ABSTRACT.

Zika virus (ZIKV) has had a history in Malaysia since its first isolation in 1966. However, it is believed that the immunity status among forest fringe communities has been underreported. We conducted cross-sectional surveillance of forest fringe communities from 10 Orang Asli villages and their peripheral communities in Perak, Pahang, and Sabah in Malaysia. A total of 706 samples were collected from 2019 to 2020 and screened for ZIKV exposure using an anti-ZIKV IgG ELISA kit. A neutralization assay against ZIKV was used to confirm the reactive samples. The seroprevalence results reported from the study of this population in Malaysia were 21.0% (n = 148, 95% CI, 0.183–0.273) after confirmation with a foci reduction neutralization test. The presence of neutralizing antibodies provides evidence that the studied forest fringe communities in Malaysia have been exposed to ZIKV. Multivariate analysis showed that those older than 44 years and those with an education below the university level had been exposed significantly to ZIKV. In addition, higher seropositivity rates to ZIKV were also reported among secondary school students from Bentong (Pahang) and residents from Segaliud (Sabah). No associations were identified between Zika seropositivity and gender, household size, house radius to the jungle, and income level. The presence of neutralizing antibodies against ZIKV among the study population might indicate that the causative pathogen had already circulated widely in forest fringe regions. Intervention for vector control, protection from mosquito bites, and awareness improvement should be encouraged in this population.

INTRODUCTION

Zika virus (ZIKV), a mosquito-borne flavivirus belonging to the family Flaviviridae, which also involves several flaviviruses such as dengue virus (DENV), yellow fever virus, West Nile virus, and Japanese encephalitis virus,1 has recently received global attention after unprecedented epidemics in Africa, Yap Island, French Polynesia, and Brazil, with more than 1.3 million suspected cases of ZIKV being reported.2–5 These epidemics revealed two potential complications in ZIKV infections: a significant increase in the number of cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome (an autoimmune disease) and an increase in microcephaly cases (fetal abnormalities).6 As of 2019, 87 countries had reported the autochthonous transmission of ZIKV, suggesting that the spread of mosquito vectors (Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus) and the virus species they carry had been facilitated and was present worldwide.7,8

In Malaysia, ZIKV was first isolated from Ae. aegypti mosquitoes in Bentong, Pahang, in 1966.9 ZIKV is transmitted primarily by infected Aedes species mosquitoes, which can also transmit DENV and Chikungunya virus. Surveillance of these viruses in Malaysia focuses mainly on detecting acute and recent infections, especially among travelers.10 Because DENV is endemic in Malaysia, the annual dengue incidence reported between 2000 and 2014 was as high as 7,103 to 108,698 cases.11 In addition, Malaysia has also recorded continuously increasing annual cases of Chikungunya virus infection since the first outbreak in the country in 1998.12 However, ZIKV infection was not as widespread as it was in neighboring countries such as Singapore and Thailand, which were affected by the Zika pandemic in 2016.13,14 In September 2016, Malaysia reported its first autochthonous Zika case, with an imported case from Singapore also reported the same year.15 Given the asymptomatic nature of ZIKV infection, ZIKV circulation may be underestimated as a result of the lack of specific surveillance and a misinterpretation of the disease because its clinical presentations are similar to other endemic febrile diseases.16,17 As of 2019, the total number of Zika cases in Malaysia was 10, associated with symptomatic patients who mostly without travel history to other countries.18 Nevertheless, the threat of future Zika outbreaks in Malaysia remains, and the reasons for this are many and warrant further investigation.

ZIKV was isolated from a mosquito caught from a semi-forested area in Malaysia.9 ZIKV infection has been associated with lower socioeconomic status.19 According to Khor and Shariff,20 forest fringe communities have been identified as one of the most disadvantaged groups in Malaysia, with limited access to basic health care, education, food, and healthy nutrition. These groups of people rely on the forest for their livelihoods; their common occupations involve agriculture, fishing, collecting forest produce, and hunting.21 One would expect that these living conditions would foster the spread of ZIKV infection as non-human primates could be potential carriers and spread the disease to humans.22,23 Because of their lifestyle and involvement in agricultural activities, a high prevalence of ZIKV infection has been reported among local populations living in different geographic regions in Malaysia.23,24 In a previous study of the local population from forested areas in Sabah, Zika seroprevalence in humans was reported to be 30%.23 In another study, a Zika seroprevalence of 13.2% was reported among the indigenous people living in the forest fringes and forested areas in Peninsular Malaysia.24 However, reports on ZIKV infection from the flavivirus notification system in Malaysia remain scarce. Hence, the current study intended to expand the study of seroprevalence to other sites in Peninsular Malaysia and Sabah, which could help to identify past ZIKV infections in the population.

Through an understanding of epidemiology and causative factors, planning for and prevention of the disease could be facilitated. In a previous dengue seroprevalence study, an association of DENV infection with age was reported; dengue seropositivity increased with age in Malaysia (Johor).25 In urban areas, geographic factors could also correlate with dengue seroprevalence, including land development, decreased vegetation, and overall population growth.26, Abd-Jamil et al.27 reported that dengue seroprevalence in a rural setting was greater for individuals older than 13 years, among those with a low household income, and among those who live near a lake. Greater seroprevalence was also attributed to higher land surface temperatures and low land elevations,27 revealing the role of demographic and geographic factors in dengue seroprevalence. Hence, our current study included some of the previously mentioned risk factors to identify whether they also put the forest fringe communities in Malaysia at risk of ZIKV infection. After identifying the risk factors, planning for and prevention of the disease could be carried out. This study aimed to determine the seroprevalence of ZIKV infection among forest fringe communities in Malaysia based on the antibodies against ZIKV, and to identify which risk factors might contribute to Zika seroprevalence in Malaysia.28,29

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics approval.

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the Medical Research Ethics Committee, Ministry of Health (KKM/NIHSEC/P19-1584[15] and KKM/NIHSEC/P20-36), the University Kebangsaan Malaysia Research and Ethics Committee (UKM PPI/111/8/JEP-2019-104), and the University of Malaya Research Ethics Committee (UM.TNC2/UMREC-680).

Study sites.

This study was conducted in Malaysia, with the serum samples collected from five districts in Perak, Pahang, and Sabah in 2019 and 2020 (Figure 1). The selection of participants was based on eligibility criteria for a healthy general population. The participants were selected randomly from forest fringe communities (Table 3). The minimum number of participants was estimated to be representative of the general populations living in the forest fringe areas of Peninsular Malaysia (Perak and Pahang) and East Malaysia (Sabah) who had previous or potential ZIKV exposure (see calculations in Supplemental Information S1).

Figure 1.

Study sites for samples collection in Peninsular Malaysia and Sabah. The smaller scale Southeast Asia map is shown at the bottom right. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors associated with possible Zika virus seropositivity

| Factor | n (%) | Possible Zika virus seropositive, n (%) | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |||

| Age group, y | – | – | – | < 0.001† | – | < 0.001† |

| 18–24 | 152 (21.5) | 14 (9.2) | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| 25–34 | 139 (19.7) | 18 (12.9) | 0.70 (0.30–1.63) | 0.409 | 0.68 (0.30–1.56) | NS |

| 35–44 | 141 (20.0) | 27 (19.1) | 1.35 (0.62–2.91) | 0.449 | 1.35 (0.63–2.89) | NS |

| 45–54 | 133 (18.8) | 35 (26.3) | 2.13 (1.01–4.52) | 0.048* | 2.22 (1.06–4.68) | 0.035* |

| > 54 | 141 (20.0) | 54 (38.3) | 3.72 (1.74–7.96) | 0.001† | 3.81 (1.81–8.01) | < 0.001† |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 218 (30.9) | 50 (22.9) | 1.33 (0.86–2.05) | 0.202 | – | – |

| Female | 488 (69.1) | 98 (20.1) | Reference | – | – | |

| Size of household | ||||||

| < 5 | 442 (62.6) | 90 (20.4) | 0.88 (0.56–1.37) | 0.561 | – | – |

| > 5 | 264 (37.4) | 58 (22.0) | Reference | – | – | – |

| Study site | – | – | – | < 0.001† | – | < 0.001† |

| Site A | 137 (19.4) | 24 (17.5) | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| Site B | 94 (13.3) | 22 (23.4) | 1.31 (0.66–2.59) | 0.446 | 1.31 (0.66–2.58) | NS |

| Residential areas | 109 (15.4) | 13 (11.9) | 0.76 (0.29–2.00) | 0.580 | 0.73 (0.28–1.88) | NS |

| Secondary school | 93 (13.2) | 1 (1.1) | 3.53 (1.59–7.82) | 0.002* | 3.42 (1.55–7.52) | 0.002* |

| Pulau Gaya | 43 (6.1) | 22 (51.2) | 2.42 (0.90–6.53) | 0.080 | 2.42 (0.91–6.45) | NS |

| Telipok | 27 (3.8) | 6 (22.2) | 0.45 (0.18–1.13) | 0.088 | 0.53 (0.24–1.18) | NS |

| University | 79 (11.2) | 33 (41.8) | 0.17 (0.02–1.57) | 0.117 | 0.16 (0.02–1.52) | NS |

| Ranau | 24 (3.4) | 9 (37.5) | 1.17 (0.46–2.98) | 0.749 | 0.91 (0.39–2.08) | NS |

| Site C | 48 (6.8) | 7 (14.6) | 0.96 (0.32–2.84) | 0.940 | 1.08 (0.38–3.09) | NS |

| Segaliud | 52 (7.4) | 11 (21.2) | 4.09 (1.99–8.42) | < 0.001† | 3.50 (1.75–6.97) | < 0.001† |

| State | – | – | – | < 0.001† | – | < 0.001† |

| Perak | 231 (32.7) | 46 (19.9) | Reference | – | – | |

| Pahang | 202 (28.6) | 14 (6.9) | 0.17 (0.02–1.57) | 0.117 | 0.16 (0.02–1.52) | NS |

| Sabah | 273 (38.7) | 88 (32.2) | 4.09 (1.99–8.42) | < 0.001† | 3.50 (1.75–6.97) | < 0.001† |

| Education level | – | – | – | 0.019* | – | 0.026* |

| None/primary | 270 (38.2) | 92 (34.1) | 3.86 (1.42–10.52) | 0.008* | 3.29 (1.30–8.33) | 0.012* |

| Secondary | 263 (37.3) | 49 (18.6) | 2.65 (0.99–7.12) | 0.052 | 2.29 (0.90–5.83) | NS |

| College/university | 173 (24.5) | 7 (4.0) | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| Income level, MYR | – | – | – | 0.497 | – | – |

| < 3,000 | 591 (83.7) | 134 (22.7) | 0.70 (0.19–2.63) | 0.595 | – | – |

| 3,000–6,000 | 73 (10.3) | 10 (13.7) | 1.23 (0.32–4.65) | 0.762 | – | – |

| 6,000–10,000 | 42 (5.9) | 4 (9.5) | Reference | – | – | – |

| House within 5-km radius of jungle | ||||||

| Yes | 586 (83.0) | 129 (22.0) | 0.67 (0.34–1.32) | 0.248 | – | – |

| No | 120 (17.0) | 19 (15.8) | Reference | – | – | – |

NS = not significant; OR = odds ratio; MYR = Malaysian Ringgit.

Significant at P < 0.05.

Significant at P < 0.001.

Table 1.

Geographic distribution of study sites in Malaysia

| Provinces | District | Capital | Study site | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perak | Batang Padang | Tapah | Site A | Lat. 4°00′639″N, long. 101°20′516″E |

| – | – | Site B | Lat. 4°14′017″N, long. 101°20′747″E | |

| Pahang | Bentong | Bentong | Residential areas | Lat. 3°31′128″N, long. 101°55′089″E |

| – | – | Secondary school | Lat. 3°29′994″N, long. 101°54′665″E | |

| Sabah | Kota Kinabalu | Kota Kinabalu | Pulau Gaya | Lat. 6°01′288″N, long. 116°01′815″E |

| – | – | Telipok | Lat. 6°10′554″N, long. 116°27′889″E | |

| – | – | University | Lat. 6°01′866″N, long. 116°06′989″E | |

| Ranau | Ranau | Ranau | Lat. 5°57′274″N, long. 116°39′837″E | |

| Sandakan | Sandakan | Site C | Lat. 5°48′615″N, long. 117°59′733″E | |

| – | – | Segaliud | Lat. 5°50′195″N, long. 117°47′640″E |

Data collection.

Data records from the study volunteers were obtained from sample collectors and were kept in a spreadsheet file. Retrieved data included sample number, demographic information, socioeconomic status, and household attribute data. The study volunteers’ personal information was kept anonymous from their serum samples, which were replaced with a sample code (e.g., UKM-BP-001). Datasets such as names, personal identification (such as through national identification numbers), and contact numbers were excluded from the study. The demographic data included were gender and age; age was divided into five groups to compare Zika seropositivity among age groups. The number of participants categorized into these groups was equally distributed. Under household attributes, information about the household size, study site, state, and houses within a 5-km radius of the jungle was included. In addition, socioeconomic status covered information about education levels and income levels. Both variables were classified into three groups representing low, average, and high education/income levels.

Serological detection of anti-ZIKV IgG antibodies.

Anti-ZIKV IgG ELISA kits (Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany) were used to detect the presence of anti-ZIKV IgG antibodies in all serum samples. Detection was based on the coated recombinant ZIKV NS1 protein, and the test was conducted according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Cell line and ZIKV for neutralization test.

Cells obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, USA) were used and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Media (Gibco, USA), 1× nonessential amino acid (Gibco, USA), and 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco, USA). Flasks with Vero cells (CCL-81) were cultured at 37°C in 5% carbon dioxide in an incubator. Strain P6-740 was obtained from Dr. Robert Tesh (World Reference Center for Emerging Viruses and Arboviruses, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX). Viral stocks from tissue culture passage 4 were used, whereas viral titer was determined using a foci-forming assay.

Foci reduction neutralization test.

The foci reduction neutralization test (FRNT) was used as the gold standard to confirm the presence of ZIKV neutralizing antibodies in the serum samples. A subset of serum samples was tested using an FRNT. The FRNT was implemented as described previously,17,24,30 but was modified using mouse anti-ZIKV NS1 monoclonal antibody and a secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP) antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) to improve specificity. Neutralization was defined as the serum dilution that induced a 90% reduction in the number of virus-induced foci (FRNT90) compared with the controls wells (virus control and negative control). The number of foci was calculated manually under a phase-contrast microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Germany). Serum dilution was performed in a final dilution of 1:40 (200 μL) after adding an equivalent volume of virus (100 foci forming unit; 200 μL). Infected cells were stained using the 3,3'-diaminobenzidine method described elsewhere for DENV.31–33 The recommended lower limit for the PRNT90 titer was defined by the WHO as 20 for flavivirus plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT) application.34

Definition.

A sample was defined as Zika seropositive in our study if it was reactive using the anti-ZIKV NS1 ELISA kit (Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany) and had a ZIKV FRNT90 titer ≥ 1:40.

Bias.

Selection bias might be present because the target population came from lower socioeconomic groups. In addition, the misallocation bias required greater attention because only the anti-ZIKV IgG ELISA kit (Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany) and ZIKV FRNT were used, without other differential tests from other flaviviruses. Although all the recruited participants were asymptomatic, the concern of past infection from other flaviviruses that could not distinguish between ZIKV and other flaviviruses remains. FRNT is the current gold standard to differentiate infections; however, it is laborious to perform FRNT for all the flaviviruses present in Malaysia.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). The crude odds ratio (OR) analysis was performed to determine the association between Zika seropositivity and various sociodemographic factors using logistic regression. Factors found to be significant in the univariate analysis were used further for multivariate analysis. The 95% CIs were also calculated, and values of P < 0.05 were considered significant for all statistical analyses. All the demographic information and ELISA results were available only to researchers who performed the tests and read the ELISA and FRNT results. This study was conducted in compliance with the standardized protocol for cross-sectional seroprevalence studies of ZIKV infection in the general population, as found in WHO and Institute Pasteur guidelines.35

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study population.

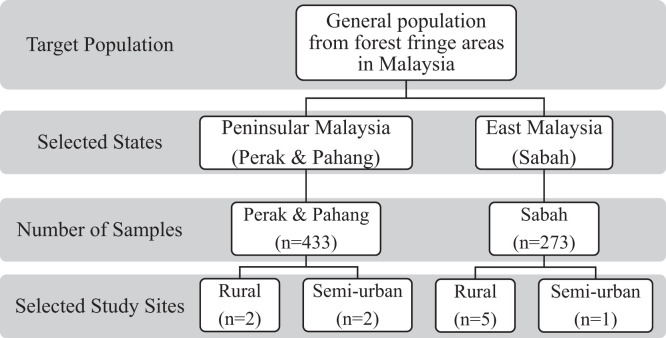

To determine the seroprevalence of Zika among the forest fringe communities, the proportion of potentially eligible participants in the study population was as shown in Figure 2. The study enrolled 706 participants: 433 individuals from Peninsular Malaysia (Perak and Pahang) and 273 from Sabah. The median age of the participants was 39 years (with 59% ≥ 35 years), and more than half (n = 488, 69.1%) were female (Table 2). The number of people living in a house was classified under household size, with 62.6% of participants (n = 442) having less than five people in a house. The study involved residents from five districts in Perak, Pahang, and Sabah. The participants were predominantly from forest fringe areas across the Tapah (Site B and A–Perak), Bentong (Pahang), Ranau (Sabah), Sandakan (Sabah), and Kota Kinabalu (Sabah) districts. As detailed in Tables 2 and 3, 83.0% (n = 586) of the participants’ houses were within a 5-km radius of the jungle. Most of the participants were from the low-income-level group (< Malaysian Ringgit 3,000; n = 591, 83.7%). Sixty-two percent of them (n = 436) had at least a secondary school level of education in Peninsular Malaysia or Sabah.

Figure 2.

Representation of study samples and target population.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics and seroprevalence status of participants in Peninsular Malaysia and Sabah (N = 706)

| Characteristics | n (%) | Seropositive* (N = 148), n (%) | Seronegative (N = 558), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group, y | |||

| 18–24 | 152 (21.5) | 14 (9.2) | 138 (90.8) |

| 25–34 | 139 (19.7) | 18 (12.9) | 121 (87.1) |

| 35–44 | 141 (20.0) | 27 (19.1) | 114 (80.9) |

| 45–54 | 133 (18.8) | 35 (26.3) | 98 (73.7) |

| > 54 | 141 (20.0) | 54 (38.3) | 87 (61.7) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 218 (30.9) | 50 (22.9) | 168 (77.1) |

| Female | 488 (69.1) | 98 (20.1) | 390 (79.9) |

| Size of household | |||

| < 5 | 442 (62.6) | 90 (20.4) | 352 (79.6) |

| > 5 | 264 (37.4) | 58 (22.0) | 206 (78.0) |

| Study site | |||

| Site A (rural) | 137 (19.4) | 24 (17.5) | 113 (82.5) |

| Site B (rural) | 94 (13.3) | 22 (23.4) | 72 (76.6) |

| Bentong residential areas (semi-urban) | 109 (15.4) | 13 (11.9) | 96 (88.1) |

| Secondary school (semi-urban) | 93 (13.2) | 1 (1.1) | 92 (98.9) |

| Pulau Gaya (rural) | 43 (6.1) | 22 (51.2) | 21 (48.8) |

| Telipok (rural) | 27 (3.8) | 6 (22.2) | 21 (77.8) |

| University (semi-urban) | 79 (11.2) | 33 (41.8) | 46 (58.2) |

| Ranau (rural) | 24 (3.4) | 9 (37.5) | 15 (62.5) |

| Site C (rural) | 48 (6.8) | 7 (14.6) | 41 (85.4) |

| Segaliud (rural) | 52 (7.4) | 11 (21.2) | 41 (78.8) |

| State | |||

| Perak | 231 (32.7) | 46 (19.9) | 185 (80.1) |

| Pahang | 202 (28.6) | 14 (6.9) | 188 (93.1) |

| Sabah | 273 (38.7) | 88 (32.2) | 185 (67.8) |

| Education level | |||

| None/primary | 270 (38.2) | 92 (34.1) | 178 (65.9) |

| Secondary | 263 (37.3) | 49 (18.6) | 214 (81.4) |

| College/university | 173 (24.5) | 7 (4.0) | 166 (96.0) |

| Income level, MYR | |||

| < 3,000 | 591 (83.7) | 134 (22.7) | 457 (77.3) |

| 3,000–6,000 | 73 (10.3) | 10 (13.7) | 63 (86.3) |

| 6,000–10,000 | 42 (5.9) | 4 (9.5) | 38 (90.5) |

| House within 5-km radius of jungle | |||

| Yes | 586 (83.0) | 129 (22.0) | 457 (78.0) |

| No | 120 (17.0) | 19 (15.8) | 101 (84.2) |

MYR = Malaysia Ringgit.

Subset of positive and borderline samples with a foci reduction neutralization test that induced a 90% reduction in the number of virus-induced foci ≥ 1:40.

Seroprevalence of ZIKV infection in Peninsular Malaysia and Sabah.

Serological evidence of past ZIKV infection, as denoted by a positive anti-ZIKV IgG ELISA result, revealed that 30.3% of the study volunteers (214 of 706 samples) were seropositive. Among the serum samples, 113 of 433 participants (26.1%) from Peninsular Malaysia and 101 of 273 participants (37.0%) from Sabah were seropositive. All the positive and equivocal samples were tested with a more stringent ZIKV FRNT90 titer value of ≥ 1:40 to reduce cross-reactivity with other flaviviruses. The results revealed the presence of false-positive samples caused by cross-reactivity with other flaviviruses. In addition, a total of 16 serum samples with equivocal results from participants from Peninsular Malaysia (n = 4) and Sabah (n = 12) also exhibited neutralizing antibodies against ZIKV. Overall, 53.1% (n = 60) and 87.1% (n = 88) of the serum samples had neutralizing antibodies against ZIKV in Peninsular Malaysia and Sabah, respectively (Supplemental Table S3). Total Zika seropositivity was 21.0% (n = 148) in Peninsular Malaysia and Sabah, which was confirmed using the FRNT. Therefore, both positive and equivocal results are equally important and must be interpreted carefully to avoid misclassification resulting from past ZIKV infection.

Factors associated with Zika seroprevalence.

The univariate and multivariate analyses were tabulated, and a comparison between the participants with and without past ZIKV infection is shown in Table 2. Univariate analysis of the investigated predictors showed that Zika seroprevalence was associated significantly with age group, study site or state, and education level. Multivariate analysis showed that increasing age per year (OR, 3.81; 95% CI, 1.81–8.01; P < 0.001) and lower educational level (OR, 3.29; 95% CI, 1.30–8.33; P = 0.012) were associated significantly with Zika seroprevalence. Furthermore, residents of Segaliud in Sabah (OR, 3.50; 95% CI, 1.75–6.97; P < 0.001) and students from Pahang (OR, 3.42; 95% CI, 1.55–7.52; P = 0.002) were more likely to be seropositive than residents of other study sites, indicating the greater risk of exposure and site of transmission of ZIKV in these areas.

DISCUSSION

Zika outbreaks continue to pose a major public health concern in view of increasing morbidity and mortality in the Asian-Pacific region during the past few decades. The virus is borderless, with evidence of imported cases from Singapore to Malaysia, and an exported case among tourists returning from Sabah, Malaysia.15,36 The prognostic factor for pandemic spread is currently unknown; therefore, it is crucial to identify ZIKV transmission through the serostatus of the general population in Malaysia because a recent outbreak in Malaysia has not been reported.

This study reports that seroprevalence results among the forest fringe communities was 21.0% (n = 148) after testing with the FRNT confirmation assay. The presence of neutralizing antibodies provides evidence that the studied forest fringe communities in Malaysia had been exposed to ZIKV. The higher seroprevalence rate in this study mirrors another nationwide cross-sectional study conducted in Malaysia in which 13.2% of the healthy population from rural areas were ZIKV seropositive.24 However, studies conducted among the urban population from the University of Malaya Medical Center reported a lower rate of 3.3%.30 Because different study sites and populations were involved in our study, different seroprevalence rates would be expected. For instance, the seroprevalence rates in our study were higher than those among adults in Vietnam (0.2%),37 Laos (10.2%),38 Taiwan (4.2%),39 and Kenya (0.2%),40 whereas countries such as Brazil (62.5%)41 and Suriname (35.1%)42 have reported higher rates of exposure to ZIKV.

In 2016, only eight clinical Zika cases were reported in Malaysia, based on the official system of notification obtained from the Ministry of Health.15 Despite the low ZIKV incidence in Malaysia, an overwhelming 21% of the participants in our study (n = 148) had serological evidence of past ZIKV exposure. Several theories may explain this discrepancy. First, the Zika notification system in Malaysia is based on passive reporting. Thus, it may not reflect the actual disease burden as a result of underreporting, misreporting,43,44 and failure to capture subclinical infections because of its similarity to DENV with regard to clinical presentation.45 Second, most Zika cases would have been missed because of the asymptomatic nature of the infection, because they involved only minimal symptoms and did not necessitate medical attention or hospitalization.

Another possibility is that ZIKV is likely to be related to cross-reactivity to DENV resulting from endemicity in the country. A previous study reported that antibodies reacted to the DENV envelope protein, which then drove antibody-dependent enhancement of ZIKV infection, potentially increasing the risk of ZIKV infections.46 In addition, a similar antibody response has been observed from community participants in Brazil and Mexico.47 The findings showed that high neutralizing responses to ZIKV envelope domain 3 are associated with preexisting reactivity to DENV1 envelope domain 3, which could alter host responses and susceptibility to ZIKV.47 However, this antibody response was unspecific and not persistent.47 In contrast, other studies showed that some plasma from DENV-infected patients could neutralize ZIKV and does not induce ZIKV infection.48 Although the role of preexisting anti-DENV against ZIKV is not well understood, this possible explanation for the increased rate of Zika seroprevalence cannot be neglected. It is a significant concern because the rural population in Malaysia with dengue seropositivity reportedly exceeded 80.0% in 2015,25 a rate that was estimated to have reached similarly high levels in urban areas (> 90.0%).49 Hence, to reduce the background serum cross-reactivity among flaviviruses, the more stringent FRNT90 titers were used in our study.50 A Zika seroprevalence study in Vietnam showed that PRNT90 was superior to PRNT50 in reducing the background serum cross-reactivity among flaviviruses.37 In addition, a similar threshold titer of 40 was used for seropositivity samples, as recommended by the French National Reference Center for Arboviruses. In previous Zika seroprevalence studies, the strategy of combining ELISA and neutralization testing has been used in Bolivia,51 Laos,38 Martinique Island,16 and Cameroon.52 Evidence showed that this strategy yielded high specificity and sensitivity values greater than 90% when using serum samples from Martinique Island (population dengue seroprevalence, > 90%).53 Thus, this strategy is very useful for Zika seroprevalence studies in dengue-endemic areas.

In our study, gender was not an associated factor for Zika seroprevalence; however, seropositivity correlated to increasing age, particularly in those in their late 40s and 50s. Because the antibody of past ZIKV infection is long-lasting, its detection window is longer. Another explanation for an increasing seropositive rate with increasing age is that the older population is likely to have experienced more ZIKV infections throughout their lifetime. Earlier studies conducted in 1963 revealed the prevalence of Zika (75.0%) among rural ethnic Indians in Selangor and Malaysia,54 whereas in Hong Kong in 1979, 4.6% of individuals were detected as ZIKV positive.55 Both studies did not report the associated factors for seropositivity; however, among those with gender and age information, females had greater seroprevalence than males, whereas most of the men older than 40 years were positive.54,55 In more recent studies, the association of ZIKV infection with age was also reported in Southeast Asia. A significant increase in Zika seropositivity was observed in Laos among a younger group (< 25 years old).38 Moreover, age group was also one of the predictors for being Zika seropositive in Vietnam, with a greater risk reported among people older than 30 years.37 The increased risk of infection, especially in women in this childbearing age group, may imply that the number of adverse congenital outcomes resulting from a Zika outbreak will be greater than expected.56

A greater number of seropositive cases was also observed among the group with a low level of education. In most participants with lower socioeconomic status, rural poverty is still prevalent, particularly in terms of their limited access to medical care. Because poverty is associated with poor dietary habits, forest fringe communities are likely to have a poor nutritional status.57,58 Moreover, a lower education level will result in a lower standard of living conditions and hygiene,58 which leads to a greater risk of exposure to various zoonotic diseases. Earlier studies identified the high seroprevalence of Leptospira (57.9%),59 Nipah virus infection (10.7%),60 and toxoplasmosis (37.0%)61 among forest fringe communities in Malaysia. These socioeconomic factors are the potential predictors driving forest fringe communities’ greater risk of exposure to various zoonotic diseases, including Zika. In contrast, one study reported that parents with low socioeconomic status have the same high expectations for their children’s education as those with high socioeconomic status.62 Those in forest fringe communities who receive tertiary education would have to move to another place because there are no universities in forest fringe regions.37 Hence, they do not live in their villages for some years, resulting in a lower seroprevalence rate among those with a higher education level. Abd-Jamil et al.27 suggested that better access to health care and education could be important in curbing the spread of the disease. In addition, another study suggested the development of Zika educational materials for schools in the Philippines.63 This could be one of the ways to prevent ZIKV transmission through students who can then disseminate the knowledge gained at school to their respective families and communities.63

Analyzing data related to Zika seroprevalence in Perak, Pahang, and Sabah, a higher seropositivity rate was reported in Sabah. This higher seropositivity rate in Sabah might be explained by the greater number of indigenous people living in Sabah. As reported previously, 58.6% of Sabah’s population includes indigenous people, whereas only 0.7% of Peninsular Malaysia’s population includes indigenous people.20 The greater number of indigenous people revealed that more people live beneath the poverty line in Sabah, which linked back to the association of Zika seropositivity with lower socioeconomic status. In addition, individuals in Sabah with no history of traveling to other states were found to be positive for ZIKV.36 This suggests the presence of ZIKV in the state has been grossly underreported. However, most risk factors may also be specific to study sites, and they warrant further investigation.

When comparing sites from Peninsular Malaysia and Sabah, our site-based analysis revealed that in both Peninsular Malaysia and Sabah, the common predictor for ZIKV infections was based on age groups, and was significant for the age group that included those 45 years and older. There was also a significant difference in Zika seroprevalence across the study sites, ranging from 1.1% in secondary school students to 21.2% in Segaliud residents. Specifically, the seropositive rates were 3.42 times and 3.50 times higher in the secondary school students from Bentong, Pahang, and the community from Segaliud, Sabah, respectively. Upon comparing these two groups, they are from two different age groups and represent two distinct communities. The age group may be the risk factor for Zika seroprevalence in Segaliud, a community that comprises older residents. This corroborates findings that the elderly have a lower level of knowledge about ZIKV transmission or prevention. The observed greater Zika seroprevalence among school students could be a cause for concern because the school could be the primary site of exposure to the Aedes vector.64 In a study by Wilder-Smith et al,.65 an intervention to prevent the children from being exposed to infected Aedes mosquitoes was suggested.

Our study has limitations linked to the sampling population of the volunteers; the majority were from lower educational and income levels. This could create a biased representation of the seropositivity of ZIKV, which may therefore be underreported or overreported. This study was also limited by the small sample size, which used a few study sites in Sabah, and the challenges of conducting fieldwork during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is possible that the testing of these populations was not uniform, which may have affected the analysis of certain demographic factors such as gender or age. However, the differences are minimal, based on the total number of samples collected from the states; this will likely clarify the reliability of the actual seroprevalence rate. Another limitation of our study is not performing cross-neutralization testing with DENV, given the known cross-reactivity with other flaviviruses such as DENV, Japanese encephalitis virus, and yellow fever virus. It was not possible to perform screening for all viruses, because this would have been laborious and expensive, and it would also have eliminated serum samples that were also positive for ZIKV infection. This would create an underestimation of the real ZIKV seroprevalence. However, FRNTs were performed at the 90% cutoff on all IgG-positive sera to ensure that the detected antibodies were indeed specific to ZIKV. In addition, environmental factors such as rainfall, water management systems, and other potential risk factors that would influence the prevalence of Zika were not studied. Other immunological, biological, and virological factors may also have affected our findings, but assessment of these factors was beyond the scope of our study.

CONCLUSION

The seroprevalence results reported from our study of a specific population in Malaysia were 30.3% with ELISA and 21.0% (n = 148) after confirmation using an FRNT. A major ZIKV epidemic has never been reported in Malaysia; however, our study revealed that neutralizing antibodies against ZIKV from the study population showed the circulation of the virus in Peninsular Malaysia and Sabah. The risk of Zika seropositivity was found to be associated with age > 44 years and with education less than university level. Site-specific associations were also observed for secondary school students from Bentong (Pahang) and residents from Segaliud (Sabah). The elderly community represents the majority of the population, indicating a potential gap in surveillance and intervention. This could be beneficial in determining the future direction of research addressing knowledge gaps in many communities.

Supplemental files

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the sample collectors from University Kebangsaan Malaysia and University Malaysia Sabah for their hard work in the field, and study volunteers for their dedication to completing this study. The project was only completed successfully because of the highly coordinated efforts and commitment by all the members of the research team from three different institutions and their respective partners. They have given their support in every way, from field sampling work to laboratory analysis. We especially acknowledge the Jabatan Kemajuan Orang Asli and local health district offices from each study site for allowing access to the selected communities, and for providing the infrastructure and technical support in the field.

Note: Supplemental information, tables, and figures appear at www.ajtmh.org.

REFERENCES

- 1. Petersen LR, Jamieson DJ, Powers AM, Honein MA, 2016. Zika virus. N Engl J Med 374: 1552–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cao-Lormeau VM, Roche C, Teissier A, Robin E, Berry AL, Mallet HP, Sall AA, Musso D, 2014. Zika virus, French Polynesia, South Pacific, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis 20: 1085–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Duffy MR. et al. , 2009. Zika virus outbreak on Yap Island, Federated States of Micronesia. N Engl J Med 360: 2536–2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Campos GS, Bandeira AC, Sardi SI, 2015. Zika virus outbreak, Bahia, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis 21: 1885–1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lourenço J, de Lourdes Monteiro M, Valdez T, Monteiro Rodrigues J, Pybus O, Rodrigues Faria N, 2018. Epidemiology of the Zika virus outbreak in the Cabo Verde Islands, West Africa. PLoS Curr 10: ecurrents.outbreaks.19433b1e4d007451c691f138e1e67e8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schuler-Faccini L. et al. , 2016. Possible association between Zika virus infection and microcephaly: Brazil, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 65: 59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization , 2019. Zika Epidemiology Update. Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/zika/zika-epidemiology-update-july-2019.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2021.

- 8. Musso D, Ko AI, Baud D, 2019. Zika virus infection: after the pandemic. N Engl J Med 381: 1444–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marchette NJ, Garcia R, Rudnick A, 1969. Isolation of Zika virus from Aedes aegypti mosquitoes in Malaysia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 18: 411–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Malaysia Ministry of Health , 2019. Updated Zika Alert. Putrajaya, Malaysia: Malaysia Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mudin RN, 2015. Dengue incidence and the prevention and control program in Malaysia. IIUM Med J Malaysia 14: 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lam SK, Chua KB, Hooi PS, Rahimah MA, Kumari S, Tharmaratnam M, Chuah SK, Smith DW, Sampson IA, 2001. Chikungunya infection: an emerging disease in Malaysia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 32: 447–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Buathong R. et al. , 2015. Detection of Zika virus infection in Thailand, 2012–2014. Am J Trop Med Hyg 93: 380–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Singapore Zika Study Group , 2017. Outbreak of Zika virus infection in Singapore: an epidemiological, entomological, virological, and clinical analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 17: 813–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Woon YL, Lim MF, Tg Abd Rashid TR, Thayan R, Chidambaram SK, Syed Abdul Rahim SS, Mudin RN, Sivasampu S, 2019. Zika virus infection in Malaysia: an epidemiological, clinical and virological analysis. BMC Infect Dis 19: 152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gallian P, Cabié A, Richard P, Paturel L, Charrel RN, Pastorino B, Leparc-Goffart I, Tiberghien P, de Lamballerie X, 2017. Zika virus in asymptomatic blood donors in Martinique. Blood 129: 263–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ngwe Tun MM. et al. , 2018. Detection of Zika virus infection in Myanmar. Am J Trop Med Hyg 98: 868–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Reiter D, 2019. Zika Virus Returns to Malaysia. Zika News. Available at: https://www.zikanews.com/malaysian-perak-health-department-confirmed-man-has-been-infected-zika-virus. Accessed March 13, 2021.

- 19. Whiteman A. et al. , 2020. Do socioeconomic factors drive Aedes mosquito vectors and their arboviral diseases? A systematic review of dengue, chikungunya, yellow fever, and Zika virus. One Health 11: 100188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Khor GL, Shariff ZM, 2019. Do not neglect the indigenous peoples when reporting health and nutrition issues of the socio-economically disadvantaged populations in Malaysia. BMC Public Health 19: 1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tay ST, Mohamed Zan HA, Lim YAL, Ngui R, 2013. Antibody prevalence and factors associated with exposure to Orientia tsutsugamushi in different aboriginal subgroups in west Malaysia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 7: e2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dick GW, Kitchen SF, Haddow AJ, 1952. Zika virus: I. Isolations and serological specificity. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 46: 509–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wolfe ND, Kilbourn AM, Karesh WB, Rahman HA, Bosi EJ, Cropp BC, Andau M, Spielman A, Gubler DJ, 2001. Sylvatic transmission of arboviruses among Bornean orangutans. Am J Trop Med Hyg 64: 310–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Khor CS. et al. , 2019. Serological evidences of DENV, JEV and ZIKV among the indigenous people (Orang Asli) of Peninsular Malaysia. J Med Virol 92: 956–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dhanoa A. et al. , 2018. Seroprevalence of dengue among healthy adults in a rural community in southern Malaysia: a pilot study. Infect Dis Poverty 7: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tiong V, Abd-Jamil J, Mohamed Zan HA, Abu-Bakar RS, Ew CL, Jafar FL, Nellis S, Fauzi R, AbuBakar S, 2015. Evaluation of land cover and prevalence of dengue in Malaysia. Trop Biomed 32: 587–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Abd-Jamil J, Ngui R, Nellis S, Fauzi R, Lim ALY, Chinna K, Khor C-S, AbuBakar S, 2020. Possible factors influencing the seroprevalence of dengue among residents of the forest fringe areas of Peninsular Malaysia. J Trop Med 2020: 1019238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rabe IB, Staples JE, Villanueva J, Hummel KB, Johnson JA, Rose L, Hills S, Wasley A, Fischer M, Powers AM, 2016. Interim guidance for interpretation of Zika virus antibody test results. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 65: 543–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. World Health Organization , 2016. WHO Statement on the First Meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) (IHR 2005) Emergency Committee on Zika Virus and Observed Increase in Neurological Disorders and Neonatal Malformations. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2016/1st-emergency-committee-zika/en/. Accessed June 22, 2020.

- 30. Sam IC, Montoya M, Chua CL, Chan YF, Pastor A, Harris E, 2019. Low seroprevalence rates of Zika virus in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 113: 678–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Teoh B-T, Sam S-S, Tan K-K, Johari J, Shu M-H, Danlami MB, Abd-Jamil J, MatRahim N, Mahadi NM, AbuBakar S, 2013. Dengue virus type 1 clade replacement in recurring homotypic outbreaks. BMC Evol Biol 13: 213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tan KK, Nellis S, Zulkifle NI, Sulaiman S, AbuBakar S, 2018. Autochthonous spread of DENV-3 genotype III in Malaysia mitigated by pre-existing homotypic and heterotypic immunity. Epidemiol Infect 146: 1635–1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wong S-S, Abd-Jamil J, Abubakar S, 2007. Antibody neutralization and viral virulence in recurring Dengue virus type 2 outbreaks. Viral Immunol 20: 359–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. World Health Organization , 2016. Zika Virus Disease: Interim Case Definition. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/204381. Accessed April 9, 2020.

- 35. World Health Organization , Institut Pasteur , 2016. Standardized Protocol: Cross-sectional Seroprevalence Study of Zika Virus Infection in the General Population. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-ZIKV-PHR-16.1. Accessed January 22, 2020.

- 36. Tappe D, Nachtigall S, Kapaun A, Schnitzler P, Günther S, Schmidt-Chanasit J, 2015. Acute Zika virus infection after travel to Malaysian Borneo, September 2014. Emerg Infect Dis 21: 911–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nguyen CT. et al. , 2020. Prevalence of Zika virus neutralizing antibodies in healthy adults in Vietnam during and after the Zika virus epidemic season: a longitudinal population-based survey. BMC Infect Dis 20: 332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pastorino B, Sengvilaipaseuth O, Chanthongthip A, Vongsouvath M, Souksakhone C, Mayxay M, Thirion L, Newton PN, de Lamballerie X, Dubot-Pérès A, 2019. Low Zika virus seroprevalence in Vientiane, Laos, 2003–2015. Am J Trop Med Hyg 100: 639–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chien YW, Ho TC, Huang PW, Ko NY, Ko WC, Perng GC, 2019. Low seroprevalence of Zika virus infection among adults in southern Taiwan. BMC Infect Dis 19: 884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kisuya B, Masika MM, Bahizire E, Oyugi JO, 2019. Seroprevalence of Zika virus in selected regions in Kenya. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 113: 735–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Netto EM. et al. , 2017. High Zika virus seroprevalence in Salvador, northeastern Brazil limits the potential for further outbreaks. MBio 8: 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Langerak T. et al. , 2019. Zika virus seroprevalence in urban and rural areas of Suriname, 2017. J Infect Dis 220: 28–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lee BY, Alfaro-Murillo JA, Parpia AS, Asti L, Wedlock PT, Hotez PJ, Galvani AP, 2017. The potential economic burden of Zika in the continental United States. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11: e0005531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Malaysia Ministry of Health , 2021. Current Situation for Dengue, Zika and Chikungunya in Malaysia for 2021. Putrajaya, Malaysia: Malaysia Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Haby MM, Pinart M, Elias V, Reveiz L, 2018. Prevalence of asymptomatic Zika virus infection: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ 96: 402–413D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dejnirattisai W. et al. , 2016. Dengue virus sero-cross-reactivity drives antibody-dependent enhancement of infection with Zika virus. Nat Immunol 17: 1102–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Robbiani DF. et al. , 2017. Recurrent potent human neutralizing antibodies to Zika virus in Brazil and Mexico. Cell 169: 597–609.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Collins MH, McGowan E, Jadi R, Young E, Lopez CA, Baric RS, Lazear HM, de Silva AM, 2017. Lack of durable cross-neutralizing antibodies against Zika virus from Dengue virus infection. Emerg Infect Dis 23: 773–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chew CH. et al. , 2016. Rural–urban comparisons of dengue seroprevalence in Malaysia. BMC Public Health 16: 824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Roehrig JT, Hombach J, Barrett ADT, 2008. Guidelines for plaque-reduction neutralization testing of human antibodies to dengue viruses. Viral Immunol 21: 123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Saba Villarroel PM. et al. , 2018. Zika virus epidemiology in Bolivia: a seroprevalence study in volunteer blood donors. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 12: e0006239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gake B, Vernet MA, Leparc-Goffart I, Drexler JF, Gould EA, Gallian P, de Lamballerie X, 2017. Low seroprevalence of Zika virus in Cameroonian blood donors. Braz J Infect Dis 21: 481–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nurtop E. et al. , 2018. Combination of ELISA screening and seroneutralisation tests to expedite Zika virus seroprevalence studies. Virol J 15: 192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pond WL, 1963. Arthropod-borne virus antibodies in sera from residents of South-East Asia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 57: 364–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Johnson BK, Chanas AC, Gardner P, Simpson DI, Shortridge KF, 1979. Arbovirus antibodies in the human population of Hong Kong. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 73: 594–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Counotte MJ, Althaus CL, Low N, Riou J, 2019. Impact of age-specific immunity on the timing and burden of the next Zika virus outbreak. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 13: e0007978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shahar S, Vanoh D, Mat Ludin AF, Singh DKA, Hamid TA, 2019. Factors associated with poor socioeconomic status among Malaysian older adults: an analysis according to urban and rural settings. BMC Public Health 19: 549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Khor GL, Mohd Shariff Z, 2008. The Ecology of health and nutrition of “Orang Asli” (indigenous people) women and children in Peninsular Malaysia. Tribes Tribals 2: 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Loong SK, Khor CS, Chen HW, Chao CC, Ling ISC, Abdul Rahim NF, Hassan HS, Nellis S, Ching WM, AbuBakar S, 2018. Serological evidence of high Leptospira exposure among indigenous people (Orang Asli) in Peninsular Malaysia using a recombinant antigen-based ELISA. Trop Biomed 35: 1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yong M-Y, Lee S-C, Ngui R, Lim YA-L, Phipps ME, Chang L-Y, 2020. Seroprevalence of Nipah virus infection in Peninsular Malaysia. J Infect Dis 221: S370–S374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ngui R, Lim YAL, Amir NFH, Nissapatorn V, Mahmud R, 2011. Seroprevalence and sources of toxoplasmosis among Orang Asli (indigenous) communities in Peninsular Malaysia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 85: 660–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Vellymalay SKN, 2013. Relationship between Malay parents’ socioeconomic status and their involvement in their children’s education at home. J Soc Sci Hum 8: 90–108. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gregorio ER, Jr, Medina JRC, Lomboy M, Talaga ADP, Hernandez PMR, Kodama M, Kobayashi J, 2019. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of public secondary school teachers on Zika virus disease: a basis for the development of evidence-based Zika educational materials for schools in the Philippines. PLoS One 14: e0214515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ratanawong P, Kittayapong P, Olanratmanee P, Wilder-Smith A, Byass P, Tozan Y, Dambach P, Quiñonez CAM, Louis VR, 2016. Spatial variations in dengue transmission in schools in Thailand. PLoS One 11: e0161895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wilder-Smith A. et al. , 2012. DengueTools: innovative tools and strategies for the surveillance and control of dengue. Glob Health Action 5: 17273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.