Abstract

Siroheme, the cofactor for sulfite and nitrite reductases, is formed by methylation, oxidation, and iron insertion into the tetrapyrrole uroporphyrinogen III (Uro-III). The CysG protein performs all three steps of siroheme biosynthesis in the enteric bacteria Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica. In either taxon, cysG mutants cannot reduce sulfite to sulfide and require a source of sulfide or cysteine for growth. In addition, CysG-mediated methylation of Uro-III is required for de novo synthesis of cobalamin (coenzyme B12) in S. enterica. We have determined that cysG mutants of the related enteric bacterium Klebsiella aerogenes have no defect in the reduction of sulfite to sulfide. These data suggest that an alternative enzyme allows for siroheme biosynthesis in CysG-deficient strains of Klebsiella. However, Klebsiella cysG mutants fail to synthesize coenzyme B12, suggesting that the alternative siroheme biosynthetic pathway proceeds by a different route. Gene cysF, encoding an alternative siroheme synthase homologous to CysG, has been identified by genetic analysis and lies within the cysFDNC operon; the cysF gene is absent from the E. coli and S. enterica genomes. While CysG is coregulated with the siroheme-dependent nitrite reductase, the cysF gene is regulated by sulfur starvation. Models for alternative regulation of the CysF and CysG siroheme synthases in Klebsiella and for the loss of the cysF gene from the ancestor of E. coli and S. enterica are presented.

Sulfur is a constituent of numerous critical biomolecules in the cell, including cysteine, methionine, glutathione, thiamine, biotin, lipoic acid, and coenzyme A. In these organic molecules, sulfur is typically found in its fully reduced state of sulfide (S2−), while the dominant form of sulfur in the environment is the fully oxidized form, sulfate (SO42−). Bacterial assimilation of sulfur typically entails the acquisition and reduction of sulfate to sulfide before its incorporation into activated serine to form cysteine (11). Alternatively, fungi and some bacteria assimilate sulfide into activated homoserine to form homocysteine (25). Cysteine then serves, either directly or indirectly, as the source of reduced sulfur in all other molecules in the cell.

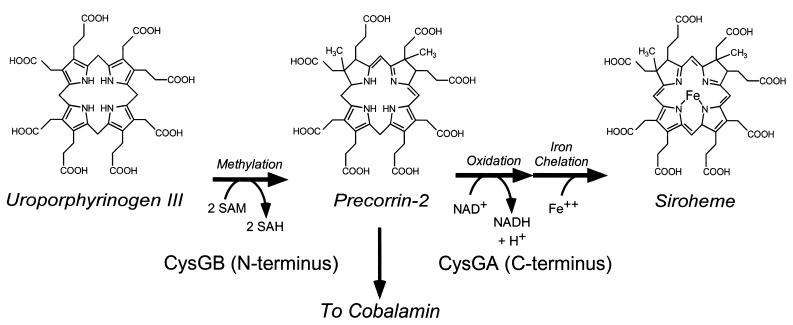

A key enzyme in the sulfate reduction process is sulfite reductase, which performs a stepwise, six-electron reduction of sulfite to sulfide (22). Sulfite reductase employs an unusual heme cofactor, siroheme, in the electron transfer pathway from NADPH to the bound sulfur compound. Siroheme is synthesized by methylation, oxidation, and insertion of iron (24, 27, 28) from uroporphyrinogen III (Uro-III), an intermediate in the heme biosynthetic pathway (Fig. 1). In the enteric bacteria Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica, this process is catalyzed by the product of the cysG gene; mutants lacking this gene fail to reduce sulfite and are cysteine auxotrophs. The methylation functions of CysG are catalyzed by the C-terminal portion of the enzyme; proteins homologous to this domain perform methylation of Uro-III and other tetrapyrroles (20). Metal insertion appears to be catalyzed by the N-terminal portion of CysG (4).

FIG. 1.

Structure and assembly of siroheme. Biochemical reactions noted along the center are catalyzed by the CysG protein in enteric bacteria.

Salmonella also synthesizes cobalamin (coenzyme B12) from Uro-III (7), a process that requires at least the methylation activity of the CysG enzyme (Fig. 1). Since cobalamin contains a central cobalt atom, it is likely that an iron-free intermediate in siroheme biosynthesis is released from the CysG enzyme, making it available to cobalamin biosynthetic enzymes (encoded by the cbi and cob genes). While it has been proposed that CysG also performs cobalt insertion (4), this activity has also been ascribed to the CbiK protein, encoded within the cbi/cob operon (19). Unlike Salmonella, E. coli cannot synthesize B12 de novo (14) and uses CysG activity solely for siroheme biosynthesis.

Despite their central role in the synthesis of siroheme and coenzyme B12, the cysG genes of E. coli and S. enterica are not regulated by the need for B12 production or sulfite reduction. Rather, the cysG gene is cotranscribed with the nirBCD operon, which encodes a siroheme-dependent nitrite reductase (16, 18). The nirBCDcysG transcription unit is induced anaerobically in the presence of nitrate or nitrite, allowing for nitrite reduction during anaerobic nitrate respiration (6). Neither the CysB protein (positive activator of the cys regulon) nor the PocR protein (positive activator of the cbi/cob operon) appears to regulate cysG expression. Although induced only anaerobically in the presence of nitrate or nitrite, baseline production of CysG appears to be sufficient to supply siroheme and cobalamin under other growth conditions.

Here we describe siroheme biosynthesis in the related enteric bacterium Klebsiella aerogenes. We show that two pathways mediate siroheme biosynthesis in this organism; however, only one pathway allows for B12 biosynthesis. The gene encoding the second siroheme biosynthetic pathway (cysF) was likely lost from the ancestor of E. coli and Salmonella after divergence from the Klebsiella lineage. We present models for the role of CysF in Klebsiella and for its loss from the ancestor of E. coli and S. enterica.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The parental strain, LD561 (hsdR hutC515(Con) dadA lac Δbla-2), is a derivative of K. aerogenes W70 and was kindly provided by R. Bender; this strain had been cured of plasmids bearing antibiotic resistance genes and carries a spontaneous mutation conferring sensitivity to bacteriophage P1 (5). To confer sensitivity to bacteriophage λ, plasmid pTAS1 was introduced in Klebsiella strains by electroporation. Plasmid pTAS1 was derived from pTROY11 (3) by deletion of DNA between the HindIII and BamHI sites, removing part of the tet gene (21). Plasmid pMMK1 was constructed by inserting an EcoRI fragment of pNK2881 (10)—encoding the Tn10 altered-target specificity (ATS) transposase, which mediates transposition with relaxed target site specificity—into the corresponding site of pTAS1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains

| Straina | Relevant genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| LD561 | Wild type | KC2668, R. Bender |

| LD806 | pTAS1 (LamB+) | 21 |

| LD807 | metE4021::Tn10dKn | 21 |

| LD821 | pMMK1 (LamB+ Tn10 ATSb transposase) | This study |

| LD808 | cysG4066::Tn10dCm | This study |

| LD809 | cysG4066::Tn10dCm metE4021::Tn10dKn | This study |

| LD810 | cysG4067::Tn10dTc | This study |

| LD811 | cysG4067::Tn10dTc metE4021::Tn10dKn | This study |

| LD812 | cbiG4035::Tn10dCm | This study |

| LD813 | cbiG4035::Tn10dCm metE4021::Tn10dKn | This study |

| LD814 | cysF4068::Tn10dCm | This study |

| LD815 | cysF4069::Tn10dCm | This study |

| LD844 | cysF4073::Tn10LK | This study |

| LD816 | cysF4068::Tn10dCm cysG4067::Tn10dTc | This study |

| LD817 | cysF4069::Tn10dCm metE4021::Tn10dKn | This study |

| LD818 | cysF4069::Tn10dCm cysG4067::Tn10dTc metE4021::Tn10dKn | This study |

| JM107 | E. coli endA1 gyrA96 thi hsdR17 supE44 relA1 Δ(lac proAB) F′ traD36 proAB lacIqlacZΔM15 | Laboratory collection |

| LD819 | JM107 with pMMK23 | This study |

| LD820 | JM107 with pMMK12 | This study |

| LD845 | E. coli XL2-Gold-Kn (Stratagene) with pLAK1 | This study |

| LD846 | E. coli XL2-Gold-Kn (Stratagene) with pLAK2 | This study |

| LD839 | cysD4072::Tn10dCm | 21 |

| LD855 | E. coli XL2-Gold-Kn (Stratagene) with pTAS6 | 21 |

All strains are derivatives of K. aerogenes W70 unless otherwise noted.

ATS, altered-target specificity.

Media and growth conditions.

The rich medium used was Luria-Bertani medium (LB); chloramphenicol was added to 20 μg/ml, tetracycline was added to 10 μg/ml, and ampicillin was added to 200 μg/ml. MacConkey plates were supplemented with 20 μM CoCl2 and 1% propanediol. The defined medium was E (26); NCE medium comprises carbon-free E medium lacking the citrate chelator. Glucose was added at 0.2%, glycerol was added at 0.4%, cysteine was added at 0.005%, KNO3 was added at 20 mM, fumarate was added at 20 mM, and cyanocobinamide or cyanocobalamin was added at 100 nM. Solid media contained 1.2% agar. Cultures were incubated at 37°C; anaerobic growth was performed in a Forma Scientific anaerobic chamber at 30°C. A 1/1,000 dilution of liquid LB was added to defined medium to provide micronutrients under anaerobic growth conditions.

Genetic techniques.

Insertion mutations were created by delivery of transposition-defective derivatives of Tn10 via bacteriophage λ vectors (10) into pTAS1- or pMMK1-bearing strains; λNK1323 (delivering Tn10dCm), λNK1316 (delivering Tn10dTc), and λ1205 (delivering Tn10LK) were provided by N. Kleckner. The bacteriophage vectors were amplified in E. coli C600 cells. To create insertion mutants, cells were mixed with bacteriophage lysates and incubated for 60 min at 37°C before being plated on selective media. Since λ1205 does not encode a Tn10 transposase, pMMK1-bearing cells were used for mutagenesis with Tn10LK; after being screened on selective media, candidate mutations were immediately transduced into a transposase-free background.

Transduction employed bacteriophage P1 vir. To prepare transducing lysates, cells were diluted 1:100 into LB–5 mM CaCl2 and grown for 1 h prior to the addition of bacteriophage P1 to a final titer of 107 PFU · ml−1. Lysates that cleared within 6 h were sterilized by chloroform addition. For transduction, recipient cells were grown to mid-log phase, concentrated by centrifugation, and resuspended in 1/4 volume of 5 mM CaCl2–10 mM MgSO4. After incubation on ice for 30 min, 100 μl of cells was added to 100 μl of bacteriophage lysate and the mixture was incubated at 30°C for 60 min and added to 150 μl of 1 M sodium citrate. The resulting mixture was plated on the appropriate medium.

Cloning and sequencing.

Bacterial chromosomal DNA was partially digested with endonuclease Sau3AI and size-fractionated on an agarose gel. Large-molecular-weight fragments were isolated and ligated to pUC18 or pNEB193 DNA cleaved with BamHI and treated with alkaline phosphatase. Ligations were introduced in JM107 cells by electroporation (for cysG) or into XL2-Gold-Kn cells (Stratagene) by chemical transformation according to the manufacturer's instructions; transformants were isolated on LB-ampicillin and screened for chloramphenicol-resistant colonies by replica printing to LB-chloramphenicol. For both the cysG and cysF loci, the nucleotide sequences of both strands of several clones were determined using an ABI 310 sequencer; sequencing reactions were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Data analysis.

Sequencher (GeneCodes) was used for sequence assembly. Sequence analysis employed the DNA Master, BLAST (1), and GCG program packages (2).

Enzyme assays.

Assays for β-galactosidase activity were performed as described previously (17). Assays for nitrite reductase activity were performed using a modification of the procedure of Snell and Snell (23), whereby residual nitrite, following consumption by cellular nitrite reductase, is assayed colorimetrically. Cells were pregrown anaerobically in E medium-glucose before dilution into E-glucose assay medium; assay medium optionally contained 20 mM KNO3 and/or 0.005% cysteine. After growth to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ∼0.5, cells were rinsed in E salts and resuspended in E–glucose–1 mM KNO2. Periodically, a 100-μl aliquot was removed and diluted into 4.4 ml of 1% sulfanilamide (in 1 M HCl)–0.5 ml of 0.02% N-1-naphthylethylenediamine dihydrochloride. After incubation at room temperature for 20 min, absorption was measured at 540 nm. Nitrite concentrations were estimated by comparison to a standard curve; the rate of nitrite consumption was estimated by linear regression of nitrite concentration versus time. Protein concentration was estimated from the absorbance of the final cell suspension at 550 nm. Nitrite reductase activity was calculated as nanomoles of nitrite consumed per minute per milligram of protein.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

DNA sequences determined in this study have been deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF308467 and AF308468.

RESULTS

Isolation of B12-deficient mutants.

To isolate K. aerogenes insertion mutants, two strategies were adopted. First, λNK1324 was used to deliver Tn10dCm into a wild-type strain bearing plasmid pTAS1 (LD806). A library of ∼50,000 independent mutants was collected. To identify mutants defective in the biosynthesis of cobalamin (coenzyme B12), colonies were screened on MacConkey-propanediol agar; mutants incapable of synthesizing coenzyme B12 were unable to degrade propanediol and appeared as white colonies, whereas normal propanediol degradation produces prodigious amounts of propionic acid, turning the colonies red. Mutants defective in cobalamin biosynthesis were corrected by the addition of cobalamin to the MacConkey agar, which allowed for acid production. A total of 52 Tn10dCm insertion mutants defective in B12 biosynthesis were isolated. In the second strategy, λNK1323 was used to deliver Tn10dTc into a metE mutant bearing plasmid pTAS1; metE mutants must use the cobalamin-dependent MetH protein to synthesize methionine. Tetracycline-resistant mutants were isolated and screened under anaerobic conditions for methionine auxotrophs that were corrected by the addition of cobalamin to the growth medium. A total of 11 Tn10dTc insertion mutants defective in B12 biosynthesis were isolated.

In both screens, mutations were transduced back to the parental background to verify 100% linkage between a single transposon insertion and the mutant phenotype. Mutations were sorted into linkage groups by analysis of frequencies of cotransduction between the chloramphenicol-resistant and tetracycline-resistant insertions. One linkage group comprised two insertions, one Tn10dCm (strain LD808) and one Tn10dTc (strain LD810), that were 100% linked to each other and unlinked to the remaining mutations. Mutations defining additional linkage groups of B12-biosynthetic genes will be discussed elsewhere (M. M. Kolko, N. M. Scott, and J. G. Lawrence, unpublished data).

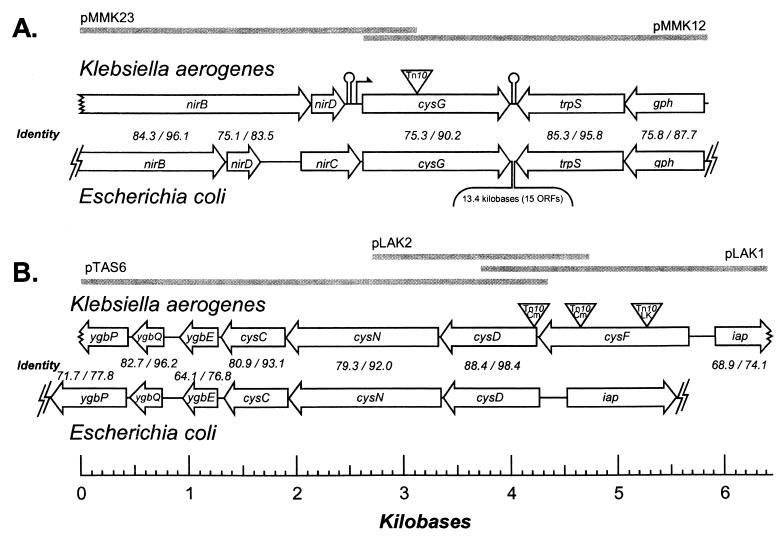

Physical characterization of the cysG region.

A plasmid library was constructed from strain LD808 as described above. Plasmids were introduced into JM107, and transformants were screened for chloramphenicol resistance conferred by a cloned Tn10dCm by replica plating. Plasmids were isolated from 24 chloramphenicol-resistant transformants, and the sequences of their inserts adjoining the vector were determined. From these data, two overlapping clones (pMMK12 and pMMK23) were identified and their sequences were determined completely; in total, a 7,343-bp contiguous sequence was assembled. A good fit (GGTTAAGCA) to the canonical Tn10 9-bp target duplication (NRYYNRRYN) was observed adjacent to the Tn10dCm sequence; excision of these regions yielded a 5,854-kb sequence. The sequence across the Tn10dCm insertion site was determined from a PCR-amplified fragment of the corresponding region in wild-type cells. The location of the Tn10dTc insertion site in LD810 was determined by PCR and by sequencing the appropriate fragment; Tn10dTc is found in the same position as Tn10dCm in LD808 (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

(A) The cysG regions of K. aerogenes and E. coli. Open reading frames (ORFs) in Klebsiella are named after their E. coli homologues; percentages of nucleotide/protein identities to homologous Klebsiella ORFs and proteins are noted above each E. coli gene. Triangle, common site of Tn10 insertions in strains LD808 and LD810; gray bars, extent of the inserts in plasmids pMMK12 and pMMK23. (B) The cysFDNC operon region of K. aerogenes and the corresponding region of E. coli. Triangles, sites of Tn10 insertions in strains LD839, LD814, and LD844.

The 5,854-bp region contained five open reading frames (Fig. 2). Genes were identified by the homology of their products to E. coli proteins as revealed by BLAST; sequences were 75 to 85% identical to E. coli genes, and encoded proteins were between 83 and 96% identical to their E. coli homologues. A single amino acid insertion at codon 85 of the Klebsiella gdh gene was the only length polymorphism observed. Only the 3′ portion of the nirB gene, encoding the C-terminal 715 of 848 amino acids, was cloned.

Three of the genes may form an operon and contribute to a single function, reduction of nitrite to ammonia. The nirB and nirD genes encode subunits of nitrite reductase, while the product of the cysG gene, siroheme synthase, provides the necessary cofactor for the NirBD enzyme. A homologue of the E. coli nirC gene was not observed; the contribution of the nirC gene product to nitrite reduction in E. coli is not clear. The two Tn10 insertions were located in the 5′ end of the Klebsiella cysG gene, encoding siroheme synthase (Fig. 2). Homologues of the E. coli trpS and gph genes are located downstream of the cysG gene. Since the cysG gene is the last gene in its transcription unit, the phenotype of cysG mutants is not likely to be the result of polar effects. A likely terminator (5′ CCCCCCGGCCACGGGGGG) is located downstream of the nirD gene, and a strong, likely bidirectional terminator (5′ AAAAAAGGGCGGGATATCATCCCGCCCTTTT [underlined poritions are inverted repeats]) is located between the cysG and trpS genes.

Phenotype of the cysG mutants.

Both cysG insertion mutants were tested for defects in B12 biosynthesis using three independent assays. First, B12-dependent degradation of propanediol was examined on MacConkey indicator medium, which turns red upon the production of propionate from propanediol; the lack of propanediol degradation was corrected by the addition of exogenous B12 (note that, unlike S. enterica, Klebsiella synthesizes prodigious amount of B12 under aerobic conditions 15). Second, methionine synthesis by MetH was examined in a metE mutant background; both mutants were tight methionine auxotrophs under aerobic and anaerobic conditions that were correctable by the addition of B12. Last, it was found that the function of the B12-dependent glycerol dehydratase was also compromised in cysG mutants, preventing glycerol fermentation but not glycerol respiration to fumarate (Table 2). In all assays, cysG mutants showed defects that were correctable by the addition of exogenous cobinamide or cobalamin (Table 2), suggesting that cysG mutants in Klebsiella, like those of Salmonella, are unable to synthesize coenzyme B12. However, unlike those of Salmonella, Klebsiella cysG mutants have no defect in cysteine biosynthesis under either aerobic or anaerobic conditions, indicating that an alternative mechanism for siroheme synthesis must be employed.

TABLE 2.

Phenotypes of K. aerogenes cys mutants

| Strain (genotype) | Aerobic growth on Mac-PD supplemented witha:

|

Anaerobic growth inb:

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCE-Glu supplemented with:

|

NCE-Gly supplemented with:

|

||||||||||||

| 0 | B12 | 0 | Met | B12 | Cys | Cys+B12 | 0 | B12 | Fum | Cys | Cys+B12 | ||

| LD561 (wild type) | R | R | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| LD807 (metE) | R | R | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| LD808 (cysG) | W | R | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | |

| LD809 (cysG metE) | W | R | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | |

| LD812 (cbiG) | W | R | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | |

| LD813 (cbiG metE) | W | R | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | |

| LD814 (cysF) | R | R | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| LD817 (cysF metE) | R | R | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| LD816 (cysF cysG) | W | R | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | |

| LD818 (cysF cysG metE) | W | R | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | |

Growth was indicated by color (R, red; W, white) on MacConkey agar with 1% propanediol and 20 μM CoCl2 (Mac-PD) supplemented with 100 nM coenzyme B12 (B12) or with no supplement (0).

NCE-Glu, NCE minimal medium with 0.2% glucose; NCE-Gly, NCE medium with 0.4% glycerol. Supplements: 0, no supplement; Met, 0.0045% methionine; B12, 100 nM coenzyme B12; Cys, 0.0022% cysteine; Fum, 20 mM Na-fumarate.

Isolation of cysF mutants.

To isolate mutants that failed to synthesize any siroheme, strain LD810 (cysG::Tn10dTc) was mutagenized with transposon Tn10dCm and screened for mutants that required cysteine for growth. Among 59 cysteine auxotrophs, 21 mutants were defective in sulfite reduction and were corrected only by the addition of sulfide or cysteine to the medium. Nineteen of the associated mutations were likely to affect the cysIJ genes (the structural genes for siroheme synthase), since they conferred cysteine auxotrophy after transduction into a wild-type background. The other two insertion mutations conferred cysteine auxotrophy only in combination with a cysG mutation; in an otherwise wild-type background they resulted in no phenotype (Table 2). P1 transduction showed that the two mutations, termed cysF, were linked to the cysDNC operon, being 98% linked to the cysDN locus and ∼75% linked to the cysIJ locus.

Physical characterization of the cysF region.

A plasmid library was constructed from strain LD814 as described above. Plasmids were introduced into E. coli XL2-Gold-Kn (Stratagene), and transformants were screened for chloramphenicol resistance by replica plating. Plasmids were isolated from two chloramphenicol-resistant transformants (LD845 and LD846), and the sequences of their inserts adjoining the vector were determined. A contiguous sequence was constructed by primer walking from these clones. This sequence overlapped the sequence of pTAS6, which was isolated upon cloning a Tn10dCm in the cysD gene (21). The 1,416-bp cysF gene was located upstream of the cysD gene in the cysFDNC operon (Fig. 2B); the Tn10dCm in strain LD814 was located in the downstream portion of the cysF gene, after bp 1082. The corresponding cysDNC operon in E. coli does not contain a cysF gene (Fig. 2B). The region between the cysF and cysD genes, five bases, likely does not contain a promoter. Rather, the two cysF insertions we isolated appear to be nonpolar, the downstream cysDNC genes being expressed from the promoter driving the Tn10dCm-encoded cat gene. Other cysF insertions, including the Tn10LK insertion discussed below, are polar on the cysDNC genes and show the appropriate phenotypes (21).

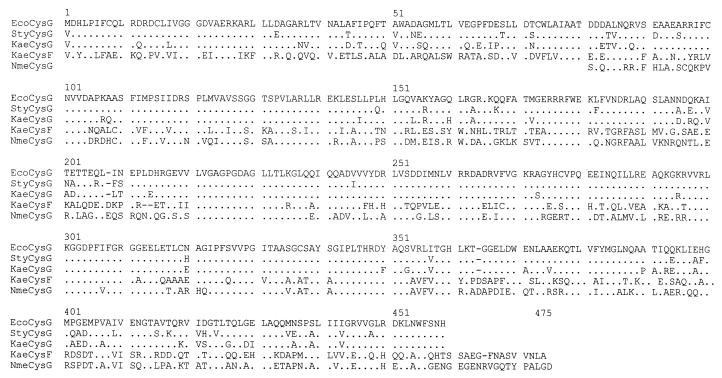

The CysF protein is 51% identical (60% similar) to the Klebsiella CysG protein over its entire length and has similarity to siroheme synthases from a variety of taxa; the sequence most similar to CysF (58% identical, 67% similar) is the siroheme synthase from Neisseria meningitidis (Fig. 3). Therefore, we predict that it encodes a bona fide siroheme synthase. Similarity to siroheme synthases extended over both domains of CysF, including the methylation domain (residues 217 to 475 in Fig. 3) and the iron chelation domain (residues 1 to 152 in Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Alignment of siroheme synthases. Periods, residues identical to those of the E. coli CysG protein; dashes, deleted residues. EcoCysG, E. coli CysG; StyCysG, S. enterica serovar Typhimurium CysG; KaeCysG, K, aerogenes CysG; KaeCysF, K. aerogenes CysF; NmeCysG, N. meningitidis siroheme synthase.

The roles of CysG- and CysF-produced siroheme.

Unlike cysG mutants, cysF mutants have no defect in B12 biosynthesis either aerobically or anaerobically (Table 2). Indeed cysF mutants have no discernible phenotype in an otherwise wild-type background. Although neither cysG nor cysF mutants conferred cysteine auxotrophy alone, the double mutant failed to reduce sulfite to sulfide (Table 2). These results suggest that cysF-encoded functions allow for siroheme biosynthesis via different mechanisms. If so, then NirBD should be able to use CysF-produced siroheme.

To test this hypothesis, we assayed the nitrite reductase activity of cysF and cysG mutants grown anaerobically with or without additional cysteine (Table 3). As expected, no aerobic nitrite reductase activity was observed (data not shown), and maximal anaerobic activity was observed when the nirBD operon was induced with nitrate (Table 3). cysF strains showed no consistent defect in anaerobic nitrite reductase activity, indicating that CysF-produced siroheme was not necessary for full NirBD activity. However, cysG mutants showed a significant reduction in nitrite reductase activity in media lacking cysteine and no appreciable nitrite reductase activity in the presence of cysteine. Since the addition of cysteine is expected to repress the cysF gene and deplete siroheme pools (see below), CysF-produced siroheme must be available to the NirBD nitrite reductase and must serve as an appropriate cofactor. No nitrite reductase activity was seen in cysF cysG double mutants, suggesting that the siroheme allowing NirBD activity in cysG mutants was provided by CysF.

TABLE 3.

Nitrite reductase activity of Klebsiella cys mutants

| Strain (genotype) | Nitrite reductase activity for cells grown ina:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSE-glucose-Met

|

NSE–glucose–Met–20 mM KNO3

|

|||

| − Cysteine | + Cysteine | − Cysteine | + Cysteine | |

| LD561 | 7.8 ± 0.7 | 6.4 ± 0.6 | 20.8 ± 0.5 | 42.1 ± 2.8 |

| LD814 (cysF) | 8.4 ± 0.5 | 5.6 ± 0.9 | 32.0 ± 1.4 | 55.4 ± 1.6 |

| LD810 (cysG) | 1.4 ± 0.9* | −1.5 ± 0.9* | 4.1 ± 0.8 | −0.1 ± 1.0* |

| LD816 (cysF cysG) | 0.6 ± 0.7* | −0.3 ± 0.9* | 1.0 ± 1.9* | 0.3 ± 1.4* |

Nitrite reductase activity is reported as nanomoles of nitrite consumed per minute per milligram of protein. Values are means ± standard deviations. ∗, not significantly greater than zero. Cells were grown anaerobically in NSE–glucose–0.0045% methionine; cysteine was added to 0.005% (+ cysteine). Cells were pregrown anaerobically in NSE-glucose-methionine.

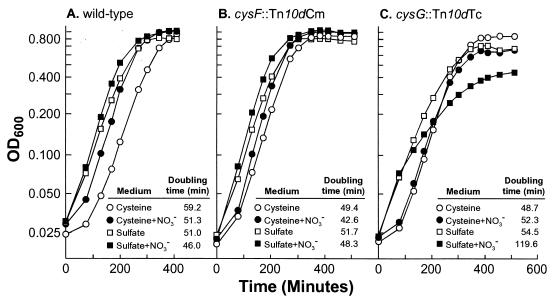

NirBD binding of CysF-produced siroheme may deplete siroheme pools in cysG mutants, thereby impeding the function of the CysIJ sulfite reductase. To examine this possibility, we assayed the growth of cysF and cysG mutants in minimal media (Fig. 4). Neither cysG nor cysF mutants had a significant growth defect when using sulfate as a sole sulfur source, demonstrating that an appropriate cofactor for CysIJ could be synthesized by either CysF or CysG. However, cysG mutants showed a growth defect when grown anaerobically in the presence of nitrate; this defect is almost entirely corrected by the addition of cysteine (Fig. 4). These results support the hypothesis that the NirBD enzyme will bind CysF-produced siroheme, thereby inducing a modest cysteine auxotrophy. We interpret the remaining growth defect of cysG mutants grown in cysteine-nitrate (the presence of nitrate results in a consistent, modestly slower growth rate rather than the reproducibly slightly faster growth rate conferred by nitrate respiration in wild-type and cysF strains) as inhibition caused by the accumulation of nitrite.

FIG. 4.

Growth curves of cysG and cysF mutants grown anaerobically in minimal media with glucose as a carbon source; sources of sulfur were added as indicated. (A) LD561. (B) LD814 (cysF). (C) LD810 (cysG). Doubling times were calculated from the slope of a line estimated from the linear range of log-transformed data; at least four data points were used, and the correlation coefficients ranged from 0.989 to 0.999.

Regulation of the cysF gene.

The location of the cysG gene downstream of the nirBD operon (Fig. 2A) suggests that it may be induced by nitrite under anaerobic growth conditions, as was demonstrated for the nirBD genes above; the presence of cysteine did not affect the levels of nitrite reductase in the cell (Table 3; Fig. 4). On the other hand, the location of the cysF gene within the cysFDNC operon suggests that it will be regulated by sulfur starvation by the CysB protein, analogous to the regulation of the cysDNC operon in E. coli. To test this hypothesis, we isolated Tn10LK insertions in cys genes; Tn10LK forms translational fusions to the lacZ reporter gene at the site of insertion (10). The Tn10LK insertion in strain LD844 creates a fusion after codon 132 of the CysF gene (Fig. 2B). Unlike the Tn10dCm insertions in the cysF gene described above, the Tn10LK insertion is polar on cysDNC and confers cysteine auxotrophy.

We examined the expression of the cysF::lacZ fusion when the cell was grown on cysteine (noninducing conditions) or on sulfite or methionine (inducing conditions) as a sole sulfur source. As expected, the cysFDNC operon was induced 8.6-fold when grown on sulfite as a sole sulfur source and 10.6-fold when grown on methionine as a poor sulfur source. These data demonstrate that sulfur starvation controls the expression of the cysFDNC genes, likely via a homologue of the CysB protein (8, 9, 21). Therefore, the cysF and cysG genes are regulated in a different fashion.

DISCUSSION

Alternative pathways for siroheme biosynthesis. The cysteine auxotrophy of cysF cysG double mutants and the prototrophy of each single mutant suggest that either protein can synthesize siroheme. The nitrate-induced CysG enzyme likely synthesizes siroheme for use in the NirBD nitrite reductase, and the cysteine-repressed CysF protein synthesizes siroheme for the CysIJ sulfite reductase. Upon induction with nitrate in a cysG mutant, the NirBD nitrite reductase depletes the pool of siroheme produced by the CysF protein, thereby inducing cysteine auxotrophy (Fig. 4). Consistent with this result, high-level expression of the CysIJ sulfite reductase in E. coli also requires increased siroheme production via a plasmid-borne cysG gene (29). In addition, NirBD nitrite reductase activity in a cysG mutant is dependent on CysF-produced siroheme (Table 3). These data support the hypothesis that both the CysF and CysG proteins synthesize siroheme and that CysIJ and NirBD both utilize this same cofactor. The sequence of the CysF protein aligns well with those of siroheme synthases, providing no evidence that it performs any additional biochemical function. Yet despite the similarities between CysF and CysG and each's ability to provide siroheme to NirBD or to CysIJ, the proteins appear to function in a different manner. That is, only the CysG protein can provide a methylated intermediate competent to enter the cobalamin biosynthetic pathway.

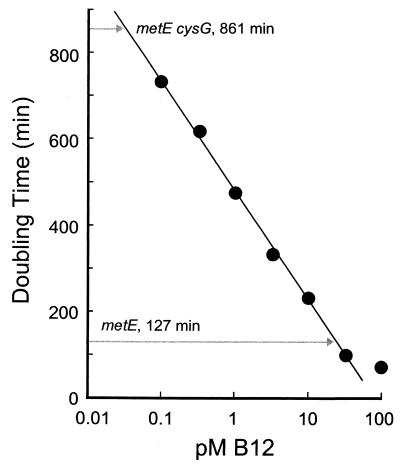

One explanation for this observation is that the CysF enzyme may bind its intermediates more tightly, reducing the flux of methylated intermediates into the cobalamin biosynthetic pathway. To estimate the amount of B12 synthesized in a cysG mutant, we examined the growth rate of a metE cbiG mutant when provided with limiting amounts of B12 (Fig. 5). The metE mutation makes the cell reliant on the B12-dependent MetH enzyme for methionine synthesis, and the cbiG insertion eliminates de novo B12 biosynthetic capability. In minimal medium, the growth rate is correlated to the amount of available B12, and the relationship between extracellular B12 concentration and growth rate is robust (Fig. 5; r2 = 0.998). If we assume that the relationship between extracellular and intracellular B12 concentrations is at best linear, we can use this relationship to predict the maximal amount of B12 produced by a cysG mutant (corresponding to 0.011 pM extracellular) relative to that produced by an otherwise wild-type cell (corresponding to 20 pM extracellular). These results suggest that cysG mutants could allow for the biosynthesis of 1,000-fold less B12 than a cysG+ cell. More specifically, the fully induced amount of CysF protein would release 1,000-fold-less methylated intermediate competent for B12 biosynthesis than the uninduced amount of CysG protein. Yet the growth yield of metE cysG mutants (maximal OD of 0.250 after 5 days) is comparable to that of a metE cbiG mutant and far lower than that of metE cbiG mutants (maximal OD of 0.850 after 4 days) that were provided with the amount of B12 (0.01 pM) that supports a similar growth rate. These data imply that very little, if any, B12 is synthesized in cysG mutants, and the scant growth we initially observe may be attributed to the depletion of internal methionine stores.

FIG. 5.

Growth rate of LD813(metE cbiG) grown anaerobically in E medium plus glucose and the indicated amounts of cyanocobalamin (B12). The anaerobic growth rates for LD807 (metE) and LD811 (metE cysG) were 127 and 816 min, respectively, in E medium plus glucose.

Although the CysF enzyme may merely bind its intermediates more tightly, the very tight growth phenotype of cysG mutants belies this scenario. Alternatively, it is possible that the CysF- and CysG-catalyzed reactions use different routes to synthesize siroheme from Uro-III. Siroheme synthesis requires four modifications of Uro-III: two methylations, oxidation, and iron insertion (Fig. 1). The CysG protein performs the two methylation reactions first, making the intermediate tetrapyrrole (dihydrosirohydrochlorin) available as a substrate for B12 biosynthesis (4, 24, 27, 28). We postulate that the CysF protein may first reduce, or insert iron into, Uro-III thereby preventing its flux into the B12 biosynthetic pathway; alternatively, the CysF protein may perform only a single methylation, which may yield a product capable of functioning in NirBD but not competent for B12 biosynthesis. The modular nature of siroheme synthetases allows for either alternative.

Why alternative routes?

Methylation of Uro-III serves to divert tetrapyrroles from heme synthesis (hemes a, b, c, d, and o in enteric bacteria) into pathways for making either siroheme or coenzyme B12 (Fig. 1). Hence, the combined action of the CysF and CysG enzymes regulates the relative pools of three separate cofactors. Yet siroheme is used for two entirely different purposes in the cell, the assimilatory reduction of sulfite and the dissimilatory reduction of nitrite. Therefore, alternative enzymes for siroheme biosynthesis would contribute to more-efficient regulation of tetrapyrrole biosynthesis in Klebsiella. In addition, the synthesis of coenzyme B12 represents yet a third destination for methylated Uro-III, whose biosynthesis would decrease potential pools of siroheme. Since the CysF-catalyzed pathway does not provide large amounts of intermediates competent for B12 biosynthesis, the production of siroheme via the CysF protein would be unaffected by B12 biosynthesis and vice versa. On the other hand, the induction of B12 biosynthesis would affect CysG-catalyzed siroheme pools and vice versa, as CysG-generated intermediates can be shunted into the B12 biosynthetic pathway. The CysF protein may allow for more-consistent production of siroheme for the CysIJ protein.

Why was the cysF gene lost from the ancestor of E. coli and Salmonella?

It is likely that the presence of the cysF gene in Klebsiella and its absence from E. coli and Salmonella represent a loss from the ancestor of the latter two bacteria rather than a gain into the Klebsiella lineage. Neither the character of the cysF gene nor its position within the cysFDNC operon is consistent with sequence features indicative of recent horizontal genetic transfer (12, 13). If the CysF protein served such an important role in siroheme biosynthesis, why was it lost from the ancestor of E. coli and Salmonella? Although both Klebsiella and Salmonella synthesize coenzyme B12, this capability was lost from the ancestor of E. coli and Salmonella and was recently regained in the Salmonella lineage (14, 15). Without B12 biosynthesis, the constitutive expression of the cysG gene may have been sufficient to provide siroheme for CysIJ in the ancestor of E. coli and Salmonella. In this scenario, the cysF gene would have provided an insufficiently important function to be maintained and was lost. In this way, the loss of B12 biosynthesis could have resulted in the indirect loss of the cysF gene in the ancestor of E. coli and Salmonella. Testing this model awaits further examination of cysF genes in enteric bacteria.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank R. Bender for providing strains and useful advice and T. Seiflein for providing strains and plasmid pTAS1. We thank R. Kadner for many helpful comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Vries G E, Raymond C K, Ludwig R A. Extension of bacteriophage λ host range: selection, cloning, and characterization of a constitutive λ receptor gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:6080–6084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.19.6080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fazzio T G, Roth J R. Evidence that the CysG protein catalyzes the first reaction specific to B12 synthesis in Salmonella typhimurium: insertion of cobalt. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6952–6959. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6952-6959.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldberg R B, Bender R A, Streicher S L. Direct selection for P1-sensitive mutants of enteric bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1974;118:810–814. doi: 10.1128/jb.118.3.810-814.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldman B S, Roth J R. Genetic structure and regulation of the cysG gene in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1457–1466. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.5.1457-1466.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeter R M, Olivera B M, Roth J R. Salmonella typhimurium synthesizes cobalamin (vitamin B12) de novo under anaerobic growth conditions. J Bacteriol. 1984;159:206–213. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.1.206-213.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones-Mortimer M C. Positive control of sulfate reduction in Escherichia coli: isolation, characterization and mapping of cysteineless mutants of E. coli K12. Biochem J. 1968;110:589–595. doi: 10.1042/bj1100589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones-Mortimer M C. Positive control of sulfate reduction in Escherichia coli: the nature of the pleiotropic cysteineless mutants of E. coli K12. Biochem J. 1968;110:597–602. doi: 10.1042/bj1100597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kleckner N, Bender J, Gottesman S. Uses of transposons with emphasis on Tn10. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:139–180. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04009-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kredich N. Biosynthesis of cysteine. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 514–527. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawrence J G, Ochman H. Amelioration of bacterial genomes: rates of change and exchange. J Mol Evol. 1997;44:383–397. doi: 10.1007/pl00006158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawrence J G, Ochman H. Molecular archaeology of the Escherichia coli genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9413–9417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawrence J G, Roth J R. The cobalamin (coenzyme B12) biosynthetic genes of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6371–6380. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6371-6380.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawrence J G, Roth J R. Evolution of coenzyme B12 synthesis among enteric bacteria: evidence for loss and reacquisition of a multigene complex. Genetics. 1996;142:11–24. doi: 10.1093/genetics/142.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacDonald H, Cole J. Molecular cloning and functional analysis of the cysG and nirB genes of Escherichia coli K12, two closely-linked genes required for NADH-dependent nitrite reductase activity. Mol Gen Genet. 1985;200:320–334. doi: 10.1007/BF00425444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peakman T, Crouzet J, Mayaux J F, Busby S, Harborne N, Wootton J, Nicolson R, Cole J. Nucleotide sequence, organisation and structural analysis of the products of genes in the nirB-cysG region of the Escherichia coli K12 chromosome. Eur J Biochem. 1990;191:315–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raux E, Thermes C, Heathcote P, Rambach A, Warren M J. A role for Salmonella typhimurium cbiK in cobalamin (vitamin B12) and siroheme biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3202–3212. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3202-3212.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roth J R, Lawrence J G, Rubenfield M, Kieffer-Higgins S, Church G M. Characterization of the cobalamin (vitamin B12) biosynthetic genes of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3303–3316. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3303-3316.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seiflein T A, Lawrence J G. Methionine-to-cysteine recycling in Klebsiella aerogenes. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:336–346. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.1.336-346.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siegel L M, Murphy M J, Kamin H. Reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate-sulfite reductase of Enterobacteria. I. The Escherichia coli hemoflavoprotein: molecular parameters and prosthetic groups. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:251–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Snell F D, Snell C T. Colorimetric methods of analysis. II. New York, N.Y: Van Nostrand; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spencer J B, Stolowich N J, Roessner C A, Scott A I. The Escherichia coli cysG gene encodes the multifunctional protein, siroheme synthase. FEBS Lett. 1993;335:57–60. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80438-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas D, Surdin-Kerjan Y. Metabolism of sulphur amino acids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:503–532. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.4.503-532.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vogel H J, Bonner D M. Acetylornithase of Escherichia coli: partial purification and some properties. J Biol Chem. 1956;218:97–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warren M J, Bolt E L, Roessner C A, Scott A I, Spencer J B, Woodcock S C. Gene dissection demonstrates that the Escherichia coli cysG gene encodes a multifunctional protein. Biochem J. 1994;302:837–844. doi: 10.1042/bj3020837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Warren M J, Roessner C A, Santeander P J, Scott A I. The Escherichia coli cysG gene encodes S-adenosylmethionine-dependent uroporphyrinogen III methylase. Biochem J. 1990;265:725–729. doi: 10.1042/bj2650725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu J-Y, Siegel L M, Kredich N M. High-level expression of Escherichia coli NADPH-sulfite reductase: requirement for a cloned cysG plasmid to overcome limiting siroheme cofactor. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:325–333. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.1.325-333.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]