Abstract

PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis has been used to generate 38 alanine-substitution mutations in the C-terminal 41 amino acid residues of LuxR. This region plays a critical role in the mechanism of LuxR-dependent transcriptional activation of the Vibrio fischeri lux operon during quorum sensing. The ability of the variant forms of LuxR to activate transcription of the lux operon was examined by using in vivo assays in recombinant Escherichia coli. Eight recombinant strains produced luciferase at levels less than 50% of that of a strain expressing wild-type LuxR. Western immunoblotting analysis verified that the altered forms of LuxR were expressed at levels equivalent to those of the wild type. An in vivo DNA binding-repression assay in recombinant E. coli was subsequently used to measure the ability of the variant forms of LuxR to bind to the lux box, the binding site of LuxR at the lux operon promoter. All eight LuxR variants found to affect cellular luciferase levels were unable to bind to the lux box. An additional 11 constructs that had no effect on cellular luciferase levels were also found to exhibit a defect in DNA binding. None of the alanine substitutions in LuxR affected activation of transcription of the lux operon without also affecting DNA binding. These results support the conclusion that the C-terminal 41 amino acids of LuxR are important for DNA recognition and binding of the lux box rather than positive control of the process of transcription initiation.

Vibrio fischeri, a symbiotic bioluminescent bacterium, serves as one of the best-understood model systems for a mechanism of cell density-dependent bacterial gene regulation known as quorum sensing. During quorum sensing in V. fischeri, the chemical signal, 3-oxohexanoyl homoserine lactone (3-oxo-C6-HSL) is synthesized by the bacteria and used to self-sense population levels in a given environment (for recent reviews, see references 8, 9,1 and 24). As the levels of this autoinducer signal rise, complexes form between it and the N-terminal domain of a 250-amino-acid residue regulatory protein, LuxR. Only when autoinducer has bound to the N-terminal domain of LuxR is the C-terminal domain able to bind to a regulatory region of the lux DNA, known as the lux box, and activate transcription of the luminescence or lux operon (7, 10, 23). The arrangement of the lux genes in V. fischeri is such that the operon (luxICDABEG) containing the luxI autoinducer synthase gene and the other structural genes necessary for luminescence and luxR are divergently transcribed (reviewed in references 9 and 23). The lux box region, thought to be bound by LuxR in the presence of the V. fischeri autoinducer, is centered at −42.5 bp from the transcription start site of luxI (6).

Previous studies with recombinant Escherichia coli have identified amino acid point mutations in the C-terminal domain of LuxR that can be placed into two categories: (i) those that affect the ability of LuxR to activate transcription of the lux operon (residues 184, 193, 195, 197, 217, and 230) (17, 19) and (ii) those that result in a form of LuxR that is capable of autoinducer-independent activation of transcription of the lux operon (residues 164, 221, 223, and 246) (14, 18). Deletion mutagenesis analysis of the C-terminal domain of LuxR was also used to identify regions of LuxR critical for its ability to activate transcription of the lux operon (3, 4). A truncated form of LuxR, containing a deletion of the C-terminal 40 amino acids, was found to be unable to activate transcription of the lux operon but capable of negatively autoregulating LuxR transcription (4). Truncations larger than 40 amino acids resulted in the loss of the autoregulatory phenotype and therefore presumably the ability to bind to the DNA (4, 5). This interpretation was supported by amino acid sequence analysis that identified a helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif within the C-terminal domain of LuxR (11, 12). However, recent studies of the function of the truncated forms of LuxR in an in vivo DNA binding-repression assay have redefined the region of LuxR thought to be involved in DNA binding as opposed to the positive control of lux operon expression. Deletions of the C-terminal domain larger than 10 amino acid residues resulted in the inability to bind to lux box DNA (7). The goal of this study was to further analyze the role of the C-terminal 41 amino acid residues of LuxR in the mechanism of transcriptional activation of the lux operon during quorum sensing.

Alanine-scanning mutagenesis of LuxR.

Thirty-eight alanine-substitution mutations were generated in the C-terminal 41 amino acid residues of LuxR, cloned in the ColE1 replicon pSC300 (3), via PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis procedures. PCR products coding for mutations at amino acid residues 246 to 250 in LuxR were generated in 100-μl reaction mixtures containing a 2 μM concentration of one mutagenic primer (Table 1), 2 μM XBA200 primer (CGTATAATGTGTGGAATTGTGAGCG), 2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), 2.5 U of Taq2000 polymerase and 1× Taq2000 reaction buffer (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), 2 mM MgSO4, and 100 ng of PvuII-linearized pSC300 template. A mutation at residue 215 was also obtained as described above, except PVU200 primer (GAAGTGGTCCTGCAACTTTATCC) was substituted for XBA200 primer. Mutagenesis of the remaining amino acid residues under study was performed by a three-primer method (13). Each of the mutagenic primers (Table 1) was phosphorylated with T4 polynucleotide kinase, and 200 pmol was added to a PCR mixture that contained 2 μM XBA200 primer, 2 μM PVU200 primer, 2 mM dNTPs, 2.5 U of Taq2000 polymerase, 0.7× Taq2000 reaction buffer, 40 U of Taq DNA ligase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.), 2 mM MgSO4, and 100 ng of PvuII-linearized pSC300 template. A Sprint thermal cycler (Hybaid, Middlesex, United Kingdom) was programmed as follows for all reactions: 1 cycle at 94°C for 2 min; 30 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 46°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min; and 1 cycle at 72°C for 10 min.

TABLE 1.

Sequences of mutagenic primers

| Residue of alanine substitution | Mutant primer sequence (5′ to 3′)a | Change in restriction endonuclease recognition site |

|---|---|---|

| 210 | GGCTGTGCTGAGCGTACTGTCACTTTCC | Lose PstI site |

| 211 | GGCTGTAGTGCGCGTACTGTCACTTTCC | Lose PstI site |

| 212 | GGCTGTAGTGAGGCTACTGTCACTTTCC | Lose PstI site |

| 213 | GGCTGTAGTGAGCGTGCTGTCACTTTCC | Lose PstI site |

| 214 | GGCTGTAGTGAGCGTACTGCGACTTTCC | Lose PstI site |

| 215 | TAGGCTGCAGTGAGCGTACTGTCGCTTTCC | No change |

| 216 | GGCTGTAGTGAGCGTACTGTCACTGCGCATTTAACC | Lose PstI site |

| 217 | GGCTGTAGTGAGCGTACTGTCACTTTCGCATTAACC | Lose PstI site |

| 218 | GGCTGTAGTGAGCGTACTGTCACTTTCCATGCAACC | Lose PstI site |

| 219 | TTAGCAAATGCTCAAATGAAAC | Lose FspI site |

| 220 | TTAACCGCAGCGCAAATGAAAC | Lose FspI site |

| 222 | TTAACCAATGCGGCAATGAAAC | Lose FspI site |

| 223 | TTAACCAATGCTCAAGCGAAAC | Lose FspI site |

| 224 | TTAACCAATGCTCAAATGGCACTC | Lose FspI site |

| 225 | GAAAGCAAATACAACAAACCGTTGCC | Lose MspAI site |

| 226 | GAAACTCGCTACAACAAACCGTTGCC | Lose MspAI site |

| 227 | GAAACTCAATGCAACAAACCGTTGCC | Lose MspAI site |

| 228 | CTCAATACAGCAAACCGTTGCC | Lose MspAI site |

| 229 | CTCAATACAACAGCGCGCTGCC | Lose MspAI site |

| 230 | CTCAATACAACAAACGCTTGCC | Lose MspAI site |

| 231 | ACAAACCGCGCACAAAGTATTTC | Lose MspAI site |

| 232 | ACAAACCGTTGCGCAAGTATTTC | Lose MspAI site |

| 233 | ACCGTTGCCAAGCTATTTCTAAAGC | Lose MspAI site |

| 234 | ACAAACCGTTGCCAAAGTGCATCTAAAG | Lose MspAI site |

| 235 | ACAAACCGTTGCCAAAGTATTGCTAAAG | Lose MspAI site |

| 236 | ACCGTTGCCAAAGTATTTCTGCAGCAATTTTAAC | Lose MspAI site |

| 238 | TCTAAAGCAGCTTTAACAGGAGCAATCGATTGCCCATA | Add ClaI site |

| 239 | CAATTGCAACAGGAGCAATCGATTGCCCATAC | Add ClaI site |

| 240 | CAATTTTAGCAGGAGCAATCGATTGCCCATAC | Add ClaI site |

| 241 | CAATTTTAACAGCAGCAATCGATTGCCCATAC | Add ClaI site |

| 243 | TTAACAGGAGCAGCTGATTGCCCATAC | Add PvuII site |

| 244 | CAATTGCTTGCCCATACTTCAAAAATT | Lose DraI site |

| 245 | CAATTGATGCGCCATACTTCAAAAATT | Lose DraI site |

| 246 | TCCCCCGGGCTATTAATTTTTAAAGTATGCGCAATC | No change |

| 247 | TCCCCCGGGCTATTAATTTTTAAAAGCTGGGC | No change |

| 248 | TCCCCCGGGCTATTAATTTTTAGCGTATGG | No change |

| 249 | TCCCCCGGGCTATTAATTTGCAAAGTATGG | No change |

| 250 | TCCCCCGGGCTATTAAGCTTTAAAGTATGG | No change |

Underlined nucleotides are changes made in luxR to code for an alanine residue at the specified residue. Nucleotides in boldface are changes made in luxR to add or delete the indicated restriction endonuclease recognition site.

The PCR products generated for the construction of the alanine substitutions were purified, and then all, except the one for the mutation at residue 215, were sequentially digested with SmaI and XbaI. After electrophoresis of the digested DNA into an 0.8% agarose gel, the appropriate band was extracted and ligated into pSC300, which had been prepared in an identical manner. The cloning of the PCR product containing the mutation at residue 215 into pSC300 was done in a similar manner, except both the PCR product and vector were digested with PstI. The ligation reaction products were transformed into E. coli strain JM109 (25) and plated on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar containing 100 μg of ampicillin per ml. Plasmid DNA was prepared from the ampicillin-resistant transformants (16) and analyzed for the presence of the correct-size insert into pSC300. The plasmid constructs generated from the three-primer PCR method with the correct-size insert were additionally screened for the loss or addition of a restriction endonuclease recognition site that had been incorporated into the internal mutant primer (Table 1). The first plasmid identified as containing the desired nucleotide changes to code for an alanine residue at position 243 in LuxR was named “pAT243A.” This method was followed to name all of the plasmids encoding the mutant forms of luxR constructed for this study. The entire luxR gene and promoter region from each construct were sequenced on both strands at the Virginia Tech DNA Sequencing Facility by using the SEQVEC (GCTGAAAATCTTCTCTCATCC), SEQINT (GTTGTCTTTTTCTGAATGTGC), SEQPRO (GTATGGCTGTGCAGGTCGTAAATC), and SEQINT2 (ATGTAATTAAAGAAGCGAAAAC) primers. Due to second site mutations in luxR identified during the sequencing of pAT223A and pAT250A, the portion of luxR containing only the desired mutation was recloned into the PstI sites of pSC300 and resequenced.

Identifying alanine-substitution variants of LuxR defective in transcriptional activation of the lux operon.

The ability of the 38 variant forms of LuxR to activate transcription of the lux operon was determined in vivo with the reporter plasmid pJR551 (5), which codes for the lux operon with a Mu insertion inactivating luxI. E. coli JM109(pJR551) (pAT)-series strains were grown overnight at 30°C in LB broth containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml), and 200 nM 3-oxo-C6-HSL (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.2 to 1.0. The overnight cultures were subcultured into the same medium to an OD600 of 0.025 and grown at 30°C to an OD600 of 0.5. Luminescence output from 10 μl of culture was measured over a 4-s integration period in a Turner 20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, Calif.) with a sensitivity range over several logs. Cells from 0.5-ml aliquots of each culture at an OD600 of 0.5 were also harvested via centrifugation and frozen for use in luciferase and Western immunoblotting experiments.

The in vivo luminescence assays, performed in triplicate, were first used to test the effects of the mutations on LuxR-dependent activation of the lux operon in recombinant E. coli. Of the 38 strains encoding the alanine-substitution mutants tested in this study, 7 (with mutations at residues 212, 217, 225, 229, 230, 238, and 243) were found to emit 2% or less of the levels of luminescence observed with wild-type LuxR and 1 (residue 216) emitted approximately 30% of the wild-type levels of luminescence (data not shown). Those mutated forms of LuxR found to stimulate cellular luminescence at levels less than 50% of that of the wild-type control were considered to have a significant defect in transcriptional activation of the lux operon. The amino acid substitutions in these “dark” variants of LuxR were both conservative and nonconservative in nature (Fig. 1).

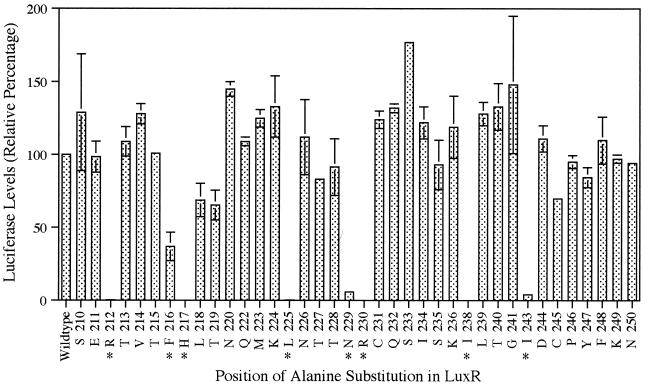

FIG. 1.

Effects of alanine substitutions on LuxR-dependent cellular luciferase levels in recombinant E. coli. The value for each alanine-substitution mutant represents the average of two independent experiments with individual luciferase assays performed in quadruplicate. The error bars represent the range of each experiment from the mean. The wild-type strain (pSC300) value was set at 100% for each experiment. The negative-control strain (pKK223-3; Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.) exhibited less than 0.3% of wild-type levels of luciferase (data not shown). The letter preceding each alanine-substitution position indicates an abbreviation for the amino acid residue at that position in the wild-type sequence. An asterisk highlights those LuxR variants exhibiting a “dark” phenotype (less than 50% of the wild-type levels of luminescence and luciferase).

Similar to measuring cellular β-galactosidase, the levels of luciferase found within cells can be quantitated (15) and used as a more direct measure of transcriptional activation from the promoter of the lux operon. Cells harvested as described above were resuspended in 0.5 ml of lysis buffer (10 mM KPO4 [pH 7.0], 10 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.1% bovine serum albumin [BSA], 50 μg of lysozyme per ml) and lysed via a single freeze-thaw step. Each luciferase reaction mixture contained the following final volumes of the reagents: 10 μl of crude cell extract, 10 μl of 1:1,000-diluted and sonicated n-decyl aldehyde (Decanal; Sigma), 90 μl of assay buffer (10 mM KPO4 [pH 7.0], 0.1% BSA, 1 mM DTT), and 100 μl of reduced flavin mononucleotide (FMNH2). The FMNH2 was added directly to the tube containing the other reagents only after the tube was placed within the chamber of the luminometer. The luminescence emitted from the reaction was measured (3-s delay, 30-s integration time) with a Turner 20/20 luminometer with a manual injection port.

All seven of the mutants (residues 212, 217, 225, 229, 230, 238, and 243) that emitted 2% or less of the wild-type level of luminescence in the luminescence assay were found to have 10% or less of the wild-type levels of luciferase (Fig. 1). The one mutant (residue 216) found to emit 30% of the wild-type level of luminescence had less than 40% of the wild-type level of luciferase (Fig. 1). Therefore, the alanine substitutions made at these eight positions affect the ability of LuxR to activate transcription of the lux operon and thus result in a “dark” phenotype. However, based on the luminescence and luciferase assays, it cannot be determined if this “dark” phenotype is the result of a mutation that affects the ability of LuxR to recognize and bind its target DNA, to alter the conformation of the lux promoter DNA, or to establish direct protein-protein associations with RNA polymerase (RNAP) at the lux operon promoter necessary for transcriptional initiation.

Do any of the alanine substitutions in LuxR result in an enhanced ability to activate transcription of the lux operon?

None of the strains expressing LuxR variants exhibited greater than 200% of wild-type luciferase levels in the presence of exogenous autoinducer (Fig. 1). However, since random mutagenesis of the C-terminal domain of LuxR has previously identified single amino acid substitutions that allow LuxR to activate transcription of the lux operon independent of autoinducer (14, 18), all 38 of the alanine-substitution mutants were also tested for this autoinducer-independent phenotype in the luminescence assay. Strains were grown as described above, except in the absence of autoinducer and at 31°C, since the mutation in luxI encoded on pJR551 is a temperature-sensitive mutation that will allow LuxI to synthesize autoinducer below 30°C (14). None of the alanine-substitution mutants was shown to exhibit an autoinducer-independent phenotype (data not shown).

Are the altered forms of LuxR expressed at levels equivalent to that of the wild type?

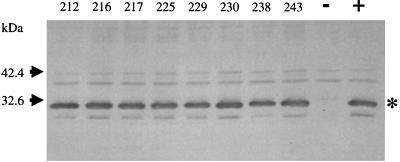

Cellular levels of the variant forms of LuxR were measured through Western immunoblotting (2) to verify that the results obtained in the luminescence and luciferase assays were not due to a difference in the levels of protein expression in comparison to that of the wild type. Equivalent amounts of total cellular proteins were electrophoresed through a 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–polyacrylamide resolving gel, and LuxR primary rabbit antiserum was used at a dilution of 1:1,000 to probe a nitrocellulose blot of the gel. A Western immunoblot of the strains exhibiting the “dark” phenotype in comparison to the wild type is shown (Fig. 2) as a representative sample of the Western immunoblotting analysis performed in triplicate for all of the 38 variant forms of LuxR. This analysis established that the expression levels of the variants are approximately equivalent to that of the wild type within E. coli. Furthermore, none have any apparent truncations.

FIG. 2.

Western immunoblot of cell extracts from strains exhibiting the “dark” phenotype. The LuxR band is highlighted with an asterisk on the right. The mobility of molecular size standards is indicated by arrows. Residue numbers for the position of the alanine substitutions in LuxR are given at the top. Lanes + and − illustrate the levels of wild-type LuxR expressed from pSC300 and from the vector control pKK223-3, respectively.

Do the alanine substitutions in LuxR affect its ability to bind to the lux box?

The effect of the alanine-substitution mutations on the ability of LuxR to bind to the lux box was determined in vivo with recombinant E. coli JM109 transformed with p35LB10 (7) and each of the 38 plasmids in the pAT series. The p35LB10 plasmid contains the lacZ gene fused to the E. coli consensus −10 and −35 sites, with the lux box located between these two sites. Binding of wild-type LuxR to the lux box in the presence of autoinducer represses transcription of lacZ. If a mutation affects the ability of LuxR to bind to the lux box, then this variant form of LuxR is unable to repress transcription of lacZ, resulting in high levels of cellular β-galactosidase. Cell extracts for the assays were obtained by growing strains overnight at 30°C in LB medium containing spectinomycin (100 μg/ml), gentamicin (10 μg/ml), and ampicillin (100 μg/ml) to an OD600 of 0.2 to 1.0. Each overnight culture was then subcultured to an OD600 of 0.025 into two sets of LB medium containing the appropriate antibiotics; one of the two sets also contained 200 nM 3-oxo-C6-HSL. All cultures were grown at 30°C to an OD600 of 0.5, and an aliquot was diluted 1:200 in Z buffer (60 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 400 nM DTT) and lysed by chloroform. β-Galactosidase levels of each mutant were measured with the Tropix chemiluminescent reporter assay kit (Tropix, Bedford, Mass.) and a Lucy 1 microplate luminometer (Rosys Anthos, Wals, Austria) as previously described (7).

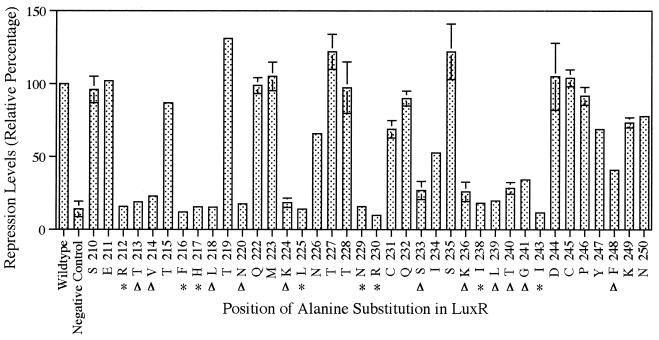

Nineteen strains expressing LuxR variants exhibited near-wild-type levels of DNA binding and repression (Fig. 3). All eight of the LuxR variants (212, 216, 217, 225, 229, 230, 238, and 243) conferring the “dark” phenotype in the luminescence and luciferase assays were also found to be unable to bind to the lux box in the DNA binding assay, with repression levels less than 20% of that of the wild type (Fig. 3). Therefore, it can be concluded that the alanine substitutions made at these positions affect the ability of LuxR to bind to the lux box in both the presence and absence of RNAP. Interestingly, 11 of the LuxR variants (213, 214, 218, 220, 224, 233, 236, 239, 240, 241, and 248), which had no effect in the luminescence and luciferase assays, were found to be deficient in their ability to bind to the lux box, with repression levels less than 50% of the wild-type level (Fig. 3). Thus, these 11 mutated forms of LuxR with defects in DNA binding appear fully functional in the presence, but not in the absence, of RNAP. The amino acid substitutions in these variants of LuxR were both conservative and nonconservative in nature (Fig. 3). LuxRΔN, a truncated form of LuxR containing only the C-terminal domain, has been purified and used for in vitro studies (20). It is capable of activating transcription of the lux genes in an autoinducer-independent manner in vivo, but like the 11 variants identified in this study, it can bind to the lux box in vivo (and in vitro) only in the presence of RNAP (3, 7, 20, 21). These findings support the idea that protein-protein interactions are involved in stabilization of the transcription complex at the lux operon promoter.

FIG. 3.

Effects of alanine substitutions on the ability of LuxR to bind to the lux box in recombinant E. coli. The value for each alanine-substitution mutant represents the average of two independent experiments each performed in triplicate. The error bars represent the range of each experiment from the mean. The wild-type value (pSC300) was set at 100% for each experiment, with the actual average value being equivalent to 7.48 ± 0.75-fold repression in the presence of 3-oxo-C6-HSL over all experiments. The negative-vector control (pKK223-3) value shown in the graph is the average value from all experiments. The letter preceding each alanine-substitution position indicates an abbreviation for the amino acid residue at that position in the wild-type sequence. An asterisk highlights those LuxR variants exhibiting a “dark” phenotype, and arrowheads highlight variants with wild-type levels of luminescence and luciferase but unable to bind to the lux box in the presence of 3-oxo-C6-HSL and to repress transcription in the assay.

It is impossible to conclude from the results of just the in vivo DNA binding-repression assay whether the observed defects in DNA binding are due to the disruption of protein-protein or specific DNA-amino acid interactions. However, the location of the HTH motif of NarL, a member of the FixJ-LuxR (11, 12) family of transcriptional activators, has been determined via analysis of its crystal structure, and based on this information, the HTH motif of LuxR is predicted to be located between residues 200 and 224 (1). Of the alanine substitutions made in LuxR that affect its ability to bind to the lux box, eight are found within the predicted HTH motif of LuxR (residues 212, 213, 214, 216, 217, 218, 220, and 224). It is possible that the amino acid residues at these positions in LuxR are making specific contacts with the DNA, but further work will be necessary to confirm the existence of these interactions.

None of the alanine substitutions made in the C-terminal 41 amino acids of LuxR affects its ability to activate transcription of the lux operon without affecting DNA binding (Fig. 1 and 3). The expected phenotype for such mutants would be “dark” in the luminescence and luciferase assays, but they show near 100% repression in the DNA binding assay. This is in contradiction to previous observations (4) that truncations of 10 to 40 amino acids from the C-terminal domain of LuxR result in a form of LuxR capable of binding to the DNA but not activating transcription. These findings were based on the assumption that LuxR employs the same mechanism to bind to the DNA at the promoter of the lux operon as it does at its own promoter during autorepression. Others have suggested that LuxR binds to its own promoter region during autoregulation via a mechanism different from that used for transcriptional activation of the lux operon (18). In vitro studies of the DNA binding properties of LuxRΔN also support this hypothesis (20, 21). This may explain why the autorepression assay (4, 5) did not identify the significance of the C-terminal 40 amino acids in DNA binding at the lux operon promoter. It is possible that the C-terminal 40 amino acids of LuxR are important for binding at the promoter of the lux operon, but not at the promoter of luxR.

More recent studies of the function of truncated forms of LuxR (3, 4) using the same DNA binding-repression assay performed in this study determined that deletions of more than 10 amino acids from the C terminus of LuxR resulted in the loss of the ability of LuxR to bind to the lux box (7). This result is consistent with our findings that the C-terminal 41 amino acids of LuxR have an important role in DNA binding but are not required exclusively for the mechanism of positive control used during transcriptional activation of the lux operon. Additional work will be necessary to identify the specific interactions between the amino acids in the C-terminal region of LuxR and the lux box sequence, as well as to locate alternative regions of the C-terminal domain of LuxR that may be involved in protein-protein associations necessary for transcriptional activation. The C-terminal domain of the α subunit of RNAP is required for LuxR-dependent transcriptional activation of the lux operon (22), and the lux box is located at a position overlapping the −35 recognition site for ς70 at the lux operon promoter. Therefore, LuxR may be functioning as an ambidextrous activator at this class II-type promoter (6, 22, 23). This is an additional line of evidence that suggests there are regions of LuxR involved in making protein-protein interactions with RNAP and/or involved in altering the conformation of the lux promoter DNA to facilitate binding of RNAP. Further alanine-scanning mutagenesis in the C-terminal domain of LuxR should be able to define this region associated with the positive control of expression of the lux operon. By identifying regions in LuxR that are making contacts with RNAP and the DNA, the mechanism of transcriptional activation used by LuxR and its homologues during quorum sensing will be better understood.

Acknowledgments

We thank the laboratory of E. P. Greenberg for the reagents and advice that they provided and Guy E. Townsend II for technical assistance.

This research was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (CAREER Award MCB-9875479) and from the Thomas F. and Kate Miller Jeffress Memorial Trust to A.M.S. and by a Sigma Xi Grants-in-Aid of Research Award to A.E.T.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baikalov I, Schröder I, Kaczor-Grzeskowiak M, Grzeskowiak K, Gunsalus R P, Dickerson R E. Structure of the Escherichia coli response regulator NarL. Biochemistry. 1996;35:11053–11061. doi: 10.1021/bi960919o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brahamsha B, Greenberg E P. A biochemical and cytological analysis of the complex periplasmic flagella from Spirochaeta aurantia. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4023–4032. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4023-4032.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi S H, Greenberg E P. The C-terminal region of the Vibrio fischeri LuxR protein contains an inducer-independent lux gene activating domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:11115–11119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi S H, Greenberg E P. Genetic dissection of DNA binding and luminescence gene activation by the Vibrio fischeri LuxR protein. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4064–4069. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.12.4064-4069.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunlap P V, Ray J M. Requirement for autoinducer in transcriptional negative autoregulation of the Vibrio fischeri luxR gene in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3549–3552. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.6.3549-3552.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egland K A, Greenberg E P. Quorum sensing in Vibrio fischeri: elements of the luxI promoter. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1197–1204. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egland K A, Greenberg E P. Conversion of the Vibrio fischeri transcriptional activator, LuxR, to a repressor. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:805–811. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.3.805-811.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuqua W C, Winans S C, Greenberg E P. Census and consensus in bacterial ecosystems: the LuxR-LuxI family of quorum-sensing transcriptional regulators. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:727–751. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenberg E P. Quorum sensing in gram-negative bacteria. ASM News. 1997;63:371–377. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanzelka B L, Greenberg E P. Evidence that the N-terminal region of the Vibrio fischeri LuxR protein constitutes an autoinducer-binding domain. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:815–817. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.3.815-817.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henikoff S, Wallace J C, Brown J P. Finding protein similarities with nucleotide sequence databases. Methods Enzymol. 1990;183:111–132. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)83009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kahn D, Ditta G. Modular structure of FixJ: homology of the transcriptional activator domain with the −35 binding domain of sigma factors. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:987–997. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michael S F. Mutagenesis by incorporation of a phosphorylated oligo during PCR amplification. BioTechniques. 1994;16:410–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poellinger K A, Lee J P, Parales J V, Jr, Greenberg E P. Intragenic suppression of a luxR mutation: characterization of an autoinducer-independent LuxR. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;129:97–102. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(95)00145-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosson R A, Nealson K H. Autoinduction of bacterial bioluminescence in a carbon limited chemostat. Arch Microbiol. 1981;129:299–304. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shadel G S, Young R, Baldwin T O. Use of regulated cell lysis in a lethal genetic selection in Escherichia coli: identification of the autoinducer-binding region of the LuxR protein from Vibrio fischeri ATCC 7744. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3980–3987. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.3980-3987.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sitnikov D M, Shadel G S, Baldwin T O. Autoinducer-independent mutants of the LuxR transcriptional activator exhibit differential effects on the two lux promoters of Vibrio fischeri. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;252:622–625. doi: 10.1007/BF02172408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slock J, VanRiet D, Kolibachuk D, Greenberg E P. Critical regions of the Vibrio fischeri LuxR protein defined by mutational analysis. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3974–3979. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.3974-3979.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stevens A M, Dolan K M, Greenberg E P. Synergistic binding of the Vibrio fischeri LuxR transcriptional activator domain and RNA polymerase to the lux promoter region. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12619–12623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stevens A M, Greenberg E P. Quorum sensing in Vibrio fischeri: essential elements for activation of the luminescence genes. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:557–562. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.2.557-562.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stevens A M, Fujita N, Ishihama A, Greenberg E P. Involvement of the RNA polymerase α-subunit C-terminal domain in LuxR-dependent activation of the Vibrio fischeri luminescence genes. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4704–4707. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.15.4704-4707.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevens A M, Greenberg E P. Transcriptional activation by LuxR. In: Dunny G M, Winans S C, editors. Cell-cell signaling in bacteria. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1999. pp. 231–242. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swift S, Throup J P, Williams P, Salmond G P C, Stewart G S A B. Quorum sensing: a population-density component in the determination of bacterial phenotype. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:214–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]