Abstract

Background & Aims

Obesity-related hyperglycemia, with hepatic insulin resistance, has become an epidemic disease. Central neural leptin signaling was reported to improve hyperglycemia. The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of hepatic leptin signaling on controlling hyperglycemia.

Methods

First, the effect of leptin signaling on gluconeogenesis was investigated in primary mouse hepatocytes and hepatoma cells. Second, glucose tolerance, insulin tolerance, blood glucose levels, and hepatic gluconeogenic gene expression were analyzed in obese mice overexpressing hepatic OBRb. Third, expression of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase (MKP)-3, phosphorylation level of signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 3, and extracellular regulated protein kinase (ERK) were analyzed in hepatocytes and mouse liver. Fourth, the role of MKP-3 in hepatic leptin signaling regulating gluconeogenesis was analyzed. Lastly, the role of ERK and STAT3 in the regulation of MKP-3 protein by leptin signaling was analyzed.

Results

Activation of hepatic leptin signaling suppressed gluconeogenesis in both hepatocytes and obese mouse liver, and improved hyperglycemia, insulin tolerance, and glucose tolerance in obese mice. The protein level of MKP-3, which can promote gluconeogenesis, was decreased by leptin signaling in both hepatocytes and mouse liver. Mkp-3 deficiency abolished the effect of hepatic leptin signaling on suppressing gluconeogenesis in hepatocytes. STAT3 decreased the MKP-3 protein level, while inactivation of STAT3 abolished the effect of leptin signaling on reducing the MKP-3 protein level in hepatocytes. Moreover, STAT3 could combine with MKP-3 and phospho-ERK1/2, which induced the degradation of MKP-3, and leptin signaling enhanced the combination.

Conclusions

Hepatic leptin signaling could suppress gluconeogenesis at least partially by decreasing the MKP-3 protein level via STAT3-enhanced MKP-3 and ERK1/2 combination.

Keywords: Liver, Leptin, Gluconeogenesis, MKP-3, STAT3, ERK

Abbreviations used in this paper: ACC, acetyl-CoA carboxylase; Ad, adenovirus; AICAR, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide; AKT, protein kinase B; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; cDNA, complementary DNA; DIO, diet-induced obese; DMEM, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium; DN, dominant-negative; ERK, extracellular regulated protein kinase; FOXO1, forkhead-box protein O1; GFP, green fluorescent protein; GTT, glucose tolerance test; IR, insulin receptor; ITT, insulin tolerance test; MKP-3, MAPK phosphatase-3; mRNA, messenger RNA; OBRb, long-form leptin receptor; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; TAK1, transforming growth factor-β–activated kinase 1

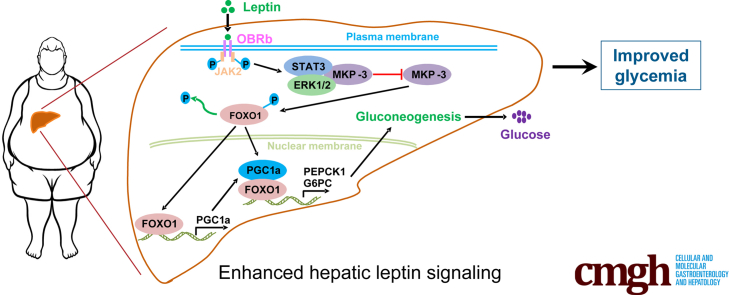

Graphical abstract

Summary.

Hepatic leptin signaling could improve hyperglycemia in obese mice by suppressing gluconeogenesis. Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase 3 (MKP-3) is required for leptin signaling to suppress gluconeogenesis. Leptin signaling induced MKP-3 degradation via signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 enhanced MKP-3 and extracellular regulated protein kinase combination.

Obesity-related hyperglycemia has become an epidemic disease, which may result in type 2 diabetes.1 The reason for hyperglycemia is uncontrolled hepatic gluconeogenesis and impaired glucose clearance. Hepatic gluconeogenesis is controlled mainly by insulin, through the insulin receptor (IR)/IR substrates/phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT) pathway.2 Activated AKT can phosphorylate forkhead-box protein O1 (FOXO1) to reduce the transcription of key gluconeogenic genes, such as PEPCK1 and G6PC.2 In the situation of obesity, the sensitivity of IR to insulin is impaired in the liver, which results in uncontrolled gluconeogenesis and subsequently leads to hyperglycemia.1

The adipokine leptin was reported to suppress gluconeogenesis through the central nervous system.3, 4, 5 Leptin plays its role by binding to and activating the long-form leptin receptor (OBRb), a transmembrane protein. Many functions of leptin on peripheral tissue are through the central nervous system, including the regulation of hepatic gluconeogenesis. Although OBRb was found to be expressed in the liver,6, 7, 8 reports of the effect of hepatic leptin signaling on gluconeogenesis have been conflicting in the literature.4,9, 10, 11, 12 Activation of OBRb subsequently can activate signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK).13,14 In addition, STAT3 was reported to suppress gluconeogenesis by directly inhibiting the expression of PEPCK1 and G6PC genes or through the microRNA-23a/peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1-α (PGC1a) pathway.15, 16, 17 In addition, activation of AMPK also can suppress gluconeogenesis in the liver.18 However, the roles of STAT3 and AMPK in hepatic leptin signaling regulating gluconeogenesis are uncertain.

Our previous study showed that MAPK phosphatase-3 (MKP-3) can promote hepatic gluconeogenesis by dephosphorylating Foxo1 and stimulating the expression of Pgc1a.19 In addition, knock-down of Mkp-3 in the liver suppressed gluconeogenesis in both lean and diet-induced obese mice.19 Hormones, such as insulin, could induce the phosphorylation of MKP-3 on Ser159 and Ser197 via the extracellular regulated protein kinase (ERK) pathway, which results in the degradation of MKP-3 in a caspase- or ubiquitin-mediated manner.20, 21, 22 However, it is unknown whether MKP-3 expression could be regulated by leptin signaling and whether MKP-3 was involved in hepatic leptin signaling regulating gluconeogenesis. The current study investigated the effect of hepatic leptin signaling on gluconeogenesis by both in vitro and in vivo studies, analyzed the role of MKP-3 in leptin signaling suppressing gluconeogenesis, and explored how leptin signaling regulated MKP-3 expression.

Results

Activation of Hepatic Leptin Signaling Attenuated Gluconeogenesis In Vitro

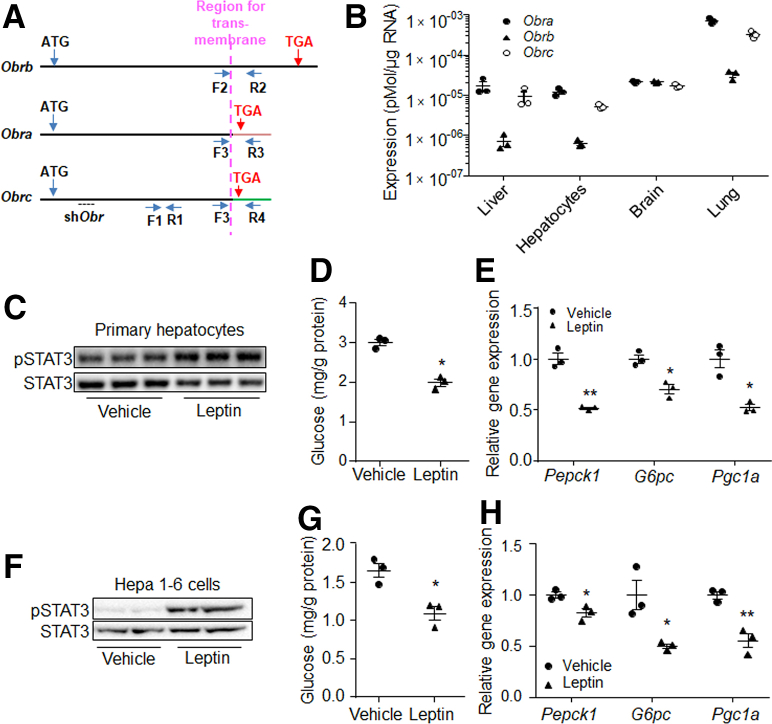

It has been reported that several isoforms of OBR exist in mammals, but OBRb is the only full-length isoform, while OBRa and OBRc lack the intracellular structure (Figure 1A). We first analyzed the expression levels of Obrs in mouse liver and hepatocytes. Results showed that Obra, Obrb, and Obrc all were expressed in liver, primary hepatocytes, brain, and lung, although the expression of Obrb was low in liver and hepatocytes (Figure 1B). We then treated primary mouse hepatocytes with leptin, which showed that leptin induced the phosphorylation level of STAT3 (Figure 1C), a marker of leptin signaling, compared with the control. Glucose production and expression of gluconeogenic genes Pepck1, G6pc, and their regulatory gene Pgc1a were suppressed in response to leptin treatment (Figure 1D and E). Similar results also were observed in mouse hepatoma cell line Hepa 1–6 (Figure 1F–H).

Figure 1.

Leptin suppressed gluconeogenesis in hepatocytes. (A) Sites for primers in Obr cDNA. F1 and R1, forward and reverse primers for Obr; F2 and R2, forward and reverse primers for Obrb; F3, forward primer for Obra and Obrc; R3, reverse primer for Obra; R4, reverse primer for Obrc. (B) The absolute mRNA levels of Obra, Obrb, and Obrc in mouse tissues and primary hepatocytes. Phosphorylation level of (C) STAT3, (D) glucose production, and (E) gene expression levels of Pepck1, G6pc, and Pgc1a in 80 ng/mL leptin or vehicle-treated primary mouse hepatocytes. Phosphorylation level of (F) STAT3, (G) glucose production, and (H) gene expression levels of Pepck1, G6pc, and Pgc1a in 80 ng/mL leptin or vehicle-treated Hepa 1–6 cells. N = 3 for each group of pot graphs. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01 compared with the control group. Results represent 1 of 3 independently performed experiments. pSTAT3, phospho-STAT3.

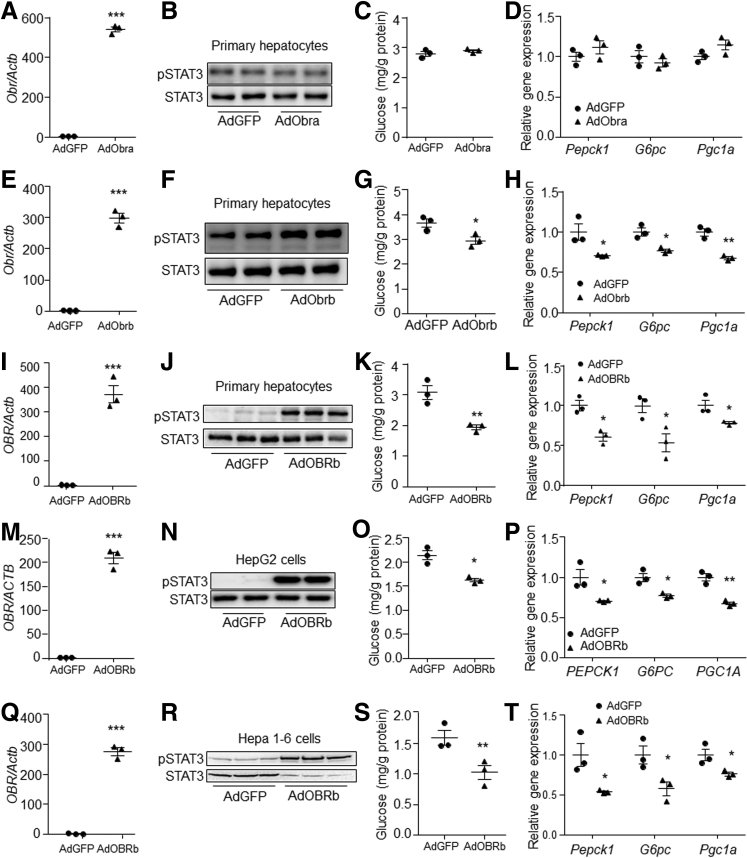

The effects of OBRa and OBRb on gluconeogenesis then were investigated in primary hepatocytes by adenovirus-mediated Obra and Obrb overexpression. Results showed that Obra overexpression did not change the STAT3 phosphorylation level, glucose production, or expression of gluconeogenic genes in primary mouse hepatocytes in the presence of leptin (Figure 2A–D). However, Obrb overexpression induced STAT3 phosphorylation (Figure 2E and F), and suppressed glucose production and expression of gluconeogenic genes in the presence of leptin in primary hepatocytes, compared with controls (Figure 2G and H). In addition, overexpression of human OBRb also suppressed gluconeogenesis in primary mouse hepatocytes (Figure 2I–L), human hepatoma HepG2 cells (Figure 2M–P), and Hepa 1–6 cells (Figure 2Q–T) in the presence of leptin compared with their respective controls. These data indicate that hepatic OBRb signaling can suppress gluconeogenesis in vitro.

Figure 2.

Overexpression of long-form leptin receptor suppressed gluconeogenesis in hepatocytes. (A) Obr expression level, (B) STAT3 phosphorylation level, (C) glucose production, and (D) gene expression levels in AdGFP or AdObra-infected primary hepatocytes in the presence of 80 ng/mL leptin. (E) Obr expression, (F) STAT3 phosphorylation level, (G) glucose production, and (H) gene expression levels in AdGFP- or AdObrb-infected primary hepatocytes in the presence of 80 ng/mL leptin. (I) OBR expression, (J) STAT3 phosphorylation level, (K) glucose production, and (L) gene expression levels in AdGFP- or AdOBRb-infected primary hepatocytes in the presence of 80 ng/mL leptin. (M) OBR expression, (N) STAT3 phosphorylation level, (O) glucose production, and (P) gene expression levels in AdGFP- or AdOBRb-infected HepG2 cells in the presence of 80 ng/mL leptin. (Q) OBR expression level, (R) STAT3 phosphorylation level, (S) glucose production, and (T) gene expression levels in AdGFP- or AdOBRb-infected Hepa 1–6 cells in the presence of 80 ng/mL leptin. N = 3 for each group of pot graphs. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, and ∗∗∗P < .001 compared with the control group. Cell studies were reapeated for 3 times, and results represent 1 of 3 independently performed experiments. pSTAT3, phospho-STAT3.

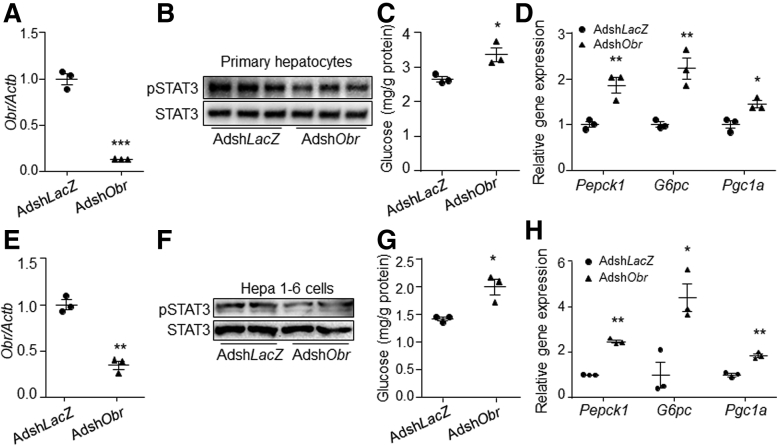

Loss-of-function study using short hairpin RNA against Obr (shObr) then were performed. Results showed that shObr significantly decreased the expression of endogenous Obr and reduced the phosphorylation level of STAT3 compared with control in both primary mouse hepatocytes and Hepa 1–6 cells in the presence of leptin (Figure 3A, B, E, and F). The glucose production and gene expression level of Pepck1, G6pc, and Pgc1a were increased by Obr knock-down in the presence of leptin compared with control (Figure 3C, D, G, and H).

Figure 3.

Knock-down of leptin-receptor induced gluconeogenesis in hepatocytes. (A) Obr expression, (B) STAT3 phosphorylation level, (C) glucose production, and (D) gene expression levels of Pepck1, G6pc, and Pgc1a in AdshLacZ- or AdshObr-infected primary hepatocytes in the presence of 80 ng/mL leptin. (E) Obr expression, (F) STAT3 phosphorylation level, (G) glucose production, and (H) gene expression levels of Pepck1, G6pc, and Pgc1a in AdshLacZ- or AdshObr-infected Hepa 1–6 cells in the presence of 80 ng/mL leptin. N = 3 for each group of pot graphs. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, and ∗∗∗P < .001 compared with the control group. Results represent 1 of 3 independently performed experiments. pSTAT3, phospho-STAT3.

Activation of Hepatic Leptin Signaling Improved Hyperglycemia by Suppressing Gluconeogenesis in Obese Mice

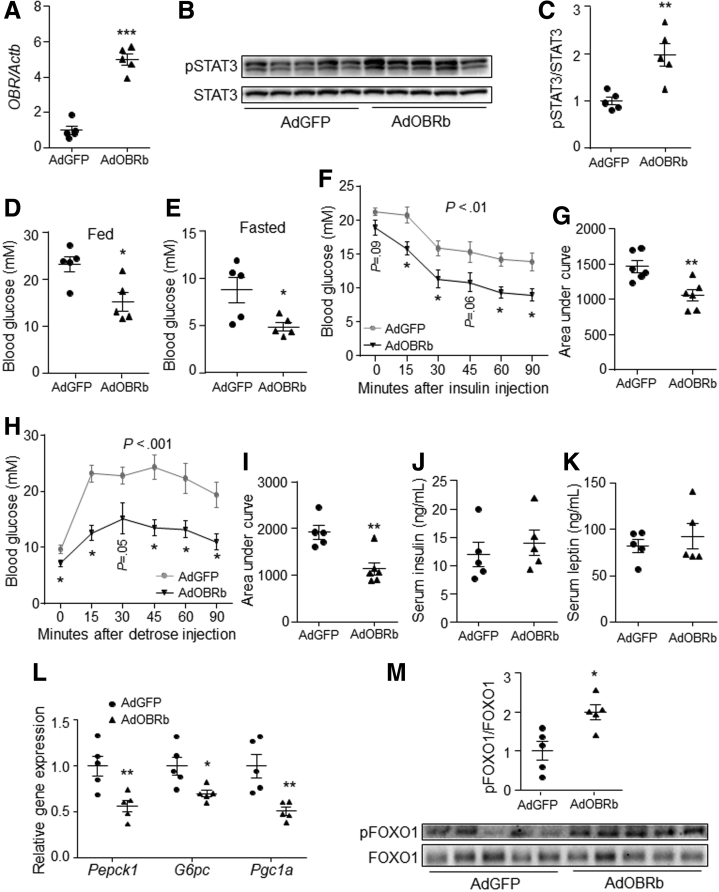

To further investigate the effect of hepatic leptin signaling on gluconeogenesis in vivo, the human OBRb gene was overexpressed in the liver of leptin-receptor–deficient (db/db) mice by tail vein–injection of adenovirus cloned with human OBRb (AdOBRb). The expression of OBR and the phosphorylation level of STAT3 were induced significantly by AdOBRb injection compared to control (Figure 4A–C), while the expression of human OBRb was undetectable in the brain of both groups. Further study showed that AdOBRb-injected mice had lower feeding and fasting blood glucose levels than control mice did (Figure 4D and E). In addition, OBRb overexpression in the liver improved mouse insulin tolerance and glucose tolerance compared with control (Figure 4F–I). However, the serum contents of insulin and leptin were not changed by hepatic OBRb overexpression under fasting status (Figure 4J and K). Furthermore, the gene expression levels of Pepck1, G6pc, and Pgc1a were down-regulated by hepatic OBRb overexpression (Figure 4L). In addition, the phosphorylation level of FOXO1 in the liver was increased significantly by OBRb overexpression compared with controls (Figure 4M).

Figure 4.

Activation of hepatic leptin signaling suppressed liver gluconeogenesis in db/db mice.Db/db mice were tail vein–injected with AdGFP or AdOBRb at a dose of 2 × 1011 virus particles per mouse. (A) Gene expression level of OBR in the liver (N = 5 for each group). (B and C) Phosphorylation level of STAT3 in the liver. (D) Feeding blood glucose level (N = 5 for each group). (E) Fasting blood glucose level (N = 5 for each group). (F and G) Insulin tolerance test (N = 6 for each group). (H and I) Glucose tolerance test (N = 5 for AdGFP and N = 6 for AdOBRb). (J) Fasting serum insulin level (N = 5 for each group). (K) Fasting serum leptin level (N = 5 for each group). (L) Gene expression levels of Pepck1, G6pc, and Pgc1a in the liver (N = 5 for each group). (M) Phosphorylation level of FOXO1 in the liver (N = 5 for each group). ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, and ∗∗∗P < .001 compared with the control group. pSTAT3, phospho-STAT3.

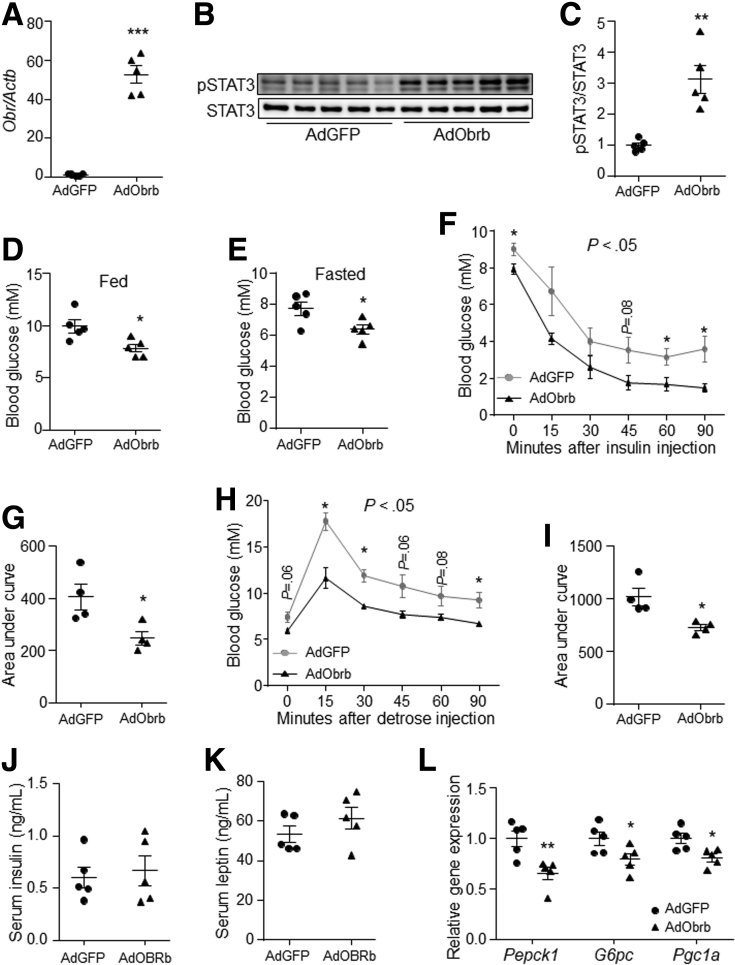

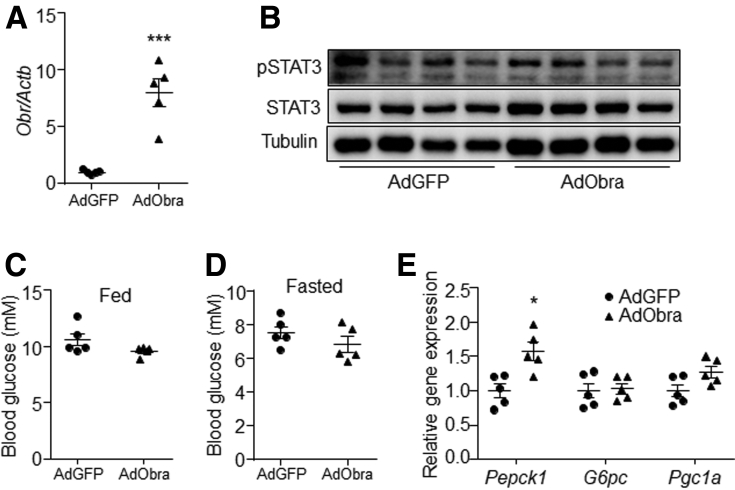

Obesity is associated with leptin resistance.23,24 Thus, the effect of hepatic leptin signaling on gluconeogenesis also was investigated in diet-induced obese (DIO) mice. Results showed that overexpression of the mouse Obrb gene in DIO mouse liver induced the phosphorylation level of STAT3, and reduced blood glucose level (Figure 5A–E). In addition, insulin tolerance and glucose tolerance were improved by hepatic Obrb overexpression compared with control (Figure 5F–I). However, serum contents of insulin and leptin were similar between the controls and AdObrb-infected mice under fasting conditions (Figure 5J and K). Furthermore, the gene expression levels of liver Pepck1, G6pc, and Pgc1a were down-regulated by Obrb overexpression (Figure 5L). However, hepatic Obra overexpression did not change the STAT3 phosphorylation level, blood glucose level, or liver gluconeogenic gene expression (Figure 6A–E). These data indicate that activation of OBRb signaling only in the liver can suppress gluconeogenesis in vivo.

Figure 5.

Activation of hepatic leptin signaling suppressed liver gluconeogenesis in DIO mice. DIO mice were tail vein–injected with AdGFP or AdObrb at a dose of 2 × 1011 virus particles per mouse. (A) Gene expression level of Obr in the liver (N = 5 for each group). (B and C) Phosphorylation level of STAT3 in the liver. (D) Feeding blood glucose level (N = 5 for each group). (E) Fasting blood glucose level (N = 5 for each group). (F and G) Insulin tolerance test (N = 4 for each group). (H and I) Glucose tolerance test (N = 4 for each group). (J) Fasting serum insulin level (N = 5 for each group). (K) Fasting serum leptin level (N = 5 for each group). (L) The gene expression levels of Pepck1, G6pc, and Pgc1a in the liver (N = 5 for each group). ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, and ∗∗∗P < .001 compared with the control group. pSTAT3, phospho-STAT3.

Figure 6.

Hepatic Obra overexpression had no effect on gluconeogenesis in DIO mice. DIO mice were tail vein–injected with AdGFP or AdObra at a dose of 2 × 1011 virus particles per mouse. (A) Gene expression level of Obr in the liver. (B) Phosphorylation level of STAT3 in the liver. (C) Feeding blood glucose level. (D) Fasting blood glucose level. (E) Gene expression levels of Pepck1, G6pc, and Pgc1a in the liver. N = 5 for each group. ∗P < .05, ∗∗∗P < .001 compared with the control group. pSTAT3, phospho-STAT3.

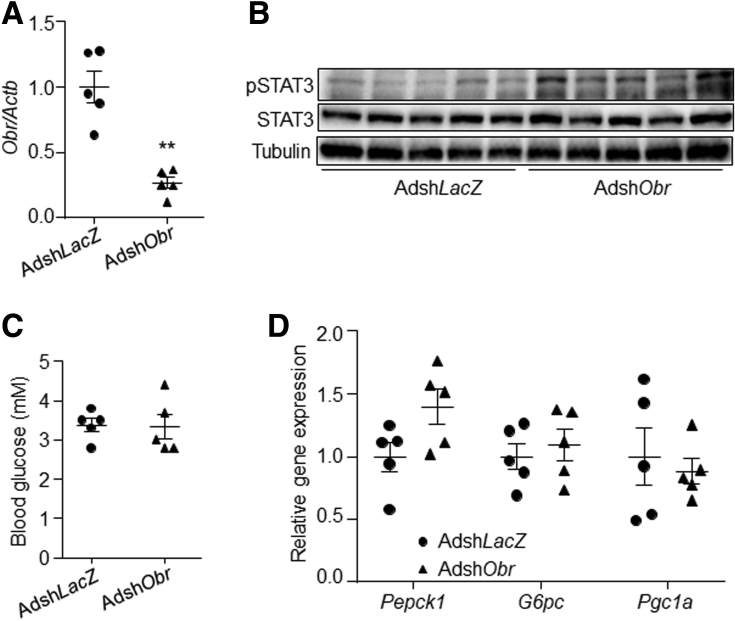

A liver-specific Obr gene knock-down study then was performed in lean mice. Results showed that knock-down of Obr in the liver slightly induced the STAT3 phosphorylation level, but did not change the blood glucose level or the expression of gluconeogenic genes compared with the control group (Figure 7A–D).

Figure 7.

Obr knock-down in mouse liver did not change gluconeogenesis. Eighteen-week old C57BL6J male mice were injected with AdshLacZ or AdshObr adenovirus at a dose of 5 × 1011 virus particles per mouse through the tail vein. Fasting blood glucose levels were measured on day 7 after injection. Mice then were killed on day 7 at a fasting state. (A) Gene expression level of Obr in the liver. (B) Phosphorylation level of STAT3 in the liver. (C) Blood glucose level at fasting state. (D) Gene expression levels of Pepck1, G6pc, and Pgc1a in the liver. N = 5 for each group. ∗∗P < .01 compared with the control group. pSTAT3, phospho-STAT3.

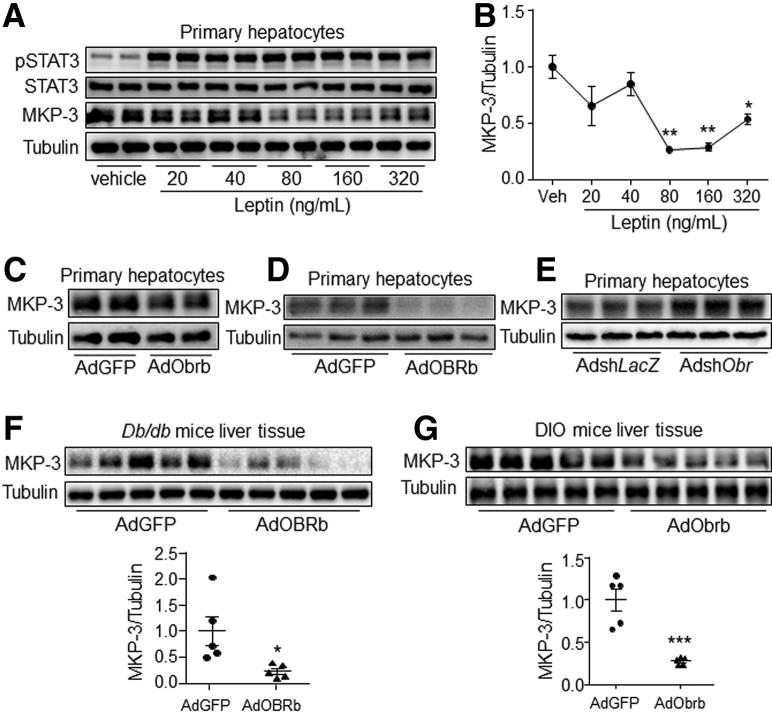

Hepatic Leptin Signaling Decreased MKP-3 Protein Level

Our previous studies have reported that MKP-3 promotes hepatic gluconeogenesis, and the MKP-3 protein level can be down-regulated by the growth hormone insulin.19,21 The protein expression of MKP-3 could be suppressed by leptin at a dose of 80 ng/mL or higher (Figure 8A and B). In addition, OBRb or Obrb overexpression significantly decreased the MKP-3 protein level, while Obr knock-down increased it, in the presence of leptin in primary mouse hepatocytes compared with their respective controls (Figure 8C–E). Furthermore, the protein level of MKP-3 was significantly lower in the db/db mouse liver overexpressing OBRb and in the DIO mouse liver overexpressing Obrb than in their respective controls (Figure 8F and G). However, the messenger RNA (mRNA) level of MKP-3 was decreased only slightly by OBRb overexpression in Hepa 1–6 cells, while no change was observed in leptin-treated Hepa 1–6 cells or AdOBRb-infected primary hepatocytes or mouse liver compared with their respective controls (Figure 9A–E). These data indicate that hepatic leptin signaling can reduce the protein level of MKP-3 both in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 8.

Hepatic leptin signaling decreased the MKP-3 protein level both in vitro and in vivo. (A and B) Primary mouse hepatocytes were treated with vehicle or leptin at the indicated dose for 1 hour. (A) The phosphorylation level of STAT3 and the protein level of MKP-3 were detected with the cells, and (B) the protein band of MKP-3 was quantified using ImageJ software. (C) MKP-3 protein level in AdGFP- or AdObrb-infected primary mouse hepatocytes in the presence of 80 ng/mL leptin. (D) MKP-3 protein level in AdGFP- or AdOBRb-infected primary mouse hepatocytes in the presence of 80 ng/mL leptin. (E) MKP-3 protein level in AdshLacZ- or AdshObr-infected primary mouse hepatocytes in the presence of 80 ng/mL leptin. (F) MKP-3 protein level in AdGFP- or AdOBRb-infected db/db mouse liver. (G) MKP-3 protein level in AdGFP- or AdObrb-infected DIO mouse liver. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, and ∗∗∗P < .001 compared with the control group. Results for the cell study represent 1 of 3 independently performed experiments. pSTAT3, phospho-STAT3.

Figure 9.

mRNA levels of Mkp-3 in hepatocytes and mouse livers. (A) Hepa 1–6 cells were treated with 80 ng/mL leptin or vehicle for the indicated time. Real-time PCR was used to detect the mRNA level of Mkp-3 in the cells. (B) Mkp-3 mRNA level in AdOBRb- or AdGFP-infected primary mouse hepatocytes in the presence of 80 ng/mL leptin. (C) Mkp-3 mRNA level in AdOBRb- or AdGFP-infected Hepa 1–6 cells in the presence of 80 ng/mL leptin. (D) Mkp-3 mRNA level in the liver of AdGFP- or AdOBRb-infected db/db mice. (E) Mkp-3 mRNA levels in the liver of AdGFP- or AdObrb-infected DIO mice. N = 3 per treatment for cell studies, and N = 5 per group for mouse studies. ∗P < .05 compared with the control group. Results for the cell study represent 1 of 3 independently performed experiments.

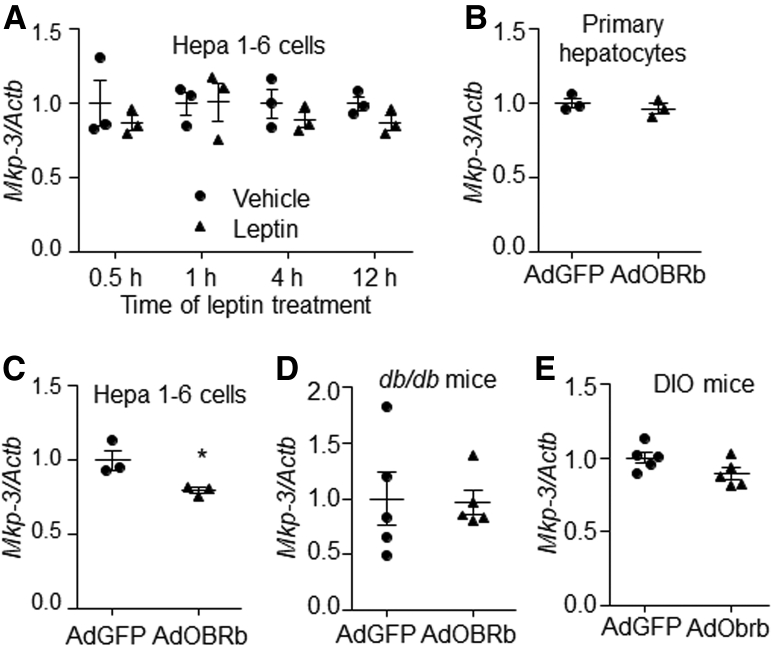

MKP-3 Is Involved in Leptin Signaling Suppressing Gluconeogenesis

We then investigated whether MKP-3 was involved in hepatic leptin signaling suppressing gluconeogenesis. Results showed that Mkp-3 overexpression reversed glucose production and expression of gluconeogenic genes those were suppressed by leptin in HepG2 cells (Figure 10A).

Figure 10.

MKP-3 was involved in the process of leptin signaling suppressing gluconeogenesis in hepatocytes. (A) HepG2 cells were infected with AdMkp-3 or Adb-gal for 48 hours. Cells then were treated with vehicle or 80 ng/mL leptin. A glucose output assay and measure of gene expression then were performed. (B and C) Wild-type primary hepatocytes and MKP-3–deficiency primary hepatocytes were isolated from the wild-type mouse and the MKP-3–deficient littermate, respectively. (B) Forty-eight hours after seeding, cells were treated with 80 ng/mL leptin or vehicle, and then were assessed for glucose output assay and gene expression study. (C) Cells were infected with AdGFP or AdOBRb. Forty-eight hours later, cells were assessed for glucose output assay and gene expression study in the presence of 80 ng/mL leptin. N = 3 for each treatment. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, and ∗∗∗P < .001 as marked. Results represent 1 of 3 independently performed experiments. MKP-3 KO, MKP-3–deficient primary hepatocytes; WT, wild-type primary hepatocytes.

The Mkp-3–deficient primary mouse hepatocytes then were used. Although leptin suppressed the glucose production and gluconeogenic gene expression in wild-type primary hepatocytes, this effect was not observed in Mkp-3–deficient primary hepatocytes (Figure 10B). In addition, although OBRb was overexpressed in both wild-type and Mkp-3–deficient primary hepatocytes, Mkp-3 deficiency blocked the reduction effect of leptin signaling on glucose production and gluconeogenic gene expression (Figure 10C). These data show that MKP-3 is involved in hepatic leptin signaling suppressing gluconeogenesis.

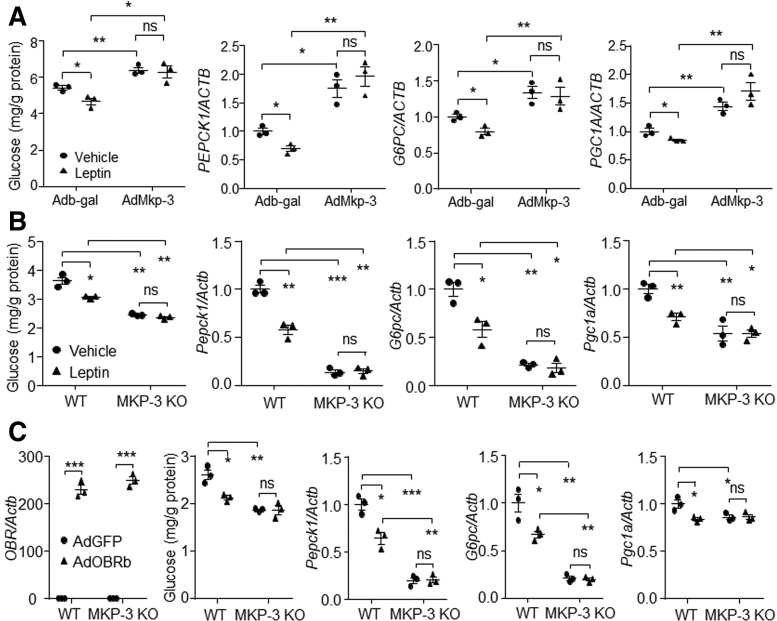

AMPK Suppressed MKP-3 Expression Independent of Leptin Signaling

Because leptin can activate hepatic AMPKα through the sympathetic nervous system,14 and an increase of AMPK phosphorylation was accompanied by a decrease of MKP-3 protein in heart,25 we investigated whether leptin could reduce the MKP-3 protein level through the AMPK pathway in liver. Results showed that although leptin did not change the AMPKα phosphorylation level in hepatocytes (Figure 11A), overexpression of OBRb/Obrb increased the phosphorylation level of AMPKα in the presence of leptin in primary hepatocytes compared with their respective controls (Figure 11B and C). In addition, knock-down of Obr expression in hepatocytes attenuated the phosphorylation level of AMPKα in the presence of leptin (Figure 11D). Furthermore, an increase in the AMPKα phosphorylation level was observed in AdOBRb-infected db/db mouse liver (Figure 11E) and in the AdObrb-infected DIO mouse liver (Figure 11F), compared with their respective controls.

Figure 11.

Hepatic leptin signaling increased the phosphorylation level of AMPKα. (A) Phosphorylation level of AMPKα in 80 ng/mL leptin or vehicle-treated primary mouse hepatocytes. (B) AMPKα phosphorylation level in AdGFP- or AdObrb-infected primary mouse hepatocytes in the presence of 80 ng/mL leptin. (C) AMPKα phosphorylation level in AdGFP- or AdOBRb-infected primary mouse hepatocytes in the presence of 80 ng/mL leptin. (D) AMPKα phosphorylation level in AdshLacZ- or AdshObr-infected primary mouse hepatocytes in the presence of 80 ng/mL leptin. (E) AMPKα phosphorylation level in AdGFP- or AdOBRb-infected db/db mouse liver. (F) AMPKα phosphorylation level in AdGFP- or AdObrb-infected DIO mouse liver. ∗∗P < .01 compared with the control group. Results for the cell study represent 1 of 3 independently performed experiments. pAMPKα, phospho-AMPKα.

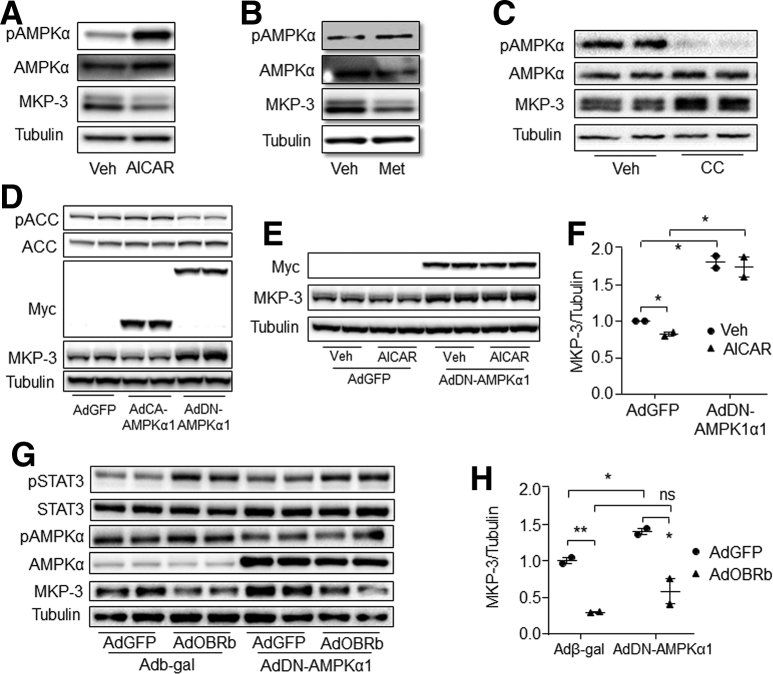

Activation of AMPK by 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR) or metformin decreased the MKP-3 protein level compared with controls (Figure 12A and B). On the other hand, inhibition of AMPK by its specific inhibitor Compound C significantly increased the MKP-3 protein level (Figure 12C). In addition, overexpression of the constitutively active form of AMPKα1 increased the phosphorylation level of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) and decreased the protein level of MKP-3, while overexpression of the dominant-negative form of AMPKα1 (DN-AMPKα1) attenuated the phosphorylation level of ACC and increased the protein level of MKP-3 (Figure 12D). Furthermore, inactivation of endogenous AMPKα by overexpression of DN-AMPKα1 eliminated the decreasing effect of AICAR on the MKP-3 protein level (Figure 12E and F). These data indicate that AMPK can decrease the MKP-3 protein level.

Figure 12.

AMPK suppressed MKP-3 expression independent of leptin signaling. (A) MKP-3 protein level in primary hepatocytes that were treated with 1 mmol/L AICAR or vehicle for 1 hour. (B) MKP-3 protein level in primary hepatocytes that were treated with 0.5 mmol/L metformin or vehicle for 1 hour. (C) MKP-3 protein level in 10 μmol/L compound C or vehicle-treated primary hepatocytes. (D) MKP-3 protein level in AdGFP, AdCA-AMPKα1, or AdDN-AMPKα1–infected hepatocytes. (E and F) MKP-3 protein level in AICAR or vehicle-treated and AdGFP or AdDN-AMPKα1–infected primary hepatocytes. (G and H) Protein levels in AdGFP- or AdOBRb- and Adb-gal- or AdDN-AMPKα1-infected hepatocytes. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01 as marked. Results for cell studies represent 1 of 3 independently performed experiments. AdCA-AMPKα1, adenovirus cloned with constitutively activating mutation of AMPKα1; CC, compound C; Met, metformin; Veh, vehicle.

We then investigated whether AMPK was involved in the process of leptin signaling reducing MKP-3 protein in hepatocytes. Results showed that AMPK inactivation could not block the effect of leptin signaling on reducing the MKP-3 protein level (Figure 12G and H). These data indicate that leptin signaling might reduce the MKP-3 protein level independent of the AMPK pathway.

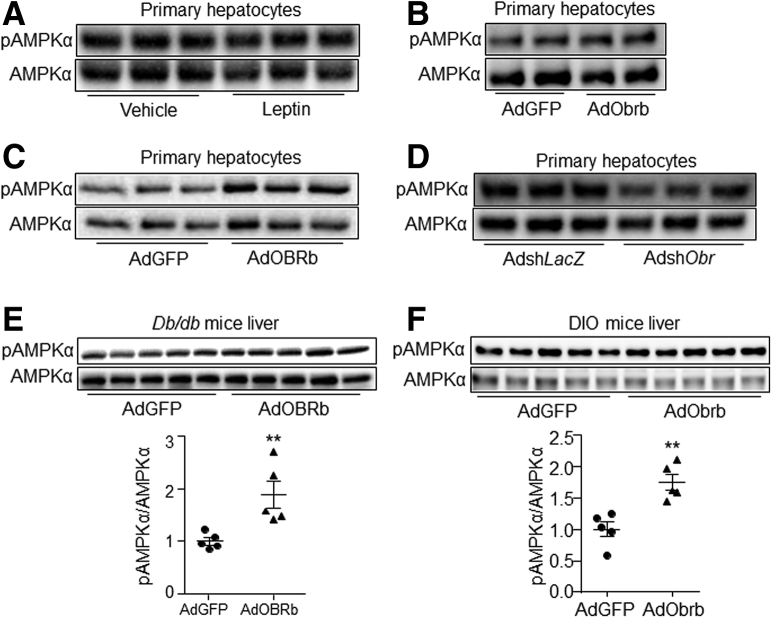

STAT3-Mediated Leptin Signaling to Decrease MKP-3 Protein Level

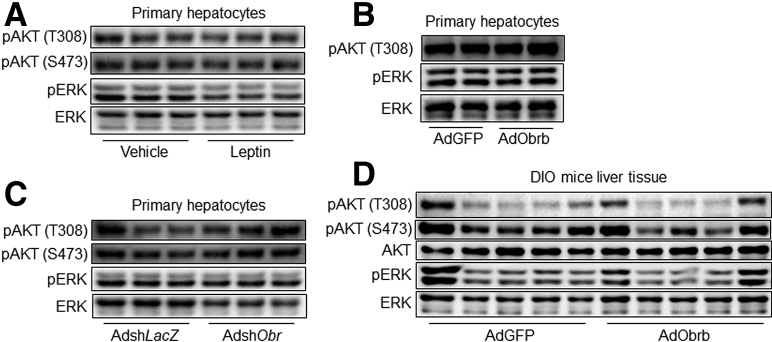

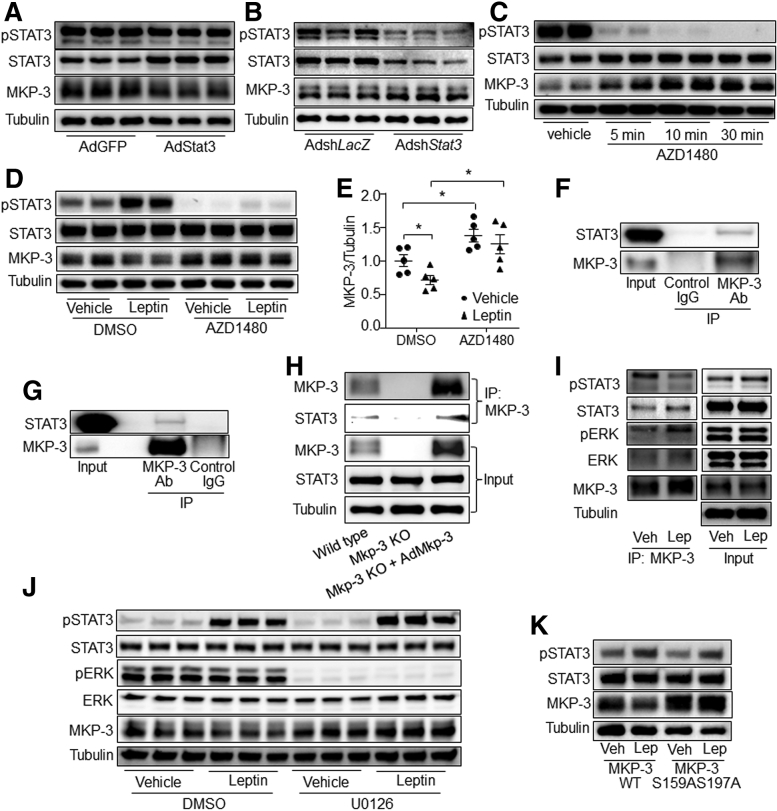

ERK1/2 and AKT signaling have been reported to suppress MKP-3 protein expression. However, the phosphorylation levels of ERK1/2 or AKT was not changed by leptin signaling in primary mouse hepatocytes or mouse liver (Figure 13A–D). Thus, we investigated whether STAT3 was involved in leptin signaling reducing MKP-3 protein level. Results showed that Stat3 overexpression decreased the MKP-3 protein level, while knock-down of Stat3 increased it in hepatocytes, compared with their respective controls (Figure 14A and B). In addition, AZD1480, an inhibitor of janus kinase 2 (JAK2), markedly induced protein levels of MKP-3 in primary mouse hepatocytes (Figure 14C). Furthermore, AZD1480 reversed the reducing effect of leptin signaling on the MKP-3 protein level (Figure 14D and E). In addition, a co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) study showed that STAT3 protein could be co-immunoprecipitated by anti–MKP-3 antibody in wild-type hepatocytes, mouse liver, and AdMkp-3–infected Mkp-3–deficient hepatocytes (Figure 14F–H), while no band of STAT3 was observed in the immune-precipitate of Mkp-3–deficient hepatocytes (Figure 14H). Interestingly, leptin treatment increased the combination of STAT3, phospho-ERK1/2, and ERK1/2 with MKP-3 (Figure 14I). Furthermore, inactivation of ERK eliminated the effect of leptin on reducing the protein level of MKP-3 in primary mouse hepatocytes (Figure 14J).

Figure 13.

Hepatic leptin signaling has no effect on the AKT or ERK pathway. (A) Phosphorylation levels of AKT and ERK in 80 ng/mL leptin or vehicle-treated primary hepatocytes. (B) Phosphorylation levels of AKT and ERK in AdGFP- or AdObrb-infected primary hepatocytes in the presence of 80 ng/mL leptin. (C) Phosphorylation levels of AKT and ERK in Obrb knock-down primary hepatocytes in the presence of 80 ng/mL leptin. (D) Phosphorylation levels of AKT and ERK in the liver of AdObrb- or AdGFP-infected mice. Results for cell studies represent 1 of 3 independently performed experiments. pAKT, phospho-AKT; pERK, phospho-ERK1/2.

Figure 14.

STAT3 combined with MKP-3 and mediated leptin signaling to induce MKP-3 protein degradation in primary mouse hepatocytes. (A) MKP-3 protein level in Stat3 overexpressed hepatocytes. (B) MKP-3 protein level in Stat3 knock-down hepatocytes. (C) Hepatocytes were treated with AZD1480 for the indicated time. Phosphorylation level of STAT3 and the protein level of MKP-3 were detected. (D and E) Hepatocytes were treated with leptin plus AZD1480 or vehicle for 1 hour. Phosphorylation level of STAT3 and protein level of MKP-3 were detected. (F) Protein lysate of primary mouse hepatocytes was immunoprecipitated with anti–MKP-3 antibody or normal mouse IgG. Protein levels of STAT3 and MKP-3 were detected. (G) Protein lysate of mouse liver was immunoprecipitated with anti–MKP-3 antibody or normal mouse IgG. Protein levels of STAT3 and MKP-3 were detected. (H) Protein lysate from wild-type primary hepatocytes, MKP-3–deficient primary hepatocytes, and AdMkp-3–infected MKP-3–deficient primary hepatocytes were immunoprecipitated with anti–MKP-3 antibody. Protein levels of STAT3 and MKP-3 were detected. (I) Primary hepatocytes were infected with AdMkp-3. Forty-eight hours later, cells were pretreated with 10 μmol/L cycloheximide for 30 minutes, then treated with cycloheximide plus leptin or vehicle for 1 hour. Protein lysate then was immunoprecipitated with anti–MKP-3 antibody. Phosphorylation levels and protein levels of STAT3, ERK, and MKP-3 were detected. (J) Primary hepatocytes were infected with AdMkp-3 for 48 hours. Cells were pretreated with 10 μmol/L cycloheximide for 30 minutes, then U0126 or vehicle for another 30 minutes, followed by treatment with 80 ng/mL leptin or vehicle plus U0126 or vehicle plus cycloheximide for 1 hour. Proteins were detected. (K) Primary hepatocytes were infected with AdMkp-3 or AdMkp-3 S159AS197A. Forty-eight hours later, cells were pretreated with 10 μmol/L cycloheximide for 30 minutes, followed by treatment with 80 ng/mL leptin or vehicle plus cycloheximide for 1 hour. Phosphorylation level of STAT3 and protein level of MKP-3 were detected. ∗P < .05 as marked. Results represent 1 of 3 independently performed experiments. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; IP, Immunoprecipitation; Lep, leptin; MKP-3 S159AS197A, MKP-3 mutant on Ser159 and Ser197 to Ala; MKP-3 WT, MKP-3 wild-type form; pERK, phospho-ERK1/2; pSTAT3, phospho-STAT3; Veh, vehicle.

Our previous study showed that MKP-3 mutant on Ser159 and Ser197 to Ala (MKP-3 S159AS197A) resists insulin/ERK-induced degradation.21 Similarly, MKP-3 S159AS197A also resisted leptin signaling–induced degradation (Figure 14K). These data indicate that leptin signaling might induce MKP-3 protein degradation via STAT3-stimulated ERK1/2 combination with MKP-3 in hepatocytes.

Discussion

Hyperglycemia could lead to type 2 diabetes and the related metabolic syndrome, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetic nephropathy, and diabetic foot. The current study shows that activation of hepatic leptin signaling could improve hyperglycemia and suppress gluconeogenesis. In addition, reduction of MKP-3 protein was required, at least partially, for hepatic leptin signaling to suppress gluconeogenesis. In addition, we discovered new regulatory pathways for MKP-3 protein expression, the leptin/STAT3 pathway, and the AMPK pathway.

Leptin has been administered to control hyperglycemia in human beings and animals.3, 4, 5,9,26, 27, 28 In addition, leptin restores glucose homeostasis mainly through its action on the central neural system.3,4,28, 29, 30 Although OBRb was found to be expressed in the liver,6, 7, 8 it is contradictory in the literature whether hepatic leptin signaling can suppress gluconeogenesis. Some studies have reported that hepatic leptin signaling suppressed gluconeogenesis,9,11,31,32 and some studies have indicated that hepatic leptin signaling stimulated it,10,33 while others have suggested that hepatic leptin signaling had no effect on gluconeogenesis.4,12 Here, we showed that activation of hepatic leptin signaling suppressed gluconeogenesis significantly both in vitro and in vivo.

The reason why different studies reached different conclusions might be because of the different models and the different types of treatment. In our study, primary mouse hepatocytes, liver cell lines, and db/db mice were used, so that the effect of leptin signaling from central nervous system and other peripheral tissues was eliminated. Our findings are consistent with previous studies with primary hepatocytes and isolated rat liver, which showed that leptin treatment reduced gluconeogenesis.9,31 In the studies that mentioned an increase in hepatic gluconeogenesis by leptin administration, the investigators used normal animals with normal central leptin signaling.10,33 Reports that declared that hepatic leptin signaling had no effect on gluconeogenesis only inactivated leptin signaling in the liver.4,12 Our study also showed similar results that knock-down of Obr in wild-type mouse liver did not change the blood glucose level or the expression of hepatic gluconeogenic genes. This might be because Obrb expression level is low in liver, and central leptin signaling could act on the liver.30,34 Thus, hepatic leptin signaling might be shut out by central leptin signaling in normal animals. Furthermore, our study also showed that only activation of leptin signaling in DIO mouse liver improved insulin resistance and decreased blood glucose levels, which might be because central leptin signaling was impaired in obese individuals. Therefore, hepatic leptin signaling might not be essential for systemic glucose homeostasis, but activation of hepatic leptin signaling is sufficient to suppress liver gluconeogenesis under leptin-resistance conditions. A similar situation was reported that ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus leptin signaling is sufficient, but not necessary, to reduce hepatic gluconeogenesis in diabetic mice.35

It is interesting that Perry et al36 suggested that leptin replacement therapy for diabetic mice suppressed hepatic gluconeogenesis by inhibiting adipocyte lipolysis, which resulted in a reduction of glucogenic substrate in the liver, instead of a reduction of hepatic gluconeogenic gene expression. In a recent study, it was stated that during prolonged starvation, physiologic replacement of plasma leptin concentrations might inhibit hepatic gluconeogenesis through reduction in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activity, while supraphysiologic plasma leptin concentrations stimulated white adipose tissue lipolysis and resulted in an increased hepatic gluconeogenesis rate and hyperglycemia.37 Zhao et al38 also suggested that a partial reduction of plasma leptin decreased glycemia in obese mice. These reports indicate that excessively high levels of systemic leptin administration might not be suitable for hyperglycemia treatment. Our results specifically suggest that activation of hepatic leptin signaling might help to improve hyperglycemia under leptin-resistance conditions. Further study will be conducted to explore the reason for the low expression level of OBRb in liver, and to find a way to increase endogenous hepatic OBRb expression.

STAT3 is important for the activation of leptin signaling on metabolism.39 Our study indicated an alternate pathway for hepatic leptin signaling suppressing gluconeogenesis, the STAT3/MKP-3 pathway. MKP-3 has been reported to promote hepatic gluconeogenesis by dephosphorylating FOXO1 and stimulating the expression of Pgc1a.19 Here, we found that the MKP-3 protein level was decreased by leptin signaling in both hepatocytes and obese mouse liver. In addition, the phosphorylation level of FOXO1 on S256 was increased and the expression level of Pgc1a was decreased by OBRb overexpression in the liver of db/db mice. These data suggest that MKP-3 might play a role in hepatic leptin signaling suppressing gluconeogenesis. Further results showed that Mkp-3 deficiency eliminated the suppressive effect of leptin signaling on gluconeogenesis in primary hepatocytes, while MKP-3 overexpression reversed leptin signaling decreasing gluconeogenesis in hepatocytes. These data indicate that MKP-3 is involved in the process of hepatic leptin signaling reducing gluconeogenesis.

The expression of MKP-3 protein is regulated by many hormones at the post-transcriptional level, including insulin,21 glucocorticoid,22 and insulin growth factor 1.20 Here, we found that adipokine leptin suppressed the expression of MKP-3 protein in both hepatocytes and mouse liver, while the mRNA level of MKP-3 was not changed. These data indicate that leptin signaling might down-regulate MKP-3 in a post-translational manner. Similar to our previous report,21 the mutant of MKP-3 on Ser159 and Ser197 to Ala resisted leptin signaling–induced degradation. This indicates that leptin signaling might induce MKP-3 degradation by phosphorylating it on Ser159 and Ser197.

Hepatic AMPK can be activated by leptin through the sympathetic nervous system.14 Our study also showed that overexpression of OBRb can activate AMPK in both hepatocytes and mouse liver. In addition, activation of AMPK suppressed the protein expression of MKP-3 in hepatocytes. AMPK is a serine kinase that can induce the phosphorylation of many proteins on serine, such as ACC1 and hormone-sensitive lipase.40,41 MKP-3 can be phosphorylated on Ser159 and Ser197, and then be degraded in a ubiquitin pathway.21,42 Thus, AMPK might regulate the protein expression of MKP-3 by inducing serine phosphorylation. However, the exact mechanism will be explored in a further study. It is interesting that leptin treatment did not induce the phosphorylation of AMPKα in hepatocytes. This might be because leptin treatment is not as strong as OBRb overexpression in hepatocytes. In addition, our study showed that inactivation of AMPK could not reverse the MKP-3 protein level that was decreased by leptin signaling.

STAT3 is considered a transcriptional factor.43 However, our results showed that overexpression of Stat3 decreased the MKP-3 protein level in hepatocytes, while knock-down of Stat3 increased it. In addition, inhibition of STAT3 activity by a JAK2 inhibitor could reverse the MKP-3 protein level that was reduced by leptin signaling. In addition, STAT3 could be co-immunoprecipitated by MKP-3 antibody. A recent study reported that STAT3 could bind to both transforming growth factor-β–activated kinase 1 (TAK1) and TAK1-Nemo-like kinase as a scaffold, and then TAK1 could phosphorylate TAK1-Nemo-like kinase.44 Our study found that leptin signaling induced a combination of MKP-3 with STAT3 and ERK1/2, while inhibition of ERK activity eliminated the effect of leptin on reducing the MKP-3 protein level. ERK1/2 can phosphorylate MKP-3 and induce its degradation through a ubiquitin pathway.21 Thus, STAT3 might mediate leptin signaling to induce MKP-3 protein degradation by enhancing the combination of MKP-3 and ERK1/2 as a scaffold.

In summary, our study shows that hepatic leptin signaling can improve hyperglycemia by suppressing gluconeogenesis in obese individuals, and this is at least partially through STAT3-mediated MKP-3 protein degradation via enhanced MKP-3 and ERK1/2 combination. Thus, enhancement of hepatic Obrb expression might be a strategy for hyperglycemia therapy in obese and type 2 diabetic individuals.

Methods

Animal Studies

The animal study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Sichuan Agricultural University. All animal studies were performed according to the Use and Care Instruction of Laboratory Animals of China. Three-week-old wild-type male mice and 7-week-old db/db male mice (C57BL/6J background) were obtained from GemPharmatech (Nanjing, China). Mice were maintained in a pathogen-free room at a temperature of 22°C, with humidity of 60%, with a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle, and were allowed free access to water and standard diet (Dashuo, Chengdu, China).

Twelve db/db mice at the age of 8 weeks were divided randomly into 2 groups with similar body weight and blood glucose levels. One group was administered AdOBRb by tail vein–injection, while the other group received adenovirus cloned with green fluorescent protein (AdGFP) at a dose of 2 × 1011 virus particles per mouse. An insulin tolerance test (ITT) was performed on day 5 of adenovirus injection and a glucose tolerance test (GTT) was performed with the same mice on day 9 of adenovirus injection. For blood and tissue collection, ten 8-week-old db/db male mice were administered AdGFP or AdOBRb. The feeding blood glucose level was measured on day 5, and the fasting blood glucose level was measured on day 6 of adenovirus administration. Six days after adenovirus administration, mice were killed after an overnight fast. Serum was collected for insulin and leptin measurement. Livers rapidly were dissected, weighed, and frozen in liquid nitrogen, and were stored at -80°C for further analysis.

For the DIO mice study, wild-type male mice were put on a high-fat diet (60% calories from fat; Research Diet, New Brunswick, NJ) from 4 weeks of age. After 16 weeks of high-fat diet feeding, mice were divided randomly into 2 groups. One group were administered AdObrb by tail vein–injection, while the other group received AdGFP at a dose of 2 × 1011 virus particles per mouse. The ITT and GTT studies and blood and tissue collection were performed the same as for the db/db mice.

ITT and GTT

ITT and GTT were performed as previously reported.45 For ITT, mice were deprived of food in the morning. Six hours later, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 U/kg recombinant human insulin (Novonordisk, Beijing, China). Blood glucose levels were measured at 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, and 90 minutes after insulin injection with blood glucose strips (Yicheng Biological Electronic Technology Co, Ltd, Beijing, China). For GTT, mice were deprived of food for 14 hours, followed by an intraperitoneal injection of 0.5 g/kg dextrose (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Blood glucose levels were measured at 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, and 90 minutes after dextrose injection.

Cell Culture and Treatment

Mouse hepatoma Hepa 1–6 cells (provided by Dr Gökhan Hotamisligil, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA), human hepatoma HepG2 cells (provided by Dr Bo Xiao, Sichuan University, Chengdu, Sichuan, China), and primary mouse hepatocytes were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), supplied with 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermofisher), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Thermofisher) at 37°C with 5% CO2. Primary mouse hepatocytes were isolated by infusing mouse liver with collagenase buffer as previously reported.46 The Mkp-3 knockout mice and the littermate wild-type mice used for primary hepatocyte isolation were established in our laboratory as previously reported.46

Primary mouse hepatocytes, Hepa 1-6 cells, and HepG2 cells were seeded in a 12-well plate at a density of 4 × 105 cells/well. When 80% confluence was reached the next day, cells were infected with AdGFP or AdOBRb adenoviruses at a multiplicity of infection of 50. For the Obr knocking down study, primary mouse hepatocytes were infected with AdshLacZ or AdshObr at a multiplicity of infection of 100. Cells then were treated with leptin or other chemicals 48 hours after adenovirus infection.

Before chemical treatment, cells were incubated with serum-free DMEM for 14 hours, followed by incubation with serum-free DMEM containing 80 ng/mL leptin (R&D, Minneapolis, MN), 1 mmol/L AICAR (Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX), 0.5 mmol/L Metformin (Selleck Chemicals), 10 μmol/L Compound C (Selleck Chemicals), 1 μmol/L AZD 1480 (Selleck Chemicals), or 100 μmol/L U0126 (Selleck Chemicals) for the indicated time. Cells then were harvested for further analysis. All cell studies with OBRb/Obrb overexpression or Obrb knock-down were performed in the presence of 80 ng/mL leptin in the medium.

Construction and Purification of Adenovirus

Adenovirus construction and purification were performed as previously reported.21 The coding sequences for human OBRb, mouse Obrb, and mouse Stat3 were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), cloned into the entry vector (Thermofisher), and then recombined into the Gateway-based pAd-CMV DEST vector (Thermofisher) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To construct adenoviral vectors expressing interfering shRNAs against mouse Obr or Stat3, 3 short hairpin oligonucleotides and complementary strands for each gene were designed. Briefly, the top- and bottom-strand oligonucleotides were annealed and ligated into the Gateway-based pENTR/U6 vector (Thermofisher), and then were recombined with the Gateway based pAd-BLOCK-iT DEST vector (Thermofisher) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Gene knocking down efficiency was tested in cultured Hepa 1–6 cells. The sequence for Obr shRNA used in this study was GCTTCAGTAGTGAAGGCTTCA, and for Stat3 shRNA was CCTGAGTTGAATTATCAGCTTC. The sequence of GCTACACAAATCAGCGATTT for shLacZ was used as the control. Amplification of recombinant adenovirus was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions using HEK 293A cells (Thermofisher). Adenoviruses were purified using the ViraBind Adenovirus Purification Kit (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA), and quantified using the Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) protein assay kit. AdMkp-3 S159AS197A adenovirus was made previously.21 The adenovirus constitutively active form of AMPKα1 and AdDN-AMPKα1 were provided by Dr Mengwei Zang (Boston University, Boston, MA).47

Glucose Output Assay

The glucose output assay was performed as previous reported.21 Hepatocytes were washed 3 times with phosphate-buffered saline and were incubated in serum-free DMEM containing 0.5 mmol/L 8-bromo-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) for 5 hours. Cells then were incubated in 0.5 mL/well of phenol red–free, glucose-free DMEM (Sigma) containing 2 mmol/L pyruvate, 20 mmol/L lactate, and 1 mmol/L 8-bromo-cAMP, with 80 ng/mL leptin or vehicle. Medium was collected 3 hours later and subjected to glucose measurement using the Glucose Assay Kit (Sigma). Cells were lysed and the protein concentration was measured. The glucose production was normalized with cellular protein content.

RNA Extraction and Real-Time PCR

RNA extraction and real-time PCR were performed as previously reported.45 For cultured cells, 500 μL TRIzol Reagent (Sigma) was added to each well to lysis cells. For tissues, 50 mg liver powder was homogenized in 1 mL TRIzol Reagent. The lysates then were transferred to 1.5-mL Eppendorf tubes. RNA was extracted in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quality was assessed by agarose gel and the concentration was measured with a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop 2000; Thermofisher Scientific). A total of 1 μg RNA was reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) with a reverse-transcription PCR kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermofisher Scientific). Real-time PCR was performed on a quantitative PCR machine (7900HT; ABI, Carlsbad, CA) with Power SYBR Green Reverse-Transcription PCR reagents (Bio-Rad). The following reagents were used for each reaction: forward primer, 300 nmol/L; reverse primer, 300 nmol/L; and cDNA sample, 20 ng. The conditions used for PCR were as follows: 95°C for 10 minutes for 1 cycle, and then 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds, followed by 60°C for 1 minute. The real-time PCR data were analyzed by the 2-delta delta CT method with β-actin (Actb) as the reference gene. The sequences of the primers are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer Sequences for Real-Time PCR

| Gene name | Forward, 5’>3’ | Reverse, 5’>3’ |

|---|---|---|

| Actb | GGCTGTATTCCCCTCCATCG | CCAGTTGGTAACAATGCCATGT |

| Pepck1 | CGCTGGATGTCGGAAGAGG | GGCGAGTCTGTCAGTTCAATAC |

| G6pc | CGACTCGCTATCTCCAAGTGA | GTTGAACCAGTCTCCGACCA |

| Pgc1a | TATGGAGTGACATAGAGTGTGCT | CCACTTCAATCCACCCAGAAAG |

| Mkp-3 | TGCGGGCGAGTTCAAATACA | AGCAATGCACCAGGACACCA |

| Obr/OBRa | GGATATTGGAGTAATTGGAGCA | GATTTCCCACATCTTCTGACCA |

| Obra | GTTGTTTTGGGACGATGTTCCA | TGGGTTCATCTGTAGTGGTCATG |

| Obrb | GACGATGTTCCAAACCCCAAGA | GCTCCAGAAGAAGAGGACCAAA |

| Obrc | GTTGTTTTGGGACGATGTTCCA | TGGCATCTAAACTGCAACCTTAG |

| ACTB | TCACCATGGATGATGATATCGC | ATAGGAATCCTTCTGACCCATGC |

| PEPCK1 | TTGAGAAAGCGTTCAATGCCA | CACGTAGGGTGAATCCGTCAG |

| G6PC | GTGTCCGTGATCGCAGACC | GACGAGGTTGAGCCAGTCTC |

| PGC1A | TGAAGACGGATTGCCCTCATT | GCTGGTGCCAGTAAGAGCTT |

Primers for Obr and OBR shared the same sequences; gene names with capital letters refer to human genes.

Absolute Quantitative PCR

Mouse Obra, Obrb, and Obrc fragments were amplified by PCR with the respective PCR primers (Figure 1A and Table 1), and were cloned into pBM23 plasmid (BioMed, Beijing, China). Plasmids of pBM23_Obra, pBM23_Obrb, and pBM23_Obrc then were used as the standards for quantitative real-time PCR. Each 1 μg mRNA from mouse liver, lung, brain, and primary mouse hepatocytes was reverse-transcribed into cDNA. Quantitative real-time PCR then was performed.

Western Blot Analysis

For the preparation of protein lysates for cells, 120 μL ice-cold cell lysis buffer (50 mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.4, 1% Triton X-100, 100 mmol/L NaF, 50 mmol/L sodium pyrophosphate, 10 mmol/L Na3VO4, 25 mmol/L sodium-β-glycerophosphate, 0.5 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail; Roche, Mannheim, Germany) was added to each well. Cells then were scratched using a cell scraper. For livers, 50 mg tissue powder was homogenized in 1 mL ice-cold cell lysis buffer with a homogenizer. The protein lysate was centrifuged at 12,000 × g at 4°C for 30 minutes. The concentration of protein in the supernatant was measured using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermofisher Scientific). A total of 60 μg protein was used to prepare for an electrophoresis sample with loading buffer (Bio-Rad) for each sample. Proteins were separated on 10% polyacrylamide gel, and then were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad). The membranes were blocked in 1% bovine serum albumin/1 × tris buffered saline with tween (TBST) for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by incubation with the appropriate primary antibodies (1 μg/mL) for overnight. Antibodies to phospho-STAT3 (Y705), STAT3, phospho-AMPKα (T172), AMPKα, phospho-ERK1/2 (T202/Y204), ERK, phospho-AKT (T308), phospho-AKT (S473), AKT, phospho-ACC1 (S79), ACC1, Myc, and tubulin were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA); MKP-3 antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Secondary antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Protein signals were detected by ECL Western blot detection reagent (Bio-Rad). Blots were quantified with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Measures of Serum Insulin and Leptin

Contents of insulin (ALPCO, Salem, NH) and leptin (Solarbio, Beijing, China) in the fasting serum of AdOBRb-injected db/db mice and AdObrb-injected DIO mice were measured using the respective enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions, as previously reported.46

Co-immunoprecipitation

A co-immunoprecipitation study was performed as previously reported.46 Briefly, cell lysate containing 1 mg protein was precleared with 20 μL Protein G PLUS-Agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 hour at 4°C. Then, supernatants were incubated with 1 μg MKP-3 antibody or the control IgG at 4°C for another 1 hour, followed by incubation with 20 μL Protein G PLUS-agarose at 4°C for overnight. The beads then were washed 5 times using cell lysis buffer, followed by boiling in 2× loading buffer at 95°C to release proteins. The samples then were assessed by Western blot.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using SAS 9.3 software (Cary, NC). An independent t test was used to compare the difference between 2 groups, while repeated-measures analysis of variance was used to analyze the statistical difference of GTT and ITT. Results were presented as means ± SE. Statistical significance was determined at P < .05.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Gökhan Hotamisligil from Harvard School of Public Health for providing the Hepa 1–6 cell line, Dr Bo Xiao from Sichuan University for providing the HepG2 cell line, and Dr Mengwei Zang from Boston University for providing the adenovirus constitutively active form of AMPKα1 and AdDN-AMPKα1.

CRediT Authorship Contributions

Xiaohua Huang (Conceptualization: Equal; Data curation: Lead; Formal analysis: Equal; Investigation: Lead; Methodology: Equal; Validation: Supporting; Visualization: Equal; Writing – original draft: Equal)

Qin He (Data curation: Equal; Methodology: Supporting)

Heng Zhu (Investigation: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting)

Zhengfeng Fang (Investigation: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting; Validation: Supporting; Visualization: Supporting)

Lianqiang Che (Formal analysis: Supporting; Investigation: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting)

Yan Lin (Formal analysis: Supporting; Investigation: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting)

Shengyu Xu (Formal analysis: Supporting; Investigation: Supporting)

Yong Zhuo (Data curation: Supporting; Investigation: Supporting)

Lun Hua, PhD (Investigation: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting; Validation: Supporting; Visualization: Supporting)

Jianping Wang (Investigation: Supporting; Validation: Supporting; Visualization: Supporting)

Yuanfeng Zou (Investigation: Supporting; Visualization: Supporting)

Chao Huang (Data curation: Supporting; Formal analysis: Supporting; Software: Equal; Validation: Supporting)

Lixia Li (Investigation: Supporting; Visualization: Supporting)

Haiyan Xu (Supervision: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Equal)

De Wu (Project administration: Supporting; Supervision: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Equal)

Bin Feng (Conceptualization: Lead; Data curation: Equal; Formal analysis: Supporting; Funding acquisition: Lead; Investigation: Supporting; Project administration: Lead; Resources: Lead; Supervision: Lead; Validation: Equal; Writing – original draft: Lead)

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding This study was supported by the National Science Foundation (31900834) and the 111 Project (D17015). Also supported by the Thousand Talent Program from Sichuan Province of China and the Dr. George A. Bray Research Scholars Award from Brown University.

References

- 1.Basu R., Chandramouli V., Dicke B., Landau B., Rizza R. Obesity and type 2 diabetes impair insulin-induced suppression of glycogenolysis as well as gluconeogenesis. Diabetes. 2005;54:1942–1948. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.7.1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Puigserver P., Rhee J., Donovan J., Walkey C.J., Yoon J.C., Oriente F., Kitamura Y., Altomonte J., Dong H., Accili D., Spiegelman B.M. Insulin-regulated hepatic gluconeogenesis through FOXO1-PGC-1alpha interaction. Nature. 2003;423:550–555. doi: 10.1038/nature01667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berglund E.D., Vianna C.R., Donato J., Jr., Kim M.H., Chuang J.C., Lee C.E., Lauzon D.A., Lin P., Brule L.J., Scott M.M., Coppari R., Elmquist J.K. Direct leptin action on POMC neurons regulates glucose homeostasis and hepatic insulin sensitivity in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1000–1009. doi: 10.1172/JCI59816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denroche H.C., Levi J., Wideman R.D., Sequeira R.M., Huynh F.K., Covey S.D., Kieffer T.J. Leptin therapy reverses hyperglycemia in mice with streptozotocin-induced diabetes, independent of hepatic leptin signaling. Diabetes. 2011;60:1414–1423. doi: 10.2337/db10-0958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cummings B.P., Bettaieb A., Graham J.L., Stanhope K.L., Dill R., Morton G.J., Haj F.G., Havel P.J. Subcutaneous administration of leptin normalizes fasting plasma glucose in obese type 2 diabetic UCD-T2DM rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:14670–14675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107163108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mittenbuhler M.J., Sprenger H.G., Gruber S., Wunderlich C.M., Kern L., Bruning J.C., Wunderlich F.T. Hepatic leptin receptor expression can partially compensate for IL-6Ralpha deficiency in DEN-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Metab. 2018;17:122–133. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghilardi N., Ziegler S., Wiestner A., Stoffel R., Heim M.H., Skoda R.C. Defective STAT signaling by the leptin receptor in diabetic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:6231–6235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szanto I., Kahn C.R. Selective interaction between leptin and insulin signaling pathways in a hepatic cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2355–2360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050580497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderwald C., Muller G., Koca G., Furnsinn C., Waldhausl W., Roden M. Short-term leptin-dependent inhibition of hepatic gluconeogenesis is mediated by insulin receptor substrate-2. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:1612–1628. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.7.0867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu L., Karkanias G.B., Morales J.C., Hawkins M., Barzilai N., Wang J., Rossetti L. Intracerebroventricular leptin regulates hepatic but not peripheral glucose fluxes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:31160–31167. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.47.31160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang M.Y., Chen L., Clark G.O., Lee Y., Stevens R.D., Ilkayeva O.R., Wenner B.R., Bain J.R., Charron M.J., Newgard C.B., Unger R.H. Leptin therapy in insulin-deficient type I diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4813–4819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909422107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levi J., Huynh F.K., Denroche H.C., Neumann U.H., Glavas M.M., Covey S.D., Kieffer T.J. Hepatic leptin signalling and subdiaphragmatic vagal efferents are not required for leptin-induced increases of plasma IGF binding protein-2 (IGFBP-2) in ob/ob mice. Diabetologia. 2012;55:752–762. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2426-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao Q., Mak K.M., Ren C., Lieber C.S. Leptin stimulates tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 in human hepatic stellate cells: respective roles of the JAK/STAT and JAK-mediated H2O2-dependent MAPK pathways. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4292–4304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308351200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyamoto L., Ebihara K., Kusakabe T., Aotani D., Yamamoto-Kataoka S., Sakai T., Aizawa-Abe M., Yamamoto Y., Fujikura J., Hayashi T., Hosoda K., Nakao K. Leptin activates hepatic 5'-AMP-activated protein kinase through sympathetic nervous system and alpha1-adrenergic receptor: a potential mechanism for improvement of fatty liver in lipodystrophy by leptin. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:40441–40447. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.384545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inoue H., Ogawa W., Ozaki M., Haga S., Matsumoto M., Furukawa K., Hashimoto N., Kido Y., Mori T., Sakaue H., Teshigawara K., Jin S., Iguchi H., Hiramatsu R., LeRoith D., Takeda K., Akira S., Kasuga M. Role of STAT-3 in regulation of hepatic gluconeogenic genes and carbohydrate metabolism in vivo. Nat Med. 2004;10:168–174. doi: 10.1038/nm980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inoue H., Ogawa W., Asakawa A., Okamoto Y., Nishizawa A., Matsumoto M., Teshigawara K., Matsuki Y., Watanabe E., Hiramatsu R., Notohara K., Katayose K., Okamura H., Kahn C.R., Noda T., Takeda K., Akira S., Inui A., Kasuga M. Role of hepatic STAT3 in brain-insulin action on hepatic glucose production. Cell Metab. 2006;3:267–275. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang B., Hsu S.H., Frankel W., Ghoshal K., Jacob S.T. Stat3-mediated activation of microRNA-23a suppresses gluconeogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma by down-regulating glucose-6-phosphatase and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha. Hepatology. 2012;56:186–197. doi: 10.1002/hep.25632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foretz M., Ancellin N., Andreelli F., Saintillan Y., Grondin P., Kahn A., Thorens B., Vaulont S., Viollet B. Short-term overexpression of a constitutively active form of AMP-activated protein kinase in the liver leads to mild hypoglycemia and fatty liver. Diabetes. 2005;54:1331–1339. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.5.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu Z., Jiao P., Huang X., Feng B., Feng Y., Yang S., Hwang P., Du J., Nie Y., Xiao G., Xu H. MAPK phosphatase-3 promotes hepatic gluconeogenesis through dephosphorylation of forkhead box O1 in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3901–3911. doi: 10.1172/JCI43250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bermudez O., Marchetti S., Pages G., Gimond C. Post-translational regulation of the ERK phosphatase DUSP6/MKP3 by the mTOR pathway. Oncogene. 2008;27:3685–3691. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1211040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng B., Jiao P., Yang Z., Xu H. MEK/ERK pathway mediates insulin-promoted degradation of MKP-3 protein in liver cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;361:116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feng B., He Q., Xu H. FOXO1-dependent up-regulation of MAP kinase phosphatase 3 (MKP-3) mediates glucocorticoid-induced hepatic lipid accumulation in mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;393:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cui H., Lopez M., Rahmouni K. The cellular and molecular bases of leptin and ghrelin resistance in obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13:338–351. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Enriori P.J., Evans A.E., Sinnayah P., Jobst E.E., Tonelli-Lemos L., Billes S.K., Glavas M.M., Grayson B.E., Perello M., Nillni E.A., Grove K.L., Cowley M.A. Diet-induced obesity causes severe but reversible leptin resistance in arcuate melanocortin neurons. Cell Metab. 2007;5:181–194. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bouhidel O., Pons S., Souktani R., Zini R., Berdeaux A., Ghaleh B. Myocardial ischemic postconditioning against ischemia-reperfusion is impaired in ob/ob mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H1580–H1586. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00379.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Javor E.D., Cochran E.K., Musso C., Young J.R., Depaoli A.M., Gorden P. Long-term efficacy of leptin replacement in patients with generalized lipodystrophy. Diabetes. 2005;54:1994–2002. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.7.1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paz-Filho G., Mastronardi C.A., Licinio J. Leptin treatment: facts and expectations. Metabolism. 2015;64:146–156. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2014.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hidaka S., Yoshimatsu H., Kondou S., Tsuruta Y., Oka K., Noguchi H., Okamoto K., Sakino H., Teshima Y., Okeda T., Sakata T. Chronic central leptin infusion restores hyperglycemia independent of food intake and insulin level in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. FASEB J. 2002;16:509–518. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0164com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamohara S., Burcelin R., Halaas J.L., Friedman J.M., Charron M.J. Acute stimulation of glucose metabolism in mice by leptin treatment. Nature. 1997;389:374–377. doi: 10.1038/38717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pocai A., Morgan K., Buettner C., Gutierrez-Juarez R., Obici S., Rossetti L. Central leptin acutely reverses diet-induced hepatic insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2005;54:3182–3189. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.11.3182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raman P., Donkin S.S., Spurlock M.E. Regulation of hepatic glucose metabolism by leptin in pig and rat primary hepatocyte cultures. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;286:R206–R216. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00340.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toyoshima Y., Gavrilova O., Yakar S., Jou W., Pack S., Asghar Z., Wheeler M.B., LeRoith D. Leptin improves insulin resistance and hyperglycemia in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4024–4035. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rossetti L., Massillon D., Barzilai N., Vuguin P., Chen W., Hawkins M., Wu J., Wang J. Short term effects of leptin on hepatic gluconeogenesis and in vivo insulin action. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27758–27763. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burgos-Ramos E., Canelles S., Rodriguez A., Gomez-Ambrosi J., Frago L.M., Chowen J.A., Fruhbeck G., Argente J., Barrios V. Chronic central leptin infusion modulates the glycemia response to insulin administration in male rats through regulation of hepatic glucose metabolism. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;415:157–172. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meek T.H., Matsen M.E., Dorfman M.D., Guyenet S.J., Damian V., Nguyen H.T., Taborsky G.J., Jr., Morton G.J. Leptin action in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus is sufficient, but not necessary, to normalize diabetic hyperglycemia. Endocrinology. 2013;154:3067–3076. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perry R.J., Zhang X.M., Zhang D., Kumashiro N., Camporez J.P., Cline G.W., Rothman D.L., Shulman G.I. Leptin reverses diabetes by suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Nat Med. 2014;20:759–763. doi: 10.1038/nm.3579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perry R.J., Wang Y., Cline G.W., Rabin-Court A., Song J.D., Dufour S., Zhang X.M., Petersen K.F., Shulman G.I. Leptin mediates a glucose-fatty acid cycle to maintain glucose homeostasis in starvation. Cell. 2018;172:234–248. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao S., Zhu Y., Schultz R.D., Li N., He Z., Zhang Z., Caron A., Zhu Q., Sun K., Xiong W., Deng H., Sun J., Deng Y., Kim M., Lee C.E., Gordillo R., Liu T., Odle A.K., Childs G.V., Zhang N., Kusminski C.M., Elmquist J.K., Williams K.W., An Z., Scherer P.E. Partial leptin reduction as an insulin sensitization and weight loss strategy. Cell Metab. 2019;30:706–719. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buettner C., Pocai A., Muse E.D., Etgen A.M., Myers M.G., Jr., Rossetti L. Critical role of STAT3 in leptin's metabolic actions. Cell Metab. 2006;4:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fullerton M.D., Galic S., Marcinko K., Sikkema S., Pulinilkunnil T., Chen Z.P., O'Neill H.M., Ford R.J., Palanivel R., O'Brien M., Hardie D.G., Macaulay S.L., Schertzer J.D., Dyck J.R., van Denderen B.J., Kemp B.E., Steinberg G.R. Single phosphorylation sites in Acc1 and Acc2 regulate lipid homeostasis and the insulin-sensitizing effects of metformin. Nat Med. 2013;19:1649–1654. doi: 10.1038/nm.3372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watt M.J., Holmes A.G., Pinnamaneni S.K., Garnham A.P., Steinberg G.R., Kemp B.E., Febbraio M.A. Regulation of HSL serine phosphorylation in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;290:E500–E508. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00361.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marchetti S., Gimond C., Chambard J.C., Touboul T., Roux D., Pouyssegur J., Pages G. Extracellular signal-regulated kinases phosphorylate mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase 3/DUSP6 at serines 159 and 197, two sites critical for its proteasomal degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:854–864. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.2.854-864.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu H., Lee H., Herrmann A., Buettner R., Jove R. Revisiting STAT3 signalling in cancer: new and unexpected biological functions. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:736–746. doi: 10.1038/nrc3818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kojima H., Sasaki T., Ishitani T., Iemura S., Zhao H., Kaneko S., Kunimoto H., Natsume T., Matsumoto K., Nakajima K. STAT3 regulates Nemo-like kinase by mediating its interaction with IL-6-stimulated TGFbeta-activated kinase 1 for STAT3 Ser-727 phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4524–4529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500679102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feng B., Huang X., Jiang D., Hua L., Zhuo Y., Wu D. Endoplasmic reticulum stress inducer tunicamycin alters hepatic energy homeostasis in mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:E1710. doi: 10.3390/ijms18081710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feng B., Jiao P., Helou Y., Li Y., He Q., Walters M.S., Salomon A., Xu H. Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase 3 (MKP-3)-deficient mice are resistant to diet-induced obesity. Diabetes. 2014;63:2924–2934. doi: 10.2337/db14-0066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li Y., Xu S., Mihaylova M.M., Zheng B., Hou X., Jiang B., Park O., Luo Z., Lefai E., Shyy J.Y., Gao B., Wierzbicki M., Verbeuren T.J., Shaw R.J., Cohen R.A., Zang M. AMPK phosphorylates and inhibits SREBP activity to attenuate hepatic steatosis and atherosclerosis in diet-induced insulin-resistant mice. Cell Metab. 2011;13:376–388. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]