SUMMARY

Class C β-lactamases or cephalosporinases can be classified into two functional groups (1, 1e) with considerable molecular variability (≤20% sequence identity). These enzymes are mostly encoded by chromosomal and inducible genes and are widespread among bacteria, including Proteobacteria in particular. Molecular identification is based principally on three catalytic motifs (64SXSK, 150YXN, 315KTG), but more than 70 conserved amino-acid residues (≥90%) have been identified, many close to these catalytic motifs. Nevertheless, the identification of a tiny, phylogenetically distant cluster (including enzymes from the genera Legionella, Bradyrhizobium, and Parachlamydia) has raised questions about the possible existence of a C2 subclass of β-lactamases, previously identified as serine hydrolases. In a context of the clinical emergence of extended-spectrum AmpC β-lactamases (ESACs), the genetic modifications observed in vivo and in vitro (point mutations, insertions, or deletions) during the evolution of these enzymes have mostly involved the Ω- and H-10/R2-loops, which vary considerably between genera, and, in some cases, the conserved triplet 150YXN. Furthermore, the conserved deletion of several amino-acid residues in opportunistic pathogenic species of Acinetobacter, such as A. baumannii, A. calcoaceticus, A. pittii and A. nosocomialis (deletion of residues 304–306), and in Hafnia alvei and H. paralvei (deletion of residues 289–290), provides support for the notion of natural ESACs. The emergence of higher levels of resistance to β-lactams, including carbapenems, and to inhibitors such as avibactam is a reality, as the enzymes responsible are subject to complex regulation encompassing several other genes (ampR, ampD, ampG, etc.). Combinations of resistance mechanisms may therefore be at work, including overproduction or change in permeability, with the loss of porins and/or activation of efflux systems.

KEYWORDS: AmpC β-lactamases, cephalosporinases, ESAC, extended-spectrum, phylogeny, primary structure

INTRODUCTION

β-lactamases remain an important natural or acquired mechanism of resistance to β-lactam antibiotics. New enzymes of this type, belonging to the molecular classes defined by Ambler and then completed by several authors (1–3), have been regularly discovered since the 1980s. The class C β-lactamases (BLCs), also known as AmpC or cephalosporinases, have a long history marked by the gradual loss of efficacy for the treatment of many bacterial infections, due initially to their large inactivation spectrum, including penicillins, the first cephalosporins (e.g., cephalothin), and cephamycins (e.g., cefoxitin), together with the general absence of an inhibitory effect of clavulanic acid, sulbactam, and tazobactam (4–6). The next problem encountered was the emergence of constitutive or overproduced mutants, eventually overcome by the development of oxyiminocephalosporins, such as cefotaxime and ceftazidime (7). However, plasmid-borne cephalosporinases were subsequently discovered, particularly in species without chromosomal ampC genes (e.g., Klebsiella pneumoniae, Salmonella enterica, and Proteus mirabilis) and in Escherichia coli, which possesses an intrinsic ampC gene usually not expressed. These enzymes are derived from chromosomally encoded enzymes specific to other species, such as Enterobacter cloacae and Citrobacter freundii, and their discovery raised new fears, allayed by the discovery of cefepime and cefpirome (4, 8). However, a new step in resistance development was then detected, with the discovery of extended-spectrum β-lactamases AmpC (ESAC), mutants or variants with an extended inactivation spectrum for oxyiminocephalosporins (ceftazidime, cefotaxime, cefepime, and cefpirome) due to the mutation of certain sites, in the R2-loop (9, 10), for example, by substitution, deletion, or insertion. Carbapenem resistance mediated by a combination of mechanisms, including a constitutive species-specific cephalosporinase and porin loss, has emerged more recently (11, 12). Finally, the recent development of novel enzyme inhibitors, such as avibactam, has elicited considerable medical interest due to its ability to inhibit serine β-lactamases (classes A, C, and D). However, this has already led to the selection of clinical mutants resistant to ceftazidime–avibactam combinations, most of them bearing deletions of various sizes in the Ω-loop region of AmpC (13, 14), similarly to β-lactamases from other classes (e.g., KPC-3).

Various methods for detecting resistant clinical isolates have been proposed, particularly for resistance to oxyiminocephalosporins and carbapenems. These methods include phenotypic tests, enzymatic methods based on hydrolysis, immunochromatographic assays, and molecular tests designed to test for the presence of particular genes, encoding class C β-lactamases, for example (15). Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) is a very useful approach for the precise identification of mechanisms of resistance to β-lactams, and has provided a large body of sequence data. Nevertheless, genotype-to-phenotype extrapolations are not straightforward, due to the variability of gene expression and polymorphisms linked to silent mutations at diverse sites, depending on the β-lactamase considered (16). Improvements in our knowledge should make it possible to improve analyses of the resistance mechanisms detected, particularly against β-lactams, in the future. These mechanisms are numerous and differ considerably between species. The current classification of β-lactamases into four molecular classes is based on motifs involved in binding and hydrolysis, such as 70SXXK, 130SDN, and 234KTG for class A (17), and on diverse residues involved in determining affinity, either increasing the inactivation spectrum (e.g., ESBLs) or decreasing it (e.g., IRT) (18–20). A more detailed comparative analysis of the primary structure of a large number of proteins would facilitate the classification of enzymes into groups of clusters displaying common structural features, as for the enzymes of class A (21). BLCs seem to have a lower level of structural diversity, but the abundance of data now available in databases (e.g., Beta-Lactamase DataBase [BLDB, http://bldb.eu/] [22], Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance Reference Gene Database [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/313047] [23], CARD [https://card.mcmaster.ca/] [24]) suggests that a more detailed analytical approach, based on several thousand sequences, would now be justified.

When we began this analysis in 2019, several numbering schemes had been proposed for class C β-lactamases, which were unified in a standardized structure-based numbering scheme published in 2020 (25). Accurate comparisons of protein sequences have improved structural classification, by providing a clearer identification of polymorphisms by species, a more precise identification of the bacterium updated in line with the continual changes in taxonomy, a better understanding of the residues or zones involved in the possible extension of the inactivation spectrum by species or bacterial group, and with respect to both substrates and enzyme inhibitors, such as avibactam. The ACC-type β-lactamases appeared to be plasmid-encoded enzymes originating from Hafnia alvei with an unusual susceptibility pattern characterized by resistance to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins such as ceftazidime, cefotaxime, and, sometimes, cefpirome, and by susceptibility to cefepime and inhibition by cefoxitin (see the section on Natural ESACs for more details).

PHYLOGENETIC COMPARISON

The serine β-lactamases have been divided into three classes (A, C, and D) based on sequence similarity (1, 2, 26). A protein structure-based phylogeny clearly distinguished between these classes (27–29). The amino acid-based phylogenetic tree based on 3,943 class C sequences reveals large differences between the major groups (Acinetobacter, Aeromonadales, Burkholderiales, Enterobacterales, Pseudomonadales, Rhizobiales), each of which displays at least 24% amino-acid sequence identity (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

(A) Phylogram for representative and putative class C β-lactamases, compared with β-lactamases from classes A, B, and D. (B) Focused view on the phylogram of class C β-lactamases. The protein sequences of representative enzymes are listed in references 33, 47, 54, and 64. The sequences were filtered using CD-HIT (https://github.com/weizhongli/cdhit) at 90% sequence identity, then aligned with Clustal Omega (319). The tree was constructed using RAxML (320), and the phylogram generated using FigTree (version 1.4.3). The tree was unrooted.

Highly conserved and major clusters, including many variants displaying >75% sequence identity with each other, were found for the following genera: Escherichia/Shigella, Citrobacter, Enterobacter, Hafnia, Klebsiella, Morganella, Serratia. Other clusters (Acinetobacter, Aeromonas, Burkholderia, Erwinia, Pseudomonas, Rhizobium, Yersinia, etc.) are less conserved, with a percent amino-acid identity between sequences of less than 50%. These findings highlight the need for more accurate taxonomic approaches in the future. Sequences from the Proteobacteria were particularly prevalent, but BLCs were widely distributed between bacterial groups, with the exception of Gram-positive bacteria, in which they were rare (Table 1) (28, 29). Finally, a separate cluster including several genera (e.g., Bradyrhizobium, Legionella, Parachlamydia) was identified and found to contain generic serine hydrolases and some carboxylesterases VIII with weak β-lactamase activity (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Overview of bacteria producing class C β-lactamases

| Class | Order | Genus |

|---|---|---|

| Alphaproteobacteria | Rhizobiales | Agrobacterium, Bosea, Bradyrhizobium, Inorhizobium, Mesorhizobium, Methylobacterium, Microvirga, Ochrobactrum, Phyllobacterium, Pseudorhodoplanes, Rhizobium |

| Rhodobacterales | Rhodobacter, Ruegeria, Silicibacter, Sulfitobacter | |

| Rhodospirillales | Dongia | |

| Betaproteobacteria | Burkholderiales | Achromobacter, Bordetella, Burkholderia, Caballeronia, Collimonas, Cupriavidus, Herbaspirillum, Janthinobacterium, Massilia, Noviherbaspirillum, Pandoraea, Paraburkholderia |

| Neisseriales | Chromobacterium, Laribacter, Snodgrassella | |

| Rhodocyclales | Thauera | |

| Gammaproteobacteria | Aeromonadales | Aeromonas |

| Alteromonadales | Shewanella | |

| Cellvibrionales | Microbulbifer | |

| Enterobacterales | Budvicia, Buttiauxella, Cedecea, Citrobacter, Cronobacter, Edwardsiella, Enterobacter, Erwinia, Escherichia:Shigella, Ewingella, Hafnia, Klebsiella, Lelliottia, Morganella, Pantoea, Photorhabdus, Pluralibacter, Pragia, Providencia, Regiella, Rouxiella, Serratia, Siccibacter, Xenorhabdus, Yersinia | |

| Legionellales | Legionella | |

| Oceanospirillales | Aidingimonas, Chromohalobacter, Halomonas, Salinicola | |

| Pseudomonadales | Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, Psychrobacter | |

| Vibrionales | Vibrio | |

| Xanthomonadales | Dyella, Lysobacter, Xanthomonas | |

| Deltaproteobacteria | Myxococcales | Myxococcus |

| Terrabacteria | Actinobacteria | Mycobacterium |

| Negativicutes | Pelosinus | |

| FCB group | Chitinophagales | Sediminibacterium |

| Cytophagales | Dyadobacter, Emticicia, Siphonobacter | |

| Flavobacteriales | Chryseobacterium | |

| Sphingobacteriales | Sphingobacterium | |

| PVC group | Chlamydiales | Chlamydia |

| Parachlamydiales | Parachlamydia | |

| Unclassified | Dependentiae |

PRIMARY STRUCTURE/SEQUENCE ANALYSIS

Highly Conserved Motifs and Residues

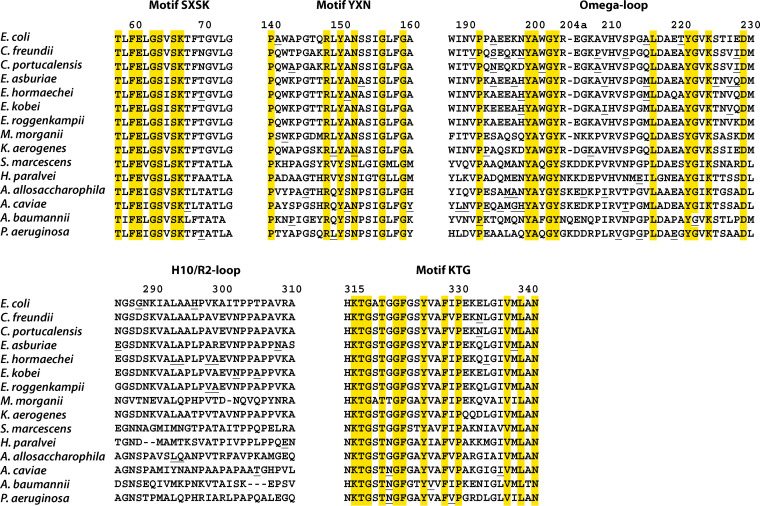

A standardized amino-acid numbering scheme was recently developed, through collaboration, for class C β-lactamases (25). This numbering scheme has greatly facilitated molecular comparisons between class C enzymes. Indeed, “SANC” (structural alignment-based numbering of class C β-lactamases) preserves the usual numbering of the major catalytic residues (64S, 67K, 150Y, and 315K). Three highly conserved motifs are currently used to characterize this molecular class (64SXSK, 150YXN, and 315KTG) (17, 28), but other conserved residues have been characterized and can be used for the more accurate identification of AmpC enzymes (Tables 2 and 3). They include 37 residues strictly conserved (100%) and 33 residues highly conserved (90–97%) in a data set of 32 representative class C β-lactamases examined in a previous study (25). Proline (P) and aromatic (F, W, Y) residues are overrepresented at these positions compared to class A β-lactamases. Indeed, prolines are present at positions 18, 26, 94, 118, 122, 140, 192, 213, 277, 330, and 345 for class C β-lactamases, but only at positions 107, 183, and 226 for class A β-lactamases. Similarly, strictly conserved aromatic residues are present at positions 60, 138, 150, 199, 203, 221, 271, 322, 325, and 328 for class C β-lactamases, but only at positions 66, 210, and 229 for class A β-lactamases. If aromatic amino acids (F, Y and W) are considered together, as a single category, additional conserved positions emerge for BLCs: 43, 69, 134, 135, 170, 188, 233, 260, 276, and 344 (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Representative class C β-lactamases

| Bla | Origin of namec | Accession no. | Genomic localizationa | Organism | No. of residues | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACC-1 | Ambler Class C-1 | AJ133121 | P | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 386 | 321 |

| ACT-1 | AmpC Type | U58495 | P | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 381 | 322 |

| ABA-1 (ADC-2) | Acinetobacter baumannii | AY177427 | IS | Oligella urethralis | 383 | 323 |

| ABAC-1 (ADC-3) | Acinetobacter baumannii Class C | AY178995 | Chr | Acinetobacter baumannii | 383 | 323 |

| ADC-1 | Acinetobacter-derived cephalosporinase | AJ009979 | Chr | Acinetobacter baumannii | 383 | 247 |

| AQU-1 | Aeromonas aquariorum | AB765393 | Chr | Aeromonas dhakensis | 380 | 249 |

| AsbA1 | Aeromonas so bria | U10250 | In | Aeromonas jandaei | 381 | 324 |

| BIL-1 (CMY-2-like) | Name of patient (Bilal) | X74512 | P | Escherichia coli | 383 | 325, 326 |

| BlaE | Gene name | AY442183 | Chr | Mycobacterium smegmatis | 380 | 327, 328 |

| BUT-1 | Buttiauxella sp. | AJ415568 | Chr | Buttiauxella sp. | 383 | 329 |

| CAV-1 | Aeromonas caviae | AF462690 | Chr | Aeromonas caviae | 382 | 44 |

| CDA-1 | Cedecea davisae | KJ650399 | Chr | Cedecea davisae | 382 | 330 |

| CepH | Cephalosporinase hydrophila | AJ276030 | Chr | Aeromonas hydrophila | 382 | 41 |

| CepS | Cephalosporinase sobria | X80277 | Chr | Aeromonas sobria | 382 | 331 |

| CFE-1 | Citrobacter fr eundii | AB107899 | P | Escherichia coli | 381 | 208 |

| CHR-1 | Chromohalobacter sp. | AB070219 | Chr | Chromohalobacter sp. | 396 | 169, 332 |

| CMA-1 | Cronobacter malonaticus | KF640251 | Chr | Cronobacter malonaticus | 375 | 333 |

| CMH-1 | Chi Mei Hospital | JQ673557 | P | Enterobacter cloacae | 381 | 334 |

| CMY-1 | Active on cephamycins | X92508 | P | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 382 | 233 |

| CMY-2 | Active on cephamycins | X91840 | P | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 381 | 335 |

| CSA-1 | Cronobacter sakazakii | KF623543 | Chr | Cronobacter sakazakii | 375 | 333 |

| DHA-1 | Dhahran (Saudi Arabia) | Y16410 | P | Salmonella enteritidis | 379 | 336, 337 |

| Ear-1 | Enterobacter ae rogenes | AJ544162 | Chr | Enterobacter aerogenes | 381 | 338 |

| EDC-1 | Edwardsiella AmpC | EF467366 | Chr | Edwardsiella tarda | 386 | – |

| ENT-1 | Buttiauxella agrestis CF01Ent1 | AJ489827 | Chr | Buttiauxella agrestis | 390 | 339 |

| ERH-1 | Erwinia rhapontici | AY288518 | Chr | Erwinia rhapontici | 379 | 340 |

| FOX-1 | Active on cefoxitin | X77455 | P | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 382 | 341 |

| IDC-1 | Integron derived cephalosporinase | MN985649 | In | sediment metagenome | 395 | 31 |

| K12 (EC-1) | Escherichia coli K12 | J01611 | Chr | Escherichia coli | 377 | 342, 343 |

| LAT-1 | Active on latamoxef | X78117 | P | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 381 | 344, 345 |

| LHK-1 | Laribacter hongkongensis | AY632070 | Chr | Laribacter hongkongensis | 388 | 346 |

| LRA10-1 | β-lactam resistance from Alaska | EU408357 | – | uncultured bacteria (soil) | 375 | 30 |

| LRA13-1b | β-lactam resistance from Alaska | EU408352 | – | uncultured bacteria (soil) | 609b | 30 |

| LRA18-1 | β-lactam resistance from Alaska | EU408355 | – | uncultured bacteria (soil) | 386 | 30 |

| LYL-1 | Lysobacter lactamgenus | X56660 | Chr | Lysobacter lactamgenus | 385 | 347 |

| MIR-1 | Miriam hospital | M37839 | P | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 381 | 348, 349 |

| MOX-1 | Active on moxalactam | D13304 | P | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 382 | 232, 350 |

| OCH-1 | Ochrobactrum anthropi | AJ401618 | Chr | Ochrobactrum anthropi | 390 | 351 |

| P99 (ACT-89) | Enterobacter hormaechei P99 | X07274 | Chr | Enterobacter hormaechei | 397 | 352 |

| PAO-1 (PDC-1) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Pseudomonas-derived cephalosporinase) | AY083595 | Chr | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 397 | 353, 354 |

| PAC-1 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa Class C | KY285014 | Tn | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 381 | 75 |

| SLC-1 | Serratia liquefaciens Class C | DQ022079 | – | uncultured bacteria (soil) | 379 | 76 |

| PSI-1 | Psychrobacter immobilis | X83586 | Chr | Psychrobacter immobilis | 401 | 355, 356 |

| RHO-1 | Rhodobacter sphaeroides | CP000144 | Chr | Rhodobacter sphaeroides | 380 | 357 |

| SR50 (SRT-1-like) | Serratia marcescens SR50, Serratia resistant | X52964 | Chr | Serratia marcescens | 376 | 358 |

| SST-1 | Susceptible strain | AB008455 | Chr | Serratia marcescens | 378 | 359 |

| TRU-1 | Formerly Aeromonas tructi | EU046614 | Chr | Aeromonas enteropelogenes | 382 | 360 |

| YEC-1 | Yersinia enterocolitica cephalosporinase | X63149 | Chr | Yersinia enterocolitica | 388 | 361 |

| YRC-1 | Yersinia ruckeri cephalosporinase | DQ185144 | Chr | Yersinia ruckeri | 383 | 362 |

Chr, chromosome; In, integron; P, plasmid; Tn, transposon; IS, insertion sequence; –, unknown.

Fusion between two β-lactamases (class C and class D).

The underlined letters form the name of the β-lactamase.

TABLE 3.

Conserved residues in class C β-lactamases

| Positiona | Residue (>90 % conserved) | Secondary structureb | % conservedb |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | P | H1 | 94 |

| 26 | P | S | 97 |

| 27 | G | E | 100 |

| 29 | A | E | 97 |

| 36 | G | T | 97 |

| 43 | F/Y/W | E | 100 |

| 44 | G | E | 100 |

| 54 | V | 91 | |

| 58 | T | 100 | |

| 60 | F | E | 100 |

| 61 | E | E | 100 |

| 63 | G | G | 100 |

| 64 | S | G | 100 |

| 66 | S | H2 | 100 |

| 67 | K | H2 | 100 |

| 71 | G/A | H2 | 100 |

| 73 | L | H2 | 94 |

| 77 | A | H2 | 91 |

| 94 | P | G | 94 |

| 96 | L | G | 100 |

| 109 | L | H3 | 97 |

| 110 | A/G | H3 | 100 |

| 111 | T | T | 100 |

| 113 | T/S | 100 | |

| 115 | G | S | 100 |

| 116 | G | 96 | |

| 118 | P | 94 | |

| 119 | L | S | 97 |

| 122 | P | 100 | |

| 123 | D/E | T | 100 |

| 134 | F/Y/W | H4 | 100 |

| 135 | Y/F | H4 | 97 |

| 138 | W | 97 | |

| 140 | P | 100 | |

| 145 | G | T | 97 |

| 148 | R | E | 100 |

| 150 | Y | 100 | |

| 152 | N | H5 | 100 |

| 155 | I | H5 | 91 |

| 156 | G | H5 | 97 |

| 159 | G | H5 | 100 |

| 170 | F/Y | H6 | 100 |

| 187 | T/S | Ω | 100 |

| 188 | Y/W/F | Ω | 100 |

| 191 | V | Ω | 97 |

| 192 | P | Ω | 97 |

| 199 | Y | Ω | 97 |

| 200 | A | Ω | 100 |

| 202 | G | Ω | 100 |

| 203 | Y | Ω | 100 |

| 210 | R/H | Ω | 100 |

| 211 | V | Ω | 91 |

| 213 | P | Ω | 94 |

| 214 | G | Ω | 94 |

| 221 | Y | Ω H7 | 100 |

| 222 | G | Ω | 100 |

| 224 | K | Ω | 94 |

| 229 | D | H8 | 100 |

| 260 | Y/W/F | E | 97 |

| 267 | Q | E | 100 |

| 269 | L | S | 97 |

| 271 | W | 100 | |

| 272 | E | E | 100 |

| 277 | P | S | 97 |

| 286 | G | H10 R2 | 97 |

| 315 | K | E | 100 |

| 316 | T | E | 100 |

| 317 | G | E | 100 |

| 319 | T | 97 | |

| 321 | G | S | 97 |

| 322 | F | 100 | |

| 325 | Y | E | 100 |

| 328 | F | E | 97 |

| 330 | P | E | 100 |

| 335 | G/A | E | 100 |

| 337 | V | E | 91 |

| 339 | L | E | 100 |

| 340 | A | E | 97 |

| 341 | N | S | 100 |

| 345 | P | 97 | |

| 349 | R | H11 | 100 |

| 353 | A | H11 | 100 |

According to the “SANC” class C β-lactamases numbering scheme described in reference 25. Residues in boldface type are involved in the catalytic mechanism and/or in substrate binding.

From the alignment of 32 representative class C β-lactamases examined in reference 25. H, α-Helix; S/T, bend or turn; E/B, β-strand or β-bridge; G, 310-Helix; Ω, Ω-loop; R2, R2-loop.

In a representative set of 50 typical AmpC (see Table 2), the total number of amino acids in these enzymes ranged from 358 (P. fluorescens TAE4) to 397 (PDC-1) with a mean value of 383 ± 5.2, and the mean of molecular mass was estimated at 41.64 ± 0.58 kDa. The number of amino acids may be much higher for enzymes with fused domains (29, 30). AmpC enzymes typically have alkaline isoelectric points (pI), with a mean pI of 8.48 ± 1.22 for this representative set. Nevertheless, low predicted pI values were obtained for some enzymes (4.37 for CHR-1, 5.27 for BlaE, 4.59 for RHO-1, and 5.59 for IDC-1) (4, 31).

Enterobacterales

The Enterobacterales (EB) are one of the major groups emerging from the phylogram in Fig. 1. This group was clearly separated into two major clusters based on the analysis of 413 protein sequences: EB1, including Buttiauxella, Cedecea, Citrobacter, Edwardsiella, Erwinia, Escherichia, Enterobacter, Klebsiella aerogenes, Lelliottia, Morganella, Pluralibacter, Serratia fonticola, Yersinia, and Xenorhabdus; and EB2, including Budvicia, Cronobacter, Erwinia, Hafnia, Pantoea, Photorhabdus, Pragia, Providencia, Regiella, Rouxiella, Serratia, and Siccibacter (32). Most species generally cluster together in the same genus or cluster, but, surprisingly, several species (e.g., Erwinia teleogrylli, S. fonticola and Y. ruckeri) were located at some distance from their main clusters. The following conserved residues distinguished between the EB1 and EB2 groups: D47K, V65L, G71A, V72T, G74A, W101F, Y112H, Q120F, S154G, F158L, W201Q, A255T, R258G, G270M, and H314N. A deletion in position 116 and an insertion in position 204a were also identified in EB2 (25, 33). These groups displayed a high degree of diversity (e.g., 55–100% sequence identity for the whole EB1 group). Consensus sequences (CS) were therefore determined for the main species.

For Escherichia species (E. coli/Shigella, E. albertii, and E. fergusonii), sequence identity ranged from 88% to 100% and 11 consensus sequences were obtained from 367 protein sequences. The E. coli sensu stricto population is now considered to have a strong phylogenetic structure, with the identification of at least 12 phylogroups (A, B1, B2, C, D, E, F, G, H, clade 1, clade III, and clade IV) (34).

Several conserved residues were found to be specific for phylogroups A, A1, and B1 (235R, 238M, 239N, 241R, 245N), whereas others were specific for phylogroups B2 and D (235Q, 238L, 239K, 241L, 245N/T) (16). All four clusters (A–D) carry RMNRE residues in the 235–245 region (33), and this key feature was observed in clinical isolates able to generate extended-spectrum AmpC β-lactamases (ESACs), as described above. The 287SGN triplet is present in the sequence of such enzymes (35). Phylogroup B2 contains the specific conserved residues 175K, 193S, 282I, 288D, 296R, and 300P, and is separated from phylogroup D by the residues 185T and 244T, in particular.

Finally, 78 protein sequences from uncultured bacteria obtained by metagenomic analyses on human fecal and environmental samples, originally found in the NCBI database as class C CMY-LAT-MOX-ACT-MIR-FOX β-lactamases, belong to this major cluster. They have been assigned to E. coli, Shigella, E. fergusonii, or E. albertii, and are characterized by a typical triplet (6HSE) (36–38).

One particular feature of interest is that all the protein sequences obtained from the genus Hafnia (H. alvei, H. paralvei) carry a two-residue deletion (residues 289–290) in H-10 and the R2-loop. The plasmid-encoded enzymes ACC-1 and ACC-4 are more than 99.4% identical to the AmpC of H. paralvei, a newly identified bacterial species (39, 40).

Aeromonas

The second major group identified included 318 protein sequences from Aeromonas, a genus for which many new species have been discovered over the last 2 decades. This is also the group in which the first inducible cephalosporinases (AsbA1, CAV-1, CepH, CepS) were detected, in A. hydophila (41), A. jandei (42), A. sobria (43), and A. caviae (44). The group is highly diverse, with a sequence identity ranging from 50% to 100%. Thirty-six species from this group have been identified, including about 20 species pathogenic to humans, such as A. caviae, A. dhakensis, A. veronii, and A. hydrophila (45). Phylogenetic analysis identified two CS for A. caviae, A. dhakensis, A. hydrophila, and A. salmonicida, with sequence identities of 80% to 100%, suggesting that new species may be discovered in the future (46, 47). Some of these species displayed a particular primary structure modification: the deletion of two or three residues (positions 301 to 303) in the R2-loop, as in A. caviae and in A. dhakensis (25).

Acinetobacter

Genus Acinetobacter has a long history of taxonomic changes, but is dominated by A. baumannii, the principal genomic species, which plays a major role in nosocomial infections, particularly in intensive care units (48, 49). This major group is heterogeneous, with 500 protein sequences and 26 species, and with sequence identities ranging from 42% to 100% (50). The denomination ADC for “Acinetobacter-derived cephalosporinase,” followed by a number to distinguish between individual enzymes, was proposed because of the large numbers of A. baumannii variants or members of the Abc complex (51) (http://bldb.eu/BLDB.php?prot=C#ADC). In a previous analysis of 103 genomes, the blaADC-like gene was found to be present in 13 validly named species, eight genomic species, and six taxa (52). Three major clusters were identified: one cluster including the A. baumannii–A. calcoaceticus or Abc complex and a number of other species: A. lactucae (formerly known as A. dijkshoorniae), A. nosocomialis, A. oleivorans, A. pittii, and A. seifertii; a second cluster containing nine species: A. apis, A. albensis, A. bereziniae, A. bohemicus, A. celticus, A. guillouiae, A. johnsonii, A. kyonggiensis, and A. rudis; and a third cluster including a number of other species: A. baylyi, A. beijerinckii, A. gyllenbergii, A. haemolyticus, A. junii, A. proteolyticus, A. parvus, A. soli, A. ursingii, A. tjernbergiae, and A. venetianus (50). A large number of protein sequences were initially misidentified, for two reasons. The first was the substantial taxonomic modifications that had taken place, and the second was the preferential use of standard biochemical methods and automated systems or devices widely used in clinical bacteriology laboratories, such as API 20NE, Vitek 2, Phoenix, Biolog, and MicroScan WalkAway, potentially leading to incorrect identification. MALDI-TOF can facilitate correct identification of the members of the Abc complex to species level, provided that an accurate database is used (15, 49). Accurate identification of the clinically important members of the Abc complex (A. baumannii, A. pittii, A. nosocomialis, A. seifertti and A. dijkshoorniae) and A. calcoaceticus, which is considered pathogenic, is possible only by molecular methods such as DNA-DNA hybridization (gold standard method) and DNA sequence-based analysis on various types of DNA sequences (16S rRNA, rpoB, 16S-23S intergenic spacer) (15). The 16S rRNA sequencing method is highly reliable at genus level, but discriminates poorly between species. By contrast, rpoB genes are highly variable and considered appropriate for Acinetobacter species identification. The multiplex PCR based on species-specific genes, such as gyrB, is simple, rapid (results obtained within 2 h), and reproducible, but limited to major species: A. baumannii, A. nosocomialis, A. pittii and A. calcoaceticus.

One structural feature distinguishing these clusters was a conserved deletion of three residues in the R2-loop (residues 304–306) for the first two clusters (53, 54). The third cluster, including A. baylyi producing ADC-8 with a low susceptibility pattern, particularly for cephalosporins, did not display this deletion (54, 55). ADC-1 and ADC-68, naturally produced by A. baumannii, carry this deletion of three residues in the R2-loop (residues 304–306) and were considered to be extended-spectrum AmpC (ESACs). Such enzymes typically hydrolyze penicillins and narrow- and expanded-spectrum cephalosporins and aztreonam, but not cefepime. Acquired resistance to cefepime or cefpirome has been reported to be associated with amino-acid substitutions—R148Q (close to YXN), V211A (within the Ω-loop), and N287S (in helix H-10)—also conferring higher levels of resistance (4 to 64 times higher) to ceftazidime and cefotaxime (56, 57). Ceftazidime resistance resulted from overproduction of the ADC β-lactamase and the provision of strong promoter sequences by the insertion sequence ISAba1 (56, 58).

In conclusion, the complexity of this bacterial group suggests that other species are likely to be identified, particularly given the very small size of some of the clusters identified.

Pseudomonas

A phylogenetic analysis of 582 class C protein sequences from Pseudomonas yielded a broad distribution, with at least 36 clusters. Sequence identity varied considerably, from 42% to 100%, between the 33 species producing class C β-lactamases from this group. Heterogeneity levels were particularly high for some species, such as P. putida, for which at least 11 clusters were observed, and for P. fluorescens, suggesting misidentification, as reported by subsequent comparative studies of genomes (59–64). Indeed, the Pseudomonas group is among the most diverse in terms of the species it contains, but, with the exception of P. aeruginosa, for which 430 sequences have been analyzed, its taxonomy is still under revision.

P. aeruginosa is one of the principal pathogens isolated from immunosuppressed patients and cases of hospital-acquired infections associated with multiresistance (65). It also causes chronic lung infections in patients with cystic fibrosis (66). The effective treatment of P. aeruginosa infections is challenging, because several mechanisms of resistance to antibiotics, including β-lactamases and efflux pump overexpression, have evolved in this species (67). An inducible chromosomal AmpC-type enzyme was identified, with a wild-type inactivation spectrum including various β-lactams, such as aminopenicillins, the oldest cephalosporins, and cephamycins. Following its overproduction due to mutations altering the peptidoglycan recycling process, this cephalosporinase is a major source of resistance to ticarcillin, piperacillin, ceftazidime, and aztreonam (68, 69). However, additional missense mutations have extended its inactivation spectrum to cefepime and cefpirome. Many variants, also observed as natural polymorphisms, have been named according to a nomenclature specifically developed for P. aeruginosa, as PDCs (Pseudomonas-derived cephalosporinases) (68, 69). A phylogenetic analysis of 430 sequences displaying 87% to 100% identity yielded two clusters (C1, C2). The main cluster (C1), containing 416 protein sequences, had a consensus sequence with several variants (70). The second cluster (C2) was very small, comprising only 14 sequences. The polymorphism observed in cluster C1 had already been described in 44 antibiotic-susceptible strains with amino-acid substitutions at positions 53, 71, 79, 149, 178, and 365 (69). However, other variants were observed, in particular in positions 121, 153, 174, 178, 213, 216, 219, and 293, which served as mutation hot spots, thus extending the substrate specificity of PDC β-lactamases (see the section on ESACs).

Plasmid-encoded Enzymes

Chromosomal class C β-lactamases predominate, but plasmid-mediated enzymes are nevertheless important, and the protein sequences of 256 such enzymes were examined. Since their emergence in 1989, several types of plasmid-encoded AmpCs and their variants have been identified: ACC, ACT, CFE, CMY-2/BIL/LAT, DHA, FOX, MIR, and MOX/CMY-1 (4, 8, 22). CMY-2 is the most common plasmid-encoded enzyme family, detected worldwide in isolates that do not naturally produce a cephalosporinase (P. mirabilis, K. pneumoniae, and S. enterica, in particular), and also in E. coli, which has a weak expression of the natural cephalosporinase. This family displays little variability, with only about 8% of amino acids varying in a comparison of 92 sequences, including BIL-1 and LAT-1. Other families varied in terms of the number of protein sequences and percent identity: ACC (2 and 99%), ACT (10 and 86%), CFE (2 and 92%), DHA (15 and 97%), FOX (13 and 94%), MIR (5 and 99%), and MOX/CMY-1 (10 and 75%). Since the 1990s, many modifications have been made to bacterial taxonomy, with the definition of new bacterial species, particularly in the genera Citrobacter, Enterobacter, and Aeromonas. Finally, phylogenetic analysis confirmed several changes in the identification of the progenitors for chromosomal and plasmid-encoded cephalosporinases (25, 71–74) (Table 4). The rare class C β-lactamases SLC-1 and PAC-1, encoded by a gene in a chromosome-inserted Tn1721-like transposon, probably originate from an enterobacterium, but the origins of other enzymes (integron-encoded IDC-types, Alaska soil metagenomes LRA10-1, LRA13-1, LRA18-1) remain unknown (30, 31, 75, 76).

TABLE 4.

Class C β-lactamases and species-specific progenitors

| Enzyme/straina | First identification | Updated identification | %b | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACC-1*c | Hafnia alvei | Hafnia paralvei | 99.7 | 321, this review |

| ACT-1*c | Enterobacter cloacae | Enterobacter asburiae | 98.4 | 322, this review |

| Aer-1 | Enterobacter aerogenes | Klebsiella aerogenes | 98.9 | 338, 363 |

| AQU-1 | Aeromonas aquariorum | Aeromonas dhakensis | 99.2 | 249, 364 |

| AsbA1 | Aeromonas sobria | Aeromonas jandaei | 94.5 | 324, this review |

| BIL-1* | Citrobacter freundii | Citrobacter portucalensis | 96.8 | 326, this review |

| BUT-1 | Buttiauxella sp. | Scandinavium goeteborgense | 99.0 | 329, 365 |

| BUT-2 | Buttiauxella agrestis | Scandinavium goeteborgense | 99.5 | 339, 365 |

| CAV-1 | Aeromonas caviae | Aeromonas allosaccharophila | 97.1 | 44, 71 |

| CFE-1* | Citrobacter freundii | Citrobacter europaeus | 99.2 | 208, this review |

| CFE-2* | Citrobacter freundii | Citrobacter werkmanii | 95.0 | 366, this review |

| CMY-1*c | Aeromonas hydrophila | Aeromonas sanarellii | 95.3 | 233, this review |

| CMY-2* | Citrobacter freundii | Citrobacter portucalensis | 98.4 | 335, this review |

| EDC-1 | Edwardsiella tarda | Edwardsiella piscicida | 99.1 | This review |

| FOX-1* | Aeromonas caviae | Aeromonas allosaccharophila | 94-98 | 71, 341 |

| LAT-1* | Citrobacter freundii | Citrobacter portucalensis | 97.4 | 345, this review |

| MIR-1*c | Enterobacter cloacae | Enterobacter roggenkampii | 99.7 | 25, 352 |

| MOX-1* | Aeromonas hydrophila | Aeromonas sanarellii | 94.5 | 72, 232 |

| MOX-2* | Aeromonas sp. | Aeromonas caviae | 98.9 | 72, 234 |

| MOX-9* | Aeromonas caviae | Aeromonas media | 98.0 | 72, 367 |

| P99 (ACT-89) | Enterobacter cloacae | Enterobacter hormaechei | 97.9 | 25, 352, this review |

| TRU-1 | Aeromonas tructi | Aeromonas enteropelogenes | 97.1 | 360, this review |

Plasmid-encoded enzymes are labeled by an asterisk.

Percentage of identity with consensus sequence.

Other plasmid-encoded types: ACC-4 (99.5% for H. paralvei); ACT-3, ACT-6, ACT-8, and ACT-10 (≥97.6% for E. asburiae); CMY-17, CMY-55, CMY-132, and CMY-161 (≥ 98.1% for A. sanarellii); MIR-4 (99.4% for E. roggenkampii). Their respective phylogenies can be found in references 32, 46, 50, and 63; and 73 and 74.

Serine Hydrolase, a Class C β-lactamase or a Carboxylesterase VIII?

BLCs are usually genus-specific and chromosomally encoded, found mostly in Gram-negative bacteria, and more specifically in Alpha-, Beta- and Gammaproteobacteria. However, several clusters (e.g., Legionella, Bradyrhizobium, Parachlamydia) are clearly divergent, with low levels of sequence identity (between 10 and 20%) (28) (Fig. 1). This early divergence is related to a limited number of highly conserved motifs or residues, most reported in Table 3: 43Y/G, 54V/T, 58T, 60F/E, 63A/G, 64SXXK, 94P, 96L, 109L, 111T, 138W, 140P, 145G, 148R/Y, 150YXN/H, 187T, 202G/Y, 229D, 271W, 315KXG, 330P, 335G, 337V, 339L, 341N, 357L, and 360L. Several bacteria from Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes (e.g., Pelosinus fermentans, Sediminibacterium salmoneum) also carry enzymes with some of these highly conserved residues and motifs: 27G, 44G, 58T, 60F, 61E/F, 63G, 64SXXK, 67K, 94P, 115G, 144G, 150YXN, 200A, 202G, 220A/S, 222G/S, 229D, 315K/HT/SG, 319T, 321GF, 337V, and 341N. These enzymes are generally identified as serine hydrolases in databases, but with no additional bacteriological and enzymatic details that could be used to determine whether or not they should be considered as class C β-lactamases.

One family of enzymes (microbial carboxylesterases VIII, EC 3.1.1.1) mostly identified in metagenomic libraries from various environmental samples, including EstC, EstM-N1/N2, Est22, EstU1, and EstSRT1, appears to be phylogenetically and structurally related to BLCs (Fig. 1). These enzymes generally hydrolyze nitrocefin (EstC), cephalothin (Est22), cephaloridine, cefazolin (EstU1), and oxyiminocephalosporins (EstSRT1) (77–83). The EstB and Est22 enzymes selectively deacetylate cephalosporin-based substrates leaving the amide bond of the β-lactam ring intact (82, 83), while for EstU1 it was not clear from the HPLC data if the observed pattern against cephalosporin substrates was due to deacetylation or amide bond hydrolysis of the β-lactam ring (77). The catalytic efficiencies of EstSRT1 for cephalothin, cefotaxime, and cefepime are similar to that of EstU1 for cefazolin (77). These enzymes bear the active site residues 100S, 103K, and 218Y (64S, 67K, and 150Y according to SANC numbering), as well as other residues highly conserved in BLCs (Table 3). They have an overall structure consisting of a mixed α/β domain and a small helical domain, similar to that of class C β-lactamases (80, 84–86).

The classification of these carboxylesterases as BLCs does not appear to be appropriate, given the total absence of β-lactamase activity for some of these enzymes, their low levels of in vitro antibacterial activity against β-lactams, including cephalosporins, their primary structure, and their low levels of sequence identity to genuine BLCs. Nevertheless, these findings suggest that the promiscuous β-lactamase activity of some of these family VIII esterases may have evolved from BLCs or vice versa, and that some may have closer evolutionary relationships to BLCs (79).

SECONDARY AND TERTIARY STRUCTURES

The first crystallographic structure of an AmpC was reported in 1994, for the covalent complex between a phosphonate transition-state analog and the E. hormaechei P99 (formerly known as E. cloacae P99) cephalosporinase, which belongs to the ACT family (87). Many structures from different families of class C β-lactamases have since been published, including ACC (88, 89), ACT (87, 90–102), ADC (53, 103–108), CMH (109), CMY (100, 110–114), EC (111, 115–152), FOX (153–155), MOX (156, 157), PDC (158–167) and TRU (168) enzymes, together with the halophilic β-lactamase (HaBLA) from Chromohalobacter sp. 560 (169) and the class C β-lactamase from a psychrophilic organism, Pseudomonas fluorescens (170). More than 200 structures of class C β-lactamases have been described, and an updated list of these structures can be found in the Beta-Lactamase DataBase (BLDB; http://bldb.eu/S-BLDB.php) (22).

The typical three-dimensional structure of class C β-lactamase contains two mixed α/β domains: one composed of nine antiparallel β-sheets and three α-helices (H1, H10 and H11) on one side, and the other, composed of three small antiparallel β-sheets and eight α-helices (H2 to H9) on the other side (Fig. 2). Two additional structural elements important for the interaction with substrates, Ω-loop and R2-loop, are located between H6 and H8 (residues 189–225), and close to H10 (residues 288–309), respectively (see reference 25 for a detailed analysis of residues involved in these regions). Structurally, class C β-lactamases belong to the Beta-lactamase PFAM family (PF00144) and share the same overall fold with class A and class D β-lactamases, penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), and family VIII carboxylesterases.

FIG 2.

Representative three-dimensional structure for class C β-lactamases. The structure of E. hormaechei P99 (formerly known as E. cloacae P99; PDB code 1BLS) (87) is colored in orange (α-helixes) and purple (β-strands). The Ω- and R2-loops are colored in green and blue, respectively. The most conserved residues (see Table 3) are represented as sticks and colored in cyan. The numbering of residues follows the SANC nomenclature (25).

REGULATION AND EXPRESSION OF CLASS C β-LACTAMASES

In some Enterobacterales (other than E. coli) and P. aeruginosa, ampC gene expression is weak and inducible. This induction involves several proteins (AmpR, AmpD, and AmpG) and two muropeptides (4, 171–174). Nevertheless, the molecular mechanisms mediating AmpC overproduction in P. aeruginosa appear to be more complex than initially thought, as other proteins, such as AmpDh2, AmpDh3, and DacB (PBP4), have since been identified as involved in these mechanisms (175–177).

Genetic Context and Regulation

The ampR and ampC genes are linked. AmpR is encoded by a gene located immediately upstream from ampC and acts as a transcriptional activator, binding to the intercistronic region upstream from the ampC gene promoter. The ampD gene encodes an N-acetyl-anhydromuramyl-L-alanine amidase involved in recycling the products of peptidoglycan catabolism, including, in particular, the 1,6-anhydro-N-acetylmuramyl-tripeptide (anhNAM-tripeptide). AmpD releases the tripeptide, which is then recycled for synthesis of the UDP-NAM pentapeptide (uridine 5′-pyrophosphoryl-N-acetylmuramic acid-pentapeptide), for integration into the neo-peptidoglycan. There is therefore a permanent balance between these two components in the cytoplasm.

Under normal conditions, AmpR associates with the UDM-NAM pentapeptide, and the resulting complex binds to the intercistronic region, thereby preventing transcription from both the ampR and ampC promoters. However, the presence of excess anhNAM-tripeptide alters this binding and promotes an increase in ampC transcription. Two clinical situations can result in an excessive increase in anhNAM-tripeptide levels: substantial degradation of the peptidoglycan due to the presence of β-lactams in the periplasmic space, and changes in the AmpD amidase preventing the recycling of this component.

In E. cloacae complex and C. freundii, the main cause of ampC overexpression is represented by amino-acid substitutions in AmpD, resulting in the constitutive production of large amounts of AmpC and increasing resistance to cefotaxime and ceftazidime. Several resistant clinical isolates or in vitro mutants displaying AmpC overproduction have been identified in the Enterobacterales, including C. freundii and E. cloacae with various amino-acid substitutions (e.g., W7G, H34A, S37R, Y63F, R80H, G82C, A94P/V, Y102, E116A, L117R, R108 D121G, D127G, N150I, H154N, A158D, K162H/Q, D164E/A, W171, A172L) capable of triggering constitutive β-lactamase production (178–182). In some cases, the ampD gene is truncated by a premature stop codon or an IS1 insertion, or an IS4321 element may be inserted into the promoter (178, 183, 184).

In P. aeruginosa, acquired resistance to amino- and ureido-penicillins, cephamycins, and, to a lesser extent, to oxyiminocephalosporins (ceftazidime, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone) and aztreonam, is very often related to overproduction of the PDC β-lactamase, which is also linked to virulence (185). Several variants with ampD mutations displaying resistance in vivo and in vitro have been reported (186–189). As in the Enterobacterales, the principal genetic mechanisms involved missense mutations creating amino-acid substitutions (A84G, D61Y, G148A, A136V, G148A, S175L) or insertion sequences (IS1669).

The LysR-type transcriptional regulator AmpR was initially identified as involved in regulating the inducible class C β-lactamases produced by various Gram-negative rods, such as C. freundii, E. cloacae, S. marcescens, and P. aeruginosa. However, recent results indicate that in P. aeruginosa AmpR regulates the expression of many genes involved in other pathways, such as quinolone resistance, quorum sensing, and associated virulence phenotypes (190). Phylogenetic analyses revealed the presence of AmpR homologs in many Alpha-, Beta-, and Gammaproteobacteria, and several highly conserved residues were found in C. freundii, E. cloacae, and P. aeruginosa (190, 191). AmpR loss leads to susceptibility to β-lactams, whereas constitutively high levels of ampC expression were reported for clinical isolates and in vitro strains with mutations resulting in AmpR amino-acid substitutions: C. freundii (S35F, G102D/E, D135A, Y264N) (4, 192, 193), E. cloacae (T84I, R86C, D135N/V, E274K) (178, 194), and P. aeruginosa (A12R, D135N, G154R, G237A) (186, 195–197). Transposon mutagenesis of P. aeruginosa strain PAO-1 and complementation experiments have generated two mutants with stronger β-lactam resistance due to transposition into two new genes (mpl, nuoN) (198).

AmpG, an intrinsic membrane protein, displays permease activity mediating the transport of muropeptides from the periplasm to the cytoplasm, such transport being essential for the induction of class C β-lactamases (199–201). Deletion of the gene encoding this protein in P. aeruginosa results in a lower level of bacterial resistance to ampicillin. AmpG proteins are widespread and highly variable in Gram-negative bacteria (e.g., Enterobacterales, A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa). Genetic experiments showed that ampG genes from E. coli and A. baumannii can complement AmpG function in P. aeruginosa (200). In this species, the site-directed mutagenesis of some highly conserved AmpG residues (G29A, G29V, A129V, A197S, and A197D mutants) results in a loss of resistance to ampicillin; ampG mRNA levels were found to be normal for two other mutants (A129T and A129D), but the proteins encoded had much lower levels of activity (200).

AmpC Overproduction in E. coli

In E. coli, in the absence of the ampR gene, the expression of ampC is usually weak, under the control of a naturally nonefficient promoter (4). In this species, acquired resistance to old or narrow-spectrum cephalosporins, cephamycins (e.g., cefoxitin), or even oxyiminocephalosporins, is related to ampC overexpression due to the selection of a stronger promoter by mutation, or, less often, by insertion (202, 203). The most important factors responsible for strengthening the ampC promoter are mutations creating a consensus -35 box (TTGACA) by T/A transversion at position -32 or C/T transition at position -42, and base-pair insertions increasing the distance between the -35 and -10 boxes to 17 or 18 bp (4, 203, 204). Mutations have also been identified within the attenuator region and the -10 box, but such mutations have little effect on ampC expression. Similar promoter mutations have been reported in strains from livestock, such as pigs or calves (205, 206).

AmpC Overproduction in A. baumannii

Overexpression of the chromosomal ampC gene in A. baumannii was observed following the acquisition of an IS element, mostly ISAba1, resulting in a strong promoter and resistance to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins (cefotaxime, ceftazidime) and aztreonam (207).

Transferable β-lactamases

Most plasmid-encoded class C β-lactamases mobilized by transposons and insertion sequence elements, with the exception of the ACT-1, CFE-1, and DHA-types, are in a “derepressed” state (31, 208–210). The genes encoding the ACC-1 and CMY-2 types are transcribed under the control of a strong promoter in the mobile element (ISEcp1 or IS26) (211, 212). The high level of blaMIR-1 gene expression is due to the presence of a more efficient hybrid promoter upstream from the natural promoter (213). All these genes are often associated with integrons inserted in close proximity and forming composite structures with other transposable elements, including a gene cassette in a class 1 integron characterized by rapid spread (31). Gene cassettes are under the control of a constitutive promoter specific for the gene cassette array. Their expression level is determined not only by promoter strength, but also by distance from the promoter (214). The removal of ampC gene cassettes from the integron may constitute a less costly control mechanism than the continuous overproduction of many plasmid-borne class C enzymes (215). However, three plasmid-encoded enzyme types with an ampR gene (ACT-1, CFE-1, DHA-1) and a genetic organization identical to those of chromosomal enzymes rarely cause resistance to oxyiminocephalosporins despite constitutively high levels of AmpC activity due to an amino-acid substitution (D135A) (190, 193).

In conclusion, given the complexity of the regulation of ampC expression, the variability of these genes in databases and the small number of clinical examples of acquired resistance with the identification of hot spots for at least ampR, ampD, and ampG, it is not currently appropriate to analyze such mutants by genomic procedures, particularly in the absence of the initial susceptible clinical isolate. Classical methodologies are preferable for the detection of AmpC β-lactamase overproduction. These methods include phenotypic approaches assessing synergy between a cephamycin or an oxyiminocephalosporin and an inhibitor, such as cloxacillin or boronic acid (4). Nevertheless, the determination of β-lactamase activity with or without imipenem or cefoxitin induction, together with determinations of the mRNA levels for these genes by real-time RT-PCR, is probably much more accurate (69, 200, 216–218).

ACQUIRED EXTENDED-SPECTRUM CEPHALOSPORINASES (ESACs)

In Gram-negative bacteria, such as the Enterobacterales, various genetic events may increase the level of resistance, particularly to oxyiminocephalosporins, such as ceftazidime, cefotaxime, and, to a lesser extent, cefepime and cefpirome. The evolution of such resistance led to a new denomination: ESAC, for extended spectrum AmpC β-lactamases (219). The first ESAC was identified in an E. cloacae isolate (GC1) in Japan in 1992, based on the duplication of three amino acids at positions 208–210 (Ω-loop) and constitutive production (10).

In E. coli, AmpC is constitutively produced in small amounts in the absence of the ampR gene, under the control of a weak promoter (4). Within this species, acquired resistance to old or narrow-spectrum cephalosporins (e.g., cefoxitin) is related to the overproduction of AmpC due to the selection of a strong promoter generated by mutation, or, less often, by insertion (202, 203). A second step in the development of resistance involved the acquisition of plasmid-encoded AmpCs with a higher level of resistance to ceftazidime and aztreonam, for example (8). Finally, an even higher level of resistance (e.g., to cefepime or cefpirome) was developed following the emergence of an ESAC at low prevalence (≤1%) in human clinical isolates and even isolates from cattle (16, 220–222).

The genetic determinism of ESACs, leading to an increase in the catalytic efficiency of these enzymes against extended-spectrum cephalosporins, is based principally on missense mutations resulting in amino-acid substitutions, with structural modifications to the R1 (Ω-loop between residues 189 and 225) or R2 (H10 helix between residues 280 and 292 and/or R2-loop between residues 286 and 310) binding sites. Insertions or duplications in H10 or the R2 loop were also observed (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Localization of ESAC-associated mutations in chromosomal or plasmid-encoded class C β-lactamases, the exact position of each mutation and the specific regions associated with each cluster

| Bla or straina | Location | First numbering | Updated numberingb | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||||

| MEV | H10-helix | S282 duplication | idem | 368 |

| ECB33 | H10-helix | I283 duplication | I284 | 223 |

| HKY28 | H10-helix | 286GSD deletion | idem | 225 |

| EC16 | H10-helix | S287C | idem | 16 |

| EC13 | H10-helix | S287N | idem | 16, 35 |

| 8009162 | H10-helix, R2-loop | A292V | idem | 221 |

| EC80 | H10-helix, R2-loop | L293P | idem | 369 |

| BER | R2-loop | 293AA insertion | idem | 370 |

| 7014517 | R2-loop | 295ALA insertion | idem | 221 |

| EC15 | R2-loop | H296P | idem | 16, 240 |

| EC14 | R2-loop | V298L | idem | 16, 240 |

| KL | H11-helix | V350F | idem | 224 |

| Citrobacter | ||||

| CHA | close to YSN | R148H | idem + Q196H | 35, 371 |

| CMY-107 | Ω-loop | Y199C | idem | 372 |

| CMY-27 | Ω-loop | W221C | W201C | 373 |

| CMY-30 | Ω-loop | V231G | V211G | 374 |

| CMY-42 | Ω-loop | V231S | V211S | 260, 375 |

| CMY-95 | Ω-loop | V211A | idem | 369 |

| CMY-32 | Ω-loop | G214E | idem | 376 |

| CMY-54 | Ω-loop | 217EL insertion | 216aEL insertion | 377 |

| GN346 | Ω-loop | E219K | idem | 378 |

| CMY-136 | Ω-loop | Y221H | idem | 113 |

| CMY-172 | R2-loop | 290KVA deletion+ N346I | idem | 295 |

| CMY-2 | R2-loop | A292P or L293P | idem | 379 |

| CMY-33 | R2-loop | 293LA deletion | idem | 235, 380 |

| CMY-44 | R2-loop | 293LAAL deletion | idem | 235 |

| CMY-69 | R2-loop | A295P | A294P | 381 |

| CMY-99 | R2-loop | P306T | idem | 382 |

| CMY-37 | R2-loop | L316I | L296I | 383 |

| Enterobacter | ||||

| LN04004SS1 | Ω-loop | 213K-226G deletion | idem | 384 |

| GC1 | Ω-loop | 208AVR duplication | idem | 10, 97 |

| CHE | R2-loop | 289SKVALA294 deletion | idem | 9 |

| Ent630 | R2-loop | 292-293 AL deletion | idem | 294 |

| P99 (ACT-89) | R2-loop | L293P | idem | 385 |

| MHN | R2-loop | V298E | idem | 386 |

| LN04004SS1 | H11-helix | N366H | N346H | 384 |

| K. aerogenes | ||||

| EA6/13/17/20 | H3-helix | Q90H, W101C, L107Y | idem | 387 |

| Ea595 | H10-helix, R2-loop | V291G | idem | 388 |

| Ear2 | R2-loop | L293P | idem | 338 |

| S. marcescens | ||||

| 520R | H2-helix | T64I | T70I | 389 |

| SRT-1 | Ω-loop | E213K | E219K | 359 |

| ES46, ES71 | Ω-loop | E235K | E219K | 390 |

| SMSA | Ω-loop | S220Y | idem | 391 |

| HD | R2-loop | 287MNGT deletion | 293MNGT deletion | 392 |

| Hafnia | ||||

| ACC-4g | Ω-loop | V211G + 289-290 deletion | idem | 393, this review |

| ACC-1g | R2-loop | 289-290 deletion | idem | 25, 250, this review |

| ACC-2 | R2-loop | 289-290 deletionc | idem | 250, this review |

| Aeromonas | ||||

| CMY-9 | R2-loop | E85D + 299-301 deletion | E61D + 301-303 deletion | 394 – 396 |

| CMY-19 | R2-loop | I292S + 299-301 deletion | I292S + 301-303 deletion | 236, 395, 396 |

| CMY-1 | R2-loop | 299-301 deletion | 301-303 deletiond | 110, 236, 397 |

| MOX-1 | R2-loop | 303-305 deletion | 301-303 deletiond | 156 |

| MOX-2 | R2-loop | 303-305 deletion | 301-303 deletione | 234, this review |

| MOX-13 | R2-loop | 303-305 deletion + N346I | 301-303 deletione | 398, this review |

| CMY-10 | R2-loop, H11-helix | E85D + 299-301 deletion | E61D + 301-303 deletion | 110, 237, 395, 397 |

| A. baumannii | ||||

| ADC-56 | H5-helix | R148Q | idem | 57 |

| ADC-53 | Ω-loop | V208A | V211A | 56 |

| ADC-33 | Ω-loop | P210R + 215A duplication | P213R + 218aA duplication | 248 |

| ADC-51 | R2-loop | N283S | N287S | 56 |

| ADC-1 | R2-loop | 304-306 deletion | idem deletionf | 53 |

| ADC-68 | Ω-loop | G220D + R320G | G217D + R321G | 108 |

| P. aeruginosa | ||||

| PDC-222 | H2-helix | T96I | T70I | 230 |

| PDC-78 | H2-H3-loop, Ω-loop | R100H + G216R | R100H + R215G | 69 |

| PDC-82 | H3-H4-loop | F121L + M175L | F121L + M174L | 69, 229 |

| PDC-73 | H5-helix | P154L | P153L | 69 |

| PDC-82 | H6-helix | M175L | M174L | 69 |

| PDC-50 | Ω-loop | V213A | V211A | 69 |

| PDC-74 | Ω-loop | G216R | G215R | 69 |

| PDC-86 | Ω-loop, H7-helix | E221K | E219K | 69 |

| PDC-80 | Ω-loop, H7-helix | E221G | E219G | 69 |

| PDC-85 | Ω-loop, H7-helix | Y223H | Y221H | 69 |

| PDC-223 | Ω-loop | 229G-247E deletion | 202G-219E deletion | 230 |

| PDC-221 | Ω-loop | E247K | E219K | 69 |

| PDC-88 | H10-helix, R2-loop | 290TP deletion | 289TP deletion | 69 |

| PDC-89 | H10-helix, R2-loop | 290TPM deletion | 289TPM deletion | 69 |

| PDC-91 | H10-helix, R2-loop | 290TPMA deletion | 289TPMA deletion | 69 |

| PDC-44 | R2-loop | L294P | L293P | 69 |

| PDC-92 | R2-loop | 294LQ deletion | 293LQ deletion | 69 |

| PDC-76 | H11-helix | N347I | N346I | 69 |

Strain names are underlined.

According to the Standard Numbering Scheme (25).

All AmpC sequences of H. paralvei and H. alvei examined have this deletion.

This cluster includes CMY-1, MOX-1, CMY-8, CMY-10, CMY-11, CMY-19, and MOX-14.

These enzymes were located in different clusters (72).

This deletion was observed for all A. baumannii sequences, and particularly for ADC-7 (51).

Plasmid-encoded.

Most ESACs belong to phylogenetic group A, but others belong to phylogenetic group B1 and are characterized by the presence of the following conserved residues: 235R, 238M, 239N, 241R, 245D, 281S, 288G, and 296H (16, 35, 221, 223). Nevertheless, two isolates with different residues in these positions have been reported (224). A single E. coli strain (HKY28) isolated from urine in Japan was found to produce an ESAC with a tripeptide deletion (286GS289D) altering binding to extended-spectrum cephalosporins, but also to sulbactam and tazobactam (225) (Table 5). Reversion of the deletion through a nine-base insertion restored the typical inhibitor-resistant phenotype of class C enzymes and decreased the level of resistance to cefepime and cefpirome. Finally, other positions affecting the ESAC phenotype were identified by the selection of mutants in vitro or by site-directed mutagenesis, resulting in a greater structural flexibility or affinity for extended-spectrum cephalosporins (141, 226).

Many BLCs (e.g., those of Pseudomonas, Citrobacter, Enterobacter, Morganella, and Serratia) are inducible, opening up possibilities for higher levels of production, resulting in stronger resistance to aminopenicillins, old cephalosporins, and ceftazidime or cefotaxime, and even to cefepime if the mutated enzyme is overproduced (227). Additionally, a significant proportion of strains has constitutive overproduction of class C enzymes, often after selection with β-lactam antibiotics. However, the risk of transitions between susceptibility and intermediate resistance (S/I) and between susceptibility and resistance (S/R) to cefepime is species-dependent. It is particularly high for the E. cloacae complex (66.3%), non-negligible for H. alvei (36.4%), moderate for Citrobacter and Proteus (18.1–21.9%) and S. marcescens (12.3%), low for K. aerogenes (1.1%), and inexistent for M. morganii (0%) (228). As summarized in Table 5, expansion of the inactivation spectrum results from missense mutations at several mutation hot spots (around triplet 150YAN, Ω-loop, H10-helix, and R2-loop), from duplications or deletions of 2–4 amino acids in the H10 helix (position 293), or insertions of amino acids into the Ω-loop. In some cases, two such events may be combined (Table 5). Various examples of increased catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) of these enzymes, particularly against extended-spectrum cephalosporins (ceftazidime, cefotaxime, cefepime), are illustrated in Table 6.

TABLE 6.

ESAC and effects on kinetic constants for groups of enzymes with different phenotypesa

| Bla or strainb | Mutation | Ceftazidime (CAZ) |

Cefotaxime (CTX) |

Cefepime (FEP) |

References | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) | kcat/Km (μM · s−1) | kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) | kcat/Km (μM · s−1) | kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) | kcat/Km (μM · s−1) | |||

| CMY-2-like | |||||||||||

| CMY-2 | 0.004 | 0.5 | 0.008c | 0.007 | 0.001 | 7 | 371 | ||||

| CMY-2 | R148H | 0.67 | 0.6 | 1.12c | NM | 0.003 | NM | 371 | |||

| CMY-2 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.5 | <0.01 | 0.005 | <2 | 372, 399 | ||||

| CMY-107 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.075 | 10.7 | 372 | ||||

| CMY-30 | 0.4 | 0.14 | 2.9 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 5.7 | 399 | ||||

| CMY-42 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 0.08 | 2.5c | 375 | ||||

| CMY-2 | 0.005 | 0.15 | 0.033 | 0.007 | 0.001 | 7 | 0.37 | 412 | 9 · 10−4 | 113, 296, 371 | |

| CMY-136 | 6.26 | 2360 | 0.003 | 4.71 | 20 | 0.24 | 1.79 | 3588 | 5 · 10−4 | 113 | |

| CMY-2 | NM | 1.8 | NM | NM | 108.1 | NM | 376 | ||||

| CMY-32 | 0.9 | 4.05 | 0.22 | NM | 988.9 | NM | 376 | ||||

| ACC | |||||||||||

| ACC-2 | 0.03 | 5.2 | 0.006c | 0.02 | 19 | 0.001 | 3.6 | 147 | 0.024 | 250 | |

| ACC-4 | 1.5 | 15 | 0.1 | 2.7 | 9.4 | 0.29 | 0.14 | 73 | 0.002 | 393 | |

| SRT | |||||||||||

| SerS | <0.5 | 50d | <0.01 | 2 | 4 | 0.5 | <0.5 | 100d | <0.005c | 391 | |

| SerR | S220Y | 520 | 570 | 0.9 | 800 | 980 | 0.8 | 330 | 1000 | 0.33 | 391 |

| FOX | |||||||||||

| FOX-3 | 0.273 | 1.18 | 0.231 | 0.081 | 0.076 | 1.06 | ND | ND | 3.32 · 10−3 | 241 | |

| FOX-8 | 2.6 · 10−3 | 0.382 | 6.8 · 10−3 | 18.2 · 10−3 | 10.95 · 10−3 | 1.66c | ND | ND | 1.36 · 10−3 | 241 | |

| FOX-4 | 1.33 | 13 | 10 | 1.33 | 0.23 | 5.69 | 11.01 | 1071 | 0.01 | 245 | |

| FOX-4 | 306GNSΔ | 0.84 | 6.44 | 0.13 | 0.24 | 0.087 | 2.75 | 2.5 | 103 | 0.02 | 245 |

| MOX-1/CMY-1-like | |||||||||||

| CMY-9 | 1.8 | 560 | 3.2 · 10−3 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.96 | NM | 950 | ND | 236 | |

| CMY-19 | 0.085 | 3.7 | 0.023 | 0.33 | 31 | 0.011 | 1.8 | 630 | 2.9 · 10−3 | 236 | |

| CMY-8 | 0.091 | 48 | 1.9 · 10−3 | 0.36 | 2.3 | 0.16 | 394 | ||||

| CMY-9 | 0.53 | 120 | 4.4 · 10−3 | 0.48 | 3.4 | 0.14 | 394 | ||||

| MOX-1 | ND | 311 | ND | ND | 211 | ND | 232 | ||||

| CMY-1 | 0.01 | 0.015 | 0.67 | 400 | |||||||

| CMY-10 | 5 | 33.9 | 0.15 | 110 | |||||||

| ACT | |||||||||||

| ACT-89 (P99) | 6.1 · 10−3 | 18.4 | 3.2 · 10−4 | 110 | |||||||

| ACT-89 (P99) | <1 | 20d | ND | 0.5 | 0.5d | 1 | 1 | 15d | 0.067 | 9 | |

| CHE | 289-294Δ | <1 | 1d | ND | 0.5 | 0.05d | 10 | 2 | 3d | 0.67 | 9 |

| ACT-89 (P99) | 0.065 | 28 | 2.3 · 10−3 | 401 | |||||||

| ACT-89 (P99) | L293C | 0.041 | 7 | 5.9 · 10−3 | 401 | ||||||

| ACT-89 (P99) | 0.013 | 15 | 8.7 · 10−4 | 0.5 | 100 | 4.7 · 10−3 | 385 | ||||

| ACT-89 (P99) | L293P | 0.10 | 10 | 0.01 | 3.1 | 24 | 0.13 | 385 | |||

| Ear | |||||||||||

| Ear | ND | 16d | ND | 0.15 | >500 | ND | 0.4 | 126 | 0.003 | 338 | |

| Ear2 | ND | 9.8d | ND | 0.15 | 10d | 0.015 | 0.4 | 9.1 | 0.044 | 338 | |

| ADC | |||||||||||

| ADC-1 | 0.7 | 16.0 | 0.044 | 0.16 | 0.5 | 0.32 | 53, 108 | ||||

| ADC-68 | 1.66 | 147.7 | 0.01 | 18.5 | 117.5 | 0.16 | 108 | ||||

| ADC-11 | 0.01 | 10 | 0.001 | 0.2 | 2.5d | 0.1 | 1 | 1800 | 5.5 · 10−4 | 248 | |

| ADC-33 | 4 | 30 | 0.13 | 1 | 0.5d | 2 | 10 | 1300 | 7.7 · 10−3 | 248 | |

| ADC-1 | 1.255 | 265 | 4.7 · 10−3 | 207 | |||||||

| ADC-5 | 0.011 | 232 | 4.7 · 10−5 | 207 | |||||||

| ADC-5 | P167S | 2.5 · 10−3 | 120 | 2.1 · 10−5 | 207 | ||||||

| ADC-5 | P167S/D242G/ Q163K/G342R | 1.235 | 90 | 0.014 | 207 | ||||||

| ADC-30 | 0.05 | 1.39 | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.51 | 0.32 | 57 | ||||

| ADC-56 | 0.1 | 1.42 | 0.07 | 0.27 | 1 | 0.27 | 0.2 | 17.17 | 0.011 | 57 | |

| PDC | |||||||||||

| PDC-1 | 0.004 | 20 | 2 · 10−4 | 0.02 | 6 | 3.3 · 10−3 | 0.08 | 800 | 1 · 10−4 | 68 | |

| PDC-2 | 0.01 | 20 | 5 · 10−4 | 0.15 | 5 | 0.03 | 2 | 850 | 2.4 · 10−3 | 68 | |

| PDC-3 | 0.02 | 35 | 5.7 · 10−4 | 0.15 | 8 | 0.019 | 2 | 1300 | 1.5 · 10−3 | 68 | |

| PDC-5 | 0.015 | 30 | 5 · 10−4 | 0.1 | 5 | 0.02 | 2.5 | 1700 | 1.5 · 10−3 | 68 | |

| PDC-5 | 0.01 | 7.3 | 1.3 · 10−3 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.5 | >0.15 | >250 | 6 · 10−4 | 402 | |

| PDC-5 | N346Y | 0.06 | 19 | 3.2 · 10−3 | 0.2 | 1.2 | 0.17 | >0.17 | >300 | 5.5 · 10−4 | 402 |

NM, kcat not measurable; ND, not determined.

Strain names are underlined.

Value computed from kcat and Km, which is different from the value reported in the original paper.

Ki values (μM) were determined instead of Km values, using cephalothin as a reporter substrate.

In P. aeruginosa, acquired resistance to amino- and ureidopenicillins, cephamycins, and, at low levels, to oxyiminocephalosporins (ceftazidime, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone) and monobactams (aztreonam), is frequently related to overproduction of the AmpC β-lactamase (14, 68, 185, 187, 229). ESACs emerged in P. aeruginosa several years after Enterobacterales, and such enzymes were identified mainly from clinical sources, but also from in vitro studies. They differ from the wild-type AmpC of P. aeruginosa by various amino-acid substitutions, deletions, or insertions in four regions in the vicinity of the active site: the Ω-loop, the H10-helix, the H2-helix, and the C-terminal end of the protein (69, 229, 230) (Table 5).

Genus Aeromonas may have been the origin of several chromosomal (e.g., MOX-3, MOX-10) or plasmid-encoded β-lactamases (e.g., MOX-1, MOX-2, CMY-1, CMY-8, CMY-19) identified on several occasions from clinical isolates, mostly in Enterobacterales (e.g., K. pneumoniae and E. coli). The first plasmid-encoded enzyme, MOX-1, was identified in a K. pneumoniae isolate with a high level of resistance to various broad-spectrum β-lactams, including moxalactam, flomoxef, ceftizoxime, cefotaxime, and ceftazidime (231). According to its kinetic parameters, cephalothin was its ideal substrate, and it had good activity against benzylpenicillin, but poor activity against cloxacillin and piperacillin. Moxalactam and cefoxitin were also hydrolyzed, but ceftazidime and cefepime were poor substrates, with very high Km values (Table 6). Finally, aztreonam was found to inhibit MOX-1 (232). The X-ray crystallographic structure of MOX-1 suggested that residues 303–306 show a significant structural flexibility, possibly underlying the unique substrate profile of this enzyme, which can hydrolyze penicillins, cephalothin, expanded-spectrum cephalosporins, cefepime, and moxalactam (156). The position of the H10-helix in both MOX-1 and CMY-10 is shifted further away from the catalytic serine residue compared with the AmpCs from E. coli, E. hormaechei P99 (formerly known as E. cloacae P99), and E. cloacae GC1, whereas that of the AmpC from P. aeruginosa occupies an intermediate position. Such structural features may underlie the extended substrate profile of MOX-1 and CMY-10, which are also considered to be ESBLs, but have never been called ESACs (110, 156). Finally, the susceptibility profile of these enzymes is characterized by a high level of hydrolysis for cephamycins, oxacephems (e.g., cefoxitin), and moxalactam, increased resistance to cefotaxime compared with ceftazidime and aztreonam, and resistance to cefpirome and/or cefepime (233–239). The deletion of three residues in the R2-loop (positions 301–303) appears to be responsible for the expanded spectrum activity of CMY-10, and further mutation around this deletion in the P99 enzyme extended its substrate spectrum by widening the R2 region (Table 5) (110). Globally, all chromosomal (e.g., MOX-3, MOX-10, MOX-11) or plasmid-encoded (e.g., MOX-1, MOX-2, MOX-14, CMY-1, CMY-8, CMY-8b, CMY-9, CMY-10, CMY-11, CMY-19) β-lactamases from this family feature the sequence 289AKVILEANPTAAΔΔΔPRESG309S in the conserved R2 region (25). An increase in resistance to cefepime was also achieved by an additional amino-acid substitution (I292S) in the H10-helix region, as observed in CMY-11 and CMY-19 relative to CMY-9 (236) (Table 5).

The other enzymes from Aeromonas include a cluster of plasmid-encoded FOX-type enzymes without the amino-acid deletion at positions 301–303. These enzymes have a susceptibility profile characterized by a higher degree of resistance to cefoxitin (the origin of the family name, FOX) and to ceftazidime compared with cefotaxime (240–244). No ESACs have been identified among FOX variants (22). A tripeptide deletion (286GN288S) in the R2-loop of E. coli HKY28 led to an extended hydrolysis spectrum, but the same deletion by site-directed mutagenesis in FOX-4 did not increase catalytic efficiency for ceftazidime, cefotaxime, or cefepime, despite large differences in Km and kcat values (Table 6). A decrease in the MIC for cefoxitin was obtained in both E. coli HKY28 and FOX-4 Δ286-288, together with a slight increase in susceptibility to clavulanate, sulbactam, and tazobactam (245).

Structural studies have confirmed the importance of the Ω- and R2-loops for modulating the catalytic activity of class C β-lactamases. In CMY-10, a three-amino acid deletion in the R2-loop appears to underlie the extended spectrum activity (110), whereas a two-amino-acid deletion in the R2-loop of CMH-family AmpC enzymes from E. cloacae Ent385 leads to reduced susceptibility to ceftazidime-avibactam and cefiderocol (109). Similarly, the Y221H mutation in CMY-136 induces an important change in the confirmation of the Ω-loop, widening the active site cavity and conferring resistance to many β-lactams and combinations, including ceftolozane-tazobactam (113).

NATURAL ESACs

The term “naturally occurring ESAC” has been proposed for the enzymes in E. coli isolates with increased hydrolysis of oxyiminocephalosporins, including cefepime and cefpirome (MICs greater than or equal to 16 μg/mL and 0.5 μg/mL for ceftazidime and cefepime, respectively, without a positive synergy test with clavulanic acid), and resistance to amoxicillin and to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (16). As for class A ESBLs, which are sometimes encoded by chromosomal genes (e.g., OXY-types for K. oxytoca) (246), both chromosomal and natural ESACs have been identified in A. baumannii (53), in which these β-lactamases are the principal source of resistance (49). The genes encoding ADC-type β-lactamases are non-inducible and generally expressed at low levels, resulting in resistance to penicillins and narrow-spectrum cephalosporins (51, 247). However, overexpression may be observed following the acquisition of an IS element, principally ISAba1, providing a strong promoter, and this may lead to resistance to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins (cefotaxime, ceftazidime) and aztreonam (207). All ADC-type β-lactamases (about 450 protein sequences examined) are characterized by a deletion of three residues (positions 304–306) in the R2-loop that enhances their catalytic efficiency against these clinically important drugs compared with enzymes without this deletion (53, 54, 108). Clinical variants with higher levels of resistance (4- to 64-fold increase) have been detected, with V211A (Ω-loop) or N287S (H10-helix) substitutions (56) (Table 5). Moreover, acquired resistance to cefepime or cefpirome and increased hydrolysis efficiency (ESAC) were induced by the P210R substitution and duplication of A215 in the Ω-loop (ADC-33) or by the substitution R148Q in the P2-loop (ADC-56) (57, 248). ADC-68 has seven amino-acid substitutions compared with ADC-1, one of which (321G) is located in the C-loop and another two (192A and 217D) in the Ω-loop. The overall structures of ADC-68 and ADC-1 are conserved, but there are marked structural differences in the Ω-loop and the C-loop. In particular, residues 217D and 321G in ADC-68 make a major contribution to the structural differences between these two ADC-type β-lactamases (108).

There is a two-amino acid deletion (residues 301–302) in the R2-loop of AmpC from two species, A. dhakensis and A. caviae (25), but an equivalent deletion in AQU-1 does not seem to affect the usual β-lactam resistance phenotype. However, cefotaxime monotherapy should be used with caution for severe A. dhakensis infections, because such treatment could lead to the selection of variants with constitutively high levels of β-lactamase production. Nevertheless, cefepime susceptibility was conserved in all cases studied (249).

A specific structural alteration to the R2-loop (deletion of two amino acids in positions 289–290) was observed in all Hafnia protein sequences, and this feature is unique among Enterobacterales (25, 33, 88) (Table 5). Furthermore, ACC-1 confers an unusual and unique pattern of susceptibility to β-lactams, with higher MICs for ceftazidime and cefotaxime than for cefoxitin (4, 240). In addition to the two-amino-acid deletion in positions 289–290 mentioned above, ACC-1 features two other remarkable structural alterations, one in the Ω-loop (213ME instead of 213PG) and another along the active-site rim (120F instead of 120Q) (25, 88). Moreover, ACC-2, a cephalosporinase encoded by an inducible chromosomal gene, displays marked hydrolysis activity against cefpirome in particular (250), in opposition to the widely accepted view that cefpirome is resistant to hydrolysis by class C enzymes, even when they are overproduced (251). ACC-2 is also strongly inhibited by cefoxitin (250).

In conclusion, these natural ESACs constitute a threat because of their resistance to cefepime and/or cefpirome, or even to carbapenems if they are overproduced, combined with porin loss and/or efflux pump activation.

CARBAPENEM RESISTANCE

Carbapenem resistance has become a serious threat to public health (252). It has spread worldwide in Gram-negative bacteria, and is continuing to increase due to the production of plasmid-encoded carbapenemases by Enterobacterales and by nonfermenting organisms (mainly A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa) (253, 254). The main mechanism underlying carbapenem resistance is the production of highly transmissible carbapenemases, such as KPC-types (class A), IMP-, NDM-, or VIM-types (class B), and OXA-types (class D). Carbapenems, which diffuse efficiently across the native outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, are poor substrates for class C β-lactamases (4). However, they may act as inhibitors in some cases, due to the high affinity of AmpCs for these antibiotics, suggesting that resistance may be acquired by a mechanism known and sometimes described as “trapping” (255), in which the cephalosporinase has a good affinity for the substrate combined with a very slow hydrolysis (256–259).

Nevertheless, several clinical failures and in vitro studies have been published concerning chromosomally encoded and transmissible class C β-lactamases with weak carbapenem hydrolysis activity, suggesting poor carbapenemase activity (253, 260, 261). Such resistance was always obtained from the combination of a high production of β-lactamase (a hyperproducing mutant of a chromosomally-encoded enzyme or a plasmid-mediated enzyme) with another mutation-driven mechanism, such as porin loss (OmpC, OmpF, OmpG, OmpK35, OmpK36) or efflux overexpression, which was essential for carbapenem resistance, preferentially against ertapenem, then imipenem, and finally meropenem (240, 262) (Table 7). The prevalence of such nonenzymatic mechanisms is low and differs between bacteria, with relatively few occurrences among Enterobacterales (mostly in K. pneumoniae, but also in E. coli, P. mirabilis, and S. enterica).

TABLE 7.

Chromosomal or plasmid-encoded class C β-lactamases: mechanisms of acquired resistance to carbapenems

| Fold-increase MICsc |

Reference | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bla or straina | Species | Locationb | Mechanisms | CAZ | FEP | IMP | ERT | MER | |

| MEV | E. coli | Chr | ESAC + OmpC decrease + OmpF loss | >128 | >16 | 8 | >16 | 8 | 368 |

| ACC-1 | E. coli | P | + OmpC/OmpF loss | >64 | 64 | 4 | >128 | 4 | 240 |

| ACT-1 | E. coli | P | + OmpC/OmpF loss | >256 | >16 | 128 | >512 | 32 | 240 |

| CMY-2 | E. coli | P | + OmpC/OmpF loss | >256 | >16 | 256 | >512 | 256 | 240 |

| DHA-1 | E. coli | P | + OmpC/OmpF loss | >512 | 64 | 16 | 256 | 8 | 240 |

| FOX-1 | E. coli | P | + OmpC/OmpF loss | >512 | >128 | 4 | >256 | 16 | 240 |

| CMY-2 | E. coli | P | Overproduction + OmpC/OmpF loss | >256 | >16 | >64 | >256 | >32 | 403 |

| CMY-2 | E. coli | P | Overproduction + OmpC insertion IS1 | >64 | >256 | 260 | |||

| CMY-2 | E. coli | P | Overproduction + OmpC/OmpF loss | >256 | >128 | >256 | >512 | 258 | |

| EC14 | E. coli | Chr | ESAC + OmpC/OmpF loss | >256 | >128 | 16 | >32 | 1 | 404 |

| CMY-4 | S. enterica | P | + OmpF loss | >512 | >64 | >16 | 405 | ||

| ACT-1 | K. pneumoniae | P | + Omp42-kDa loss | >128 | 8-32 | 8->16 | 322 | ||

| ACT-1 | K. pneumoniae | P | + OmpK35/36 insertion + PhoE decrease | 64-256 | 128 | 256 | 406 | ||

| DHA-1 | K. pneumoniae | P | + OmpK36 loss | >128 | >32 | >32 | 407 | ||

| DHA-1 | K. pneumoniae | P | + OmpK35/36 loss + AcrAB/OqxAB | 32 | >32 | 277 | |||

| ACC-1 | K. pneumoniae | P | + OmpK35/36 loss | >128 | 16 | 8 | 32 | 16 | 262 |

| FOX-1 | K. pneumoniae | P | + OmpK35/36 loss | >512 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 64 | 262 |

| MOX-1 | K. pneumoniae | P | + OmpK35/36 loss | 64 | 8 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 262 |

| EA-Z | K. aerogenes | Chr | + Omp40-kDa loss | 16 | 408 | ||||

| E15 | K. aerogenes | Chr | + OmpK35/36 loss | >256 | >16 | >16 | 409 | ||

| E11 | E. cloacae | Chr | Overproduction + OmpK35/36 loss | >256 | >16 | >16 | 409 | ||

| 144 | E. cloacae | Chr | Overproduction + porin loss | 64 | 16 | >128 | 410 | ||

| 213 | P. rettgeri | Chr | Overproduction + porin loss | 4 | 8 | >128 | 410 | ||

| ACT-28 | E. kobei | Chr | Overproduction + OmpC-like protein | >256 | >64 | >128 | >512 | >512 | 264 |