Abstract

Objective

This article aims to analyse the conditions under which health mediation for healthcare use is successful and feasible for underserved populations.

Method

We conducted a scoping review on the conditions for effective health mediation according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews standards. We searched for articles in the following databases: PubMed, PsychINFO, Scopus and Cairn published between 1 January 2015 and 18 December 2020. We selected the articles concerning health mediation interventions or similar, implemented in high-income countries and conducted among underserved populations, along with articles that questioned their effectiveness conditions. We created a two-dimensional analysis grid of the data collected: a descriptive dimension of the intervention and an analytical dimension of the conditions for the success and feasability of health mediation.

Results

22 articles were selected and analysed. The scoping review underlines many health mediation characteristics that articulate education and healthcare system navigation actions, along with mobilisation, engagement, and collaboration of local actors among themselves and with the populations. The conditions for the success and the feasability were grouped in a conceptual framework of health mediation.

Conclusion

The scoping review allows us to establish an initial framework for analysing the conditions for the success and the feasability of health mediation and to question the consistency of the health mediation approach regarding cross-cutting tensions and occasionally divergent logic.

Keywords: Quality in health care, PUBLIC HEALTH, STATISTICS & RESEARCH METHODS

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

We conducted a scoping review, to clarify key concepts and characteristics of health mediation rarely analysed.

The review was conducted by using two complementary approaches of health mediation: as an intervention or as a position in a professional function.

The review focused mainly on the structural conditions for the success and feasibility of health mediation for improving healthcare use for undeserved population.

The polysemy of the term ‘mediation’ and the variety of different terms used to describe health mediation make it difficult to globally assess.

The effectiveness of health mediation is rarely really demonstrated.

Introduction

Underserved populations include very heterogeneous populations.1 2 They are represented by all populations underserved by the healthcare system because of their living conditions, in particular, about material conditions and their socioeconomic precariousness (housing, employment, education, income), administrative precariousness (access to rights and administrative status, health coverage), their geographical mobility, or their psychosocial characteristics (integration and social support, history of the healthcare system use) and, on the other hand, to the inability of the system to organise and adapt to reach and support them.3 Underserved populations face specific systemic barriers, considered as structural factors: strong competitiveness with basic needs (ie, food insecurity, housing instability4 5), discrimination,6 insecurity,2 language barriers and difficulties in accessing healthcare interpreters.7 At the individual level, underserved people have social representations (ie, body, health, care perceptions) different from those dominant.8 This leads to a lowered benchmark for good health and underestimating the severity of the disease,9 and tends to hinder formulating a request for care, healthcare use or quality care.10–12 These populations are, in a way, subject to a threefold penalty: more exposed to the disease, less receptive to prevention messages, and finally, less use of healthcare. Therefore, interventions promoting healthcare use by underserved populations must go beyond the sole issue of supply. They must promote the ability of services to adapt their organisations, to strengthen the abilities of people to make decisions favourable to their health and to support them in overcoming the obstacles encountered.12 Simultaneously, they must develop programmes of access to rights, housing and employment, and tackle discrimination and exclusion.

Health mediation is one such intervention.11 13 14 Health mediation corresponds to connection mediation. It differs from healthcare mediation, which focuses on resolving conflicts within healthcare system.14 The French National Authority for Health (Haute Autorité de Santé, HAS) defines it as a temporary process of ‘going towards’ populations, health and social professionals and institutions and ‘working with’ people in a logic of empowerment of individuals.10 According to HAS, the ‘going towards’ approach has two components: (1) physical movement, ‘outside the walls’, towards the places frequented by underserved populations on the one hand and towards health professionals or institutions on the other; (2) openness towards others, towards the person as a whole, without judgement, with respect. This definition highlights the articulation between two functions: facilitating access to rights, prevention and care; and raising healthcare workers’ awareness about the access difficulties.10 15 Finally, mediation involves third-party mediators, generating connections and participating in a change in representations and practices between healthcare workers and the population. This third party must enable the transformation of healthcare system as an element of socialisation.16 Characterising health mediation remains a difficult task because of its multifaceted nature, particularly in high-income countries (patient navigator, health mediators, relay individuals, etc). Moreover, the evaluation of health mediation provides very different results from one context to another, from one population to another. Apart from pioneering militant studies,17–19 no study has conclusively estimated its effectiveness and conditions of effectiveness.

This article aims to analyse the conditions under which health mediation for healthcare use is successful (ie, effective from authors’ point of view) and feasible when applied to underserved populations and those exposed to numerous vulnerabilities, such as people living in precarious habitats, travellers, migrants and homeless people.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review,20 relevant when information on a given topic is not comprehensively examined, complex or diverse. It is thus particularly suitable for our subject as it allows (1) the identification of existing types of evidence in the field, (2) the clarification of key concepts or definitions, (3) the identification of key characteristics related to our subject and (4) the identification of knowledge gaps.21 We conducted this review according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews standards: checklist and explanation22 (see online supplemental appendix 1).

bmjopen-2022-062051supp001.pdf (53.2KB, pdf)

Article identification

We searched for articles in English and French, published between 1 January 2015 and 18 December 2020, in the following databases: PubMed, PsychINFO, Scopus and Cairn. We selected the articles based on a keyword search query organised around three concepts: health mediation as an intervention strategy (health mediation, community health, community approach, etc) or as a position adopted in a function (eg, health mediator, community health worker, peer mentor, etc), conditions of effectiveness, and underserved populations. The search equation is presented in online supplemental appendix 2.

bmjopen-2022-062051supp002.pdf (50.8KB, pdf)

Article selection

We selected the articles according to the following inclusion criteria:

Health mediation interventions or interventions to ‘going towards’ local populations and actors and seeking to strengthen the empowerment of individuals by a third-party mediator,

Intervention with a third-party mediator,

Interventions implemented in high-income countries,

Interventions conducted with underserved populations,

Articles questioning the conditions of effectiveness of the interventions carried out,

Articles in English and French.

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

Interventions without the presence of a third-party mediator,

Interventions conducted by peers (interface role with populations only),

Health mediation interventions in which the third-party mediator provides care,

Health promotion interventions that did not mobilise ‘going towards’ actions,

Interventions implemented in low and middle-income countries,

Interventions conducted in the general population,

Methods promoting community engagement in research

Articles that did not report the conditions of effectiveness of the intervention.

Data analysis

Data were analysed to help answer the following questions: What is the purpose of the study?; What is the target population?; What are the characteristics of the study?; What are the study designs in the different articles?; What intervention is implemented in detail?; What are the role and duties of the health mediator?; How is the intervention planned?; Is a community approach envisaged and implemented? If so, which one?; What is the implementation process?; What is the implementation context?; What are the identified effects of the intervention?; What are the conditions of effectiveness related to the context, the intervention, the actors, its organisation and the individuals?

Our analysis grid was built through two dimensions: (1) a descriptive dimension: design, planning, implementation process of health mediation, its effectiveness; (2) an analytical dimension assessing the conditions of its effectiveness (see online supplemental appendix 3). For the first dimension (1), we organised this description using two tools, the Template for intervention description and replication grid23 and the Tool for the Analysis of Transferability and Support for the Adaptation of Interventions in Health Promotion (Outil d’AnalySe de la Transférabilité et d’accompagnement à l’Adaptation des InteRventions en promotion de la santé, ASTAIRE).24 For the second dimension (2), we grouped the identified conditions of effectiveness into five categories: the conditions related to the context, the intervention, the organisation of the intervention, the actors and the persons. Finally, we added an analysis of cross-sectoral collaborations, that is, the level of interaction between sectors or between actors and/or institutions using the work of Bilodeau et al.25 For these authors, the first level of collaboration is networking, representing information exchange. Cooperation refers to working together to optimise resources to accomplish one’s own goals better. This requires less interdependence between sectors than the coordination of actions. Coordination involves joint work between actors to make mutual adjustments to render actions more coherent and robust to achieve shared objectives. Integration aims to co-construct new, more systemic interventions (eg, multisector government policies) and requires the integration of objectives, processes, resources, and actions. It requires an even higher degree of collaboration and interdependence between actors.25

bmjopen-2022-062051supp003.pdf (50.9KB, pdf)

Results

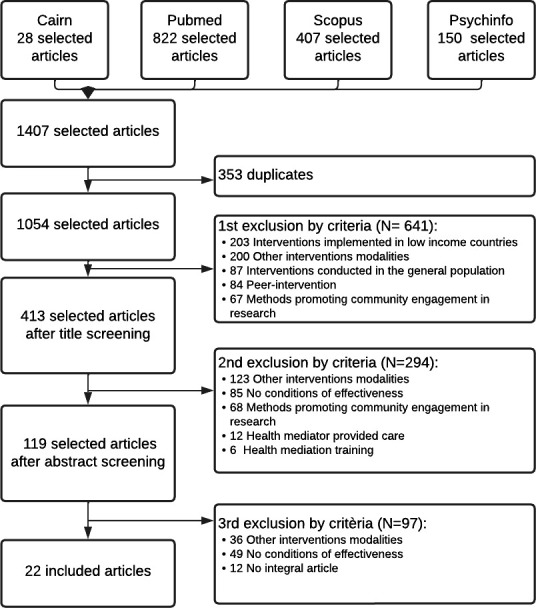

We identified 1407 articles. After selection, based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, and elimination of the duplicates, 22 articles were selected (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart for selecting articles according to established eligibility criteria.

Description

Among the 22 articles, eleven were conducted in the USA,26–36 nine in France,16 17 37–43 one in the UK44 and one in Australia.45

Twelve articles presented case studies,16 17 26 27 32 33 35–40 42 seven from literature reviews,29 31 41 43–45 two from cohort studies30 34 and one article presented one randomised controlled trial.28 A qualitative method was used in 20 articles, and a quantitative method in 2 articles.28 34

Twenty articles presented studies conducted on third-party mediators (ie, ‘person of trust, from or close to the population, competent and trained with guidance and support function; they create a link between the healthcare system and a population that has difficulty accessing it’11), and two collected data from persons of the intervention.33 45

In seven articles, third-party mediators intervened with underserved populations in general,26 29–32 34 37 including one article with Travellers,37 six articles with vulnerable populations,16 26 36 42–44 six articles with migrants,17 27 28 30 35 39 including three articles with Latin Americans27 30 35 and two articles with Roma.17 39

Health mediation: descriptive aspects

The missions of health mediation

The interventions promoted healthcare and essential service use, two of which focused on mental healthcare use37 40 and one on colorectal cancer screening.41 The health mediation intervention consisted of joint action methods by (1) education actions and navigation in care system aimed at persons, or (2) a third-party mediation.

The first type (1) referred to individual or collective educational actions. They offered support for persons in a logic of empowerment (ie, process by which an individual or a group acquires the means to strengthen their capacity for action).16 42 44 46 However, planned education actions were only possible when persons were stabilised and showed low competitiveness of needs, that is, the primary needs necessary for survival, such as food or housing, were secure.

The navigation actions focused on two complementary principles: the first is ‘going towards’, which locates and directs; the second is ‘bringing back to’, that is, the physical accompaniment of people to the healthcare system and essential services such as health insurance or social assistance services for persons.16 26 37 38 40 42 44 45

These education and navigation actions helped people understand and accompanied them in their healthcare use (identification of the need and promotion of access). Moreover, the health behaviours of third-party mediators were models of inspiration for behaviours favourable to persons’ health.33

The second type aimed to mobilise, engage and collaborate with local actors (ie, healthcare workers, social workers, decentralised state service agents and elected officials) and in particular healthcare workers to ‘be together’. The role of third-party mediators is to identify and consider the specific needs of these populations26 30 33 37 39 41 in order to ‘work together’ to share a diagnosis.16 26 27 29 38 43 44 They developed collaborations to more or less formalise steering role, local networking by sharing knowledge between healthcare workers, social sector workers, and public health and social institutions.30 41 42 These collaborations are intended to acculturate actors to underserved population’s needs37 39 and share concrete solutions for health. For example, free neighbourhood shuttles were set up to facilitate mobility to a medical centre following coordination between municipal services, third-party mediators and healthcare workers 32; or implementation of walk-in slots with healthcare workers to facilitate their availability about such as food or administrative insecurity and residential instability.16 32 These local actors formed a network capable of monitoring the difficulties encountered by underserveed populations and helping research by collecting health data and healthcare use, as proposed by Harris and Haines,44 during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK.44 So all actors could gather around a common interest or objective,37 41 although divergences, in particular between security versus health issues.38 41

The health mediator

The term used to designate the third-party mediator differed according to the countries and populations. They were called health mediators in France,16 17 37–43 community health workers in the USA,26–29 31–33 35 the UK44 and Australia,45 ‘promotor’ in Latin American populations30 34 or navigator in France.41 We grouped them under the term ‘health mediator’.

In the articles, the health mediators were employed mainly by associations16 17 37–40 42 with labile funds and a little perspective on contracts.27 44 As a result, there is no job security nor prospects for sustainability or career development.27 Moreover, the training and profiles of health mediators were very heterogeneous.17 37–40 43 44 The training could be of variable duration (3 months and 2 years).43 Some health mediators might not have a diploma,38 39 44 such as training in the health sector.37 40 They could come from the population or not, be trained or not. However, they acquired legitimacy with the population through their excellent knowledge of their territory, populations and local actors.28 33 41

The professional framework for health mediation is under construction.26–29 32 43–45 There is a significant ‘asymmetry’ in the training offer, whether the course or its local availability.43 45 Additionally, health mediator training is considered complex as it must articulate theoretical elements and integrate a degree of flexibility into the practice fields.26 Thus, there is no standard of duration or content to guarantee the quality of training.29 Health mediation competencies are poorly identified,44 the content is not homogeneous,32 44 and the visibility and recognition of this exercise in an integrated manner in the healthcare system32 45 and the populations32 38 45 are not stabilised. A few authors have nevertheless proposed the development of skills repositories in order to facilitate the professionalisation process.27 28 32 38

Effects of health mediation

Multiple outcome measures were used to determine the effects of health mediation on healthcare use: (1) participation rate in the health mediation actions, (2) criteria for essential services and healthcare use (eg, the number of entitlements to social security coverage issued),17 (3) health indicators (eg, measurement of body mass index or glycaemia).29 35 Other articles, primarily literature reviews, took the effectiveness of health mediation for granted and presented only an analysis of the conditions.27 32 44

Only one article included a process criterion—fidelity30 and notably highlighted the need to ensure that mediation is proportionate to the needs encountered. In particular, mediation was adjusted in frequency and duration to the characteristics of the persons and to the extent of the health and access to health problems with which they were confronted.30 The development stages of the health mediation action plan were covered in just one article. This was used to support its implementation on a French territory with the Roma and Traveller populations.17 However, the other articles mentioned planning, without specifying the development of the action plan and its stages, nor the anticipation of the necessary resources.

From the persons’ point of view, health mediation needed to (1) respond to their needs as they expressed it,26 38 (2) respect their need for control over the situation,41 (3) promote their ability to make their decisions41 and (4) strengthen their sense of self-efficiency (the personal ability to think that they can overcome obstacles to seek care) and their motivation to healthcare use, in a positive environment conducive to healthcare use.34 35 Health mediation should also strive to strengthen the ability to make decisions favourable to health in a logic of empowerment.33 40 43 To this end, health mediators could reinforce people’s perception of the healthcare benefits.34

Conditions for the success and feasibility of health mediation: analytical aspects

Limited funding

Health mediation was facilitated by a political and financial commitment from public social and health institutions, both local and national.27 29 The funding period, however, was short (1–3 years).27 29 This lack of sustainability was unsuited to the needs26 and created a form of insecurity for health mediators, particularly by a high turnover.31 Moreover, the articles also highlighted a poor connection between the needs of the people and the human resources available to implement mediation actions.41 44 Finally, a significant obstacle to the effectiveness of health mediation was highlighted: the difficulties encountered by health mediators in acting on the living conditions of the persons or health controversies relayed in the media.16 17 42 However, the purpose of health mediation is not to transform them (eg, the squalor of communal reception areas made available to Travellers).17 In this context, the role of mediators turns out to be one of catching up with an inadequate system, whose effectiveness can only be reduced in the event of inconsistent policies.

Success from a population-based approach

Health mediation draws its success from its population-based approach,31 44 that is, a holistic approach to health considering, on one hand, determinants outside the healthcare system, and on the other hand, the interdependence of these determinants and their systemic functioning. This approach differs from a disease-based and risk factor-based approach, often reduced to proximal behavioural factors. Thus, health mediation is accessible to the entire community and not only to those exposed to risk factors.44 This approach allows openness toward others while respecting their perceptions of illness, health and care.17

Health mediation was organised at the local level through the collaboration of the local actors.26 30 37 39 41 42 45 The collaboration led to establishing a trust relationship between local actors.42 While this collaboration led to a better interdependence of the actors, it benefited by remaining flexible, adaptable and on the border of the organisations.27 30 38 41 42 Moreover, the necessary cross-sectoral work is a source of resistance in certain institutions for which this is not the traditional mode of operation.44 29 38 42 44 Furthermore, the lack of development of a clear action plan limited its operationalisation.31

Need for integration into healthcare system

One of the significant conditions of health mediation on healthcare use was its integration into the care system.26–33 37–39 41 43–45 The lack of integration of health mediators presented as missed opportunities, for example, through the lack of information sharing between health mediators and healthcare workers,27 42 44 or even the difficulty in relating the health problems of persons and the healthcare use difficulties.44 The complexity of this integration lies in the difficulties of cooperation, setting up spaces for sharing knowledge27 38 and the presence of power issues between the social and medical fields.38 Notwithstanding these obstacles, some authors have proposed that health mediators serve as interfaces between ‘health and non-health resources’28 32 44 and thus manage this collaboration.28

Non-judgement communication posture and strong flexibility soft skills

The soft skills necessary for health mediation differed according to the persons of the intervention. A standard base of soft skills and professional posture could nevertheless emerge. The first essential soft skill was congruence with the persons.28 30 32 33 38 41 45 This congruence could be cultural, ethnic, linked to the life history or linked to the disease experience. The health mediator had to present essential soft skills favourable to communication: benevolent, adapted, listening and respectful attitude.16 28 33 35 37 41 Thus, communication had to be based on the principles of non-judgement, trust in the persons’ ability to make decisions that are favourable to their health and understanding of their representations, for example, how a person considered traditional medicine or the place of religion in health.16 28 33 37 Finally, the health mediator must show perseverance and great mental flexibility.41

These soft skills influence the mediator posture in their relationship with the persons. This must be based on equality, powers and knowledge sharing. This sharing takes root in the relationship of trust.16 28 32 35 38 The health mediator must offer support, favouring positive feedback during exchanges, or establishing ‘contracts’ of suitable and feasible progressive objectives while favouring the reinforcement of the persons’ abilities to make decisions favourable to their health.28 33

These soft skills and posture characteristics facilitate the establishment of a climate of trust,16 28 32 35 37 38 42 which reinforces them. All of this contributes to strengthening the empowerment of persons.16 28 42

Recruitment of health mediator

The recruitment of a health mediator is a crucial issue.26–29 31 38 41 The choice of the health mediator’s initial training was decisive, whether social or health training. Garcia and Grant29 favoured the recruitment of healthcare workers-health mediators to promote their integration with care services.29 In contrast, others favoured sociocultural training to facilitate integration within the populations.27 31 41 Indeed, Ingram et al27 specified that professionalisation could compromise cultural congruence.27 They stated that whatever the obstacles, the health mediator must retain their ability to adapt, with the possibility of providing appropriate support, thanks to their soft skills and an accurate and adaptive posture acquired through training or experience.27 For Gerbier-Aublanc,38 it was possible to move away from cultural congruence (ie, the same culture or ethnicity as the population served) to facilitate the integration of the health mediator into the care system while maintaining congruence with the health mediator life history.38

Discussion

Towards a conceptual framework of health mediation

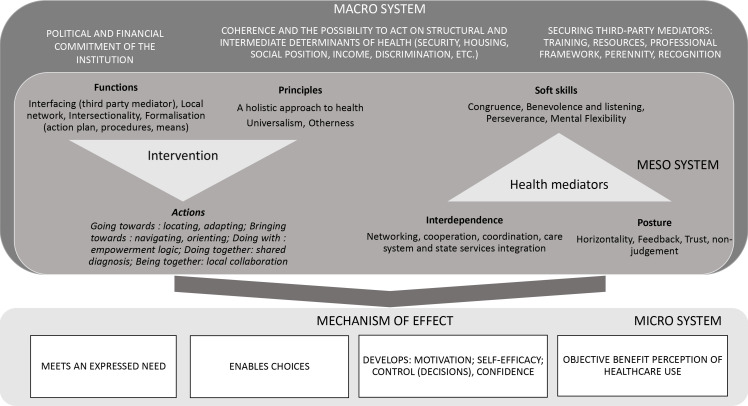

We conducted a scoping review which identified nine conditions for the success and feasibility of health mediation acting at different levels with underserved populations. This review underlines several characteristics of health mediation that articulate education and healthcare system navigation actions, along with actions of mobilisation, engagement, and collaboration of local actors among themselves and with the populations. Health mediation thus corresponds to a complex health intervention47 because of its contextual anchoring.48 Indeed, health mediation practices are multifaceted49 50 even though a joint intervention base exists. Health mediation has blurred boundaries in the healthcare system, torn between the community approach and the universalist paradigm, the biomedical and the social worlds.38 Consequently, health mediation must combine various practices to adapt to a socially changing context and the populations’ characteristics.10 To maintain this flexibility, health mediation could be considered as a systemic and dynamic process with multiple and permanent interactions between interventional and contextual components.51 Health mediation needs multiple interventions referring to multiple levels. It is an interventional system producing some mechanisms (ie, ‘elements of reasoning and reaction of an agent about an intervention producing a result in a given context’52) impacting themselves this interventional system.51 According to this systemic approach, we propose to map the data collected in a conceptual framework hypothesising their inter-relations (see figure 2).

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework of health mediation.

In this figure, the contextual components (ie, the factors external to the mediation intervention and which drive it) form the macro-system. This includes political and financial commitment, coherence and the possibility of acting on the structural and intermediate determinants of health, along with securing the health mediator in their activity. Additionally, other conditionsfor the effectiveness of health mediation are arranged within a meso-system closely circumscribing the actorsand characteristics specific to the intervention, organised in three pillars: the principles (ie, approach or paradigm), the functions (ie, key elements of the intervention assumed to be the basis of its effectiveness and which cannot be adapted53) and the actions of health mediation. The conditions linked to the health mediator are themselves organised in three pillars: soft skills, posture, and the interdependence between health mediator and the local actors and the population. Finally, mediation’s effect mechanisms, prefiguring its effectiveness in healthcare use, are positioned as seeking goals in mediation. It should be noted that although the persons remain central in this system, we were not able to collect in the literature any elements describing the characteristics specific to them. This constitutes a shortcoming that could be the subject of further research.

Interface difficulties: the inability to act on healthcare system organisation

The healthcare system is organised with a strong structural compartmentalisation between the social and medical worlds. It hinders the congruence of decision-making needed to manage the complex issues posed by underserved populations. Health mediation represents a ‘border organisation’,54 interfacing with the different communities. This role is possible thanks to a combination of soft skills, such as flexibility and neutrality, know-how and professional postures, allowing for both the coexistence of divergent interests and the rallying around common objectives.54 Nevertheless, this role raises some questions for health mediators: Aren’t the issues at stake in the organisation of the healthcare system itself (ie, based on universality paradigm)? Indeed, the French healthcare system is built in a universalism paradigm. This has long made the idea of no access to care unthinkable.55 Yet, what is universal (ie, the same service for all) is not necessarily equitable. Indeed, health equity is achieving the highest level of health for all people. It entails focused societal efforts to address avoidable structural inequalities by equalising the conditions for health for all groups, especially for those who have experienced socioeconomic disadvantage or historical injustices. This requires, among other things, rethinking the system and environments so that it adapts to the different needs of the populations and understands the structural inequalities. Instead, health mediation catches up with the individual consequences of an inadequate system to the difficulties encountered by populations,56 built by economic cost reduction considerations.49 56

The second question is: Does health mediation seek to emancipate people or gently impose behavioural norms to bring people back to a system that is nevertheless inadequate? Indeed, although the term ‘empowerment’ is regularly used, it raises questions when health mediation aims to make adopted behaviours considered as ‘good’ by a third party. It is a normative approach, different from community health,57 sometimes referred in articles, and calling for action58 based on a process of knowledge and issues co-construction, rather than rallying some people to behaviours decided by others. Therefore, it could be necessary to clarify characteristics and goals of health mediation if the purpose is to provide autonomy: what autonomy? in whose eyes? for whom?59

Study limitations

Our study has certain limitations. First, we have selected articles on titles only for feasibility reasons (selection on titles and abstracts would have identified 7514 articles). Even if the nature of the review (a scoping review) does not require exhaustive identification, this constitutes a limitation to the study.

The second limit is the polysemy of the word mediation and the variety of terms used according to the concept of mediation. They are some obstacles to the in-depth exploration of the actions carried out. Indeed, this led to identifying a significant number of articles. For example, we made the interventions conducted by peers in the equation finally excluded because they did not correspond to the same interventional logic. Consequently, we cannot exclude the possibility of selection biases. Moreover, we observed conceptions sometimes very far removed from mediation, from empowerment to ‘bringing back to’, which, as developed above, is closer to health education.

Additionally, the people’s point of view is very poorly assessed in the articles: What do they think?; Are there any prerequisites for effective mediation? To complete the framework presented, observations and interviews with communities’ members about their own experience are needed.

Finally, the review is based on articles using different methods and the effectiveness is unevenly addressed. Finally, the relevance of mediation is discussed from the actors’ point of view more than effectiveness as an object of scientific demonstration. Moreover, it remains difficult to evaluate the effectiveness of health mediation without having clarified its purpose: to bring people back to a system not designed for them by making them adopt behaviours considered appropriate from the point of view of a third party? Or to give them the means to make an informed choice, including choosing not to use care?

Conclusion

Health mediation is more than ever on the agenda of health authorities. The scoping review allows us to draw up an initial framework for analysing the conditions of successful and feasible health mediation and to question the coherence of the approach to health mediation considering the divergent tensions and logic that permeate it. Thus, three questions remain: (1) How can we reconcile empowerment and the more normative logic of ‘bringing back to’?; (2) How can we secure health mediators to promote the sustainability and effectiveness of mediation mechanisms?; (3) How can we resolve the tensions between a ‘going towards’ approach rendered almost palliative by the inability of the actors to modify ‘the causes of the causes’ of the lack of care?

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

SV and LC contributed equally.

Contributors: ER has made substantial contributions to the conception and design, data collection and analysis, drafting and critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content. LC and SV have participated in developing the review protocol, data collection and analysis and have contributed to the manuscript. They have also supervised this work. LC proposed the first version of the model. All authors discussed the results. They gave final approval of the version to be published. They agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. ER is the author responsible for the overall content as the guarantor. SV and LC are co-last authors.

Funding: This work was supported by the French National Cancer institute (INCA) (grant: 2021/008), and the National Federation of Associations in Solidarity with Gypsies and Travellers (Fnasat-GV).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Rockliffe L, Chorley AJ, Marlow LAV, et al. It’s hard to reach the “hard-to-reach”: the challenges of recruiting people who do not access preventative healthcare services into interview studies. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2018;13:8. 10.1080/17482631.2018.1479582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Legros M. Pour un accès plus égal et facilité La santé et aux soins. 54, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bounaud V, Texier N. Facteurs de non-recours aux soins des personnes en situation de précarité. ORS 2017;37. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rode A. L’émergence du non-recours aux soins des populations précaires : entre droit aux soins et devoirs de soins. Lien Soc Polit 2009;61:149–58. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vuillermoz C, Vandentorren S, Brondeel R, et al. Unmet healthcare needs in homeless women with children in the greater Paris area in France. PLoS One 2017;12:e0184138. 10.1371/journal.pone.0184138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quirke B, Heinen M, Fitzpatrick P. Experience of discrimination and engagement with mental health and other services by travellers in Ireland: findings from the all Ireland traveller health study (AITHS). Ir J Psychol Med 2020;27:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdalla S, Cronin F, Daly L. birth cohort study and for analysis of children’s health status sections of census survey, et al. All Ireland Traveller Health Study 2010:200. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res 2000;34:1273–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farnarier C, Fano M, Magnani C. Trajectoire de soins des personnes SANS abri Marseille. Rapport de Recherche final Enquête TREPSAM. ARS-PACAAPHMUMI. 3189, 2015: 136. [Google Scholar]

- 10.HAS . La médiation en santé pour les personnes éloignées des systèmes de Prévention et de soins. 70, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blanc G, Pelosse L. La médiation santé : Un outil pour l’accès la santé ? FRAES. 22, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Haut conseil de la santé publique. Inégalités sociales de santé : sortir de la fatalité HCSP. 2009;101 [Google Scholar]

- 13.OMS . Déclaration d’Alma-Ata sur les soins de santé primaires. OMS 1978;90. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guillaume-Hofnung M. La Médiation. Que sais je ? 2020;128. [Google Scholar]

- 15.ASAV . Programme national de médiation sanitaire en direction des populations en situation de précarité. INPES 2014;32. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haschar-Noé N, Basson JC. Innovations en santé, dispositifs expérimentaux et changement social : un renouvellement par le bas de l’action publique locale de santé Innovations. 60, 2019: 121–44. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teoran J, Rustico J. Un programme national de médiation sanitaire. Etudes Tsiganes 2013;52-53:181–9. 10.3917/tsig.052.0181 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DGS . Évaluation des actions de proximité des médiateurs de santé publique et de leur formation dans le cadre d’un programme expérimental mis en oeuvre par l’IMEA. Paris: Ministère de la santé et des solidarités, 2006: 136. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Musso S, Delaquaize H. Réinventer La roue? La difficile capitalisation des expériences de médiation en santé en France. Conv Natl 2016 Sidaction Juin, 2016: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sucharew H, Macaluso M, Sucharew H. Progress notes: methods for research evidence synthesis: the scoping review approach. J Hosp Med 2019;14:416. 10.12788/jhm.3248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18:143. 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pichonnaz C, Grant K. Liste d’items TIDieR (Template for Intervention Description and Replication - Modèle pour la description et la réplication des interventions); 2016: 2.

- 24.Cambon L, Minary L, Ridde V, et al. Un outil pour accompagner la transférabilité des interventions en promotion de la santé : ASTAIRE. Sante Publique 2015;26:783–6. 10.3917/spub.146.0783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bilodeau A, anne PA, Potvin L. Les collaborations intersectorielles et l’action en partenariat comment ça marche? Chaire Rech Can Approch Communaut Inégalités Santé 2019;43. 10.1080/09581596.2017.1343934 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menser T, Swoboda C, Sieck C, et al. A community health worker home visit program: facilitators and barriers of program implementation. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2020;31:370–81. 10.1353/hpu.2020.0028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ingram M, Sabo S, Redondo F, et al. Establishing voluntary certification of community health workers in Arizona: a policy case study of building a unified workforce. Hum Resour Health 2020;18:46. 10.1186/s12960-020-00487-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Islam N, Shapiro E, Wyatt L, et al. Evaluating community health workers' attributes, roles, and pathways of action in immigrant communities. Prev Med 2017;103:1–7. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.07.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia ME, Grant RW. Community health workers: a missing piece of the puzzle for complex patients with diabetes? J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:878–9. 10.1007/s11606-015-3320-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Documet PI, Macia L, Thompson A, et al. A male Promotores network for Latinos: process evaluation from a community-based participatory project. Health Promot Pract 2016;17:332–42. 10.1177/1524839915609059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kangovi S, Grande D, Trinh-Shevrin C. From rhetoric to reality--community health workers in post-reform U.S. health care. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2277–9. 10.1056/NEJMp1502569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Islam N, Nadkarni SK, Zahn D, et al. Integrating community health workers within patient protection and Affordable care act implementation. J Public Health Manag Pract 2015;21:42–50. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katigbak C, Van Devanter N, Islam N, et al. Partners in health: a conceptual framework for the role of community health workers in facilitating patients' adoption of healthy behaviors. Am J Public Health 2015;105:872–80. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balcázar HG, de Heer HD, Wise Thomas S, et al. Promotoras can facilitate use of recreational community resources: the MI Corazón MI Comunidad cohort study. Health Promot Pract 2016;17:343–52. 10.1177/1524839915609060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Falbe J, Friedman LE, Sokal-Gutierrez K, et al. "She Gave Me the Confidence to Open Up": Bridging Communication by Promotoras in a Childhood Obesity Intervention for Latino Families. Health Educ Behav 2017;44:728–37. 10.1177/1090198117727323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saint Onge JM, Brooks JV. The exchange and use of cultural and social capital among community health workers in the United States. Sociol Health Illn 2021;43:299–315. 10.1111/1467-9566.13219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trompesance T, Jan O. Accès aux soins en santé mentale et médiations en santé. Expérience rouennaise destination des gens Du voyage VST - Vie Soc Trait. 146, 2020: 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gerbier-Aublanc M. La médiation en santé : contours et enjeux d’un métier interstitiel - L’exemple des immigrant·e·s vivant avec le VIH en France. Zenodo 2020;14. 10.5281/zenodo.3773295 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lahmidi N, Lemonnier V. Médiation en santé dans les squats et les bidonvilles rhizome. 68, 2018: 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Einhorn L, Rivière M, Chappuis M. Proposer une réponse en santé mentale et soutien psychosocial aux exilés en contexte de crise. L’expérience de Médecins du Monde en Calaisis (2015-2017). Remi 2018;34:187–203. 10.4000/remi.10581 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramone-Louis J, Buthion V. Réduire les disparités de participation au dépistage du cancer colorectal par une organisation la frontière du dispositif de prévention : quand analyse de terrain et théorie se rejoignent. J Gest Econ Medicales 2016;34:215–38. 10.3917/jgem.164.0215 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haschar-Noé N, Basson J-C. La médiation comme voie d’accès aux droits et aux services en santé des populations vulnérables. Le cas de la Case de santé et de l’Atelier santé ville des quartiers Nord de Toulouse. Revue d'Épidémiologie et de Santé Publique 2019;67:S58–9. 10.1016/j.respe.2018.12.044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haschar-Noé N, Bérault F. La médiation en santé : une innovation sociale ? Obstacles, formations et besoins. Santé Publique 2019;31:31–42. 10.3917/spub.191.0031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harris MJ, Haines A. The potential contribution of community health workers to improving health outcomes in UK primary care. J R Soc Med 2012;105:330–5. 10.1258/jrsm.2012.120047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sharma N, Harris E, Lloyd J, et al. Community health workers involvement in preventative care in primary healthcare: a systematic scoping review. BMJ Open 2019;9:e031666. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bacque MH. Territ Mens Démocr Locale. In: L’intraduisible notion d’empowerment vu au fil des politiques urbaines américaines. 460, 2005: 32–5. [Google Scholar]

- 47.OMS . International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF. 20, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cambon L, Alla F. Understanding the complexity of population health interventions: assessing intervention system theory (ISyT). Health Res Policy Syst 2021;19:95. 10.1186/s12961-021-00743-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Faget J. Médiations : les ateliers silencieux de la démocratie ERES. 304, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tapia C. La médiation : aspects théoriques et foisonnement de pratiques. Connexions 2010;93:11–22. 10.3917/cnx.093.0011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cambon L, Terral P, Alla F. From intervention to interventional system: towards greater theorization in population health intervention research. BMC Public Health 2019;19:339. 10.1186/s12889-019-6663-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lacouture A, Breton E, Guichard A, et al. The concept of mechanism from a realist approach: a scoping review to facilitate its operationalization in public health program evaluation. Implement Sci 2015;10:10. 10.1186/s13012-015-0345-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Theorising interventions as events in systems. Am J Community Psychol juin 2009;43:267–76. 10.1007/s10464-009-9229-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peton H. Organisation frontière et maintien institutionnel. Le Cas Du Comité permanent amiante en France. Rev Francaise Gest 2011;217:117–35. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fassin D. L’internationalisation de la santé : entre culturalisme et universalisme 1940. Esprit 1997;229:83–105. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rouzé V. Médiation/s : un avatar du régime de la communication ? Enjeux Inf Commun. 2010;Dossier 2010;2:71–87. 10.3917/enic.hs02.0500 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Desgroseillers V, Vonarx N, Guichard A. La santé communautaire en 4 actes. Repères, acteurs, démarches et défis. 364, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Secrétariat Européen des pratiques de santé communautaire . Les repères des démarches communautaires. 3, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paul M. L’accompagnement comme posture professionnelle spécifique. Rech Soins Infirm 2012;110:13–20. 10.3917/rsi.110.0013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-062051supp001.pdf (53.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-062051supp002.pdf (50.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-062051supp003.pdf (50.9KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.