Abstract

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) is a complex and heterogeneous interstitial lung disease (ILD) that occurs when susceptible individuals develop an exaggerated immune response to an inhaled antigen. In this review, we discuss the latest guidelines for the diagnostic evaluation of patients with suspected HP, the importance of identifying patients with fibrotic and progressive disease, and the evidence supporting the drugs commonly used in the treatment of HP. Differential diagnosis of HP can be challenging and requires a thorough exposure history, multidisciplinary discussion of clinical and radiologic data, and, in some cases, assessment of bronchoalveolar lavage lymphocytosis and histopathologic findings. Patients with HP may be categorised as having non-fibrotic or fibrotic HP. The presence of fibrosis is associated with worse outcomes. A proportion of patients with fibrotic HP develop a progressive phenotype, characterised by worsening fibrosis, decline in lung function and early mortality. There are no established guidelines for the treatment of HP. Antigen avoidance should be implemented wherever possible. Immunosuppressants are commonly used in patients with HP but have not been shown to slow the worsening of fibrotic disease. Nintedanib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for slowing the progression of chronic fibrosing ILDs with a progressive phenotype, including progressive fibrotic HP. Non-pharmacological interventions, such as oxygen therapy, pulmonary rehabilitation and supportive care, may be important components of the overall care of patients with progressive HP.

Short abstract

Guideline statements for the diagnosis of hypersensitivity pneumonitis have recently been published by the ATS/JRS/ALAT and CHEST. This review examines differences in the two guideline statements and discusses current management options. https://bit.ly/3o6uJh2

Introduction

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) is a complex interstitial lung disease (ILD) caused by exposure to an inhaled antigen [1, 2]. Recently, two guidelines for the diagnosis of HP were published by the American Thoracic Society/Japanese Respiratory Society/Asociación Latinoamericana de Tórax (ATS/JRS/ALAT) [1] and the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) [2]. As well as providing algorithms to guide the evaluation of patients with suspected HP, these guidelines proposed that clinical, radiologic and pathologic findings be used to categorise patients as having fibrotic or non-fibrotic HP. HP is a disease of many faces – from inflammatory self-limiting disease to relapsing or progressive inflammatory disease to chronic fibrotic disease resembling idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) – and its phenotype has important implications for prognosis and treatment. In this article, we discuss the differential diagnosis of HP, the importance of identifying patients with fibrotic and progressive disease, and the evidence available to guide the management of fibrotic and non-fibrotic HP.

Aetiology and pathogenesis

HP occurs when susceptible individuals develop an exaggerated immune response following inhalation of an inciting antigen or mixture of antigens [3, 4]. Several genetic polymorphisms, including those in major histocompatibility complex class II, have been associated with susceptibility to HP [5–8]. The MUC5B allele rs35705950 has been associated with a greater extent of radiographic fibrosis, and short telomere length has been associated with worse survival [7]. Transcriptomic analysis of lung tissue has revealed genetic signatures common to HP and IPF, as well as genes uniquely expressed in HP [9]. Inciting antigens may be microbial, plant, avian or animal-based proteins, or inorganic low -molecular weight chemical agents that combine with host proteins to form haptens [1–3, 10]. Exposure may occur in home, work or recreational environments [1, 3, 11]. Viral infections may trigger or exacerbate hypersensitivity to environmental antigens by increasing the antigen-presenting capacity of alveolar macrophages, decreasing the clearance of antigens, and stimulating the release of inflammatory cytokines [12]. Tobacco smoking also has an impact on immune reactivity to inciting antigens, driving the pathogenetic process towards fibrotic disease [13, 14].

Inflammation in HP is mediated by both humoral and cellular mechanisms [1, 4]. Following antigen exposure and processing by the innate immune system, the inflammatory response is predominantly mediated by T-helper cells and antigen-specific immunoglobulin (Ig) G antibodies, leading to the accumulation of lymphocytes and the formation of granulomas [4]. While the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis is not fully understood, it is believed that in fibrotic disease, abnormal repair mechanisms following recurrent alveolar epithelial injury lead to fibroblast activation and proliferation, the accumulation of extracellular matrix, and the eventual destruction of the lung architecture [3, 4, 15].

Classification

Historically, HP was classified as acute, sub-acute or chronic, based on the duration of symptoms [16], but this classification is now regarded as of little clinical value due to difficulties in distinguishing these categories and their lack of association with outcomes [17]. As the presence of fibrosis is a critical determinant of prognosis [18–22], the latest guidelines for the diagnosis of HP propose that patients be categorised as having non-fibrotic (purely inflammatory) HP or fibrotic HP (mixed inflammatory and fibrotic or purely fibrotic) [1, 2]. Patients in whom a culprit exposure has not been identified but who otherwise have features typical of HP may be described as having “cryptogenic HP” or “HP of undetermined cause” [1].

Diagnostic evaluation

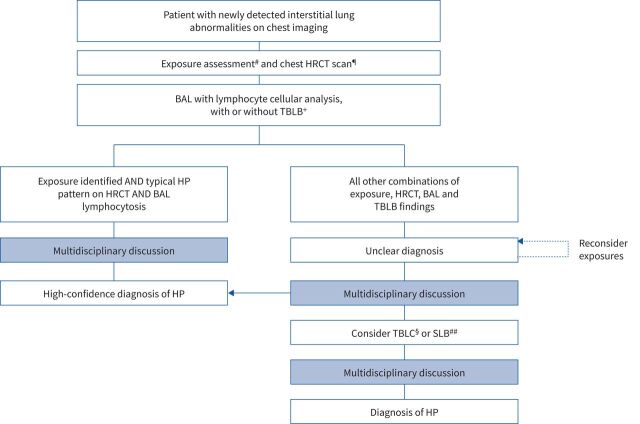

The diagnosis of HP requires multidisciplinary discussion based on clinical, radiologic and, in some cases, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) lymphocytosis and histopathologic data [1, 2]. Based on the CHEST guidelines, a confident diagnosis of HP can be made in patients who have an identified exposure and a typical HP pattern on a high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan [2]. Based on the ATS/JRS/ALAT guidelines, a confident diagnosis of HP also requires evidence of BAL lymphocytosis (figure 1) [1]. Differentiating HP from other ILDs can be challenging, as the clinical, radiologic and histopathologic features of HP are highly variable and overlap with those of other ILDs. Inflammatory disease may go unrecognised, while fibrotic disease may be misdiagnosed as IPF [23]. Physicians should be suspicious of HP in all patients with evidence of ILD. Potential exposures should be investigated using a structured approach [11, 24]. However, for many patients with HP, the causative antigen will remain unidentified [25, 26].

FIGURE 1.

Algorithm for the diagnosis of hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP). Reproduced from [1] with permission. #: exposure assessment includes a thorough clinical history and/or serum immunoglobulin G testing against potential antigens associated with HP and/or, in centres with the appropriate expertise and experience, specific inhalational challenge testing. ¶: high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) should be performed using the technique described in the guidelines and then reviewed with a thoracic radiologist. +: transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB) is suggested for patients with potential non-fibrotic HP. §: transbronchial lung cryobiopsy (TBLC) is suggested for patients with potential non-fibrotic HP, depending on local expertise. ##: surgical lung biopsy (SLB) is infrequently considered in patients with non-fibrotic HP. BAL: bronchoalveolar lavage.

The role of HRCT

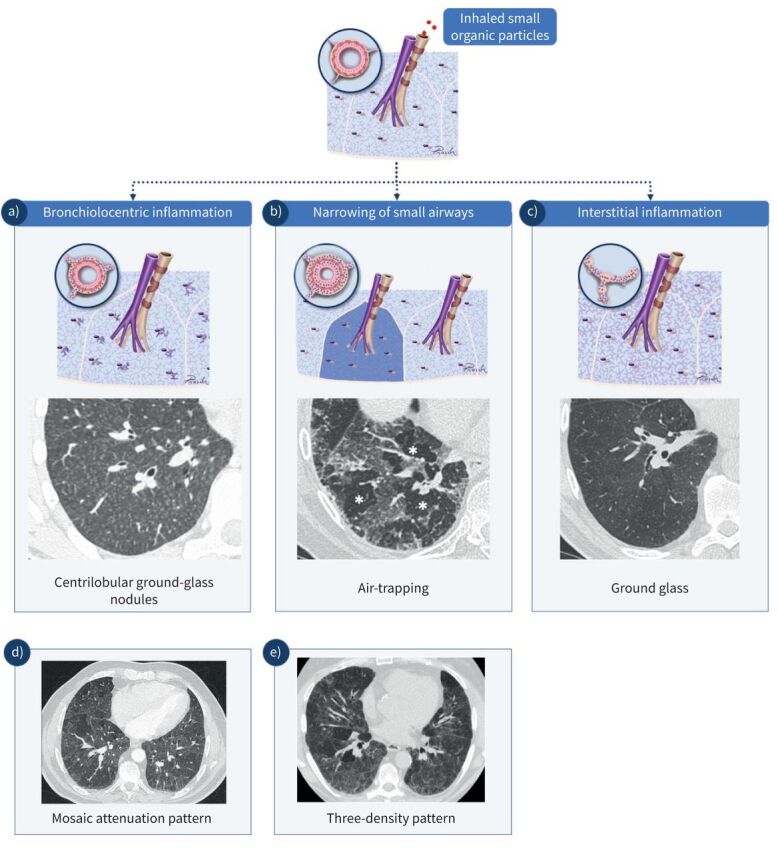

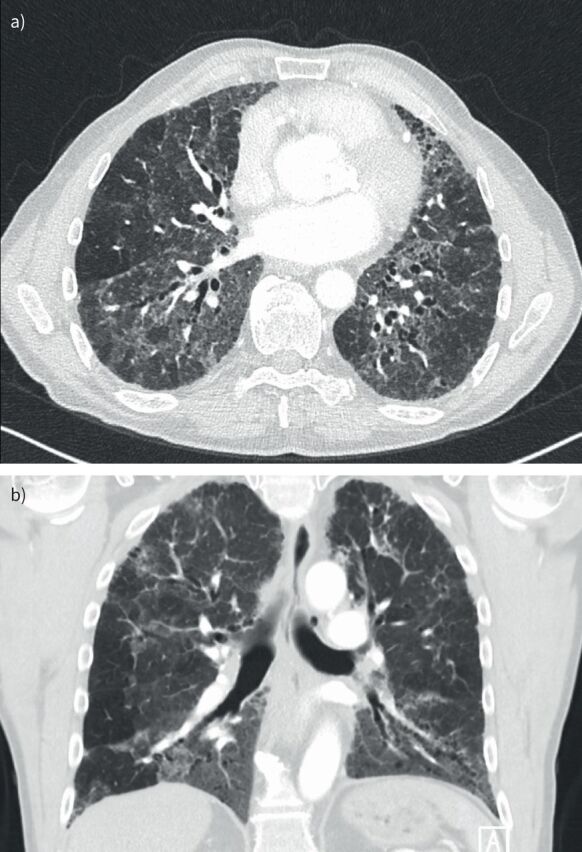

HRCT plays a key role in the diagnosis of HP and in the detection of fibrosis. The typical computed tomography (CT) manifestations of HP reflect the bronchiolocentric inflammation seen on histopathology, which leads to small, ill-defined ground-glass nodules with a profuse distribution across all lung zones (figure 2). This bronchiolocentric inflammation may also lead to a narrowing of small airways, leading to lobular air-trapping. More extensive interstitial inflammation may lead to ground-glass opacities and an increase in lung density with preserved visibility of the vessels and bronchial walls. In HP, this ground glass typically shows a patchy distribution referred to as mosaic attenuation (figures 2 and 3). The combination of a patchy distribution of normal-appearing lobules, ground glass, and lobules of decreased lung density and vessel size is called the three-density pattern (formerly the head-cheese sign) and is the CT pattern of greatest specificity for HP. Signs of fibrosis include a combination of reticular abnormalities and/or ground glass with traction bronchiolectasis or bronchiectasis, a loss of lobar volume, and honeycombing (figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) findings in hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP). a) The reaction to inhaled antigens leads to bronchiolocentric inflammation, which on computed tomography can be seen as ill-defined centrilobular ground-glass nodules. b) Narrowing of the involved small airways by the inflammatory process may lead to retained air in the involved lobules on expiratory scans (air-trapping). The involved lobules appear darker on the expiratory scan (*). c) Diffuse interstitial inflammation leads to an increase in lung density with visibility of vessels and bronchial walls and is called ground glass. d) In HP, lobular areas with ground glass are frequently intermixed with lobules of normal appearance, leading to a patchwork of lobules with differing density, which is called mosaic attenuation. e) A patchwork of lung lobules with normal density, with lobules with ground-glass attenuation and lobules with decreased density and decreased vessel size due to air-trapping is called the “three-density pattern” and is the most specific sign for HP on HRCT. This pattern is more accentuated on expiratory scans.

FIGURE 3.

Typical fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis on high-resolution computed tomography. Computed tomography (CT) scan of a 64-year-old male patient. a) Axial CT scan. b) Coronal CT scan. Mosaic attenuation at inspiration affecting all lung zones with signs of fibrosis (traction bronchiectasis) with no features suggesting an alternative diagnosis.

The role of BAL lymphocytosis

Interpretation of BAL lymphocytosis is not entirely straightforward, as lymphocytosis occurs in several ILDs and may vary broadly between fibrotic and non-fibrotic forms of HP. BAL lymphocytosis may be unnecessary where there is a high pre-test probability of HP, since it will not greatly influence the probability of the diagnosis. It has greatest value when there is a high pre-test probability of HP based on either exposure history or imaging, but discordance between the history and imaging lowers overall diagnostic confidence. In this setting, a BAL lymphocyte count >30% may increase the diagnostic confidence for HP to highly probable and spare the patient further invasive procedures. In patients with fibrotic ILD, a BAL lymphocyte count >30% is highly specific for HP, but the absence of lymphocytosis does not exclude HP as a diagnostic consideration, and lung biopsy should be pursued when appropriate. The absence of lymphocytosis in non-fibrotic disease lowers the probability enough to exclude the possibility of HP.

Ultimately, the value of BAL lymphocytosis largely depends on the pre-test probability of HP. The ATS/JRS/ALAT guidelines recommend BAL with assessment of lymphocytosis, as well as an exposure history and an HRCT scan, in patients with newly detected ILD prior to multidisciplinary discussion [1], while the CHEST guidelines recommend multidisciplinary discussion of exposures and HRCT pattern before considering BAL, and not undertaking BAL in patients with an exposure history, clinical context and HRCT pattern typical for HP [2].

The search for an exposure

The most basic method to identify potential exposures is a carefully taken history using a structured questionnaire [11, 24], but it is unlikely that any questionnaire would be appropriate in all settings. Specific IgG tests can be valuable to pursue suspicious exposures or point towards an as-yet-undetected exposure, but there is a lack of well-defined predicted values for specific IgGs and the tests cannot differentiate between sensitisation and disease [1, 11]. Exposure tests such as the specific inhalation challenge are highly sensitive and specific for HP but can only be performed at expert centres. The inhalation challenge might include commercially available antigens as well as antigens obtained from the patient's environment [27].

The role of lung biopsy

Lung biopsy should be avoided in patients in whom a confident diagnosis of HP can be made following multidisciplinary discussion of clinical and radiologic findings, exposure history, and BAL lymphocytosis (figure 4) [1, 2]. In patients who have a suspicion for HP but for whom a confident diagnosis cannot be made based on the available data, obtaining lung tissue is recommended if warranted based on the risk:benefit for the individual patient. No recommendation for the use of transbronchial cryobiopsy over surgical lung biopsy was made in the ATS/JRS/ALAT or CHEST guidelines; however, the findings of a systematic review and meta-analysis of data from 447 patients suggest that transbronchial cryobiopsy may pose a lower risk of morbidity and mortality [28].

FIGURE 4.

Diagnostic algorithm for hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) in patients with no indication for lung biopsy based on the CHEST guidelines. Reproduced and modified from [2] with permission. BAL: bronchoalveolar lavage; HRCT: high-resolution computed tomography; MDD: multidisciplinary discussion.

The complex spectrum of pathologic variation makes it challenging to interpret biopsy findings in isolation. Biopsies should be reviewed by a pathologist experienced in ILD in the context of clinical and radiologic findings. The ATS/JRS/ALAT and CHEST guidelines propose the same general criteria for pathologic findings in non-fibrotic and fibrotic HP [1, 2]. Typical non-fibrotic HP exhibits four key features: 1) small airway involvement, 2) uniform cellular interstitial inflammation that is 3) predominantly lymphocytic, with 4) at least a single, poorly formed granuloma and/or multinucleated giant cell. The uniform cellular inflammation may manifest as inflammation of airway walls, cellular bronchiolitis, or regions of cellular non-specific interstitial pneumonitis (NSIP). The absence of granulomas or multi-nucleated giant cells is still considered compatible with HP, if the other three features are present. Where one or two of the four features are present, other minor features might support a diagnosis if the clinical and radiologic features are supportive. These include small foci of organizing pneumonia (Masson bodies), foamy macrophages, cholesterol clefts, Schaumann bodies, calcium oxalate crystals and widespread peribronchiolar metaplasia.

The histological pattern of fibrotic HP may be similar to that of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), as seen in IPF [21]. Typical fibrotic HP has three key features: 1) airway-centred fibrosis with or without widespread peribronchiolar metaplasia, 2) fibrosing interstitial pneumonia, which might have the appearance of fibrotic NSIP, UIP, isolated peribronchiolar fibrosis, or fibrotic lung disease that defies a specific classification, and 3) poorly formed granulomas. Peribronchiolar metaplasia can occur in several conditions, but if >50% of the bronchioles are affected, HP is more likely. As with non-fibrotic HP, the absence of granulomas or multi-nucleated giant cells is still considered compatible with fibrotic HP if the other features are present. In cases where there is more pronounced peribronchiolar inflammation, an in-depth clinical and radiologic assessment for gastro-oesophageal disease should be undertaken, as chronic aspiration can resemble fibrotic HP in its pathology [29].

Progression of HP

HP has a heterogeneous and unpredictable clinical course. A proportion of patients with fibrotic HP develop progressive disease characterised by increasing fibrotic abnormalities on HRCT, worsening lung function, and early mortality [30–33]. Some studies have shown that the rate of decline in forced vital capacity (FVC) and survival are similar between patients with progressive HP and IPF [30, 33, 34]. Acute deteriorations in lung function (acute exacerbations) may occur in patients with HP and are associated with high mortality [35–37].

Several risk factors for ILD progression and mortality in patients with HP have been identified (table 1). Factors associated with worse survival include an inability to remove the inciting antigen, older age, male sex, and a history of smoking [20, 22, 25, 38, 39]. Lower BAL lymphocytosis is associated with reduced survival [22, 40], likely because patients with higher BAL lymphocytosis are those with non-fibrotic HP. The presence of fibrosis on HRCT [18, 25, 26, 31, 41] and the extent of fibrosis [20, 42, 43], honeycombing [32, 42, 44] and traction bronchiectasis [42] on HRCT have been associated with mortality in patients with HP, while air-trapping and mosaic attenuation have been associated with improved survival [45]. Specific histopathologic features, such as a UIP pattern, dense collagen fibrosis, fibroblast foci and microscopic honeycombing, have also been associated with mortality in patients with HP [22, 41]. Lower FVC [20, 41] or diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) [22] or a decline in FVC [46] reflect the progression of ILD and have been associated with mortality in patients with HP, consistent with observations in other fibrosing ILDs [47–50]. It is important to note that although risk factors for the progression of ILD have been identified, the course of disease for an individual patient remains largely unpredictable. Patients with HP should be monitored for disease progression, including regular reviews of symptoms and pulmonary function tests, and repeat HRCT scans as indicated.

TABLE 1.

Factors associated with mortality in patients with HP

| Intrinsic factors | Older age |

| Male sex | |

| Genetic predisposition | |

| Exposures | Unidentifiable inciting antigen |

| Duration of exposure to inciting antigen | |

| History of smoking | |

| Physiology | Low FVC |

| Low DLCO | |

| Decline in FVC | |

| Lower BAL lymphocytosis | |

| Radiology | Presence of fibrosis on HRCT |

| Extent of fibrosis on HRCT | |

| UIP pattern on HRCT | |

| Histology | UIP pattern |

| Fibrotic NSIP pattern |

BAL: bronchoalveolar lavage; DLCO: diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide; FVC: forced vital capacity; HRCT: high-resolution computed tomography; NSIP: non-specific interstitial pneumonia; UIP: usual interstitial pneumonia.

Management of HP

Identification and elimination of the inciting antigen are critical to improving outcomes in patients with HP [25] but can be difficult to achieve in practice. An environmental hygienist may be enlisted to perform an assessment of indoor spaces and advise on how exposure sources might be mitigated [11].

There is no established algorithm for the pharmacological treatment of HP. HP may initially respond to corticosteroids, but there is little evidence that corticosteroids provide a long-term benefit or slow the progression of fibrotic HP [26, 40, 51, 52]. Patients with HP commonly receive immunosuppressants [53] but the evidence base to inform their use is poor. Concerns have been raised over the chronic use of immunosuppression in patients with HP given the harmful effects of prednisone plus azathioprine observed in patients with IPF in the PANTHER-IPF (Prednisone, Azathioprine, and N-Acetylcysteine: A Study That Evaluates Response in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis) trial [54]. Some retrospective analyses have shown an improvement in DLCO or FVC after a year of treatment with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) or azathioprine [55–57]. However, a retrospective study found no difference in lung function decline or survival between patients treated with azathioprine or MMF plus prednisone versus prednisone alone [58]. A retrospective study of 20 patients showed that treatment with rituximab for 6 months led to stabilization or improvement of FVC and DLCO in patients with HP whose disease had not improved following antigen avoidance and corticosteroid therapy [59].

It has been postulated that once ILD has become fibrotic, a therapy that inhibits fibrotic pathways is required to slow its progression, irrespective of the initial trigger [60, 61]. However, there remains no consensus as to when antifibrotic therapy should be initiated in patients with fibrotic HP. Nintedanib, an intracellular inhibitor of tyrosine kinases [61], has been licensed in several countries for the treatment of chronic fibrosing ILDs with a progressive phenotype. In the INBUILD trial in 663 patients with fibrosing ILDs other than IPF who met criteria for ILD progression within the previous 2 years despite management deemed appropriate in clinical practice, nintedanib slowed the rate of decline in FVC (mL·year−1) over 52 weeks by 57% compared with placebo [62, 63]. Over the whole trial, the risk of an acute exacerbation of ILD or death was also reduced in the nintedanib group [64]. Patients with fibrotic HP comprised 173 (26%) of the enrolled patients. Although the INBUILD trial was not designed or powered to study individual ILDs, subgroup analyses suggested that the rate of FVC decline [34], the effect of nintedanib on reducing the rate of FVC decline [65], and the adverse events associated with nintedanib [65] were consistent across subgroups based on ILD diagnosis.

Pirfenidone, a US Food and Drug Administration approved treatment for IPF, has not been investigated as a treatment for HP in randomised double-blind controlled trials. A retrospective study of medical records from 23 patients with HP found that change in vital capacity in the 6 months after initiation of pirfenidone was significantly lower than in the 6 months prior to initiation [66]. An open-label study in 22 patients with fibrotic HP found no significant difference in change in FVC after 1 year of treatment in patients who were randomised to receive pirfenidone, prednisone plus azathioprine compared to prednisone plus azathioprine only [67]. The RELIEF study, which investigated the effects of pirfenidone in patients with progressive pulmonary fibrosis due to connective tissue disease, fibrotic non-specific interstitial pneumonia, HP, or asbestosis, despite standard treatment, was prematurely terminated due to low recruitment, but an analysis of data from the 127 patients enrolled, of whom 57 had HP, demonstrated a smaller decline in FVC % predicted over 48 weeks in patients who received pirfenidone compared with placebo [68].

While the evidence base is insufficient to define a treatment algorithm for HP, in clinical practice, a phenotype-based approach may be applied. In cases of non-fibrotic HP where the inciting antigen has been removed and lung function is not severely impaired, it may be appropriate not to initiate therapy but to ensure the patient is closely monitored. Corticosteroids should be considered in patients with severe lung function impairment or progressive disease. In cases of fibrotic HP and severe or progressive disease, immunosuppressive therapy may be considered. Anti-fibrotic therapy should be considered in patients with progressive fibrosing ILD.

Guidelines issued by the ATS recommend the use of long-term oxygen therapy and ambulatory oxygen in patients with ILD and severe chronic resting hypoxaemia, and the use of ambulatory oxygen in patients with ILD who are mobile outside the home and require continuous-flow oxygen during exertion [69]. The guidelines emphasise that patients and their caregivers should receive training on the use of oxygen therapy to facilitate adherence and ensure safety. Non-pharmacological interventions, such as pulmonary rehabilitation, vaccinations, supportive care and participation in patient groups, can be an important part of the overall care of patients with progressive ILD [70, 71]. Management of common comorbidities of HP such as gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [72] may also help to improve patients’ outcomes and quality of life.

Lung transplant improves survival in select patients with progressive fibrotic ILDs. Among 31 patients with HP who underwent lung transplantation at a single US centre between 2000 and 2013, 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rates were 96%, 89% and 89%, respectively [73]. Guidelines from the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation recommend that patients with ILD be referred for lung transplant evaluation at an early stage to maximise the chance that they will be eligible for listing [74].

Conclusions

HP is a complex and heterogeneous disease. Making a diagnosis of HP can be challenging as its clinical, radiologic and histopathologic features overlap with those of other ILDs and it may not be possible to identify a culprit exposure. The presence of lung fibrosis on HRCT has important implications for prognosis and management. Patients with HP should be regularly monitored to assess for progression. Wherever possible, the inciting antigen should be avoided. Immunosuppression is commonly used in the treatment of HP but has not been shown to slow the progression of fibrotic disease. Nintedanib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, is an approved treatment option for fibrotic HP with a progressive phenotype.

Footnotes

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed.

Conflict of interest: M. Hamblin reports support for the present manuscript from FleishmanHillard (funded by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc.). Grants or contracts received from Biogen, Inc, Boehringer Ingelheim, Inc, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Inc, Fibrogen, Inc, Galapagos, Inc, Galecto, Inc, Hoffman LaRoche, Inc, Promedior, Inc, Mallinkrodt, Inc, United Therapeutics, outside the submitted work. Payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events received from Boehringer Ingelheim, Inc, and Genentech, Inc, outside the submitted work. Support for attending meetings and/or travel from Boehringer Ingelheim, Inc, outside the submitted work. Participation on an Advisory Board for United Therapeutics. President of Kansas City Foundation for Pulmonary Fibrosis 501c3 advocacy group for patients with pulmonary fibrosis.

Conflict of interest: H. Prosch reports support for the present manuscript from FleishmanHillard (funded by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc.). Grants or contracts received from Boehringer Ingelheim, outside the submitted work. Payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, MSD, BMS, Takeda, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: M. Vašáková reports support for the present manuscript from FleishmanHillard (funded by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc.). Consulting fees received from Boehringer Ingelheim and Roche, outside the submitted work. Payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events received from Boehringer Ingelheim and Roche, outside the submitted work. Support for attending meetings and/or travel received from Boehringer Ingelheim and Roche, outside the submitted work. Participation on an Advisory Board for Boehringer Ingelheim and Roche. President of Czech Pneumologic and Phtisiologic Society, and has been the Deputy Minister of Health for the Czech Republic since April 2021.

Support statement: The authors meet criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE). The authors did not receive payment for development of this article. Editorial support was provided by Julie Fleming, BSc and Wendy Morris, MSc of FleishmanHillard, London, UK, which was contracted and funded by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (BIPI). Boehringer Ingelheim was given the opportunity to review the article for medical and scientific accuracy as well as intellectual property considerations. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Ryerson CJ, et al. Diagnosis of hypersensitivity pneumonitis in adults. An official ATS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020; 202: e36–e69. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202005-2032ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernández Pérez ER, Travis WD, Lynch DA, et al. Executive summary diagnosis and evaluation of hypersensitivity pneumonitis: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest 2021; 160: 595–615. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.03.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selman M, Pardo A, King TE, Jr. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: insights in diagnosis and pathobiology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012; 186: 314–324. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0513CI [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vašáková M, Selman M, Morell F, et al. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: current concepts of pathogenesis and potential targets for treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 200: 301–308. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201903-0541PP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Camarena A, Juárez A, Mejía M, et al. Major histocompatibility complex and tumor necrosis factor-alpha polymorphisms in pigeon breeder's disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 163: 1528–1533. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.2004023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newton CA, Batra K, Torrealba J, et al. Telomere-related lung fibrosis is diagnostically heterogeneous but uniformly progressive. Eur Respir J 2016; 48: 1710–1720. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00308-2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ley B, Newton CA, Arnould I, et al. The MUC5B promoter polymorphism and telomere length in patients with chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis: an observational cohort-control study. Lancet Respir Med 2017; 5: 639–647. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30216-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ley B, Torgerson DG, Oldham JM, et al. Rare protein-altering telomere-related gene variants in patients with chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 200: 1154–1163. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201902-0360OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furusawa H, Cardwell JH, Okamoto T, et al. Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, an interstitial lung disease with distinct molecular signatures. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020; 202: 1430–1444. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202001-0134OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee CT, Adegunsoye A, Chung JH, et al. Characteristics and prevalence of domestic and occupational inhalational exposures across interstitial lung diseases. Chest 2021; 160: 209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.02.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johannson KA, Barnes H, Bellanger AP, et al. Exposure assessment tools for hypersensitivity pneumonitis. An official American Thoracic Society workshop report. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2020; 17: 1501–1509. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202008-942ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cormier Y, Israël-Assayag E. The role of viruses in the pathogenesis of hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2000; 6: 420–423. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200009000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McSharry C, Banham SW, Boyd G. Effect of cigarette smoking on the antibody response to inhaled antigens and the prevalence of extrinsic allergic alveolitis among pigeon breeders. Clin Allergy 1985; 15: 487–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1985.tb02299.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohtsuka Y, Munakata M, Tanimura K, et al. Smoking promotes insidious and chronic farmer's lung disease, and deteriorates the clinical outcome. Intern Med 1995; 34: 966–971. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.34.966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selman M, Pardo A. When things go wrong: exploring possible mechanisms driving the progressive fibrosis phenotype in interstitial lung diseases. Eur Respir J 2021; 58: 2004507. doi: 10.1183/13993003.04507-2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richerson HB, Bernstein IL, Fink JN, et al. Guidelines for the clinical evaluation of hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Report of the subcommittee on hypersensitivity pneumonitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1989; 84: 839–844. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(89)90349-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lacasse Y, Selman M, Costabel U, et al. Classification of hypersensitivity pneumonitis: a hypothesis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2009; 149: 161–166. doi: 10.1159/000189200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vourlekis JS, Schwarz MI, Cherniack RM, et al. The effect of pulmonary fibrosis on survival in patients with hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Am J Med 2004; 116: 662–668. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.12.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanak V, Golbin JM, Hartman TE, et al. High-resolution CT findings of parenchymal fibrosis correlate with prognosis in hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Chest 2008; 134: 133–138. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-3005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mooney JJ, Elicker BM, Urbania TH, et al. Radiographic fibrosis score predicts survival in hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Chest 2013; 144: 586–592. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Churg A, Bilawich A, Wright JL. Pathology of chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. What is it? What are the diagnostic criteria? Why do we care? Arch Pathol Lab Med 2018; 142: 109–119. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2017-0173-RA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ojanguren I, Morell F, Ramón MA, et al. Long-term outcomes in chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Allergy 2019; 74: 944–952. doi: 10.1111/all.13692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morell F, Villar A, Montero MÁ, et al. Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis in patients diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a prospective case-cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2013; 1: 685–694. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70191-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barnes H, Morisset J, Molyneaux P, et al. A systematically derived exposure assessment instrument for chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Chest 2020; 157: 1506–1512. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fernández Pérez ER, Swigris JJ, Forssén AV, et al. Identifying an inciting antigen is associated with improved survival in patients with chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Chest 2013; 144: 1644–1651. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Sadeleer LJ, Hermans F, De Dycker E, et al. Effects of corticosteroid treatment and antigen avoidance in a large hypersensitivity pneumonitis cohort: a single-centre cohort study. J Clin Med 2018; 8: 14. doi: 10.3390/jcm8010014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morell F, Ojanguren I, Cruz MJ. Diagnosis of occupational hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2019; 19: 105–110. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ravaglia C, Bonifazi M, Wells AU, et al. Safety and diagnostic yield of transbronchial lung cryobiopsy in diffuse parenchymal lung diseases: a comparative study versus video-assisted thoracoscopic lung biopsy and a systematic review of the literature. Respiration 2016; 91: 215–227. doi: 10.1159/000444089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cardasis JJ, MacMahon H, Husain AN. The spectrum of lung disease due to chronic occult aspiration. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014; 11: 865–873. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201310-360OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adegunsoye A, Oldham JM, Chung JH, et al. Phenotypic clusters predict outcomes in a longitudinal interstitial lung disease cohort. Chest 2018; 153: 349–360. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.09.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fernández Pérez ER, Kong AM, Raimundo K, et al. Epidemiology of hypersensitivity pneumonitis among an insured population in the United States: a claims-based cohort analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2018; 15: 460–469. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201704-288OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salisbury ML, Gu T, Murray S, et al. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: radiologic phenotypes are associated with distinct survival time and pulmonary function trajectory. Chest 2019; 155: 699–711. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.08.1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alberti ML, Malet Ruiz JM, Fernández ME, et al. Comparative survival analysis between idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Pulmonology 2020; 26: 3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pulmoe.2019.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown KK, Martinez FJ, Walsh SLF, et al. The natural history of progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 2000085. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00085-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moua T, Westerly BD, Dulohery MM, et al. Patients with fibrotic interstitial lung disease hospitalized for acute respiratory worsening: a large cohort analysis. Chest 2016; 149: 1205–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choe J, Chae EJ, Kim YJ, et al. Serial changes of CT findings in patients with chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis: imaging trajectories and predictors of fibrotic progression and acute exacerbation. Eur Radiol 2021; 31: 3993–4003. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-07469-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suzuki A, Kondoh Y, Brown KK, et al. Acute exacerbations of fibrotic interstitial lung diseases. Respirology 2020; 25: 525–534. doi: 10.1111/resp.13682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lima MS, Coletta EN, Ferreira RG, et al. Subacute and chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis: histopathological patterns and survival. Respir Med 2009; 103: 508–515. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fernández Pérez ER, Sprunger DB, Ratanawatkul P, et al. Increasing hypersensitivity pneumonitis-related mortality in the United States from 1988 to 2016. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 199: 1284–1287. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201807-1258LE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Sadeleer LJ, Hermans F, De Dycker E, et al. Impact of BAL lymphocytosis and presence of honeycombing on corticosteroid treatment effect in fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis: a retrospective cohort study. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 1901983. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01983-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang P, Jones KD, Urisman A, et al. Pathologic findings and prognosis in a large prospective cohort of chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Chest 2017; 152: 502–509. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walsh SL, Sverzellati N, Devaraj A, et al. Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis: high resolution computed tomography patterns and pulmonary function indices as prognostic determinants. Eur Radiol 2012; 22: 1672–1679. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2427-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacob J, Bartholmai BJ, Rajagopalan S, et al. Automated computer-based CT stratification as a predictor of outcome in hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Eur Radiol 2017; 27: 3635–3646. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4697-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adegunsoye A, Oldham JM, Bellam SK, et al. Computed tomography honeycombing identifies a progressive fibrotic phenotype with increased mortality across diverse interstitial lung diseases. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2019; 16: 580–588. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201807-443OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chung JH, Zhan X, Cao M, et al. Presence of air trapping and mosaic attenuation on chest computed tomography predicts survival in chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2017; 14: 1533–1538. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201701-035OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gimenez A, Storrer K, Kuranishi L, et al. Change in FVC and survival in chronic fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Thorax 2018; 73: 391–392. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Solomon JJ, Chung JH, Cosgrove GP, et al. Predictors of mortality in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Eur Respir J 2016; 47: 588–596. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00357-2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goh NS, Hoyles RK, Denton CP, et al. Short-term pulmonary function trends are predictive of mortality in interstitial lung disease associated with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017; 69: 1670–1678. doi: 10.1002/art.40130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Doubková M, Švancara J, Svoboda M, et al. EMPIRE Registry, Czech part: impact of demographics, pulmonary function and HRCT on survival and clinical course in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Clin Respir J 2018; 12: 1526–1535. doi: 10.1111/crj.12700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Faverio P, Piluso M, De Giacomi F, et al. Progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: prevalence and characterization in two Italian referral centers. Respiration 2020; 99: 838–845. doi: 10.1159/000509556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mönkäre S, Haahtela T. Farmer's lung: a 5-year follow-up of eighty-six patients. Clin Allergy 1987; 17: 143–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1987.tb02332.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kokkarinen JI, Tukiainen HO, Terho EO. Effect of corticosteroid treatment on the recovery of pulmonary function in farmer's lung. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992; 145: 3–5. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wijsenbeek M, Kreuter M, Olson A, et al. Progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: current practice in diagnosis and management. Curr Med Res Opin 2019; 35: 2015–2024. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2019.1647040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Clinical Research Network , Raghu G, Anstrom KJ, et al. Prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine for pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 1968–1977. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morisset J, Johannson KA, Vittinghoff E, et al. Use of mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine for the management of chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Chest 2017; 151: 619–625. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.10.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fiddler CA, Simler N, Thillai M, et al. Use of mycophenolate mofetil and azathioprine for the treatment of chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis – a single-centre experience. Clin Respir J 2019; 13: 791–794. doi: 10.1111/crj.13086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Terras Alexandre A, Martins N, Raimundo S, et al. Impact of azathioprine use in chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis patients. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2020; 60: 101878. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2019.101878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Adegunsoye A, Oldham JM, Fernández Pérez ER, et al. Outcomes of immunosuppressive therapy in chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. ERJ Open Res 2017; 3: 00016-2017. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00016-2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ferreira M, Borie R, Crestani B, et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab in patients with chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis (cHP): a retrospective, multicentric, observational study. Respir Med 2020; 172: 106146. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2020.106146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wells AU, Brown KK, Flaherty KR, et al. What's in a name? That which we call IPF, by any other name would act the same. Eur Respir J 2018; 51: 1800692. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00692-2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wollin L, Distler JHW, Redente EF, et al. Potential of nintedanib in treatment of progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Eur Respir J 2019; 54: 1900161. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00161-2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Flaherty KR, Wells AU, Cottin V, et al. Nintedanib in progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. N Engl J Med 2019; 381: 1718–1727. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cottin V, Richeldi L, Rosas I, et al. Nintedanib and immunomodulatory therapies in progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Respir Res 2021; 22: 84. doi: 10.1186/s12931-021-01668-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Flaherty KR, Wells AU, Cottin V, et al. Nintedanib in progressive interstitial lung diseases: data from the whole INBUILD trial. Eur Respir J 2021; in press [ 10.1183/13993003.04538-2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wells AU, Flaherty KR, Brown KK, et al. Nintedanib in patients with progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases-subgroup analyses by interstitial lung disease diagnosis in the INBUILD trial: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial. Lancet Respir Med 2020; 8: 453–460. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30036-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shibata S, Furusawa H, Inase N. Pirfenidone in chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis: a real-life experience. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2018; 35: 139–142. doi: 10.36141/svdld.v35i2.6170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mateos-Toledo H, Mejía-Ávila M, Rodríguez-Barreto Ó, et al. An open-label study with pirfenidone on chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Arch Bronconeumol 2020; 56: 163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.arbr.2019.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Behr J, Prasse A, Kreuter M, et al. Pirfenidone in patients with progressive fibrotic interstitial lung diseases other than idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (RELIEF): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2b trial. Lancet Respir Med 2021; 9: 476–486. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30554-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jacobs SS, Krishnan JA, Lederer DJ, et al. Home oxygen therapy for adults with chronic lung disease. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020; 202: e121–e141. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202009-3608ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Holland AE, Dowman LM, Hill CJ. Principles of rehabilitation and reactivation: interstitial lung disease, sarcoidosis and rheumatoid disease with respiratory involvement. Respiration 2015; 89: 89–99. doi: 10.1159/000370126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wijsenbeek MS, Holland AE, Swigris JJ, et al. Comprehensive supportive care for patients with fibrosing interstitial lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 200: 152–159. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201903-0614PP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fisher JH, Kolb M, Algamdi M, et al. Baseline characteristics and comorbidities in the CAnadian REgistry for Pulmonary Fibrosis. BMC Pulm Med 2019; 19: 223. doi: 10.1186/s12890-019-0986-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kern RM, Singer JP, Koth L, et al. Lung transplantation for hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Chest 2015; 147: 1558–1565. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-1543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Leard LE, Holm AM, Valapour M, et al. A consensus document for the selection of lung transplant candidates: an update from the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2021; 40: 1349–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2021.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]