Abstract

In 2017, in recognition of the challenges faced by Member States in managing childhood and adolescent tuberculosis (TB) at a country level, the WHO Regional Office for Europe held a Regional Consultation. In total, 35 countries participated in the consultations representing both high- and low-incidence Member States. Here, we provide an overview of the existing World Health Organization (WHO) documents and guidelines on childhood and adolescent TB and describe the outcomes of this regional meeting. National childhood and adolescent TB guidelines are available in 25% of Member States, while 33% reported that no such guidelines are at hand. In the majority of countries (83%), childhood and adolescent TB is part of the National Strategic Plan. The most pressing challenges in managing paediatric TB comprise the lack of adequate drug formulations, the difficult diagnosis, and treatment of presumed latent TB infection. Investments into childhood and adolescent TB need to be further advocated to achieve the End TB goals set by WHO to eliminate TB by 2030.

Short abstract

A regional consultation on child and adolescent TB was held in 2017 by the WHO Regional Office for Europe. It identified common challenges and key priorities, useful in informing and strengthening the regional response to TB. http://ow.ly/Fg8H30nwBRo

Introduction

The recent United Nations General Assembly High-Level Meeting on Tuberculosis (TB) has created unprecedented momentum in ending TB as the ninth leading cause of death worldwide and the leading cause from a single infectious agent [1, 2]. Dedicated and targeted interventions to reduce childhood and adolescent TB need more attention to achieve this goal by 2030. Despite being a treatable and curable disease and vaccination with Bacillus Calmétte–Guérin in most endemic settings, TB leads to significant morbidity and mortality amongst the young [2, 3]. Childhood and adolescent TB is a major global health problem and is responsible for a considerable burden of overall TB disease. In 2016, 6.9% of the reported 6.3 million new cases of TB were in children aged <15 years [2]. In the World Health Organization (WHO) European Region specifically, 4.4% of new TB cases and relapses were in children, amounting to a notification rate for children of 3.0 per 100 000 [4]. Although children and adolescents represent 26% of the world population and 42% in low-income countries, childhood and adolescent TB has been a neglected aspect of TB scientific and clinical research efforts [5, 6]. The challenges of conducting research and innovation for children and adolescents, the relatively small number of paediatric TB patients compared to adults, as well as the notion that children and adolescents may only play a minor role in transmission partly explain the adult-focused research and development activities to date [6]. This directly translates into difficulties in managing TB under programmatic conditions; examples of the arduous management of the paediatric TB patient comprise the diagnosis with ancient methods including sputum stain microscopy of gastric fluid and the lack of adequate paediatric drug formulas in some countries [7]. Underdiagnosis and misdiagnosis are of concern, especially in children aged <5 years as illustrated by a recent review where between 1% and 23% of pneumonia cases also had TB [8].

TB in children and adolescents is suggestive of active TB in related adults since paediatric TB is mostly contracted in the household setting [9]. Once infected, older children and adolescents represent a reservoir for further transmission to other children and family members [10].

Previous work by the WHO European Regional Childhood TB task force has identified a structural lack of designated childhood and adolescent TB care guidelines in the majority of Member States [11]. Therefore, it is vital to strengthen efforts to implicitly include childhood and adolescent TB in national health strategies, plans and budgets along with the implementation of effective childhood and adolescent TB-targeted public health interventions. Ultimately, decision makers need to realise that addressing childhood and adolescent TB is an essential part of halting the global and regional TB epidemic.

In recognition of these significant challenges, the WHO Regional Office for Europe organised a Regional Consultation on childhood and adolescent TB, which was held in Copenhagen in 2017. Selected objectives of this meeting were to: review the status of common childhood and adolescent TB practices at country level; identify challenges encountered by Member States; establish priorities; and to formulate the next steps to effectively update childhood and adolescent TB policy/guidance in national strategic plans. Each country was asked to provide information on their country's policies on childhood and adolescent TB prior to attendance.

The aims of this article are to review published work guiding the response to childhood and adolescent TB in the WHO European Region and to describe the outcomes of this Regional Consultation.

Key guideline documents for the regional response to childhood and adolescent TB

The global and regional TB and child health community has increasingly recognised childhood and adolescent TB as an important health threat. This is reflected by the first international meeting on childhood and adolescent TB jointly organised by the European Centre for Disease Control and the Stop TB Partnership held in 2011, as well as World TB day 2012 being dedicated to children for the first time in history. The region-specific activities and priorities of the WHO European Regional office are informed by the Consolidated Action Plan to Prevent and Combat Multidrug- and Extensively Drug-resistant Tuberculosis in the WHO European Region 2011–2015 and the follow up Tuberculosis Action Plan for the WHO European Region 2016–2020, as decided by the Regional Committee for Europe [12, 13]. The first plan asked Member States to “develop a special response for TB prevention and control in children […]” [12]. It further required its Member States to incorporate updated childhood and adolescent TB guidelines by mid-2012. The succeeding plan, which built on the first, emphasised that Member States regularly update “childhood tuberculosis guidelines […] according to the latest available evidence and WHO recommendations” [13].

Beyond the regional action plans, general WHO recommendations are summarised in “Guidance for national tuberculosis programmes on the management of tuberculosis in children” [14]. It provides all Member States with comprehensive information on diagnosis, treatment and prevention of childhood and adolescent TB including chapters devoted to managing TB/HIV co-infection, as well as drug-resistant forms of childhood and adolescent TB. This is of particular relevance to the WHO European Region as it comprises those Member States most affected by drug-resistant TB, as well as rising incidences of co-infection with HIV.

To identify challenges and key priorities in the global response to childhood and adolescent TB, two dedicated Roadmaps emerged. The first Roadmap entitled “Roadmap for Childhood Tuberculosis: Towards Zero Deaths” was published in 2013 declaring the goal of a world without TB deaths among children [15]. It outlined 10 key actions to be taken both at global and national levels to mitigate the burden of childhood and adolescent TB, including the specific needs in research, policy development and clinical practice. While significant progress has been made since the first Roadmap, key challenges and missed opportunities are discussed in the 2018 follow-up “Roadmap Towards Ending TB in Children and Adolescents” [16]. It points to insufficient advocacy, political leadership and stakeholder engagement in the response to childhood and adolescent TB, evidenced by the many TB programmes of high-burden countries being dependent on external funding. It also identifies policy practice gaps in scaling up preventative measures, such as contact tracing of affected children and adolescents [16]. Finally, the 2018 Roadmap calls for a family- and community-centred strategy to better integrate childhood and adolescent care. It pinpoints several bottlenecks along the child's pathway from first exposure to TB disease where improved service delivery can yield better detection and help achieve improved cure rates. This Roadmap also emphasises the importance of multisectoral accountability in line with the recently drafted TB multi-sectoral accountability framework [17]. The Roadmap equally notes a lack of joint accountability and resulting verticalisation of the TB response as a major missed opportunity in past years and proposes to foster national leadership and accountability as key actions in the coming years. Another technical document was published in 2018, which specifically addressed children in their recommendations and policy options to reduce TB transmission [18].

Finally, the resolution adopted by the United Nations General Assembly containing a strong political declaration regarding ending TB dedicates several sections to children and adolescents [1]. Apart from recognising the importance of addressing childhood illness and death and HIV-co-infection it also corroborates the significance of providing support to caregivers and the availability of child-friendly drug formulations.

In summary, the numerously available guidance documents and notable work published recently testify that childhood and adolescent TB now receives substantially more attention than before.

Key outcomes of the Regional Consultation on Childhood and Adolescent TB

The minutes of the Regional Consultation are available in the published meeting report [19]. The consultation met in December 2017 with representatives from 35 countries or territories of the WHO European Region. Participating international partners included the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the KNCV TB Foundation, the Global Drug Facility, the Global TB Caucus and representatives from the Global TB Programme. Important updates were provided on new developments in the diagnosis and treatment of childhood and adolescent TB, as well as the procurement of child-friendly dosages and fixed-dose combinations in the region. The consultations agreed on three priority areas that need to be addressed: 1) improved case detection rate and notification of missed cases; 2) managing children that have been exposed to adults infected with drug-resistant TB; and 3) further investigations into drug-resistant TB detection, reporting and treatment in children.

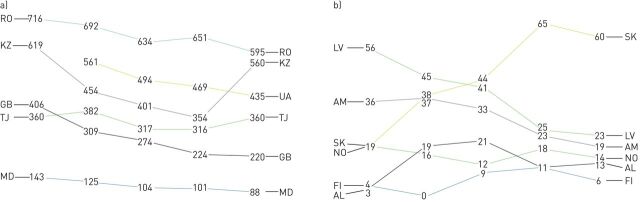

Childhood TB in selected participating member states

The participating Member States comprised both high- and low-incidence countries. The notified annual cases of TB in children aged 0–14 years for selected countries from 2012 to 2016 are shown in figure 1. Most countries display a decreasing trend over the years (Romania, Ukraine, Great Britain, Republic of Moldova, Latvia, Armenia and Norway). Other countries reported increased numbers over the presented time-period (Albania, Slovakia and Kazakhstan). Kazakhstan reported an increase of 61% between 2015 and 2016 (354 to 580 notified cases, respectively) (figure 1). This rise is not mirrored in the notified adult TB cases which steadily decreased over previous years with 12 942 reported cases in 2017 of both childhood and adult TB [20].

FIGURE 1.

a and b) Trends of childhood tuberculosis (TB) notified cases in 2012–2016. Slope graph showing the number of notified cases of TB among children aged 0–14 years in selected countries who participated in the Regional Consultation on Childhood TB in 2017. RO: Romania; KZ: Kazakhstan; GB: United Kingdom of Great Britain and Nothern Ireland; TJ: Tajikistan; MD: Republic of Moldova; UA: Ukraine; LV: Latvia; AM: Armenia; SK: Slovakia; NO: Norway; FI: Finland; AL: Albania.

Improved access to rapid molecular diagnostics, such as line probe assays or GeneXpert, have upgraded the diagnostic capacity and algorithms in many high-burden countries. In addition, the burden of childhood and adolescent TB has only recently been recognised and this may support increased case detection. Out of 55 countries that report to the WHO Regional Office for Europe only 28 (51%) had conveyed complete data on childhood and adolescent TB cases between 2010 and 2016. The remaining countries either reported incomplete data (21 countries, 38%) or no data at all (six countries, 11%) (WHO Regional Office for Europe based on data received from Member States). This finding further illustrates that countries need to increase their attention to their paediatric TB population including improved case detection and reporting.

Presence of national guidelines on childhood and adolescent TB in the WHO European region

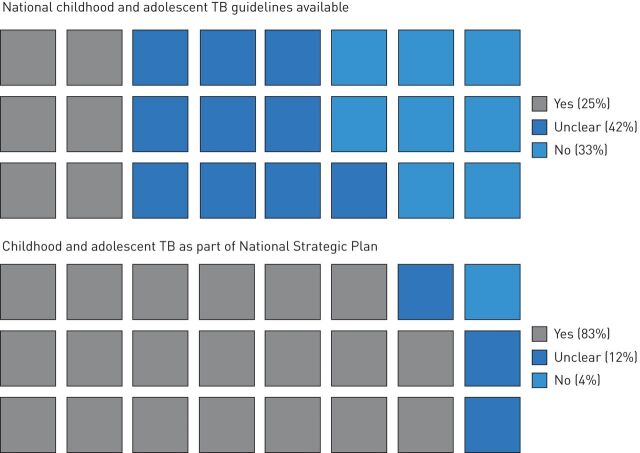

The current and former regional action plans both call for the implementation of national guidelines on childhood and adolescent TB. To explore the presence of dedicated national guidelines we asked participating countries prior to the consultations whether child-specific national TB guidelines were available. 25% reported the presence of national TB guidelines on childhood and adolescent TB, 33% replied that there were no guidelines available and 42% responded that this was unclear (figure 2). They were then asked whether childhood and adolescent TB were part of a National Strategic Plan; 83% replied “yes”, 12% replied “unclear” and 4% replied “no”.

FIGURE 2.

Waffle-plot showing the percentages of countries whose national guidelines or strategic plans comprehend dedicated childhood tuberculosis (TB) strategies. Data obtained was provided in the questionnaires distributed prior to both consultations.

33% of participating countries had no such documentation of childhood and adolescent TB-specific guidelines despite encouragement and support from the WHO Regional Office for Europe and other partners since the Consolidated Action Plan in 2011. However, the large majority of Member States discuss childhood and adolescent TB within their national strategic plans and only very few do not mention childhood and adolescent TB at all. These are indeed positive results as this illustrates that childhood and adolescent TB is on the agenda. The adult guidelines for treating and managing TB cannot be simply applied to childhood and adolescent TB. Many differences exist in managing TB in adults and the young; for example, young children are at a higher risk of developing severe forms of TB and the diagnosis is often challenging [16]. It is important to have guidelines explicitly designed for children and adolescents that take these particularities into account.

An earlier survey conducted by the WHO European Regional Taskforce on Childhood TB found that only 21% of 28 responding Member States of the WHO European Region had a designated TB care policy for adolescents [11]. Therefore, our present findings represent only a minor increase in Member States with national guidelines (25%) but a promising proportion of countries where childhood and adolescent TB is part of the national strategic plan (83%).

Challenges experienced by countries in managing childhood and adolescent TB

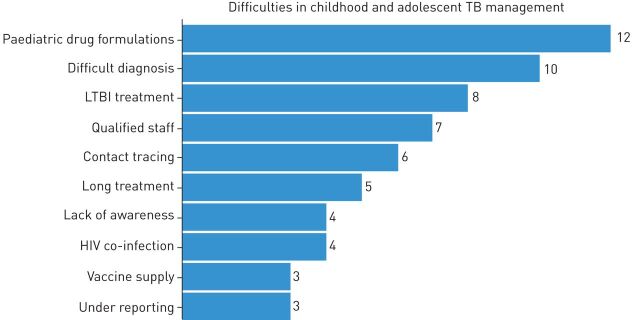

To obtain further insights into the key challenges in childhood and adolescent TB management experienced by participating countries a questionnaire was distributed in advance to the 2015 Regional Consultation. Here, we analysed the number of responding countries (22 (76%) out of 29). The lack of appropriate child-friendly drug formulations was named most often by country representatives (n=12) (figure 3). The difficult diagnosis of childhood and adolescent TB and the challenging treatment of latent TB infection was reported by 10 and eight countries, respectively. Lack of qualified staff to detect, diagnose and treat childhood and adolescent TB appears to be a challenge, as it was named by seven respondents.

FIGURE 3.

The number of countries naming specific challenges in paediatric tuberculosis (TB) management as obtained from the questionnaires distributed prior to both consultations.

In December 2015, WHO and the Global Alliance for TB Drug Development have launched child-friendly fixed-dose combinations for the treatment of pan-susceptible TB in children weighing <25 kg [21]. Since then, considerable progress has been made to provide these drugs to all countries. In 2018, seven high-priority TB countries in the region (Armenia, Bulgaria, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan) procured paediatric drug formulations through the Green Light Committee, which is funded by the Global Drug Facility. These fixed-dose combinations are water-dispersible with a pleasant taste aiding in improving treatment for young children [21].

During the Regional Consultation, these key challenges were discussed and most countries in the region reported considerable progress, notably in procuring child-friendly drugs. Difficult diagnosis and treatment of TB and latent TB infection, particularly in children, remains a challenge that needs to be addressed.

Conclusions and outlook

Thanks to substantial efforts by the global health community, childhood and adolescent TB is being recognised as a health priority worldwide. Today, mortality caused by childhood and adolescent TB is reflective of a systemic disregard of the health system to childhood and adolescent TB and needs to be urgently addressed. Childhood and adolescent TB is a silent epidemic; treatable and curable, yet fatal for too many of those that are too young to fight for themselves. Childhood and adolescent focused local interventions which are sensitive to the social and cultural context are required to further reduce the indicators of childhood and adolescent TB. The overall country-specific management of childhood and adolescent TB needs to be embedded in the national TB programme by all Member States. All stakeholders involved in the child health sector, including primary care physicians and paediatricians, need to be sensitised to TB as a differential in their daily work.

The Regional Consultation provided valuable insights into the policy and practice in participating Member States. One limitation is that data collection regarding the presence of childhood- and adolescent-specific guidelines and overall challenges were not collected using a structured and validated questionnaire.

On a global level much progress has been made to pin down global goals on ending TB, such as the UN Sustainable Development Goal (Goal 3) or the WHO End TB Strategy to reduce the number of TB deaths by 95% until 2035 [22]. Likewise, regional initiatives are essential in fostering more efforts towards TB elimination. Recently, a United Nations common position on ending HIV, TB and viral hepatitis through intersectoral collaboration was signed to direct and guide joint approaches and collaboration within and across sectors [23]. With the aim of fostering partnerships and synergetic country-specific and regional intervention this United Nations common position paper will hopefully lead to increased awareness on the as yet unmet needs of the WHO European Region. Childhood and adolescent TB needs to be prioritised by all stakeholders to improve care for children with TB, with the final aim of eliminating TB during our generation. Likewise, regional initiatives are essential in fostering more efforts towards TB elimination [24–28].

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Rosella Centis (Public Health Consulting Group, Lugano, Switzerland) and Lia D'Ambrosio (Istituti Clinici Scientifici Maugeri IRCCS, Tradate, Italy) for the editorial support in finalising the manuscript.

Footnotes

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed.

Conflict of interest: M.I. Gröschel has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: M. van den Boom has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: G.B. Migliori has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: M. Dara has nothing to disclose.

Support statement: G.B. Migliori is under the operational research plan of the WHO Collaborating Centre for Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases, Tradate, Italy (ITA-80, 2017–2020) and Global Tuberculosis Network Working Group on Paediatric TB.

References

- 1.United Nations General Assembly. Political declaration of the high-level meeting of the General Assembly on the fight against tuberculosis. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly in New York on 10 October 2018. Resolution document A/73/L.4. https://undocs.org/A/73/L.4 Date last accessed: November 30, 2018.

- 2.World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2018. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dara M, Acosta CD, Rusovich V, et al. Bacille Calmette–Guérin vaccination: the current situation in Europe. Eur Respir J 2014; 43: 24–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control/WHO Regional Office for Europe. Tuberculosis surveillance and monitoring in Europe 2017. Stockholm, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.The World Bank. 2.1 World Development Indicators: Population dynamics. http://wdi.worldbank.org/table/2.1 Date last accessed: November 30, 2018 Date last updated: 2017.

- 6.Newton SM, Brent AJ, Anderson S, et al. Paediatric tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis 2008; 8: 498–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jenkins HE. Global Burden of Childhood Tuberculosis. Pneumonia (Nathan) 2016; 8: 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliwa JN, Karumbi JM, Marais BJ, et al. Tuberculosis as a cause or comorbidity of childhood pneumonia in tuberculosis-endemic areas: a systematic review. Lancet Respir Med 2015; 3: 235–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shingadia D, Novelli V. Diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis in children. Lancet Infect Dis 2003; 3: 624–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Acosta CD, Rusovich V, Harries AD, et al. A new roadmap for childhood tuberculosis. Lancet Glob Health 2014; 2: e15–e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blok N, van den Boom M, Erkens C, et al. Variation in policy and practice of adolescent tuberculosis management in the WHO European Region. Eur Respir J 2016; 48: 943–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Consolidated action plan to prevent and combat multidrug- and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in the WHO European Region 2011–2015. www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/147832/wd15E_TB_ActionPlan_111388.pdf?ua=1 Date last updated: July 21, 2011. Date last accessed: November 30, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.World Health Organization. Tuberculosis action plan for the WHO European Region 2016–2020. Document EUR/RC65/17 Rev.1. Copenhagen, World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Guidance for national tuberculosis programmes on the management of tuberculosis in children. Second edition. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Roadmap for childhood tuberculosis: towards zero deaths. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Roadmap towards ending TB in children and adolescents. Second edition. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. Draft multisectoral accountability framework to accelerate progress to end TB. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Migliori GB, D'Ambrosio L, Centis R, et al. Guiding Principles to Reduce Tuberculosis Transmission in the WHO European Region. Copenhagen, World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Regional workshop on child and adolescent tuberculosis in the WHO European Region. Copenhagen, World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization. Tuberculosis country profiles: Kazakhstan. https://extranet.who.int/sree/Reports?op=Replet&name=%2FWHO_HQ_Reports%2FG2%2FPROD%2FEXT%2FTBCountryProfile&ISO2=KZ&LAN=EN&outtype=html. Date last update: January 31, 2019. Date last accessed: November 30, 2018.

- 21.World Health Organization, UNICEF. Statement on the use of child-friendly fixed-dose combinations for the treatment of TB in children. www.who.int/tb/areas-of-work/children/WHO_UNICEFchildhoodTBFDCs_Statement.pdf?ua=1. Date last accessed: November 30, 2018.

- 22.Uplekar M, Weil D, Lonnroth K, et al. WHO's new end TB strategy. Lancet 2015; 385: 1799–1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. United Nations common position on ending HIV, TB and viral hepatitis through intersectoral collaboration. Copenhagen, World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diel R, Loddenkemper R, Zellweger JP, et al. Old ideas to innovate tuberculosis control: preventive treatment to achieve elimination. Eur Respir J 2013; 42: 785–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matteelli A, Rendon A, Tiberi S, et al. Tuberculosis elimination: where are we now? Eur Respir Rev 2018; 27: 180035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matteelli A, Sulis G, Capone S, et al. Tuberculosis elimination and the challenge of latent tuberculosis. Presse Med 2017; 46: e13–e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lönnroth K, Migliori GB, Abubakar I, et al. Towards tuberculosis elimination: an action framework for low-incidence countries. Eur Respir J 2015; 45: 928–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voniatis C, Migliori GB, Voniatis M, et al. Tuberculosis elimination: dream or reality? The case of Cyprus. Eur Respir J 2014; 44: 543–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]