Abstract

Xenorhabdus are symbionts of soil entomopathogenic nematodes of the genus Steinernema presenting two distinct forms in their life cycle, and can produce a broad range of bioactive compounds. In this study, a novel Xenorhabdus stockiae strain HN_xs01 was isolated from a soil sample via an entrapment method using Galleria melonella nematodes. The supernatants of strain HN_xs01 exhibited antimicrobial properties against Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, and insecticidal properties against Helicoverpa armigera larvae, and antitumor properties as well. Moreover, three linear rhabdopeptides (1, 2 and 3) were identified from strain HN_xs01 using nuclear magnetic resonance analysis, which exhibited significant cytotoxic activity against the human epithelial carcinoma cell line A431 and the human chronic myelogenous leukemia cell line K562. Some bacteria have been reported to colonize the tumor region, and we determined that HN_xs01 could grow in tumor xenografts in this study. HN_xs01 invaded and replicated in B16 melanoma cells grafted into C57BL/6 mice, resulting in tumor inhibition. Moreover, strain HN_xs01 not only merely aggregated in the tumor environment, but also prevented pulmonary metastasis. It caused fragmentation of vessels and cell apoptosis, which contributed to its antitumor effect. In conclusion, X. stockiae HN_xs01 is a novel tumor-targeting strain with potential applications in medicinal and agricultural fields.

Keywords: Xenorhabdus stockiae, HN_xs01, biological activities, tumortargeting, entomopathogenic nematodes

Introduction

The genus Xenorhabdus is a mutualistic symbiont of entomopathogenic nematodes (EPNs) of the genus Steinernema. Xenorhabdus spp. are a motile, Gram-negative, entomopathogenic bacteria that present two distinct forms, primary and secondary form, in their life cycle. The primary form of Xenorhabdus is retained in the intestine of infective stage nematodes, contributes to faster and greater reproduction of nematodes, and is less stable than the secondary form, which is significant for the primary form in the monoxenic culture of nematodes in vitro (Thomas and George, 1979; Akhurst, 1980). The infective juveniles invade insect larvae through natural openings and release bacteria from their intestine to the host’s hemocoel, resulting in the production of insecticidal proteins and inhibitors by overcoming the insect immune system and countering the effect of various antibiotics by inhibiting other microorganisms. Then, the bacteria multiply rapidly and provide nutrients for the reproduction of the nematodes (Sicard et al., 2006; Singh et al., 2015). Subsequently, nematode progeny associated with Xenorhabdus emerge from the cadaver to seek a new host.

Multiple compounds from various Xenorhabdus strains have been isolated and identified. These compounds, including proteinaceous and non-proteinaceous compounds, have diverse chemical structures and a wide range of bioactivities, such as antibacterial, antifungal, insecticidal, nematicidal, and cytotoxic properties (Mcinerney et al., 1991; Samaliev et al., 2000; Brown et al., 2006; Gualtieri et al., 2009; Qin et al., 2013; Fang et al., 2014). In addition, multiple secondary metabolites produced by Xenorhabdus are mostly synthesized by multienzyme thiotemplate mechanisms, such as nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) and polyketide synthases (PKSs) (Staunton and Weissman, 2001; Strieker et al., 2010). Rhabdopeptides biosynthesized by NRPSs are very common in Xenorhabdus species, and show cytotoxic and antiprotozoal activities that might be involved in the protection of the insect cadaver (Bozhuyuk et al., 2016; Cai et al., 2017; Bi et al., 2018). Several Xenorhabdus species have been revealed to contain about twenty biosynthetic gene clusters, most of which are uncharacterized (Chaston et al., 2011; Cimen et al., 2022). Therefore, Xenorhabdus spp. could be a promising source of natural products.

The application of bacteria in cancer therapy has been a research focus for many years. Cancer therapy studies over the last 2 decades have revealed that several genera of bacteria, such as Clostridium novyi-NT, non-pathogenic Salmonella typhimurium, Escherichia coli Nissle 1917, and Bifidobacterium, can efficiently colonize and proliferate in certain tumors, resulting in the suppression of tumor growth (Tang et al., 2009; Yu et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012; Roberts et al., 2014). The mechanisms by which these bacteria can target different intratumoral regions include chemotaxis, preferential growth, and hypoxic germination. Obligate anaerobes including Clostridium and Bifidobacterium do not survive in oxygenated regions but are highly effective at accumulating in large hypoxic regions of tumors (Agrawal et al., 2004; Tang et al., 2009). Facultative anaerobes such as Salmonella and E. coli Nissle 1917 utilize chemotaxis to migrate towards compounds produced by tumors, leading to their preferential growth of these bacteria in tumor-specific microenvironments (Jean et al., 2008). Genetically modified strains coupled with antitumor substances, DNA fragments, or enzymatic drug activation are rapidly being developed to augment the efficacy of bacteria in antitumor therapy (Jean et al., 2008). Moreover, the development of new bacteria for cancer therapy is an urgent strategy.

X. stockiae is a symbiotic partner of Steinernema siamkayai, first described in 2006 (Tailliez et al., 2006). In this study, the bacterial strain HN_xs01, identified as X. stockiae, was isolated from soil samples. The anti-tumor effect of HN_xs01 exhibiting potent bioactivities on the mice bearing B16 mouse melanoma have been investigated in vivo. The strain HN_xs01 efficiently colonized the tumor region and suppressed the growth of tumors via intravenous and intratumoral injection, which laid an important foundation for development of Xenorhabdus species for cancer therapy.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strain isolation

Xenorhabdus strains were isolated from nematodes obtained from the foot of Yuelu Mountain (City of Changsha, Hunan Province, China) by an entrapment method using Galleria melonella (Bedding and Akhurst, 1975). Adult instars of G. melonella were placed in 500 cm3 soil and incubated until death. The dead G. melonella was removed and washed with sterile water. Haemolymph samples were collected, plated onto NBTA medium (4.5 g nutrient agar, 0.004 g triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC), and 0.0025 g bromothymol blue per 100 ml distilled water), and incubated at 30 oC for 48 h. To obtain pure cultures, blue colonies were streaked on LB plates (1 g peptone, 0.5 g yeast extract, and 1 g NaCl per 100 ml distilled water) and incubated at 30 oC for 36 h.

Phylogenetic analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted using a genomic DNA isolation kit (TIANGEN BIOTECH). PCR products were gel-purified using a PCR purification kit (TIANGEN BIOTECH) and sequenced using Invitrogen (Shanghai). The 16S rRNA gene sequence of strain HN_xs01 was aligned using SINA sequence alignment software. The aligned sequences were imported into the database of the Living Tree Project release 121 database using the ARB software package (Yarza et al., 2008). The phylogenetic tree was reconstructed using the neighbor-joining method with Jukes–Cantor correction. For evolutionary phylogenetic analysis, bootstrap analysis was used to evaluate tree topology by performing 1,000 replications.

Isolation, purification and chemical characterization of cytotoxic compounds

For the detection and purification of cytotoxic compounds from HN_xs01, 5 L fermentation broth was mixed with the adsorbent resin XAD-16 at 30°C, 150 rpm for 4 days. The cells and resin were harvested by centrifugation and extracted using ethyl acetate. The extract was evaporated, redissolved in methanol, and then subjected to C18 column chromatography (Luna RP-C18 column, 100 × 2 mm, 2.5 μm particle size, and pre-column C18, 8 × 3 mm, 5 μm). Collected fractions were tested in a bioassay with CHO-K1 cells, and bioactive fractions were further purified to obtain three compounds via semi-preparative C18 chromatography. The planar structure of these compounds was elucidated using various spectroscopic/spectrometric techniques (see supplementary information), including high-resolution ESI-MS and MS/MS as well as 1D and 2D nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) experiments (1H, HSQC, HMBC, COSY). Cytotoxic activities of the three compounds against the A431 (human epithelial carcinoma) and K562 (human chronic myelogenous leukemia) cell lines were evaluated.

Animal tumor models

Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Hunan Normal University. Specific-pathogen-free male C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the SLRC Laboratory Animal Company, Hunan Province, China. The C57BL/6 mice, 6–8 weeks old, were injected with 5 × 105 B16 melanoma cells in the right front and left back hypodermic injections. After 7–10 days, when tumor volumes had reached ∼5 mm3, the animals were randomly assigned to different groups and observed continuously after injection. After a defined time, the mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation.

Tolerance analysis of HN_xs01 in healthy mice after intravenous injection

C57BL/6 mice (two mice per group) were injected intravenously with six concentrations of strain HN_xs01 (1 × 106 CFU/100 μL, 5 × 106 CFU/100 μL, 1 × 107 CFU/100 μL, 5 × 107 CFU/100 μL, 1 × 108 CFU/100 μL, or 5 × 108 CFU/100 μL) or with 100 μL sterile PBS (pH 7.4) for the control group. Survival was observed continuously for 10 days after injection.

Bacterial distribution and antitumor activity of HN_xs01

C57BL/6 mice bearing B16 tumors were injected intratumorally with HN_xs01 (1 × 108 CFU/100 μL) and 100 μL sterile PBS (control), respectively. After intratumoral injection, tumor volumes and mouse weight were measured for 10 days (seven mice per group). C57BL/6 mice bearing B16 tumors were injected intravenously with HN_xs01 (5 × 107 CFU/100 μL), E. coli Nissle 1917 (2 × 106 CFU/100 μL) (Stritzker et al., 2007), and 100 μL sterile PBS (control), respectively. The intravenous injection was performed twice, with the secondary injection administered 6 days after the first injection (four mice per group). The mice were sacrificed after 10 days. Tumors, livers, spleens, and kidneys were excised, weighed, and homogenized. Then serial dilutions were plated on NBTA or LB plates, and afterwards, colonies were counted, and CFU/g tissue was calculated.

Pulmonary metastasis

Mice bearing B16 tumors received intravenous injections of HN_xs01 (5 × 107 CFU/100 μl) and sterile PBS (control), respectively. After the injection, the mice were weighed daily and sacrificed by cervical dislocation after 7 days. Tumors, hearts, livers, spleens, lungs, and kidneys were isolated, and the tumor nodes were counted. Afterwards, the tissues were minced, serial dilutions were plated on LB agar, and the CFU/g was calculated after 24–48 h.

Histological analysis

For histological studies, the mice were sacrificed 6 days after intratumoral injection post. Tumors were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature overnight and then stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to examine tissue morphology and necrosis. The sections were observed and imaged under a microscope.

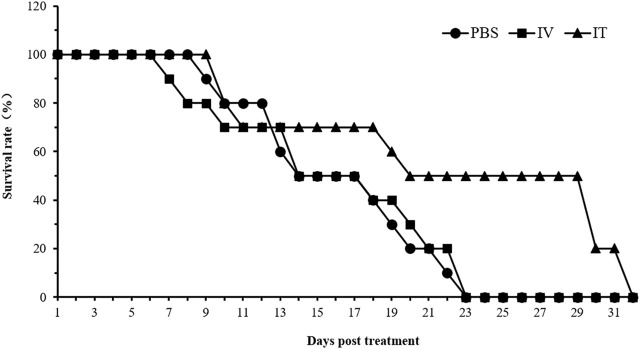

Mouse survival rate

C57BL/6 mice bearing B16 tumors (10 mice per group) were administered strain HN_xs01intravenously (5 × 107 CFU/100 μl) and intratumorally (1 × 108 CFU/100 μl) and then observed for 32 days. The control group received an equivalent volume of PBS.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance for all experiments was evaluated using the Student’s t-test in the software of GraphPad Prism 5.0 (Xu et al., 2020). If the p value was below 0.05, the difference was considered significant.

Results

HN_xs01 identified as X. stockiae via phylogenetic analysis and its growth characteristics

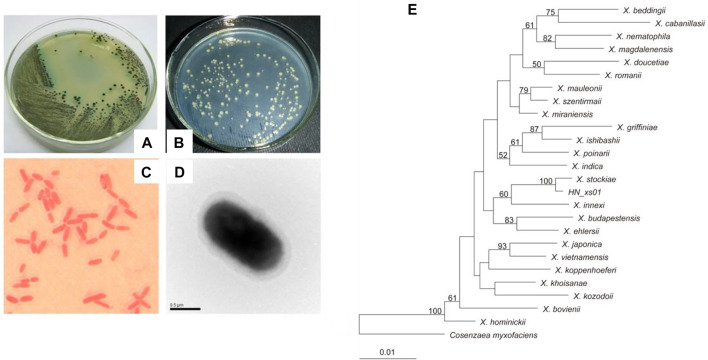

The bacterium HN_xs01 exhibited blue and red colonies on NBTA plates. The blue colonies are the primary form of strain HN_xs01, which can reduce TTC and absorb bromothymol blue. The red colonies are the secondary form of strain HN_xs01, which reduces TTC but does not absorb bromothymol blue and appears as red colonies (Figures 1A,B). HN_xs01 is a rod-shaped Gram-negative bacterium (approximately 1 µm in width; 1–3 µm in length) that does not form spores and is encapsulated by a thick layer, observed using a transmission electron microscopy (Figures 1C,D). The 16S rRNA gene sequence of strain HN_xs01 was submitted to the GenBank database, and accession number HQ840745 was assigned. Phylogenetic analysis based on 16S rRNA gene sequences revealed that strain HN_xs01 was 99% similar to X. stockiae (Figure 1E), suggesting that they belong to the same species.

FIGURE 1.

Morphology and phylogenetic analysis of strain HN_xs01. (A) Colony morphology of HN_xs01 on NBTA plate. (B) Colony morphology of HN_xs01 on LB plate. (C) Sarranine staining of HN_xs01. (D) The transmission electron microscopy of HN_xs01. (E) Phylogenetic dendrogram of HN_xs01. Bootstrap values are based on 1,000 replicates. The dendrogram was obtained by distance matrix analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequences.

Analysis of growth kinetics of the primary and secondary forms of strain HN_xs01 indicated that the growth of the primary form was slower than that of the secondary form after 12 h. Growth of the secondary form began to slow down after 12 h, whereas the primary form continued to grow, resulting in a significantly greater OD600 in LB broth and delayed entry into the stationary phase compared with the secondary form (Supplementary Figure S1A). Thus, the primary form has a growth advantage over the secondary form in LB cultures. The pH of the two forms rose sharply between 12 and 21 h and then stabilized (Supplementary Figure S1B). No significant differences were observed in the pH values of the primary and secondary forms during the culture process. The optimal temperature and pH ranges for growth were similar for the two forms. HN_xs01 grew over a wide temperature range, from 18 to 42°C, with an optimal growth temperature of 32°C (Supplementary Figure S1C). Additionally, HN_xs01 grew over a broad pH range from 4.6 to 8.5. The optimal pH for growth of the two forms was 6.6 and 8.2, respectively (Supplementary Figure S1D).

The supernatants of the primary and secondary forms of the strain HN_xs01 exhibited potent biological activities

Strain HN_xs01 exhibited broad-spectrum antimicrobial activities, including potent antibacterial activities against S. typhimurium and E. coli (Supplementary Figure S2A). The major antimicrobial compounds were produced after 12 h and reached optimal activity at 24 h. In addition, the primary form showed better antimicrobial activities than the secondary form, as evidenced by the greater zones of inhibition of the primary form. Insecticidal activity was evaluated via the injection of H. armigera larvae, and no significant differences were observed between the primary and the secondary forms. Supernatants of 72 h cultures had the highest insecticidal toxicity, and by 6 h after injection, the mortality of H. armigera reached 50%, whereas there were no deaths in the control group (Supplementary Figure S2B). In addition, the 72-h culture supernatant of HN_xs01, either in the primary or secondary form, inhibited the growth of H. armigera larvae via using an oral route of infection (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Inhibition of H. armigera larval growth after 72 h-culture of different forms of strain HN_xs01.

| Sample number | AVG ±SD (cm) | SX* | CVIB** (cm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 24 | 0.560 ± 0.054 | 0.011 | 0.395–0.650 |

| Phase I | 24 | 0.349 ± 0.061 | 0.013 | 0.220–0.440 |

| Phase II | 24 | 0.380 ± 0.062 | 0.013 | 0.275–0.485 |

*Std. Error mean.

*Cyclic variation of integrated backscatter.

CK, control. Phases I and II, indicate the primary and secondary forms of strain HN_xs01, respectively.

B16 melanoma cells were observed using phase contrast microscopy to visualize morphological changes in response to cultivation with HN_xs01. The results demonstrated that the cells of the control group (exposed to sterile LB) consisted of elongated, attached cells (Supplementary Figure S3B). In contrast, cells treated with the 72 h culture supernatants of the primary and secondary forms of HN_xs01 exhibited morphological alterations, including shrinkage and surface detachment, suggesting that the supernatants of strain HN_xs01 might induce cell apoptosis (Supplementary Figures S3C,S3D).

Structure elucidation of cytotoxic rhabdopeptides

Three compounds (1–3) were purified from the crude extract of the strain HN_xs01. The molecular formula of 1 was determined to be C31H54N5O4 based on the protonated HRMS peak at m/z 560.41601 [M + H]+ (calculated for 560.4170) (Supplementary Figure S6). The chemical shifts of the NMR spectra indicated the presence of one phenethylamine, three N-methyl-valines, and one valine (Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Figures S5,S7–S10). The molecular formula of 2 was determined to be C37H65N6O5 based on the protonated HRMS peak at m/z 673.50119 [M + H]+ (calculated for 673.5011) (Supplementary Figure S6). The chemical shifts in the NMR spectra indicated the presence of one phenethylamine, four N-methyl-valines, and one valine (Supplementary Table S2, Supplementary Figures S5, S11–S14). In addition, the molecular formula of 3 was determined to be C43H75N7O6 based on the protonated HRMS peak at m/z 786.5868 [M + H]+ (calculated for 786.5852) (Supplementary Figure S6). The chemical shifts of the NMR spectra indicated the presence of one phenethylamine, five N-methyl-valines, and one valine (Supplementary Table S3, Supplementary Figure S5, S15–S18). The structures of 1, 2, 3 showed that they belonged to the rhabdopeptides, and the difference was the number of residues of the amino acid N-methyl-valine. The cytotoxic assays demonstrated that 3 had strong cytotoxic activity against A431 cells and K562 cells compared with 1 and 2, with IC50 values of 2.5 μg/ml and 1.5 μg/ml, respectively (Table 2). Based on the anticancer activity results, we deduced that N-methyl-valine might enhance the cytotoxic bioactivity of compounds.

TABLE 2.

In vitro cytotoxicity (IC50) of isolated compounds against A431 and K562 cells.

| IC50 [µg/mL] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Formula | A431 | K562 |

| 1 | C31H53N5O4 | >50 | 22.0 |

| 2 | C43H75N7O6 | ca. 40** | 18.0 |

| 3 | C37H64N6O5 | 2.5 | 1.5 |

| Zileuton | C11H12N2O2S | 7.7 | 7.1 |

“**” indicates branch cells.

A431 cells, human epithelial carcinoma cells; K562 cells, human chronic myelogenous leukemia cells.

HN_xs01 targeted and retrained the growth of B16 tumors in vivo

Based on its wide growth characteristics and the potent antitumor activity of HN_xs01, we furtherly quested whether this strain could be as a novel antitumor-targeting strain in vivo or not. Two strategies of intravenous and intratumoral administrations of HN_xs01 to the C57BL/C mice bearing B16 tumor were performed. At the beginning, the maximum concentration of HN_xs01 administrated by intravenous injection to the healthy C57BL/C mice was investigated. The results demonstrated that high numbers of HN_xs01 (5 × 108 CFU/100 μL) caused immediate death. Injection of 1 × 108 CFU/100 μL resulted in 50% mortality in the mice. At a concentration of 5 × 107 CFU/100 μL, all mice were still alive for 10 days (Supplementary Figure S4); thus, the results showed that four concentrations (1 × 106 CFU/100 μL, 5 × 106 CFU/100 μL, 1 × 107 CFU/100 μL, and 5 × 107 CFU/100 μL) were safe, and we used an intravenous injection of 5 × 107 CFU/100 μL to investigate the inhibition of HN_xs01 in the C57BL/C B16 tumor-bearing model.

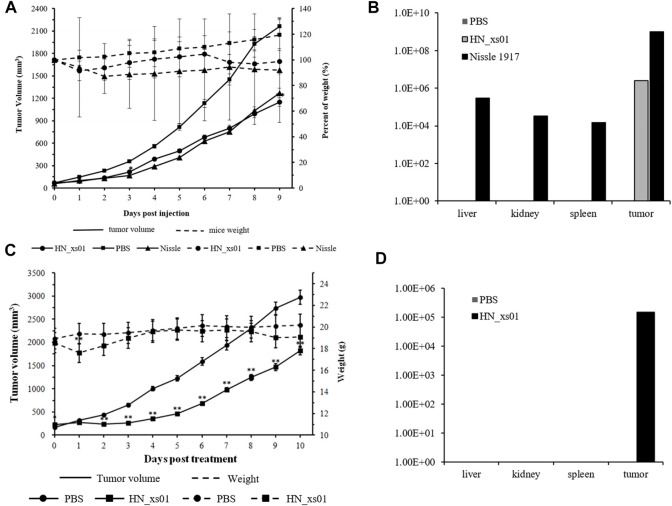

To illustrate the tumor-specific colonization and repression of HN_xs01, we compared HN_xs01 with the probiotic E. coli Nissle 1917, which had efficient tumor colonization (Stritzker et al., 2007). The number of the intravenous injections of the strain HN_xs01 and the amount of E. coli Nissle 1917 was 5 × 107 CFU/100 μL and 2 × 106 CFU/100 μL, respectively, according to the above result and previous study. The results showed that both strains notably delayed tumor growth compared with the control group, suggesting no obvious disparity in antitumor activity between HN_xs01 and Nissle 1917 (Figure 2A). However, antitumor activity was more sustainable in the preliminary stage after the administration of HN_xs01. Eight days after the administration of bacteria, the HN_xs01 group exhibited preferential inhibition of tumor growth compared with the Nissle 1917 group. Additionally, we observed obvious differences in body weight after the injection of PBS, HN_xs01, or Nissle 1917. The control group demonstrated slow growth, whereas the body weight of mice treated with Nissle 1917 decreased continuously. Interestingly, the body weight of mice decreased slightly after the first injection of HN_xs01, and 3 days later, the weight began to recover. We performed a second injection 6 days after the first, and a similar phenomenon was observed (Figure 2A). Thus, strain HN_xs01 had no obvious effect on the mice growth, suggesting that it is less toxic than Nissle 1917. Smaller amounts of E. coli Nissle 1917 were detected in the liver (3 × 105 CFU/g), kidney (3.4 × 104 CFU/g), and spleen (1.5 × 104 CFU/g) than in the tumor (1 × 109 CFU/g). However, strain HN_xs01 was concentrated in the tumor area and undetectable in other organs (Figure 2B). Surprisingly, the number of Nissle 1917 bacteria in the tumor area was higher than that of HN_xs01, we deduced that HN_xs01 might be easily eliminated by the immune system of mice compared to Nissle 1917. To sum up, HN_xs01 had stronger tumor-specific colonization than Nissle 1917 in the aspect of the intravenous administration, indicating that HN_xs01 was a promising strain for intravenous tumor treatment.

FIGURE 2.

The effect and distribution of HN_xs01 on tumor growth and organ colonization following intravenous and intratumoral injections. (A) Mice bearing B16 tumors were injected intravenously with PBS, 2 × 106 CFU/100 μl of E. coli Nissle 1917, or 5 × 107 CFU/100 μl of HN_xs01, respectively. Tumor volume (mm3) and percent of mice weight (%) were measured mice. The antitumor activity of HN_xs01 was similar to that of E. coli Nissle 1917 by intravenous administration. Tumors were significantly inhibited by intravenous injection of HN_xs01. (B) Bacterial distribution in organs was calculated by CFU/g by intravenous administration. Strain HN_xs01 was undetectable in the liver, kidney, and spleen, but small amounts of E. coli Nissle 1917 were detected in other organs compared to the tumor area. (C) Mice bearing B16 tumors were treated by intratumoral injection of PBS or 1 × 108 CFU/100 μl of HN_xs01. Tumors were significantly inhibited by intratumoral injection of HN_xs01. (D) Bacterial distribution in organs was calculated by CFU/g via intratumoral administration. Strain HN_xs01 strictly colonized the tumor region. Data are shown for n = 4 mice per group by intravenous injection and n = 7 mice per group for intratumoral injection.

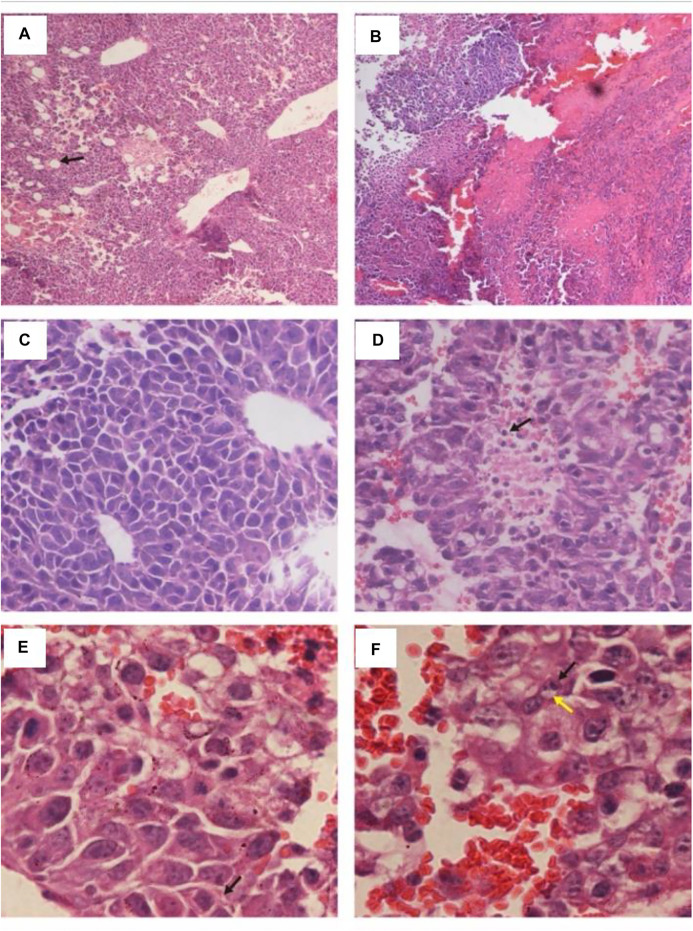

In the C57BL/C B16 tumor-bearing model, treatment with HN_xs01 significantly delayed tumor growth through intratumoral administration as well. Ten days after administration, the tumor volume in the control group was 1.63 fold greater than that in the treatment group. Nevertheless, the weight of mice treated with HN_xs01 initially decreased and recovered after 3 days, which suggested that strain HN_xs01 had a transient negative effect on the mice (Figure 2C). At sacrifice, no bacteria were present in the liver, kidney, or spleen, and strain HN_xs01 strictly colonized the tumor area (Figure 2D). These data revealed that HN_xs01 exhibited significant antitumor activity and tumor targeting following intratumoral injection. In addition, the B16 tumor of the treatment group appeared the conspicuous necrotic areas, fewer blood vessels, sparse cells, chromatin-forming physalides, and undivided nuclei via H&E staining comparing with no abnormalities and maintained their division of the tumor cells in the control group (Figures 3A–F). The differences of the tumor morphology between the PBS and HN_xs01 treatment groups indicate that HN_xs01 inhibits tumor growth by inhibiting blood vessel proliferation and inducing cell apoptosis. Thus, HN_xs01 inhibits tumor growth through multiple mechanisms.

FIGURE 3.

Histology of B16 tumors injected with HN_xs01 or PBS. C57BL/C mice bearing B16 tumors were injected intratumorally with 1 × 108 CFU/100 μl of HN_xs01, and the tumors were examined by H&E staining at 6 days post-treatment. The left panels show results of PBS treatment, and the right panels show results of HN_xs01 treatment. The areas of B16 melanoma is shown under 100 × low magnification in (A,B). Enlargement of areas of B16 melanoma is shown in panels (C–F). The arrows in (A,D) indicate areas of blood vessels and dividing cells. The black and yellow arrows in (E,F) indicate shrunken chromatin and physalides, respectively.

HN_xs01 significantly restrained the pulmonary metastasis of B16 tumors

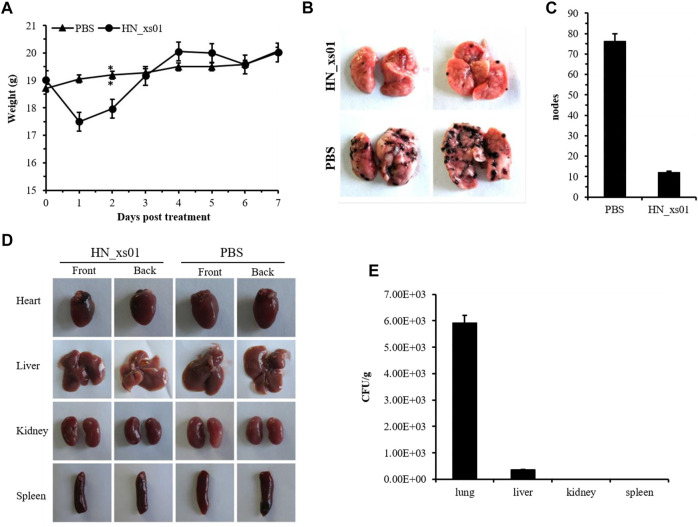

Body weight was slightly affected by the intravenous injection of HN_xs01, but the weight returned to normal 3 days post-injection (Figure 4A). After 7 days, the organisms of the control and treatment groups were taken out. We found that the tumor nodes were detected in the lungs of the PBS and HN_xs01 treatment groups, and the number of nodes on the lung surfaces of mice from the PBS group was 6.35-fold greater than that in the HN_xs01 group, but not undetected in the heart, liver, kidney and spleen tissues, confirming that the B16 tumor model spontaneously metastasizes from tumors to the lungs (Figures 4B–D). At the treatment group, the number of the bacteria HN_xs01 in the lung (6 × 103 CFU/g) of mice was significantly greater than that in the liver (353 CFU/g), whereas no bacteria were detected in the kidney or spleen tissues (Figure 4E). These data demonstrated that HN_xs01 could efficiently inhibit pulmonary metastasis of mouse melanoma.

FIGURE 4.

The effect of HN_xs01 on pulmonary metastasis of B16 tumors. (A) Mice with B16 tumors were injected intravenously with PBS or 5 × 107 CFU/100 μl of HN_xs01, and body weight was measured daily. (B) The nodes distribution in the lungs of the PBS and HN_xs01 groups. After 1 week, the lungs, hearts, livers, kidneys, spleens, and tumors were isolated. (C) The nodes number in the lungs of the PBS and HN_xs01 groups. (D) The tumor nodes distribution in the heart, liver, kidney, and spleen tissues between the PBS and HN_xs01 groups. (E) Bacterial distribution in organs was calculated by CFU/g. Strain HN_xs01 mostly colonized the lung region.

Intratumoral administration of HN_xs01 efficiently prolonged mouse survival time

C57BL/C mice bearing B16 tumors were administered with 5 × 107 CFU/100 μL of strain HN_xs01 intravenously, 1 × 108 CFU/100 μL of strain HN_xs01 by intratumorally, and PBS (control). The intratumoral injection significantly extended the mouse survival time; the mortality rate reached 50% 20 days after injection and 100% by day 32 post-injection (Figure 5). In contrast, the mortality rates of the PBS group and intravenous injection groups reached 100% after 23 days. Thus, the intratumoral injection of HN_xs01 was significantly more effective than the intravenous injection in prolonging mouse survival time.

FIGURE 5.

The effect of HN_xs01 on mouse survival. C57BL/6 mice were administered with strain HN_xs01 intravenously (5 × 107 CFU/100 μl) and intratumorally (1 × 108 CFU/100 μl) for 32 days, respectively. The control group received an equivalent volume of PBS. There were 10 mice per group, and the mice were monitored for 32 days. IV: intravenous injection, IT: intratumoral injection.

Discussion

In our study, the bacterial strain HN_xs01 was identified as X. stockiae and found to have multiple high-efficiency biological activities. Xenorhabdus strains can spontaneously produce two physiological forms (primary and secondary) in vitro. The primary form can produce several antibiotics and various proteins; however, these properties are greatly reduced or absent in the secondary form (Gualtieri et al., 2009). Nonetheless, a secondary form, such as the hypopus, is produced during in vitro monoxenic culture of nematodes, where the bacterium is detrimental to the final yield of nematodes (Akhurst, 1980). There were significant differences in the growth curves and the optimal pH for growth between the primary and secondary forms. HN_xs01 grew over a wide temperature range, indicating that this strain was heat-resistant. It also grew well at pH 6.5 and pH 8.0 owing to its original living environment (i.e., the intestinal vesicles in nematodes and hemocoel of insects) (Bird and Akhurst, 1983).

Xenorhabdus strains are rich resources of active natural compounds. However, research on symbiotic bacteria of entomopathogenic nematodes is relatively new. Here, we tested the antimicrobial, insecticidal, and antitumor activities of the strain HN_xs01, which has broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties. S. aureus and S. typhimurium were highly sensitive to HN_xs01 in antimicrobial bioassays. In previous studies, comparative analysis of the antimicrobial activity of Xenorhabdus species on other bacteria suggested that antibiotics produced by Xenorhabdus were effective against animal and plant pathogens (Furgani et al., 2008; Fodor et al., 2010). Furthermore, Xenorhabdus strains have potential antifungal activity relevant to agriculture (Fang et al., 2011; Tobias et al., 2018). Strain HN_xs01 exhibited potent activity against H. armigera larvae when injected. However, its oral insecticidal activity was poor and only inhibited insect growth. Therefore, our findings suggest that the toxins of HN_xs01 are presumably essential for bacteria to rapidly kill infected insects, and act preferentially when injected, similarly to Xenorhabdus (Sergeant et al., 2006). Additionally, Xenorhabdus possesses significant pathogenic activity against some important insect pests of commercial crops, such as lepidopteran, dipteran, and coleopteran, and is considered a neotype biological insecticide after B. thuringiensis (Burnell and Stock, 2000; Chattopadhyay et al., 2004; Georgis et al., 2006). A high-efficiency “Bt-Plus” insecticide has been reported to enhance the insecticidal activity of B. thuringiensis by mixing it with broth cultures of the X. nematophila primary form, which suppresses target insect immunity (Eom et al., 2014).

In vitro cytotoxicity assays using extracts of strain HN_xs01 exhibited antitumor activities, and purified compounds 1, 2, and 3, belonging to the rhabdopeptide/xenortide peptide class (RXPs) were the same with the rhabdopeptides elucidated from an extract mixture based on labeling and MS experiments previously (Reimer et al., 2013; Cai et al., 2017; Shi and Bode, 2018). However, the structures of compounds 1, 2, 3 were first elucidated by NMR. In addition, three of the seven rhabdopeptides discovered by the Yu group were known rhabdopeptides, and the other four novel rhabdopeptides included two valines (Bi et al., 2018). Moreover, the potent antitumor activities of 3 against human epithelial carcinoma cell line A431 and human chronic myelogenous leukemia cell line K562 reveal the rhabdopeptides could be promising drugs for the tumor chemotherapy. Notably, the efficient tumor-specific colonization and replication of HN_xs01 in the tumor regions compared with the probiotics E. coli Nissle 1917, combined with HN_xs01 producing the antitumor compounds contribute strain HN_xs01 to restrain B16 solid tumors. Bacteria can induce cell apoptosis through multiple mechanisms, including the stimulation of immune cells, competition for extracellular nutrients, and induction of apoptotic signal transduction pathways following intracellular accumulation (Ganai et al., 2011). Our analyses indicated that active secondary metabolites produced by strain HN_xs01 also contribute to tumor cell apoptosis. Moreover, HN_xs01 significantly restrained the pulmonary metastasis of B16 tumors. These characteristics predict that HN_xs01 could be a novel bacterial tumor-targeting strain.

The application of bacteria in cancer therapy has been presented as a novel approach, although the potential of this approach has been described before the development of conventional therapies (Baban et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2014). Tumor regression has been observed in cancer patients suffering from infections with Clostridium or Streptococcus pyogenes (Felgner et al., 2016). Subsequently, many strains of various genera have been tested for their potential in cancer therapy using various animal models. Spores of Clostridium only germinate in the absence of oxygen and cannot reach anaerobic regions; therefore, metastases or small tumors without necrotic areas might not be targeted by this approach. Facultative anaerobic bacteria, such as S. typhimurium, can grow under aerobic conditions but potentially disseminates to healthy tissues (Choe et al., 2014; Hoffman and Zhao, 2014). Although bacteria can be modified for use in clinical studies, their use presents many disadvantages that cannot be avoided in cancer therapy. To solve this problem, suitable strains are acquired by passaging in vitro or in vivo or by deleting targeted genes using molecular techniques. Our analysis showed that the intratumoral administration of HN_xs01 was more beneficial to prolong the mouse survival than intravenous administration. We deduced that HN_xs01 might spread to healthy tissue liver of mice via intravenous injection resulting in liver damage. Thus, HN_xs01 need be engineered furtherly to make it be suitable for clinical cancer therapy. Gene-based anti-angiogenic therapy has been used in conjunction with other approaches to decrease angiogenesis, such as bifidobacterial expression of endostatin genes (Baban et al., 2010; Cummins and Tangney, 2013). Engineering the strain HN_xs01 to successfully express cytotoxic agents such as glidobactin and luminmide (data not shown), is an efficient strategy for enhancing its antitumor properties, which suggests that HN_xs01 could be a potential chassis for the other active antitumor resources.

In conclusion, the primary and secondary forms of the identified bacterium X. stockiae HN_xs01 exhibit potent and diverse biological activities. The efficient tumor-specific colonization and inhibition of X. stockiae HN_xs01 to B16 solid tumors and pulmonary metastasis in vivo manifest it be a novel bacterial tumor-targeting strain for cancer therapy in the future.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Xiangmei Ren from the State Key Laboratory of Microbial Technology of Shandong University for help and guidance in samples testing, and Jennifer Herrmann (HIPS) for expert assistance with various analytical techniques.

Data availability statement

The 16S rRNA gene sequence of strain HN_xs01 was submitted to the GenBank database, accession number HQ840745.

Ethics statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by College of life sciences, Hunan Normal University.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, CZ and YZ; methodology, CZ, HC. HS and QT; software, CZ and HbS; validation, CZ, HS, WZ, and QT; formal analysis, CZ and HC; investigation, CZ, HC, HbS, XD, JY and YY; resources, RM, LX, YZ and QT; data curation, CZ and HC; “writing original draft preparation, CZ and HC; writing” review and editing, RM, LX, YZ and QT; supervision, RM, LX, YZ and QT; funding acquisition, RM, LX, YZ and QT. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by funding from the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2019YFA0904000); the Recruitment Program of Global Experts (1,000 Plan); Shandong Key Research and Development Program (2019JZZY010724); Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2021QC170) and the Program of Introducing Talents of Discipline to Universities (B16030).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbioe.2022.984197/full#supplementary-material

References

- Agrawal N., Bettegowda C., Cheong L., Geschwind J. F., Drake C. G., Hipkiss E. L., et al. (2004). Bacteriolytic therapy can generate a potent immune response against experimental tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101, 15172–15177. 10.1073/pnas.0406242101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhurst R. J. (1980). Morphological and functional dimorphism in Xenorhabdus spp., bacteria symbiotically associated with the insect pathogenic nematodes Neoaplectana and Heterorhabditis . Microbiology 121, 303–309. 10.1099/00221287-121-2-303 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baban C. K., Cronin M., O'Hanlon D., O'Sullivan G. C., Tangney M. (2010). Bacteria as vectors for gene therapy of cancer. Bioeng. Bugs 1, 385–394. 10.4161/bbug.1.6.13146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedding R. A., Akhurst R. J. (1975). A simple technique for the detection o f insect paristic rhabditid nematodes in soil. Nematol. 21, 109–110. 10.1163/187529275X00419 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bi Y. H., Gao C. Z., Yu Z. G. (2018). Rhabdopeptides from Xenorhabdus budapestensis SN84 and their nematicidal activities against Meloidogyne incognita . J. Agric. Food Chem. 66, 3833–3839. 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b00253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird A. F., Akhurst R. J. (1983). The nature of the intestinal vesicle in nematodes of the family steinernematidae. Int. J. Parasitol. 13, 599–606. 10.1016/S0020-7519(83)80032-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. E., Cao A. T., Dobson P., Hines E. R., Akhurst R. J., East P. D. (2006). Txp40, a ubiquitous insecticidal toxin protein from Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 1653–1662. 10.1128/AEM.72.2.1653-1662.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnell A. M., Stock S. P. (2000). Heterorhabditis, Steinernema and their bacterial symbionts- lethal pathogens of insects. Nematology 2, 31–42. 10.1163/156854100508872 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X. F., Nowak S., Wesche F., Bischoff I., Kaiser M., Fürst R., et al. (2017). Entomopathogenic bacteria use multiple mechanisms for bioactive peptide library design. Nat. Chem. 9, 379–386. 10.1038/nchem.2671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaston J. M., Suen G., Tucker S. L., Andersen A. W., Bhasin A., Bode E., et al. (2011). The entomopathogenic bacterial endosymbionts Xenorhabdus and photorhabdus: Convergent lifestyles from divergent genomes. PLos One 6, e27909. 10.1371/journal.pone.0027909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay A., Bhatnagar N. B., Bhatnagar R. (2004). Bacterial insecticidal toxins. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 30, 33–54. 10.1080/10408410490270712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe E., Kazmierczak R. A., Eisenstark A. (2014). Phenotypic evolution of therapeutic Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium after invasion of TRAMP mouse prostate tumor. MBio 5, e01182–e01114. 10.1128/mBio.01182-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimen H., Touray M., Gulsen S. H., Hazir S. (2022). Natural products from photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus: Mechanisms and impacts. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 106, 4387–4399. 10.1007/s00253-022-12023-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins J., Tangney M. (2013). Bacteria and tumours: Causative agents or opportunistic inhabitants? Infect. Agent. Cancer 8, 11–18. 10.1186/1750-9378-8-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eom S., Park Y., Kim H., Kim Y. (2014). Development of a high efficient "Dual Bt-Plus" insecticide using a primary form of an entomopathogenic bacterium, Xenorhabdus nematophila. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 24, 507–521. 10.4014/jmb.1310.10116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang X. L., Li Z. Z., Wang Y. H., Zhang X. (2011). In vitro and in vivo antimicrobial activity of Xenorhabdus bovienii YL002 against Phytophthora capsici and Botrytis cinerea . J. Appl. Microbiol. 111, 145–154. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.05033.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang X. L., Zhan g. M. R., Tang Q., Wang Y. H., Zhang X. (2014). Inhibitory effect of Xenorhabdus nematophila TB on plant pathogens Phytophthora capsici and Botrytis cinerea in vitro and in planta. Sci. Rep. 4, 4300–1158. 10.1038/srep04300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felgner S., Kocijiancic D., Frahm M., Weiss S. (2016). Bacteria in cancer therapy: Renaissance of an old concept. Int. J. Microbiol., 2016, 1–14. 10.1155/2016/8451728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodor A., Fodor A. M., Forst S., Hogan J. S., Klein M. G., Katalin L., et al. (2010). Comparative analysis of antibacterial activities of Xenorhabdus species on related and non-related bacteria in vivo . J. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2, 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- Furgani G., Boszormenyi E., Fodor A., Mathe-Fodor A., Forst S., Hogan J. S., et al. (2008). Xenorhabdus antibiotics: A comparative analysis and potential utility for controlling mastitis caused by bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 104, 745–758. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03613.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganai S., Arenas R. B., Sauer J. P., Bentley B., Forbes N. S. (2011). In tumors Salmonella migrate away from vasculature toward the transition zone and induce apoptosis. Cancer Gene Ther. 8, 457–466. 10.1038/cgt.2011.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgis R., Koppenhofer A. M., Lacey L. A., Belair G., Duncan L. W., Grewal P. S., et al. (2006). Successes and failures in the use of parasitic nematodes for pest control. Biol. Control 38, 103–123. 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2005.11.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gualtieri M., Aumelas A., Thaler J. O. (2009). Identification of a new antimicrobial lysine-rich cyclolipopeptide family from Xenorhabdus nematophila . J. Antibiot. 62, 295–302. 10.1038/ja.2009.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman R. M., Zhao M. (2014). Methods for the development of tumor-targeting bacteria. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 9, 741–750. 10.1517/17460441.2014.916270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jean A. T. St., Zhang M. M., Forbes N. S. (2008). Bacterial therapies: Completing the cancer treatment toolbox. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 19, 511–517. 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Xu X. P., Zeng X., Li L. J., Chen Q. M., Li J. (2014). Tumor-targeting bacterial therapy: A potential treatment for oral cancer (review). Oncol. Lett. 8, 2359–2366. 10.3892/ol.2014.2525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcinerney B. V., Taylor W. C., Lacey M. J., Akhurst R. J., Gregson R. P. (1991). Biologically active metabolites from Xenorhabdus Spp. Part 2. Benzopyran-1-one derivatives with gastroprotective activity. J. Nat. Prod. (Gorakhpur). 54, 785–795. 10.1021/np50075a006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Z. W., Huang S., Yu Y., Deng H. (2013). Dithiolopyrrolone natural products: Isolation, synthesis and biosynthesis. Mar. Drugs 11, 3970–3997. 10.3390/md11103970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimer D., Cowles K. N., Proschak A., Nollmann F. I., Dowling A. J., Kaiser M., et al. (2013). Rhabdopeptides as insect-specific virulence factors from entomopathogenic bacteria. Chembiochem 14, 1991–1997. 10.1002/cbic.201300205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts N. J., Zhang L. P., Filip J. K., Collins A., Bai R. Y., Staedtke V., et al. (2014). Intratumoral injection of Clostridium novyi-NT spores induces antitumor responses. Sci. Transl. Med. 6, 249ra111. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samaliev H. Y., Andreoglou F. I., Elawad S. A., Hague N., Gowen S. (2000). The nematicidal effects of the bacteria Pseudomonas oryzihabitans and Xenorhabdus nematophilus on the root-knot nematode meloidogyne javanica. Nematology 2, 507–514. 10.1163/156854100509420 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sergeant M., Baxter L., Jarrett P., Shaw E., Ousley M., Winstanley C., et al. (2006). Identification, typing, and insecticidal activity of Xenorhabdus isolates from entomopathogenic nematodes in United Kingdom soil and characterization of the xpt toxin loci. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 5895–5907. 10.1128/AEM.00217-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y. M., Bode H. B. (2018). Chemical language and warfare of bacterial natural products in bacteria-nematode-insect interactions. Nat. Prod. Rep. 35 (4), 309–335. 10.1039/c7np00054e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicard M., Hinsinger J., Brun N. L., Pages S., Boemare N., Moulia C. (2006). Interspecific competition between entomopathogenic nematodes (Steinernema) is modified by their bacterial symbionts (Xenorhabdus). BMC Evol. Biol. 6, 68–77. 10.1186/1471-2148-6-68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S., Orr D., Divinagracia E., McGraw J., Dorff K., Forst S. (2015). Role of secondary metabolites in establishment of the mutualistic partnership between Xenorhabdus nematophila and the entomopathogenic nematode Steinernema carpocapsae . Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 754–764. 10.1128/AEM.02650-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staunton J., Weissman K. J. (2001). Polyketide biosynthesis: A millennium review. Nat. Prod. Rep. 18, 380–416. 10.1039/a909079g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strieker M., Tanović A., Marahiel M. A. (2010). Nonribosomal peptide synthetases: Structures and dynamics. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 20, 234–240. 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stritzker J., Weibel S., Hill P. J., Oelschlaeger T. A., Goebel W., Szalay A. A. (2007). Tumor-specific colonization, tissue distribution, and gene induction by probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 in live mice. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 297, 151–162. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2007.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tailliez P., Pages S., Ginibre N., Boemare N. (2006). New insight into diversity in the genus Xenorhabdus, including the description of ten novel species. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56, 2805–2818. 10.1099/ijs.0.64287-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W., He Y. F., Zhou S. C., Ma Y. P., Liu G. L. (2009). A novel Bifidobacterium infantis-mediated TK/GCV suicide gene therapy system exhibits antitumor activity in a rat model of bladder cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 28, 155–157. 10.1186/1756-9966-28-155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas G. M., George J. R. (1979). Xenorhabdus gen. nov., a genus of entomopathogenic, nematophilic bacteria of the family enterobacteriaceae. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 29, 352–360. 10.1099/00207713-29-4-352 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tobias N. J., Shi Y. M., Bode H. B. (2018). Refining the natural product repertoire in entomopathogenic bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 26, 833–840. 10.1016/j.tim.2018.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu N., Wang L., Fu S., Jiang B. (2020). Resveratrol is cytotoxic and acts synergistically with NF-κB inhibition in osteosarcoma MG-63 cells. Arch. Med. Sci. 17, 166–176. 10.5114/aoms.2020.100777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarza P., Richter M., Peplies J. J., Amann R., Schleifier K., Schleifer K. H., et al. (2008). The all-species living tree project: A 16S rRNA-based phylogenetic tree of all sequenced type strains. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 31, 241–250. 10.1016/j.syapm.2008.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B., Yang M., Shi L., Yao Y. D., Jiang Q. Q., Li X. F., et al. (2012). Explicit hypoxia targeting with tumor suppression by creating an "obligate" anaerobic Salmonella Typhimurium strain. Sci. Rep. 2, 436. 10.1038/srep00436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. L., Zhang Y. M., Xia L. Q., Zhang X. L., Ding X. Z., Yan F., et al. (2012). Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 targets and restrains mouse B16 melanoma and 4T1 breast tumors through expression of Azurin protein. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78 (21), 7603–7610. 10.1128/AEM.01390-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The 16S rRNA gene sequence of strain HN_xs01 was submitted to the GenBank database, accession number HQ840745.