Abstract

Background

A population health approach to depression screening using patient portals may be a promising strategy to proactively engage and identify patients with depression.

Objective

To determine whether a population health approach to depression screening is more effective than screening during clinic appointments alone for identifying patients with depression.

Design

A pragmatic clinical trial at an adult outpatient internal medicine clinic at an urban, academic, tertiary care center.

Patients

Eligible patients (n = 2713) were adults due for depression screening with active portal accounts. Patients with documented depression or bipolar disorder and those who had been screened in the year prior to the study were excluded.

Intervention

Patients were randomly assigned to usual (n = 1372) or population healthcare (n = 1341). For usual care, patients were screened by medical assistants during clinic appointments. Population healthcare patients were sent letters through the portal inviting them to fill out an online screener regardless of whether they had a scheduled appointment. The same screening tool, the Computerized Adaptive Test for Mental Health (CAT-MH™), was used for clinic- and portal-based screening.

Main Measures

The primary outcome was the depression screening rate.

Key Results

The depression screening rate in the population healthcare arm was higher than that in the usual care arm (43% (n = 578) vs. 33% (n = 459), p < 0.0001). The rate of positive screens was also higher in the population healthcare arm compared to that in the usual care (10% (n = 58) vs. 4% (n = 17), p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Findings suggest depression screening via a portal as part of a population health approach can increase screening and case identification, compared to usual care.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03832283

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-022-07779-9.

KEY WORDS: population health, depression, screening, primary care, mental health

INTRODUCTION

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is prevalent, and case identification is crucial to initiate treatment. However, depression goes undetected in about half of symptomatic patients when systematic screening is not in place.1–4 In the USA, there is variability in reported screening rates. Rates from electronic record data (EHR) report less than 5% of patients are screened during routine primary care appointments5,6; however, population-based surveys report about 50% of patients are screened.7

Current strategies for depression screening rely on patients attending appointments. For example, depression screening and remission quality measures require symptom measurement to be performed at appointments.8 However, reliance on appointments for assessing symptoms may be flawed. Most importantly, patients with depression are less likely to attend appointments9–12 and, therefore, may never be screened. Furthermore, the number of clinical tasks addressed during primary care appointments is high, so it could be challenging to perform screening with high fidelity.13–15

A population health strategy to conduct depression screening in patients regardless of whether or not they have scheduled appointments could increase screening rates and case identification. A few studies have used patient portals to administer pre-visit screening,16–18 but none have evaluated screening patients as a population health strategy, i.e., without regard to scheduled appointments. Our study was designed to determine if a population health approach to depression screening using a patient portal (in addition to screening during appointments) increased depression case identification and treatment engagement compared to screening during appointments alone.

METHODS

Study Design

The Patient Outcomes Reporting for Timely Assessment of Life with Depression (PORTAL-Depression) study (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03832283) is a 30-month quality improvement project which integrated a computerized adaptive test (CAT) into the EHR to facilitate the administration of depression assessments. The study consisted of two components: (1) implementation phase and (2) conducting two pragmatic trials for depression screening and measurement. Implementation efforts and measurement trial results were reported separately.19–22 In the screening trial, patients due for screening were randomized with 1:1 blinded allocation to screening during routine appointments (usual care, UC) or to UC plus screening via portal (population health, PH) by a statistician. Randomization was stratified by primary care provider (PCP) type (attending vs. resident). A 12-month trial was planned, but due to the COVID-19 pandemic and temporary halt of appointments, we ended the trial at 10 months. Since depression screening is a standard component of routine care, the University of Chicago Biological Sciences Division, Institutional Review Board declined to review, and an institutional quality improvement determination was obtained under common rule (45 CFR part 46). PCPs were allowed to opt out before randomization. The Extension Consort for a Pragmatic Trial reporting checklist is found in Appendix 1.23

Setting and Patients

The PORTAL-Depression screening trial was conducted at an adult internal medicine clinic. At the time of the trial (May 2019), the practice was staffed by 35 internal medicine and medicine-pediatrics attending physicians, 97 internal medicine and 16 internal medicine-pediatric resident physicians, 5 registered nurses, 6 licensed practical nurses, 9 medical assistants (MA), and 1 medical social worker (SW). The clinic had an integrated behavioral medicine clinic, modeled after the Primary Care Behavioral Health Model,24 which included 2 health psychologists and 3.5 psychology trainees. The clinic had resources to assist in management including referral and clinical decision support resources.25–29

Prior to the intervention, the clinic had three Epic health maintenance topics with corresponding best practice advisories (BPA) to remind the healthcare team to assess depression symptoms: annual screening for patients with no history of depression or Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9 scores ≥ 10, annual surveillance for patients with a history of depression or a PHQ-9 ≥ 10, and monthly monitoring for patients who had a PHQ-9 ≥ 10 until they reached a score less than 5. Patients with diagnoses of bipolar, personality disorder, cognitive impairment, or developmental delay were excluded from the health maintenance topics. Depression screening was performed using the PHQ-2, which reflexed to the PHQ-9 if PHQ-2 scores were 3 or higher.28,30 MAs completed screening during visit triage for about 55% of patients. Three months prior to the trial (February 2019), the clinic switched from the PHQ-2 to the adaptive depression assessments in the Computerized Adaptive Test for Mental Health (CAT-MH™),31 because we had demonstrated it was more sensitive than the PHQ-2 for our population.30 The machine-learning-based diagnostic test (CAD-MDD) reflexes into a dimensional severity assessment tool (CAT-DI) in patients that screen positive for depression.30,32–34

For the trial, eligible patients were adults (≥ 18 years old) who were attributed to the clinic, defined by having an appointment within the past 26 months (age 18–64) or 14 months (age ≥ 65). Eligible patients had to have an active portal account and be due for annual screening (not surveillance or monitoring). Patients whose PCPs had opted out of the study (n = 3) or were hospital employees (due to institutional policy) were excluded.

Intervention

Population Health (PH) Arm (Appendix Figure 1, Appendix 1)

Patients received email notifications to log in to their portal account and complete an online depression screener. Invitations were sent regardless of whether patients had a scheduled appointment. Invitations were sent every 4 to 8 weeks until screening was complete or a maximum of six invitations had been sent. Invitations were sent on different days and times of the week. Results completed via the portal were stored in the medical record. Positive results were automatically sent to the PCP’s electronic inbasket. In case PCPs missed positive results, a physician (NL) reviewed cases of patients who had moderate-to-severe portal-based screening results. If patients did not have an appointment discussing their mental health in the last 30 days or in the next 30 days, results were forwarded to the clinic social worker, copying the PCP. The social worker reached out to patients to assess for safety and provide care linkage. Patients could also be screened during appointments.

Usual Care (UC) Arm (Appendix Figure 1, Appendix 1)

For UC, the MA would place a clinical order to launch the online assessment on the desktop computer. The assessment could read the questions aloud and patients could either take hold of the mouse or tell the MA their responses. Once screening was complete, results were saved in the medical record; if results were positive, PCPs received results as a critical non-interruptive BPA and an inbasket message. A paper PHQ-2/9 questionnaire was available for patients who were triaged in non-private areas.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients screened for depression, defined by either a completed CAD-MDD or responses to both PHQ-2 questions. Secondary outcomes included screening results, care processes, healthcare utilization, and safety outcomes. The percentage of positive screens (positive CAD-MDD or PHQ-2 ≥ 3 (or PHQ-9 ≥ 10, if available)) and patients with moderate-to-severe depression symptoms (CAT-DI ≥ 50 or PHQ-9 ≥ 10) were calculated by arm. For the PH arm, process measures included patient engagement with email notifications and assessments. For the UC arm, process measures were the percentage of patients with a visit who were screened. Healthcare utilization outcomes included the percentage with primary care visits, referrals to psychiatry or psychology services, telephone encounters, portal messages, emergency department (ER) visits, and hospitalizations during the study. The safety outcome was the percentage of patients in the PH arm with moderate-to-severe symptoms who received follow-up by the PCP team within 3 business days.

Analysis

An intention-to-treat approach was used. Quantitative outcomes were summarized using descriptive statistics. With more than 1300 patients per arm, the study had at least 80% power to detect a difference of 10% in the proportion of screening between arms. For primary and secondary analyses, a chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test and logistic regression were used to compare screening rates and other binary or categorical outcomes. For continuous outcomes, a two-sample t test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test and linear regression were utilized for comparisons. We conducted subpopulation analyses by age group, sex, race/ethnicity, and PCP type. A two-sided significance level of 0.05 was used and unadjusted results are reported. Analyses were performed in R 4.0.2.

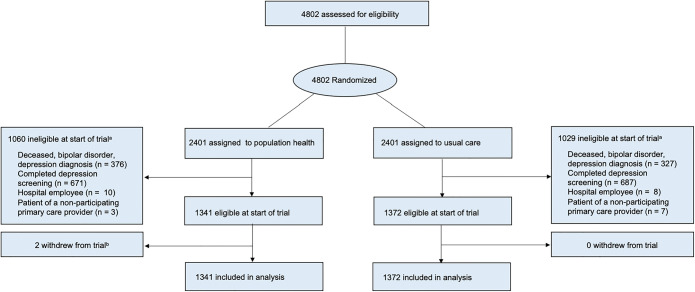

RESULTS

A total of 2713 patients were eligible (PH: n = 1341; UC: n = 1372). The number of patients differed by arm due to a 4-month delay between randomizing the list of eligible patients and trial launch, during which time patients became ineligible (e.g., death, new diagnosis of depression or bipolar, received screening) (Fig. 1). Six percent (58/1037) of the patients completed the PHQ (PH: n = 31; UC: n = 27; p = 0.63). Mean age was 55 (SD = 17), 58% (n = 1571) were female, and 47% (n = 1274) were African-American (Table 1). There was no difference in time since the most recent portal login at trial onset (PH: mean, 43 days (SD = 16); UC: 42 days (SD = 17), p = 0.29). At baseline, nearly all patients had been screened for depression at least once previously. There were no statistically significant differences between arms.

Figure 1.

PORTAL-Depression screening trial patient flow diagram. aPatients become ineligible before the start of the trial due to a 4-month delay in study launch. bPatients requested to be removed from the trial and not receive the screening invitation.

Table 1.

PORTAL-Depression Screening Trial Patient Characteristics at Baseline

| Characteristics | Overall (n = 2713) |

Population health (n = 1341) |

Usual care (n = 1372) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 55 (17) | 55 (17) | 54 (17) | 0.21 |

| Female, n (%) | 1571 (58) | 790 (59) | 781 (57) | 0.29 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.44 | |||

| Hispanic | 130 (5) | 60 (4) | 70 (5) | |

| Not Hispanic | 2511 (93) | 1241 (93) | 1270 (93) | |

| Unknown | 72 (3) | 40 (3) | 32 (2) | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.92 | |||

| Asian | 207 (8) | 101 (8) | 106 (8) | |

| African-American | 1274 (47) | 640 (48) | 634 (46) | |

| White | 1098 (40) | 532 (40) | 566 (41) | |

| Other/unknown | 134 (5) | 68 (5) | 66 (5) | |

| Insurance, n (%) | 0.76 | |||

| Medicaid, Medicare, Medicaid-Medicare, Veterans Affairs, Tricare | 842 (31) | 404 (30) | 438 (32) | |

| Private | 1854 (68) | 928 (69) | 926 (67) | |

| Other/unknown | 17 (1) | 9 (1) | 8 (1) | |

| Primary care provider, n (%) | 0.41 | |||

| Attending | 1824 (67) | 891 (66) | 933 (68) | |

| Resident | 889 (33) | 450 (34) | 439 (32) | |

| Most recent patient portal login (days), mean (SD) | 43 (17) | 43 (16) | 42 (17) | 0.29 |

| History of depression screening, n (%) | 2687 (99) | 1327 (99) | 1360 (99) | 0.80 |

Primary Outcome

Screening Rate

Overall, 38% (n = 1037) of patients were screened. More patients were screened in PH than in UC (43% (n = 578) vs. 33% (n = 459), p < 0.0001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

PORTAL-Depression Screening Results by Study Arm

| Population health (n = 1341) |

Usual care (n = 1372) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Screened for depression during trial, n (%) | 578 (43)* | 459 (33)* |

| Negative | 520 (90)* | 442 (96)* |

| Positive | 58 (10)* | 17 (4)* |

| Moderate to severe symptoms | 46 (8) | 13 (3) |

*p value < 0.001

Subpopulation Analyses

Most patient groups were more likely to be screened in PH than in UC (Table 3). There were no statistically significant differences between arms for patients aged 65 and older, African-American patients, Asian patients, and patients with public insurance.

Table 3.

Unadjusted Odds Ratio for PORTAL-Depression Screening Completion Versus Usual Clinic-Based Depression Screening Completion by Patient Characteristics

| Patient characteristics | Usual care (n = 459/1372) | Population health (n = 578/1341) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%)* | n (%)* | OR (95% Cl)† | |

| Age, y | |||

| 18–24 | 6/54 (11) | 20/55 (36) | 4.44 (1.68–13.43)§ |

| 25–34 | 16/139 (12) | 35/150 (23) | 2.32 (1.23–4.54)§ |

| 35–44 | 46/187 (25) | 76/189 (40) | 2.06 (1.32–3.22)‡ |

| 45–54 | 77/265 (29) | 105/239 (44) | 1.91 (1.32–2.77)‡ |

| 55–64 | 109/283 (39) | 143/297 (48) | 1.48 (1.06–2.06)‖ |

| 65+ | 205/444 (46) | 199/411 (48) | 1.09 (0.84–1.43) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 272/781 (35) | 348/790 (44) | 1.47 (1.20–1.81)‡ |

| Male | 187/591 (32) | 230/551 (42) | 1.55 (1.21–1.97)‡ |

| Race | |||

| Asian | 27/106 (25) | 38/101 (38) | 1.76 (0.97–3.21) |

| African American | 242/634 (38) | 276/640 (43) | 1.23 (0.98–1.54) |

| White | 174/566 (31) | 241/532 (45) | 1.86 (1.46–2.39)‡ |

| Other/unknown | 16/66 (24) | 23/68 (34) | 1.59 (0.75–3.44)‡ |

| Insurance | |||

| Medicaid, Medicare, Medicaid-Medicare, Veterans Affairs, Tricare | 193/438 (44) | 189/404 (47) | 1.12 (0.85–1.46) |

| Private | 265/926 (29) | 385/928 (41) | 1.77 (1.46–2.15)‡ |

| Other/unknown | 1/8 (13) | 4/9 (44) | 4.72 (0.47–156.53) |

| Primary care provider type | |||

| Resident | 119/439 (27) | 171/450 (38) | 1.65 (1.24–2.19)‡ |

| Attending | 340/933 (36) | 407/891 (46) | 1.47 (1.22–1.77)‡ |

| # of appointments in the prior year | |||

| None | 86/447 (19) | 121/414 (29) | 1.73 (1.26–2.38)‡ |

| ≥1 | 373/925 (40) | 457/927 (49) | 1.44 (1.20–1.73)‡ |

*Row percentages indicating the number of patients screened in the population health arm over the total number of population healthcare arm patients that were eligible to undergo screening

†The usual-care arm is the reference group

‡p value < 0.001

§p value < 0.01

‖p value < 0.05

Secondary Outcomes

Screening Results

Overall, 7% (n = 75/1037) of the screened population met criteria for depression and 6% (n = 59/1037) had moderate-to-severe symptoms. The PH arm had a higher rate of positive screens than the UC arm (10% (n = 58) vs. 4% (n = 17)) (Table 2). Within the PH arm, 58% (n = 333) of the patients were screened in clinic and 42% (n = 245) were screened via the portal. Patients who filled out the screener via the portal had a higher rate of positive screens than those who filled out the screener in clinic (16% (n = 40) vs. 4% (n = 17)).

Process Measures

Among patients in the PH arm (n = 1341), 1245 patients were sent an email invitation via the portal; some patients did not receive letters because they no longer met inclusion criteria by the time the invitations were sent. About 89% (n = 1102) of the patients who were emailed logged into their portal account and 67% (n = 830) logged into their account and opened the message. If the message was opened, 30% (n = 248) of the patients started the assessment, and then nearly all patients (n = 245) completed the assessment. Among patients who completed screening via the portal, 55% (n = 135) responded after the first invitation, 30% (n = 73) responded after the second invitation, and 15% (n = 37) responded after the third invitation. The patients completed screening a median of 2 days (IQR, 1–4) after receiving an invitation. The day and time when invitations were sent did not affect the response rate. In the UC arm, over half of the patients (57%, n = 778/1372) had a PCP visit, and over half of these patients (59%, n = 459) were screened.

Healthcare Utilization and Safety

Nearly one-quarter of patients in the PH arm (24%, n = 297) scheduled a PCP visit within 2 weeks of receiving a message, regardless if they completed the screener. Patients in the PH arm had a higher rate of telephone encounters (48% (n = 638) vs. 44% (n = 599), p = 0.04) and referrals to psychiatry/psychology (4% (n = 58) vs. 3% (n = 35), p = 0.01). There were no differences in the percentage of portal messages, primary care visits, ER visits, or hospitalizations between arms (Table 4).

Table 4.

PORTAL-Depression Trial Healthcare Utilization During 10-Month Follow-Up by Study Arm

| Population health (n = 1341) n (%) |

Usual care (n = 1372) n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Telephone encounter | 638 (48)‡ | 599 (44)‡ |

| Referrals to psychiatry/psychology | 58 (4)† | 35 (3)† |

| Portal message* | 1092 (81) | 1110 (81) |

| Primary care visit | 816 (61) | 815 (59) |

| Emergency department visit | 162 (12) | 180 (13) |

| Hospitalizations | 90 (7) | 111 (8) |

*Patient portal messages did not include the screening invitations

†p value = 0.01

‡p value < 0.05

Among patients who had moderate-to-severe depression screening results via the portal, 94% (29/31) received follow-up, which included any of the following scenarios: (1) contact by social worker after a positive result; (2) contact by PCP within 1 month after positive result; and (3) contact by psychiatrist within 1 month after positive result. A contact included any telephone encounters, appointment, outreach via the portal, or psychiatric medication refills.

Subpopulation Analyses

In the PH arm, there were differences by race in completion vs. non-completion of screening via the portal (Appendix Table 2 in Appendix 1). Asians (OR 0.55 (95% Cl 0.29–0.98)) and African-Americans (OR 0.64; 95% Cl 0.47–0.85) were less likely to complete the portal-based screener than whites. There were no significant differences by age, sex, ethnicity, insurance, and PCP type. However, when completing the portal-based screener, moderate-to-severe symptoms were more prevalent among African-Americans (vs. whites) (OR 2.85 (95% Cl 1.25–6.97)) (Appendix Table 3 in Appendix 1). Additionally, moderate-to-severe symptoms were more prevalent among patients with age 18–24 (OR 13.47; 95% Cl 3.13–65.53) and 35–44 years (OR 3.52; 95% Cl 1.02–13.19), compared to patients 65 years or older among those who completed the portal-based screener. Patients with attending (vs. resident) PCPs were less likely to have moderate-to-severe symptoms (OR 0.19 (95% CI 0.08–0.42)) among those who completed the portal-based screener.

DISCUSSION

Our study showed that a population-level approach to depression screening using a portal increased screening and identified more patients with MDD symptoms, compared to screening patients only at clinic appointments. A portal-based, population health approach increased screening rates overall and among groups who are typically less engaged in care, including younger patients, males, and those who had not attended an appointment in the last year.

Our population health approach with portal-based depression screening was an effective strategy to improve screening rates in primary care. Our results indicate that people with moderate-to-severe depression may be more willing to engage with the healthcare system via the portal rather than by attending clinic visits. Therefore, shifting the time spent on screening to outside of appointments could save valuable time during appointments for managing active health issues, as well as identifying significantly more patients with depression, which is the key first step to improving depression outcomes. Allowing for more timely recognition of incident depression has the potential to accelerate the time to remission.

While findings are promising, the likelihood of their dissemination more widely into practice is hampered by key problems with how the healthcare system is incentivized to screen and manage depression. In 2022, quality measures from health insurers require depression symptoms to be measured in patients during appointments or 14 days before appointments.35–37 Because of these parameters, healthcare systems are incentivized to only measure depression symptoms in patients with scheduled appointments. Potential improvements to current quality measures would allow PCPs with established patient panels to receive credit for all negative screens, and for positive screens that had appropriate follow-up and care plan documented, regardless of appointments. For patient-centered care, it would be important that appropriate follow-up for positive screens could be done using a strategy appropriate for that patient (e.g., phone calls, video visits, portal communications).

Another important factor hindering dissemination is the healthcare system’s limited capacity to address patients with incident depression, and debate on depression screening’s utility in improving mental health outcomes.38 In the USA, there is a mental healthcare shortage.39–42 This shortage is exacerbated by greater barriers to reimbursement compared to other specialties.39–42 As a result, PCPs are the de facto source of mental healthcare, caring for 75% of mental health problems.43–46 However, several studies have found PCPs do not feel equipped to manage mental health problems.46–50 Even among our clinic of engaged PCPs,26 some clinicians reported that responding to positive portal-based results was burdensome. Promising solutions exist, including the evidence-based Collaborative Care Model, which provides care management and consultative psychiatric services to PCPs.51–53 Patient-centered care leveraging integrated behavioral health models would expand the health system’s capacity to address patients identified with depression and expand primary care’s ability to manage mental health problems. Further, prior problems with low screen detection may have been related to the screening mode and not the utility of screening itself. Our study suggests that inviting patients who have depression symptoms to report their symptoms via a portal may indeed increase case identification, which is important to improving depression outcomes.

We found screening rates were improved with the PH approach compared to UC for most demographic groups. One important consideration for our findings was that response rates to the portal-based screening varied by race. Interestingly, among African-Americans who had lower response rates to the portal-based screening, there were higher rates of moderate-to-severe depression. Similarly, patients aged 18–24 years had high rates of moderate-to-severe depression, and this population is often less engaged with the healthcare system. Overall, these results suggest that patients with incident depression may be more responsive to population health, portal-based screening compared to visit-based screening. Increasing response rates by additional tailoring or outreach paired with a population health strategy could be an important adjunct to usual in-clinic screening.

There were several limitations. This was a single-center study conducted at an urban academic teaching clinic with a large African-American population. At baseline, about 60% of the patients (aged ≥ 18 years old) were enrolled in the portal, which was significantly more than the 25% reported by healthcare organizations prior to the COVID-19 pandemic,54 and similar to national 2020 rates.55 Therefore, results may not be generalizable to settings with low portal engagement. Strong clinician buy-in and availability of integrated behavioral healthcare services within the clinic made it feasible to implement the intervention,25,28 which may not be reproducible in other settings. Further, the switch of the screening tool shortly before study launch may have a confounding effect on the UC arm screening rate. Our analysis did not include key measures for depression care and management (e.g. depression diagnosis confirmation, other long-term mental health outcomes), so inferences on these outcomes cannot be made. Finally, because of our study design, we were not able to ascertain whether higher screening rates were due to the online modality of measurement vs. another mode (e.g., telephone).

CONCLUSION

We found a population health approach to depression screening led to a higher screening rate and 2.5-fold increase in identification of moderate-to-severe depression compared to visit-based screening. This evidence suggests incorporating population health approaches with quality measure recommendations may improve depression case identification in primary care. Future directions include testing this strategy in other primary care settings with high prevalence of depression.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 262 kb)

Acknowledgements

Contributors: We gratefully acknowledge Daviel Thomas, LCSW, who reached out to patients who screened positive for depression via the portal and connected them to healthcare services.

Author Contribution

M.F. is the guarantor of this work and had access to the data, contributed to the design, analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. N.L. had access to the data, designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, critically reviewed/edited the manuscript, and obtained funding for the study. E.S. and M.Z. had access to the data, contributed to the design, analyzed and interpreted the data, and critically reviewed/edited the manuscript. A.K., D.Y., L.V., N.B., R.G, S.S., and W.W. contributed to the design and critically reviewed/edited the manuscript.

Funding

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U18 HS26151

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Robert Gibbons, PhD, developed the CAT-MH™ which was used as the depression screener in the study. Dr. Gibbons received no funding from the grant. The grant paid for the depression screener tool directly to the company. Dr. Gibbons receives no funds from the company. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed and approved by the University of Chicago in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rush AJ. Isn’t it about time to employ measurement-based care in practice? Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(10):934-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Simon GE, VonKorff M. Recognition, management, and outcomes of depression in primary care. Arch Fam Med. 1995;4(2):99-105. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Mitchell AJ, Vaze A, Rao S. Clinical diagnosis of depression in primary care: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;374(9690):609-19. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Pfoh ER, Janmey I, Anand A, Martinez KA, Katzan I, Rothberg MB. The impact of systematic depression screening in primary care on depression identification and treatment in a large health care system: a cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(11):3141-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Baumann LC, Davidson KW, Ebell M, et al. Screening for depression in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315(4):380-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Akincigil A, Matthews EB. National rates and patterns of depression screening in primary care: results from 2012 and 2013. Psychiatric Services. 2017;68(7):660-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Kato E, Borsky AE, Zuvekas SH, Soni A, Ngo-Metzger Q. Missed opportunities for depression screening and treatment in the United States. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(3):389-97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: final coverage decision memorandum for screening for depression in adults. Accessed March 24, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=251

- 9.Moscrop A, Siskind D, Stevens R. Mental health of young adult patients who do not attend appointments in primary care: a retrospective cohort study. Fam Pract. 2012;29(1):24-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Mitchell AJ, Selmes T. Why don’t patients attend their appointments? Maintaining engagement with psychiatric services. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2007;13(6):423-34. 10.1192/apt.bp.106.003202

- 11.Ciechanowski P, Russo J, Katon W, Simon G, Ludman E, Von Korff M, et al. Where is the patient? The association of psychosocial factors and missed primary care appointments in patients with diabetes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(1):9-17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Cashman SB, Savageau JA, Lemay CA, Ferguson W. Patient health status and appointment keeping in an urban community health center. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2004;15(3):474-88. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Linzer M, Bitton A, Tu SP, Plews-Ogan M, Horowitz KR, Schwartz MD, et al. The end of the 15-20 minute primary care visit. J Gen Intern Med; 2015:1584-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Tai-Seale M, McGuire T. Time is up: increasing shadow price of time in primary-care office visits. Health Econ. 2012;21(4):457-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Baron RJ. What’s keeping us so busy in primary care? A snapshot from one practice. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(17):1632-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Leveille SG, Huang A, Tsai SB, Weingart SN, Iezzoni LI. Screening for chronic conditions using a patient internet portal: recruitment for an internet-based primary care intervention. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(4):472-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Wagner LI, Schink J, Bass M, Patel S, Diaz MV, Rothrock N, et al. Bringing PROMIS to practice: brief and precise symptom screening in ambulatory cancer care. Cancer. 2015;121(6):927-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Sorondo B, Allen A, Bayleran J, Doore S, Fathima S, Sabbagh I, et al. Using a patient portal to transmit patient reported health information into the electronic record: workflow implications and user experience. EGEMS (Wash DC). 2016;4(3):1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Laiteerapong N. Patient outcomes reporting for timely assessments of life with depression: PORTAL-Depression. Oral presentation at AcademyHealth, 2019. Washington, D.C.

- 20.Franco EM, Moses J, Deehan W, DeGarmo A, Montgomery ET, Wan W, Shah SS, Volnchenboum S, Gibbons R, Yohanna D, Liebovitz D, Beckman N, Vinci L, Laiteerapong N. Implementation of patient outcomes reporting in the electronic health record for timely assessment of life with depression: PORTAL-Depression. Oral presentation at the Society of General Internal Medicine Midwest Regional Meeting, 2019. Minneapolis, MN.

- 21.Staab EM, Franco M, Zhu M, Laiteerapong N. Patient portal-based depression surveillance and monitoring during COVID-19. Poster presented at AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting, 2021. Virtual.

- 22.Staab EM, Franco M, Zhu M, Wan W, Deehan W, Moses J, et al. Population health approach to depression symptom monitoring in primary care using a patient portal: a randomized controlled trial. Oral presentation at the Society of General Internal Medicine Midwest Regional Meeting, 2021. Virtual.

- 23.Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, Altman DG, Tunis S, Haynes B, et al. Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. BMJ. 2008;337:a2390. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reiter JT, Dobmeyer AC, Hunter CL. The Primary Care Behavioral Health (PCBH) Model: an overview and operational definition. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2018;25(2):109-26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Staab EM, Terras M, Dave P, Beckman N, Shah S, Vinci LM, et al. Measuring perceived level of integration during the process of primary care behavioral health implementation. Am J Med Qual. 2018;33(3):253-61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Yin I, Staab EM, Beckman N, Vinci LM, Ari M, Araújo FS, et al. Improving primary care behavioral health integration in an academic internal medicine practice: 2-Year follow-up. Am J Med Qual. 2021;36(6):379-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Primary Care - Behavioral Health Integration Program. Accessed March 9, 2021, 2021. https://voices.uchicago.edu/behavioralhealthintegrationprogram/about/

- 28.Yin I, Wan W, Staab EM, Vinci L, Laiteerapong N. Use of report cards to increase primary care physician depression screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Gorman DC, Ham SA, Staab EM, Vinci LM, Laiteerapong N. Medical assistant protocol improves disparities in depression screening rates. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61(5):692-700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Graham AK, Minc A, Staab E, Beiser DG, Gibbons RD, Laiteerapong N. Validation of the computerized adaptive test for mental health in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(1):23-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Adaptive testing technologies. Accessed March 25, 2021. https://adaptivetestingtechnologies.com/cat-mh/

- 32.Gibbons RD, Weiss DJ, Kupfer DJ, Frank E, Fagiolini A, Grochocinski VJ, et al. Using computerized adaptive testing to reduce the burden of mental health assessment. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(4):361-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Gibbons RD, Weiss DJ, Pilkonis PA, Frank E, Moore T, Kim JB, et al. Development of a computerized adaptive test for depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(11):1104-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Gibbons RD, Hooker G, Finkelman MD, Weiss DJ, Pilkonis PA, Frank E, et al. The computerized adaptive diagnostic test for major depressive disorder (CAD-MDD): a screening tool for depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(7):669-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.2021 MIPS Measure #134: Preventive care and screening: screening for depression and follow-up plan. Accessed June 9, 2021. https://healthmonix.com/mips_quality_measure/2021-mips-measure-134-preventive-care-and-screening-screening-for-depression-and-follow-up-plan/

- 36.Depression Screening and Follow-up for Adolescents and Adults (DSF). Accessed on June 7 2022. https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/depression-screening-and-follow-up-for-adolescents-and-adults/

- 37.Preventive care and screening: screening for depression and follow-up plan. Accessed on June 11 2022. https://ecqi.healthit.gov/ecqm/ec/2021/cms002v10

- 38.Thombs BD, Markham S, Rice DB, Ziegelstein RC. Does depression screening in primary care improve mental health outcomes? BMJ. 2021;374:n1661. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Health Resources and Services Administration/National Center for Health Workforce Analysis, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration/Office of Policy Planning and Innovation. National Projections of Supply and Demand for Selected Behavioral Health Practitioners: 2013-2025. 2015.

- 40.Olfson M. Building the mental health workforce capacity needed to treat adults with serious mental illnesses. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(6):983-90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.National Council for Mental Wellbeing. The psychiatric shortage: causes and solutions. 2018. https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Revised-Final-Access-Paper.pdf. Accessed on June 11, 2022.

- 42.Goldman W. Economic grand rounds: Is there a shortage of psychiatrists? Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(12):1587-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Kessler R, Stafford D. Chapter 2. Primary care is the de facto mental health system. In: Kessler R, Stafford D, eds. Collaborative medicine case studies: evidence in practice. New York, NY: Springs; 2008.

- 44.Norquist GS, Regier DA. The epidemiology of psychiatric disorders and the de facto mental health care system. Annu Rev Med. 1996;47:473-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Abed Faghri NM, Boisvert CM, Faghri S. Understanding the expanding role of primary care physicians (PCPs) to primary psychiatric care physicians (PPCPs): enhancing the assessment and treatment of psychiatric conditions. Ment Health Fam Med. 2010;7(1):17-25. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Loeb DF, Bayliss EA, Binswanger IA, Candrian C, deGruy FV. Primary care physician perceptions on caring for complex patients with medical and mental illness. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(8):945-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Colon-Gonzalez MC, McCall-Hosenfeld JS, Weisman CS, Hillemeier MM, Perry AN, Chuang CH. “Someone’s got to do it” - primary care providers (PCPs) describe caring for rural women with mental health problems. Ment Health Fam Med. 2013;10(4):191-202. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Oud MJ, Schuling J, Slooff CJ, Meyboom-de Jong B. How do general practitioners experience providing care for their psychotic patients? BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Ballester DA, Filippon AP, Braga C, Andreoli SB. The general practitioner and mental health problems: challenges and strategies for medical education. Sao Paulo Med J. 2005;123(2):72-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Johansen IH, Carlsen B, Hunskaar S. Psychiatry out-of-hours: a focus group study of GPs' experiences in Norwegian casualty clinics. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Serrano N, Monden K. The effect of behavioral health consultation on the care of depression by primary care clinicians. Wmj. 2011;110(3):113-8. [PubMed]

- 52.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW, Jr., Hunkeler E, Harpole L, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2836-45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Finley PR, Rens HR, Pont JT, Gess SL, Louie C, Bull SA, et al. Impact of a collaborative care model on depression in a primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(9):1175-85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Henry J, Barker W, Kachay L. Electronic capabilities for patient engagement among U.S. non-federal acute care hospitals: 2013-2017. In: Information Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, eds. Washington DC; April 2019.

- 55.Johnson C, Richwine C, Patel V. Individuals’ access and use of patient portals and smartphone health apps, 2020. ONC Data Brief, no.57. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology: Washington DC. 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 262 kb)