Abstract

The NAD+-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase (NAD-GDH) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 was purified, and its amino-terminal amino acid sequence was determined. This sequence information was used in identifying and cloning the encoding gdhB gene and its flanking regions. The molecular mass predicted from the derived sequence for the encoded NAD-GDH was 182.6 kDa, in close agreement with that determined from sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of the purified enzyme (180 kDa). Cross-linking studies established that the native NAD-GDH is a tetramer of equal subunits. Comparison of the derived amino acid sequence of NAD-GDH from P. aeruginosa with the GenBank database showed the highest homology with hypothetical polypeptides from Pseudomonas putida, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Rickettsia prowazakii, Legionella pneumophila, Vibrio cholerae, Shewanella putrefaciens, Sinorhizobium meliloti, and Caulobacter crescentus. A moderate degree of homology, primarily in the central domain, was observed with the smaller tetrameric NAD-GDH (protomeric mass of 110 kDa) from Saccharomyces cerevisiae or Neurospora crassa. Comparison with the yet smaller hexameric GDH (protomeric mass of 48 to 55 kDa) of other prokaryotes yielded a low degree of homology that was limited to residues important for binding of substrates and for catalytic function. NAD-GDH was induced 27-fold by exogenous arginine and only 3-fold by exogenous glutamate. Primer extension experiments established that transcription of gdhB is initiated from an arginine-inducible promoter and that this induction is dependent on the arginine regulatory protein, ArgR, a member of the AraC/XyIS family of regulatory proteins. NAD-GDH was purified to homogeneity from a recombinant strain of P. aeruginosa and characterized. The glutamate saturation curve was sigmoid, indicating positive cooperativity in the binding of glutamate. NAD-GDH activity was subject to allosteric control by arginine and citrate, which function as positive and negative effectors, respectively. Both effectors act by influencing the affinity of the enzyme for glutamate. NAD-GDH from this organism differs from previously characterized enzymes with respect to structure, protomer mass, and allosteric properties indicate that this enzyme represents a novel class of microbial glutamate dehydrogenases.

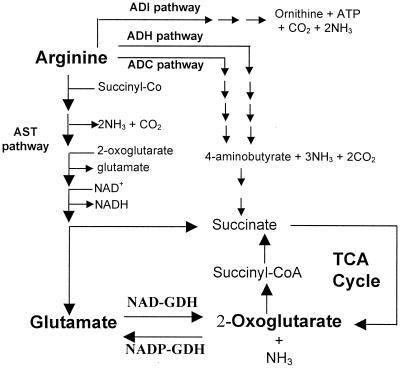

Arginine is an important nutrient for Pseudomonas aeruginosa, as reflected in its ability to serve as one of the strongest chemotactic attractants to this organism (9). The arginine succinyltransferase (AST) pathway, which converts l-arginine into glutamate (Fig. 1), is the major route for arginine catabolism in P. aeruginosa under aerobic conditions (17, 22, 23). Previous studies (31, 34, 36–38) have established that the ArgR protein, a member of the AraC/XyIS family of regulatory proteins (13), activates transcription of the aru operon, encoding enzymes of the AST pathway, as well as other operons for arginine uptake and catabolism (aot-argR, oprD, and arcDABC). ArgR of this organism also represses certain operons of arginine biosynthesis (argF and carAB).

FIG. 1.

Arginine catabolic pathways in P. aeruginosa PAO1. Only key intermediates and enzymes related to this report are shown. NADP-GDH, anabolic NADP-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase; NAD-GDH, catabolic NAD-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase; AST, arginine succinyltransferase; ADC, arginine decarboxylase; ADH, arginine dehydrogenase; ADI, arginine deiminase.

P. aeruginosa, like most pseudomonads, possesses an NADP+-linked glutamate dehydrogenase for reductive biosynthesis as well as an NAD+-linked glutamate dehydrogenase (NAD-GDH) for oxidative degradation (7, 11, 24). Previous studies from this laboratory have shown that the NAD-GDH of P. aeruginosa is induced by arginine and that this induction requires a functional ArgR (37). This finding led to the proposal (37) that NAD-GDH functions in arginine catabolism by converting l-glutamate, the product of the AST pathway, into 2-oxoglutarate, which is then channeled into the tricarboxylic acid cycle (Fig. 1).

This paper reports the use of reverse genetics for cloning the gdhB gene from P. aeruginosa and purification of the encoded NAD-GDH. Unlike the previously characterized glutamate dehydrogenases from bacteria, which are hexamers with protomer molecular masses of 48 to 55 kDa (2), the NAD-GDH from P. aeruginosa is a tetramer with a protomer molecular mass of 180 kDa. The derived sequence for NAD-GDH exhibits a low degree of homology with previously characterized glutamate dehydrogenases from microorganisms. The purified P. aeruginosa enzyme is subject to allosteric activation and inhibition by arginine and citrate. The combined results identify NAD-GDH of P. aeruginosa as a representative of a new class of glutamate dehydrogenases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, media, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Luria-Bertani (LB) enriched medium (32) was used for strain construction with the following supplements as required: ampicillin, 50 μg/ml (E. coli); carbenicillin, 100 μg/ml (P. aeruginosa); gentamicin, 100 μg/ml; streptomycin, 500 μg/ml. Minimal medium P described by Haas et. al. (18) was used for the growth of P. aeruginosa with supplements of sources of carbon and nitrogen at 20 mM.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | F− Φ80dlacΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK−) supE44 λ−thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | Bethesda Research Laboratories |

| SM10 | Host strain for gene replacement | 14 |

| P. aeruginosa | ||

| PAO1 | Wild type | 18 |

| PAO501 | argR mutant of PAO1 | 37 |

| PAO1-sm | Spontaneous streptomycin-resistant mutant of PAO1 | 37 |

| PAO601 | gdhB::Gm mutant of PAO1-sm | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pQF52 | bla lacZ translational fusion vector | 38 |

| pRTP1 | bla Strs conjugation vector | 41 |

| pGMΩ1 | bla gen; gentamicin cassette with omega loop on both ends | 39 |

| pCOS-A84 | Cosmid clone of gdhB in the SuperCOS-1 vector (Strategene) | This study |

| pNAD100 | 530-bp PCR fragment of the gdhB promoter region cloned into HindIII/SmaI site of pQF52 | This study |

| pNAD500 | gdhB clone derived from pNAD100 and pCOS-A84 | This study |

| pNAD500-Gm | Insertion of a gentamicin resistance cassette in the gdhB gene in pRTP1 for gene replacement | This study |

Enzyme assays.

Logarithmically growing cultures were harvested at a turbidity of 0.5 at 600 nm. The cells were washed once with water and suspended in 20 mM HEPES (pH 8.5) containing 100 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA. Cells were ruptured by passage through an Aminco French pressure cell, and the cell extract was centrifuged at 27,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The deamination activity of NAD-GDH was determined at 37°C by monitoring the absorbance at 340 nm in a Cary 3E recording spectrophotometer. The reaction mixture (2 ml) contained 100 mM HEPES (pH 8.5), 2.5 mM NAD+, and 50 mM l-glutamate unless otherwise indicated. The amination activity of NAD-GDH was measured by monitoring the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm in reaction mixtures (2 ml) containing 100 mM HEPES (pH 8.5), 20 mM 2-oxoglutarate, 1 mM NADH, and 50 mM ammonium chloride. In either case, the reaction was initiated by the addition of enzyme. One enzyme unit catalyzes the oxidation or reduction of 1 nmol of coenzyme per min. The protein concentration was determined by the method of Bradford (5) with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Purification of NAD-GDH.

P. aeruginosa PAO1 containing pNAD500 was grown in LB medium supplemented with 20 mM l-arginine. Cells were collected by centrifugation, washed with water, and suspended at 0.5 g (wet weight) per ml in 20 mM HEPES (pH 8.0) containing 1 mM EDTA and 100 mM NaCl. All solutions coming in contact with the enzyme contained 1 mM EDTA and 100 mM NaCl, which were found to be essential for stability of the enzyme. Purification in the absence of EDTA and NaCl resulted in desensitization of the purified NAD-GDH to allosteric effectors. Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride was added to a final concentration of 1 mM, and the cells were ruptured by passage through an Aminco French pressure cell at 8000 lb/in2. The crude extract was centrifuged at 48,000 × g for 30 min. Streptomycin sulfate (1 ml of 20% solution per 10 ml of centrifuged extract) was added with stirring and equilibrated for 10 min. NAD-GDH coprecipitated with the nucleic acids, and the purification procedure took advantage of this fortuitous finding. NAD-GDH was readily eluted by 20 mM HEPES (pH 8.5) containing 100 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA. The suspension was centrifuged at 48,000 × g for 10 min to remove the nucleic acids. The supernatant was subjected to ammonium sulfate fractionation. The fraction precipitating between 30 and 60% saturation was dissolved in 50 ml of 20 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), and the solution filtered through a Millipore membrane (0.45-μm pore size) and applied to a Pharmacia HiLoad Q Sepharose column (HR 16/10) equilibrated with the same buffer. After injection of the sample, the column was washed with 50 ml of the starting buffer and protein was eluted with a linear gradient of NaCl in 20 mM HEPES (pH 8.0). NAD-GDH was eluted between 0.35 and 0.45 M NaCl. Fractions containing NAD-GDH were combined, precipitated with ammonium sulfate (70% saturation), and centrifuged at 48,000 × g for 20 min. The precipitate was dissolved in 0.5 ml of 50 mM HEPES (pH 8.0) containing 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA, and the solution was subjected to gel filtration using a Pharmacia Superdex 200 column (HR 10/30) equilibrated with the same buffer. NAD-GDH was eluted at 9 ml. This elution volume indicates that NAD-GDH self-associates into an aggregate with a molecular mass close to 2000 kDa.

Determination of amino-terminal amino acid sequence.

Purified NAD-GDH was applied directly on a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and the amino-terminal amino acid sequence was determined by Edman degradation using an Applied Biosystems Procise 492 Sequencer at the Molecular Genetics Core Facility of Georgia State University.

Cross-linkage of subunits.

The native protein was cross-linked with 0.005% glutaraldehyde in 50 mM HEPES (pH 8.0) containing 150 mM NaCl. The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 2 h and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) using a 5% gel. The protein samples were mixed with an equal volume of loading buffer containing 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 0.4% SDS, 20% glycerol, and 0.001% bromophenol blue and subjected to boiling in a water bath for 5 min. All samples contained 1% β-mercaptoethanol unless otherwise indicated.

Southern analysis and colony hybridization.

The DNA probes were labeled with digoxigenin-11-dUTP by the random-primed method, and the hybrids were detected by an enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay with an anti-digoxigenin-alkaline phosphatase conjugate and subsequent color reaction as described by the manufacturer (Genius System; Boerhinger Mannheim). The labeled DNA probe was hybridized to a Southern blot of EcoRI-digested genomic DNA on a nylon membrane.

For the identification of gdhB clones in a cosmid genomic library of P. aeruginosa PAO1 (27), a 500-bp DNA fragment covering the gdhB regulatory region (Fig. 2) was amplified from the chromosomal DNA of PAO1 by PCR with a pair of oligonucleotide primers: 5′-CGCAAGCTTCGAGGTCGCCACCTGGATGCTGGC-3′ and 5′-GCTGGCCGCGGTGAAGAACGCCATGG-3′. This DNA fragment was labeled and used to screen the library following the protocol described by the manufacturer (Boerhinger Mannheim) for colony hybridization and hybrid detection.

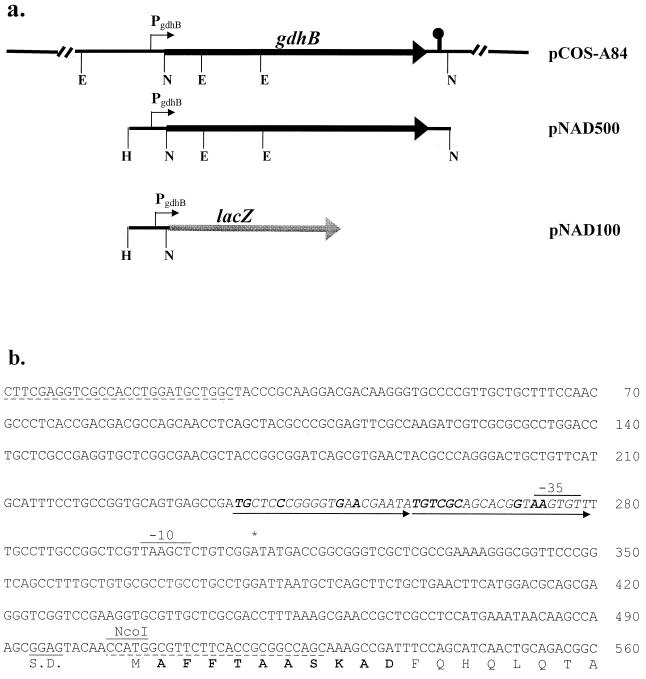

FIG. 2.

(a) Schematic drawing of the genetic organization of the gdhB operon in the recombinant plasmids used. pCOS-A84 and pNAD500 carry the entire functional gdhB operon. A sequence structure resembling a rho-independent terminator at the end of the gdhB operon is also marked. (b) Nucleotide sequence of the gdhB regulatory region. The transcriptional initiation site is indicated by an asterisk above the nucleotide, and the −10 and −35 regions of the promoter are indicated accordingly. Also shown is the Shine-Dalgarno (S.D.) sequence for the gdhB gene. The sequences of two oligonucleotide primers used for probe generation by PCR and for construction of pNAD100 are underlined with dashes, and the location of an NcoI restriction site is also marked. The putative ArgR operator site is indicated with tandem repeat arrows, and nucleotide bases identical to the consensus sequence, 5′-TGTCGCN6GNAAN5-3′, are italicized and shown in boldface. The amino acid residues, determined by Edman degradation of purified NAD-GDH, are shown in boldface.

Expression of NAD-GDH in P. aeruginosa.

A recombinant plasmid, containing the structural gene of gdhB and the flanking upstream regulatory region, was constructed by the following approach. First, the DNA fragment carrying nucleotides (nt) 1 to 528 (Fig. 2b) was cloned into the HindIII/SmaI sites of plasmid pQF52, a broad-host-range lacZ translational fusion vector (34). The resulting plasmid was designated pNAD100. Second, a 4,952-bp NcoI fragment, extending from nt 503 overlapping the ATG initiation codon of gdhB to nt 5454 downstream of the 3′-flanking region of gdhB (Fig. 2a), was subcloned into the NcoI site of pNAD100. The second step thus replaced the lacZ gene in this plasmid with the gdhB gene. The resulting recombinant plasmid was designated pNAD500. Plasmid pNAD500 and its parent vector, pQF52, were then used to transform P. aeruginosa PAO1. The transformants, carrying pNAD500 and grown in LB supplemented with 20 mM arginine, had 28-fold-higher NAD-GDH activity than the control strain carrying pQF52.

Primer extension experiments.

RNA extraction and primer extension were carried out as previously described (38). A 24-bp oligonucleotide primer, with a sequence complementary to nt 503 to 528 of Fig. 2b, was end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and used for hybridization with 50 μg of total RNA. The extended products were separated on a 6% denatured sequencing gel, and the 5′ ends of these transcripts were determined by comparison to a sequencing ladder of pNAD500 generated by using the same primer. Experiments were carried out quantitatively to permit comparison of levels of transcription under different growth conditions.

Gene replacement.

A 1.6-kb EcoRI fragment containing the gentamicin resistance (Gm) cassette was isolated from plasmid pGM1 (39) after restriction enzyme digestion and separation by agarose gel electrophoresis. The Gm cassette was used to replace a 1.0-kb EcoRI fragment of the gdhB gene in pNAD500R, which has the gdhB gene in a conjugation vector, pRTP1 (41). The resulting gene replacement plasmid, pNAD500-Gm, in Escherichia coli SM10 was mobilized into a spontaneous streptomycin-resistant strain of P. aeruginosa, PAO1-Sm, by biparental plate mating as described by Gambello and Iglewski (14). Following incubation at 37°C for 16 h, transconjugants were selected on LB plates containing gentamicin and streptomycin.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of gdhB and its flanking regions has been deposited in the GenBank database under accession number AF315586.

RESULTS

Cloning of gdhB using reverse genetics.

NAD-GDH was purified from P. aeruginosa PAO1. The final product was judged homogeneous as indicated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The molecular mass of the protomer was estimated to be 180 kDa from a plot of electrophoretic mobility in SDS-PAGE gels against the logarithm of the molecular masses of known polypeptides (data not shown).

The first 10 amino acid residues for the purified NAD-GDH were determined as A-F-F-T-A-A-S-K-A-D. This determined sequence was then used for a BLAST search against the finished genomic sequence of P. aeruginosa (www.pseudomonas.com). The search yielded only one candidate with a perfect match to the determined amino-terminal sequence. The possible open reading frames (ORFs) in the putative locus for NAD-GDH were subjected to codon bias analysis. The results of sequence analysis indicated the presence of an ORF of 1,620 amino acids starting from a methionine residue followed by the determined N-terminal sequence of NAD-GDH. The molecular mass predicted from the derived sequence was 182.6 kDa, which is in close agreement with that determined (180 KDa) for the protomer of purified NAD-GDH by SDS-PAGE.

To clone the identified gdhB gene, a DNA fragment containing the upstream region flanking gdhB was first amplified from the chromosomal DNA of PAO1 by PCR to yield a DNA product containing a HindIII site followed by the sequence from nt 1 to nt 528 of Fig. 2b. The purified PCR product was labeled with digoxigenin-UTP and used for gene screening of a genomic cosmid library of P. aeruginosa. Several cosmid clones were identified by colony hybridization. The presence of the 5′ terminus for gdhB and the upstream flanking region in these clones was confirmed by nucleotide sequencing. In order to construct a subclone of the gdhB gene, a HindIII/NcoI fragment containing the gdhB regulatory region (nt 1 to 508, Fig 2b) was first obtained by restriction enzyme digestion of the probe DNA fragment described. A 4,592-bp NcoI fragment containing the entire gdhB coding region was then purified from one of the gdhB cosmid clones, pCOS-A84. These two DNA fragments were ligated into the HindIII/NcoI sites of the pQF52 vector plasmid, and the resulting gdhB subclone was designated pNAD500.

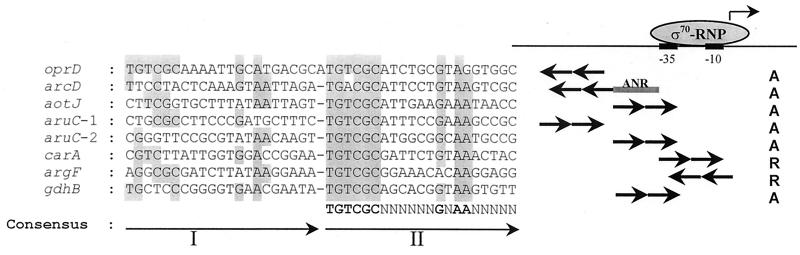

The sequence for the 5′ terminus for gdhB and the upstream flanking region, retrieved from the Pseudomonas Genome Project and confirmed here for pNAD500, is shown in Fig. 2. The derived sequence for NAD-GDH extends from an ATG initiation triplet at position 505 and is preceded by a putative ribosomal binding site (GGAG). Analysis of the nucleotide sequence upstream of gdhB identified a sequence similar to the consensus ArgR binding site, which is centered at 51.5 bp upstream from the transcriptional initiation site. Consistent with the results obtained with previously characterized ArgR operators (31), this putative ArgR operator for gdhB is also composed of a degenerated first-half site and a more conserved second-half site. The sequence of the second-half site is identical to the consensus sequence of ArgR operators, 5′-TGTCGCN6GNAAN5-3′ (31).

Although not shown here, the complete sequence for gdhB that was retrieved from the Pseudomonas Genome Project encodes a polypeptide of 1,620 amino acid residues. A sequence resembling a rho-independent transcriptional terminator was identified 22 bp downstream of the translational stop codon for gdhB. The sequence annotations by the Pseudomonas Genome Project indicates the presence of an ORF, with a coding capacity of 257 amino acids, which terminates 274 bp upstream of the gdhB initiation codon. While the annotation indicates that this ORF is transcribed in the same direction as gdhB, codon bias analysis suggests that an ORF, with a coding capacity of 254 amino acids and an initiation codon at 291 bp upstream of gdhB, can be transcribed in the opposite direction. The sequence annotation also indicates a second ORF with an initiation codon at 149 bp downstream of the gdhB stop codon. The presence of a transcriptional terminator-like sequence downstream of the gdhB structural gene and an arginine-inducible promoter, as will be described in the next section, indicates that NAD-GDH is translated from a single gene transcript.

Mapping of transcriptional initiation.

Primer extension experiments were carried out for determination of the location of the arginine-responsive promoter. The results (data not shown) show that transcription is initiated at an adenine residue located 195 bp upstream from the ATG initiation codon. A sequence similar to the −10 region of the consensus ς70 promoter of E. coli was found in the appropriate position upstream of the identified transcriptional start site, but no sequence resembling a −35 sequence was evident. Exogenous arginine induces the level of the gdhB transcript in PAO1. No detectable level of this transcript was observed in the argR derivative, PAO501, indicating a much lower level of promoter activity in the absence of a functional ArgR.

Regulation of gdhB expression.

NAD-GDH levels were determined for P. aeruginosa PAO1 grown in minimal medium supplemented with a variety of compounds as sources of carbon and nitrogen. The results (Table 2) showed that NAD-GDH was induced 27-fold when PAO1 was grown with arginine as the sole source of carbon and nitrogen relative to the level found when grown with succinate and ammonia as carbon and nitrogen sources, respectively. NAD-GDH was induced to a much lesser extent by ornithine, glutamate, and aspartate (5-, 3-, and 1.7-fold, respectively). The induction by arginine was completely abolished in the argR derivative, PAO501.

TABLE 2.

Arginine- and ArgR-dependent induction of the gdhB operon

| Strain (genotype) | Supplementa | Sp act (nmol/min/mg)b |

|---|---|---|

| PAO1 (wild type) | S + N | 18 (2) |

| Glu | 60 (3) | |

| Asp | 31 (1) | |

| Orn | 94 (2) | |

| Arg | 487 (28) | |

| PAO501 (argR) | Glu | 38 (2) |

| Glu + Arg | 28 (1) |

Cells were grown in minimal medium with 20 mM supplements as indicated: S, sodium succinate; N, ammonium sulfate; Glu, l-glutamate; Asp, l-aspartate; Orn, ornithine; Arg, l-arginine.

The specific activities are the averages of two measurements for each growth condition, with the standard errors shown in parentheses.

Construction and phenotype of a gdhB null mutant.

In order to investigate the physiological function of NAD-GDH in P. aeruginosa, a gdhB null mutant (PAO601) was constructed by allele replacement of a 1.0-kb EcoRI fragment of gdhB with an gentamicin antibiotic resistance cassette. The insertion of a gentamicin resistance cassette in the expected location of the PAO601 chromosome was confirmed by Southern blot analysis (data not shown). No NAD-GDH activity was detectable in a culture of PAO601 grown in minimal medium supplemented with arginine. The phenotype of the null mutant was investigated with respect to its ability to utilize various carbon and nitrogen sources. The null mutant grew well on minimal medium plates supplemented with glutamate, glutamine, aspartate, aspargine, proline, or histidine as the sole source of carbon and nitrogen. In contrast, when arginine served as the sole source of carbon and nitrogen, formation of visible colonies required 2 to 3 days for the null mutant relative to 1 day for the parent strain. In liquid minimal medium supplemented with arginine as the sole source of carbon and nitrogen, the doubling time for the gdhB mutant (100 min) was consistently longer than of the parent strain (75 min). In addition, a much longer lag time (13 h, in comparison to 7 h for the parent strain) was observed upon transfer of cells from minimal medium supplemented with succinate and ammonia. Experiments with glutamate as the sole source of carbon and nitrogen yielded the same doubling time (76 min).

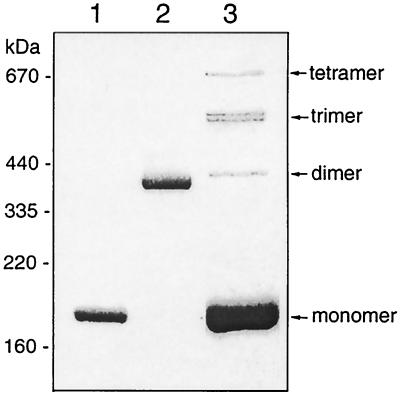

Subunit structure.

For structural and kinetic characterization, NAD-GDH was purified to homogeneity from a recombinant strain of P. aeruginosa PAO1 carrying pNAD500 and grown in LB medium supplemented with 20 mM arginine. The homogeneous NAD-GDH was subjected to SDS-PAGE. A value of 180 kDa for the molecular mass of the protomer was determined from a plot of electrophoretic mobility against the logarithm of the molecular masses of known polypeptides (Fig. 3). This value is identical to that obtained with the chromosomally encoded NAD-GDH as described above. In addition, without the β-mercaptoethanol treatment, the dimeric form was found to be the major species of NAD-GDH by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3, lane 2). This result indicates the presence of disulfide bonds in the native NAD-GDH. In order to determine the number of subunits in the native NAD-GDH, the homogeneous protein was cross-linked with the bifunctional reagent glutaraldehyde prior to electrophoresis on a 5% polyacrylamide gel in the presence of SDS. The results (Fig. 3, lane 3) show bands corresponding to all possible species ranging from monomer to tetramer. At the trimer level, two bands are evident, likely reflecting two different conformations of cross-linked trimeric species.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of subunit structure of NAD-GDH. Protein samples were run on a 5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Lanes 1 and 2, NAD-GDH without cross-linkage treatment; lane 3, NAD-GDH cross-linked with 0.005% glutaraldehyde. The protein samples in lanes 1 and 3 were treated with 1% β-mercaptoethanol, while the sample in lane 2 was not. The molecular mass markers were the large subunit of glutamate synthase from P. aeruginosa (160 kDa [26]), ferritin from horse spleen (220 kDa for the monomer and 440 kDa for the cross-linked dimmer: Pharmacia), and thyroglobulin from hog thyroid (335 kDa for the monomer and 670 kDa for the cross-linked dimer; Pharmacia).

Optimal pH.

The deamination and amination activities of NAD-GDH were examined as a function of pH. The results (data not shown) showed that the optimal pH for deamination and amination in HEPES buffer were 9.0 and 8.0, respectively. NAD-GDH was significantly more stable in this buffer than in Tris-HCl or triethanolamine buffer at the same pH. The amination activity was approximately 11-fold higher than the deamination activity at pH 8.0, whereas the deamination activity was twofold higher than the amination activity at pH 9.0.

Kinetic and allosteric properties.

The enzyme was found to be very specific with respect to the coenzyme, NAD+, in that the rate of utilization of 5 mM NADP+ was negligible. Similarly, the enzyme was also very specific with respect to glutamate, with negligible rates observed with 50 mM l-aspartate, l-arginine, or l-norvaline.

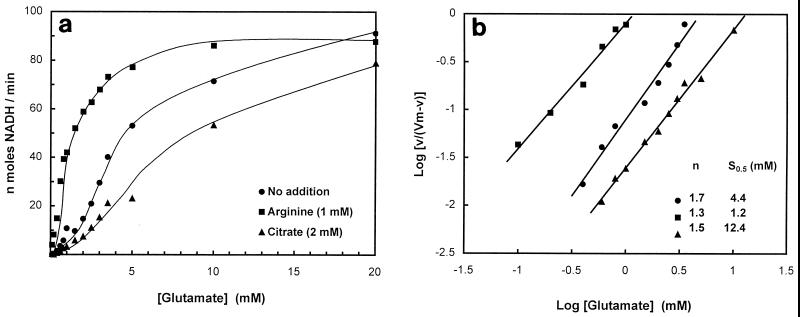

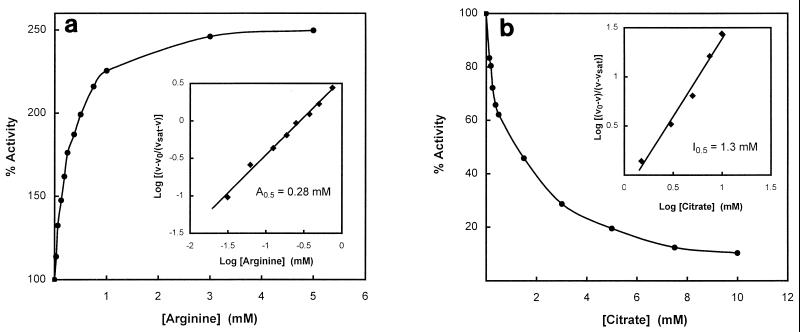

NAD-GDH deamination activity was determined as a function of the concentration of glutamate or NAD+. The glutamate saturation curve was sigmoidal, and a Hill plot of the data (Fig. 4) yielded an interaction coefficient of 1.7, indicating positive cooperativity in glutamate binding. This plot yielded an S0.5 of 4.4 mM. In contrast, the double-reciprocal plot for NAD (not shown) was linear, yielding a Km value of 0.13 mM.

FIG. 4.

(a) Glutamate saturation curves obtained in the absence of allosteric effectors (circles) or in the presence of 1 mM l-arginine (squares) or 2 mM citrate (triangles). (b) Hill plots of the data. The calculated Hill coefficients (n) and S0.5 values (the concentration of glutamate to reach half of the maximal velocity) are indicated.

A number of amino acids, including arginine, and TCA cycle intermediates were tested for the possibility that they might function as allosteric effectors for NAD-GDH. Significantly, the enzyme activity was stimulated by arginine, and the extent of stimulation was higher at nonsaturating concentrations of glutamate (Fig. 4). A Hill plot of the data (Fig. 4) yielded an S0.5 for glutamate of 1.2 mM in the presence of 1 mM arginine, indicating that arginine influences enzyme activity by increasing the affinity for glutamate. The interaction coefficient under these conditions was 1.3. NAD-GDH activity was examined as a function of arginine concentration at saturating NAD+ (5 mM) and nonsaturating glutamate (2.5 mM). The activation curve is shown in Fig. 5a. A Hill plot of the data (Fig. 5a) yielded an A0.5 (concentration required for half-maximal activation) of 0.28 mM. Aspartate and ornithine also stimulated NAD-GDH activity but to a lesser extent than arginine (A0.5 values of 1.2 and 8.3 mM, respectively; data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Activator and inhibitor saturation curves. The enzyme was assayed as described in Materials and Methods except that the concentrations of glutamate used for arginine activation (a) and for citrate inhibition (b) were 2.5 and 5.0 mM, respectively. Hill plots of the data are shown as insets. The data for arginine activation and citrate inhibition were treated as described by Govons et. al. (16) and Atkinson (1), respectively. vsat, the rate in the presence of a saturating level of allosteric effectors; v0, the rate of the reaction in the absence of allosteric effectors; v, the rate of the reaction in the presence of effectors.

The TCA cycle intermediate citrate was also found to be an effective inhibitor of NAD-GDH. The S0.5 for glutamate increased to 12.4 mM in the presence of 2 mM citrate (Fig. 4). The inhibition curve at nonsaturating glutamate (5 mM) is shown in Fig. 5b. A Hill plot of the data in the inset yields an I0.5 (concentration required for half-maximal inhibition) of 1.3 mM.

DISCUSSION

The tetrameric structure of NAD-GDH from P. aeruginosa and the molecular mass of its protomer (182 kDa) differ from those reported (6, 10) for previously characterized glutamate dehydrogenases from bacteria. All other bacterial enzymes, including the NADP+-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase from P. aeruginosa, have been reported to be hexamers of identical subunits with molecular masses between 48 and 55 kDa (6, 10, 25). This hexameric structure and the relatively small molecular mass of subunits have hitherto appeared as primary characteristics of bacterial glutamate dehydrogenases, regardless of their specificity for NAD+ or NADP+ (6). Interestingly, the tetrameric nature of NAD-GDH from P. aeruginosa is similar to the structures of the eukaryotic NAD+-dependent enzymes from yeasts and Neurospora crassa (20, 43, 44). However, the molecular masses for the fungal protomers have been determined to be 110 kDa (20, 43, 44) and thus are also significantly smaller than that for NAD-GDH from P. aeruginosa. Perhaps, more significantly, the allosteric activation by arginine and inhibition by citrate, described here for the NAD-GDH from P. aeruginosa, have not been reported for any of the previously characterized glutamate dehydrogenases. Thus, the structure, protomer mass, and sensitivity to allosteric effectors all indicate that NAD-GDH of P. aeruginosa represents a novel class of microbial glutamate dehydrogenases.

It is important that the allosteric properties of NAD-GDH from P. aeruginosa proved to be sensitive properties of this enzyme. In fact, while NAD-GDH activity was found to be subject to activation by arginine and inhibition by citrate in cell extracts of P. aeruginosa, initial attempts at purification yielded preparations that were insensitive to these effectors. It was only after the ionic strength was increased by the addition of NaCl and EDTA to all solutions that it was possible to obtain homogeneous preparations that exhibited the allosteric properties described in Results. It remains to be determined how these allosteric properties are influenced, if any, by the self-association of NAD-GDH that was observed during gel filtration.

The cofactor specificity correlates with the physiological function of a given GDH in that NADP+- and NAD+-dependent enzymes serve in reductive biosynthesis and in oxidative degradation, respectively (2). Consistent with this premise, NAD-GDH from P. aeruginosa is induced most effectively by arginine and this induction requires ArgR; the induction level is ninefold higher with arginine relative to glutamate when these amino acids serve as sole sources of carbon and nitrogen. Furthermore, the activity of NAD-GDH from this organism is subject to allosteric activation by arginine. These results support the hypothesis that NAD-GDH of P. aeruginosa specifically functions in arginine catabolism by conversion of glutamate, the product of the AST pathway, into 2-oxoglutarate and the subsequent replenishment of succinyl coenzyme A, which is required in the first step in this pathway. The observed inhibition by citrate is also of physiological significance: it is one of the best carbon and energy sources for P. aeruginosa. Accordingly, the availability of citrate should reasonably inhibit the utilization of arginine as a source of carbon and energy. Interestingly, both of the allosteric effectors, arginine and citrate, were shown to act by influencing the affinity of NAD-GDH for glutamate (Fig. 4). Thus, it is reasonable to conclude that in vivo activity of NAD-GDH of P. aeruginosa is controlled by the concentrations of glutamate and effectors. The significance of the observed activation by aspartate is not obvious.

Inactivation of gdhB increased the doubling time by only 33% (from 75 to 100 min) when cells were grown in minimal medium supplemented with arginine as a sole source of carbon and nitrogen. The substantial residual ability to utilize arginine as a sole source of carbon and nitrogen in the absence of the NAD-GDH must reflect the availability of multiple pathways that can generate ammonia and TCA cycle intermediates in this organism. In the absence of NAD-GDH, P. aeruginosa can still utilize the arginine dehydrogenase and/or the arginine decarboxylase pathway (Fig. 1) to generate the TCA cycle intermediate succinate (17). Under these conditions, ammonia can be still generated by the AST pathway as well as by the dehydrogenase pathway. Furthermore, some glutamate can be still converted to 2-oxoglutarate by the NADP-GDH as well as by transaminases, consistent with the ability of the gdhB derivative to utilize glutamate at the same rate as the wild-type parent.

Primer extension experiments established that gdhB is expressed from an arginine-inducible promoter and that this induction requires a functional ArgR. This ArgR is presumed to act at a putative ArgR operator site adjacent to the −35 region of the arginine-inducible promoter (Fig. 2). Comparison of this site with previously characterized ArgR operators (Fig. 6) showed that the ArgR operator of gdhB is similar in consisting of a degenerated first-half site and a more conserved second-half site. The sequence of the second-half site was found to be identical to the consensus sequence of the ArgR operator, TGTCGCN6GNAAN5 (31). Regarding the promoter/operator topology, in operons where ArgR functions as a direct activator, as is the case here, the ArgR protein is similar to the AraC protein in that the operator consists of two direct repeats with the proximal half site overlapping the −35 region of the promoter (13).

FIG. 6.

Sequence alignment of ArgR binding sites. The first and second halves of the binding sites (I and II) are depicted by arrows. The consensus sequence was deduced from the second-half sites, which are more conserved. Nucleotides identical to those of the consensus site are shaded. ς70-RNP, RNA polymerase holoenzyme; −35 and −10, positions of the promoter recognized by ς70; ANR, the anaerobic regulator of P. aeruginosa (12); A, activation; R, repression. The sequences shown for arcD,, oprD, and argF are for the complementary stands and are in the opposite orientation from the direction of transcription.

Recent work by Belitsky and Sonenshein (4) has shown that NAD-GDH of Bacillus subtilis, encoded by rocG, is induced by arginine but not by glutamate. However, unlike NAD-GDH from P. aeruginosa, described here, the amino acid sequence of the enzyme from B. subtilis was reported to be very similar to many other hexameric glutamate dehydrogenases from different bacterial species (4). In contrast, the tetrameric NAD-GDHs from Neurospora crassa and yeasts, which are presumed to function specifically in glutamate catabolism, are indeed induced by glutamate (21, 40), as well as by carbon or nitrogen starvation (33, 45). However, it would be interesting to know whether these eukaryotic NAD-GDHs are also inducible by arginine. Interestingly, expression of the NAD-GDH (rocG) from B. subtilis requires a functional AhrC, the arginine regulatory protein of this organism (35). However, AhrC is similar in structure and derived sequence to the enteric ArgR proteins (28, 29, 35), rather than the AraC/XylS family (13) as is the case with ArgR of P. aeruginosa (37, 38). Furthermore, AhrC of B. subtilis functions in conjunction with RocR, a member of the NtrC/NifA family of proteins (8, 15), which acts at an enhancer-like element located upstream of the ς54 promoter for rocG (3). Thus, the mechanism of induction of rocG in B. subtilis appears more similar to that reported from this laboratory for activation of the ast operon, encoding the AST pathway in enteric bacteria (30).

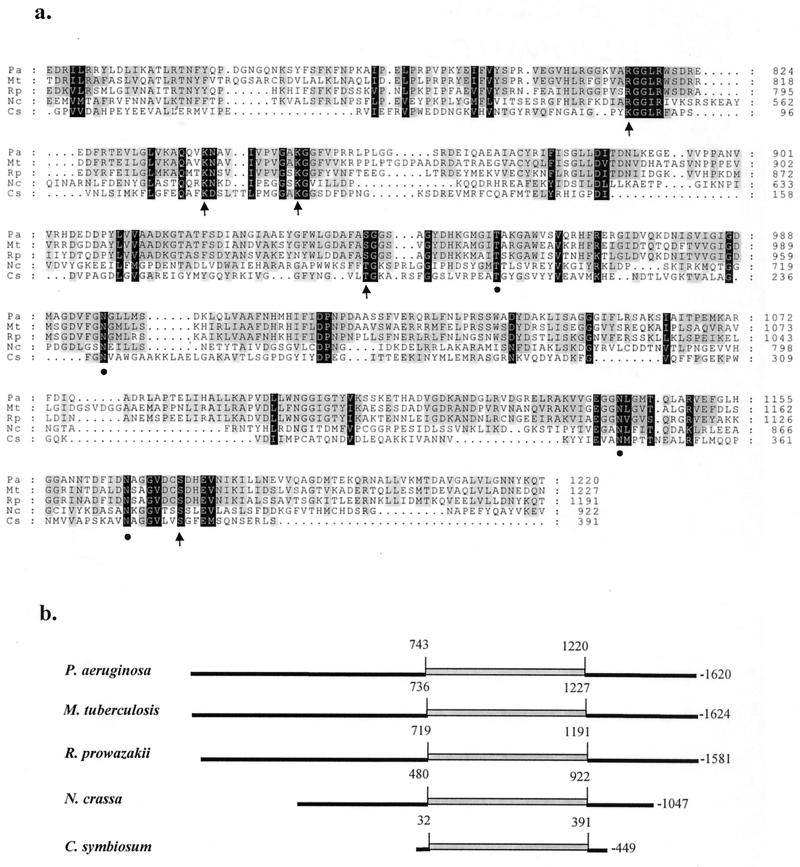

Comparison of the derived amino acid sequence of the 182-kDa NAD-GDH from P. aeruginosa with the GenBank database identified hypothetical polypeptides with similar sizes and high degrees of homology from Pseudomonas putida, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Rickettsia prowazekii, Legionella pneumophila, Vibrio cholerae, Shewanella putrefaciens, Sinorhizobium meliloti, and Caulobacter crescentus. Multiple sequence alignment by Clustal W (42) (Fig. 7a) show that the derived sequences for the two polypeptides from M. tuberculosis and R. prowazakii exhibit overall identity of 37% (28 gaps) and 32% (19 gaps), respectively, to GdhB of P. aeruginosa. Furthermore, the sequence identity is more pronounced (average of 60% with five gaps) for the central domain of GdhB (amino acid residues 740 to 1220 of Pseudomonas NAD-GDH) than for the N- and C-terminal domains (average of 24% with 17 gaps and 28% with 2 gaps, respectively). When the derived sequence of NAD-GDH from P. aeruginosa is compared to the sequence of the 110- kDa NAD-GDH from Saccharomyces cerevisiae or N. crassa, the central domain of Pseudomonas NAD-GDH exhibits a lower degree of homology with more gaps (average 24% identity with 31 gaps) than those observed with the hypothetical polypeptides from M. tuberculosis and R. prowazakii. In comparison with the yet smaller GDH of other prokaryotes (50 to 60 kDa), the observed homology is essentially limited to residues important for binding of substrates and for catalytic function. Previous sequence analysis by other laboratories of hexameric glutamate dehydrogenases from diverse sources (2) has shown that these enzymes exhibit poor homology for the N-terminal 50 residues but exhibit long stretches of highly homologous sequences for the next 350 residues. At the C terminus, the homology can be divided into two classes for enzymes from nonvertebrate and vertebrate sources (2).

FIG. 7.

Amino acid sequence alignment of NAD-dependent glutamate dehydrogenases. Sequences were aligned with the Clustal W program (42). Only the central region of P. aeruginosa NAD-GDH containing the substrate binding and catalytic domains and its counterparts in other polypeptides are shown here. Pa, P. aeruginosa; Mt, M. tuberculosis (C70867 7478113); Rp, R. prowazekii (7467847); Nc, N. crassa (432554); Cs, C. symbiosum (231986). Numbers in parentheses represent the NCBI database reference numbers. Amino acid residues of C. symbiosum GDH that have been reported (2) to be important for glutamate binding and catalysis (K89, K113, K125, T193, and S380) and for NAD-binding (T209, N240, N347, and N373) are labeled with arrows and filled circles, respectively.

Given the high level of similarity for the hexameric microbial glutamate dehydrogenases, the analysis presented here focuses on the NAD-GDH of Clostridium symbiosum, which functions in glutamate fermentation and for which the three-dimensional structure has been determined (2, 6). Residues that were identified in the clostridial enzyme as important for glutamate binding and catalysis (Lys89, Lys113, Lys125, Thr193, and Ser380; Fig. 7a, arrows) and for NAD binding (Thr209, Asn240, Asn347, and Asn373; Fig. 7a, filled circles) are conserved in NAD-GDH from P. aeruginosa.

A schematic representation of the sequence comparison is presented in Fig. 7b. The obvious question yet to be answered is in regard to the functions of the N- and C-terminal domains for the larger tetrameric glutamate dehydrogenases from fungi and the yet larger enzyme from P. aeruginosa. One of these domains is likely involved in the allosteric regulation reported here for NAD-GDH from this organism. Similarly, it is likely that one of the corresponding domains in yeasts is responsible for the reported (19, 20) inactivation by phosphorylation under conditions of glutamate starvation.

Whether the homologues of NAD-GDH of P. aeruginosa that were identified from sequence data as hypothetical proteins in other bacteria prove to be also NAD+-dependent dehydrogenases that function in arginine utilization remains to be determined. The preponderance of these homologues in pathogenic or potentially pathogenic microorganisms, as outlined above, raises the intriguing question as to whether the ability to utilize arginine as a source of carbon and nitrogen might possibly confer a selective advantage on such organisms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Deborah Walthall for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by research grant MCB-9985660 from the National Science Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atkinson D E. Regulation of enzyme activity. Annu Rev Biochem. 1966;35:89–93. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker P J, Britton K L, Engel P C, Farrants G W, Lilley K S, Rice D W, Stillman T J. Subunit assembly and active site location in the structure of glutamate dehydrogenase. Proteins. 1992;12:75–86. doi: 10.1002/prot.340120109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belitsky B R, Sonenshein A L. An enhancer element located downstream of the major glutamate dehydrogenase gene of Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;96:10290–10295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belitsky B R, Sonenshein A L. Role and regulation of Bacillus subtilis glutamate dehydrogenase genes. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6298–6305. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6298-6305.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradford M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Britton K L, Baker P J, Rice D W, Stillman T J. Structural relationship between the hexameric and tetrameric family of glutamate dehydrogenase. Eur J Biochem. 1992;209:851–859. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown C M, MacDonald-Brown D S, Stanley S D. The mechanisms of nitrogen assimilation in Pseudomonads. Antonie Leewenhoek J Microbiol. 1973;16:1319–1324. doi: 10.1007/BF02578844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calogero S, Gardan R, Glaser P, Schweizer J, Rapoport G, Debarbouille M. RocR, a novel regulatory portein controlling arginine utilization in Bacillus subtilis, belongs to the NtrC/NifA family of transcriptional activators. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1234–1241. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.5.1234-1241.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craven R, Montie T C. Regulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa chemotaxis by the nitrogen source. J Bacteriol. 1985;164:544–549. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.2.544-549.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fraia R D, Wilquet V, Ciardiello M A, Carratore V, Antignani A, Camardella L, Glansdorff N, Prisco G D. NADP-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase in the antarctic psychrotolerant bacterium Psychrobacter sp. TAD1. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:121–131. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.00972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fruh R, Haas D, Leisinger T. Altered control of glutamate dehydrogenases in ornithine utilization mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Arch Microbiol. 1985;141:170–176. doi: 10.1007/BF00423280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galimand M, Gamper M, Zimmermann A, Haas D. Positive FNR-like control of anaerobic arginine degradation and nitrate respiration in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1598–1606. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.5.1598-1606.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallegos M-T, Schleif R, Bairoch A, Hofmann K, Ramos J L. AraC/XylS family of transcriptional regulators. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:393–410. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.4.393-410.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gambello J R, Iglewski B H. Cloning and characterization of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa lasR gene, a transcriptional activator of elastase expression. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3000–3009. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.3000-3009.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardan R, Rapoport G, Debarbouille M. Role of the transcriptional activator RocR in the arginine-degradation pathway of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:825–837. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3881754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Govons S, Gentner N, Greenberg E, Preiss J. Biosynthesis of bacterial glycogen. XI. Kinetic characterization of an altered adenosine diphosphate-glucose synthase from a “glycogen-excess” mutant of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:1731–1740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haas D, Galimands M, Gamper M, Zimmermann A. Arginine network of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: specific and global controls. In: Silver S, Chakrabarty A-M, Iglewski B, Kaplan S, editors. Pseudomonas. Biotransformations, pathogenesis, and evolving biotechnology. Washington, D. C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1990. pp. 303–316. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haas D, Holloway B W, Schambock A, Leisinger T. The genetic organization of arginine biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Gen Genet. 1977;154:7–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00265571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hemmings B A. Phosphorylation of NAD-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase from yeast. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:5255–5258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hemmings B A. Purification and properties of the phospho and dephospho forms of yeast NAD-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:7925–7932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hollenberg C P, Riks W F, Borst P. The glutamate dehydrogenase of yeast: extra-mitochondrial enzymes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1970;201:13–19. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(70)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Itoh Y. Cloning and characterization of the aru genes encoding enzymes of the catabolic arginine succinyltransferase pathway in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7280–7290. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7280-7290.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jann A, Stalon V, Vander Wauven C, Leisinger T, Haas D. N2-succinylated intermediates in an arginine catabolic pathway of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:4937–4941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janssen D B, op den Camp H J, Leenen P J, van der Drift C. The enzymes of the ammonia assimilation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Arch Microbiol. 1980;124:197–203. doi: 10.1007/BF00427727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joannou C L, Brown P R, Tata R. Mutants affecting the synthesis of NADP-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase in Pseudomonas aeruginsa. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:441–452. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-2-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwon D-H. Ph.D. thesis. Atlanta: Georgia State University; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwon D H, Lu C D, Walthall D A, Brown T M, Houghton J E, Abdelal A T. Structure and regulation of the carAB operon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Pseudomonas stutzeri: no untranslated region exists. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2532–2542. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.9.2532-2542.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim D B, Oppenheim J D, Eckhardt T, Maas W K. Nucleotide sequence of the argR gene of Escherichia coli K-12 and isolation of its product, the arginine repressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:6697–6701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.19.6697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu C D, Houghton J E, Abdelal A T. Characterization of the arginine repressor from Salmonella typhimurium and its interactions with the carAB operator. J Mol Biol. 1992;225:11–24. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)91022-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu C-D, Abdelal A T. Role of ArgR in activation of the ast operon, encoding enzymes of the arginine succinyltransferase pathway in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1934–1938. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.6.1934-1938.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu C-D, Winteler H, Abdelal A, Haas D. The ArgR regulatory protein, a helper to the anaerobic regulator ANR during transcriptional activation of the arcD promoter in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2459–2464. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.8.2459-2464.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller S M, Magasanik B. Role of NAD-linked glutamate dehydrogenase in nitrogen metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4927–4935. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.4927-4935.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishijyo T, Park S M, Lu C D, Itoh Y, Abdelal A T. Molecular characterization and regulation of an operon encoding a system for transport of arginine and ornithine and the ArgR regulatory protein in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5559–5566. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.21.5559-5566.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.North A K, Smith M C, Baumberg S. Nucleotide sequence of a Bacillus subtilis arginine regulatory gene and homology of its product to the Escherichia coli arginine repressor. Gene. 1989;80:29–38. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90247-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ochs M M, Lu C-D, Hancock R E, Abdelal A T. Amino acid-mediated induction of the basic amino acid-specific outer membrane porin OprD from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5426–5432. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.17.5426-5432.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park S-M, Lu C-D, Abdelal A T. Cloning and characterization of argR, a gene that participates in regulation of arginine biosynthesis and catabolism in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5300–5308. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5300-5308.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park S-M, Lu C-D, Abdelal A T. Purification and characterization of an arginine regulatory protein, ArgR, from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and its interactions with the control regions for the car, argF, and aru operons. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5309–5317. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5309-5317.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schweizer H P. Small broad-host-range gentamycin resistance gene cassettes for site-specific insertion and deletion mutagenesis. BioTechniques. 1993;15:831–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stachow C S, Sanwal B D. Regulation, purification, and some properties of the NAD-specific glutamate dehydrogenase of Neurospora. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1967;139:294–307. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(67)90033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stibitz S, Black W, Falkow S. The construction of a cloning vector designed for gene replacement in Bordetella pertusis. Gene. 1986;50:133–140. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gilson T J. Clustal W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4674–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uno I, Matsumoto K, Adachi K, Ishikawa T. Regulation of NAD-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase by protein kinases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:1288–1293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Veronese F M, Nyc J F, Degani Y, Brown D M, Smith E L. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-specific glutamate dehydrogenase of Neurospora. I. Purification and molecular properties. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:7922–7928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vierula P J, Kapoor M. A study of derepression of NAD-specific glutamate dehydrogenase of Neurospora crassa. J Gen Microbiol. 1986;132:907–915. doi: 10.1099/00221287-132-4-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]