ABSTRACT.

Bubble CPAP is used in low-resource settings to support children with pneumonia. Low-cost modifications of bubble CPAP using 100% oxygen introduces the risk of hyperoxia. Our team developed a low-cost, readily constructible oxygen blender to lower the oxygen concentration. The next step in development was to test its construction among new users and ascertain three outcomes: construction time, outflow oxygen concentration, and an assessment of the user experience. Workshops were conducted in two countries. Instructions were delivered using a live demonstration, a video, and written instructions in the respective native language. Twelve volunteers participated. Average construction times were 24 minutes for the first attempt and 15 minutes for the second. The oxygen concentrations were 53–63% and 41–51% for the 5 and 10 mm entrainment ports, respectively. This novel, low-cost oxygen blender for bubble CPAP can be constructed among new users with reliable performance across devices.

Lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs) continue to be the leading cause of death among children less than 5 years of age worldwide.1–4 The burden is particularly significant in low-middle income countries (LMICs).1,4 Respiratory support is key in decreasing mortality from LRTIs. Unfortunately, most respiratory support modalities, such as devices that provide continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), have limited availability in LMICs due to multiple factors.5 Commercial CPAP devices cost thousands of dollars and require electricity. In the 1970s, an alternative form of CPAP, called bubble CPAP (bCPAP), was invented for use in neonates.6 Unlike ventilator-derived CPAP, bCPAP does not require electricity and can run on compressed air or oxygen. Over the past several years, a low-cost version of bCPAP has been developed, validated, and used extensively in LMICs. This version uses basic equipment readily found in a hospital setting in LMICs and has allowed hospitals to provide effective and safe respiratory support to their young children at minimal cost (approximately five USD excluding the cost of oxygen).7

One opportunity for advancement is titration of the oxygen concentration delivered as this low-cost design usually uses pressurized 100% oxygen. It is well documented that use of high-concentration oxygen can have harmful effects in the brain, lungs, heart, and eyes.8,9 Indeed, current guidelines for neonatal resuscitation strongly recommend starting with 21% oxygen, instead of 100% oxygen to avoid oxygen toxicity, titrating up the oxygen concentration only if hypoxia is documented using pulse oximetry.10 Of note, bCPAP is frequently used in neonates, which further emphasizes the need for a way to deliver lower oxygen concentrations. In addition, current methods of delivering variable concentrations of oxygen are generally quite expensive (approximately 1,000 USD) and not available to hospitals in LMICs.

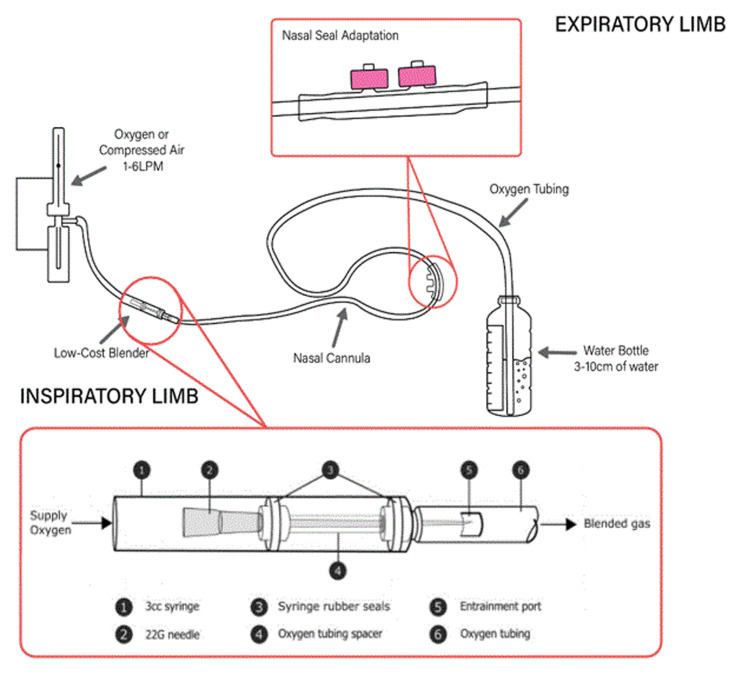

Our team successfully developed an oxygen blender prototype that operates based on the Venturi effect. The Venturi effect describes how the constricted flow of a fluid generates a reduction of fluid pressure and thereby creates a pressure gradient between the flow (i.e., 100% oxygen stream) and ambient air (i.e., 21% oxygen in room air). The novel blender can be assembled to complement the WHO bubble CPAP circuit design and only requires common hospital supplies to build (Figure 1).11 Based on bench testing, when used with a low-cost bCPAP circuit, the device can decrease oxygen concentrations to approximately 60–70% and 40–50% with 5 and 10 mm entrainment ports, respectively. In this short report, we detail the organization, implementation, and results of two workshops designed to test feasibility of construction and validation of the device’s function.

Figure 1.

Bubble CPAP set-up with oxygen blender in-line. Graphic credit: Mara T. Halvorson. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Two workshops were organized and conducted asynchronously—one at an academic university in the United States and another in a rural hospital setting in Cambodia.

Volunteers were recruited by personal invitation. None of the participants had used or seen the blender device before these workshops. In the U.S. location, seven participants with a variety of university roles including physicians, nurses, and graduate students were recruited to participate. In the Cambodia location, five participants were recruited—four nurses and one physician. Written instructions prepared by the study team were provided to the participants to follow along during the live and video demonstrations. Live demonstration was performed by members of the study team. A prerecorded video by the study team was then shown to the participants demonstrating the same steps as those in the live example. The participants were then allowed to construct the devices themselves, and individual timers were started to record construction times. Surveys were distributed to participants for self-reported outcomes, including age, highest educational degree, time for construction, oxygen concentration of the outflow, and difficulty understanding instructions and constructing the device (using a scale of 1–10 with 10 being the most difficult). The other measurements such as entrainment port length, flow rate from the tank, and CPAP level were recorded by the study team members moderating the workshop.

Devices were tested at a flow of 3 L per minute (LPM) of 100% oxygen from a tank and bCPAP level of 5 cm H2O in the USA cohort. The devices created in the workshop in Cambodia were tested with flow of 2 LPM of 100% oxygen from a tank and bCPAP level of 3 cm H2O to conserve oxygen supply. The primary outcomes were construction time, the outflow oxygen concentrations, and the impressions of new users in the construction experience. A device was considered functional if the bCPAP circuit bubbled and it produced an outflow oxygen concentration less than 100%. To determine outflow oxygen, an oxygen analyzer was either placed in-line with the circuit between the nasal cannula and the blender using a T-piece adapter for oxygen tubing (USA) or by placing the analyzer at the nasal cannula (Cambodia). The Institutional Review Board at the University of Minnesota deemed this evaluation as exempt.

Averages and confidence intervals of the mean differences were calculated for the primary outcomes for each separate workshop. Two-tailed t tests assuming unequal variances were performed in Microsoft Excel for Microsoft 365 MSO (16.0.13929.20360) to determine any statistically significant differences between the average ages, reported difficulty levels, construction times, and oxygen concentrations between the USA and Cambodia groups. A box-whisker plot was used in the same Microsoft Excel software to graphically present the oxygen concentration data between the USA and Cambodia groups as well as between the two entrainment port sizes. A P value < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

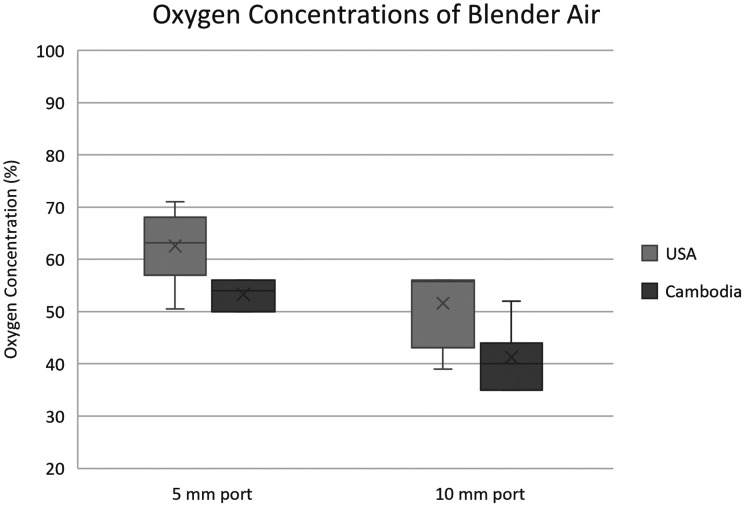

The average construction time for the first attempt was 21 minutes in the USA cohort and 27 minutes in the Cambodia cohort (Table 1). The average construction time on second attempt was faster for both groups—13 minutes and 17 minutes for the USA and Cambodia groups, respectively. All blenders were functional. The average oxygen concentration with a 5-mm entrainment port was 63% in the USA cohort and 53% in the Cambodia cohort (P = 0.02). The average oxygen concentration with a 10-mm entrainment port was 51% in the USA cohort and 41% in the Cambodia cohort (P = 0.08) (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Outcomes from survey data

| Outcome measure | USA | Cambodia | P value | Mean difference (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 32.7 | 29.5 | 0.36 | 3.21 (4.56, 10.99) | |

| Construction time (min:sec) | First device | 21:20 | 27:48 | 0.25 | 6.46 (5.27, 18.19) |

| Second device | 13:04 | 17:36 | 0.03 | 4.52 (0.44, 8.60) | |

| Oxygen concentrations | 5 mm port | 63% | 53% | 0.02 | 9.25 (1.96, 16.5) |

| 10 mm port | 51% | 41% | 0.08 | 10.3 (−1.9, 22.6) | |

| Construction experience | Difficulty understanding instructions | 2.9 | 5 | 0.09 | 2.14 (−0.38, 4.66) |

| Difficulty constructing device | 4.9 | 5.6 | 0.37 | 0.74 (−1.00, 2.49) | |

Data are displayed as averages unless otherwise notated.

Figure 2.

Oxygen concentrations of blended air with two entrainment port sizes. In the USA cohort, measurements were done with 5 cm H2O of bubble CPAP and 3 L per minute (LPM) from an oxygen tank. In the Cambodia cohort, 3 cm H2O was used with 2 LPM of flow.

The lower oxygen concentrations in the Cambodia cohort can likely be attributed to differences in flow control mechanisms. In the Cambodia cohort, an oxygen tank with a rotameter was used to control flow, while the USA cohort used a dial-indicated variable orifice valve. The rotameter physically measures the flow rate out of the oxygen tank, while the variable orifice valve relies on empirical correlations and assumes a known differential pressure. This assumption is broken by the substantial upstream pressure created by the blender, causing a lower differential in the variable orifice valve, which then overestimates the flow rate. Since flow rate is inversely proportional to oxygen concentration, the Cambodia cohort’s true flow rate could be higher than the USA cohort, resulting in lower oxygen concentrations for the same entrainment port size.11

The workshops described above demonstrate that construction of this new oxygen blender device by first-time users is feasible within a reasonable time frame and meets expected oxygen concentration targets. All devices demonstrated a decrease in oxygen concentration from 100% using a 5-mm entrainment port and a further decrease using a 10-mm entrainment port. Furthermore, repeat construction of the device took approximately half the average time of the first construction.

The largest limitation of this study was that the device has not yet been clinically tested in a patient population. The goal of this preliminary study was to evaluate the feasibility of accurate construction among first-time users. A clinical trial was beyond the scope of the work described above but will be a key next step in assessment of the device. A clinical trial is needed to determine the actual feasibility of the product in a clinical setting and thus should not be used in clinical practice until safety has been demonstrated. This device has the potential to advance the safety of low-cost modified bubble CPAP circuits by lessening the risk of oxygen toxicity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the volunteers who generously offered their time to participate in these workshops. We are also grateful to the Earl E. Bakken Medical Devices Center and Chenla Children’s Healthcare for allowing us to use their physical space to conduct these workshops.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO, 2016. Pneumonia. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- 2.Liu L et al.; Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group of WHO and UNICEF, 2012. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet 379: 2151–2161. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Lozano R et al., 2012. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380: 2095–2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4. Liu L. et al. , 2016. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000-15: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the sustainable development goals. Lancet 388: 3027–3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boyd J, 2014. Clinical Study Finds ‘Bubble CPAP’ Boosts Neonatal Survival Rates [Website]. Rice University. Available at: http://news.rice.edu/2014/01/29/clinical-study-finds-bubble-cpap-boosts-neonatal-survival-rates-2/.

- 6. Lee KS, Dunn MS, Fenwick M, Shennan AT, 1998. A comparison of underwater bubble continuous positive airway pressure with ventilator-derived continuous positive airway pressure in premature neonates ready for extubation. Neonatology 73: 69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Duke T. et al. , 2016. Oxygen Therapy for Children. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Helmerhorst HJF, Schultz MJ, van der Voort PHJ, de Jonge E, van Westerloo DJ, 2015. Bench-to-bedside review: the effects of hyperoxia during critical illness. Crit Care 19: 284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stolmeijer R, Bouma HR, Zijlstra JG, Drost-de Klerck AM, Ter Maaten JC, Ligtenberg JJM, 2018. A systematic review of the effects of hyperoxia in acutely ill patients: should we aim for less? BioMed Res Int 2018: 7841295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tan A, Schulze A, O’Donnell CP, Davis PG, 2005. Air versus oxygen for resuscitation of infants at birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD002273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Floersch J. et al. , 2020. A low-resource oxygen blender prototype for use in modified bubble CPAP circuits. J Med Device 14: 015001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]