Key Points

Question

What is the efficacy of once-daily roflumilast cream, 0.3%, in patients with plaque psoriasis?

Findings

In 2 phase 3 randomized clinical trials with 881 participants combined, Investigator Global Assessment success at 8 weeks in the group treated with roflumilast cream vs vehicle cream was 42.4% vs 6.1% in one trial and 37.5% vs 6.9% in the other trial. Both differences were statistically significant.

Meaning

Roflumilast cream resulted in better chronic plaque psoriasis clinical status compared with vehicle cream at 8 weeks; further research is needed to compare efficacy with other active treatments and to assess longer-term efficacy and safety.

Abstract

Importance

Once-daily roflumilast cream, 0.3%, a potent phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, demonstrated efficacy and was well tolerated in a phase 2b trial of patients with psoriasis.

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy of roflumilast cream, 0.3%, applied once daily for 8 weeks in 2 trials of patients with plaque psoriasis.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Two phase 3, randomized, double-blind, controlled, multicenter trials (DERMIS-1 [trial 1; n = 439] and DERMIS-2 [trial 2; n = 442]) were conducted at 40 centers (trial 1) and 39 centers (trial 2) in the US and Canada between December 9, 2019, and November 16, 2020, and between December 9, 2019, and November 23, 2020, respectively. Patients aged 2 years or older with plaque psoriasis involving 2% to 20% of body surface area were enrolled. The dates of final follow-up were November 20, 2020, and November 23, 2020, for trial 1 and trial 2, respectively.

Interventions

Patients were randomized 2:1 to receive roflumilast cream, 0.3% (trial 1: n = 286; trial 2: n = 290), or vehicle cream (trial 1: n = 153; trial 2: n = 152) once daily for 8 weeks.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary efficacy end point was Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) success (clear or almost clear status plus ≥2-grade improvement from baseline [score range, 0-4]) at week 8, analyzed using a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test stratified by site, baseline IGA score, and intertriginous involvement. There were 9 secondary outcomes, including intertriginous IGA success, 75% reduction in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score, and Worst Itch Numeric Rating Scale score of 4 or higher at baseline achieving 4-point reduction (WI-NRS success) at week 8 (scale: 0 [no itch] to 10 [worst imaginable itch]; minimum clinically important difference, 4 points).

Results

Among 881 participants (mean age, 47.5 years; 320 [36.3%] female), mean IGA scores in trial 1 were 2.9 [SD, 0.52] for roflumilast and 2.9 [SD, 0.45] for vehicle and in trial 2 were 2.9 [SD, 0.48] for roflumilast and 2.9 [SD, 0.47]) for vehicle. Statistically significantly greater percentages of roflumilast-treated patients than vehicle-treated patients had IGA success at week 8 (trial 1: 42.4% vs 6.1%; difference, 39.6% [95% CI, 32.3%-46.9%]; trial 2: 37.5% vs 6.9%; difference, 28.9% [95% CI, 20.8%-36.9%]; P < .001 for both). Of 9 secondary end points, statistically significant differences favoring roflumilast vs vehicle were observed for 8 in trial 1 and 9 in trial 2, including intertriginous IGA success (71.2% vs 13.8%; difference, 66.5% [95% CI, 47.1%-85.8%] and 68.1% vs 18.5%; difference, 51.6% [95% CI, 29.3%-73.8%]; P < .001 for both), 75% reduction in PASI score (41.6% vs 7.6%; difference, 36.1% [95% CI, 28.5%-43.8%] and 39.0% vs 5.3%; difference, 32.4% [95% CI, 24.9%-39.8%]; P < .001 for both), WI-NRS success (67.5% vs 26.8%; difference, 42.6% [95% CI, 31.3%-53.8%] and 69.4% vs 35.6%; difference, 30.2% [95% CI, 18.2%-42.2%]; P < .001 for both). The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events was 25.2% with roflumilast vs 23.5% with vehicle in trial 1 and 25.9% with roflumilast vs 18.4% with vehicle in trial 2. The incidence of serious adverse events was 0.7% with roflumilast vs 0.7% with vehicle in trial 1 and 0% with roflumilast vs 0.7% with vehicle in trial 2.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among patients with chronic plaque psoriasis, treatment with roflumilast cream, 0.3%, compared with vehicle cream resulted in better clinical status at 8 weeks. Further research is needed to assess efficacy compared with other active treatments and to assess longer-term efficacy and safety.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifiers: NCT04211363, NCT04211389

These randomized clinical trials assess the effect of roflumilast cream, 0.3%, compared with vehicle cream on clinical status at 8 weeks among patients with chronic plaque psoriasis.

Introduction

Roflumilast is a selective, highly potent phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor with greater affinity for PDE4 than other marketed PDE4 inhibitors.1,2 An oral formulation of roflumilast is approved as a treatment to reduce risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease associated with chronic bronchitis and history of exacerbations.3 Topical roflumilast is being evaluated in clinical trials for several dermatologic conditions, including psoriasis (approved for plaque psoriasis on July 29, 2022, by the US Food and Drug Administration), atopic dermatitis, and seborrheic dermatitis.2,4 In a 12-week, phase 2b study among 331 patients with plaque psoriasis, significantly more roflumilast-treated patients than vehicle-treated patients were clear or almost clear on the Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) at week 6 (primary end point).4 A 52-week, open-label safety study demonstrated maintenance of efficacy for chronic plaque psoriasis and no new safety signals with long-term treatment.5 This article describes results of 2 phase 3 trials evaluating efficacy and safety of roflumilast cream, 0.3%, applied once daily for 8 weeks in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis.

Methods

Study Design

DERMIS-1 (trial 1) and DERMIS-2 (trial 2) were identically designed randomized, parallel-group, double-blind, vehicle-controlled studies. Patients were treated and assessed at 40 centers (trial 1) and 39 centers (trial 2) in the United States and Canada. These trials were conducted in accordance with ethical principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki6 and the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use guideline E6. The study protocol and statistical analysis plans are available in Supplement 1 and Supplement 2 (trial 1) and Supplement 3 and Supplement 4 (trial 2).

Participants

Patients eligible for inclusion were aged 2 years or older with clinical diagnosis of plaque psoriasis for at least 6 months (at least 3 months for children), with stable disease for the previous 4 weeks, and were in otherwise good health. Psoriasis on the face, extremities, trunk, and/or intertriginous areas needed to involve 2% to 20% of body surface area, not including the scalp, palms, or soles. The baseline IGA needed to be at least mild and the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score needed to be at least 2.

Patients were excluded if they had a current diagnosis of nonplaque psoriasis (eg, guttate, erythrodermic/exfoliative, palmoplantar-only involvement, or pustular psoriasis) or planned excessive exposure to sunlight or artificial light (eg, tanning bed). Patients (and/or their guardians) provided written informed consent; assent was also obtained when applicable.

Randomization

Eligible patients were randomized 2:1 to once-daily roflumilast cream, 0.3%, or vehicle cream according to a computer-generated randomization list stratified by study site, baseline IGA score (2 vs ≥3), and intertriginous area involvement at baseline (I-IGA score <2 vs ≥2). The block size used for randomization was 6, and 2:1 randomization was used to increase the number of patients who received roflumilast and therefore provided more information on safety. Patients, investigators, clinical personnel, and the sponsor were unaware of which treatment an individual received.

Intervention

Each patient received blinded, uniquely numbered kits, each containing 4 blinded, 45-g tubes of the randomly assigned product (once-daily roflumilast cream, 0.3%, or vehicle cream). The vehicle cream consisted of the same cream formulation as the roflumilast cream (excluding the active agent) and contained the following components: purified water, the pharmaceutical solvent diethylene glycol monoethyl ether (USP), an alkyl-phosphate emulsifier, petrolatum, isopropyl palmitate, hexylene glycol, and a paraben preservative system (methylparaben and propylparaben).

If affected, palms and soles were treated but were not evaluated as part of efficacy assessments. Patients and caregivers were instructed to apply investigational product to all areas identified at baseline, even if that area cleared, as well as to any new plaques developing during the treatment period.

Outcomes

The primary efficacy end point for both studies was success on the IGA scale, defined as achievement of clear or almost clear status plus at least 2-grade improvement from baseline, at week 8.7 The IGA is a static evaluation of qualitative overall psoriasis severity that is assessed on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (clear) to 4 (severe) (eTable 1 in Supplement 5).7 Secondary efficacy end points included achievement of clear or almost clear on the I-IGA plus at least 2-grade improvement from baseline at week 8 in patients with baseline I-IGA of 2 or higher (I-IGA success); I-IGA status of clear at week 8; time to achievement of 50% reduction from baseline in PASI score; achievement of 75% reduction from baseline in PASI score8 at week 8; achievement of at least a 4-point reduction on the Worst Itch Numeric Rating Scale (WI-NRS)9 at weeks 2, 4, and 8 (in patients aged ≥12 years with a baseline WI-NRS score ≥4) (WI-NRS success); and change from baseline total score on the 16-item Psoriasis Symptom Diary (PSD)10 at weeks 4 and 8. The I-IGA assessment was conducted as for whole-body IGA, but only intertriginous areas were evaluated. For the WI-NRS, a decrease of at least 4 points is considered a clinically and qualitatively meaningful improvement in itch among patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.11 Therefore, a cut point of a WI-NRS score of 4 or higher at baseline was required to determine WI-NRS success. The following outcomes were prespecified but are not reported herein: change and percent change from baseline in PASI score, change from baseline in affected percent body surface area, change and percent change from baseline in PASI high discrimination score, percent change in PSD score, change and percent change in WI-NRS score, change and percent change in Dermatology Life Quality Index score, and change and percent change in Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index score.

Demographic information was collected for each patient, including sex, age, and race and ethnicity according to categories required by regulatory agencies. The determination of race and ethnicity categories was made by participants from a list of fixed categories with options to select race as “not reported” or “other” with an option to specify race.

Safety analyses included all treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs). Additional safety assessments included physical examinations, vital signs, weight, clinical laboratory results, Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale, and depression, measured at screening, baseline, week 4, and week 8. To measure changes in depression, the Children’s Depression Inventory 2 Parent Report Form, the modified Patient Health Questionnaire 9 for Adolescents depression scale, and the Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale were administered to patients aged 6 to 11 years, 12 to 17 years, and 18 years or older, respectively. The Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale and modified Patient Health Questionnaire 9 for Adolescents depression scale are assessed as the sum of responses on 8 questions with scores ranging from none or minimal depression (0-4) to severe depression (20-24).

Sample Size Calculation

A sample size of approximately 400 patients (approximately 267 receiving roflumilast cream and 133 receiving vehicle cream) was planned for each trial. This allowed greater than 99% power to detect a 22.4% difference between treatments on IGA success at α = .05 using a 2-sided χ2 test. Results from the phase 2b study of roflumilast cream compared with vehicle cream were used to estimate the treatment difference. In this prior trial, 32.2% of patients in the roflumilast group and 9.8% of patients in the vehicle group reported IGA success at week 8.4

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). The primary end point was analyzed using a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test stratified by site, baseline IGA score, and baseline intertriginous involvement. Secondary end points were tested statistically only if the primary end point was statistically significant (eFigure in Supplement 5). To control for type I error for multiple comparisons among the secondary end points, a multiplicity procedure was used. On successful testing of the primary end point, the α was partitioned to test secondary end points in families 2 and 3 (partition 1) and to test WI-NRS time points (partition 2). An α = .03 was assigned to partition 1, in which the end points in family 2 (time to achievement of 50% reduction from baseline in PASI score, 75% reduction from baseline in PASI score at week 8, and I-IGA success at week 8) were tested hierarchically. The remaining end points were tested in family 3 of partition 1 (change from baseline in total PSD score at weeks 8 and 4 and I-IGA status of clear at week 8) using the α available after testing family 2 and the Holm procedure to control for multiple comparisons. For partition 2, an α = .02 was allocated to sequentially test WI-NRS success at week 8, then week 4, then week 2. For the primary end points, statistical significance was concluded at the 5% significance level (2-sided). Statistical significance was concluded at the corresponding partitioned α level for secondary end points. No adjustments for multiple comparisons were made for end points tested outside of the prespecified multiplicity procedure, and unadjusted P values are denoted as nominal and can be considered exploratory. Analyses of the primary outcome were repeated by age group.

Continuous end points were analyzed using analysis of covariance that included treatment, site, baseline IGA, baseline intertriginous involvement, and the baseline value for the variable under analysis. Statistical comparisons between treatment groups were obtained using contrasts. These analyses were performed for all randomized patients according to their randomization group. For the efficacy end points, except time to achievement of 50% reduction from baseline in PASI score, missing scores were imputed using a regression-based multiple imputation model. For all other analyses, missing data were not imputed and data were analyzed as observed using descriptive statistics. Loss to follow-up and withdrawal were handled as missing values. The population for analysis of I-IGA was patients with I-IGA scores of 2 or higher at baseline. The WI-NRS analyses were based on patients with WI-NRS scores of 4 or higher at baseline. The safety population in each study included all patients who received at least 1 dose of roflumilast cream, 0.3%, or vehicle cream. For time to achievement of 50% reduction from baseline in PASI score, data were summarized using Kaplan-Meier methods and the difference between treatment groups was evaluated using the log-rank statistic and 95% confidence intervals of the median for each group.

Results

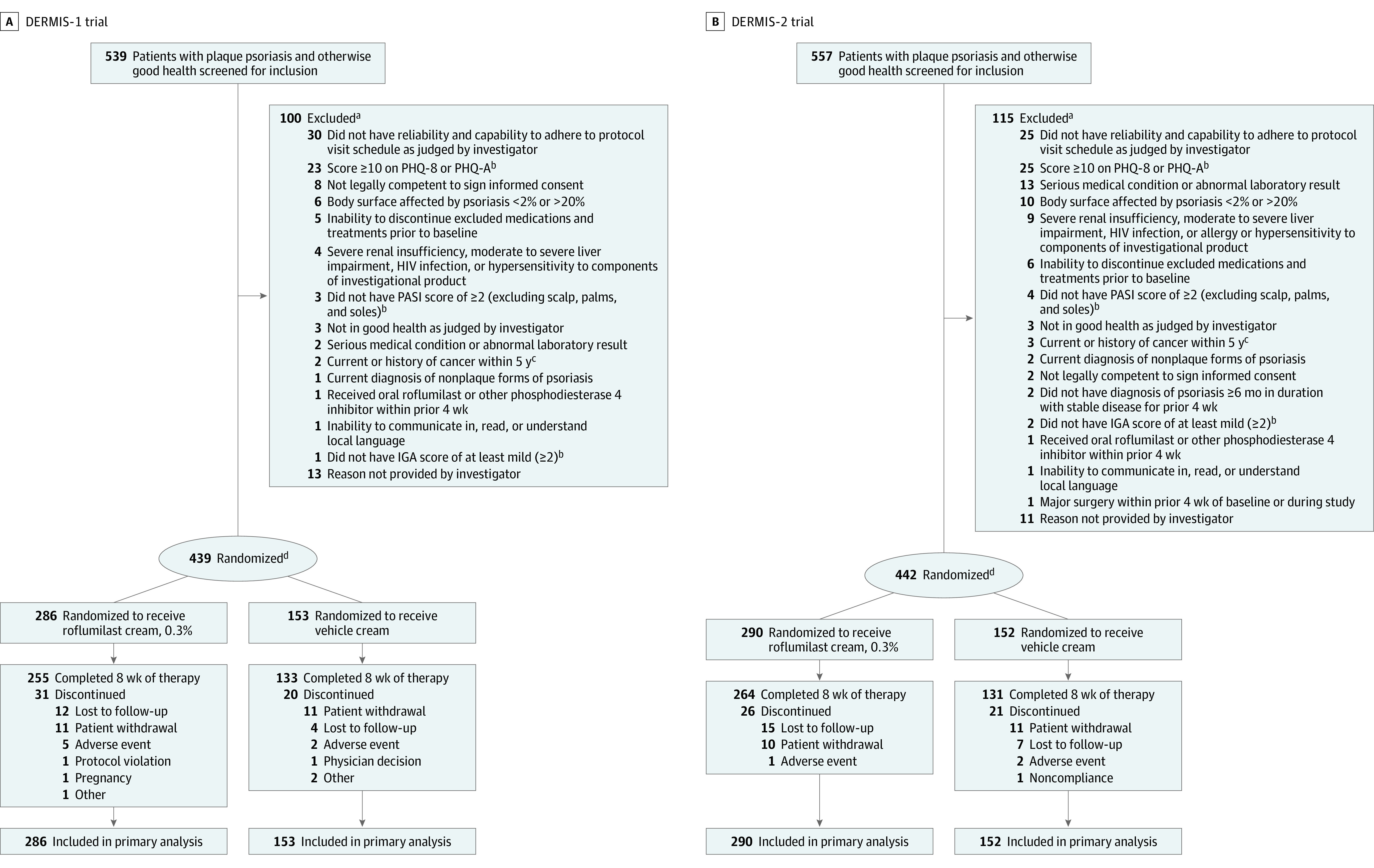

In trial 1, between December 9, 2019, and November 16, 2020, 539 patients were screened for eligibility, 100 were determined ineligible, 439 were enrolled, and 388 (88.4%) completed the study (Figure 1). For trial 2, between December 9, 2019, and November 23, 2020, 557 patients were screened for eligibility, 115 were determined ineligible, 442 were enrolled; and 395 (89.4%) completed the study (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics in the roflumilast and vehicle groups were well matched across studies (Table 1).

Figure 1. Patient Disposition in the DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2 Trials.

aExcluded participants could have ≥1 reasons for ineligibility/nonenrollment.

bDescriptions of PHQ-8 and modified PHQ-A are in the Methods; descriptions of PASI7 and IGA8 are in Table 1 footnotes.

cExcept fully treated basal cell carcinoma, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, or carcinoma in situ of the cervix.

dRandomization was stratified by study site, baseline IGA score (2 vs ≥3), and intertriginous involvement at baseline (I-IGA score >2, yes vs no; I-IGA evaluated on a scale of 0 [clear] to 4 [severe]).

Table 1. Baseline Participant Characteristics.

| Characteristics | DERMIS-1 trial | DERMIS-2 trial | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roflumilast (n = 286) | Vehicle (n = 153) | Roflumilast (n = 290) | Vehicle (n = 152) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 47.6 (14.09) | 48.7 (15.77) | 46.9 (15.07) | 47.1 (14.07) |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||||

| Female | 97 (33.9) | 57 (37.3) | 114 (39.3) | 52 (34.2) |

| Male | 189 (66.1) | 96 (62.7) | 176 (60.7) | 100 (65.8) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 32.0 (9.5) | 31.9 (7.9) | 31.0 (7.0) | 33.5 (13.7) |

| Ethnicity, No. (%)a | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 63 (22.0) | 34 (22.2) | 76 (26.2) | 50 (32.9) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 223 (78.0) | 119 (77.8) | 213 (73.4) | 102 (67.1) |

| Race, No. (%)a | ||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 4 (1.4) | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 1 (0.7) |

| Asian | 21 (7.3) | 11 (7.2) | 20 (6.9) | 9 (5.9) |

| Black or African American | 8 (2.8) | 8 (5.2) | 13 (4.5) | 9 (5.9) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 2 (0.7) | 0 | 3 (1.0) | 1 (0.7) |

| White | 234 (81.8) | 124 (81.0) | 240 (82.8) | 126 (82.9) |

| Not reported | 4 (1.4) | 3 (2.0) | 5 (1.7) | 2 (1.3) |

| Otherb | 11 (3.8) | 5 (3.3) | 8 (2.8) | 4 (2.6) |

| More than 1 race | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

| Psoriasis-affected BSA, mean (SD), %c,d | 6.3 (4.4) | 7.4 (4.8) | 7.1 (4.8) | 7.7 (5.1) |

| IGA scored,e | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.9 (0.52) | 2.9 (0.45) | 2.9 (0.48) | 2.9 (0.47) |

| No. (%) | ||||

| 2 (Mild) | 51 (17.8) | 20 (13.1) | 50 (17.2) | 24 (15.8) |

| 3 (Moderate) | 206 (72.0) | 122 (79.7) | 220 (75.9) | 118 (77.6) |

| 4 (Severe) | 29 (10.1) | 11 (7.2) | 20 (6.9) | 10 (6.6) |

| PASI score, mean (SD)d,f | 6.3 (3.15) | 6.8 (3.70) | 6.5 (3.22) | 7.0 (3.52) |

| WI-NRS scoreg | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 5.7 (2.75) | 5.7 (2.84) | 5.8 (2.61) | 6.1 (2.75) |

| ≥4, No. (%) | 218 (76.2) | 115 (75.2) | 229 (79.0) | 116 (76.3) |

| PSD total score, mean (SD)h | 72.1 (42.75) | 73.4 (41.29) | 69.3 (40.66) | 77.4 (41.24) |

| Psoriasis area of involvement, No. (%) | ||||

| Face | 74 (25.9) | 45 (29.4) | 76 (26.2) | 39 (25.7) |

| Genitalia | 51 (17.8) | 21 (13.7) | 46 (15.9) | 19 (12.5) |

| Intertriginous areas | 68 (23.8) | 33 (21.6) | 56 (19.3) | 32 (21.1) |

| Intertriginous IGA (I-IGA) score | ||||

| ≥2, No. (%)i | 63 (22.0) | 32 (20.9) | 53 (18.3) | 31 (20.4) |

| Among patients with mild to severe I-IGA involvement, mean (SD)j | 2.4 (0.70) | 2.5 (0.56) | 2.4 (0.69) | 2.6 (0.62) |

| No. (%) | ||||

| 0 (Clear) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3)k | 0 |

| 1 (Almost clear) | 5 (1.7) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) |

| 2 (Mild) | 33 (11.5) | 16 (10.5) | 25 (8.6) | 13 (8.6) |

| 3 (Moderate) | 27 (9.4) | 16 (10.5) | 27 (9.3) | 17 (11.2) |

| 4 (Severe) | 3 (1.0) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.7) |

Race and ethnicity categories were self-reported by participants from a list of fixed categories, with options to select race as “not reported” or “other” with an option to specify.

Other included participants identifying as Afghanistani, Brazilian, Caribbean, Canadian Indian, Egyptian, Filipino, Guyanese, Hispanic, Latino/Latin, Middle Eastern, South Asian, Vietnamese, and West Indian.

Determined by the patient’s hand method, in which a patient’s hand (including fingers) surface area was assumed to equal 1% of body surface area (BSA).

If affected, palms and soles were treated but not counted toward any efficacy assessments. Scalp was not treated and did not count toward any efficacy assessments.

The Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) is a static evaluation of qualitative overall psoriasis severity assessed on a 5-point scale (0 [clear] to 4 [severe]).7

The Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) combines assessment of the severity of lesions and the area affected into a single score ranging from 0 (no disease) to 72 (maximal disease).8

The Worst Itch Numeric Rating Scale (WI-NRS) is a single item to assess patient-reported severity of the highest intensity of itch during the previous 24 hours on a scale from 0 (no itch) to 10 (worst imaginable itch).9

Patients used the Psoriasis Symptom Diary (PSD) to determine the severity and impact of psoriasis-related signs and symptoms over the past 24 hours, rating each variable in the 16-item assessment on a 0-10 scale for a total score ranging from 0-160, with higher scores indicating greater severity or burden.10

Patients with intertriginous area involvement and with at least mild severity of the intertriginous lesions (I-IGA ≥2) at baseline.

Patients with intertriginous area involvement of at least mild severity (I-IGA ≥2) at baseline using a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (clear) to 4 (severe), evaluating intertriginous areas only.

Patient was noted to have intertriginous involvement at screening, but I-IGA was assessed as clear (0) at baseline and subsequent times. Because the I-IGA score was <2, the patient was not included in the I-IGA analysis population.

Primary Outcome

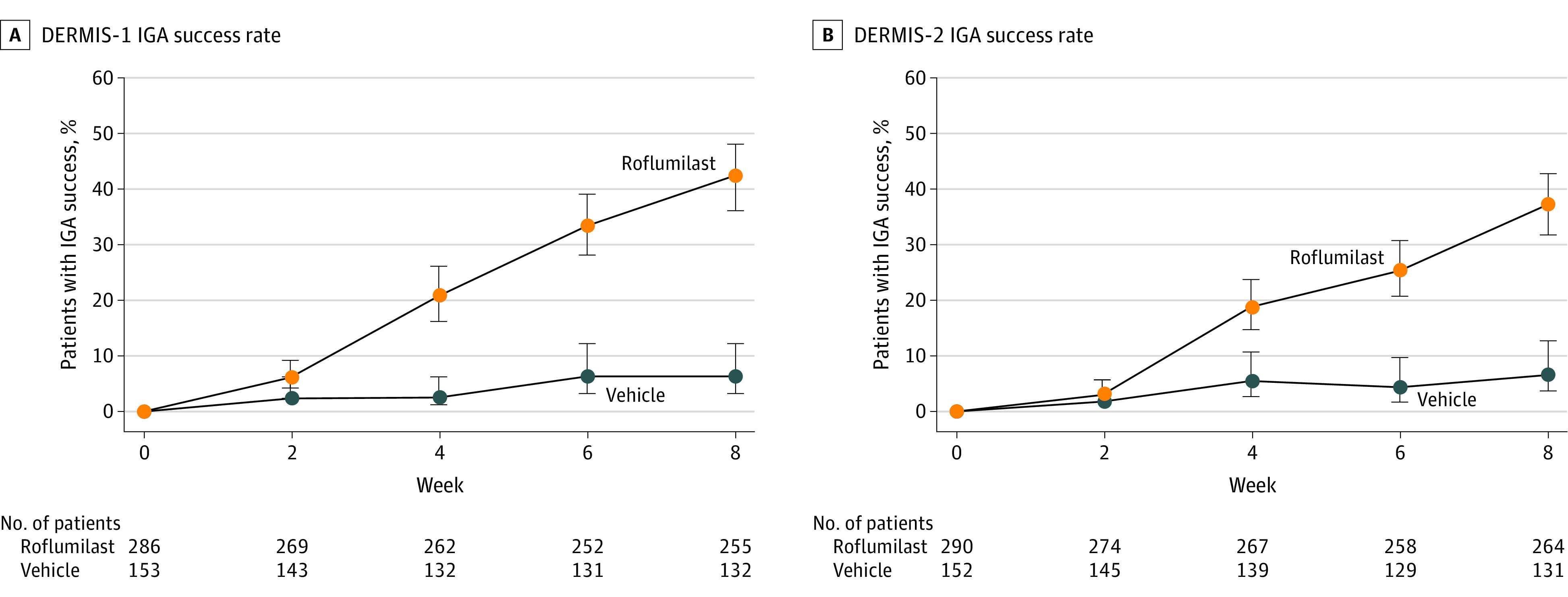

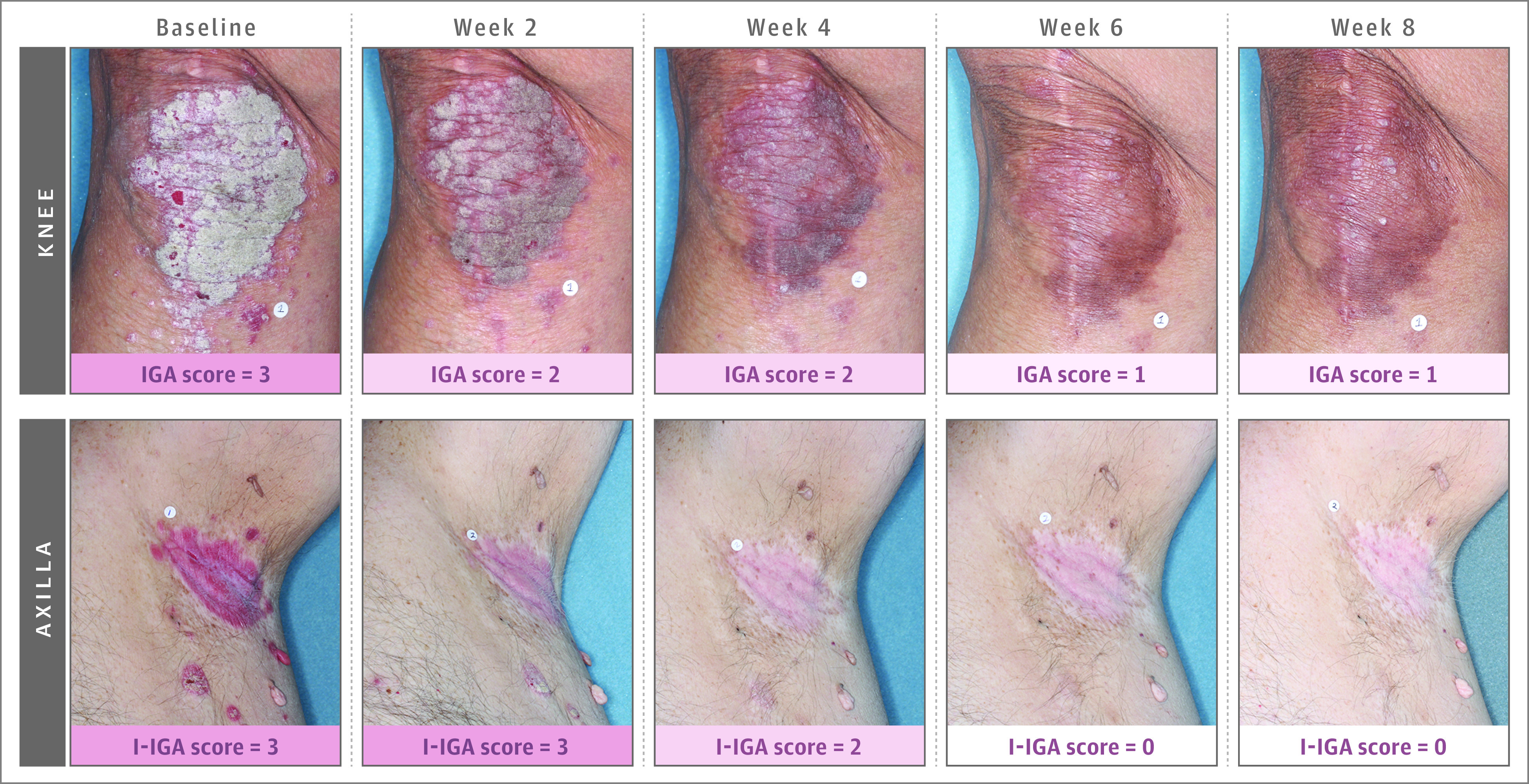

At 8-week follow-up in trial 1, 108 (42.4%) of the roflumilast-treated and 8 (6.1%) of the vehicle-treated patients achieved the primary outcome (difference, 39.6% [95% CI, 32.3%-46.9%]) (Figure 2). At 8-week follow-up in trial 2, 99 (37.5%) of the roflumilast-treated patients and 9 (6.9%) of the vehicle-treated patients achieved the primary outcome (difference, 28.8% [95% CI, 20.8%-36.9%]) (Figure 2). The number needed to treat was 2.8 (95% CI, 2.3-3.4) for trial 1 and 3.3 (95% CI, 2.6-4.3) for trial 2. Representative photos of patients treated with roflumilast cream, 0.3%, over time in DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2 are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2. Percentage of Patients Achieving IGA Success Over Time in DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2.

The primary end point for both studies was success on the Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) scale, defined as achievement of clear or almost clear status plus ≥2-grade improvement from baseline at 8 weeks.7 P < .001 for the difference at 8 weeks for both studies. Patients who completed the IGA at week 8 (±7 days) were considered completers. The percentage of patients who completed the 8-week study was 88.4% in DERMIS-1 and 89.4% in DERMIS-2. Observed percentages are presented. P values are based on analysis with imputation of missing data and stratification by pooled study sites, baseline IGA, and baseline intertriginous IGA. Whiskers represent 95% CIs.

Figure 3. Representative Photos of Patients Treated With Roflumilast Cream, 0.3%, Over Time in DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2.

IGA indicates Investigator Global Assessment; I-IGA, intertriginous IGA. IGA was measured based on whole-body involvement using a 5-point scale ranging from none (0) to severe (4). See eTable 1 in Supplement 5 for details of the scale. Images show an area of the whole-body measurement.

Secondary Outcomes

Among patients with I-IGA scores of 2 or higher at baseline, compared with vehicle, roflumilast significantly increased the percentage of patients achieving I-IGA success at week 8 (trial 1: 71.2% vs 13.8%; difference, 66.5% [95% CI, 47.1%-85.8%]; P < .001; trial 2: 68.1 vs 18.5%; difference, 51.6% [95% CI, 29.3%-73.8%]; P < .001) (Table 2). At 8-week follow-up, compared with vehicle, roflumilast significantly improved I-IGA clear status (trial 1: 63.5% vs 10.3%; difference, 58.1% [95% CI, 39.3%-76.9%); nominal P < .001; trial 2: 57.4% vs 7.4%; difference, 52.2% [95% CI, 32.1%-72.2%]; nominal P < .001) (Table 2).

Table 2. Secondary Efficacy End Points.

| Secondary efficacy end points | DERMIS-1 trial | DERMIS-2 trial | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roflumilast (n = 286) | Vehicle (n = 153) | Difference (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | Roflumilast (n = 290) | Vehicle (n = 152) | Difference (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

| I-IGA success at wk 8, % of patients (95% CI)a | 71.2 (58 to 82) | 13.8 (5 to 31) | 66.5 (47.1 to 85.8) | 17.94 (2.33-138.20) | <.001 | 68.1 (54 to 80) | 18.5 (8 to 37) | 51.6 (29.3 to 73.8) | 11.18 (2.33-53.68) | <.001 |

| No. | 52 | 29 | 47 | 27 | ||||||

| I-IGA status of clear at wk 8, % of patients (95% CI)b | 63.5 (50 to 75) | 10.3 (4 to 26) | 58.1 (39.3 to 76.9) | 29.36 (2.99-288.36) | <.001 | 57.4 (43 to 70) | 7.4 (2 to 23) | 52.2 (32.1 to 72.2) | 15.27 (3.10-75.35) | <.001 |

| No. | 52 | 29 | 47 | 27 | ||||||

| Achievement of 75% reduction in PASI score at wk 8, % of patients (95% CI)c | 41.6 (36 to 48) | 7.6 (4 to 13) | 36.1 (28.5 to 43.8) | 12.00 (5.15-27.93) | <.001 | 39.0 (33 to 45) | 5.3 (3 to 11) | 32.4 (24.9 to 39.8) | 10.42 (4.49-24.19) | <.001 |

| No. | 255 | 132 | 264 | 131 | ||||||

| WI-NRS success at wk 2, % of patients (95% CI)d | 34.9 (29 to 42) | 22.0 (15 to 31) | 10.8 (0.1 to 21.5) | 1.76 (0.98-3.19) | .12 | 41.9 (35 to 49) | 21.1 (14 to 30) | 18.9 (8.3 to 29.5) | 2.56 (1.43-4.58) | .003 |

| No. | 209 | 109 | 215 | 109 | ||||||

| WI-NRS success at wk 4, % of patients (95% CI)d | 50.2 (43 to 57) | 18.0 (12 to 27) | 30.7 (19.6 to 41.7) | 4.36 (2.31-8.26) | <.001 | 56.6 (50 to 63) | 21.9 (15 to 31) | 32.9 (22.3 to 43.4) | 4.93 (2.65-9.18) | <.001 |

| No. | 201 | 100 | 212 | 105 | ||||||

| WI-NRS success at wk 8, % of patients (95% CI)d | 67.5 (61 to 74) | 26.8 (19 to 36) | 42.6 (31.3 to 53.8) | 7.84 (3.85-15.94) | <.001 | 69.4 (63 to 75) | 35.6 (27 to 45) | 30.2 (18.2 to 42.2) | 3.59 (2.07-6.23) | <.001 |

| No. | 191 | 97 | 206 | 101 | ||||||

| Change from baseline PSD score at wk 4, least-squares mean (95% CI)e | −43.5 (−48.2 to −38.9) | −17.7 (−23.5 to −11.9) | −25.8 (−31.7 to −20.0) | <.001 | −42.7 (−47.7 to −37.7) | −16.7 (−22.8 to −10.6) | −26.0 (−31.9 to −20.0) | <.001 | ||

| No. | 261 | 130 | 262 | 135 | ||||||

| Change from baseline PSD score at wk 8, least-squares mean (95% CI)e | −50.1 (−55.0 to −45.1) | −19.2 (−25.3 to −13.0) | −30.9 (−37.2 to −24.6) | <.001 | −49.3 (−54.8 to −43.7) | −22.8 (−29.6 to −16.0) | −26.5 (−33.2 to −19.7) | <.001 | ||

| No. | 250 | 129 | 257 | 127 | ||||||

| Kaplan-Meier estimate of time to achievement of 50% reduction in PASI score, median (95% CI), dc | 31.0 (29.0 to 41.0) | 104.0 (85.0 to NE) | 3.867 (2.795-5.351)f | <.001 | 30.0 (29.0 to 42.0) | NE (71.0 to NE) | 4.207 (3.029-5.844)f | <.001 | ||

Abbreviations: I-IGA, intertriginous Investigator Global Assessment; NE, not estimable; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PSD, Psoriasis Symptom Diary; WI-NRS, Worst Itch Numeric Rating Scale.

I-IGA success indicates an I-IGA status of clear or almost clear plus ≥2-grade improvement from baseline assessed on a 5-point scale with scores ranging from 0 (clear) to 4 (severe). Conducted for patients with intertriginous area involvement of at least mild severity (I-IGA score ≥2), evaluating intertriginous areas only and not whole-body involvement.

Assessed on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (clear) to 4 (severe). Conducted for patients with intertriginous area involvement of at least mild severity (I-IGA score ≥2) at baseline, evaluating intertriginous areas only and not whole-body involvement.

The PASI combines assessment of the severity of lesions and the area affected into a single score ranging from 0 (no disease) to 72 (maximal disease).8

The WI-NRS is a single item to assess patient-reported severity of this symptom at its highest intensity during the previous 24-hour period on a scale from 0 (no itch) to 10 (worst imaginable itch).9 WI-NRS success indicates a ≥4-point reduction on the WI-NRS in patients with a WI-NRS score of ≥4 at baseline.

Patients used the PSD to determine the severity and impact of psoriasis-related signs and symptoms over the past 24 hours. Patients rated each variable in the 16-item assessment on a scale from 0 to 10, with the total score ranging from 0 to 160 and higher scores indicating greater severity or burden. The PSD end point was analyzed using analysis of covariance and performed using both multiple imputation and observed data. The values reported are the observed data, while the least-squares means and differences used multiple imputation for missing values.10 See eTable 3 in Supplement 5 for additional details.

Data are hazard ratios with 95% CIs.

At 8-week follow-up, compared with vehicle, roflumilast significantly increased the proportion of patients who achieved a 75% reduction from baseline in PASI score (trial 1: 41.6% vs 7.6%; difference, 36.1% [95% CI, 28.5%-43.8%]; P < .001; trial 2: 39.0% vs 5.3%; difference, 32.4% [95% CI, 24.9%-39.8%]; P < .001) (Table 2). Roflumilast significantly reduced Kaplan-Meier estimates of time to achievement of 50% reduction from baseline in PASI score compared with vehicle (trial 1: median, 31.0 [95% CI, 29.0-41.0] days vs 104.0 [95% CI lower bound, 85.0; upper bound not estimable] days; P < .001; trial 2: median, 30.0 [95% CI, 29.0-42.0] days for roflumilast; median not estimable [95% CI lower bound, 71.0 days; upper bound not estimable) for vehicle; P < .001) (Table 2).

Among patients with WI-NRS scores of 4 or higher at baseline, compared with vehicle, roflumilast significantly improved the proportion of patients achieving at least a 4-point WI-NRS reduction. At week 2 follow-up, percentages of patients with at least a 4-point WI-NRS reduction were 34.9% vs 22.0% for trial 1 (difference, 10.8% [95% CI, 0.1%-21.5%]; P = .12) and 41.9% vs 21.1% for trial 2 (difference, 18.9% [95% CI, 8.3%-29.5%]; P = .003) (Table 2). At week 4, percentages of patients with at least a 4-point WI-NRS reduction were 50.2% vs 18.0% for trial 1 (difference, 30.7% [95% CI, 19.6%-41.7%]; P < .001) and 56.6% vs 21.9% for trial 2 (difference, 32.9% [95% CI, 22.3%-43.4%]; P < .001) (Table 2). At week 8, percentages of patients with at least a 4-point WI-NRS reduction were 67.5% vs 26.8% for trial 1 (difference, 42.6% [95% CI, 31.3%-53.8%]; P < .001) and 69.4% vs 35.6% for trial 2 (difference, 30.2% [95% CI, 18.2%-42.2%]; P < .001) (Table 2).

Compared with vehicle, roflumilast significantly improved total PSD score at week 4 (trial 1: least-squares mean, −43.5 vs −17.7; least-squares mean difference, −25.8 [95% CI, −31.7 to −20.0]; P < .001; trial 2: least-squares mean, −42.7 vs −16.7; least-squares mean difference, −26.0 [95% CI, −31.9 to −20.0]; P < .001) (Table 2) and week 8 (trial 1: least-squares mean, −50.1 vs −19.2; least-squares mean difference, −30.9 [95% CI, −37.2 to −24.6]; P < .001; trial 2: least-squares mean, −49.3 vs −22.8; least-squares mean difference, −26.5 [95% CI, −33.2 to −19.7]; P < .001) (Table 2).

Other Prespecified Efficacy Outcomes

Compared with vehicle, roflumilast significantly improved rates of IGA success at week 4 (trial 1: 20.6% vs 2.3%; difference, 19.3% [95% CI, 13.5%-25.1%]; P < .001; trial 2: 19.1% vs 5.3%; difference, 13.5% [95% CI, 7.2%-19.9%]; P < .001) (eTable 2 in Supplement 5). Among patients with I-IGA scores of 2 or higher at baseline, compared with vehicle, roflumilast significantly improved attainment of I-IGA success at week 6 (trial 1: 56.6% vs 22.2%; difference, 41.0% [95% CI, 20.1%-61.8%]; P = .005; trial 2: 57.8% vs 13.8%; difference, 40.5 [95% CI, 18.7%-62.2%]; P = .004). Compared with vehicle, roflumilast increased the proportion of patients who reached an I-IGA status of clear at all postbaseline time points, including week 2 (trial 1: 20.7% vs 13.3%; difference, −5.2% [95% CI, −21.6% to 11.2%]; P = .95; trial 2: 30.6% vs 3.2%; difference, 27.3% [95% CI, 11.8%-42.8%]; P = .02), week 4 (trial 1: 28.8% vs 24.1%; difference, −1.2% [95% CI, −22.7% to 20.2%]; P = .42; trial 2: 37.5% vs 10.7%; difference, 27.9% [95% CI, 8.2%-47.6%]; P = .04), and week 6 (trial 1: 49.1% vs 14.8%; difference, 33.6% [95% CI, 12.0%-55.1%]; P = .03; trial 2: 42.2% vs 10.3%; difference, 31.0% [95% CI, 10.3%-51.7%]; P = .02) (eTable 2 in Supplement 5).

Compared with vehicle, roflumilast increased the proportions of patients with a 50% reduction from baseline in PASI score at week 2 (trial 1: difference, 21.0% [95% CI, 13.6%-28.4%]; P < .001; trial 2: difference, 21.8% [95% CI, 14.6%-29.0%]; P < .001), week 4 (trial 1: difference, 36.4% [95% CI, 27.5%-45.2%]; P < .001; trial 2: difference, 33.9% [95% CI, 25.0%-42.7%]; P < .001), week 6 (trial 1: difference, 47.5% [95% CI, 38.5%-56.5%]; P < .001; trial 2: difference, 43.1% [95% CI, 34.1%-52.1%]; P < .001), and week 8 (trial 1: difference, 58.1% [95% CI, 39.3%-76.9%]; P < .001; trial 2: difference, 52.2% [95% CI, 32.1%-72.2%]; P < .001). A greater percentage of patients treated with roflumilast than vehicle achieved a 75% reduction from baseline in PASI score at week 4 (trial 1: P < .001; trial 2: P < .002) and week 6 (P < .001 for both trials) (eTable 2 in Supplement 5), and at week 2 in trial 1 (nominal P = .008). A greater percentage of roflumilast-treated patients achieved a 90% reduction from baseline in PASI score at week 8 than vehicle-treated patients (trial 1: 22.4% vs 2.3%; nominal P < .001; trial 2: 17.0% vs 2.3%; nominal P < .001) (eTable 2 in Supplement 5); differences between treatments occurred by week 4 (trial 1: P = .02; trial 2: P = .007). Similarly, more roflumilast-treated patients than vehicle-treated patients achieved a 100% reduction from baseline in PASI score at week 6 (trial 1: P = .004; trial 2: P = .005) and week 8 (P < .001 for both trials) (eTable 2 in Supplement 5).

Of the 4 patients aged 2 to 11 years who participated in either trial, 1 (33.3%) of the 3 roflumilast-treated patients achieved IGA success at week 8; the 1 vehicle-treated patient did not achieve IGA success at week 8. Of the 14 patients aged 12 to 17 years who participated in either trial, 2 (25.0%) of the 8 roflumilast-treated and 1 (16.7%) of the 6 vehicle-treated patients achieved IGA success at week 8. Of the patients aged 18 to 65 years who participated in either trial, 175 (39.7%) of the 441 roflumilast-treated patients and 15 (6.7%) of the 225 vehicle-treated patients achieved IGA success at week 8. Of the patients older than 65 years who participated in either trial, 29 (43.3%) of the 67 roflumilast-treated patients and 1 (3.2%) of the 31 vehicle-treated patients achieved IGA success at week 8.

Adverse Events

In trial 1, TEAEs occurred in 25.2% of patients treated with roflumilast compared with 23.5% in patients treated with vehicle. In trial 2, TEAEs occurred in 25.9% of patients treated with roflumilast compared with 18.4% of those treated with vehicle (Table 3). In trial 1, 2 patients (0.7%) in the roflumilast group experienced serious adverse events compared with 1 (0.7%) in the vehicle group. In trial 2, 0 patients in the roflumilast group experienced serious adverse events compared with 1 (0.7%) in the vehicle group (Table 3). Rates of study drug discontinuation were 1.7% for roflumilast and 1.3% for vehicle in trial 1 and 0.3% for roflumilast and 1.3% for vehicle in trial 2. Application site pain was reported infrequently (trial 1: 2 [0.7%] in the roflumilast group and 1 [0.7%] in the vehicle group; trial 2: 4 [1.4%] in the roflumilast group and 0 in the vehicle group). No other application site TEAE was reported in more than 2 patients in either study.

Table 3. Adverse Events.

| Adverse events | No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DERMIS-1 trial | DERMIS-2 trial | |||

| Roflumilast (n = 286) | Vehicle (n = 153) | Roflumilast (n = 290) | Vehicle (n = 152) | |

| Patients with any treatment-emergent adverse eventa | 72 (25.2) | 36 (23.5) | 75 (25.9) | 28 (18.4) |

| Patients with any treatment-related treatment-emergent adverse eventb | 7 (2.4) | 3 (2.0) | 16 (5.5) | 8 (5.3) |

| Patients with any serious adverse eventc | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 1 (0.7) |

| Patients who discontinued study due to adverse event | 5 (1.7) | 2 (1.3) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (1.3) |

| Most common treatment-emergent adverse event (≥2% in any treatment group) | ||||

| Diarrhea | 10 (3.5) | 0 | 8 (2.8) | 0 |

| Headache | 3 (1.0) | 2 (1.3) | 11 (3.8) | 1 (0.7) |

| Hypertensiond | 5 (1.7) | 6 (3.9) | 4 (1.4) | 0 |

| Nasopharyngitis | 5 (1.7) | 3 (2.0) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.7) |

| Psoriasise | 0 | 3 (2.0) | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

A treatment-emergent adverse event is defined as an adverse event that emerges during treatment, having been absent pretreatment, or that worsens relative to the pretreatment state.

A treatment-related treatment-emergent adverse event was assessed by the principal investigator for each treatment-emergent adverse event. Adverse events with a relationship of possibly, probably, likely, or missing were considered treatment related.

A serious adverse event was any adverse event that, in the view of either the investigator or sponsor, resulted in death, a life-threatening adverse event, inpatient hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization, persistent or significant incapacity or substantial disruption of the ability to conduct normal life functions, or a congenital anomaly/birth defect. All serious adverse events were considered not related to study drug. Serious adverse events were concussion (DERMIS-1, roflumilast group), foot fracture (DERMIS-1, roflumilast group), deformity thorax (DERMIS-1, roflumilast group), pneumothorax (DERMIS-1, roflumilast group), plasma cell myeloma (DERMIS-1, vehicle group), and cervical radiculopathy (DERMIS-2, vehicle group).

Hypertension included synonymous terms (eg, blood pressure increased).

Progression of psoriasis that was out of proportion to the natural history of psoriasis.

Topical administration of roflumilast was associated with low rates of adverse effects typical of oral PDE4 inhibition, such as diarrhea. Of the 18 patients treated with roflumilast in trials 1 and 2 who reported diarrhea, 17 had mild cases and the remaining case was moderate in severity. Most patients reported cases within the first 2 weeks of treatment that resolved with continued dosing. No patients discontinued or interrupted treatment due to diarrhea.

For investigator-rated local tolerability, 98.8% and 98.6% of roflumilast-treated patients and 97.7% and 98.4% of vehicle-treated patients had no signs of irritation at weeks 4 and 8, respectively. Additionally, 99.3% and 98.8% of patients reported no or mild sensation after applying roflumilast cream at week 4 and week 8, respectively, which was consistent with vehicle cream (98.8% and 98.7% at week 4 and week 8, respectively).

Discussion

Among patients with chronic plaque psoriasis, roflumilast cream, 0.3%, compared with vehicle cream, improved IGA success at 8-week follow-up. Roflumilast cream also significantly increased the percentage of patients achieving I-IGA success and an I-IGA status of clear at week 8 among patients with intertriginous involvement. Among patients with WI-NRS scores of at least 4 at baseline, roflumilast cream significantly improved the percentage of patients with clinically meaningful improvement. Roflumilast cream also significantly increased the proportion of patients who achieved a 75% reduction from baseline in PASI score at week 8 and reduced Kaplan-Meier estimates of time to achievement of 50% reduction from baseline in PASI score. In the current randomized clinical trials, few stinging, burning, or application site reactions were reported with either roflumilast or vehicle, including among the subpopulation who used roflumilast in intertriginous areas, consistent with prior studies of topical roflumilast in psoriasis and atopic dermatitis.2,4,12

Treating psoriasis in intertriginous areas can be difficult because the skin in intertriginous areas is thinner and more sensitive, provides greater drug absorption, and is prone to adverse effects associated with topical therapies.13,14,15 Intertriginous psoriasis may be resistant to topical medications, likely because of mechanical effects including friction.13,14,15 Results reported herein indicate that roflumilast may be an effective therapy for these difficult-to-treat areas.

Pruritus is a highly irritating symptom in patients with psoriasis16 and is associated with negative effects on quality of life.16,17 These results are consistent with phase 2b results, in which roflumilast significantly improved pruritus, as measured by a significant reduction in WI-NRS score (by week 2) compared with placebo, and significantly improved itch-related sleep loss and Dermatology Life Quality Index scores (by week 6).18 Roflumilast also significantly improved patient-reported signs and symptoms, as indicated by significantly greater PSD improvements. Rates of treatment-related TEAEs, serious adverse events, and TEAEs leading to discontinuation were generally similar to rates in patients treated with vehicle.4

The American Academy of Dermatology/National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines for plaque psoriasis state that most patients benefit from topical options.19 The first-line topical treatments include corticosteroids, vitamin D analogues, and retinoids (ie, tazarotene).19 However, topical corticosteroids have adverse effects with long-term use and limitations associated with facial or intertriginous application.19 Vitamin D analogues and retinoids may be used long-term but may cause irritation and have lower efficacy than topical corticosteroids, so they are commonly prescribed in combination with topical corticosteroids.19 In this trial, roflumilast was not compared with any active comparators. Therefore, its efficacy relative to current topical treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis is unknown.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the lack of an active comparator treatment group prevented comparing efficacy of topical roflumilast with other active treatments. Second, the trials did not evaluate efficacy before 2 weeks after start of treatment. Third, the trials did not assess the efficacy of roflumilast beyond 8-week follow-up.

Conclusions

Among patients with chronic plaque psoriasis, treatment with roflumilast cream, 0.3%, compared with vehicle cream resulted in better clinical status at 8 weeks. Further research is needed to assess efficacy compared with other active treatments and to assess longer-term efficacy and safety.

DERMIS-1 Trial Protocol

DERMIS-1 Statistical Analysis Plan

DERMIS-2 Trial Protocol

DERMIS-2 Statistical Analysis Plan

eTable 1. Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) Scale

eTable 2. Other Efficacy Endpoints

eTable 3. Summary of Psoriasis Symptoms Diary Total Scores

eFigure. Statistical Testing Hierarchy

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Dong C, Virtucio C, Zemska O, et al. Treatment of skin inflammation with benzoxaborole phosphodiesterase inhibitors: selectivity, cellular activity, and effect on cytokines associated with skin inflammation and skin architecture changes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;358(3):413-422. doi: 10.1124/jpet.116.232819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papp KA, Gooderham M, Droege M, et al. Roflumilast cream improves signs and symptoms of plaque psoriasis: results from a phase 1/2a randomized, controlled study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19(8):734-740. doi: 10.36849/JDD.2020.5370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daliresp (roflumilast). Prescribing information. AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP; 2020. Accessed September 14, 2021. https://den8dhaj6zs0e.cloudfront.net/50fd68b9-106b-4550-b5d0-12b045f8b184/704932ce-e104-4c6f-840a-575170971344/704932ce-e104-4c6f-840a-575170971344_viewable_rendition__v.pdf

- 4.Lebwohl MG, Papp KA, Stein Gold L, et al. ; ARQ-151 201 Study Investigators . Trial of roflumilast cream for chronic plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(3):229-239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2000073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stein Gold L, Gooderham MJ, Papp KA, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of roflumilast cream 0.3% in adult patients with chronic plaque psoriasis: results from a 52-week, phase 2b open-label study. Poster presented at: Innovations in Dermatology: Virtual Spring Conference 2021; March 16-20, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Langley RG, Feldman SR, Nyirady J, van de Kerkhof P, Papavassilis C. The 5-point Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) scale: a modified tool for evaluating plaque psoriasis severity in clinical trials. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26(1):23-31. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2013.865009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fredriksson T, Pettersson U. Severe psoriasis—oral therapy with a new retinoid. Dermatologica. 1978;157(4):238-244. doi: 10.1159/000250839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naegeli AN, Flood E, Tucker J, Devlen J, Edson-Heredia E. The Worst Itch Numeric Rating Scale for patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54(6):715-722. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strober BE, Nyirady J, Mallya UG, et al. Item-level psychometric properties for a new patient-reported Psoriasis Symptom Diary. Value Health. 2013;16(6):1014-1022. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimball AB, Naegeli AN, Edson-Heredia E, et al. Psychometric properties of the Itch Numeric Rating Scale in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(1):157-162. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gooderham MJ, Kircik LH, Zirwas M, et al. The safety and efficacy of roflumilast cream 0.15% and 0.05% in atopic dermatitis: phase 2 proof-of-concept study. Poster presented at: EADVIRTUAL, 29th Congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV); October 28–November 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dopytalska K, Sobolewski P, Błaszczak A, Szymańska E, Walecka I. Psoriasis in special localizations. Reumatologia. 2018;56(6):392-398. doi: 10.5114/reum.2018.80718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khosravi H, Siegel MP, Van Voorhees AS, Merola JF. Treatment of inverse/intertriginous psoriasis: updated guidelines from the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16(8):760-766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kivelevitch D, Frieder J, Watson I, Paek SY, Menter MA. Pharmacotherapeutic approaches for treating psoriasis in difficult-to-treat areas. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2018;19(6):561-575. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2018.1448788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elewski B, Alexis AF, Lebwohl M, et al. Itch: an under-recognized problem in psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(8):1465-1476. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Globe D, Bayliss MS, Harrison DJ. The impact of itch symptoms in psoriasis: results from physician interviews and patient focus groups. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:62. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stein Gold L, Alonso-Llamazares J, Draelos ZD, et al. Correlation of itch response to roflumilast cream with disease severity and patient-reported outcomes in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. Paper presented at: American Academy of Dermatology Virtual Annual Meeting; April 23-25, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elmets CA, Korman NJ, Prater EF, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapy and alternative medicine modalities for psoriasis severity measures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(2):432-470. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

DERMIS-1 Trial Protocol

DERMIS-1 Statistical Analysis Plan

DERMIS-2 Trial Protocol

DERMIS-2 Statistical Analysis Plan

eTable 1. Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) Scale

eTable 2. Other Efficacy Endpoints

eTable 3. Summary of Psoriasis Symptoms Diary Total Scores

eFigure. Statistical Testing Hierarchy

Data Sharing Statement