective research collaborations across multiple sites supported by common investigative and management approaches. With this end in mind, the NEw Understanding in the tReatment Of COUGH (NEUROCOUGH) Clinical Research Collaboration was recently set up [147]. Its key aims are to improve patient care by enhancing clinical expertise, to establish a registry of patients with chronic cough, to increase general understanding of chronic cough through public engagement and to enhance training and research capacity through encouraging young clinicians to enter the cough field.

Other issues that should be considered when evaluating treatments for RCC include placebo effects and regression to the mean. Some studies have suggested that up to 85% of the efficacy of cough medicines is due to a placebo effect [148]. This effect derives partly from “physiological” actions relating to the formulation or taste of the preparation, and possibly a specific effect of a sweet taste, independent of any active ingredient [148–150]. This is a substantial component in the efficacy of cough syrups, though it has little or no relevance to tablet or capsule formulations [148–150]. There is also the “psychological” placebo effect of the patient's belief in the efficacy of therapy, which may influence central cough pathways [149, 151], and natural recovery during the period of administration [148]. Regarding regression to the mean, patients with high activity of a variable disease tend to have values closer to the mean on reassessment even without treatment [152, 153]. When such individuals receive treatment or are recruited into clinical trials, this can lead to artificial inflation of efficacy results [152, 153]. Randomized, placebo-controlled trials can diminish this tendency, as all treatment groups should be equally subject to regression effects, and analysis of covariance can be used to adjust each patient's follow-up measurement based on their baseline values [152, 153].

Conclusions

CHS, the underlying entity of chronic cough and RCC, has been recognized as a distinct condition in recent years. Available evidence suggests a considerable disease burden of chronic cough, including physical and particularly psychological effects that significantly impair QoL. There is also an economic burden, both on patients and on society, from loss of productivity and ineffective use of healthcare resources. This is particularly true in patients with RCC, who by definition are refractory to current therapy, reflecting the fact that these therapies are only partially effective in treating the underlying pathology of cough. New treatments targeting underlying CHS are in advanced development, with the potential to reduce the enormous clinical and societal burden of RCC.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing services were provided by Richard Murphy PhD of Adelphi Communications Ltd, Macclesfield, UK, funded by Bayer AG (Berlin, Germany) in accordance with Good Publications Practice (GPP3) guidelines.

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed.

Author contributions: A. Morice: review concept and design; draft review and editing; supervision; approval of final draft. P. Dicpinigaitis: review design; review and editing; approval of final draft. L. McGarvey: review design; draft review and editing; approval of final draft. S.S. Birring: review design; draft review and editing; approval of final draft.

Conflict of interest: A. Morice reports grants, personal fees, non-financial support and other from Bayer AG, grants, personal fees, non-financial support and other from Bayer US, during the conduct of the study; personal fees, non-financial support and other from Bellus Health, grants, personal fees, non-financial support and other from Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp, personal fees and non-financial support from AstraZeneca, grants, personal fees, non-financial support and other from Sanofi, personal fees and non-financial support from Chiesi Ltd, grants, personal fees and non-financial support from GlaxoSmithKline, personal fees and non-financial support from Boehringer Ingelheim, grants, personal fees and other from NeRRe Therapeutics, grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Respivant Sciences, Inc, grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Phillips Respironics, grants from Menio Therapeutics, consulting fees from Afferent, Pfizer and Proctor & Gamble, and grant support from Afferent, Infirst, and Proctor & Gamble outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: P. Dicpinigaitis reports personal fees from Merck, Bellus, Bayer, Shionogi, and Chiesi, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: L. McGarvey reports grants and personal fees from Bayer AG, during the conduct of the study; grants and personal fees from Merck & Co., Inc., grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Chiesi, grants and personal fees from Bellus Health, non-financial support from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Applied Clinical Intelligence, personal fees from Shionogi Inc., personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, personal fees from NeRRe Therapeutics, from Nocion Therapeutics, other from AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: S.S. Birring reports personal fees from Bayer, grants and personal fees from Merck, personal fees from Shionogi, personal fees from Bellus, personal fees from NeRRe, personal fees from Nocion, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from GSK, and consulting fees from Afferent, outside the submitted work.

Support statement: Bayer AG. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.Roe NA, Lundy FT, Litherland GJ, et al. . Therapeutic targets for the treatment of chronic cough. Curr Otorhinolaryngol Rep 2019; 7: 116–128. doi: 10.1007/s40136-019-00239-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morice AH, Millqvist E, Bieksiene K, et al. . ERS guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic cough in adults and children. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 1901136. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01136-2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibson P, Wang G, McGarvey L, et al. . Treatment of unexplained chronic cough: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest 2016; 149: 27–44. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-1496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morice AH. On chronic cough diagnosis, classification, and treatment. Lung 2021; 199: 433–434. doi: 10.1007/s00408-021-00452-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazzone SB, Chung KF, McGarvey L. The heterogeneity of chronic cough: a case for endotypes of cough hypersensitivity. Lancet Respir Med 2018; 6: 636–646. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30150-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mazzone SB, Undem BJ. Vagal afferent innervation of the airways in health and disease. Physiol Rev 2016; 96: 975–1024. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00039.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonvini SJ, Belvisi MG. Cough and airway disease: the role of ion channels. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2017; 47: 21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2017.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pacheco A. Chronic cough: from a complex dysfunction of the neurological circuit to the production of persistent cough. Thorax 2014; 69: 881–883. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song WJ, Morice AH. Cough hypersensitivity syndrome: a few more steps forward. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2017; 9: 394–402. doi: 10.4168/aair.2017.9.5.394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morice AH, Millqvist E, Belvisi MG, et al. . Expert opinion on the cough hypersensitivity syndrome in respiratory medicine. Eur Respir J 2014; 44: 1132–1148. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00218613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canning BJ, Chang AB, Bolser DC, et al. . Anatomy and neurophysiology of cough: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel report. Chest 2014; 146: 1633–1648. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-1481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shapiro CO, Proskocil BJ, Oppegard LJ, et al. . Airway sensory nerve density is increased in chronic cough. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020; 203: 348–355. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201912-2347OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazzone SB, McGarvey L. Mechanisms and rationale for targeted therapies in refractory and unexplained chronic cough. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2021; 109: 619–636. doi: 10.1002/cpt.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryan NM, Vertigan AE, Birring SS. An update and systematic review on drug therapies for the treatment of refractory chronic cough. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2018; 19: 687–711. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2018.1462795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song WJ, Chung KF. Exploring the clinical relevance of cough hypersensitivity syndrome. Expert Rev Respir Med 2020; 14: 275–284. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2020.1713102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung KF, McGarvey L, Mazzone SB. Chronic cough as a neuropathic disorder. Lancet Respir Med 2013; 1: 414–422. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70043-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morice AH. Chronic cough hypersensitivity syndrome. Cough 2013; 9: 14. doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-9-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burke JM, Jackson W, Morice AH. The role of high resolution oesophageal manometry in occult respiratory symptoms. Respir Med 2018; 138: 47–49. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2018.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patterson N, Mainie I, Rafferty G, et al. . Nonacid reflux episodes reaching the pharynx are important factors associated with cough. J Clin Gastroenterol 2009; 43: 414–419. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31818859a3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morice AH, Lowry R, Brown MJ, et al. . Angiotensin-converting enzyme and the cough reflex. Lancet 1987; 2: 1116–1118. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(87)91547-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agusti A, Bel E, Thomas M, et al. . Treatable traits: toward precision medicine of chronic airway diseases. Eur Respir J 2016; 47: 410–419. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01359-2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplan AG. Chronic cough in adults: make the diagnosis and make a difference. Pulm Ther 2019; 5: 11–21. doi: 10.1007/s41030-019-0089-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holden SE, Morice A, Birring SS, et al. . Cough presentation in primary care and the identification of chronic cough: a need for diagnostic clarity? Curr Med Res Opin 2020; 36: 139–150. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2019.1673716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song WJ, Chang YS, Faruqi S, et al. . The global epidemiology of chronic cough in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2015; 45: 1479–1481. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00218714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gibson PG, Vertigan AE. Management of chronic refractory cough. BMJ 2015; 351: h5590. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h5590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haque RA, Usmani OS, Barnes PJ. Chronic idiopathic cough: a discrete clinical entity? Chest 2005; 127: 1710–1713. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morice AH, Jakes AD, Faruqi S, et al. . Chronic Cough Registry . A worldwide survey of chronic cough: a manifestation of enhanced somatosensory response. Eur Respir J 2014; 44: 1149–1155. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00217813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Long L, Lai K. Characteristics of Chinese chronic cough patients. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2019; 57: 101811. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2019.101811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lätti AM, Pekkanen J, Koskela HO. Defining the risk factors for acute, subacute and chronic cough: a cross-sectional study in a Finnish adult employee population. BMJ Open 2018; 8: e022950. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Everett CF, Kastelik JA, Thompson RH, et al. . Chronic persistent cough in the community: a questionnaire survey. Cough 2007; 3: 5. doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-3-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arinze JT, Verhamme KMC, Luik AI, et al. . The interrelatedness of chronic cough and chronic pain. Eur Respir J 2020; 57: 2002651. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02651-2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Varechova S, Plevkova J, Hanacek J, et al. . Role of gender and pubertal stage on cough sensitivity in childhood and adolescence. J Physiol Pharmacol 2008; 59: Suppl. 6, 719–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang MG, Song WJ, Kim HJ, et al. . Point prevalence and epidemiological characteristics of chronic cough in the general adult population: The Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2010–2012. Medicine 2017; 96: e6486. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lai K, Long L, Yi F, et al. . Age and sex distribution of Chinese chronic cough patients and their relationship with capsaicin cough sensitivity. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2019; 11: 871–884. doi: 10.4168/aair.2019.11.6.871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kang SY, Song WJ, Won HK, et al. . Cough persistence in adults with chronic cough: a 4-year retrospective cohort study. Allergol Int 2020; 69: 588–593. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2020.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chamberlain SA, Garrod R, Douiri A, et al. . The impact of chronic cough: a cross-sectional European survey. Lung 2015; 193: 401–408. doi: 10.1007/s00408-015-9701-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koskela HO, Lätti AM, Pekkanen J. The impacts of cough: a cross-sectional study in a Finnish adult employee population. ERJ Open Res 2018; 4: 00113-02018. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00113-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lätti AM, Pekkanen J, Koskela HO. Persistence of chronic cough in a community-based population. ERJ Open Res 2020; 6: 00229–02019. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00229-2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yousaf N, Montinero W, Birring SS, et al. . The long term outcome of patients with unexplained chronic cough. Respir Med 2013; 107: 408–412. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Birring SS, Fleming T, Matos S, et al. . The Leicester Cough Monitor: preliminary validation of an automated cough detection system in chronic cough. Eur Respir J 2008; 31: 1013–1018. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00057407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGuinness K, Holt K, Dockry R, et al. . P159 validation of the VitaloJAK™ 24 h ambulatory cough monitor. Thorax 2012; 67: A131–A131. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202678.220 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abdulqawi R, Dockry R, Holt K, et al. . P2X3 receptor antagonist (AF-219) in refractory chronic cough: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet 2015; 385: 1198–1205. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61255-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith JA, Kitt MM, Butera P, et al. . Gefapixant in two randomised dose-escalation studies in chronic cough. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 1901615. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01615-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morice AH, Birring SS, Smith JA, et al. . Characterization of patients with refractory or unexplained chronic cough participating in a Phase 2 clinical trial of the P2X3-receptor antagonist gefapixant. Lung 2021; 199: 121–129. doi: 10.1007/s00408-021-00437-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.French CL, Irwin RS, Curley FJ, et al. . Impact of chronic cough on quality of life. Arch Intern Med 1998; 158: 1657–1661. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.15.1657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Young EC, Smith JA. Quality of life in patients with chronic cough. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2010; 4: 49–55. doi: 10.1177/1753465809358249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dicpinigaitis PV. Prevalence of stress urinary incontinence in women presenting for evaluation of chronic cough. ERJ Open Research 2021; 7: 00012-2021. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00012-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zoglmann R, Nguyen T, Engberts M, et al. . Do patients with stress incontinence cough or do cough patients suffer from urinary incontinence? Eur Respir J 2015; 46: PA713. doi: 10.1183/13993003.congress-2015.PA713 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dicpinigaitis PV, Lim L, Farmakidis C. Cough syncope. Respir Med 2014; 108: 244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rehal SS, Aijaz F. Cough syncope whilst driving – An unusual yet serious presentation. Respir Med Case Rep 2020; 31: 101155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee SE, Lee JH, Kim HJ, et al. . Inhaled corticosteroids and placebo treatment effects in adult patients with cough: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2019; 11: 856–870. doi: 10.4168/aair.2019.11.6.856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan VH, Globe G, et al. . Oral corticosteroid exposure and adverse effects in asthmatic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018; 141: 110–116.e117. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Colak Y, Nordestgaard BG, Laursen LC, et al. . Risk factors for chronic cough among 14,669 individuals from the general population. Chest 2017; 152: 563–573. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.05.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Birring SS, Morgan AJ, Prudon B, et al. . Respiratory symptoms in patients with treated hypothyroidism and inflammatory bowel disease. Thorax 2003; 58: 533–536. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.6.533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Song WJ, Morice AH, Kim MH, et al. . Cough in the elderly population: relationships with multiple comorbidity. PLoS One 2013; 8: e78081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kuzniar TJ, Morgenthaler TI, Afessa B, et al. . Chronic cough from the patient's perspective. Mayo Clin Proc 2007; 82: 56–60. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60967-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hulme K, Deary V, Dogan S, et al. . Psychological profile of individuals presenting with chronic cough. ERJ Open Res 2017; 3: 00099-2016. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00099-2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dicpinigaitis PV, Tso R, Banauch G. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among patients with chronic cough. Chest 2006; 130: 1839–1843. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.6.1839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McGarvey LP, Carton C, Gamble LA, et al. . Prevalence of psychomorbidity among patients with chronic cough. Cough 2006; 2: 4. doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-2-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Polley L, Yaman N, Heaney L, et al. . Impact of cough across different chronic respiratory diseases: comparison of two cough-specific health-related quality of life questionnaires. Chest 2008; 134: 295–302. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Won HK, Lee JH, An J, et al. . Impact of chronic cough on health-related quality of life in the Korean adult general population: the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2010–2016. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2020; 12: 964–979. doi: 10.4168/aair.2020.12.6.964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morice AH, McGarvey L. Clinical cough II: therapeutic treatments and management of chronic cough. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2009; 187: 277–295. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-79842-2_14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Matsumoto H, Tabuena RP, Niimi A, et al. . Cough triggers and their pathophysiology in patients with prolonged or chronic cough. Allergol Int 2012; 61: 123–132. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.10-OA-0295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Johansson H, Johannessen A, Holm M, et al. . Prevalence, progression and impact of chronic cough on employment in Northern Europe. Eur Respir J 2021; 57: 2003344. doi: 10.1183/13993003.03344-2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.French CT, Fletcher KE, Irwin RS. Gender differences in health-related quality of life in patients complaining of chronic cough. Chest 2004; 125: 482–488. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.2.482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bartley EJ, Fillingim RB. Sex differences in pain: a brief review of clinical and experimental findings. Br J Anaesth 2013; 111: 52–58. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morice AH, Millqvist E, Belvisi MG, et al. . Cough hypersensitivity syndrome: clinical measurement is the key to progress. Eur Respir J 2015; 45: 1509–1510. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00014215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morice AH, McGarvey L, Pavord I, British Thoracic Society Cough Guideline Group. Recommendations for the management of cough in adults. Thorax 2006; 61 i1–i24. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.065144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Irwin RS, French CT, Lewis SZ, et al. . Overview of the management of cough: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest 2014; 146: 885–889. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-1485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sichali JM, Khan JAK, Gama EM, et al. . Direct costs of illness of patients with chronic cough in rural Malawi–Experiences from Dowa and Ntchisi districts. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0225712. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lai K, Shen H, Zhou X, et al. . Clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis and management of cough–Chinese Thoracic Society (CTS) Asthma Consortium. J Thorac Dis 2018; 10: 6314–6351. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.09.153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Morice AH. Cough. www.issc.info/cough.html Date last accessed: 6 August 2021.

- 73.Natarajan S, Free RC, Bradding P, et al. . The relationship between the Leicester Cough Questionnaire, eosinophilic airway inflammation and asthma patient related outcomes in severe adult asthma. Respir Res 2017; 18: 44. doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0520-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Birring SS, Prudon B, Carr AJ, et al. . Development of a symptom specific health status measure for patients with chronic cough: Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ). Thorax 2003; 58: 339–343. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.4.339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Birring SS, Muccino DR, Bacci E, et al. . Defining minimal clinically important differences (MCID) on the Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ): analyses of a phase 2 randomized controlled trial in chronic cough. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019; 143: AB52. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.12.158 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yousaf N, Lee KK, Jayaraman B, et al. . The assessment of quality of life in acute cough with the Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ-acute). Cough 2011; 7: 4. doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-7-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Spinou A, Birring SS. An update on measurement and monitoring of cough: what are the important study endpoints? J Thorac Dis 2014; 6: S728–S734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Morice AH, Menon MS, Mulrennan SA, et al. . Opiate therapy in chronic cough. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 175: 312–315. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200607-892OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yousaf N, Monteiro W, Parker D, et al. . Long-term low-dose erythromycin in patients with unexplained chronic cough: a double-blind placebo controlled trial. Thorax 2010; 65: 1107–1110. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.142711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ryan NM, Birring SS, Gibson PG. Gabapentin for refractory chronic cough: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2012; 380: 1583–1589. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60776-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vertigan AE, Kapela SL, Ryan NM, et al. . Pregabalin and speech pathology combination therapy for refractory chronic cough: a randomized controlled trial. Chest 2016; 149: 639–648. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Boulet LP, Coeytaux RR, McCrory DC, et al. . Tools for assessing outcomes in studies of chronic cough: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest 2015; 147: 804–814. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-2506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pornsuriyasak P, Kawamatawong T, Rattanasiri S, et al. . Validity and reliability of the Thai version of the Leicester Cough Questionnaire in chronic cough. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol 2016; 34: 212–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gao YH, Guan WJ, Xu G, et al. . Validation of the Mandarin Chinese version of the Leicester Cough Questionnaire in bronchiectasis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2014; 18: 1431–1437. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kwon JW, Moon JY, Kim SH, et al. . Reliability and validity of a Korean version of the Leicester Cough Questionnaire. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2015; 7: 230–233. doi: 10.4168/aair.2015.7.3.230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.French CT, Irwin RS, Fletcher KE, et al. . Evaluation of a cough-specific quality-of-life questionnaire. Chest 2002; 121: 1123–1131. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.4.1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fletcher KE, French CT, Irwin RS, et al. . A prospective global measure, the Punum Ladder, provides more valid assessments of quality of life than a retrospective transition measure. J Clin Epidemiol 2010; 63: 1123–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Field SK, Conley DP, Thawer AM, et al. . Effect of the management of patients with chronic cough by pulmonologists and certified respiratory educators on quality of life: a randomized trial. Chest 2009; 136: 1021–1028. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shaheen NJ, Crockett SD, Bright SD, et al. . Randomised clinical trial: high-dose acid suppression for chronic cough – a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011; 33: 225–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04511.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hsu JY, Stone RA, Logan-Sinclair RB, et al. . Coughing frequency in patients with persistent cough: assessment using a 24 h ambulatory recorder. Eur Respir J 1994; 7: 1246–1253. doi: 10.1183/09031936.94.07071246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kwon JW, Moon JY, Kim SH, et al. . Korean version of the Cough Symptom Score: clinical utility and validity for chronic cough. Korean J Intern Med 2017; 32: 910–915. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2016.132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Vernon M, Kline Leidy N, Nacson A, et al. . Measuring cough severity: development and pilot testing of a new seven-item cough severity patient-reported outcome measure. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2010; 4: 199–208. doi: 10.1177/1753465810372526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Martin Nguyen A, Bacci E, Dicpinigaitis P, et al. . Quantitative measurement properties and score interpretation of the Cough Severity Diary in patients with chronic cough. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2020; 14: 1753466620915155. doi: 10.1177/1753466620915155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Morice AH, Faruqi S, Wright CE, et al. . Cough hypersensitivity syndrome: a distinct clinical entity. Lung 2011; 189: 73–79. doi: 10.1007/s00408-010-9272-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Morice A, Birring S, Dicpinigaitis P, et al. . Cough triggers and symptoms among patients with refractory or unexplained chronic cough in two phase 3 trials of the P2X3 receptor antagonist gefapixant (COUGH-1 and COUGH-2). J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021; 147: AB61. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.12.242 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zhang M, Chen Q, Dong R, et al. . Prediction of therapeutic efficacy of gabapentin by Hull Airway Reflux Questionnaire in chronic refractory cough. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2020; 11: 2040622320982463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Huang Y, Yu L, Xu XH, et al. . Validation of the Chinese version of Hull Airway Reflux Questionnaire and its application in the evaluation of chronic cough. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi 2016; 39: 355–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Johansson EL, Ternesten-Hasséus E. Reliability and validity of the Swedish version of the Hull Airway Reflux Questionnaire (HARQ-S). Lung 2016; 194: 997–1005. doi: 10.1007/s00408-016-9937-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.De La Orden Abad M, Haberland C, Filonenko A, et al. . The Severity of Chronic Cough Diary (SCCD): development of a novel patient-reported outcomes instrument. ISPOR Europe 2020; 23: Suppl. 2, S731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Shrimanker R, Choo XN, Pavord ID. A new approach to the classification and management of airways diseases: identification of treatable traits. Clin Sci (Lond) 2017; 131: 1027–1043. doi: 10.1042/CS20160028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Vertigan AE, Theodoros DG, Gibson PG, et al. . Efficacy of speech pathology management for chronic cough: a randomised placebo controlled trial of treatment efficacy. Thorax 2006; 61: 1065–1069. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.064337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chamberlain S, Garrod R, Birring SS. Cough suppression therapy: does it work? Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2013; 26: 524–527. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2013.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Korsgaard J, Ledet M. Potential side effects in patients treated with inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting β2-agonists. Respir Med 2009; 103: 566–573. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wang K, Birring SS, Taylor K, et al. . Montelukast for postinfectious cough in adults: a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2014; 2: 35–43. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70245-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Calapai G, Casciaro M, Miroddi M, et al. . Montelukast-induced adverse drug reactions: a review of case reports in the literature. Pharmacology 2014; 94: 60–70. doi: 10.1159/000366164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Calverley P, Pauwels R, Vestbo J, et al. . Combined salmeterol and fluticasone in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2003; 361: 449–456. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12459-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Suissa S, Patenaude V, Lapi F, et al. . Inhaled corticosteroids in COPD and the risk of serious pneumonia. Thorax 2013; 68: 1029–1036. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Berkhof FF, Doornewaard-ten Hertog NE, Uil SM, et al. . Azithromycin and cough-specific health status in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic cough: a randomised controlled trial. Respir Res 2013; 14: 125. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-14-125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hansen MP, Scott AM, McCullough A, et al. . Adverse events in people taking macrolide antibiotics versus placebo for any indication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019; 1: CD011825. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011825.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Belvisi MG, Geppetti P. Cough 7: current and future drugs for the treatment of chronic cough. Thorax 2004; 59: 438–440. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.013490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Song SA, Choksawad K, Franco RA, Jr. The effectiveness of nortriptyline and tolerability of side effects in neurogenic cough patients. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2021; 130: 781–787. doi: 10.1177/0003489420970234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Jeyakumar A, Brickman TM, Haben M. Effectiveness of amitriptyline versus cough suppressants in the treatment of chronic cough resulting from postviral vagal neuropathy. Laryngoscope 2006; 116: 2108–2112. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000244377.60334.e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Burnstock G, Campbell G, Satchell D, et al. . Evidence that adenosine triphosphate or a related nucleotide is the transmitter substance released by non-adrenergic inhibitory nerves in the gut. Br J Pharmacol 1970; 40: 668–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1970.tb10646.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Burnstock G, Dumsday B, Smythe A. Atropine resistant excitation of the urinary bladder: the possibility of transmission via nerves releasing a purine nucleotide. Br J Pharmacol 1972; 44: 451–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1972.tb07283.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Burnstock G, Brouns I, Adriaensen D, et al. . Purinergic signaling in the airways. Pharmacol Rev 2012; 64: 834–868. doi: 10.1124/pr.111.005389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Burnstock G. Therapeutic potential of purinergic signalling for diseases of the urinary tract. BJU Int 2011; 107: 192–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09926.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ding S, Zhu L, Tian Y, et al. . P2X3 receptor involvement in endometriosis pain via ERK signaling pathway. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0184647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Burnstock G, Kennedy C. Is there a basis for distinguishing two types of P2-purinoceptor? Gen Pharmacol 1985; 16: 433–440. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(85)90001-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Burnstock G. Purinergic signalling: from discovery to current developments. Exp Physiol 2014; 99: 16–34. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2013.071951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Burnstock G. Purine and purinergic receptors. Brain Neurosci Adv 2018; 2: 2398212818817494. doi: 10.1177/2398212818817494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Abbracchio MP, Burnstock G. Purinoceptors: are there families of P2X and P2Y purinoceptors? Pharmacol Ther 1994; 64: 445–475. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(94)00048-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]