Abstract

Of all the cell types arising from the neural crest, ectomesenchyme is likely the most unusual. In contrast to the neuroglial cells generated by neural crest throughout the embryo, consistent with its ectodermal origin, cranial neural crest-derived cells (CNCCs) generate many connective tissue and skeletal cell types in common with mesoderm. Whether this ectoderm-derived mesenchyme (ectomesenchyme) potential reflects a distinct developmental origin from other CNCC lineages, and/or epigenetic reprogramming of the ectoderm, remains debated. Whereas decades of lineage tracing studies have defined the potential of CNCC ectomesenchyme, these are being revisited by modern genetic techniques. Recent work is also shedding light on the extent to which intrinsic and extrinsic cues determine ectomesenchyme potential, and whether maintenance or reacquisition of CNCC multipotency influences craniofacial repair.

Keywords: Cranial neural crest, ectomesenchyme, craniofacial skeleton, multipotency, vertebrate head

1. Introduction

The embryonic origins and potential of the mesenchyme contributing to the facial skeleton has fascinated, and often bitterly divided, some of the greatest developmental biologists of the past two centuries. Following Kastschenko’s observations of a different origin of mesenchyme of the head versus trunk in shark embryos in 1888 (Kastschenko, 1888), Julia Platt famously proposed an ectodermal origin of skeletogenic head mesenchyme (“mesectoderm”) in amphibians in 1893 (Platt, 1893), a concept disparaged for nearly four decades in that it contradicted prevalent germ-layer theory of an exclusive mesodermal origin of mesenchyme (Lankester, 1873). By the 1940s, studies in diverse vertebrates ((Hörstadius and Sellman, 1941; Landacre, 1921; Raven, 1931; Stone, 1929); reviewed in (de Beer, 1947; Hall, 2008)) had corroborated Platt’s claims, with Gavin De Beer coining the term “ectomesenchyme” in 1947 (de Beer, 1947), Sven Horstadius publishing a treatise on CNCC ectomesenchyme derivates in 1950 (Hörstadius 1950), and Nicole LeDouarin and Marianne Bronner mapping CNCC potential at the tissue and single-cell level in the late 20th century (Baker et al., 1997; Baroffio et al., 1991; Bronner-Fraser and Fraser, 1988; Le Lievre and Le Douarin, 1975). Nonetheless, questions remain about the developmental mechanisms by which the ectoderm acquires mesenchymal potential (Weston et al., 2004), and modern genetic lineage tracing techniques are revealing surprising plasticity of ectomesenchyme fate. While investigations into CNCC ectomesenchyme continue to address fundamental issues of cell potential and plasticity, it remains clear that the emergence of this unusual cell population in early vertebrates was instrumental in evolution of the vertebrate new head (Gans and Northcutt, 1983).

The neural crest is a vertebrate-specific cell population that delaminates from the edges of the developing neural epithelium during neurulation stages. Whereas neural crest forms along nearly the entire anteroposterior axis, CNCCs in the head region are unique in forming mesenchymal cell types. In this review, we discuss recent evidence that the ability of CNCCs to form both ectoderm-like derivatives (e.g. neurons and glia) and mesoderm-like derivatives (e.g. skeleton) reflects maintenance of pluripotency from blastula stages versus reacquisition of broad fate potential through extensive chromatin remodeling. We also discuss similarities to neuromesodermal progenitors in the trunk that also retain the ability to form both neural and mesenchymal derivatives through late neurulation stages. Whereas historical lineage tracing studies, based primarily on dye labeling and avian chimeras, have led to a large catalog of cell types generated from CNCC ectomesenchyme, we will discuss how genetic recombination-based lineage tracing are revealing unexpected CNCC contributions. These include species-specific contributions to specialized vascular endothelial cells of the fish gills, and epithelia of the mammalian middle ear cavity. We then contrast ectomesenchyme potential of cranial and trunk neural crest cells, and experimental manipulations that can reveal latent ectomesenchyme potential of trunk crest. Further, increasing evidence that CNCC ectomesenchyme and mesoderm have similar potential suggests that it is the local inductive signals, rather than the germ layer origins, that dictate cell fate. Finally, we discuss whether CNCCs may have greater capacity than mesodermal cells to repair craniofacial bone, through either perdurance of multipotency from embryonic stages or reacquisition of an embryonic ectomesenchyme-like state in response to injury. This review will take a critical look at the extent to which the neural crest, and in particular the CNCC ectomesenchyme, represents a fourth germ layer with unique properties to the other three (ectoderm, endoderm, mesoderm), or rather reflects much greater plasticity of cells from any germ layer to form diverse cell types when presented with the right inductive cues.

2. Developmental Transitions During Ectomesenchyme Formation

2.1. Is ectomesenchyme formation a type of delayed gastrulation?

Formation of the neural crest, including the ectomesenchyme component, has traditionally been viewed as an inductive epithelial to mesenchyme transition (EMT) of the post-gastrula neural ectoderm. Neural crest specification, followed by EMT and migratory dispersal of cells throughout the embryo, is induced by a combination of Wnt and balanced Bmp signaling (Garcia-Castro et al., 2002; Steventon et al., 2009). This process bears striking similarities to gastrulation in the earlier epiblast. Particularly in amniotes, accumulation of epiblast epithelial cells in a “primitive streak” at the dorsal midline followed by their ingression and involution through EMT to form the paraxial and somatic mesoderm, is topographically similar to the EMT of dorsal ectodermal cells that form CNCC ectomesenchyme at later stages (Figure 1). Mesoderm and ectomesenchyme generate many cell types in common, including skeleton, muscle, connective tissue, and endothelial cells. Both gastrula-stage mesoderm and CNCC ectomesenchyme formation require Wnt, Bmp, and Fgf signaling (Acloque et al., 2009; Garcia-Castro et al., 2002; Monsoro-Burq et al., 2003; Steventon et al., 2009), as well as common sets of EMT genes including Snail/Slug and Twist family members (Bildsoe et al., 2009; Chen and Behringer, 1995; Das and Crump, 2012); indeed, the role of Twist in EMT and mesoderm formation is conserved in invertebrates such as fly (Thisse et al., 1987) and sea urchin (Wu et al., 2008). There are, of course, differences in the two processes: e.g., gastrulation uniquely generates endodermal epithelia, and neural crest uniquely generates migratory mesenchymal cells that will form the neurons and glia of the peripheral nervous system. Nonetheless, an emerging view is that, rather than being a completely novel population (Gans and Northcutt, 1983), the neural crest, and in particular the CNCC ectomesenchyme, represents a population of epiblast cells whose ingressive gastrulation movements have been delayed until neurulation stages (Weston et al., 2004).

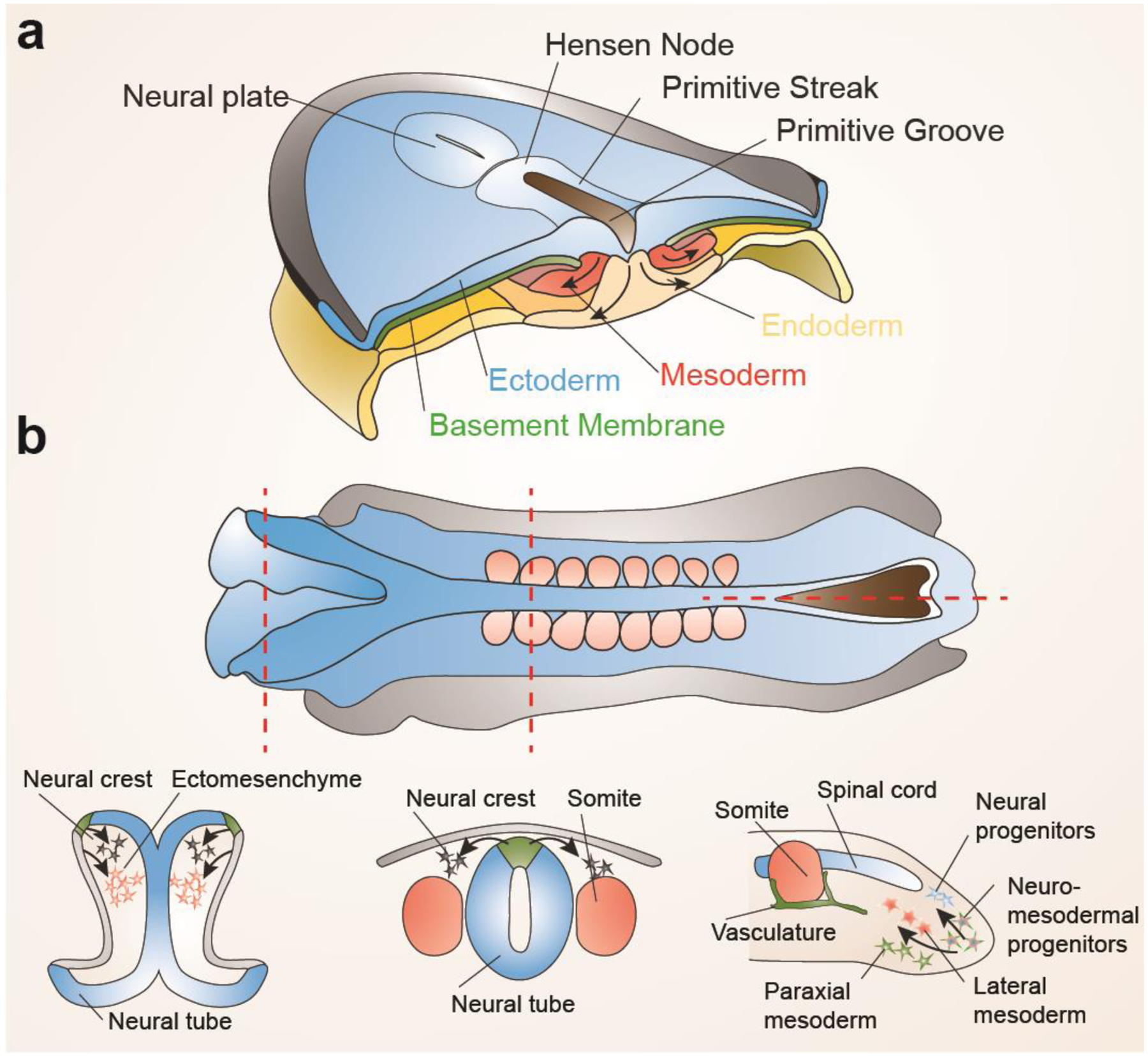

Figure 1. Comparison of neural crest formation to gastrulation.

a, During gastrulation in amniotes, ingression of ectoderm at the primitive streak through an epithelial to mesenchymal transition generates mesoderm and endoderm. b, At neurulation stages, similar epithelial to mesenchymal transitions occur along the length of the embryo. In the cranial region, ingression from the neural plate border (green) generates neural crest precursors for neurons, glia, and pigment cells, and ingression from the non-neural ectoderm (grey) contributes to ectomesenchyme, a cell population with highly overlapping fate potential to mesoderm. In the trunk, ingression from the neural plate border but not non-neural ectoderm generates neural crest with only neuroglial and pigment potential. In the tail, ingression of neuro-mesodermal progenitors generates spinal cord neurons and mesoderm, reminiscent of the dual neural and mesodermal potential of cranial neural crest.

A recent topic of debate is whether CNCCs are a monolithic, multipotent population giving rise to both ectomesenchyme and non-ectomesenchyme (primarily neural, glial, pigment) cell types. Alternatively, it has been proposed that ectomesenchyme represents a highly related but ultimately distinct population from “authentic” neural crest generating non-ectomesenchyme derivatives in both the cranial and trunk regions (Weston et al., 2004). When cultured in vitro, single neural crest cells can generate clones containing both mesenchymal and neuroglial cell types, although the very low frequency of such clones raises questions about whether they are truly clonal (Baroffio et al., 1991). Using vital dye labeling in chick (Bronner-Fraser and Fraser, 1988) and multicolor fluorescent protein expression using genetic recombination in “Confetti” mice (Baggiolini et al., 2015), both premigratory and postmigratory neural crest cells have been found to be multipotent in vivo. However, these studies have been largely limited to trunk neural crest, with the exception of a recent study showing that individual vagal neural crest cells (a population between cranial and trunk) can generate both cardiac mesenchyme and enteric neurons (Tang et al., 2021). In vivo evidence for single CNCCs generating clones of skeletogenic ectomesenchyme and non-ectomesenchyme, in contrast, is lacking. In zebrafish, labeling of CNCCs at early somite stages by injection of GFP RNA (Dorsky et al., 1998) or fluorescent dye (Schilling and Kimmel, 1994) failed to uncover a common progenitor for ectomesenchyme and non-ectomesenchyme lineages. Similar clonal analysis of mouse CNCCs starting at embryonic day (E) 8.5 found no common precursors of ectomesenchyme and neuroglial derivatives (Kaucka et al., 2016).

Whereas trunk neural crest and CNCCs fated to non-ectomesenchyme lineages arise from the early N-cadherin+ neural ectoderm (Bronner-Fraser et al., 1992), a more lateral population of E-cadherin+ non-neural ectoderm has been found to give rise to ectomesenchyme (Breau et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2013b). This finding suggests further similarities of ectomesenchyme to the E-cadherin+ pre-gastrulation ectoderm of the epiblast, with downregulation of cell surface E-cadherin likely contributing to EMT in both (Acloque et al., 2009). This has led James Weston and colleagues to label ectomesenchyme “metablast” which refers to the delayed involution of mesenchyme past the epiblast stage (Weston et al., 2004). It also has been noted that CNCCs destined to form ectomesenchyme are the first to delaminate from the ectodermal epithelium, doing so before the neural folds meet at the midline to form the neural tube (keel in fish) (Nichols, 1986; Piloto and Schilling, 2010; Tan and Morriss-Kay, 1985). In extreme cases, ectomesenchyme formation starts before somitogenesis, such as in marsupials where mandibular arch ectomesenchyme develops especially early to promote precocious jaw development for suckling in the mother’s pouch (Vaglia and Smith, 2003), and in bichir fish where precocious hyoid arch ectomesenchyme formation supports development of prominent external gills (Stundl et al., 2019). One view then is that, at the origins of vertebrates, mechanisms arose in the head that delayed and/or prolonged ingression of mesoderm-like cells from a portion of dorsal epiblast epithelia until neurulation stages, with this new population of ectomesenchyme expanding the pool of mesoderm-like cells for various skeletal and connective tissue fates. The extent of this delay was then fine-tuned in a region- and species-specific manner to allow for local shifts in the timing and likely size of mesoderm-like cell populations important for diverse head innovations.

Rather than consider ectomesenchyme alone as a delayed involution event, it may be more useful to consider all of neural crest formation as delayed involution from epiblast stages. However, in contrast to gastrulation in the epiblast where the dorsal epithelia undergoing EMT and involution is naïve, neural crest EMT would occur in an epithelium that has begun to commit to neural and non-neural fates. Hence, in the cranial and trunk regions where neural crest cells are formed from N-cadherin+ neural ectoderm, involuting mesenchyme would be biased away from a mesoderm fate toward neuroglial fates, in line with contributions to the peripheral nervous system. In contrast, CNCCs forming in more lateral E-cadherin+ non-neural ectoderm regions would progress along a mesoderm-like lineage, much like involuting mesodermal cells in the earlier epiblast. However, there is likely plasticity in these programs, as early- and late-arising CNCCs can equally generate ectomesenchyme and neuroglial derivatives upon heterochronic grafting in avians (Baker et al., 1997). Further evidence for the capacity to prolong gastrulation movements into late neurulation stages comes from the identification of neuromesodermal progenitors (NMPs) in the tail of amniote embryos. Much like cells in the earlier epiblast, NMPs can generate both nervous tissue (spinal cord) and posterior somitic mesoderm driving tail elongation (Kölliker 1884 Tzouanacou et al., 2009). NMPs co-express markers of early neural (Sox2) and mesoderm (T) lineages (Garriock et al., 2015; Olivera-Martinez et al., 2012), as well as markers of the primitive streak, and clonal studies have revealed individual NMPs can be bipotent (Tzouanacou et al., 2009). In addition, recent evidence suggests that NMPs can generate trunk neural crest in the most caudal region of the embryo (Frith et al., 2018). This potential of NMPs is highly reminiscent of the anterior Wnt1-expressing neural plate which can generate central nervous system (analogous to spinal cord), CNCC ectomesenchyme (analogous to tail mesoderm), and CNCC neuroglial derivatives (analogous to trunk neural crest). Similar mechanisms may therefore have evolved to delay gastrulation movements through neurulation stages at both the anterior and posterior poles of the embryo.

2.2. Epigenetic reprogramming during ectomesenchyme specification

If formation of the neural crest, and in particular the ectomesenchyme, can be considered a regionalized form of delayed gastrulation, what molecular mechanisms might account for such a delay? In the early blastula, factors such as Oct4, Sox2, Nanog, Klf4, and others function to maintain pluripotency by inhibiting embryonic germ layer and extra-embryonic fates. The downregulation of pluripotency factors in the epiblast then coincides with onset of the morphogenetic movements that generate mesoderm and other primitive germ layers (Osorno et al., 2012). Intriguingly, a study in frog provided evidence that cells destined to form neural crest selectively maintain the pluripotency network, providing a potential explanation for how these cells resist EMT and gastrulation movements in the epiblast (Buitrago-Delgado et al., 2015). In contrast, subsequent studies in frog and zebrafish combining lineage barcoding with single-cell transcriptome analyses found that, rather than pluripotency being selectively maintained in the neural crest lineage, multipotency is reacquired during emergence of neural crest from the neural plate border (Briggs et al., 2018; Wagner et al., 2018). Broad expression of pluripotency genes, albeit at modest levels, was observed throughout frog and fish embryos, highlighting that these genes play additional roles in development beyond simply maintaining pluripotency. This raises a cautionary note that it is not the expression of these genes per se that defines pluripotency, but their very high levels of concurrent expression, a criticism that can also be brought to claims of pluripotent cells being found in adult tissues (Suszynska et al., 2014).

In contrast to maintenance of a pluripotency program in neural crest precursors, recent work in frog and mouse provides more evidence that a transient and more limited reacquisition of some elements of the pluripotency network underlies ectomesenchyme formation (Scerbo and Monsoro-Burq, 2020; Zalc et al., 2021). After downregulation of pluripotency genes in the epiblast, re-expression of Oct4 and Nanog was seen in nascent CNCCs at early somite stages in mouse. Moreover, the chromatin accessibility landscape of Oct4+ CNCCs closely resembled stem cells isolated from the epiblast, and deletion of Oct4 impeded the ability of CNCCs to form ectomesenchyme but not neuroglial derivatives. Whereas previous studies had shown that Oct4 along with 2–3 other factors can reprogram nearly any cell to a pluripotent state (Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006; Yu et al., 2007), re-expression of Oct4 alone in the early embryo can revert post-epiblast cells to a pluripotent state (Osorno et al., 2012). Early mesoderm formation is also exquisitely sensitive to Oct4 levels (Niwa et al., 2000), and persistence of Oct4 has been linked to prolonged mesodermal potential of NMPs (Aires et al., 2016; Edri et al., 2019). This second wave of Oct4 expression could function to similarly prolong gastrulation-like involution events in the cranial domain, particularly in the non-neural domain giving rise to ectomesenchyme. Transient reactivation of Oct4 and Nanog could also be interpreted as a type of in vivo partial reprogramming to a pluripotent-like state, re-establishing mesoderm potential (i.e. accessibility of mesoderm lineage enhancers) in the post-epiblast ectoderm.

Additional evidence for the role of epigenetic reprogramming during early stages of CNCC ectomesenchyme specification comes from analysis of a dominant variant histone H3.3 mutant in zebrafish (Cox et al., 2012). The dominant-negative D123N mutation effectively blocks loading of replacement histones into chromatin outside of the cell cycle. When replacement histone loading is globally blocked, ectomesenchyme formation is specifically affected, suggesting that formation of ectomesenchyme involves a particularly large-scale histone replacement event. Pluripotency factors such as Oct4 function in large part by remodeling the chromatin landscape (Koche et al., 2011), and loss of Oct4 in mouse CNCCs (Zalc et al., 2021) or the chromatin remodeler CHD7 in in vitro human neural crest-like cells (Bajpai et al., 2010) leads to very similar reductions of CNCC and ectomesenchyme marker expression, and failures of CNCC delamination and migration, as seen in zebrafish histone H3.3 mutants. Together, this suggests that Oct4 and other factors may remodel the chromatin landscape of CNCCs through histone replacement to promote epiblast-like involution movements and mesoderm lineage potential. However, it should be noted that further inhibition of histone replacement in zebrafish, by injecting dominant-negative H3.3 RNA into D123N H3.3 mutants, also affects pigment and neuroglial specification in both cranial and trunk regions (Bryant et al., 2020), suggesting that, while ectomesenchyme is most sensitive to chromatin remodeling defects, neural crest in general may require epigenetic reprogramming during specification.

While epigenetic reprogramming during early somite stages contributes to ectomesenchyme formation, evidence suggests that such reprogramming is pre-patterned much earlier in the epiblast. In the chick, explants taken from particular mediolateral positions of the epiblast can differentiate into neural crest under non-inducing conditions (Basch et al., 2006). Moreover, the histone H3K9 demethylase JmjD2A, which is required for neural crest specification in chick, occupies neural crest regulatory elements from epiblast stages, although it does not appear to remove repressive H3K9 modifications and activate neural crest gene expression until neurulation stages (Strobl-Mazzulla et al., 2010). These findings suggest that the prospective neural crest domain is already set aside in the epiblast, in part through poising of its chromatin landscape, with additional signals at neurulation stages promoting involution movements and mesoderm-like potential.

2.3. Signaling pathways regulating ectomesenchyme formation

While ectomesenchyme and neuroglial CNCCs appear to derive from adjacent yet molecularly distinct mediolateral domains in the neural fold, active signaling also plays a role in specifying ectomesenchyme. While studies in zebrafish did not find a role for Wnt signaling in ectomesenchyme fate (Dorsky et al., 1998), Fgf promotes and Bmp inhibits ectomesenchyme specification. Global inhibition of Fgf signaling during CNCC specification in zebrafish and chick results in loss of expression of Twist1 (a broad marker of ectomesenchyme and paraxial mesoderm, but not neuroglial CNCCs) and Dlx2 (a marker of a subset of ectomesenchyme posterior to the frontonasal domain) (Blentic et al., 2008). Knockdown of fgf20b in zebrafish results in a similar ectomesenchyme defect (Yamauchi et al., 2011). Interestingly, fgf20a mutations prevent formation of a regenerative blastema following zebrafish fin amputation, suggesting that Fgf20 may have more general roles in reprogramming of cells to an uncommitted mesenchyme fate (Whitehead et al., 2005). Reciprocally, overactivation of Bmp signaling in zebrafish CNCCs results in loss of ectomesenchyme and expression of twist1a and twist1b but not dlx2a, in part through upregulation of the transcriptional repressor Id2a (Das and Crump, 2012). In wild type, sox10 and foxd3 expression marks early CNCC and then is downregulated in migrating ectomesenchyme (Blentic et al., 2008; Das and Crump, 2012), reflective of later non-ectomesenchyme roles of sox10 and foxd3 in CNCC pigment and glial specification, respectively (Dutton et al., 2001; Thomas and Erickson, 2009). When Twist1 is mutated in mouse or fish, Fgf signaling inhibited, or Bmp signaling upregulated, Sox10 expression abnormally perdures in arch CNCCs, reflecting either a block in CNCC to ectomesenchyme progression and/or trans-fating to non-ectomesenchymal fates (Bildsoe et al., 2009; Blentic et al., 2008; Das and Crump, 2012). Similar sox10 and foxd3 upregulation and ectomesenchyme loss is seen upon reduced function of zebrafish disc1, which encodes a signaling scaffold protein whose homolog is linked to schizophrenia susceptibility in humans (Drerup et al., 2009). An open question is how Fgf and Bmp signaling, as well as Disc1, relate to the recently discovered epigenetic reprogramming underlying ectomesenchyme potential in CNCCs.

3. Diversity of Ectomesenchyme Derivatives

3.1. Identification and lineage tracing of CNCC ectomesenchyme

While identification of CNCCs as the source of head ectomesenchyme dates to the 19th century, their history has been fraught with acrimonious debate (reviewed by (Hall 2008; Hörstadius 1950), and others). Neural crest cells were first discovered by direct observation of developing chicken embryos. Wilhlem His, a Swiss biologist and inventor of the microtome, named these “Zwichenstrang” meaning a cell layer between the skin and neural tube (His, 1868). Contribution of CNCCs to head mesenchyme was then described by Kastschenko in amphibians (Kastschenko, 1888) and by Goronowitch in teleost fish and avians (Goronowitsch, 1892). In 1893, Julia Platt provided the first evidence that neural crest can contribute to skeletal tissues, in particular facial cartilage. She exploited the fact that ectodermal cells of amphibians have almost no yolk granules, in contrast to the yolk-rich endoderm and mesoderm derived tissues. The lack of yolk granules in facial cartilage cells thus pointed to an ectodermal origin of such mesenchyme, which she termed “mesectoderm” (Platt, 1893) - later rebranded “ectomesenchyme” (de Beer, 1947). These findings remained, however, highly contentious, as they appeared to violate the prevalent germ layer theory of the time in which mesoderm was the sole source of mesenchyme.

Interest in ectomesenchyme made a resurgence shortly after the first world war. Stone performed the first extirpation experiments, showing that removing portions of the head neural folds resulted in loss of craniofacial skeletal structures (Stone, 1922). Vogt then introduced in vivo labeling, incorporating small agarose chips soaked by vital dyes onto neural crest cells and showing their contributions to arch mesenchyme (Vogt, 1929). Raven performed grafting experiments, taking advantage of the different nuclear size of cells from two different amphibian species (Amblystoma and Triturus). By grafting head neural folds between these species, he validated contribution of ectodermal cells to head mesenchymal tissues (Raven, 1931). These techniques were further refined by Horstadius and Sellamn (Hörstadius, 1950; Hörstadius and Sellman, 1941; Hörstadius and Sellman, 1946), who showed that CNCCs are the major source of craniofacial mesenchymal tissues. Starting in the 1960s, Chibon and Weston used radioactive labeling and grafting in avians to expand our knowledge of ectomesenchyme potential (Chibon, 1964; Weston, 1963). Following the strategy employed by Raven in the 1930s on amphibians, Nicole Le Douarin and colleagues developed inter-species avian grafting techniques, based on the prominent nucleolus of quail versus chicken cells and later a quail-specific QCPN antibody, to create catalogs of ectomesenchyme derivatives (Le Douarin, 1969; Le Douarin, 1971).

The last few decades have seen spectacular advances in the precision of neural crest lineage tracing experiments. In 1988, Bronner and Fraser pioneered single-cell labeling of avian neural crest cells, combining fluorescent dye injection with advances in microscopy, although trunk and not cranial neural crest was studied (Bronner-Fraser and Fraser, 1988). Single-cell tracing by injection of fluorescent dye or GFP RNA definitively confirmed facial skeletal contributions of CNCCs in zebrafish, and, as mentioned previously, early segregation of ectomesenchyme and non-ectomesenchyme lineages (Dorsky et al., 1998; Schilling and Kimmel, 1994). Genetic recombination experiments in the new millennium allowed indelible tracing of the neural crest lineage, in particular using the Wnt1:Cre mouse line that labels the early neural folds from which CNCCs arise (Chai et al., 2000), and subsequently more specific lines to mark CNCCs (Sox10:Cre) and post-migratory ectomesenchyme (P0:Cre) (Bildsoe et al., 2009). Similar genetic recombination-based lineage tracing (based largely on sox10 and crestin transgenes) has been performed in zebrafish (Kague et al., 2012; Mongera et al., 2013). Cre-based recombination has also been combined with multi-color reporters (“Confetti”) to perform clonal analysis of ectomesenchyme lineages (Baggiolini et al., 2015), and cellular barcoding to reveal cell relatedness in the early ectomesenchyme and its convergence on a mesoderm-like transcriptional state (Wagner et al., 2018). Recently, our group has used Cre-based lineage tracing and single-cell transcriptome and chromatin accessibility analyses to comprehensively describe the ontogeny of ectomesenchyme from embryonic to adult stages in zebrafish (Fabian et al., 2022).

3.2. Diversity of ectomesenchyme derivatives

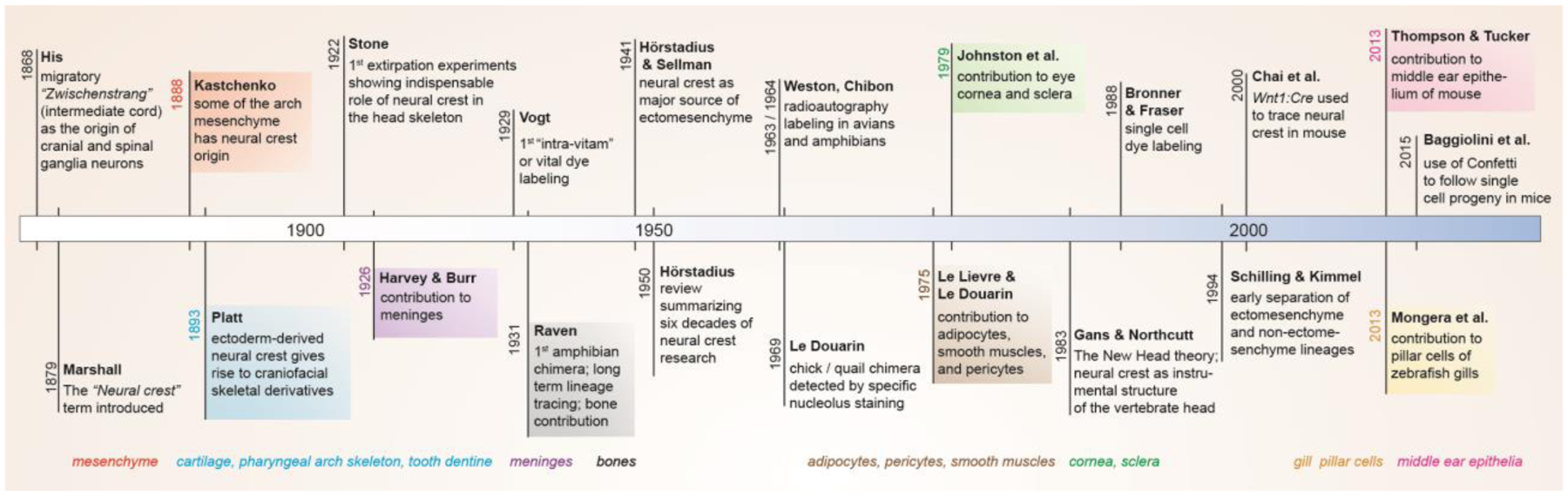

The first ectomesenchyme derivatives were identified in easily accessible amphibian embryos and consisted of the three main head skeletal types: cartilage and tooth mesenchyme (Platt, 1893) and later bone (Raven, 1931). Harvey and Burr described contributions to the meninges, connective tissue that nurtures the brain (Harvey and Burr, 1926), and Johnston identified contributions to the endothelium and stroma of the cornea (Johnston, 1966). Work in avian models, particularly from the lab of Le Douarin, identified many other ectomesenchyme derivatives, including adipocytes, pericytes, and smooth muscles (Le Lievre and Le Douarin, 1975). CNCC contributions to the craniofacial skeleton and other mesenchymal cell types has been confirmed in many other species using multiple types of methods. While we provide a timeline of the discovery of major ectomesenchyme derivatives in Figure 2, more complete lists of ectomesenchyme derivatives are reviewed elsewhere (e.g. (Hall, 2008)).

Figure 2. Timeline of ectomesenchyme research.

Major discoveries in neural crest and ectomesenchyme research are listed along the timeline, with the identification of major ectomesenchyme derivatives at bottom.

Recent genetic recombination experiments are also revealing some unexpected, species-specific cell types derived from ectomesenchyme. In zebrafish, ectomesenchyme has been shown to generate pillar cells, a specialized type of endothelial cell in the gill filaments of fish (Fabian et al., 2022; Mongera et al., 2013). In mouse, ectomesenchyme generates a portion of the middle ear epithelium, previously thought to be exclusively derived from endoderm; similar middle ear epithelial contributions do not occur in avians (Thompson and Tucker, 2013). Contributions of ectomesenchyme to corneal endothelium, gill pillar endothelial cells, and middle ear epithelium represent interesting examples of CNCC mesenchyme to epithelial transitions. This suggests a greater plasticity of CNCCs than previously appreciated, with CNCCs able to adopt cell fates in common with all three germ layers. While contributions of CNCCs to mesenchyme of the cardiac outflow tract and second heart field are well documented (Kirby et al., 1983; Waldo et al., 1999), there have also been conflicting reports of CNCCs generating cardiomyocytes. One study reported CNCC contributions to cardiomyocytes under homeostatic conditions in zebrafish (Mongera et al., 2013), yet another study claimed contributions to cardiomyocytes in amniotes but only during regeneration in zebrafish (Tang et al., 2019).

It is important to note that all of the techniques used to study ectomesenchyme potential suffer from their own limitations. In grafting and extirpation experiments, it is hard to rule out whether other non-CNCC tissues have been transferred or removed. In dye labeling experiments, it is possible for labeled cells to die and become phagocytosed by neighboring cells, and dilution of dye limits long-term tracing. Genetic recombination lineage tracing is heavily dependent on the specificity of the Cre lines, even in cases where temporal activity of Cre is controlled by fusion to the estrogen receptor. There may also be species-specific differences in CNCC contributions, as shown for the middle ear epithelium (Thompson and Tucker, 2013) and possibly cardiomyocytes (Tang et al., 2019), and thus caution should be used when extrapolating results from one species to another. As elegantly laid out by de Beer in his studies of ectomesenchyme (de Beer, 1947), it may be more appropriate to consider germ layers, including the neural crest, as mechanisms to distribute cells in the embryo rather than determinants of cell fate, with differences in embryonic geometries correlating with species-specific differences in ectomesenchyme contributions.

4. Reassessing the Unique Potential of the Cranial Neural Crest

4.1. Contributions of trunk neural crest to mesenchymal derivatives

A central tenet of neural crest biology is that cranial, and to a certain extent vagal, regions have ectomesenchyme potential, yet trunk regions do not. Yet there has been speculation about whether the trunk crest of ancestral vertebrates, or even some extant vertebrates, have ectomesenchyme potential. Whereas most terrestrial vertebrates have dermal bone and tooth dentine only in their heads, with these tissues largely derived from CNCCs, most extant fish have dermal bone along their bodies in the form of scales and bony fin rays. Further, the fossil fish group of ostracoderms have extensive body armor composed of dermal bone and dentine tissue in the absence of a presumably mesoderm-derived endochondral skeleton (Vickaryous and Sire, 2009). Although initial reports using dye labeling in zebrafish (Smith et al., 1994) and HNK-1 antibody staining in swordtail (Hirata et al., 1997) claimed contributions of trunk crest to dorsal fin bone, more definitive genetic lineage tracing techniques showed no trunk crest contributions to dorsal fin mesenchyme in either zebrafish (Lee et al., 2013a) or medaka (Shimada et al., 2013). Other reports describe a potential trunk crest origin of osteogenic mesenchyme in the dermal plastron skeleton of turtles (Cebra-Thomas et al., 2013) and dermal denticles of skates (Gillis et al., 2017). However, these findings were largely based on dye labeling of trunk crest, as in the initial zebrafish fin lineage studies, and thus await further confirmation.

In mouse, several groups have used neuroepithelial Cre (Sox1:Cre, Wnt1:Cre) and postmigratory neural crest Cre (P0:Cre) lines to drive permanent genetic recombination and labeling of trunk crest. Using Sox1:Cre and P0:Cre, it was found that trunk crest supplies a very small amount of bone marrow mesenchymal cells that disappears by adult stages (Takashima et al., 2007), though a separate study using Wnt1:Cre and P0:Cre did reveal some contributions to adult bone marrow mesenchyme (Morikawa et al., 2009; Nagoshi et al., 2008). A later study using Wnt1:Cre2, a newer version lacking the ectopic Wnt1 expression of the original Wnt1:Cre (Lewis et al., 2013), found contribution of labeled cells to articular chondrocytes and osteoblasts/osteocytes of the mouse femur (Isern et al., 2014). A caveat to all these studies is that constitutive Cre lines were utilized, and hence recombination in cell types beyond the neural crest cannot be ruled out. Indeed, neuroepithelial labeling by Sox1:Cre and Wnt1:Cre may also label the NMPs that generate trunk mesoderm and neural crest in the trunk (Frith et al., 2018; Tzouanacou et al., 2009). Nonetheless, contributions of trunk neural crest to limited amounts of mesenchyme may reflect plasticity of this cell population. Consistently, precursors of Schwann cells, a type of glial cell derived from both cranial and trunk neural crest, have been suggested to give rise to tooth mesenchyme in mouse (Kaukua et al., 2014) and chondrocytes in mouse and zebrafish (Xie et al., 2019).

To test whether the relative lack of ectomesenchyme potential of trunk neural crest reflects an intrinsic difference to CNCCs, versus the lack of proper inductive signals, several studies have examined the ability of trunk crest to form ectomesenchyme derivatives when transplanted into cranial regions. When segments of the avian trunk neural folds are grafted to replace cranial neural fold regions, neural crest cells do not migrate properly to the pharyngeal arches and fail to form skeletal and connective tissues (Nakamura and Ayer-le Lievre, 1982). However, when trunk neural fold fragments are mixed with cranial neural fragments (Nakamura and Ayer-le Lievre, 1982) or injected directly into the maxillary and mandibular arches (McGonnell and Graham, 2002), trunk crest can contribute to skeletal elements. In addition, misexpression of Sox8, Tfap2b, and Ets1 – factors selectively expressed in cranial versus trunk crest of avians – causes isolated trunk neural fold regions to contribute to chondrocytes upon cranial grafting (Simoes-Costa and Bronner, 2016). These experiments show that trunk crest has considerable plasticity in forming ectomesenchyme fates when placed in the right environment, and that this ectomesenchyme potential can be further enhanced by forced misexpression of cranial-specific factors. Thus, both extrinsic and intrinsic cues likely contribute to the selective ectomesenchyme potential of CNCCs.

4.2. Interchangeability of ectomesenchyme and mesoderm in head skeletal structures

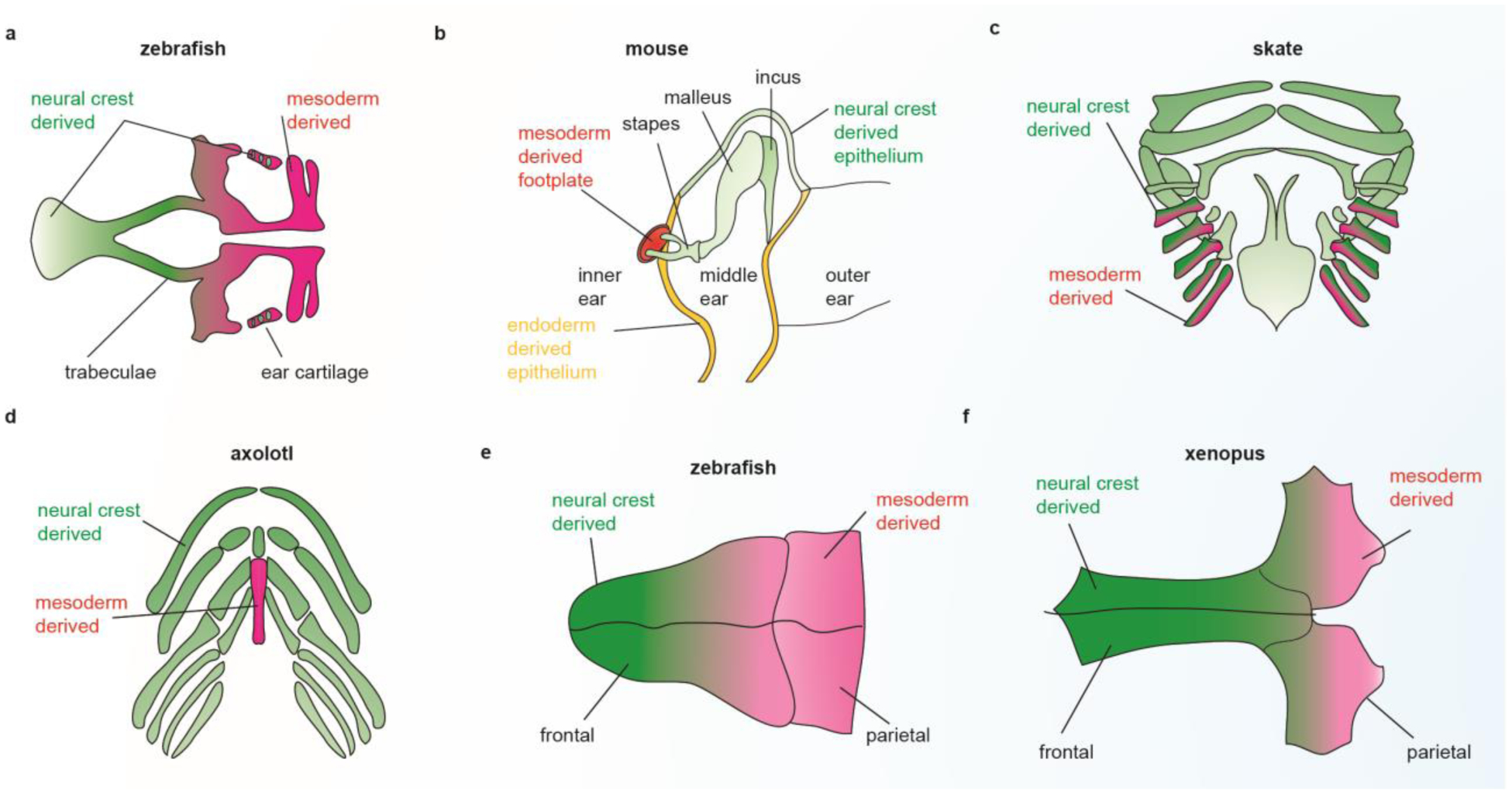

Given the possibility that ectomesenchyme formation represents a delayed form of the gastrulation movements that form mesoderm, it is perhaps not surprising that ectomesenchyme and mesoderm generate similar ranges of cell types. A salient illustration of this is the presence of diverse craniofacial skeletal elements with dual ectomesenchyme and mesoderm origin (Figure 3). The otic cartilages and neurocranium of zebrafish are a seamless mixture of chondrocytes of neural crest and mesoderm origin (Kague et al., 2012; Schilling and Kimmel, 1994). In mammals, the stirrup of the stapes is neural crest-derived and the footplate is mesoderm-derived (Thompson et al., 2012), and the homologous columella of birds has been proposed to have a similar dual origin (Smith, 1904). Whereas in mice the frontal bone of the skullcap is wholly neural crest-derived and the parietal bone wholly mesoderm-derived (Jiang et al., 2002), the frontal bone of zebrafish (Kague et al., 2012) and chick (Evans and Noden, 2006) is dual neural crest and mesoderm origin, as is the parietal bone of Xenopus laevis (Piekarski et al., 2014). Indeed, there appears to be extensive plasticity in the ability of neural crest and mesoderm to contribute to the different skull bones across vertebrate evolution (reviewed in (Teng et al., 2019)). Moreover, the master cartilage transcription factor Sox9 has been shown to engage a very similar set of enhancers in the mesoderm-derived rib and crest-derived nasal cartilages, arguing against germ layer origin having a major influence on mechanisms of skeletogenic differentiation (Ohba et al., 2015).

Figure 3. Interchangeability of neural crest with other germ layers.

Neural crest and mesoderm make dual contributions to the zebrafish neurocranial cartilages (a), the stapes of the mammalian middle ear (b), the gill cartilages of skate (c), the basibranchial cartilages of axolotl (d, mesoderm-derived basibranchial 2 is shown in red below the neural crest-derived basibranchial 1), the frontal bone of zebrafish (e), and the parietal bone of Xenopus laevis (f). Neural crest and endoderm also make dual contributions to middle ear epithelia of mouse (b).

Although extensive mixing of neural crest and mesoderm cells in the cranial and otic skeletons occurs, the pharyngeal arch-derived jaw, hyoid, and gill skeletons have been thought to be entirely crest-derived. However, mesodermal contributions to the gill cartilages have been described in skate (Sleight and Gillis, 2020), as well as mesodermal contributions to the second basibranchial cartilage (which connects gills cartilages at the midline) in amphibians (Davidian and Malashichev, 2013; Sefton et al., 2015; Stone, 1926). These findings have implications for potential deep homology between the pharyngeal arch-derived jaw and gill skeletons and the mesoderm-derived appendages (fins and limbs) (Shubin et al., 2009). In 1878, Gegenbaur first proposed that the pharyngeal arches and limbs were serially homologous (Gegenbaur et al., 1878), though his theory quickly fell out of favor upon recognition of the arch skeleton being crest-derived and the limb skeleton mesoderm-derived. Nonetheless, extensive molecular similarities have recently been noted between patterning of the arches and limbs (Gillis et al., 2009; Gillis and Hall, 2016). While it would be easy to dismiss these similarities as co-option of a limited number of core developmental signaling pathways, increasing evidence for interchangeability of ectomesenchyme and mesoderm, and newfound consideration of ectomesenchyme as merely “delayed mesoderm” warrant re-evaluation of whether appendages arose as modifications of an ancestral and more extensive series of pharyngeal arch-like structures.

Plasticity of ectomesenchyme is not limited to skeletal contributions. Ectomesenchyme contributes to specialized vascular endothelial cells in the gills (pillar cells) that seamlessly integrate with larger diameter mesoderm-derived vessels in the primary gill filaments of fish (Mongera et al., 2013). In the mammalian middle ear, ectomesenchyme and endoderm both contribute to epithelia lining the cavity, although in this case only the endoderm-derived epithelium has motile cilia (Thompson and Tucker, 2013). Analogously, a dual ectoderm and endoderm origin has been described for amphibian teeth (Soukup et al., 2008) and the zebrafish pituitary (Fabian et al., 2020). These findings solidify conclusions made by de Beer working on the ectomesenchyme (de Beer, 1947) that the germ layers are not strict determinants of cell fate, but rather represent embryonic morphogenetic programs that position cells in proximity to appropriate inductive cues.

4.3. Do ectomesenchyme-derived tissues have enhanced repair capacity

Given the striking multipotency of the embryonic neural crest, there has been speculation that the neural crest-derived skeleton may utilize some memory of this multipotency to undergo better repair than the mesoderm-derived skeleton. In mice, it has been reported that the crest-derived frontal bone heals more effectively than the mesoderm-derived parietal bone (Quarto et al., 2010). It is unclear, however, whether this reflects a difference of germ layer origin versus distinct environments of these bones. It will be important to test whether these crest versus mesoderm differences are generalizable to other bones, as well as whether healing differs in species where part of the frontal bone is mesoderm-derived (e.g. zebrafish, (Kague et al., 2012)) or the parietal bone crest-derived (e.g. Xenopus, (Piekarski et al., 2014)). Indeed, whereas the neural crest-derived mandible has been found to spontaneously regenerate in adolescent humans (Okoturo et al., 2016), the mesoderm-derived rib also has remarkable regenerative capacity in humans and mice (Kuwahara et al., 2019; Srour et al., 2015).

Another issue of debate is whether a population of multipotent neural crest cells is maintained through adult stages, where it could participate in repair. Such “neural crest stem cells” have been claimed to reside in diverse adult tissues, including teeth, skin, bone marrow, and heart (reviewed in (Achilleos and Trainor, 2012)). In many cases, similar adult stem/progenitor cells are derived from the mesoderm, suggesting that these represent tissue-specific stem cells rather than remnants of embryonic neural crest progenitors. Indeed, expression of early neural crest markers such as Sox10 and Foxd3 are turned off during ectomesenchyme migration, with a failure of these early crest markers to shut down associated with ectomesenchyme defects (Bildsoe et al., 2009; Das and Crump, 2012; Drerup et al., 2009). Mechanistically, downregulation of Wnt signaling and loss of Lin28a expression has been shown to result in extinguishment of multipotency shortly after CNCC specification (Bhattacharya et al., 2018). These findings argue against long-term maintenance of a multipotent neural crest stem cell past embryonic stages.

Alternatively, study of a distraction osteogenesis model in the mouse mandible led to suggestions that adult cells can reacquire an embryonic neural crest-like state in response to bone injury. While these injury-responsive cells expressed a number of genes in common with neural crest, as well as a similar chromatin landscape, it remains to be determined how their fate potential compares to bona fide embryonic CNCCs (Ransom et al., 2018). Indeed, many genes expressed in the early neural crest have broad roles in embryonic development and injury response. For example, Sox9-expressing cells promote regeneration of the mammalian kidney (Kumar et al., 2015), liver (Furuyama et al., 2011), lung (Chen et al., 2021), and rib (Kuwahara et al., 2019), and Foxd3 has well known roles in embryonic stem cell pluripotency (Hanna et al., 2002). Thus, as with reports of embryonic-like pluripotent stem cells in adult tissues, caution should be taken when using expression of select markers to argue for presence of embryonic-like multipotent neural crest cells in adult tissues.

6. Conclusions and future perspectives

Reflective of its long contentious history, important questions about the developmental origin and full potential of ectomesenchyme remain. Can formation of ectomesenchyme, and even neural crest in general, be considered simply a delayed form of gastrulation, or does it reflect emergence of an entirely new vertebrate cell population through co-option of ancestral morphogenetic programs? In the former, how would delay and exposure to local differentiating tissues such as the neural tube influence the migratory mesenchyme that is formed? Is ectomesenchyme endowed with particularly broad multilineage potential during specification, or is it rather a naïve cell population with the ability to form diverse cell types, and intermix with other germ layers, when presented with the right external signals? Are there still more surprises to come in terms of ectomesenchyme derivatives, especially in the many non-model organisms in which neural crest fate has not been studied? We are entering a new era of single-cell genomics and gene editing, where complete vertebrate cell atlases and even organismal lineages can be reconstructed using deep sequencing, barcoding, imaging, and other approaches. A wholistic view of the early lineage relationships of the precursors for ectomesenchyme versus other neural crest derivatives, as well as complete descriptions of all ectomesenchyme-derived cell types across a range of vertebrates, may soon be within reach.

Highlights.

Cranial neural crest provides a vertebrate-specific source of head mesenchyme

Epigenetic reprogramming facilitates mesenchyme potential of neural crest

Region- and species-specific contributions of ectomesenchyme to diverse cell types

Plasticity of neural crest and mesoderm to contribute to craniofacial mesenchyme

Unclear potential of cranial neural crest cells for enhanced skeletal repair

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by NIDCR R35 DE027550 to J.G.C. and NIDCR K99 DE029858 to P.F.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Achilleos A and Trainor PA (2012). Neural crest stem cells: discovery, properties and potential for therapy. Cell Res 22, 288–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acloque H, Adams MS, Fishwick K, Bronner-Fraser M and Nieto MA (2009). Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: the importance of changing cell state in development and disease. J Clin Invest 119, 1438–1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aires R, Jurberg AD, Leal F, Novoa A, Cohn MJ and Mallo M (2016). Oct4 Is a Key Regulator of Vertebrate Trunk Length Diversity. Dev Cell 38, 262–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggiolini A, Varum S, Mateos JM, Bettosini D, John N, Bonalli M, Ziegler U, Dimou L, Clevers H, Furrer R, et al. (2015). Premigratory and migratory neural crest cells are multipotent in vivo. Cell Stem Cell 16, 314–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajpai R, Chen DA, Rada-Iglesias A, Zhang J, Xiong Y, Helms J, Chang CP, Zhao Y, Swigut T and Wysocka J (2010). CHD7 cooperates with PBAF to control multipotent neural crest formation. Nature 463, 958–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker CV, Bronner-Fraser M, Le Douarin NM and Teillet MA (1997). Early- and late-migrating cranial neural crest cell populations have equivalent developmental potential in vivo. Development 124, 3077–3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baroffio A, Dupin E and Le Douarin NM (1991). Common precursors for neural and mesectodermal derivatives in the cephalic neural crest. Development 112, 301–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basch ML, Bronner-Fraser M and Garcia-Castro MI (2006). Specification of the neural crest occurs during gastrulation and requires Pax7. Nature 441, 218–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya D, Rothstein M, Azambuja AP and Simoes-Costa M (2018). Control of neural crest multipotency by Wnt signaling and the Lin28/let-7 axis. Elife 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bildsoe H, Loebel DA, Jones VJ, Chen YT, Behringer RR and Tam PP (2009). Requirement for Twist1 in frontonasal and skull vault development in the mouse embryo. Dev Biol 331, 176–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blentic A, Tandon P, Payton S, Walshe J, Carney T, Kelsh RN, Mason I and Graham A (2008). The emergence of ectomesenchyme. Dev Dyn 237, 592–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breau MA, Pietri T, Stemmler MP, Thiery JP and Weston JA (2008). A nonneural epithelial domain of embryonic cranial neural folds gives rise to ectomesenchyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 7750–7755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs JA, Weinreb C, Wagner DE, Megason S, Peshkin L, Kirschner MW and Klein AM (2018). The dynamics of gene expression in vertebrate embryogenesis at single-cell resolution. Science 360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronner-Fraser M and Fraser SE (1988). Cell lineage analysis reveals multipotency of some avian neural crest cells. Nature 335, 161–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronner-Fraser M, Wolf JJ and Murray BA (1992). Effects of antibodies against N-cadherin and N-CAM on the cranial neural crest and neural tube. Dev Biol 153, 291–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant L, Li D, Cox SG, Marchione D, Joiner EF, Wilson K, Janssen K, Lee P, March ME, Nair D, et al. (2020). Histone H3.3 beyond cancer: Germline mutations in Histone 3 Family 3A and 3B cause a previously unidentified neurodegenerative disorder in 46 patients. Sci Adv 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buitrago-Delgado E, Nordin K, Rao A, Geary L and LaBonne C (2015). Shared regulatory programs suggest retention of blastula-stage potential in neural crest cells. Science 348, 1332–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cebra-Thomas JA, Terrell A, Branyan K, Shah S, Rice R, Gyi L, Yin M, Hu Y, Mangat G, Simonet J, et al. (2013). Late-emigrating trunk neural crest cells in turtle embryos generate an osteogenic ectomesenchyme in the plastron. Dev Dyn 242, 1223–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai Y, Jiang X, Ito Y, Bringas P, Han J, Rowitch DH, Soriano P, McMahon AP and Sucov HM (2000). Fate of the mammalian cranial neural crest during tooth and mandibular morphogenesis. Development 127, 1671–1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Li K, Zhong X, Wang G, Wang X, Cheng M, Chen J, Chen Z, Chen J, Zhang C, et al. (2021). Sox9-expressing cells promote regeneration after radiation-induced lung injury via the PI3K/AKT pathway. Stem Cell Res Ther 12, 381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZF and Behringer RR (1995). twist is required in head mesenchyme for cranial neural tube morphogenesis. Genes Dev 9, 686–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chibon P (1964). Analyse par la méthode de marquage nucléaire à la thymidine tritiée des dérivés de la crête neurale céphalique chez l’Urodèle Pleurodeles waltii. pp. 3624 – 3627: C R Acad. Sci, Paris. [Google Scholar]

- Cox SG, Kim H, Garnett AT, Medeiros DM, An W and Crump JG (2012). An essential role of variant histone H3.3 for ectomesenchyme potential of the cranial neural crest. PLoS Genet 8, e1002938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das A and Crump JG (2012). Bmps and id2a act upstream of Twist1 to restrict ectomesenchyme potential of the cranial neural crest. PLoS Genet 8, e1002710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidian A and Malashichev Y (2013). Dual embryonic origin of the hyobranchial apparatus in the Mexican axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum). Int J Dev Biol 57, 821–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Beer GR (1947). The differentiation of neural crest cells into visceral cartilages and odontoblasts in Amblystoma, and a reexamination of the germ-layer theory. Proc. R. Soc. London B134, 377–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsky RI, Moon RT and Raible DW (1998). Control of neural crest cell fate by the Wnt signalling pathway. Nature 396, 370–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drerup CM, Wiora HM, Topczewski J and Morris JA (2009). Disc1 regulates foxd3 and sox10 expression, affecting neural crest migration and differentiation. Development 136, 2623–2632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton KA, Pauliny A, Lopes SS, Elworthy S, Carney TJ, Rauch J, Geisler R, Haffter P and Kelsh RN (2001). Zebrafish colourless encodes sox10 and specifies non-ectomesenchymal neural crest fates. Development 128, 4113–4125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edri S, Hayward P, Baillie-Johnson P, Steventon BJ and Martinez Arias A (2019). An epiblast stem cell-derived multipotent progenitor population for axial extension. Development 146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DJ and Noden DM (2006). Spatial relations between avian craniofacial neural crest and paraxial mesoderm cells. Dev Dyn 235, 1310–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian P, Tseng KC, Smeeton J, Lancman JJ, Dong PDS, Cerny R and Crump JG (2020). Lineage analysis reveals an endodermal contribution to the vertebrate pituitary. Science 370, 463–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian P, Tseng KC, Thiruppathy M, Arata C, Chen HJ, Smeeton J, Nelson N and Crump JG (2022). Lifelong single-cell profiling of cranial neural crest diversification in zebrafish. Nat Commun 13, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith TJ, Granata I, Wind M, Stout E, Thompson O, Neumann K, Stavish D, Heath PR, Ortmann D, Hackland JO, et al. (2018). Human axial progenitors generate trunk neural crest cells in vitro. Elife 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuyama K, Kawaguchi Y, Akiyama H, Horiguchi M, Kodama S, Kuhara T, Hosokawa S, Elbahrawy A, Soeda T, Koizumi M, et al. (2011). Continuous cell supply from a Sox9-expressing progenitor zone in adult liver, exocrine pancreas and intestine. Nat Genet 43, 34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gans C and Northcutt RG (1983). Neural crest and the origin of vertebrates: a new head. Science 220, 268–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Castro MI, Marcelle C and Bronner-Fraser M (2002). Ectodermal Wnt function as a neural crest inducer. Science 297, 848–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garriock RJ, Chalamalasetty RB, Kennedy MW, Canizales LC, Lewandoski M and Yamaguchi TP (2015). Lineage tracing of neuromesodermal progenitors reveals novel Wnt-dependent roles in trunk progenitor cell maintenance and differentiation. Development 142, 1628–1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gegenbaur C, Bell FJ and Lankester ER (1878). Elements of comparative anatomy. London,: Macmillan and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Gillis JA, Alsema EC and Criswell KE (2017). Trunk neural crest origin of dermal denticles in a cartilaginous fish. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, 13200–13205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis JA, Dahn RD and Shubin NH (2009). Shared developmental mechanisms pattern the vertebrate gill arch and paired fin skeletons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 5720–5724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis JA and Hall BK (2016). A shared role for sonic hedgehog signalling in patterning chondrichthyan gill arch appendages and tetrapod limbs. Development 143, 1313–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goronowitsch (1892). Die axiale und die laterale Kopfmetameric der Vögelembryonen. Die Rolle der sog. ‘Ganglienleisten’ im Aufbaue der Nervenstämme. pp. 454 – 464: Anat. Anz [Google Scholar]

- Hall BK (2008). The neural crest and neural crest cells: discovery and significance for theories of embryonic organization. J Biosci 33, 781–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna LA, Foreman RK, Tarasenko IA, Kessler DS and Labosky PA (2002). Requirement for Foxd3 in maintaining pluripotent cells of the early mouse embryo. Genes Dev 16, 2650–2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey SC and Burr HS (1926). The development of the meninges. pp. 545: Archives of Neurology And Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Hirata M, Ito K and Tsuneki K (1997). Migration and Colonization Patterns of HNK-1-Immunoreactive Neural Crest Cells in Lamprey and Swordtail Embryos. Zoological Science 14, 305–312. [Google Scholar]

- His W (1868). Untersuchungen über die erste Anlage des Wirbeltierleibes: die erste Entwicklung des Hühnchens im Ei: F.C.W. Vogel, Leipzig. [Google Scholar]

- Hörstadius SO (1950). The neural crest; its properties and derivatives in the light of experimental research. London, New York,: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hörstadius S and Sellman S (1941). Experimental studies on the determination of the chondrocranium in Amblystoma mexicanum. Ark. Zool 3 33A, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- ---- (1946). Experimentelle Untersuchungen über die determination des Knorpeligen Kopfskelettes bei Urodelen. pp. 1 – 170: Nova Acta Soc. Sci. Uppsaliensis Ser [Google Scholar]

- Isern J, Garcia-Garcia A, Martin AM, Arranz L, Martin-Perez D, Torroja C, Sanchez-Cabo F and Mendez-Ferrer S (2014). The neural crest is a source of mesenchymal stem cells with specialized hematopoietic stem cell niche function. Elife 3, e03696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Iseki S, Maxson RE, Sucov HM and Morriss-Kay GM (2002). Tissue origins and interactions in the mammalian skull vault. Dev Biol 241, 106–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston MC (1966). A radioautographic study of the migration and fate of cranial neural crest cells in the chick embryo. Anat Rec 156, 143–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kague E, Gallagher M, Burke S, Parsons M, Franz-Odendaal T and Fisher S (2012). Skeletogenic fate of zebrafish cranial and trunk neural crest. PLoS One 7, e47394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastschenko N (1888). Zur Entwicklungsgeschichte des Selachierembryos. Anat. Anz 3, 445–467. [Google Scholar]

- Kaucka M, Ivashkin E, Gyllborg D, Zikmund T, Tesarova M, Kaiser J, Xie M, Petersen J, Pachnis V, Nicolis SK, et al. (2016). Analysis of neural crest-derived clones reveals novel aspects of facial development. Sci Adv 2, e1600060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaukua N, Shahidi MK, Konstantinidou C, Dyachuk V, Kaucka M, Furlan A, An Z, Wang L, Hultman I, Ahrlund-Richter L, et al. (2014). Glial origin of mesenchymal stem cells in a tooth model system. Nature 513, 551–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby ML, Gale TF and Stewart DE (1983). Neural crest cells contribute to normal aorticopulmonary septation. Science 220, 1059–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koche RP, Smith ZD, Adli M, Gu H, Ku M, Gnirke A, Bernstein BE and Meissner A (2011). Reprogramming factor expression initiates widespread targeted chromatin remodeling. Cell Stem Cell 8, 96–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kölliker A (1884). Die embryonalen keimblätter und die gewebe. Leipzig,. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Liu J, Pang P, Krautzberger AM, Reginensi A, Akiyama H, Schedl A, Humphreys BD and McMahon AP (2015). Sox9 Activation Highlights a Cellular Pathway of Renal Repair in the Acutely Injured Mammalian Kidney. Cell Rep 12, 1325–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwahara ST, Serowoky MA, Vakhshori V, Tripuraneni N, Hegde NV, Lieberman JR, Crump JG and Mariani FV (2019). Sox9+ messenger cells orchestrate large-scale skeletal regeneration in the mammalian rib. Elife 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landacre FL (1921). The fate of the neural crest in the head of the Urodeles. J. Comp. Neurol 33, 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lankester ER (1873). On the primitive cell-layers of the embryo as the basis of genealogical classification of animals, and on the origin of vascular and lymph systems. Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. Series 4 11, 321–338. [Google Scholar]

- Le Douarin N (1969). Details of the interphase nucleus in Japanese quail (Coturnix coturnix japonica). Bull Biol Fr Belg 103, 435–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ---- (1971). The structure of the interphasic nucleus in various species of birds. C R Acad Hebd Seances Acad Sci D 272, 1402–1404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Lievre CS and Le Douarin NM (1975). Mesenchymal derivatives of the neural crest: analysis of chimaeric quail and chick embryos. J Embryol Exp Morphol 34, 125–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RT, Knapik EW, Thiery JP and Carney TJ (2013a). An exclusively mesodermal origin of fin mesenchyme demonstrates that zebrafish trunk neural crest does not generate ectomesenchyme. Development 140, 2923–2932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RT, Nagai H, Nakaya Y, Sheng G, Trainor PA, Weston JA and Thiery JP (2013b). Cell delamination in the mesencephalic neural fold and its implication for the origin of ectomesenchyme. Development 140, 4890–4902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis AE, Vasudevan HN, O'Neill AK, Soriano P and Bush JO (2013). The widely used Wnt1-Cre transgene causes developmental phenotypes by ectopic activation of Wnt signaling. Dev Biol 379, 229–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGonnell IM and Graham A (2002). Trunk neural crest has skeletogenic potential. Curr Biol 12, 767–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mongera A, Singh AP, Levesque MP, Chen YY, Konstantinidis P and Nusslein-Volhard C (2013). Genetic lineage labeling in zebrafish uncovers novel neural crest contributions to the head, including gill pillar cells. Development 140, 916–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsoro-Burq AH, Fletcher RB and Harland RM (2003). Neural crest induction by paraxial mesoderm in Xenopus embryos requires FGF signals. Development 130, 3111–3124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa S, Mabuchi Y, Niibe K, Suzuki S, Nagoshi N, Sunabori T, Shimmura S, Nagai Y, Nakagawa T, Okano H, et al. (2009). Development of mesenchymal stem cells partially originate from the neural crest. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 379, 1114–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagoshi N, Shibata S, Kubota Y, Nakamura M, Nagai Y, Satoh E, Morikawa S, Okada Y, Mabuchi Y, Katoh H, et al. (2008). Ontogeny and multipotency of neural crest-derived stem cells in mouse bone marrow, dorsal root ganglia, and whisker pad. Cell Stem Cell 2, 392–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura H and Ayer-le Lievre CS (1982). Mesectodermal capabilities of the trunk neural crest of birds. J Embryol Exp Morphol 70, 1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols DH (1986). Formation and distribution of neural crest mesenchyme to the first pharyngeal arch region of the mouse embryo. Am J Anat 176, 221–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa H, Miyazaki J and Smith AG (2000). Quantitative expression of Oct-3/4 defines differentiation, dedifferentiation or self-renewal of ES cells. Nat Genet 24, 372–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohba S, He X, Hojo H and McMahon AP (2015). Distinct Transcriptional Programs Underlie Sox9 Regulation of the Mammalian Chondrocyte. Cell Rep 12, 229–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okoturo E, Ogunbanjo OV and Arotiba GT (2016). Spontaneous Regeneration of the Mandible: An Institutional Audit of Regenerated Bone and Osteocompetent Periosteum. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 74, 1660–1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivera-Martinez I, Harada H, Halley PA and Storey KG (2012). Loss of FGF-dependent mesoderm identity and rise of endogenous retinoid signalling determine cessation of body axis elongation. PLoS Biol 10, e1001415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osorno R, Tsakiridis A, Wong F, Cambray N, Economou C, Wilkie R, Blin G, Scotting PJ, Chambers I and Wilson V (2012). The developmental dismantling of pluripotency is reversed by ectopic Oct4 expression. Development 139, 2288–2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piekarski N, Gross JB and Hanken J (2014). Evolutionary innovation and conservation in the embryonic derivation of the vertebrate skull. Nat Commun 5, 5661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piloto S and Schilling TF (2010). Ovo1 links Wnt signaling with N-cadherin localization during neural crest migration. Development 137, 1981–1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt JB (1893). Ectodermic origin of the cartilages of the head. Anat. Anz 8, 506–509. [Google Scholar]

- Quarto N, Wan DC, Kwan MD, Panetta NJ, Li S and Longaker MT (2010). Origin matters: differences in embryonic tissue origin and Wnt signaling determine the osteogenic potential and healing capacity of frontal and parietal calvarial bones. J Bone Miner Res 25, 1680–1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransom RC, Carter AC, Salhotra A, Leavitt T, Marecic O, Murphy MP, Lopez ML, Wei Y, Marshall CD, Shen EZ, et al. (2018). Mechanoresponsive stem cells acquire neural crest fate in jaw regeneration. Nature 563, 514–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven CP (1931). Zur Entwicklung der Ganglienleiste. I. Die Kinematik der Ganglienleisten Entwicklung bei den Urodelen. Wilhelm Roux Arch. EntwMech Org 125, 210–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scerbo P and Monsoro-Burq AH (2020). The vertebrate-specific VENTX/NANOG gene empowers neural crest with ectomesenchyme potential. Sci Adv 6, eaaz1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling TF and Kimmel CB (1994). Segment and cell type lineage restrictions during pharyngeal arch development in the zebrafish embryo. Development 120, 483–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sefton EM, Piekarski N and Hanken J (2015). Dual embryonic origin and patterning of the pharyngeal skeleton in the axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum). Evol Dev 17, 175–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada A, Kawanishi T, Kaneko T, Yoshihara H, Yano T, Inohaya K, Kinoshita M, Kamei Y, Tamura K and Takeda H (2013). Trunk exoskeleton in teleosts is mesodermal in origin. Nat Commun 4, 1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shubin N, Tabin C and Carroll S (2009). Deep homology and the origins of evolutionary novelty. Nature 457, 818–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoes-Costa M and Bronner ME (2016). Reprogramming of avian neural crest axial identity and cell fate. Science 352, 1570–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleight VA and Gillis JA (2020). Embryonic origin and serial homology of gill arches and paired fins in the skate, Leucoraja erinacea. Elife 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G (1904). The middle ear and columella of birds. Q J Microsc Sci 48, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Smith M, Hickman A, Amanze D, Lumsden A and Thorogood P (1994). Trunk Neural Crest Origin of Caudal Fin Mesenchyme in the Zebrafish Brachydanio rerio. Proceedings: Biological Sciences 256, 137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Soukup V, Epperlein HH, Horacek I and Cerny R (2008). Dual epithelial origin of vertebrate oral teeth. Nature 455, 795–U796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srour MK, Fogel JL, Yamaguchi KT, Montgomery AP, Izuhara AK, Misakian AL, Lam S, Lakeland DL, Urata MM, Lee JS, et al. (2015). Natural large-scale regeneration of rib cartilage in a mouse model. J Bone Miner Res 30, 297–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steventon B, Araya C, Linker C, Kuriyama S and Mayor R (2009). Differential requirements of BMP and Wnt signalling during gastrulation and neurulation define two steps in neural crest induction. Development 136, 771–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone LS (1922). Experiments on the development of the cranial ganglia and the lateral line sense organs in Amblystoma punctatum. The journal of experimental zoology. 35, 421. [Google Scholar]

- ---- (1926). Further experiments on the extirpation and transplantation of mesectoderm in Amblystoma punctatum. Journal of Experimental Zoology 44, 95–131. [Google Scholar]

- ---- (1929). Experiments showing the role of migrating neural crest (mesectoderm) in the formation of head skeleton and loose connective tissue in Rana palustris. Wilhelm Roux Arch Entwickl Mech Org 118, 40–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobl-Mazzulla PH, Sauka-Spengler T and Bronner-Fraser M (2010). Histone demethylase JmjD2A regulates neural crest specification. Dev Cell 19, 460–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stundl J, Pospisilova A, Jandzik D, Fabian P, Dobiasova B, Minarik M, Metscher BD, Soukup V and Cerny R (2019). Bichir external gills arise via heterochronic shift that accelerates hyoid arch development. Elife 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suszynska M, Zuba-Surma EK, Maj M, Mierzejewska K, Ratajczak J, Kucia M and Ratajczak MZ (2014). The proper criteria for identification and sorting of very small embryonic-like stem cells, and some nomenclature issues. Stem Cells Dev 23, 702–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K and Yamanaka S (2006). Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 126, 663–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashima Y, Era T, Nakao K, Kondo S, Kasuga M, Smith AG and Nishikawa S (2007). Neuroepithelial cells supply an initial transient wave of MSC differentiation. Cell 129, 1377–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan SS and Morriss-Kay G (1985). The development and distribution of the cranial neural crest in the rat embryo. Cell Tissue Res 240, 403–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W, Li Y, Li A and Bronner ME (2021). Clonal analysis and dynamic imaging identify multipotency of individual Gallus gallus caudal hindbrain neural crest cells toward cardiac and enteric fates. Nat Commun 12, 1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W, Martik ML, Li Y and Bronner ME (2019). Cardiac neural crest contributes to cardiomyocytes in amniotes and heart regeneration in zebrafish. Elife 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng CS, Cavin L, Maxson REJ, Sanchez-Villagra MR and Crump JG (2019). Resolving homology in the face of shifting germ layer origins: Lessons from a major skull vault boundary. Elife 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisse B, el Messal M and Perrin-Schmitt F (1987). The twist gene: isolation of a Drosophila zygotic gene necessary for the establishment of dorsoventral pattern. Nucleic Acids Res 15, 3439–3453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AJ and Erickson CA (2009). FOXD3 regulates the lineage switch between neural crest-derived glial cells and pigment cells by repressing MITF through a non-canonical mechanism. Development 136, 1849–1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson H, Ohazama A, Sharpe PT and Tucker AS (2012). The origin of the stapes and relationship to the otic capsule and oval window. Dev Dyn 241, 1396–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson H and Tucker AS (2013). Dual origin of the epithelium of the mammalian middle ear. Science 339, 1453–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzouanacou E, Wegener A, Wymeersch FJ, Wilson V and Nicolas JF (2009). Redefining the progression of lineage segregations during mammalian embryogenesis by clonal analysis. Dev Cell 17, 365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaglia JL and Smith KK (2003). Early differentiation and migration of cranial neural crest in the opossum, Monodelphis domestica. Evol Dev 5, 121–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickaryous MK and Sire JY (2009). The integumentary skeleton of tetrapods: origin, evolution, and development. J Anat 214, 441–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt W (1929). Gestaltungsanalyse am Amphibienkeim mit Örtlicher Vitalfärbung - II. Teil. Gastrulation und Mesodermbildung bei Urodelen und Anuren. pp. 384–706: Wilhelm Roux' Archiv für Entwicklungsmechanik der Organismen. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner DE, Weinreb C, Collins ZM, Briggs JA, Megason SG and Klein AM (2018). Single-cell mapping of gene expression landscapes and lineage in the zebrafish embryo. Science 360, 981–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldo K, Zdanowicz M, Burch J, Kumiski DH, Stadt HA, Godt RE, Creazzo TL and Kirby ML (1999). A novel role for cardiac neural crest in heart development. J Clin Invest 103, 1499–1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston JA (1963). A radioautographic analysis of the migration and localization of trunk neural crest cells in the chick. Dev Biol 6, 279–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston JA, Yoshida H, Robinson V, Nishikawa S, Fraser ST and Nishikawa S (2004). Neural crest and the origin of ectomesenchyme: neural fold heterogeneity suggests an alternative hypothesis. Dev Dyn 229, 118–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead GG, Makino S, Lien CL and Keating MT (2005). fgf20 is essential for initiating zebrafish fin regeneration. Science 310, 1957–1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SY, Yang YP and McClay DR (2008). Twist is an essential regulator of the skeletogenic gene regulatory network in the sea urchin embryo. Dev Biol 319, 406–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie M, Kamenev D, Kaucka M, Kastriti ME, Zhou B, Artemov AV, Storer M, Fried K, Adameyko I, Dyachuk V, et al. (2019). Schwann cell precursors contribute to skeletal formation during embryonic development in mice and zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116, 15068–15073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi H, Goto M, Katayama M, Miyake A and Itoh N (2011). Fgf20b is required for the ectomesenchymal fate establishment of cranial neural crest cells in zebrafish. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 409, 705–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, Stewart R, et al. (2007). Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science 318, 1917–1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalc A, Sinha R, Gulati GS, Wesche DJ, Daszczuk P, Swigut T, Weissman IL and Wysocka J (2021). Reactivation of the pluripotency program precedes formation of the cranial neural crest. Science 371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]