Abstract

Recent advances in the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) have led to improved patient outcomes. Multiple PAH therapies are now available and optimising the use of these drugs in clinical practice is vital. In this review, we discuss the management of PAH patients in the context of current treatment guidelines and supporting clinical evidence. In clinical practice, considerable emphasis is placed on the importance of making treatment decisions guided by each patient's risk status, which should be assessed using multiple prognostic parameters. As PAH is a progressive disease, regular assessments are essential to ensure that any change in risk is detected in a timely manner and treatment is adjusted accordingly. With the availability of therapies that target three different pathogenic pathways, combination therapy is now the standard of care. For most patients, this involves dual combination therapy with agents targeting the endothelin and nitric oxide pathways. Therapies targeting the prostacyclin pathway should be added for patients receiving dual combination therapy who do not achieve a low-risk status. There is also a need for a holistic approach to treatment beyond pharmacological therapies. Implementation of all these approaches will ensure that PAH patients receive maximal benefit from currently available therapies.

Short abstract

Optimal PAH treatment requires frequent multiparameter risk assessment and early initiation of combination therapy http://ow.ly/IA6t30fPceT

Introduction

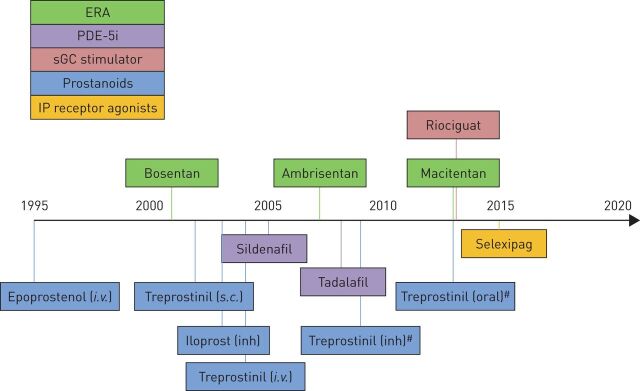

The past decade has seen significant progress in the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). A number of novel targeted therapies have been developed, providing important additions to the existing PAH armamentarium (figure 1) [1]. Furthermore, several event-driven trials have demonstrated that PAH therapies can provide long-term benefits for patients [6–8]. Beyond medication, improvements in nonpharmacological treatments and the development of updated diagnosis and treatment guidelines may further improve outcomes in clinical practice [9, 10].

FIGURE 1.

Timeline of approval of therapies for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Therapies that are approved in the USA and/or European Union (EU) are included, positioned on the timeline based on the first date of their approval in either USA [2–4] or EU [5]. Therapies are administered orally unless otherwise indicated. ERA: endothelin receptor antagonist; PDE-5i: phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor; sGC: soluble guanylate cyclase; inh: inhaled. #: not approved in the EU.

Despite these recent advances, PAH ultimately remains a fatal disease [11]. Efforts to slow disease progression are essential and research is ongoing to develop therapies with novel modes of action [12]. However, based on their current development status, approval of new drugs targeting novel pathways is not expected in the near future. Therefore, it is crucial that currently available treatment options are used to their full potential and that the most effective treatment strategy is implemented for each patient.

In this article, we discuss how best to manage PAH in the current treatment era, including the role of risk assessment and the timely and appropriate use of combination therapy.

Role of risk assessment in PAH

Why and how do we assess risk?

Ensuring optimal outcomes for PAH patients requires the selection of an appropriate initial treatment regimen after diagnosis. Patients should then be closely monitored and treatment escalated as clinically indicated. The concept of goal-oriented therapy in PAH has been in place for a number of years. More recently, this has evolved into a risk-based approach and the current European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) guidelines recommend that treatment decisions should be guided by comprehensive, multiparameter risk assessments [9, 10].

Functional class is a powerful predictor of outcome in PAH [13] and achievement of World Health Organization functional class (WHO FC) I–II status is an important treatment goal [9, 10]. Despite this, many patients in WHO FC II continue to experience disease progression and early death. This is illustrated in an analysis from the French registry, which reported that almost 20% of patients categorised as WHO FC II at baseline died during 3 years of follow-up [13]. Furthermore, in several trials with PAH therapies, a number of WHO FC I/II patients experienced disease progression during the studies [6–8, 14].

Instead of using individual indicators of prognosis, such as WHO FC, it is now widely accepted that a patient's risk of clinical deterioration or mortality should be determined by a multiparameter risk assessment. To aid this process, the guidelines provide a table of risk determinants, selected based on their prognostic relevance [9, 10, 15]. These include progression of symptoms, WHO FC, measures of exercise capacity, haemodynamic parameters and other indicators of right ventricular (RV) function [9, 10]. Based on these determinants, the risk status of each patient can be categorised as either low, intermediate or high, corresponding to an estimated 1-year mortality of <5%, 5–10% or >10%, respectively [9, 10]. Although performing a structured risk assessment is crucial, clinical gestalt also has a valuable role and it is essential that all available prognostic information, such as PAH aetiology, sex, age, time from diagnosis and relevant comorbidities, is taken into consideration.

As stated in the ESC/ERS guidelines, the ultimate aim of therapy for PAH patients is to achieve a low-risk status [9, 10]. This aim has recently been validated in survival analyses of patients enrolled in three European registries. A study from the COMPERA registry evaluated survival of newly diagnosed PAH patients according to their risk status, determined using an abbreviated version of the risk assessment strategy proposed by the guidelines. For patients in the low- and intermediate-risk cohorts, the observed mortality rates 1 year after diagnosis were 2.8% and 9.9%, respectively. This was compared with 21.2% in the high-risk cohort [16]. The Swedish PAH register study evaluated newly diagnosed patients who initiated PAH therapies and who had a multiparameter risk assessment performed both at baseline and at a follow-up assessment (median 4 months after baseline) [17]. For patients categorised as low risk at baseline and at follow-up, the 3-year survival rate was 98%. In contrast, for patients who were in the intermediate- or high-risk categories at baseline and remained in these groups at follow-up, the 3-year survival rate was only 68% [17]. A study from the French registry demonstrated clearly that in order to achieve a better long-term prognosis, patients need to have as many parameters as possible in the low-risk category. In this study, PAH patients who achieved only one or two low-risk criteria during the first year of PAH treatment had worse outcomes than those who achieved three or four low-risk criteria [18].

The importance of regular risk assessment

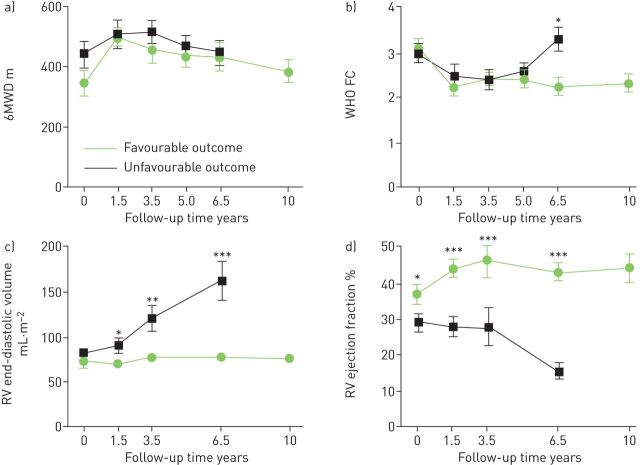

Achievement or maintenance of a low-risk status is reassuring; however, it is vital that physicians remain vigilant, as pathological changes within the pulmonary vasculature and RV can still occur even if no signs of clinical deterioration are apparent [19]. This has been illustrated in a study by Van de Veerdonk et al. [20], which evaluated clinical, haemodynamic and RV changes in a cohort of patients who experienced disease progression resulting in death or lung transplantation after ≥5 years of clinical stability. In this study, disease progression was preceded by changes in RV structure and function, but not by changes in WHO FC, exercise capacity and haemodynamics (figure 2), suggesting that an apparently clinically stable profile may mask the development of RV failure [20].

FIGURE 2.

Disease progression is preceded by right ventricular remodelling, but not by changes in clinical parameters. Changes in a) 6-min walking distance (6MWD), b) World Health Organization functional class (WHO FC), c) right ventricular (RV) end-diastolic volume and d) RV ejection fraction were assessed over a 10-year period for patients who were alive and transplant-free 10 years after inclusion in the study (favourable outcome, n=12) and for patients who died or required lung transplantation between 5 and 10 years after inclusion in the study (unfavourable outcome, n=10). Data are presented as mean±sem. *: p<0.05; **: p<0.01; ***: p<0.001 between groups. Reproduced and modified from [20] with permission.

Given that pathological changes are likely to be ongoing in all PAH patients, the term “stable” may not be appropriate, even for patients in the low-risk category. As all PAH patients have poor tolerance to acute situations, for example minor surgery or infections such as pneumonia, they can never be considered truly stable. Physicians should be aware that the patient's underlying condition may worsen as a result of disturbances in the status quo. As such, a patient's treatment regimen may need to be augmented during episodes of illness or other acute situations.

For all patients, including those categorised as low risk, it is essential that regular and frequent risk assessments are performed to ensure that any change in risk status, or changes in individual parameters, are detected at the earliest opportunity. Any parameters that deteriorate from low to intermediate risk should raise suspicion and prompt the treating physician to consider whether escalation of treatment is required.

Combination therapy for optimal PAH management

Although each patient's treatment strategy should be guided by their level of risk, it is becoming increasingly apparent that the benefits of combination therapy to target multiple pathological pathways should be offered to all PAH patients [21]. There is clear evidence that combination therapy is effective in PAH [6–8], and this strategy now forms an integral part of the treatment algorithm in the ESC/ERS guidelines [9, 10]. In order to ensure the best outcome for patients, it is important to consider how combination therapy can be optimised in clinical practice, both in terms of which therapies to combine and when to initiate combination therapy.

Dual combination therapy: targeting the endothelin and nitric oxide pathways

Dual combination therapy with an endothelin receptor antagonist (ERA) and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor (PDE-5i) has been shown to improve long-term outcomes in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in patients with PAH [6, 8]. In the AMBITION study, the risk of clinical failure events was reduced by 50% in newly diagnosed, treatment-naïve PAH patients treated with initial ambrisentan and tadalafil combination therapy compared with pooled monotherapy [8]. The SERAPHIN study provided an opportunity to evaluate the benefits of combination therapy in a long-term RCT. In this study, 64% of patients were receiving a PAH therapy at baseline, 96% of whom were receiving a PDE-5i. Among patients receiving background therapy, addition of macitentan significantly reduced the risk of morbidity/mortality events by 38% compared with placebo [6]. Furthermore, post hoc evaluation of newly diagnosed patients, including those with and without background therapy, showed a 57% risk reduction with macitentan treatment versus placebo [22]. In addition to the RCT data, a retrospective analysis of real-world data by Sitbon et al. [23] showed that initial combination therapy with an ERA and a PDE-5i was associated with significant improvements in WHO FC, exercise capacity and haemodynamics from baseline to month 4.

These data illustrate the benefits of dual combination therapy targeting the endothelin and nitric oxide (NO) pathways and raise the question whether it is ever appropriate for a PAH patient to be treated with monotherapy. From our clinical experience, there are exceptions where certain patients may be candidates for treatment with monotherapy, as determined by clinical status and discussions between the physician and patient. Furthermore, monotherapy may also be prescribed in low-risk patients if the use of an ERA or a PDE-5i/soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) stimulator is contraindicated or is not tolerated. However, caution is required when taking this approach: even if such a patient shows an adequate response on initial monotherapy, the patient must be monitored closely and initiated on combination therapy as soon as clinically indicated.

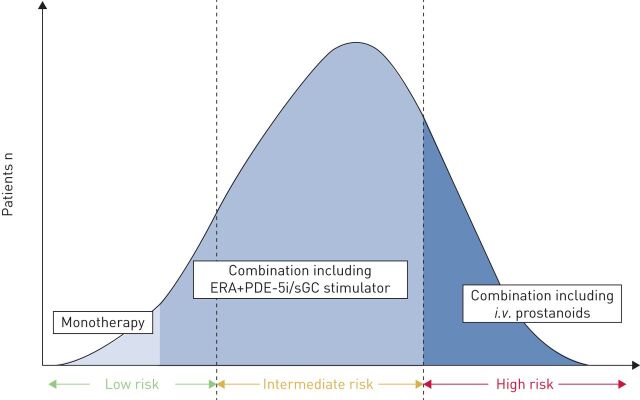

Given the clear benefits of dual combination therapy to target the endothelin and NO pathways, in the current treatment era it is generally accepted that the vast majority of PAH patients who are at low or intermediate risk at diagnosis should receive dual combination therapy with an ERA and a PDE-5i, either in an initial or rapid sequential manner (figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Initial management of pulmonary arterial hypertension in the current era. Based on our clinical experience, the majority of patients in the low- and intermediate-risk categories should be started on dual therapy with an endothelin receptor antagonist (ERA) plus a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor (PDE-5i) or soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) stimulator. A small proportion of patients in the low-risk category may be suitable for monotherapy. For all patients who are in the high-risk category, combination therapy including an i.v. prostanoid is required.

When to add a therapy targeting the prostacyclin pathway

For more than two decades, it has been possible to manage PAH by targeting a third well-characterised pathogenic pathway: the prostacyclin (PGI2) pathway (figure 1). Of note, a synthetic PGI2 (epoprostenol) was the first PAH therapy to be approved and is still considered to be the gold-standard treatment for PAH [24]. For patients in WHO FC IV, epoprostenol is the only therapy with class I recommendation and evidence level of A (the highest available according to the ESC/ERS guidelines) [9, 10]. Therapies targeting the PGI2 pathway with alternative routes of administration, including oral, are now available and are recommended for the treatment of patients in WHO FC II and III [9, 10].

In the current era, therapies targeting the PGI2 pathway are rarely used as monotherapy and instead are more typically used in combination regimens. The choice and timing of initiation of PGI2-targeting therapies should be guided by risk assessment, as discussed later.

Combination therapy including an oral therapy that targets the PGI2 pathway

In the past, targeting the PGI2 pathway was generally only an option for patients with severe disease, as it necessitated the use of complex routes of administration via continuous i.v. or s.c. infusion [9, 10, 21, 25]. The subsequent availability of inhaled prostanoid therapies allowed the PGI2 pathway to be addressed without requiring i.v. or s.c. access [25]. However, the need for frequent administration and the length of time involved in administering these therapies may affect patient compliance [25, 26].

The approval of oral therapies that target the PGI2 pathway (figure 1) represented a significant advance in the management of PAH, as it allowed activation of PGI2 signalling by agents with a more convenient route of administration. While the systemic safety profile for oral therapies that target the PGI2 pathway is similar to that of i.v., s.c. and inhaled prostanoids, safety issues related to the route of administration, such as catheter-related infections, are eliminated [27]. As a result, the earlier use of oral therapies targeting the PGI2 pathway as part of a combination therapy regimen has become an attractive option.

RCTs have been conducted to evaluate the use of oral therapies that target the PGI2 pathway as part of a combination therapy regimen [7, 28, 29]. In the FREEDOM-C and FREEDOM-C2 studies, no significant improvements in exercise capacity (primary end-point) were observed following treatment with oral treprostinil compared with placebo, among patients receiving background ERA and/or PDE-5i therapy [28, 29]. Additional trials to further investigate the use of oral treprostinil as combination therapy are planned and ongoing [30, 31]. Selexipag, a selective prostacyclin receptor agonist, is the only oral therapy targeting the PGI2 pathway that has been shown to improve long-term outcomes in an RCT (GRIPHON) [7]. In this study, selexipag reduced the risk of morbidity/mortality events by 40% versus placebo [7]. This result was consistent across patients, irrespective of WHO FC and PAH therapy at baseline [7]. In addition, a significant placebo-corrected treatment effect of selexipag on 6-min walking distance (6MWD) at week 26 was also found (+12 m, p=0.003), although the magnitude of this treatment effect was modest. This modest response may reflect the extent of imputed data and the strict imputation rules in GRIPHON, as well as the study population, which included a high proportion of patients receiving background PAH therapies and a large number of patients in WHO FC II [7]; improvements in 6MWD may be difficult to achieve in such patients. The data from GRIPHON support the use of selexipag to delay disease progression in PAH patients, including those in WHO FC II and those receiving dual ERA and PDE-5i background therapy, making them the first RCT data to demonstrate the benefits of triple combination therapy in PAH patients.

In the clinic, the decision about when to initiate triple oral combination therapy should be guided by multiparameter risk assessment. If a patient on dual combination therapy with an ERA and a PDE-5i/sGC stimulator fails to achieve or maintain a low-risk status, they should be given an oral therapy to target the PGI2 pathway without delay. In some cases, for example patients with a significant deterioration in haemodynamic parameters, parenteral prostanoid therapy may be required instead of oral therapy to target the PGI2 pathway. The decision on which approach is the most appropriate should be made on an individual patient basis, relying on the physician's judgement. What is clear is that all low- or intermediate-risk patients must be monitored carefully and the decision to initiate parenteral prostanoids should be taken before they have deteriorated to the high-risk category.

Initiation of triple sequential oral combination therapy may be considered for certain patients with a low-risk profile [9, 10]. This treatment approach may be particularly appropriate for patients who are deemed low risk according to the ESC/ERS guidelines risk stratification table, but who have additional phenotypic characteristics or comorbidities that convey a poor prognosis, for example, older patients or individuals with connective tissue disease [32, 33].

As PAH is a progressive disease, there is a rationale for targeting all three pathogenic pathways immediately upon diagnosis with initial triple combination therapy in order to delay the remodelling of the pulmonary vasculature, which occurs even in the early stages of the disease [19]. At present, the benefits of initial triple oral combination therapy compared with initial dual oral combination therapy are unknown, but are the focus of the ongoing TRITON RCT [34].

Combination therapy including a parenteral prostanoid

A crucial aspect of PAH management is the effective use of i.v. and s.c. prostanoids in patients with severe disease. Despite the known benefits of parenteral prostanoids, in clinical practice they have been underused [35, 36]. A recent single-centre study indicated that this may not necessarily be the case in expert PAH centres [37], highlighting the importance of patient referral to, and co-management with, expert centres.

According to the current guidelines, i.v. prostanoids should be included in combination therapy for high-risk, incident patients [9, 10]. This is supported by evidence from a retrospective study, which reported that significant improvements from baseline were observed in 6MWD and haemodynamics after 4 months of treatment with initial epoprostenol, bosentan and sildenafil [38]. Furthermore, 89% of patients improved from WHO FC III/IV to WHO FC I/II [38]. The beneficial effects were maintained during long-term follow-up (1–3 years) and the survival rate was 100% after 3 years [38].

For a prevalent patient who is already receiving triple oral combination therapy, the ESC/ERS guidelines are less definitive about when parenteral prostanoid therapy should be initiated. In our opinion, initiation of parenteral prostanoids is warranted in prevalent patients who are in the intermediate-risk category and who are not improving on triple oral combination therapy. As mentioned, patients who fail to achieve or maintain a low-risk status while receiving dual ERA and PDE-5i/sGC stimulator combination therapy may be given parenteral rather than oral therapy to target the PGI2 pathway. Careful monitoring of all patients is necessary to ensure that initiation of parenteral therapy is based on the individual patient's needs.

Additionally, the choice of when to initiate parenteral prostanoids must take into account patient preference; patients may be reluctant to take i.v. or s.c. prostanoids due to their routes of administration, and this may contribute to their underuse [25, 35, 36]. To address this, it is imperative to educate the patient on the benefits of parenteral prostanoids, and to support them throughout the process [25, 39]. Practical considerations regarding the use of prostanoids have been reviewed in detail [25].

Considerations beyond PAH-specific pharmacological therapy

As improved management of PAH has led to increased patient longevity, there is now a greater need to focus on all aspects of patients’ lives. As such, a holistic approach that considers the whole patient, including physical, mental and social well-being is a central component of effective PAH management [39, 40].

It is important to ensure that patients are proactively involved with their self-care. This topic has been reviewed by Graarup et al. [39], who highlighted that engaged patients who understand their disease and treatment options have enhanced quality of life and well-being. Psychosocial support through patient associations, education and greater involvement of family and friends can all benefit the patient [39].

Lifestyle modifications should also play a central role in patient management. Exercise-based rehabilitation can lead to improvements in exercise capacity and quality of life [41–45]. According to the ESC/ERS guidelines, exercise training should be implemented by specialist PAH centres for patients who appear to be clinically stable and are receiving appropriate pharmacological therapy [9, 10]. If it is not feasible for a patient to join a formal exercise rehabilitation programme, they should be encouraged to undertake low-level aerobic exercise at home, within symptom limits. Isometric exercise is not recommended, as it may result in syncope [46]. In addition to exercise, there are several dietary considerations for patients with PAH. Iron deficiency may occur [47–49], in which case iron supplementation should be considered [9, 10]. There is a lack of controlled data in this area; however, an ongoing phase-II RCT is investigating the clinical benefits of a single high dose of iron in patients with PAH [50]. In addition, vitamin D concentrations are reduced in PAH patients [51] and uncontrolled data indicate that vitamin D replacement therapy improves RV size and exercise capacity in vitamin D deficient patients with pulmonary hypertension [52]. Finally, PAH patients, especially those with RV failure, should follow a sodium-restricted diet to prevent additional water retention [46].

In addition to gaining general health benefits, a patient who makes lifestyle changes early in the course of their disease is more likely to be a suitable candidate for lung transplantation if needed. For example, obese patients may be ineligible for lung transplantation [53], and so the importance of weight loss must be discussed at an early stage of disease.

Use of appropriate supportive therapy should be considered [9, 10]. Anticoagulants are widely used in PAH patients in clinical practice [54]. However, recent registry and RCT data have provided conflicting results regarding the benefits of anticoagulant use in PAH [54, 55]. Although the current ESC/ERS guidelines state that anticoagulant therapies may be considered in patients with idiopathic PAH, heritable PAH and PAH due to use of anorexigens, the level of evidence to support this has been downgraded compared with that in earlier guidelines [9, 10, 56]. Oedema as a consequence of right heart failure is a common occurrence in PAH patients [9, 10] and every attempt should be made to manage fluid overload initially, while PAH therapies are being considered. In addition, aldosterone antagonists may be beneficial in PAH patients with RV failure, not only because of their diuretic activity, but also because aldosterone may play a role in cardiopulmonary remodelling and dysfunction [57]. As such, aldosterone antagonists are now in use in clinical practice in PAH despite a lack of supporting RCT evidence [46].

Patients with PAH who are seen in clinical practice today are generally older and have more comorbidities than those in the past [58–60]. The impact of comorbidities on disease management must therefore be considered.

Finally, the importance of management in an expert centre cannot be overstated. PAH is a complex disease and patients require the care of a multidisciplinary team, including PAH specialist doctors and nurses, and providers of psychological and social support [9, 10].

Future perspectives: managing transitions

The development of therapies with novel modes of action and/or more convenient routes of administration has increased the number of treatment options available to physicians and patients. Although these novel agents target the same pathogenic pathways as existing therapies, in clinical practice there may be reasons to consider a transition from an existing therapy to another agent. For example, patients who are on an inhaled prostanoid may request to switch to an oral therapy targeting the PGI2 pathway. This transition is supported by the prospective, open-label TRANSIT-1 study, which showed that 94% of patients had switched from inhaled treprostinil to selexipag by the end of the 16-week study period [61]. Additional data are emerging from clinical practice and there is growing experience with managing this transition in the clinic. Patients receiving parenteral prostanoid therapy may request to switch to an oral drug and limited data from short-term studies on this approach are beginning to emerge [61–67]. Validation of this approach in RCTs will be required before it can be recommended. It is not yet well established whether there is a role for switching between PDE-5is and sGC stimulators in patients who are not responding to one type of drug. A trial investigating this has recently been completed and another is ongoing [68, 69]. In general, data to support transitions from one agent to another are currently limited, but we anticipate the potential benefits and risks to be better understood as this experience grows.

Conclusions

Patients with PAH require an individualised treatment strategy that is tailored to their risk status and which makes the best use of available combinations of targeted therapies. A holistic approach to management should be used and patients should be cared for by a multidisciplinary team who are able to implement both pharmacological therapy and supportive care. Due to the progressive nature of the disease, all patients must be closely monitored and their treatment regimen escalated according to clinical need without delay. By implementing these approaches, patient management can be optimised to ensure the best possible outcome for all patients with PAH.

Disclosures

S. Gaine ERR-0095-2017_Gaine (1.2MB, pdf)

V. McLaughlin ERR-0095-2017_McLaughlin (1.2MB, pdf)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Sarah Bulman (nspm Ltd, Meggen, Switzerland) for medical writing assistance, funded by Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd (Allschwil, Switzerland).

Footnotes

Support statement: Funding was received from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Allschwil, Switzerland. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

Conflict of interest: Disclosures can be found alongside this article at err.ersjournals.com

Provenance: Publication of this peer-reviewed article was sponsored by Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Allschwil, Switzerland (principal sponsor, European Respiratory Review issue 146).

References

- 1.Humbert M, Lau EM, Montani D, et al. Advances in therapeutic interventions for patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 2014; 130: 2189–2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). FDA Approved Drug Products. www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/ Date last accessed: August 2017. Date last updated: August 2017.

- 3.United Therapeutics. United Therapeutics Receives FDA Approval for REMODULIN™ to Treat Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1082554/000095013302002150/w61118exv99.htm Date last accessed: August 2017. Date last updated: May 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.United Therapeutics. FDA Approves Intravenous Dosing of REMODULIN® for the Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. http://files.shareholder.com/downloads/UTHR/4970422123×0×63346/159F2EED-98E5-45E4-B273-604034727ABA/63346.pdf Date last accessed: August 2017. Date last updated: November 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Medicines Agency. European Public Assessment Reports.www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/landing/epar_search.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124 Date last accessed: August 2017. Date last updated: August 2017.

- 6.Pulido T, Adzerikho I, Channick R, et al. Macitentan and morbidity and mortality in pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 809–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sitbon O, Channick R, Chin KM, et al. Selexipag for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 2522–2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galiè N, Barberà JA, Frost AE, et al. Initial use of ambrisentan plus tadalafil in pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 834–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Respir J 2015; 46: 903–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Heart J 2016; 37: 67–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farber HW, Miller DP, Poms AD, et al. Five-year outcomes of patients enrolled in the REVEAL registry. Chest 2015; 148: 1043–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simonneau G, Hoeper MM, McLaughlin V, et al. Future perspectives in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir Rev 2016; 25: 381–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Humbert M, Sitbon O, Chaouat A, et al. Survival in patients with idiopathic, familial, and anorexigen-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension in the modern management era. Circulation 2010; 122: 156–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Channick RN, Delcroix M, Galié N, et al. The effect of macitentan on long-term outcomes in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension by WHO functional class: data from the randomized controlled SERAPHIN study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 189: A4783. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raina A, Humbert M. Risk assessment in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir Rev 2016; 25: 390–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoeper MM, Kramer T, Pan Z, et al. Mortality in pulmonary arterial hypertension: prediction by the 2015 European pulmonary hypertension guidelines risk stratification model. Eur Respir J 2017; 50: 1700740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kylhammar D, Kjellström B, Hjalmarsson C, et al. A comprehensive risk stratification at early follow-up determines prognosis in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J 2017; in press [ 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx257]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boucly A, Weatherald J, Savale L, et al. Risk assessment, prognosis and guideline implementation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2017; 50: 1700889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Austin ED, Kawut SM, Gladwin MT, et al. Pulmonary hypertension: NHLBI Workshop on the Primary Prevention of Chronic Lung Diseases. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014; 11: Suppl. 3, S178–S185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van de Veerdonk MC, Marcus JT, Westerhof N, et al. Signs of right ventricular deterioration in clinically stable patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest 2015; 147: 1063–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sitbon O, Gaine S. Beyond a single pathway: combination therapy in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir Rev 2016; 25: 408–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simonneau G, Channick R, Delcroix M, et al. Incident and prevalent cohorts with pulmonary arterial hypertension: insight from SERAPHIN. Eur Respir J 2015; 46: 1711–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sitbon O, Sattler C, Bertoletti L, et al. Initial dual oral combination therapy in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2016; 47: 1727–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sitbon O, Vonk Noordegraaf A. Epoprostenol and pulmonary arterial hypertension: 20 years of clinical experience. Eur Respir Rev 2017; 26: 160055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farber HW, Gin-Sing W. Practical considerations for therapies targeting the prostacyclin pathway. Eur Respir Rev 2016; 25: 418–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McLaughlin VV. Medical management of primary pulmonary hypertension. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2002; 3: 159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Connell C, Amar D, Boucly A, et al. Comparative safety and tolerability of prostacyclins in pulmonary hypertension. Drug Saf 2016; 39: 287–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tapson VF, Torres F, Kermeen F, et al. Oral treprostinil for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients on background endothelin receptor antagonist and/or phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor therapy (the FREEDOM-C study): a randomized controlled trial. Chest 2012; 142: 1383–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tapson VF, Jing ZC, Xu KF, et al. Oral treprostinil for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients receiving background endothelin receptor antagonist and phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor therapy (the FREEDOM-C2 study): a randomized controlled trial. Chest 2013; 144: 952–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Study to Compare Triple Therapy (Oral Treprostinil, Ambrisentan, and Tadalafil) with Dual Therapy (Ambrisentan, Tadalafil, and Placebo) in Subjects with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. NCT02999906. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02999906?term=oral+treprostinil&rank=10 Date last accessed: May 2017. Date last updated: June 2017.

- 31.Trial of the Early Combination of Oral Treprostinil with Background Oral Monotherapy in Subjects with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (FREEDOM-Ev). NCT01560624. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01560624?term=FREEDOM+Ev&rank=1 Date last accessed: May 2017. Date last updated: January 2017.

- 32.Sitbon O, Benza RL, Badesch DB, et al. Validation of two predictive models for survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2015; 46: 152–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benza RL, Miller DP, Gomberg-Maitland M, et al. Predicting survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension: insights from the Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Disease Management (REVEAL). Circulation 2010; 122: 164–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.The Efficacy and Safety of Initial Triple versus Initial Dual Oral Combination Therapy in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (TRITON) NCT02558231. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02558231 Date last accessed: August 2017. Date last updated: September 2016.

- 35.Farber HW, Miller DP, Meltzer LA, et al. Treatment of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension at the time of death or deterioration to functional class IV: insights from the REVEAL Registry. J Heart Lung Transplant 2013; 32: 1114–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McLaughlin VV, Langer A, Tan M, et al. Contemporary trends in the diagnosis and management of pulmonary arterial hypertension: an initiative to close the care gap. Chest 2013; 143: 324–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hay BR, Pugh ME, Robbins IM, et al. Parenteral prostanoid use at a tertiary referral center: a retrospective cohort study. Chest 2016; 149: 660–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sitbon O, Jaïs X, Savale L, et al. Upfront triple combination therapy in pulmonary arterial hypertension: a pilot study. Eur Respir J 2014; 43: 1691–1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Graarup J, Ferrari P, Howard LS. Patient engagement and self-management in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir Rev 2016; 25: 399–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guillevin L, Armstrong I, Aldrighetti R, et al. Understanding the impact of pulmonary arterial hypertension on patients’ and carers’ lives. Eur Respir Rev 2013; 22: 535–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morris NR, Kermeen FD, Holland AE. Exercise-based rehabilitation programmes for pulmonary hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 1: CD011285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mereles D, Ehlken N, Kreuscher S, et al. Exercise and respiratory training improve exercise capacity and quality of life in patients with severe chronic pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 2006; 114: 1482–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grünig E, Ehlken N, Ghofrani A, et al. Effect of exercise and respiratory training on clinical progression and survival in patients with severe chronic pulmonary hypertension. Respiration 2011; 81: 394–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grünig E, Lichtblau M, Ehlken N, et al. Safety and efficacy of exercise training in various forms of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2012; 40: 84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Man FS, Handoko ML, Groepenhoff H, et al. Effects of exercise training in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2009; 34: 669–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McLaughlin VV, Shah SJ, Souza R, et al. Management of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 65: 1976–1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruiter G, Lankhorst S, Boonstra A, et al. Iron deficiency is common in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2011; 37: 1386–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soon E, Treacy CM, Toshner MR, et al. Unexplained iron deficiency in idiopathic and heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension. Thorax 2011; 66: 326–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rhodes CJ, Howard LS, Busbridge M, et al. Iron deficiency and raised hepcidin in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension: clinical prevalence, outcomes, and mechanistic insights. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58: 300–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Howard LS, Watson GM, Wharton J, et al. Supplementation of iron in pulmonary hypertension: rationale and design of a phase II clinical trial in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm Circ 2013; 3: 100–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sadushi-Kolici R, Itariu B, Marculescu R, et al. Vitamin D and pre-capillary pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 189: A4777. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mirdamadi A, Moshkdar P. Benefits from the correction of vitamin D deficiency in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Caspian J Intern Med 2016; 7: 253–259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weill D, Benden C, Corris PA, et al. A consensus document for the selection of lung transplant candidates: 2014 – an update from the Pulmonary Transplantation Council of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2015; 34: 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Olsson KM, Delcroix M, Ghofrani HA, et al. Anticoagulation and survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension: results from the Comparative, Prospective Registry of Newly Initiated Therapies for Pulmonary Hypertension (COMPERA). Circulation 2014; 129: 57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Preston IR, Roberts KE, Miller DP, et al. Effect of warfarin treatment on survival of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) in the Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term PAH Disease Management (REVEAL). Circulation 2015; 132: 2403–2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Galiè N, Hoeper MM, Humbert M, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2009; 34: 1219–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maron BA, Opotowsky AR, Landzberg MJ, et al. Plasma aldosterone levels are elevated in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension in the absence of left ventricular heart failure: a pilot study. Eur J Heart Fail 2013; 15: 277–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Poms AD, Turner M, Farber HW, et al. Comorbid conditions and outcomes in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: a REVEAL registry analysis. Chest 2013; 144: 169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McGoon MD, Benza RL, Escribano-Subias P. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: epidemiology and registries. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62: D51–D59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rådegran G, Kjellström B, Ekmehag B, et al. Characteristics and survival of adult Swedish PAH and CTEPH patients 2000-2014. Scand Cardiovasc J 2016; 50: 243–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Frost AE, Janmohamed M, Fritz J, et al. Tolerability and safety of transition from inhaled treprostinil to oral selexipag in pulmonary arterial hypertension: results from the TRANSIT-1 study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 195: A2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chakinala MM, Feldman JP, Rischard F, et al. Transition from parenteral to oral treprostinil in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017; 36: 193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Coons JC, Miller T, Simon MA, et al. Oral treprostinil for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients transitioned from parenteral or inhaled prostacyclins: case series and treatment protocol. Pulm Circ 2016; 6: 132–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.D'Albini LD, Broderick M, Zaccardelli JG, et al. Real-world transitions from inhaled to oral treprostinil. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 195: A2298. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miller C. Transition from parenteral prostacyclin to selexipag in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 195: A2278. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Safdar Z. Single center experience in transitioning pulmonary arterial hypertension patients from intravenous epoprostenol to oral selexipag. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 195: A2288. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Edriss H, Schuller D, Nugent K, et al. Safe, successful, and effective transition from a sq prostacyclin analog (treprostinil) to oral prostacyclin receptor agonist (selexipag). Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 195: A2300. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hoeper MM, Ghofrani HA, Benza RL, et al. Rationale and design of the REPLACE trial: riociguat replacing phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor (PDE5i) therapy evaluated against continued PDE5i therapy in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 195: A2296. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hoeper MM, Simonneau G, Corris PA, et al. RESPITE: switching to riociguat in pulmonary arterial hypertension patients with inadequate response to phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors. Eur Respir J 2017; 50: 1602425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

S. Gaine ERR-0095-2017_Gaine (1.2MB, pdf)

V. McLaughlin ERR-0095-2017_McLaughlin (1.2MB, pdf)