Abstract

Devising an appropriate dental treatment plan for patients with pre-existing medical conditions is a demanding task. Dentists must consider the sometimes life threatening, interactions between ongoing medical conditions and dental treatment. Stakes are particularly high for the elderly on prescription drugs and other therapies for medical conditions while they seek dental care for advanced oral diseases. Given that Japan is an ageing society, it is crucial to create avenues for medical and dental practitioners to share patient information and collaborate.to,improve care This paper examined trends from demographic data to suggest that there is an impending further rise in the number of medically compromised elderly seeking dental treatment. For patient safety and improved public health, it is important that dental practitioners evaluate the nature and ongoing treatment of pre-existing medical conditions amongst new patients and account for their impact on dedicated and dental status. This paper supports the relevance of comprehensive clinical practice guidelines and the need to train dental practitioners to adopt a multidisciplinary approach to dental care. In order to meet the future needs of an ageing population, the Japanese Society of Dentistry for Medically Compromised Patients needs to take initiative and suggest mechanisms to exchange patient information freely and encourage multidisciplinary dental practices.

Keywords: Gerodontology, Medically compromised dental patients, Contraindicative drug administration, Elderly patient safety, Clinical practice guidelines, Medical and dental collaboration

1. Introduction

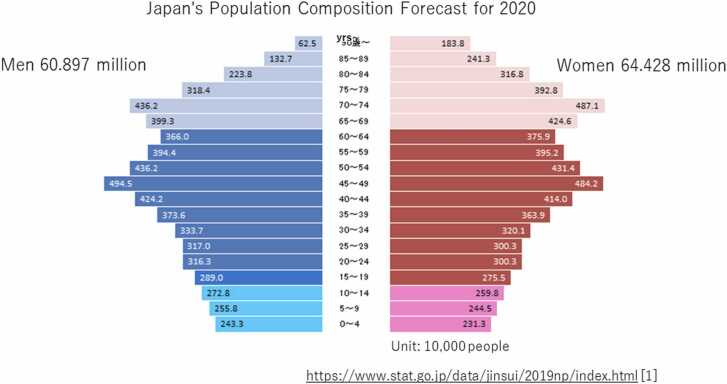

The total population of Japan as of October, 2019, was126.17 million. The population 65 years or older was 5 % of the population in 1950, over 7 % in 1970 (so-called aging society) and over 14 % (so-called aged society) in 1994. In 2019, the population aged 65 or over will be 35.89 million, accounting for 28.4 % of the total population (aging rate). In addition, the "population aged 65–74 (so-called early-stage elderly)" is 17.4 million, and the "population aged 75 or over (so-called late-stage elderly)" is 18.49 million, and the number of late-stage elderly tends to increase. (Fig. 1) [1] The prevalence of these populations aged 65 or over is shown in Table 1. On the other hand, in terms of changes by age group of patients who received dental treatment in Japan, the number of patients aged 65 or over has increased since 1999. It was 40.9 % in 2014. [2] With these changing demographics in Japan, it is notable that there are many more patients having geriatric medical problems that dentists should take into account affecting dental treatment they provide. (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Japan's Population Composition Forecast for 2020 https://www.stat.go.jp/data/jinsui/2019np/index.html [1].

Table 1.

Treatment rate by major disease (per 100,000 population) https://www.stat.go.jp/data/jinsui/2019np/index.html[2].

|

1.1. Challenges in providing dental care to medically compromised patients

The Japanese Society of Dentistry for Medically Compromised Patients (JSDMCP) endeavors to conduct academic studies and identify the changes in disease patterns associated with certain demographic segments. The intention behind such studies is to find ways to provide safe and appropriate dental care for dental patients who need medical considerations by collaborating with other medical professionals. These collaborations are essential to the provision of quality dental care. Lockhart’s “Dental Care of the Medically Complex Patients,” published in the United States in 1985, provides a framework for this endeavor [3]. With Lockhart as a guide to some programs, one and two year postgraduate training courses in oral medicine were inaugurated in graduate dental education in North America. The purpose of oral medicine residencies are deepen their knowledge and skill about the role of dentistry in the health care system, develop working relationships with physicians and the whole health care team in the collaborative management of patients with complex diseases. Bui et al. described this field as the “management of medically compromised patients,” citing the following diseases [4]. These are consistent with current concepts of dental care for medically compromised patients in Japan: for example, cardiac dysfunction, pulmonary dysfunction, hypertension, renal dysfunction, hepatic dysfunction, hemorrhagic tendencies, epilepsy, diabetes, thyroid diseases, corticosteroid use, immune dysfunction, and HIV infection are key areas for necessary collaboration.

Parnell et al. pointed out the importance of dealing with medically compromised patients receiving dental treatment in 1986[5]. In 1991, study groups in Japan that were already involved in this field were integrated to form the JSDMCP. The society has worked for the last 30 years to promote oral surgery, dental anesthesiology, hospital dentistry, and general dentists. The society is also involved in identifying the best strategies in the management of patients with other medical problems who consult dentists, and to provide them with safe dental care. In Japan, dental care for medically compromised patients is seen as a field that attempts to understand general pathophysiology and provide safe dental care in support of improved overall patient outcomes.

There is a need for improved education and methods to provide appropriate dental treatment to patients who require a comprehensive risk assessment of dental treatment. In this therapeutic system, the dental practitioners work in collaboration with physicians and other health care providers in an interprofessional team [6]. Several textbooks have been published on how to evaluate and medically manage dental treatment for medically compromised patients to ensure safe dental treatment [7], [8], [9]. This is a very important field for the future development of dental care in a society as old as Japan’s, where the basic unit of medical care emerging is the comprehensive regional care system. Creating public awareness about the existence of this field, promoting understanding of what it involves and why it is necessary, and training specialists across domains and over a wide area are important tasks for the future.

Herein are the initiatives that the JSDMCP should undertake to achieve these goals.

1.2. Status and treatment of medically compromised patients who consult dentists in Japan

Japan leads the world in its aging of the population. This means that it is likely that even general dental clinics today frequently provide dental therapies for medically compromised patients. Dental care for medically compromised patients needs to involve collaborating with primary care physicians by sharing medical records, direct communication with the health care team, monitoring patients during treatment, and reciprocal communication by the dental team regarding oral health status and its impact on overall health status.

Considering the complexity of this treatment process, it may be more time-consuming as compared for both the medical and dental team. This can be facilitated through reciprocal access to the electronic dental and medical record.

In a report, around 30% of patients at dental clinics were medically compromised before 2005 [10]. Until 2014, the percentage of medically compromised patients had increased to 40% at general dental clinics and 61.5 % at university hospitals. With age, the likelihood of people suffering from multiple diseases also increases. It has been reported that 45.2 % of people in their 50 s and 80% people in their 70s and older are medically compromised [10]. Table 2 shows examples of relationships between medical problems and dentistry that are commonly encountered in medically compromised patients [11].

Table 2.

Relationships between medical problems and dentistry Yamada et al.[11] reorganization.

|

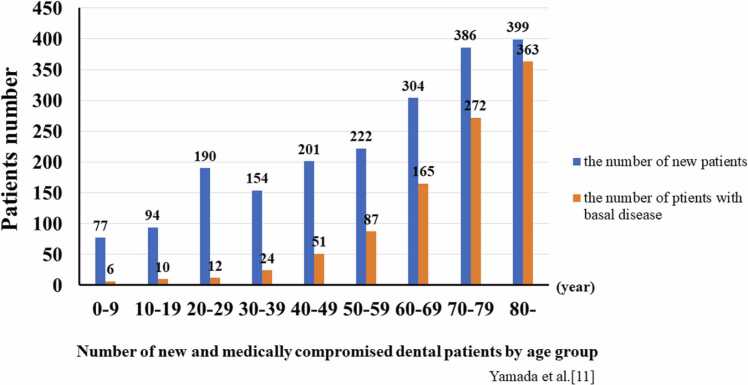

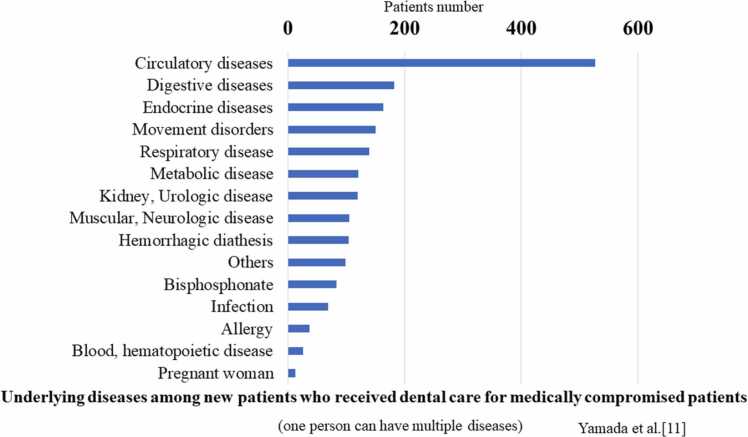

In 2018, the JSDMCP’s Research and Planning Guideline Project Committee surveyed 18 dentistry and dental/oral surgery departments in hospitals situated in Nagano Prefecture [11]. Most of the new patients were referred by other hospital departments or dental clinics. Of these new patients, 42.2 % (a total of 1001 patients) suffered from diseases that would pose medical issues during dental treatment. When these patients were segregated age-wise, this percentage increased to 54.3% for patients aged 60–69 years, 70.4 % for patients aged 70–79 years, and 91.0 % for those aged 80 years and above. The most common underlying disease was cardiovascular disease (52.6 %), followed by gastrointestinal and endocrine diseases (35.0 %). Complications occurred in sixteen of these patients after dental therapy. Complications involved the digestive system in five cases, endocrine system in five cases, circulatory system in three cases, and metabolic system in three cases. (Fig. 2, Fig. 3)[11]. As the aging of patients undergoing dental care progresses, the proportion of medically compromised patients increases. Of these, screening for cardiovascular disease is particularly important [12].

Fig. 2.

Number of new and medically compromised dental patients by age group Yamada S, Kurita H, Tanaka A, Miyata M, Morimoto Y, Yamaguchi A, et al. [11].

Fig. 3.

Underlying diseases among new patients who received dental care for medically compromised patients (one person can have multiple diseases) Yamada S, Kurita H, Tanaka A, Miyata M, Morimoto Y, Yamaguchi A, et al. [11].

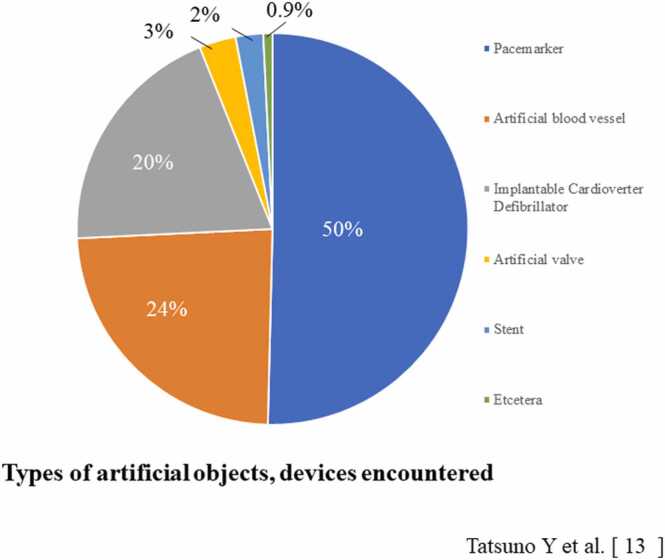

In 2018, the committee surveyed 2050 members of JSDMCP and others involved in hospital dentistry and oral surgery regarding dental care for patients with implanted alloplastic materials and devices. The data revealed that 91.9 % of dentists had experienced encountering patients with such devices during dental care. These devices included pacemakers in 50 % of cases and alloplastic vascular devices in 24 % cases, followed by implantable defibrillators 20 %, artificial valves 3 %, and stents 2 % (Fig. 4) [13]. The respondents dealt with these situations by not using electrocauterization devices, using prophylactic antimicrobials, and minimizing bacteremia with, for example, ultrasonic scalers, or root canal meters. Complications associated with dental therapies included bleeding, device infections, bacterial endocarditis, and injury associated with electrocauterization. While 63 % of the dentists surveyed were aware of and dealt with issues involving implanted devices during dental therapy, only 30 % reported that they had shared this medical information with dental or medical departments.

Fig. 4.

Types of artificial objects, devices encountered Tatsuno Y, Morimoto Y, Yamada S, Kurita H, Tanaka A, Yamaguchi A, Miyata M, et al. [13].

According to a survey by the Japanese Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications Statistics Bureau, it is reported that, by 2040, people aged 65 or over will account for 50 % of the total population [14]. The report also indicates that there will be a substantial increase in the proportion of individuals aged 85 years and older. Further, according to the Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions from 2016 conducted by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, there is a sharp rise in the demand for dental care, particularly among people aged 70 years and above. The proportion of consultations at medical institutions for “diseases involving the teeth” was preceded only by widespread systemic diseases such as hypertension and diabetes [15]. Considering these statistics, it is reasonable to expect that, by 2040, dental departments will be managingan increased number of patients, especially elderly patients with pre-existing medical problems that require monitoring and management while providing dental treatment.

The JSDMCP holds educational workshops to create awareness and increase knowledge the issue. These workshops can also be attended by non-members; however, attendees are limited to about 200 people. Going forward, to provide the public with safe and high-quality dental care, minimum requirement programs in undergraduate and continuing dental education should be promulgated. It is important to help dental practitioners develop the knowledge and skills needed to manage medically compromised patients. This curriculum must also be incorporated into a specialty system for dental care for elderly patients and those receiving long-term care. Encouraging medical-dental cooperation in the community will require promoting projects to build community medical systems that involve public health policy,governmental health education oversight, medical associations, and dental associations. This will facilitate the sharing of information between dentists and other medical professionals in order to comprehensively manage medically compromised patients.

1.3. Taking into account the oral medications consumed by medically compromised and elderly patients before dental treatment

With an increasing number of elderly people receiving dental care, the occurrence of adverse events among those taking multiple medications, known as polypharmacy, is also an important issue [16], [17]. In addition to drugs that can directly impact dental therapies, such as antithrombotic agents and bone resorption inhibitors, many drugs cause side effects in the oral mucosa and oral environment (Table 3). [7], [18]. Problems related to polypharmacy and their interaction with oral health issues can be life-threatening, especially in the elderly. These include drug-related adverse events, poor medication adherence, reduced renal function, under nutrition, and drug interactions. For example, inability to eat after dental surgery can be associated with important changes in glycemic control or absorption of medications. In addition to the steps described above for addressing the diseases during dental care for medically compromised patients, practitioners must consider these problems. Yuki et al. reported a survey of oral medications taken by new patients in the JSDMCP [19]. Out of 301 patients, 59.1 % were taking one or more oral medications, the highest being 14 drugs by a single patient. Of the 163 patients aged 65 years and above, 84.6 % were taking oral medications. On an average, those aged 70 years and above, were consuming five drugs. Considering the types of these drugs, 35.5 % were antihypertensive agents, 21.9 % were drugs for peptic ulcers, 21.2 % drugs were neuropsychiatric agents, 17.6 % were antipyretic anti-inflammatory analgesics, and 16.2 % drugs were to treat hyperlipidemia.

Table 3.

Dental problems with medication Yamada et al.[11] reorganization.

|

It is important to devise comprehensive and collaborative dental treatment options, especially for the elderly, considering that 80 % of people aged 65 and above are taking some kind of systemic medication. The number and types of drugs increase in patients over 70 years old. The ongoing medical treatments of new patients need to be understood in detail, and this information should influence how their pathophysiology is understood. Therefore, it is imperative to check medication handbooks that the patient has at the time of dental treatment to provide safe treatment. The medical team also should be aware of the impact oral surgical and other dental procedures can have on systemic pharmacy.

The concomitant use of epinephrine is often contraindicated or cautioned against when a patient is on neuropsychiatric drugs especially tricyclic antidepressants. In addition, some drugs may cause side effects involving oral functions, such as swallowing disorders. Approximately 700 drug varieties, including diuretics, antihistamines, and neuropsychiatric agents, have dry mouth as a side effect. Therefore, in patients with impaired oral functions, such as mastication and swallowing issues, the relationship with their oral medications needs to be considered in medical examinations to devise an appropriate dental plan.

Additionally, when a new dental prescription is provided to a patient who is already taking oral medications, the occurrence of any possible interactions deserves attention. In particular, many antibacterial agents and analgesics that are commonly indicated in dentistry can increase the anticoagulant effect of Warfarin® beyond its optimal therapeutic range to cause organ bleeding. The effects of antibacterial agents on enterobacteria can suppress the production of vitamin K, which can enhance the anticoagulant effect of Warfarin®. This can be exacerbated by a consumption of clotting factors is oral surgery such as extractions occur. Thus, the Warfarin® dose must be adjusted based on a careful monitoring of clotting functions. Epinephrine, which is used in local anesthetics, is a β agonist that can cause blood pressure to rise when used with the antihypertensive β-blocker propranolol (Inderal®) [20]. It is important to check the package inserts of drugs that are frequently used in dentistry, such as antibacterial agents, anti-inflammatory drugs, and local anesthetics, for their interactions and to pay attention to this on a regular basis.

1.4. Purpose and relevance of clinical practice guidelines such as the “Guidelines for tooth extraction in patients on antithrombotic therapy”

Clinical practice guidelines are evidence-based, systematic documents intended to assist clinicians and patients in making appropriate decisions about specific clinical situations. Little et al. recommend local hemostasis to treat bleeding in dental treatment in patients receiving antithrombotic therapy [21]. In 2010, the JSDMCP, in collaboration with the Japanese Society of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons and the Japanese Society of Gerodontology, created the “Evidence-based guidelines for tooth extraction in patients on antithrombotic therapy.” These guidelines were revised in 2015 in consideration of changes to antithrombotic therapy and then again in 2020 [22], [23]. The latest edition includes the following comprehensive question: “Should patients on antithrombotic agents stop taking them for tooth extraction or continue to take them?” and “Does the decision to suspend administration depend on the postoperative hemostatic treatment?” For this study, it was first considered a clinical question and it was attempted to be solved through a systematic review [24], [25]. However, these clinical investigations were found to be extremely limited. The basic response follows the 2010 and 2015 editions in recommending patients to continue taking an antithrombotic during tooth extraction with appropriate hemostatic treatment. There have been many clinical reports based on these guidelines. Kondo et al. created a checklist to evaluate whether tooth extraction is feasible in patients taking an antithrombotic and reported its status [26]. Amemiya et al. reported that the rate of secondary hemorrhage was higher in patients taking both antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants and was lower with direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) [27]. These guidelines are widely used, and many institutions have reported that tooth extraction can be carried out safely while patients continue taking antithrombotics, if properly managed [28], [29], [30]. As the Japanese society becomes older, the number of patients taking antithrombotics will increase, along with the number of patients receiving dental care. The types of antithrombotic agents and their use also change over time. Tooth extraction is a common procedure in dentistry, and the impact of unwanted hemorrhage can be devastating. Thus continued clinical research needs to be performed and incorporated into clinical guidelines in this regard. The current revised guidelines provide an explanation for antithrombotic therapy and its impact vis a vis dental care. Practitioners need to share the content of treatments with primary care physicians based on an understanding of this topic and to continue to encourage appropriate responses in dentistry.

1.5. A multidisciplinary approach to dental therapy for medically compromised patients in collaboration with hospital dentistry

The ability to carry out a procedure in a general dental clinic is influenced by the patient’s condition and the equipment available at the clinic. High-risk patients, who required difficult procedures and advanced systemic management, should be referred to dental clinics with inpatient beds or secondary care hospital. Thus, the need for such care is expected to increase. The dentistry unit that will provide this care is situated in the environment of a general hospital, where multidisciplinary approaches can be adapted to the needs of patients. Specifically, systemic diseases that pose risks during dental treatment can be controlled by appropriate medical specialists, and dental care can be provided with inpatient management, including laboratory tests and imaging examinations such as CT and MRI, monitoring of vital signs, and intravenous sedation and general anesthesia. In 2020, the priority goal of the Japan Dental Association was to assign dentists to regional core hospitals, in order to sustain the oral health care management of regional medical care system. It is important to build systems for medical cooperation between hospitals and clinics in a community to provide focused and efficient inpatient dental treatment for high-risk patients, such as elderly people who require long-term care and people with disabilities [31]. In the future, it will be necessary to develop an education system for dentists to learn the knowledge and skills for medical and long-term care other than dentistry, in order to communicate with various occupations related to them. At the same time, more hospital dental departments are needed to support the need for dental care in an interprofessional environment. The dental care described in this paper provides a template for future safe dental services for medically compromised patients. In a society where the number of elderly people continues to increase, expertize in medically compromised patients is an essential component of dental practice. Goal achievement will be achieved only thorough training both before and after graduation to create professionals who can take on these roles.

2. Conclusion

Japan’s rapidly aging society needs dental care suited for medically compromised and other high-risk patients, which can also be provided to home bound or institutionalized patients. In addition, as the respective positions of systemic and oral health management have become clearer, society’s need for dentistry has increased. Further development of dentistry for medically compromised patients, as discussed here, will create useful tools for bringing dentistry and medicine closer together. Our purpose will be achieved through the training in dentistry for medically compromised patients in dental schools, clinical training, and continuing education, as well as the expansion of hospital dentistry.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Hiroshi Imai, director of the Japanese Society of Dentistry for Medically Compromised Patients, for giving me the opportunity to write this article.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.https://www.stat.go.jp/data/jinsui/2019np/index.html

- 2.https://www8.cao.go.jp/kourei/whitepaper/w-2017/html/zenbun/s1_2_3.html

- 3.Lockhart P.B., editor. Oral Medicine and Medically Complex Patients. sixth ed. Wiley-Blackwell; New Jersey: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bui C.H., Seldin E.B., Dodson T.B. Types, frequencies, and risk factors for complications after third molar extraction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(12):1379–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parnell A.G. The medically compromised patient. Int Dent J. 1986;36:77–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imai Y, Iwabuchi H (editors). Dentistry for medically compromised patients. Kyoto: Nagasue Shoten; 2021, p. 5–9 (in Japanese).

- 7.Seymour R.A. Dentistry and the medically compromised patient. Sur J R Coll Surg. 2003;4:207–214. doi: 10.1016/s1479-666x(03)80019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank M. Recognition, assessment and safe management of the medically compromised patient in dentistry. Anesth Prog. 1990;37:217–222. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diego R.G. Indications and contraindications of dental implants in medically compromised patients: update. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2014;1(19):e483–e489. doi: 10.4317/medoral.19565. (5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ono K., Miyagawa A., Jinno Y., Tochimura M. A clinical study on dental and oral surgical treatment of pregnant patients in our hospital. J Hokkaido Dent Assoc. 2014;69:89–92. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamada S., Kurita H., Tanaka A., Miyata M., Morimoto Y., Yamaguchi A., et al. A clinical investigation of dental treatment in medically compromised patients at dentistry and oral surgery department in Nagano prefecture. J Jpn Soc Dent Med Compromised Patient. 2019;28(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pamplona M.C., Soriano Y.J., Pérez M.G.S. Dental considerations in patients with heart disease. J Clin Exp Dent. 2011;3(2):e97–e105. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tatsuno Y., Morimoto Y., Yamada S., Kurita H., Tanaka A., Yamaguchi A., et al. The effects of implanted devices on dental treatment—Results of a nationwide questionnaire for dentists. J Jpn Soc Dent Med Compromised Patient. 2020;29(6):291–297. [Google Scholar]

- 14.https://www.ipss.go.jp/pp-zenkoku/j/zenkoku2017/pp_zenkoku2017.asp

- 15.https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/k-tyosa/k-tyosa19/dl/04.pdf

- 16.Kose E., Wakabayashi H., Yasuno N. Polypharmacy and malnutrition management of elderly perioperative patients with cancer: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2021;13:1961. doi: 10.3390/nu13061961. https//doi.org/10.3390/nu13061961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakamura J., Kitagaki K., Ueda Y., Nishio E., Shibatsuji T., Uchihashi Y., et al. Impact of polypharmacy on oral health status in eldery patients admitted to the recovery and rehabilitation ward.Geriatr. Gerontol Int. 2020 doi: 10.1111/ggi.14104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinstock R.J., Johnson M.P. Review of top 10 prescribed drugs and their interaction with dental treatment. Dent Clin N Am. 2016;60(2):421–434. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuki R., Tsurumaki H. A study of oral medication for new patients in the department of dentistry and oral surgery. J Jpn Soc Dent Med Compromised Patient. 2021;30(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wells P.S., Holbrook A.M., Crownther N.R., Hirsh J. Interactions of warfarin with drugs and food. Ann Inter Med. 1994:676–683. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-9-199411010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Little J.W., Miller C.S., Henry G.R., McIntosh B.A. Antithrombotic agents: implications in dentistry. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radio Endod. 2002;93:544–551. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.121391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Japanese Society of Dentistry for Medically Compromised Patients, Japanese society of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, Japanese society of Gerodontology, Evidence-based Guidelines for tooth extraction for antithrombotic therapy patients 2015, Tokyo:Gakujutusha,;2015.

- 23.Japanese Society of Dentistry for Medically Compromised Patients, Japanese society of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, Japanese society of Gerodontology, Evidence-based Guidelines for tooth extraction for antithrombotic therapy patients 2020, Tokyo:Gakujutusha,;2021.

- 24.Kawamata H (editor). Guidelines for tooth extraction in patients on antithrombotic therapy. Gakujutusha; 2020, p. 36–39, p. 42–47 (in Japanese).

- 25.Kurita H. New guidelines on tooth extraction in patients on antithrombotic therapy. J Jpn Soc Dent Med Compromised Patient. 2020;29(1):58–60. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kondo E., Yoshimura N., Yokoseki M., Sakurai A., Yamada S., Kurita H. What are the criteria for allowing outpatient tooth extraction in patients on antithrombotic medication? Evaluation sheet and its validity. J Jpn Soc Dent Med Compromised Patient. 2020;29(2):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amemiya K., Kuwasawa T., Takeo K., Aoki K. Tooth extraction in patients undergoing antithrombotic therapy. J Jpn Soc Dent Med Compromised Patient. 2018;27(6):422–435. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fujimori M., Toriyabe Y., Ohtsubo S., Nishimura T., Shimazu S., Suetsugu H., et al. A multicenter prospective study of simple tooth extraction in patients on antithrombotic therapy. Kokubyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2014;63(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toyota M., Minagi S. Hemostatic management after tooth extraction in patients under ongoing antithrombotic therapy. Jpn J Gerodontol. 2012;27(1):25–29. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maria M., Dimitrios A.T. Management of antithrombotic agents in oral surgery. Dent J. 2015;3:93–101. doi: 10.3390/dj3040093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ishida Y., Kondo T., Iida A. The study on the role of dental clinics with implants facilities through the experience of dental treatments under general anesthesia in patients referred by hospital dentistry units. J Jpn Soc Dent Med Compromised Patient. 2018;27(2):88–93. [Google Scholar]