ABSTRACT

This article describes the introduction of the Pan American Health Organization’s HEARTS in the Americas program in Trinidad and Tobago and the successful experiences and challenges encountered in introducing and scaling it up as a strategy for strengthening the health system’s response to cardiovascular diseases. Evidence about implementation of the HEARTS program in the World Health Organization’s Region of the Americas was reviewed to identify the progress made, barriers, success factors and lessons learned. In 2019, the Ministry of Health commenced implementation of the program in 5 (4.9%) of the 102 primary health care centers, and by the end of 2021, it had been scaled up to 46 (45.0%) centers. The HEARTS program ensures that patients’ cardiovascular health is managed in a comprehensive way through providing counseling about a healthy lifestyle, using evidence-based treatment protocols, ensuring access to essential medicines and technologies, and using a risk-based team approach, a monitoring and evaluation system and also a team-based approach to care delivery. The barriers encountered during implementation included the fragmentation of the existing health care system, the paternalistic role assumed by health care professionals, the resistance of some health care workers to change and a lack of team-based approaches to providing care. Successful implementation of the program was enabled through ensuring high-level political commitment, establishing the national HEARTS Oversight Committee, ensuring stakeholder involvement throughout all phases and implementing standardized approaches to care. When implemented in the context of existing primary health care settings, the HEARTS program provides an exceptionally well integrated and comprehensive model of care that embodies the principles of universal health care while ensuring the health of both populations and individuals. Thus, it enables and promotes a strengthened primary health care system and services that are responsive and resilient.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, primary health care, health systems, patient-centered care, Trinidad and Tobago

RESUMEN

En este artículo se describe la introducción del programa HEARTS en las Américas de la Organización Panamericana de la Salud en Trinidad y Tabago y las experiencias satisfactorias y los desafíos encontrados con su ejecución y ampliación como estrategia para fortalecer la respuesta del sistema de salud a las enfermedades cardiovasculares. Se reunieron datos sobre la ejecución del programa HEARTS en la Región de las Américas de la Organización Mundial de la Salud con el fin de determinar cuáles han sido los avances, los obstáculos, los factores de éxito y las enseñanzas extraídas. En el año 2019, el Ministerio de Salud inició la ejecución del programa en cinco (4,9%) de los 102 centros de atención primaria de salud, y para fines del 2021, se había ampliado a 46 (45,0%). El programa HEARTS garantiza el manejo integral de la salud cardiovascular de los pacientes mediante la prestación de asesoramiento sobre hábitos saludables, la aplicación de protocolos de tratamiento basados en la evidencia, la garantía de acceso a medicamentos y tecnologías esenciales, así como el uso de un enfoque de trabajo en equipo basado en el riesgo, un sistema de monitoreo y evaluación, y un enfoque basado en el equipo para abordar la prestación de la atención. Entre los obstáculos para su ejecución se encontraron la fragmentación del sistema de atención médica, el papel paternalista asumido por los profesionales de la salud, la resistencia al cambio de algunos trabajadores de salud y la falta de enfoques de trabajo en equipo para la prestación de la atención. La ejecución satisfactoria del programa fue posible gracias a un compromiso político de alto nivel, la creación de un comité nacional de supervisión de HEARTS, la participación de las partes interesadas en todas las fases del programa y la aplicación de enfoques estandarizados para la atención. En su ejecución en el contexto de los entornos de atención primaria de salud existentes, el programa HEARTS proporciona un modelo de atención excepcionalmente bien integrado y exhaustivo que encarna los principios de acceso universal a la atención de salud al tiempo que garantiza la salud individual y poblacional. De este modo, este modelo fomenta un sistema de atención primaria de salud fortalecido y unos servicios receptivos y resilientes.

Palabras clave: Enfermedades cardiovasculares, atención primaria de salud, sistemas de salud, atención dirigida al paciente, Trinidad y Tobago

RESUMO

Este artigo descreve a introdução do programa HEARTS nas Américas da Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde em Trinidad e Tobago e as experiências bem-sucedidas e os desafios encontrados durante a introdução e expansão do programa como estratégia para fortalecer a resposta do sistema de saúde às doenças cardiovasculares. Analisaram-se evidências sobre a implementação do programa HEARTS na Região das Américas da Organização Mundial da Saúde para identificar os avanços obtidos, os obstáculos, os fatores de sucesso e as lições aprendidas. Em 2019, o Ministério da Saúde iniciou a implementação do programa em 5 (4,9%) dos 102 centros de atenção primária à saúde; no final de 2021, o programa havia sido ampliado para 46 (45,0%) centros. O programa HEARTS assegura que a saúde cardiovascular dos pacientes seja manejada de uma forma abrangente por meio de aconselhamento sobre estilo de vida saudável, uso de protocolos de tratamento baseados em evidências, garantia de acesso a medicamentos e tecnologias essenciais e utilização de uma estratégia de equipe baseada no risco, de um sistema de monitoramento e avaliação e de uma abordagem de atendimento baseado em equipe. Os obstáculos encontrados durante a implementação incluíam a fragmentação do sistema de saúde existente, o papel paternalista assumido pelos profissionais de saúde, a resistência de alguns profissionais de saúde a mudanças e a falta de abordagens baseadas em equipe na prestação do atendimento. Para permitir que a implementação do programa fosse bem-sucedida, obteve-se compromisso político de alto nível, criou-se o Comitê de Supervisão do HEARTS nacional, assegurou-se o envolvimento de interessados diretos em todas as fases e implementaram-se abordagens padronizadas de atendimento. Quando implementado no contexto dos ambientes existentes de atenção primária à saúde, o programa HEARTS oferece um modelo de atenção excepcionalmente bem integrado e abrangente que incorpora os princípios de atenção universal à saúde, ao mesmo tempo em que garante a saúde das populações e dos indivíduos. Dessa forma, viabiliza e promove um sistema de atenção primária à saúde fortalecido e serviços responsivos e resilientes.

Palavras-chave: Doenças cardiovasculares, atenção primária à saúde, sistemas de saúde, assistência centrada no paciente, Trinidad e Tobago

Trinidad and Tobago is a twin-island state located in the southern Caribbean, approximately 10 miles north-east of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, with a population of approximately 1.35 million. It has an ethnically diverse population of people of African, East Indian and mixed origins. The population has a median age of 32.6 years, and 13.3% of the population is older than 60 years (1). Life expectancy at birth is 73.4 years: for females it is 76.1 years and for males it is 70.6 years (2).

Annually, more than 65% of deaths are caused by noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), with heart disease accounting for 23.0%, diabetes for 17.0%, cancers for 17.0% and stroke for 9.0% (3). Of deaths from NCDs, 52.0% occur in males and 41.0% in females (Central Statistical Office, unpublished data, 2018). The Pan American STEPwise approach to NCD risk factor surveillance (also known as STEPS) survey in 2011 identified the main contributing factors for NCDs as tobacco use, insufficient daily consumption of fruits and vegetables, physical inactivity, overweight and obesity, and raised blood pressure (3). Altogether, 51.0% of the population between the ages of 25 and 64 years has three or more risk factors for NCDs and, therefore, is at increased risk of developing an NCD at an earlier age than previous generations (3). The leading risk factor for cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) in Trinidad and Tobago is hypertension, with an adult prevalence of 26.3%: the prevalence is higher in males, at 29.8%, than in females, at 23.1% (3). However, hypertension is preventable (4).

Responding to NCDs places a significant economic burden on the Government of Trinidad and Tobago. The estimated annual economic cost incurred from hypertension is $ 3.2 billion Trinidad and Tobago dollars (US$ 474 million) and from diabetes is $ 3.5 billion Trinidad and Tobago dollars (US$ 3.532 million). Collectively, this represents 3.9% of the country’s gross domestic product (5). In this context, the Ministry of Health decided to prioritize NCD prevention and control and developed the National Strategic Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases: 2017–2021 to guide the country’s response (5). The National NCD Plan identified four priority areas for its strategic response: risk factor reduction and health promotion, comprehensive and integrated care and management of NCDs, surveillance, and governance and advocacy.

The operationalization of the National NCD Plan is led by the Ministry of Health and implemented through five Regional Health Authorities (RHAs), which provide an agreed basket of primary, secondary and tertiary health services at no cost to the public. There are 102 RHAs and primary health care facilities and 10 secondary- and tertiary-level hospitals within the public health system, thus affording easy access to primary care services.

The Global Hearts Initiative was developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) in collaboration with the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Resolve to Save Lives, the World Hypertension League and other partners. In WHO’s Region of the Americas, the Hearts Initiative has been regionally adapted as HEARTS in the Americas. The HEARTS program uses evidence-based interventions, in a technical package that includes six modules, to improve the prevention and control of CVDs, with control of hypertension as the entry point to the cascade of care (6). A main feature of the HEARTS program is the use of a simplified, standardized hypertension treatment algorithm that recommends using two antihypertensive medicines in a fixed-dose combination to treat hypertension (7). Other key features are expanded roles for members of the health care team, which are accomplished through task-shifting within the primary care setting, and the emphasis on monitoring using simple patient registries to track blood pressure control.

The model used by HEARTS in the Americas is one that facilitates the integrated management of hypertension, pharmacological management guided by an algorithm, strengthening of nonpharmacological management methods, and increasing patient participation and strengthening community linkages to create a supportive environment for the lifestyle changes recommended.

HEARTS in the Americas has been implemented in 22 countries in the Region. Barbados was the first country in the Region to pilot the initiative in 2014, followed by Chile, Colombia and Cuba in 2016 (8). Since then, different cohorts of three to four countries have started implementing the program. Country participation in HEARTS is voluntary, and the intervention is led by Ministries of Health, with technical support provided by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) to adapt and integrate the program into each country’s primary care service-delivery system. The levels of progress and scale up differ among countries, but despite the challenges, the HEARTS program has been successfully implemented.

The purpose of this article is to describe the introduction of the HEARTS program in Trinidad and Tobago and the successes and challenges encountered during introduction and scale up as a strategy for strengthening the health system’s response to CVDs.

Trinidad and Tobago was introduced to the Global Hearts Initiative in May 2018 at a national symposium that focused on strengthening primary care. The initiative was presented by PAHO’s HEARTS in the Americas team as an innovative strategy that uses the chronic care model while strengthening primary care. It is operationalized by integrating the HEARTS technical package into the primary care service-delivery system, providing evidence-based best practices for improving hypertension control by using an integrated care and management approach; the package also strengthens the performance of the health system at the primary health care level (6). The HEARTS technical package is composed of healthy lifestyle counseling, evidence-based treatment protocols, access to essential medicines and technologies, risk-based care, team-based care, systems for monitoring and a diabetes module.

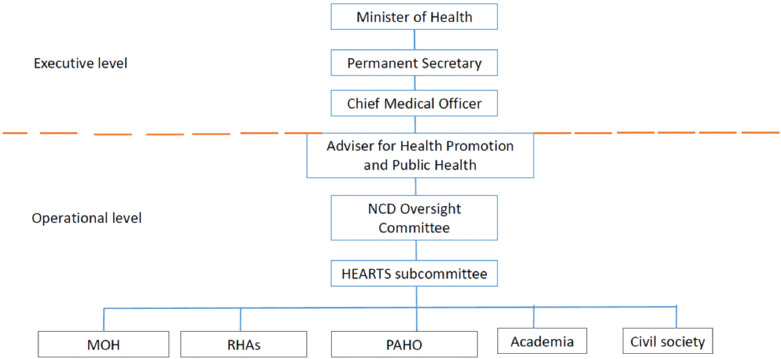

The Trinidad and Tobago Ministry of Health assessed HEARTS as being aligned with the National NCD Plan, and in July 2018, the country formally joined the second cohort aiming to implement HEARTS in the Americas. Planning to develop and implement the HEARTS program began immediately. A governance mechanism was established and linked to the Ministry’s governance and oversight mechanism for the National NCD Plan. The HEARTS Oversight Subcommittee was established as a subcommittee of the national NCD Oversight Committee. Both committees share a common chairperson and are multisectoral in nature, with participation from the RHAs, PAHO, academia and civil society (Figure 1). The general managers of primary health care (one in each RHA) and County Medical Officers of Health, as administrators in charge of primary health care services, represent the RHAs on the HEARTS Subcommittee. This structure provides an integrated governance mechanism, allowing for rapid communication and decision-making throughout the continuum of the Ministry’s management and the RHAs – that is, the operational level responsible for implementing the HEARTS technical package at the primary health care level (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Governance structure for the HEARTS in the Americas program in Trinidad and Tobago, 2019.

MOH: Ministry of Health; NCD: noncommunicable disease; PAHO: Pan American Health Organization; RHAs: Regional Health Authorities.

Source: Used with permission from the unpublished HEARTS terms of reference.

HEARTS implementation commenced in five primary health care centers in 2019, one in each RHA, representing 4.9% (5/102) of primary care facilities nationally. A monitoring and evaluation mechanism was established, guided by the HEARTS Systems for Monitoring module (7). The core indicators at the health facility level are: coverage of hypertension care, hypertension control, and the availability of core medicines for CVD and diabetes.

To develop this article we reviewed documents relating to implementation of the HEARTS program in Trinidad and Tobago. However, there is no published literature about this, so we reviewed reports and postimplementation assessments. Five national reports were available, and each was reviewed using a standardized process. Members of the team independently reviewed each report and identified key elements associated with the progress of implementation, barriers, enabling factors and lessons learned. Following the independent review, the findings were consolidated based on consensus. Two members who did not participate in the initial assessment served as reviewers and validated the findings.

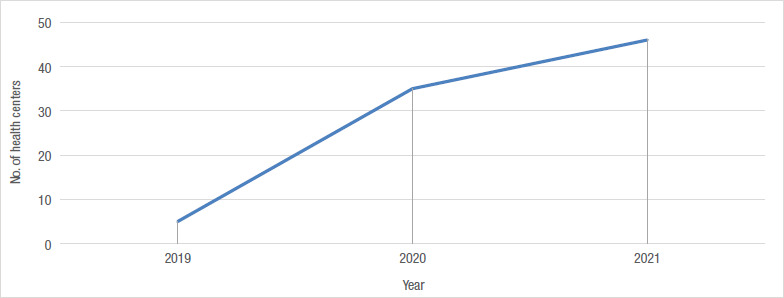

In Trinidad and Tobago, the HEARTS program was scaled up gradually, starting with five facilities in 2019, increasing to 35 facilities (34.3%) by January 2020 and to 46 facilities (45.0%) in July 2021, with a total catchment population of approximately 550 000 people (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Number of health centers implementing the HEARTS in the Americas program, by year, Trinidad and Tobago, 2019–2021.

Source: Figure prepared by the authors from data used with permission from the Regional Health Authorities in Trinidad and Tobago.

Two RHAs achieved and maintained 100% scale up of the health centers in their regions by 2020, while another RHA achieved and maintained 69.0% scale up during the same period. Two RHAs did not scale up HEARTS beyond the initial health center. The main reason for successful scale up in the three RHAs was that they established implementation teams early in the process. Additionally, the two RHAs with 100% scale up have relatively small catchment populations that are reasonably accessible. Among the more successful RHAs, there was more widespread sensitization of all levels of staff along with a strong team approach that was led by a HEARTS focal point. Human resources limitations and other administrative issues impacted the scale up in the less-successful RHAs. Although the COVID-19 pandemic affected all RHAs, the two RHAs that did not scale up beyond the initial sites were more significantly impacted as staff from both primary and secondary care were redirected to the COVID-19 acute care facilities. During the pandemic, a parallel health system was established to manage acute COVID-19 cases in an effort to maintain delivery of essential health services. However, many of these acute care facilities were within these two RHAs. Furthermore, the catchment area for one of these RHAs accounts for more than half of the country’s population.

However, improvements were noted in both hypertension coverage (defined as the number of persons with hypertension who are diagnosed and being managed in the health center) and control (defined as blood pressure < 140/90). In the two regions that achieved 100% scale up of the HEARTS program, data provided for 2019–2021 indicated that as of June 30, 2021: in the North Central Regional Health Authority, mean coverage of hypertension care was 45.0% at the level of individual health centers (range, 13.0% to 87.0%), with initial coverage in January 2019 of 20.0%; the Tobago Regional Health Authority achieved 29.0% mean coverage of hypertension care at the health-center level (range, 16.0% to 85.0%), with initial coverage in January 2019 of 17.0%.

Data provided by the five health centers (one from each RHA) where HEARTS was first introduced, revealed that hypertension control increased in all centers. Two of the primary health care centers increased blood pressure control by 16.0% and 21.0% (Table 1). The total catchment population of these initial five health centers is approximately 150 000, with almost 9 000 hypertensive patients.

TABLE 1. Progress in hypertension control in the five health centers where HEARTS in the Americas was first introduced in Trinidad and Tobago, 2019–2020.

|

Primary health care center |

% of patients with controlled hypertension |

Difference in % with controlled hypertension |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

At baseline (July 2019) |

6 months after implementation (January 2020) |

||

|

Arima |

30.0 |

51.0 |

+21.0 |

|

Freeport |

30.0 |

31.0 |

+1.0 |

|

Oxford Street |

33.0 |

36.8 |

+3.8 |

|

Sangre Grande |

20.0 |

36.0 |

+16.0 |

|

Scarborough (Tobago) |

29.0 |

32.0 |

+3.0 |

Source: Table prepared by the authors from data used with permission from the Regional Health Authorities (Trinidad and Tobago Hypertension Report, unpublished data, 2020).

To facilitate scaling up of the initiative, a training-of-trainers approach was taken, and a multidisciplinary team was trained to be master trainers. These master trainers provided training and sensitization sessions in each RHA. In addition, a range of primary care staff completed courses through PAHO’s Virtual Campus for Public Health in 2021 and 2022. Altogether 148/210 people who registered for training on implementing the HEARTS technical package were certified; 79/138 were certified in accurately using automated blood pressure measurement; and 25/36 were certified to manage hypertension and CVD risks in primary care.

The HEARTS healthy lifestyle counseling module was used to strengthen the use of nonpharmacological strategies for risk reduction by training staff at centers implementing the program, expanding such counseling by the multidisciplinary heath team and building patients’ self-management skills. All members of staff were involved in delivering basic counseling about a healthy lifestyle, learning to correctly measure blood pressure and monitor blood pressure daily, using the brief tobacco interventions and providing information on recommendations for daily physical activity. The dietetic departments in each RHA also implemented a structured program of dietary education and counseling for all clients.

To further strengthen the patient-centered approach to improving hypertension management and control, the Ministry of Health partnered with PAHO to implement the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (9). The self-management program is an evidence-based, standardized protocol that facilitates skill-building and behavior change to improve the management of chronic conditions. The Program is delivered during 6 weeks to persons with NCDs or their caregivers at health centers or by nongovernmental organizations, community-based organizations and faith-based organizations. In Trinidad and Tobago, a cohort of 12 Program leaders was trained during March and April 2021. These lead trainers expanded the training in their respective community or organization, which resulted in approximately 120 persons with NCDs completing the 6-week Program. During the COVID-19 pandemic, both the leader trainings and the community trainings were delivered virtually.

Critical to the successful implementation of the HEARTS program was the phased approach to its introduction, allowing for the development of the infrastructure, ensuring consensus among the stakeholders and allowing the technical package to be adapted to the local context. Some key areas of focus for adapting the package were developing the monitoring and evaluation framework and the reporting protocols, establishing baseline data, developing the hypertension treatment algorithm to include the fixed-dose combination medicines and developing an implementation plan.

Trinidad and Tobago’s Chronic Disease Assistance Program is a prescription-based program available throughout the country that includes more than 240 private pharmacies and allows persons to fill prescriptions from public health centers at no cost to them. Adjusting the national formulary to include the medications recommended in the hypertension treatment protocol ensures universal access to antihypertensives for all patients both in public and private health care settings, and it further strengthens patient-centered care by facilitating access to essential medications that are easy for patients to use.

The increased focus on using patient-centered approaches to improve CVD management and control enabled staff to expand their capacities through the training conducted by the HEARTS master trainers and PAHO’s Virtual Campus for Public Health, thus increasing staff competency and the quality of information available to patients. Implementation of the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program is anticipated to build patient self-efficacy and create informed and empowered patients. It is also anticipated that advances in CVD care will result from the combination of the use of fixed-dose medicines for treatment, a well-trained health care team and improved patient management skills.

Progress can be hindered by some of the inherent system barriers found in Trinidad and Tobago, such as a fragmented health care system, the paternalistic role taken by some health care professionals, health care workers’ resistance to change and a lack of a team-based approach to patient care. Trinidad and Tobago’s experience proved that high-level political commitment combined with the establishment of a suitable governance mechanism, stakeholder involvement at all levels and a standardized approach to care were enabling factors for the successful implementation of the HEARTS program. As a strategy for health system strengthening, the HEARTS program has shown that despite the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, opportunities can be created to facilitate quick adoption to improve patient-centered, integrated care. Therefore, the HEARTS program, when implemented within existing primary health care settings, is an exceptionally integrated and comprehensive model of care that embodies the principles of universal health care while addressing the health care needs of populations and individuals. Thus, it enables and promotes strengthened primary health care systems and services that are responsive and resilient.

Disclaimer.

Authors hold sole responsibility for the views expressed in the manuscript, which may not necessarily reflect the opinion or policy of the Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública/Pan American Journal of Public Health or the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), the Ministry of Health of Trinidad and Tobago, the Regional Health Authorities of Trinidad and Tobago or the University of the West Indies.

Acknowledgements.

The authors thank PAHO, the Ministry of Health and the Regional Health Authorities for their support in the development and implementation of the HEARTS program. A special thanks is given to the health staff at each HEARTS-implementing site for providing the relevant information that led to the development of each report from which information was taken for this manuscript.

Funding Statement

Technical and financial support were provided by PAHO for the integration of the HEARTS program in Trinidad and Tobago as part of its technical cooperation agreement. PAHO was not involved in any way in designing the study, collecting and analyzing the data, deciding to publish this paper or in preparing the manuscript. The authors who are staff of or interns at PAHO voluntarily participated in the development of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions.

RD, TM, LH and LG conceived the original article and developed the abstract. AH and PL, with RD, TM, LH and LG, drafted the outline of the manuscript. AH collected and analyzed the data and drafted the table and figures. LH conducted the literature review. YL consolidated the sections of the manuscript that had been drafted by different authors, drafted the discussion and produced a first draft of the manuscript. AB and RM independently reviewed the draft manuscript and provided feedback. LG reviewed the final draft of the manuscript. RD and TM coordinated and were involved in all areas of manuscript development. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest.

None declared.

Funding.

Technical and financial support were provided by PAHO for the integration of the HEARTS program in Trinidad and Tobago as part of its technical cooperation agreement. PAHO was not involved in any way in designing the study, collecting and analyzing the data, deciding to publish this paper or in preparing the manuscript. The authors who are staff of or interns at PAHO voluntarily participated in the development of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Government of Trinidad and Tobago, Central Statistical Office . 2011 population and housing census demographic report. Port of Spain: Ministry of Planning and Development, Central Statistical Office; 2012. [cited 2022 March 29]. Internet. Available from https://cso.gov.tt/stat_publications/2011-population-and-housing-census-demographic-report/ [Google Scholar]; Government of Trinidad and Tobago, Central Statistical Office. 2011 population and housing census demographic report [Internet]. Port of Spain: Ministry of Planning and Development, Central Statistical Office; 2012 [cited 2022 March 29]. Available from: https://cso.gov.tt/stat_publications/2011-population-and-housing-census-demographic-report/.

- 2.The World Bank . Life expectancy at birth, total (years) – Trinidad and Tobago. Washington (DC): World Bank Group; 2019. [cited 2022 March 29]. Internet. Available from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.IN?locations=TT. [Google Scholar]; The World Bank. Life expectancy at birth, total (years) – Trinidad and Tobago [Internet]. Washington (DC): World Bank Group; 2019 [cited 2022 March 29]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.IN?locations=TT

- 3.Government of Trinidad and Tobago, Ministry of Health . Trinidad and Tobago chronic non-communicable disease risk factor survey (Pan American STEPS): final report. Port of Spain: Ministry of Health, Trinidad and Tobago; 2012. [Google Scholar]; Government of Trinidad and Tobago, Ministry of Health. Trinidad and Tobago chronic non-communicable disease risk factor survey (Pan American STEPS): final report. Port of Spain: Ministry of Health, Trinidad and Tobago; 2012.

- 4.World Health Organization . Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/148114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/148114 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Government of Trinidad and Tobago, Ministry of Health . National strategic plan for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases: Trinidad and Tobago 2017–2021. Port of Spain: Ministry of Health; 2017. [Google Scholar]; Government of Trinidad and Tobago, Ministry of Health. National strategic plan for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases: Trinidad and Tobago 2017–2021. Port of Spain: Ministry of Health; 2017.

- 6.World Health Organization . Technical package for cardiovascular disease management in primary health care: systems for monitoring. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/260423 [Google Scholar]; World Health Organization. Technical package for cardiovascular disease management in primary health care: systems for monitoring. Geneva: World Health Organization: 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/260423

- 7.DiPette DG, Goughnour K, Zuniga E, Skeete J, Ridley E, Angell S, et al. Standardized treatment to improve hypertension control in primary health care: the HEARTS in the Americas Initiative. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2020;22:2285–2295. doi: 10.1111/jch.14072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; DiPette DG, Goughnour K, Zuniga E, Skeete J, Ridley E, Angell S, et al. Standardized treatment to improve hypertension control in primary health care: the HEARTS in the Americas Initiative. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2020;22:2285-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Giraldo GP, Joseph KT, Angell SY, Campbell NRC, Connell K, DiPette DJ, et al. Mapping stages, barriers and facilitators to the implementation of HEARTS in the Americas initiative in 12 countries: a qualitative study. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2021;23:755–765. doi: 10.1111/jch.14157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Giraldo GP, Joseph KT, Angell SY, Campbell NRC, Connell K, DiPette DJ, et al. Mapping stages, barriers and facilitators to the implementation of HEARTS in the Americas initiative in 12 countries: a qualitative study. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2021;23:755-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Self-Management Resource Center . Chronic disease self-management program. Aptos (CA): Self-Management Resource Center; 2022. [cited 29 March 2022]. Available from https://selfmanagementresource.com/programs/ [Google Scholar]; Self-Management Resource Center. Chronic disease self-management program. Aptos (CA): Self-Management Resource Center; 2022 [cited 29 March 2022]. Available from https://selfmanagementresource.com/programs/