Abstract

Transposon mutagenesis of Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 led to the isolation of a mutant strain, SNa1, which is unable to fix nitrogen aerobically but is perfectly able to grow with combined nitrogen (i.e., nitrate). Reconstruction of the transposon mutation of SNa1 in the wild-type strain reproduced the phenotype of the original mutant. The transposon had inserted within an open reading frame whose translation product shows significant homology with a family of proteins known as high-molecular-weight penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), which are involved in the synthesis of the peptidoglycan layer of the cell wall. A sequence similarity search allowed us to identify at least 12 putative PBPs in the recently sequenced Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 genome, which we have named and organized according to predicted molecular size and the Escherichia coli nomenclature for PBPs; based on this nomenclature, we have denoted the gene interrupted in SNal as pbpB and its product as PBP2. The wild-type form of pbpB on a shuttle vector successfully complemented the mutation in SNa1. In vivo expression studies indicated that PBP2 is probably present when both sources of nitrogen, nitrate and N2, are used. When nitrate is used, the function of PBP2 either is dispensable or may be substituted by other PBPs; however, under nitrogen deprivation, where the differentiation of the heterocyst takes place, the role of PBP2 in the formation and/or maintenance of the peptidoglycan layer is essential.

Filamentous cyanobacteria such as Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 perform oxygenic (i.e., higher plant-type) photosynthesis. When grown in the presence of fixed nitrogen, all the cells have similar morphology and are known as vegetative cells. When the filaments are deprived of nitrogen, a small percentage of the vegetative cells of Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 differentiates into nitrogen-fixing heterocysts (36) that are semiregularly spaced along the filament generating a pattern (5, 37, 38, 41, 43). Protection of nitrogenase from inactivation by oxygen appears to depend, to a great extent, on a barrier to the diffusion of oxygen and other gasses through the envelope of the heterocyst. This envelope consists of a layer of polysaccharide surrounding a layer of glycolipid, which in turn surrounds a cell wall that is presumed to correspond to that of normal gram-negative vegetative cells (41).

In order to identify mutants in which nitrogen fixation is affected, we mutagenized Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 with Tn5-1063 (40). The transposon was introduced by conjugation (10, 39). Exconjugants were selected in the presence of antibiotics and nitrate and then transferred to nitrate-free medium. Mutants unable to grow with dinitrogen as the sole nitrogen source were selected for further study (14). In the present study, we report the physiological and molecular characterization of one of these strains, which we have designated SNa1. The transposon in SNa1 inserted within an open reading frame (ORF) whose predicted protein sequence shows significant homology to a family of proteins known as high-molecular-weight penicillin-binding proteins (HMW PBPs), which are involved in the synthesis of the peptidoglycan layer of the cell wall. A BLAST search of the recently sequenced Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 genome has allowed us to identify 12 putative PBPs that we have named and organized according to predicted molecular size and the Escherichia coli nomenclature for PBPs (19, 33). Based on this nomenclature, we have named the gene interrupted in SNa1 pbpB and its product PBP2. The wild-type gene has been cloned, and the mutation has been successfully complemented. The expression of pbpB has been studied in vivo using a pbpB-luxAB fusion.

The evidence presented indicates that the Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 putative HMW PBP described here, encoded by pbpB, is required for growth under aerobic nitrogen-fixing conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 and its derivatives (Table 1) were grown at 28°C in the light, ca. 90 microeinsteins m−2 · s−1, on a rotary shaker in 50 ml of medium AA/8 (23) supplemented with nitrate (5 mM) in 125-ml Erlenmeyer flasks. Constructions (Table 2) were introduced into cyanobacterial strains by conjugation (10, 39), and single and double recombinant strains were selected as described by Cai and Wolk (6).

TABLE 1.

Anabaena strains used in this study

| Strain | Derivation and/or salient characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| PCC7120 | Wild type | C. P. Wolk |

| SNa1 | Nmr Fox− Fix+ | This study |

| SNa1(pBG2030) | Nmr Emr | This study |

| DR2028-6 | Spr Smr Ems of double homologous recombination of plasmid pBG2028 with wild-type PCC7120 | This study |

| DR2028-6(pRL1472a) | Spr Smr Ems, double recombinant strain expressing luxCD-E (in a plasmid) | This study |

| SR2028-8 | Spr Smr Emr product of single homologous recombination of plasmid pBG2028 with wild-type PCC7120 | This study |

TABLE 2.

Plasmid constructs used in this study

| Plasmid | Derivation and/or salient characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Bluescript | Cloning vector | Stratagene (San Diego, Calif.) |

| pBG2002 | Circularized EcoRV fragment from Anabaena sp. strain SNa1 that bears Tn5-1063 | This study |

| pBG2027 | Anabaena DNA-containing PstI-BamHI portion of pBG2002 fused to the PstI-BamHI portion of pRL759D that contains oriV, bom, luxAB, and Smr Spr determinant | This study |

| pBG2028 | Product of ligation of pBG2027 linearized at EcoRV, with the FspI portion of pRL1075 that contains sacB and Cmr Emr determinants | This study |

| pBG2029 | 2.4-kb PCR fragment bearing wild-type pbpB as its only ORF cloned in the PCR2.1TOPO vector | This study |

| pBG2030 | Wild-type pbpB on a BamHI-XhoI fragment from pBG2029, inserted into pRL1342 cut with BamHI and XhoI | This study |

| pBG2031 | Wild-type pbpB on a BamHI-XhoI (blunted) fragment from pBG2029, inserted between the SmaI sites bracketing Cmr cassette C.C1 in pRL1404 | This study |

| PCR2.1TOPO | Cloning vector | Invitrogen |

| pDS4101 | Apr, helper plasmid based on ColK, carries mob (ColK) | 17 |

| pRL623 | Helper plasmid bearing methylase genes M.AvaI, M.Eco47II (whose product methylates AvaII sites), and M.EcoT22I (EcoT22I is an isoschizomer of AvaIII) | 13 |

| pRL759D | One of a family of BLOS plasmids with bom, V. fischeri luxAB, oriV and Smr Spr determinant for in vitro replacement of all but the termini of a transposon | 4 |

| pRL1075 | Contains a sacB-oriT (RK2) Cmr Emr cassette that is separated from oriV by inverted polylinkers | 4 |

| pRL1124 | Kmr derivative of pACY177 that bears the same methylase genes as pRL623 | 7 |

| pRL1342 | Cmr Emr RSF1010-based plasmid | C. P. Wolk |

| pRL1404 | Vector based on Nostoc plasmid pDU1 that replicates in Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120, with Cmr cassette C.C1 isolated from pRL171 (11) inserted in its BamHI site, providing the only SmaI, KpnI, and SstI sites in the plasmid | 16 |

The different strains were grown in the presence of appropriate antibiotics. Mutant SNa1 was grown in liquid with 40 μg of neomycin sulfate (Nm) per ml. Single recombinant SR2028-8 and double recombinant DR2028-6 were grown with 2 μg of spectinomycin dihydrochloride (Sp) per ml plus, respectively, 1 μg of erythromycin (Em) per ml and no additional antibiotic. Mutant SNa1 bearing plasmid pBG2030 was grown with 1 μg of Em per ml and 40 μg of Nm per ml. Aldehyde, the substrate for bacterial luciferase, was generated internally by the products of Xenorhabdus luminescens luxC, luxD, and luxE borne on plasmid pRL1472a (15). Em, at 1 μg · ml−1, was incorporated in the media to select for that plasmid.

Assays of nitrogenase.

Liquid cultures were deprived of combined nitrogen under air (aerobic conditions) or under an N2/CO2 (99:1) gas phase (microaerobic conditions; cultures were sealed with rubber stoppers and continuously bubbled with the N2/CO2 gas mixture) for 24 to 48 h, at which time heterocysts, if they were to form, were clearly discernible. Nitrogenase activity was measured in whole cells by the acetylene reduction technique (35). For aerobic assays, 10 ml of cell suspensions deprived of nitrogen under air was placed in stoppered 40-ml vials; to begin the assay, 4 ml of air was withdrawn and replaced with 4 ml of acetylene. The vials were incubated for 30 min at 28°C on a rotary shaker under a constant irradiance of 100 microeinsteins m−2 s−1. For microaerobic assays, the gaseous phase of the cultures deprived of combined nitrogen under N2/CO2 was replaced by 10% (vol/vol) acetylene in N2 and was incubated as indicated above. At the end of the 30-min incubation period, 0.5-ml samples were withdrawn and their ethylene content was determined by injection into a Shimadzu GC8A gas chromatograph.

Recovery of transposon-containing plasmids and construction of derivatives of these plasmids.

Plasmid pBG2002 (Tn5-1063 and contiguous Anabaena DNA) (Table 2) was obtained by digestion of chromosomal DNA from mutant SNa1 with EcoRV and then by recircularization of the fragments with T4 DNA ligase and transfer to E. coli HB101 by electroporation. Colonies that grew on L agar plates with 50 μg of kanamycin sulfate (Km) per ml were analyzed further (40). Approximately 3.2 kb of Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 genomic DNA was recovered in pBG2002.

In order to generate the SNa1 mutation in wild-type Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 (Table 2), most of the transposon was removed from pBG2002 by cutting with PstI and BamHI. The remaining 4.1-kb piece of DNA was ligated with pRL759D (4) that had been cut with PstI and BamHI, generating pBG2027. Plasmid pRL1075, which bears the conditionally lethal gene sacB that allows for selection of double recombinant strains (6), was cut with FspI, and a fragment of 5.6 kb was inserted into pBG2027, which had been cut with EcoRV, to generate pBG2028 (Table 2).

Cloning of pbpB and assays of complementation of the mutant strain.

A PCR clone of wild-type Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 DNA bracketing the transposon in mutant SNa1 was generated with the primers 5′-ATCATCGCCACGGCAAAATT-3′ and 5′-GTGTAGCACCAGCACAACTA-3′. The resulting 2.4-kb PCR fragment was first cloned in the vector PCR2.1TOPO (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) producing plasmid pBG2029 (Table 2). From pBG2029, that same fragment was cut and inserted between the BamHI and XhoI sites of pRL1342 (Cmr Emr; RSF1010-based plasmid obtained from C. P. Wolk [unpublished data]) generating plasmid pBG2030 (Table 2), which can replicate in Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120. In parallel, the 2.4-kb Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 DNA was also inserted between the SmaI sites of pRL1404 (16), producing plasmid pBG2031 (Table 2), which can also replicate in Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120.

Plasmids pBG2030 and pBG2031 were transferred with pRL1342 and pRL1404, respectively, as controls from E. coli to cells of mutant strain SNa1 as described previously by Wolk et al. (39) by using helper plasmid pRL623 (when pBG2031 or pRL1404 was transferred) (Table 2) (13) or pDS4101 and pRL1124 (when pBG2030 or pRL1342 was transferred) (Table 2) (7, 17). Selection was made on petri dishes of agar-solidified AA medium (1, 23) containing 5 μg of Sp per ml and 200 μg of Nm per ml (pBG2031 or pRL1404) or 10 μg of Em per ml and 200 μg of Nm per ml (pBG2030 or pRL1342).

The green colonies that appeared on the filters were further restreaked to plates of the same medium to assess their ability to grow in the absence of combined nitrogen.

Southern analysis.

Southern analysis of chromosomal DNA made use of the Genius system (Boehringer Mannheim GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). DNA probes were labeled with digoxigenin-11-dUTP from random primers.

Sequence analysis.

Automated sequencing (ABI Prism 377 DNA Sequencer; Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.) was performed on fragments that were subcloned from pBG2002 and pBG2029. The initial sequencing from the ends of the transposon in pBG2002 was performed from specific primers for the left and right ends of the transposon (4, 16). Sequence analysis was performed with the UW GCG version 7 package of the University of Wisconsin Genetics Computer Group (9). Amino acid sequence analysis was performed with the DAS transmembrane prediction package (Proteomics tools) at the ExPASy Molecular Biology Server (http://www.expasy.ch). Database comparisons and alignments of the DNA and predicted protein sequences were performed by using the default settings of the algorithm developed by Altschul et al. (2) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information with the BLAST network service programs.

In vivo monitoring of the expression of pbpB.

Fifty milliliters of rapidly growing cultures of strains DR2028-6 (bearing pRL1472a) and SR2028-8 was washed at least three times with AA/8 and then resuspended in 50 ml of AA/8 without antibiotics. For measurements with nitrate as the nitrogen source, AA/8 plus 5 mM nitrate was used to wash and resuspend culture samples. Filaments were examined periodically with a microscope, and the luciferase activity of aliquots was measured at specified times as a measure of the transcription of pbpB. The luminescence of SR2028-8 was measured with supplementation of exogenous aldehyde (12); the luminescence of DR2028-6(pRL1472a) was measured with and without supplementation with exogenous aldehyde (12, 15). In the latter case, the addition of aldehyde did not change luminescence, indicating that endogenous aldehyde was not limiting. Luminescence was measured using a digital luminometer (Bio Orbit 1250 luminometer; Turku, Finland). The luminometer was calibrated by setting the background counts to zero and the built-in standard photon source (a sealed ampoule of the isotope 14C with activity of 0.26 μCi) to 10 mV. Calculations made according to the method described by Hastings and Weber (21) indicated that 1 U (1 mV) corresponded to a light emission of 6.7 × 105 quanta/s from the vial.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of pbpB is in the GenBank database under accession number AF076847.

RESULTS

Phenotype of mutant SNa1.

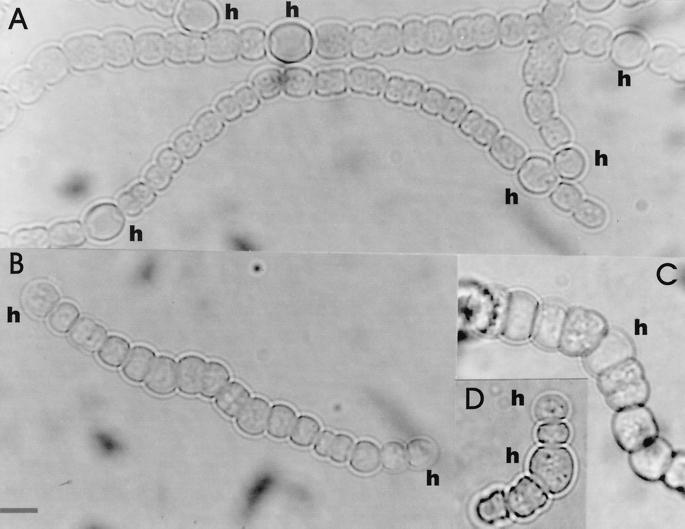

Transposon-bearing (i.e., antibiotic-resistant) exconjugant colonies grown with nitrate as the nitrogen source were transferred to petri dishes lacking combined nitrogen. Colonies that after several days yellowed and therefore were nitrogen starved were selected for further study. Microscopic observation of one such colony on an N2 plate showed a clearly distorted morphology of both vegetative cells and heterocysts (Fig. 1B to D). Filaments were yellow and usually short and twisted, with vegetative cells unequal in size and even shape. The heterocysts or heterocyst-like cells that could be identified in such filaments appeared rather distorted with thin envelopes, and in most cases, no cyanophycin granules could be distinguished at their poles (Fig. 1B to D). However, when the same strain was grown with combined nitrogen (nitrate), no significant differences in cell shape and morphology with respect to the wild type were observed (not shown).

FIG. 1.

Light micrographs of wild-type Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 (A) and mutant strain SNa1 (B to D) grown in AA medium lacking nitrate (micrographs for A and B were taken after 48 h of nitrogen deprivation; micrographs for panels C and D were taken after 96 h). The filaments of strain SNa1 (B to D) are short and twisted; vegetative cells vary in size. Cells that may be presumptive heterocysts are designated (h). Bar, 5 μm.

The doubling time (hours), estimated from the increase in dry weight of the wild-type and mutant SNa1 strains when grown in liquid AA/8 medium supplemented with 5 mM nitrate, was nearly equal (32.2 h for the mutant strain versus 32.3 h for the wild type). However, when deprived of a source of combined nitrogen, the mutant strain bleached and died; in fact, the nitrogenase activity, as measured by the acetylene reduction method (35) after 24 h of nitrogen deprivation under aerobic conditions of the mutant strain, was around 0.5% of that of the wild-type strain (1.9 nmol of C2H4 per mg [dry weight] per h versus 356 nmol of C2H4 per mg [dry weight] per h). However, under microaerobic conditions, the mutant strain reduced acetylene to levels similar to those found in the wild-type strain under the same conditions (52 nmol of C2H4 per mg [dry weight] per h versus 64 nmol of C2H4 per mg [dry weight] per h).

The microscopic observations of the mutant strain, as well as the bleaching of the cultures on N2 and the nearly background-level nitrogenase activity values, indicated that the mutant strain SNa1 is unable to fix atmospheric N2 under aerobic conditions. But as it reduces acetylene under microaerobic conditions, the mutant strain can be classified as phenotypically Fox− Fix+ (14).

Southern analysis showed that only one copy of the transposon had inserted into the Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 genome within an EcoRV fragment of approximately 11 kb (not shown).

Reconstruction of the mutation in mutant SNa1.

To determine whether the phenotype of SNa1 was the result of insertion of the transposon, rather than the result of a secondary mutation, the transposon insertion was reconstructed (see reference 4). Transposon Tn5-1063 (7.8 kb), together with approximately 3.2 kb of contiguous Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 DNA, was recovered from mutant SNa1 upon excision with EcoRV and circularization and transfer to E. coli by electroporation, producing plasmid pBG2002 (from which plasmid pBG2028 was constructed) (Table 2; Materials and Methods). Southern analysis of DNAs from three strains, derived from presumptive recombination of pBG2028 with the wild-type strain Anabaena sp. PCC7120, showed that the original mutation had been reconstructed (not shown). The phenotype of the three double recombinant strains also matched that of mutant strain SNa1 (not shown). One such strain was designated DR2028-6 and was used for subsequent in vivo gene expression studies (see below).

Analysis of the gene interrupted by the transposon in strain SNa1.

The transposon in strain SNa1 was found to interrupt an ORF of 2,289 bp (not shown). The transposon had inserted 1,263 bp 3′ from the first ATG codon of the ORF, generating a 9-bp repeat (5′-GTACGCGTC-3′). A putative ribosome binding site (5′-AGGG-3′) is located 9 bp upstream of the first ATG codon. A putative prokaryotic Rho-independent terminator sequence (5′-GAAATTTCTAAGCCTACCCCCTATTCTGAAAAATTTC-3′) is located immediately following the two stop codons.

The Tn5-interrupted ORF encodes a predicted protein of 763 amino acids with an expected molecular mass of 85.1 kDa and an expected pI of 9.17. It shows significant homology with HMW PBPs, which are involved in the synthesis of the peptidoglycan layer of the cell wall of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria (18).

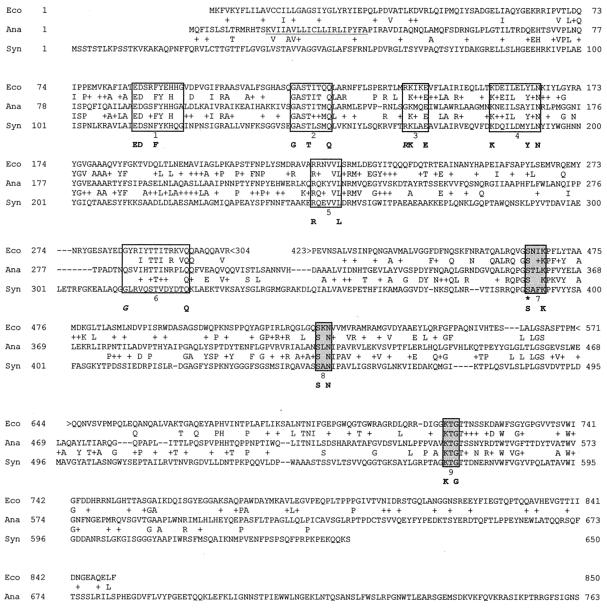

Figure 2 shows a comparison of the predicted sequences of the putative PBP from Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 and two other sequences that produced significant alignments: PBP1A from E. coli, the gram-negative bacterium of reference in the study of PBPs, and a presumptive PBP (PBP1B) from the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803, whose complete genome has been recently sequenced (24, 25). The PBP from Anabaena shares 18.9% identity (31.5% similarity) with PBP1A, the product of ponA from E. coli, and 22.5% identity (37.2% similarity) with the presumptive PBP1B, putatively encoded by mrcA, from Synechocystis. Based on the whole protein sequence, the homology, although significant, is around 30%; however, when we consider the two functional domains of these proteins, a higher homology arises. (i) The N terminus is a putative transglycosylase domain that catalyzes glycan chain elongation. In this region, the identity is 27.6% (50.3% similarity) with PBP1A of E. coli and 22.2% (41.1% similarity) with the presumptive PBP1B from Synechocystis. (ii) The C-terminal domain is the PB domain that acts as a transpeptidase and catalyzes peptidoglycan cross-linking. In this region, the identity is 18.6% (33.5% similarity) with PBP1A of E. coli and 27.9% (41.4% similarity) with the presumptive PBP1B from Synechocystis. HMW PBPs are subgrouped in classes A and B following the method described by Goffin and Ghuysen (19), where the amino terminus of class A contains six conserved motifs, while the amino terminus of class B contains only four conserved motifs. As indicated below, the PBP of Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 falls within class A of HMW PBPs.

FIG. 2.

Similarity of PBP2 of Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 (Ana) to PBP1A of E. coli (Eco) and to the presumptive PBP1B of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6903 (Syn). The symbols < and > indicate parts of the E. coli protein that have been omitted because they show no similarity to PBP2. Dashes indicate gaps introduced to maximize similarities. The putative transmembrane domain of PBP2 is underlined at the N terminus of the translated protein. The presumptive active-site serine is indicated by an asterisk. The six conserved motifs (from 1 to 6) characteristic of the N-terminal regions of multimodular class A HMW PBPs are indicated with unshaded boxes, and the three conserved motifs (from 7 to 9) at the C-terminal region are indicated with shaded boxes. The identities defining the amino acid sequence signatures of the motifs are indicated in boldface below each box (19). Consensus residues that differ from the Anabaena amino acid are italicized.

The N-terminal domain of the PBP of Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 contains two main and characteristic features: the hydrophobic sequence assumed to function as a membrane anchor (the 20-amino-acid region underlined in Fig. 2) (18) and the amino end core, comprising the transglycosylase non-PB (n-PB) module, which can be defined as the sequence extending from the amino end of motif 1 to the carboxy end of motif 6. In Fig. 2, within unshaded boxes, the regions comprising residues 90 to 99, 121 to 128, 141 to 145, 158 to 167, 224 to 229, and 283 to 295 correspond to motifs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, respectively, as described for class A HMW PBPs by Goffin and Ghuysen (19). Amino acid residues E and D in motif 1 and E in motif 3 are conserved in all class A PBPs and are considered essential components of the transglycosylase activity (19). However, the core of the n-PB module of the PBP of Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 diverges from that of the class A consensus in that the first amino acid residues of motifs 3 and 6 are different (Fig. 2).

Within the C-terminal domain of the PBP of Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120, three motifs can be found that are highly conserved in all members of the penicilloyl serine transferase superfamily (Fig. 2, shaded boxes). These motifs include the SXXK tetrad containing the active-site serine at residues 358 to 361, the SXN triad at residues 417 to 419, and the K[T/S]G triad at residues 548 to 550. In the folded protein, these conserved motifs generate an active site that interacts with β-lactam antibiotics. The serine catalyzes the rupture of a peptide bond, forming a serine ester-linked acyl derivative. The core of the PB module can be defined as the sequence starting 60 amino acid residues upstream from motif SXXK and terminating 60 to 70 amino acid residues downstream from motif K[T/S]G or at the carboxy end of PBPs which have no carboxy-terminal extensions. Such extensions are present when the sequence between motif K[T/S]G and the carboxy end of the protein is more than about 60 to 70 amino acid residues long. This extension is usually rich in N and Q and the charged amino acid residues D, E, K, and R. This extension in the PBP of Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120, together with the one for PBP1C of E. coli (19), is the largest of all known HMW PBPs.

During the course of our study, a preliminary sequence of the Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 genome became available at the Cyanobase website (http://www.kazusa.or.jp/cyano) in the form of unedited sequence files (contigs).

We sought putative PBPs within the Anabaena sp. sequence files by using BLAST searches with the amino acid sequences of PBP1a, -1b, -1c, -2, -3, -4, -5, -6, and -7, DacD, AmpC, and AmpH of E. coli; PBP1, -2a, -2b, -2c, -2, -4 and -5 of Bacillus subtilis; presumptive PonA (sll0002), MrcA (sll1434), MrcB (slr1710), FtsI (sll1833), DacB (slr0804 and slr0646), PBP4 (sll1167), and slr1924 of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803; and the putative PBP of our study.

We found 12 putative Anabaena sp. PBPs, which we have ordered in Table 3 according to their predicted molecular sizes. Genes and proteins have been designated by basically following the E. coli nomenclature for PBPs. The object protein of our study is the second largest in size and accordingly has been designated PBP2, and the gene interrupted in SNa1 has been designated pbpB. Anabaena sp. PCC7120 has at least eight HMW PBPs (six belonging to class A and two to class B) and four low-molecular-weight (LMW) PBPs. The ORF in the sequence file C304 is located at one of the extremes of the sequence file, and the ORF is interrupted in the N terminus. The incomplete ORF fragment shows homology with PBP4 of E. coli and with the presumptive products of dacB genes (slr0646 and slr0804) of Synechocystis.

TABLE 3.

Putative PBPs found in the genome of Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120

| Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 genome sequence filesa | ORF (nucleotide position in the sequence file) | Amino acid residue no. | Molecular mass (kDa) | Suggested gene denomination | Suggested protein denomination | PBP class | Position of the transmembrane region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C374 | 2039→4366 | 776 | 86.357 | pbpA | PBP1 | HMW class A | 69–85 |

| C372 | 29389→27101 | 763 | 85.171 | pbpB | PBP2 | HMW class A | 15–34 |

| C376b | 33383→35653 | 756 | 82.742 | pbpC | PBP3 | HMW class A | 163–176 |

| C331 | 13567→11639 | 643 | 71.054 | pbpD | PBP4 | HMW class A | 41–65 |

| C329 | 7745→5916 | 610 | 67.486 | pbpE | PBP5 | HMW class B | 24–45 |

| C259 | 19381→17555 | 609 | 67.256 | pbpF | PBP6 | HMW class B | 48–64 |

| C331 | 10903→9089 | 605 | 66.891 | pbpG | PBP7 | HMW class A | 7–19 |

| C353 | 26459→24651 | 603 | 65.963 | pbpH | PBP8 | HMW class A | 7–17 |

| C365 | 15916→14306 | 537 | 60.683 | pbpI | PBP9 | LMW | nfb |

| C378 | 60290→58830 | 487 | 52.917 | pbpJ | PBP10 | LMW | 8–18 |

| C242 | 5773→4532 | 414 | 45.570 | pbpK | PBP11 | LMW | 9–20 |

| C304 | 31832→31074 | ? | ?c | ? | ? | LMW | ? |

Kazusa DNA Research Institute (http://www.kazusa.or.jp/cyano).

nf, not found.

?, unknown at present.

Table 3 also shows the position of the hydrophobic sequences in the N terminus that are assumed to function as a membrane anchor. Only PBP9 lacks this region, and in the case of the PBP within fragment C304, whose N terminus we have been unable to localize in any other sequence file, we cannot verify whether it has the transmembrane region.

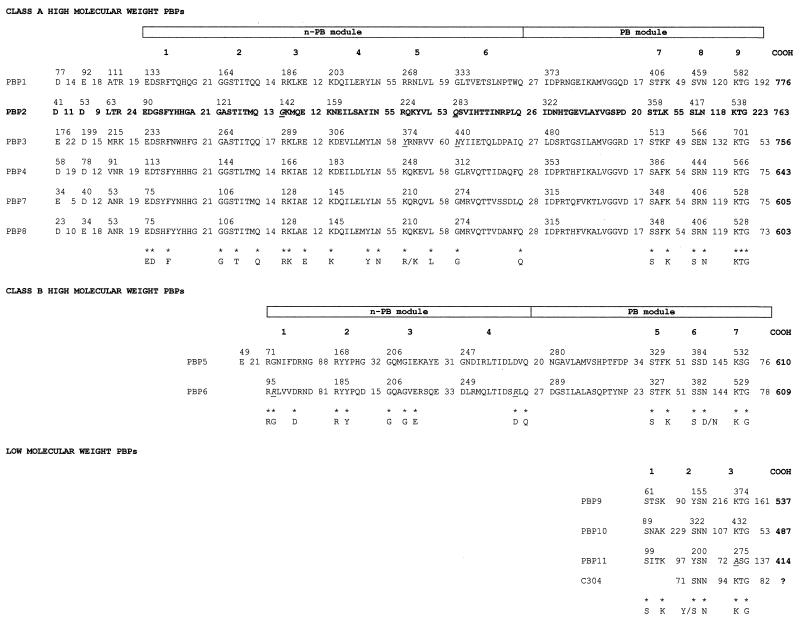

Figure 3 shows the alignments of the 12 putative Anabaena PBPs in three classes (HMW PBPs [classes A and B] and LMW PBPs), as previously described by Goffin and Ghuysen (19). Regarding the class A HMW PBPs, the nucleotide sequence of pbpA (PBP1) possibly starts with a UUG codon that is preceded by an evident ribosome binding site (AGGGGGA). PBP1 presents a carboxy-terminal extension rich in the amino acids N, Q, E, K, and R, but it is shorter than the one found in PBP2. The n-PB module of PBP3 diverges in the first amino acid residues of motifs 5 and 6 (Fig. 3, underlined italics) from the class A motif 5 and motif 6 signatures. pbpD (PBP4) possibly starts with a GUG codon. The six identified class A HMW PBPs of Anabaena are highly homologous to class A PBP1a, -1b, and -1c of E. coli; to PBP1, -2c, and -4 of B. subtilis; and to those presumptively encoded by genes ponA (sll0002), mrcA (sll1434), and mrcB (slr1710) of Synechocystis.

FIG. 3.

Amino acid sequence analysis of putative PBPs of Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 according to the method described by Goffin and Ghuysen (19). Conserved motifs (19) and amino- and carboxy-terminal extensions of putative PBPs of Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 are shown. Asterisks at the bottom of each PBP group define the amino acid signature of the motifs. Amino acid residues that do not obey the amino acid signature are in underlined italics. PBP2, the protein of our study, is in boldface. The intermotif distances are given as the number of amino acid residues.

There are two clear class B HMW PBPs in Anabaena (Fig. 3), PBP5 and PBP6. PBP6 is the only one of the eight HMW PBPs that does not present any dicarboxylic acid (D or E) immediately downstream from the hydrophobic sequence at the N terminus; PBP6 also diverges in the 2nd amino acid residue of motif 1 and the 11th residue of motif 4 (Fig. 3, underlined italics) from the class B motif 1 and motif 4 signatures. The two class B HMW PBPs are highly homologous to PBP2 and -3 of E. coli; PBP2a, -2b, and -3 of B. subtilis; and that presumptively encoded by ftsI (sll1833) of Synechocystis.

The LMW PBPs PBP9 and PBP11 (Fig. 3) are very similar to the β-lactamases AmpC and AmpH of E. coli and to the presumptive products of gene pbp (sll1167) and slr1924 of Synechocystis. As already shown in Table 3, PBP9 does not have a transmembrane region in the N terminus. In PBP11, the third motif differs from the consensus sequence K[T/G]G. PBP10 is highly homologous to PBP4 of E. coli and to the presumptive products of gene dacB (slr0804 and slr0646) of Synechocystis.

Cloning of the wild-type version of pbpB and complementation of the mutation.

A 2.4-kb PCR fragment of Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 DNA was shown to contain the pbpB gene as its only ORF by sequencing (not shown). The sequence of the cloned gene was identical to that obtained from the transposon-mutagenized form of the fragment recovered on pBG2002 (Table 2). The 2.4-kb fragment bearing the PCR-amplified wild-type pbpB was cloned in shuttle vector pRL1404 as pBG2031a. In that vector, pbpB is close to cyanobacterial replicon pDU1 and is oriented to permit transcription of pbpB from pDU1. Plasmid pBG2031a was transferred by conjugation to mutant SNa1 but proved highly toxic to mutant SNa1 even when nitrate was used as the nitrogen source; this toxic effect could be due to a very strong promotion coming from the internal promoter of pDU1. In parallel, we also cloned that same fragment in the RSF1010-based plasmid pRL1342 (C. P. Wolk, unpublished data), generating plasmid pBG2030, which can replicate in Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120. Plasmid pBG2030, after conjugal transfer to mutant SNa1, successfully complemented the mutation: Emr colonies form mature and functional heterocysts that appear in long filaments with normally shaped vegetative cells and grow aerobically with N2 as the sole nitrogen source (not shown).

In vivo expression of pbpB.

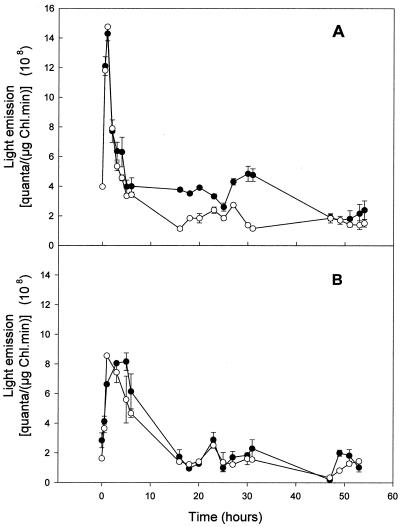

Transposon Tn5-1063 generates transcriptional fusions between Vibrio fischeri luxA and luxB genes, which encode luciferase, and genes into which the transposon becomes inserted (40), thus permitting monitoring of gene expression in vivo, provided that the transposon is correctly oriented. However, the transposon in mutant SNa1 placed luxAB antiparallel to the gene pbpB (not shown). Plasmid pBG2028 (Table 2; Materials and Methods) was constructed in order to reconstruct the mutation placing luxAB parallel to the direction of transcription of pbpB. Single recombinant (Emr Spr Smr [sucrose sensitive] Fox+ Fix+) and double recombinant (Ems Spr Smr [sucrose resistant] Fox− Fix+) strains were obtained. Single recombinant SR2028-8 and double recombinant DR2028-6 were selected for the in vivo expression studies. Plasmid pRL1472a, which bears the aldehyde biosynthetic genes luxCD-E (15), was introduced by conjugation into the double recombinant strain DR2028-6. The in vivo expression of pbpB from cell suspensions of strains DR2028-6 and SR2028-8 was monitored as a function of time using nitrate or N2 as nitrogen sources (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Luciferase activity of suspensions of cells from the double recombinant strain DR2028-6 (A) and single recombinant strain SR2028-8 (B). Cells were washed three times in AA/8 medium plus 5 mM nitrate and resuspended in the same medium (●) or were washed three times and resuspended in AA/8 medium lacking nitrate (○). Samples were taken and their luminescence was measured at the times indicated. chl, chlorophyll.

Although pbpB of Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 is essential for nitrogen fixation under aerobic conditions, the pattern of expression of the gene in the single (Fig. 4B) and double (Fig. 4A) recombinant strains is very similar, regardless of the choice of nitrate or N2, during the first 10 h of culture. An initial four- fold induction is followed by an equally extensive decrease in expression. The subsequent impression that, in the double recombinant strain, the gene is transcribed more in the presence than in the absence of nitrate could be due to the inability of the strain to fix N2 aerobically. Such an effect is not observed in the single recombinant strain, which is capable of aerobic N2 fixation. Therefore, PBP2 is probably present under both growth conditions but is essential only when N2 is used as the sole nitrogen source and cells start to differentiate into heterocysts.

DISCUSSION

We describe for the first time the cloning and molecular characterization of a gene, pbpB, presumptively encoding a cyanobacterial PBP. Remarkably, this protein appears to be required specifically for aerobic nitrogen fixation. A mutation in pbpB results in no evident phenotypic difference with the wild-type strain when cells are grown aerobically with or microaerobically without nitrate. However, when deprived of combined nitrogen under aerobic conditions, filaments become short and yellow and are comprised of vegetative cells of unequal size, and the heterocysts that differentiate are nonfunctional.

The protein predicted by the ORF interrupted by the transposon in SNa1 resembles class A HMW PBPs (19). The only information available about the occurrence and number of PBPs in cyanobacteria comes from the complete chromosomal sequence of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803 (24, 25) and contigs representing the genomic sequences of Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 (http://www.kazusa.or.jp/cyano) and Nostoc punctiforme (http://spider.jgi-psf.org). Eight Synechocystis genes that presumptively encode PBPs were identified on the basis of sequence similarity. Four of these (ponA, mrcA, mrcB, and fts1) encode presumptive HMW PBPs, and the others (dacB [slr0804 and slr0646], pbp [sll1167], and slr1924) encode presumptive LMW PBPs. We have identified 16 putative PBPs from N. punctiforme contigs; 7 correspond to class A HMW PBPs, 4 to class B HMW PBPs, and 5 to LMW PBPs. Of 12 putative PBPs identified from Anabaena contigs, 6 correspond to class A HMW PBPs. To our knowledge, Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 and N. punctiforme in particular show the highest number of class A HMW PBPs ever reported from a single organism. No mutagenesis study has heretofore been undertaken, and no physiological role has been ascribed to any putative cyanobacterial PBP.

Mutant strain SNa1 was successfully reconstructed, and the mutation was complemented with a 2.4-kb fragment that bears pbpB as its only ORF. The next ORF 3′ from pbpB is oppositely directed in the chromosome and encodes a putative protein that is highly similar to a hypothetical protein of Synechocystis (s76621). We conclude that the mutant phenotype of SNa1 is due to the interruption of pbpB by Tn5-1063 and not to a polar effect of that mutation.

PBPs of a given species often overlap functionally. As a result, a mutation in a single PBP-encoding gene in E. coli (3, 8, 22, 33, 34), B. subtilis (29–32), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (28) often does not produce a phenotype different from that of the wild-type strain. In contrast, mutation of Anabaena sp. gene pbpB results in a distinctive phenotype.

The heterocyst is a specialized cell whose interior becomes microaerobic, permitting nitrogen fixation to take place in an aerobic environment. The development of a microaerobic interior entails major modifications of the original vegetative cell (41). In addition, the analysis of Fox− mutants of Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 defective in the synthesis of lipopolysaccharide has provided evidence of a role for the cell wall of the developing heterocyst as a determinant for heterocyst differentiation (42). In Streptomyces griseus, several distinct PBPs may be required for septation during vegetative growth and sporulation (20). Perhaps during heterocyst differentiation, changes in the structure of the cell wall similarly require the activity of different PBPs. Because pbpB is expressed in both the presence and absence of nitrate, PBP2 is probably present in vegetative cells. However, during growth on nitrate, PBP2 is either dispensable or replaced by other PBPs. PBP2 is apparently essential for aerobic growth on N2. We suggest that this protein may be needed to create a specific structure of the peptidoglycan layer in heterocysts, perhaps by altering the number of cross-links between glycan chains and/or the degree of elongation of chains, to facilitate deposition of the additional cell wall layers needed to protect nitrogenase from entry of O2.

Because there is evidence of a relationship between the differentiation of heterocysts and of spore-like cells called akinetes (26, 27, 37), we are currently trying to disrupt the corresponding gene of cyanobacterial strains that are capable of both differentiation processes. It will be of interest to determine whether ORFs that we have identified as possibly encoding PBPs are essential for the viability or processes of cellular differentiation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by Dirección General de Enseñanza Superior PB96-0487.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen M B, Arnon D I. Studies on nitrogen-fixing blue-green algae. I. Growth and nitrogen fixation by Anabaena cylindrica Lemm. Plant Physiol (Rockville) 1955;30:366–372. doi: 10.1104/pp.30.4.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baquero M R, Bouzon M, Quintela J C, Ayala J A, Moreno F. dacD, an Escherichia coli gene encoding a novel penicillin-binding protein (PBP6b) with dd-carboxypeptidase activity. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:7106–7111. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.24.7106-7111.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black T A, Cai Y, Wolk C P. Spatial expression and autoregulation of hetR, a gene involved in the control of heterocyst development in Anabaena. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:77–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buikema W J, Haselkorn R. Molecular genetics of cyanobacterial development. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1993;44:33–52. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai Y, Wolk C P. Use of a conditionally lethal gene in Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 to select for double recombinants and to entrap insertion sequences. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3138–3145. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.3138-3145.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen M F, Meeks J C, Cai Y, Wolk C P. Transposon mutagenesis of heterocyst-forming filamentous cyanobacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1998;297:3–17. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denome S A, Elf P K, Henderson T A, Nelson D E, Young K D. Escherichia coli mutants lacking all possible combinations of eight penicillin binding proteins: viability, characteristics, and implications for peptidoglycan synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3981–3993. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.13.3981-3993.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elhai J, Wolk C P. Conjugal transfer of DNA to cyanobacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1988;167:747–754. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)67086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elhai J, Wolk C P. A versatile class of positive-selection vectors based on the nonviability of palindrome-containing plasmids that allows cloning into long polylinkers. Gene. 1988;68:119–138. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90605-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elhai J, Wolk C P. Developmental regulation and spatial pattern of expression of the structural genes for nitrogenase in the cyanobacterium Anabaena. EMBO J. 1990;9:3379–3388. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07539.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elhai J A, Vepritsky A, Muro-Pastor A M, Flores E, Wolk C P. Reduction of conjugal transfer efficiency by three restriction activities of Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1998–2005. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.6.1998-2005.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ernst A, Black T A, Cai Y, Panoff J-M, Tiwari D N, Wolk C P. Synthesis of nitrogenase in mutants of the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 affected in heterocyst development or metabolism. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6025–6032. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.19.6025-6032.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernández-Piñas F, Wolk C P. Expression of luxCD-E in Anabaena sp. can replace the use of exogenous aldehyde for in vivo localization of transcription by luxAB. Gene. 1994;150:169–174. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90879-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernández-Piñas F, Leganés F, Wolk C P. A third genetic locus required for the formation of heterocysts in Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5277–5283. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5277-5283.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finnegan F, Sherratt D. Plasmid ColE1 conjugal mobility: the nature of bom, a region required in cis for transfer. Mol Gen Genet. 1982;185:344–351. doi: 10.1007/BF00330810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghuysen J M. Serine β-lactamases and penicillin-binding proteins. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1991;45:37–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.45.100191.000345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goffin C, Ghuysen J M. Multimodular penicillin-binding proteins: an enigmatic family of orthologs and paralogs. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1079–1093. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1079-1093.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hao J, Kendrick K E. Visualization of penicillin-binding proteins during sporulation of Streptomyces griseus. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2125–2132. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.8.2125-2132.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hastings J W, Weber G. Total quantum flux of isotropic sources. J Opt Soc Am. 1963;53:1410–1415. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henderson T A, Young K D, Denome S A, Elf P K. AmpC and AmpH, proteins related to the class C β-lactamases, bind penicillin and contribute to the normal morphology of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6112–6121. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.19.6112-6121.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu N-T, Thiel T, Giddings T H, Wolk C P. New Anabaena and Nostoc cyanophages from sewage settling ponds. Virology. 1982;114:236–246. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90269-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaneko T, Sato S, Kotani H, Tanaka A, Asamizu E, Nakamura Y, Miyajima N, Hirosawa M, Sugiura M, Sasamoto S, Kimura T, Hosouchi T, Matsuno A, Muraki A, Nakazaki N, Naruo K, Okumura S, Shimpo S, Takeuchi C, Wada T, Watanabe A, Yamada M, Yasuda M, Tabata S. Sequence analysis of the genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. II. Sequence determination of the entire genome and assignment of potential protein-coding regions. DNA Res. 1996;3:109–136. doi: 10.1093/dnares/3.3.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaneko T, Sato S, Kotani H, Tanaka A, Asamizu E, Nakamura Y, Miyajima N, Hirosawa M, Sugiura M, Sasamoto S, Kimura T, Hosouchi T, Matsuno A, Muraki A, Nakazaki N, Naruo K, Okumura S, Shimpo S, Takeuchi C, Wada T, Watanabe A, Yamada M, Yasuda M, Tabata S. Sequence analysis of the genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. II. Sequence determination of the entire genome and assignment of potential protein-coding regions (supplement) DNA Res. 1996;3:185–209. doi: 10.1093/dnares/3.3.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leganés F. Genetic evidence that hepA gene is involved in the normal deposition of the envelope of both heterocysts and akinetes in Anabaena variabilis ATCC 29413. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;123:63–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leganés F, Fernández-Piñas F, Wolk C P. Two mutations that block heterocyst differentiation have different effects on akinete differentiation in Nostoc ellipsosporum. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:679–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liao X, Hancock R E W. Identification of a penicillin-binding protein 3 homolog, PBP3x, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: gene cloning and growth phase-dependent expression. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1490–1496. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1490-1496.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Popham D L, Setlow P. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and regulation of the Bacillus subtilis pbpF gene, which codes for a putative class A high-molecular-weight penicillin-binding protein. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4870–4876. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.15.4870-4876.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Popham D L, Setlow P. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, mutagenesis, and mapping of the Bacillus subtilis pbpD gene, which codes for penicillin-binding protein 4. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7197–7205. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.23.7197-7205.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Popham D L, Setlow P. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and mutagenesis of the Bacillus subtilis ponA operon, which codes for penicillin-binding protein (PBP) 1 and a PBP-related factor. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:326–335. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.2.326-335.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Popham D L, Setlow P. Phenotypes of Bacillus subtilis mutants lacking multiple class A high-molecular-weight penicillin-binding proteins. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2079–2085. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.2079-2085.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spratt B G. Properties of the penicillin-binding proteins of Escherichia coli K12. Eur J Biochem. 1977;72:341–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spratt B G, Cromie K D. Penicillin-binding proteins of gram-negative bacteria. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10:699–711. doi: 10.1093/clinids/10.4.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stewart W D P, Fitzgerald G P, Burris R H. Acetylene reduction by nitrogen-fixing blue-green algae. Arch Mikrobiol. 1967;62:336–348. doi: 10.1007/BF00425639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolk C P. Heterocysts. In: Carr N G, Whitton B A, editors. The biology of cyanobacteria. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1982. pp. 359–386. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolk C P. Heterocyst formation. Annu Rev Gen. 1996;30:59–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolk C P, Quine M P. Formation of one-dimensional patterns by stochastic processes and by filamentous blue-green algae. Dev Biol. 1975;46:370–382. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(75)90113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolk C P, Vonshak A, Kehoe P, Elhai J. Construction of shuttle vectors capable of conjugative transfer from Escherichia coli to nitrogen-fixing filamentous cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1561–1565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolk C P, Cai Y, Panoff J-M. Use of a transposon with luciferase as a reporter to identify environmentally responsive genes in a cyanobacterium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5355–5359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolk C P, Ernst A, Elhai J. Heterocyst metabolism and development. In: Bryant D, editor. Molecular biology of the cyanobacteria. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publications; 1994. pp. 769–823. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu X, Khudyakov I, Wolk C P. Lipopolysaccharide dependence of cyanophage sensitivity and aerobic nitrogen fixation in Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2884–2891. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.2884-2891.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoon H S, Golden J W. Heterocyst pattern formation controlled by a diffusible peptide. Science. 1998;282:935–938. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5390.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]