Abstract

Objective

Patient and family engagement (PE) in health service planning and improvement is widely advocated, yet little prior research offered guidance on how to optimise PE, particularly in hospitals. This study aimed to engage stakeholders in generating evidence-informed consensus on recommendations to optimise PE.

Design

We transformed PE processes and resources from prior research into recommendations that populated an online Delphi survey.

Setting and participants

Panellists included 58 persons with PE experience including: 22 patient/family advisors and 36 others (PE managers, clinicians, executives and researchers) in round 1 (100%) and 55 in round 2 (95%).

Outcome measures

Ratings of importance on a seven-point Likert scale of 48 strategies organised in domains: engagement approaches, strategies to integrate diverse perspectives, facilitators, strategies to champion engagement and hospital capacity for engagement.

Results

Of 50 recommendations, 80% or more of panellists prioritised 32 recommendations (27 in round 1, 5 in round 2) across 5 domains: 5 engagement approaches, 4 strategies to identify and integrate diverse patient/family advisor perspectives, 9 strategies to enable meaningful engagement, 9 strategies by which hospitals can champion PE and 5 elements of hospital capacity considered essential for supporting PE. There was high congruence in rating between patient/family advisors and healthcare professionals for all but six recommendations that were highly rated by patient/family advisors but not by others: capturing diverse perspectives, including a critical volume of advisors on committees/teams, prospectively monitoring PE, advocating for government funding of PE, including PE in healthcare worker job descriptions and sharing PE strategies across hospitals.

Conclusions

Decision-makers (eg, health system policy-makers, hospitals executives and managers) can use these recommendations as a framework by which to plan and operationalise PE, or evaluate and improve PE in their own settings. Ongoing research is needed to monitor the uptake and impact of these recommendations on PE policy and practice.

Keywords: Quality in health care, Organisational development, Change management

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

Recommendations were evidence based, having been derived from prior research.

Recommendations were rated by 58 persons with lived experience of patient engagement (PE): 22 patient/family advisors and 36 PE managers, clinicians, executives, researchers.

We employed rigorous methods: large panel size enhanced reliability; two rounds of rating minimised respondent fatigue, which achieved a high response rate (100% round 1, 95% round 2); strong definition of consensus to yield high-priority recommendations (≥80% of panellists rated 6 or 7 on Likert scale to retain); and compliance with research and reporting criteria for Delphi studies to enhance rigour.

Panellists were volunteers so their views may differ from those of other patients, patient/family advisors or healthcare professionals.

The findings may not be relevant in countries outside of Canada with differing cultural and health system contexts.

Introduction

Hospitals provide inpatient, outpatient and emergency services, and account for the largest share of health spending in many countries.1 Research in many jurisdictions shows that the quality and safety of hospital care is inconsistent.2–5 Hence, hospitals continuously strive to improve the organisation and delivery of services. One approach gaining prominence worldwide is to engage patients or family/care partners (henceforth, patients) in planning, evaluating and improving health services for the benefit of all patients. In this context, patient engagement (PE) is defined as patients, families or their representatives, and health professionals working in active partnership to improve health services.6 While evidence is accumulating on engaging patients in research,7 and in their own health and healthcare,8 our prior scoping review identified only 10 studies of PE for healthcare planning and improvement specifically in hospitals, which are unique from other healthcare settings in size, staffing and service delivery.9 PE has been associated with a range of benefits such as enhanced governance and clinical processes, new or improved patient resources and efficient service delivery.10 Healthcare decision-makers, including policy-makers who fund hospitals, hospital managers who organise services and clinicians who directly engage patients, require knowledge of the conditions (eg, resources, processes) that optimise PE to inform resource allocation.

We surveyed managers at hospitals in Ontario, Canada to describe PE. While infrastructure and processes varied across 91 participating hospitals, we identified hospitals of all types (<100 beds, 100+ beds and teaching) with high capacity for PE, distinguished by PE activity organisation wide across multiple departments, and use of largely collaborative rather than consultative PE approaches.11 We interviewed patient/family advisors, PE managers, clinicians and executives at hospitals with high PE capacity who identified infrastructure and processes needed to support PE. Participants also reported a range of beneficial impacts including improved PE capacity (new PE processes were developed and spread across departments, those involved became more adept and engaged) and clinical care at multiple levels: hospital (new/improved policies, strategic plans, facilities, programmes), clinician (greater efficiency in service delivery, enhanced job satisfaction, improved patient–staff communication) and patient (educational material, discharge processes and information, improved hospital experience, decreased wait times, reduced falls, lower readmission rates).12 13

Given the widespread interest in PE and demonstrated benefits, and lack of insight on how to optimise PE in hospitals,9 10 the overall aim of this study was to build on our prior research,11–13 and issue guidance for optimising PE in hospital planning and improvement. The specific objective was to engage stakeholders in establishing consensus on priority recommendations derived from evidence generated by our prior research. The output, resources and processes that enable hospital PE, could be used by decision-makers to plan, support or improve hospital PE.

Methods

Approach

We employed the Delphi technique, a widely used method for generating consensus on strategies, recommendations or quality measures.14–16 This technique is based on one or more rounds of survey in which expert panellists independently rate recommendations until a degree of consensus is achieved. We complied with the Conducting and Reporting of Delphi Studies criteria to enhance rigour.17

Sampling and recruitment

A review of Delphi studies showed that the median number of panellists was 17 (range 3–418).18 Other research found that reliability of Delphi rating increased with panel size.19 To ensure that multiple perspectives were considered, we aimed to include a minimum of 20 persons with experience as patient/family advisors and 20 professionals of diverse specialties with knowledge or experience of PE. We recruited Canadian patient/family advisors aged 18+ and health professionals (PE managers, clinicians, executives) affiliated with 91 Ontario hospitals that responded to our prior survey and agreed to be contacted for future studies,11 and identified other Canadian patient/family advisors, clinicians and researchers with experience in PE on publicly available websites.

Survey development

We derived recommendations to be rated by panellists from aforementioned interviews with patient/family advisors, PE managers and clinicians or executives affiliated with hospitals with high PE capacity.12 13 NNA and ARG extracted data on all unique enablers and barriers of PE, or suggested strategies for promoting or supporting PE and worded those as recommendations. We organised the 48 recommendations by domains that inductively emerged from our prior research: engagement approaches, strategies to identify and integrate diverse perspectives, strategies to enable PE/family engagement, strategies to champion PE/family engagement and hospital capacity for PE/family engagement.12 13 The research team reviewed recommendations for clarity and relevance().

Data collection and analysis

We transformed recommendations into a round 1 online survey using REDCap. We asked panellists to rate each recommendation on a 7-point Likert scale (1 strongly disagree, 7 strongly agree), comment on the relevance or wording of each recommendation if desired, and suggest additional recommendations not included in the survey. We emailed instructions and survey link to panellists on 19 May 2021, with reminders at 1 and 2 weeks. Based on results, we developed a round 1 summary report that included Likert scale response frequencies and comments for each recommendation, which we organised by those retained (rated by at least 80% of panellists as 6 or 7), discarded (rated by at least 80% of panellists as 1 or 2) or no consensus (all others), along with newly suggested recommendations. Standard Delphi protocol suggests that two rounds of rating with agreement by at least two-thirds of panellists to either retain or discard items will prevent respondent fatigue and drop-out.17 18 We conducted two rounds of rating; however, to yield unequivocal recommendations, we considered 80% to indicate consensus. On 18 June 2021, we emailed panellists the round 1 summary report with a link to the round 2 survey, formatted similarly to the round 1 survey, to prompt rating of recommendations that did not achieve consensus for inclusion or exclusion in round 1. We emailed a reminder at 1, 2 and 3 weeks. We analysed and summarised round 2 responses as described for round 1.

Patient and public involvement

Three patient and family advisors were involved in planning the multipart study that informed this final component of that study. Patient and family advisors were included as expert panellists in this study to rate the importance of recommendations for resources and processes that optimise hospital PE.

Results

Panelists

Of 109 persons invited to participate, 58 agreed (table 1). The response rate for round 1 was 100.0%, and for round 2, 94.8% (55/58). Round 2 non-responders included one PE researcher, one executive and one clinician from a teaching hospital.

Table 1.

Participants

| Participant type | Hospital type | Others | Subtotal | ||

| <100 beds | 100+ beds | Teaching | |||

| Patient/family advisors | 3 | 10 | 5 | 4 | 22 |

| PE managers | 4 | 9 | 5 | – | 18 |

| Clinicians | 3 | 4 | 2 | – | 9 |

| Executives | – | – | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Researchers | – | – | – | 5 | 5 |

| Subtotal | 10 | 23 | 13 | 12 | 58 |

PE, patient engagement.

Delphi results

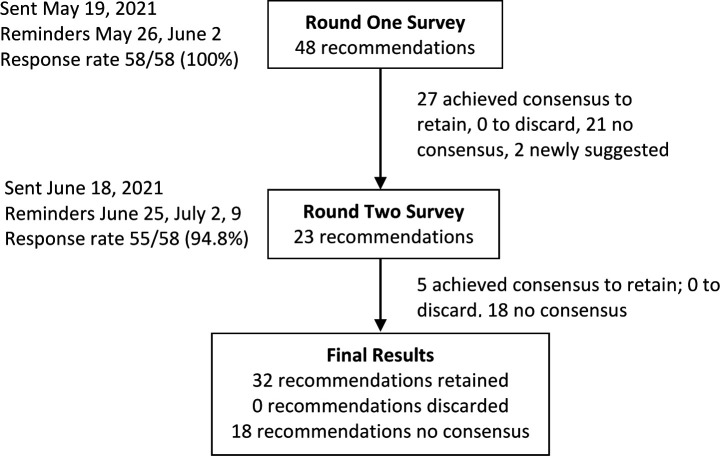

Online supplemental file 2 details the recommendations retained, discarded or that achieved no consensus in rounds 1 and 2. Figure 1 summarises the number of recommendations retained, discarded or with no consensus in each round. Of the 50 recommendations considered, 32 achieved consensus to retain: 27 in round 1 and 5 in round 2.

Figure 1.

Delphi summary. Flow diagram depicting each stage of the Delphi process.

bmjopen-2022-061271supp002.pdf (126.7KB, pdf)

Prioritised recommendations

Table 2 lists 32 retained recommendations including: 5 engagement approaches, 4 strategies to identify and integrate diverse patient/family advisor perspectives, 9 strategies to enable meaningful engagement, 9 strategies by which hospitals can champion PE, and 5 elements of hospital capacity considered essential for supporting PE. Three recommendations were retained by 100.0% of panellists: In advance of meetings or activities, hospitals should provide patient/family advisors with agendas, background information or briefing material to help them prepare and then actively participate (#15); hospitals should foster an organisation-wide culture of respect and support for PE/family engagement (#27); and Hospitals should share results or outcomes with involved patient/family advisors so that they are aware of how their input and decisions contributed to planning and improvement (#30). Table 2 identifies the 16 (50.0%) recommendations scored by 90.0% or more of panellists to retain, and the 16 (50.0%) scored by 80.0%–89.9% of panellists to retain.

Table 2.

Recommendations that achieved consensus to retain

| Domain | Recommendation (% panellist who rated Likert scale 6 or 7 to retain) |

| Engagement approaches 5/6 retained |

Patient/family advisors with appropriate skills should be engaged in decisions for hospital activities whenever possible, including governance, strategy planning and designing, developing, evaluating or improving facilities, programmes, healthcare services, care practices, quality and safety or resources/materials (86.2) |

| Hospitals should establish and maintain at least one Patient and Family Advisory Committee (87.9) | |

| In addition to one or more Patient and Family Advisory Committee’s, hospitals should engage patient/family advisors using multiple forms of engagement (eg, standing committees, project teams) (96.5) | |

| Patient and family engagement should take place in-person whenever possible to build rapport, but virtual options and technology should be offered to enhance convenience and connectivity and suit diverse preferences (**please rate this for a non-pandemic context) (83.3) | |

| Hospitals should employ a range of approaches to engage patient/family advisors including collaboration (eg, member of project teams or committees), consultation (eg, surveys, interviews, focus groups) or blended approaches (eg, collaboration and consultation approaches for the same initiative) (93.1) | |

| Strategies to identify and integrate diverse perspectives 4/5 retained |

Hospitals should build patient/family engagement programmes that welcome persons with diverse experiences, characteristics, abilities and resources representative of the communities they serve, and do so in a culturally safe manner or setting (98.3) |

| Hospitals should recruit patient/family advisors using a range of strategies (eg, social media, email, newspaper ads, word of mouth, through community organisations) and in languages or settings tailored to the community they serve to achieve diversity (91.2) | |

| In prioritising what benefits many, hospitals should also use a health equity lens to ensure that they are improving quality of care for at risk populations in their community (98.2) | |

| Hospitals should ensure that there is ongoing recruitment and onboarding of new patient and family advisors to enhance diversity and supplement the contributions of long-standing experienced patient/family advisors (96.6) | |

| Strategies to enable patient/family engagement 9/14 retained |

Once recruited, hospitals should provide patient/family advisors with ongoing support and education about roles and responsibilities, organisational culture and strategic priorities to prepare them for engagement, possibly through mentorship by existing experienced patient/family advisors (96.5) |

| In advance of deployment, hospitals should orient patient/family advisors to the background, purpose, and goals of a specific committee or project (eg, share documents, meet with project or committee leader) (96.6) | |

| In advance of meetings or activities, hospitals should provide patient/family advisors with agendas, background information, briefing material and the name of a liaison who can answer questions to help them prepare and then actively participate (100.0) | |

| Hospitals should train project leaders, committee chairs, healthcare workers and staff on how to foster a team environment, and effectively engage with and support patient/family advisors (89.7) | |

| Hospitals should involve patient/family advisors in reviewing and delivering training to existing healthcare workers and staff, and orienting new healthcare workers/staff to patient engagement (84.5) | |

| Hospitals should engage patient/family advisors early and throughout planning or improvement activities (94.8) | |

| At the outset of new committees or projects, the chair should explicitly establish roles and responsibilities collaboratively with and for all involved including patient/family advisors and healthcare workers, and prospectively revisit roles as projects evolve (89.3) | |

| Hospital healthcare workers and staff should demonstrate that they value patient/family advisor input and decisions by meaningfully engaging with patient/family advisors, basing decisions on their perspectives and telling patient/family advisors that they are valued (89.1) | |

| Hospitals should routinely check with patient/family advisors to confirm that interim or near-to-final decisions or outputs accurately captured their perspectives and explain why, if any, were not captured (87.7) | |

| Strategies to champion patient/family engagement 9/11 retained |

Hospitals should convey an organisational commitment to patient/family engagement by acknowledging it in their hospital values statement and strategic plan, and continuously update values/strategic plan as patient/family engagement evolves (94.6) |

| Hospitals should foster an organisation-wide culture of respect and support for patient/family engagement (100.0) | |

| To establish a philosophical commitment, hospitals should promote the view that patient/family advisors bring diverse expertise, skills and perspectives, which should be valued equally to those of healthcare workers (82.8) | |

| Senior administrative and clinical leaders should model patient/family engagement (98.1) | |

| Hospitals should share results or outcomes with involved patient/family advisors so that they are aware of how their input and decisions contributed to planning and improvement (100.0) | |

| The hospital [Chief Executive Officer] and board members should visibly endorse patient/family engagement by promoting it throughout the hospital to all staff and patients (eg, in waiting rooms) to create awareness of how patient/family advisors worked with healthcare workers/staff on planning and improvement (87.5) | |

| Hospitals should share patient/family engagement opportunities, activities, outputs and impacts with the broader community through various platforms as a means of patient/family advisor recruitment and to create awareness about how the hospital is addressing their needs (93.1) | |

| Chairs of standing committees or project teams should assess acceptability in advance, and then routinely consult with patient/family advisors throughout meetings to ensure they understand acronyms, medical terms or issues under discussion, ask if they have any questions, or wanted to articulate ideas or feedback, and adjust pace as necessary (80.8) | |

| Hospitals should include at least one patient/family advisor on the Board or Committees of the Board as voting members (80.0) | |

| Hospital capacity for patient/family engagement 5/12 retained |

Hospitals should allocate dedicated operational funding to nurture and maintain patient/family engagement including one or more Patient and Family Advisory Committee’s and other engagement activities (84.2) |

| Hospitals should encourage healthcare workers to participate in patient/family engagement, and recognise their efforts (eg, in annual performance reviews) (80.0) | |

| Hospitals should ideally employ a dedicated patient engagement manager to promote and support patient/family engagement, or include this responsibility in an existing closely-related portfolio (eg, patient relations manager, human resources personnel) (88.7) | |

| Hospitals should employ dedicated patient engagement staff who are driven by person-centred values and possess skills in reflective listening, compassionate communication, and project coordination and facilitation (84.5) | |

| Hospitals should regularly evaluate patient/family engagement practices and make improvements based on patient/family advisor, healthcare worker and staff feedback, and reflection on what worked and what did not work (93.0) |

Agreement and differences

Ratings for the 32 retained recommendations were similar between patient/family advisor panellists and others (PE managers, clinicians, executives and researchers). Of the remaining 18 recommendations that failed to achieve consensus, patient/family advisors and others similarly rated 12 recommendations. Table 3 shows the six recommendations where at least 80% of patient/family advisors scored to retain and others did not along with select comments to illustrate diverging views. For example, the two groups differed in rating of recommendation #9: Hospitals should seek to identify and address issues that are priorities for, and of benefit to all patients and families they serve rather than focusing only on issues common to the majority. Patient/family advisor panellists raised concerns about equity and diversity, and thought that ignoring issues not faced by the majority of patients may lead to a worsening situation that does impact the majority. In contrast, other panellists said that it was not always possible to address all issues due to lack of resources, focus on hospital priorities and government mandates. The five additional recommendations prioritised by patient/family advisors but not by other panellists included: Hospitals should include at least one and preferably more patient/family advisors on any committee or project team (#22); Patient and Family Advisory Committees should routinely review interim progress, decisions or outputs of standing committees or project teams to ensure that decisions reflect patient/family advisor perspectives (#24); Hospitals should appeal to government, which advocates for PE/family engagement, for dedicated funding to support PE/family engagement (#38); Hospitals should include PE/family engagement activities into appropriate healthcare worker and staff job descriptions as part of the human resource commitment to person-centred care (#42); and hospitals should encourage, support and facilitate collaboration with Patient and Family Advisory Committees from other hospitals and patient family advisory bodies to foster a community of learning (#50).

Table 3.

Recommendations with no consensus where rating differed between panellists

| Recommendation (as worded in round 2) |

Rating (% who rated to retain) |

Exemplar comments | |

| Round 1 | Round 2 | ||

| (9) Hospitals should seek to identify and address issues that are priorities for, and of benefit to all patients and families they serve rather than focusing only on issues common to the majority | Patients 54.5 Others 60.0 |

Patients 86.4 Others 64.5 |

Patients

Others

|

| (22) Hospitals should include at least one and preferably more patient/family advisors on any committee or project team | Patients 72.7 Others 38.9 |

Patients 90.9 Others 59.4 |

Patients

Others

|

| (24) Patient and Family Advisory Committees (PFAC) should routinely review interim progress, decisions or outputs of standing committees or project teams to ensure that decisions reflect patient/family advisor perspectives | Patients 76.2 Others 72.2 |

Patients 86.4 Others 66.7 |

Patients

Others

|

| (38) Hospitals should appeal to government, which advocates for patient/family engagement, for dedicated funding to support patient/family engagement | Patients 81.8 Others 72.2 |

Patients 90.9 Others 69.7 |

Patients

Others

|

| (42) Hospitals should include patient/family engagement activities into appropriate healthcare worker and staff job descriptions as part of the Human Resource commitment to person-centred care | Patients 80.0 Others 75.0 |

Patients 81.9 Others 71.9 |

Patients

Others (comments supportive)

|

| (50) Hospitals should encourage, support and facilitate collaboration with PFAC from other hospitals and Patient Family Advisory Bodies to foster a community of learning | – | Patients 86.4 Others 60.6 |

Patients

Others

|

Discussion

Rating of 50 recommendations for resources or processes to support hospital-based PE by 58 panellists (22 patient/family advisors; 36 PE managers, clinicians, executives, researchers) in a two-round Delphi survey resulted in consensus by 80% or more on the importance of 32 recommendations across five domains: 5 engagement approaches, 4 strategies to identify and integrate diverse patient/family advisor perspectives, 9 strategies to enable meaningful engagement, 9 strategies by which hospitals can champion PE, and 5 elements of hospital capacity considered essential for supporting PE. Of the 32 recommendations, 16 (50.0%) were rated important by 90%+ of panellists (3 recommendations by 100.0%), and 16 (50.0%) by 80%–89.9% of panellists. There was high congruence in rating between patient/family advisors for all but six recommendations that did not achieve consensus.

Strengths of this study included: rating of recommendations by a panel comprised of patient/family advisors (who are themselves patients or family of patients) and interdisciplinary healthcare professionals; recommendations rated by panellists were derived from prior research involving patients, family and healthcare professionals, and thus evidence based12 13; the large panel size enhanced reliability; two rounds of rating minimised respondent fatigue, which achieved a high response rate in both rounds; and we used a strong definition of consensus to yield high-priority recommendations. We optimised rigour by complying with research and reporting criteria for Delphi studies.14–19 We must acknowledge limitations. Recommendations were derived from our own prior research,11–13 given that our prior review of PE for healthcare planning and improvement specifically in hospital settings had identified only 10 studies.9 However, that review included studies published before 2017, so an updated review may be warranted to identify recommendations that reflect international perspectives and compare those recommendations with the findings of this research. Panellists were volunteers so their views may be biased, particularly because about half of the originally invited panellists agreed to participate; however, we specifically recruited individuals for their expertise, and potential bias was off-set by review of evidence-based recommendations. Panellist views may differ from those of other patients, patient/family advisors or healthcare professionals. The findings may not be generalisable in countries outside of Canada with differing cultural and health system contexts.

As noted, research on PE has largely focused on engaging patients in research or in their own healthcare,7 8 with very little prior research on how to enable PE in hospital-based planning and improvement.9 10 A survey of clinicians from a university hospital in France reported only the types of activities in which patients were involved (eg, developing care pathways, and educational programmes for patients and healthcare professionals).20 A systematic review of 11 qualitative studies of patient involvement in quality improvement (unclear if any studies based in hospitals) revealed that a key barrier was limited power of patients to influence decision-making given little power over healthcare professionals.21 A survey of managers from 74 hospitals across 7 European countries found that few hospitals involved patients in quality improvement (eg, developing quality criteria, designing processes or being a member of quality committees or project teams).22 Our research goes beyond reporting the activities in which patients are engaged or barriers of engagement to describe processes and infrastructure essential to PE based on the views of patient/family advisors and healthcare professionals with lived experience of hospital PE.

A notable finding was the high degree of agreement between patient/family advisors and other panellists on priority recommendations. This likely reflects the fact that all panellists had considerable experience in PE, and largely represented hospitals with high PE capacity and activity. Both factors underscore the relevance and validity of the recommendations, which form a concrete framework that can be broadly applied: hospitals newly embarking on PE can use the framework to develop strategic and operational plans specific to PE, and hospitals that already implemented PE can use the framework to evaluate their own activities, identify areas needing improvement, and strengthen PE. One challenge may be the large number of recommendations that achieved consensus. Organisations with limited resources could employ a staggered approach, whereby the recommendations that achieved the highest consensus could be implemented first. These recommendations were generated by persons largely affiliated with hospitals having high PE capacity who self-reported numerous beneficial impacts on PE capacity, clinical care and patient outcomes.12 13 High PE capacity hospitals were characterised by PE activity organisation wide and use of largely collaborative rather than consultative PE approaches, referring to co-production.11 Co-production refers to users and professionals who are creating, designing, producing, delivering, assessing and evaluating the relationships and actions that contribute to the health of individuals and populations, which is fundamental to learning health systems.23 True co-production requires meaningful engagement or sharing of power between patients and health professionals, yet research suggests that engagement is often token due a variety of barriers.21 24 25 Therefore, ongoing research is needed to confirm the uptake of these recommendations, including their influence on policy at the health system or hospital level, and on various impacts in hospitals with both new and established PE.

In conclusion, while PE in health service planning and improvement is widely advocated, little prior research offered guidance on how to optimise PE, particularly in hospital settings. Through a series of studies, we identified resources and processes required for hospital-based PE,12 13 culminating in the current Delphi survey, in which 58 patient/family advisors, PE managers, clinicians, executives and researchers with experience and expertise in PE prioritised recommendations reflecting resources and processes to optimise PE. Decision-makers (eg, health system policy-makers, hospitals executives and managers) can use the resulting 32 recommendations as a framework by which to plan and operationalise PE, or evaluate and improve PE in their own settings.

bmjopen-2022-061271supp001.pdf (84KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @wwodchis

Contributors: ARG, RB, LM, KS, RU and WPW conceived and planned the study. ARG acquired funding, supervised NNA, and is guarantor for the article. NNA and ARG coordinated the study, and collected and analysed data. All authors reviewed and interpreted data; and contributed to, reviewed and approved this final version.

Funding: This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant number not applicable).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The University Health Network Research Ethics Board approved this study (REB #18-5307). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Global spending on health: a world in transition. Geneva, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwendimann R, Blatter C, Dhaini S, et al. The occurrence, types, consequences and preventability of in-hospital adverse events – a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:521. 10.1186/s12913-018-3335-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kemp KA, Santana MJ, Southern DA, et al. Association of inpatient hospital experience with patient safety indicators: a cross-sectional, Canadian study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e0111242. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aiken LH, Sermeus W, Van den Heede K, et al. Patient safety, satisfaction, and quality of hospital care: cross sectional surveys of nurses and patients in 12 countries in Europe and the United States. BMJ 2012;344:e1717. 10.1136/bmj.e1717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Josée Davidson M, Lacroix J, McMartin S, et al. Patient experiences in Canadian hospitals. Healthcare Q 2019;22:12–14. 10.12927/hcq.2019.26024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, et al. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff 2013;32:223–31. 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Elraiyah T, et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:89. 10.1186/1472-6963-14-89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodridge D, McDonald M, New L, et al. Building patient capacity to participate in care during hospitalisation: a scoping review. BMJ Open 2019;9:e026551. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liang L, Cako A, Urquhart R, et al. Patient engagement in hospital health service planning and improvement: a scoping review. BMJ Open 2018;8:e018263. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bombard Y, Baker GR, Orlando E, et al. Engaging patients to improve quality of care: a systematic review. Implementation Sci 2018;13:98. 10.1186/s13012-018-0784-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gagliardi AR, Martinez JPD, Baker GR, et al. Hospital capacity for patient engagement in planning and improving health services: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Serv Res 2021;21:179. 10.1186/s12913-021-06174-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson NN, Baker GR, Moody L, et al. Approaches to optimize patient and family engagement in hospital planning and improvement: qualitative interviews. Health Expect 2021;24:967–77. 10.1111/hex.13239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson NN, Baker GR, Moody L, et al. Organizational capacity for patient and family engagement in hospital planning and improvement: interviews with patient/family advisors, managers and clinicians. Int J Qual Health Care 2021;33:mzab147. 10.1093/intqhc/mzab147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ 1995;311:376–80. 10.1136/bmj.311.7001.376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, et al. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PLoS One 2011;6:e20476–9. 10.1371/journal.pone.0020476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stelfox HT, Straus SE. Measuring quality of care: considering conceptual approaches to quality indicator development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:1328–37. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jünger S, Payne SA, Brine J, et al. Guidance on conducting and reporting Delphi studies (CREDES) in palliative care: recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat Med 2017;31:684–706. 10.1177/0269216317690685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vernon W. The Delphi technique: a review. Int J Ther Rehabil 2009;16:69–76. 10.12968/ijtr.2009.16.2.38892 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dagenais F. The reliability and convergence of the Delphi technique. J Gen Psychol 1978;98:307–8. 10.1080/00221309.1978.9920886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malloggi L, Leclère B, Le Glatin C, et al. Patient involvement in healthcare workers’ practices: how does it operate? A mixed-methods study in a French university hospital. BMC Health Serv Res 2020;20:391. 10.1186/s12913-020-05271-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Deventer C, McInerny P, Cooke R. Patients’ involvement in improvement initiatives: a qualitative systematic review. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep 2015;13:232–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Groene O, Sunol R, Klazinga NS, et al. Involvement of patients or their representatives in quality management functions in Eu hospitals: implementation and impact on patient-centred care strategies. Int J Qual Health Care 2014;26:81–91. 10.1093/intqhc/mzu022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gremyr A, Andersson Gäre B, Thor J, et al. The role of co-production in learning health systems. Int J Qual Health Care 2021;33:ii26–32. 10.1093/intqhc/mzab072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson KE, Mroz TM, Abraham M, et al. Promoting patient and family partnerships in ambulatory care improvement: a narrative review and focus group findings. Adv Ther 2016;33:1417–39. 10.1007/s12325-016-0364-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ocloo J, Garfield S, Franklin BD, et al. Exploring the theory, barriers and enablers for patient and public involvement across health, social care and patient safety: a systematic review of reviews. Health Res Policy Syst 2021;19:8. 10.1186/s12961-020-00644-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-061271supp002.pdf (126.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-061271supp001.pdf (84KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.