Abstract

Background

People with pulmonary fibrosis often experience a protracted time to diagnosis, high symptom burden and limited disease information. This review aimed to identify the supportive care needs reported by people with pulmonary fibrosis and their caregivers.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines. Studies that investigated the supportive care needs of people with pulmonary fibrosis or their caregivers were included. Supportive care needs were extracted and mapped to eight pre-specified domains using a framework synthesis method.

Results

A total of 35 studies were included. The most frequently reported needs were in the domain of information/education, including information on supplemental oxygen, disease progression and prognosis, pharmacological treatments and end-of-life planning. Psychosocial/emotional needs were also frequently reported, including management of anxiety, anger, sadness and fear. An additional domain of “access to care” was identified that had not been specified a priori; this included access to peer support, psychological support, specialist centres and support for families of people with pulmonary fibrosis.

Conclusion

People with pulmonary fibrosis report many unmet needs for supportive care, particularly related to insufficient information and lack of psychosocial support. These data can inform the development of comprehensive care models for people with pulmonary fibrosis and their loved ones.

Short abstract

Summary of unmet care needs reported by people with pulmonary fibrosis and their caregivers across a range of settings and countries. People with pulmonary fibrosis and their caregivers have many unmet needs. The results can help improve care provided for people with pulmonary fibrosis and caregivers. http://bit.ly/39PdjfQ

Introduction

People living with pulmonary fibrosis often experience a protracted route to diagnosis, high symptom burden, limited disease information and anxiety about the future [1]. While antifibrotic treatments have brought a sense of hope that disease progression can be slowed, these treatments may not relieve symptoms or improve quality of life, and some patients do not meet the criteria for funded treatment. In a recent study, half of the patients with pulmonary fibrosis reported four or more unmanaged symptoms such as breathlessness, depression, cough, sleep difficulty, anxiety and fatigue and perceived few options for symptom control [2, 3]. Breathlessness and cough are most prevalent, occurring in 54–98% and 59–100% of people with pulmonary fibrosis, respectively [4]. Anxiety is present in up to one-third of individuals living with pulmonary fibrosis, while symptoms of depression occur in 25% [5].

Supportive care needs can be defined as informational, emotional, spiritual, social or physical needs experienced at any stage of the healthcare journey [6]. A number of studies have investigated the supportive care needs of people with pulmonary fibrosis in settings across the world [16, 20, 25, 29]. Studies conducted prior to the antifibrotic era (pre-2011) tended to focus on the experience of diagnosis [1, 17] with limited data on the support needs at other stages of the pulmonary fibrosis journey. Since then, there have been emerging data documenting the experience of modern pulmonary fibrosis care in settings across the world, providing more information about experiences with new treatments [7, 8]. All these studies provide valuable insights that could enhance patient-centred care and improve outcomes. One previous systematic review synthesised the literature on symptom prevalence in people with pulmonary fibrosis [4]; however, only quantitative studies were included and other supportive care needs were not addressed. The aim of this review was to identify the supportive care needs reported by people living with pulmonary fibrosis and their caregivers.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted of studies reporting the supportive care needs of people with pulmonary fibrosis and their caregivers. The review was registered at PROSPERO (CRD42019131878). Four electronic databases (EMBASE, CINAHL, MEDLINE and PsychINFO) were searched from their inception to 10 July 2019 (table S1). The search was limited to publications in English and studies that included adults aged ≥18 years. There was no restriction on year of publication, type of literature, study methodology or research design. Studies were included if they investigated the supportive care needs of people with pulmonary fibrosis or their caregivers. Studies reporting the supportive care needs of people with other types of lung disease were excluded, unless results were presented separately for people with pulmonary fibrosis. We also excluded studies that tested the psychometric properties of tools designed to measure supportive care needs. Reporting was performed according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [9].

Two independent researchers (A. Watson and J. Lee) screened the titles and abstracts of retrieved studies for eligibility. Those that met the inclusion criteria, or where it was unclear whether the study met the inclusion criteria, were retrieved in full. Additional searches were conducted on Scopus and Google Scholar to identify published articles that were linked to any retrieved conference abstracts. All full texts were reviewed by two independent researchers (A.E. Holland and J. Lee) to determine study inclusion, with any disagreements resolved by consensus. The reference lists of all included studies were searched for additional studies that met the inclusion criteria.

Two researchers (J. Lee and G. Tikellis) independently assessed the methodological quality of included studies using the QualSyst tool, which is used to evaluate the quality of both qualitative and quantitative studies [10]. In this tool, the qualitative scale has 10 items with a total possible sum of 20. Each item is scored according to the extent to which the criteria was met (yes: 2, partial: 1, no: 0).A summary score was recorded for each study. Summary scores for quantitative studies were similarly calculated based on 14 items with a maximum possible sum of 28. Five items could be marked as “not applicable” and excluded from the calculation of the summary score, where applicable. Where studies used mixed methods, assessment was performed according to the more dominant method. Any scoring discrepancies between the researchers were resolved by discussion until consensus was reached. No studies were excluded based on methodological quality.

Data extraction was performed by one reviewer (J. Lee), with random checks for accuracy carried out by a second reviewer (A. Hey-Cunningham), using a data extraction form specifically developed for this study and piloted on two randomly selected studies. Data extracted included study design, characteristics of the sample, methods of data collection and analysis, and the supportive care needs identified. Supportive care needs were classified into eight conceptual domains as previously defined [11]: 1) Physical/cognitive: symptom management and treatment-related toxicity, and cognitive dysfunction; 2) Psychosocial/emotional: psychological/emotional symptoms such as depressive mood, anxiety, fear/worry and despair; 3) Family related: dysfunctional family relationships and fears/concerns for family's future; 4) Social/societal: experience of social isolation, inefficient social support and diminished socialisation; 5) Interpersonal/intimacy: altered body image or sexuality, sexual health problems and compromised intimacy with partner; 6) Practical/daily living: transportation, advanced directives, out-of-hours accessibility, funeral care, financial strain, experience of restriction in daily living tasks such as housekeeping, and exercise; 7) Information/education: lack of information, uncertainty about diagnosis/treatment and uncertainty/lack of knowledge about self-care; 8) Health system/patient–clinician communication: insufficient communication between patients and clinicians, satisfaction with care, participation in decision-making and preferences in communication.

Individual supportive care needs were extracted and mapped to the relevant domain using a framework synthesis method, with supportive quotes extracted verbatim from each paper. Thematic analysis was conducted to identify any new domains for data outside the pre-specified domains. The prevalence of each supportive care need was reported where such information was available from quantitative studies. The frequency of studies identifying the different domains was reported. As the majority of studies were qualitative in nature, a narrative synthesis was performed and representative quotes presented. Where there were sufficient data, subgroup analyses were performed for: 1) idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) versus other types of pulmonary fibrosis; 2) antifibrotic era versus pre-antifibrotic era; and 3) disease stage, i.e. time of diagnosis versus routine follow-up versus end of life.

Results

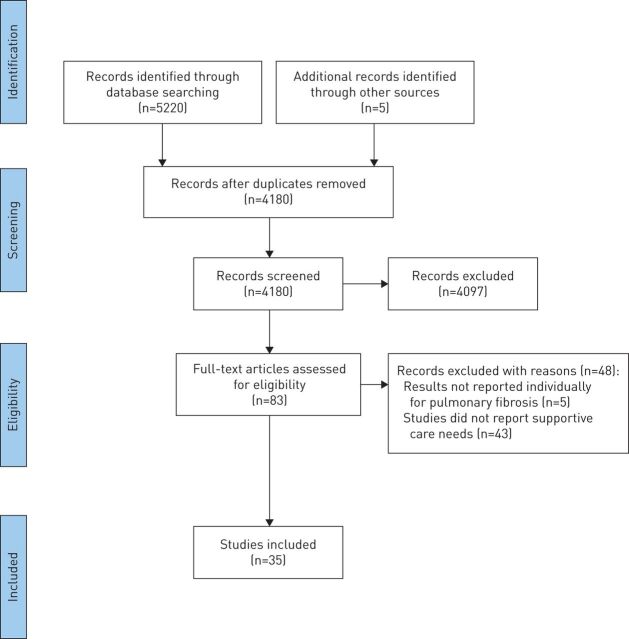

A total of 4180 records were identified after excluding duplicates, with 83 studies retrieved for full-text review (figure 1). A total of 35 studies were included, consisting of 28 full-text articles [1, 3, 7, 8, 12–35] and seven conference abstracts [36–42]. These had been published between 2005 and 2019 and were predominantly conducted in the USA (n=13), UK (n=10) and other parts of Europe (n=8). Overall, 2621 (69%) patients, 590 (16%) informal caregivers and 558 (15%) healthcare professionals/clinical researchers/policy experts were included. One study did not report number of participants (i.e. patients and staff) [37], while another study reported the responses (n=471) received via blog entries or discussion forum threads on three interactive pulmonary fibrosis-focused websites, rather than the number of participants [12]. The characteristics of included studies are presented in table S2.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Studies most commonly included participants with IPF and their caregivers (n=3076, 96%); in 12 studies a small number of people with other pulmonary fibrosis diagnoses were also included (e.g. nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis and connective tissue disease). 11 studies reported pulmonary function, with forced vital capacity 31–125% pred (n=7) and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide 13–95% pred (n=7). About half of the studies recruited participants from specialist clinics (n=19), other settings included patient support groups (n=4), patient advocacy organisations (n=3), tertiary hospitals (n=2), a non-profit organisation (n=1), an IPF registry (n=1) and a lung transplant centre (n=1). 17 (47%) studies were conducted in the antifibrotic era [7, 8, 14, 16, 20–24, 30–35, 41, 42]. Most studies reported experiences of diagnosis and treatment, with six focused specifically on end-of-life or palliative care [3, 20, 25, 32, 37, 40].

15 studies used semi-structured and in-depth interviews (43%), 11 administered questionnaires [7, 14, 17, 24, 33, 37–42], five used focus groups [13, 20, 21, 23, 27], three used a combination of methods [26, 31, 35], and one used narrative data from websites [12]. 23 (65%) studies used a qualitative data analysis method. Quantitative methods were used to report findings regarding disease management [7, 38, 39], patient education and support [17, 24], patient expectations of care [41], quality of life [26, 38, 41] and anxiety [24]. Six studies were conducted using mixed methods [26, 31, 33, 35, 37, 42]. Meta-analysis was not possible as the number of quantitative studies was small and the data heterogeneous.

Quality assessment scores generally ranged from 70–95% (tables S3 and S4). However, four studies, all reported as abstracts only, scored ≤55%. Strengths of the qualitative studies were clearly described research questions or objectives, appropriate and easily identified research designs, and study conclusions that were supported by data. Most qualitative studies scored poorly on reporting evidence of reflexivity, the connection to a theoretical framework and sampling strategy (frequently a convenience sample). Quantitative studies scored well on items related to clearly specifying objectives and conclusions supported by study results, but reporting of participant characteristics was frequently poor.

Supportive care needs

The supportive care needs of people with pulmonary fibrosis are summarised in tables 1–4. The most frequently reported needs were in the domain of information/education (26 studies) and psychosocial/emotional care (22 studies), although all domains were represented. An additional domain of “access to care” was identified, which was reported in 27 studies.

TABLE 1.

Summary of supportive care needs: physical/cognitive and psychosocial/emotional domains

| Needs domain and category | Studies n | Individual reporting need | Representative quotes | |

| Patient | Caregiver | |||

| Physical/cognitive # | “Coughing! Coughing! People would ask why didn't you go to a different bedroom so you didn't have to hear the cough, but I would feel bad, I couldn't tell him. I was going to work on 2–3 h of sleep” (caregiver of a deceased patient) [20] “When it's really really bad, I'd make a trade with the devil … because I'm so … flat and exhausted and [I] think well I'd rather not go on” (patient with advanced IPF) [3] “The side-effects were making me feel more sick than my life. I couldn't go out, I couldn't catch a tram, for instance, because you never knew when you were going to explode. I felt sick, lost weight and felt nauseous and I still persevered” (patient with IPF using antifibrotic therapy) [16] |

|||

| Cough | 13 | |||

| Dyspnoea | 9 | |||

| Fatigue | 9 | |||

| Management of treatment side-effects | 5 | |||

| Physical limitation | 5 | |||

| Poor sleep | 3 | |||

| Phlegm | 2 | |||

| Incontinence | 1 | |||

| Psychosocial/emotional ¶ | “You know, it's just … really frustrating to tell you the truth, these things are happening to my body … that I can't do anything about it [higher pitched voice]” (patient with IPF) [25] “What am I going to do with the rest of my life without my husband? It's pretty scary. We've been married for 58 years” (caregiver of patient with IPF) [13] “You're not free, can't laugh or cry fully because if you do you won't be able to breathe even with oxygen – that is terrible and upsetting. Also being tied to oxygen makes you feel like stuck you're inside the cage” (patient with IPF) [1] “I'm confused, because I become this caregiver that isn't giving any care, but more of a nag” (caregiver of patient with IPF) [23] “I think the most shocking thing is how quickly, even though maybe people have been told you've got 3 months, 6 months, whatever months. I think when that day actually comes it's probably always a shock. The Tuesday we saw her with a team of doctors and Sunday she was gone” (bereaved caregiver) [32] “Sometimes I feel ashamed about the things I can't do” (patient with IPF) [34] “I do get frustrated when it physically affects me, not being able to do things that I planned to do” (patient with IPF) [34] |

|||

| Anger, frustration | 11 | |||

| Anxiety | 9 | |||

| Sadness, grief | 9 | |||

| Fear of future | 8 | |||

| Depression | 8 | |||

| Shock | 7 | |||

| Loss of identity/sense of self | 6 | |||

| Fear of being a burden on others | 5 | |||

| Loss of control, powerlessness | 4 | |||

| Feeling overwhelmed, helpless | 5 | |||

| Denial | 4 | |||

| Guilt | 4 | |||

| Panic | 3 | |||

| Loneliness | 3 | |||

| Confusion, resentment | 3 | |||

| Difficulty maintaining hope and optimism | 2 | |||

| Feeling of shame, embarrassment | 2 | |||

| Fixating on the disease | 2 | |||

| Feeling vulnerable | 2 | |||

| Feeling insecure | 1 | |||

| Self-pity | 1 | |||

| Regret | 1 | |||

| Burn out | 1 | |||

Shading indicates where supportive care need was identified by the patient and/or caregiver. IPF: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. #: n=16; ¶: n=22.

TABLE 4.

Summary of supportive care needs; health system/communication and access to care domains

| Needs domain and category | Studies n | Individual reporting need | Representative quotes | |

| Patient | Caregiver | |||

| Health system/patient–clinician communication# | “I was angry and upset; it took over 2 years to get a diagnosis and I felt none of the doctors cared” (patient with IPF) [1] “I came in and saw the nurse and she knew more and understood more about my complaint than anyone I'd seen prior…. It gives you confidence” (patient with IPF) [28] “I think they try to liaise between each other but it so often falls apart … there is really a short coming amongst getting information from one aspect of the medical profession to the other” (caregiver of patient with advanced IPF) [25] “Their honesty in their conversation was huge as well. Being able to look my mom in the eye and tell her that she's dying and that she will be dead within the year. And then, taking the time to sit there and hold her hand and wait until she was ready to talk, and answer her questions, and let her know what that death was going to look like [pause] I think is also really big” (bereaved caregiver) [32] |

|||

| Benefits of specialist centres | 7 | |||

| More timely and accurate diagnosis | 7 | |||

| Honesty about what the future holds | 6 | |||

| Benefits of specialist pulmonary fibrosis nurses | 5 | |||

| Healthcare professionals to be better informed | 5 | |||

| Sensitivity in delivering diagnosis and prognosis –allowing enough time | 4 | |||

| Ongoing relationship with healthcare professionals | 3 | |||

| Coordination of care between healthcare professionals/shared care with local healthcare professionals | 2/1 | |||

| Encourage self-management | 2 | |||

| Timing of end-of-life conversations | 2 | |||

| Role for caregivers in consultation | 1 | |||

| Access to information at “touchpoints” between consultations | 1 | |||

| Understanding goals of therapy | 1 | |||

| Feedback from clinical trials | 1 | |||

| Adherence to palliative care guidance by healthcare professionals | 1 | |||

| Access to care ¶ | “… somebody that I could ask questions of; somebody who has been down that path, that, um, you know, that they would, would be available to, and willing, to talk about how do you do this or how do you do that” (patient with IPF using oxygen for 9–12 months) [26] “The doctors helped me, but I have never received any psychological support, I really need it” (patient with IPF using pirfenidone) [8] “Being able to speak to someone over the phone about my problems has been very reassuring, rather than having to wait until my next clinic visit” (patient with IPF using pirfenidone) [7] “I can't get a lung transplant because I'm too old. I've just accepted it” (patient with IPF using antifibrotic therapy) [16] “They also said there were treatments that were not available in Spain yet. I even asked her [the doctor] if we could get it, and she told us it was impossible… Those 2 years we were missing [out on treatment]… We could do nothing about it, there were parameters [to qualify for treatment]” (patient with IPF) [31] |

|||

| Support groups/peer support | 12 | |||

| Emotional/psychological support | 8 | |||

| Specialist centres | 8 | |||

| Support/care for family | 6 | |||

| Pharmacological treatment | 6 | |||

| More effective treatments | 5 | |||

| Specialist nurse | 5 | |||

| Lung transplantation | 4 | |||

| Palliative care, including death at home | 4 | |||

| Pulmonary rehabilitation/maintenance pulmonary rehabilitation programmes in community (led by pulmonary fibrosis specialist) | 3/1 | |||

| Multidisciplinary teams | 4 | |||

| Pulmonology specialists | 4 | |||

| Home modification/adaptation | 3 | |||

| Supplemental oxygen | 3 | |||

| End-of-life counselling | 3 | |||

| Specialist visits | 2 | |||

| Diagnostic tests | 2 | |||

| Advocacy group | 1 | |||

| Clinical trial | 1 | |||

Shading indicates where supportive care need was identified by the patient and/or caregiver. IPF: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. #: n=22; ¶: n=27.

Physical/cognitive needs

The most common and distressing symptoms were cough, dyspnoea and fatigue, which were reported in 16 studies (table 1). Paroxysms of cough were exhausting for patients and impacted on sleep quality for both patients and caregivers [3, 20, 22]. Patients reported having to take breaks during simple tasks such as showering or bending in order to catch their breath [27]. Cough-related incontinence was also reported [28], which caused significant distress in 15% of patients (95% CI 7–23%) [39]. Patients often experienced side-effects of antifibrotic treatment including weight loss, nausea, diarrhoea and photosensitivity, and desired help to better manage these [8, 16]. 22% of patients with pulmonary fibrosis felt their symptoms were not controlled (95% CI 13–30%) [39].

Psychosocial/emotional needs

The psychosocial/emotional needs of patients and caregivers were reported in 22 studies (table 1). At the time of diagnosis patients and caregivers often experienced anger, frustration and loss of control [13, 23, 25]. Two-thirds of patients and caregivers experienced anxiety [24]. They were fearful about disease progression and struggled with uncertainty about the future, including loss of employment or income [8, 21, 30]. Patients worried about losing independence and becoming a burden on their family and society [1, 20, 27], while caregivers feared losing their loved ones [13]. Many patients felt guilty for not being able to fulfil their usual roles [28]. Sadness and depression were frequently reported [1, 8, 13, 19, 21, 22, 27]. In a European survey, 80% of patients wanted the possibility of psychological support and 23% thought it was lacking in current care [24].

As the disease progressed, both patients and caregivers felt overwhelmed and helpless [3, 13]. Some patients experienced panic due to shortness of breath [3]. Being prescribed supplemental oxygen was often viewed as “losing the battle” [19] and was associated with a loss of hope [8]. Patients felt vulnerable using oxygen, and ashamed or embarrassed because it made their illness visible to others [8, 15]. Many patients and caregivers felt lonely and isolated as the disease took over their lives [3, 22]. Some caregivers found it difficult to adapt to their new roles, some felt resentful, some were conflicted between their duty and living their own lives, and some burnt out [13]. More than 60% of the partners of people with pulmonary fibrosis wished for more care, specifically for caregivers [24].

Family-related needs

The family-related needs of patients and caregivers were reported in 14 studies (table 2). Losing independence and becoming a burden on the family were prominent concerns for patients [15], with 27% reporting that they worried about the effect of their illness on their loved ones [39]. Family caregivers assisted with personal hygiene and supplemental oxygen use; many described how increased reliance on their spouse had caused relationship strain. Family members often found it difficult to maintain relationships with others outside the family as caregiver responsibilities consumed most of their time [3]. Many patients noted a loss of privacy because they needed assistance from the family with so many tasks [27]. Some patients feared passing on the disease to their families [15]. Patients and families were often living at a different pace; some felt frustrated that their loved ones “can't keep up”, while many experienced difficulties in travelling together [19].

TABLE 2.

Summary of supportive care needs: family-related, social/societal and interpersonal/intimacy domains

| Needs domain and category | Studies n | Individual reporting need | Representative quotes | |

| Patient | Caregiver | |||

| Family-related# | “What has suffered is my relationships more with my family and my friends, because I'm just busy [being a caregiver to my husband with IPF] all the time” (caregiver of patient with IPF) [13] “My family checks everything I do, I don't feel free” (patient with IPF using pirfenidone) [8] “Eventually she is talking about us moving downstairs and staying downstairs once it gets to a certain point – well, I don't want that. I'd rather take 10 min to go upstairs to go to bed than staying downstairs all the time” (patient with IPF) [34] |

|||

| Increased physical/practical burden on caregiver | 9 | |||

| Change in caregiver lifestyle/role | 7 | |||

| Loss of role within family | 5 | |||

| Increased reliance on family | 4 | |||

| Living at a different pace to family | 2 | |||

| Loss of privacy due to need of assistance | 2 | |||

| Different expectations between patient and family | 2 | |||

| Unable to travel with family | 1 | |||

| Fear of passing a genetic disease on to family | 1 | |||

| Family takes over decisions about lifestyle | 1 | |||

| Social/societal ¶ | “I am trading from one stigma for another, because, you know, I've heard people say, “Well he's on oxygen because he was a smoker” (patient with IPF) [26] “I can't go anywhere … I don't [really] have a life, I'm sitting indoors every day” (patient with advanced IPF) [3] “When people see you coughing they say “Take cough medicine, take this, take that”, they don't understand it … and they would say, “Why you are panting when you are doing nothing literally?” (patient with IPF) [34] |

|||

| Stigma/lack of community understanding | 12 | |||

| Social isolation | 5 | |||

| Go out less/fewer social opportunities | 4 | |||

| Difficulty maintaining relationships | 2 | |||

| Interpersonal/intimacy+ | “[W]e're not intimate at the moment [higher pitched voice] … we don't even talk about it, we just sort of blank it out because I just don't have the will or the energy to do [slight laugh] anything …. Having intercourse, you know and you know, making love with each other and that sort of thing, yeah … I just don't have the energy but … we just don't talk about it” (patient with IPF) [3] | |||

| Loss of sexual intimacy | 4 | |||

| Altered body image/sexuality | 3 | |||

Shading indicate where supportive care need was identified by the patient and/or caregiver. IPF: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. #: n=14; ¶: n=17; +: n=4.

Social/societal needs

The social/societal needs of patients and caregivers were reported in 17 studies (table 2). Patients frequently reported social stigma and a lack of community understanding of pulmonary fibrosis [15, 19, 26], with over one-third of patients and partners regularly feeling misunderstood because people did not know what pulmonary fibrosis was [24]. This made it difficult to interact with others, including friends, family, employers and insurers [18, 21, 24]. Patients believed that an increased disease awareness among healthcare professionals was needed to improve accurate and timely diagnosis [1]. Both patients and caregivers experience social isolation [1, 3, 22]. Patients reduced their attendance at social events as the disease progressed, while caregivers often gave up their own social life [3, 13]. Many patients were reluctant to attend social occasions that involve crowds of people to avoid “catching something” [27].

Interpersonal/intimacy needs

Th interpersonal/intimacy needs of patients and caregivers were reported in four studies (table 2). Both patients and spouses expressed decreased libido and reduced physical stamina during sexual intercourse [3, 27]. Partners were concerned about their loved one over-exerting themselves during sexual activity [27]. 15% of male patients suffered physically and emotionally in their sex lives [8]. Many felt less attractive or sexually desirable, especially those who used supplemental oxygen [27].

Practical/daily living needs

The practical/daily living needs of patients and caregivers were reported in 18 studies (table 3). The ability of patients to perform activities of daily living diminished over time, including tasks such as shaving, showering and shopping [18, 27, 28]. Many had given up hobbies and activities that they once enjoyed [3, 13, 18, 26, 30]. Distress related to loss of independence and inability to complete simple daily tasks was reported by 18% of patients (95% CI 10–26%) [39]. Practical limitations were particularly obvious among patients who used supplemental oxygen. Caregivers viewed patients as being “tied” to their oxygen [19]. The challenge of transporting the oxygen tank required careful planning of excursions [16, 19]. Caregivers assumed physical duties related to oxygen use, such as filling tanks and cleaning the equipment [13, 19]. Both patients and caregivers wanted practical assistance with end-of-life planning [38]. Although discussion of this topic was less acceptable in some countries, patients generally wanted to know more about the dying process and whether their symptoms would be controlled towards the end of life; many expressed that they would like to be prepared and have their “affairs in order” [27].

TABLE 3.

Summary of supportive care needs: practical/daily living and information/education domains

| Needs domain and category | Studies n | Individual reporting need | Representative quotes | |

| Patient | Caregiver | |||

| Practical/daily living# | “He can't bend over. If he bends over, forget it. So I empty out the bottom of the dishwasher. He empties the top, because he likes to participate” (caregiver of patient with IPF) [13] “Even showering becomes a problem; you do it in stages. And someone has to be here” (patient with IPF) [18] “… just the inconvenience of it all (oxygen therapy) and the stupid line all over the house, and I trip on, because it's always – my leash, as my husband calls it” (patient with IPF using oxygen for 9–12 months) [26] “If there was a plan, if we knew what was going on, then we could make decisions…. There are no standard procedures for end-of-life decision makers” (advocate) [15] |

|||

| Loss of independence/decreased ability to perform activities of daily living | 9 | |||

| Financial burden/loss of income | 7 | |||

| End-of-life planning (insufficient information/do not have a plan) | 7 | |||

| Requiring more time, planning and adaptation both inside and outside of home | 7 | |||

| Physical challenges of transporting oxygen | 6 | |||

| Given up hobbies | 6 | |||

| Concerns with oxygen limitation outside of home | 3 | |||

| Physical challenges of using oxygen at home | 3 | |||

| Information/education ¶ | ||||

| Disease progression and prognosis | 14 | “I am dissatisfied; the disease was not explained to me. I feel like people assumed I know, but in general it felt like you were left, like, in the corner” (non-IPF patient) [21] “I remember searching on the Internet, and thinking, ‘I'll probably be dead next week.’ In the beginning, because you know so very little, it can be very frightening. It was so confusing” (patient with IPF) [31] “They say you are like this and that's how you are going to end up like. And you think, what's going to happen in between?’ (patient with IPF) [34] “[W]hen I went to see him a month or two back, he said, ‘Are you using your oxygen?’ I said, ‘No’. I said, ‘It's too bloody hard to connect’…. He said, ‘It's the easiest thing you can do. Why haven't you tried it?’ I said, ‘No one has told me how easy it is”’ (patient with IPF who had ceased antifibrotic therapy) [16] “[I]t would be wonderful to have, once-a-month, a highlight on somebody who says “Yeah, I've been dealing with this for 11 years, this is what my life is like” instead of reading some statistic” (patient with IPF) [23] “It is difficult for us to help them, we would like to have more information about what we should do at home” (caregiver of patient with IPF using pirfenidone) [8] |

||

| Supplemental oxygen, including travel with oxygen | 13 | |||

| Pharmacological treatments | 11 | |||

| Planning for end-of-life | 11 | |||

| Coping strategies | 9 | |||

| Managing symptoms (breathlessness and cough) | 8 | |||

| Non-pharmacological treatments/ alternative therapies | 7/1 | |||

| Research and clinical trials | 7 | |||

| Pathophysiology | 6 | |||

| How to provide practical/emotional care for loved one with pulmonary fibrosis | 4/2 | |||

| Lung transplantation | 5 | |||

| Understanding tests used for diagnosis and monitoring | 4 | |||

| Treatment centres/referral to suitable specialists | 3 | |||

| Travelling with pulmonary fibrosis | 2 | |||

| How to recognise and deal with important signs and symptoms | 3 | |||

| Signs and symptoms of pulmonary fibrosis | 2 | |||

| Causes of pulmonary fibrosis | 2 | |||

| Managing comorbidities | 1 | |||

| Success stories of living with pulmonary fibrosis | 1 | |||

| Homecare/drug delivery | 1 | |||

| Advocacy | 1 | |||

| How to avoid infection | 1 | |||

| How to communicate with a frustrated/ angry/depressed patient | 1 | |||

| How doctors follow IPF over time | 1 | |||

| How to access community supports | 1 | |||

Shading indicate where supportive care need was identified by the patient and/or caregiver. IPF: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. #: n=18; ¶: n=26.

Information/education needs

The information/education needs of patients and caregivers were reported in 26 studies (table 3). Over half of the patients and caregivers reported that there was a lack of information and resources about pulmonary fibrosis at the time of diagnosis [17]. The majority of patients (77%) had not heard of pulmonary fibrosis when they were diagnosed and only 57% remembered being told that IPF is progressive at the time of diagnosis, while 43% remembered being informed about treatment options [31]. The most common topics for which practical information was desired were disease progression and prognosis, how to manage medications and their side-effects use of supplemental oxygen, end-of-life planning and the dying process, and practical coping strategies for living with pulmonary fibrosis [1, 3, 7, 8, 12, 15–17, 19–21, 23, 26–30, 40]. Both patients and caregivers also desired more information on: how to manage breathlessness and cough [7, 12, 21, 29, 30, 37, 40]; the basic mechanisms and pathophysiology of pulmonary fibrosis [3, 8, 12, 21, 24, 40]; nonpharmacological therapies such as exercise and diet [7, 8, 12, 17, 30]; current research and feedback from clinical trials [8, 12, 16, 23, 28]; interpretation of clinical tests used for diagnosis and monitoring [7, 12, 21, 30]; and how to access treatment centres and referrals [12, 24]. Both patients and caregivers wanted to learn how to recognise and deal with important signs and symptoms [16, 23], while caregivers wanted more information on emotional and practical care of their loved ones, including how to avoid infections [8, 23, 30].

Health system/patient–clinician communication

The health system/patient–clinician needs of patients and caregivers were reported in 22 studies (table 4). Patients and caregivers identified a lack of awareness of pulmonary fibrosis among health professionals, leading to delays in obtaining a diagnosis [1, 14, 21]. It was important that the diagnosis and prognosis were delivered in a “sensitive and unhurried manner”, allowing the patients to express concerns and digest the information [1, 18, 23]. Most believed early referral to a specialist centre was beneficial for timely diagnosis, access to clinical trials, access to medications and obtaining trustworthy information [14, 16, 18, 20, 24, 28, 30]. However, in a European study, one-third of patients preferred that their care was shared between the expert centre and their local pulmonologist [24]. They preferred health professionals to be honest about the prognosis and give information on what to expect over the course of the disease; however, some perceived that this information was withheld [20, 21, 29, 30]. Some patients expressed concerns about the timing of end-of-life planning discussions and felt that care should be taken by health professionals when initiating these difficult conversations [3]. Patients found the specialist pulmonary fibrosis nurse to be an important source of information and support [24]. The opportunity to access information at “touchpoints” between consultations was highly valued, as was independent advice for caregivers [30]. Patients wanted their health professionals to provide more opportunities for self-management, as it gave hope and a sense of control [16]. They wanted different health professionals to work together to lessen the burden of medication side-effects and reduce the chance of scheduling appointments at conflicting times.

Access to care

The access to care of patients and caregivers were reported in 27 studies (table 4). Both patients and caregivers wanted better access to peer support [12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22, 26, 29, 30, 40]. They wanted access to counselling or psychological support services from the point of receiving a diagnosis to the end of the pulmonary fibrosis journey [1, 8, 14, 15, 18, 21, 22]. Patients expressed concerns for the support needs of their families [8, 14, 24, 37]. Many patients also identified a need for patient-based advocacy groups for ongoing education and support [1]; however, such services were often perceived as lacking [14, 21, 24]. Although patients noted that pulmonary rehabilitation provided valuable emotional support [14], it was not always available, accessible or affordable [14, 16]. Patients perceived that there were insufficient specialist centres, respiratory specialists and specialist nurses, especially in regional areas [16, 20, 24]. The vast majority of patients in a European study thought seeing a pulmonary fibrosis specialist nurse was beneficial (88%) and 21% would like to see the pulmonary fibrosis nurse every time they visited their doctor, but in some countries such nurses were not available [24]. Due to the unpredictability and complexity of pulmonary fibrosis, patients believed specialist visits should be more frequent, and that early multidisciplinary support should be incorporated [1, 14, 30]. Patients sometimes struggled to afford antifibrotic drugs, supplemental oxygen, diagnostic tests, respiratory seminars and home modifications [14, 16, 20]. Patients perceived that lung transplantation was frequently inaccessible due to criteria for candidate selection and/or lack of available organs [14].

Planned subgroup analyses

IPF versus other types of pulmonary fibrosis

The vast majority (96%) of participants were patients with IPF or their caregivers, so there was insufficient data to determine whether supportive care needs were different for other pulmonary fibrosis diagnoses.

Antifibrotic era versus pre-antifibrotic era

In 17 studies it was possible to confirm that the data had been collected in the antifibrotic era [7, 8, 14, 16, 20–24, 30–35, 41, 42]. These studies identified supportive care needs across all nine domains. In the physical/cognitive domain these studies were more heavily represented than studies from the pre-antifibrotic era in the theme of managing treatment side-effects (gastrointestinal, photosensitivity and weight loss). In the health system domain, these studies were more heavily represented in themes related to the benefits of specialist pulmonary fibrosis centres and specialist pulmonary fibrosis nurses. In the access to care domain, these studies were the sole contributors to the theme of difficulty accessing pharmacological treatment, either because the antifibrotic therapy was not approved or too expensive.

Disease stage

No studies reported patient needs at the time of diagnosis separately to those during treatment and follow-up. Six studies specifically addressed end-of-life care [3, 20, 25, 32, 37, 40], reporting supportive care needs in all nine domains, with no evidence that themes differed from the other studies. The need for information on end-of-life planning was also identified by patients and caregivers in six additional studies that addressed more general aspects of treatment (information domain) [15, 21, 27, 29, 30, 33], suggesting this need is not restricted to those nearing the end-of-life.

Discussion

This systematic review shows that people with pulmonary fibrosis have important supportive care needs across a wide range of domains. The most frequently reported needs were in the domains of information/education, particularly at the time of diagnosis, as well as psychosocial/emotional support. Psychosocial needs were evident across both patients and their caregivers, including help with managing anxiety, fear, anger, sadness and grief. Practical needs for support with activities of daily living were also expressed by both patients and caregivers, including loss of independence, financial burden and challenges managing oxygen equipment. Importantly, the review identified an additional domain of “access to care”, including access to peer support, psychological support, specialist centres and family support; these challenges were reported across many different countries and health systems.

The supportive care needs of people with pulmonary fibrosis do not appear to have changed substantially in the antifibrotic era, aside from a greater need to manage drug side-effects and increased awareness of the benefits of specialist pulmonary fibrosis services. Therefore, it seems likely that advances in supportive care have not kept pace with advances in other aspects of treatment. For instance, while anxiety and depression have been thoroughly documented in people with pulmonary fibrosis in recent years, specific treatment strategies for this group are lacking [43]. The enormous psychosocial and emotional burden of pulmonary fibrosis documented in this review suggests that this should be a priority for clinical practice and future research. The desire for peer support was particularly evident, with many patients and caregivers expressing their desire for support groups and increased psychosocial care. Patient advocacy organisations frequently have a critical role in providing supportive care services, with pharmaceutical companies also active in this area [7]. However study participants had a clear expectation that such services would also be linked with their healthcare team (table 4) and emphasised the important role of specialist pulmonary fibrosis centres. These data suggest that supportive care needs could be addressed by multidisciplinary pulmonary fibrosis healthcare teams that are well integrated with other health, community and social care services.

While some of the supportive care needs related directly to health and wellbeing, others related to the broader social context. Stigma and lack of community understanding of pulmonary fibrosis were frequently reported (table 2), which added to patient distress. Health-related stigma has been defined as an adverse social judgement based on an enduring feature of identity conferred by a health problem [44]. Stigma is commonly reported across a range of chronic lung diseases and has adverse impacts on quality of life, psychosocial and physical wellbeing, and experience of treatment [45]. Stigma may therefore impact on other domains identified in this review, including social isolation and access to care. The connection between stigma and other domains of patient experience suggests that the need for information and education about pulmonary fibrosis may extend beyond the patient and caregiver (table 3) to health professionals and to the wider community.

A strength of this review is the synthesis of studies conducted across a wide range of settings to provide a comprehensive overview of supportive care needs in pulmonary fibrosis. These data can be used by pulmonary fibrosis service providers to inform the design of care models that directly address the needs of patients and caregivers. Limitations to the review include a lack of included studies addressing the supportive care needs of people with non-IPF diagnoses, which may differ due to the diversity of disease course and prognosis. Most studies used qualitative methodology, which did not allow us to document the prevalence of each supportive care need; however, such methodology provides rich data regarding patient and caregiver experiences.

In conclusion, people with pulmonary fibrosis and their caregivers have a wide range of supportive care needs, particularly for increased information about their disease and its treatment, and better psychosocial and emotional support. This provides opportunities to optimise delivery of comprehensive pulmonary fibrosis care to meet the needs of people living with pulmonary fibrosis and those who care for them.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

ERR-0125-2019_Supplementary_tables ERR-0125-2019_Supplementary_tables (331KB, pdf)

Footnotes

This article has supplementary material available from err.ersjournals.com

This study is registered at PROSPERO with registration number CRD42019131878.

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed

Conflict of interest: J.Y.T. Lee has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: G. Tikellis has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: T.J. Corte reports grants and personal fees from Roche and Boehringer, and grants from Galapagos, Actelion and Sanofi, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: N.S. Goh has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: G.I. Keir has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: L. Spencer has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: D. Sandford has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: Y.H. Khor reports non-financial support from Air Liquide Healthcare, grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, and personal fees from Roche, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: I. Glaspole reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, Menarini, Pulmotect and Avalyn, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: J. Price has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: A.J. Hey-Cunningham has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: J. Maloney reports unrestricted educational grants to her institution (Lung Foundation Australia) from Boehringer Ingelheim and Roche Australia, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: A.K. Teoh has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: A.L. Watson has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: A.E. Holland reports grants from National Health and Medical Research Council Australia, during the conduct of the study; and unrestricted research grants from Boehringer Ingelheim and Roche, outside the submitted work.

Support statement: This study was funded by the Centre of Research Excellence in Pulmonary Fibrosis (funded by the National Health and Medical Council (Australia); GNT1116371) and supported by Foundation partner Boehringer Ingelheim and Program Partners Roche and Galapagos. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.Schoenheit G, Becattelli I, Cohen AH. Living with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an in-depth qualitative survey of European patients. Chron Respir Dis 2011; 8: 225–231. doi: 10.1177/1479972311416382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bajwah S, Ross JR, Peacock JL, et al. Interventions to improve symptoms and quality of life of patients with fibrotic interstitial lung disease: a systematic review of the literature. Thorax 2013; 68: 867–879. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bajwah S, Higginson IJ, Ross JR, et al. The palliative care needs for fibrotic interstitial lung disease: a qualitative study of patients, informal caregivers and health professionals. Palliat Med 2013; 27: 869–876. doi: 10.1177/0269216313497226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carvajalino S, Reigada C, Johnson MJ, et al. Symptom prevalence of patients with fibrotic interstitial lung disease: a systematic literature review. BMC Pulm Med 2018; 18: 78. doi: 10.1186/s12890-018-0651-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holland AE, Fiore JF Jr., Bell EC, et al. Dyspnoea and comorbidity contribute to anxiety and depression in interstitial lung disease. Respirology 2014; 19: 1215–1221. doi: 10.1111/resp.12360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hui D. Definition of supportive care: does the semantic matter? Curr Opin Oncol 2014; 26: 372–379. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duck A, Pigram L, Errhalt P, et al. IPF care: a support program for patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis treated with pirfenidone in Europe. Adv Ther 2015; 32: 87–107. doi: 10.1007/s12325-015-0183-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russell AM, Ripamonti E, Vancheri C. Qualitative European survey of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: patients’ perspectives of the disease and treatment. BMC Pulm Med 2016; 16: 10. doi: 10.1186/s12890-016-0171-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009; 339: b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kmet LM, Lee RC, Cook LS. Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. Alberta, Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kotronoulas G, Papadopoulou C, Burns-Cunningham K, et al. A systematic review of the supportive care needs of people living with and beyond cancer of the colon and/or rectum. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2017; 29: 60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2017.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albright K, Walker T, Baird S, et al. Seeking and sharing: why the pulmonary fibrosis community engages the web 2.0 environment. BMC Pulm Med 2016; 16: 4. doi: 10.1186/s12890-016-0167-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belkin A, Albright K, Swigris JJ. A qualitative study of informal caregivers’ perspectives on the effects of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. BMJ Open Respir Res 2014; 1: e000007. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2013-000007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonella F, Wijsenbeek M, Molina-Molina M, et al. European IPF Patient Charter: unmet needs and a call to action for healthcare policymakers. Eur Respir J 2016; 47: 597–606. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01204-2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bridges JFP, Paly VF, Barker E, et al. Identifying the benefits and risks of emerging treatments for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a qualitative study. Patient 2014; 8: 85–92. doi: 10.1007/s40271-014-0081-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burnett K, Glaspole I, Holland AE. Understanding the patient's experience of care in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology 2019; 24: 270–277. doi: 10.1111/resp.13414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collard HR, Tino G, Noble PW, et al. Patient experiences with pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Med 2007; 101: 1350–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giot C, Maronati M, Becattelli I, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an EU patient perspective survey. Curr Respir Med Rev 2013; 9: 112–119. doi: 10.2174/1573398X113099990010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graney BA, Wamboldt FS, Baird S, et al. Informal caregivers experience of supplemental oxygen in pulmonary fibrosis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2017; 15: 133. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0710-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindell KO, Kavalieratos D, Gibson KF, et al. The palliative care needs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a qualitative study of patients and family caregivers. Heart Lung 2017; 46: 24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2016.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morisset J, Dubé B-P, Garvey C, et al. The unmet educational needs of patients with interstitial lung disease. Setting the stage for tailored pulmonary rehabilitation. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016; 13: 1026–1033. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201512-836OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Overgaard D, Kaldan G, Marsaa K, et al. The lived experience with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a qualitative study. Eur Respir J 2016; 47: 1472–1480. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01566-2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramadurai D, Corder S, Churney T, et al. Understanding the informational needs of patients with IPF and their caregivers: “You get diagnosed, and you ask this question right away, what does this mean?”. BMJ Open Qual 2018; 7: e000207. doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2017-000207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Manen MJG, Kreuter M, van den Blink B, et al. What patients with pulmonary fibrosis and their partners think: a live, educative survey in the Netherlands and Germany. ERJ Open Res 2017; 3: 00065-2016. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00065-2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bajwah S, Koffman J, Higginson IJ, et al. ‘I wish I knew more …’ the end-of-life planning and information needs for end-stage fibrotic interstitial lung disease: views of patients, carers and health professionals. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013; 3: 84–90. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graney BA, Wamboldt FS, Baird S, et al. Looking ahead and behind at supplemental oxygen: a qualitative study of patients with pulmonary fibrosis. Heart Lung 2017; 46: 387–393. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2017.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swigris JJ, Stewart AL, Gould MK, et al. Patients’ perspectives on how idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis affects the quality of their lives. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2005; 3: 61. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-3-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duck A, Spencer LG, Bailey S, et al. Perceptions, experiences and needs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Adv Nurs 2015; 71: 1055–1065. doi: 10.1111/jan.12587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holland AE, Fiore JF Jr., Goh N, et al. Be honest and help me prepare for the future: what people with interstitial lung disease want from education in pulmonary rehabilitation. Chron Respir Dis 2015; 12: 93–101. doi: 10.1177/1479972315571925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sampson C, Gill BH, Harrison NK, et al. The care needs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and their carers (CaNoPy): results of a qualitative study. BMC Pulm Med 2015; 15: 155. doi: 10.1186/s12890-015-0145-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maher T, Swigris JJ, Kreuter M, et al. Identifying barriers to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis treatment: a survey of patient and physician views. Respiration 2018; 96: 514–524. doi: 10.1159/000490667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pooler C, Richman-Eisenstat J, Kalluri M. Early integrated palliative approach for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a narrative study of bereaved caregivers’ experiences. Palliat Med 2018; 32: 1455–1464. doi: 10.1177/0269216318789025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramadurai D, Corder S, Churney T, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: educational needs of health-care providers, patients, and caregivers. Chron Respir Dis 2019; 16: 1–8. doi: 10.1177/1479973119858961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Senanayake S, Harrison K, Lewis M, et al. Patients’ experiences of coping with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and their recommendations for its clinical management. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0197660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shah RJ, Collard HR, Morisset J. Burden, resilience and coping in caregivers of patients with interstitial lung disease. Heart Lung 2018; 47: 264–268. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2018.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conoscenti CS, Rubin EM, Sapiro N. Patient journey with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF): a breathtaking experience. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 187: A1090. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gillon S, Sutherland T, Slough J. Improving palliative care for patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Palliat Med 2016; 30: Poster 189 [ 10.1177/0269216316631462]. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Killin CR, Hayes J, Byrne A, et al. Quality of care for patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis – perspectives from patients and carers. Palliat Med 2010; 24: S178–S179. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wall J, Crosby V, Hussain A, et al. Establishing the palliative and supportive care needs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and non specific interstitial pneumonia. Thorax 2013; 68: A165–A1A6. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204457.350 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wright J, Cove J, Russell AM, et al. Pilot study to test the feasibility of introducing palliative care as part of a psychological support workshop for patients newly diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and their families. Palliat Med 2016; 30: P324[ 10.1177/0269216316646056]. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Belz A, Debowska P, Warzecha J, et al. Patients’ expectations and quality of life before introduction of pirfenidone used in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Resp J 2018; 52: Suppl. 62, PA4784. [Google Scholar]

- 42.McLean A, Webster S, Fry M, et al. Priorities and expectations of patients attending a multidisciplinary interstitial lung disease clinic. Respirology 2018; 23: 146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jo HE, Prasad JD, Troy LK, et al. Diagnosis and management of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Thoracic society of Australia and New Zealand and Lung Foundation Australia position statements summary. Med J Aust 2018; 208: 82–88. doi: 10.5694/mja17.00799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weiss MG, Ramakrishna J, Somma D. Health-related stigma: rethinking concepts and interventions. Psychol Health Med 2006; 11: 277–287. doi: 10.1080/13548500600595053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rose S, Paul C, Boyes A, et al. Stigma-related experiences in non-communicable respiratory diseases: a systematic review. Chron Respir Dis 2017; 14: 199–216. doi: 10.1177/1479972316680847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

ERR-0125-2019_Supplementary_tables ERR-0125-2019_Supplementary_tables (331KB, pdf)