Abstract

While freshwater cyanobacteria are traditionally thought to be limited by the availability of phosphorus (P), fixed nitrogen (N) supply can promote the growth and/or toxin production of some genera. This study characterizes how growth on N2 (control), nitrate (NO3–), ammonium (NH4+), and urea as well as P limitation altered the growth, toxin production, N2 fixation, and gene expression of an anatoxin-a (ATX-A) – producing strain of Dolichospermum sp. 54. The transcriptomes of fixed N and P-limited cultures differed significantly from those of fixed N-deplete, P-replete (control) cultures, while the transcriptomes of P-replete cultures amended with either NH4+ or NO3– were not significantly different relative to those of the control. Growth rates of Dolichospermum (sp. 54) were significantly higher when grown on fixed N relative to without fixed N; growth on NH4+ was also significantly greater than growth on NO3–. NH4+ and urea significantly lowered N2 fixation and nifD gene transcript abundance relative to the control while cultures amended with NO3– exhibited N2 fixation and nifD gene transcript abundance that was not different from the control. Cultures grown on NH4+ exhibited the lowest ATX-A content per cell and lower transcript abundance of genes associated ATX-A synthesis (ana), while the abundance of transcripts of several ana genes were highest under fixed N and P - limited conditions. The significant negative correlation between growth rate and cellular anatoxin quota as well as the significantly higher number of transcripts of ana genes in cultures deprived of fixed N and P relative to P-replete cultures amended with NH4+ suggests ATX-A was being actively synthesized under P limitation. Collectively, these findings indicate that management strategies that do not regulate fixed N loading will leave eutrophic water bodies vulnerable to more intense and toxic (due to increased biomass) blooms of Dolichospermum.

Keywords: nitrogen, ammonium, nitrate, urea, phosphorus, N2 fixation, Dolichospermum, anatoxin-a

Introduction

Dolichospermum, formerly known as Anabaena (Wacklin et al., 2009), is a cyanobacterial genus that includes toxin-producing taxa which can form harmful blooms (CHABs) in fresh (O’Neil et al., 2012; Li et al., 2016) and brackish water (Paul et al., 2016; Olofsson et al., 2020) ecosystems. Blooms of this genus are increasing in frequency, intensity, and geographic range due to climate change and eutrophication (O’Neil et al., 2012; Salmaso et al., 2015; Li et al., 2016). This genus belongs to the order Nostocales (Fogg, 1942; Issa et al., 2014), a group of dinitrogen (N2) - fixing cyanobacteria that develops heterocysts when fixed N is limiting (Mickelson et al., 1967; El-Shehawy and Kleiner, 2003) and utilizes the enzyme nitrogenase to convert N2 to ammonia (Wolk et al., 1994; Hoffman et al., 2014).

Primary productivity in freshwater ecosystems is traditionally considered phosphorus (P) - limited (Correll, 1999; Blomqvist et al., 2004) because N2-fixing cyanobacteria, or diazotrophs, which bloom under P-replete conditions (Gobler et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2021), produce newly fixed N to support phytoplankton growth (Smith, 1983, 2016; Schindler et al., 2008). The proportion of newly fixed N relative to total nitrogen in eutrophic lakes, however, can be extremely variable (6–80%), and is often regarded as insufficient to supply CHAB taxa with N sufficient to achieve optimal biomass (Howarth et al., 1988; Scott and McCarthy, 2010; Hellweger et al., 2016) due to micronutrient and light limitation (Wurtsbaugh and Horne, 1983; Lewis and Levine, 1984) as well as denitrification (Paerl, 2017). Dolichospermum populations do not necessarily bloom in response to P-enrichment (Paerl et al., 2014), and in some cases exhibit a higher demand for P than non-diazotrophic cyanobacteria (Wan et al., 2019). Collectively, these data suggest that P-enrichment alone is insufficient for Dolichospermum to achieve maximum growth rates, and that diazotrophy may not fully meet the fixed N demands required for Nostocales to bloom (Dolman et al., 2012; Shatwell and Köhler, 2018; Chaffin et al., 2019; Gamez et al., 2019). Furthermore, the fixed N species preferred by Dolichospermum to achieve optimal growth rates and how members of this genus respond to fixed N and P– depletion are poorly understood and warrant further investigation.

Nostocales also significantly reduce nitrogenase activity and upregulate metabolic pathways for fixed N assimilation when certain fixed N compounds are abundant, though the degree of reduced N2 fixation is dependent on the fixed N species provided and not always associated with enhanced growth (Sanz et al., 1995; Mekonnen et al., 2002; Zulkefli and Hwang, 2020). The effects of fixed N deprivation on Dolichospermum genome expression have been studied, with genes associated with heterocyst development and N2 fixation being significantly upregulated, for instance (Ehira et al., 2003; Flaherty et al., 2011; He et al., 2021). However, studies that have described how the Dolichospermum genome responds to different fixed N species (NH4+, NO3–) have never included urea, which can significantly suppress N2 fixation and enhance growth rates and toxin production (Ge et al., 1990; Qian et al., 2017). Since the 1980s, urea has also become the predominant fixed N fertilizer in the United States (Paerl et al., 2016), and its use in China is significantly positively correlated with the duration and number of CHABs (Glibert et al., 2014). The effects of P depletion on Dolichospermum genome expression availability (Teikari et al., 2015) have also never been coupled to changes in fixed N availability and would be essential for understanding how co-limitation affects this genus.

Dolichospermum spp. can produce a wide variety of toxins, including the neurotoxic congener anatoxin-a (ATX-A) (Devlin et al., 1977; Sanchez et al., 2014; Christensen and Kahn, 2020). ATX-A mimics the action of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (Carmichael et al., 1979; Spivak et al., 1980), causing muscle fatigue, paralysis, or even death (Carmichael, 1994; Humpage et al., 1994; Lilleheil et al., 1997), and is synthesized by enzymes encoded by genes belonging to the anatoxin synthetase gene (ana) cluster (Rantala-Ylinen et al., 2011). ATX-A - producing Dolichospermum strains originate from several continents, including North America, Europe, and Australia (John et al., 2019; Österholm et al., 2020). While ATX-A concentrations and the growth of some Nostocales strains can significantly increase in response to fixed N enrichment (Dolman et al., 2012; Qian et al., 2017) and a higher dissolved N:P ratio (Toporowska et al., 2016), other strains exhibit significantly reduced ATX-A quotas but significantly higher biomass in response to NO3– amendment (Gagnon and Pick, 2012). Thus, the effects of different fixed N forms and P-limitation on Dolichospermum ATX-A production are unclear and warrant further investigation.

Ultimately, while Dolichospermum growth and N2 fixation rates can be responsive to fixed N, the differential effects of different fixed N species as well as fixed N and P co-limitation on members of this genus have not been investigated. Thus, the objective of this study was to quantify the effects of NH4+, NO3–, and urea, as well as fixed N and P co-limitation, on the growth, N2 fixation, photosystem II photosynthetic efficiency (Fv/Fm), toxin production, and genome-wide expression of Dolichospermum sp. 54, an ATX-A-producing taxon. We hypothesized that the availability of any of the three fixed N forms would lead to significant reductions in N2 fixation and increases in growth, while ATX-A cellular quotas would be directly controlled by the growth rates of Dolichospermum. These findings will likely be useful for predicting how CHABs dominated by Dolichospermum and ATX-A production respond to differing nutrient regimes.

Materials and methods

Experimental design

Dolichospermum sp. strain 54 (ATX-A producer) is a non-axenic isolate from a southern Finnish lake (Rouhiainen et al., 1995) that was grown in batch cultures in the freshwater medium BG11 (Stainer et al., 1971) without fixed N (BG11-N) for several weeks prior to experimentation to promote N2 fixation. Immediately prior to experimentation, cells from these cultures, which were in early stationary phase, were enumerated (see below) and centrifuged at 3000 RCF for 10 min, the supernatant removed, and cell pellets resuspended in BG11-N to avoid changing the target fixed N concentrations in experimental treatments. 500 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 300 mL BG11 modified with different forms and concentrations of fixed N or without P were then inoculated with the concentrated Dolichospermum sp. 54 sample, and used for five experimental nutrient treatments, each with three replicates (n = 3) having an initial culture concentration of approximately 5 × 105 cells mL–1. Target cell densities were determined from the concentrated sample (C1V1 = C2V2), and fixed N was added post-inoculation. The five experimental treatments were: BG11 with ammonium chloride (NH4+ + P = 100 μM), urea (urea + P = 50 μM), or NaNO3 (NO3– + P = 100 μM) as nitrogen forms, BG11-N (-N + P, or the control), and BG11 without fixed nitrogen or phosphorus (-N-P). Potassium hydrogen phosphate concentrations (K2HPO4) were kept the same in all treatments receiving P (0.23 mM). Flasks were then placed in an incubator set at 21°C on a 14:10 light/dark cycle at ∼40 μmol photons m–2 s–1 and bubbled with ambient air passed through 0.2 μm HEPA filters at a rate of ∼200 mL min–1. Sample processing and culture maintenance began in the late morning (10:00 – 11:00) during the experiment. Cultures treated with fixed nitrogen were amended again with the same nitrogen species at the same starting concentration on days 3 through 6 of the 9-day experiment to ensure that the fixed N pool did not become depleted. While the starting dissolved N:P ratios of these treatments were less than that of Redfield (1958) in fixed N-amended treatments, concentrations of NO3– and NH4+ were kept the same to assure comparability between treatments and were kept relatively low (μM), as both NH4+ (Dai et al., 2008) and urea (Sakamoto et al., 1998) are toxic to cyanobacteria at high (mM) concentrations. Every day and prior to the final time point (day 9), 10 mL of sample was removed from each flask for cell density enumeration (5 mL) and for measuring photosynthetic efficiency (5 mL); an extra 6 mL was used to measure N2 fixation (5 mL) and alkaline phosphatase activity (1 mL). The experiment concluded after cultures had been in the exponential phase of growth for several days, differences in cell densities between treatments were apparent (Supplementary Figure 1), and −N-P cultures displayed signs of P-limitation (i.e., elevated alkaline phosphatase activity relative to the control and lower Fv/Fm relative to fixed N - amended cultures; see below).

Culture analyses

Cells were preserved in Lugol’s iodine each day then enumerated under an inverted Nikon Eclipse TS100 microscope using a gridded 1 mm2 Sedgewick Rafter counting chamber. Cell densities, which exhibited exponential growth as the experiment progressed (Supplementary Figure 1), were then used to determine maximum growth rates (μmax), measured as day−1 = (LN(N/N))/(t−t), where the difference in cell density (N) between days t2 and t1 represents the greatest (positive) change in cell density throughout the duration of the experiment (Guillard, 1973). At specific time points, cell density (cells mL–1) was normalized to both ATX-A concentrations (μg L–1) and the amount of N2 fixed (μmol N2-fixed L–1 day–1) to determine cellular quotas of ATX-A and N2 fixation rates per cell.

Dissolved fixed N samples were collected by passing sample through a pre-combusted (450°C) glass fiber filter (GF/F) and stored frozen (-20°C) until analysis on a Lachat Instruments autosampler (ASX-520). Specifically, nitrate was analyzed using the Greiss reaction following reduction of NO3– to NO2– using cadmium columns (Jones, 1984), while ammonium was analyzed using a revised version of the indophenol blue method (Parsons et al., 1984). NO3– and NH4+ analyses proceeded when the recovery of standard reference material (SPEX CertiPrep™) was at least 90 ± 10%. To measure Fv/Fm, or the maximum quantum efficiency of photosystem (PS) II, dark-adapted in vivo (F0) and DCMU (3,4-dichlorophenyl-1,1-dimethylurea)-enhanced in vivo fluorescence (Fm) was measured daily on a Turner Designs TD-700 fluorometer (Ex/Em = 340 – 500/>665 nm). Readings were blank-corrected using standard BG11 media (Harke and Gobler, 2013). DCMU blocks electron transfer between photosystems, stopping photosynthesis, and is a reliable indicator of stress in eukaryotic phytoplankton and cyanobacteria due to fixed N and/or P depletion (Parkhill et al., 2001; Simis et al., 2012). Samples were also collected from −N + P and −N-P cultures to measure alkaline phosphatase activity (APA), which is a reliable indicator of stress induced by the lack of PO43– in aquatic systems (Dyhrman et al., 2007), every other day. APA was measured on a Turner Designs TD-700 fluorometer (Ex/Em = 300 – 400/410 – 600 nm) using 4-methylumbelliferone phosphate (250 μM) as the substrate (Hoppe, 1983). APA measured using this method correlates significantly with the expression of the gene phoX that encodes for alkaline phosphatase in cyanobacteria (Harke et al., 2012).

N2 fixation rates were measured every other day using the acetylene reduction method (Capone, 1993). Briefly, acetylene (C2H2) is reduced by nitrogenase to ethylene, as one molecule of N2 is fixed for every four C2H4 molecules produced in Dolichospermum (Hardy et al., 1973; Jensen and Cox, 1983). Acetylene was made by reacting 7 grams of lab-grade calcium carbide (Fisher Scientific) with 700 mL of deionized water (Hyman and Arp, 1987; Beversdorf et al., 2013), with the resulting gas collected in Supelco Tedlar bags. The amount of ethylene produced was quantified using C2H4 standards made by injecting 1% ethylene in N2 (Airgas) into air-tight vials immediately prior to sample analysis. Acetylene was injected into the headspace of air-tight 10 mL vials containing samples, which were then placed into the incubator with experimental cultures for 3-4 h, after which a portion of the headspace was extracted and injected into a Trace 1310 Gas Chromatograph (Thermo Scientific). The amount of ethylene produced was determined using Chromeleon Chromatography Data System (CDS) software (Version 7.3).

For the final timepoint (day 9) of the experiment, 25 mL of sample from each flask was collected for anatoxin analysis by filtering water through a pre-combusted GF/F and stored frozen at −20°C. ATX-A was extracted using an acetonitrile:H2O:formic acid (80:19.9:0.1) mixture (Dell’Aversano et al., 2005). Extracts were then quantified via liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) using an Agilent 1200 series HPLC and Agilent 6410 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with a Peak Nitrogen generator #NM30LA (Peak Scientific, Inc. Billerica, MA). ATX-A was detected using qualifier and quantifier ions (Buckland et al., 2005; James et al., 2005) using Agilent MassHunter Qualitative Analysis software (version B.03.01) and quantified by normalization to the parent compound.

RNA isolation and sequencing

To characterize differential expression of the Dolichospermum sp. 54 transcriptome relative to the control, RNA was acquired using Millipore Sterivex filters (0.22 μm) at the end of the experiment (day 9), filtering 50 mL from each replicate per treatment (n = 3). After filtration, samples were flash frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C. Total nucleic acids were extracted using the cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) method (Dempster et al., 1999; Harke and Gobler, 2013). Briefly, 1 mL of CTAB lysis buffer was added to each frozen sample while still in the Sterivex filter, heated to 50°C, and returned to −80°C overnight. After placing frozen samples in a water bath set at 65°C, 750 μL of CTAB was carefully removed from each Sterivex filter using a syringe and transferred to an Eppendorf tube, centrifuged, extracted with 750 μL chloroform, precipitated with an isopropanol/sodium chloride solution, and centrifuged one final time.

The quality and quantity of sample nucleic acids were assessed using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer and a Qubit fluorometer in tandem with a dsDNA BR Assay kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions, then stored at −80°C. Total nucleic acid samples were treated with RNase-free DNase (Qiagen) to digest genomic DNA, and resulting total RNA was quantified using a Qubit? fluorometer and quality assessed using an Agilent QC Bioanalyzer. A relatively low amount of RNA was extracted from one of the −N-P replicates (∼3 ng μL–1) and was thus removed from analysis. Samples were then sent to Columbia University’s Next Generation Sequencing facility for sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 system, prior to which ribosomal RNA was depleted and sequencing libraries were prepared using a TruSeq Ribo-Zero Gold kit. 20 × 106 raw 100 bp single-end reads were sequenced per sample.

Read mapping and analysis

The quality of the raw reads was assessed using FASTQC (version 0.11.5). Through Trimmomatic (version 0.39), quality trimming was conducted on raw reads to remove adapter sequences and poor quality bases (Bolger et al., 2014). Trimming parameters were set as follows: SLIDINGWINDOW:4:15 − ILLUMINACLIP:adaptor_truseq.fasta:2:30:15 − MINLEN:30, with a custom made truseq adapter file. Cleaned, filtered, and trimmed reads were then assembled using Trinity (version v2.8.4) (Grabherr et al., 2011; Haas et al., 2013); the transcriptome assembly was evaluated using RNA-Seq. Clean reads from different treatments were first pooled and normalized using Trinity’s in silico normalization module, then assembled de novo into transcripts using Trinity’s single-end mode with default settings. The candidate open reading frames (ORFs) and deduced amino acid sequences were obtained using TransDecoder (version 5.5.01) using search results of the BLASTP (BLAST + version 2.9.0) and Hmmscan (HMMER version 3.2.1) databases. Diamond BLASTX was used to annotate transcripts against the UniProt_Swiss-Prot database (release 2020.01), using the genome of Anabaena sp. WA102 as a reference, and an e-value of 1e–3 to avoid getting low annotations and mismatches.

The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) was used to obtain KEGG orthology (KO) gene annotations from the UniProt_Swiss-Prot database. KEGG annotations were also obtained through the GHOSTX (Suzuki et al., 2014) search of KOALA (KEGG Orthology And Links Annotation) (Kanehisa et al., 2014). Both sets of KEGG IDs were then merged to get the maximum number of gene annotations. Read counts of transcripts were obtained with Kallisto (version 0.46.0) using default settings (Bray et al., 2016) by mapping the clean reads of each sample to the assembled transcriptome, and the transcript abundances were normalized to transcripts per million (TPM) values. In Sleuth (version 0.30.0), Kallisto counts were used to characterize differential gene expression, then aggregate normalized counts by KO ID (Pimentel et al., 2017). Gene transcripts were quantified using units of scaled reads per base, and Wald tests were performed in Sleuth to determine whether the experimental groups exhibited significant (false discovery rate/qval < 0.05) differential gene expression relative to the control (-N + P), which was determined based on beta (b) – values generated in Sleuth that represent biased estimators of log2-fold changes (Δ) in transcript abundance. A gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was also performed on the Kallisto counts to map transcripts to genes associated with certain biological, cellular, and molecular categories of genes associated with N and P metabolism, growth, and photosynthesis. Differential expression at the transcript level for each treatment relative to the control was first determined using Sleuth, then processed and mapped to gene categories using the GOStats (version 2.56.0) package (Falcon and Gentleman, 2007).

To characterize differential expression of genes associated with anatoxin synthesis, Trimmomatic reads were assembled into transcripts using SPAdes (version 3.11.1) (Bankevich et al., 2013; Nurk et al., 2013; Bushmanova et al., 2019) and annotated using Prokka (version 1.122) (Seeman, 2014). The annotated assembly and the Anabaena sp. 37 ATX-A - encoding gene sequences available on NCBI (Rantala-Ylinen et al., 2011), were then put through BLASTP to find which sequences in the assembly matched the genes belonging to the anatoxin synthetase gene (ana) cluster.

Statistical analyses and data visualization

Statistical analyses were done in R (Version 4.0.3) and graphing was done in both R and Microsoft Excel (Version 16.51). Fv/Fm and N2 fixation rate values for each replicate at each time point were averaged prior to being averaged with the values of other replicates from the same treatment. Using the dplyr package, a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to determine whether fixed N and P availability significantly affected growth rate, Fv/Fm, dissolved nutrient levels, ATX-A cell quota, N2 fixation rate, and normalized counts of ana transcripts. Tukey’s HSD tests using the agricolae package were then performed post hoc to determine whether differences among treatments were significantly different to each other. For two-way ANOVAs, the Shapiro-Wilk and Fligner-Killeen tests were used to confirm that the data passed normality and homogeneity of variance, respectively. Transcript data for anaE and anaF exhibited non-normal distribution under Shapiro-Wilk but did exhibit normality (p > 0.05) using Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) non-parametric tests. Significant differences in APA activity were compared between the control (-N + P) and -N-P across time using a Student’s paired t-test. Linear regression analyses (F-tests) were performed using the stats package to determine whether there were correlations between N2 fixation and growth rate, and to determine whether ATX-A content covaried with nitrogenase activity and growth rate. In all cases, an alpha level of 0.05 was utilized.

To visualize the overall expression of genomes among treatments, a non-metric multidimensional scaling (nMDS) plot of TPM values was created using the vegan package (Version 2.5-73). To test for statistically significant differences between treatments, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were drawn around experimental groups in the nMDS plot. Furthermore, a two-way permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was performed on a Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrix using the adonis2 package to determine whether N and/or P availability significantly influenced global gene expression. As stated before (see Read mapping and analysis), Wald tests were also performed using the sleuth package to determine whether the experimental groups exhibited significant (false discovery rate/qval < 0.05) differential gene expression relative to the control (-N + P). Global results in differential expression relative to the control were visualized using Bland-Altman (MA) plots, with b-values, or log2-fold changes (Δ) in expression, plotted as a function of mean abundance of annotated gene transcripts. The data were further examined for genes associated with nitrogen metabolism/fixation and phosphorus assimilation using the software Morpheus (Broad Institute4) to generate heatmaps. Hypergeometric distribution tests (padj < 0.05) were performed using the GOstats package to determine whether gene categories associated with growth, N and P assimilation, and photosynthesis were significantly enriched relative to the control.

Results

Growth rate, nutrient availability, and physiological indicators of nutrient acquisition and stress

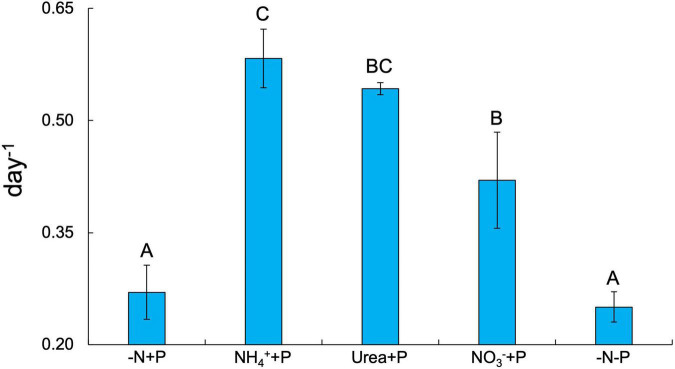

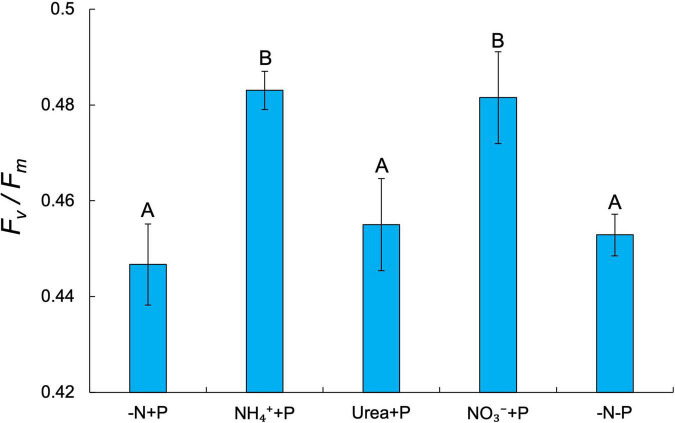

Fixed N availability alone had a significant positive effect on the maximum growth rates (μmax = day–1) of Dolichospermum sp. 54 (Two-way ANOVA; p < 0.001), as cultures amended with NH4+ (0.58 ± 0.04 day–1), urea (0.54 ± 0.01 day–1), and NO3– (0.42 ± 0.06 day–1) all exhibited significantly higher μmax than those of the control (-N + P; 0.27 ± 0.04 day–1) and −N-P (0.25 ± 0.02 day–1) cultures (Tukey’s HSD; p < 0.05; Figure 1). NH4+ + P cultures exhibited significantly faster growth rates relative to NO3– + P cultures (Tukey’s HSD; p < 0.05; Figure 1). Dissolved NO3– and NH4+ concentrations on days 6 and 7 of the experiment affirmed that the growth rates of fixed N-amended cultures were not limited by fixed N supply (Supplementary Table 1). PS-II photosynthetic efficiency (Fv/Fm) was significantly altered by the availability of fixed N (Two-way ANOVA; p < 0.001), but not P, though only two of the fixed N-enriched treatments, NH4+ + P (0.48 ± 0.004 day–1) and NO3– + P (0.48 ± 0.01 day–1), exhibited significantly (Tukey’s HSD; p < 0.05) higher average Fv/Fm values than −N + P cultures (0.45 ± 0.01; Figure 2). Furthermore, on days 3-8 of the experiment, Fv/Fm values of NH4+ + P and NO3– + P were higher than those of urea + P cultures (Supplementary Figure 2). −N-P cultures exhibited significantly (Student’s paired t-test; p < 0.05) greater APA activities relative to the control during all time points measured (Supplementary Figure 3).

FIGURE 1.

Maximum growth rates (μmax; day–1) across all experimental groups. Error bars represent standard deviation. Letters above bars represent significant differences between experimental groups (Two-way ANOVA; Tukey’s HSD post hoc; p < 0.05).

FIGURE 2.

Photosystem II photosynthetic efficiency (Fv/Fm) across treatments. Error bars represent standard deviation. Letters above bars represent significant differences between experimental groups (Two-way ANOVA; Tukey’s HSD post hoc; p < 0.05).

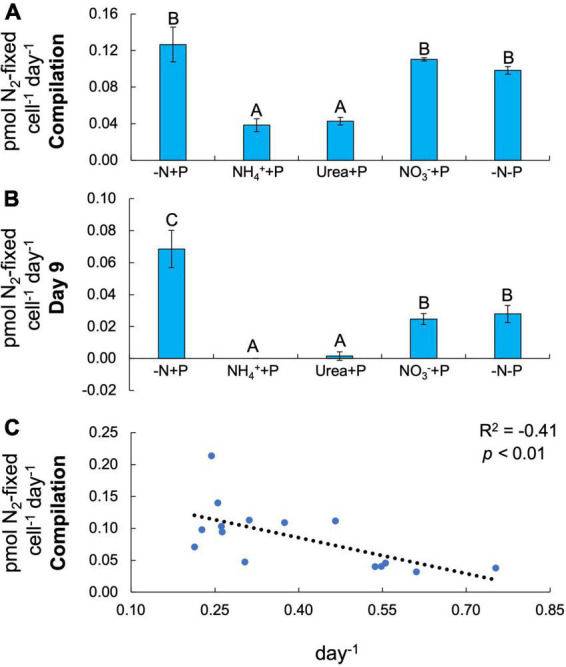

N2 fixation rates

Both fixed N (Two-way ANOVA; p < 0.001) and P (p < 0.01) availability significantly altered N2 fixation rates in Dolichospermum sp. 54 (Figure 3A). Amendments with reduced N compounds significantly decreased (Tukey’s HSD; p < 0.05) the average N2 fixation rate (NH4+ + P = 0.04 ± 0.01 pmol N2-fixed cell–1 day–1; urea + P = 0.04 ± 0.004 pmol N2-fixed cell–1 day–1) relative to that of control cultures (-N + P; 0.13 ± 0.02 pmol N2-fixed cell–1 day–1; Figure 3A). On the final day of the experiment, NO3– + P (0.02 ± 0.003 pmol N2-fixed cell–1 day–1) and −N-P (0.03 ± 0.01 pmol N2-fixed cell–1 day–1) cultures exhibited significantly (Tukey’s HSD; p < 0.05) lower N2 fixation rates relative to the control (0.07 ± 0.01 pmol N2-fixed cell–1 day–1) and significantly higher N2 fixation rates relative to NH4+ + P (below detection limit) and urea + P (0.002 ± 0.003 pmol N2-fixed cell–1 day–1) cultures (Figure 3B). Across all cultures, there was a significant negative correlation between N2 fixation and growth rates (F-test; R2 = −0.41, p < 0.01; Figure 3C).

FIGURE 3.

N2 fixation rates normalized to cell density (pmol N2-fixed cell–1 day–1). (A) N2 fixation rates on days 1, 3, 5, and 9 averaged. (B) Final timepoint (day 9) N2 fixation rates. Letters above bars represent significant differences between experimental groups (Two-way ANOVA; Tukey’s HSD post hoc; p < 0.05). (C) N2 fixation as a function of maximum growth rate (μmax; day–1). Values in the upper right-hand corner represent the coefficient of determination (R2) and the significance (p-value) of the linear regression.

Anatoxin-a cell quotas

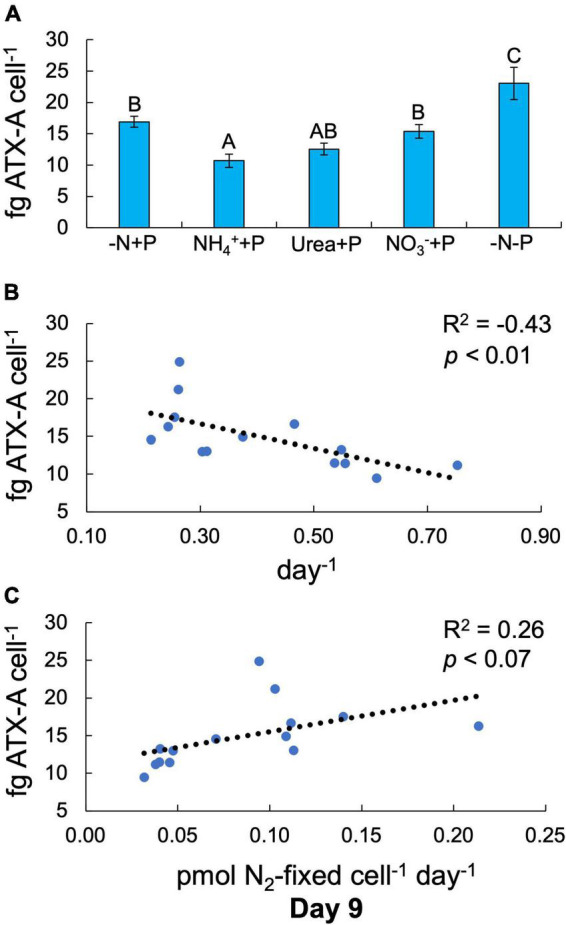

Fixed N (Two-way ANOVA; p < 0.001) and P (p < 0.01) availability both significantly altered cellular ATX-A content (Figure 4). Of all experimental treatments, only NH4+ + P and −N-P exhibited significantly lower (10.7 ± 1.06 fg ATX-A cell–1) and higher (23.0 ± 2.59 fg ATX-A cell–1) cellular ATX-A quotas than the control (-N + P; 16.9 ± 0.88 ATX-A fg cell–1), respectively (Tukey’s HSD; p < 0.05; Figure 4A). ATX-A content was significantly (F-test; R2 = −0.43, p < 0.01; Figure 4B) negatively correlated with growth rate, while ATX-A content exhibited a positive, marginally significant (F-test; R2 = 0.26, p < 0.07; Figure 4C) correlation with N2 fixation rate.

FIGURE 4.

Anatoxin-a (ATX-A) content per cell (fg ATX-A cell–1) across treatments at the final timepoint [day 9; (A)]. Error bars represent standard deviation. Letters above bars represent significant differences between experimental groups (Two-way ANOVA; Tukey’s HSD post hoc; p < 0.05). Anatoxin-a (ATX-A) content per cell as functions of maximum growth rate [(B); μmax; day–1] and N2 fixation (C). Values in the upper right-hand corners represent coefficients of determination (R2) and the significance (p-value) of linear regressions.

Global transcriptomic changes

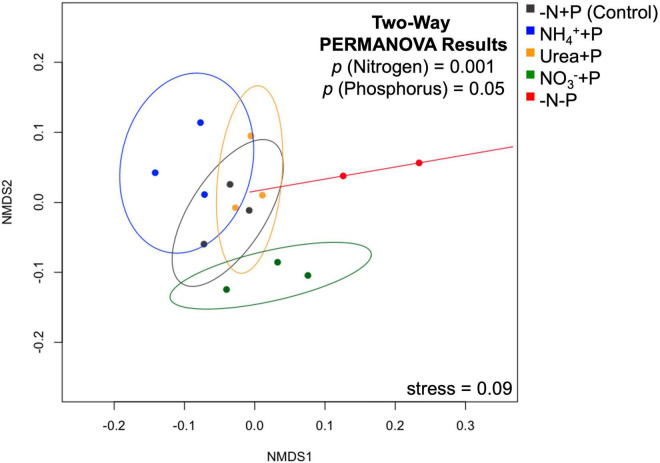

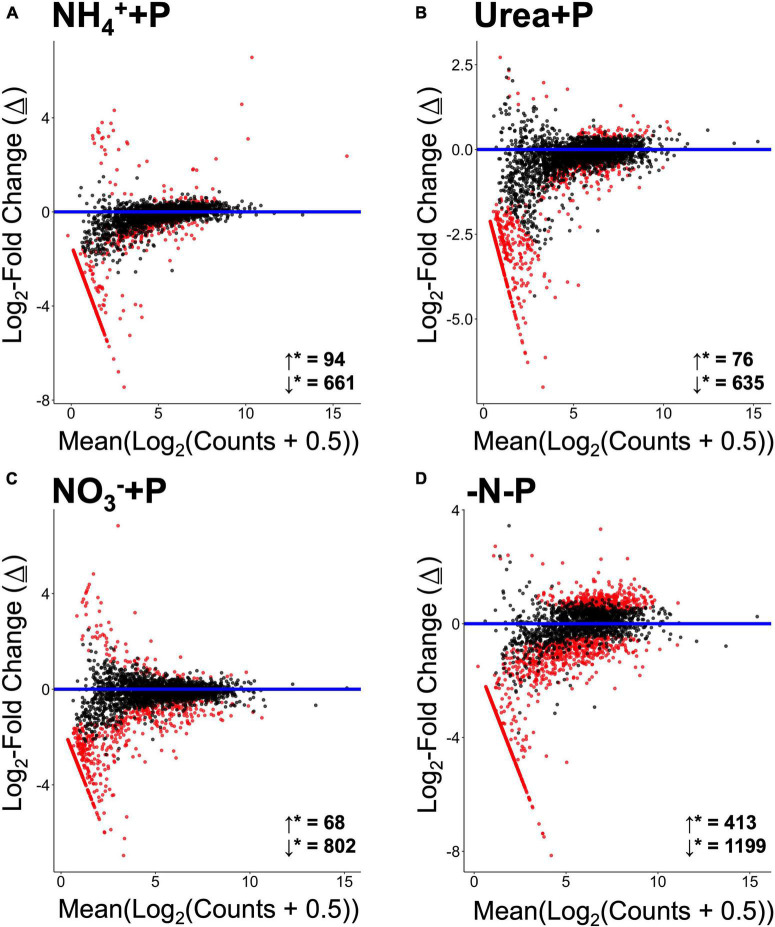

Non-metric multi-dimensional (nMDS) scaling of normalized read counts mapped to the Trinity assembly revealed considerable overlap among transcriptomes, particularly with respect to NH4+ + P, which overlapped with urea + P and the control group (-N + P; Figure 5). The transcriptomes of −N-P cultures, in contrast, were significantly different from those of all other treatments (CI = 95%; p < 0.05) except those of NH4+ + P. Furthermore, the transcriptomes of NO3– + P were significantly different from those of NH4+ + P and −N-P cultures (CI = 95%; p < 0.05). Fixed N (p = 0.001) and P (p = 0.05) availability significantly (Two-way PERMANOVA) influenced differences in global gene expression among treatments. All treatments displayed substantially more annotated transcripts that were significantly lower in abundance than transcripts that were significantly higher in abundance relative to the control (Wald test; qval < 0.05; Figure 6). The transcriptomes of NH4+ + P, NO3– + P, and urea + P had fewer than 100 transcripts that were significantly more abundant and ∼630 - 810 transcripts that were significantly less abundant (Figures 6A–C). The transcriptomes of −N-P had the largest number of differentially expressed transcripts (Wald test; qval < 0.05) with ∼400 and ∼1200 transcripts significantly more and less abundant, respectively (Figure 6D).

FIGURE 5.

Non-metric multi-dimensional scaling (nMDS) plot of normalized read counts among treatments mapped to the Trinity assembly. Stress value in the lower left-hand corner indicates the disagreement between the plot configuration and the predicted values from the regression. Ellipses represent 95% confidence intervals, with the results of a two-way PERMANOVA (p < 0.05) on the dissimilarity matrix of the data presented in the upper right-hand corner, representing the significance of fixed nitrogen and phosphorus availability on relative differences.

FIGURE 6.

MA plots representing log2-fold changes (Δ) in gene expression of experimental treatments [(A) = NH4+ + P, (B) = Urea + P, (C) = NO3– + P, (D) = −N-P) relative to the control (−N + P). Change is plotted relative to base mean expression of gene transcripts normalized, log2-transformed, annotated and aggregated relative to KO numbers. Significantly differentially upregulated (↓*) genes and downregulated (↓*) genes are indicated directly above the x-axes. Gene transcripts exhibiting statistically significant differences in expression (False Discovery Rate/qval < 0.05) are colored red. Statistical analyses were performed in Sleuth using the Wald test.

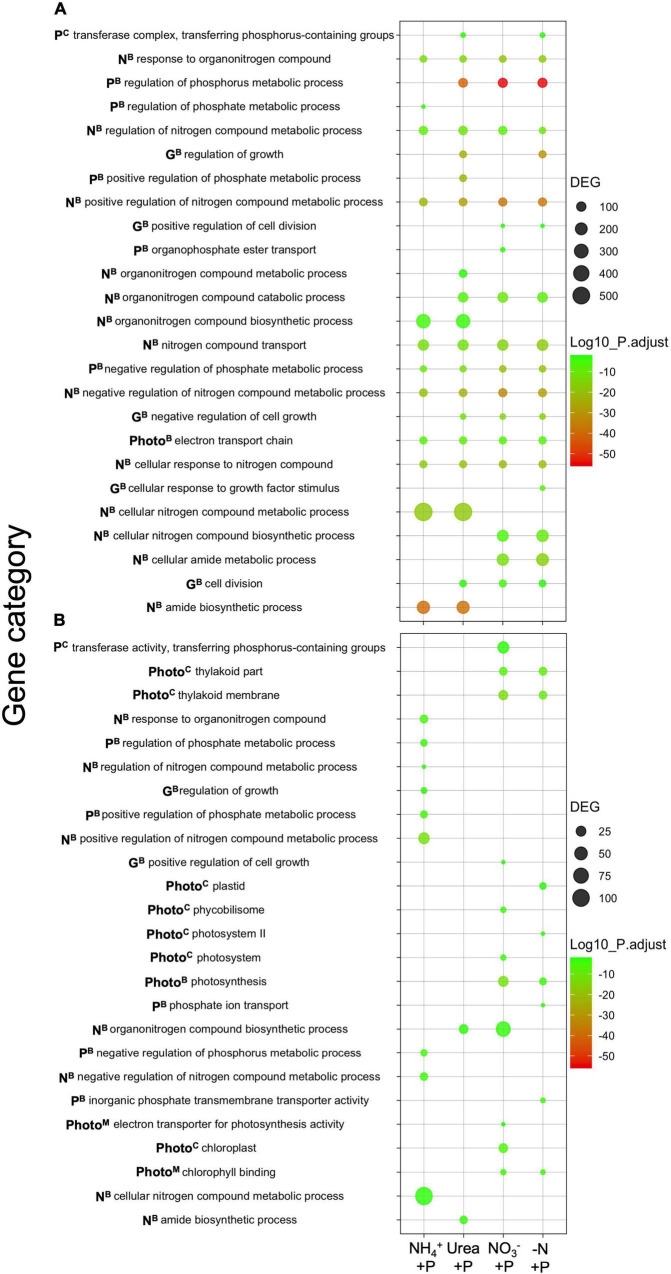

Enriched gene categories and differentially expressed genes

Among experimental treatments, the number of significantly downregulated gene categories (hypergeometric distribution analysis; padj < 0.05) relative to the control (−N + P) was higher than the number of upregulated gene categories (Figure 7). The transcriptomes of NH4+ + P exhibited the smallest number of significantly downregulated gene categories associated with fixed N and P transport/metabolism (11; Figure 7A). Transcriptomes in this treatment also had the second highest number of significantly upregulated gene categories (9) after those of NO3– + P (11; Figure 7B). Only the transcriptomes of NH4+ + P and urea + P cultures exhibited significant downregulation of organonitrogen biosynthesis, cellular N metabolism, and amide biosynthesis gene categories; these gene categories exhibited an average number of ∼300, ∼500, ∼200 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), respectively, in both treatments. These genes comprised roughly 18% of the total number (5597) of DEGs that were downregulated across all experimental treatments (Figure 7A). Of these, NH4+ + P exhibited significant upregulation of 5 out of 7 gene categories associated with N metabolism and biosynthesis, while only 2 and 1 of these gene categories were upregulated in urea + P and NO3– + P, respectively, and −N-P exhibited no such enrichment (Figure 7B). NO3– + P and −N-P were the only treatments to exhibit significant downregulation of cellular N biosynthesis and cellular amide metabolism gene categories; both gene categories in NO3– + P and −N-P exhibited ∼200 DEGs (Figure 7A).

FIGURE 7.

Differentially expressed categories of genes [(A) = 4-fold downregulated, (B) = 4-fold upregulated] relative to the control (−N + P). Results are from transcript-based Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis. The significant differential expression of genes was determined using Sleuth (Wald test; qval < 0.05), and gene categories were tested for significant differential expression using GOenrich (hypergeometric distribution analysis; padj < 0.05). Padj values were Log10-transformed for scaling purposes, and green - red colorations corresponded to lower - higher degrees of significance. Gene categories plotted were those associated with nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) assimilation, growth (G), as well as photosynthesis (Photo), while superscripts correspond to biological (B), cellular (C), and molecular (M) gene categories. The number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in gene categories are represented by circle size.

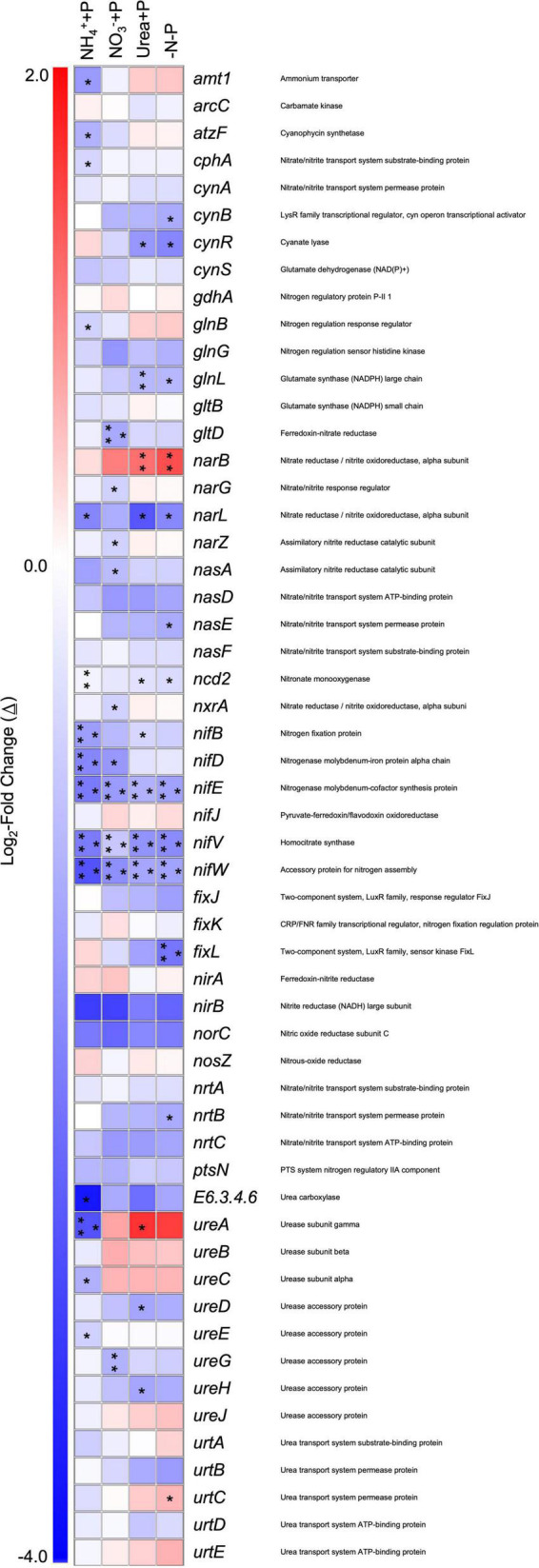

Across all experimental treatments, a majority (> 90%) of annotated transcripts associated with N metabolism were significantly lower (Wald test; qval < 0.05) in abundance relative to the control (−N + P; Figure 8). Genes involved in NO3– metabolism (narB, narG, narL) were significantly differentially expressed in at least one of the experimental treatments. NO3– + P (Δ≅ + 1.11, qval < 0.01) and −N-P (Δ≅ + 1.38, qval < 0.01) cultures significantly increased the number of transcripts for narB, which encodes for ferredoxin−Nitrate reductase. The number of transcripts for narL, which encodes for the NO3–/NO2– response regulator, and narG, which encodes the Δ-subunit for NO3–/NO2– oxidoreductase, were, respectively, significantly lower in NH4+ + P (Δ≅−1.89, qval < 0.05) and urea + P (Δ≅−0.70 qval < 0.05) transcriptomes (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8.

Differential expression of gene transcripts associated with nitrogen metabolism and acquisition in experimental groups relative to the control/−N + P. Heatmap representing log2-fold changes (Δ) in nitrogen metabolism/acquisition gene expression in experimental groups with their corresponding gene products. Red or blue coloration corresponds to up or down – regulation of genes relative to the control, respectively. Statistical analyses were determined on transcriptomic data post-Sleuth analysis using the Wald test (qval < 0.05 = *, 0.01 = **, 0.001 = ***).

The number of transcripts for ureA, which encodes for a subunit of urease, and urtC, which encodes for the urea transport system permease, significantly (Wald test; qval < 0.05) increased in the transcriptomes of NO3– + P (Δ≅ + 1.60) and −N-P (Δ≅ + 0.58), respectively, relative to the control (−N + P; Figure 8). In contrast, ureA exhibited a significantly lower number of transcripts in the transcriptomes of NH4+ + P (Δ≅−2.68, qval < 0.001), as did ureC (Δ≅−1.23, qval < 0.05), and other genes that encode for enzymes associated with urea degradation, namely atzF (allophonate hydrolase; Δ≅−1.20, qval < 0.05) and E6.3.4.6 (urea carboxylase; Δ≅−3.62, qval < 0.05). Significant differential expression (Δ≅−1.58, qval < 0.05) of amt1, which encodes for an ammonium transporter, was only observed in the transcriptomes of NH4+ + P, with transcripts being lower in abundance. Other N metabolism genes that were differentially expressed include cphA, which encodes for cyanophycin synthetase, exhibited a significantly lower number of transcripts in the transcriptomes of NH4+ + P (Δ≅−0.67, qval < 0.05), as well as genes that encode for cyanase, cynB (Δ≅−1.31, qval < 0.05) and cynR (Δ≅−1.88, qval < 0.05), which exhibited significantly lower transcripts in the transcriptomes of −N-P. The number of transcripts for glutamine synthetase-encoding genes (gln) was significantly lower in the transcriptomes of NH4+ + P (glnB; Δ≅−0.70, qval < 0.05), NO3– + P (glnL; Δ≅−1.12, qval < 0.01), and −N-P (glnL; Δ≅−1.13, qval < 0.05), while gltD was the only gene involved in glutamate synthesis to exhibit a significantly lower transcript abundance, specifically in the transcriptomes of urea + P (Δ≅−1.35, qval < 0.001). Significantly lower numbers of transcripts (Wald test; qval < 0.001) of nifE, nifV, and nifW, which encode for nitrogenase subunits, were observed in all experimental treatments (Figure 8). Significantly lower numbers of transcripts of nifB (Δ≅−1.52, qval < 0.001) and nifD (Δ = −1.88, qval < 0.001) were observed in NH4+ + P, while the former and latter genes were present at significantly lower transcript abundances in NO3– + P (Δ≅−0.64, qval < 0.05) and urea + P (Δ≅−1.62, qval < 0.05), respectively, compared to the control. Finally, the transcriptomes of −N-P exhibited significantly lower transcript abundance of fixL (Δ≅−2.15, qval < 0.001; Figure 8), which encodes for a putative oxygen sensor.

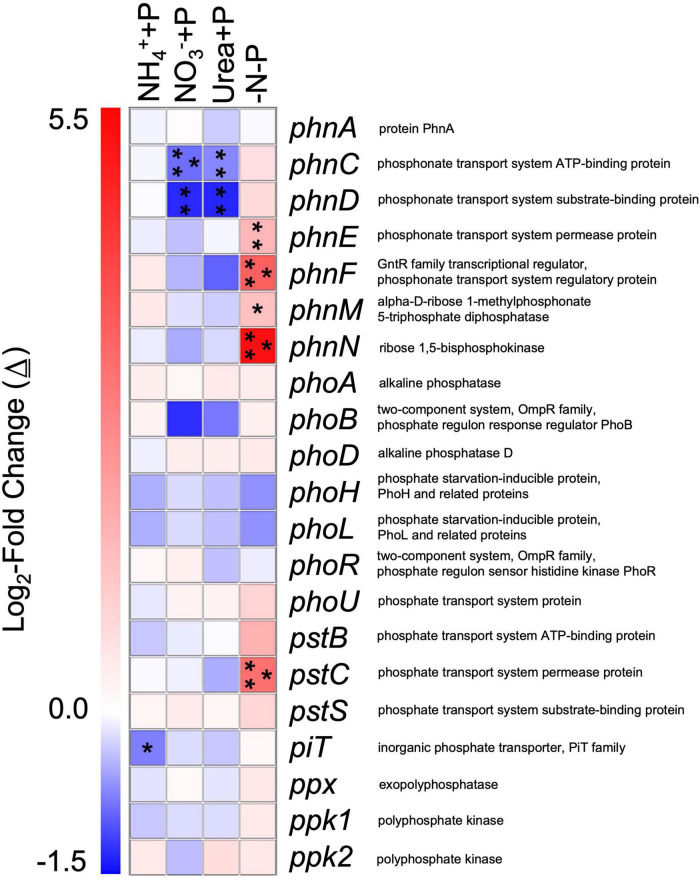

Genes associated with phosphorus (P) assimilation that were differentially expressed relative to the control (−N + P) included those that belong to the phn, pho, and pst clusters (Figure 9). For cultures amended with fixed N, genes that exhibited a significant change (Wald test; qval < 0.05) in transcript abundance were always lower than those of the control, while the transcriptomes of −N-P were the only ones to exhibit a significantly greater number of transcripts relative to the control, specifically for four phn genes and pstC (Figure 9). While non-significant, polyphosphate synthesizing (ppk1, Δ≅ + 0.47) and degradation (ppx, Δ≅ + 0.49) – encoding genes also exhibited the highest average increase in transcript number in the transcriptomes of −N-P than any other treatment relative to the control (Wald test; q > 0.05; Figure 9).

FIGURE 9.

Differential expression of gene transcripts associated with phosphorus acquisition and metabolism in experimental groups relative to the control/−N + P. Heatmap representing log2-fold changes (Δ) in phosphorus metabolism/acquisition gene expression in experimental groups with their corresponding gene products. Red or blue coloration corresponds to up or down – regulation of genes relative to the control, respectively. Statistical analyses were determined on transcriptomic data post-Sleuth analysis using the Wald test (qval < 0.05 = *, 0.01 = **, 0.001 = ***).

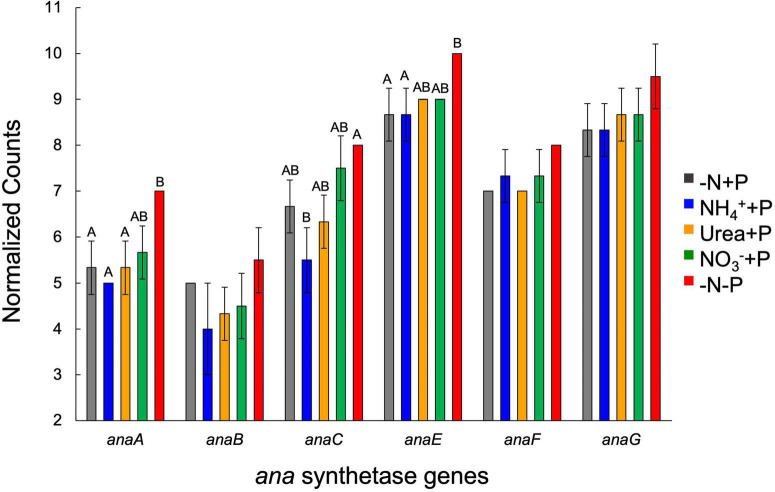

Of the genes associated with ATX-A synthesis, transcript abundances of anaA, anaE, and anaF were significantly (Two-Way ANOVA; p < 0.05) altered by P availability, while anaC transcript numbers were significantly affected by fixed N and P availability (Figure 10). −N-P cultures exhibited a significantly (Tukey HSD; p < 0.05) higher number of anaA transcripts (7.0 ± 0.0) relative to those of the control (−N + P; 5.3 ± 0.6) as well as NH4+ + P (5.0 ± 0.0) and urea + P (5.3 ± 0.6) cultures, while the number of anaE transcripts in −N-P cultures (10.0 ± 0.0) was significantly higher than those of the control and NH4+ + P (8.7 ± 0.6). The number of anaC transcripts was highest in −N-P cultures (8.0 ± 0.0) and was significantly higher than that of NH4+ + P cultures (5.5 ± 0.7, Figure 10).

FIGURE 10.

Expression (normalized counts) of genes involved in anatoxin synthesis across treatments at the final timepoint (day 9). Error bars represent standard deviation. Letters above bars represent significant differences between experimental groups (Two-way ANOVA; Tukey’s HSD post hoc; p < 0.05).

Discussion

This study characterized the effects of NH4+, urea, and NO3– as well as P availability on Dolichospermum sp. 54. Relative to the control (−N + P), reduced N species significantly increased growth rates and decreased N2 fixation rates (NH4+ + P and urea + P), ATX-A cellular quotas (NH4+ + P), as well as nif (NH4+ + P and urea + P) transcript abundances. P depletion did not affect growth rate but significantly enhanced ATX-A cellular content and ana transcript abundance. We also found a significant negative correlation between ATX-A concentration and growth rate.

Effects of fixed N and P availability on growth and photosynthetic activity

Dolichospermum sp. 54 amended with fixed N exhibited significantly higher maximum growth rates (NO3–, NH4+, urea) and Fv/Fm (NO3– and NH4+) relative to the control (−N + P) and −N-P cultures. NH4+ + P and NO3– + P were also the only experimental treatments to exhibit significant upregulation of gene categories associated with growth. It has been well established with other Dolichospermum (Rhee and Lederman, 1983; Mishra, 1997; Zulkefli and Hwang, 2020) and Nostocales (Presing et al., 1996; Ammar et al., 2014) isolates that NH4+ and NO3– significantly increase growth and decrease N2 fixation rates, though NH4+ is generally considered more effective than NO3– in affecting these physiological processes (Stacey et al., 1977; Elder and Parker, 1984). This is not always the case, however, as some members of this order may prefer NO3– and urea (Stucken et al., 2014; Qian et al., 2017; Erratt et al., 2018) or even fixed N-deplete conditions (Velzeboer et al., 2001; Molot, 2017) over NH4+ for growth. The considerable diversity in responses to fixed N among Nostocales stresses the importance of determining how multiple fixed N compounds affect other members of this order, particularly toxin producers such as Dolichospermum sp. 54. NO3– must be reduced to nitrite (NO2–) and again to NH4+ before entering anabolic pathways (Herrero and Flores, 2018). The Fv/Fm of NO3– + P was not significantly different from that of NH4+ + P and was the only fixed N-amended treatment to exhibit significant upregulation of photosynthetic gene categories. It is plausible that a significant fraction of the reductants produced by the photosynthetic light reactions in this treatment were consumed by NO3– reduction, thus keeping photosynthetic efficiency high, but resulting in a lowered growth rate relative to NH4+-grown cultures (Flores et al., 1983, 2005).

Urea + P cultures exhibited growth rates that were significantly enhanced relative to the control but not significantly different than those of NH4+ + P or NO3– + P. Strains of CHAB taxa such as Microcystis and Dolichospermum grown on urea often exhibit enhanced growth rates, toxin production, and/or amino acid biosynthetic rates relative to cells grown with NH4+ or NO3– (Qian et al., 2017; Erratt et al., 2018; Krausfeldt et al., 2019). Aside from two NH3 molecules, urea hydrolysis also yields one CO2 molecule (Mobley and Hausinger, 1989; Valladares et al., 2002; Veaudor et al., 2019). While urea is potentially both a source of fixed N and carbon for cyanobacterial growth (Krausfeldt et al., 2019), our findings suggest that the increase in Dolichospermum sp. 54 growth on this reduced N compound was largely due to the ability to utilize NH3 rather than CO2.

Fixed N and P availability effects on N2 fixation

While N2 fixation can give Dolichospermum spp. and other Nostocales taxa a competitive edge over non-diazotrophic cyanobacteria under fixed N-limiting conditions, nitrogenase activity is an energetically demanding process that generally comes at the cost of higher growth rates (Willis et al., 2016; Herrero and Flores, 2018; Wannicke et al., 2021). Traditionally speaking, the productivity of non-diazotrophic phytoplankton was thought to be primarily limited by P (Smith, 1983, 2016; Schindler et al., 2008). Considerable evidence collected over the last decade or so indicates that this is not necessarily the case, as N2 fixation alone is insufficient to supply CHAB taxa with N levels sufficient in order to initiate blooms (Scott and McCarthy, 2010; Hellweger et al., 2016; Hayes et al., 2019). While this concept is primarily applied to non-diazotrophic cyanobacteria, our findings indicate that diazotrophs such as Dolichospermum exhibit a substantially greater preference for fixed N assimilation over nitrogenase activity, and thus likely play a markedly less important role in supplying newly fixed N to nitrogen-replete freshwater ecosystems during bloom events. The significantly enhanced growth rates of Dolichospermum sp. 54 cultured with NO3–, NH4+, and urea reported in this study further complements the findings of other studies that have documented Nostocales blooms when fixed N concentrations are high (Chaffin et al., 2019, 2020; Gamez et al., 2019).

N2 fixation rates of cultures amended with reduced fixed N (NH4+ and urea) were significantly lower than those of any other group for the entire experiment, while the N2 fixation rates of NO3– + P and −N-P were significantly higher than those of the reduced N treatments. These observations, as well as the significant negative correlation between N2 fixation rate and growth rate, were consistent with prior studies (Mickelson et al., 1967; Stacey et al., 1977; Ge et al., 1990; Mekonnen et al., 2002). Despite being grown under P-deplete conditions, −N-P cultures exhibited N2 fixation rates that were not different from those of the control. The −N-P cultures may have maintained relatively high N2 fixation rates over the course of the experiment by hydrolyzing internal P stores (Gerber and Wickstrom, 1990; Burut-Archanai and Powtongsook, 2017), as their transcriptomes exhibited the greatest increase in transcript abundance of polyphosphate synthesis (ppk1) and degradation (ppx) - encoding genes (Akiyama et al., 1993; Sanz-Luque et al., 2020) of the experimental treatments relative to the control. This, coupled with significantly enhanced APA activity in −N-P relative to control (−N + P) cultures, likely facilitated sustained growth and N2 fixation rates that matched the control during the experiment, and further reinforces the widely accepted notion that Nostocales such as Dolichospermum have multiple strategies to handle the stresses of P-limitation (Isvanovics et al., 2000; Wu et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2018).

The N2 fixation rates of NO3– + P cultures were also similar to those of −N treatments when averaged over the entire experiment, strongly indicating that NO3– assimilation and nitrogenase activity are utilized simultaneously (Bone, 1971; Elder and Parker, 1984). Supporting this notion, other Dolichospermum strains were still reported to exhibit detectable nitrogenase activities when grown at particularly high (1–10 mM) NO3– concentrations, whereas those grown at the same or lower concentrations of NH4+ did not. These studies did not, however, report significantly enhanced growth rates in Dolichospermum amended with NH4+ relative to those grown on NO3– (Meeks et al., 1983; Sanz et al., 1995; Mekonnen et al., 2002), while another study reported that NH4+ derived from NO3– reduction, not NO3– itself, is ultimately responsible for the suppression of nitrogenase activity (Ramos and Guerrero, 1983). Other studies have reported significantly higher photosynthetic O2 evolution (Mishra, 1997) and growth rates (Zulkefli and Hwang, 2020) in NH4+-grown relative to NO3–-grown Dolichospermum, though in the latter study heterocyst density was significantly higher in NH4+-grown cultures, suggesting that N2 fixation may have been significantly higher. These findings, coupled with differences in growth rate, Fv/Fm, and N2 fixation rate with respect to fixed N type, reveal how NO3–, NH4+, and urea differentially alter physiological processes in Dolichospermum.

Differential expression of genes associated with diazotrophy both supported observations regarding N2 fixation rates and further provided deeper physiological insight regarding this process. Transcripts of nifB and nifD were both significantly lower in NH4+ + P, while the former and latter genes were only significantly downregulated in NO3– + P and urea + P, respectively. The gene nifB is further associated with Fe-Mo cofactor assemblage (Curatti et al., 2007), while nifD encodes for the ɑ-chain for nitrogenase’s Fe-Mo protein (Dos Santos et al., 2012). Significantly lower transcript abundance of Dolichospermum sp. 54 nif genes in response to NH4+ amendment and/or PO4– depletion is consistent with previous findings in strains of the same genus. While NO3– was also reported to have less of an effect on nif gene expression than NH4+ in these findings (Helber et al., 1988; Martin−Níeto et al., 1991), transcriptional changes for multiple genes belonging to this cluster in response to the availability of P and multiple fixed N compounds in other Dolichospermum taxa have been poorly characterized. It was also shown that when Dolichospermum is grown under fixed N-replete or P-deplete conditions, nifE and nifV, which encode Fe-Mo cofactor proteins (Hawkes et al., 1984; Ugalde et al., 1984), and accessory protein-encoding nifW (Nonaka et al., 2019) are all downregulated. Finally, the significant downregulation of nifD in NH4+P and urea + P cultures, which also exhibited the lowest N2 fixation rates among treatments, is likely a reliable indicator of repressed N2 fixation when Dolichospermum are actively utilizing either N species.

Effect of fixed N and P availability on ATX-A production

Anatoxin-a (ATX-A) is a highly potent neurotoxin produced by freshwater cyanobacteria with a broad geographic distribution (Devlin et al., 1977; John et al., 2019; Österholm et al., 2020), yet the factors that control the production of this toxin are largely unknown. Several studies suggest that fixed N (Rapala et al., 1993; Gagnon and Pick, 2012) and/or P (Rapala and Sivonen, 1998; Toporowska et al., 2016) availability regulate ATX-A production. There is also evidence to suggest that ATX-A content in cells is controlled by growth rate, which subsequently regulates the partitioning of toxins into daughter cells (Heath et al., 2016), a concept known as the growth differentiation balance hypothesis (Herms and Mattson, 1992). Significant increases (−N-P) and decreases (NH4+ + P) in the cellular ATX-A content of Dolichospermum sp. 54 relative to the control (−N + P) and the significant negative correlation between ATX-A cell quota and growth rate suggests that toxin concentration was driven by division rate. However, expression of the anatoxin synthetase gene (ana) cluster indicates that factors other than growth rate regulate anatoxin production. Transcripts of anaA as well as anaC-F were significantly more abundant under P-deplete conditions, indicating cells were actively increasing toxin synthesis in response to nutrient-limited stress and did not simply accumulate more ATX-A since cells were dividing more slowly. The genes anaA and anaC encode proteins associated with thioesterase and proline adenylation, respectively, while anaE and anaF both encode for type I polyketide synthases (Rantala-Ylinen et al., 2011). Of the four genes, anaC best predicted variance in ATX-A cellular content among treatments, as both toxin quota and transcript abundance of anaC were significantly lower due to NH4+ enrichment and increased in response to P depletion. These data, when considered with reports of anaC expression exhibiting a significant negative relationship with dissolved carbon-to−Nitrogen (C:N) ratios (Tao et al., 2020), suggests that anaC expression and subsequent ATX-A production is highly sensitive to fixed N availability. Ecologically speaking, such an active process could serve as an defense mechanism against grazers (Toporowska et al., 2014; Anderson et al., 2018) or an allelopathic strategy against other phytoplankton (Kearns and Hunter, 2001; Chia et al., 2018, 2019), particularly if anatoxin-producing cyanobacteria are subjected to conditions unsuitable for them to achieve optimal growth rates (Harland et al., 2013; Heath et al., 2016).

The toxin content of Dolichospermum sp. 54 also exhibited a positive correlation (p < 0.06) with nitrogenase activity, which was driven by experimental treatments with lower growth rates exhibiting higher N2 fixation rates and cellular toxin content. The manner in which anatoxin synthetase may interact with other biochemical pathways is poorly understood (Rantala-Ylinen et al., 2011). However, given that different N forms alter growth, photosynthesis, and toxin production in Dolichospermum sp. 54 and other cyanobacteria (Harke et al., 2016; Erratt et al., 2018), understanding how nitrogenase activity might directly influence anatoxin production is warranted. To our knowledge, no study has investigated whether nitrogenase activity influences ATX-A synthesis. It is also important to note that other Nostocales taxa have exhibited significantly higher ATX-A concentrations and growth rates when grown on urea rather than NH4+ and NO3– (Qian et al., 2017; Tao et al., 2020). Urea + P cultures exhibited no significant difference in ATX-A cell quota relative to the control. This suggests that the ability for cyanobacteria to increase anatoxin production when using urea as a fixed N source may be dependent on whether they can fix CO2 derived from urease activity (Krausfeldt et al., 2019), as ATX-A is a toxin with a high C:N ratio (Van de Waal et al., 2014). Tao et al. (2020), who observed significantly higher growth rates and ATX-A quotas in the Nostocales taxon Cuspidothrix issatschenkoi when cultures were grown on urea relative to other fixed N sources, suggested as much in their discussion. Consistent with our findings, they further reported that Fv/Fm was significantly lower in urea-grown cultures than those grown on NO3– (Tao et al., 2020), which further reinforces the notion that reductants from photosynthetic light reactions can be used to reduce NO3– (Flores et al., 1983, 2005) but not convert urea to NH4+.

Global transcriptomic changes in response to fixed N and P availability

The transcriptomes of fixed N-amended cultures exhibited considerable similarity to each other and to the control, while the transcriptomes of −N-P were the most dissimilar from other treatments and exhibited the greatest number of differentially expressed genes relative to the control. In addition, all experimental treatments exhibited a greater number of downregulated genes than upregulated genes relative to −N + P transcriptomes. These findings complement those of previous studies, in which removal of NO3– or NH4+ in Dolichospermum cultures led to a greater number of significantly upregulated rather than downregulated genes associated with heterocyst production as well as stress responses to fixed N deprivation (Ehira and Ohmori, 2006; Flaherty et al., 2011; Mitschke et al., 2011). However, it is important to note that the −N-P treatment was the least different from the control relative to growth, Fv/Fm, N2 fixation, and ATX-A quota. Thus, it is likely that fixed N and P deprivation significantly influenced components of the Dolichospermum transcriptome beyond genes associated with growth, toxin production, and nitrogen assimilation.

Effects of nutrient availability on N and P assimilation

N form as well as P depletion led to significant differential expression of specific genes associated with N metabolism and N2 fixation relative to the control. The downregulation of amt1, which encodes for an ammonium transporter, and cphA, which encodes for cyanophycin synthetase, in NH4+ + P relative to the control, for instance, is consistent with previous findings, as cyanobacteria generally upregulate these genes only when fixed N is scarce (Montesinos et al., 1998; Muro-Pastor et al., 2005; Paz-Yepes et al., 2008). Nutrient availability also significantly affected the expression of genes associated with the glutamine synthetase-glutamate synthase (GS-GOGAT) pathway, a major metabolic process by which NH4+ is assimilated (Wolk et al., 1976). For example, glnB, which encodes for the regulatory protein PII (Forchhammer, 2004), was downregulated in the transcriptomes of NH4+ + P, which is consistent with previous findings (Tsinoremas et al., 1991; Paz-Yepes et al., 2009). PII activity is essential to the C:N balance in cyanobacteria and increases with increasing levels of 2-oxoglutarate, which is an indicator of the balance between CO2 fixation and NH4+ assimilation (Muro-Pastor et al., 2001; Forchhammer, 2004; Valladares et al., 2008). 2-oxoglutarate levels also regulate the activity of NtcA, a global transcriptional regulator for N assimilation pathways (Zhao et al., 2010; Picossi et al., 2014). The activity and levels of NtcA and 2-oxoglutarate, respectively, were not measured in this study. However, gltD, which encodes for glutamate synthase (Goss et al., 2001) was significantly downregulated in urea + P relative to the control. As glutamate is produced by glutamate synthase transferring nitrogen from glutamine to 2-oxoglutarate (Walker and van der Donk, 2016), it is highly likely that 2-oxoglutarate levels, as well as NtcA activity, are significantly affected when P-replete Dolichospermum sp. 54 are given urea as a fixed N source.

Downregulation of glnL, which encodes for nitrogen regulator II (NRII) (Ninfa and Magasanik, 1986), was observed in the transcriptomes of NO3– + P and −N-P. Downregulation of gltD, which encodes for part of the NADPH-GOGAT (Okuhara et al., 1999), was also observed in the transcriptomes of urea + P. The significant downregulation of glnL expression suggests that glutamine synthesis significantly decreased in these treatments (Reitzer and Magasanik, 1985; Ninfa and Magasanik, 1986), and reinforces the notion that a large portion of N derived from NO3–/NO2– reduction is not incorporated into organic compounds but rather utilized to promote PSII efficiency as oxidants (Flores et al., 2005). This is likely due to Dolichospermum requiring considerable amounts of energy to completely reduce NO3– (Ramos and Guerrero, 1983; Elder and Parker, 1984) and accounts for the significantly slower growth rates of NO3–-grown cells relative to NH4+-grown cells. Differential expression of genes within the GS-GOGAT pathway in different N treatments provides insight regarding how each fixed N compound affected N and C metabolism in Dolichospermum sp. 54.

Genes that encode for nitrate (narB) and nitrite (nirA) reductases (Cai and Wolk, 1997; Herrero and Flores, 2018) also exhibited significant upregulation and no significant difference in expression, respectively, in NO3– + P and −N-P cultures. This suggests that while NO3– was being reduced to NO2– (narB), NO2– reduction to NH4+ (nirA) was occurring at a relatively lower rate, which likely reflects NO3– + P cultures growing at a significantly slower rate than NH4+ + P cultures. Regardless, upregulation of narB likely reflects the significantly higher Fv/Fm and the significant enrichment of gene categories associated with the photosynthetic apparatus in NO3– + P cultures than that of the control, as NO3– reduction enhances cyanobacterial PSII efficiency as a Hill reagent (Serrano et al., 1981; Flores et al., 1983, 2005). While enhanced nitrate reductase activity in another Dolichospermum strain was reported to be essential in inhibiting nitrogenase activity (Martin−Níeto et al., 1991), that was not the case for NO3– + P cultures of Dolichospermum sp. 54, which exhibited significantly higher transcript abundance of narB and no significant change in N2 fixation relative to the control. This suggests that other factors, such as the full reduction of NO3– to NH4+, are necessary to inhibit nitrogenase activity in members of this genus to a degree comparable to Dolichospermum amended with NH4+ and urea.

Gene categories associated with PO43– transport were significantly upregulated in the transcriptomes of −N-P relative to the control, a response that is consistent with the effect of P-depletion on other Nostocales taxa (Teikari et al., 2015; Dong et al., 2019). The −N-P treatment, which exhibited significantly higher APA activity relative to the control, was the only treatment to exhibit significant upregulation of several phn genes and pstC. The phn gene cluster encodes for proteins involved in the transport and metabolism of phosphonates under P-deplete conditions and/or components of the carbon-phosphorus lyase, while pstC encodes for a high affinity PO43– transporter (Adams et al., 2008; Voß et al., 2013). Collectively, differentially expressed genes associated with P transport and assimilation are consistent with prior studies of gene markers of P-limitation in cyanobacteria (Harke et al., 2012; Harke and Gobler, 2013; Lu et al., 2019) and suggests they are important in supporting Dolichospermum blooms when dissolved inorganic phosphorus is scarce.

Conclusion

In summary, fixed N-replete Dolichospermum sp. 54 cultures exhibited significantly enhanced growth (NH4+, urea, NO3–) and photosynthetic efficiency (NH4+ and NO3–) relative to those grown under fixed N-limiting conditions. NH4+-grown cultures also exhibited significantly higher and lower growth and N2 fixation rates, respectively, relative to NO3–-grown cultures. Cultures also exhibited significant differences in growth, Fv/Fm, N2 fixation, ATX-A production, and genome expression depending on whether they were amended with NH4+, urea, NO3–, or deprived of both fixed N and P, reinforcing the notion that Dolichospermum and likely other toxin-producing Nostocales taxa exhibit highly specific preferences for different fixed N species. These findings also support the growing consensus that diazotrophic cyanobacteria exhibit fixed N-limitation similar to non-diazotrophic CHAB taxa such as Microcystis with respect to growth rate, as well as P-limitation, and prefer certain fixed N species under P-replete conditions. From a managerial perspective, if fixed N inputs are not controlled in eutrophic systems where Dolichospermum spp. occur, blooms of these and other Nostocales taxa may be of greater biomass and subsequently have higher toxin concentrations.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material.

Author contributions

BK and JJ performed the culture experiment and analyzed growth rate, ATX-A, N2 fixation, nutrient, and Fv/Fm data. BK graphed the data and drafted the manuscript. JJ extracted RNA. MH and DN processed transcriptomic data post-sequencing. CG provided the funding and technical resources necessary to perform experiments and performed the analyses. All authors contributed to data analysis and study design.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jennifer Goleski for processing nutrient samples, Mathias Chia for setting up and maintaining cultures during the experiment, and Megan Ladds for her assistance in extracting RNA. We also thank the staff of Columbia University’s Next Generation Sequencing facility for sequencing RNA samples, as well as those of Stony Brook University’s Center for Clean Water Technology for processing anatoxin-a samples.

Footnotes

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Chicago Community Fund (2022-01) and the National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science (NCCOS) Monitoring and Event Response for Harmful Algal Blooms (MERHAB) Research Program (Grant number: 236).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2022.955032/full#supplementary-material

Cell densities for all treatments during the experiment, from day 1 to the final time point (day 9). Error bars represent standard deviation.

Photosystem II photosynthetic efficiency (Fv/Fm) for all treatments during the experiment. Error bars represent standard deviation. Red arrows represent days when fixed N species (NH4Cl, Urea, and NaNO3) were added to fixed N-replete treatments.

Alkaline phosphatase activity (nmol mL–1 hr–1) as a function of volume and time in treatments deprived on nitrogen and either with or without phosphorus on days 1, 3, 5, and 9. Error bars represent standard error. Number of asterisks correspond to degree of significance (p < 0.05 = *, 0.01 = **, 0.001 = ***), determined via Student’s paired t-test.

References

- Adams M., Gomez-Garcia M., Grossman A., Bhaya D. (2008). Phosphorus deprivation responses and phosphonate utilization in a thermophilic synechococcus sp. from microbial mats. J. Bacteriol. 190 8171–8184. 10.1128/JB.01011-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama M., Crooke E., Kornberg A. (1993). An exopolyphosphatase of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 268 633–639. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)54198-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammar M., Comte K., Tran T., El Bour M. (2014). Initial growth phases of two bloom-forming cyanobacteria (Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii and Planktothrix agardhii) in monocultures and mixed cultures depending on light and nutrient conditions. Ann. Limnol. Int. J. Lim. 50 231–240. 10.1051/LIMN/2014096 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson B., Voorhees J., Phillips B., Fadness R., Stancheva R., Nichols J., et al. (2018). Extracts from benthic anatoxin-producing Phormidium Are Toxic to 3 macroinvertebrate taxa at environmentally relevant concentrations. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 37 2851–2859. 10.1002/etc.4243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A., et al. (2013). SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 19 455–477. 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beversdorf L., Miller T., McMahon K. (2013). The role of nitrogen fixation in cyanobacterial bloom toxicity in a temperate, eutrophic lake. PLoS One 8:e56103. 10.1371/journal.pone.0056103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomqvist S., Gunnars A., Elmgren R. (2004). Why the limiting nutrient differs between temperate coastal seas and freshwater lakes: A matter of salt. Limnol. Oceanogr. 49 2236–2241. 10.4319/lo.2004.49.6.2236 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger A., Lohse M., Usadel B. (2014). Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30 2114–2120. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bone D. (1971). Nitrogenase activity and nitrogen assimilation in anabaena flos-aquae growing in continuous culture. Arch. Microbiol. 80 234–241. 10.1007/BF00410124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray N., Pimentel H., Melsted P., Pachter L. (2016). Near-optimal probablistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 34 525–527. 10.1038/nbt.3519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckland P., Codd G., Hall T., Izydorczyk K., Kull T., Lindholm T., et al. (2005). Toxic: Cyanobacterial monitoring and cyanotoxin analysis. Åbo: Åbo Akademi University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burut-Archanai S., Powtongsook S. (2017). Identification of negative regulator for phosphate-sensing system in Anabaena sp. PCC 7120: A target gene for developing phosphorus removal. Biochem. Eng. J. 125 129–134. 10.1016/j.bej.2017.05.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bushmanova E., Antipov D., Lapidus A., Prjibelski A. (2019). rnaSPAdes: A de novo transcriptome assembler and its application to RNA-Seq data. GigaScience 8:giz100. 10.1093/gigascience/giz100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y., Wolk C. (1997). Nitrogen deprivation of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 elicits rapid activation of a gene cluster that is essential for uptake and utilization of nitrate. J. Bacteriol. 179 258–266. 10.1128/jb.179.1.258-266.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capone D. (1993). “Determination of nitrogenase activity in aquatic samples using the acetylene reduction procedure,” in Handbook in methods in aquatic microbial ecology, eds Kemp P., Cole J., Sherr B., Sherr E. (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; ), 621–631. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael W. (1994). The toxins of cyanobacteria. Sci. Am. 270 64–70. 10.1038/scientificamerican0194-78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael W., Briggs D., Peterson M. (1979). Pharmacology of anatoxin-a, produced by the freshwater cyanophyte Anabaena flos-aquae NRC-44-1. Toxicon 17 229–236. 10.1016/0041-0101(79)90212-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin J., Mishra S., Kane D., Bade D., Stanislawczyk K., Slodysko K., et al. (2019). Cyanobacterial blooms in the central basin of lake Erie: Potentials for cyanotoxins and environmental drivers. J. Great Lakes Res. 45 277–289. 10.1016/j.jglr.2018.12.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin J., Stanislawczyk K., Kane D., Lambrix M. (2020). Nutrient addition effects on chlorophyll a, phytoplankton biomass, and heterocyte formation in Lake Erie’s central basin during 2014–2017: Insights into diazotrophic blooms in high nitrogen water. Freshw. Biol. 65 2154–2168. 10.1111/fwb.13610 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chia M., Jankowiak J., Kramer B., Goleski J., Huang I., Zimba P., et al. (2018). Succession and toxicity of Microcystis and Anabaena (Dolichospermum) blooms are controlled by nutrient-dependent allelopathic interactions. Harmful Algae 74 67–77. 10.1016/j.hal.2018.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia M., Kramer B., Jankowiak J., Bittencourt-Oliveira M., Gobler C. (2019). The individual and combined effects of the cyanotoxins, anatoxin-A and microcystin-LR, on the growth, toxin production, and nitrogen fixation of prokaryotic and eukaryotic algae. Toxins 11:43. 10.3390/toxins11010043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen V., Kahn E. (2020). Freshwater neurotoxins and concerns for human, animal, and ecosystem health: A review of anatoxin-a and saxitoxin. Sci. Total Environ. 736:139515. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll D. (1999). Phosphorus: A rate limiting nutrient in surface waters. Poult. Sci. 78 674–682. 10.1093/ps/78.5.674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curatti L., Hernandez J., Igarashi R., Soboh B., Zhao D., Rubio L. (2007). In vitro synthesis of the iron molybdenum cofactor of nitrogenase from iron, sulfur, molybdenum, and homocitrate using purified proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 17626–17631. 10.1073/pnas.0703050104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai G., Deblois C., Liu S., Juneau P., Qiu B. (2008). Differential sensitivity of five cyanobacterial strains to ammonium toxicity and its inhibitory mechanism on the photosynthesis of rice-field cyanobacterium Ge-Xian-Mi (Nostoc). Aquat. Toxicol. 89, 113–121. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2008.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Aversano C., Hess P., Quilliam M. (2005). Hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry for the analysis of paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP) toxins. J. Chromatogr. A. 1081 190–201. 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.05.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster E., Pryor K., Francis D., Young J., Rogers H. (1999). Rapid DNA extraction from ferns for PCR-based analyses. Biotechniques 27 66–68. 10.2144/99271bm13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin J., Edwards O., Gorham P., Hunter N., Pike R., Stavric B. (1977). Anatoxin-a, a toxic alkaloid from Anabaena flos-aquae NRC-44h. Can. J. Chem. 55 1367–1371. 10.1139/v77-189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dolman A. M., Rucker J., Pick F. R., Fastner J., Rohrlack T., Mischke U., et al. (2012). Cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins: The influence of nitrogen versus phosphorus. PLoS One 7:e38757. 10.1371/journal.pone.0038757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong C., Zhang H., Yang Y., He X., Liu L., Fu J., et al. (2019). Physiological and transcriptomic analyses to determine the responses to phosphorus utilization in Nostoc sp. Harmful Algae 84 10–18. 10.1016/j.hal.2019.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos P., Fang Z., Mason S., Setubal J., Dixon R. (2012). Distribution of nitrogen fixation and nitrogenase-like sequences amongst microbial genomes. BMC Genom. 13:162. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyhrman S., Ammerman J., Van Mooy B. (2007). Microbes and the Marine Phosphorus Cycle. Oceanography 20 110–116. 10.5670/oceanog.2007.54 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehira S., Ohmori M. (2006). NrrA, a nitrogen-responsive response regulator facilitates heterocyst development in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. Mol. Microbiol. 59 1692–1703. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05049.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehira S., Ohmori M., Sato N. (2003). Genome-wide expression analysis of the responses to nitrogen deprivation in the heterocyst-forming cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. DNA Res. 10 97–113. 10.1093/dnares/10.3.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder R., Parker M. (1984). Growth Response of a Nitrogen Fixer (Anabaena flos-aquae, Cyanophygeae) to Low Nitrate. J. Phycol. 20 296–301. 10.1111/j.0022-3646.1984.00296.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Shehawy R., Kleiner D. (2003). The mystique of irreversibility in cyanobacterial heterocyst formation:parallels to differentiation and senescence in eukaryotic cells. Physiol. Plant 119 49–55. 10.1128/9781555818166.CH3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erratt K., Creed I., Trick C. (2018). Comparative effects of ammonium, nitrate and urea on growth and photosynthetic efficiency of three bloom-forming cyanobacteria. Freshw. Biol. 63 626–638. 10.1111/fwb.13099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Falcon S., Gentleman R. (2007). Using GOstats to test gene lists for GO term association. Bioinformatics 23 257–258. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty B., Nieuwerburgh F., Head S., Golden J. (2011). Directional RNA deep sequencing sheds new light on the transcriptional response of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 to combined−Nitrogen deprivation. BMC Genom. 12:332. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores E., Frias J., Rubio L., Herrero A. (2005). Photosynthetic nitrate assimilation in cyanobacteria. Photosynth. Res. 83 117–133. 10.1007/s11120-004-5830-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores E., Guerrero M., Losada M. (1983). Photosynthetic nature of nitrate uptake and reduction in the cyanobacterium Anacystis nidulans. BBA 722 408–416. 10.1016/0005-2728(83)90056-7 19007922 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fogg G. (1942). Studies on nitrogen fixation by blue-green Algae I. nitrogen fixation by anabaena cylindrica LEMM. J. Exp. Biol. 19 78–87. 10.1242/jeb.19.1.78 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forchhammer K. (2004). Global carbon/nitrogen control by PII signal transductionin cyanobacteria: From signals to targets. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 28 319–333. 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon A., Pick F. (2012). Effect of nitrogen on cellular production and release of the neurotoxin anatoxin-a in a nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium. Front. Microbiol. 3:211. 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamez T., Benton L., Manning S. (2019). Observations of two reservoirs during a drought in central Texas, USA: Strategies for detecting harmful algal blooms. Ecol. Indic. 104 588–593. 10.1016/j.ecolind.2019.05.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X., Cain K., Hirschberg R. (1990). Urea metabolism and urease regulation in the cyanobacterium Anabaena variabilis. Can. J. Microbiol. 36 218–222. 10.1139/m90-037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber B., Wickstrom C. (1990). Response of Anabaena flos-aquae (Cyanophyta) nitrogenase activity to sudden phosphate deprivation. J. Phycol. 26 650–655. 10.1111/j.0022-3646.1990.00650.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glibert P., Maranger R., Sobota D., Bouwan L. (2014). The haber bosch-harmful algal bloom (HB-HAB) link. Environ. Res. Lett. 9:105001. 10.1088/1748-9326/9/10/105001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gobler C. J., Burkholder J. M., Davis T. W., Harke M. J., Johengen T., Stow C. A., et al. (2016). The dual role of nitrogen supply in controlling the growth and toxicity of cyanobacterial blooms. Harmful Algae 54 87–97. 10.1016/j.hal.2016.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goss T., Perez-Matos A., Bender R. (2001). Roles of Glutamate Synthase, gltBD, and gltF in Nitrogen Metabolism of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella aerogenes. J. Bacteriol. 183 6607–6619. 10.1128/JB.183.22.6607-6619.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr M., Haas B., Yassour M., Levin J., Thompson D., Amit I., et al. (2011). Trinity: Reconstructing a full-length transcriptome without a genome from RNA-Seq data. Nat. Biotechnol. 29 644–652. 10.1038/nbt.1883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillard R. (1973). “Division Rates,” in Handbook of phycological methods, ed. Stein J. (Cambridge: Cambridge Universty Press; ), 289–312. [Google Scholar]

- Haas B., Papanicolaou A., Yassour M., Grabherr M., Blood P., Bowden J., et al. (2013). De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 8 1494–1512. 10.1038/nprot.2013.084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy R., Burns R., Holsten R. (1973). Applications of the acetylene-ethylene assay for measurement of nitrogen-fixation. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 5 47–81. 10.1104/pp.43.8.1185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harke M., Berry D., Ammerman J., Gobler C. (2012). Molecular response of the bloom-forming cyanobacterium, Microcystis aeruginosa, to phosphorus limitation. Microb. Ecol. 63 188–198. 10.1007/s00248-011-9894-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]